Sprout Social: The Story of Social Media Management's Quiet Giant

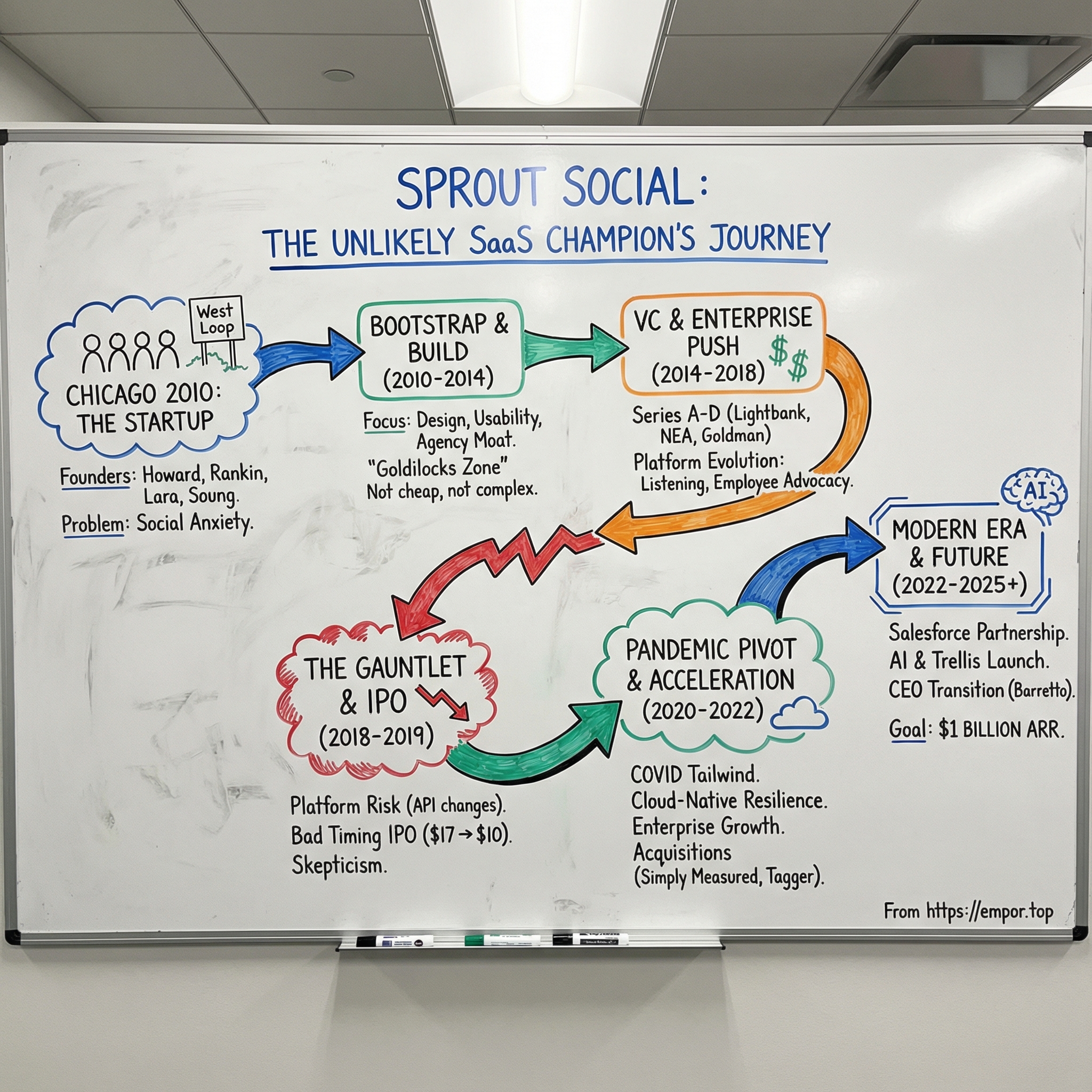

I. Introduction: Chicago's Unlikely SaaS Champion

Picture this: it’s April 2010. In Chicago’s West Loop—a neighborhood still shaking off its meatpacking past and inching toward “tech corridor”—four founders are building software for a problem most businesses can barely name yet.

Facebook has just passed 500 million users. Twitter is turning into the world’s live wire. And inside marketing departments everywhere, a new kind of anxiety is taking hold: We need to be on social. But what does “being on social” even mean when the posts never stop, the comments are public, and one bad reply can become a screenshot forever?

Sprout Social was founded in 2010 by Justyn Howard, Aaron Rankin, Gil Lara, and Peter Soung. Over the next fifteen years, what started as a Chicago startup became a platform used by roughly 30,000 brands around the world. By Q3 2025, Sprout reported $115.6 million in revenue, up 13% year-over-year. And along the way, the product earned some of the strongest third-party validation you can get in SaaS, including being named the #1 Best Software Product in G2’s 2024 Best Software Awards.

But the path from scrappy startup to public company wasn’t a straight line. It was bootstrap discipline colliding with venture-scale ambition. It was competing against rivals that raised hundreds of millions more. It was going public at a moment when the market was least inclined to be generous—and then watching the stock trade down roughly 40% from its opening price. And it was living through a pandemic that could have broken the business, only to come out stronger.

So here’s the real question: how did a bootstrapped Midwestern company become the premium player in social media management—winning in a crowded category, surviving brutal platform dynamics, IPO’ing at arguably the worst possible time, and still emerging as a leader?

The answer comes down to positioning, design, a quietly powerful agency distribution moat, and a patient, capital-efficient style of growth that fits Chicago better than Silicon Valley hype ever could.

This is the Sprout Social story—from a 2010 side project to a publicly traded company with sights set on $1 billion in subscription revenue. Let’s dive in.

II. The Founding Context: Chicago 2010 & the Social Media Gold Rush

A City Finds Its Startup Identity

To understand why Sprout Social emerged from Chicago—and not San Francisco, New York, or Boston—you have to rewind to what Chicago tech looked like in 2010.

That was the year the city got its Big Sexy Startup: Groupon. It was exploding onto the national stage, pulling in coastal venture money, and forcing people who’d never looked twice at the Midwest to pay attention. Around the same time, Excelerate Labs launched (now Techstars Chicago), giving early founders a real on-ramp: mentorship, community, and a sense that you didn’t have to leave to build something serious.

For years, Chicago had fought a gravity problem. Ambitious technical talent tended to drift west. And if you asked most people where to start a tech company, Chicago probably wasn’t in the first handful of answers. Groupon’s meteoric rise didn’t just create a success story—it changed the narrative.

It also helped trigger an ecosystem response. Eric Lefkofsky and Brad Keywell, two of the city’s most visible entrepreneurs, launched Lightbank to fund startups building in and around Chicago. They wrote early checks—often in the roughly $100,000 to $1 million range—but the bigger point wasn’t the number. It was the signal: Chicago could back its own.

Lightbank would go on to invest in companies like Groupon, Tempus AI, Fiverr, Udemy, and Sprout Social. And Sprout wasn’t just another bet—it fit the broader mission. If Chicago was going to prove it could produce world-class tech companies, durable SaaS businesses were exactly the kind you’d want to see born there.

The Founders: Complementary Skills from Chicago's Enterprise Tradition

Sprout Social’s founding team brought an unusual combination for the era: enterprise software instincts paired with real design ambition.

Justyn Howard didn’t come up through the classic “move to the Valley and start a consumer app” pipeline. He went from selling electronics in California to working at the education software company New Horizons, which brought him to Chicago in 2003. He got pulled into social media the way a lot of early adopters did—not through a grand strategy deck, but by watching the Twitter feeds of entrepreneurs he admired.

Howard’s path into tech was self-built. In junior high, he traded his dirt bike for his first computer and taught himself to program from a public library book. When his high school got a computer lab, he reworked the games on the PCs to improve them. That combination—curiosity, craft, and a constant itch to make tools better—shows up all over the Sprout story.

Before starting Sprout, Howard spent a decade as an enterprise software sales leader and wrote two books about using technology to improve sales outcomes. That mattered. He wasn’t guessing at how businesses bought software. He understood buying cycles, relationships, and what it took to become a system a company depended on.

He wasn’t alone. Co-founder Aaron Rankin served as CTO and brought deep technical horsepower. Gil Lara became Chief Creative Officer, making design and usability a first-class priority from day one. And Peter Soung rounded out the group with product and operations expertise.

The Initial Insight: Professionals Need Professional Tools

In late 2009, Howard was working at an enterprise software company and wanted a tool that could help him use social media to communicate with consumers. What he found instead were products built largely for individuals, with very little of the business layer that brands actually needed.

That gap became the founding insight. Social media was exploding, but the tooling was bifurcated. On one end, you had basic options—HootSuite’s free tier worked if you were just getting started. On the other end, you had heavy-duty platforms like Radian6 (soon to be acquired by Salesforce): powerful, expensive, and complex enough to require a specialized team.

But in the middle? That’s where the demand was building fast. Agencies juggling multiple clients. Mid-market companies taking social seriously. Growth-stage brands that needed real workflow, collaboration, and reporting—but couldn’t justify enterprise pricing or complexity.

Sprout’s initial model was a cloud-based SaaS platform that helped businesses publish content, engage with audiences, analyze performance, and manage teams. The bet was simple and sharp: build for professionals who take social seriously—not hobbyists, and not enterprise giants. Find the Goldilocks zone, and own it.

III. The Early Years: Bootstrapping, Product-Market Fit & Chicago Grit (2010–2014)

Launching in a Crowded Market

When Sprout Social shipped its first real version in 2011, it wasn’t strolling into an empty field. It was walking into a knife fight.

HootSuite was already becoming the default for small businesses. TweetDeck had a loyal following among Twitter power users, and it wouldn’t stay independent for long—Twitter would acquire it. And at the high end, the enterprise market was getting legitimized in a big way: Salesforce bought Radian6 in 2011 for $326 million, a clear signal that “social” wasn’t just a marketing experiment anymore. It was becoming a budget line item.

Then came more proof that consolidation was underway. Buddy Media was acquired by Salesforce in 2012 for $689 million, and ExactTarget went for $2.5 billion. Money, attention, and heavyweight acquirers were flooding into the category.

Sprout’s response wasn’t to outspend anyone. It was to outbuild them.

The team launched Sprout’s early platform in 2011 with the basics that serious teams needed: engagement, publishing, and analytics. And then, that November, they did something that says a lot about the company’s instincts. They didn’t just patch the product and call it “v1.1.” They rebuilt it.

Sprout launched S2, the second generation of the platform and the foundation of what the product became. It incorporated lessons from early customers and introduced key capabilities like support for multiple users and iPhone functionality. For Sprout, S2 wasn’t a feature release. It was a statement: this product was going to be a professional tool, not a side project.

The Bootstrap Mentality: Customer-Funded, Discipline-First

While competitors raised huge rounds, Sprout grew up with a very different kind of pressure: the pressure to make the business work.

In 2010, the company raised $750,000 in seed funding from Lightbank. Helpful—but not the kind of money that lets you paper over mistakes. That check forced prioritization. It rewarded focus. It made the company earn its next step.

And Sprout was building in a city where that mindset was normal. In 2010, Chicago entrepreneurs Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson published Rework, a bestseller arguing that you should build for customers, not investors—and that chasing growth for growth’s sake is often a trap. Around the same time, founders would routinely talk about how different Chicago felt from the Valley. As David Lieb, founder of Bump, put it: “In Chicago, you have to convince people a bit more about what’s your business model, how are you going to make money. Those things aren’t as big a deal here in the Valley.”

Sprout internalized that. They didn’t try to be everything to everyone. They aimed for customers who would pay for quality. And instead of stuffing the product with every possible feature, they tried to make the core experience so good that switching felt like moving backwards.

Design as Competitive Moat

Here’s what really separated Sprout early on: it didn’t feel like enterprise software.

In a category full of cluttered dashboards and “good luck” interfaces, Sprout was clean, intuitive, and—rare for B2B—pleasant to use. That wasn’t an accident, and it wasn’t a coat of paint at the end. With Gil Lara as Chief Creative Officer from day one, design wasn’t a department. It was part of the product’s identity.

The early experience established the patterns Sprout became known for: a unified inbox that pulled messages into one place, a publishing calendar that made planning visual and team-friendly, and analytics that didn’t require a specialist to interpret.

And that mattered because the people living in these tools weren’t IT admins. They were social managers and agency teams spending hours a day inside the product. They cared about workflow. They cared about speed. They cared about whether a tool helped them look good at their job. Sprout won them over by being the one platform that didn’t fight back.

Early Customers and the Agency Play

By 2014, Sprout had surpassed 10,000 customers, spanning small businesses and large enterprises. But the real story wasn’t just the number—it was who they were winning, and why.

Sprout leaned into agencies early: marketing firms and creative shops running social media for multiple clients. It was a savvy go-to-market move for a few reasons.

First, agencies were willing to pay. They weren’t buying software as a “nice to have”; they were billing for outcomes, and great tools made their services more valuable.

Second, agencies needed capabilities that single-brand teams didn’t. Multi-client management, collaboration, and reporting across accounts weren’t edge cases—they were the job. When Sprout built for that reality, it created differentiation competitors hadn’t prioritized.

Third, agencies turned into a distribution engine. When an agency brought Sprout into a client relationship, it came with built-in trust. And when that client later switched agencies—as marketing clients often do—they frequently stayed on Sprout anyway. The agency might open the door, but the workflow and history inside the tool made it sticky.

By 2014, Sprout had done the hard part: it had found product-market fit in a specific segment, built a sustainable business without lighting cash on fire, and established a brand associated with design, polish, and professional-grade social media work.

IV. The First Inflection Point: The Venture Capital Decision (2012–2016)

The Strategic Crossroads

By 2012 and 2013, Sprout Social had something many startups never reach: real product-market fit, paying customers, and a business that could stand on its own two feet.

But the market around them was changing fast. This wasn’t a sleepy software category anymore—it was a land grab. HootSuite was raising enormous sums to expand globally. Sprinklr was building the kind of war chest that would eventually top $400 million. And on the high end, Salesforce was making it clear it intended to win, snapping up Radian6 and Buddy Media and effectively announcing: social software is now enterprise software.

Sprout’s leadership faced a classic scaling dilemma. Keep growing the Chicago way—disciplined, customer-funded, sustainable—or take outside capital and try to compete in a category that was quickly becoming defined by size and speed.

They chose to raise.

Series A to Series C: Building the Enterprise Motion

Sprout’s capital path wasn’t one clean leap—it was a sequence of steps that pulled the company into a different weight class.

Lightbank, based in Chicago, made an early investment in Sprout in May 2010 as part of a Series A round. New Enterprise Associates first invested in June 2014 in a Series B round, bringing a powerful combination of money and credibility. NEA also had a long relationship with Lightbank and the Groupon founders, which mattered: in a competitive market, who backs you can be almost as important as how much they write.

Then, in February 2016, Goldman Sachs Investment Partners joined in a Series C round. Having Goldman’s merchant banking arm on the cap table was a different kind of signal. Sprout wasn’t just a promising SaaS company anymore—it was starting to look like a business institutions wanted exposure to.

The funding changed what Sprout could do.

Hiring sped up. The company invested in enterprise sales, brought in more seasoned leadership, and built the customer success muscle needed for bigger, more complex rollouts. At the same time, the product roadmap widened. Sprout pushed beyond the early core—publishing, engagement, and analytics—and started building toward a broader platform, including social listening and employee advocacy.

In August 2015, Sprout launched Bambu by Sprout Social, an employee advocacy product that helped organizations curate content for employees to share on social media. It was an important expansion: Sprout was no longer only about managing a brand’s outward presence. It was also about mobilizing the people inside the company—something larger organizations cared deeply about.

The Platform Evolution

By 2016, Sprout was shipping features like social listening and deeper reporting. This wasn’t just “more functionality.” It was a shift in identity.

Listening meant dealing with an entirely different scale of problem: massive volumes of unstructured social data, constantly changing, filled with nuance and noise. It also meant wading into territory occupied by specialists like Brandwatch and Synthesio. But strategically, it did something powerful: it moved Sprout up the stack—from a tool that helps you post, to a system that helps you understand.

And customers were ready for that shift. Social media was no longer a marketing experiment. CMOs wanted to track sentiment. Support teams wanted to spot problems before they turned into public disasters. Product teams wanted an unfiltered stream of feedback about what was working and what wasn’t.

At the same time, Sprout was doing something else that would prove critical later: building relationships with the platforms themselves. Sprout became an official marketing partner with Facebook in July 2012, followed by Twitter in November 2012, and added API integration with Google+ in May 2013.

Those weren’t just technical checkboxes. They were early relationship-building moves in a world where the social networks controlled the rules, the data, and the APIs. As those networks tightened access in the years ahead, being a trusted partner—rather than just another tool scraping by—would matter.

Series D: Setting the Stage for Public Markets

Sprout’s next major private milestone came in December 2018, when it announced $40.5 million in new funding led by Future Fund, with participation from Goldman Sachs and New Enterprise Associates.

Future Fund’s involvement stood out. As Australia’s sovereign wealth fund, it wasn’t a typical venture investor chasing a quick flip. Its participation signaled long-horizon, institutional confidence in the business Sprout had built.

That Series D round—Sprout’s last private financing—valued the company at roughly $800 million post-money. By this point, Sprout had grown into a real scale company: it had passed 25,000 customers, grown to around 500 employees, and counted major brands among its users, including American Express, Pepsi, Hyatt, Steelcase, Titleist, Ticketmaster, Tito’s Handmade Vodka, Subaru, and Samsung.

Altogether, by December 2018 Sprout had raised $102 million across six funding rounds—modest compared to some rivals, but more than enough to build an enterprise-grade organization.

And Sprout also set itself up structurally for what came next. After the IPO, the founders collectively held approximately 72.9% of the voting power through Class B shares. That dual-class control would become a key part of the story: it gave leadership room to play the long game, even when the public market inevitably tried to pull them into the short term.

V. The Competitive Gauntlet: Surviving the Platform Wars (2014–2018)

The Battlefield Takes Shape

By the mid-2010s, social media management had stopped feeling like a scrappy new category and started looking like a real market—with clear lanes, entrenched players, and increasingly sharp elbows.

HootSuite owned the bottom of the market. Its freemium model put it everywhere: small businesses, solo social managers, anyone who needed to “just get something out the door.” The bet was simple: win on reach, then convert a percentage of those users into paid plans.

At the other extreme was Sprinklr, built for huge enterprises that wanted one vendor for everything. In September 2020, it raised $200 million from Hellman & Friedman at a $2.7 billion valuation—a sign of how big that vision had become. Sprinklr’s pitch wasn’t “social media management.” It was “unified customer experience management,” bundling social with customer service and broader marketing workflows.

Buffer took a different path entirely: a simple, beloved tool for small teams. It built loyalty through ease of use and a culture of transparency, and it became the default recommendation for creators and lean SMBs who didn’t need a heavyweight platform.

And then there was Salesforce. After buying Radian6 and Buddy Media, it rolled those pieces into Marketing Cloud Social Studio—and with Salesforce’s distribution, the company was always looming over the whole category. If Salesforce decided to lean in, it could show up in any deal simply because it already lived inside the customer’s org chart.

The Goldilocks Strategy

This is where Sprout’s positioning starts to look less like good marketing and more like chess.

Sprout wasn’t cheap enough to win the SMB crowd that could get started on HootSuite for free. But it also wasn’t trying to be a sprawling enterprise suite that required armies of admins and months of implementation. Instead, it aimed right at the middle: serious teams who needed real workflow and reporting, but didn’t want complexity as a lifestyle.

That “Goldilocks zone” was mid-market companies—growth-stage brands and agencies running sophisticated programs that still needed speed, clarity, and sane onboarding. It was an intentional choice, and it turned out to be a defendable one. SMB-first products struggled as soon as collaboration and governance became non-negotiable. Enterprise platforms often found the mid-market awkward: deal sizes could be too small and cycles too fast to justify a heavy, services-driven approach.

Sprout built a motion that fit the segment: sales that could scale efficiently, onboarding that didn’t require a mini-consulting engagement, and pricing that rose with the value customers got out of the platform.

The Agency Moat Deepens

The agency wedge Sprout found early didn’t just keep working—it compounded.

Agencies loved Sprout because it matched their reality. They needed to manage many brands at once, keep teams coordinated, and produce client-ready reporting on demand. Sprout’s multi-client workflows, permissions, and analytics supported that day-to-day grind without turning the product into a maze.

But the bigger win was what happened after an agency introduced Sprout to a client. Once a brand’s publishing habits, historical data, reporting cadence, and team training lived inside Sprout, leaving got harder. Even if the agency relationship changed—and it often did—the client frequently stayed on Sprout because rebuilding all that muscle memory somewhere else was painful.

And agencies became an informal distribution channel. When a brand asked, “What should we use to run social?” the agency’s recommendation carried real weight. Agencies had already tried the other tools, knew what broke under pressure, and had earned trust through outcomes. That kind of endorsement was worth more than any polished marketing campaign.

Platform Dependency: The Existential Risk

There was one problem no amount of positioning could eliminate: every social media management company lived at the mercy of the platforms.

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn—each one controlled the APIs that made third-party publishing, analytics, and engagement possible. They could change the rules overnight, restrict access, or tighten policies in ways that crippled entire product lines.

And they did.

In 2018, Facebook dramatically restricted API access in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal. For a lot of smaller tools, that was the end. They couldn’t adapt fast enough, and they couldn’t negotiate from a position of trust.

Sprout had a crucial advantage: it wasn’t a stranger. It had become an official marketing partner with Facebook in 2012 and with Twitter later that same year. Those weren’t vanity badges. They were relationships—channels for communication, earlier visibility into changes, and a seat at the table when the platforms rewired the ecosystem.

Sprout invested in that work: partnership teams, ongoing integration effort, showing up in the places the platforms wanted serious partners to be. So when the 2018 restrictions hit and weaker players got wiped out, Sprout made it through—not by luck, but because it had spent years treating platform risk like the existential issue it was.

VI. The Second Inflection Point: Going Public at the Worst Time (2019)

The IPO Decision

By 2019, Sprout Social had reached the kind of scale where an IPO wasn’t just a trophy—it was a strategic move. The company closed Q3 2019 with about $105 million in ARR. At an approximately $814 million valuation, that worked out to an ARR multiple of roughly 7.75x.

Sprout had crossed 23,000 customers, kept growth steady, and carved out a premium position in the middle of the market. Going public offered three big things: liquidity for employees who’d been building for nearly a decade, capital to keep expanding the platform (and potentially buy gaps instead of building everything from scratch), and the credibility boost that comes with being a public company.

On December 12, 2019, Sprout priced its initial public offering: 8,823,530 shares of Class A common stock at $17.00 per share. In total, Sprout raised $150 million, selling about 8.8 million shares at $17—right at the midpoint of the $16 to $18 range.

The shares began trading the next day, December 13, 2019, on the Nasdaq Capital Market under the ticker symbol “SPT.” Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, KeyBanc Capital Markets, and William Blair led the deal.

The Timing Disaster

The only problem: the timing was brutal.

December is notoriously unforgiving for IPOs. Investors are distracted, volumes thin out, and big institutions are often more focused on closing the year than underwriting a new story. When trading is light, price discovery gets weird—and momentum is harder to build.

And the market backdrop was shifting too. SaaS multiples, after years of expansion, were starting to compress. Investors were getting less patient with unprofitable growth. Then, just a few months later, the world would get hit by a pandemic no one had priced in.

Sprout came out at $17 in December 2019. During the March sell-off, the stock sank as low as $10.54.

Within months, shares were down nearly 40% from the IPO price. For employees holding equity, it hurt. For outsiders watching the tape, it created an early narrative that something was wrong—that Sprout had misread the market, or worse, that the business wasn’t as strong as the S-1 suggested.

The Skeptic's Case

Public market skepticism clustered around a few familiar critiques.

First: the “crowded market” argument. Analysts looked at HootSuite, Sprinklr, Salesforce Social Studio, and others and decided social media management was a commodity category with too many players and not enough differentiation.

Second: profitability. Losses were growing, from a net loss of $17 million in the first nine months of 2018 to a $20.9 million net loss in the same period of 2019. In SaaS, that’s not unusual during a scaling phase—but public markets don’t grade on startup curves.

Third: platform risk. Facebook’s 2018 API restrictions were still fresh, and investors didn’t need much imagination to picture a world where one policy change could break large parts of a third-party tool’s value.

But what the market missed was the part that mattered most: Sprout’s real defensibility wasn’t in flashy feature checklists. It was in the agency moat, the stickiness of the workflows and historical data living inside the product, and the positioning that let Sprout consistently win between the low-end tools and the heavyweight enterprise suites.

VII. Surviving and Thriving: The Pandemic Pivot & Enterprise Evolution (2020–2022)

COVID Hits: Near-Death and Unexpected Tailwind

SPT plunged to $10.54 during the March 2020 sell-off—down roughly 40% from its IPO price. For a company that had only been public for a few months, that kind of drop doesn’t feel like “volatility.” It feels existential.

Then the world changed, and Sprout’s category changed with it.

With stores closed and events canceled, brands lost their physical touchpoints overnight. Their customer relationships moved to the only place still open: digital. And on digital, social media became the front door. It wasn’t just where you marketed anymore. It was where you answered questions, handled complaints, managed crises, and increasingly, where you sold.

Sprout put it plainly in its messaging at the time:

Despite numerous macro issues, Sprout was fortunate to deliver a strong quarter across the board. We're grateful to our team for continuing to elevate our business and our customers while facing these issues head-on. Our strong performance speaks to the fabric of this company, our resilience, the importance of our platform and our conviction about the opportunities ahead.

And the numbers backed up the story. In Q1 2020, revenue growth accelerated versus the prior quarter. Organic growth rose as well. ARR growth improved. And the count of larger customer accounts—those worth more than $10,000—kept climbing fast. In other words, in the middle of a global shock, Sprout wasn’t merely holding on. It was pulling forward demand.

Cloud-Native Advantage

While many companies were scrambling to figure out remote work, Sprout didn’t have to reinvent itself. It was already a cloud-first business—product, customer support, and internal operations designed to keep running even if no one could come into an office.

Sprout described that resilience directly:

As a cloud-first organization, Sprout products, customer service and overall business operations are designed to carry on uninterrupted by physical incidents or issues at any of our offices—including increased work from home policies, an office closure or reduced staffing. Our team is equipped with secure remote communication and collaboration tools, which we make use of on a daily basis.

That mattered because customers weren’t sending fewer messages during lockdowns. If anything, the opposite. Sprout emphasized the scale and expectation it was operating under:

Sprout is committed to delivering world-class reliability and availability so our customers have the tools to stay connected. With our customers sending more than 350 million social media messages through the platform daily, we hold ourselves to 99.99% uptime.

In a moment when social became the emergency hotline for brands, “the tool works” wasn’t a feature. It was the whole product.

The Enterprise Push Accelerates

COVID didn’t just increase social volume. It raised the stakes. Larger organizations suddenly needed tighter coordination, clearer governance, and more sophisticated workflows—without months-long implementations. That played directly into Sprout’s positioning: enterprise-grade outcomes, without enterprise-grade pain.

A big part of turning that positioning into a scalable machine came from leadership on the go-to-market side. Ryan Barretto joined Sprout in 2016 as SVP of Global Sales & Success and helped build the foundation to scale the business from $30M in ARR to more than $140M in ARR, including scaling customer success, expanding into the enterprise segment, and opening international offices.

His background fit the moment. Before Sprout, Barretto spent a decade at Salesforce.com as it scaled dramatically, most recently serving as VP of Global Sales for Pardot.

So when Sprout promoted him to President in December 2020, it wasn’t just an internal milestone. It was a signal to the market: Sprout was preparing to operate like a true enterprise software company, not simply a well-liked social media tool.

Strategic Acquisitions Fill Gaps

Sprout had also been making moves to deepen the platform well before the pandemic reshaped the category. In December 2017, the company acquired social analytics firm Simply Measured, adding more advanced reporting capabilities, including listening, and expanding access to additional platforms such as YouTube and Pinterest.

The deal brought together engagement, listening, and analytics under one roof. As Twitter’s Zach Hofer-Shall put it at the time: "Sprout Social's acquisition of Simply Measured strengthens its position in the market by bringing together leading engagement and analytics solutions,"

Strategically, this mattered because it pushed Sprout further away from the “publishing tool” box. Better analytics didn’t just help customers measure performance—it made Sprout harder to replace.

Stock Recovery: Vindication

In 2020, SPT surged 245% after bottoming at $10.54 during the March sell-off, recovering to its pre-COVID levels and setting a new high on December 17.

The move didn’t change the product, but it did change the narrative. The market started to see what Sprout’s customers already knew: this wasn’t a fragile app living on borrowed platform access. It was becoming a durable system for how modern organizations communicate with the world—and in 2020, that job suddenly became mission-critical.

VIII. The Modern Era: AI, Integration, and the Platform Bet (2022–2025)

The Salesforce Partnership: A Strategic Masterstroke

One of the most important developments in Sprout’s modern era was a deepening partnership with Salesforce—an especially satisfying twist, given that Salesforce’s Social Studio had once been a major competitor.

In March 2022, Salesforce and Sprout announced a global partnership designed to make social media management easier for Salesforce customers. As Ryan Strynatka, SVP & COO of Salesforce Marketing Cloud, put it: “Social media has become mission critical to the future evolution of business. We’re delighted to partner with Sprout. We’re on a journey to empower companies to create a 360° view of their customers, and Sprout's industry-leading social media management platform will help our customers harness the power of social.”

This wasn’t just a logo swap on a partner page. After the partnership announcement, Sprout onboarded more than 250 previous Social Studio customers in 2022, including 175 new companies in the fourth quarter alone.

Then came the big catalyst. Salesforce announced it would retire Social Studio effective November 18, 2024—and partnered with Sprout to help ensure a smooth transition for Social Studio users. Sprout went on to win the majority of those transitioning customers. In practice, Salesforce had turned Sprout into the default recommended successor to a product that used to compete with it. That’s a rare strategic outcome in SaaS, and it underscored something Sprout had been building toward for years: becoming the “social layer” inside the modern enterprise stack.

Tagger Acquisition: Entering Influencer Marketing

Sprout also expanded outward, into the adjacent workflows that live next to social management.

In August 2023, Sprout announced it would acquire Tagger Media, an influencer marketing and social intelligence platform, for $140 million in cash. The transaction closed on August 2, 2023.

The logic was straightforward. Influencer marketing had become a massive channel, but for many teams it still lived in a separate universe—separate tools, separate reporting, separate workflows—from the rest of their social operations. Tagger brought a product and team that let Sprout extend into influencer marketing alongside its existing publishing, engagement, listening, and analytics capabilities.

Sprout positioned the deal as part of building a more comprehensive platform—and as a step on the path toward its goal of reaching $1 billion in subscription revenue.

The AI Moment: Trellis Launch

By 2025, the category itself was changing again. Scheduling and publishing—once the heart of social media management—was becoming easier to automate. The real differentiation was shifting toward turning social into usable intelligence.

On November 18, 2025, Sprout launched Sprout AI, its most significant intelligence update, anchored by a new proprietary AI agent called Trellis. Sprout described Trellis as a conversational agent that can turn billions of unstructured social data points into actionable business answers.

With Trellis, teams can ask plain-language questions and get instant outputs for use cases like market research, competitive analysis, and voice-of-customer feedback. The release also enabled Sprout to connect with leading AI providers, starting with ChatGPT.

Sprout framed Sprout AI as being powered by its foundation of social data and “network-native insights” secured through premium partnerships—designed to produce more predictive, precise outputs than generic large language models can on their own. More broadly, it was Sprout making a clear platform bet: the future value in social software wouldn’t come from simply helping teams post—it would come from helping them understand.

CEO Transition: The Next Chapter

At the same time, Sprout was also preparing for a leadership handoff that marks a new phase for any founder-led company.

In April 2024, Sprout announced that President Ryan Barretto would become CEO effective October 1, 2024. Justyn Howard would transition from CEO to Executive Chair.

Howard described the decision this way: “Over the past 8 years Ryan has become the backbone of our company and the clear leader to take us through our next era of growth and innovation as we scale our business to $1B and beyond. It’s rare for a founder/CEO to work with someone who so clearly complements their strengths to make a transition like this possible.”

Barretto had joined Sprout in 2016 and, over the years that followed, worked closely with Howard as the company scaled from a startup with less than $30 million in annual revenue to a publicly traded company exceeding $385 million. The transition was structured to be deliberate rather than abrupt: the founder stayed deeply involved, and the new CEO was someone who had already spent years building the operating cadence, scaling the team, and pushing Sprout upmarket.

In other words, Sprout wasn’t changing chapters because it had to. It was changing chapters because it was ready.

IX. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

The Positioning Genius: Finding the Goldilocks Zone

Sprout Social’s most important strategic choice wasn’t a feature. It was a lane.

From the beginning, Sprout positioned itself as premium enough to avoid racing to the bottom on price, but straightforward enough to avoid the slow, services-heavy complexity of true enterprise suites. That sounds simple. In practice, it’s incredibly hard to hold.

HootSuite had reach, but its freemium DNA pulled it toward price-sensitive customers and a “basic tool” perception that made moving upmarket tougher. Sprinklr had power, but its enterprise sales motion and product footprint were often too heavy for mid-market budgets and timelines.

Sprout owned the middle. And the punchline is that the middle wasn’t small—it was where serious teams lived.

Design as Competitive Strategy

In markets where everyone can eventually copy features, experience becomes the differentiator. Sprout’s obsession with design turned usability into a real business advantage—and in B2B, that often becomes a switching cost disguised as convenience.

That shows up in third-party validation. In G2’s 2025 Summer Reports, Sprout earned more than 150 leader badges, including top marks in the Enterprise Grid Report for Social Media Suites. Sprout has been recognized as a G2 Enterprise Leader every quarter since 2018, consistently ranking above competitors, including Hootsuite.

The point isn’t the badges. It’s what they represent: faster onboarding, higher adoption across teams, and fewer reasons to churn. A product people enjoy using doesn’t just feel better—it sells easier and sticks longer.

The Agency Network Effect

Social media management software doesn’t naturally have network effects. Sprout found one anyway.

Agencies brought clients onto Sprout. Those clients then built history inside the platform—publishing workflows, approvals, reporting cadence, analytics baselines. When clients inevitably changed agencies, they often didn’t change tools. And the next agency, frequently already trained on Sprout, could keep operating without friction.

Over time, that created a quiet flywheel: more agencies led to more clients, more clients increased stickiness, and that stickiness made Sprout an easier default recommendation for the next agency-led rollout.

Platform Dependency Management

Every social media management company lives under the same shadow: the platforms control the APIs.

Sprout survived platform shocks that took out weaker players by treating that dependency like the core risk it was—investing in relationships, aiming to be a trusted partner rather than an arms-length integrator, and spreading exposure across multiple networks.

When Facebook restricted APIs in 2018, Sprout’s partner status helped it navigate the fallout. And as new platforms emerged, Sprout’s ability to integrate quickly mattered because in this category, “supported” can be the difference between relevance and replacement.

The Bootstrap-Then-Scale Model

Sprout’s early years of capital efficiency didn’t just conserve cash—they forged habits.

Instead of raising massive rounds early and then being forced into growth-at-any-cost behavior, Sprout proved product-market fit with limited capital. Only then did it raise to accelerate what was already working.

That sequencing mattered when the market’s mood shifted. As investors grew skeptical of unprofitable growth in the late 2010s, Sprout looked less like a story company and more like a business.

Customer Retention as the Ultimate Metric

In SaaS, retention is where the truth leaks out.

Sprout’s dollar-based net retention rate was 104% in 2024, compared to 107% in 2023. Dollar-based net retention rate excluding small-and-medium-sized business (SMB) customers was 108% in 2024, compared to 111% in 2023.

Yes, those numbers moderated from peak levels. But they still tell the same story: customers aren’t just renewing—they’re expanding. Net retention above 100% means the average customer spends more year over year even after accounting for churn, which is another way of saying the product keeps finding new ways to justify its price.

And in a category people love to call “crowded,” that’s the metric that matters most.

X. Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

On paper, this category looks easy to enter. The core mechanics—connecting to social network APIs and letting teams publish, reply, and report—aren’t impossible for a new team to build. But in practice, the hard parts show up fast: earning brand trust, building durable agency relationships, running an enterprise sales motion, and maintaining deep partnerships with the platforms themselves. And now AI is raising the floor. It’s not enough to stitch together integrations—you need serious data infrastructure and real machine learning capability to compete on insights.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

Sprout ultimately plays on rented land. Facebook, X, LinkedIn, and TikTok control the APIs that make third-party social management work, and policy changes can reshape the whole market overnight—as 2018 proved. The counterbalance is that the platforms still rely on an ecosystem of third-party tools to serve SMB and mid-market customers at scale. That creates a kind of mutual dependency, even if the leverage usually sits with the platforms.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Buyers have choices. They can shop across a long list of competitors, and in theory they can switch. But the longer a team runs social inside Sprout, the more the switching costs pile up: historical data, established workflows, staff training, and connected integrations. Mid-market buyers are typically more price-sensitive than large enterprises, but they also tend to have less negotiating leverage than the biggest accounts.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

The substitutes are everywhere. Native tools keep improving, point solutions can win budget by solving one job extremely well, and the largest enterprises can always build something in-house if the stakes justify it. On top of that, AI-native startups can attack from a totally different angle—skipping the “dashboard” paradigm altogether and selling answers instead of software.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Competition is intense and multi-directional: Sprinklr at the top end, the HubSpot and Salesforce ecosystem adjacent to the category, broad horizontal tools like HootSuite and Buffer, and a steady stream of specialists carving out niches. The saving grace is that the market is still large and expanding, which leaves room for multiple winners—as long as each player holds a segment they can defend.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: WEAK-MODERATE

Software scales well, but this isn’t a pure scale-economies juggernaut. Costs tied to running the platform rise with customer volume, even if gross margins are attractive. Scale helps amortize R&D, and it can improve sales and marketing efficiency over time, but it’s not the kind of “the biggest always wins” dynamic you see in retail or logistics.

Network Effects: WEAK-MODERATE

There aren’t strong direct network effects—Sprout customers don’t benefit because other customers are on Sprout. But there are indirect effects. Agencies act like a networked distribution layer, bringing clients along and sharing expertise. And there’s an emerging data flywheel: more usage and more data can translate into better AI-driven insights.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

Sprout’s original wedge was classic counter-positioning: easier and more elegant than heavyweight enterprise tools, and more professional and full-featured than freemium SMB options. The risk is that positioning can be copied, at least in messaging, which means this advantage tends to fade unless it’s reinforced by product and execution.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG (KEY POWER)

This is one of Sprout’s most important defenses. Once a team has years of posts, analytics, reports, and benchmarks inside the platform, that history becomes hard to walk away from. Workflows and approvals get built around the tool. Teams get trained on it. And once Sprout is integrated with systems like Salesforce or HubSpot, switching creates real friction—what you might call integration debt. Sprout’s 95%+ gross retention is the clearest proof that these switching costs are real.

Branding: MODERATE-STRONG (KEY POWER)

Sprout has built a premium brand in the mid-market and agency world, tightly tied to design and usability. Its community, content, and third-party recognition reinforce that positioning, and in a category where buyers often rely on peer recommendations, word-of-mouth matters. It’s not a household name on the level of Salesforce—but it doesn’t need to be to dominate its lane.

Cornered Resource: WEAK

There’s no exclusive asset Sprout owns that others can’t access. The APIs are broadly available. The talent pool is competitive. Agency relationships are meaningful, but not exclusive.

Process Power: MODERATE

Sprout’s product and design culture, plus a decade-plus of customer success and go-to-market learning, are hard to replicate quickly. The company’s enterprise motion has steadily improved over time. Still, this isn’t the kind of deeply embedded process advantage you see in the most legendary operators.

Summary: Sprout’s competitive position rests primarily on Switching Costs and Branding, with an emerging boost from agency-driven and data-driven Network Effects. It’s a solid moat—but not an invincible one, and it has to be earned every year.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

The market expands beyond “marketing.” Social stopped being a channel you post to and became a channel you run the business through. Social commerce, customer service, employee advocacy, and crisis response all pull Sprout into budgets far beyond the classic “marketing tools” line item.

AI can become real differentiation. Sprout’s early push into AI-powered insights, including the Trellis agent and an integration with ChatGPT, gives it a shot at pulling away from competitors that treat AI like a feature checkbox instead of a product shift.

The upmarket move is working. Sprout kept adding bigger customers. By the end of 2024, it had 1,718 customers contributing more than $50,000 in ARR, up 23% year over year. That’s the cleanest proof point that the enterprise migration isn’t just a strategy—it’s happening.

Salesforce becomes a distribution engine. The Social Studio retirement created a rare, one-time wave of inbound opportunity. But the longer-term prize is the deeper tie into the Salesforce ecosystem, where Sprout can show up as the default “social layer” instead of fighting for attention deal by deal.

The agency moat keeps compounding. Agencies don’t just bring customers in—they bring trained operators, repeatable workflows, and client transitions that often stay on Sprout even when relationships change. It’s a quietly sticky segment that keeps paying dividends.

Profitable growth shows up in the financial model. In fiscal 2024, cash flow from operations grew to $26.3 million. Pair that with continued growth and you get the profile public SaaS investors tend to reward: a business that can grow without burning endlessly.

The Bear Case

Commoditization is real. Publishing, scheduling, and basic analytics are easier than ever to replicate, and native platform tools keep getting better. If customers decide “good enough” is good enough, pricing power gets pressured.

Platform dependency never goes away. Sprout can diversify across networks and build partnerships, but it still lives downstream of the biggest platforms’ API rules. One major policy change from Meta or another key platform could materially reshape what the product can do.

Pressure from above and below. The squeeze is the nightmare scenario: broader platforms like HubSpot and Salesforce expand into social, while Buffer and native tools get more capable at lower price points.

TAM may be smaller than the story suggests. The question isn’t whether social matters. It’s whether “social media management” remains a large standalone category long-term—or whether it gets absorbed into broader marketing suites and customer experience platforms.

AI-native startups could rewrite the category. New entrants built around AI-first workflows may approach the problem differently, and legacy architectures can be slower to adapt to a world where customers want answers, not dashboards.

International growth comes with execution risk. Sprout has meaningful exposure outside the U.S.—about 27% of total revenue in 2024 came from non-U.S. customers. To keep growing, it likely needs to expand internationally, and that’s rarely linear.

Macro sensitivity. Sprout serves many mid-market customers, and in a downturn, those teams can treat software like this as discretionary—especially if budgets tighten and leadership starts asking what can be cut.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking Sprout Social’s trajectory, two signals do most of the work:

1. Dollar-Based Net Retention Rate (NRR): NRR captures both churn and expansion. Above 100% means the average customer pays more over time, even after accounting for cancellations—a sign of product stickiness and pricing power. Sprout’s NRR excluding SMB customers was 108% in 2024. If that holds up, the upmarket strategy is staying healthy.

2. Number of Customers Contributing $50K+ ARR: This is the simplest scoreboard for enterprise penetration. By September 30, 2025, customers contributing over $50,000 in ARR rose 21% to 1,947. If that number keeps climbing, average contract value rises with it—and Sprout’s “premium in the middle, moving upmarket” playbook keeps getting validated.

XII. Epilogue & Final Reflections

What's Surprising About the Sprout Story

A few parts of Sprout Social’s journey still feel like they shouldn’t work on paper—and yet they did.

Design excellence as a B2B moat. In a category where “enterprise software” often means clunky and unpleasant, Sprout treated user experience like a strategy, not a skin. Teams didn’t choose Sprout because it was the cheapest or because it bragged about the longest feature list. They chose it because it made the job easier—and because living in the product all day didn’t feel like punishment.

Surviving a catastrophic IPO. Trading roughly 40% below the IPO price would have broken plenty of companies. It can wreck morale, distort priorities, and push leadership into reactive decision-making. Sprout kept building, kept selling, and stayed pointed at the same long-term playbook until the results caught up to the narrative.

The “boring” middle market. While so much of SaaS obsesses over either tiny self-serve customers or massive Fortune 50 contracts, Sprout proved the middle can be a monster business. The mid-market wasn’t a compromise. It was the opportunity—large enough to matter, underserved enough to win, and stable enough to compound.

Bootstrapping advantages. Yes, Sprout raised more than $100 million over time. But its early years were defined by constraint and customer-funded discipline. That shaped what the company valued: focus, product quality, and a business model that could support itself. In a sector where many competitors burned cash to buy growth, that mindset turned into durability.

Chicago works. Sprout was founded in 2010 and stayed headquartered in Chicago. Today it operates with a hybrid team of about 1,400 people across the globe. It has also been consistently recognized as a great place to work, with accolades from Fortune, Glassdoor, Built In, and others. The big takeaway isn’t civic pride—it’s proof: you can build world-class SaaS outside Silicon Valley, and you can do it in a way that’s built to last.

Lessons for Founders

Positioning is everything. Don’t compete where the giants already live or where margins get competed away. Find the segment that’s underserved, pick it on purpose, and build like you plan to own it.

Customer obsession creates defensibility when technology doesn’t. In markets where features converge, real moat shows up in adoption, training, workflow, integrations, and trust. That’s where switching costs are born.

Timing the IPO is nearly impossible. You can do everything “right” and still get unlucky. The only reliable answer is to build a business with fundamentals strong enough to outlast whatever the market decides to do in the short term.

Platform dependency is real. If your product sits on someone else’s APIs, treat that risk like a first-order problem. Diversify where you can, invest in partnerships, and behave like a serious ecosystem participant—not a tool trying to sneak value out the side door.

Design isn’t just aesthetics. In categories where products are functionally similar, the best product to use often wins—because it sells easier, deploys faster, and sticks longer.

Lessons for Investors

Public market narratives can be wrong for years. “Crowded market” was an easy label to slap on social media management. It was also incomplete—and for a while, the stock price reflected the label more than the underlying business.

Retention often matters more than raw growth in mature SaaS. Growth rates can slow for all kinds of reasons. Strong net retention is harder to fake—and it’s usually a better signal of product value, pricing power, and long-term cash generation.

The agency GTM motion is underappreciated. Agencies aren’t just customers. They’re distribution and embedded expertise. When a tool becomes the default inside agencies, it gets pulled into client accounts—and it tends to stay there.

Chicago companies can trade at discounts. Geographic bias is real. When perception lags fundamentals, patient investors sometimes get paid.

The Ultimate Question: Can Sprout Reach $1 Billion ARR?

Sprout has said it’s targeting over $1 billion in revenue in the medium to longer term.

With full fiscal year 2025 expected total revenue of $454.9 million to $455.7 million, getting to $1 billion means roughly doubling from here. At the kind of growth Sprout has posted in recent quarters, that’s not a quick sprint—it’s a multi-year climb, likely measured in several years, not several quarters.

Getting there faster would require some mix of: pushing further upmarket, expanding internationally, extending the platform into adjacent categories, and continuing to use acquisitions selectively, the way Tagger accelerated its move into influencer marketing.

The risks don’t go away: competitive pressure, platform policy shifts, and macro conditions can all slow the journey. But the ingredients are there—strong retention, a premium position, a broadening platform, and a leadership team that has already navigated the hardest kinds of moments.

What the Future Might Hold

From here, a few plausible paths open up:

Acquisition target. A larger platform—Salesforce, HubSpot, Microsoft, or Adobe—could decide Sprout is the fastest way to strengthen its social capabilities. The Salesforce partnership and the Social Studio retirement make that idea especially tempting, even if acquisition speculation has floated around for years without turning into anything.

Continued independence. Sprout could also do the simplest thing: keep operating as a profitable, growing public SaaS company, expanding product breadth and moving steadily upmarket without selling.

Bold M&A. Tagger showed Sprout is willing to buy its way into adjacency when the fit is right. Additional acquisitions—whether in analytics, customer data, or new social channels—could accelerate the path to $1 billion.

A consolidation curveball. If a competitor stumbles badly enough, Sprout could become the consolidator. HootSuite has faced its own challenges; a deal like that would be dramatic, but it would also be a very on-theme way to deepen distribution and share.

What began in a Chicago office in 2010—as an attempt to help businesses cope with social media chaos—became a platform serving roughly 30,000 brands worldwide, approaching $500 million in annual revenue, and holding a market position most competitors would love to have.

At its core, the Sprout story is a story about focus. While others chased the biggest enterprises or raced to the bottom on price, Sprout committed to its lane and executed relentlessly. While competitors tried to win with feature sprawl, Sprout won with usability. While coastal peers burned capital, Sprout’s Chicago discipline built something sturdier.

Whatever the next chapter looks like—reaching $1 billion on its own, joining a larger platform, or evolving in a way no one expects—the foundation built by Justyn Howard, Aaron Rankin, Gil Lara, and Peter Soung, and now led by Ryan Barretto, has already proven more durable than most people assumed back in 2010.

For investors, the real question isn’t whether Sprout is a good company. It is. The question is whether the market fully prices the durability of its positioning, the quality of its retention, and the room it still has to expand. Based on everything we’ve seen, there’s a reasonable case that it still doesn’t.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music