Sonos Inc.: The Story of Premium Audio's Turbulent Journey

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

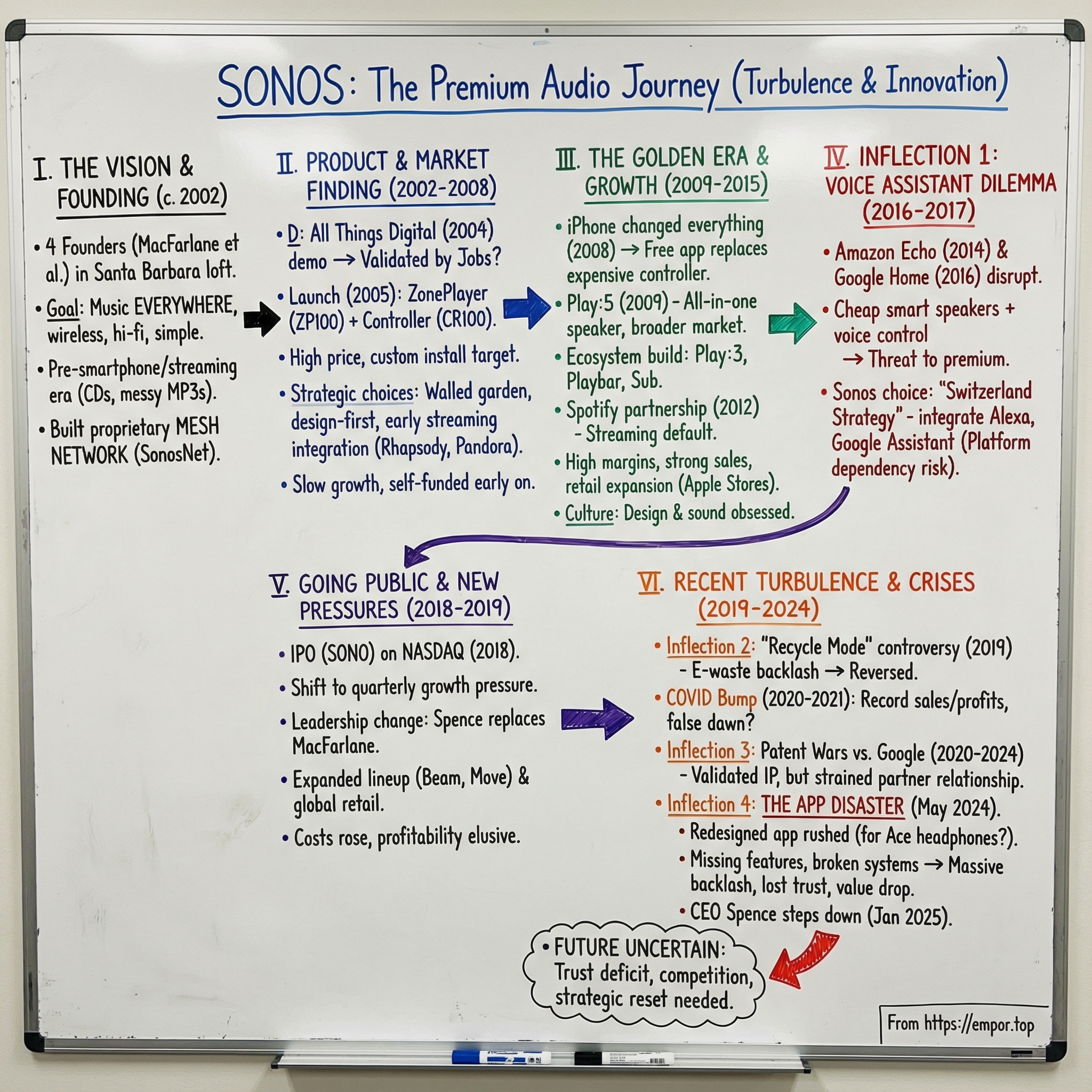

How did four guys in a Santa Barbara loft revolutionize home audio, build a two-billion-dollar company, go public on the NASDAQ—and then nearly destroy it all with a single app update?

This is the story of Sonos. They didn’t just ride the wave of wireless audio; they helped create it. Sonos turned the idea of music “everywhere” in your home—from a PC, from the internet, perfectly in sync, and with real hi-fi sound—into a product normal people could actually buy, set up, and love. Along the way, they built something rare in consumer electronics: a premium brand with a cult following.

And then the world changed.

This story matters because Sonos is basically a case study in modern hardware: the promise, the trap, and the platform risk. It’s what happens when you sell physical products that depend on software, when your customer experience lives inside someone else’s ecosystem, and when you’re caught in the middle—too premium to compete on price, not big enough to dictate the rules like the tech giants can.

We’ll follow Sonos through four inflection points that define its rise and its turbulence: the voice assistant dilemma as Amazon and Google marched into the living room; the “Recycle Mode” controversy that triggered a backlash over e-waste and obsolescence; the patent wars with Google that validated Sonos’s innovations while torching trust with a critical partner; and finally, the self-inflicted app disaster of 2024.

In May 2024, Sonos launched a redesigned mobile app, promising “an unprecedented streaming experience.” What customers got was an app missing core functionality—so broken it disrupted systems people had spent years, and thousands of dollars, building around Sonos. By January 2025, the fallout had wiped nearly $500 million from Sonos’s market value and cost CEO Patrick Spence his job.

This is a cautionary tale about trust: how long it takes to earn, how fast it can evaporate, and whether a beloved brand can come back after breaking the thing its customers cared about most.

II. Founding Context & The Pre-Sonos World (1990s–2002)

To understand what Sonos built, you have to remember what home audio looked like before it existed.

It’s the year 2000. If you wanted great sound, you bought a component stereo. You stacked CDs in a tower. You ran speaker wire through walls if you were serious, or across the floor if you weren’t. Meanwhile, MP3s were starting to take over—but they lived in messy folders on a family computer, not in your living room. Apple introduced the iPod in 2001, but that was a private experience: earbuds, one person, one device. “Music everywhere” in your home wasn’t a product category. It was a pain tolerance test.

Streaming, in the modern sense, barely existed. Napster had shown people that music could move through the internet, but it was still mostly something you downloaded to play on a PC. Pandora, iTunes as we know it, Spotify, and the rest of today’s streaming giants weren’t on the scene yet. Neither was the iPhone. In 2002, America Online was still the top internet service provider, mostly via dial-up, and fewer than 16 million U.S. households had high-speed broadband. The founders would later describe the idea of streaming music through your whole house as, essentially, a stretch.

And yet, that’s exactly what four entrepreneurs decided to go build.

John MacFarlane, Craig Shelburne, Tom Cullen, and Trung Mai weren’t first-time founders. They’d already built Software.com together, which later merged into Openwave. That success mattered for one simple reason: it gave them the financial oxygen to chase their next obsession without begging permission from the market.

MacFarlane had moved to Santa Barbara in 1990 to pursue a PhD at UC Santa Barbara. He didn’t finish. The internet looked bigger than academia, so he and the others built Software.com instead. When Software.com merged with Phone.com in 2000 to form Openwave, the team found themselves back at the same question every successful founder eventually faces: what now?

The first answer, interestingly, wasn’t music. MacFarlane’s initial pitch to the group was aviation—local-area networks for airplanes, with passenger services running on top. It didn’t land. So they went back to the drawing board.

The second answer came from something much more personal: frustration. These were music lovers living in a world where owning music meant owning clutter—shelves of CDs, tangled cables, and expensive custom installations if you wanted sound in more than one room. They could see the future in pieces: digital files, Wi-Fi, broadband. They just didn’t exist in a form that could deliver a simple, reliable, living-room-friendly experience.

That gap became the opportunity. The only problem in 2002 was that almost none of the enabling technology was actually ready.

They incorporated the company as Rincon Audio, Inc. in August 2002, and later renamed it Sonos, Inc. in May 2004.

The early days weren’t a sleek Silicon Valley launch story. They set up shop in a big open room above the Santa Barbara restaurant El Paseo, where the afternoon air filled with the smell of tortillas frying into chips. Inside, it felt more like a classroom than a startup: rows of desks, and John at an elevated “teacher’s” desk.

Nick Millington, one of the early engineers, remembered the chaos vividly: “He’d be working on a prototype amplifier, testing it with sine waves, which was annoying. I was trying to get the audio transport layer developed, and it kept not working and making horrible noises, right in front of the CEO watching me work all day.”

What they were doing wasn’t just product development. They were inventing the plumbing. Millington became central to building the mesh networking approach that would eventually let Sonos systems talk to each other wirelessly throughout a house. Mesh networking existed, but it lived in places like the military, not in consumer audio. As Andy Schubert, Millington’s manager, put it, “The notion of mesh networking existed, but not in any audio products. Almost no one anywhere was working on embedded systems with Wi-Fi. There were no good Linux drivers with Wi-Fi.”

The founding bet was simple to say and brutal to execute: Wi-Fi would get good enough, broadband would spread, and people would want music everywhere. They were right on all three. It just took years of patient, unglamorous building before the world caught up.

III. Building the Product & Finding the Market (2002–2008)

By the summer of 2004, Sonos finally had something real to put in front of people. They started demoing prototypes to industry insiders—and the moment that mattered most came at the 2004 D: All Things Digital conference.

Sonos wasn’t the only company with a “music over Wi-Fi” story that week. Apple debuted the AirPort Express at the same conference, pitching it as a simple way to stream music from your computer to your stereo. But that comparison actually made Sonos look even more ambitious. AirPort Express still anchored you to the computer. Sonos was building an appliance-like system: music in any room, controlled from a dedicated device in your hand, without the living room turning into an IT project.

One anecdote from the conference captured the dynamic perfectly. Steve Jobs reportedly told John MacFarlane that the Sonos controller’s scroll wheel might have violated Apple’s iPod-related patents. For MacFarlane, it wasn’t a threat so much as a weird kind of validation. If Apple thought Sonos looked close enough to the future to be dangerous, they were probably onto something.

Sonos hoped to start shipping in the fourth quarter of 2004. They missed it. The first products reached the market in January 2005, with initial shipments landing in early 2005.

The early lineup was the Sonos Digital Music System: the ZonePlayer (ZP100) and the Controller (CR100). It was a serious piece of kit, and it was priced like one. A basic setup cost more than a thousand dollars, and it often required either custom installation or a customer who didn’t mind tinkering. This wasn’t mass market. Sonos sold through professional integrators, targeting wealthy early adopters who could appreciate what it meant to have synchronized music across rooms—something most people didn’t even realize was possible.

The go-to-market challenges were obvious. The products were expensive. The tech took effort to explain. And the idea of a dedicated controller, while elegant, also felt like yet another device to manage.

But Sonos made a set of strategic choices in these years that would define the company for decades.

First, they built a proprietary mesh network, SonosNet, so the system didn’t depend on whatever unreliable home Wi-Fi router happened to be in the closet. Second, they leaned into a walled-garden approach: fewer variables, tighter control, and a more consistent experience. Third, they treated design as a feature, not an afterthought—an intentional move away from the utilitarian black boxes that dominated traditional home audio.

At the same time, Sonos started positioning itself as more than a speaker company. The real product wasn’t just sound; it was access. Integrations with iTunes, and early streaming services like Rhapsody and Pandora, turned Sonos into the bridge between digital music and the home. As streaming took off, that mattered. Sonos’s own customer research found that once customers started using a streaming service, they listened to dramatically more music at home—because suddenly the system wasn’t limited to whatever files you’d ripped onto a hard drive.

Financing all of this took patience. The founders’ success with Software.com gave them the ability to self-fund early on, buying time to build correctly instead of rushing to ship. Eventually, they did raise outside capital: a $2.3 million Series A in January 2005, followed by a $15 million round in August 2005. Later, institutional investors like Index Ventures and KKR would come in as Sonos needed the resources to scale manufacturing and expand distribution.

Even with strong early reviews, the sales curve wasn’t instantly explosive—and the 2008 recession hit premium consumer electronics hard. But Sonos survived. More importantly, they used these years to refine the system and build the foundation for what came next.

Because the company’s business model was already locked in: make money on hardware, not subscriptions. That was a gift—every sale could be high-margin, and customers weren’t being asked to pay forever. But it was also a constraint. Growth meant shipping more physical products, year after year. And over time, that pressure would shape some of Sonos’s biggest—and most painful—decisions.

IV. The Golden Era: Growth & Market Leadership (2009–2015)

Then the iPhone happened—and it changed Sonos’s trajectory overnight.

Before smartphones, Sonos systems were controlled by a dedicated handheld device: the CR100 controller. It was elegant, and it worked. It was also another piece of expensive hardware—around $350—that you had to buy, charge, and keep track of.

When iOS and Android became the default interface for modern life, Sonos didn’t fight it. They embraced it. The free Sonos Controller app for iPhone arrived in 2008, and suddenly the “remote” wasn’t a product anymore. It was software. Anyone in the house with a phone could control the system, from anywhere, without paying extra. Over time, the dedicated controllers stopped making sense—and by 2012, Sonos discontinued them.

That shift did more than remove friction. It widened the funnel. Sonos no longer felt like a custom-installed luxury system that required special gear. It started to feel like a modern consumer product.

The hardware lineup matured at the same time. In 2009, Sonos launched the Play:5, an all-in-one speaker that delivered serious sound without needing a separate amp-and-speaker setup. It could run on its own or join a much larger whole-home system—up to 31 other Sonos speakers. The Play:5 helped Sonos move from “a clever system for enthusiasts” to “a product normal people could buy one at a time,” and it kicked off a period of sustained sales growth that helped the company expand globally.

And the expansion wasn’t random. It was a deliberate, ecosystem-building march: - The Play:5 established the all-in-one speaker idea. - The Play:3 created a more accessible, mid-range option. - The Playbar pulled Sonos into home theater. - The Sub gave the system real weight and depth.

None of these products were meant to be one-and-done purchases. They were building blocks. Each one made the next purchase easier to justify.

Then came the streaming tailwind. Sonos and Spotify began working together in 2012, and it was a perfect fit. Spotify needed great hardware to show off its service in the home. Sonos needed the biggest streaming service on the planet to feel effortless inside its app. Together, they made streaming at home feel like the default, not a workaround.

Economically, this was the dream scenario for a hardware company. Sonos’s gross margins—over 40%—funded more R&D. Customers didn’t just buy one speaker; they kept adding rooms. The average customer reportedly owned 2.7 Sonos products, which meant growth wasn’t only about finding new households. It was also about deepening each household once they were in.

Sales channels evolved, too. Sonos moved beyond custom installers and into mainstream retail. Landing in Apple Stores was especially meaningful: it wasn’t just distribution, it was a stamp of approval. Sonos wasn’t being merchandised as “home audio.” It was being positioned as premium consumer tech.

Inside the company, the culture stayed stubbornly Santa Barbara: design-first, sound-obsessed, and intensely focused on user experience. “Music lovers making products for music lovers” wasn’t just a tagline—it shaped who they hired and what they shipped.

And yet, even in the middle of the good times, the strategic tension was already there. Sonos was becoming more like a platform—integrating services, living in software, acting as the interface for music in the home—but it still made its money the old-fashioned way: selling hardware. Should it have leaned harder into licensing? Built something recurring? Even built its own streaming service instead of aggregating everyone else’s?

Those questions were easy to ignore while growth was strong.

By fiscal 2017, Sonos was generating just under $1 billion in revenue. The story looked clean from the outside. But the next chapter would expose how much of that success depended on forces Sonos didn’t control.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Voice Assistant Dilemma (2016–2017)

Amazon’s Echo was announced on November 6, 2014, and at first it looked like a curiosity. It launched invitation-only, a gadget you could get if you were deep enough in Amazon’s orbit. Then, on July 14, 2015, it opened up to everyone—and what started as an experiment inside Amazon’s Lab126 quickly became the biggest disruption to home audio since Sonos invented wireless multi-room listening.

The first Echo cost $179. It was a tall black cylinder with an LED ring that made it feel oddly alive. But the real product wasn’t the speaker. It was Alexa—the idea that your home audio system could be controlled with your voice, instantly, from across the room.

Google wasn’t going to let Amazon own the living room. On November 4, 2016—almost exactly two years later—it announced Google Home for $129. The design was softer and more “home-friendly,” but the real advantage was Google Assistant. Alexa had momentum, but Google had spent years turning messy human language into something computers could understand.

For Sonos, the threat wasn’t subtle. The question wasn’t whether voice control was cool. The question was whether customers were about to decide that a $50 smart speaker was “good enough” compared to a $200 Sonos speaker—especially when that cheaper device could also answer questions, control the lights, set timers, and plug into an ecosystem backed by effectively infinite capital.

Then came the real accelerant: the Echo Dot and Google Home Mini. Small, cheap, and everywhere, they flew off shelves and trained millions of households to expect voice control as the default interface. Their job wasn’t to make money as speakers. Their job was to seed a platform. Amazon and Google could subsidize hardware, win distribution at scale, and make the economics work elsewhere.

Sonos was staring at a classic innovator’s dilemma with no good options. Building a voice assistant would require data, AI infrastructure, and years of iteration—resources Sonos simply didn’t have. Ignoring voice would be a slow-motion death as consumer expectations shifted. So Sonos picked the only survivable path: integrate with the giants.

At first, Sonos was caught flat-footed. But it regrouped, added microphones to its products, and began bringing voice assistants into the Sonos ecosystem.

This is where the “Switzerland strategy” took shape. Sonos would be the premium, neutral audio platform that worked with everyone: Alexa integration arrived in 2017, Google Assistant support followed, and later Siri came into the picture via AirPlay 2. It was a smart positioning move—arguably brilliant—but it came with a price.

Because once voice became central, Sonos’s dependency became structural. Even Sonos’s IPO filing later laid out the risk plainly: Amazon or Google could change the rules, restrict access, or shut off capabilities that Sonos customers depended on. CEO Patrick Spence framed it as transparency—acknowledging that a meaningful part of the Sonos experience now ran through someone else’s technology, and someone else’s decisions.

And that’s why Sonos didn’t build its own assistant. The answer wasn’t philosophy. It was brutal math. Amazon and Google were spending billions a year on AI, machine learning, and the data pipelines that make voice recognition actually work. Sonos couldn’t match that, and trying would have diverted resources from the very hardware and software experience that made Sonos worth buying in the first place—likely ending with a worse assistant anyway.

But this inflection point forced a deeper question that wouldn’t go away: what exactly was Sonos now? A hardware company that happened to have an app? Or a software-and-services platform disguised as speakers? The answer mattered, because it would determine whether Sonos’s ecosystem was a lasting advantage—or just the minimum price of admission in a world run by tech giants.

VI. Going Public & The Growth Imperative (2018–2019)

In the summer of 2018, Sonos did the thing hardware companies dream about and fear in equal measure: it went public. The company listed on the NASDAQ under the ticker SONO.

The IPO itself was a little wobblier than the hype suggested. Sonos priced at $15 a share—below the expected range of $17 to $19—raising $208 million and valuing the company at just under $1.5 billion at the offer price. Commentators were already floating much bigger numbers; earlier that spring, MarketWatch suggested Sonos could be worth as much as $3 billion as a public company. Still, the first day of trading gave Sonos a pop: the stock closed at $19.91, implying a market value of roughly $2 billion.

But the bigger change wasn’t the ticker. It was what the ticker represented.

Once you’re public, the product roadmap stops being just a product roadmap. It becomes quarterly performance. Wall Street wanted growth—reliably, predictably, and with a story that made sense on an earnings call. Every launch, every forecast, every miss or beat, now happened under a microscope.

This also marked a clean handoff in leadership. John MacFarlane had already stepped down as CEO in January 2017, announcing in a company blog post that he wanted to spend more time with his family as his wife battled breast cancer. He left not only the CEO role, but also his board seat. In his place: Patrick Spence, the former COO who had joined Sonos in 2012 as Chief Commercial Officer.

Spence became the face of public-company Sonos. Where MacFarlane was the founder-inventor, Spence was more commercially oriented—focused on scaling operations, widening distribution, and keeping the growth engine running.

And the engine did speed up.

Sonos pushed harder into new form factors and price points. The Sonos Beam brought a more affordable soundbar into the lineup. The Sonos Move became the company’s first battery-powered portable speaker, stretching the brand beyond the living room. Updated Amps and Ports refreshed the component side of the business for custom installers—the channel Sonos had started in, even as it grew far beyond it.

Expansion wasn’t just product, either. Sonos moved into Japan, broadened retail partnerships globally, and even opened flagship stores to show off the ecosystem the way Apple does: first in SoHo, then London and Berlin.

But this is where the trade-offs started to show.

Costs climbed. R&D rose as Sonos invested in voice integrations, software infrastructure, and efforts to build something more recurring than “sell another speaker.” Customer acquisition got more expensive, too: the early adopter market was no longer “open a box, watch it sell.” Sonos was now fighting for mainstream consumers in a world where Amazon and Google could effectively subsidize “good enough” audio to win the home.

Financially, the business was big—but not effortlessly profitable. Sonos generated $992.5 million in revenue in fiscal 2017 and still posted a net loss of $14.2 million. The company could grow, but consistent profitability remained frustratingly hard to lock in.

So Sonos leaned even harder into the idea that it wasn’t just hardware. It invested in software and voice, and launched Sonos Radio as a free streaming service—curated content meant to highlight audio quality and build a more direct relationship with listeners.

Yet the existential question didn’t go away. Sonos could dress itself up as a platform. It could add services. But at the end of the day, could it build recurring revenue at real scale—or was it still, fundamentally, a hardware company living with all the cyclicality and pressure that comes with that?

VII. Inflection Point #2: The "Recycle Mode" Controversy (2019–2020)

Every technology company eventually slams into the legacy problem: old hardware that can’t keep up with new software, customers who expect support forever, and the brutal cost of maintaining compatibility across years of products.

Sonos hit that wall in late 2019 with a trade-up program that included a feature called “Recycle Mode.” On paper, it sounded straightforward: if you owned an aging Sonos device, you could get a 30% discount on a new product.

In practice, it landed like a betrayal.

To claim the discount, customers had to trigger a software process that put their existing speaker on a countdown. After 21 days, the device would enter Recycle Mode: user data wiped, the speaker permanently deactivated, and no way to bring it back. Functionally, the program didn’t just encourage upgrading. It required destroying a working product to get the deal.

The backlash was immediate—and it wasn’t just about inconvenience. People saw it as engineered e-waste. Sonos, a brand associated with premium quality and longevity, was now asking customers to turn perfectly functional speakers into landfill. The internet did what it does: tech press piled on, customers fumed, and the story spread fast.

Sonos reversed course, but the trust hit was real. The Trade Up program stayed, but Recycle Mode didn’t. Instead of bricking devices, customers could validate ownership of an eligible “legacy” product using its serial number, then apply the discount in Sonos’s online store. And crucially: you could keep using the old hardware for as long as you wanted.

CEO Patrick Spence apologized publicly: “We heard you. We did not get this right from the start,” he wrote, also walking back the company’s posture on older products and saying they would receive bug fixes and security patches “for as long as possible.”

Underneath the PR mess was a deeper, structural tension. Sonos customers bought speakers the way people buy traditional audio gear: expecting them to last for years, maybe decades. But Sonos speakers weren’t just boxes with drivers. They were software-dependent computers that had to keep up with an ever-changing web of streaming services, voice assistants, and mobile operating systems.

Recycle Mode wasn’t just a communication failure. It was Sonos revealing, out loud, the uncomfortable economics of its model. And it foreshadowed something worse: when your product’s value lives in software, one bad software decision can break far more than a speaker.

But before that bill came due, the pandemic would hand Sonos an unexpected reprieve.

VIII. COVID Bump & False Dawn (2020–2021)

When COVID-19 lockdowns swept the world in early 2020, Sonos—like most consumer electronics companies—initially braced for disaster. Practically overnight, retail shut down. Sonos said it lost about 90% of its business from physical stores, which had been its main engine for nearly two decades. At the time, only about 10% of sales came from ecommerce.

Then something unexpected happened: customers didn’t stop buying. They just moved online.

Sonos’s online sales surged—up roughly 300% year over year—even though most buyers were purchasing premium speakers without hearing them in person. In conversations afterward, CEO Patrick Spence said it felt like the company had pulled five to ten years of ecommerce adoption forward in a single quarter. Sonos watched customers show up on Sonos.com, click “buy,” and trust the brand to deliver.

Stuck at home, people started treating their living spaces like long-term investments. Home audio shifted from “nice to have” to “we live here now.” Sonos’s timing helped: in May 2020, it launched the Sonos Arc, a premium Dolby Atmos soundbar. Even with a pandemic-era rollout, Arc landed as a hit—exactly the kind of upgrade people could justify when the couch became the movie theater.

By fiscal 2021, the numbers looked like a dream. Sonos posted record results: $1.717 billion in revenue (up nearly 30% year over year), record adjusted EBITDA of $278.6 million, and a record adjusted EBITDA margin of 16.2%. Households using Sonos grew 15% to 12.6 million, and existing customers were buying again—accounting for a record 46% of total product registrations.

Zooming in, fiscal 2021 revenue came in around $1.7 billion, up 29% from 2020. Speaker sales were about $1.3 billion, and “system products” rose to $265.1 million. Sonos finished the year with $158.1 million in net income, reversing a roughly $20 million net loss the year before.

The market bought the story, too. Sonos’s stock climbed, peaking above $40 in early 2021. Management grew increasingly confident, repeatedly raising guidance and laying out ambitious fiscal 2024 targets—$2.25 billion in revenue.

But under the euphoria, the stress fractures were already forming.

Supply chain disruptions forced manufacturing shutdowns. Chip shortages made it impossible to fully satisfy demand. And the nagging strategic question didn’t go away—if anything, it got sharper: was Sonos building a bigger business, or just riding a once-in-a-generation spike?

Industry growth patterns told the same story in slow motion. The category had basically flat growth from 2018 to 2019, then jumped in 2020, growing 16%. In 2021, it accelerated again—up 41%—as the industry scrambled to meet what was, in hindsight, unusually inflated demand. Sonos’s installer solutions business saw 2021 as the high-water mark; growth moderated in 2022 and then fell in 2023 as the world reopened. The same pattern showed up across channels: 2021 was the peak.

The pandemic also temporarily softened the competitive pressure—without actually removing it. Apple’s HomePod struggled, but Apple didn’t stop being Apple. Amazon and Google continued shipping Echo and Nest devices by the tens of millions, building installed bases that dwarfed Sonos’s roughly 12 million households.

And while Sonos was busy shipping speakers into a global supply chain bottleneck, it made another decision—one that would pull management focus for years.

In early 2020, Sonos went on the offensive in court.

IX. Inflection Point #3: The Patent Wars & Tech Giant Conflict (2020–2024)

In January 2020, Sonos did something that seemed almost unthinkable for a company its size: it picked a fight with Google.

Sonos filed a patent infringement complaint with the U.S. International Trade Commission, targeting Google Home and Nest Audio devices. The ITC eventually ruled in Sonos’s favor, which set up an import ban on certain Google products. Google’s response wasn’t just to lawyer up—it also stripped features from some of its own home devices, a move that made the conflict feel personal for customers caught in the crossfire.

The strategic risk here was obvious. Google wasn’t just a competitor. It was also a partner. Sonos relied on Google Assistant integration to deliver one of the headline features customers increasingly expected. Suing a company you depend on is the kind of move you make only when you believe the alternative is worse.

Sonos’s claim was blunt: Google copied Sonos’s patented multi-room speaker technology and used it across Google Home and Nest products—and even in Pixel products—while subsidizing hardware to undercut premium competitors. The New York Times reported that Sonos filed two lawsuits covering five patents around wireless speaker design, and that Sonos believed Google gained key insights through a partnership that began in 2013.

According to Sonos, the company began warning Google about infringement in 2016, shortly after the first Google Home launched. By February 2019, Sonos said it had flagged infringement across roughly 100 patents. Sonos also told The New York Times that when it tried to build a smart speaker that could support multiple voice assistant platforms, both Google and Amazon pushed back—insisting users choose only one assistant during setup. Sonos claimed Google threatened to pull Google Assistant from Sonos speakers if it ever appeared alongside a competitor like Alexa.

When the ITC ruling arrived, it was a real win. The commission found that Google infringed five Sonos patents and barred the importation of violating products, including Nest audio speakers and Pixel phones. The patents at issue weren’t obscure edge cases—they covered core behaviors like synchronizing multiple speakers on a network, setting them up, and controlling volume across multiple devices at once.

Google didn’t take that lying down. In August 2022, Google escalated with new lawsuits of its own, centered on patents involving keyword detection, charging using technologies it said it invented, and deciding which speaker in a group should respond to a wake word. Google accused products like Sonos One, Arc, Beam, Move, and Roam of infringing seven patents.

Sonos’s Chief Legal Officer Eddie Lazarus shot back that Google’s lawsuits were retaliation—an attempt to intimidate Sonos for calling out what it described as Google’s monopolistic behavior and to avoid paying royalties for what Sonos claimed were roughly 200 infringed patents. “It will not succeed,” Lazarus said.

After years of litigation, the outcomes were mixed. In the most recent ruling, a San Francisco jury found Google did not infringe Sonos’s home app patent, but the court did find Google infringed Sonos’s speaker patent and ordered Google to pay $32.5 million. Sonos had pursued damages of up to $3 billion, so the final award was meaningful as a symbol—but financially, it barely registered for Google.

A judge, clearly frustrated, blamed both companies for dragging the dispute through trial instead of settling, calling it “emblematic of the worst of patent litigation.”

The patent wars did validate Sonos’s innovation. Courts repeatedly confirmed that Google infringed technologies Sonos pioneered. But the whole saga also exposed Sonos’s core vulnerability: it was a hardware company trying to build a premium business on top of ecosystems controlled by giants—companies that could copy, subsidize, retaliate through platform terms, and outlast you in court.

And the scale gap was brutal. Sonos, long recognized as an originator of the modern wireless connected speaker, was still a relatively small company—around a $2 billion market cap—facing a Google worth roughly $1.5 trillion.

X. Inflection Point #4: The App Disaster (2024)

On May 7, 2024, Sonos shipped a redesigned app. Almost immediately, customers revolted. The complaints weren’t nitpicks. People reported performance problems, missing features, and lost functionality—bad enough that, for some, systems they’d built over years suddenly felt unusable.

Two months later, Sonos apologized. The company admitted that “too many” customers had experienced “significant problems,” and promised a steady drumbeat of fixes: squash bugs, restore missing features, and improve reliability over the coming months.

The app had been heavily hyped in the run-up. Sonos positioned it as a fresh start: throw out the old foundation, rebuild from scratch, and solve long-standing frustrations. “After thorough development and testing, we are confident this redesign is easier, faster and better,” CEO Patrick Spence said in April 2024.

Instead, it became a full-blown brand crisis.

Sonos pitched the overhaul as faster and more customizable—an upgraded control center for the entire Sonos experience, and a foundation for what came next. But the rollout delivered the nightmare scenario for a company whose whole value proposition is reliability: speakers disappearing mid-playback, volume controls that didn’t respond, and music libraries that seemed to vanish. For customers who had spent real money building multi-room systems, it felt like the floor dropped out.

And the worst part was that it didn’t sound like an unpredictable accident. Internal sources later suggested the launch was a foreseeable mess. Engineers had reportedly raised concerns about readiness, but the company was under pressure to get the new app out the door ahead of its first headphone launch.

What made people angrier wasn’t just the bugs—it was what was missing. Sonos had removed basic daily features that many customers relied on, including sleep timers and queue management. About a week after launch, Sonos held an Ask Me Anything on its community forum. The tone was brutal. Users asked why the app shipped “in an obviously unfinished state,” with “critical issues,” when it was “clearly not ready” and “full of bugs.” One participant said their system was “now broken most of the time.” A blind customer who owned 15 Sonos devices reported the new app was “not accessible at all.”

If you’re a premium brand, this is the unforgivable sin: the “upgrade” doesn’t just disappoint—it takes something away.

The architecture made the situation even harder. Sonos couldn’t simply roll back to the old app. The new version wasn’t just a redesign; it came with backend and cloud-service changes that made the previous version effectively incompatible. Sonos had put itself in a corner: keep pushing forward and fix the plane in midair, while customers watched and waited.

The irony is that the decision to rewrite the app wasn’t irrational on its face. Rather than pay down technical debt bit by bit, Sonos opted for a clean-slate rebuild, believing it was the fastest path to modernize. But rewrites are famously risky—and this one was a big one. The project reportedly started around 2022 and spanned roughly two years. Sources said the team spent about a year and a half on user testing and prototypes in SwiftUI, and that the direction tested well. The vision wasn’t the issue.

The execution was. And the timing, too.

It appears Sonos pushed the app out before it was ready because the long-rumored Sonos Ace headphones were approaching launch—and the new headphones required the new app. Leadership didn’t want to delay a major new product category. But in trying to protect that moment, Sonos detonated the core experience for the customers it already had.

The business consequences followed quickly. Sonos had already been reporting declining revenue, and fiscal 2024 marked a second straight year of decline. Sonos reported revenue of $1.518 billion, down 8.3% from $1.655 billion in fiscal 2023. On the earnings call, Spence and CFO Saori Casey estimated the app rollout cost about $100 million in lost revenue, plus tens of millions more to address the fallout.

Then came the belt-tightening. Sonos announced layoffs affecting roughly 100 employees, about 6% of the company, and subsequent product releases were reportedly delayed. “We made the difficult decision to say goodbye to approximately 100 team members representing 6% of the company,” Spence said, calling it a “necessary” step to keep investing in the roadmap.

By October 2024, Sonos was in full recovery mode. The company said it had restored more than 80% of the features removed from the app, with “almost 100%” expected in the coming weeks. “Our priority since its release has been—and continues to be—fixing the app,” Spence said. “There were missteps, and we first went deep to understand how we got here, and then moved to convert those learnings into action.”

But the real damage wasn’t just financial, or even operational. It was relational.

Sonos had spent two decades building trust with exactly the kind of customer you can’t afford to alienate: the enthusiast who owns multiple speakers, has amps driving in-wall installs, and has built daily routines around playlists, alarms, and carefully tuned settings. These customers didn’t buy Sonos because it was the cheapest way to play music. They bought it because it was the system that just worked.

When the software becomes the weak link—when a premium, expensive hardware ecosystem can’t reliably do basic things—it forces the question every hardware company fears: why keep investing here at all?

XI. The Headphones Gamble & Product Diversification (2024)

On June 5, 2024, Sonos finally shipped the product customers had been begging for: headphones. Sonos Ace launched globally in Black and Soft White for $449—Sonos’s first real move into personal audio after two decades of owning the living room.

On paper, Sonos framed Ace as a natural extension of what it already did best: premium sound and clean industrial design. The pitch was classic Sonos: lossless and spatial audio, Active Noise Cancellation with an Aware mode, and a home-theater hook powered by a new feature it called TrueCinema—meant to deliver an especially immersive experience when paired with Sonos gear.

Strategically, the logic was hard to argue with. Headphones are a huge market Sonos had never touched. The Consumer Technology Association projected U.S. consumers would buy 94.5 million wireless earbuds in 2025, up from an estimated 70 million in annual shipments at the beginning of the pandemic. In CTA surveys, 37% of consumers said they were in the market for new wireless earbuds or headphones, and CTA business-intelligence director Rick Kowalski called wireless earbuds “one of the most popular consumer-tech devices overall, second only to smartphones.”

Sonos had even teased it was about to unveil its “most requested product ever.” Ace was that answer—and its competitive target was obvious. At $449, Sonos wasn’t going after bargain shoppers. It was showing up in the same aisle as Bose QC Ultra, Sony WH-1000XM5, and Apple AirPods Max—aiming straight at premium buyers, many of them frequent travelers, who already think nothing of paying extra for comfort and sound. That demographic also overlaps neatly with Sonos’s installed base.

The timing, though, couldn’t have been worse.

Ace arrived just weeks after the redesigned app shipped and the backlash ignited. Instead of a celebratory “Sonos finally did it” moment, the launch got swallowed by anger from the very customers Sonos would have counted on to buy first. The headphones—rumored by some to be the reason the app got rushed out the door—became collateral damage. Sources indicated sales were weak, while Sonos’s community forum and subreddit stayed locked on the app fallout, with complaints and negative sentiment dominating through the spring.

Even setting the app crisis aside, Ace was always going to be a hard hill to climb. Sonos had mastered soundbars and whole-home systems, but it didn’t have a track record in premium wireless headphones—and this is a category with brutally strong incumbents. Reviews landed mixed. The headphones looked stylish and offered extra value for Sonos households, but critics argued the competition was simply stronger, especially on sound quality. The verdict from some corners was blunt: a disappointing debut for the price and the segment.

Ace’s most distinctive feature—the ability to swap TV audio from a Sonos soundbar to the headphones—was genuinely compelling, but also narrow. You couldn’t group Ace with Sonos speakers or set the headphones up as their own “zone” in the app. And the long-running fantasy of seamless handoff—walking in the door and having audio intelligently move between headphones and speakers—wasn’t there.

This was Sonos trying to buy itself a second growth engine. Home audio was facing real structural pressure, and personal audio was booming. But between execution risk, intense competition, and the worst possible launch window, Ace raised an uncomfortable question: was Sonos expanding into the future—or just creating a new distraction while the core experience was on fire?

XII. Current State & Strategic Crossroads (2024–Present)

In January 2025, Sonos announced that CEO Patrick Spence would step down—not just as chief executive, but also as a member of the board. Spence had joined Sonos in 2012 as Chief Commercial Officer and became CEO in 2017. Now, after the app crisis and a brutal year for the business, the company was turning the page.

The board tapped independent director Tom Conrad as interim CEO while it began a formal search for a permanent replacement with an executive search firm. Conrad came with real consumer-audio credibility: he co-founded Pandora, and spent a decade there as CTO and executive VP of product from 2004 to 2014. He’d also held executive roles at companies like Snapchat and Quibi.

Spence didn’t leave quietly, or cheaply. SEC filings said he received nearly $1.9 million in cash severance, plus $7,500 per month from January through June 2025 to serve as a board advisor.

Conrad’s first message to employees signaled a different posture—less “big swing,” more “back to basics.” He wrote, “I think we’ll all agree that this year we’ve let far too many people down. As we’ve seen, getting some important things right (Arc Ultra and Ace are remarkable products!) is just not enough when our customers’ alarms don’t go off.”

He also framed the moment as personal. While at Pandora, Conrad had helped lead one of the early efforts to integrate Pandora with Sonos. “I got my first glimpse of the magic that Sonos could bring to millions of lives every day,” he said, adding that his focus would be restoring the reliability and user experience Sonos was known for, while still pushing new products to market.

Financially, the company entered this reset in a tough spot. For fiscal 2024, Sonos reported about $1.52 billion in revenue, a net loss of $38.1 million, and gross margins of 45.4%. Losses had widened from a $10.2 million loss in fiscal 2023. The company’s last profitable full year was 2022, when it posted $67 million in net income. Meanwhile, the stock had fallen roughly 70% from its all-time high of about $43 in 2021.

And yet, Sonos still had something most hardware companies would kill for: an installed base with real depth. As of September 28, 2024, Sonos said there were nearly 50.4 million registered products across about 16.3 million households. That base—customers who’ve already paid premium prices and often keep adding rooms—remains Sonos’s most valuable asset. The problem is that the market around it has matured, competition is relentless, and new growth is no longer automatic.

Internally, the company was changing fast. With roughly 300 employees gone in less than a year and much of the C-suite turned over, Sonos was not the same organization it had been nine months earlier. The shakeup reached into product leadership too: Conrad removed Chief Product Officer Maxime Bouvat-Merlin, the executive who had publicly defended the app relaunch, and Sonos eliminated the role entirely.

So the strategic crossroads is no longer theoretical. Sonos can double down on premium home audio and rebuild trust feature by feature. It can push harder into adjacent categories—automotive, commercial, and beyond—to find new growth curves. Or it can become an acquisition target. Between the patent portfolio, the brand, and a massive installed base of connected devices, Sonos is the kind of asset that could appeal to a tech giant like Apple or Amazon—or to a traditional audio player looking to buy its way into modern connected ecosystems.

XIII. Business Model & Strategic Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH Building great consumer audio still takes real investment—acoustics, industrial design, software, manufacturing, and support. But the biggest “new entrants” don’t have to worry about any of that the same way. Tech giants can show up with subsidized hardware, instant distribution, and ecosystem gravity. Sonos’s brand still matters at the premium end, but as retail and online discovery have become more commoditized, the old distribution edge has weakened.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE A lot of the core components—chips, drivers, radios—are broadly available. The problem isn’t uniqueness, it’s leverage. Sonos doesn’t buy at the volumes of the mega electronics companies, and that means less pricing power and less priority when supply gets tight. The chip shortage era made that painfully clear: concentration risk in the supply chain can quickly become a product-availability crisis.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH For a first-time buyer, the market is a buffet: every price point, every form factor, every ecosystem. Sonos’s advantage shows up after the first purchase—once someone has speakers in multiple rooms, switching becomes a hassle. But that protection is mostly backward-looking. It helps retain existing households more than it helps win new ones, and post-pandemic consumers have become more price-sensitive.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH This is the structural squeeze. If what you want is “music and a voice assistant,” Amazon and Google can deliver that for a fraction of Sonos’s price. If what you want is pure audiophile gear, traditional hi-fi still exists. If what you want is portable sound, Bluetooth speakers from Bose, JBL, and others are everywhere. Sonos can be better—but in many rooms, for many customers, “good enough” has become a real substitute.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH Sonos fights on multiple fronts at once. Tech giants compete with ecosystem integration and pricing that hardware-only companies can’t match. Traditional audio brands like Bose and Sony have deep category credibility and marketing muscle. And smaller upstarts keep entering with modern design and aggressive pricing. In the mid-market especially, rivalry tends to turn into a price and feature knife fight—exactly the kind of arena where premium positioning is hardest to defend.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

1. Scale Economies: WEAK Sonos can’t manufacture at the unit costs of Apple, Amazon, or Samsung, who spread supply chain leverage across enormous volumes and many product lines. Sonos’s premium pricing helps, but it doesn’t create the kind of cost moat scale players enjoy.

2. Network Effects: WEAK/NONE Sonos has powerful “within-the-home” benefits—multi-room sync and a unified system feel magical when it works. But households don’t make other households more valuable. There’s no user-to-user network effect that compounds over time.

3. Counter-Positioning: HISTORICAL (fading) For years, Sonos won by being the obvious alternative to two bad choices: traditional audio that was complicated, and cheap speakers that sounded bad. But competitors improved, smart speakers normalized convenience, and consumer expectations shifted. The old contrast is less stark.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG For existing customers, Sonos’s ecosystem is sticky. Multiple rooms, grouped zones, settings, and habits create friction against leaving. But switching costs are a shield, not a sword. They help defend the installed base, but they don’t automatically pull in new households.

5. Branding: MODERATE-STRONG Sonos built real premium equity: sound quality, design, and a reputation for “it just works.” But it’s not Apple-level cultural gravity—Sonos can’t effortlessly jump categories or rely on brand alone to win when trust is damaged.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK The patent portfolio matters—Sonos has proved that in court. But patents are an imperfect moat against giants that can design around IP, drag fights out, or simply treat litigation as a cost of doing business.

7. Process Power: MODERATE Sonos has accumulated know-how in tuning, multi-room synchronization, and integrations. That’s real craft built over decades. The problem is that well-resourced competitors can replicate a lot of it over time—especially when the underlying components and platforms are widely available.

Key Strategic Insight: Sonos has shifted from a position powered by counter-positioning, switching costs, and brand into something narrower: switching costs for existing customers, plus a still-meaningful but bruised premium brand. That’s a defensive stance. To get back on offense, Sonos likely needs either new categories that expand the market it can serve, or a stronger brand and experience advantage that justifies paying the premium—especially for first-time buyers.

XIV. The Path Forward: Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bear Case:

The bear case says Sonos is running into forces bigger than any execution plan.

For years, sound quality helped Sonos stay safely ahead. But listening habits have been shifting in ways that don’t naturally favor a living-room speaker ecosystem. “Consumer interest in audio products is shifting more towards wireless headphones and earbuds while interest in smart speakers and smart displays is leveling off,” Parks Associates research analyst Sarah Lee said—momentum that COVID only accelerated.

At the same time, the smart-speaker boom has cooled. Parks Associates found that about half of U.S. households owned a smart speaker in 2021, but ownership hasn’t meaningfully grown since. Edison Research even observed a small decline in the number of people owning a smart speaker this year. In other words: the category that once threatened Sonos has, in a sense, stalled out. But that doesn’t necessarily help Sonos. It suggests the “voice-in-every-room” future never became as central as the giants hoped.

And when you look at how people actually use smart speakers, the ceiling gets lower. In a 2022 survey, British media regulator Ofcom found that even years after the first Amazon Echo, most people still used these devices for simple tasks: playing music, setting timers, and checking the weather. Smart speakers didn’t become indispensable computers. They became appliances—cheap ones.

That’s a problem for a premium hardware company. As audio hardware becomes “good enough” at lower prices, Sonos gets squeezed by commoditization. At the same time, its “works with everything” promise comes with platform risk: Sonos still depends on Apple, Google, and Amazon for critical voice and streaming integrations, and those partners can change the rules whenever it suits them. And against tech giants that can copy features and subsidize hardware with services revenue, Sonos’s moat looks uncomfortably thin.

Then there’s the self-inflicted wound. The app disaster may have permanently damaged trust and accelerated churn among exactly the customers who used to drive word-of-mouth growth: the enthusiasts with multiple speakers and deeply embedded routines. Meanwhile, home audio isn’t a breakout growth market like wearables or mobile, and public markets don’t reward patience. If the category is mature and your core differentiator is credibility, you can’t afford to lose credibility.

In that framing, the endgame looks familiar: a loved hardware company stumbles, never fully recovers, and either fades or gets acquired for parts. The list of cautionary tales—GoPro, Fitbit, Peloton—is long.

The Bull Case:

The bull case starts with a simple idea: premium markets don’t disappear. They just become more demanding.

High-end audio, luxury watches, performance cars—there’s always a segment that will pay for quality, design, and the feeling that the product is built for people who care. Sonos has shown real pricing power with that customer, and its installed base—over 16 million households—is still a meaningful asset. Those customers expand systems, upgrade over time, and tend to come back when Sonos gives them a reason to.

The “Switzerland strategy” still has upside, too. If the world stays fragmented across Alexa, Google, and Apple, neutrality can be a feature. Sonos can remain the premium choice for people who want great sound without pledging allegiance to a single ecosystem. And for anyone who actually cares about multi-room audio, Sonos’s core experience—when it’s working—is still widely seen as best-in-class.

The bull case also argues the app crisis is recoverable. Painful, yes. But the same switching costs that limit new-customer acquisition can help stabilize the base once reliability returns. If Sonos can restore the “it just works” reputation, a lot of customers may choose to forgive, if only because rebuilding an entire home system is a bigger hassle than sticking it out.

Growth could come from going beyond the living room. Headphones expand the market Sonos can play in, even if the competition is brutal. Commercial and hospitality use cases offer diversification into B2B. And international markets—especially in Asia—remain less penetrated than North America and Europe.

Finally, there’s the acquisition angle. Sonos has the brand, the installed base, and connected-device expertise. A strategic acquirer—Apple looking to deepen home audio distribution, Spotify looking for hardware leverage, or a traditional audio company trying to modernize—could justify paying a premium for those assets.

The Realist Take:

Sonos is a good company in a tough position. It’s caught in the premium mid-market squeeze: too expensive to win on price against Echo-like devices, not prestigious enough to win on pure status against Apple.

So this can’t be a “fix a few bugs and carry on” moment. Sonos needs a reset—pick a lane (ultra-premium home audio, platform, services, new categories) and execute like it means it. The app crisis wasn’t just a product failure; it was a leadership and trust failure, and it will shape what customers believe Sonos is for years.

The next 12 to 24 months matter. Watch whether app store ratings recover, whether quarterly results stabilize, and whether customer satisfaction stops bleeding. The new leadership’s job is brutally specific: rebuild trust without starving innovation. If they pull it off, this story becomes a comeback. If they don’t, it becomes the chapter where the decline turns permanent.

XV. Lessons for Founders, Operators & Investors

For Founders:

The Sonos story is a reminder that in hardware, invention buys you time—not safety. First-mover advantage fades fast, and once you’ve proven there’s a category worth owning, copycats with effectively unlimited resources show up. Sonos created wireless multi-room audio and led the market for years, only to face an existential challenge once Amazon and Google made the living room part of their platform wars.

Hardware plus software also doesn’t stay “hardware plus software.” It becomes hardware plus software plus everything else. Every new product generation adds another layer of legacy support. Every streaming integration becomes a long-term maintenance commitment. Every voice assistant partnership adds dependency. The full-stack approach that made Sonos magical in the beginning gradually turned into an ever-growing surface area for things to break.

And customers don’t buy premium speakers the way they buy phones. Many people bought Sonos expecting it to last like traditional hi-fi—years, even decades. The uncomfortable reality is that older devices eventually hit real limits in memory and processing power, and at some point they simply can’t keep up with what the modern software stack demands, even if the hardware still “works.”

Then there’s platform risk. Depending on tech giants for critical features is dangerous, full stop. Sonos’s reliance on Alexa and Google Assistant created vulnerabilities that became painfully obvious when partnerships strained and lawsuits escalated. “Works with everything” is a great promise—until you realize it can also mean you control nothing.

Most of all: customer trust is a bank account that takes years to build and minutes to drain. Sonos spent two decades earning a loyal following. The 2024 app rollout damaged that relationship in weeks.

For Operators:

If the app disaster is remembered for anything inside product teams, it should be this: never ship an “upgrade” that removes the features people depend on. Bugs are frustrating; missing basics feels like betrayal. And beta testing, even extensive beta testing, is not the same as real-world deployment across millions of households with messy Wi-Fi, edge-case setups, and deeply ingrained routines.

Major infrastructure changes also require a true escape hatch. Sonos’s architecture made rollback effectively impossible, which turned a bad launch into a long, public recovery—fixing the plane while flying it, with customers on board and furious.

Premium brands have a special kind of exposure: expectations are part of what customers paid for. When a company known for polish ships something that feels broken, the gap between promise and reality becomes the story—and it amplifies the anger.

And when things go wrong, communication is product, too. The initial defensiveness made the situation worse. Patrick Spence’s early framing of the update as a “better experience” landed badly against the reality customers were living. Sonos eventually got to acknowledgment, empathy, and clearer timelines—but the lag cost additional trust.

For Investors:

Sonos also shows why hardware is a tougher business than it looks from the outside. Even with strong gross margins for consumer hardware, you’re still dealing with capital intensity, inventory risk, and manufacturing complexity in a way software companies simply don’t. That creates fragility—and it narrows your margin for error.

Switching costs help, but they don’t solve growth. An ecosystem can keep existing customers around, yet do very little to win new ones when competition is a click away. Continued growth still requires relentless investment in product, brand, and distribution.

And tech giants change the economics of entire categories. Amazon and Google can price speakers like loss leaders because they’re not really selling speakers—they’re buying ecosystem adoption. That puts permanent pressure on standalone premium players trying to grow beyond the high end.

Public markets add another squeeze: quarterly narratives can push companies toward short-term decisions with long-term consequences. In Sonos’s case, the urgency to ship the new app in time for the Ace headphones—shaped by product-cycle timing and expectations—helped trigger the crisis that consumed 2024.

Finally, there’s the sobering pattern: when beloved hardware companies lose momentum, recovery often doesn’t happen. The mix of operational complexity, intense competition, and damaged trust can create a negative spiral that’s hard to reverse—something the market has seen before with companies like GoPro, Fitbit, and Peloton.

XVI. Epilogue & What's Next

By late 2025, Sonos sat in a place it hadn’t been in at any point in its two-decade run: with its category-defining reputation no longer taken for granted.

The app recovery kept moving. Much of the missing functionality had made its way back, but the damage didn’t vanish just because features returned. Customer sentiment had been bruised, and App Store ratings—public, permanent, and brutally easy to compare—still reflected that reality. Holiday 2024 was the first real test of whether Sonos could still generate excitement through product alone, with launches like Arc Ultra and Sub 4 landing in the middle of the fallout.

The big questions didn’t change. They just got sharper.

Can Sonos restore customer trust? The installed base is still real leverage, but the thing that made Sonos so powerful wasn’t just how many households owned it. It was the advocacy—customers who evangelized it the way people evangelize great products. That kind of loyalty doesn’t come back from a single apology. It comes back after a long stretch of flawless execution and no more self-inflicted wounds.

Is there a viable path to growth, or just managed decline? Premium home audio isn’t a fast-growing market, and the competitive pressure isn’t easing. Real growth likely means finding new demand—through new categories like headphones and commercial use cases, or through deeper international expansion, including Asia. Each path is plausible. None are easy.

Will Sonos remain independent or get acquired? The brand, patent portfolio, and installed base are meaningful assets, and a depressed valuation can make a company look like a bargain. But potential buyers can afford patience; they may wait for more distress to improve the price. Meanwhile, Sonos leadership may resist selling at what it sees as a discount to what the company could be with a successful turnaround.

So what should you watch in 2025 and beyond? App Store ratings as a proxy for satisfaction. Quarterly revenue as a reality check on demand. Any real traction in non-hardware revenue like Sonos Radio and subscriptions. And the CEO search, which will quietly signal what the board thinks the job actually is: steady-handed operator, product visionary, or someone who can shepherd a larger strategic outcome.

Zooming out, Sonos is a clean example of the modern hardware trap. Great products and real innovation can still lose if strategy slips, execution falters, or platform dependencies tighten at the wrong moment.

And it’s also a reminder of what made Sonos special in the first place. The magic was never the mesh networking or the patents or the integrations. It was the invisibility. You wanted music. You pressed play. It worked. At some point, that simple promise got lost.

Twenty-two years earlier, four friends sat above a Mexican restaurant in Santa Barbara, building prototypes that made horrible noises while the CEO tested amplifier circuits. They wanted to put music in every room, wirelessly, with great sound. They did it—and they built a beloved brand along the way.

Whether that brand survives its self-inflicted wounds won’t be decided by what Sonos invented. It’ll be decided by what it executes next: rebuilding trust, managing platform risk, and finding growth in a world that no longer needs to be convinced that wireless multi-room audio is the future.

The music, as they say, has to play on.

Key Metrics to Track

If you want to know whether Sonos is actually recovering—or just saying the right things—three signals matter more than any one-quarter headline.

1. Net Promoter Score / Customer Satisfaction

The app disaster ultimately wasn’t a bug story. It was a trust story. You’ll see the real recovery in whether customers are willing to recommend Sonos again—through App Store rating trends, survey data, fewer complaints, and fewer returns. If satisfaction stays depressed, growth gets harder and more expensive, no matter how good the next product looks.

2. Products Per Household

Sonos’s best growth engine has always been the second sale, then the third. The flywheel works when people start with one speaker, then slowly turn their home into a system. If products per household starts sliding—if customers stop expanding, or even pause upgrades—it’s a sign the ecosystem is losing its pull. Management said this metric held during fiscal 2024, but it’s one of the first places you’d expect the app fallout to show up over time.

3. New Household Acquisition Rate

The installed base is valuable, but it can’t be the only story forever. Long-term health requires winning brand-new customers—people choosing Sonos for their first “real” home-audio system. In a market packed with alternatives and with Sonos’s reputation bruised, this becomes the clearest test of whether the company can still grow beyond its loyal core.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music