Scotts Miracle-Gro: From Lawn Care Legacy to Cannabis Kingmaker

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

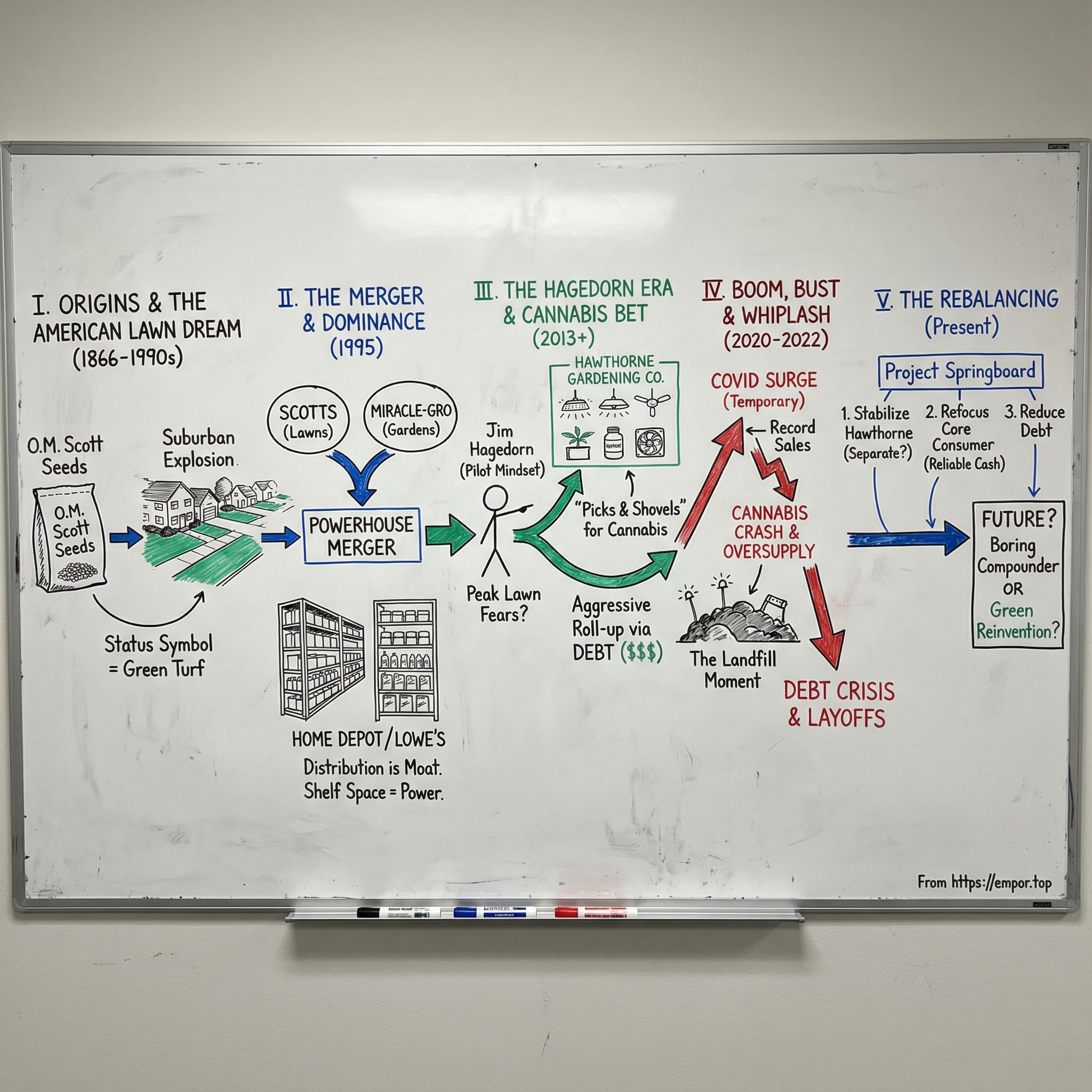

Picture this: it’s 2016, and Jim Hagedorn is standing in front of a room full of Wall Street analysts who came to hear about fertilizer, grass seed, and the upcoming spring season. Instead, the CEO of America’s most buttoned-up lawn care company makes a very different pitch. He says he’s going to put “half a billion dollars” to work in marijuana.

For Scotts Miracle-Gro, this wasn’t a quirky side project. Over the next decade, the company’s cannabis push—channeled through its hydroponics subsidiary, Hawthorne Gardening—turned into one of the most controversial bets in modern consumer-products history. Jim would later acknowledge just how painful it got: debt piled up, hundreds were laid off, and Hawthorne “almost took Scotts down.”

So how did a company built on the promise of pristine suburban grass become the biggest name in hydroponic marijuana cultivation?

That answer runs through three centuries of American business: from post–Civil War seed salesmen, to the rise of the suburban lawn as a status symbol, to big-box retail turning shelf space into power, to the cannabis green rush—where the smartest money often isn’t in the plant, but in the picks and shovels around it. Along the way, we’ll hit the themes that make this story so rich: category creation, distribution dominance, high-conviction capital allocation, and the strange intensity that comes with a family-run empire.

Today, with roughly $3.4 billion in sales, Scotts Miracle-Gro is still the leading marketer of branded consumer lawn and garden products in North America. Its portfolio is a roll call of household names—Scotts®, Miracle-Gro®, Ortho®, and Tomcat®—brands that practically define the aisle at Home Depot and Lowe’s.

But behind those familiar labels is a company that took a swing at an industry that remains federally illegal, rode a pandemic-driven lawn and garden boom that briefly made everything look brilliant, and then had to face what happens when the hype fades and the bills come due.

The central paradox is irresistible: how does a business synonymous with suburban conformity—the cultural obsession with a perfect green lawn—end up as a kingmaker for an industry long associated with counterculture?

II. The O.M. Scott Origins & Building an American Lawn

In 1866, a young Civil War veteran named Orlando McLean Scott arrived in Marysville, Ohio, a small town northwest of Columbus. Like a lot of men coming home from a brutal war, he was looking for a clean restart. He found it in something deceptively simple: seeds.

Two years later, in 1868, Scott founded what would become the O.M. Scott Company. He ran a hardware store in town and began selling premium, weed-free seed to local farmers. And from the beginning, the business had a point of view. Company lore would later describe Scott as having a “white-hot hatred of weeds.” It sounds like a slogan, but it was really a philosophy: purity, consistency, control. Those instincts would echo through everything Scotts later became.

For the first few decades, Scotts served farmers who wanted clean fields and predictable crops. But the next big leap didn’t come from a new fertilizer or a new seed variety. It came from a change in American life—and from Scott’s son, Dwight.

In 1907, Dwight Scott saw where the country was heading. America was urbanizing. Early suburbs were forming. And grass was starting to mean something different. It wasn’t just what grew between rows of corn; it was what sat in front of your house. A lawn was becoming a kind of proof: that you’d made it, that you belonged, that you were keeping up.

Scotts began building a lawn grass seed business for homeowners in the early 1900s. Then, in 1924, it became the first company to ship grass seed products directly to stores. That might sound mundane now, but it was a meaningful shift: Scotts was moving away from the farm and toward the consumer. It was the company’s first real reinvention, and it set them up perfectly for the century-defining wave that was about to hit.

After World War II, the United States didn’t just grow. It reorganized itself. Suburbia exploded, and with it came a new kind of social expectation. The perfect lawn became a symbol of the American dream—your own home, your own patch of land, and the quiet obligation to make it look right.

As Abe Levitt—who, with his two sons, built the Levittowns that came to define postwar suburbia—put it: “A fine lawn makes a frame for a dwelling. It is the first thing a visitor sees. And first impressions are the lasting ones.”

Levittown, which began in 1947, wasn’t just mass-produced housing. It was mass-produced normalcy, right down to the landscape. The Levitts built homes at industrial scale, Ford-style—but they also standardized what “home” looked like from the street. And at the center of that picture was grass.

Scotts rode this cultural shift with unnerving precision. The company kept innovating and packaging expertise into products that ordinary homeowners could use. It introduced Turf Builder fertilizer in 1928. It created the first pre-emergent crabgrass control with Halts in 1958. And it pioneered weed-and-feed combination products—simplifying lawn care for people who didn’t have time to become amateur agronomists.

By the early 1970s, Scotts had become the dominant force in consumer lawn care. Then it got swept up in the conglomerate era. In 1971, O.M. Scott & Sons was acquired by ITT under Harold Geneen, who reportedly decided to buy the company after a 15-minute look at its balance sheet. That chapter didn’t last forever. In 1986, Scotts was bought back through a leveraged buyout.

And then came the public markets. In 1992, the company went public on the NASDAQ, opening at $19 per share. Scotts was no longer just a family-rooted operator, and no longer a cog inside a conglomerate. It was now on the clock—answering to shareholders, living quarter to quarter, with all the pressure that brings.

For investors, this early history matters for a reason that has nothing to do with nostalgia. Scotts didn’t simply build a product line. It attached itself to an aspiration. The American lawn became tied up with homeownership, success, and belonging—and Scotts positioned itself as the brand that could deliver that feeling in a bag.

III. The Miracle-Gro Merger & Building Distribution Dominance

While Scotts was turning grass into a suburban obsession, a very different kind of lawn-and-garden success story was taking shape on Long Island—one built not on seed science, but on direct response marketing.

In the late 1940s, a nurseryman named Otto Stern was running a small but profitable mail-order plant business. His partner was Horace Hagedorn, an advertising executive who knew how to get products into people’s homes and, more importantly, into their heads. Stern started slipping a little sample of water-soluble fertilizer into each shipment—just enough to help customers’ plants survive the shock of transplanting and, ideally, make them feel like gardening geniuses. It worked. Before long, customers weren’t writing in for more plants. They were writing in for more of the “growth agent.”

In 1950, Stern and Hagedorn decided to sell the fertilizer itself. Hagedorn named it Stern’s Miracle-Gro, and he marketed it with the instincts of someone who’d come up selling radio time at NBC. The pitch was simple, visual, and repeatable: blue crystals that dissolve in water and make plants grow like crazy. Miracle-Gro became one of those rare consumer products that didn’t just sell—it lodged itself in American culture.

By the early 1990s, Scotts and Miracle-Gro were powerhouses in adjacent worlds. Scotts owned lawns. Miracle-Gro owned gardens. Each had a category-defining brand, and each faced the same reality: these were big businesses, but they weren’t infinite-growth businesses. Together, though, they could be something much larger—and much harder for anyone else to challenge.

In January 1995, The Scotts Company announced a merger with Stern’s Miracle-Gro Products, Inc., valued at $200 million in stock. The deal closed later that year, after a settlement with the Federal Trade Commission over antitrust concerns around concentration in lawn and garden.

But the most important detail wasn’t the price. It was who ended up in control.

As Horace’s son Peter would later put it, “We scared them so bad with it that they had to buy our company, by essentially giving us 40 percent of their stock.” Horace credited another son—Jim—for pushing the structure: stock only. The result was that the Hagedorns didn’t just join Scotts. They arrived with real leverage. Horace even told the Wall Street Journal, “The truth of the matter is, Scotts didn’t buy Miracle-Gro … we bought Scotts.”

Then they acted like it.

Early in 1996—barely a year after the merger—Horace Hagedorn and the board forced out Scotts CEO Theodore Host. They brought in Charles M. Berger, previously a Miracle-Gro director and an executive from H.J. Heinz, as president, CEO, and chairman. A reshuffle followed: Jim Rogula took over Scotts’ largest segment, Consumer Lawns; John Kenlon ran Consumer Gardens; and Horace’s son Jim was promoted to lead all U.S. business.

The combination was powerful on paper and even more powerful in the aisle. Scotts’ fertilizers and lawn treatments now sat under the same corporate umbrella as the country’s most recognizable plant food. Cross-selling was obvious, scale advantages were real, and by the late 1990s the combined company was generating more than $1 billion in annual sales.

But the merger’s real unlock wasn’t just revenue. It was distribution.

With the two most trusted brands in their respective categories under one roof, retailers couldn’t afford not to carry them. And Scotts Miracle-Gro understood exactly what that meant: if you control the shelf, you control the category.

The rise of big-box retail in the 1990s turned lawn and garden into a winner-take-most game. Home Depot, Lowe’s, and Walmart became the gatekeepers. In 2018, those three retailers accounted for roughly 60% of Scotts’ sales. That concentration created enormous reach—and enormous dependency. Scotts’ business was also intensely seasonal, with about three-quarters of annual net sales landing in its second and third fiscal quarters. Home Depot and Lowe’s were the two biggest customers, and each represented more than 10% of consolidated net sales in the three most recent fiscal years.

This was the trade. When spring hits, Scotts can move mountains through the channel. But if a key retailer sneezes, Scotts catches a cold.

To widen its grip on the aisle, the company kept buying brands that filled out the “complete solution” for homeowners. It acquired Ortho, founded in 1907. And then it struck the deal that became both a profit engine and a reputational lightning rod: Roundup.

In 1999, Scotts (through a subsidiary) became Monsanto’s exclusive agent for marketing and distributing Roundup non-selective herbicides in the consumer lawn and garden market in the U.S. and select international markets. Later, Scotts paid Monsanto $300 million for the Roundup brand license, along with an extended agency agreement and a technology-sharing agreement—deepening a partnership that would make Scotts even more central to how big-box retailers stocked weed control.

For investors, this is the moat. Scotts doesn’t just sell fertilizer and grass seed. It owns a disproportionate share of the space where Americans buy them—and in consumer packaged goods, shelf space is power. Once you’ve earned it, and once retailers build their category around you, it becomes brutally difficult for anyone else to take it away.

IV. The Hagedorn-to-Hagedorn Transition & Business Model

Jim Hagedorn took over as CEO in 2001. In January 2003, he added the chairman title, too. On paper, it was a clean, second-generation handoff. In practice, it marked a shift in temperament: the company moved from Horace Hagedorn’s marketer-builder era into Jim’s operator-dominator era.

Jim had been steeped in this world his entire life. Horace had launched Miracle-Gro in the early 1950s, and Jim grew up watching the brand earn trust one backyard at a time. He also helped engineer the 1995 merger that effectively stitched “lawn” and “garden” into one empire. And before he ever ran a public company, he spent seven years in the U.S. Air Force as an F-16 fighter pilot.

That last detail isn’t just colorful biography. It’s a clue. Jim brought a pilot’s mindset to the corner office: decisive, competitive, and comfortable making bets that other executives would talk themselves out of.

Under his leadership, Scotts refined what observers came to call “the Scotts playbook”: own the shelf, own the season, own the category.

First: brand ubiquity, powered by relentless marketing. Scotts poured hundreds of millions of dollars a year into advertising. The goal wasn’t simply awareness. It was muscle memory. When spring arrived and people stood in the aisle staring at a wall of green bags and bright bottles, Scotts wanted the choice to feel automatic.

Second: retailer relationships that looked less like vendor arrangements and more like category management. Scotts didn’t just ship pallets to Home Depot and Lowe’s; it helped run the lawn and garden aisle—forecasting demand, servicing displays, keeping product in stock, and smoothing the chaos of spring. Jim would later describe the pitch he heard back from retailers, especially when they were pressing him on size and influence: why would they let you get this big? His answer was straightforward: because Scotts brought the brands, brought the advertising that drove traffic into the store, and executed “pretty flawlessly.” In other words, Scotts made the retailers’ lives easier, and that earned it power.

Third: seasonal dominance. Lawn and garden is a business where spring isn’t just a good quarter—it’s the quarter. Roughly three-quarters of annual sales arrive across the spring and early-summer window. That kind of seasonality turns operations into a high-wire act: you have to manufacture, ship, and stock at massive scale, with little room for error, and with demand heavily influenced by the weather. Scale incumbents can do that. Smaller challengers often can’t.

Put those pieces together and you get why Scotts compounded for so long. Strong brands supported premium pricing. Distribution dominance kept those brands unavoidable. Scale lowered costs in manufacturing and marketing. And the seasonal complexity acted like a moat, protecting margins from would-be entrants.

The Roundup relationship with Monsanto captured both the upside and the risk of this approach. It was a profit engine and an aisle anchor, but it also increased Scotts’ dependence on a product it didn’t manufacture and a partner whose reputation was becoming more complicated. As Jim put it, a significant percentage of Scotts’ profitability was tied to the existing Roundup business, even as changes to the relationship promised “exciting growth potential” and a “more secure future.”

By the mid-2000s, the Hagedorn-era lesson was clear: Scotts wasn’t just selling bags of fertilizer. It had built a machine for winning a category.

And machines like that are incredible—right up until the category stops growing. The looming question was simple and ominous: what happens when the lawn boom ends?

V. Peak Lawn: The 2008 Crisis & Searching for Growth

The 2008 financial crisis didn’t just crater home prices. It shook the entire suburban ladder that Scotts had been climbing for decades. When the value of a house is falling—or when you’re worried you might lose it—bagging fertilizer and babying the front yard stops feeling like a priority.

For Scotts, it exposed an uncomfortable truth: the company wasn’t just in the lawn business. It was in the housing business, whether it admitted it or not. New home formation meant brand-new lawns to seed and feed. Rising home values made landscaping feel worth it. And the constant churn of people moving created a steady “reset” cycle: new owners, new projects, new purchases.

When those three forces reversed at the same time, Scotts didn’t just face a bad season. It had to confront a scarier possibility—maybe the lawn itself was peaking.

The signals weren’t great. Millennials, who would eventually become the biggest pool of would-be homeowners, weren’t showing the same devotion to chemically perfect turf. Concerns about fertilizers, pesticides, water use, and biodiversity were moving from the fringe into the mainstream. At the same time, more Americans were living in places where a traditional lawn simply wasn’t part of the deal—apartments, condos, smaller lots, denser cities. And culturally, the flawless green rectangle was starting to look less like a status symbol and more like a relic.

A 2020 CNN report put the scale into perspective: residential lawns cover about two percent of U.S. land—around 49,000 square miles, roughly the size of Greece—and they require more irrigation than any agricultural crop grown in the country. Unsurprisingly, more homeowners were experimenting with alternatives: converting grass into gardens, planting for pollinators, using less water, and cutting back on harsh chemicals.

So the strategic dilemma got painfully clear: how do you grow a lawn care giant if the lawn is no longer a guaranteed cultural institution?

Scotts went looking for adjacent growth. One attempt was Scotts LawnService, its professional lawn care division. It scaled quickly, growing from $41.2 million in revenue in fiscal 2001 to $230.5 million in fiscal 2007. Another lever was international expansion. But outside North America, Scotts never built anything close to the dominance it enjoyed at Home Depot and Lowe’s.

These moves helped at the margins. None of them looked like the next act.

And in a public company, “the next act” isn’t a nice-to-have—it’s the job. Scotts needed a new growth engine, something big enough to matter.

Jim Hagedorn started to see it somewhere no one expected.

In 2011, with 16 states allowing medical marijuana, Hagedorn told The Wall Street Journal, “I want to target the pot market. There’s no good reason we haven’t.” It was a startling thing for the CEO of Scotts to say out loud. But it was also a glimpse of how he was thinking: cannabis was an emerging agricultural category, and Scotts already knew how to help plants grow—nutrients, lighting, hydroponics, the whole “picks and shovels” toolkit.

Of course, it also came with baggage. Cannabis was still federally illegal, heavily stigmatized, and wildly out of character for a company built on suburban respectability.

But this is where Jim Hagedorn’s personality mattered. The former fighter pilot who helped engineer the Miracle-Gro merger wasn’t looking for a safe adjacency. He was looking for the next battlefield. And he was increasingly convinced this was it.

VI. The Hawthorne Gamble: All-In on Cannabis

The story of how America’s most conservative lawn care company became a cannabis kingmaker starts, improbably, in Yakima, Washington.

In 2013, Jim Hagedorn walked into a garden store there and found something that didn’t fit the usual script. One corner of the shop was packed with hydroponic gear—tanks, nutrients, pumps, lights. And it wasn’t moving because people were suddenly obsessed with exotic lettuce. It was moving because growers were building indoor cannabis operations, and they needed supplies.

To Hagedorn, it looked like a growth market hiding in plain sight—one that mapped cleanly onto Scotts’ strengths. Scotts didn’t need to sell the plant. Scotts could sell everything around the plant.

That idea became Hawthorne Gardening Company. Formed in October 2014, it was Scotts Miracle-Gro’s dedicated subsidiary for hydroponic growers—effectively, cannabis growers. Hawthorne was built to speak their language, marketing itself with the tone of the “free-spirited, artisanal cannabis farmer,” even as it sat inside a very traditional public company.

The first big move came in April 2015: Hawthorne bought General Hydroponics, a roughly 35-year-old maker of liquid nutrients that High Times called “the standard for hydroponic growers.” The deal—about $130 million—was Scotts’ largest acquisition in 16 years, and it lit up online cannabis forums immediately. Not least because a Hawthorne executive said the quiet part out loud afterward: “the lion’s share” of General Hydroponics’ North American business was cannabis.

That purchase was just the opening bid.

What followed was one of the most aggressive consolidation campaigns in the hydroponics industry. Hawthorne kept rolling up brands across the grow room: lighting, nutrients, systems, and environmental controls. It bought 75% of lighting provider Gavita International, reportedly investing about $120 million. On October 3, 2016, it acquired Botanicare, an Arizona-based producer of nutrients, supplements, and hydroponic growing systems. Along the way, it picked up other brands like Agrolux and Vermicrop. And when it added Can-Filters—fans, filtration, air movement—Hagedorn called it “the top hydroponic brand in air movement and filtration systems.”

The crown jewel came in 2018, with the acquisition of Sunlight Supply, the largest hydroponic distributor in the United States. Scotts framed it as a scale play: a combined business with annualized sales of around $600 million, directly servicing more than 1,800 hydroponic retail stores across North America. The transaction was valued at $450 million, including $25 million of Scotts Miracle-Gro equity.

This was the thesis made real: build a one-stop “picks and shovels” empire for cannabis cultivation—nutrients, lighting, growing systems, ventilation, and, crucially, distribution. Hawthorne didn’t have to touch cannabis itself, which remained federally illegal and could have jeopardized Scotts’ NYSE listing. It just had to become the supplier the industry couldn’t run without.

By the time Can-Filters was in the fold, Scotts had invested $565 million since March 2015 to assemble the portfolio. And it wasn’t funded with spare change. The buying spree was financed primarily with debt—fuel that would burn cleanly on the way up, and then become suffocating if the market turned. Between fiscal 2014 and fiscal 2018, Scotts’ debt climbed from about $700 million to $1.9 billion, and debt became a far larger share of the company’s capital structure.

Inside Scotts, the way this happened was just as telling as what happened. This wasn’t a slow-motion strategy shift blessed by consultants and boardroom unanimity. It was a conviction bet—driven by a CEO who believed he was seeing the next wave early, and who didn’t intend to watch from the shore.

As one profile put it, Hagedorn insisted it “wasn’t a ‘Whoops!’—it’s how we felt at the time.” He spoke in the blunt, profane style that made him hard to mistake for a typical CPG chief executive, the son of the man who launched the original Miracle-Gro in 1951 and now willing to drag the family empire into a federally illegal market.

Critics—inside the company and among shareholders—had predictable questions. What was a lawn care company doing in marijuana? Was this a distraction? What if federal legalization never came?

Hagedorn’s answer was equally predictable. This was the next billion-dollar business. And he was willing to bet his reputation on it.

The fighter pilot wasn’t circling. He was flying straight into the storm.

VII. The Cannabis Boom, Bust & Reality Check

For a few glorious years, Jim Hagedorn looked vindicated. Hawthorne surged alongside the cannabis industry and, by 2021, grew to nearly 30% of Scotts’ sales—before the air came out in 2022. Canada legalized nationwide. State after state moved from medical to recreational. Federal legalization felt less like a question of if, and more like when.

And Hawthorne was perfectly positioned for the moment. Cultivators were racing to build massive indoor grows, and every square foot needed the same stuff: lights, nutrients, ventilation, growing media. Scotts didn’t have to touch the plant to ride the wave. It just had to keep shipping the gear. For a while, the orders didn’t stop.

But the boom carried the seeds of its own collapse. Cannabis cultivation economics turned out to be brutally volatile. Oversupply slammed wholesale prices. Legal operators got squeezed by heavy taxes, while illicit supply kept thriving under the price umbrella. Then COVID arrived. At first, demand jumped as stuck-at-home consumers bought more. But the bigger effect was on the supply side: the industry kept building, and that overbuilding would haunt growers for years.

By the time Scotts was reporting results, the tone had changed. Supply chain problems, inflation, and consumers pulling back hit Hawthorne hard. In one second quarter, Hawthorne sales fell 44% to $202.6 million, and Scotts’ overall sales declined 8% to $1.68 billion. Chris Hagedorn, Hawthorne’s general manager, called it “a perfect storm,” pointing to oversupply in markets like California and Oklahoma and rising input costs from inflation.

Then the slide turned into something closer to a free fall. Scotts said it would take “decisive steps” to improve margins and cash flow in fiscal 2023—while also negotiating with lenders for a temporary increase in the leverage ratio permitted under an amended credit facility.

The human cost showed up fast. Over roughly 18 months, Hawthorne laid off about 1,000 employees. The business kept shrinking—down 40% in the quarter ending July 1, dragging Scotts’ overall sales down 6% with it. And in what became the defining image of the bust, Scotts sent about $200 million worth of unsold grow lights to a landfill because there was no demand and nowhere to store them.

That landfill story became a symbol because it punctured the comfort of the “picks and shovels” thesis. Yes, suppliers can profit without taking regulatory risk on the plant. But they still live and die by the same cycle. When the gold rush ends, shovel makers don’t get spared.

All of this landed on top of the financial structure Scotts had used to build Hawthorne in the first place. The company had borrowed heavily over the decade, alongside headline acquisitions like California-based General Hydroponics. The balance sheet strain became impossible to ignore. Scotts warned its leverage ratio of debt-to-EBITDA would likely exceed 6.0 times at fiscal year-end—still in compliance with the covenants in its amended credit facility, but far from the steady, predictable profile investors expected from a lawn-and-garden compounder.

For Jim Hagedorn, the crash was painful, but it didn’t kill the core belief. He and his son Chris began mapping out a strategic shift: how to remake Hawthorne into something that could stand on its own, and how to bring in partners—including other cannabis companies—to help stabilize and rebuild.

The response revealed both how deep the hole was and how unwilling the Hagedorns were to simply walk away. Instead of folding Hawthorne back into the core business and treating it as a mistake, they explored ways to separate it while keeping the upside if federal legalization ever materialized.

“We’ve said as much publicly, but I think the interesting part of the conversation is why?” Jim Hagedorn said. “(Scotts will) keep the debt. You move it without any debt at all. So completely clean. Hundreds of millions of inventory and upward capital.” In other words: a Hawthorne spin could put the cannabis business on its own footing, while Scotts absorbed the financial baggage.

The cannabis bet didn’t destroy Scotts Miracle-Gro. But it came close—and it forced questions that were bigger than Hawthorne itself: about capital allocation, about governance, and about what happens when a conviction-driven leader takes a legacy company into a market that doesn’t behave like anything it’s ever known.

VIII. COVID Chaos & The Great Lawn Renaissance

Just as the Hawthorne crisis was intensifying, an unlikely savior appeared: COVID-19. The same pandemic that shut down offices, canceled travel, and scrambled supply chains also pushed millions of Americans back into their yards. And for Scotts’ core lawn-and-garden business, it was rocket fuel.

Jim Hagedorn said the company picked up around 20 million new customers during the pandemic—and the new mission was to keep them. People stuck at home started planting, mowing, feeding, and fixing up outdoor spaces they’d previously ignored. Even Hawthorne felt a bump as growers kept building and upgrading.

The surge showed up fast in results. For the year ended September 30, 2020, company-wide sales jumped 31% to a record $4.13 billion, up from $3.16 billion the year before. The momentum continued into fiscal 2021, when sales rose another 19% to $4.93 billion.

The seasonality that normally defined Scotts also started to bend. The company, which typically lost money in its first fiscal quarter, posted a first-quarter profit for the first time. In the quarter ended Jan. 2, sales more than doubled year over year to $748.6 million, and diluted earnings per share swung to a $0.43 profit from a $1.28 loss a year earlier. Investors piled in. Scotts’ stock hit fresh highs, rising above $240 per share and briefly trading as high as $250, after climbing nearly 94% over the prior 12 months.

Chris Hagedorn summed up the moment with the kind of line only the Hagedorns would use: “If people are stuck at home, what are they going to do? They smoke a joint and go garden.” Crude, but directionally accurate. Gardening wasn’t just a hobby again; it became therapy, entertainment, and, for some people, a small form of self-reliance. Victory gardens returned. Container gardening took off. Demand for soils, fertilizers, and lawn products surged past anything Scotts had planned for.

Operationally, Scotts stayed open because its work was deemed essential. Fertilizer mattered to the food system, and the retailers that sold Scotts products were largely considered essential, too. But “open” didn’t mean “normal.” Scotts paid workers 50% more, shifted from three eight-hour shifts to two 12-hour shifts to make better use of staffing, and if someone got sick, an entire shift could be sent home. By July 2020, Scotts said its consumer business sales were up more than 20%.

Then came the hangover.

The same demand spike that made Scotts look unstoppable also made planning almost impossible. Scotts ramped up production for what it expected would be its biggest summer ever, only to find that retailer orders didn’t materialize the way it anticipated. The company spent the next two years whipsawed between trying to keep lawn seed and fertilizer on shelves, and then trying to deal with too much product.

In hindsight, it was the classic mistake: treating a once-in-a-generation demand shock like a new baseline. In November 2021, executives said inventory levels were in a good place. But by the end of 2021, total inventory was up 55% compared with pre-pandemic levels. When restrictions eased and consumers drifted back toward pre-COVID routines, Scotts found itself sitting on piles of unsold goods.

That whiplash—from shortage to glut—hit at exactly the wrong time. Hawthorne was already collapsing. Now the core business, which had been the stabilizer, was facing its own operational and financial stress.

By fiscal 2021 and 2022, Scotts was living a dual narrative that was almost impossible to manage cleanly: the core business had just printed record numbers, then stumbled under the weight of volatility; Hawthorne was shrinking fast. The turbulence fed directly into changes at the top. Jim Hagedorn, then 68, chairman and CEO, took on the additional duties of president following executive retirements. And Matt Garth, who joined the company in December 2022 as executive vice president and CFO, was given an expanded role as chief administrative officer.

For investors, COVID clarified something important about Scotts. The brands were powerful enough to pull in tens of millions of new customers almost overnight. But the business also wasn’t built for a world where demand could swing violently in either direction. The pandemic made Scotts look invincible—and then immediately reminded everyone how hard it is to run a highly seasonal, retailer-dependent machine when the entire world stops behaving normally.

IX. The Modern Era: Portfolio Rebalancing & New Strategy

The post-pandemic hangover forced a reckoning at Scotts Miracle-Gro. A company that had flirted with the idea of cannabis becoming a massive second pillar was suddenly in triage mode: keep the core stable, stop the bleeding at Hawthorne, and get the balance sheet back under control.

Jim Hagedorn framed the moment as a reset. “The first quarter reflects our disciplined approach to reorient the business and strengthen the operational and financial performance of the Company,” he said. “We have further positioned ScottsMiracle-Gro for long-term growth and shareholder value. We are comfortably within our leverage requirement and expect to remain on this trajectory through the fiscal year. As for Project Springboard, we have line of sight to annualized savings above the initial $185 million target, creating opportunities to reinvest in the business.”

Project Springboard became the catch-all name for the unsexy work of right-sizing: cutting costs, simplifying operations, and undoing some of the overbuild that followed the COVID surge. The company targeted $185 million in annualized savings through headcount reductions, supply chain optimization, and operational efficiency. This wasn’t about finding a clever new product. It was about making the machine run properly again.

Even with those efforts, pressure on profitability didn’t magically disappear. Higher commodity costs and unfavorable fixed-cost leverage weighed on gross margins—driven largely by volume losses at Hawthorne and lower production volumes in the U.S. consumer business. Scotts tried to counterbalance that with price increases, earlier-than-planned distribution savings from Springboard, and a mix shift as the lower-margin Hawthorne business shrank. Project Springboard also helped drive a 17% reduction in SG&A.

Out of that mess, the new strategy hardened into three priorities: stabilize Hawthorne, refocus on the core consumer engine, and reduce debt.

Leadership messaging followed the same line. As the company worked to re-optimize the balance sheet, Hagedorn emphasized both a “turnaround” at Hawthorne and a renewed push in the consumer segment. “We’re poised to drive further expansion in the consumer segment while maintaining our focus on deleveraging and optimizing the balance sheet,” he said.

For Hawthorne, that meant a shift from conquest to containment—and, eventually, separation. The company said rescheduling would not alter its plan to strategically move Hawthorne into a cannabis-dedicated company as part of a broader strategy to focus on growth in the core consumer lawn and garden business.

Scotts also made clear it was seeking to separate from the cannabis industry by selling Hawthorne Gardening. It was a striking reversal after a decade of investment that, in total, saw Scotts spend nearly $2 billion building Hawthorne into a major supplier of hydroponics, nutrients, and cultivation equipment.

Then, in December 2025, cannabis rescheduling by executive order added a fresh twist. Scotts expressed support for President Trump’s executive order to move cannabis from Schedule I to Schedule III. “With 39 states already legalizing cannabis in some form, rescheduling to a lower level drug on the federal level has been long overdue,” Hagedorn said.

He also pointed to the business mechanics. “The 280E tax penalty has hindered the profitability of legal cannabis companies and forced many to go under,” Hagedorn said. “Rescheduling eliminates the penalty, bringing their tax rate in line with other American businesses and enabling them to shift more financial resources into capital investment and growth opportunities.” More investment by cannabis operators could, in turn, flow back to Hawthorne through equipment and supply purchases—exactly the “picks and shovels” logic that originally pulled Scotts into the space.

Meanwhile, the core consumer business began to look steadier. Hagedorn pointed to fiscal 2025 as a year of improved fundamentals: “In fiscal ’25, we delivered significant results in the financial metrics that are central to our growth plans,” he said. “We drove share gains, made substantial gross margin improvement and achieved meaningful EBITDA and EPS increases. The bigger story is the health of our consumer and resiliency of our category, as evidenced by our strong and sustained POS growth.”

The company reported GAAP earnings of $2.47 per share and non-GAAP adjusted earnings of $3.74 per share, with non-GAAP adjusted EBITDA of $581 million. Free cash flow was $274 million, and net leverage improved to 4.10x, down 0.76x versus the prior year.

And yet, the big picture still carried the scars. For the fiscal year ending September 30, 2025, Scotts reported annual revenue of $3.41B, down 3.93%. The decline reflected Hawthorne’s continued shrinkage, only partially offset by modest growth in the core consumer business.

This is the modern Scotts question: can the company pull off the rebalancing—shrinking or separating a volatile cannabis exposure, paying down the debt it took on to build it, and returning to the steady, distribution-powered playbook that made it dominant in the first place—without weakening the brand equity and retailer relationships that are still its real advantage?

X. The Business Model Deep Dive & Competitive Dynamics

To really understand Scotts Miracle-Gro, you have to understand the lawn-and-garden category it dominates. This isn’t a typical consumer packaged goods business where demand is steady and predictable. It’s seasonal, it’s weather-driven, and it runs on relationships with a handful of powerful retailers. In this world, distribution can matter as much as the brand on the bag.

Start with the calendar. Roughly three-quarters of Scotts’ annual net sales come in its second and third fiscal quarters. That means the company spends all year getting ready for a selling season that’s basically a sprint. Manufacturing, shipping, and merchandising have to be dialed in before spring hits. If Scotts builds too much, cash gets trapped in inventory and working capital swells. If it builds too little, the season passes and those sales are gone. There’s no “make it up next quarter” when the weather changes and customers move on.

That dynamic creates a quiet barrier to entry. A new competitor can’t just dream up a product and buy some ads. They have to fund months of production and logistics, win shelf space, and be ready to execute at scale during a short, high-stakes window. The seasonality isn’t just a headache—it’s part of the moat.

Then there’s the customer base, which is both a strength and a vulnerability. Scotts has significant customer concentration: as much as about 61% of sales comes from its top three customers. In practice, that means Home Depot, Lowe’s, and Walmart. Home Depot and Lowe’s are especially important—each individually represents more than 10% of sales in the most recent fiscal years.

That level of concentration gives retailers real leverage. They can pressure pricing, demand promotional dollars, and always hold out the threat of shifting space to private label. But it’s not a one-way relationship. Home Depot and Lowe’s also rely on Scotts’ brands to make their garden centers work. Those aisles need recognizable names that customers trust and actively come in to buy—especially in spring, when garden is supposed to be a traffic driver. Scotts’ job is to keep that machine stocked and humming; the retailers’ job is to keep giving it prime real estate.

Despite selling at a premium to many private-label alternatives, Scotts has held onto category leadership for decades. The simplest explanation is the old one: brand plus marketing plus execution. When consumers walk into a big-box store and face a wall of options, Scotts wants the decision to feel obvious. And because the company helps retailers manage the category—forecasting, merchandising, and keeping inventory flowing—it earns a kind of “preferred supplier” status that’s hard for smaller players to match.

Competition exists, but no one quite mirrors Scotts’ scale. Central Garden & Pet is the largest rival, with meaningful garden presence alongside its pet business. Spectrum Brands shows up in pest control. And there are plenty of regional and specialty players that can win niches. But none has Scotts’ combination of brand portfolio, big-box distribution relationships, and the operational muscle to serve a short selling season at national scale.

That’s why Scotts’ moat is often described as brand-driven. Scotts, Miracle-Gro, Ortho, Tomcat, and Roundup (licensed from Bayer) aren’t just products—they’re mental shortcuts for consumers, and they’re anchors for retailers building an aisle plan.

The harder, still-unfinished part of the story is the next generation of customers. Millennials and Gen Z tend to view lawns differently. Many are more skeptical of chemicals, more motivated by sustainability, and more likely to see lawn and garden as part of a broader “wellness” lifestyle—something tied to personal expression, indoor plants, pollinators, and the feel of a home, not just suburban upkeep. They also discover brands digitally first. They expect to interact online before they ever stand in an aisle, and they increasingly want purchases to reflect their values.

Scotts has tried to meet that shift with organic products and sustainability efforts, including a push into biological solutions as alternatives to synthetics. Miracle-Gro Organic is one example: it’s grown to about one-fifth of total soil sales, and the company has said much of the pull has come from newer consumers.

For investors, the core model is still powerful—but the headwinds are real. The tell is whether Scotts can keep the economics of the old machine—brand premiums, shelf dominance, strong gross margins—while updating the product mix and the messaging for how consumers now want to live. The numbers that most cleanly capture that are U.S. Consumer organic growth and gross margin: are people still buying, and can Scotts still make great money when they do?

XI. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MEDIUM

Breaking into consumer lawn and garden is hard, but not impossible. The biggest gate is still distribution. Home Depot and Lowe’s only have so much shelf space, and Scotts has spent decades earning the kind of trust—and in-aisle presence—that’s incredibly difficult for a newcomer to displace. Then there’s the brand layer: when people are staring at a wall of similar-looking bags in April, they default to the names they recognize. On the chemical side, the EPA registration process adds another real barrier, slowing down launches and making “move fast and break things” basically impossible.

But the moat has hairline cracks. Direct-to-consumer has lowered the cost of getting a product in front of customers, and niche organic brands have built real momentum with consumers who actively want alternatives to the mainstream chemical playbook. The entry threat is more credible in growing media, soils, and organics than it is in regulated chemical lawn care, where the compliance burden is highest.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM

Scotts relies on core inputs like urea, phosphates, and potash—commodities with prices set by global markets, not by Scotts. That means cost volatility is part of the job, and it can get painful when prices spike at the wrong time. Scotts also can’t always pass those increases through immediately, especially when the spring season is underway and pricing and promotions are effectively already agreed with retailers.

And then there’s Roundup. The Monsanto/Bayer relationship is the cleanest example of supplier leverage here: Scotts markets a product it doesn’t own under a license, and that product has historically been an important profit contributor. When a meaningful chunk of your economics runs through someone else’s brand and terms, supplier power is real.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

This is the structural pressure point in the whole model. When your top three customers account for more than 60% of your sales, they’re not “accounts,” they’re gravity. Home Depot, Lowe’s, and Walmart can push hard on pricing, demand promotional spend, and ask for favorable terms or exclusives. And the private-label threat is always sitting right there: if they want to squeeze margin, they can try to swap shelf space toward their own products.

Scotts pushes back with its own leverage—brand pull. Retailers want names that customers come in asking for, especially in spring, when lawn and garden is supposed to drive traffic. But even with that advantage, the imbalance is baked into the channel.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

The biggest substitute isn’t another bag of fertilizer. It’s the idea that maybe you don’t need a traditional lawn at all. Xeriscaping, native plant gardens, clover lawns, and “no-mow” approaches appeal to homeowners who care about water use, biodiversity, and chemical exposure. On top of that, professional services like TruGreen can replace the DIY routine entirely. And for a growing share of the population living in denser housing, the ultimate substitute is simple: no yard, no lawn category, no purchase.

These are structural shifts—changes in lifestyle and values—not just competitive moves. That makes them harder to fight with marketing and endcaps.

Competitive Rivalry: MEDIUM

In the core business, rivalry is real but not cutthroat. Scotts is the clear leader, and while competitors like Central Garden & Pet, Spectrum Brands, and store brands nibble around the edges, none consistently threatens Scotts’ overall category position. That’s part of why the core business has historically supported strong margins.

Hawthorne was the opposite environment: fragmented, fast-moving, and intensely competitive, which only amplified the boom-bust dynamics when the cannabis market turned. But in traditional lawn and garden, rivalry tends to stay at a level where the big players can still make money—especially if they control the shelf.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG in Core Business

In the core lawn-and-garden machine, Scotts gets real scale benefits in three places: making the stuff, marketing the stuff, and moving the stuff. A national ad campaign costs roughly the same whether you’re selling $2 billion or $4 billion, so the bigger you are, the more efficient that spend becomes. On the manufacturing side, volume lets you run plants harder, keep quality consistent, and spread fixed costs in a way smaller competitors can’t. And in distribution, massive spring throughput justifies the logistics, systems, and retailer support that make Scotts so hard to dislodge.

Hawthorne never really got to enjoy those same advantages. The hydroponics market stayed fragmented, and the cannabis boom ended before consolidation could translate into the kind of steady, repeatable scale economics Scotts had perfected in the core business.

Network Effects: NONE

This isn’t a network business. Your lawn doesn’t get greener because your neighbor also bought Turf Builder.

Counter-Positioning: N/A

Scotts is the incumbent. Counter-positioning is more useful for understanding how a new entrant might attack Scotts than it is for explaining why Scotts wins today.

Switching Costs: LOW-MEDIUM

For consumers, switching costs are low. Trying a different fertilizer or grass seed is easy, and in many cases the downside is limited to one season of “meh” results. Where switching gets stickier is at the retailer level. Replacing Scotts at Home Depot or Lowe’s isn’t just swapping SKUs—it’s reworking planograms, changing how the category is merchandised, retraining staff, and taking a real risk that traffic drops if shoppers don’t see the brands they came for. And for many long-time homeowners, loyalty is less a contractual lock-in than a deeply ingrained habit.

Branding: STRONG

This is the bedrock power. Scotts, Miracle-Gro, Ortho, and Tomcat aren’t just recognizable—they’re default choices. Decades of marketing turned these names into shortcuts in the aisle: if you don’t want to think too hard, you buy the one you’ve heard of. That brand pull matters to retailers too. They give prime shelf space to the products that people actually come in asking for.

Cornered Resource: MEDIUM

Roundup was a classic cornered resource: exclusive access to a brand with enormous consumer awareness. The catch, of course, is that it also carried reputational risk as Bayer/Monsanto litigation became a major overhang. Beyond Roundup, shelf space itself is a kind of cornered resource. There’s only so much real estate in a garden center, and Scotts has spent decades securing a disproportionate share of it.

Hawthorne tried to manufacture a similar advantage by buying up key hydroponics brands and distribution. But the industry didn’t consolidate the way Scotts expected, and the market’s boom-bust cycle kept that “corner” from ever feeling permanent.

Process Power: MEDIUM

Scotts has hard-earned operational skill in running an extremely seasonal business: forecasting demand, getting product built and shipped ahead of spring, keeping retailers stocked through surges, and managing the whole category with a level of discipline that becomes invisible when it works. None of this is proprietary technology—but it’s still a real advantage, because replicating it takes years of investment, relationships, and clean execution.

Overall Assessment:

In the core business, Scotts’ powers stack neatly: brand strength plus distribution scale, reinforced by processes built for a brutal seasonal sprint. That combination should keep the company in a strong position for a long time, even as consumer preferences slowly shift toward organics and alternatives to traditional lawns.

Hawthorne is the counterexample. It absorbed capital and attention, but it didn’t build new durable powers—and it didn’t consistently benefit from the ones Scotts already had. That’s the warning embedded in the story: adjacency moves only work when they let you press your existing advantage harder, not when they pull you into a market that plays by completely different rules.

XIII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The Distribution Moat Still Matters

Scotts is a reminder that even in the age of “everything goes online,” physical distribution can still be a superpower. Fertilizer, soil, and mulch are heavy, messy, and expensive to ship. Most people want to grab them while they’re already at Home Depot or Lowe’s, and they want packaging they can see and compare in the aisle.

The bigger edge is operational, not just logistical. Keeping the right product in stock across thousands of stores for a short, weather-driven selling season is brutally hard. That complexity acts like a barrier. Digital-first challengers can win pockets of the market, but it’s difficult to out-execute a company that has spent decades mastering the spring sprint.

Category Creation vs. Category Expansion

Hawthorne is the cautionary tale about adjacency bets that look obvious on a slide. Yes, cannabis cultivation uses nutrients, lights, ventilation, and growing media. And yes, Scotts knows how to help plants grow. But the business underneath was different.

Scotts’ core strengths—brand building for mass consumers, managing big-box retailers, running a seasonal machine—didn’t translate cleanly into hydroponics. The channel was different, the customer relationships were different, and competition was more fragmented and volatile. What seemed like a natural extension of “plant expertise” turned out to be a new game with new rules.

Founder Conviction: Blessing or Curse?

Jim Hagedorn’s cannabis push is a case study in conviction-driven leadership. He saw something early, committed hard, and didn’t blink when investors questioned the logic or the optics. That kind of belief can create enormous value when the thesis is right.

But conviction has a dark side: it can delay the moment when you admit the thesis is breaking. The same fighter-pilot decisiveness that helped build Scotts’ dominance also kept the company pushing into a market that turned against it. In this story, confidence was both the engine and the hazard.

Managing Mature Markets

When a core market starts to look “mature,” CEOs often feel forced to find the next big thing. Scotts did—and it found something enormous, just not something stable.

The lesson isn’t “never diversify.” It’s that the best move in a mature category is often to keep compounding the base: protect the moat, defend margins, refresh products, and explore adjacencies carefully. Scotts’ lawn and garden business ended up being more resilient than the narrative suggested. Hawthorne was the opposite: a growth engine that came with a cycle violent enough to threaten the whole company.

The Seasonality Challenge

A business that earns most of its money in a narrow window lives on a knife edge. Weather shifts, forecasting errors, and retailer decisions don’t just dent results—they can define the year. COVID made that painfully clear. Scotts swung from scrambling to keep shelves stocked to sitting on mountains of inventory, all because demand temporarily stopped behaving like demand.

Seasonality doesn’t just create volatility. It concentrates it.

ESG Before ESG

The environmental pressures facing traditional lawn care didn’t begin when ESG became a Wall Street acronym. Water use, chemical runoff, biodiversity, and climate-driven weather volatility have been building for years, and they directly challenge the ideal of the chemically perfect, always-green lawn.

Companies that treat these concerns as noise risk watching the category slowly erode. Companies that adapt—by shifting product mix, investing in alternatives, and meeting consumers where their values are moving—can turn the pressure into an advantage.

Capital Allocation Discipline

Scotts’ two stories—steady compounding in the core business and debt-fueled expansion in Hawthorne—teach the same lesson from opposite directions. Transformative M&A can work, but leverage turns a strategy bet into a balance-sheet bet. When the market goes your way, debt amplifies returns. When it doesn’t, debt removes your options.

And sometimes the highest-return move isn’t the bold new platform at all. It’s protecting the machine you already have—and returning cash—rather than swinging at a risky adjacency that doesn’t share your moat.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

The core lawn-and-garden business has been tougher than the bears expected. COVID didn’t invent demand out of nowhere, but it reminded everyone of something easy to forget: when Americans have time at home, they still care about their yards and gardens. Scotts said it added about twenty million new customers during the pandemic, and a big chunk of its base is still aging homeowners—the people who own most single-family homes and tend to keep the same seasonal lawn-care routines year after year.

The balance sheet story is also moving in the right direction. After years of debt-fueled expansion and then whiplash, Scotts has been working to stabilize and deleverage. CFO Mark Scheiwer put a clear stake in the ground: “Delivering on our adjusted EBITDA and free cash flow targets will enable us to exit 2025 with a significantly improved debt position that will put us on a path to realize our goal of getting leverage below 3.5 by the end of fiscal 2027.”

And then there’s Hawthorne. It’s no longer the rocket ship it once looked like, but it still offers optionality. If federal policy meaningfully shifts, the business could become a more attractive partner—or a more valuable asset—precisely because it sells the infrastructure around cultivation. As Hagedorn put it, “Reclassifying cannabis will set Hawthorne up for greater growth opportunities moving forward and make it a more attractive partner to a cannabis-dedicated company.”

Finally, the brand portfolio remains a real weapon. Scotts, Miracle-Gro, Ortho, and Tomcat are still the names that dominate the aisle, backed by decades of equity and distribution that competitors haven’t been able to crack. After years of underperformance, the stock can look inexpensive to believers—especially in an oligopoly-like category where scale and shelf space tend to protect margins.

Bear Case:

The bear argument starts with a blunt claim: the lawn category is in structural decline, and the market still isn’t pricing that in. Urbanization, shifting tastes toward alternative landscaping, and rising environmental concerns all push against the idea of chemically perfect turf. On this view, COVID wasn’t a new baseline—it was a one-time surge that pulled demand forward, making the years after look worse.

Then there’s cannabis. The harshest critique is that Hawthorne wasn’t just a bad cycle—it was permanent capital destruction, and Scotts should exit entirely rather than waiting on federal legalization that may never arrive, or may arrive too late to rescue the economics. The money spent rolling up hydroponics brands is, in this framing, money that won’t earn an adequate return.

Even after improvements, the balance sheet is still a constraint. Scotts invested nearly $2 billion in the venture, and the stock touched a pandemic-era high above $250 in 2021. But the cannabis market rolled over hard as overproduction crushed prices, and Hawthorne’s sales fell. That left the company with less room to maneuver than investors expect from a “steady” lawn-and-garden compounder.

Retailer concentration is another quiet risk that can become loud quickly. Scotts’ fate is disproportionately tied to a small handful of buyers. If Home Depot decides to push private label harder, or if the big boxes change how they allocate shelf space, Scotts can’t vote on that decision—it can only react to it.

Roundup remains an overhang, too. Scotts markets the product rather than manufacturing it, but consumers don’t always distinguish between licensee and owner. The association with Bayer/Monsanto litigation creates reputational risk, especially with shoppers already skeptical of chemicals.

And finally, there’s trust. The cannabis pivot damaged management credibility with many shareholders. Jim Hagedorn asked investors to follow him into a high-conviction bet—and the unwind destroyed billions in value. Even if today’s plan is more disciplined, bears argue the execution benefit of the doubt is gone.

Key Metrics to Watch:

The simplest way to track whether Scotts is getting back to “normal” is to watch two things:

-

U.S. Consumer Segment Organic Growth: This tells you whether the core engine is holding share, gaining share, or quietly decaying—and whether price/mix is doing real work.

-

Net Leverage (Debt-to-EBITDA): This determines flexibility. Management has targeted leverage below 3.5x by fiscal 2027. Movement toward that goal signals control; movement away from it signals the company is still fighting the balance sheet.

It’s also worth keeping an eye on Hawthorne as a percentage of total revenue. The smaller it gets, the less it can drag results down—but the less “option value” investors have if cannabis markets recover.

XV. Epilogue & What's Next

Scotts Miracle-Gro is sitting at a genuine inflection point. The company Orlando McLean Scott started 157 years ago to help farmers grow weed-free fields now has to choose what it wants to be in the next chapter. Not in a marketing-deck sense—in a capital-allocation, portfolio, and identity sense.

Scenario one is the simplest: stabilize and harvest.

In this future, Scotts keeps doing what it’s always been built to do—dominate consumer lawn and garden—while accepting that the category is mature and may slowly shrink. Hawthorne gets divested, separated, or wound down. Debt comes down. The company re-earns its reputation as a steady, seasonal cash generator with some of the strongest brands and distribution in North American retail. After the cannabis detour, plenty of shareholders would happily take “boring but profitable.”

Scenario two is the harder, more ambitious one: reinvent for the sustainability era.

Here, Scotts leans into what newer consumers are already signaling they want—organic, biological, and lower-impact products. That could mean becoming a leader in climate-adapted lawn care: drought-resistant varieties, organic fertilizers, and products that support healthier soils and biodiversity rather than fighting nature as an enemy. But this path isn’t just swapping ingredients. It requires real R&D, credible claims, and a brand repositioning that can’t feel like greenwashing.

Scenario three is the Wall Street-style outcome: breakup or acquisition.

In this version, a financial buyer or strategic acquirer decides Scotts’ brand portfolio and retailer relationships are worth more than the market is giving them credit for. The company is taken private, Hawthorne is separated and sold, and the core consumer engine is run with less quarterly pressure—optimizing margins, simplifying operations, and letting the seasonal machine do what it does best.

Hovering over all three scenarios is the federal cannabis question—whether, and when, policy shifts in a way that changes the economics for legal operators. That will influence Scotts’ options, but it likely won’t decide them. Even full legalization wouldn’t automatically restore the original Hawthorne thesis if cultivation stays structurally low-margin and commodity-like.

So what would we do if we were CEO? Probably something close to what the company is already signaling: protect and optimize the core consumer business; separate Hawthorne in a way that preserves upside without letting it drag the parent around; and invest selectively in sustainable products where Scotts can win with credibility and scale. The era of billion-dollar, conviction-driven swings should be over.

Because the American lawn—the cultural artifact born out of postwar optimism and suburban conformity—is changing. It’s not disappearing. There will always be homeowners who want a perfect green rectangle. But the meaning has shifted: from a universal aspiration, to a contested symbol, to something more personal, local, and values-driven.

And that’s why Scotts’ story sticks. A 150-year-old company, led for decades by a fighter-pilot CEO, placed one of the strangest big bets in consumer-products history—on an industry that was federally illegal—because he thought he understood where America was headed. He wasn’t wrong about the direction. He was disastrously wrong about the timing and the structure. Scotts survived anyway, and now it has to do the unglamorous work: simplify, deleverage, rebuild trust, and decide what kind of company it wants to be when the hype is gone.

It isn’t a clean story of triumph. It isn’t a tidy story of failure. It’s conviction, risk, adaptation, and resilience—exactly the mix that makes business history worth paying attention to.

XVI. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper on Scotts Miracle-Gro—both the 150-year backstory and the modern cannabis detour—here are ten sources that add real texture:

-

Scotts Miracle-Gro 10-K filings (2014-present) — The MD&A sections, especially on Hawthorne, show the strategy evolving in management’s own language, quarter by quarter.

-

"The Lawn: A History of an American Obsession" by Virginia Scott Jenkins — The cultural backdrop for why the American lawn became a national fixation, and why Scotts was perfectly positioned to build a business around it.

-

Jim Hagedorn's shareholder letters (2015-2021) — The clearest record of how the cannabis thesis was framed, defended, and then tested as the cycle turned.

-

"American Green: The Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Lawn" by Ted Steinberg — A sharper, more critical look at lawn culture, including the environmental and social tradeoffs that now shape the category’s future.

-

Cannabis Business Times — Solid coverage of Hawthorne and the cultivation supply chain, which helps explain why “picks and shovels” still ends up tied to boom-and-bust.

-

Barron's and WSJ features on Scotts' cannabis pivot (2016-2020) — Useful for capturing the real-time skepticism, excitement, and eventual blowback from investors and analysts.

-

Retail trade publications on big box gardening category dynamics — If you want to understand Scotts’ true moat, study the Home Depot and Lowe’s relationship: merchandising, shelf space, and category management.

-

Investor presentations and earnings transcripts (especially 2019-2020) — The candid version of the story: what management said when the market was moving fast and expectations were shifting under their feet.

-

Environmental critiques of the lawn care industry — EPA research and academic literature that lays out the sustainability pressures pushing consumers away from traditional chemical-first lawn care.

-

Morningstar and equity research coverage — A more clinical, investor-oriented view of competitive position, capital allocation, and what the business might be worth if it returns to “boring.”

Scotts’ story rewards the extra reading because it’s not just about fertilizer, or even cannabis. It’s about the hard stuff: how companies grow when their core market matures, when bold bets become balance-sheet problems, and how leaders decide whether they’re seeing the future—or projecting it. The ambiguity is the point. That’s why this one sticks.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music