SkyWest Airlines: Regional Aviation's Quiet Giant

I. Introduction: The Airline You've Flown But Never Booked

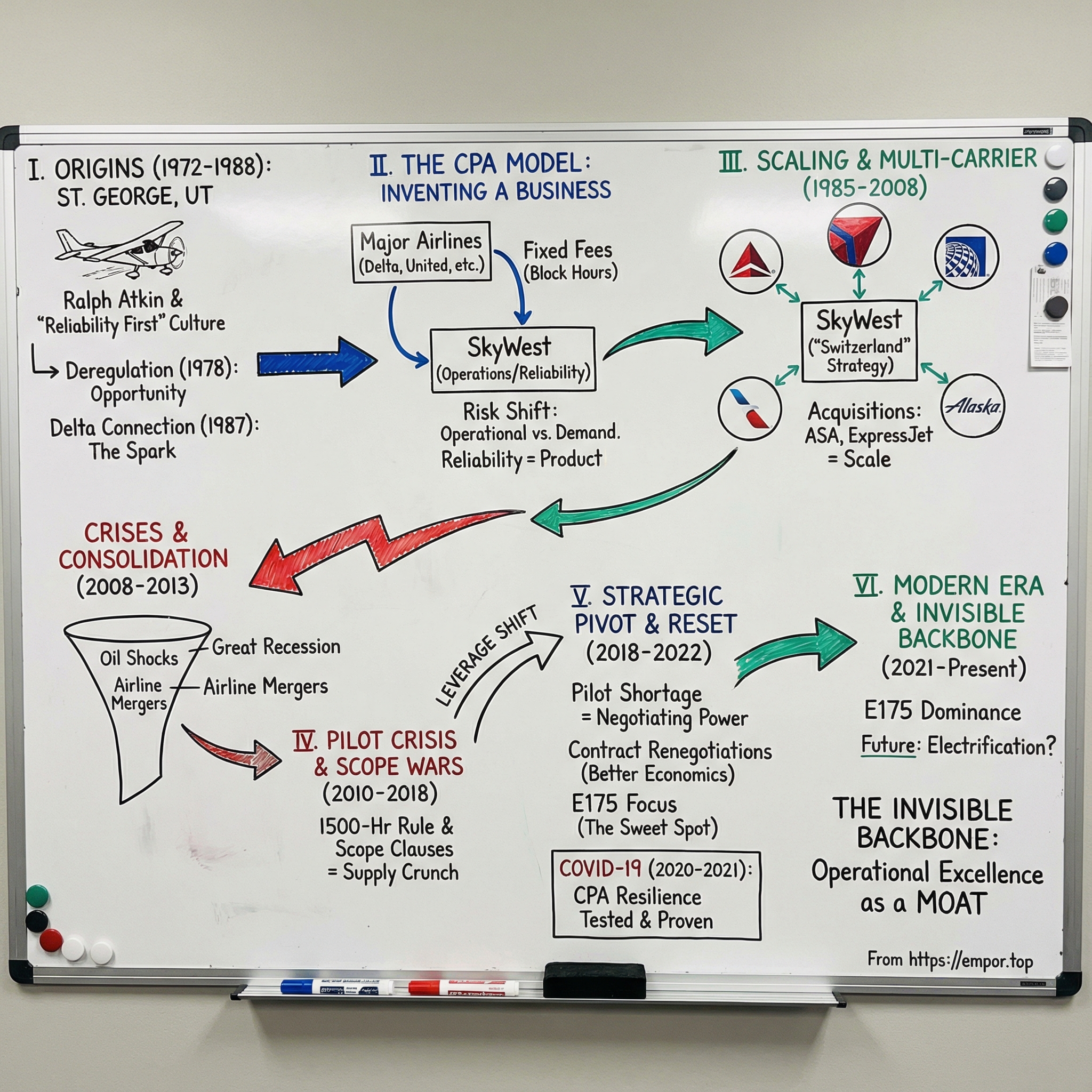

Picture yourself at Denver International Airport, hustling through Concourse B to make a flight to Casper, Wyoming. You glance at your boarding pass: United Express, Flight 5412. You slide into seat 7A on a sleek Embraer E175—two seats on each side of the aisle, surprisingly comfortable for a “regional” jet—and settle in for a quick hop over the Rockies.

Here’s the part most passengers never realize: the crew in the cockpit, the flight attendants in the aisle, and the mechanics who had that airplane ready before sunrise very likely don’t work for United at all. They work for SkyWest Airlines.

That’s the paradox at the heart of SkyWest. It’s the largest regional airline in North America—big enough to generate nearly $4 billion of trailing twelve-month revenue in 2025—yet it’s almost completely anonymous to the people it serves. SkyWest flies roughly 500 aircraft on behalf of major carriers like United and Delta. As of 2024, it operated a fleet of nearly 500 planes, served 268 destinations across the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, and carried more than 42 million passengers a year. Around 15,000 employees keep the machine running, operating about 2,190 flights per day—roughly split across United Express, Delta Connection, American Eagle, and Alaska.

And still, ask a hundred travelers stepping off those flights who flew them, and almost nobody will say “SkyWest.” They’ll say United, Delta, American, or Alaska—the logos on the tail, the name on the ticket, the loyalty program that took the credit.

SkyWest operates in plain sight but stays invisible by design. That’s not a branding failure. It’s the business model. And it’s a big reason SkyWest has become one of the most consistently profitable operators in an industry famous for chewing up airlines—and investors.

So how does a regional carrier founded in St. George, Utah—a town of about 80,000 people tucked against the red rocks of the Mojave Desert—become the invisible backbone that connects small-town America to the world?

The answer is a masterclass in positioning: choosing the right role in the ecosystem, executing relentlessly, and quietly accumulating leverage by becoming indispensable.

For investors, it’s also a rare case study: a durable business inside a structurally brutal industry. Airlines have destroyed staggering amounts of capital over the decades, yet SkyWest has navigated deregulation, oil shocks, terrorist attacks, recessions, a pandemic, and a pilot shortage—while repeatedly finding ways to survive, adapt, and return capital to shareholders.

To understand why, you have to understand the hidden architecture of American aviation—and where SkyWest fits inside it.

II. The Origins: From Charter Tours to Regional Service (1972–1988)

In the late 1960s, business leaders in St. George, Utah had a very specific kind of problem: they couldn’t count on airplanes to actually show up.

People would book seats to Salt Lake City, drive out to the little airport, and wait. And sometimes… nothing. If the passenger list looked too thin, the carrier would decide the stop wasn’t worth it and continue on to nearby Cedar City instead, leaving would-be travelers staring down the runway, grounded.

It wasn’t just annoying. It was economically suffocating. St. George sat more than 300 miles from Salt Lake City—an all-day trek on winding roads. If you were a lawyer, a developer, or anyone trying to do business in the state capital, unreliable air service didn’t just waste your time. It cut you off from where work happened.

In 1972, local attorney Ralph Atkin decided the town couldn’t wait for someone else to fix it. Using $35,000 he’d earned from legal work, he bought the operating certificate for Dixie Airlines and renamed the company SkyWest. He teamed up with his brother Sid and a small circle of friends, and they scraped together an opening fleet that sounds more like a flying club than an airline: a Piper Seneca and a Cherokee Six—both six-seaters—plus a two-seat Piper Cherokee.

Atkin would go on to serve as CEO and then Chairman, leading the company for roughly two decades. He was St. George through and through, including time as a young man serving a mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in England. That background mattered—not as marketing, but as culture. SkyWest would become known for a kind of quiet discipline: thrift, long-term thinking, and a deep bias toward doing the job right.

SkyWest’s launch had small-town flair. On June 17, it held an open house to celebrate the start of passenger service—complete with “penny-a-pound” rides, parachutists, and aerobatic stunts. Two days later, on June 19, the first scheduled flight took off: Jerry Fackrell flew from St. George to Salt Lake City, stopping in Cedar City along the way. Tickets were $28 from St. George to Salt Lake City, and $25 from Cedar City.

The romance wore off fast.

In its first year, SkyWest carried only 256 passengers. The fleet was modest—small Piper aircraft suited for short hops inside Utah—and the finances were worse. By 1974, SkyWest was deep in debt and openly considering bankruptcy. More than once, the founders sat together and debated whether the sensible move was simply to shut it down.

What kept the company alive—and quietly set its identity—was the decision to prioritize reliability even when it hurt. SkyWest was losing about $300,000 a year, yet the Atkins insisted on rigorous maintenance, on-time departures, and courteous service. In aviation, shortcuts can buy you a little oxygen today and kill you tomorrow. SkyWest chose the slower, sturdier path: build trust first, scale later.

Then the industry changed beneath everyone’s feet.

The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 rewired American aviation. Routes and fares were no longer tightly controlled, and big airlines quickly concentrated around hub airports and shed marginal small-city service. For towns like St. George, that was a crisis—service could disappear overnight. But for a regional carrier willing to feed passengers into hub-and-spoke networks, it was the opening of a lifetime.

SkyWest expanded steadily through the late 1970s and early 1980s. By 1978, it became only the third U.S. commuter airline certified by the Civil Aeronautics Board for scheduled interstate service, which enabled routes to Las Vegas.

By the early 1980s, another SkyWest trait began to emerge: opportunistic expansion, but only when it improved utilization. The company’s flying was seasonal—busy summers, slow winters—and that meant airplanes sitting idle. In 1984, SkyWest took a step that foreshadowed how it would build scale in later decades: it acquired Sun Aire Lines of Palm Springs, California, becoming the eleventh largest regional carrier.

The logic, as Jerry Atkin later explained, was simple: California demand didn’t match their Utah seasonality. Palm Springs was strong when SkyWest was traditionally less busy. Get into that market, and suddenly the same aircraft could work harder year-round.

Two years later, SkyWest went public, completing an early transition from scrappy local carrier to financially disciplined operator. And in 1986, it began codesharing as Western Express, feeding Western Airlines at its Salt Lake City hub and other destinations using Embraer EMB 120 and Fairchild Metroliner turboprops.

Then came a twist that could have derailed a smaller company: Western was acquired by Delta in 1987. Instead of losing its partner, SkyWest effectively got upgraded. It became a Delta Connection carrier, operating codeshare service on Delta’s behalf across destinations in Arizona, California, Colorado, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming.

That relationship changed SkyWest’s trajectory. Flying under Delta’s name gave SkyWest demand, distribution, and credibility—Delta’s marketing, reservations, and passenger traffic—without SkyWest giving up control of its own operation. It was an early version of the model SkyWest would eventually perfect: be invisible to the passenger, indispensable to the major airline.

By the late 1980s, the company’s long-term strategy was coming into focus. SkyWest would win not by being the loudest brand, but by being the most reliable operator: operational excellence in service of major-airline partnerships, disciplined financial management, and patient, practical expansion. And it would do it from St. George—far from the industry’s flashy centers—keeping overhead low and building a workforce known more for consistency than swagger.

III. The Capacity Purchase Model: Inventing a New Business

If you want to understand why SkyWest has endured—and why it looks so different from a typical airline—you have to understand the mechanism that quietly rewired regional aviation: the Capacity Purchase Agreement, or CPA.

A CPA is the deal behind the deal when you board a flight branded United Express, Delta Connection, American Eagle, or Alaska. The major airline controls the things passengers see and feel: the schedule, the routes, the fares, the marketing, the loyalty program, the ticket sale. SkyWest, meanwhile, runs the operation: it provides the aircraft and crews, maintains the planes, and flies the trips.

Here’s the key: under a CPA, SkyWest gets paid primarily for producing flying, not for selling seats. The major airline pays SkyWest fixed fees tied to activity—things like departures and block hours—plus reimbursement for certain operating costs. That single design choice shifts SkyWest’s biggest risk away from demand, pricing, and fuel volatility, and onto something it can actually control: operational performance.

That risk shift matters because traditional airline economics are brutal. A normal airline has to predict demand months in advance, price tickets in a way that fills the plane without giving away revenue, manage fuel exposure, and hope a recession, war, or virus doesn’t blow up the entire plan. When the forecast is wrong, the losses can pile up fast.

CPAs flip the equation. As of 2024, roughly 87% of SkyWest’s flying operated under CPAs. In that structure, SkyWest commits to deliver a certain amount of capacity—seats and block hours across a set number of aircraft—at pre-agreed rates and standards. The major carrier takes on the job of filling those seats and carries the revenue risk if demand softens. When travel demand spikes, the major carrier enjoys the upside. SkyWest still gets paid to fly what it was contracted to fly.

SkyWest does have some flying outside the CPA world. The remaining portion has historically been under a pro-rate arrangement, where SkyWest takes on more of the traditional airline role: it assumes costs, sets fares, keeps revenue from non-connecting passengers, and splits revenue from connecting itineraries on a pro-rated basis with a partner. That’s closer to “classic airline” risk—and it’s a smaller slice of the business.

One of the most important consequences of CPAs is what they do to the two biggest sources of airline chaos: revenue swings and fuel. Fuel can be a massive share of operating costs, and its price can move violently. Under CPAs, major airline partners typically purchase fuel directly for the flying being performed, or reimburse SkyWest for fuel it incurs. The point isn’t that fuel stops being expensive. It’s that SkyWest isn’t betting the company on guessing where fuel prices go next.

In that sense, SkyWest starts to look less like an airline you’d compare to other airlines—and more like a utility. The company invests in expensive, long-lived assets, then earns relatively predictable returns by delivering a service at contracted rates. It’s not a perfect comparison, but it’s closer than the usual mental model of “airline = wild earnings.”

The stability comes with a trade-off: SkyWest gives up the thrill of airline upside. It doesn’t get the windfall from peak-season pricing, and it doesn’t get to celebrate when fuel prices collapse. But for a company built in St. George—shaped by a culture that prizes prudence and stewardship—that bargain fit. SkyWest chose compounding over swinging for the fences.

The contracts themselves reinforce that stability. CPAs are typically long-term—often five to eight years, and sometimes longer—giving SkyWest the ability to finance aircraft and plan staffing against a committed revenue stream. It’s the same basic logic infrastructure businesses use: make big, capital-intensive bets only when you have long-duration demand to match.

So why would the major airlines agree to this? Because CPAs solve two problems at once.

First, labor economics. Major-airline pilots are paid far more than regional pilots, and mainline labor agreements have long made it expensive to operate small jets on short routes with mainline crews. Outsourcing that flying lets majors maintain service to smaller markets without turning every short hop into a money-loser.

Second, brand protection. By keeping the flights under the major’s banner—paint on the tail, the same reservation system, the same loyalty program—the major airline preserves a consistent customer experience without needing to run two very different operating models inside one company.

For SkyWest, the model created a virtuous cycle. If the job is to deliver reliable flying, then reliability becomes the product. SkyWest could pour its energy into completion factor, on-time performance, and maintenance execution—things its partners notice immediately and reward over time. And when SkyWest performs, the relationship deepens: more flying, more aircraft, more scale, and more reasons for majors to stick with the partner that makes their network actually work.

That’s why operational metrics aren’t trivia at SkyWest; they’re the business. In the second quarter of 2025, SkyWest reported an adjusted completion rate of 99.9%. In an industry where cancellations cascade and reputations are fragile, that kind of performance isn’t just impressive—it’s leverage.

IV. Building Scale: Acquisitions and Multi-Carrier Strategy (1985–2008)

The CPA model gave SkyWest stability. But management knew stability wasn’t the same thing as advantage. In regional aviation, advantage comes from scale: a bigger fleet gives you more leverage with manufacturers, spreads fixed costs across more flying, and—most importantly—lets you serve multiple major airlines at the same time without betting the company on any single partner’s strategy.

That multi-carrier approach started to crystallize in the late 1990s. In 1997, SkyWest began flying as United Express in addition to Delta Connection, operating out of United hubs like San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Denver. The aircraft were the practical tools of the era: Embraer EMB 120 turboprops and Bombardier CRJ200 regional jets. By the end of the decade, SkyWest had become United’s largest United Express operator.

This was more than a new paint scheme. It was a positioning move.

Serving both United and Delta—direct competitors—turned SkyWest into something like Switzerland in airline wars. If one major airline tried to squeeze them too hard or force exclusivity, it risked pushing SkyWest closer to the other. And operationally, diversification meant resilience: when one partner cut capacity, SkyWest had a chance to shift resources and keep the machine utilized.

Then came the deal that changed the company’s footprint overnight.

On August 15, 2005, Delta sold Atlantic Southeast Airlines to the newly incorporated SkyWest, Inc., for $425 million in cash. The acquisition closed on September 8, 2005. ASA was a powerhouse Delta Connection operator based in Atlanta, flying a large fleet of Bombardier CRJ regional jets. For SkyWest, it was scale—but it was also geography. Overnight, the Utah carrier gained deep access to the Eastern U.S., a region where it previously had limited presence. It also gained additional crew bases and maintenance infrastructure, making the overall enterprise more redundant and more durable.

The fleet implications mattered, too. ASA had started introducing larger regional jets before the acquisition—receiving its first 70-seat CRJ700s in 2002, after years of operating 50-seat CRJ200s. After SkyWest acquired ASA, the company made the decision to close ASA’s Salt Lake City hub and shift 12 of ASA’s CRJ700s to SkyWest Airlines—though only four of those aircraft ultimately moved between operating certificates. SkyWest Airlines also took delivery of the remainder of ASA’s regional jet orders: five additional CRJ700s and 17 CRJ900s.

Scale, once achieved, has a way of pulling more scale toward it. And SkyWest kept going.

In 2010, SkyWest announced plans to acquire ExpressJet in a deal reported to be worth $133 million, aligning two of the biggest commuter operations tied to United and Continental—right as those two majors were in the process of merging. The deal closed on November 12, 2010. ASA and ExpressJet integrated and received a single operating certificate on December 31, 2011, with the combined airline taking the ExpressJet name.

At the time, ExpressJet flew 206 Embraer regional jets for Continental, 32 for United, and six in its charter unit. ASA flew 160 Bombardier CRJs as a Delta Connection and United Express carrier. Add SkyWest Airlines’ 292 airplanes, and the combined fleet reached 696 aircraft—by far the largest in the regional industry.

Of course, this kind of growth comes with real risk. Airline integrations are famously brutal: pilot seniority fights, maintenance standardization, incompatible processes, and cultural friction. SkyWest’s approach was characteristically conservative. Rather than force everything into one mold on day one, it let acquired carriers retain separate certificates and identities while gradually integrating the back office and coordinating fleet planning.

Running alongside all of this was a quieter, longer-term bet: the fleet itself. SkyWest was the first U.S. airline to order the Bombardier-built Canadair Regional Jet, placing orders for 10 aircraft that wouldn’t arrive until 1993. It was an early commitment to jet-powered regional flying—moving ahead of competitors that were still heavily dependent on turboprops—and it helped set the foundation for the CRJ and, later, E175 fleets that would become SkyWest’s workhorses.

By the late 2000s, SkyWest had built something rare in aviation: the largest independent regional airline in North America, flying for multiple major carriers at once, with enough scale to negotiate rather than just accept terms. The company that once carried 256 passengers in a year now carried tens of millions—yet, to almost every one of them, it was still invisible.

V. The Great Recession and Industry Consolidation (2008–2013)

The 2008 financial crisis didn’t just rattle airlines. It stress-tested the entire logic of the business.

Fuel surged to historic highs and then whipsawed downward as demand fell off a cliff. Credit markets seized up, turning aircraft financing from routine paperwork into a near-impossibility. Corporate travel budgets got slashed, and with them went the high-margin tickets that quietly subsidize everything else in the system. Mainline carriers bled cash.

Regional airlines lived in a strange in-between. The CPA model softened the direct hit—major carriers still owed fixed fees for flying that actually operated, whether planes were full or half-empty. But regionals weren’t truly independent. They were tied, financially and operationally, to the health of their partners. If a major airline ended up in bankruptcy court, a regional contract could be rewritten, rejected, or squeezed under court supervision. CPAs reduced demand risk. They didn’t eliminate counterparty risk.

As the downturn dragged on, the weak didn’t just stumble—they vanished. Independence Air, which had tried to go it alone as a low-cost airline instead of living under CPAs, was gone by 2006. Skybus failed in 2008. Aloha Airlines disappeared. Frontier’s Lynx Aviation shut down. Smaller operators were either absorbed or simply extinguished. The regional industry didn’t just shrink; it consolidated, brutally.

For SkyWest, this period reinforced why its model worked. Its revenue was primarily tied to fixed-fee flying for major partners—meaning passenger load factors and ticket prices weren’t what determined whether SkyWest got paid. When the majors pulled down schedules, SkyWest’s revenue still fell because there were fewer flights to operate. But it wasn’t exposed to the same existential spiral that hits airlines when both demand and pricing collapse at once.

At the same time, the major carriers themselves were reshuffling the chessboard. Delta merged with Northwest in 2008. United merged with Continental in 2010. American entered bankruptcy in 2011. Each deal and restructuring brought a familiar kind of fear to regional partners: Would the new, bigger airline honor existing agreements? Would it consolidate vendors and cut you out? But those same consolidations also increased the value of the partners that could be trusted to execute. Bigger networks meant more complexity, more connections to protect, and less tolerance for missed flights. Reliability wasn’t just nice to have—it was strategy. And SkyWest’s track record made it the kind of operator majors leaned on when they needed the machine to keep running.

This is where SkyWest’s conservative DNA showed up as a competitive weapon. While others had piled on debt in the good years, SkyWest had kept liquidity healthy and leverage manageable. That meant no desperate, dilutive fundraising in the middle of a crisis—and the flexibility to move when weaker competitors couldn’t.

The investor takeaway that crystallized in these years is simple: in aviation, survival is not a baseline expectation. It’s an advantage. SkyWest’s disciplined, sometimes “unexciting” approach—thrift, patience, and operational consistency—looked downright brilliant once the cycle turned and the industry started shedding players.

VI. The Pilot Crisis and Scope Clause Wars (2010–2018)

If the CPA was the invention that made modern regionals viable, pilot economics was the force that nearly broke them.

To understand why regional flying tightened up so dramatically in the 2010s—and why SkyWest’s leverage looks different today—you have to hold two ideas in your head at the same time: the 1,500-hour rule and scope clauses. One strangled the supply of new pilots. The other capped the size of the jets regionals could fly to pay for them.

It starts with a tragedy.

On Feb. 12, 2009, Colgan Air Flight 3407—operating as Continental Connection—crashed into a house on approach to Buffalo Niagara International Airport. All 49 people on board were killed, along with one person on the ground. The NTSB later concluded the pilots failed to respond properly to stall warnings.

The public reaction was immediate, and Washington responded with force. In 2010, Congress passed the Airline Safety and Federal Aviation Administration Extension Act. Among other changes, it pushed the FAA to raise the minimum flight experience required for airline first officers—from 250 hours to 1,500.

Here’s the cruel irony: both pilots on the Colgan flight already had well over 1,500 hours. The rule didn’t map cleanly to the root cause. But it did reshape the labor market anyway.

The impact showed up quickly. In 2012, there were 140,230 commercial pilots. The following year, that figure fell to 108,206—a drop of nearly 30%. In raw terms, 2013 saw a decline of 32,024 commercial pilots, the same year the FAA implemented the 1,500-hour rule.

For aspiring pilots, the pipeline suddenly got longer and more expensive. Flight training was already costly. Now, after paying for training, a would-be first officer still needed to log well over a thousand additional hours before becoming eligible for an airline cockpit. Many built those hours as flight instructors, often earning around $20,000 to $30,000 a year. Some never made it through the bottleneck. Others did—but arrived with debt, fatigue, and a clear plan: get in, get the hours, and jump to a major carrier as fast as possible.

That dynamic hit regionals especially hard. Before the rule, they could hire directly out of flight schools. After the rule, they were competing for a much smaller pool of eligible candidates—and then watching many of them leave the moment a major called.

And just as labor got more expensive, the aircraft options got boxed in.

Major airlines’ pilot unions weren’t thrilled about outsourcing short-haul flying to lower-paid regional crews, so they negotiated “scope clauses”—contract provisions that limit how much flying can be done by regional affiliates, and in what size aircraft. By 2012, American, Delta, and United had capped regional jets at 76 seats and a maximum takeoff weight of 86,000 pounds.

This mattered because it froze the regional fleet at a size that could only earn so much revenue per flight. Costs—especially pilot costs—were rising. But the economics of the aircraft were capped by contract.

Over time, the scope box got even tighter in practice. New aircraft programs didn’t bail the industry out. The Embraer 175-E2 first flew on Dec. 12, 2019, but it didn’t solve the scope problem. Mitsubishi’s SpaceJet program was suspended in October 2020 and later cancelled in 2023. By then, the Embraer 175 stood out as the only scope-clause-compatible jet still in production for the U.S. market.

For SkyWest, this period was real pain, not just a talking point. Attrition climbed as pilots finally cleared the hours hurdle and left for higher pay and better schedules at the majors. Training costs rose. Scheduling got harder. And the routes that were already fragile—thin demand, long stage lengths, Essential Air Service flying—became tougher to staff consistently.

That strain spilled into the public record. On March 10, SkyWest notified the Department of Transportation that it intended to end scheduled service to 29 cities on or before June 10, with all destinations in the Essential Air Service program, citing the flight crew shortage.

In the moment, it looked like the regional system was unraveling.

But the same forces that created the crisis also created an opening. When pilots are scarce, scale matters: bigger training infrastructure, deeper scheduling benches, more negotiating leverage, and more ways to redeploy aircraft across multiple partners. Competitors without SkyWest’s balance sheet and operational depth struggled even more. As weaker carriers shrank or failed, the majors leaned harder on the operators that could still deliver reliable flying.

And in a CPA world, reliability isn’t just performance—it’s bargaining power.

VII. The Great Reset: Strategic Pivot and Contract Restructuring (2018–2022)

By 2018, regional aviation hit an inflection point. The pilot shortage, once treated like a temporary staffing crunch, had hardened into something structural. Across the country, small cities started losing air service—not because demand vanished, but because the system couldn’t reliably crew the flights. Regional airlines began pulling capacity from marginal markets, including subsidized Essential Air Service routes, just to keep the rest of their networks functioning.

SkyWest put it bluntly in a filing to the Department of Transportation: “Although SkyWest Airlines would prefer to continue providing scheduled air service to these cities, the pilot staffing challenges across the airline industry preclude us from doing so.”

Inside the company, leadership was saying the same thing with less formality and more urgency. On an earnings call, CEO Chip Childs warned the shortage was becoming one of SkyWest’s biggest headaches. SkyWest expected to fly materially fewer block hours in 2022 because of what he called the “pilot imbalance,” and he didn’t see it easing quickly.

For the major airlines, this was the moment the ground shifted. For decades, Delta, United, and American had treated regional flying like a commodity—something you bid out to the lowest-cost operator, then squeeze on renewals. But now regional partners were coming up short, and there weren’t plenty of alternatives waiting in the wings. When the flying matters to your hub connectivity, “cheap” stops being the priority. “Crewed” becomes the priority.

That shift showed up in the contracts. Over 2022 and 2023, SkyWest amended its capacity purchase agreements with major partners, resulting in higher compensation to cover rising labor costs. At the same time, SkyWest raised pay and bonuses across its workforce, including a 35% increase in starting pay for flight attendants in 2023.

SkyWest also tried a more radical pressure-release valve: SkyWest Charter, a Part 135 subsidiary aimed at restoring service to small markets with a different regulatory framework. Part 135 rules allow the company to hire pilots with far fewer hours than Part 121 scheduled airline operations require—down to 250 hours instead of 1,500. The trade-off is real: SkyWest Charter can’t fly aircraft with more than 30 seats, and those flights sit outside the CPA structure that defines most of SkyWest’s core business.

The idea was immediately controversial. The Air Line Pilots Association repeatedly objected, and in a letter to U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, ALPA President Captain Jason Ambrosi argued the strategy would “roll back the clock and skirt the aviation safety rules.”

But the bigger story wasn’t a new subsidiary. It was leverage—earned the hard way.

SkyWest was one of the only large, financially stable regional operators left with true scale. And scale matters when the constraint is pilots. So SkyWest leaned into what the crisis made true: it could not deliver the flying unless the economics changed. The message to partners didn’t need to be shouted. It was obvious in every cancelled frequency and every city that lost service: pay more, or the routes simply won’t get flown.

That reset changed SkyWest’s trajectory. As renegotiated contracts kicked in, unit revenue per block hour moved higher. And fleet strategy snapped into even sharper focus. The Embraer E175—76 seats, comfortably inside scope clause limits—became the workhorse. SkyWest accelerated the shift away from smaller, less profitable aircraft like the CRJ200s and CRJ700s, using the E175 to anchor a regional model that could finally support the new reality of pilot costs.

VIII. COVID-19: Surviving the Unthinkable (2020–2021)

In March 2020, the floor dropped out from under commercial aviation. As COVID-19 spread, air travel effectively shut down—and passenger traffic collapsed by more than 95% almost overnight. Airlines that had looked unstoppable weeks earlier were suddenly fighting to stay alive.

Washington stepped in with an industry-scale lifeline. Through the Payroll Support Program, the U.S. Treasury Department ultimately distributed $59 billion across three rounds—PSP1, PSP2, and PSP3—to keep aviation employees paid. PSP1 came through the CARES Act, PSP2 through the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, and PSP3 through the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

SkyWest took support too. SkyWest, Inc. announced that SkyWest Airlines entered into a Payroll Support Program Agreement with the Treasury Department to receive about $438 million under the CARES Act. Roughly $337 million came as a direct grant, and about $101 million as a ten-year, low-interest, unsecured term loan, delivered in four disbursements. In exchange, SkyWest agreed to issue warrants to the Treasury to purchase about 357,000 shares of SkyWest common stock. The purpose was straightforward: keep paying the wages, salaries, and benefits of thousands of SkyWest employees through a period when flying—almost everywhere—had evaporated.

And once again, SkyWest’s business model mattered. While major airlines watched passenger revenue crater, SkyWest’s CPA structure kept the company from being dragged down by the same demand spiral. SkyWest was paid for operating flights, not for selling seats, and many of its CPAs also included minimum revenue guarantees that helped soften the blow even as block hours fell.

SkyWest also made a strategic choice that would look quietly brilliant in hindsight: it prioritized keeping its pilot ranks intact instead of cutting to the bone. In the moment, that meant carrying cost through the worst downturn in industry history. But when travel began to return in 2021, airlines that had furloughed aggressively discovered they couldn’t simply snap schedules back into place. SkyWest could. That operational readiness translated into faster ramp-up—and a stronger hand in a market where reliable capacity was suddenly scarce.

The pandemic claimed an ironic casualty along the way: ExpressJet. SkyWest had acquired it in 2010, then sold it in 2019. In August 2020, United announced ExpressJet’s operation would wind down, and its last flight flew at the end of September.

For SkyWest, COVID didn’t rewrite the playbook. It validated it. In the end, the survivors weren’t the flashiest or the most optimistic. They were the ones built for endurance—conservative with the balance sheet, relentless about execution, and useful enough to their partners that the system still needed them when everything else stopped.

IX. The Modern Era: Electrification, Consolidation, and the E175 Bet (2021–Present)

Coming out of COVID, SkyWest didn’t just survive. It emerged with something rare in this industry: momentum.

By 2024, the financial picture looked dramatically different than it did a year earlier. SkyWest reported $97 million of net income in Q4 2024, up from $18 million in Q4 2023. For the full year, net income reached $323 million, compared to $34 million in 2023. Revenue rose to $3.53 billion in 2024, up from $2.94 billion the year before.

That surge wasn’t a mystery spike. It was the payoff from the reset we just talked about: CPA contract amendments with better economics, a fleet mix moving toward more profitable aircraft, operating leverage as pilot availability improved, and a regional market that had quietly consolidated into fewer, stronger players.

The centerpiece of SkyWest’s modern strategy is one airplane: the Embraer 175. At the time of writing, SkyWest had more than 570 aircraft in its fleet, including 262 E175s—making it the leading operator of the type worldwide. And that dominance isn’t just a nice trivia fact. In the U.S., the E175 sits in a very specific sweet spot: big enough to make the economics work, but still inside the scope clause box that governs what regional partners are allowed to fly.

In June 2025, SkyWest doubled down in a way that made the bet explicit. The company announced an agreement to purchase and operate 16 new E175s under a multi-year contract for Delta Air Lines. Those jets are expected to replace 11 CRJ900s and five CRJ700s currently flying for Delta, with deliveries beginning in 2027.

SkyWest also locked in the ability to keep building that E175 backbone for years. It secured firm delivery positions for 44 additional E175s from 2028 through 2032, with the intent to take those aircraft if it enters flying agreements with one of its major partners. Alongside that, SkyWest announced firm delivery positions and purchase rights on 50 additional E175 aircraft, giving it meaningful fleet flexibility over the next decade.

By the end of 2026, SkyWest was scheduled to operate 278 E175s in total.

For investors, the strategic point is simple: in the U.S. market, scope clauses are a structural source of demand for this exact category of aircraft—and the Embraer 175 is the only in-production regional jet that fits the major airlines’ scope requirements. If you’re going to be the indispensable supplier of that flying, owning the leading E175 operation is a powerful place to sit.

And SkyWest isn’t only thinking about the next contract cycle. It’s also positioning itself for what might come after the current scope-and-pilot-era equilibrium.

One potential unlock is electrification. Heart Aerospace is developing its hybrid-electric airplane, the ES-30, and aims to achieve type certification by 2028. Heart says the ES-30 could carry up to 30 passengers, with a zero-emission range of 200 kilometers, an extended hybrid range of 400 kilometers for 30 passengers, and up to 800 kilometers with 25 passengers.

The ES-30 has drawn significant interest across the industry, with airlines including Air Canada, United Airlines, and SAS tied to the program, and more than 250 firm orders placed. United—one of SkyWest’s major partners—has invested in Heart Aerospace and placed significant orders.

SkyWest hasn’t publicly announced ES-30 orders of its own. But the strategic fit is obvious: if electric or hybrid-electric aircraft can make short, thin routes economical again, that could reopen the exact kinds of small markets that have been hardest hit by the pilot shortage and regional capacity constraints. For an airline that started by connecting overlooked places—and built a business around being the quiet link in the chain—that’s an intriguing next frontier.

X. The Business Model Deep Dive: How SkyWest Actually Makes Money

If you’re looking at SkyWest like a fundamental investor, the question isn’t “How full were the planes?” It’s “How much flying did SkyWest produce, and what did it get paid for that production?”

Almost all of the answer lives inside the Capacity Purchase Agreement. As of September 30, 2024, CPAs represented about 86.8% of SkyWest’s total flying agreement revenue. In these deals, the major airline does the commercial heavy lifting—schedules, ticketing, pricing, and inventory. SkyWest does the industrial part: it staffs the flights, maintains the aircraft, and operates the trips. And crucially, it gets paid largely based on block hours—essentially, the time the aircraft is operating, including taxi.

That structure shapes how revenue shows up. SkyWest recognizes revenue as it produces flying. There are fixed fees tied to things like departures and aircraft under contract, plus separate aircraft-related payments intended to cover the cost of owning the planes. Some contracts also include incentive payments for operational performance—on-time operation and completion rates—so the thing SkyWest prides itself on operationally is also the thing that earns it incremental dollars financially.

SkyWest describes the model plainly: under these fixed-fee agreements, major airline partners pay fixed rates primarily based on completed flights, flight time, and the number of aircraft under contract. Partners also compensate SkyWest monthly for aircraft ownership costs. The details vary by agreement, but the intent is consistent: cover either principal and interest debt service, or depreciation and interest expense, while the aircraft is under contract.

Then there’s the unglamorous engine of the whole operation: maintenance.

SkyWest has substantial in-house maintenance, repair, and overhaul capability. That’s not just a cost center—it’s a strategic advantage. When you can do more work yourself, you’re less dependent on third parties, you can turn aircraft faster, and you can standardize processes at a scale smaller competitors can’t replicate. In a business where a single out-of-service jet can ripple through a network, speed and control matter.

Management has said it expects maintenance expense to be around $700 million this year and about $800 million next year—roughly $200 million per quarter. The takeaway isn’t the precision of the number. It’s the reality that maintenance is one of SkyWest’s biggest line items, and one of the places where execution quality shows up directly in margins.

The other big lever is utilization. Aircraft are expensive assets that depreciate whether they fly or sit. The job is to keep them working. SkyWest’s scale helps it schedule crews efficiently and position aircraft to maximize block hours per plane. And its multi-carrier strategy adds flexibility: if demand shifts in one partner’s network, SkyWest has more options to redeploy assets into another partner’s flying and keep utilization up.

Putting it together—contract structure, maintenance control, and high utilization—creates the cash-generation profile investors care about: a business that’s less exposed to ticket prices and more exposed to operational execution.

Looking forward, SkyWest has said it expects 2025 GAAP EPS to be around $9 per share. It also expects block hours to approach 2019 levels—another way of saying the operation is getting back to a pre-pandemic cadence, with the earnings power of the post-reset contract economics.

XI. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: Very Low

On paper, you can imagine a scrappy new airline showing up and undercutting the incumbents. In practice, starting a Part 121 regional in the U.S. is an obstacle course: FAA certification, significant capital to acquire and finance aircraft, training infrastructure, and—most critically—winning contracts from major carriers that have little appetite for betting their networks on an unproven operator.

Part 135 is sometimes framed as a workaround because it allows hiring pilots with as little as 250 hours. But it comes with real constraints: SkyWest Charter can’t operate aircraft with more than 30 seats, and those flights sit outside the CPA ecosystem that defines most of regional aviation economics. The results speak for themselves: no new Part 121 regional airline has successfully entered the U.S. market in more than a decade.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate to High

Suppliers have leverage because the choices are limited. On the aircraft side, the bottleneck is especially stark: the Embraer 175 is the only in-production regional jet that fits U.S. scope requirements. That effectively puts Embraer in a monopoly-like position for the one airplane category the majors still want.

Labor is the other supplier that matters. The 1,500-hour rule tightened pilot supply, and the majors’ post-COVID hiring pulled talent upward, giving pilots outsized bargaining power. Fuel, meanwhile, is less of a supplier weapon for SkyWest than it would be for a traditional airline, because under most CPAs fuel costs are largely passed through to the major carrier partner.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High but Declining

SkyWest’s customers aren’t passengers. They’re United, Delta, American, and Alaska—huge, sophisticated buyers that historically dictated terms and treated regional flying as a commodity service.

But consolidation and the pilot shortage changed the balance. In an interview with TPG last month, Black put it bluntly: “I think no matter what we do right now, more communities are going to lose air service. The time to fix the pilot shortage was four or five years ago. At this point, we are trying to correct a problem.” In other words: when the scarce resource is crews and reliable lift, the buyer can’t simply shop for the cheapest provider.

SkyWest’s “Switzerland” strategy helps here, too. Flying for multiple majors reduces dependence on any single buyer and makes it harder for any one partner to squeeze terms without consequences.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium

There are substitutes, but none are clean.

Majors could bring more regional flying in-house, but scope clauses negotiated with mainline pilot unions make that economically unattractive for much of the network. Low-cost carriers like Frontier and Spirit can bypass hubs and steal some demand, but they don’t solve the “small city to hub” connectivity problem that regionals exist to serve. High-speed rail remains negligible in the U.S., and for many small communities there simply isn’t a practical alternative to air service.

Competitive Rivalry: Low and Decreasing

Regional aviation used to be a knife fight. It’s increasingly a short bench of survivors.

SkyWest is the largest regional airline in North America by fleet size, passenger volume, and destinations served. Most remaining competitors are either captive (like Envoy) or operating under financial strain and capacity constraints (like Mesa). As the pool narrows, competition shifts from price to execution—who can crew the flying, keep aircraft in service, and protect the major’s network with high completion rates.

Hamilton's 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: ★★★★★

SkyWest’s fleet of more than 500 aircraft creates real cost advantages. Training, maintenance facilities, and parts inventory are expensive fixed investments—and SkyWest can spread them across more block hours than anyone else in the independent regional world. That scale also translates into negotiating leverage with Embraer, lessors, and the supplier ecosystem.

Network Effects: ★☆☆☆☆

There aren’t meaningful network effects in the classic “more users attract more users” sense. The closest analogue is that operating across multiple hubs gives SkyWest flexibility in how it positions aircraft and crews. It’s valuable, but it’s better thought of as operational efficiency than a true network effect.

Counter-Positioning: ★★☆☆☆

The CPA-based regional operator is, by nature, counter-positioned against the major airlines. A legacy carrier can’t easily replicate SkyWest’s cost structure and operating focus without running into its own union dynamics, pay scales, and internal complexity. That said, this advantage applies broadly to the regional model and isn’t exclusively SkyWest’s invention.

Switching Costs: ★★★★☆

Changing regional partners isn’t like swapping vendors. It’s a full operational transplant: gates and ground handling, IT and reservations integration, maintenance coordination, and the costly work of training and certifying pilots on specific aircraft under specific procedures. On top of all that, there’s the hardest-to-measure cost: trust. Years of reliable performance is an asset that doesn’t transfer cleanly to a new partner.

Branding: ★☆☆☆☆

To consumers, SkyWest is almost invisible. Passengers buy United, Delta, American, or Alaska.

But in B2B terms, SkyWest’s brand is very real: it’s the reputation for operational reliability—showing up, launching flights, and not breaking the network. That “brand” doesn’t live in ads. It lives in completion rates and the quiet confidence of a major airline scheduling department.

Cornered Resource: ★★★★☆

Operating certificates, airport access, a trained pilot pipeline, an experienced maintenance workforce, and long-standing relationships with major carriers add up to a set of assets that are difficult to reproduce quickly. Competitors can buy aircraft. They can’t buy decades of institutional infrastructure overnight.

Process Power: ★★★★★

SkyWest’s operational performance is the product. When the company delivered an adjusted flight completion rate of 99.9% in Q2 2025, that wasn’t a quarter of good luck—it was the output of systems, procedures, and culture built over decades. In a business where one disrupted morning can cascade through an entire network, process power is not just a strength. It’s the moat.

Overall Assessment: SkyWest’s moat derives primarily from Scale Economies, Process Power, Switching Costs, and Cornered Resources. The pilot crisis and consolidation didn’t just shrink the industry—they removed would-be challengers and made the surviving operators, especially the most reliable one, more essential than ever.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

The bull case for SkyWest is that it’s becoming the last scaled, independent regional operator standing in a market that has quietly consolidated. With fewer viable competitors and no easy path for new entrants, SkyWest has more leverage at the negotiating table than regionals historically ever had. And in a CPA world, that leverage shows up in one place: better rates when contracts get renewed or amended.

You can see the results in the numbers. In the third quarter of 2025, SkyWest reported net income of $116 million, or $2.81 per diluted share—well ahead of the prior year. It also kept working down the balance sheet: total debt at the end of Q3 2025 was $2.4 billion, down from $2.7 billion at 2024 year-end.

The fleet transition is the other long runway. The Embraer E175 has become the economic sweet spot for U.S. regional flying, and as SkyWest continues replacing older, less profitable aircraft like the CRJ200, margins should benefit. Management expected 2025 GAAP EPS to come in the mid-$10 per share range, supported by a projected 12–13% increase in block hour production for the year. Longer term, SkyWest is investing toward a fleet of nearly 300 E175s by 2028.

Meanwhile, major-carrier dependence keeps deepening. Even if the pilot shortage has eased from its peak, it hasn’t gone away as a structural constraint, and the regional pilot pipeline doesn’t expand overnight. SkyWest’s cadet programs and training infrastructure become advantages here—not just for hiring, but for maintaining the steady flow of crews required to deliver consistent completion rates.

And then there’s the call option: electric aviation. If Heart Aerospace succeeds in delivering a commercially viable ES-30 by the end of the decade, SkyWest’s relationships, operating know-how, and infrastructure could position it to restore service in smaller markets where conventional economics no longer work—potentially at much lower unit costs.

Bear Case:

The bear case starts with the uncomfortable truth about the model: SkyWest is a service provider. Fixed-fee CPAs bring stability, but they also cap upside. When travel demand surges, majors can raise fares. SkyWest mostly gets paid for the flying it performs. That means shareholder returns depend on producing more block hours and steadily improving contract terms, not on sudden, dramatic margin expansion.

There’s also a potential structural shift in demand. If point-to-point low-cost carriers keep pulling travelers away from hub-and-spoke connections, that chips at the very architecture that regional airlines exist to serve. Fewer connections through hubs can mean less need for the short feeder flights SkyWest operates.

Scope clauses are another overhang. Today, scope limits protect the regional jet category by forcing majors to keep certain flying outsourced and capped at specific aircraft sizes. If those rules ever loosened—on seats, weight, or both—mainline carriers could shift flying in-house or simply upgauge aircraft in ways that shrink the regional market. Unions have consistently resisted changes, but labor dynamics and contract cycles can evolve.

The pilot situation could also swing the wrong way. With mandatory retirement at age 65 steadily pulling experienced pilots out of the majors, the majors will keep recruiting aggressively—which often means pulling from regionals. If the training pipeline can’t keep pace, SkyWest’s growth could stall, and even maintaining existing capacity could get harder.

Finally, electric aviation cuts both ways. The technology is unproven at commercial scale, and it could demand meaningful capital. Delays, certification hurdles, or underwhelming economics could leave early adopters exposed.

What to Watch:

Key Performance Indicators:

-

Block Hour Production Growth — The clearest indicator of how much flying SkyWest is actually producing. Watching block hours year-over-year shows whether the business is expanding, stabilizing, or constrained.

-

Contract Revenue Per Block Hour — A clean way to track pricing power under CPAs. If revenue per block hour rises, it suggests SkyWest is converting scarcity and reliability into better economics.

Together, they answer the only two questions that really matter in the CPA world: is SkyWest flying more, and is it getting paid more for that flying?

XIII. Epilogue: The Invisible Backbone of American Aviation

Step back, and SkyWest’s story starts to look like something bigger than an airline story.

It begins with a simple, almost small-town problem: a St. George attorney got tired of flights that didn’t reliably show up, so he decided to build the reliability himself. Decades later, that same impulse had compounded into a multibillion-dollar enterprise—one that connected roughly 265 destinations across North America, carried tens of millions of passengers a year, and did it all without most of those passengers ever knowing its name.

That’s the paradox. In a world where business advice is basically a hymn to branding—build a consumer identity, differentiate, win mindshare—SkyWest built its advantage by opting out. It didn’t try to become a household name. It became infrastructure.

Instead of competing head-to-head with United and Delta, it served them. Instead of spending to be noticed, it invested to be trusted. And instead of chasing the upside of ticket prices and consumer demand, it chose a model where it could win by doing what it could control: operate reliably, every day, at scale.

For founders and investors, SkyWest is proof that boring can be beautiful. No splashy consumer campaigns. No dramatic reinventions. No grandstanding. Just relentless execution—flight after flight, year after year—until “operational excellence” stopped being a slogan and became an institutional capability competitors couldn’t copy quickly.

The lessons stack on top of each other. Neutrality as strength: flying for multiple majors without picking sides. Reliability as moat: performance that creates real switching costs. Conservative finance as an advantage: the balance sheet discipline to survive cycles that wiped out others. And patient accumulation of scale: not growth for growth’s sake, but scale that makes you harder to replace.

Looking ahead, the same forces that nearly broke regional aviation have also strengthened SkyWest’s hand. The pilot shortage reset the economics. The shift toward the E175 gave the business a clear, profitable workhorse. And electric aircraft remain speculative, but interesting—because if that technology ever makes thin routes economical again, it would reopen exactly the kinds of markets SkyWest was built to serve.

Most importantly, the underlying architecture still seems durable. Hub-and-spoke networks don’t work without feeders. Major carriers can’t economically send big narrowbodies to places like Casper or Cedar City and call it a day. They need partners who can operate the smaller flights that hold the network together. SkyWest has spent five decades proving it can do that job better than anyone else.

Sometimes the best businesses are the ones passengers never think about. They quietly move millions of people, keep small communities connected to the national economy, employ thousands, and generate billions in revenue—while remaining almost invisible. For SkyWest, that invisibility isn’t a weakness.

It’s the strategy.

XIV. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—into the numbers, the contracts, and the structural forces that shaped regional aviation—these are great places to start:

-

SkyWest Annual Reports (2008, 2013, 2018, 2020, 2024) — The shareholder letters are the closest thing SkyWest has to a narrative: how management thought about cycles, contracts, and capital allocation in real time.

-

DOT Data: T-100 Segment Database — The raw feed for route-by-route flying: who’s operating, where, and how capacity shifts over time.

-

Regional Airline Association Publications — A useful window into how the industry talks about the pilot pipeline, scope constraints, and small-community service.

-

Heart Aerospace Partnership Announcements — The best source for what’s actually been announced on the ES-30 program, including timelines and partners.

-

Embraer Investor Presentations — Helpful context on the E175 backlog and how production capacity can become a bottleneck for U.S. regional growth.

-

FAA Pilot Certification Statistics — A data-driven way to track pilot supply, and the long tail effects of the 1,500-hour rule.

-

Major Carrier Pilot Union Contracts — Where scope clauses live in black and white, shaping what regional airlines can fly and how big they’re allowed to get.

-

Essential Air Service Program Data — A clear look at which small markets are subsidized, how much support they receive, and why those routes are so often first to get cut.

-

SkyWest Quarterly Earnings Transcripts — The most direct read on contract renegotiations, fleet moves, and what’s changing quarter to quarter.

-

Industry Academic Research — MIT Airline Industry Research and Brookings work are strong for understanding the post-deregulation system SkyWest operates inside.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music