Shake Shack: From Hot Dog Cart to Modern American Restaurant Empire

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

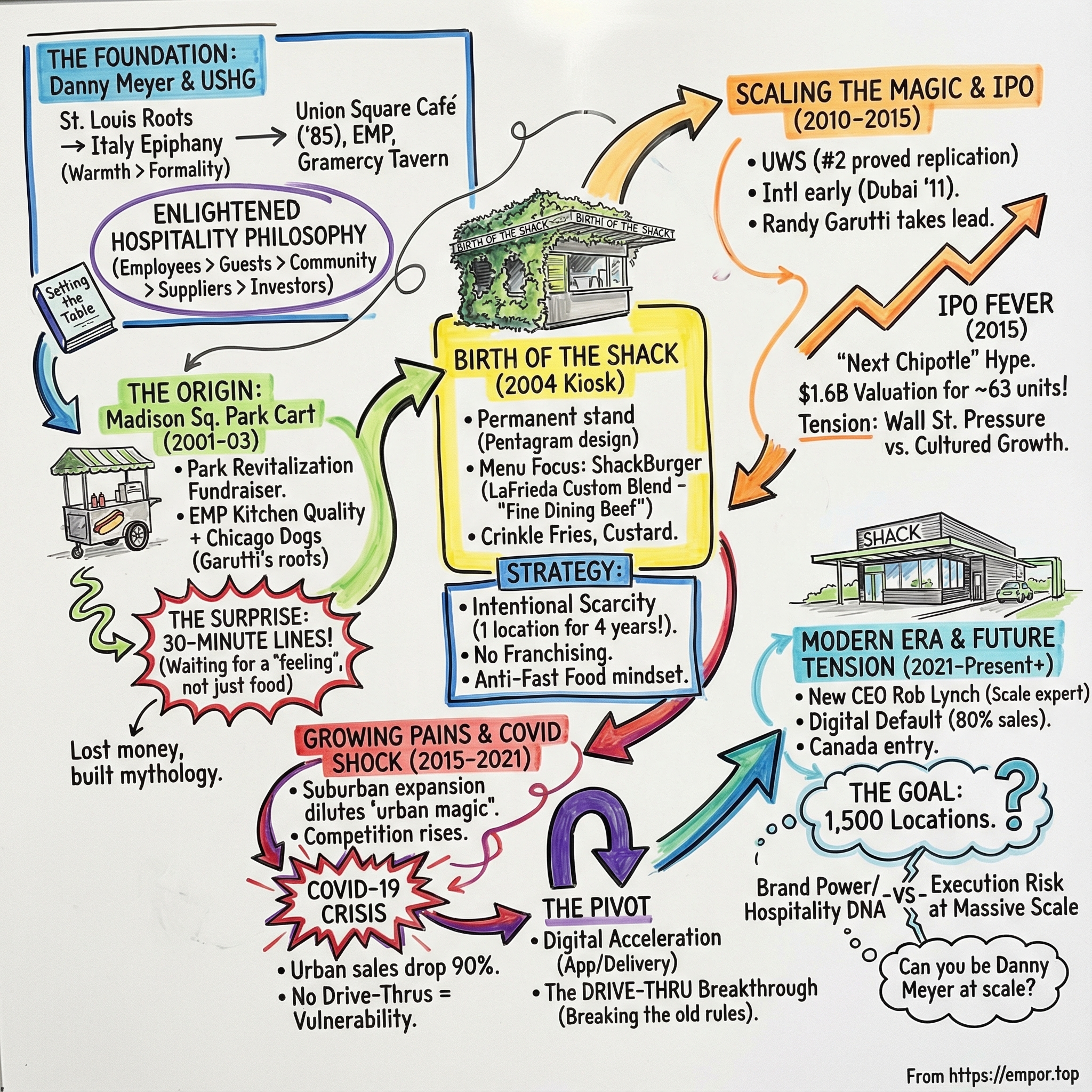

Picture a New York City summer in 2001. Madison Square Park is still a little worn around the edges—an urban oasis that needs saving. And into that setting comes an idea that sounds almost too small to matter: a hot dog cart, run as a fundraiser, with food coming out of the kitchen of Eleven Madison Park, one of Manhattan’s most celebrated fine-dining restaurants.

On paper, it’s a ridiculous contrast. A high-end kitchen sending Vienna beef dogs to construction workers, office crowds, and families on a park bench. But in real life, something strange happens: people line up. They don’t just grab a hot dog and move on—they wait. And within a few years, that “simple” cart becomes the spark for something far bigger: Shake Shack, now a publicly traded company with roughly $1.3 billion in annual revenue, 371 locations in the U.S., and more than 200 more across 25 countries.

Today, Shake Shack trades under the ticker SHAK. The stock sits around $85, giving it a market cap of about $3.6 billion. The company has logged sixteen straight quarters of revenue growth, and management is talking about a future with at least 1,500 company-operated locations—more than quadruple what it told investors to expect at the IPO. After two decades of growth, hype, hard lessons, and reinvention, Shake Shack is at one of those rare moments where the next chapter could define the whole legacy.

So here’s the question that matters: how did a philanthropic side project in a Manhattan park turn into a premium fast-casual chain that people compare to In-N-Out, and that keeps forcing the burger business to rethink what customers will pay for?

The answer lives at the intersection of a few big ideas: Danny Meyer’s philosophy of Enlightened Hospitality, the counterintuitive power of intentional scarcity, the brand mythology that forms when you refuse to grow too fast, and what Meyer later called “fine-casual”—a category that didn’t really exist until he helped will it into being.

Because Shake Shack wasn’t born in a test kitchen built to optimize speed and margins. It was born out of fine dining—built around the same mindset and standards that powered Union Square Cafe and Eleven Madison Park. Premium ingredients. Real hospitality. A tight menu. And an almost stubborn belief that you could serve something special quickly, without turning it into fast food.

That DNA is why people stood in thirty-minute lines for a burger. And it’s also the tension at the heart of this whole story—because scaling that kind of experience is brutally hard. The question now isn’t just whether Shake Shack can get to 1,500 locations. It’s whether it can get there and still feel like Shake Shack.

This is a story about a brand that made waiting part of the appeal, about the collision between hospitality culture and Wall Street’s demand for growth, and about what happens when a founder’s vision meets the physics of scale.

II. Danny Meyer & Union Square Hospitality Group: The Foundation

Before there was a ShackBurger. Before the line curled through Madison Square Park like it was waiting for concert tickets. There was Danny Meyer—27 years old, from St. Louis—making an improbable bet on a then-overlooked corner of Manhattan.

Meyer was born on March 14, 1958, and raised in a Reform Jewish family in St. Louis, Missouri. Food and travel weren’t occasional treats in the Meyer household; they were the family language. His mother, Roxanne Harris, and his father, Morton L. Meyer, built a life around hospitality, and his father’s travel business—designing custom European trips—put young Danny in close contact with the idea that experiences could be crafted. Add in a family tree that included Chicago businessman and philanthropist Irving B. Harris, and you get a foundation that was less about restaurants and more about hosting—how to make people feel something.

At first, though, Danny’s path looked like it might head somewhere else entirely. He went to Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, joined Alpha Delta Phi, and graduated in 1980 with a political science degree. He even worked in Chicago as the Cook County field director for John Anderson’s 1980 independent presidential campaign.

But Rome kept pulling at him. During college, he worked for his father as a tour guide there, and later returned to study international politics. And it was in Italy—less in a classroom, more at tables—that the future clicked into place. Meyer fell hard for the Italian approach to dining: warmth over formality, community over transaction, the sense that a meal wasn’t a purchase so much as a shared event.

He has been candid about what came next: when he opened his first restaurant, he didn’t really know what he was doing. What he did have was an unusual willingness to learn in public—adjusting fast, obsessing over the details, and getting better every day.

In 1985, at 27, he opened Union Square Cafe. It wasn’t just a new restaurant; it was a new kind of New York restaurant. It took cues from the Union Square Greenmarket, leaned into great local ingredients, and paired them with a dining room that felt contemporary, welcoming, and alive. People didn’t just come to eat—they came because they liked how the place made them feel.

That feeling became the real product. Union Square Hospitality Group—USHG—started stacking wins in a way that’s rare in any city, let alone New York. In the Zagat guide, USHG restaurants consistently ranked among the most popular in the city, and Union Square Cafe itself held the #1 spot nine different times. That kind of repeat performance doesn’t happen because you had one good chef or one great year. It happens when you’ve built a system—when you’ve figured out how to deliver an experience with consistency.

Meyer eventually put a name to that system: Enlightened Hospitality. The ordering was the point, and it was controversial in an industry that often treated labor as a cost to minimize. His hierarchy was: employees first, then guests, then community, then suppliers, and finally investors—in that order. The idea was almost disarmingly simple: take great care of your team, and they’ll take great care of guests. Happy guests come back, and the business gets healthier for everyone else downstream.

As USHG grew, it did so deliberately. Gramercy Tavern opened in 1994 in a historic landmark building, bringing refined American dining into a space that still felt human and warm. Later came Eleven Madison Park and The Modern—tablecloth restaurants that played at the highest level of the industry. Over time, those restaurants accumulated the kinds of signals that the culinary world uses to mark excellence: Michelin stars, James Beard Awards, and major personal recognition for Meyer, including Outstanding Restaurateur in 2005 and induction into Who’s Who of Food and Beverage in America in 1996. USHG has won 28 James Beard Foundation Awards.

But the bigger move wasn’t a new restaurant. It was turning a craft into a philosophy others could apply.

In 2006, Meyer published Setting the Table. The book—eventually a New York Times bestseller—did something rare: it translated restaurant hospitality into a set of principles that worked for almost any service business. It made Meyer more than a celebrated restaurateur; it made him a teacher of how hospitality can be engineered into culture.

His influence expanded beyond food media, too. Over the years he received major honors including the 2017 Julia Child Award, being named to the 2015 TIME 100 list, the 2012 Aspen Institute Preston Robert Tisch Award in Civic Leadership, the 2011 NYU Lewis Rudin Award for Exemplary Service to New York City, and the 2000 IFMA Gold Plate Award.

So why does this whole Danny Meyer résumé matter for a burger chain?

Because Shake Shack didn’t come out of nowhere. The “hot dog cart in the park” story is true, but it’s not the full story. The cart was the distillation of everything Meyer had been building for two decades: the culture, the operating discipline, the supplier standards, and the belief that hospitality could be a competitive advantage—not a nice-to-have.

Even the earliest Shake Shack food traced back to USHG’s fine-dining infrastructure. The first recipes were developed in Eleven Madison Park’s kitchens. And the hiring philosophy carried over, too. As Meyer put it: “We’re hiring people almost exclusively based on their hospitality skills. We hire people who don’t come yet with the technical skills but are willing to learn. They are already someone who likes smiling and making people feel good.”

By 2001, Danny Meyer wasn’t just a restaurateur with a string of hits. He was a system builder—someone who’d already proved that a culture of hospitality could scale across concepts without losing its soul.

And that’s exactly the capability the Madison Square Park “side project” was about to test.

III. The Hot Dog Cart Origins & Madison Square Park (2001–2004)

Madison Square Park in 2001 wasn’t the glossy postcard version you see today. It had drifted into neglect, and the newly formed Madison Square Park Conservancy was hunting for ideas—any ideas—that could raise money and attention for a full revival.

One of its first big swings was an art installation in the park called I ♥ Taxi. Danny Meyer and his team at Union Square Hospitality Group got involved, and his Director of Operations, Randy Garutti, helped set up a hot dog cart as part of the effort. The food wasn’t coming from some generic commissary kitchen, either. It was run out of Eleven Madison Park.

That’s the part that makes the origin story feel almost absurd: one of New York’s top fine-dining operations, cooking for a cart in a battered public park. And it wasn’t pitched as the start of a business. It was charity work—something fun for the summer, a way to help the neighborhood and the Conservancy.

But Meyer couldn’t help being Meyer about it. This wasn’t going to be an ordinary hot dog. The cart became a tiny test of a bigger belief: that the standards and care of fine dining could elevate even the simplest food, served quickly, at park-bench prices.

The menu reflected his roots. In 2001, Meyer sold Chicago-style hot dogs—still a novelty in New York at the time. Garutti later told Bon Appétit that it came straight from “Danny’s Midwest upbringing.” Meyer grew up in St. Louis and had a specific idea of what a great Chicago-style dog should be—something you “never really see outside Chicago,” and definitely didn’t see in New York back then.

Then the unexpected thing happened. People didn’t just buy a hot dog. They lined up for it. They waited—sometimes thirty minutes or more—for a cart that was originally meant to support an art installation. The demand was so strong the cart returned for the next two summers. Day after day, for three straight summers, the line became part of the park’s scenery.

Inside USHG, that created the most interesting kind of problem: not “how do we drive traffic,” but “why is this happening?” Why were busy office workers and New Yorkers on lunch break spending that much time for a hot dog?

The answer was less about hot dogs than about what fast food usually forgot. People wanted quality. They wanted to be treated like guests, not processed like transactions. They wanted the feeling Meyer had made famous in his dining rooms—warmth, care, pride in the product—delivered in a format that was affordable and quick enough to fit into the middle of a workday.

And here’s the irony: it didn’t even work as a fundraiser at first. All profits were promised back to Madison Square Park. But in its first two years, the stand lost money. The philanthropic project couldn’t generate the donations it was designed to produce.

Yet the crowds kept coming anyway. The cart was failing on paper and succeeding in real life, which is often the most dangerous combination—because it means you’ve found something people genuinely want, even if you haven’t figured out how to capture the economics of it yet.

By the time the cart had been running for nearly three years, the Conservancy saw what was happening and pushed the next step. They asked Meyer to bid on a permanent food kiosk in the park. The accidental hit was about to become a deliberate one.

In 2004, the city began taking bids to operate the new kiosk-style restaurant. Meyer laid out his concept and, in July 2004, opened the first Shake Shack.

And yes—this is where the mythology gets its perfect prop. Meyer and Garutti sketched their early vision on the back of a napkin, a piece of corporate legend that still captures what they were thinking: burgers, crinkle-cut fries, frozen custard. It also shows the roads not taken, with ideas like a tuna burger, doughnuts, and espresso scribbled alongside the classics.

They even kicked around names that never made it out of the park: Dog Run, Custard’s First Stand, Custard Park, Madison Mixer, and—oddly enough—Parking Lot.

The shift from a charity cart to a permanent Shack revealed a pattern that would define Shake Shack’s entire story: not a brand launched by top-down planning, but a business pulled into existence by demand. Meyer hadn’t set out to build a burger chain. The customers, standing in line day after day, were the ones who insisted there should be one.

IV. Birth of the Shack & The Playbook Takes Shape (2004–2010)

On June 12, 2004, Shake Shack opened for business, and Madison Square Park immediately got a very different kind of “amenity” than anyone was used to. This wasn’t a cart you stumbled onto. It was a permanent, purpose-built kiosk—an upgrade in every way, and a signal that the Conservancy’s park revival was becoming real.

Shake Shack was born directly out of that redevelopment effort. The Madison Square Park Conservancy had recruited the design firm Pentagram to redesign the park’s visual identity pro bono. When the Conservancy decided to add a permanent food kiosk, the assumption was that this would be a one-off: a single stand that belonged to the park, not the first unit of a chain. So Pentagram folded Shake Shack into the larger project—creating the logo and the early brand identity, free of charge.

The result was the ivy-covered kiosk on the park’s southwest corner: the first Shake Shack in the world. And at the beginning, that’s all it was supposed to be. Not a rollout. Not a category play. Just a great little place in a great public space.

Then opening day happened.

Within half an hour, roughly 450 people were in line. It remains the longest line in Shake Shack history. By the afternoon, the stand had sold through its supply of about 1,000 burgers. New York didn’t “discover” Shake Shack gradually. It showed up all at once.

The menu quickly snapped into focus around the items that would define the brand: ShackBurger, crinkle-cut fries, and frozen custard. The simplicity wasn’t a lack of imagination—it was the strategy. Meyer wasn’t trying to reinvent American comfort food so much as rescue it. He wanted to make “these things taste even better than we remember them.” Randy Garutti framed it even more bluntly: “We wanted to look at everything fast food ruined over the last 60 years and just do it right.”

Doing it right meant starting with ingredients—and, just as importantly, with suppliers. One of the most consequential choices Shake Shack made early was beef. In 2004, Shake Shack began serving a custom burger blend from Pat LaFrieda Meat Purveyors. It was a fine-dining move in a park kiosk: the same butcher trusted by elite New York restaurants now supplying burgers to people eating on benches. As Shake Shack took off, so did LaFrieda’s visibility, and the partnership became part of the Shack story from the very beginning.

LaFrieda worked with the team to create a proprietary blend built around whole-muscle cuts—no trimmings, no added fat—ground fresh. LaFrieda, a major name in the meat world, sells hundreds of millions of dollars of product a year across the industry. But what mattered for Shake Shack wasn’t LaFrieda’s scale. It was the signal: this burger stand was sourcing like a serious restaurant.

That choice captured the core bet: take the supply chain standards of fine dining, accept higher costs, and charge a premium because the product actually earned it.

And here’s the other move that defined the era: Shake Shack didn’t chase growth. It refused to.

From 2004 through 2010, what’s most striking is how little expanded. It took four years to open the second location, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. In a business where success usually triggers a land grab, Shake Shack stayed almost stubbornly still—one location, building mystique and muscle at the same time.

That constraint became its own marketing. The line in Madison Square Park wasn’t just a hassle; it was proof. Proof that this was worth waiting for. Proof that this wasn’t another burger place. Shake Shack opened years before the iPhone, and later grew up in the social media era, when being seen in the Shake Shack line became a kind of cultural badge.

The economics of that single kiosk made the temptation to expand even sharper. The Madison Square Park Shack eventually generated average weekly sales of nearly $79,000 per location—more than $4 million a year from a small footprint in a public park. It was an early demonstration that the “premium fast” model could produce extraordinary results when the brand and the location matched perfectly.

But the numbers weren’t the whole point. The Shack was turning into something that felt bigger than a restaurant: a gathering place, a neighborhood ritual, a tourist stop, a shared experience.

Timing helped. The mid-2000s were the moment when “foodie” culture, artisanal craft, and backlash to industrial sameness started reshaping what people wanted from everyday eating. Shake Shack sat right at that intersection. It wasn’t precious. It wasn’t trying to be exclusive. It was a burger stand. It just happened to care deeply about the beef, and the bun, and the custard, and how you were treated when you walked up to the window.

Meyer also resisted the fastest lever for restaurant growth: franchising. It looked conservative financially, but it was strategically consistent. Control over quality and culture stayed centralized, and the Madison Square Park team could be trained directly in USHG’s hospitality philosophy. When you only have one Shack, you can obsess over every detail. You can protect the feeling.

By the end of this period, the Shake Shack playbook was clear: premium ingredients, real hospitality, A-plus locations, and an almost deliberate sense of constraint—growth pulled by demand, not pushed by capital. The rest of the company’s story is what happens when that playbook meets the question every cult brand eventually faces: can you scale it without breaking it?

V. The Expansion Question & Growth Strategy (2010–2015)

Inside USHG, the debate was real and a little scary: could the Shake Shack experience exist anywhere else, or was it inseparable from Madison Square Park? A park kiosk with a cult line is one thing. A repeatable business is something else entirely.

The origin story of the second Shack reads like legend because it was so unplanned. In 2007, Randy Garutti was walking home on the Upper West Side when he spotted a “for rent” sign in a storefront window. He called Danny Meyer on the spot. The two moved quickly, chasing the simplest question imaginable: what happens if we try to do this again?

That night, Garutti went home to his pregnant wife and told her he was going to focus exclusively on burgers and see what Shake Shack could become.

In 2008, as they built and opened the Upper West Side location, Garutti took over day-to-day leadership of the Shack. And then came the most important signal in the company’s early history: the second Shack was even busier than the first. The magic wasn’t just a park phenomenon. It replicated.

Then Shake Shack made a move that, at the time, looked almost backwards. It started going global before it had fully blanketed the U.S.

In April 2011, Shake Shack opened its first international location at the Mall of the Emirates in Dubai. A few months later, in July 2011, it opened in The Avenues in Kuwait. Garutti later said Kuwait was the moment he knew the concept could go big. These openings weren’t just about growth—they were also experiments with asymmetric downside. The logic was simple: if something went wrong in Dubai, it wouldn’t sink the U.S. business.

To fund what came next, Shake Shack brought in sophisticated capital. Leonard Green & Partners, the Los Angeles-based private equity firm known for retail and consumer investments, invested in the business. The value wasn’t just the check. Leonard Green’s experience helped Shake Shack move faster—accelerating new openings and supporting experimentation with menu items and formats.

As Shake Shack grew, the leadership structure caught up to reality. Danny Meyer put it plainly in his praise of Garutti’s rise through USHG: he’d built followings among teams as a leader rooted in enlightened hospitality, and when the hot dog cart became a kiosk in the park, “Randy asked for the ball.”

Garutti ended up shaping the company for nearly two decades. He became CEO in 2012 and served in that role through 2024, after previously leading as COO. The operator behind the vision had formally taken the wheel.

Even as the footprint expanded, the real estate philosophy stayed strict: “A-plus positioning” or nothing. High visibility. High foot traffic. No settling. That discipline slowed unit growth, but it also made the economics more dependable. And it pushed Shake Shack toward the kinds of venues that amplified the brand: Citi Field, JFK Airport, and then other airports and stadiums—places where people were already primed to pay a premium and where the Shack could become a destination inside the destination.

Internationally, the playbook kept building. In mid-2013, Shake Shack opened its first European location in London, landing in the same area where Five Guys had just arrived. That wasn’t an accident. The “better burger” wave was hitting the city, and Shake Shack wanted to claim its spot early.

Through all of this, Meyer held the line on one of the company’s most defining choices: no traditional franchising. Franchising could have made growth faster and more capital-efficient, but it also invited the two things Shake Shack was terrified of—quality dilution and cultural drift. Training and exporting hospitality were hard enough with employees you hired and developed yourself. With franchisees, the fear was that someone, somewhere, would decide the corners were worth cutting, and the brand would pay for it.

By 2014, Shake Shack had 63 locations worldwide and serious IPO buzz. Revenue in the first three quarters of the prior year hit $83.8 million, up more than 40% versus the same period in 2013, and the company was profitable.

The stage was set. Shake Shack was about to shift from private darling to public company—and that one change would rewrite the rules around growth, culture, and expectations overnight.

VI. The IPO: Going Public as a 31-Location Company (2015)

By January 2015, Shake Shack had become exactly the kind of story Wall Street couldn’t resist. The IPO market was hot. Fast-casual was hot. And investors were hunting for “the next Chipotle.” Shake Shack—premium, cultish, line-out-the-door famous—fit the narrative perfectly.

On January 30, 2015, Shake Shack went public at $21 a share. Then the market did what the market does when it falls in love: it immediately bid the stock up. Shares opened at $47, briefly traded above $52, and ended the day just under $46. In a single session, Shake Shack went from a beloved burger chain to a company worth roughly $1.6 billion—nearly $1.8 billion at the intraday peak.

The run-up started even before the first trade. Expectations had already been rising. Analysts initially thought the IPO would price in the mid-teens, then the anticipated range lifted into the high teens. Even that proved too low once demand hit. Shake Shack sold 5 million shares and raised about $90 million—but the bigger headline was what the first day said about appetite for the brand.

For Danny Meyer, it was also a real liquidity event. Meyer owned about 21% of the company—roughly 7.4 million shares of Class B stock—meaning the IPO could translate into a personal windfall on the order of $140 million.

The backdrop explains a lot of the euphoria. Restaurant IPOs like the Habit Burger Grill and Zoe’s Kitchen had been performing well, and Chipotle’s rise after its 2006 IPO had become the decade’s most seductive comp: a chain that looked like “just food” but traded like a growth stock. Investors were trying to spot the next one early.

And in the months after Shake Shack’s debut, the stock only poured fuel on that belief. It climbed fast, peaking at $92.86 in May 2015—an all-time high that put the company, briefly, in the rare air of a restaurant darling priced like a tech breakout.

But the valuation immediately raised eyebrows, because the underlying footprint was still small. Shake Shack operated 63 restaurants worldwide, and 16 were in the New York metro area. A company of that size carrying a nearly $2 billion market cap implied breathtaking expectations. On paper, the market was valuing each restaurant at more than $25 million—multiples that only made sense if Shake Shack could take what worked in Madison Square Park and reproduce it again and again, at massive scale.

Here’s the twist: Shake Shack wasn’t promising massive scale. Management said it wanted to expand relatively slowly—targeting around 10 new U.S. locations per year, plus international growth. So from day one, the core tension was set. Wall Street priced Shake Shack for hyper-growth. Shake Shack signaled measured expansion.

So why go public so early? Expansion capital was part of it, but it wasn’t the whole story. Meyer needed liquidity for Union Square Hospitality Group and for investors like Leonard Green. The public markets offered an exit path and ongoing liquidity that private markets couldn’t replicate. And being public came with other advantages too: stock as currency for employee compensation, and a higher profile when negotiating for the kinds of premium real estate Shake Shack insisted on.

The S-1 was written for the moment and with intention: a premium brand with values, community roots, and a clear contrast with traditional fast food. It wasn’t “we sell burgers.” It was “we stand for something.”

From its premium ingredients and progressive hiring practices to its environmentally responsible designs and deep community investment, Shake Shack's mission is to Stand For Something Good®.

Of course, the morning after an IPO isn’t a celebration—it’s a new job. The pressure was immediate and predictable: grow faster. But Shake Shack’s advantage wasn’t a secret recipe. It was quality and culture—two things that don’t scale just because your market cap says they should.

The challenge that would define the next decade had officially begun: balancing Danny Meyer’s philosophy with shareholder expectations.

VII. Rapid Expansion & Growing Pains (2015–2019)

The years after the IPO put Shake Shack’s entire thesis on trial: could Enlightened Hospitality survive once the company was living on a quarterly clock?

The headline growth was undeniable. According to Technomic data cited by Restaurant Business, global system sales went from under $100 million in 2012 to $1.3 billion by 2022. But that kind of arc can hide what it actually takes to scale a hospitality-first brand: new markets, new managers, new supply chains, and thousands of new moments where the experience either feels like Shake Shack… or it doesn’t.

To meet public-market expectations, Shake Shack accelerated hard. Unit development jumped to more than 30 stores a year—an entirely different rhythm from the slow, myth-building pace of the Madison Square Park era. The expansion map stretched across the country, including the West Coast, where In-N-Out had owned the cultural conversation around premium fast-food burgers for decades. In California, Shake Shack stayed concentrated in L.A. County at first, until it opened its sixth location in the state—its first in San Diego—on October 20, 2017 at Westfield UTC.

And as the footprint spread, the economics started to change. The early Shacks had been planted in places that did half the marketing for you: iconic parks, dense neighborhoods, stadiums, airports, downtown corridors packed with foot traffic. But as Shake Shack moved outward into more suburban trade areas, it ran into an inconvenient truth: the Madison Square Park magic didn’t automatically follow. The novelty that could drive huge first visits didn’t always translate into habit, and same-store sales pressure began to show up as the “new-Shack shine” wore off.

At the same time, the competitive landscape tightened. Five Guys was already a national force, built on customization and an aggressive franchising model. Culver’s owned the Midwest with a devoted following. And the big incumbents—McDonald’s, Wendy’s, and others—started adopting pieces of the “better burger” playbook, from ingredient upgrades to fresher positioning. Shake Shack had gone public as a premium outlier. It was now competing in a world where “premium” was rapidly becoming table stakes.

The company also leaned into technology, both as defense and as a new growth engine. The app, third-party delivery, and in-store kiosks became increasingly important. By 2019, digital and kiosk sales were about $147 million, roughly a quarter of the mix. That channel expanded dramatically over the next few years, and by 2022 it approached $500 million, representing more than half of sales—a clear sign that the Shack experience was no longer just about the line in the park.

Menu experimentation followed the same logic: increase reasons to visit and increase frequency. Chicken Shack, limited-time offerings, breakfast tests in select locations, and alcohol at certain venues were all attempts to widen the brand beyond “the burger you get when you’re craving it.”

In the market, the stock told the story of investor uncertainty. It had traded above $90 at its peak, then slid into the $40s as growth questions piled up. Wall Street couldn’t quite settle on what it was looking at: a premium brand worthy of premium multiples, or a still-small chain facing the same saturation and competitive pressures as everyone else.

Internally, the scaling challenge got even harder. Running 63 restaurants is a culture project. Running more than 200 is a systems project—hiring senior leadership, building the corporate muscle, and finding a way to transmit “this is how we do things here” without Danny Meyer in the room. Shake Shack emphasized internal development in operations leadership—filling nearly 60% of those roles from within. Of those promotions, 77% went to people of color, and more than half went to women.

By the end of this era, the tension was no longer theoretical. It was the company’s defining question: can you be Danny Meyer at scale? The philosophy depended on care, consistency, and human touch. The larger Shake Shack became, the more that philosophy had to be embedded into training and systems—and the more brutal it was when execution slipped, even slightly.

VIII. Existential Crisis & Inflection Point: COVID-19 (2020–2021)

March 2020 brought the kind of shock no board deck can really prepare you for. Shake Shack’s edge had always been physical: the line, the park bench, the feeling that you were part of a small New York ritual. COVID didn’t just slow that down. It turned the core experience into the problem.

In the first weeks, sales fell off a cliff. U.S. sales dropped as much as 90% at the worst point, and averaged down about 70%—a decline that looked more like full-service dining than the quick-service world Shake Shack was often compared to. The company itself painted a bleak picture: this wasn’t a temporary dip, it was an immediate threat to the model.

And the very thing that had powered Shake Shack’s rise—urban concentration—suddenly became a liability. Most Shacks were built for dense foot traffic, not drive-thru lanes. They were designed around walk-up ordering and in-person energy, not curbside pickup and delivery routes. While fast-food rivals could lean on drive-thrus and established digital habits, Shake Shack had to rebuild the plane in midair.

The cost cuts came fast. Sales were down about 70% systemwide. Roughly 20% of corporate staff were laid off or furloughed. The company put salary reductions in place for executives and headquarters staff, froze hiring, reduced staffing levels, and halted design and construction on new units—with no plans to open new stores that year.

What kept the story from turning into a disaster was the balance sheet. Shake Shack had not loaded up on long-term debt going into 2020. That gave it room to move: in late March, it drew $50 million from its revolving credit facility. In April, it raised additional cash by selling stock. By the time the company reported first-quarter 2020 results, management said it had $247 million in cash and equivalents, with just the revolver draw showing up as debt.

On April 21, 2020, Shake Shack completed two equity sales: one for 233,467 Class A shares, raising $9.8 million, and an underwritten offering of 3,416,070 Class A shares, raising $135.9 million.

Then came the operational pivot—rapid, broad, and, for Shake Shack, unusually unromantic. The company ended its exclusive relationship with Grubhub and expanded delivery across more platforms, including Postmates, DoorDash, Caviar, and Uber Eats. It developed a new store format called Shack Track, built around dedicated pickup areas and, crucially, a drive-thru.

That drive-thru decision was the real philosophical break. For years, Shake Shack had resisted drive-thrus as incompatible with what the brand was “about.” COVID forced the company to revisit that assumption. The chain opened three drive-thrus and planned to reach as many as 10 by the end of 2022.

Digital went from a nice-to-have to survival. In March 2020, digital sales were 23% of the business—a figure that, in context, underlined how dependent Shake Shack still was on the in-person experience. But the shift came quickly, and digital became a much larger share of how customers interacted with the brand.

At the same time, the pandemic exposed a stark split between urban and suburban Shacks. Revenue at urban locations fell 57%, versus a 38% decline in suburban restaurants. By July 2020, urban stores had recovered only modestly—still down 50%—while suburban locations improved more meaningfully, down 24%. One internal lens made the point even sharper: if you took the 126 restaurants in the comp base and removed the bottom 25 performers—nearly all urban—Shake Shack’s April same-store sales versus 2019 improved from negative 15% to just under 3%. Former juggernauts like the Theater District and Herald Square Shacks, among the busiest the company had ever opened, were suddenly shadows of their old volumes.

Still, the recovery did come. By fourth quarter 2021, same-store sales finally edged above 2019 levels, up 2.2% versus the comparable pre-pandemic period.

And as the business stabilized, development restarted—fast. In 2021, Shake Shack opened 36 new company-operated locations and 23 licensed ones, and it planned to open up to 50 units in 2022. Nineteen of the 2021 openings landed in the fourth quarter alone.

In hindsight, COVID forced Shake Shack to do what it had been reluctant to do in normal times: diversify formats, embrace off-premise, and modernize operations at speed. The crisis was brutal, but it also compressed what might have been a decade of change into a matter of months.

IX. The Modern Era: Reinvention & New Growth Formula (2021–Present)

The Shake Shack that came out the other side of 2021 didn’t just look a little different. It was operating on a new set of assumptions. The biggest one was also the most symbolic: drive-thrus—once treated as incompatible with a park-bench, community-hangout brand—became central to the growth plan.

The company leaned hard into the format. The first drive-thru opened in 2021, and by late 2022 the pace accelerated, with a wave of drive-thru openings clustered into the fourth quarter. Management’s near-term goal was to reach roughly a few dozen drive-thrus by the end of 2023, and by the time of that push the system still had only a handful open—an early sign of how much runway the format created.

The opportunity was obvious: drive-thrus unlocked the suburban and exurban corridors Shake Shack historically couldn’t serve well with its dense, walk-up playbook. The tradeoff was cost. These boxes were more expensive to build—often in the $2.4 to $3 million range—meaning the company had to be right not just about the burger, but about throughput and repeat traffic.

Then the leadership baton passed.

On May 20, 2024, Shake Shack’s board appointed Rob Lynch as CEO and a board member. Lynch came from Papa John’s, where the company pointed to record global system-wide sales during his tenure. Before that, he was president of Arby’s, overseeing operations, marketing, culinary, development, and digital transformation across thousands of restaurants in multiple countries.

It was a clear signal about what the next chapter needed. In his first earnings call as CEO, Lynch framed the mission in simple terms: Shake Shack doesn’t struggle to get first-time visits. The job now is to become a more frequent choice—without cheapening what made the brand special in the first place.

The barriers, in his view, were practical and solvable: speed of service and value perception. As Lynch put it, the team was working on both—evolving menu strategy and limited-time offerings, and rethinking how the brand “positions things” across the menu and revenue model to improve value perception—while insisting they wouldn’t degrade product quality or the experience.

Underneath that was a bigger ambition: the scale story changed.

Shake Shack updated its long-term outlook and said it now saw the potential for at least 1,500 company-operated Shacks over time. That was a massive jump from the 450-location target the company had shared around its February 2015 IPO. By the end of fiscal 2024, Shake Shack had 329 company-operated stores—still early innings relative to that new ceiling, and a hint at how much the format mix and real estate strategy had evolved since the park-kiosk days.

Financial performance helped make the case that this wasn’t just an aspirational slide. In fourth quarter 2024, total revenue rose to $328.7 million, up 14.8% versus the prior year, including $316.6 million in Shack sales and $12.1 million in licensing revenue. System-wide sales grew to $500.7 million, up 13.3%, and same-Shack sales were up 4.3%.

For full-year 2024, total revenue reached $1,252.6 million, up 15.2% year over year, including $1,207.6 million in Shack sales and $45.0 million in licensing revenue.

Just as important as the revenue growth was how guests were ordering. Digital wasn’t a side channel anymore—it was the default. More than half of in-Shack sales were coming through self-service kiosks. And when you add kiosks, web, app, and delivery together, digital accounted for about 80% of total sales. The line in the park had been replaced by a screen in your hand—and the company was building the operating model to match.

Internationally, Shake Shack kept expanding, but with a tone that was more disciplined than exuberant. The brand was operating in around 25 countries across the Middle East, Asia, and the U.K. Lynch noted that “continental Europe is still wide open,” while emphasizing that Shake Shack had been deliberate—choosing markets and partners carefully rather than simply planting flags.

Canada became the next proof point. In March 2023, Shake Shack announced plans to enter the market with a flagship location in 2024, with a longer-term plan to reach 35 Shacks by 2035. On June 13, 2024, Shake Shack opened its first Canadian location at Sankofa Square in Toronto.

By this point, the business had clearly regained its footing. Shake Shack reported sixteen straight quarters of positive revenue growth. New Shacks were posting average unit volumes above $4 million. And the company generated over $30 million in free cash flow—an especially notable milestone after years of building.

Management also put words around the operating focus with its 2025 strategic priorities: building a culture of leaders, optimizing restaurant operations, driving comp sales by increasing guest frequency, building and operating Shacks with best-in-class returns, accelerating the licensed business, and investing in long-term strategic capabilities.

And despite being a global brand, Shake Shack still leaned on an old-school advantage: it spent very little on advertising. CFO Katie Fogertey told Nation’s Restaurant News the company spends about 1% of total revenue on ads—low versus peers—and argued that as Shake Shack scales, it benefits from being known as the underdog. She also emphasized that each Shack aims to feel local, not cookie-cutter: the goal is still to be someone’s neighborhood hangout spot, even if the order now comes from a kiosk and the pickup might happen in a drive-thru lane.

X. Power Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Shake Shack’s story is driven by culture and brand. But whether it can keep winning comes down to something colder: industry structure, and what advantages actually hold up when everyone else is trying to copy you. Two useful lenses here are Porter’s 5 Forces—what the category does to you—and Hamilton’s 7 Powers—what, if anything, you uniquely own.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Burgers are a knife fight. Shake Shack gets squeezed from every direction: regional cult favorites like In-N-Out, national chains like Five Guys and Culver’s, private equity-backed concepts chasing growth, and the giants—McDonald’s and Wendy’s—who have spent the last decade upgrading ingredients and messaging to play in the same “better burger” lane.

The scale gap is also real. Wendy’s and Burger King each operate more than 6,000 locations. In-N-Out, arguably the most direct brand competitor, has roughly 415 U.S. restaurants—and still manages to dominate the conversation in the West by staying focused and disciplined.

The uncomfortable truth is that what made Shake Shack feel revolutionary in 2004—freshness, better ingredients, an elevated experience—has been copied so widely that it’s no longer automatic differentiation. The moat shrinks as the category catches up.

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

Starting a restaurant concept doesn’t require massive capital, and the steady drumbeat of celebrity-backed and chef-driven burger concepts proves that new entrants never stop coming. What’s hard isn’t opening a burger place—it’s building a brand people will wait for, talk about, and return to years later. Most new concepts flame out within five years.

Shake Shack does benefit from real barriers, though: access to prime real estate and the capital needed to build in A-plus locations. It’s easy to launch. It’s hard to launch where Shake Shack wants to be.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

Shake Shack’s early supply chain choices were part of the brand, especially Pat LaFrieda. LaFrieda has supplied Shake Shack’s beef since the first restaurant opened in 2004, though Shake Shack has sometimes also used other unnamed providers. LaFrieda may only supply beef to Shake Shack’s U.S. locations.

That relationship helps lock in consistency, but it also creates some dependency. Still, Shake Shack is now big enough to negotiate effectively, and its premium positioning gives it some ability to pass higher costs along to guests. The bigger risk here isn’t supplier leverage—it’s commodity volatility hitting margins.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

Customers have endless options and can switch with zero friction. Shake Shack may inspire affection, but there’s no structural lock-in—no subscription, no real switching cost beyond habit and maybe loyalty points. Delivery platforms tilt the table even further toward consumers and the apps, making it easier to compare, swap, and abandon brands on a whim.

Threat of Substitutes: VERY HIGH

In food, everything is a substitute for everything else. That includes not just other burger chains, but every nearby restaurant, meal kits, home cooking, and the sprawling universe of delivery-only concepts. Longer-term, health trends that push consumers away from red meat and fried food create headwinds. And in recessions, premium burgers are exactly the kind of “little luxury” people reassess—either trading down or eating at home.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: WEAK

Shake Shack gets some purchasing leverage as it grows, but not the kind that changes the game. Labor and rent are local. Real estate is negotiated one deal at a time. And Shake Shack will never out-scale a McDonald’s with tens of thousands of restaurants.

2. Network Effects: NONE

This is a classic linear business. More Shacks don’t inherently make each Shack more valuable to customers in the way a marketplace or social network does. There’s no demand-side flywheel.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE (Fading)

At launch, Shake Shack was meaningfully counter-positioned against fast food: premium ingredients, a hospitality-first culture, and no franchising. Big incumbents couldn’t copy that without undercutting their own value propositions.

But the industry adapted. Fresh beef rolled out elsewhere. “Premium QSR” became common. What used to be a sharp contrast has blurred into a crowded middle.

4. Switching Costs: NONE

If you’re not feeling Shake Shack today, you can pick a different burger in five minutes. Loyalty programs add a little stickiness, but nothing close to true lock-in.

5. Branding: STRONG (Core Power)

This is the real asset. Shake Shack’s brand has emotional resonance. The Danny Meyer origin story signals authenticity. And the positioning—an “affordable luxury” burger—supports a real price premium.

“Shake Shack, I've always called fine casual. It's not fast casual. Shake Shack was born from our company using the same beef we use at Union Square Cafe, recipes tested in the kitchen of Eleven Madison Park, so it was born from fine dining.”

That said, brand power isn’t uniform everywhere. It’s weaker on the West Coast, where In-N-Out has near-religious loyalty, and stronger in the Northeast and in international markets where the New York origin story carries extra cultural weight.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK-MODERATE

Meyer’s hospitality ethos and USHG’s cultural DNA are valuable—but not uncopyable. Prime real estate can be an advantage, but competitors can pursue the same corners. And there are no patents or true trade secrets here; a premium burger blend can be approximated.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

Shake Shack does have process power in the form of training and operating systems rooted in Enlightened Hospitality. The idea became a cultural engine—employees stepping up for hard tasks, learning quickly, and reinforcing the service mindset that made the brand feel different.

The challenge is that process power is hardest to defend at scale. Keeping it intact across 500+ locations—and eventually 1,500—is brutally difficult, especially when competitors can observe and imitate what’s visible.

Overall Power Assessment:

Shake Shack’s main durable advantage is Brand. But it comes with constraints: it’s geographically uneven, it’s easier for competitors to imitate the product than the mythology, and it can be diluted if growth outpaces execution.

The core challenge now is converting brand equity into a true economic moat. That requires operational excellence at a scale Shake Shack is still in the process of proving it can sustain.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

The Bull Case

The optimistic thesis rests on a few simple ideas: Shake Shack has a premium brand people will pay for, it now has a format that can reach far more of America, and it’s built a machine—digital, operational, and cultural—that can support a much bigger footprint.

Premium Brand with Pricing Power: In an inflationary environment, the brands that matter are the ones that can raise prices without breaking demand. Shake Shack has shown it can do that, because a meaningful slice of customers still treat it as “worth it”—a premium experience in a category where most options blur together.

Drive-Thru Format Unlocks Expansion: The pandemic-era pivot to drive-thrus didn’t just add convenience. It opened up suburban and exurban markets that the original, walk-up city playbook couldn’t serve well. The company has been refining the format in real time—learning where traffic is strongest, where brand awareness is highest, and even how much dining room it actually needs. As management put it: “We think we can continue to build a drive-thru that’s really distinct and exciting in the industry.”

International Whitespace: International results move with local macro conditions—especially in Asia and the Middle East—but the broader point is that Shake Shack still has plenty of new markets to enter. Newer moves like Canada, and talk of markets such as Mexico, point to continued runway. And because international growth is largely licensed, Shake Shack can expand brand reach without carrying the full capital burden.

Digital Transformation Improving Unit Economics: With roughly 80% of sales now flowing through digital channels, Shake Shack has more levers than it used to. Digital ordering can improve labor efficiency, reduce friction in the guest experience, and generate better customer data—fuel for smarter marketing and, potentially, better margins.

Underpenetrated Relative to Addressable Market: Rob Lynch has been explicit about the opportunity: “We believe that we are just getting started, and see an ample runway for growth ahead.” With 329 company-operated locations today and a stated long-term goal of 1,500, the bull case is essentially a whitespace story—if Shake Shack can keep the experience consistent, it has a lot of country left to fill in.

Leadership Team Battle-Tested: The company made it through COVID, which forced rapid adaptation and exposed weaknesses fast. And now it has a new CEO who has operated at scale elsewhere, with experience from Papa John’s and Arby’s—brands built around throughput, consistency, and repeat frequency.

The Bear Case

The skeptical thesis is equally straightforward: this is a brutally competitive category, Shake Shack doesn’t have an unassailable moat, and scaling “premium” is where restaurant brands go to die.

No Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Burgers are easy to copy. Premium ingredients can be matched. Hospitality culture is hard to replicate—and even harder to maintain as you stretch across hundreds, then thousands, of units. Meanwhile, many regional competitors have deeper local loyalty than Shake Shack can easily win.

Unit Economics Under Pressure: Margins get squeezed from both sides: input costs like beef rise, while competitors push aggressive pricing and promotions. That’s a tough environment to fund expansion, especially when new formats cost more to build.

Same-Store Sales Inconsistency: The key question is whether growth is coming from more people showing up, or simply from higher pricing and customers trading up on the menu. In the quarter referenced here, same-store sales grew about 4%, but traffic was down 0.8%—a reminder that comp growth can look healthy while frequency quietly softens.

Premium Positioning Vulnerable in Recession: When consumers feel pressure, they trade down. Shake Shack’s higher price point—roughly double McDonald’s—can shift from strength to weakness if “treat” occasions get cut from the budget.

Execution Risk at Scale: Running 329 company-operated Shacks is hard. Running 1,500 is a different species of problem. The brand has to maintain quality, speed, and culture across an organization it has never operated at before—and history is littered with premium concepts that couldn’t keep the magic as they expanded.

Valuation Remains Elevated: Even with volatility, the stock still implies a lot of future success. A P/E ratio around 83.61 means investors are paying today for growth that has to show up consistently tomorrow.

Can Never Achieve In-N-Out Economics: In-N-Out gets to expand patiently as a private company, without quarterly pressure. Shake Shack, as a public company, can’t replicate that structural advantage—and that difference matters in a business where discipline is everything.

Key Performance Indicators to Monitor

If you want to know which story is winning—bull or bear—three metrics tell you most of what you need to know:

-

Same-Shack Sales Growth (Traffic vs. Pricing): Traffic is the heartbeat. If traffic grows, it means frequency is improving, which is exactly what Lynch says he’s focused on. Pricing-driven comps without traffic are more about testing elasticity than building demand.

-

New Unit AUVs and Payback Periods: New Shacks have been posting average unit volumes above $4 million. The real test is whether newer drive-thru and suburban locations can deliver economics that hold up outside the historic urban sweet spots.

-

Restaurant-Level Profit Margin: Management has indicated restaurant-level margins could potentially reach 22% in 2025. Whether margins actually move that direction will reveal if scale and digital efficiencies are taking hold—or if labor, rent, and commodity pressure are winning.

XII. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

The Shake Shack story leaves behind a playbook that’s useful far beyond burgers. If you’re building a brand, scaling operations, or deciding when to take outside capital, there are a few lessons here that keep repeating.

Culture as Competitive Advantage

The idea that employees come first wasn’t a slogan for Danny Meyer. It was the operating system. USHG’s evolution from a handful of restaurants into a multi-faceted hospitality organization was built on that ordering.

Meyer’s “Enlightened Hospitality” hierarchy—employees first, then guests, then community, then suppliers, and finally investors—created an employee experience that could reliably produce a customer experience people talked about. The takeaway is simple: culture isn’t soft; it’s strategic. The harder question is the one Shake Shack has spent twenty years testing in public: can you scale it, or does it inevitably thin out?

Intentional Scarcity as Strategy

Shake Shack stayed a one-location phenomenon for years before it opened a second Shack. In an era where success usually triggers a land grab, that patience compounded brand equity. The Madison Square Park line became marketing you didn’t have to buy, and constraint made the product feel rarer—and therefore more desirable.

Premium Positioning in "Commoditized" Categories

For decades, the burger business trained consumers to expect cheap and fast. Shake Shack proved there was room—real room—for a premium tier if you delivered on quality and experience. The lesson is that “commoditized category” is often just shorthand for “we’re not differentiating.” There’s almost always a segment of customers willing to pay more for something they can feel.

The Line as Marketing

Long waits should be a problem. For Shake Shack, they became part of the signal. A visible line communicated, instantly, that this was the place worth choosing. Later, social media turned that signal into a loop: people posted the line because it meant something, and the posting made the line longer. The takeaway: sometimes the constraint is the feature.

Real Estate as Strategy

Shake Shack treated site selection like brand-building, not just unit economics. A-plus locations—parks, high-traffic streets, airports, stadiums—didn’t merely generate sales. They reinforced what the brand stood for. A Shack in a premier spot feels like a destination; a Shack in a forgettable strip mall feels like just another chain. Location is positioning.

Anti-Franchise Model

Shake Shack’s decision to avoid traditional franchising made growth slower and less capital-efficient, but it protected quality and culture. That tradeoff was the point. The lesson isn’t “never franchise.” It’s that not every growth lever is worth pulling—because some levers accelerate you toward a version of the company you don’t actually want to become.

Public Market Pressures

The IPO rewired the incentives overnight. Quarter-by-quarter expectations don’t care about brand mythology, training time, or the patience it takes to find the right corner. The lesson for founders is straightforward: going public isn’t free money. It’s agreeing to a growth trajectory that may collide with the way you built your brand in the first place.

Crisis as Catalyst

COVID forced Shake Shack to embrace changes it had resisted: drive-thrus, digital-first behavior, and new formats built for off-premise. The lesson is that shocks can compress years of internal debate into months of action. Sometimes the crisis doesn’t invent the next strategy—it just removes the option of waiting.

Founder-Operator Dynamics

Meyer brought the philosophy and the standards. Randy Garutti spent two decades translating that into repeatable operations. That pairing—vision plus execution—is one of the most underrated advantages in scaling any service business. It also raises the succession question: what happens when the operator changes? Rob Lynch now steps in with deep experience running at scale, and his challenge is to increase frequency and throughput without stripping out the very “feel” Meyer built the brand on.

Brand Extension Limits

Every beloved concept eventually faces the same question: how big can you get before you stop being you? Shake Shack’s long-term ambition—1,500 company-operated locations—assumes the brand can scale without losing the thing people were lining up for in the first place. That bet will define the next decade, because history is full of hospitality brands that grew successfully on paper and quietly diluted the magic that made them matter.

XIII. Epilogue & Future Scenarios

As 2025 closes, Shake Shack sits in a fascinating place in the American restaurant landscape: big enough to matter, still small enough to be debated. Two decades have passed since a summer hot dog cart in Madison Square Park turned into something neither Danny Meyer nor Randy Garutti could have fully predicted. Shake Shack has now hit its 20-year mark.

The 2025–2030 roadmap is, at least on paper, straightforward: expand hard toward a much larger company-operated footprint, keep building drive-thrus to reach the suburbs, and keep pushing internationally through licensing partners. The company plans to open 85 restaurants in 2025, and it continues to talk about a long-term future that reaches 1,500 locations in the U.S.

The harder part is what that roadmap collides with: technology. AI-powered ordering, kitchen automation, ghost kitchens, and delivery-only brands are reshaping what “restaurant” even means. Shake Shack is investing in automation and predictive systems, but the thing that made the brand feel different—hospitality—has traditionally lived in the human moments, not in the software.

At the same time, sustainability and values-driven dining keep rising in importance, especially for younger customers. Shake Shack’s Stand For Something Good positioning fits the moment. But as the company scales, the only version that matters is the one that holds up in execution—real environmental and social choices, consistently applied—rather than values as marketing copy.

Then there’s the question that always follows a beloved public company in a brutal industry: does someone buy it? A strategic acquirer, a private equity rollup, even a take-private scenario that trades quarterly pressure for long-term investment—none of this appears imminent. But it also isn’t fantasy. Shake Shack has the kind of brand that makes people run the thought experiment.

Danny Meyer remains Chairman of the Board of Shake Shack (NYSE: SHAK) and Union Square Hospitality Group. His presence still acts as cultural glue. But the longer-term succession question—what happens when the founder’s active involvement fades further—hangs over the story more than most people want to admit.

So which future is more likely? Shake Shack as the next Starbucks: a premium brand that reaches massive scale without losing its soul. Or Shake Shack as a cautionary tale: a hospitality-first culture thinned out by operational complexity and growth ambition. The tension between those two outcomes will define the next chapter.

And that’s what makes this story feel quintessentially American. It’s the improbability of it—a charity hot dog cart becoming a billion-dollar enterprise. It’s the aspiration of it—taking the humble burger and making it feel like something you’d wait in line for. And it’s the eternal tradeoff at the heart of American business: craft versus scale, art versus efficiency, doing it right versus doing it fast.

The biggest surprise in researching this story was how much of Shake Shack’s early success came from constraint. In an era that worships growth, the company’s patient first decade—one location for four years—feels almost radical. The line wasn’t just tolerated; it became the message. Scarcity turned into mythology.

The biggest open question is the one we may have been too quick to assume away: can hospitality culture actually survive scale? The jury is still out. At 329 company-operated locations, the USHG DNA is stretched, but it’s still recognizable. At 1,500, the math gets unforgiving. Training systems, regional leadership, and the ability to transmit “this is how we do things here” will be tested in ways the Madison Square Park era never had to confront.

The Shake Shack story is still being written. What began as Danny Meyer’s gift to Madison Square Park became a publicly traded company that changed how America thinks about the modern burger. Whether it can keep its soul while chasing the growth curve public markets demand remains the central drama—and the central investment question—for the decade ahead.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music