Red Rock Resorts: The Station Casinos Story of Dominating Las Vegas Locals

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

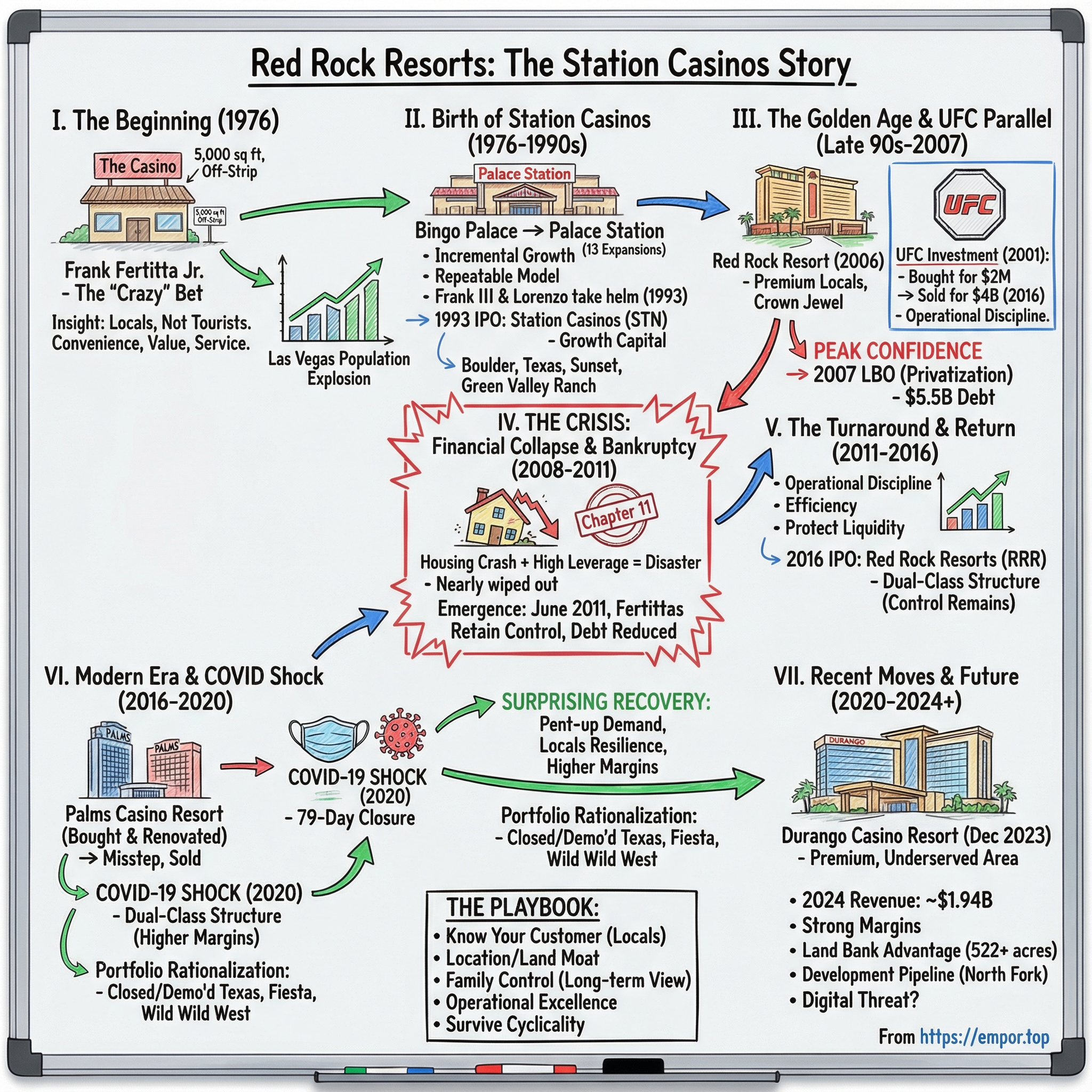

Picture this: it’s July 1976. A former bellman turned casino manager named Frank Fertitta Jr. opens a tiny, 5,000-square-foot gambling hall on West Sahara Avenue. It’s bolted onto a budget motor inn, miles from the glittering Las Vegas Strip. He names it with no pretense at all: The Casino.

To almost everyone in town, it looks like a mistake. Why build a casino where there are no tourists?

But Fertitta wasn’t chasing visitors with cameras and comped show tickets. He was betting on the people who actually lived there. He ran the place with a locals-first vibe—friendly, familiar, service-driven. Years later, his son Lorenzo would sum up the reaction at the time: “everyone thought he was crazy for building off the Strip.”

Fast forward nearly five decades, and that little off-Strip experiment has become Red Rock Resorts, trading as RRR on the NASDAQ. In 2024, the company generated $1.94 billion in revenue, up about 12% from the year before. And the Fertitta family—the people who helped create what Las Vegas now calls the “locals casino” category—still holds the keys, controlling roughly 90% of the company’s combined voting power as of the 2025 record date.

This story has everything: a counterintuitive strategy that went against the entire casino industry’s instincts, a near-death spiral through bankruptcy that almost erased the family’s legacy, and a set of parallel business swings so wild they sound fictional—like turning a $2 million investment in the UFC into a $4 billion exit.

So how did the Fertitta family build a casino empire for Las Vegas residents—not tourists—then survive bankruptcy, go private, and return to the public markets stronger than ever?

It starts with one overlooked truth about Las Vegas that most operators missed entirely.

II. The Fertitta Family Legacy & Las Vegas Context

To understand Red Rock Resorts, you have to start with the person who saw Las Vegas differently.

Frank Joseph Fertitta Jr. (October 30, 1938 – August 21, 2009) wasn’t born into casinos. He was born in Beaumont, Texas, to Frank Joseph Fertitta and Josephine Grilliette. He graduated from Kirwin High School in Galveston in 1956, married Victoria Broussard two years later, and in 1960 the two of them drove west to Las Vegas—long before it was the polished, corporate playground people picture today.

Back then, Las Vegas was still a rougher ecosystem: organized crime families, a few legitimate investors, and a lot of people trying to find their angle. Frank Jr. found his the hard way—starting at the very bottom as a bellman at the Tropicana while learning the trade as a dealer. Over the next sixteen years, he climbed almost every rung you can climb in a casino: dealer, pit boss, baccarat manager, general manager. He worked at the Stardust, the Tropicana, Circus Circus, the Sahara, and the Fremont downtown.

That matters, because it meant he didn’t learn casinos from a spreadsheet. He learned them from the floor—watching which customers got treated like royalty, which customers got ignored, and what the business looked like when the weekend crowds cleared out.

Those years gave him an advantage that would become the Fertitta family’s edge for decades: he understood the industry from every angle, and he could see the demand everyone else was stepping over.

The tourists were obvious. The locals were not.

The Insight That Built an Empire

In the mid-1970s, Fertitta saw a gap: Las Vegas had casinos for visitors, but almost nothing built intentionally for the people who lived and worked there. So in 1976, he took the leap and opened his own place—simply called “The Casino.”

It was tiny, about 5,000 square feet, attached to the Mini-Price Motor Inn, and sitting off West Sahara Avenue, a short drive from Las Vegas Boulevard. As Lorenzo Fertitta told the Las Vegas Sun years later, “It was pretty much desert. People thought he was crazy.”

But the “crazy” part is what made it brilliant. Frank wasn’t trying to outshine the Strip. He was building something different: a neighborhood casino that felt easy and familiar. A place where casino employees could stop in after a shift, where regulars could actually park, eat affordably, and be treated like they mattered.

People around the business noticed the playbook forming. As one observer, Schreck, put it: “He created the buffet for locals. He brought bingo to locals. It was his idea to create easy access parking. These are commonplace now at every locals casino. That’s why he was a true pioneer. He was successful because he was committed to great customer service.”

In other words: convenience, value, and service—over spectacle.

And that only worked because Frank understood something structural about Las Vegas that outsiders missed.

The city was really two markets living side by side. The Strip was built for tourists: big resorts, premium prices, a high-effort experience designed for a once-in-a-while trip. But the locals—the workers, retirees, families, and service industry professionals—weren’t looking for a vacation. They wanted entertainment they could fit into a normal Tuesday night. The Strip wasn’t built for them. The prices were wrong, the vibe was wrong, and even the parking felt like a tax.

Frank built for the people who were already there. And then Las Vegas did what Las Vegas does: it grew.

The Demographic Goldmine

Fertitta’s timing turned out to be almost unfair. The Las Vegas metro area has grown from roughly 200,000 people around the era when he opened his first casino to nearly 3 million today. From 2000 to 2010 alone, the city’s population grew by just over 100,000 people, according to the Census Bureau’s Population Estimates Program. And the metro area kept climbing: about 2.899 million in 2023, and roughly 2.953 million in 2024.

Each new resident wasn’t a one-time customer. They were a potential regular—someone who might come back week after week, year after year. In a business where repeat behavior is everything, the lifetime value of a loyal local could be enormous.

Frank’s sons, Lorenzo and Frank Fertitta III, grew up in Las Vegas as this vision took shape. Their father had come from Texas with Victoria in 1960, worked his way through the Stardust and into management at places like the Tropicana, Sahara, and Circus Circus, and then made the bet that no one else wanted to make: build a casino designed for residents.

“The Casino” would later be renamed Bingo Palace, and eventually become Palace Station. But the more important thing was the idea behind it—a locals-first model that wasn’t just a quirky niche. It was the foundation for an entire empire.

The stage was set for one of the great family business stories in American gaming history.

III. Birth of Station Casinos: The Palace Station Breakthrough (1976–1990s)

The leap from a 5,000-square-foot roadside gambling hall to the foundation of a casino empire didn’t happen all at once. It happened the way most durable businesses are actually built: one smart, practical iteration at a time.

A year after opening, Frank Fertitta Jr. added bingo and renamed The Casino to the Bingo Palace. That move was quietly genius. Bingo brought in a different kind of customer—often older locals, many on fixed incomes, who weren’t just there to gamble. They were there to socialize. They showed up during daytime hours when the casino would otherwise be dead. They stayed for lunch. They brought friends. And most importantly, they came back. Week after week, the Bingo Palace started to behave less like a tourist trap and more like what Fertitta intended all along: a neighborhood habit.

As business grew, the building grew with it. In 1983, Fertitta renamed the property again—this time to Palace Station—and continued expanding. By the time he eventually parted with the property, Palace Station had gone through thirteen different expansions.

Thirteen expansions is the point. Instead of making one huge bet on a single grand opening, Fertitta kept scaling up as demand proved itself. The banking environment of the 1980s made that kind of step-by-step growth possible, and he took full advantage—financing expansion after expansion in a way that looked more like disciplined compounding than flashy Strip-style ambition.

The property names changed, but the underlying playbook didn’t: build for locals, make it easy, make it friendly, and keep earning the right to grow.

The same was true inside the business. As Palace Station expanded, Frank Jr.’s sons, Frank Fertitta III and Lorenzo Fertitta, moved into leadership roles and began learning how to run the machine.

The Second Generation Takes the Helm

Frank Fertitta III moved into senior management in 1985, when he became General Manager of Palace Station. A year later, he was elected a director of STN and was appointed Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer.

Family businesses often break at exactly this moment—when the founder steps back and the next generation steps in. The Fertittas made the transition work because it wasn’t a handoff; it was an apprenticeship. Frank III learned the business the same way his father did: by understanding how the casino actually ran, hour by hour, customer by customer.

In 1993, the elder Fertitta retired from the casino company, while staying active in other family businesses. That same year, his sons took the next big step.

The 1993 IPO and Expansion

In 1993, the company went public as Station Casinos. The stock began trading on May 25, 1993. Frank Jr. remained chairman but retired that year, and control passed to family members, including Frank Fertitta III, who became chairman, president, and chief executive officer.

The IPO mattered because it opened the door to something locals casinos hadn’t historically had: real growth capital. Station could now raise money in the public markets to replicate what worked—not by building mega-resorts for visitors, but by planting flags in the suburbs where Las Vegas was spreading. The strategy was straightforward: identify growing corridors, get the land, and build properties designed around the rhythms of local life.

The first big proof point was Boulder Station, which opened in 1994.

Then things got a little messy, in a very Fertitta-family way. After leaving the company, Frank Fertitta Jr. privately financed and began construction on a separate hotel-casino project: Texas Station, located in North Las Vegas on Rancho Drive. Station shareholders objected to him branching into gaming on his own, and the result was classic Station pragmatism—the company purchased the Texas shortly before its opening and the property opened in 1995. Frank Jr. sold it to Station Casinos at cost.

With Texas Station folded in, Station kept moving. Sunset Station opened in Henderson in 1997. Green Valley Ranch followed in 2001, developed in partnership with American Nevada Corporation.

Property by property, the formula kept getting reinforced. These weren’t Strip resorts built around a once-in-a-lifetime vacation. They were designed for frequency: convenient locations, easy parking, approachable food, and amenities locals actually used. Station wasn’t trying to win Vegas. It was trying to win Tuesday night.

And it was working. Not because the concept was flashy, but because it was repeatable—and because the Fertittas were executing it with focus.

For anyone watching from the outside, the lesson from this era is simple: Station Casinos didn’t beat the Strip operators at their own game. It built a different game, understood its customer better than anyone else, and expanded by doing the same thing—over and over—just a little better each time.

IV. The Golden Age: Aggressive Expansion & Market Domination (Late 1990s–2007)

By the turn of the millennium, Station Casinos had done more than prove the locals-casino thesis. It had turned it into a repeatable machine. And once you have a machine that works, there’s a question that always follows:

How big can this get?

Station’s answer was to press the accelerator—hard. It wasn’t just about building new neighborhood anchors anymore. It was also about buying them. In 2000, Station purchased Santa Fe. In 2001, it added Fiesta and Reserve. The strategy started to look less like expansion and more like consolidation: pull more of the locals market under one roof, then link it together.

Because every acquired property didn’t just bring in gaming floors and dining. It brought in something even more valuable: a ready-made base of regulars. Those customer databases could be folded into Station’s loyalty ecosystem, making each new acquisition immediately more powerful as part of a larger network.

Red Rock Resort: The Crown Jewel

The boldest swing of this era wasn’t an acquisition, though. It was a statement.

In July 2002, Station Casinos struck a deal with the Howard Hughes Corporation for an option on a 73-acre site in Summerlin, at the southeast corner of the Las Vegas Beltway and West Charleston Boulevard. Station announced plans that same month for a new hotel-casino—unnamed at the time—on that land. The company had until October 2002 to buy the site for $65 million, expected to complete the purchase by June 2003, and planned to begin construction in late 2003 or early 2004.

This was slated to be Station’s largest and most expensive resort. And the point wasn’t simply to build bigger. Red Rock was designed to expand what “locals casino” could mean.

It wasn’t meant to be just another convenient place to play slots and grab dinner. It was built to be premium—almost destination-quality—without abandoning the locals customer who made Station’s model work in the first place.

Frank Fertitta III and Lorenzo Fertitta made choices that signaled exactly what they were trying to do. They opted for chandeliers inspired by older Las Vegas resorts like the Desert Inn and the Sands—an indulgence that cost over $6 million. The resort’s scale matched the ambition: a casino spanning 118,308 square feet and a 796-room hotel. The design leaned modern with desert-themed influence, using blown glass, polished sandstone, and even 5,400 square feet of multicolored onyx imported from India and Italy.

When Station opened Red Rock Resort in 2006, it represented a very specific bet: that locals would pay for quality. That the same residents who loved Station for value and familiarity would also, at least some of the time, want something aspirational closer to home.

The UFC Parallel Universe

At the exact same moment Station was building its crown jewel, the Fertitta brothers were also making an investment that, in hindsight, would become legendary—and had nothing to do with casinos.

In 2001, Lorenzo and Frank III formed Zuffa, LLC to buy the assets of the Ultimate Fighting Championship from Semaphore Entertainment Group for $2 million. Lorenzo became chairman and CEO, and the brothers brought in their childhood friend Dana White as president. The UFC was in rough shape—nearly bankrupt, banned in most states, and widely dismissed as a fringe spectacle. Lorenzo later said it was “literally going out of business” when they bought it.

The Fertittas approached it the way they approached everything: with operations first. They professionalized the business, worked state by state to get MMA sanctioned, and focused on building something sustainable rather than chasing quick cash. Alongside Dana White, they helped transform the UFC’s image from a political punching bag into a legitimate sport, expanded internationally, and pushed hard to build a roster of stars.

Zuffa ran the UFC until August 2016, when it was sold for $4 billion. From a $2 million purchase price, that outcome became the kind of return people talk about for the rest of their careers.

But in the mid-2000s, the key point wasn’t the eventual payday. It was the pattern: the Fertittas were comfortable buying what others had written off—and then grinding it into something formidable through discipline and persistence.

Peak Confidence

By 2006 and 2007, Station looked untouchable. Las Vegas was booming. The locals market was thriving alongside explosive population growth. Red Rock was earning raves. The properties were throwing off cash. The stock was trading at all-time highs.

And that’s when the Fertittas made a fateful decision.

V. The Financial Crisis & Bankruptcy: A Near-Death Experience (2008–2011)

The fateful decision came into focus on December 4, 2006. Fertitta Colony Partners—a partnership between Frank Fertitta III, Lorenzo Fertitta, and Colony Capital—made a highly leveraged offer to buy all outstanding Station Casinos shares for $82 per share and take the company private.

The ownership structure told you exactly what kind of deal this was. The Fertitta brothers, their sister Delise Sartini, and her husband Blake Sartini put up a combined $870.1 million for a 25% stake. Colony Capital contributed $2.6 billion for the remaining 75%. The buyout closed on November 7, 2007.

And then the ground gave way.

Station went private in a leveraged deal valued at $8.7 billion, with roughly $5.5 billion of debt layered onto the business. On paper, this was the classic “peak confidence” move: lock in a high valuation, keep control, and let the cash flows pay down the leverage.

In real life, it became a trap. As the recession hit, Station’s revenue started to fall at the exact moment its interest bill mattered most. Refinancing markets froze. Debt payments that had seemed manageable in a booming Las Vegas suddenly looked impossible. The deal even helped push the two Fertitta brothers onto Forbes’s billionaires list in 2008—right as the gaming economy was turning against them.

The Housing Collapse Hits Home

The 2008–2009 financial crisis hit Las Vegas harder than almost anywhere in America. The housing market that had powered the city’s growth collapsed. Home prices were cut by more than half. Unemployment surged past 14%. Construction stopped. Workers left.

For a Strip operator, that’s bad. For a locals operator, it’s existential.

Station’s entire model depended on the financial health of Las Vegas residents. And as one industry observer put it, Station “got ambitious with projects like Aliante, which had Strip-level standards and weren't really well-positioned for a market that started struggling. Taking on too much debt certainly didn't help, but the sustained downturn in the locals market is primarily to blame.”

The leverage that looked like a smart financial tool in 2007 became a vise in 2008. When Station filed, it listed $5.7 billion in assets against $6.5 billion in debt. It also disclosed hundreds of holders of unsecured and subordinate debt totaling $4.4 billion—much of it tied directly to the buyout that had closed less than two years earlier.

The Bankruptcy Battle

Station had hoped to negotiate something orderly with its lenders. Instead, it announced it couldn’t reach agreement on a prepackaged reorganization and filed regular Chapter 11 petitions in Reno.

What followed was not a quiet restructuring. Breakingviews.com called it a “bare-knuckle brawl.” Creditors alleged the proposed plan was essentially an inside job—too favorable to management and secured lenders. A rival bidder jumped in to try to disrupt the process.

Boyd Gaming, Station’s main locals competitor, smelled blood. In 2009, Boyd made a $950 million offer to acquire a significant portion of Station as the company neared bankruptcy. After Station rejected it, Boyd told state gaming regulators it wanted to bid $2.45 billion for all of Station. Station filed for Chapter 11 with $6.5 billion in debt, and the fight only escalated.

Unsecured creditors pushed for investigation and litigation around the take-private itself. One committee statement captured the core grievance: “The net result of the leveraged buyout (LBO) was that Station Casinos leveraged to the hilt four of its most valuable properties, leaving Station Casinos and its creditors questionable benefit in return, while insiders of the debtors benefited immensely.” In their view, “The facts surrounding the LBO… require close investigation by the committee.”

This wasn’t just a capital-structure problem anymore. It was a legitimacy problem. The Fertittas weren’t only trying to save a business—they were defending their family name against the suggestion that the deal had been engineered to protect insiders at everyone else’s expense.

Emerging From the Ashes

After nearly two years in Chapter 11, Station completed what lead debtor’s counsel Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy described as the biggest-ever in-court restructuring of a gaming company. The reorganization put the company’s casinos back under the Station umbrella—and back in the Fertitta family’s hands.

Station officially exited bankruptcy on June 17, 2011. The process knocked roughly $4 billion off the debt load. The Fertitta brothers agreed to invest nearly $200 million into the reassembled company and emerged owning 45% of the outstanding shares. The rest of the new equity was spread among major lenders and former bondholders, including Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan Chase, and other creditors.

Inside the company, the mood was equal parts relief and exhaustion. “It's been a long battle, but it's finally done. We are very excited,” COO Kevin Kelly said at the time. And then he underlined what bankruptcy really costs: distraction. “Being done means Station Casinos can get back to the things it does best ... without the distractions.”

The Fertittas had survived. They kept control. But they didn’t walk out untouched. The experience left scars—and it burned in a lesson that would shape everything that came next: in a cyclical business, a great operating model can still get wiped out by a bad capital structure.

VI. The Turnaround & Return to Public Markets (2011–2016)

The Station Casinos that came out of Chapter 11 in 2011 wasn’t trying to be a bigger version of its old self. It was trying to be a smarter one.

The pre-crisis era had been defined by ambition and leverage—years of expansion capped by a buyout that left the company buried under debt just as Las Vegas fell into a historic local housing and employment collapse. The reorganization reset the balance sheet and forced a new posture: protect liquidity, tighten operations, and squeeze more performance out of the properties they already owned.

That playbook fit the moment. The locals market didn’t rebound overnight, but it did come back. Population growth resumed at a slower pace. Employment stabilized. And instead of racing to build the next shiny thing, Station leaned into operational discipline—efficiency, infrastructure upgrades, and making every square foot work harder.

The results showed up in the numbers: Station reported 15 consecutive quarters of cash flow growth, and 2014 net revenue reached $1.29 billion—its highest level since 2008. Not a return to the old boom days, but a clear signal that the machine was running again.

And once the business was steady, the Fertittas could revisit a question they’d been living with since the bankruptcy: should this company be public again?

The 2016 IPO

On October 13, 2015, Station announced it would return to the stock market. The next spring, on April 26, 2016, Red Rock Resorts, Inc.—a new holding company owning a portion of Station Casinos—went public on the NASDAQ under the ticker RRR.

There hadn’t been any public market for the company’s Class A shares before the offering. The IPO priced at $19.50 per share, right in the middle of the marketed range. Red Rock raised $531.4 million by selling 27.25 million shares, hitting the window at a moment when the IPO market had only recently started thawing after months of volatility.

But the most important part of the IPO wasn’t the price. It was the control.

The company went out with a dual-class structure. Class A shares carried one vote each. Class B shares carried ten votes for certain existing owners, and affiliates of Frank Fertitta III and Lorenzo Fertitta held the overwhelming majority of those high-vote shares. The message was unmistakable: public investors could buy into the economics, but the Fertittas weren’t giving up the steering wheel.

Some investors hated that. Others viewed it as the point—if you believed in the Fertittas as operators, you wanted them in control. Either way, it was a design clearly informed by the scars of the last cycle.

The UFC Windfall

Then, just months after Red Rock was back on the public markets, the Fertitta brothers closed the loop on the other bet that defined their careers.

In July 2016, Zuffa, LLC announced the sale of the UFC to WME-IMG—backed by Silver Lake Partners and KKR—in a deal estimated at about $4 billion. Lorenzo Fertitta stepped down as CEO upon completion.

The contrast was almost absurd: they had bought the UFC for $2 million and sold it about fifteen years later for roughly $3.77 billion. Reports at the time called it the most expensive transaction in sports history, and noted that the price was roughly seven times the UFC’s gross revenue.

Whatever you think about the exact multiple, the takeaway is simple: the UFC went from a distressed, politically embattled sideshow to a global sports property—and the Fertittas turned a small, risky purchase into a generational outcome.

That windfall mattered beyond bragging rights. It gave the family massive personal liquidity outside the casino business. It de-risked their fortunes. And it meant that when the next opportunity—or the next crisis—arrived in Las Vegas, they wouldn’t be walking into it with their backs against the wall.

VII. Modern Era: Expansion, Digital, and COVID Shock (2016–2020)

After the IPO, Red Rock Resorts settled into a familiar Fertitta rhythm: grow, but be choosy. Invest in the properties you already own. Allocate capital like the last cycle could always happen again.

Then came a big swing that didn’t fit the usual locals playbook.

In 2016, Station Casinos bought the Palms Casino Resort for $313 million. Not long after, the company poured more than $600 million into renovations. It was a bet on a different kind of customer and a different kind of property—less neighborhood habit, more Strip-adjacent energy.

It didn’t work out that way.

The COVID-19 Shock

And then, just as the company was digesting that investment, the world shut down.

On March 17, 2020, the Governor of Nevada ordered all nonessential businesses, including casinos, to close to slow the spread of COVID-19. The Graton Casino Resort, which the company manages, closed the same day. What began as a planned thirty-day shutdown stretched to seventy-nine days.

On June 4, 2020, Red Rock reopened Red Rock, Green Valley Ranch, Santa Fe Station, Boulder Station, Palace Station, and Sunset Station, along with its Wildfire properties.

Those seventy-nine days were brutal in the purest way possible: revenue basically went to zero while many costs kept running. Even after reopening, results were still weighed down by reduced travel, lower occupancy, and lower average daily rates, plus the fact that four properties remained closed.

For the full year, net revenues fell to $1.2 billion in 2020, down from $1.9 billion in 2019. The company reported a net loss of $174.5 million in 2020, compared to a net loss of $6.7 million in 2019. Adjusted EBITDA declined to $368.5 million in 2020, from $509.0 million the year before.

The Surprising Recovery

Here’s the twist: once the doors reopened, the locals model snapped back faster than almost anyone expected.

From June 4 through June 30, 2020, Red Rock’s Las Vegas properties showed strong post-reopening performance. Compared to the same stretch the prior year, net revenues were down 23.3%—but Adjusted EBITDA rose 46.8%, and Adjusted EBITDA margin jumped to 45.9%, the highest June EBITDA margin the company had ever posted. Management attributed the performance largely to a streamlined cost structure.

And the locals advantage showed up exactly where you’d expect. These customers didn’t have to book flights. They were already in town. After months cooped up, there was real pent-up demand for entertainment, and stimulus checks added a level of spending power nobody could have modeled in advance.

If the Great Financial Crisis proved how vulnerable a locals operator could be when locals are getting crushed, COVID proved the flip side: when travel disappears, a business built around residents can be the one that recovers first.

Strategic Portfolio Rationalization

COVID also forced a hard, clarifying question: which properties still mattered to the future of the company?

Texas Station, Fiesta Rancho, and Fiesta Henderson were closed in 2020 and never reopened. In 2022, Station announced it would demolish them and sell the land to help finance future projects. Analysts viewed the demolition as defensive—removing gaming-entitled sites that rivals might otherwise acquire and reopen. Station also announced in 2022 that it would close and demolish its Wild Wild West Gambling Hall & Hotel.

This was a defining move. Rather than limp underperformers back to life, Red Rock chose permanence: tear them down, take capacity out of the market, and keep those locations from becoming someone else’s comeback story.

And then there was the Palms.

Red Rock announced a definitive agreement between its subsidiary Station Casinos LLC and a subsidiary of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians to sell the Palms Casino Resort for $650 million in cash, subject to customary adjustments.

Yes, the sale price was well above the original $313 million purchase price. But once you include the massive renovation spend, the company didn’t come close to getting its full capital back. Put simply: Palms was a painful lesson.

The sale was also a clean admission that the Strip-adjacent experiment hadn’t delivered. And it freed up focus and capital for what the Fertittas have always done best: doubling down on the locals core, including a project that had been on the drawing board for nearly two decades.

VIII. Recent Inflection Points & Strategic Moves (2020–2024)

Durango Casino Resort: A New Era

If the Palms sale was Red Rock clearing the deck, Durango was the company placing its next big bet.

Durango opened on December 5, 2023—about two weeks later than planned. Some parts of the resort simply weren’t ready in time for proper staff training, so management chose to wait rather than force a rushed opening. And in Las Vegas, Durango mattered for another reason: it was the first ground-up Station hotel-casino since Aliante Station opened in 2008.

After fifteen years on the sidelines, Station Casinos was back in the development game, and this might have been its most strategically important build yet.

The 15-story, $780 million property sits on a 71-acre plot that Station had actually acquired way back in 2000. That’s the land-bank strategy in action: buy early, hold patiently, and build when the neighborhood catches up. Station purchased the site from developer Jim Rhodes in 2000, and by 2004 it was already talking about a hotel-casino there—then known as Durango Station. It took decades, but the vision didn’t go away.

Station broke ground in March 2022. By the time it opened, Durango looked like the next evolution of what “locals casino” can be: a premium property designed for residents who want something elevated without having to trek to the Strip.

The resort includes a roughly 83,000-square-foot casino, more than 200 guestrooms and suites, meeting space, 15 restaurants, and a pool. It also has free parking and sits right along I-215. And critically, it’s positioned as the only casino resort within a five-mile radius—exactly the kind of geographic whitespace Station has hunted for since the beginning.

2024 Financial Performance

By 2024, the broader Red Rock machine was throwing off real momentum again—and Durango was a big reason why.

For the fourth quarter of 2024, net revenues were $495.7 million, up from $462.7 million in the same quarter of 2023. Net income was $87.7 million, down from $108.9 million a year earlier. Adjusted EBITDA was $202.4 million, slightly higher than the prior year’s $201.3 million.

For the full year, net revenues from Las Vegas operations reached $1.93 billion, up from $1.71 billion in 2023. Adjusted EBITDA from Las Vegas operations was $879.4 million, up from $818.8 million the year before. As of December 31, 2024, the company had $164.4 million in cash and cash equivalents and $3.4 billion in total debt outstanding.

Durango’s ramp was a major driver of the year-over-year lift. Management highlighted that, given its premium margin profile relative to the rest of the portfolio, Durango’s annual net revenue for 2024 was estimated at approximately $340 million.

Competitive Dynamics and Future Development

One of Red Rock’s most durable advantages is that the locals market is hard to invade. Barriers to entry are high, and Nevada law (SB 208) significantly limits casino development outside the Strip. And even if you could build, there’s the practical problem: where?

Red Rock has been buying up that “where” for years. The company owns many of the major off-Strip gaming development sites across the Las Vegas Valley, and it has continued adding to that land position. Station purchased land at Losee Road and the 215 Beltway in North Las Vegas, and also near Cactus Road and Las Vegas Boulevard, for potential future gaming sites. With those transactions, the company said its strategic landholdings totaled more than 522 acres—land it views as the foundation for future growth.

And while the core strategy is still locals-first, the company has also been widening its footprint in smaller, higher-leverage ways. In 2025, Station began operating the sportsbook at the Treasure Island Hotel and Casino, marking its debut presence on the Las Vegas Strip. It also began operating sportsbooks at two other properties—CasaBlanca Resort and the Virgin River—in nearby Mesquite, Nevada.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand Red Rock Resorts, you have to understand why the locals casino model works—and why, in many ways, it produces cleaner economics than the Strip.

Strip casinos live and die by big, expensive, unpredictable trips. A locals casino wins by becoming part of someone’s routine.

The Customer Economics

Red Rock’s edge starts with frequency. About 75% of local carded slot revenue comes from guests who visit four or more times per month. That’s not a marketing fun fact. That’s the business.

A tourist might come to Las Vegas once every few years, splurge, and disappear. A local might drop in multiple times a week. Each visit might be smaller, but the relationship is compounding. Over time, the lifetime value of a true regular can outweigh the value of a once-in-a-blue-moon visitor—because the visits don’t stop.

That repeat behavior also does something operators crave: it makes demand more predictable. When your customer base is built around habit, the business becomes less about capturing a single perfect weekend and more about showing up, day after day, with the right experience.

The Loyalty Program Moat

Station’s habit-forming engine is its loyalty program.

In April 1999, the company launched Boarding Pass, linking its properties together so customers weren’t earning rewards at one casino in isolation—they were earning them across an entire network. Over time, that evolved into Station Casinos Boarding Pass ‘My Rewards,’ a full ecosystem that rewards guests not just for gaming like slots, video poker, keno, bingo, and poker, or race & sports wagers, but also for the things locals actually do: restaurants and bars, concerts, hotel stays, catering, bowling, ice skating, spa visits, and more.

Today, the program has millions of active members, which gives Station two powerful advantages at the same time.

First: stickiness. Status, points, comps, free play, dining discounts, preferred parking—those perks add up. And once a customer has earned them, switching to a competitor isn’t frictionless. It’s like walking away from value you already banked.

Second: data. Every swipe tells Station what customers like, when they show up, and how they behave across the portfolio. That makes marketing less like blanket discounting and more like precision—getting the right offer to the right person at the right time.

Operating Leverage

Then there’s the quiet superpower in the casino business: once the building is up, incremental demand can be very profitable.

In 2024, Red Rock’s Adjusted EBITDA margins typically landed in the mid-30s to around 40%. That’s the payoff of operating leverage. A busy slot floor doesn’t require a proportional increase in labor the way many service businesses do. Many costs—real estate, equipment, utilities—are largely fixed. So when volume rises, profitability can rise faster than revenue.

That’s also why the locals model is so attractive when it’s working: more trips from the same customer base can translate into outsized incremental profits.

Real Estate as Competitive Advantage

Finally, there’s the part of the model that’s hardest to copy: the land.

Station has accumulated significant undeveloped parcels in key growth areas around the Las Vegas Valley, including gaming-entitled sites—locations where major casinos can be built without needing to fight the same uphill entitlement battles again. And there are only so many of those sites to go around.

That land does two things at once. It’s offensive optionality: the ability to build when the market is ready. And it’s defensive: those are sites competitors can’t get.

In a city where “where” is often the difference between a winning property and a mediocre one, Station’s land bank isn’t just a pipeline. It’s part of the moat.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: LOW (High Barriers) If you want to break into the Las Vegas locals market in a meaningful way, you run into three walls fast: regulation, land, and capital. Gaming licenses come with intense scrutiny. Gaming-entitled land is scarce—and much of it is already spoken for by existing operators. Nevada law (SB 208) also limits casino development outside the Strip. And even if you clear those hurdles, you still have to write a very large check. Durango’s $780 million price tag is a reminder that new, serious competition isn’t something that pops up overnight.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW Suppliers don’t hold much leverage here. Slot machines come from multiple major manufacturers. Table game equipment is widely available. Food and beverage inputs are basically commodities. The big swing factor is labor—and while the Culinary Workers Union represents a large share of Las Vegas resort workers and has had a long-running feud with Station, Station has largely maintained a non-union workforce, which has historically given it flexibility and cost advantages.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE Locals have options. They can pick among multiple casinos and entertainment choices, and they do. But in a locals business, two forces reduce that power: convenience and habit. Proximity to home matters, and loyalty programs make “switching” feel like walking away from value. The fact that 75% of local carded slot revenue comes from guests who visit four or more times per month tells you what’s really going on—these aren’t occasional shoppers; they’re regulars with routines and preferred properties.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE to HIGH The substitute set is real. Online gaming could be a direct alternative, though Nevada has been slow to legalize online casino gambling. Sports betting is widely available through mobile apps. And of course, casinos compete with every other claim on discretionary spending: movies, dining, live sports, and everything else locals can do with a night out. That said, casinos still have a stubborn advantage that’s hard to digitize: the social, physical experience—getting out of the house, seeing familiar staff, and being in a live environment with other players.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE Competition is serious, but it’s not a free-for-all. Boyd holds about 25% market share in what is often described as a duopoly with Red Rock (around 40%). The rivalry is tempered by geography: the two companies have somewhat differentiated footprints across the valley, which reduces direct property-to-property warfare. Beyond them, there are other players—privately held locals properties like Rampart and Palms, plus smaller-format competition like tavern-style casinos, including PT’s, operated by Golden Entertainment.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: YES Scale shows up in the simplest places: marketing efficiency and overhead. Multiple properties let Red Rock run one loyalty ecosystem across the valley and spread corporate costs across a larger revenue base. Bigger scale also improves purchasing power for slots, food, and operating supplies.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE Boarding Pass becomes more valuable as more properties are connected to it. Members can earn and redeem across a broader set of casinos, restaurants, and amenities, which increases engagement. But the network effect is bounded by geography: it’s powerful inside Las Vegas, and far less relevant outside it.

3. Counter-Positioning: HISTORICAL The original move—build for locals while everyone else built for tourists—was textbook counter-positioning. Strip operators couldn’t easily pivot to serve both markets without muddying their brand and economics. Over time, as the locals segment proved itself and matured, that advantage naturally narrowed as competitors entered. But it’s how Station created the category in the first place.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE Points, tier status, comp offers, and relationships with hosts all create friction. Convenience does too—having your “home” casino close by becomes a habit. None of this is unbreakable, but it’s enough to keep many customers anchored unless a competitor offers a truly compelling reason to move.

5. Branding: MODERATE Station Casinos is a known name in Las Vegas, and certain properties—like Red Rock and Green Valley Ranch—carry strong local associations with quality. But this is not national luxury branding. It’s a community and convenience brand: trusted, familiar, and close to home.

6. Cornered Resource: YES This is the big one. Red Rock controls scarce gaming-entitled sites—land where major casinos can be built without needing a fresh set of approvals. In Las Vegas, there are only so many of these locations, and they’re incredibly hard to replicate. Combine that with gaming licenses and decades of locals-focused know-how, and you get a set of advantages competitors can’t simply buy off the shelf.

7. Process Power: YES Running a locals casino well is a craft. It involves managing the casino floor to optimize game mix and hold, pricing hotel rooms intelligently, and relentlessly controlling costs—especially labor and utilities. But the deeper process advantage is cultural and behavioral: understanding what repeat customers want, marketing without over-discounting, and training staff for a business built on familiarity. Those capabilities take years to build and are hard for outsiders to fully see, much less copy.

Conclusion: Red Rock’s moat is anchored in Cornered Resources (especially land and licenses) and reinforced by Process Power (locals operational excellence), with Scale Economies and modest Network Effects layered on top. The most credible long-term pressure point is digital disruption: as online gaming and mobile sports betting expand, the “convenience advantage” of a nearby physical casino could weaken.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Analysis

The Bull Case

Demographic Tailwinds Continue

Nevada has enjoyed favorable demographic trends, with population up roughly 40% from 2004 to 2024. Over the last two decades, Las Vegas has added about 4.3 new residents per hour, every day. In Red Rock’s world, that’s not an abstract stat—it’s a steady stream of potential regulars. As long as Las Vegas keeps pulling in movers from higher-cost states like California, the locals customer base keeps getting deeper.

Dominant Position with High Barriers

Red Rock sits at about 40% market share in what many describe as a duopoly. It also controls many of the valley’s gaming-entitled development sites—the scarce “where” that matters most in this business. Add in licensing and regulatory friction, and the locals casino market starts to look less like a free market and more like a fortress. This isn’t a category where a giant outside player can casually decide to show up and take share.

Margin Expansion Potential

Coming out of COVID, Red Rock ran leaner—tighter staffing, better use of technology, and the permanent removal of underperforming capacity through closures and demolitions. In 2024, Adjusted EBITDA margins typically sat in the mid-30s to around 40%. If those operational changes prove structural rather than temporary, the company can keep generating more profit from the same footprint by driving higher revenue per square foot.

Family Alignment

The Fertitta Family Entities held about 90% of combined voting power as of the 2025 record date. That concentration cuts both ways, but from a pure alignment standpoint, it means the controlling owners’ wealth rises and falls with the business. And they’ve already shown two things investors care about: they can operate through cycles, and they’ve lived through what happens when leverage and macro conditions collide.

Development Optionality

With 19 properties across the Las Vegas Valley and about 461 acres of land available for future development, Red Rock has real option value embedded in the portfolio. The company can wait, pick its spots, and build when demand is there—rather than chasing growth just to grow.

The Bear Case

Leverage Remains Elevated

At the end of the fourth quarter, total debt outstanding was $3.4 billion. This is the same company that nearly got wiped out by leverage in the last major downturn, and it still carries meaningful debt. If Las Vegas takes a hard recessionary hit, the balance sheet is the first place investors will look.

Geographic Concentration

Over the last twelve months, the Las Vegas Operations segment generated $1.93 billion of revenue—about 99% of total revenue. That focus is part of the locals advantage, but it’s also a single-point-of-failure risk. If the Las Vegas economy gets rocked—by a recession, a major employer leaving, or another local shock—Red Rock doesn’t have another region to hide in.

Digital Disruption Threat

Mobile sports betting and online gaming keep getting better substitutes. If Nevada ever legalizes online casino gaming, the most dangerous shift would be behavioral: younger customers choosing to gamble from the couch instead of driving to a property. The locals model is built on convenience, and digital can be more convenient than a parking lot.

Growth Deceleration

UNLV’s 2024–2060 population forecast has Clark County growth dipping below 2% in 2027 and below 1% by 2039. By 2060, the county is projected to add roughly 15,000 residents per year, or about 0.5% growth. If that plays out, the demographic tailwind that powered the entire locals category becomes a lighter breeze—which means future growth has to come more from share gains and wallet share, not simply a bigger city.

Governance Concerns

Red Rock is family-controlled, and the dual-class structure concentrates power. Class B shares held by Fertitta Family Entities carry ten votes per share if specified thresholds are met, resulting in about 90% combined voting power as of the 2025 record date. Public shareholders have limited influence over strategy and oversight. And related-party transactions can heighten that discomfort—for example, Red Rock Resorts agreed to pay $120 million to the mother of its controlling shareholders for land under two of its resorts.

Key Metrics to Track

For investors following Red Rock Resorts, the most critical KPIs are:

-

Same-Store EBITDA Growth — This captures organic performance without the noise of new properties. Consistent gains suggest strong operations and healthy demand; sustained declines can signal weakening customers or rising competitive pressure.

-

Net Debt to EBITDA Ratio — Given the company’s history, leverage discipline is non-negotiable. A steady path downward is reassuring. A move meaningfully higher is a warning flare.

XII. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Know Your Customer Deeply

Frank Fertitta Jr. won by taking a simple observation seriously: Las Vegas locals wanted something fundamentally different from tourists. He didn’t chase the Strip’s glamour or try to build the same product for everyone. He built for an underserved customer with a clear job to be done—an easy, familiar place to play, eat, and come back to. The broader lesson is portable: the niches that look “too small” to the giants are often exactly where a focused operator can build something enormous.

Location Is a Sustainable Advantage

In casinos, “where” isn’t a detail—it’s destiny. Station Casinos spent decades buying and holding gaming-entitled land before competitors could, and that created a moat you can’t replicate with clever marketing or a better app. Even in a digital world, physical location still matters, because convenience is the product. If your casino is on the way home, it’s competing against habit, not against advertising.

Family Control Can Be a Superpower

The dual-class structure that irritates some shareholders also explains a lot of the company’s long-term consistency. The Fertittas can think in decades instead of quarters, invest through cycles, and ignore short-term noise without constantly looking over their shoulder for activists. Concentrated control isn’t automatically good—but in the hands of proven operators with aligned incentives, it can be an advantage, not a liability.

Survive Near-Death Experiences

Station nearly died in 2009. Coming out of bankruptcy, the company was leaner, more disciplined, and far more realistic about what can go wrong in a cyclical business. The Fertittas learned the hard way that leverage can turn a great operating model into a bankruptcy case file. But there’s a strange upside to surviving an existential crisis: companies that live through one often build institutional antibodies—habits and reflexes that make the next shock less fatal.

Cyclicality Demands Respect

Gaming is discretionary spending, which means it gets hit when consumers get nervous. The locals market can be more resilient than the Strip, but it’s still tied to jobs, housing, and confidence. The implication is straightforward: your capital structure has to be built for the downside, not just optimized for the boom.

Counter-Positioning Works

Station didn’t beat the Strip operators by copying them. It won by serving a segment they weren’t built to serve. That’s counter-positioning at its best: finding a customer set the incumbents ignore, then building a business model around them that’s hard to imitate without breaking the incumbent’s own economics. The Fertittas repeated the pattern with the UFC too—buying a sport many considered “barbaric” and mainstream brands wouldn’t touch, then professionalizing it until it became unavoidable.

Operational Excellence Compounds

The locals casino model looks simple from the outside, which is exactly why it’s deceptive. Station’s edge comes from accumulated craft: how to market to regulars without giving away the store, how to train teams for repeat customers, how to tune game mix and floor layouts to local patterns. That kind of process power builds slowly—and once it’s built, it’s hard to catch. There are no shortcuts.

XIII. Epilogue & The Future

Red Rock Resorts headed into 2026 with the wind at its back. Wall Street, at least on balance, liked the setup: a group of analysts covered the stock, the consensus leaned “Buy,” and the average 12-month price target sat around the low $60s. Durango was still ramping toward full stride. The balance sheet was still meaningfully leveraged, but no longer looked like a dare. And, as always, the Fertitta family still had both hands on the wheel.

The Development Pipeline

The next chapter wasn’t just about running the existing portfolio better. It was also about where Red Rock could go from here.

The most concrete growth initiative on the board was North Fork in Central California. The project was expected to open in Q4 2026, with a gaming floor planned for thousands of slot machines and dozens of table games, plus multiple dining options. Construction was underway, and the company secured $750 million in financing in April.

Back home in Las Vegas, growth didn’t have to mean new towers. Red Rock continued putting capital into the properties it already owned, including renovations at Sunset Station and Green Valley Ranch—projects designed to keep the product fresh, protect share, and give regulars a reason to keep coming back.

And then there’s the hidden weapon that has defined Station for decades: the land bank. The Peninsula project and other held sites represented years of potential organic development—optionality the company could time to the city’s growth, without needing to chase acquisitions.

Succession and the Fertitta Factor

One risk investors can’t model cleanly is succession.

Frank Fertitta III had led Station Casinos for more than three decades—first learning under his father, then running the business as chairman and CEO. Lorenzo served as vice chairman and focused heavily on other ventures. The next generation was starting to appear in the operating picture—Frank Fertitta IV, Vice President of Operations, was at the Durango opening—but even the best-run family businesses face a real test when leadership changes hands.

In a company where control and culture are intertwined, transitions matter.

The Digital Question

The largest strategic uncertainty hanging over the locals model is what happens as gambling keeps moving onto phones.

Red Rock operates STN Sports for mobile sports betting, but it has limited exposure to iGaming. If Nevada were to legalize online casino gambling, as more states have done, the company’s core edge—convenience—would face a new kind of competitor. A younger customer who grew up on smartphones may not view a drive and a parking lot as “easy” compared to playing from the couch.

The counterpoint is the one casino operators have always leaned on, and not without reason: the product isn’t just wagering. It’s the night out. The atmosphere, the familiarity, the energy, the interaction with dealers and other players—those things don’t port cleanly to an app.

The open question is how much of the business is truly “experience,” and how much is simply “access.”

A Uniquely American Story

The Station Casinos story endures because it’s hard not to see it as an American archetype.

A son of Italian immigrants arrives in Las Vegas with his wife and very little. He works his way up from bellman to dealer to pit boss to casino manager. He spots a customer everyone else ignores, builds a small casino in the desert, and creates an entire category in the process. His sons scale that idea into a public-company empire, get nearly wiped out by leverage and a brutal cycle, fight their way back through bankruptcy, and return to the public markets. And on the side, they make the kind of investment that sounds like a tall tale—buying the UFC for $2 million and selling it for about $4 billion.

It’s entrepreneurship and family control, risk and survival, humiliation and redemption. But above all, it’s the power of knowing your customer better than anyone else—and having the patience to keep executing while the rest of the industry chases whatever looks hottest this year.

For investors, Red Rock is a chance to own a slice of the Las Vegas locals market with an operator that has real advantages in land, scale, and process. The risks are not subtle—leverage, geographic concentration, digital disruption, and governance are all part of the package. The bet is that the same family that invented the locals-casino playbook can keep evolving it in whatever Las Vegas becomes next.

XIV. Further Reading

Top 10 Long-Form Links & Book References:

- Red Rock Resorts investor relations (10-Ks, proxy statements, earnings transcripts) — The primary source for financials, disclosures, and what management says in its own words

- Station Casinos bankruptcy court documents (2009-2011 filings) — The real record of how the restructuring unfolded, in all its messy detail

- "License to Steal" by Jeff German — A sharp, local investigative view into Las Vegas’s gaming world

- "Suburban Xanadu" by David G. Schwartz — A deeper, more academic look at how the locals-casino model developed

- Las Vegas housing and demographic data (UNLV Center for Business and Economic Research) — The best way to track the population and housing trends that drive the locals market

- Boyd Gaming investor materials — Useful for side-by-side comparisons with Station/Red Rock and broader locals-market context

- American Gaming Association industry reports — A good national-level view of gaming trends and regulation

- "The Odds" by Chad Millman — The story of sports betting in Las Vegas, and the culture around it

- UFC sale case studies — Helpful for understanding the Fertittas’ playbook outside casinos, and why the UFC bet worked

- Nevada Gaming Control Board regulatory filings and market data — The official source for gaming revenue, licensing, and regulatory framework

Academic Papers:

- "The Economics of Casino Taxation" (UNLV Gaming Research)

- "Locals vs. Tourist Gaming Markets: A Comparative Analysis"

Podcasts/Interviews:

- Frank Fertitta III interviews on gaming industry strategy

- Station Casinos employee forums for cultural insights

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music