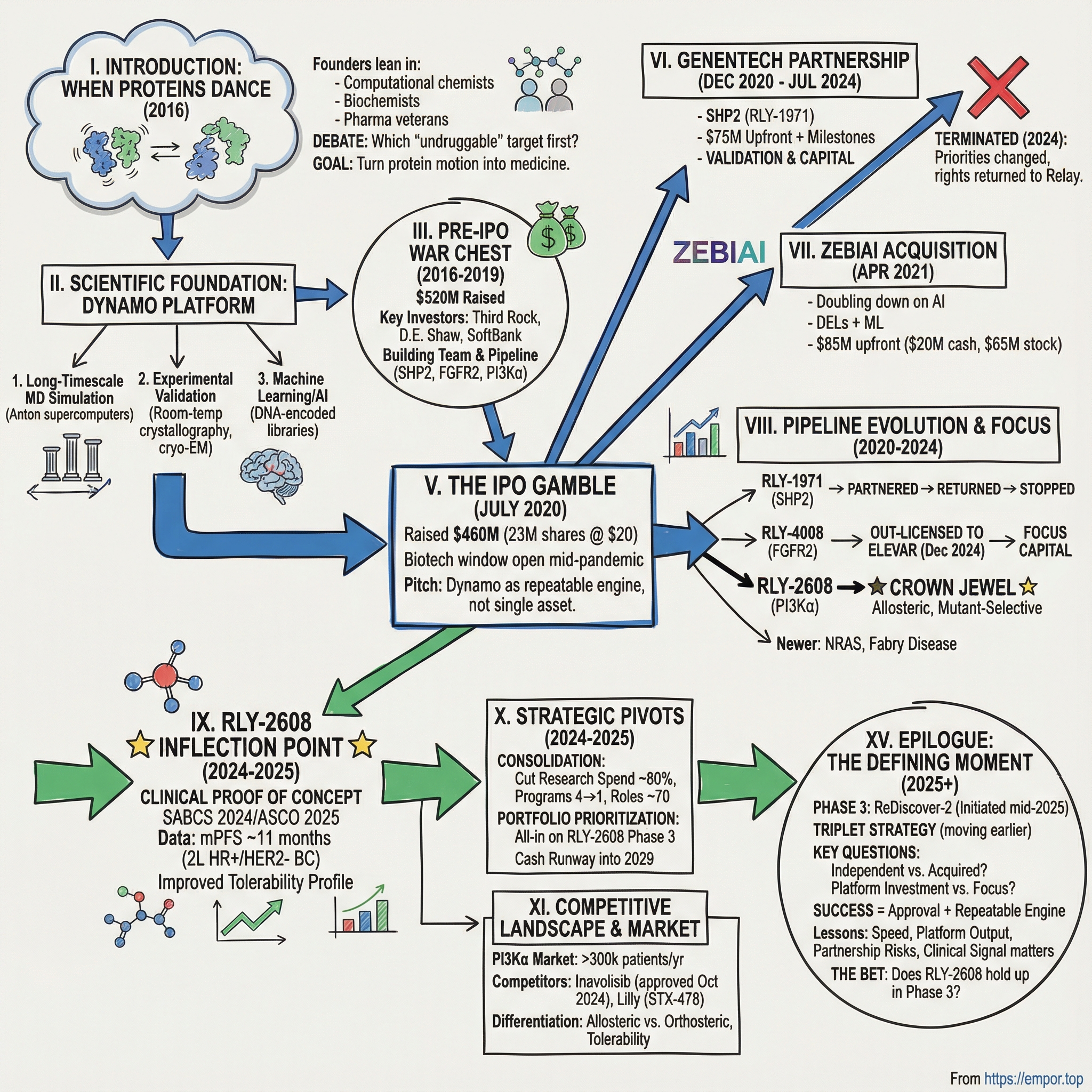

Relay Therapeutics: The Story of Turning Protein Motion Into Medicine

I. Introduction: When Proteins Dance

Picture a conference room in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 2016. Half a dozen scientists—computational chemists, biochemists, pharmaceutical veterans—lean in over a table, and to an outsider it might sound like an argument. But it’s the good kind: sharp, energized, collaborative. Hands cut through the air toward molecular diagrams on glowing screens. The proteins on display aren’t frozen structures; they’re moving—twisting, flexing, breathing—more like living machines than marble statues.

In one corner sits a former hedge fund titan turned computational biochemist. In another, a German scientist who once captained her country’s national basketball team before pivoting to protein dynamics. And at the center is a drug-hunting veteran who helped bring landmark HIV medicines into the world. The debate isn’t whether this approach can work. It’s which supposedly “undruggable” target they should go after first.

A century after X-ray crystallography began turning biology into crisp structural snapshots, this group wanted something different: not a photograph, but a film. They believed that if you could model proteins the way they actually behave—constantly shifting between shapes—you could find new footholds for drugs, including binding pockets that appear only in motion. That conviction became Relay Therapeutics, founded to turn protein movement into a repeatable engine for medicine.

The question that has powered Relay from day one sounds simple and almost naïve: Can computation and AI finally crack targets that have resisted pharmaceutical intervention for decades? Relay’s story is what happens when you try to answer that question in the real world—where elegant theory meets messy biology, and platform ambition collides with the unforgiving timelines of clinical trials.

Relay went public on July 16, 2020, in the middle of a pandemic, selling 23 million shares at $20 each and raising $460 million in gross proceeds before expenses. It was one of biotech’s biggest IPOs that year. Investors weren’t just buying a single drug candidate—they were buying the pitch that protein motion could become an advantage you could compound, again and again, across a pipeline.

Now, at the end of 2025, Relay is staring down the moment that will define it. Its lead program, zovegalisib (RLY-2608), is in a pivotal Phase 3 trial in breast cancer: ReDiscover-2, focused on patients previously treated with CDK4/6 inhibitors. The next stretch—measured not in quarters, but in readouts—will determine whether Relay’s bet becomes a breakthrough that validates a new model of drug discovery, or a reminder that platforms are only as valuable as the medicines they produce.

This is the story of Relay Therapeutics: the science behind its approach, the founders who assembled the company, the partnerships that validated—and later walked away—its work, the clinical results that rebuilt conviction, and the competitive landscape waiting on the other side. Along the way are lessons about building at the intersection of computation and biology, why drug discovery platforms are so seductive (and so expensive), and what it looks like when a platform company grows up and has to win on one pivotal trial.

II. The Scientific Foundation: A Century of Snapshots

Relay’s story starts with a basic mismatch that drug hunters have wrestled with for decades: proteins run the body, but they don’t make themselves easy to drug.

For more than a century, scientists have known proteins are the molecular machines behind virtually every biological process. The hard part has never been appreciating their importance. It’s been seeing them clearly enough—and in the right way—to design molecules that can consistently control them.

In 1915, X-ray crystallography helped earn that year’s Nobel Prize in Physics. By the 1990s, it had become a workhorse of pharma, letting researchers solve protein structures at atomic resolution. It was a revolution: at last, you could look at a protein and say, “That’s what it is.”

But crystallography comes with a built-in trap. It gives you a snapshot: one still frame of something that, in the cell, never stops moving.

Proteins flex. They twist. They breathe. They shift among shapes that can change what the surface looks like and whether a drug can bind at all. A pocket that seems sealed shut in a crystal structure might open up only occasionally—just long enough for a small molecule to slip in. If you’re designing drugs using still photos, you can end up optimizing for a conformation that isn’t the one biology cares about most. Or worse: you miss the best pocket entirely because it only exists in motion.

That’s the gap Relay set out to close.

The Founding Insight

Relay Therapeutics formed around the belief that the next leap in drug discovery wouldn’t come from sharper snapshots. It would come from turning those snapshots into movies—and making those movies practical to use, over and over again, to build medicines.

That required two things to get good at the same time: computation that could simulate meaningful protein motion, and experimental methods that could validate what the simulations predicted. The enabling breakthrough was progress in molecular dynamics simulation. For a long time, standard computing could simulate protein motion on nanosecond timescales—real motion, but often too brief to capture the larger conformational changes that matter for function and drug binding, which can play out over microseconds or milliseconds.

Relay’s wager was that those longer timescales were no longer out of reach. With purpose-built compute—most notably the specialized supercomputers developed at D. E. Shaw Research—and a growing toolkit for drug hunting, the company believed it could systematically find and exploit the transient, motion-driven opportunities that traditional structure-based approaches missed.

The Dream Team Assembles

That idea was ambitious enough that it needed founders who could credibly span both worlds: hard-core computation and hard-core drug development. Relay Therapeutics was founded in 2016 by David E. Shaw, Dorothee Kern, Mark Murcko, and Matthew Jacobson.

David E. Shaw was an unlikely figure to show up at the start of a biotech company. Shaw is an American billionaire scientist and former hedge fund manager who founded D. E. Shaw & Co., once described by Fortune as “the most intriguing and mysterious force on Wall Street.” Fortune even dubbed him “King Quant” for pioneering high-speed quantitative trading.

But Shaw’s second act wasn’t finance—it was science. In 2001, he turned to full-time research in computational biochemistry, focusing on molecular dynamics simulations of proteins. He became chief scientist of D. E. Shaw Research, which built specialized supercomputers—Anton machines—engineered specifically to simulate protein motion at timescales previously out of reach. His scientific credibility was formal, too: he was elected to the National Academy of Engineering in 2012 and the National Academy of Sciences in 2014.

Dr. Dorothee Kern brought the deep, academic foundation in protein motion that made the whole concept feel less like a clever theory and more like a real discipline. Kern, born in 1966, is a professor of Biochemistry at Brandeis University—and her path into science is as memorable as her work. She played for the East German national basketball team as a teenager, served as captain, and played point guard. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, she shifted her focus entirely to biochemistry and became one of the world’s leading experts in protein dynamics.

When Relay was founded in 2016, Kern began applying her protein motion research to cancer biology. Along with her research team at Brandeis, she published work using high-level biological computing and imaging to study evolutionary shifts in protein structure in proteins and enzymes commonly involved in cancer over roughly three million years of evolutionary history.

Dr. Mark Murcko was the operator and the proof point: someone who had already lived through the last wave of “computers will change drug discovery,” and actually delivered medicines. Murcko was an early leader in structure-based drug design and has directly contributed to nine marketed drugs spanning HIV, HCV, cystic fibrosis, and glaucoma. He served as chief technology officer and chair of the SAB at Vertex Pharmaceuticals, where he drove disruptive technologies across R&D. He’s a co-inventor of Incivek (telaprevir), and of two marketed HIV drugs, Agenerase (amprenavir) and Lexiva (fosamprenavir).

And he had a special historical connection to the Relay premise. Trusopt was the first marketed drug in pharmaceutical history to result from a structure-based drug design program. Murcko had helped define what “structure-based” meant. Now he was signing up to push it beyond static structure into dynamics.

Dr. Matthew Jacobson rounded out the founding group from the academic side of drug design and chemistry. He is a professor and Pharmaceutical Chemistry Department Chair at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

The Financing and Launch

Relay headquartered itself in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and launched in 2016 with $57 million in Series A financing from Third Rock Ventures and an affiliate of D. E. Shaw Research. Third Rock’s involvement mattered. This was one of the most respected healthcare venture firms in the business, known for company-building and for launching names like Agios Pharmaceuticals and Bluebird Bio.

Relay set an explicit mission: build a drug discovery pipeline centered on protein motion. The company aimed to fuse structural biology, biophysics, computation, chemistry, and biology into a single engine that could illuminate how proteins move—and how that motion regulates function—so drug design could be built around reality, not a frozen approximation.

The investor thesis was simple, and dangerously bold: if protein motion really was the missing layer in drug discovery, then Relay wouldn’t just have one shot. It could have an advantage across target after target. Not a single-product biotech, but a platform that could repeatedly generate new medicines—because it was finally designing against how proteins actually behave.

III. The Dynamo Platform: Understanding Molecular Motion

Relay’s entire thesis lives or dies on one idea: proteins don’t sit still. And Dynamo is the company’s attempt to turn that idea from an academic truth into an industrial machine for making drugs.

To see why Dynamo matters, it helps to start with the standard playbook. Traditional structure-based drug design usually begins with a single, exquisitely detailed picture—an X-ray crystallography structure or a cryo-EM model of a protein. From there, scientists hunt for pockets on the surface where a small molecule might bind, then iterate on chemistry to make that binder tighter, cleaner, and more drug-like. It’s a “shape match” approach: learn the lock, carve the key.

The catch is that proteins aren’t locks. They’re more like machines with joints, springs, and moving parts. The most important pockets can be fleeting—opening for a moment, then collapsing as the protein shifts into its next shape. If you only design against one frozen pose, you can end up optimizing for the wrong moment in the movie. Or you can miss the pocket entirely.

Dynamo is Relay’s system for finding those moments—and using them.

The Three Pillars of Dynamo

The Dynamo platform brings together experimental and computational methods to measure motion, model motion, and then exploit motion for drug design.

The first pillar is long-timescale molecular dynamics simulation. Many conventional simulations are short enough to capture vibration, but not long enough to capture meaningful rearrangements. Relay, leveraging deep computational resources—including its relationship with D.E. Shaw Research—pushes simulations into longer regimes where proteins start to reveal alternate conformations. At those timescales, things happen that snapshots can’t show: loops shift, domains reorient, and binding pockets that look nonexistent in a static structure can briefly appear. Allosteric sites—regions away from the active site that can still control function—start to show themselves in a way that feels less like luck and more like mapping.

The second pillar is experimental validation through room-temperature crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy. Traditional crystallography can trap proteins in a single pose; room-temperature approaches can preserve more natural flexibility. Cryo-EM, which earned the 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, helps visualize proteins in near-native states and capture multiple structural states. In Dynamo, these experiments don’t replace the simulations—they ground them, challenge them, and sharpen them into something you can actually build chemistry around.

The third pillar is machine learning, used to accelerate the search for chemical starting points and guide iteration. In particular, Dynamo incorporates DNA-encoded library approaches that let Relay sift through enormous chemical space efficiently and focus lab work on the most promising candidates.

The Metaphor That Matters

Relay’s management often explains Dynamo with a metaphor: “Traditional drug discovery is like looking at old black and white photos. Our approach enables us to visualize protein motion in HD movies.”

It’s a metaphor because it’s easy to remember. But it’s also surprisingly precise. If you tried to understand how a pitcher throws a curveball from one photograph, you’d miss the grip, the wrist snap, and the release angle—the mechanics that actually make the pitch work. Watching the motion is the difference between guessing and knowing.

Relay’s bet is that drug discovery works the same way.

Why This Matters for Drug Design

Motion-based design changes what’s even possible to target. Many proteins have resisted traditional drug discovery not because they’re impossible in principle, but because their most druggable shapes are temporary. The pocket is there—just not reliably, and not in the frame you happened to capture. By identifying and characterizing those transient conformations, Relay aims to design drugs that bind to states other approaches never truly see.

Dynamo’s most important proof point inside Relay is RLY-2608: described as the first known allosteric, pan-mutant, and isoform-selective PI3Kα inhibitor. To get there, Relay solved the full-length cryo-EM structure of PI3Kα, ran long time-scale molecular dynamics simulations to tease out conformational differences between wild-type and mutant PI3Kα, and used those insights to support the design of the molecule.

And that leads to the central tension in Relay’s story. For investors, Dynamo is simultaneously the company’s biggest potential advantage and its hardest asset to value. Platforms in drug discovery can look brilliant on slides. They become real only when they repeatedly produce drugs that succeed in patients. Relay built Dynamo to do exactly that—then stepped into the clinic to prove it.

IV. From Stealth to War Chest: The Pre-IPO Years (2016-2019)

In the four years between its 2016 founding and its 2020 IPO, Relay stayed mostly out of the spotlight—and that was the point. While the public markets obsessed over late-stage clinical catalysts, Relay used the private years to do the slower, less glamorous work: build the machine, staff it with the right people, and line up enough capital to take real swings in the clinic.

The fundraising was a signal in itself. Relay raised a total of about $520 million across four rounds before it ever rang the opening bell. The $57 million Series A in September 2016, led by Third Rock and supported by an affiliate of D. E. Shaw Research, was an early stamp of credibility. But the later rounds were what turned Relay from a bold idea into a heavily financed platform company. By the time Series C came together—with SoftBank, Foresite Capital, and Tavistock Group among the participants—Relay had something few pre-product biotechs ever get: a true war chest to fund both platform building and multiple shots on goal.

Building the Team

Money alone doesn’t create a platform. People do—and Relay’s early hiring reflected how hard its thesis was to execute.

One GV board observer later described walking into an unassuming Cambridge office in 2016 to meet CEO Sanjiv Patel and a small group of team members. What stood out wasn’t polish. It was intensity: computational chemists, biochemists, and pharma veterans in a lively, almost argument-like debate about protein motion. The impression was immediate: this wasn’t a collection of specialists handing work off across silos. It was a group that could actually integrate across disciplines in real time—something that sounds easy in strategy decks and proves brutally difficult in practice.

That integration was the job. Relay needed computational scientists who could run and interpret long-timescale simulations, structural biologists who could anchor those models in experimental truth, and medicinal chemists who could turn an elegant binding hypothesis into an actual molecule a patient could take. And it needed them to collaborate tightly, because motion-based drug design only works when the loop between computation, experiment, and chemistry keeps closing—fast.

Cambridge helped. Sitting in Kendall Square put Relay in one of the deepest talent pools in biotech, with MIT, Harvard, and the Broad Institute essentially as neighbors. It also made recruiting easier in a subtler way: candidates could pressure-test the science through the founders’ academic connections and the broader ecosystem’s informal network.

Early Pipeline Development

Even as it built Dynamo, Relay also knew it needed something else: a pipeline that could prove the platform wasn’t just intellectually satisfying—it was productive.

In the private years, three programs emerged as the backbone of Relay’s early story.

The SHP2 program, RLY-1971, went after a phosphatase that sits in the middle of multiple cancer signaling pathways. Interest in SHP2 was growing across the industry, in part because of its potential role in combinations—especially alongside KRAS inhibitors—as a way to blunt resistance mechanisms that cancer cells use to escape targeted therapies.

The FGFR2 program, RLY-4008 (later lirafugratinib), targeted fibroblast growth factor receptor 2, a receptor tyrosine kinase altered in cancers including cholangiocarcinoma and certain gastric cancers. FGFR2 wasn’t a speculative target; it was already validated. The problem was the drugs: existing inhibitors often hit too much of the FGFR family and came with meaningful toxicity. Relay’s goal was selectivity—enough precision to keep efficacy while reducing the collateral damage.

And then there was the PI3Kα program, RLY-2608, now called zovegalisib—the one that would later matter most. PI3Kα is the most frequently mutated kinase in human cancer, with a particularly heavy footprint in breast cancer. The industry had been here before: PI3K inhibitors can work, but many have been boxed in by tolerability issues because they inhibit not just the mutant driver in tumors, but also the normal, wild-type protein that healthy cells rely on. Relay’s bet was that protein motion could reveal a path to something far more surgical: an allosteric inhibitor that could be mutant-selective, sparing wild-type PI3Kα while still hitting the cancer-driving variants hard.

By 2020, Relay could credibly tell a public-market story: not just “we have a platform,” but “we have multiple clinical-bound programs that came out of it.” That mattered, because platforms don’t get valued on elegance. They get valued on whether they can keep producing medicines—and whether those medicines can survive contact with patients.

V. The IPO Gamble: Going Public in a Pandemic

Going public in mid-2020 sounds, at first glance, like terrible timing. The world was deep in the early months of COVID-19. Markets were volatile. Whole sectors were freezing in place.

But biotech was living in a different reality. The pandemic didn’t just put healthcare on the front page—it reminded everyone, from governments to generalist investors, that biology can move markets. Capital flooded into the category, and for companies with a credible platform story and real programs behind it, the IPO window cracked open wide.

Relay went for it.

On July 15, 2020, Relay Therapeutics priced its initial public offering: 20,000,000 shares at $20.00 per share. Demand ran hot. The company ultimately closed an offering of 23,000,000 shares, including 3,000,000 shares from the underwriters’ option.

Gross proceeds were $460.0 million, before underwriting discounts, commissions, and other offering expenses. The next day, July 16, shares began trading on the Nasdaq Global Market under the symbol “RLAY.”

The Biotech Window Opens

COVID created a paradox for investors. In most crises, capital runs toward safety. In this one, biotech looked like the solution set—and money followed. As attention and valuations rose across the sector, Relay’s timing let it tap public markets when institutional demand for “the next big platform” was unusually strong.

Raising $460 million in a single shot made Relay one of the largest biotech IPOs of 2020. That mattered not just for the headline, but for what it bought the company: time, flexibility, and the ability to fund a platform and a pipeline in parallel.

The Pitch to Public Market Investors

Relay’s pitch was designed to sidestep the classic biotech trap: the single-asset coin flip. Instead, it leaned hard into a platform narrative—Dynamo as an engine, not a one-off project—paired with the reassurance that Dynamo was already producing real drug programs.

It also helped that Relay didn’t look like a typical early-stage story where investors are asked to take a leap of faith on unknown founders. The founding bench itself carried weight: David E. Shaw’s reputation in computational science, Mark Murcko’s track record helping shepherd drugs to market, and Dorothee Kern’s standing in protein dynamics. Relay was telling the market, in effect: the people who built the thesis are the people running the experiment.

And then there were the signals around the company—Cambridge, Kendall Square, and Third Rock Ventures’ involvement—each a familiar marker for public investors trying to separate durable biotech businesses from fashionable science projects.

“2020 was a transformational year for Relay Therapeutics. We successfully advanced multiple programs into the clinic, evolved our platform, expanded our strong team and completed a successful IPO,” said Sanjiv Patel, M.D., president and chief executive officer.

What the Proceeds Would Fund

Relay framed the IPO proceeds around execution: push its first three programs through clinical development, and keep Dynamo producing new candidates behind them. Just as important, the cash position after the offering gave the company a runway well into 2024—breathing room that let management stay focused on building and testing, not constantly returning to the market for the next financing.

In hindsight, Relay’s IPO is a clean snapshot of the era. The company caught the pandemic-driven biotech surge at exactly the right moment and raised a massive war chest on favorable terms. But it also set the bar: public investors don’t pay up forever for platform promise. Eventually, the story has to graduate from “movies of proteins” to medicines that work in patients.

And that’s where Relay headed next.

VI. The Genentech Partnership: Validation and Setback (2020-2024)

Five months after its IPO, Relay landed the kind of partner that can make a platform story feel real overnight. A top-tier pharma team had looked under the hood, kicked the tires, and decided Relay’s science was worth a serious check.

On December 14, 2020, Relay announced a worldwide license and collaboration with Genentech, the Roche subsidiary, centered on RLY-1971, its SHP2 inhibitor program. The headline was validation: Genentech would take over development, and Relay would get paid to keep building the rest of its pipeline.

The deal brought $75 million upfront, plus another $25 million in near-term payments. Beyond that sat a long ladder of potential milestones—between $410 million and $695 million—if the program hit the marks along the way. Genentech’s plan was to push RLY-1971 into combination studies, especially alongside its own KRAS G12C inhibitor, GDC-6036.

Why that pairing? Because in oncology, the first punch often isn’t the hard part. It’s what the tumor does next.

Why SHP2 Mattered

KRAS is one of the most frequently mutated drivers in cancer, and for decades it wore the label “undruggable.” When the first KRAS inhibitors finally started showing activity, another pattern emerged: tumors could respond, then adapt and escape. One hypothesized route around that escape was SHP2, a signaling node upstream of KRAS that can help reactivate the pathway. The logic was compelling: block KRAS, and also block SHP2, and maybe you cut off a major road cancer cells use to route around treatment.

Genentech had every reason to care. KRAS mutations show up across some of the toughest cancers—lung, colon, pancreatic—and the competitive field was quickly getting crowded. Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Johnson & Johnson, and Mirati Therapeutics had all advanced KRAS programs. If Genentech could build a durable combination strategy, it could matter.

“The choice came down to which option was going to give us the speed, scope and scale that we were looking for for our medicine. And Genentech was the ideal partner,” said Sanjiv Patel, Relay’s CEO.

The Deal Terms

For Relay, the structure checked several boxes at once. It was non-dilutive capital. It shifted major development cost and execution burden to a partner with enormous oncology muscle. And it signaled, loudly, that Relay’s way of doing discovery could produce an asset a world-class team wanted to bet on.

Relay also retained the ability to explore combinations beyond Genentech’s chosen path, preserving optionality even while partnering the core development.

The Termination

Then, four years later, the music stopped.

On July 11, 2024, Relay received notice that Genentech was terminating the collaboration and license agreement without cause. The termination was set to become effective 180 days after notice.

In practical terms, Genentech walked away after investing more than $120 million into the alliance and paying Relay $45 million in milestones, returning the rights to Relay. Just as important was what didn’t happen: Relay lost the opportunity to earn the remaining success-based milestones—roughly $675 million that, in December 2020, had made the deal feel like a potential jackpot.

The breakup wasn’t happening in a vacuum. SHP2, once one of the hottest targets in oncology, was cooling across the industry. Sanofi exited first, ending its Revolution Medicines pact in 2022. AbbVie followed by pulling back from a Jacobio deal in 2023. In early 2024, Bristol Myers Squibb terminated its agreement with BridgeBio Pharma.

Relay, too, chose not to shoulder the program alone. Three weeks after the Genentech decision became public, the company confirmed it would not continue development of migoprotafib.

What It Means

The Genentech episode is a clean illustration of how biotech value gets created—and how it disappears.

It shows that partner enthusiasm is real, but it’s not a guarantee. When Relay signed, SHP2 looked like a cornerstone of next-generation oncology combinations. By 2024, multiple large players had decided the target, the assets, or the timelines no longer justified the spend.

It also shows what milestones really are: possibility, not payment. Relay didn’t “lose” $675 million in cash—it lost a path to earning it, because Genentech’s priorities changed.

And for Relay, it forced a re-centering. If SHP2 wasn’t going to carry the story forward, something else had to. Patel pointed investors toward what was becoming increasingly obvious inside the company: the future was PI3Kα.

“We look forward to expanding the RLY-2608 development program, with the initiation of a new triplet combination with Pfizer’s novel investigative selective-CDK4 inhibitor atirmociclib by the end of the year,” Patel said after the termination.

Relay had built a platform to generate multiple shots. Now the market was going to judge it by the one shot it chose to prioritize.

VII. The ZebiAI Acquisition: Doubling Down on AI (2021)

While the Genentech partnership was still humming and Relay’s stock was still buoyed by post-IPO momentum, the company did something that’s rare for a newly public, clinical-stage biotech: it went shopping.

On April 16, 2021, Relay announced it was acquiring ZebiAI, a startup built around a very specific idea: take the massive, messy output of DNA-encoded libraries and use machine learning to turn that noise into usable signal for drug discovery.

Relay paid $85 million upfront—$20 million in cash and $65 million in Relay common stock. ZebiAI stockholders could earn up to another $85 million in platform and program milestones, paid in Relay stock. And there was one more sweetener: if Relay signed partnering or collaboration agreements tied to ZebiAI’s platform, ZebiAI stockholders would be entitled to 10% of those payments over the next three years, up to a total cap of $100 million, payable in cash.

What ZebiAI Brought

Relay already talked about AI and machine learning as part of its broader Dynamo story. ZebiAI added a more targeted weapon: machine-learning models trained specifically on DNA-encoded library data to predict small molecules with the potential to drug proteins.

DELs are one of the most powerful “search engines” in modern chemistry. You can build enormous collections of small molecules—often described in the billions—each tagged with a unique DNA barcode. Expose the library to a target protein, sequence what sticks, and you can identify binders without running a traditional one-compound-at-a-time screen.

But there’s a catch. DEL data can be noisy, and the difference between a real hit and a misleading artifact isn’t always obvious. That’s where ZebiAI’s approach stood out: instead of training models only on the molecules that bind, it also incorporated the molecules that don’t. That full picture—hits and non-hits—feeds machine-learning models developed in collaboration with Google’s Accelerated Sciences Group.

Strategic Rationale

The acquisition was Relay making a statement about where it thought durable advantage would come from. Better compute. Better models. Faster cycles from hypothesis to molecule.

CEO Sanjiv Patel framed it plainly: “The combination of ZebiAI’s approach with our Dynamo platform has the potential to predict more drug-like chemical starting points, reduce cycle time to compound optimization, and ultimately, increase the number and range of programs that can be developed in parallel.”

As part of the deal, ZebiAI’s chief learning officer, Rafael Gomez-Bombarelli—also a professor at MIT—joined Relay as an advisor, tightening the company’s already strong links to the academic and AI ecosystems around Cambridge.

In a world where most newly public biotechs narrow their focus to running the trials in front of them, Relay chose to keep investing in the machine behind the trials. It was a bet that the platform wasn’t finished—that the edge would belong to the company that kept upgrading its ability to turn biology into molecules, faster and more reliably than everyone else.

VIII. Pipeline Evolution: From Three Programs to a Strategic Focus (2020-2024)

From the IPO in 2020 through the end of 2024, Relay’s pipeline didn’t just grow up—it got reshaped. Some bets moved forward, some got handed off to partners, and at least one got shut down. It’s the normal, brutal arc of biotech: progress isn’t linear, and “platform productivity” only matters if you can afford to keep swinging.

RLY-1971 (SHP2 Inhibitor): Licensed, Then Returned

The SHP2 story ended the way many partnered programs do: with a clean break and a hard decision.

After Genentech terminated the collaboration in 2024, the rights to migoprotafib came back to Relay. Relay, in turn, chose not to continue development.

RLY-4008 (Lirafugratinib - FGFR2 Inhibitor): Out-Licensed to Elevar

By late 2024, Relay made another portfolio-defining move: it partnered away a promising asset to concentrate on the one it believed could carry the company.

In December 2024, Relay signed a global licensing agreement granting Elevar Therapeutics worldwide rights to develop and commercialize lirafugratinib (RLY-4008). The drug is an oral, small-molecule inhibitor designed to selectively target FGFR2, a receptor tyrosine kinase that’s frequently altered in certain cancers. That selectivity matters because FGFR2 is part of a closely related family of four FGFR proteins—hit the family too broadly and toxicity can start to dominate the risk-benefit equation.

Relay positioned lirafugratinib as a potential best-in-class FGFR2 inhibitor, with differentiated activity in FGFR2-driven cholangiocarcinoma and durable responses across multiple other FGFR2-altered solid tumors. Preclinically, the molecule showed FGFR2-dependent killing in cancer cell lines and regression in in vivo models, with minimal inhibition of other targets.

Financially, the deal gave Relay immediate and potential long-term upside: up to $500 million in upfront, regulatory, and commercial milestones, including $75 million in upfront and regulatory milestones, plus up to double-digit royalties on global sales.

Strategically, it was just as important that Elevar took on the heavy lifting from here—clinical development, NDA submissions, and global commercialization for FGFR2-driven cholangiocarcinoma and other FGFR2-altered solid tumors. Relay didn’t abandon the asset; it traded control for focus, keeping future economics while freeing resources for its lead program.

RLY-2608 (Zovegalisib - PI3Kα Inhibitor): The Crown Jewel

As Relay narrowed, one program steadily moved to the center of the story: PI3Kα.

Zovegalisib (RLY-2608) was designed to be the first allosteric, pan-mutant and isoform-selective PI3Kα inhibitor—aiming to cover both kinase mutations like H1047X and non-kinase mutations like E542X and E545X. PI3Kα sits at the heart of a signaling pathway tied to cell growth, proliferation, and survival, and large sequencing efforts have identified it as the most frequently mutated kinase in cancer.

The commercial logic is straightforward: it’s a big target in a big disease area. The scientific challenge is why this opportunity stayed open for so long.

Most PI3Kα inhibitors have historically gone after the active, or orthosteric, site. The problem is that orthosteric inhibition tends to struggle with selectivity—both mutant-versus-wild-type PI3Kα and PI3Kα versus other PI3K isoforms. That tradeoff shows up clinically as toxicity, which then forces lower doses, reduced dose intensity, and frequent discontinuation. In other words: the drugs can work, but the body often won’t tolerate enough of them for long enough.

Relay’s bet—consistent with everything Dynamo was built to do—was that an allosteric, mutant-selective approach could widen that therapeutic window.

Newer Programs: NRAS and Fabry Disease

Even as it tightened focus, Relay kept the platform engine running—pushing into new targets that showed Dynamo could generate shots beyond the first wave.

In oncology, Relay created what it described as the first NRAS-selective inhibitor, designed to address the liabilities of current pan-RAS inhibitors by binding only NRAS while sparing KRAS and HRAS. Relay expected to initiate clinical development of its NRAS-selective inhibitor in the second half of 2025.

And then there’s Fabry disease—a move outside oncology that signals broader ambition. In Fabry, a defective gene limits the body’s ability to produce enough healthy alpha-galactosidase A, an enzyme needed to break down a fat-like substance. When that process fails, harmful levels accumulate in cells and tissues, contributing to severe outcomes including kidney failure, heart failure, and stroke. In the U.S., approximately 8,000 people are estimated to live with this rare, progressive genetic disorder.

Taken together, these newer programs reinforced the platform narrative. But in 2024, Relay wasn’t being valued for breadth. It was being judged on whether its most important program—PI3Kα—could carry the weight.

IX. The RLY-2608 Inflection Point: Clinical Proof of Concept (2024-2025)

By 2024, Relay had spent years building Dynamo, raising capital, and reshaping its pipeline. What it still needed was the one thing that turns a platform into a company: clinical proof. With RLY-2608, that proof finally started to show up in patient data—and it suggested Relay hadn’t just made a PI3K drug. It might have made a better kind of PI3K drug.

The PI3Kα Challenge

PI3Kα is a compelling target in breast cancer, but it comes with a brutal tradeoff. Roughly 70% of breast cancers are hormone receptor-positive, and the standard approach in advanced HR+/HER2- disease is endocrine therapy plus a CDK4/6 inhibitor. The problem is what happens next. Resistance is common, and after progression, the field has needed better options.

The industry has tried PI3K inhibition before. Novartis’s Piqray (alpelisib), approved in 2019, blocks PI3K at its active site. That orthosteric approach can hit the pathway—but it struggles to tell the difference between the mutant PI3Kα driving a tumor and the wild-type PI3Kα healthy cells still need. In practice, that shows up as toxicity, including hyperglycemia, rash, and diarrhea, which can force dose reductions and lead patients to discontinue therapy.

That’s the core limitation of many orthosteric PI3K inhibitors: the therapeutic index gets squeezed by a lack of meaningful mutant-versus-wild-type selectivity and by off-isoform activity. Toxicity from inhibiting wild-type PI3Kα and other PI3K isoforms often means patients can’t stay at the dose intensity required for sustained control of mutant PI3Kα.

Relay's Solution: Allosteric Inhibition

RLY-2608 was designed to change the geometry of the problem. Instead of blocking the active site, it binds to an allosteric site—away from where PI3Kα performs its catalytic work, but still capable of controlling the protein’s function. The promise of that approach is selectivity: preferentially affecting mutant PI3Kα while sparing wild-type.

Zovegalisib (RLY-2608) was built directly from Relay’s motion-based playbook. Relay solved the full-length cryo-EM structure of PI3Kα, ran computational long time-scale molecular dynamics simulations to tease out conformational differences between wild-type and mutant PI3Kα, and used those insights to support the molecule’s design.

Clinical Results

In December 2024, at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, Relay shared updated interim clinical data for RLY-2608, describing it as the first known investigational allosteric, pan-mutant and isoform-selective inhibitor of PI3Kα. In second-line patients with PI3Kα-mutated, HR+, HER2- locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer, the combination of RLY-2608 at 600mg twice daily plus fulvestrant showed a median progression-free survival of 11.4 months.

At ASCO 2025, Relay presented updated data that stayed consistent with the December readout: a median progression-free survival of 11.0 months in the same second-line population, with a median follow-up of 12.5 months.

A subgroup analysis added an important wrinkle: patients with kinase mutations showed a median progression-free survival of 18.4 months, versus 8.5 months for patients with non-kinase mutations.

Why This Matters

The significance wasn’t just that the drug worked. It was that it appeared to work with a tolerability profile that looked meaningfully different from earlier-generation PI3K inhibitors—exactly the advantage Relay had been aiming for with an allosteric, mutant-selective design.

In the dataset Relay discussed, 31% of patients experienced a Grade 3 treatment-related adverse event, with no Grade 4-5 treatment-related adverse events reported. For a therapy that may need to be taken over long periods, that matters: tolerability is what determines whether patients can stay on treatment long enough, and at high enough doses, to benefit.

The Phase 3 Launch

With Phase 2 in hand, Relay moved quickly toward the test that counts. The company held an end-of-Phase 2 meeting with the FDA, announced its Phase 3 dose and trial design, and set plans to begin in mid-2025.

That registrational study, ReDiscover-2, is a randomized, open-label, multicenter Phase 3 trial evaluating zovegalisib (RLY-2608) plus fulvestrant in patients with PI3Kα-mutated, HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer previously treated with a CDK4/6 inhibitor—whether in the adjuvant or metastatic setting.

In mid-2025, Relay initiated ReDiscover-2.

The Triplet Strategy

Relay also wasn’t thinking only about the post-progression setting. If tolerability and efficacy held up, the bigger opportunity would be moving earlier—where the patient population is larger and the duration of therapy is longer.

To do that, Relay began pushing triplet combinations. Two front-line triplet regimens were advanced: one with ribociclib, a CDK4/6 standard of care, and another with Pfizer’s investigational selective-CDK4 inhibitor atirmociclib. Dose escalation of RLY-2608 plus ribociclib plus fulvestrant was ongoing with biologically active doses of RLY-2608, and the RLY-2608 plus atirmociclib plus fulvestrant arm of the ReDiscover study was initiated.

X. Strategic Pivots and Portfolio Prioritization (2024-2025)

By late 2024, Relay had run into the reality that eventually hits every platform company: you can’t fund every dream at once. When Genentech returned the SHP2 program and Relay simultaneously chose to out-license lirafugratinib, management made the next call almost inevitable—shrink the organization around the one program with a clear path to a registrational win.

Consolidating Resources

Relay’s makeover was blunt. Management cut research run-rate spend by about 80%, reduced research programs from four to one, and eliminated roughly 70 roles.

The subtext was simple: Relay was no longer trying to prove it could generate lots of ideas. It was trying to prove it could win one pivotal trial. And Phase 3 oncology trials aren’t just scientifically hard—they’re financially unforgiving. Keeping a broad research portfolio alive would have meant either raising more capital or accepting that the Phase 3 effort would be underpowered. Relay chose focus.

Financial Position

The cuts did what they were supposed to do: extend runway.

At the end of Q1 2025, Relay reported approximately $710 million in cash, cash equivalents, and investments. By September 30, 2025, that figure was $596.4 million. The company said it expected this cash runway to fund operations into 2029.

The expense line showed the same story. Research and development expense was $63.9 million for Q2 2025, down from $92.0 million in Q2 2024. Relay attributed the decrease primarily to the streamlining decisions made across 2024 and 2025, along with cost avoidance from no longer funding continued development of lirafugratinib after the Elevar licensing agreement.

What Investors Should Understand

This is what “portfolio prioritization” looks like in practice: fewer programs, fewer people, and fewer second chances.

Relay emerged more focused, with clearer visibility into the next set of meaningful clinical readouts—and with funding in place to get there. But it also became more binary. With so much of the company now tied to ReDiscover-2, the future increasingly hinges on one question: does RLY-2608 hold up in Phase 3?

If it does, Relay has a shot at turning a decade-long platform thesis into an approved medicine. If it doesn’t, there’s far less left to catch the fall.

XI. The Competitive Landscape and Market Opportunity

Relay is trying to win in one of oncology’s most crowded arenas: targeted therapy for breast cancer. PI3K has been a magnet for big pharma for a reason—it’s a real driver in a large patient population—but it’s also a graveyard of programs that couldn’t balance efficacy with tolerability. That’s the backdrop for RLY-2608: a differentiated approach, entering a market where the bar has risen and the players are well-funded.

Market Size

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibitor market in breast cancer was valued at about $1.2 billion in 2024, and forecasts expect it to grow materially over the next decade.

Relay is aiming at PI3Kα because it’s the most frequently mutated kinase across cancers, with oncogenic mutations detected in roughly 14% of patients with solid tumors. If RLY-2608 is approved, Relay believes it could potentially address more than 300,000 patients per year in the United States—an unusually large number for precision oncology.

Key Competitors

The most important competitive shift arrived in late 2024. On October 10, 2024, inavolisib received its first U.S. approval in combination with palbociclib and fulvestrant for adults with endocrine-resistant, PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer.

In the INAVO120 trial, median progression-free survival was 15.0 months for inavolisib plus palbociclib plus fulvestrant, versus 7.3 months for placebo plus palbociclib plus fulvestrant.

That approval sets a new benchmark. But it’s not an apples-to-apples fight—at least not yet. Inavolisib is approved in a first-line combination with a CDK4/6 inhibitor, while Relay’s Phase 3 study is focused on patients who have already been treated with a CDK4/6 inhibitor. And mechanistically, the drugs are different: inavolisib is an orthosteric inhibitor, while RLY-2608 is allosteric, which could translate into meaningfully different tolerability in real-world use.

There’s also the looming heavyweight matchup: Lilly. Building a wild-type-sparing PI3Kα inhibitor has started to look like a David versus Goliath battle, with Relay as the small-cap challenger. Relay’s Phase 3 trial for RLY-2608 went live on clinicaltrials.gov. Lilly hasn’t disclosed pivotal plans yet for STX-478—its lead contender gained through its January acquisition of Scorpion Therapeutics—but the implication is obvious. Relay likely has to move fast and stay ahead if it wants to define this category instead of chasing it.

Relay’s Differentiation

Everything comes back to whether Phase 3 can reproduce what Phase 1b/2 suggested: strong activity with a tolerability profile that makes long-duration therapy feasible. Competition from inavolisib, a next-generation PI3Kα inhibitor approved in 2025, could put real pressure on future market share. Relay’s argument for why it can still win is simple: a distinct allosteric mechanism, and what it believes is a superior tolerability profile.

For investors, this landscape cuts both ways. A large, growing market validates Relay’s target selection. But it also means the company won’t get credit for merely being “another PI3K drug.” To matter commercially, RLY-2608 has to be meaningfully better—clear enough that doctors, patients, and payers choose it in a world that already has options.

XII. Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

Relay is a useful case study for anyone trying to understand platform biotech—whether you’re building one or deciding whether to fund one. The story has all the ingredients: a compelling scientific thesis, a world-class founding team, a huge early capital base, a marquee pharma partnership, and then the hard part—focus, tradeoffs, and clinical proof.

Building at the Intersection

Relay’s founding insight—that protein motion matters for drug design—only works if you can actually operate across disciplines. Not “we have a computational group and a biology group,” but a team that can close the loop between simulation, experiment, chemistry, and, eventually, the clinic.

Relay’s early culture was built around that kind of integration. That’s rare, and it’s fragile. For investors, the lesson is to look for evidence that the collaboration is real: does the leadership team span the domains? Do they publish work that bridges them? Does the company’s decision-making show tight iteration between compute and wet lab, or just parallel tracks?

Founder-Led Science

Relay benefited from founder credibility in a way that’s hard to replicate with a purely business-built biotech. David E. Shaw, Mark Murcko, and Dorothee Kern didn’t just lend their names; their reputations made it easier to recruit talent, attract partners, and persuade investors that the approach had technical depth, not just marketing gloss.

In platform companies especially, belief is a form of financing. Relay raised big rounds early because sophisticated backers believed the founders could build the machine, not just describe it.

Platform Advantages and Risks

Relay’s IPO narrative was “multiple shots on goal.” But the next few years were a reminder of the fine print: a platform can generate lots of programs, and you can still end up living and dying by one.

The Genentech termination, the decision not to continue the SHP2 program internally, and the out-licensing of lirafugratinib weren’t contradictions of the platform idea—they were the reality of it. Platforms don’t automatically produce multiple winners at once, and they don’t eliminate the need to prioritize.

The investor takeaway is simple: the question isn’t whether a platform can produce a pipeline. The question is whether it produces individual assets that are meaningfully better than what the rest of the industry can build. RLY-2608’s clinical performance is the kind of signal that suggests Dynamo can create differentiated molecules—but the only proof that ultimately matters is approvals and real-world adoption.

Partnership Strategy

The Genentech deal shows both sides of the partnership coin. On the way in, partnerships provide non-dilutive capital, validation, and a development partner with scale. On the way out, they can disappear quickly—because partners aren’t married to your roadmap. They’re optimizing their own.

Relay got funding and credibility from Genentech. It also learned, publicly, that validation is not commitment, and milestones are not money until they’re earned.

Capital Allocation

Relay’s pivot toward RLY-2608 and away from broader platform expansion is what clinical-stage biotech often becomes: an exercise in choosing what not to do.

Phase 3 oncology trials consume enormous capital. Keeping multiple research programs alive at the same time raises the burn and forces harder financing decisions later. Relay chose focus over breadth—trading a wider set of long-dated options for a clearer shot at a registrational win.

The Key KPIs to Track

For anyone following Relay from here, two indicators matter most:

-

Phase 3 enrollment and timeline: ReDiscover-2’s pace determines when pivotal data arrives. If enrollment drags, the entire story stretches—time, cost, and competitive risk.

-

Cash runway versus execution: Management has guided to runway into 2029, but Phase 3 is expensive and unforgiving. Watching cash burn alongside trial progress is the cleanest way to judge whether Relay is staying on plan, or being forced into new tradeoffs.

XIII. Porter's 5 Forces and Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Relay’s story so far has been about science and execution. But whether that science becomes a durable business depends on something more old-fashioned: the structure of the industry it’s trying to win in, and whether Relay has any advantage that lasts once competitors catch up.

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High

In one sense, it’s getting easier to start a “computational drug discovery” company. Cloud computing has made serious compute accessible without owning proprietary machines. Academic breakthroughs in AI—most famously AlphaFold’s impact on structure prediction—have lowered the barrier to doing credible work. And there’s no shortage of well-capitalized peers chasing adjacent visions, including Isomorphic Labs (DeepMind), Recursion, and Schrödinger.

But there’s a difference between running models and turning those models into drugs. The hard part is translating computational insight into a molecule that survives medicinal chemistry, biology, toxicology, and then clinical reality. That integrated capability is still rare, and Relay’s years of platform development and accumulated know-how are a real barrier—even if some of the underlying tools have become more widely available.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Medium

Most of Relay’s “suppliers” are relatively commoditized: cloud infrastructure, vendors, and CROs. The real choke point is people. Experienced computational biologists, structural biologists, and chemists who can work inside an integrated loop are scarce and in demand. Being in Cambridge helps, but it also means Relay is competing every day with other top-tier biotechs and big pharma outposts for the same talent.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

If zovegalisib reaches the market, Relay won’t be selling into a gentle environment. The buyers—health systems, insurers, and pharmacy benefit managers—are sophisticated, price-sensitive, and increasingly strict about demanding evidence of real-world value. And because inavolisib is already approved, Relay will have to demonstrate clear differentiation to justify premium pricing or preferred positioning.

Threat of Substitutes: High

Even within PI3K, Relay is not competing in a vacuum. PI3K inhibition is one way to treat PIK3CA-mutated breast cancer, but it’s not the only way. The oncology toolkit keeps expanding—immunotherapies, antibody-drug conjugates, targeted protein degraders, and other pathway strategies can all compete for the same patients and lines of therapy. The substitute threat is constant because the standard of care doesn’t sit still.

Competitive Rivalry: High

This is the defining force. Precision oncology is crowded and well-funded, with Roche/Genentech, Novartis, Lilly, and many biotechs battling for overlapping populations. Even a Phase 3 win doesn’t guarantee a commercial win. Relay will have to compete on efficacy, tolerability, price, and awareness—while the bar continues to rise.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Cornered Resource: Moderate

Relay’s relationship with D. E. Shaw Research gives it access to specialized computational expertise and infrastructure that most companies can’t simply buy off the shelf. On top of that, Dynamo’s proprietary data, workflows, and algorithms represent real intellectual property. The limitation is that this advantage is hard for outsiders to independently verify, which can make it feel more like a promise than a measurable moat—until it repeatedly shows up as better drugs.

Scale Economies: Low Currently

Relay doesn’t yet enjoy meaningful scale advantages. If multiple drugs from Dynamo reach the market, the fixed cost of maintaining and improving the platform could be spread across products, and scale could start to matter. But today, that benefit is still theoretical.

Network Effects: None

This isn’t a consumer internet business. Relay’s success with one program doesn’t automatically create a network effect that makes the next program succeed. Each target still has to be earned.

Counter-Positioning: Moderate-High

Zovegalisib’s allosteric approach is a genuine strategic difference versus orthosteric PI3Kα inhibitors like inavolisib. If that mechanism translates into a real, clinically meaningful tolerability edge, it can be a durable form of counter-positioning. Competitors that have already invested heavily in orthosteric approaches may not be able to pivot quickly without writing off years of work and starting over.

Switching Costs: Low

Oncologists and patients will switch when a therapy is clearly better—more effective, better tolerated, or both. There’s no structural lock-in.

Branding: Low

Relay is still a clinical-stage company. In this industry, brand is earned the hard way: approvals, physician experience, and outcomes in real patients. Until that happens, branding power is limited.

Process Power: High

If Relay has a defensible “power,” it’s here. Dynamo is designed as a repeatable methodology—an integrated way of discovering and designing molecules that leverages protein motion through computation and experimentally anchored structural biology. That kind of process power is what platform companies promise: not one good idea, but a machine that keeps producing differentiated candidates, including against targets that have been difficult or inadequately addressed.

Primary Power: Process Power. If Dynamo can consistently turn motion-based insight into drugs that are meaningfully better—as RLY-2608’s early clinical profile suggests—Relay’s advantage compounds across programs. If it can’t, the platform is just expensive machinery without a product to justify it.

XIV. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The optimistic view is that RLY-2608 could be best-in-class, and that a Phase 3 win would establish a new standard of care. The heart of the bull thesis is simple: zovegalisib’s mutant-selective PI3Kα profile could let doctors hit the driver harder, for longer, without paying the usual price in chronic toxicity. If that holds, it’s not just “another PI3K drug.” It’s a new way to use the mechanism.

So far, the clinical story has been steady. Across updates, Relay has shown a median progression-free survival of roughly 11 months in a heavily pretreated second-line population—an outcome that looks strong against the historical backdrop. Just as important, the tolerability profile has looked meaningfully more manageable than earlier PI3K inhibitors, which is exactly what you’d want if the therapy is going to be taken chronically.

Financially, Relay has also bought itself time. With runway extended into 2029 and $710 million in cash and investments cited as the foundation, management can fund the pivotal work and keep its attention on execution instead of the next financing.

And then there’s the platform narrative—still the reason many investors showed up in the first place. Dynamo has already produced a differentiated lead asset, and the NRAS and Fabry programs point to breadth beyond a single oncology bet. If Relay can translate that into repeated clinical success, you can squint and see the endgame: “the Vertex of protein motion,” a company that turns a distinctive design approach into durable, compounding product output.

Partnerships add another layer of validation and optionality. The Pfizer collaboration around triplet combinations and the Elevar licensing deal for lirafugratinib both suggest that sophisticated counterparts continue to see value in Relay’s science—even as Relay has narrowed its internal focus.

Bear Case

The pessimistic view starts with the most unforgiving fact: Relay is still pre-revenue, and drug development is a cash-burning business even after a reset. Even with cost reductions, the company is still posting large quarterly losses, and Phase 3 is where budgets get eaten and timelines get stretched. If RLY-2608 disappoints in Phase 3, there isn’t a second late-stage asset waiting in the wings to catch the story.

The Genentech termination hangs over everything, too. Partnerships aren’t permanent, but when a top-tier oncology shop walks away, investors inevitably ask what they saw—or didn’t see—once the program met real-world development constraints. The broader retreat from SHP2 across the industry reinforces the point: sometimes the science is plausible, and the target still doesn’t become a drug.

Then there’s competition. Inavolisib’s October 2024 approval raised the bar and moved the market forward without Relay. Even if zovegalisib succeeds, Relay could be fighting uphill as a later entrant in an increasingly defined category. And Lilly’s acquisition of Scorpion Therapeutics made clear that well-funded competitors are also aiming at mutant-selective PI3Kα inhibition.

The stock performance tells you how the market is processing these risks. Shares remain far below the 2021 peak, reflecting skepticism that a single promising Phase 1b/2 dataset—however encouraging—can carry a company through a pivotal trial and into a commercial reality.

Finally, even a clinical win doesn’t automatically equal a business win. Manufacturing and commercialization add another layer of execution risk. Without an established commercial organization, Relay would likely need to partner or rapidly build capabilities, each with real cost and complexity.

Key Risks

- Clinical trial execution: Phase 3 enrollment and timelines could slip

- Regulatory approval uncertainty: Even positive data doesn’t guarantee approval

- Competitive dynamics: New entrants and shifting standards of care could erode potential share

- Cash burn requiring future financing: Despite current runway, setbacks could force dilutive capital raising

XV. Epilogue: Where Does Relay Go From Here?

As 2025 draws to a close, Relay stands at the most consequential moment in its nearly decade-long life. The thesis has been argued. The platform has been built. The capital has been raised. And the early clinical signals are finally on the board.

What’s left is the part no slide deck can solve: execution in Phase 3—and the biology’s verdict.

Near-Term Catalysts (2026)

Everything now orbits zovegalisib.

Relay’s clinical engine keeps running across multiple RLY-2608 studies: the pivotal Phase 3 ReDiscover-2 trial in PI3Kα-mutated HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer, the ongoing Phase 1/2 ReDiscover triplet cohorts, and the Phase 1/2 ReInspire study in vascular malformations.

ReDiscover-2 is the catalyst that matters most. Topline data will largely determine whether Relay can move toward a regulatory filing. A clean win could reshape the company’s valuation and its options overnight. A miss would force a hard reset—strategically, financially, and reputationally.

The triplet cohorts are the next layer of upside. If RLY-2608 can combine safely and effectively with CDK4/6 inhibitors, Relay’s opportunity expands beyond “what do you do after progression?” toward “can you compete earlier, where the market is larger and standards of care are already entrenched?”

Strategic Questions

Should Relay stay independent through Phase 3 or seek an acquirer?

There’s no easy answer, because the incentives point in opposite directions. If Phase 3 succeeds, selling early risks leaving huge value on the table. If Phase 3 disappoints, independence looks like a very expensive form of conviction. An acquisition would trade upside for certainty, and the “right” move depends on how management weighs risk tolerance against the value of control.

How should the company balance platform investment against RLY-2608 focus?

Relay already chose. The research consolidation was a deliberate pivot: maximize the probability of a registrational win instead of maximizing the number of shots on goal.

If RLY-2608 succeeds, Relay will face a new challenge—rebuilding pipeline momentum without losing the discipline it just enforced. If it fails, the painful counterfactual becomes obvious: a broader late-stage bench would have softened the fall.

What geographic expansion strategy makes sense?

A U.S. approval would be the start of a commercial decision tree. Relay would need to choose between building commercial infrastructure itself or partnering by region. Building preserves economics and control but demands time, talent, and capital. Partnering reduces execution burden but caps upside and can complicate global strategy.

The AI Drug Discovery Inflection

Relay’s story is also playing out inside a larger wave: the rapid legitimization of AI and computation in drug discovery.

Venture funding has poured into “AI biotech” since Relay’s founding, and big pharma has committed billions to partnerships that promise faster, cheaper, more reliable R&D. The field is no longer a curiosity—it’s crowded, well-funded, and moving fast.

That matters because Relay’s advantage is not “we use AI.” It’s whether motion-based drug design—its particular blend of simulation, experimental validation, and learning systems—produces medicines that are meaningfully better than what everyone else can build with increasingly similar tools. Relay’s early platform lead could prove durable. Or it could compress, quickly, as the ecosystem catches up.

What Success Looks Like

For long-term investors, “success” is no longer abstract. It looks like RLY-2608 earning approval in 2027–2028, showing a clinically meaningful advantage versus alternatives, and then—crucially—demonstrating that Dynamo can do it again with additional candidates.

Biggest Surprises Looking Back

From founding to the doorstep of pivotal data, Relay’s path delivered a few lessons the hard way:

- Speed: From 2016 to a pandemic IPO in 2020 to Phase 3 initiation in 2025 is fast for a platform-first company.

- Platform productivity: Dynamo generated eight drug candidates and four INDs—evidence that the engine can output real programs, not just hypotheses.

- Partnership reversals: Genentech’s termination after investing more than $120 million was a reminder that even elite validation isn’t permanent.

- Clinical differentiation: The Phase 1/2 profile suggesting improved tolerability versus earlier PI3K inhibitors offered the first real hint that “protein motion” could translate into patient-relevant advantage.

Final Reflection

Relay is an ambitious bet on a simple idea: if you can understand proteins as moving machines, you can design better drugs.

The clinic has offered encouragement—enough to justify a pivotal trial and a company-wide pivot around one asset. But encouragement isn’t the same thing as proof. The next few years will decide whether Relay becomes one of the small handful of biotechs that successfully industrialized a new way to make medicines—or another entry in the long list of platforms that looked inevitable right up until the biology disagreed.

For investors, the proposition is clear, even if it’s not comfortable: meaningful upside if RLY-2608 delivers in Phase 3, and meaningful downside if it doesn’t. Relay has the runway, the experience, and a coherent strategy. Now it needs the one thing no amount of capital can buy in advance: a Phase 3 outcome that holds up in the real world.

XVI. Further Reading and References

Top Resources

- Relay Therapeutics Investor Relations — ir.relaytx.com — SEC filings, earnings call transcripts, and investor presentations

- GV Blog: "The 100-Year Race towards Better Drug Discovery" — An IPO-era lens on Relay’s origins and the core scientific thesis

- SEC S-1 Filing (June 2020) — The definitive primary source for Relay’s pre-IPO story, risk factors, and financial context

- SABCS 2024 and 2025 Presentations — The key public clinical updates on RLY-2608 in breast cancer

- ASCO 2025 Data Presentation — Longer follow-up on efficacy and safety for RLY-2608

- D. E. Shaw Research Publications — Foundational Nature and Science work on protein dynamics simulations that underpin the broader “proteins-in-motion” approach

- FDA Approval Documentation for Inavolisib (October 2024) — The competitive benchmark for next-generation PI3Kα inhibition in HR+/HER2- breast cancer

- ClinicalTrials.gov: ReDiscover-2 (NCT06277234) — The Phase 3 blueprint: study design, endpoints, and eligibility criteria

- Journal of Medicinal Chemistry: ZebiAI Publication — A deeper technical look at the machine-learning approach to DNA-encoded library data integrated into Dynamo

- New England Journal of Medicine: INAVO120 Results — The pivotal trial data behind inavolisib’s clinical positioning and approval trajectory

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music