Rocket Lab: The "Mini-SpaceX" or Something Else Entirely?

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

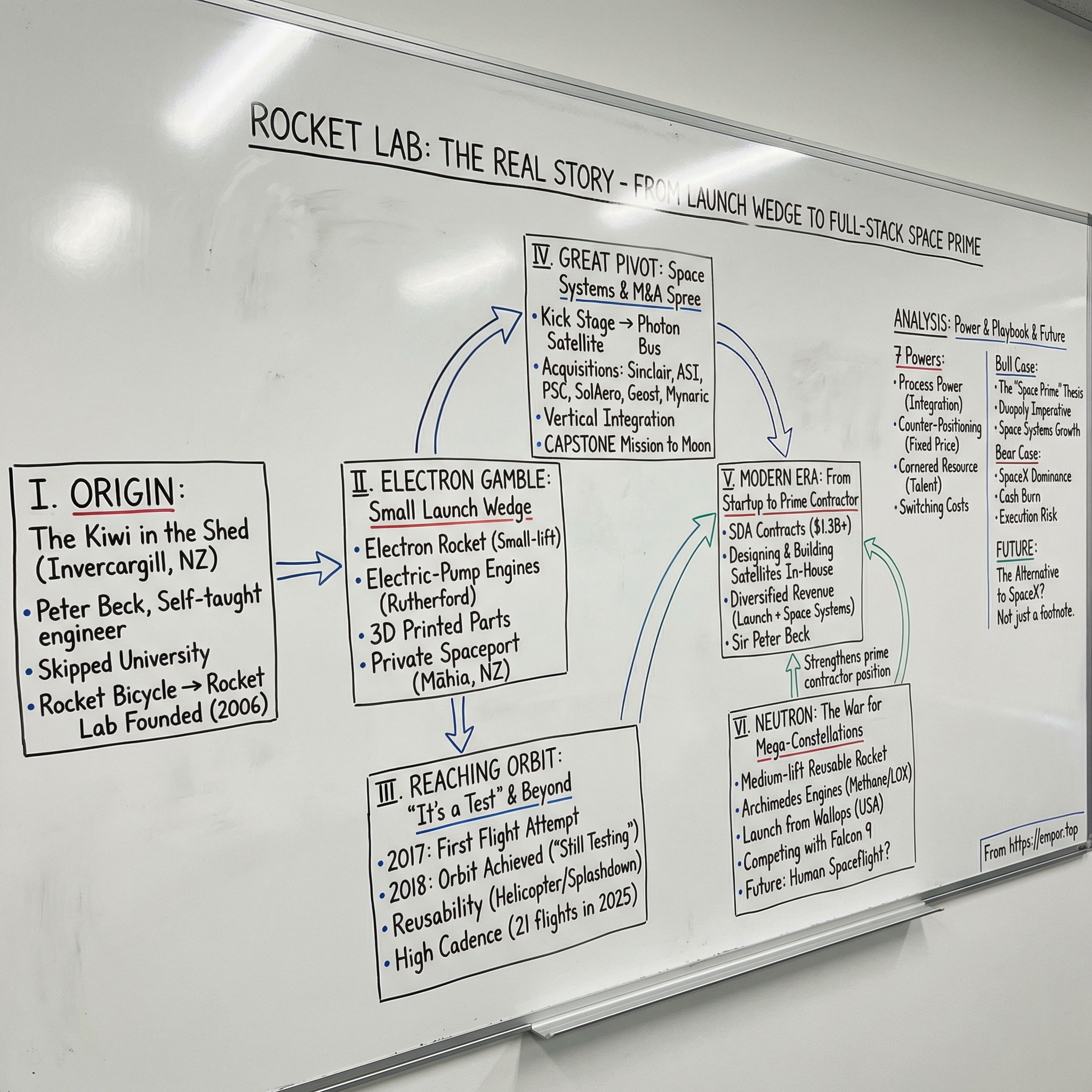

Picture the global launch market in late 2025. One company doesn’t just lead—it warps the entire scoreboard. SpaceX, under Elon Musk’s relentless pace, put up more than 170 Falcon 9 launches in a single year. It’s the kind of cadence that makes everyone else look less like competitors and more like side quests.

And yet, there’s a clear number two. Not a government program. Not a legacy prime. A company that began in a shed in New Zealand, built by a self-taught engineer who never went to university.

That company is Rocket Lab. And its story is widely misunderstood.

Most people file Rocket Lab away as a “small launch” business: the dedicated ride for small satellites, the alternative to waiting around for a slot on a rideshare mission. That’s not wrong. It’s just incomplete in the same way calling Amazon “an online bookstore” is technically true and strategically useless.

The real thesis is bigger: Rocket Lab used launch as the wedge. The rocket got them credibility, customers, and a reason to build factories. Then they started climbing the stack—turning themselves into a vertically integrated space infrastructure company. They aren’t just the FedEx truck. They’re becoming the manufacturer of what’s inside the box.

Look at what Rocket Lab is by January 2026. Electron has flown more than 75 missions, making it the most prolific small-lift launcher operating anywhere in the world. But launch is no longer the whole business, or even most of it. After the 2025 acquisitions of Geost, LLC and Mynaric AG, Rocket Lab generates roughly three quarters of its revenue from space systems: satellite components, sensors, and spacecraft hardware. They build solar panels, reaction wheels, star trackers, separation systems, flight software, satellite buses, and complete spacecraft.

And that changes who calls them—and why. When the U.S. Space Development Agency needs missile-warning satellites, Rocket Lab isn’t just in the conversation as a ride to orbit. They’re a prime contractor: design, build, test, and operate.

That shift showed up in 2025, Rocket Lab’s strongest year yet. Electron logged 21 successful flights, and the company stacked up major new awards, including an SDA contract worth up to $816 million to deliver 18 missile-warning satellites—the largest contract in Rocket Lab’s history.

So that’s the journey we’re tracing: from a garage in Auckland to the Nasdaq; from a radical, 3D-printed electric rocket engine to a pivot into satellites; and now to Neutron, the upcoming medium-lift rocket meant to take a swing at the Falcon 9-era monopoly. It’s a story about first-principles engineering in an industry addicted to legacy thinking, about using geography and regulation as strategy, and about an obsessive founder whose intensity belongs in the same sentence as his most famous rival.

Rocket Lab isn’t remarkable because it’s a smaller SpaceX.

It’s remarkable because it chose a different game—and it’s starting to win.

II. Origin Story: The Kiwi in the Shed

Invercargill sits at the bottom of New Zealand’s South Island—about as far from the aerospace world as you can get without leaving Earth. That’s where Peter Beck grew up, one of three brothers, in a household that had more to do with teaching and museums than mathletes and missile programs. His father, Russell, ran a museum and art gallery and was also a gemologist. His mother was a teacher. Not exactly the pipeline to rocket propulsion.

But the obsession showed up early. Beck has talked about standing outside as a kid with his dad, staring into the night sky. His father pointed out the stars and told him each one could have planets—maybe even someone looking back. For Beck, that idea didn’t land as poetry. It landed as a problem to solve.

Unlike most people who fall in love with space, he didn’t take the standard route. In 1993, he skipped college and went straight into an apprenticeship as a precision engineer at Fisher & Paykel. He moved through production machinery design, product design, and analysis—learning the kind of hands-on engineering that’s hard to fake and impossible to speed-run in a classroom.

And then he went home and kept building. Rockets weren’t a hobby he “picked up.” They were the thing he couldn’t put down. Even in high school he was experimenting, and those experiments weren’t the neat, safe kind. By the time he made his first big trip to the U.S., he’d already built a steam-powered rocket bicycle that could hit nearly 90 mph—one of those images that tells you everything you need to know about a founder’s wiring.

From 2001 to 2006, Beck worked at Industrial Research Limited on smart materials, composites, and superconductors. Along the way he met Stephen Tindall, who would later become one of Rocket Lab’s early backers.

Then came the pivotal year: 2006. Beck headed to the United States on what he has described, essentially, as a rocket pilgrimage. He’d dreamed of sending a rocket into space for years, and he hoped his garage-built experience might be enough to get him in the door at NASA or a major aerospace company—even as an intern.

Instead, he got walked out. Multiple times.

For a lot of people, that’s where the story ends: the outsider goes to the center of the industry, gets rejected, and goes home. For Beck, it was the moment the story started. If the establishment wasn’t going to let him in, he’d build his own way up.

So in June 2006, Peter Beck founded Rocket Lab in New Zealand.

And here’s the twist: being in New Zealand—far from legacy aerospace—wasn’t just a handicap. It was an advantage. There was no inherited “this is how we do it” culture. No decades of institutional gravity pulling every decision back toward the Apollo era. Beck didn’t have to unlearn Old Space. He got to start with a blank sheet.

Early money followed, slowly at first. Beck connected with New Zealand internet entrepreneur Mark Rocket, who became a key seed investor. Other early investors included Stephen Tindall, Vinod Khosla, and the New Zealand Government.

The first real proof point arrived in November 2009. Rocket Lab launched a multi-stage rocket called Ātea-1, becoming the first private company in the Southern Hemisphere to reach space. The payload was never recovered and the launch was deemed unsuccessful—but again, that wasn’t the point. The point was that a tiny team from the bottom of the world built a real rocket and sent it above the atmosphere. Beck later told The New Zealand Herald it was “life-changing,” and also quintessentially Rocket Lab: less glossy marketing, more hardware in the air. Do it first. Talk about it after. Now they had credibility.

But credibility in New Zealand wasn’t enough to build the company Beck wanted. He ran into a hard constraint that wasn’t engineering at all: regulation and market access. U.S. government customers were the center of gravity for launch, and ITAR—the International Traffic in Arms Regulations—made it extremely difficult for a New Zealand-built rocket company to fully serve that market. So around 2013, Rocket Lab moved its registration to the United States and set up headquarters in Huntington Beach, California. The logic was simple and brutal: to be a big space company, Rocket Lab had to be an American company.

Beck has been candid about how hard it was to get funded in those early days:

“Nothing happens without funding in this business. When I first started Rocket Lab, I ran around Silicon Valley trying to raise $5 million. At that time, that was an absurd amount of money for a rocket startup. A rocket startup was absurd [in general], it was only SpaceX then. A rocket startup from someone living in New Zealand was even more absurd.”

But that struggle stamped the culture. As Beck put it:

“We grew up and tried to raise really small amounts of funding. That really shaped us about being ruthlessly efficient and absolutely laser-focused on execution. The hardest thing [we did] is actually the thing that shaped the company into the most successful form it could be.”

That efficiency—born out of necessity, not slogans—became Rocket Lab’s operating system. And it set up the next, riskier bet: building a rocket designed not as a science project, but as a product.

III. The Electron Gamble: 3D Printing & Battery Straps

The insight that defined Electron wasn’t really about technology. It was about timing.

Peter Beck looked around and saw a quiet revolution in orbit: satellites were shrinking fast. CubeSats and other small spacecraft were suddenly good enough to do real work—built by universities, startups, and, in some cases, even high schools. But the way you got to space hadn’t changed. Rockets were still built for big, expensive payloads, and the little guys were treated like luggage.

If you were a small satellite operator, you didn’t “book a launch.” You waited. You became a secondary payload on someone else’s mission, on someone else’s schedule, to someone else’s orbit. Beck called it the “bus stop” problem: you stood there for ages, and when the bus finally arrived, it went wherever it felt like going.

Electron was designed to be the opposite of that. Not a rideshare. A dedicated trip. More like calling an Uber than waiting at the stop.

Beck’s pitch was simple: small satellites shouldn’t need endless patience, deep pockets, and a willingness to compromise just to reach orbit. Electron would give customers a way to launch on their timeline, to the orbit they actually wanted—without having to beg for space on a rocket built for something ten times bigger.

But if you want to build a small rocket that can reliably reach orbit, you run into a brutal reality: propulsion doesn’t scale down politely. The traditional approach uses turbopumps—high-speed, high-temperature machinery that is incredibly powerful and incredibly painful. They’re complex, expensive, and hard to manufacture. They work, but they’re the kind of “works” that comes with long lead times and long bills.

Beck’s solution sounded almost too clean: get rid of turbopumps entirely. Replace them with electric motors powered by batteries.

That idea ran straight into industry reflexes. Batteries are heavy. Rocket engines need enormous power. An orbital-class vehicle is not where you take cute risks. The physics, people said, didn’t pencil out.

Rocket Lab built it anyway.

The result was Rutherford: a LOX and RP-1 engine, and the first flight-ready engine to use an electric-pump-fed cycle. Electron follows a familiar architecture—two stages, nine identical engines on the first stage, and a vacuum-optimized version on the second stage—but the way those engines are fed is what made Electron different.

Then Rocket Lab doubled down on manufacturing. Rutherford wasn’t just a new engine cycle; it was built for repetition. Major engine components—like the combustion chamber, injectors, pumps, and main propellant valves—were 3D-printed using laser powder bed fusion (including Direct Metal Laser Solidification). The point wasn’t novelty. The point was time. Instead of months of machining and assembly, key parts could be produced in about a day—exactly the kind of advantage you need if your endgame is “launch often.”

By the time Electron had been flying for years, Rocket Lab had sent hundreds of Rutherford engines to space. It wasn’t a science fair trick. It became one of the most frequently flown U.S. orbital rocket engines.

Electron’s airframe matched that same product mindset. The rocket uses a lightweight carbon composite structure—built to keep mass down and performance up, even at a small scale. The promise was a dedicated mission to a precise orbit at a price that made smallsat operators feel like first-class customers for the first time.

But a rocket is only half a system. The other half is the place you launch it from.

Here Beck made one of Rocket Lab’s most strategically important moves: rather than fight for time on crowded government ranges, Rocket Lab built its own spaceport.

Rocket Lab Launch Complex 1 sits near Ahuriri Point at the southern tip of the Māhia Peninsula on New Zealand’s North Island. Remote geography is usually a disadvantage. Here, it was the feature. There’s minimal marine and air traffic, and the location supports a wide range of launch trajectories—meaning more flexibility, more availability, and fewer conflicts.

In other words: control.

Owning the launch site gave Rocket Lab something closer to a manufacturing rhythm than a “please approve our slot” rhythm. It’s the kind of advantage that compounds—what Hamilton Helmer would call Process Power—because you can iterate faster when you’re not waiting on someone else’s calendar. The site was approved for a rocket every 72 hours for 30 years.

Launch Complex 1 was officially opened on 26 September 2016 in a ceremony presided over by Minister for Economic Development Steven Joyce.

Rocket Lab was ready to fly.

IV. "It's a Test" and Reaching Orbit

May 25, 2017. Electron stood on the pad at Māhia, 17 meters tall and painted white, looking every bit like a “real” orbital rocket—because it was. Painted down the side was the mission name, equal parts swagger and understatement: “It’s a Test.”

The launch happened at 04:20 UTC from Rocket Lab’s Launch Complex 1. And for a while, it was exactly what Rocket Lab had promised the world it could do. The nine first-stage Rutherford engines lit and flew clean. Stage separation happened. The second stage ignited. Electron climbed past 200 kilometers.

Then the telemetry dropped out.

In launch operations, losing contact is one of the few things you don’t get to debate. With no reliable data coming back, the range safety officer followed procedure and sent the termination command. Electron was destroyed.

What made it especially brutal—and especially instructive—was what came out afterward. The rocket hadn’t failed. Later analysis traced the telemetry loss to a ground software failure. Electron had been flying well, with the second-stage engine operating normally. Rocket Lab lost the vehicle, but it didn’t lose the design.

The heartbreak was real, but so was the takeaway: this wasn’t a fundamental physics problem. It was a fixable systems problem. And Rocket Lab had just gathered an enormous amount of flight data from a rocket that, in all the ways that mattered, had worked.

Seven months later they went back, with another mission name that told you exactly how they viewed the process: “Still Testing.”

On 21 January 2018, Electron launched again, reached orbit, and deployed three CubeSats for customers Planet Labs and Spire Global. Peter Beck’s reaction was characteristically restrained—“Obviously, we’re very happy”—but the milestone was anything but small. With that flight, Launch Complex 1 became the first private spaceport to host a successful orbital launch.

Rocket Lab was in the history books. But orbit is only the opening act. The real business is what comes after: doing it again. And again. On schedule. With customers waiting.

As Beck put it, getting the first rocket to orbit is the easy part. On rocket number one, you can have everyone in the company hovering over a single vehicle for weeks. The hard part is building a system where rockets keep coming off the line—one after another—without the whole organization holding its breath each time.

Rocket Lab scaled steadily, and like every launch company that survives long enough, it took its punches. On 4 July 2020, Electron’s 13th flight—“Pics or It Didn’t Happen”—failed to reach orbit after an issue during the second-stage burn, and the payloads were lost. On 19 September 2023, another Electron mission failed when the second stage shut down shortly after separation, preventing delivery of a Capella Space synthetic-aperture radar imaging satellite.

Even with those setbacks, Electron built an enviable record. By this point in the story, the rocket had flown 74 times, with 70 successes and four failures—roughly a 95% success rate. In launch, that’s not just “good for a small rocket.” It’s good, period.

Then came the next evolution: reusability.

Beck had once dismissed it, arguing that small rockets didn’t have the margins for propulsive landings. But economics don’t care what you said in an interview. If reuse can move your costs and cadence in the right direction, the market keeps asking the same question until you answer it.

On 3 May 2022, Rocket Lab tried to answer it with a mission aptly named “There And Back Again.” Electron launched from New Zealand, and Rocket Lab attempted recovery for the first time. The plan was audacious: use proprietary aerothermal technology to manage reentry, deploy a parachute, then snag the descending booster mid-air with a helicopter.

They pulled it off—capturing the booster in mid-air, a historic first. But in the moment, the booster was hanging improperly, so the team released it to splash down under parachute. A ship retrieved it from the ocean.

It was classic Rocket Lab: clever, engineered, and unafraid to try something that sounded a little insane. It also revealed the reality of operations. Helicopter capture works, but it brings weather constraints and complexity. Rocket Lab ultimately shifted toward marine recovery as the primary approach for re-flight, aiming to make more missions “recoverable” and reduce the overhead of helicopter operations.

The program wasn’t just a publicity stunt. It fed directly back into hardware. Rocket Lab moved toward flying a pre-flown, 3D-printed Rutherford engine—one that had previously powered the “There and Back Again” mission—after extensive qualification and acceptance testing for re-flight.

And yes, Beck had famously said he’d never pursue reusability, then ate his hat on camera when he changed his mind. It was funny, but it also mattered: a founder publicly admitting the data won.

By late 2025, Electron was doing what it was built to do. Rocket Lab posted a perfect record across 21 missions that year, nearly doubling its previous annual high.

Electron had become a workhorse.

But Beck wasn’t building Rocket Lab just to be good at small launch. While Electron was racking up flights, he was already staring at the ceiling of what a small rocket business could become—and plotting the next move.

V. The Great Pivot: Space Systems & The M&A Spree

Somewhere around 2020, Peter Beck ran into a limit that no amount of clever engineering could erase: the small-launch market has a ceiling.

The logic was uncomfortable but simple. Even if Rocket Lab somehow captured the entire dedicated smallsat launch market, revenue would still top out in the low hundreds of millions. The customer base was fragmented and price-sensitive, and launch itself was a high-risk service business. One failure can wipe out months of momentum—and worse, shake customer confidence.

At the same time, Beck noticed something hiding in plain sight inside Rocket Lab’s own hardware.

Electron’s kick stage—the part that takes a payload from “we made it to orbit” to “we made it to the right orbit”—was already most of a spacecraft. It had power, attitude control, communications, propulsion. In 2020, Rocket Lab proved the point by launching its first self-built, self-designed satellite, called “First Light,” derived from that kick stage.

So the question practically asked itself: if you’re already going to space, why not build the satellite too?

That idea became Photon.

Photon is a satellite bus based on Rocket Lab’s Electron kick stage. Once a rocket like Electron boosts it to space, Photon can handle the rest—moving payloads into their target orbits and supporting missions ranging from LEO payload hosting to lunar flybys and interplanetary work. It’s customizable, and it uses chemical propulsion for orbit adjustments.

But going from “we can build a rocket” to “we can build spacecraft at scale” requires an entirely different toolset. Rather than spend years reinventing every subsystem, Rocket Lab did what the best industrial companies do when speed matters: it bought capability.

The shopping spree built on Rocket Lab’s earlier move into satellite components with the acquisition of Sinclair Interplanetary in April 2020, then accelerated with Advanced Solutions, Inc. (ASI) in October 2021, Planetary Systems Corporation in December 2021, and SolAero Holdings in January 2022.

Each deal filled a specific gap:

Sinclair Interplanetary (April 2020): A Canadian manufacturer of reaction wheels and star trackers—the hardware that lets a satellite orient itself and hold that orientation precisely. Rocket Lab said it would use Sinclair technology on the Photon line of small satellite buses, while also scaling production to sell components to other firms.

Advanced Solutions, Inc. (October 2021): Based in Littleton, Colorado, ASI builds off-the-shelf flight software and guidance, navigation, and control systems. Their software has flown across more than 45 spacecraft, totaling 135 cumulative years in space.

Planetary Systems Corporation (December 2021): Rocket Lab acquired PSC, a maker of separation systems, for $81.4 million. These are the mechanisms that push satellites cleanly off a launch vehicle—unsexy, but absolutely mission-critical.

SolAero Holdings (January 2022): Rocket Lab closed its previously announced acquisition of SolAero for $80 million in cash. SolAero supplies space solar power products and precision aerospace structures. As one of only two U.S. companies producing high-efficiency, space-grade solar cells, SolAero’s cells are among the highest-performing in the world.

The timing of all this wasn’t accidental. Rocket Lab funded the push with a public-market moment that, in hindsight, looks less like hype-chasing and more like opportunistic execution.

In 2021, Rocket Lab merged with SPAC Vector Acquisition, a deal that valued Rocket Lab at $4.8 billion in equity and brought in $777 million in gross proceeds, combining the SPAC trust and PIPE financing. Beck put the contrast bluntly in a CNBC interview: “I don’t think it will take long for investors to differentiate between the company that’s consistently delivering and the ones that have aspirations to deliver sometime in the future.”

Plenty of SPACs from that era turned out to be slideshows. Rocket Lab was flying real missions, shipping hardware, and using the capital not as “hope money,” but as acceleration fuel. As Beck said at the time: “It’s a tremendous amount of capital ... really puts us in a position not only to be aggressive in our organic growth but aggressive on our inorganic growth as well.”

This wasn’t M&A for the sake of empire-building. It was vertical integration with a purpose: control the supply chain, compress timelines, and own performance end to end. Rocket Lab later described this logic in concrete terms: for its SDA satellite work, all 18 satellites will integrate Rocket Lab-built subsystems and components, including solar panels, structures, star trackers, reaction wheels, radio, flight software, avionics, and the launch dispenser. That’s a rare level of control over cost, schedule, and quality in an industry that normally lives at the mercy of suppliers.

By that point, Rocket Lab had acquired five companies: Sinclair Interplanetary (April 2020), Advanced Solutions, Inc. (ASI) (October 2021), Planetary Systems Corporation (PSC) (December 2021), SolAero Holdings, Inc. (January 2022), and Geost, LLC (August 2025).

The most recent additions kept the pattern going, but moved Rocket Lab up the stack again—from “we build the spacecraft” toward “we build what the spacecraft sees and how it talks.”

In August 2025, Rocket Lab completed its acquisition of GEOST, a leader in space domain awareness and optical payload systems for national security missions. The deal expanded Rocket Lab’s reach deeper into defense and intelligence by adding on-orbit sensing and data delivery to its menu.

Rocket Lab is also advancing its acquisition of Mynaric, a German manufacturer of optical communication terminals, after the company completed its financial restructuring in August 2025. If finalized, it would become Rocket Lab’s first European acquisition and a move into laser communications.

Put it all together, and Rocket Lab was no longer “a launch company with some satellite aspirations.” It had turned into something closer to an end-to-end space factory. You could bring them a sensor or instrument, and they could build the satellite around it, launch it on their rocket, and operate it in orbit.

The proof showed up in one of the most vivid missions in the company’s history: CAPSTONE.

On June 28, 2022, Rocket Lab launched a CubeSat on a path to the Moon for NASA—a pathfinding mission supporting the Artemis program, which aims to land the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon. Using Electron and a new Lunar Photon upper stage, Rocket Lab sent the Cislunar Autonomous Positioning System Technology Operations and Navigation Experiment (CAPSTONE) into a highly efficient transfer orbit to the Moon.

CAPSTONE was Rocket Lab’s 27th Electron launch, but it mattered for what it signaled: the company’s first deep space mission, and the first use of Lunar Photon, a high-energy variant of the Rocket Lab-designed Photon spacecraft. Rocket Lab had already launched and continued to operate two low Earth orbit variants of Photon. Now it was stretching the same core platform beyond Earth orbit.

A company that started by building a small rocket in New Zealand had built a spacecraft and sent it to the Moon.

And it wasn’t stopping there. Mars and Venus were now on the roadmap.

VI. Neutron: The War for Mega-Constellations

"I said I'd never build a big rocket. I lied."

When Peter Beck said that in 2021, it landed as a punchline. But the strategy behind it was deadly serious.

Electron had become a world-class product for the smallsat era. The problem was that the biggest checks in launch weren’t written for small satellites anymore. They were written for mega-constellations: Starlink, OneWeb, Amazon’s Kuiper, and the Space Development Agency’s proliferated architecture. These programs don’t need a rocket that can launch a handful of satellites. They need a rocket that can deploy large batches, repeatedly, on tight schedules.

That market belonged to Falcon 9. And in the background, another force was building: the U.S. government’s growing discomfort with relying on a single provider for critical national security access to space. Alternatives like ULA’s Vulcan, Blue Origin’s New Glenn, and Arianespace’s Ariane 6 were either still ramping or aimed at different slices of the market. If Rocket Lab wanted to graduate from “the best small launcher” to a true peer in the highest-value category, it needed a new vehicle.

So Rocket Lab announced Neutron on March 1, 2021: a partially reusable, medium-lift, two-stage rocket designed for the mega-constellation delivery business. In its partially reusable configuration, Neutron is designed to deliver up to 13,000 kilograms to low Earth orbit.

Rocket Lab went even further in how it framed the bet. The company has forecast that Neutron could launch 98% of all payloads launched through 2029. And while its core target is constellation deployment, Rocket Lab has also positioned Neutron for deep-space missions and, eventually, human spaceflight.

The hardware is a step-change from Electron. Neutron is designed to stand about 43 meters tall and seven meters wide, and it runs on liquid methane and liquid oxygen. The first stage is intended to be recovered and land on Rocket Lab’s droneship, Return on Investment. Power comes from nine Archimedes engines on the first stage, with a single vacuum-optimized Archimedes on the second.

But the most visually distinctive part of Neutron isn’t the engine. It’s the fairing.

Rocket Lab calls it the “Hungry Hippo,” and it flips the standard rocket script. On most rockets, payload fairings get jettisoned mid-flight—expensive carbon composite shells, used once, then gone. On Neutron, the fairings are integrated into the first stage via hinges. At stage separation they open like jaws, and then close again so they can return and land with the booster. The goal is simple: bring back more of the rocket, more often, with less complexity.

Archimedes is the other big departure. Rutherford’s signature move was electric pumps. Archimedes goes in the opposite direction: high-performance, reusable-rocket propulsion. It uses an oxygen-rich staged combustion cycle—the same broad architecture SpaceX uses on Raptor—and Rocket Lab has said the full nine-engine first stage will produce 1.5 million pounds of thrust at liftoff.

And Rocket Lab has been moving fast. Neutron has been in development since early 2021, and in 2025 the program cleared major testing and certification milestones. In April, Rocket Lab qualified Neutron’s carbon-composite second-stage design in a test that applied 1.3 million pounds of tensile force to the structure. The company also tested flight software, avionics, and guidance systems under cryogenic conditions.

That pace isn’t cheap. Rocket Lab’s CFO said the company will have spent $360 million on Neutron development through the end of 2025, including about $15 million per quarter in workforce costs.

The original target was a first flight in 2025. That slipped. During Rocket Lab’s Q3 2025 earnings call, Beck pushed the first launch to 2026. He didn’t point to a single smoking gun. He framed it as risk retirement: with hardware on hand and test programs running across the vehicle, Rocket Lab wanted more time to prove the system before the first attempt.

“With all of the hardware in front of us now and significant testing programs underway across all parts of the vehicle, we can say we need a little bit more time to retire the risks,” Beck said on the Nov. 10 call.

If the first flight landed in early 2026, few people in the industry would be shocked. Even with some schedule drift, building a medium-lift rocket on a timeline that starts with a March 2021 announcement would still be unusually fast by aerospace standards. As Beck put it, “A few months here and there is somewhat irrelevant when looking at a 20 or 30-year lifespan of a product.”

By late 2025, the expectation was a mid-2026 debut. In September 2025, Rocket Lab said it planned three Neutron launches in 2026 and five in 2027.

Just as important: Neutron isn’t launching from New Zealand. It’s launching from the United States.

On February 28, 2022, Rocket Lab announced Neutron would fly from the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility on Virginia’s eastern coast, and that it would build a 250,000-square-foot manufacturing and operations facility adjacent to Wallops. Launch Complex 3 is the new test and launch site for Neutron, and Rocket Lab officially opened it as the program moved toward flight.

And there’s a reason Rocket Lab is doing all of this now. The market window is enormous. Rocket Lab has said Neutron’s timing positions it well to “on-ramp” to the U.S. government’s National Security Space Launch Lane 1 program, an indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity contract worth $5.6 billion over five years.

Commercial demand is showing up too. In November 2024, Rocket Lab announced a multi-launch agreement with a confidential commercial satellite constellation operator. The deal calls for two dedicated Neutron missions starting from mid-2026, launching from Launch Complex 3 on Wallops Island.

Neutron, in other words, isn’t just a bigger rocket. It’s Rocket Lab’s bid to become the only credible alternative to SpaceX for the most valuable launch contracts of the next decade.

VII. The Modern Era: From Startup to Prime Contractor

In January 2024, Rocket Lab crossed a threshold that changed how the industry looked at it. The Space Development Agency selected Rocket Lab—and put it under contract—to design and build 18 Tranche 2 Transport Layer-Beta Data Transport Satellites. Rocket Lab wasn’t showing up as a subcontractor or a niche supplier. It was the prime on a $515 million firm-fixed-price agreement, responsible for the design, development, production, testing, and operations of the satellites.

“This contract marks the beginning of Rocket Lab’s new era as a leading satellite prime. We’ve methodically executed on our strategy of developing and acquiring experienced teams, advanced technology, manufacturing facilities, and a robust spacecraft supply chain to make this possible.”

That was the point of the whole Space Systems buildout. Rocket Lab was no longer just a launch provider, or even merely a company that could manufacture satellites. It was now a defense prime—competing for, and winning, work that normally went to Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and L3Harris.

Then Rocket Lab went back for more.

In December 2025, the company was awarded a landmark prime contract by the Space Development Agency to design and manufacture 18 satellites for the Tracking Layer Tranche 3 program under the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture. At up to $816 million, it became Rocket Lab’s largest single contract to date. Under the award, Rocket Lab will deliver satellites equipped with advanced missile warning, tracking, and defense sensors—built to provide global, persistent detection and tracking of emerging missile threats, including hypersonic systems.

Together, Rocket Lab had now secured more than $1.3 billion in SDA contract value. That’s not “interesting for a former small-launch startup.” That’s the government effectively saying: we trust you to deliver at scale, in one of the highest-stakes categories in space.

Rocket Lab also emphasized a key differentiator in how it’s executing these SDA programs: it’s producing both spacecraft and payloads in-house for the SDA Tracking Layer. In a world where national security satellites often turn into slow, supplier-dependent science projects, Rocket Lab pitched a more disruptive formula—speed, resilience, and affordability driven by vertical integration.

The financials started to reflect the same shift. Rocket Lab posted record revenue of $155 million at a record GAAP gross margin of 37%, with a new annual launch record just days away.

Zooming out, Rocket Lab’s growth curve steepened. Revenue for the twelve months ending September 30, 2025 was $0.555 billion, up 52.42% year over year. Annual revenue for 2024 was $0.436 billion, a 78.34% increase from 2023. Rocket Lab finished its most successful fiscal year to date with annual revenue approaching $600 million.

Just as important as top-line growth was visibility. Rocket Lab reported a $1.1 billion contract backlog, which it described as bolstered by new international wins. The company said 57% of that backlog was expected to convert to revenue within the next 12 months.

This diversification fundamentally changed Rocket Lab’s risk profile. Launch failures still hurt—financially and reputationally—but they no longer threatened the company’s survival. Space Systems revenue doesn’t stop just because a rocket gets delayed. By leaning hard into spacecraft, components, and payloads, Rocket Lab insulated itself from the binary “success-or-failure” nature of launch.

The organization scaled to match. As of May 2025, Rocket Lab had more than 2,600 employees globally, including more than 700 based in New Zealand.

And Rocket Lab kept building a war chest for what came next. The company exited the quarter with more than $1 billion in liquidity following its at-the-market offering program, giving it room to keep investing—and to keep buying. Beck said Rocket Lab had an active acquisition pipeline, ranging from small tuck-ins for specialized capabilities to larger strategic deals.

The trajectory was no longer up for debate. Rocket Lab had evolved from a launch startup into a diversified space infrastructure company—one that could compete for, and win, the biggest and most strategically important contracts in the industry.

VIII. Analysis: Power & Playbook

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Process Power (The Strongest Power): Rocket Lab’s vertical integration creates compounding advantages that are hard for competitors to copy. Owning the launch site, the rocket factory, solar production, reaction wheels, and flight software means the company can iterate faster and hold tighter control over cost and schedule than anyone stitching together a program from suppliers. When something breaks, engineers don’t open a ticket with a vendor and wait for a delivery window. They walk down the hall, diagnose the issue, and change the design. Traditional primes, by contrast, coordinate across layers of subcontractors, each with their own incentives, timelines, and markups. The result is a rare level of certainty on cost, schedule, and quality—because Rocket Lab controls more of the system.

Counter-Positioning: Rocket Lab sits in a spot that legacy aerospace can’t attack without undermining its own business model.

Against Old Space, Rocket Lab sells fixed-price, increasingly standardized spacecraft and components. Traditional contractors lean on cost-plus programs that, by design, expand with complexity and delay. If the Space Development Agency signs Rocket Lab to a $515 million fixed-price deal, that number isn’t the beginning of a negotiation—it’s the constraint.

Against SpaceX, the contrast is different. SpaceX is pushing Starship and massive throughput. Rocket Lab is building for precision missions and for the broader supply chain—selling the “picks and shovels” of space systems to companies across the industry. And there’s a key trust advantage: SpaceX runs Starlink, which makes it a competitor to many satellite operators. Rocket Lab doesn’t have that conflict, which makes it an easier partner for customers who don’t want their vendor sitting on the other side of the table.

Cornered Resource: Talent is a real cornered resource in aerospace. There are only a handful of places where engineers can build hardware and see it fly to orbit regularly, and in the U.S., the list is short—SpaceX and Rocket Lab are the clearest examples. After years of industry shakeout, Rocket Lab can credibly offer something many aerospace companies can’t: the chance to ship, fly, learn, and ship again. For engineers who want outcomes instead of endless development cycles, that’s magnetic.

Switching Costs: Once a customer designs around a Photon bus and ASI flight software, switching is painful. Mechanical interfaces, electrical connections, software behavior, qualification plans, and ground systems all get tuned to that specific stack. Moving to a different provider means redesign, re-test, and re-certify—expensive, slow, and risky. Those switching costs create durable retention, and they get stronger as customers build multiple satellites on the same platform.

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Rivalry: Extremely high. SpaceX sets the pace, with a cadence and cost structure others struggle to match—more than 170 Falcon 9 launches in 2025 alone. Chinese launch providers are also advancing quickly, backed by state resources and a rapidly maturing industrial base. The competitive environment is unforgiving.

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate to low. The “launch filter” is brutal, and it has wiped out plenty of well-funded efforts, including Virgin Orbit and Astra. The capital barrier is enormous—Neutron alone has required more than $360 million in development spending, and Rocket Lab started that program with working factories, flight heritage, and a real launch cadence. New entrants also can’t shortcut credibility: by this point, Electron had flown around 80 times, with more than 70 successes. That kind of track record takes years, and the market doesn’t hand out trust on a PowerPoint schedule.

Supplier Power: Low. Rocket Lab is its own supplier for many critical systems because it deliberately bought those capabilities. That turns supplier risk into internal execution. Instead of negotiating with third parties for solar panels, separation systems, or software roadmaps, Rocket Lab can set priorities and optimize across the whole vehicle and spacecraft stack.

Buyer Power: High but shrinking. Launch customers are concentrated—governments and constellation operators can negotiate hard because they buy in bulk and can shift manifests. But as constellation demand increases and launch availability becomes the constraint, buyer leverage weakens. The SDA’s move to fixed-price awards across multiple providers also signals something important: the government will pay for redundancy and supply chain diversity, not just the lowest theoretical cost.

Substitute Threat: Low in the near term. If you need capabilities in orbit, you have to put hardware in orbit. Suborbital flights serve different missions, and ground-based alternatives can’t replicate the unique vantage point and coverage satellites provide.

IX. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

SpaceX Dominance: The existential question for Rocket Lab is whether Starship makes everything else obsolete. If SpaceX delivers even a meaningful fraction of what it’s promised—dramatically lower costs, massive payload capacity, fast reuse—the economics of launch shift underneath everyone. In that world, Neutron isn’t competing with Falcon 9 anymore; it’s competing with a new cost curve. And if customers can buy vastly more capacity for the same budget, it’s fair to ask why they’d choose a smaller rocket at a higher unit cost. This isn’t paranoia. It’s what happens when physics, scale, and reuse combine. If Starship works as advertised, Neutron could look uncompetitive on day one.

Cash Burn: Neutron is expensive, full stop. Rocket Lab will have spent $360 million on Neutron development through the end of 2025, including about $15 million per quarter in workforce costs. The company has raised substantial capital and maintained more than $1 billion in liquidity, but rocket development has a habit of eating cash and time. More testing, more delays, and more infrastructure all pull from the same pool—especially if Rocket Lab keeps pursuing acquisitions in parallel. If Neutron stretches out further than planned, the path to additional capital gets narrower, and shareholder dilution becomes hard to avoid.

Execution Risk: There’s also a different kind of risk that has nothing to do with engines: manufacturing. Building satellites by the dozens is one thing. Building them by the hundreds—on schedule, at consistent quality—is closer to automotive than aerospace, and Rocket Lab hasn’t fully proven that kind of throughput yet. The SDA awards are the opportunity, but they’re also the stress test. If Rocket Lab slips deliveries or quality on high-profile national security programs, it could dent the very reputation it’s working so hard to build as a reliable prime.

The Bull Case

The "Space Prime" Thesis: The upside case is that Rocket Lab becomes the Lockheed Martin of the 21st century—agile, vertically integrated, and profitable, with a modern tech stack instead of decades of inherited process. The 20th-century primes were built through consolidation and integration. Rocket Lab is following a similar playbook, but with the advantage of starting fresh, moving faster, and designing for production from the beginning. If it keeps executing, it can become the dominant non-SpaceX provider of space infrastructure.

The Duopoly Imperative: The U.S. government needs a second option besides SpaceX. Relying on a single provider—no matter how capable—is strategically uncomfortable, especially when national security is on the line. Rocket Lab is increasingly positioned as the most credible alternative, and its growing role as a prime contractor reinforces that. In practice, that can translate into real support: the government shaping procurement, award decisions, and program structures in ways that ensure redundancy exists—even if it means paying premiums relative to the cheapest possible launch.

Space Systems Growth: Even if launch only breaks even, selling the “shovels” in the gold rush can be a high-margin business. Solar panels, reaction wheels, separation systems—Rocket Lab sells these across the industry, including into programs where it isn’t the prime. StarLite sensors have also been adopted by other prime contractors developing TRKT3 satellites, expanding Rocket Lab’s footprint and potentially increasing total contract capture beyond its own satellite builds. In addition to the $816 million prime award value, Rocket Lab has described additional merchant-supplier opportunities that could lift the total capture value to approximately $1 billion.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

1. Launch Cadence & Success Rate: The most basic scoreboard. Electron’s cadence—21 missions in 2025—and its perfect record that year showed the machine is working. When Neutron begins flying, the key question won’t just be “did it reach orbit?” It’ll be how quickly Rocket Lab can ramp into a repeatable rhythm.

2. Space Systems Revenue as Percentage of Total: This is the cleanest indicator of whether the pivot is sticking. The higher this share goes, the less Rocket Lab’s fate depends on the volatility of launch—and the more it looks like a durable space infrastructure business.

3. Backlog Conversion Rate: Backlog only matters if it turns into revenue. With a $1.1 billion backlog and 57% expected to convert within 12 months, the story to watch is conversion: are satellites and components shipping on time, and are milestones turning into cash? Growth without conversion is a warning sign that execution is slipping.

X. Epilogue & Future

By 2026, the space industry was at an inflection point. The question wasn’t whether humanity would build real infrastructure in orbit—that was already underway, and speeding up. The question was who would get to build it, and what kind of companies they would be.

On paper, SpaceX’s lead looked untouchable. But technology markets have a habit of changing their answers. Dominance tends to attract new playbooks, not surrender. The same forces that helped SpaceX pull away—better components, software-first systems, and manufacturing built around iteration—were no longer exclusive. They were available to anyone willing to rethink the stack and execute relentlessly.

Rocket Lab’s wager was that it could become that “anyone.” Not by trying to clone SpaceX—Elon Musk cannot be out-Eloned—but by taking a different angle: vertical integration, fast cycles, and a customer posture that doesn’t come with the built-in conflict of also operating a mega-constellation. For plenty of satellite operators and government customers, SpaceX’s Starlink isn’t just a service. It’s a competitor. Rocket Lab’s bet was that neutrality, plus an end-to-end hardware stack, could be a durable advantage.

Electron would keep flying through 2026, but the company’s next chapter hinged on Neutron. Rocket Lab planned to debut the vehicle no earlier than mid-2026, and the next decade would determine what that decision really bought them.

If Neutron hit its targets and Rocket Lab captured a meaningful share of constellation and national security launches, the company had a path from “successful space company” to something closer to a modern aerospace major. And if the maiden flight went well, it would likely pull demand forward—more customers willing to commit manifests in 2027 and 2028, and a credible shot at scaling into the billion-dollar revenue tier.

If, on the other hand, Starship pushed the cost curve down so fast that medium-lift rockets struggled to justify their existence before Neutron could establish itself, the downside was just as stark. In this business, timing isn’t a detail. It’s the whole game.

Still, whatever happens next, the part Rocket Lab has already pulled off is difficult to overstate. Being at the forefront of one of the most complex engineering fields on Earth without formal education beyond high school is almost unheard of. Peter Beck built a rocket company from a shed in New Zealand, pioneered 3D-printed electric-pump-fed engines that experts said wouldn’t work, established the world’s first private orbital launch site, sent a Rocket Lab-built spacecraft on a path to the Moon, and positioned the company as a prime contractor for a U.S. missile-defense satellite constellation.

In 2024, Beck was honored as a Knight Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for his “exceptional contributions of New Zealanders to society,” earning him the title “Sir.”

Rocket Lab proved that space isn’t just for superpowers anymore. Whether it can prove that space isn’t just for SpaceX—that part hasn’t been written yet. But the attempt is real. And Rocket Lab’s odds are far better than anyone would have assigned when a Kiwi without a university degree started strapping rockets to bicycles.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music