Raymond James: The Firm That Kept Edward's Name on the Door

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

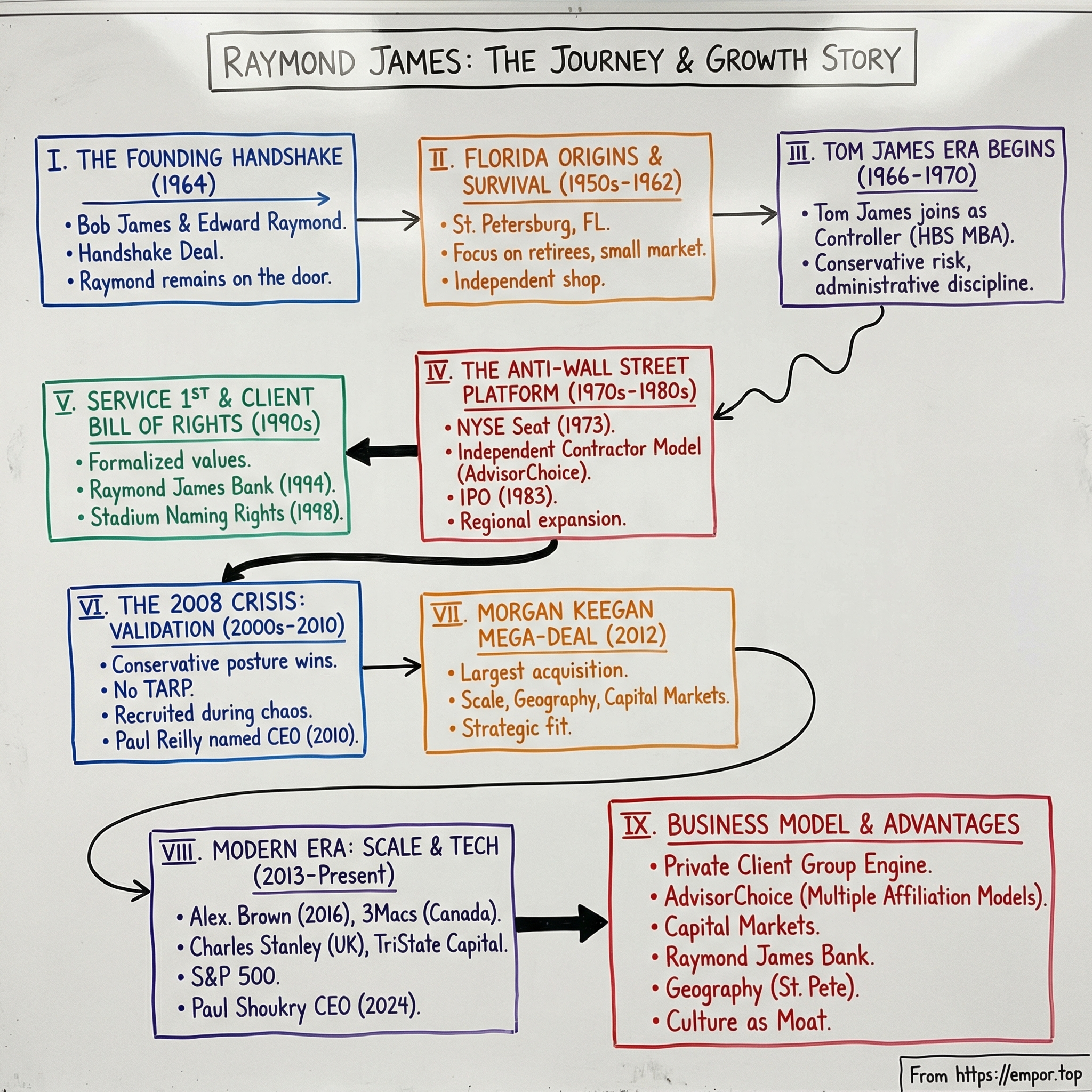

In the summer of 1964, a Florida stockbroker named Bob James made a handshake deal that would quietly set the tone for everything that came after. He agreed to put another man’s name ahead of his own on the door.

Three days later, that man—Edward Raymond—was nearly killed in a car accident. He never joined the business. Bob James kept the name anyway.

That choice still hangs over Raymond James Financial today: a firm overseeing $1.77 trillion in client assets, with nearly 9,000 financial advisors across the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and beyond. It has grown into a Fortune 500, S&P 500 company, and it has compiled a nearly four-decade streak of profitable quarters—through Black Monday, the dot-com boom and bust, the 2008 crisis, and the COVID era.

So how does a brokerage born in St. Petersburg, Florida—about as far from Wall Street as you can get and still be on the East Coast—turn into a financial heavyweight with a market cap north of $30 billion? The answer isn’t a single product or a single lucky break. It’s a philosophy: conservative risk-taking, an advisor-first operating model, patient dealmaking, and a deliberate refusal to mimic New York just because New York is loud.

This story is about what happens when you build a financial services firm around a few simple rules: put the client first, give great advisors multiple ways to build their practices, and never bet the firm. It’s about a father handing the keys to his 27-year-old son—and that son running the company for the next forty years. It’s about surviving near-death moments, both literal and financial, and using each one to harden the culture instead of abandoning it.

We’ll tell the Raymond James story in four acts: the early years of scrappy survival, the platform-building era under Tom James, the big acquisitions that created real scale, and the modern run of record results under professional management. Along the way, the lessons for founders, operators, and investors are everywhere.

Let’s start where this company really begins—with a man, a city, and a handshake.

II. Bob James & The Florida Origins (1950s–1962)

St. Petersburg, Florida, in the early 1960s wasn’t an obvious place to build a brokerage. The city’s national image was basically a postcard: retirees, park benches, and the slow, sunny rhythm of a place people moved to after their working lives were over. But Bob James looked at that same scene and saw something the New York financial establishment didn’t bother to notice.

Those retirees weren’t just passing time. They had assets. They had pensions. They had life savings. And they needed help.

James was a stockbroker working Florida’s Gulf Coast during the postwar boom that was remaking the state. Air conditioning made year-round living practical. Social Security made retirement portable. And Americans, in huge numbers, were voting with their feet for warmth and lower cost of living. Between 1950 and 1960, Florida’s population jumped dramatically, and the money moved with it. St. Petersburg wasn’t Wall Street’s center of gravity—but it was becoming a center of client demand.

In 1962, James took the leap and opened his own shop: Robert A. James Investments, based in St. Petersburg. He was stepping into an industry dominated by a few New York giants—Merrill Lynch, Dean Witter, E.F. Hutton—who ran national networks of branch offices from a Manhattan hub. There were independent firms too, but they tended to be small and constrained: limited research, limited infrastructure, limited product shelf. James was building from scratch in a market the big firms treated like a faraway outpost.

Then came the deal that created the name.

Edward Raymond ran Raymond & Associates, a mutual fund sales business with about fifteen employees serving Florida’s west coast out of Bradenton and Sarasota. He was ready to retire. On July 15, 1964, he agreed to sell to Bob James—on one condition: the combined firm would be renamed Raymond, James & Associates, with Raymond’s name first.

Three days later, Raymond was in a catastrophic car accident. He survived, but only after a long recovery, and he never joined the business he’d just sold.

At that point, the rational move would’ve been simple: change the name. Why keep advertising a partner who would never show up? But Bob James didn’t see it as branding. He saw it as a promise. He’d given his word, and he kept it. Raymond stayed on the door, ahead of James.

That moment became more than an anecdote. It turned into the kind of founding story that quietly sets the rules for everyone who comes after. Years later, when Raymond James people talk about integrity and putting clients first, it doesn’t land like a slogan. It traces back to an early choice: do the honorable thing, even when it’s inconvenient, even when nobody would blame you for doing otherwise.

The firm’s early growth matched its setting. It was built client by client, advisor by advisor, across the Gulf Coast. The work was plain: help retirees and middle-class Floridians invest sensibly. No proprietary products. No financial engineering. No big swings. Just relationships, advice, and commissions on stocks and mutual funds.

It was small-town finance, executed with discipline. And it worked.

But the decision that would determine whether Raymond James stayed a regional Florida shop—or became something far bigger—was still ahead. It wasn’t about a new product or a lucky market call.

It was about who would lead next.

III. Tom James Arrives: From Harvard to Home (1966–1970)

In 1966, a 23-year-old with a fresh Harvard Business School MBA walked into his father’s brokerage in St. Petersburg and took a decidedly unglamorous title: controller. His name was Thomas A. James. And over the next half-century, he would help turn a small Florida firm into a financial services powerhouse.

On paper, Tom James looked like a guy destined for New York. He’d finished his undergraduate degree at Harvard in 1964, graduating magna cum laude in economics, then stayed on for business school and graduated with high distinction. In that era, credentials like that were basically a one-way ticket to Wall Street or a top consulting firm.

Tom did the opposite. He went home.

That choice matters because it hints at the posture Raymond James would keep for decades: you don’t need to sit in Manhattan to build a serious financial business. Tom was betting on Florida, on a market the coasts still treated like flyover territory, and on building something durable with his family rather than chasing prestige.

The father-son pairing worked because their strengths were different. Bob James was the front man: relationships, trust, reputation. Tom was the builder: systems, controls, and the kind of operating discipline that doesn’t show up in marketing but determines whether a firm survives its first real storm. As controller, Tom’s job was to put structure around a business that had grown the old-fashioned way—through handshakes and hustle.

Then, in 1970, Bob James made the decision that would shape the next era of the company. At 50—young for a founder to step back—he handed the CEO job to his 27-year-old son. Bob stayed on as chairman. Tom became one of the youngest CEOs in the brokerage industry, and the move carried the same values as the founding handshake: Bob was willing to put someone else first, even if it looked unconventional.

It was also, from a timing standpoint, brutal.

Raymond James had incorporated as a holding company in 1969 with ambitions to go public. But the market turned, hard. When Tom took over, the firm was still small—about $3.3 million in revenue—and the macro backdrop was deteriorating fast.

The 1973–74 bear market was a gut punch to the entire industry. The S&P 500 fell by nearly half. For a thinly capitalized brokerage, it wasn’t a bad year; it was a survival test. Raymond James ran through cash. Five of its fourteen offices closed. Tom even sold pieces of his rare coin collection to help keep the lights on. He and his father went without salary until the business stabilized.

That’s the kind of moment that either breaks a firm or hardens it into something tougher. For Tom James, the takeaway was simple: never bet the firm. Don’t reach for upside if the downside can kill you. That conservative instinct—especially around leverage and risk—would go on to separate Raymond James from competitors who made bigger, flashier bets.

The downturn also forced a different kind of growth: administrative discipline. Tom used the crisis to tighten controls and build the infrastructure that lets a brokerage scale—process, oversight, the unglamorous back-office muscle that keeps you in business when markets don’t cooperate. So when conditions finally improved, Raymond James wasn’t just still standing. It was better run.

And that would become a recurring theme. The company’s 1969 IPO plans didn’t die, but they did get shelved—ultimately for fourteen years. The willingness to wait, to survive first and optimize later, wasn’t hesitation. It was strategy.

IV. Building the Anti-Wall Street Platform (1970s–1980s)

In 1973—the very year the bear market nearly finished Raymond James—the firm did something that, on paper, makes no sense: it bought a seat on the New York Stock Exchange.

It was a paradox. A Florida brokerage that was fighting for survival was now, technically, inside the most elite club in American finance. But strategically, it mattered. An NYSE seat improved trade execution for clients, expanded access to listed securities, and—just as important—gave Raymond James instant credibility. For prospects and recruits who still equated legitimacy with New York, it was a signal: we’re not a local shop playing pretend.

The bigger platform move, though, was the one that rewired the business model: Raymond James leaned into the independent contractor approach.

Most brokerages in the 1970s ran like classic corporations. Advisors were employees. They sat in firm-owned branches. They worked under firm rules. They sold what the firm wanted sold. The company got control, and the advisor got a paycheck.

Raymond James flipped the arrangement. It created an affiliation structure that let advisors operate as independent contractors—running their own practices, choosing their own office space, hiring their own staff, and building something they could truly call theirs. In return, they plugged into Raymond James for the parts that are hard to replicate alone: research, products, technology, compliance, and back-office operations.

The trade was deliberate. Raymond James took a smaller share of an advisor’s revenue than a traditional employer might, but it gained something far more scalable: growth without having to finance an ever-expanding network of company branches and employee overhead. The advisors became the entrepreneurs. Raymond James became the platform.

If you want the simplest analogy, it’s a franchise model for financial advice. The firm supplies the system; the advisor supplies the ambition and the local investment.

Over time, that approach evolved into what the company now calls AdvisorChoice: multiple ways for advisors to affiliate depending on how much independence they want. Some stayed in a traditional employee model. Others chose a more independent employee structure. Others went fully independent as contractors. And for advisors who wanted the RIA path but didn’t want to build everything from scratch, Raymond James offered custody and support services. The point wasn’t to force everyone into one box. It was to keep great advisors inside the Raymond James ecosystem as their careers—and preferences—changed.

That flexibility became one of the firm’s most effective recruiting tools. If you were suffocating inside a wirehouse hierarchy, Raymond James could offer a step down the independence ladder without making you jump off a cliff.

Expansion followed the same anti-Wall Street logic. Instead of trying to win Manhattan or Chicago head-on, Tom James pushed into secondary and tertiary markets across the South, Midwest, and West—places the big firms often treated as afterthoughts. These communities valued relationships. They valued continuity. And they didn’t particularly want to feel like they were buying advice shipped in from a distant headquarters.

Then came the moment the company had been circling since 1969: going public.

The IPO finally happened in 1983—fourteen years after Raymond James incorporated the holding company that was supposed to take it there. The offering raised $14 million. It wasn’t a splashy Wall Street deal. But for Raymond James, it was rocket fuel: more capital, more permanence, and a stronger platform for recruiting and expansion.

There was also a quiet sadness wrapped into the milestone. Bob James died in May 1983, just months before the IPO. The founder who had kept Edward Raymond’s name on the door never got to see the company listed as a public one.

By the end of the decade, the direction was clear. Raymond James had moved far beyond a Florida brokerage. Revenue had grown dramatically from where it was when Tom took over in 1970, and the firm now had a national footprint and a culture that consistently attracted advisors who wanted independence more than corporate hierarchy.

The real takeaway from this era is that Raymond James didn’t build its edge with a single brilliant stroke. It built it the slow way: by designing a model that let advisors act like owners, by expanding into markets others ignored, by investing in the unglamorous infrastructure that makes a financial firm trustworthy, and by holding tight to the conservative risk posture forged in the 1973–74 crash. Those advantages took years to assemble—and that’s exactly why competitors couldn’t copy them quickly.

V. The Service 1st Revolution & Client Bill of Rights (1990s)

By the early 1990s, Raymond James had outgrown its regional roots. It was a national firm now, with more offices, more advisors, and more distance between headquarters and the field. And Tom James knew the risk that comes with that kind of scaling: the culture that made you special can quietly evaporate.

So he did something that was both simple and oddly uncommon in financial services. He wrote it down.

The firm formalized its values into what became the “Service 1st” philosophy, anchored by a Client Bill of Rights—personally penned by Tom James. It spelled out, in plain language, what clients should expect from Raymond James: courteous service from every associate, communication that’s clear and understandable, recommendations based on the client’s needs and goals rather than the firm’s incentives, and strict confidentiality around personal information.

On one level, it reads like common sense. On another, it was a direct challenge to how much of the industry operated. This was an era when conflicts of interest were everywhere, when firms pushed products because they were profitable, and when complexity and fine print were features, not bugs. Putting these commitments in writing wasn’t just aspirational—it was a line in the sand. The message to advisors was implicit but unmistakable: if you can’t work this way, you shouldn’t work here.

It also solved a practical problem. As Raymond James expanded through recruiting and acquisitions, it needed a way to onboard people who didn’t “grow up” inside the firm. Culture doesn’t scale automatically—it dilutes. Service 1st gave Raymond James a shared language and a set of non-negotiables that traveled well, whether you were in a branch office, an independent contractor setup, or one of the firm’s other affiliation models.

In 1994, Raymond James broadened what it could offer clients by founding Raymond James Bank as a savings and loan association. It added another set of tools for advisors: deposit accounts, mortgages, and lending alongside investment portfolios. The industry was moving toward more full-service financial relationships, and Raymond James moved with it—but in its own style. The bank wasn’t built as an aggressive profit engine powered by risky lending. It was positioned as a service extension, meant to deepen relationships and make the advisor more valuable to the client.

That restraint would look especially smart later, when other institutions treated underwriting standards like an optional suggestion. But that’s a story for another chapter.

The 1990s also pushed the firm outward geographically. Raymond James had established a European presence beginning in 1987, and it continued building its international footprint through the decade. In Canada, Raymond James Ltd. grew steadily, giving the firm a durable base in a major market outside the U.S.

And then came the move that put the name “Raymond James” into the American sports vocabulary.

In June 1998, the firm bought the naming rights to the new Tampa Bay Buccaneers stadium for $32.5 million over thirteen years. Raymond James Stadium became a fixture on broadcasts and highlight reels, especially after the Buccaneers won Super Bowl XXXVII there in January 2003. For a firm competing with bigger, louder Wall Street brands—particularly in advisor recruiting—the stadium was marketing leverage that punched far above its weight. The deal was later extended in 2006 and again in 2016, and the current agreement runs through 2027.

Through all of this, the markets were doing what markets do: tempting people to abandon discipline. The late 1990s dot-com boom turned prudence into something that looked old-fashioned. Plenty of firms chased technology IPOs and trading profits with growing confidence that the party wouldn’t end.

Raymond James largely didn’t play that game. Tom James held to the instincts forged in the 1970s: don’t take the kind of risk that can kill you. No leveraged swings. No exotic complexity for the sake of it. So when the bubble finally broke in 2000, Raymond James didn’t just make it through—it didn’t have to spend years digging itself out of a crater.

The takeaway from the 1990s is that culture can be a moat, but only if you treat it like one—maintained, reinforced, and operationalized. Tom James spent this decade doing exactly that: growing the firm while making sure the values that built it didn’t get washed out by success. And that would matter a lot when the real stress test arrived.

VI. The 2008 Crisis: When Conservative Won (2000s–2010)

The 2008 financial crisis was the moment that validated almost everything Raymond James had spent decades building. While Wall Street’s biggest names staggered—Bear Stearns disappearing, Lehman Brothers collapsing, Merrill Lynch selling itself in a fire sale, and Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs converting to bank holding companies to tap emergency Federal Reserve support—Raymond James made it through without taking TARP funds or other government assistance.

That outcome wasn’t a clever trade in 2008. It was the result of choices made long before the headlines.

Tom James had a scar tissue most CEOs didn’t. The 1973–74 crash—the one where he sold his coin collection and went without a salary to keep the firm alive—left him permanently allergic to bets that could take the whole company down. For years leading into 2007, Raymond James leadership believed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were trouble. And the bank the firm had founded in 1994—the one designed as a conservative, relationship-driven extension of the brokerage—started shedding risk. After 2004, it moved away from riskier mortgage loans. While huge parts of the industry were piling into subprime mortgages and mortgage-backed securities, Raymond James Bank was quietly de-risking.

This wasn’t luck. It was policy.

Tom James often captured the philosophy with a line that became a north star inside the company: “The essence of investment management is the management of risks, not the management of returns.” In the years when higher yields were easiest to find in the most fragile places, Raymond James accepted less upside in exchange for durability. It was the same kind of trade-off embedded in the founding story: long-term integrity over short-term advantage.

That mindset showed up in the balance sheet too. While the stand-alone investment banks ran on extreme leverage, Raymond James kept capital levels conservative. And when the crisis hit, that conservatism didn’t just help the firm endure—it gave it room to play offense. As chaos, bailouts, and reputational damage rippled through the wirehouses, advisors began looking for an alternative. Raymond James recruited hard, bringing in more than 400 brokers during and immediately after the crisis, many from larger competitors whose people were exhausted by the dysfunction and the stigma of government rescue.

Not long after, the contrast became visible in the market. Raymond James shares reached record highs while some of the most storied Wall Street franchises were still trying to stitch themselves back together. The firm’s “premier alternative to Wall Street” positioning stopped sounding like branding and started sounding like evidence. When your competitors need a bailout and you don’t, the story tells itself.

The crisis also created the opening for one of the most important leadership transitions in company history. Tom James had been CEO for forty years—an almost unmatched run. In May 2009, he brought in Paul Reilly as president and CEO-designate. Reilly wasn’t a career broker. He came from management and governance-heavy roles: executive chairman of Korn/Ferry International, and before that CEO of KPMG International. That was the point. Raymond James didn’t need a star trader. It needed an operator who could scale a complex business without breaking the culture that made it work.

In May 2010, Reilly officially became CEO, with Tom James staying on as chairman. The handoff was calm, deliberate, and overlapping—continuity by design. In an era when competitors were cycling leaders in panic, Raymond James looked almost boring. And boring, in financial services, is often another word for safe.

Of course, the post-crisis years weren’t frictionless. The regulatory environment tightened across the industry, and Raymond James had to absorb the same kind of compliance build-out everyone else faced, including settling charges related to auction rate securities. The difference was that the firm didn’t have a decade’s worth of existential mistakes to unwind. The costs were real, but they were manageable.

The broader takeaway from 2008 is that Raymond James’s conservatism isn’t just a cultural preference—it functions like a competitive weapon. In an industry where major dislocations are inevitable, the firm that stays standing while others fall doesn’t merely survive. It gains share, attracts talent, and compounds. Raymond James has done that repeatedly, and its long run of profitable quarters is the scoreboard.

VII. The Morgan Keegan Mega-Deal (2012)

On April 2, 2012—almost exactly fifty years after Bob James opened his doors in St. Petersburg—Raymond James closed the largest acquisition in its history: Morgan Keegan & Company, bought from Regions Financial. The timing wasn’t accidental. This was Raymond James planting a flag: we’re not just the “alternative to Wall Street” anymore. We’re a scaled national competitor.

Morgan Keegan was a Memphis-based full-service brokerage and capital markets firm with deep roots across the South. Founded in 1969, it had grown into a serious regional franchise, with hundreds of offices across twenty states and thousands of employees. Regions had acquired the firm in 2001, but after the financial crisis it started divesting non-core businesses. For Raymond James, it was a rare opening: a large, established wealth management and capital markets platform, in familiar territory culturally and geographically, available from a motivated seller.

The headline price was $930 million. But the economics were a little more nuanced: Morgan Keegan paid a large dividend to Regions before the deal closed, bringing the total cash consideration to roughly $1.18 billion. Raymond James funded it with a mix of cash, debt, and a public equity offering. The key point wasn’t the mechanics—it was what the structure signaled. This was a big swing, but not a reckless one. The firm believed it could digest the deal without compromising the conservative balance-sheet posture that had carried it through 2008.

Strategically, Morgan Keegan filled in three gaps at once.

First: scale. The added advisor force pushed Raymond James beyond 6,000 financial advisors, putting it firmly in the top tier of full-service wealth managers outside the wirehouses—without having to become a wirehouse.

Second: geography. Morgan Keegan strengthened the firm’s presence across the Southeast, expanding Raymond James in places where relationship-driven advice still wins, and where many Wall Street brands never built deep roots.

Third: capital markets. Morgan Keegan brought a strong fixed income business, giving Raymond James a meaningful upgrade on the institutional side and more horsepower to serve larger clients.

A deal this big lives or dies on people. Morgan Keegan’s CEO, John Carson, joined Raymond James as president and a member of the executive committee, and he became head of Fixed Income Capital Markets. That wasn’t just a nice gesture. It gave institutional clients continuity, and it gave Morgan Keegan teams a familiar leader inside the new organization—exactly the kind of bridge that makes a merger stick.

And that’s what made this acquisition notable: it worked.

The financial services graveyard is full of “strategic” mergers that looked perfect on PowerPoint and fell apart in the field—advisor defections, client attrition, and cultures that never blend. Raymond James avoided the worst of that for a few reasons. The two firms weren’t opposites; they shared a regional, relationship-first sensibility. Raymond James also had a structural advantage: AdvisorChoice gave incoming advisors multiple paths to affiliate, rather than forcing everyone into a single model overnight. And, just as importantly, the firm had the operational discipline to run a complex integration without taking its eye off the day-to-day business.

Morgan Keegan didn’t just make Raymond James bigger. It made the company different: broader, more capable in capital markets, and undeniably national. It added roughly a thousand advisors, expanded client relationships across the Southeast, and created a playbook Raymond James would keep using—grow through acquisitions that fit the culture, enhance the platform, and don’t require betting the firm.

VIII. Modern Era: Scale, Technology & The Next Generation (2013–Present)

With Morgan Keegan integrated and the “big deal” muscle finally proven, Raymond James moved into a new phase: it could grow by recruiting advisors one by one, or it could buy entire platforms—and actually make them stick. Plenty of firms talk about being good acquirers. Raymond James had evidence.

In September 2016, it made one of its most brand-savvy moves: acquiring Deutsche Bank Wealth Management’s U.S. private client services unit and relaunching it under the name Alex. Brown. That name carries real weight. Alex. Brown & Sons—founded in Baltimore in 1800—was the first investment bank in the United States. Deutsche Bank had bought it in 1999, but by the mid-2010s, the German bank was pulling back. Raymond James stepped in and brought over 193 advisors—more than 90 percent of the pre-transaction headcount—along with sixteen branches concentrated in the Northeast and on the West Coast. The strategic point wasn’t just geography. It was capability: a stronger push into high-net-worth and ultra-high-net-worth clients, paired with a brand built for a white-glove audience.

That same year, the firm accelerated its Canadian expansion. Raymond James Ltd. acquired MacDougall, MacDougall & MacTier—better known as 3Macs—a storied Canadian dealer founded in 1849, before Confederation. Valued at less than 100 million Canadian dollars, the deal created Canada’s largest independent investment dealer, with over 33 billion Canadian dollars in client assets under administration. And in a move that felt deeply “Raymond James,” the 3Macs name stayed. It became a division of Raymond James, with its identity and history intact—an echo of Bob James keeping Edward Raymond’s name on the door decades earlier.

The milestones started stacking up. In June 2016, Raymond James entered the Fortune 500 for the first time, debuting at number 482. In March 2017, it joined the S&P 500. For a firm that began as a tiny St. Petersburg operation, those weren’t just badges. They were confirmation that the “anti-Wall Street” model had become a national institution.

International expansion continued too. In January 2022, Raymond James acquired Charles Stanley, a UK wealth manager, for approximately £279 million. The deal added roughly £27 billion in client assets and pushed total UK assets to over £40 billion. Charles Stanley, founded in 1792, kept its brand—another example of Raymond James buying capability and scale without insisting everything wear the same uniform.

A few months later, in June 2022, Raymond James broadened its banking footprint with the $1.1 billion acquisition of TriState Capital Holdings, a Pittsburgh-based bank specializing in private banking, commercial lending, and treasury management. The transaction also brought Chartwell Investment Partners into the company as a subsidiary of Carillon Tower Advisers, within Raymond James’s asset management arm.

By the time Paul Reilly’s CEO era was nearing its end, the scoreboard was hard to miss. Client assets under administration grew from roughly $400 billion when he took over in 2010 to well over $1 trillion by 2024. Revenue rose from around $3 billion to more than $14 billion. The advisor count increased from about 5,500 to nearly 9,000. And the streak of consecutive profitable quarters kept running.

The leadership baton passed with the same steady handoff that’s become a Raymond James pattern. In 2016, Reilly added the chairman title as Tom James became chairman emeritus. Tom remained on the board until February 2024, when he retired at age 81 after 48 years as a director—closing the final chapter of the father-son era that began when he became CEO in 1970.

Then came the next succession step. In March 2024, Raymond James announced that Paul Shoukry would succeed Paul Reilly as CEO. Shoukry had joined the firm fourteen years earlier through an assistant-to-the-chair program and had served as CFO since January 2020. He became only the fourth CEO in company history when he took the role on February 20, 2025. Reilly moved to executive chairman—still present, but clearly making room for the next generation to run.

And the deal machine kept moving. On January 15, 2026, Raymond James announced it would acquire Clark Capital Management Group, a Philadelphia-based investment manager with over $46 billion in discretionary and non-discretionary assets. Clark Capital, founded in 1986, will keep its brand and operate as an independent boutique within Raymond James Investment Management. The transaction is expected to close by the third quarter of 2026.

The other modern story—less flashy than acquisitions, but just as consequential—has been technology. Raymond James invested heavily in Advisor Access, a hub designed to give advisors a single login for research, portfolio management, planning tools, and client communications. On the client side, the Client Access portal offers secure portfolio monitoring, fund transfers, and document management through a system called Vault. In today’s wealth business, these capabilities are no longer differentiators; they’re prerequisites. What matters is execution—and Raymond James has built the digital plumbing without letting the firm turn into a cold, self-serve utility. The relationship model stayed the point. The technology became the multiplier.

IX. Business Model & Competitive Advantages

By the mid-2020s, Raymond James wasn’t just “a brokerage with a great culture.” It was a diversified financial services machine—and it reported its results across five segments: Private Client Group, Capital Markets, Asset Management, Raymond James Bank, and Other. One segment, though, towers over everything else. The Private Client Group is the engine, producing $10.18 billion in net revenues in fiscal 2025—about 72 percent of total firm revenue.

That dominance comes back to the same idea we’ve seen for decades: build a platform that great advisors actually want to live on. Raymond James calls that platform AdvisorChoice, and it’s built around four affiliation models.

At one end is the traditional employee channel: advisors in Raymond James-branded offices with full corporate support and benefits. Then there’s Advisor Select, an “independent employee” model—still W-2, still benefits, but with more control over where and how you run your practice. Next is the independent contractor business, where advisors take higher payouts but also take on more of their own overhead. That channel is the largest, representing close to 60 percent of the advisory force—around 4,700 advisors. And finally, there’s the independent RIA channel, built for fee-based advisors who want maximum autonomy while using Raymond James for custody and the infrastructure it’s hard to replicate alone.

This mix is more than a menu. It’s a moat.

When an advisor gets fed up at a wirehouse—comp plan changes, cultural whiplash, pressure to sell what the firm wants sold—Raymond James doesn’t offer one “take it or leave it” alternative. It offers a landing spot that matches what that advisor actually wants next. Stay an employee but in a different environment? Fine. Move toward independence without jumping off a cliff? Also fine. Go fully independent but keep strong technology, compliance, and custody behind you? That’s there too. The breadth matters because advisors’ needs change over the arc of a career, and Raymond James can keep them in the ecosystem through those transitions.

That’s also why “the premier alternative to Wall Street” works as positioning. It isn’t code for “smaller.” It’s code for “different.” Raymond James doesn’t try to win by simply outspending Morgan Stanley or Merrill Lynch—though it competes. It wins by offering something many wirehouse advisors feel they’ve lost: a client-first culture, a long-term operating mindset, conservative risk management, and a baseline respect for the advisor as a professional—not just a production number.

The rest of the company reinforces that core.

Capital Markets gives Raymond James institutional sales and trading in equities and fixed income, plus investment banking. It’s also where the firm’s research franchise lives: more than 60 analysts covering around 1,200 companies. That scale puts Raymond James among the top research providers in North America by company coverage, and among the top tier in small- and mid-cap coverage. The benefit isn’t just prestige. Research is a two-sided weapon: it serves institutional clients directly, and it arms Private Client Group advisors with in-house perspectives they can bring to their own client conversations—something many independent platforms can’t match.

Then there’s Raymond James Bank, which provides the balance sheet capabilities that matter in modern wealth management. As of December 2025, the bank reported record net loans of $53.4 billion. That lending capacity—mortgages, securities-based lending, commercial credit—lets advisors serve wealthy clients more holistically, and it keeps those relationships inside the Raymond James orbit instead of pushing clients out to third-party lenders.

Finally, there’s a quiet advantage that shapes everything: geography. Headquartering in St. Petersburg, Florida instead of New York City changes the cost structure, the talent dynamics, and the daily cultural gravity of the organization. It’s easier to build a firm around steady compounding when you aren’t living inside Wall Street’s pressure cooker. Raymond James employees consistently rate the firm as a top workplace—Glassdoor recognized it in both 2024 and 2025—and in its 2025 study, J.D. Power ranked Raymond James number one for advised investor satisfaction and trust.

In wealth management, those aren’t just nice awards. The product is advice, delivered through human relationships. And a firm that attracts, retains, and earns the trust of great advisors is holding the most durable advantage in the business.

X. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

The Raymond James story is a reminder that in a cyclical industry, the goal isn’t to look smart in the good times. It’s to still be standing—and trusted—when the bad times arrive.

The power of putting someone else's name first. Bob James didn’t keep “Raymond” on the door because it was clever marketing. He kept it because he’d given his word. That decision set a cultural baseline that can’t be faked later with slogans or onboarding videos. The deeper lesson is that credibility compounds. When you develop a reputation for doing what you said you’d do—whether with clients, advisors, employees, or acquisition partners—future deals get easier. Trust becomes a real operating advantage, not just a virtue.

Multi-generational succession planning done right. Bob James handed the CEO role to his son at 27. Tom James then set up Paul Reilly’s transition deliberately and with time. Reilly, in turn, spotted Paul Shoukry early and put him on a path to the top long before the announcement. Each handoff featured planning, overlap, and clarity—continuity without stagnation. In an industry where CEO changes often trigger advisor departures, client churn, and strategic whiplash, Raymond James has managed four leadership eras over six decades with unusual stability.

Building culture that scales across acquisitions. “Service 1st,” the Client Bill of Rights, and AdvisorChoice aren’t just internal talking points; they’re integration tools. They give acquired teams a clear way to plug into the platform without feeling like they’ve been swallowed. Morgan Keegan, Alex. Brown, 3Macs, and Charles Stanley all kept their identities while gaining Raymond James’s infrastructure and distribution. In financial services—where acquisitions often mean brand erasure followed by talent attrition—that approach is rare, and it’s a big part of why Raymond James’s deals tend to stick.

When to stay private versus go public. Raymond James incorporated its holding company in 1969, but it didn’t go public until 1983. In between, it endured the 1973–74 crash, tightened operations, and built the kind of financial discipline a public company needs to survive scrutiny. By the time it listed, the business was ready to be public without being run by the mood swings of the market. The lesson: going public is a tool, not a trophy. Use it when it strengthens the company, not when it’s merely available.

Conservative growth in cyclical industries. In finance, the firms that win long-term aren’t the ones that look the boldest at the top of the cycle. They’re the ones that don’t blow themselves up at the bottom. Raymond James’s long streak of profitable quarters is the scoreboard for that philosophy. It hasn’t needed to be the most aggressive player in the room; it’s been content to compound through cycles, and over decades, that consistency produces outsized outcomes.

Creating multiple paths to success. AdvisorChoice is essentially a distribution innovation: instead of demanding that every advisor fit one corporate mold, Raymond James built several models that match different working styles and different stages of a career. That expands the talent pool, reduces the reasons great advisors leave, and keeps relationships inside the ecosystem even as preferences change. The broader lesson applies well beyond wealth management: when you design for flexibility—real, meaningful choice—you don’t just attract more people. You keep them.

XI. Analysis & Investment Case

The bull case for Raymond James starts with demographics. The biggest intergenerational wealth transfer in history is underway—an estimated $84 trillion moving from baby boomers to their heirs over the coming decades. That money won’t just need to be invested; it will need to be organized. Estate planning. Tax strategy. Trust structures. Family conversations that are part finance, part psychology. A firm with nearly 9,000 advisors and a platform built to support long-term relationships is naturally positioned to benefit as that demand rises.

Scale is the second tailwind, and it shows up in a very practical way. With $1.77 trillion in client assets and more than $14 billion in annual revenue, Raymond James can keep spending on the parts of the business that clients don’t see but absolutely feel: technology that works, compliance that protects the franchise, research that supports advisors, and service that keeps affluent households from shopping around. And the momentum appears to be strengthening. Net new asset flows hit $30.8 billion in the most recent quarter—more than double the prior year—suggesting the value proposition is resonating with both advisors and clients.

Then there’s the balance sheet. Historically, Raymond James’s conservative posture sometimes meant it didn’t maximize returns on equity the way more leveraged competitors could in good times. But in the real world—where cycles eventually turn—that same conservatism becomes an asset. This is a firm that came through 2008 without a government bailout, and it had logged 151 consecutive profitable quarters. That kind of durability isn’t just comforting; it’s recruiting and retention fuel when clients and advisors start asking who they can trust for the next twenty years.

The bear case is simpler: pressure on pricing and pressure on relevance.

Fee compression has been the slow grind across wealth management for years. Index funds, robo-advisors, and zero-commission trading have all trained investors to expect more for less. Raymond James still makes much of its money through asset-based fees and commissions, so any broad, sustained decline in what clients are willing to pay flows directly into margins.

Technology disruption sits right next to that. Raymond James has invested heavily in its digital platforms, but it’s competing on two fronts at once: wirehouses with enormous tech budgets, and newer, digital-native platforms built for efficiency from day one. The strategic question isn’t whether Raymond James has good tools—it does. It’s whether a firm whose core product is the human advisor relationship can keep evolving fast enough as younger, more digitally native clients move into their prime earning and inheriting years.

Regulatory risk is the evergreen issue. Changes in fiduciary standards, broker-dealer rules, or banking regulations can add cost, limit flexibility, or force operational changes. And because Raymond James runs multiple affiliation models under the same umbrella, complexity itself can become an exposure if the rules shift.

If you look at Raymond James through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, two advantages stand out. The first is switching costs. Once a household’s financial life is truly integrated with an advisor—investments, banking, insurance coordination, tax and estate planning—the idea of moving isn’t just inconvenient. It’s emotionally taxing and operationally painful. The second is cornered resource: the advisor base. Experienced advisors with portable, long-standing client relationships are scarce, and Raymond James’s culture and platform are designed to attract and retain them.

Porter’s Five Forces also comes out reasonably favorable. Supplier power is low—Raymond James can access investment products from a wide universe of manufacturers. Buyer power is real—clients have choices—but softened by those same switching costs. New entrants face steep regulatory barriers and, more importantly, the time it takes to build trust and distribution. Substitutes like robo-advisors and self-directed platforms are meaningful, but they often serve a different set of needs than a full-service advisor relationship. Rivalry is intense, but it’s not purely a price war; it’s differentiated by service model, culture, and advisor experience.

For investors watching whether the story is getting better or worse, two operating signals matter more than almost anything else. First, net new assets—the cleanest read on whether the platform is attracting and keeping client wealth regardless of what markets are doing. Second, advisor growth and retention, because advisors are the distribution engine. If advisors stop joining or start leaving, revenue problems typically show up later. By that scoreboard, the near-9,000 advisor count—8,943 most recently—plus strong recruiting suggests the flywheel is still turning.

XII. Epilogue & Looking Forward

What would Bob James think if he walked into the firm’s headquarters on Carillon Parkway in St. Petersburg today? The modest brokerage he opened in 1962 has become a global financial services company: roughly 19,500 employees, nearly $1.8 trillion in client assets, and operations spanning three continents. And Edward Raymond’s name is still on the door—more than sixty years after the car accident that nearly took his life, and long after his death. It’s a daily reminder that at Raymond James, a promise kept isn’t a footnote. It’s an operating principle.

The next frontier is the second trillion. It took the firm more than fifty years to reach $1 trillion in client assets under administration, a milestone it hit in 2021. It crossed $1.5 trillion just a few years later. If the last decade is any guide, the march toward $2 trillion won’t be powered by a single breakthrough. It will come the same way Raymond James has always grown: recruiting great advisors, deepening relationships with existing clients, and buying businesses that fit—without breaking the culture in the process.

Paul Shoukry inherits the CEO seat with the firm at the strongest point in its history. Now comes the hard part: preserving what made Raymond James different while delivering the growth public market investors demand. Every financial services company that reaches this scale runs into that tension. Many resolve it by optimizing for growth and letting culture become marketing copy. Whether Raymond James can do the opposite—continue compounding without turning into the kind of firm it was built to be an alternative to—will shape the next era.

Technology, including artificial intelligence, will be one of the biggest forces on that outcome. The winners won’t be the firms that try to “automate away” advice. They’ll be the ones that use AI to make advisors sharper, faster, and more consistent—freeing them to spend more time on the parts of the job that actually require judgment and trust. Raymond James’s advisor-centric model gives it a natural advantage here. But the edge won’t come from philosophy. It will come from execution.

Wealth management is entering a new cycle of pressure and opportunity: fee compression, demographic change, evolving regulation, and a rapidly shifting technology baseline. Raymond James enters that environment with a long profitability streak, a diversified platform, and a culture built around a simple idea: keeping your word matters. In an industry that hasn’t always earned the benefit of the doubt, that may still be the most valuable asset on the balance sheet.

XIII. Recent News

Raymond James opened fiscal 2026 with a record first quarter, which it reported on January 28, 2026. Net revenues rose 6 percent year over year to $3.74 billion, and net income climbed to $562 million, or $2.79 per diluted share. Client assets under administration reached a new high of $1.77 trillion. Just as notably, net new assets were $30.8 billion—more than double the pace from the same quarter a year earlier—another sign that the flywheel is still turning.

Two weeks earlier, on January 15, 2026, the firm announced it would acquire Clark Capital Management Group, a Philadelphia-based investment manager overseeing more than $46 billion in assets. Clark Capital is expected to close by the third quarter of calendar 2026, and it will keep its brand and operate with independence inside Raymond James Investment Management—consistent with the company’s pattern of buying capabilities without erasing identities.

The leadership transition that set this next chapter in motion is now complete. Paul Shoukry took over as CEO on February 20, 2025, becoming only the fourth chief executive in the company’s 63-year history, while Paul Reilly moved into the executive chairman role. And in February 2024, Tom James—who ran the firm for four decades—stepped off the board after 48 years as a director, closing the last formal link to the era that defined Raymond James’s culture.

Shareholder returns stayed front and center as well. During the quarter, the firm raised its quarterly dividend 8 percent to $0.54 per share and repurchased $400 million of stock. Over the trailing twelve months, capital returned to shareholders totaled nearly $1.87 billion, or about 89 percent of earnings—an aggressive pace that underscores management’s confidence in the balance sheet and the business’s cash-generation.

And one last thread from the 1990s still runs on: the Raymond James Stadium naming rights deal continues through 2027, with the firm evaluating its options on renewal.

XIV. Links & Resources

Company Resources - Raymond James Investor Relations: raymondjames.com/investor-relations - Raymond James Company History: raymondjames.com/about-us/company-history - Annual Reports and SEC Filings: raymondjames.com/investor-relations/financial-information

Historical Context - FundingUniverse company profile: History of Raymond James Financial - Harvard Business School alumni profile: Thomas A. James (MBA 1966) - “Who is Raymond James?” — Raymond James careers site historical article

Industry Research - J.D. Power U.S. Investor Satisfaction Study (2025) - InvestmentNews coverage of advisor recruiting and the wealth management industry - Glassdoor Best Places to Work rankings (2024–2025)

Related Reading - Alex. Brown & Sons historical overview (founded 1800; often cited as America’s first investment bank) - MacDougall, MacDougall & MacTier (3Macs) historical background (founded 1849) - Charles Stanley company history (founded 1792)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music