REX American Resources: From Coal to Corn—The Unlikely Energy Pivot

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a boardroom in Dayton, Ohio, in 2006. Around the table sit executives carrying more than a century of coal-mining legacy—a business built in the era of steam locomotives and steel mills. For generations, the company’s mines supplied Midwestern utilities. Customers knew the name. Employees knew the work. The playbook had been written long ago, and everyone in the room had been living inside it.

Then the new CEO is about to suggest the one thing you don’t say inside a coal company: what if we walk away?

Stuart Rose wasn’t a classic coal executive. He didn’t rise up through the mines. He didn’t speak in seam depths and dragline specs. What he brought instead was an investor’s sense for asymmetry and a capital allocator’s obsession with timing. And what he saw in 2006 wasn’t a legacy to defend. It was a melting ice cube.

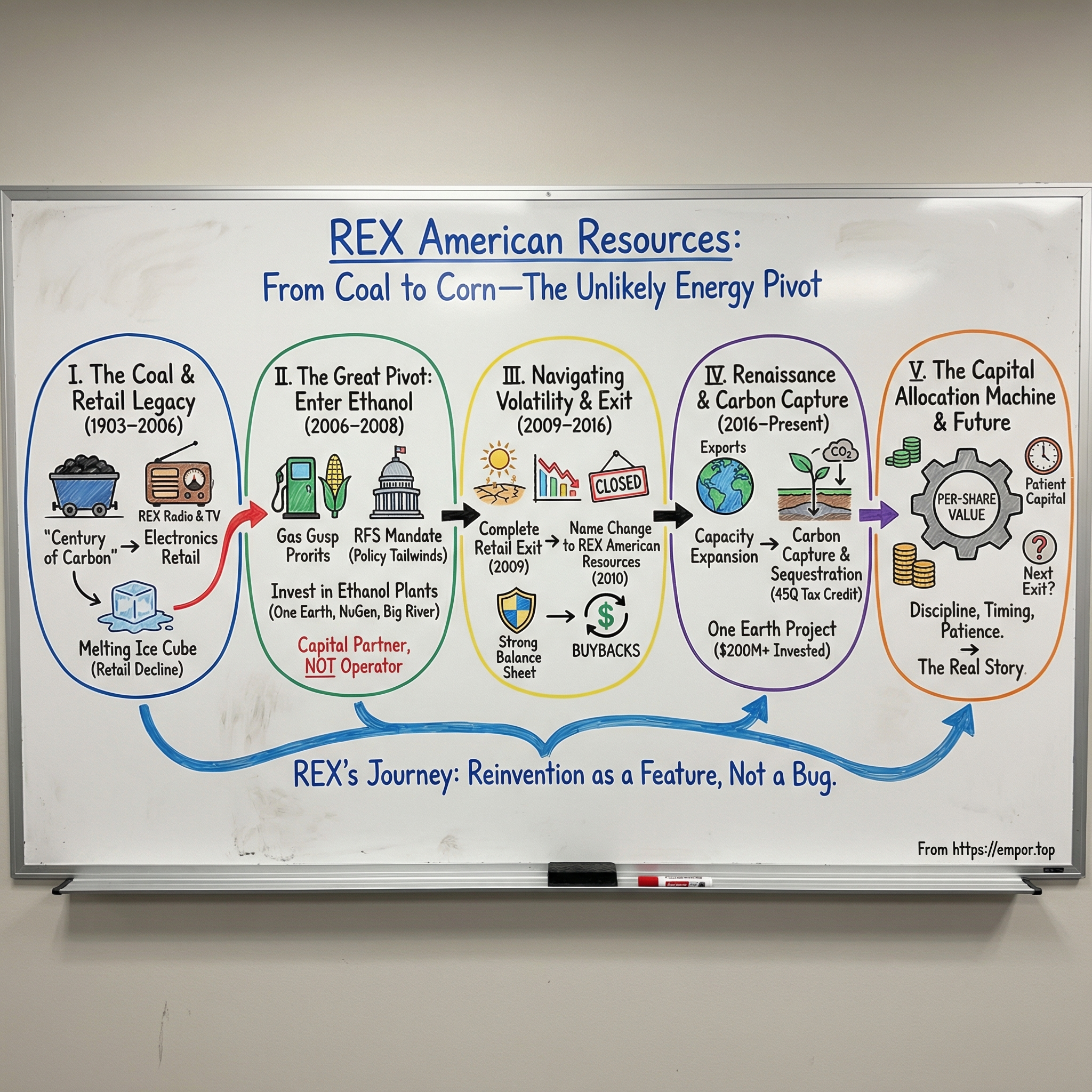

This is the story of REX American Resources, a roughly billion-dollar market cap company that most investors have never heard of. Today, REX American Resources Corporation, together with its subsidiaries, produces and sells ethanol in the United States. On paper, that sounds straightforward. In reality, it’s the end point of one of the strangest and most impressive reinventions in modern American business.

Because REX didn’t start in ethanol. Before coal, it was a consumer electronics chain. Before ethanol, it was a coal mining operation. And now it sits in renewable fuels—one public company that has managed not just one pivot, but two full identity swaps. Most management teams can’t change a logo without drama. REX changed its entire reason for existing—twice.

Rose served as Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer from REX’s incorporation in 1984 as a holding company, giving him one of the longest tenures in American corporate leadership. But the tenure isn’t the point. The point is the mindset: Rose treated the company less like a fixed operating identity and more like a portfolio of assets that needed to earn their keep. He’s also a rare book collector of international acclaim, with a distinguished private library spanning centuries of arts, literature, and sciences—a detail that feels oddly relevant for someone willing to challenge tradition and think in longer arcs than most executives ever do.

What makes REX fascinating isn’t just that it pivoted. It’s how. While much of the coal industry clung to the past, REX sold when valuations were high. When ethanol margins later compressed and plants went bankrupt, REX had the balance sheet—and the stomach—to buy. And as carbon capture economics began to reshape the industry, REX found itself positioned to benefit from the very policy tailwinds that now define the category.

This episode traces the full arc: from the coal mines of Appalachia to the corn fields of the Midwest, from regulatory tailwinds to commodity headwinds, and from a sleepy holding company to something closer to a capital allocation machine. Along the way, we’ll dig into the dynamics of the ethanol business, the structure behind REX’s partnership model, and what this story teaches founders and investors about reinvention, timing, and patience.

Let’s start where this kind of story always starts: with an industry beginning to crack—and a leader willing to admit it out loud.

II. The Coal Era: Century of Carbon (1903–2010)

The coal business Stuart Rose would later inherit wasn’t glamorous, but for a long time it was dependable. For more than a century, coal powered American industrialization—feeding steel mills, heating homes, and generating the electricity that lit up cities across the Midwest. In that world, companies like REX’s predecessor operations were simple, vital cogs: pull “black gold” from Appalachia and ship it to utilities that would buy as much as you could reliably deliver.

But the REX story has a twist that trips up almost everyone the first time they hear it. The company that would eventually become a major independent ethanol producer didn’t start in coal at all.

It started in retail.

In 1926, REX Stores Corp. began life as REX Radio: a single outlet in a Dayton hotel storefront. In the 1950s, it expanded into televisions and rebranded as REX Radio & TV—right in the sweet spot of postwar consumer electronics.

The pivotal moment came in 1980. The Dayton-area chain—by then four stores—was put up for sale, and the owner hired the New York firm Niederhoffer, Cross and Zeckhauser to find a buyer. One of the firm’s merger-and-acquisition brokers, Stuart Rose, saw something he wanted. He didn’t have much money, but he had discipline. He had saved $150,000 through frugal living—an early signal of the capital-allocation mindset that would later define the company.

As his credit improved, Rose was able to borrow aggressively, including financing the entire purchase price of $3.5 million for subsequent acquisitions. But leverage cuts both ways. With big debt payments and an appetite to keep expanding, he took the chain public in 1984 under a holding company, Audio/Video Affiliates, Inc. The IPO raised $18 million at $5 per share.

Those retail years gave Rose a front-row seat to a brutal truth: business models don’t die politely. In the late 1990s, REX ran headfirst into a wave of bigger, sharper competitors—Best Buy and Circuit City in electronics; Wal-Mart and Target in discount retail; Sam’s Club and Costco in warehouse clubs. Then, in the early 2000s, consumer behavior shifted again. Shoppers started buying LCD televisions online, and they turned to warehouse clubs and home improvement stores for “white goods.” Even the profitable home audio category began to erode as customers moved to digital music and portable devices.

Rose read the tea leaves. Instead of trying to outspend category killers or wage a slow retreat against e-commerce, he chose something far rarer in retail: a full exit.

By the mid-2000s, REX stores had closed its retail operations. Rose and a small team kept the public-company shell, but they reimagined what it was for—repositioning REX as an alternative energy company.

Which brings us to the real setup for what happens next. This isn’t just the story of a coal company pivoting into ethanol. It’s the story of a consumer electronics retailer that learned, the hard way, when to walk away—and then used that lesson to reinvent itself again and again.

III. The Great Pivot Begins: Enter Stuart Rose & Ethanol (2006–2008)

By the mid-2000s, Stuart Rose was staring at an unusual kind of problem: the consumer electronics business was winding down, and it was throwing off cash that needed a new mission. At the same time, Washington was running an energy-policy experiment that would end up reshaping American agriculture and fuel markets for decades.

That experiment was the Renewable Fuel Standard. Created under the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and expanded by the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, the RFS required oil refiners to blend increasing volumes of renewable fuels, like ethanol, into the nation’s gasoline supply. This wasn’t a “nice to have” subsidy. It was a mandate designed to create certainty: if you built renewable fuel capacity, there would be buyers on the other end.

The targets were huge, scaling from 4.0 billion gallons in 2006 to 36.0 billion gallons in 2022. In practical terms, it meant demand didn’t have to be “won” one customer at a time. It was being legislated into existence.

Rose understood what many investors missed. The debate at the time was whether ethanol could beat gasoline on pure economics. But Rose saw a different game. The RFS wasn’t a bet that ethanol would always be cheaper than oil. It was a legally enforced floor under the entire category. If you were investing, that changed everything.

So in 2006, REX began investing in ethanol production facilities—early enough to catch the first wave of the mandate, and before the 2007 expansion poured gasoline on the fire. Today, REX is invested in three ethanol production entities: One Earth Energy, LLC (One Earth), NuGen Energy, LLC (NuGen), and Big River Resources, LLC (Big River).

But Rose didn’t chase ethanol the way everyone else did. While farmer co-ops and private capital raced to build plants from scratch and run them directly, REX took a different stance: be the capital partner, not the operator. Take meaningful minority stakes, back teams that already knew how to run plants, and let discipline—not empire-building—do the heavy lifting.

He’d seen this movie before. REX had been a successful alternative energy investor since 1998, when synfuel investments of $6 million generated approximately $178 million of return over about a decade. That experience taught Rose a core lesson: when government incentives create a market, the best returns often go to the investor who structures the bet well and times it right.

One early example: REX acquired a 33.9% interest in what would become NuGen for $14 million, then sold its interests in the plant in 2007 to U.S. BioEnergy for approximately $24 million profit. Even without controlling the operation, REX could create value by entering smartly and exiting cleanly.

This wasn’t an operator’s strategy. It was a capital allocator’s strategy. Rose wasn’t trying to be the best ethanol producer in America. He was trying to place REX’s money into a policy-backed industry, alongside the best operators he could find, in a way that capped downside and left room for upside.

And that’s why the internal pushback—stick to what you know—missed the point. Rose did know what he was doing. The industry label mattered less than the structure underneath: asymmetric bets, demand shaped by policy, and a CEO willing to treat reinvention as a feature, not a crisis.

IV. The Complete Exit from Retail (2009–2010)

By 2009, a decision that had been forming for years finally snapped into focus. The last dependable corner of REX’s retail world—profitable home audio—was fading fast as consumers shifted to digital music and portable devices. REX had already closed its retail operations by the mid-2000s. Now it was time to make the exit official.

The broader consumer electronics landscape looked less like an industry and more like a cautionary tale. Circuit City filed for bankruptcy in 2008. CompUSA shut its doors. Amazon kept getting stronger, Walmart kept pushing prices down, and Best Buy’s category-killer model left little oxygen for a regional chain. Rose could have tried to hang on, to squeeze out a few more years. But he understood the difference between a turnaround and a slow-motion liquidation.

So REX did what most retailers can’t bring themselves to do: it walked away.

In fiscal 2009, REX exited retail entirely, and the results were classified as discontinued operations. And in 2009, the company formally shifted its business focus to energy—then made it unmistakable in 2010 by changing its name to REX American Resources Corporation. This wasn’t a marketing refresh. It was a corporate rebirth. The company that had spent decades selling stereos and televisions was now building an identity around ethanol and distillers grains.

Of course, retail doesn’t disappear cleanly. It leaves footprints—mainly in real estate. As of April 30, 2010, REX was the landlord on lease or sub-lease agreements covering all or parts of ten former store locations. It also had 30 former retail stores and one former distribution center sitting vacant, being marketed to lease or sell.

That leftover property portfolio—basically the residue of the retail era—would generate income and occasional gains as locations were monetized over the following decade. But the real story wasn’t the rent checks. It was what Rose did with the capital retail no longer consumed.

As of April 30, 2010, REX had $101.4 million in cash and cash equivalents, including $86.1 million at the parent company. With minimal debt and growing cash flows from its ethanol investments, REX now had something rare: a clean balance sheet and the freedom to play offense when the ethanol industry hit turbulence.

And the timing mattered. By getting out while the sector was collapsing around them—but before the wreckage forced desperate write-downs—REX preserved capital that other chains lost. By keeping the public-company shell intact, it also kept credibility and flexibility: a platform that could fund deals, attract partners, and scale into a new industry.

What’s striking in hindsight is how little nostalgia there was in the execution. No hybrid model. No “keep a few stores.” Rose knew half-measures would sap attention and money. When REX chose ethanol, it didn’t dabble. It committed.

V. Doubling Down on Ethanol: Building the Portfolio (2010–2015)

With retail behind it and cash on hand, REX entered the most opportunistic stretch of its ethanol thesis. The financial crisis and the commodity whiplash that followed didn’t just make ethanol volatile; they left plenty of weaker producers overextended. For a disciplined buyer, it turned the industry into a buyer’s market.

Rose’s approach was simple to describe and hard to do well: don’t build plants, don’t try to be the best operator in the business. Instead, be the capital partner to teams that already know how to run these assets, and structure the ownership so you get meaningful exposure without betting the company on any single facility.

In practice, that meant a portfolio. REX became a minority owner of Big River Resources, LLC, a holding company for four ethanol production plants with combined capacity of approximately 430 million gallons per year. Alongside that, REX held majority stakes in One Earth Energy and NuGen Energy—giving it control of key facilities while still spreading its exposure across geographies and operating teams.

That partnership model brought three big benefits. It was capital efficient: REX could participate in substantial production without paying for everything. It aligned incentives: operators with real ownership ran day-to-day execution, while REX supplied strategic capital. And it diversified risk: one bad plant, or one bad regional crop year, didn’t have to become an existential event.

To understand why this mattered, you have to understand the basic economics of ethanol. The core driver is the corn crush spread—essentially the gap between what a producer pays for corn and what it earns selling ethanol and co-products. In a modern plant, a bushel of corn yields about 2.8 gallons of ethanol, so economics often get framed around converting a corn price into an implied per-gallon input cost and comparing that to ethanol prices.

When corn is cheap and ethanol is strong, margins open up. When corn spikes or ethanol falls, margins get squeezed fast. Even when the spread turns negative, plants aren’t always instantly cash-flow negative because they can sell by-products like feedstock. But the pressure is real—and it tends to separate well-capitalized survivors from everyone else.

The 2012 Midwest drought was the stress test. Drought conditions reduced expectations for the corn harvest, and corn prices jumped roughly 35% from mid-June to late August. Over that same window, the spread between ethanol and corn prices fell by about $0.22 per gallon. The industry felt it immediately: some producers went bankrupt, and others idled plants.

REX didn’t have immunity from the cycle, but it did have something most competitors lacked: a strong balance sheet and the patience to avoid forced moves. When others were scrambling to plug holes, REX could keep operating—and in some cases, lean into distress rather than retreat from it.

That same discipline showed up in how REX treated its own stock. As its cash position strengthened, buybacks became a central lever. In fiscal first quarter 2025, the company repurchased 822,256 shares for total consideration of $32,727,232, a meaningful chunk of the company in a single quarter. It ended that period with $365.1 million in cash and no bank debt—dry powder that could fund opportunistic moves in ethanol, continued repurchases, or both.

VI. Navigating Volatility: The Lean Years (2012–2016)

The years after the 2012 drought were a gut-check for the entire ethanol industry. Corn got tighter and more expensive, gasoline demand softened, and the math that had looked so attractive on spreadsheets suddenly looked brutal in the real world. U.S. ethanol output slid from about 900,000 barrels per day in the first half of 2012 to roughly 815,000 barrels per day in the second half. A lot of producers didn’t just have a bad year. They ran out of runway.

For REX, this was the stretch where Rose’s structure stopped looking quirky and started looking smart.

Start with the balance sheet. REX didn’t face the liquidity spiral that took down weaker players. It could absorb a bad cycle without raising expensive capital, issuing stock at the wrong time, or making “strategic” moves that were really just survival tactics.

Then there was the ownership model. Because REX often invested alongside local operators rather than trying to run everything itself, plant-level firefighting—managing staffing, procurement, hedging execution, maintenance timing—was handled by teams whose full-time job was operating ethanol facilities. REX supplied capital and participated in distributions, but it wasn’t forced into learning hard operational lessons at the worst possible moment.

And crucially, it wasn’t all-or-nothing on one facility. With a portfolio across multiple plants and partners, problems could be contained. A tough crop year in one region, a hiccup at one plant, or a short-term basis issue didn’t automatically become a company-wide crisis.

Plenty of producers responded to rising corn prices by curtailing production, and some shut down entirely. REX’s plants kept running too, but they could dial back rates when it made sense—staying in the market, preserving relationships with corn suppliers and ethanol buyers, and avoiding the kind of stop-start whiplash that can make the next restart even more expensive. The partnership model mattered here: operators carried the operational burden of those decisions, while REX absorbed the lower cash flows without being dragged into a liquidity event.

This era also reminded everyone why ethanol isn’t just ethanol. The business lives and dies by co-products. REX’s plants produced dried distillers grains, modified distillers grains, and non-food grade corn oil. When ethanol margins got squeezed, those byproducts weren’t a rounding error—they helped keep plants viable. Distillers grains flowed into animal feed markets. Corn oil found demand in biodiesel and industrial uses. The more compressed the core spread became, the more valuable these secondary revenue streams looked.

The most telling part, though, was what Rose didn’t do. He didn’t chase growth for the sake of signaling confidence. He didn’t swing at desperate acquisitions to “win” a commodity market. He waited. And when he did deploy capital, it was often into share buybacks—quietly increasing per-share ownership while the industry was preoccupied with just staying upright.

For investors, the takeaway from 2012 through 2016 was simple: REX wasn’t built to avoid cycles. It was built to live through them—and still have the flexibility to act when the cycle turned.

VII. The Ethanol Renaissance & Capacity Expansion (2016–2020)

By 2016, the ethanol industry started to feel different. The mid-decade slump had done what slumps always do in commodity markets: it flushed out the overlevered and the unlucky. The plants that were still standing were generally better run, better capitalized, and operating in a market that had finally stopped getting worse.

And the demand story was getting a second act: exports.

The U.S. had become a net ethanol exporter for the first time in 2010. Then, in 2011, poor growing conditions in Brazil pushed up sugar prices—an important input for Brazilian ethanol—and the U.S. stepped into the gap, becoming the world’s leading ethanol exporter. That mattered because it cracked open a market that, for decades, had been almost entirely domestic and policy-driven.

Exports changed the psychology of the business. Instead of living and dying solely by U.S. blending mandates, producers now had another outlet when domestic demand flattened. And the irony was rich: Brazil, the country that pioneered ethanol fuel long before the U.S., became one of the places helping absorb U.S. supply.

REX used this period the way it tends to use periods like this: not for headline-grabbing empire-building, but for quiet accumulation alongside capable partners. As weaker competitors exited and surviving operators looked for capital, REX expanded its portfolio. It held interests in more than six ethanol production facilities, which together shipped roughly 730 million gallons of ethanol. But REX’s “owned” share of those gallons was closer to 300 million—a key distinction that captures the whole model. REX didn’t need to own every ton of steel and concrete to participate in scale. It needed stakes in the right plants, run by the right operators.

Meanwhile, the plants themselves kept getting better. Ethanol production isn’t just a policy story—it’s an engineering story, too. Over time, plants improved yields per bushel, used less energy, and got more value out of co-products. Those incremental gains matter because the entire business is built on the corn crush spread. When margins are tight, efficiency is the difference between writing checks and receiving distributions. REX benefited as its partner plants invested in those upgrades and the results flowed through.

Policy tailwinds also flickered back into view. During the Trump years, the administration pursued various biofuel adjustments, including expanding year-round sales approval for E15 in certain markets. E15 was still tiny early on—by the end of 2012, only eight fueling stations across Kansas, Nebraska, and Iowa were selling it—but the direction was important. If E15 grew, it offered one of the few ways to push past the “blend wall” that had capped ethanol’s penetration at standard E10 levels.

Then, just as the industry had regained its footing, COVID-19 hit.

When driving collapsed, ethanol got hit twice: gasoline demand fell, and ethanol demand fell with it. Plants idled across the country. But once again, REX’s advantage wasn’t that it could predict the shock—it was that it could survive it without panicking. While others scrambled for liquidity, REX’s strong balance sheet let it maintain stability and even look at opportunities as asset values temporarily fell.

And when the world reopened, the recovery was fast. Miles driven came back. Blending came back. The plants that had made it through emerged into a leaner competitive landscape with improved operating leverage. For REX, it was a familiar pattern by now: endure the downcycle, keep your options open, and be ready when the market swings back.

VIII. The Modern Portfolio: Carbon Capture & What's Next (2020–Present)

The next chapter of REX’s story is still being written, and it might end up being even more consequential than the original leap from retail into ethanol. Because this time, the pivot isn’t into a new product. It’s into a new profit engine layered on top of the one they already have: carbon capture and sequestration.

Since 2019, REX has been advancing a carbon sequestration exploratory project near its One Earth Energy plant. Carbon sequestration is exactly what it sounds like: capturing carbon dioxide (CO2), the most common greenhouse gas, and storing it underground to keep it out of the atmosphere.

What makes this more than a feel-good sustainability initiative is the economics. The 45Q tax credit under the Inflation Reduction Act was set at $60 per metric ton of CO2 for enhanced oil recovery and $85 per metric ton for saline storage. For an ethanol plant, that’s a big deal, because fermentation naturally produces CO2 as a byproduct. A typical plant generates roughly one pound of CO2 for every gallon of ethanol it produces. At the credit levels above, capturing that stream can add meaningful value per gallon—enough to turn a marginal plant into a very profitable one.

Carbon capture is becoming economically viable in a handful of sectors, including ethanol production, hydrogen production, and natural gas processing. But ethanol has a structural advantage: it produces a relatively pure stream of CO2. That purity matters. It makes capture materially cheaper than in settings where emissions are diluted and harder to separate. In other words, ethanol is one of the few places where carbon capture isn’t just theoretically possible—it can pencil out.

REX began working with the Illinois State Geological Survey under the Department of Energy’s CarbonSAFE initiative to evaluate whether sequestration near the plant could work and to run early testing. Geography helped. The One Earth plant sits in the Illinois Basin, an area with established geologic characteristics for storage. In 2021, a test well was drilled to a depth of approximately 7,100 feet, encountering almost 2,000 feet of Mt. Simon Sandstone—the basin’s primary carbon-storage resource.

By fiscal year 2024, REX had substantially completed construction of the capture and compression portions of the One Earth carbon capture and sequestration project at the company’s Gibson City, Illinois location. The remaining gating item is permission to inject and store the CO2. That runs through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Class VI injection well permitting process, which is still underway. Based on the EPA’s published timeline, the final permitting decision for the sequestration portion of the project is expected in January 2026.

This is not a small wager. Capital expenditures at fiscal year-end related to the One Earth carbon capture and sequestration project—plus a related expansion of ethanol production capacity—totaled $115.6 million, and the total budget is now estimated at $220–230 million. It’s a substantial investment, but if the project clears the remaining regulatory hurdles and performs as expected, it could reshape REX’s profitability profile.

Of course, the regulatory backdrop is moving too. In July 2024, Illinois instituted a moratorium on the permitting and construction of new carbon dioxide pipelines in the state for the shorter of two years or until new federal pipeline safety guidelines are approved and issued. That moratorium doesn’t directly impact REX’s on-site sequestration project, but it’s a reminder of the uncertainty surrounding the broader carbon capture buildout.

If REX succeeds here, the One Earth Energy plant moves toward its goal of reducing CO2 emissions and becoming a near-carbon neutral operation. That could open up new markets as well: exporting lower-carbon ethanol from a near-net-zero facility, improving long-term sustainability of the asset, and supporting positive local economic impact and job growth.

And looming behind all of this is a second, emerging tailwind: sustainable aviation fuel. Airlines can’t easily electrify, and they’ll need liquid fuels for decades. Ethanol can be used as a feedstock for SAF, and low-carbon ethanol can command premium pricing. If carbon capture makes One Earth meaningfully lower-carbon, it positions REX to participate in that demand shift as it develops.

IX. Capital Allocation Machine: The Real Story

At its core, REX American Resources isn’t primarily an ethanol company. It’s a capital allocation vehicle that happens to own stakes in ethanol plants. That distinction is the key to understanding why this little-known company has survived multiple industry cycles—and why it keeps showing up with dry powder when others don’t.

Stuart Rose’s philosophy fits neatly alongside the “outsider” CEOs William Thorndike wrote about: don’t optimize for revenue, market share, or headcount. Optimize for per-share value. In REX’s own words, the strength of its balance sheet provides the flexibility to pursue strategic opportunities while maintaining a disciplined approach to capital allocation.

You can see that mindset most clearly in how REX treats its own stock.

In the first quarter of 2025, REX repurchased about 822,000 shares for total consideration of $32.7 million, during a period when management believed the stock was undervalued. That pushed cumulative buyback activity to roughly 6.8% of shares outstanding since purchases were reinitiated in December 2024. After that activity, approximately 1,182,000 shares remained under the existing authorization—representing about another 7% of shares outstanding.

The mechanics are simple, but the restraint is uncommon. When REX generates more cash than it needs for operations and the right kind of reinvestment, it doesn’t feel compelled to go hunting for “strategic” acquisitions just to look busy. It buys back stock instead. That concentrates ownership for the remaining shareholders—and over time, it compounds. When the share count shrinks, every future dollar of earnings and cash flow matters more on a per-share basis.

After fiscal year 2024 results, the Board authorized an additional 1.5 million-share repurchase program, reinforcing that returning capital isn’t an afterthought here—it’s part of the core operating system. Management continues to evaluate potential acquisition opportunities, but only if they meet strict operational and financial criteria. Growth for its own sake doesn’t make the cut.

That discipline is reinforced by REX’s structure. The partnership model bakes in capital efficiency. By owning minority stakes across six ethanol plants rather than 100% of a smaller number, REX gets diversification without taking on proportionally larger capital needs. Plant-level debt is non-recourse to the parent, which helps contain the blast radius if any single facility hits trouble. And when partner distributions come in, they land at the holding company—where Rose can decide whether the best use is buybacks, additional investments, or simply holding cash until the odds get better.

And REX really does hold cash. The company reported roughly $346 million in cash and no bank debt, a level of liquidity that gives it tremendous optionality. It’s an unusually conservative posture—one that reflects hard-earned experience from more than one boom-and-bust cycle. When the right opportunity shows up, REX doesn’t need permission from a lender. It can just move.

X. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

To understand REX’s competitive position, you have to zoom out from any one plant and look at the structure of the ethanol industry itself. Michael Porter’s 5 Forces is a useful lens here, not because it turns the business into a spreadsheet, but because it explains why this sector tends to humble operators and reward disciplined owners.

Threat of New Entrants: MEDIUM-LOW

At first glance, ethanol looks like a classic commodity business that should be easy to enter: buy corn, run a plant, sell ethanol. In reality, the barrier is the plant. Building one takes serious capital—often $200 million or more for a facility at efficient scale—plus years of construction, commissioning, and hard-won operating know-how.

Then there’s the bigger constraint: market size. The Renewable Fuel Standard doesn’t just stimulate demand; it also effectively defines the playing field. RFS2 required 9 billion gallons in 2008 and scheduled 36 billion gallons for 2022, but conventional corn ethanol was capped at 15 billion gallons. That cap matters. If conventional ethanol demand has a ceiling, then new plants don’t expand the pie—they fight for slices.

Carbon capture changes the equation at the margin. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the expansion of the 45Q tax credit for carbon oxide sequestration in the Inflation Reduction Act can make ethanol plants more attractive investments than they’ve historically been, and that could pull new capital into the space. But the practical frictions are real: permitting, infrastructure, multi-year timelines, and the 2033 deadline to begin construction for projects to qualify. New entrants can show up, but they can’t show up overnight.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM-HIGH

In ethanol, the supplier story starts and ends with corn. Corn is the dominant input cost, and its price is set by global commodity markets. No single ethanol producer can negotiate its way out of that reality. When corn gets expensive, the economics tighten fast, because the crush spread compresses and the entire industry feels it.

REX does have one partial buffer: geography. Its plants sit in the heart of the Corn Belt—Illinois, Iowa, and South Dakota—where supply is deep and logistics are favorable. That doesn’t remove commodity risk, but it can reduce transportation friction and basis disadvantage versus plants that have to haul corn farther.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MEDIUM

On the demand side, ethanol has a built-in customer base: obligated parties under the RFS—oil refiners and gasoline blenders—have to blend renewable fuels to comply with EPA mandates. If they don’t, they face significant penalties. They can meet obligations either by blending required volumes or by purchasing RINs from others who blend more than required.

That legal structure creates a level of demand certainty most commodities don’t get. But it doesn’t turn ethanol into a specialty product. Ethanol is still largely fungible, with limited differentiation from one producer to another. Transportation matters—local supply can price differently than distant supply—yet most buyers still have options, and they can source from multiple suppliers.

Exports help here. The U.S. became a net ethanol exporter for the first time in 2010, and export volumes have grown significantly since. That second outlet doesn’t eliminate domestic dependence, but it does prevent obligated parties from being the only game in town.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-HIGH

The biggest long-term substitute risk isn’t another biofuel—it’s the slow erosion of gasoline demand itself. Electric vehicles are a structural threat to all liquid fuels. As EV adoption rises, total gasoline consumption declines, and ethanol blending volumes come down with it, regardless of mandates over the long run.

Within the renewable category, other biofuels—biodiesel, renewable diesel, and cellulosic ethanol—compete for policy attention and for the broader “low carbon” narrative. Advanced biofuels are held to stricter air pollution standards than conventional corn ethanol, and policy can tilt toward them.

The counterweight is sustainable aviation fuel. Aviation can’t easily electrify, and ethanol can be used as a feedstock for SAF. If SAF demand scales meaningfully, it could become a powerful new demand vector that offsets some of the long-term pressure from EVs.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

Ethanol is competitive because it’s a commodity and because the industry is still fragmented, even after years of consolidation. Large producers like POET, Valero, ADM, and Green Plains operate alongside dozens of smaller independents. When margins compress, the lowest-cost operators survive and the higher-cost ones get squeezed, idle, or disappear.

REX sits in a slightly different arena than most. Because it often owns minority stakes and partners with operators, it isn’t always competing plant-to-plant the way a pure operator does. In many cases, REX is competing for capital deployment opportunities—finding the right partners, buying stakes at the right time, and staying liquid enough to act when others can’t. That’s also why REX can invest alongside operators who might otherwise look like “competitors” on an industry chart: REX’s edge isn’t a consumer brand or a patented process. It’s the ability to be the right kind of owner at the right moment.

XI. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers framework is a way to ask a simple question: what, if anything, makes a company meaningfully harder to compete with over time? When you run REX through that lens, you get a clear answer—and it’s not the answer most people expect from an ethanol business.

Scale Economies: LIMITED

An ethanol plant has a “right size.” Once you get to an efficient facility—often in the neighborhood of 100 to 150 million gallons a year—bigger doesn’t automatically mean cheaper in any dramatic way. So while REX has a portfolio, it doesn’t get the kind of compounding cost advantage you’d see in software, semiconductors, or logistics at massive scale.

REX does get some lighter-touch benefits from being a sophisticated owner: better hedging habits, better balance-sheet management, and credibility in capital markets. Useful, but not decisive.

Network Effects: NONE

There’s no network effect in ethanol. Owning another plant doesn’t make the existing plants inherently more valuable. The product doesn’t get better because more people use it, and customers don’t get “locked in” to a producer the way they might with a platform.

Counter-Positioning: HISTORICAL (NOW FADED)

The coal-to-ethanol pivot was counter-positioning in the truest sense: REX moved into a new game that incumbents had a hard time playing.

Coal peers couldn’t credibly reinvent themselves into renewables without blowing up their shareholder base, culture, and operating DNA. And many ethanol pure-plays were built around operating and expanding plants—not around patient minority ownership, opportunistic buying, and per-share compounding.

But counter-positioning is often a window, not a fortress. That window helped create the opportunity. It doesn’t automatically create an enduring advantage now that REX is a known ethanol investor.

Switching Costs: NONE

Ethanol is fungible. Buyers can switch suppliers with little friction, and there’s no meaningful lock-in.

Branding: NONE

This is a B2B commodity. The end consumer filling up with E10 has no idea where the ethanol came from, and the buyer generally cares about price, logistics, and specs—not brand.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE

REX does have a few assets that aren’t instantly copyable. The One Earth site’s location in the Illinois Basin is helpful for carbon sequestration geology. And the relationships REX built with operators like One Earth and Big River didn’t happen overnight; trust and deal flow compound over years.

Add to that the company’s long track record under Stuart Rose, which gives it credibility that newer entrants have to earn. Still, none of this is truly “cornered.” With enough time and capital, others can find good geology and build strong operator relationships too.

Process Power: MODERATE-HIGH

This is the real one.

REX’s edge is not a patented process or a consumer brand. It’s an internal operating system: capital allocation discipline, a partnership model built around minority stakes, and the willingness to buy, sell, hold cash, or repurchase stock based on expected returns—not on a need to look busy.

Rose spent decades building that muscle. It shows up in how REX screens opportunities, how it structures risk, how it times entries and exits, and how it compounds per-share value through buybacks. Those habits can be copied in theory, but they’re hard to replicate in practice—especially inside organizations wired for operational growth or short-term optics.

Verdict: REX’s advantage comes primarily from Process Power in capital allocation, not traditional operational moats. That’s real—but it also makes leadership continuity unusually important. For REX, succession risk matters more than it would for a company whose advantage is structural and self-sustaining.

XII. The Bear vs. Bull Case

Bear Case:

Electric vehicles are the slow-moving threat hanging over every liquid fuel, and ethanol isn’t exempt. Most U.S. gasoline is blended with about 10% ethanol. If gasoline demand were cut in half over time because EVs take share, ethanol demand falls with it. The timing is debated. The direction isn’t.

Then there’s policy. The Renewable Fuel Standard is the demand floor the industry has been standing on since 2005. If a future administration decided to weaken or unwind the RFS, ethanol would lose the mandate-driven certainty that underpins the entire market. In any commodity business built around government rules, politics isn’t background noise—it’s a core risk.

The business is also structurally volatile. Ethanol economics live and die by crush spreads, and crush spreads can flip quickly. A drought across the Midwest can spike corn prices, squeeze margins, and turn a good year into a bad one in a matter of weeks. The 2012 drought was the reminder: even efficient plants can get pinched when corn moves against you.

Carbon capture, the big “next chapter” catalyst, has its own version of that volatility—only it shows up as regulatory and execution risk instead of commodity risk. The EPA’s Class VI injection well permitting process is still ongoing, and delays are common. Meanwhile, the One Earth carbon capture project’s budget has already risen to an estimated $220–230 million, a real signal that this isn’t a plug-and-play upgrade.

Finally, exports can be a pressure valve, but they can also be taken away. China trade tensions have disrupted ethanol flows before and could do it again. And because REX is relatively small, with limited analyst coverage and institutional ownership, the stock can become illiquid at exactly the wrong time—during market stress.

Bull Case:

If the bear case is “ethanol is a cyclical, policy-dependent commodity,” the bull case is that carbon capture changes the math so much it stops behaving like the old ethanol business.

The 45Q credit—$85 per metric ton for saline storage—can create a second profit stream layered on top of ethanol production. With advantageous geology and substantial construction progress at One Earth, carbon capture has the potential to add meaningful incremental value per gallon. For many developers, that tax credit isn’t a bonus; it’s the difference between a project that works and one that doesn’t.

The next demand unlock could be sustainable aviation fuel. Airlines can’t electrify in any meaningful way, so liquid fuels remain the path forward. SAF made from ethanol feedstocks could command premium pricing for a long time, and a lower-carbon ethanol profile—helped by carbon capture—puts REX in a better position to participate if that market scales.

Then there’s the part of the story that has nothing to do with ethanol at all: buybacks. REX has consistently treated share repurchases as a core tool, not a side project. With authorization remaining to buy back roughly another 7% of shares outstanding, continued repurchases can keep compounding per-share value—especially during periods when the market is undervaluing the business.

That undervaluation is central to the bull case. REX has roughly $315–365 million in cash and short-term investments against a market cap of around $1 billion. If you believe the ethanol plant stakes, carbon capture infrastructure, and even the remaining real estate value deserve more credit than the market assigns today, there’s a clear sum-of-parts argument.

And even in a polarized policy environment, energy security has a way of keeping biofuels relevant. Ethanol has deep political durability thanks to its agricultural constituency, and domestic fuel production has found support across administrations for reasons that go beyond climate messaging.

Finally, there’s optionality. REX’s real asset isn’t just a set of plants—it’s a playbook. This is a company that successfully pivoted from retail to energy and then built a durable, cash-rich ownership model inside a volatile commodity. If the world changes again, management has already proven it can change with it.

Key Metrics to Track:

For investors monitoring REX’s ongoing performance, three metrics matter most:

-

Quarterly Crush Spreads and Realized Margins: The corn crush spread is the industry’s heartbeat. Watching realized margins at REX’s consolidated plants helps you see whether the business is capturing the cycle—or getting left behind by it.

-

Share Count and Buyback Pace: REX’s strategy shows up in the denominator. If the share count is steadily falling, management is executing the core compounding engine that has defined the post-retail era.

-

Carbon Capture Project Milestones: With more than $115 million already invested and significant additional spending expected, One Earth’s carbon capture project is the biggest swing on the board. Permitting progress, construction completion, and the ability to actually capture, inject, and earn 45Q credits will determine whether this becomes a step-change in economics—or an expensive lesson in regulatory friction.

XIII. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

REX’s journey from a consumer electronics retailer to an ethanol producer isn’t just an energy-transition curiosity. It’s a case study in how to survive — and even thrive — through industries that change faster than your org chart can keep up.

Pivot Courage: Sometimes the most strategic move is to walk away. Stuart Rose watched consumer electronics turn into a scale and logistics war that regional players couldn’t win. Amazon changed how people shopped, Walmart changed what they expected to pay, and Best Buy changed the economics of big-box retail. When REX shut down its stores, it wasn’t “restructuring.” It was choosing a clean break over a slow, expensive decline — the kind most teams try to out-operate until it’s too late.

Know Your Superpower: REX’s edge wasn’t running a chain of stores, and it wasn’t even being the best day-to-day ethanol operator. It was capital allocation: spotting opportunities, structuring them intelligently, and staying disciplined enough to let compounding do its work. Rose brought the same M&A and investing mindset he developed at Niederhoffer, Cross and Zeckhauser into a totally different arena. The industry changed; the skill didn’t.

Structure Matters: REX didn’t try to own everything or control everything. Its minority partnership model let it pair capital with operating expertise. Operators ran the plants. REX provided strategic funding, oversight, and patience. That structure delivered capital efficiency, diversification across assets, and real incentive alignment — advantages that are hard to replicate if you’re forced into being both the operator and the balance sheet.

Timing Exits: Reinvention is rarely about making the perfect call at the perfect time. It’s about moving before you’re forced to. REX exited retail before the category fully collapsed, not because of luck, but because Rose recognized the warning signs and acted while the company still had options. Most management teams don’t move until the crisis arrives. By then, the decision isn’t strategy — it’s triage.

Patient Capital Wins: The 2012–2016 period punished ethanol producers, and plenty didn’t make it. REX did — largely because it wasn’t leveraged into desperation. Its balance sheet strength gave it the ability to stay rational when markets weren’t. The company ended the first quarter with cash, cash equivalents and short term investments of $315.9 million and maintained no bank debt. That conservatism can look inefficient during boom times, but it becomes a competitive advantage when the cycle turns.

Follow Government Incentives: REX’s biggest moves weren’t made in a vacuum; they followed policy gravity. The Renewable Fuel Standard — established in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 — created mandated demand by requiring oil refiners to blend increasing volumes of renewable fuels like ethanol. That predictability drove a wave of investment. Later, the 45Q expansion under the Inflation Reduction Act reshaped the economics of carbon capture. REX’s returns have been tied, in large part, to understanding what Washington was underwriting — and positioning early.

Capital Allocation Obsession: REX measures success differently than most operators. It’s not chasing production volume for bragging rights or revenue growth for the sake of scale. It’s focused on per-share value — through buybacks, balance sheet management, and selective investment. Beyond operations, REX treats delivering shareholder value as a core job, not a quarterly talking point. Over time, that mindset compounds in a way empire-building rarely does.

Small Can Be Beautiful: REX operates with 122 employees and gets minimal analyst attention. That obscurity is an asset. It allows flexibility, lowers the pressure to constantly “do something,” and reduces the gravitational pull of Wall Street narratives. Rose could make decisions based on expected returns, not on whether they’d play well on the next earnings call. Sometimes the best competitive position is simply being overlooked.

XIV. Epilogue & What's Next

As December 2025 drew to a close, REX American Resources was staring at another potential inflection point. After years of planning—and more than $100 million in capital spending—the company’s carbon capture buildout at One Earth was approaching the moment when it could finally move from “project” to “operations.”

On the ethanol side, the One Earth Energy expansion was on track for completion by mid-2025, lifting annual production capacity from 150 million gallons to 175 million gallons. The remaining swing factor on the carbon capture effort was regulatory: final EPA permitting for the sequestration component was still expected in January 2026.

Financially, REX was still doing what it has quietly done for years: put up steady results in a cyclical business. In third-quarter fiscal 2025, the company reported adjusted earnings per share of $0.71 versus the analyst estimate of $0.27, with revenue of $175.6 million compared to the consensus estimate of $169 million. “REX continues to deliver value to shareholders, marking our 21st consecutive quarter of positive earnings,” said Zafar Rizvi, Chief Executive Officer of REX.

In August 2025, REX took another shareholder-friendly step: its Board declared a 2-for-1 split of its common stock, effected as a 100 percent common stock dividend. Shareholders received one additional share for every share held on the record date, increasing shares outstanding from 16,528,787 to 33,057,574.

Meanwhile, the capital projects kept moving. By the end of the third quarter, REX had invested approximately $155.8 million in the carbon capture and ethanol expansion initiatives, still within the revised combined budget range of $220 million to $230 million. Based on the EPA’s published timeline, a final permitting decision for the sequestration portion was expected in June 2026.

There was also another policy lever coming into view: 45Z. The Inflation Reduction Act created a new Clean Fuel Production Credit, Section 45Z, originally available for 2025 through 2027. Under proposed rulemaking by the U.S. Department of the Treasury, it would work on a sliding scale—allowing credits to be earned based on a plant’s greenhouse-gas reduction below a 50 CI score threshold—ranging from $0.02 to $0.20 per gallon for non-SAF fuels, or from $0.10 to $1.00 per gallon if prevailing wage requirements are met. In periods when both credits are available, companies may elect either 45Q or 45Z.

Rizvi continued to frame the story the way REX always has: execution, patience, and per-share value. “The second quarter continued REX’s excellent track record in delivering value to shareholders,” he said. “Our ethanol expansion project remains on schedule for completion in 2026, further positioning us to deliver sustained long-term shareholder value.”

The biggest long-term question isn’t corn, or crush spreads, or even carbon credits. It’s leadership. Stuart A. Rose was appointed Executive Chairman of the Board and Head of Corporate Development in 2015, after serving as Chairman and Chief Executive Officer since the company’s incorporation in 1984 as a holding company. He stepped down as CEO in 2015, but his fingerprints are still all over the operating system—especially the capital allocation philosophy that has powered REX through multiple reinventions. Whether that culture endures after his eventual departure is the central uncertainty.

And that leads to the most interesting “what if” in the whole story: could REX exit ethanol the way it exited retail?

The possibility is real. If carbon capture proves transformative and ethanol assets re-rate materially, Rose has already shown a willingness to harvest value and redeploy capital rather than stay loyal to an identity. If EV adoption accelerates faster than expected and ethanol demand deteriorates, the same discipline that drove past exits could drive another one. What seems consistent, though, is the priority: REX has repeatedly chosen per-share value creation over preserving legacy business lines.

The next decade will almost certainly be messy. Biofuels policy could strengthen or weaken with politics. Carbon capture economics could exceed expectations—or get bogged down in permitting and infrastructure friction. EV adoption could accelerate or stall. In the middle of that uncertainty, REX remains a rare kind of public company: small, underfollowed, conservatively financed, and run—so far—like a vehicle built to wait for good odds, not good headlines.

XV. Outro & Further Reading

REX American Resources is rare in public markets: a company that has reinvented itself more than once, with each transformation driven less by panic and more by a cold-eyed willingness to redeploy capital toward better odds. From Stuart Rose buying a four-store electronics chain with $150,000 in savings to today’s ethanol portfolio with a real shot at carbon capture upside, the story is bigger than any one sector.

If you want to go deeper, here are the sources that best explain how REX thinks, what it owns, and what it’s betting on:

Primary Sources: 1. REX American Resources Annual Reports and SEC Filings (2006-present) - Stuart Rose’s letters to shareholders lay out the capital allocation philosophy with unusual clarity 2. Renewable Fuel Standard program documentation from the EPA - The RFS is the rulebook; without it, the ethanol business doesn’t make sense 3. Section 45Q tax credit legislation and Treasury guidance - The policy backbone for carbon capture economics 4. University of Illinois agricultural economics research on ethanol crush spreads - The cleanest technical grounding for how ethanol profits are actually made (and lost)

Industry Context: 5. Summit Carbon Solutions project documentation - Broader carbon capture infrastructure context, including the network tied to REX’s NuGen facility 6. Renewable Fuels Association industry reports - Industry perspective on markets, mandates, and the policy battlefield 7. EIA ethanol production and consumption data - The baseline numbers behind the cycle, from demand shocks to export trends

Capital Allocation Literature: 8. The Outsiders by William Thorndike - A useful lens for Rose’s long-term, per-share approach 9. Energy and Civilization by Vaclav Smil - The long arc of energy transitions, and why they never move in a straight line 10. Academic literature on corporate transformations and “pivot courage” - The research version of what REX has done in real time

The REX story isn’t finished. Carbon capture still hinges on permitting. Tax credit guidance continues to evolve. EV adoption will keep rewriting long-term demand expectations for liquid fuels. But as a case study in disciplined capital allocation, strategic flexibility, and the willingness to abandon legacy businesses rather than defend them, REX has already earned its place.

“REX continues to deliver value to shareholders, marking our 21st consecutive quarter of positive earnings,” CEO Zafar Rizvi said. “As our ethanol expansion and carbon capture projects advance, we are evaluating how best to leverage the 45Z tax credits to further enhance shareholder value. Most importantly, our team remains laser-focused on our core business, which continues to perform strongly and is well-positioned to deliver another profitable quarter and positive cash flow.”

From a Dayton hotel storefront selling radios in 1926 to carbon sequestration in the Illinois Basin nearly a century later, the throughline isn’t the product. It’s the decision-making. Rose understood early that the best businesses aren’t defined by what they make, but by how they allocate capital. The open question for investors now is whether that way of thinking is deep enough inside REX to outlast the people who built it.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music