REV Group Inc.: The Story Behind America's Specialty Vehicle Empire

How a private equity roll-up became the backbone of American emergency response

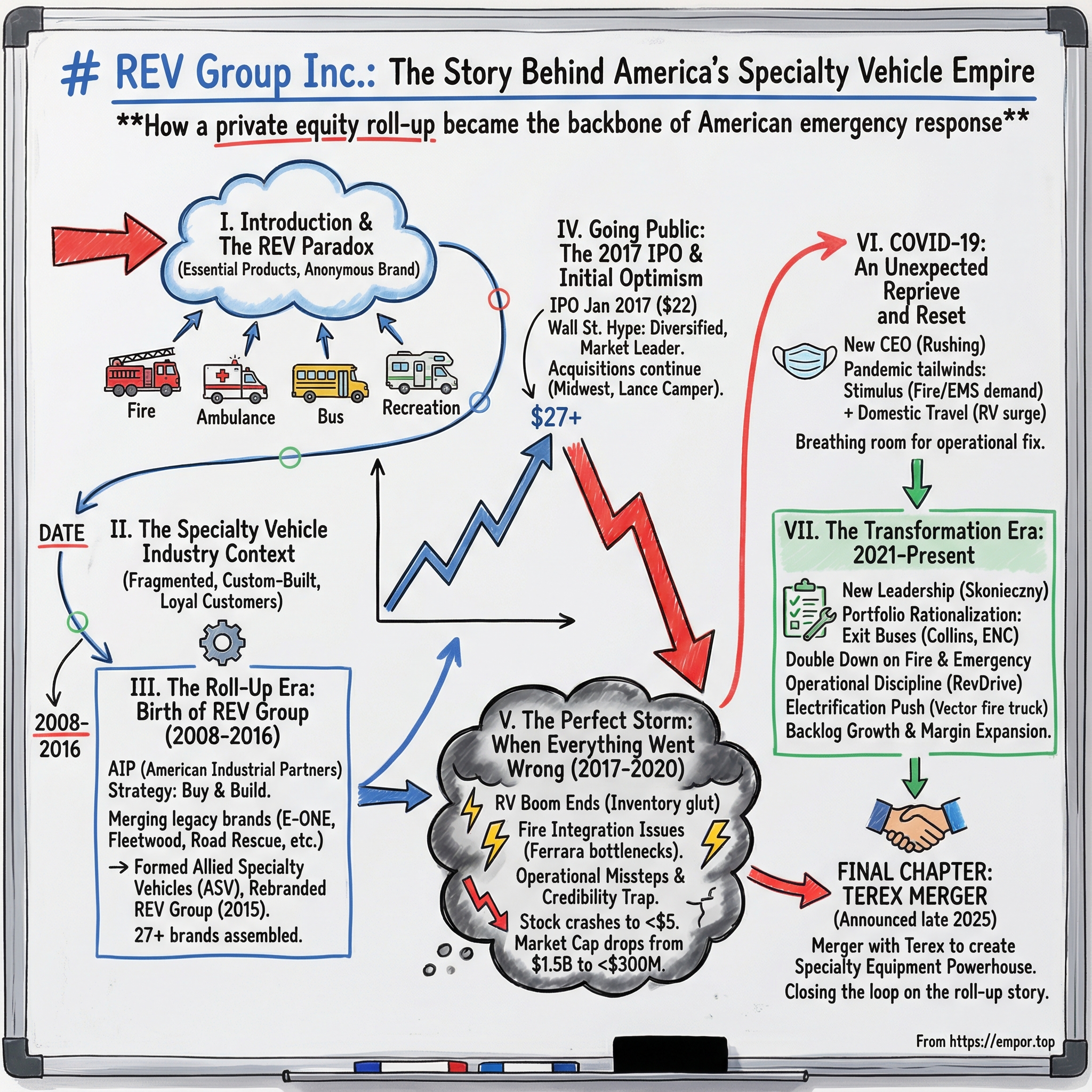

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: a fire engine screams down the street, lights strobing, horn blaring. Right behind it, an ambulance races to a cardiac call. Around the corner, a school bus swings up to the curb for the morning pickup. And out on the interstate, an RV family heads west toward Yellowstone.

Four vehicles. Four completely different missions. And, surprisingly often, one parent company behind them: REV Group.

In fiscal year 2024, REV Group produced roughly $2.6 billion in net sales. Yet ask the average investor to name the largest fire truck manufacturer in North America and you’ll likely get a blank stare. REV’s products show up in the moments that matter most—when seconds count—but the company itself trades with the anonymity of a business most people have never heard of.

At its core, REV is a designer and manufacturer of specialty vehicles, plus the parts and service that keep them running for years. It sells primarily in the U.S. across three segments: Fire & Emergency, Commercial, and Recreation. That spans everything from fire apparatus and ambulances to school and transit buses, to industrial vehicles like terminal trucks and sweepers, and finally to consumer leisure: recreational vehicles.

This isn’t the classic founder-led story where one person has an idea and wills it into existence. REV is something more modern—and more engineered. It’s one of the most ambitious private equity roll-ups in American industrial manufacturing: a deliberate stitching together of dozens of legacy, often family-run specialty vehicle makers into a single platform. The architect behind that consolidation was American Industrial Partners, or AIP.

And that’s what makes REV such a rich case study. It has all the upside of the roll-up playbook—scale, purchasing power, shared platforms—and all the risk—complex operations, proud legacy cultures, and execution that has to be near-perfect because the products are literally life-and-death. REV’s journey runs from private equity promise, to public market hype, to a brutal unraveling, and then to a hard-earned operational reset.

Here’s the arc: we’ll start in the 2008 financial crisis, when AIP began quietly assembling the building blocks of what would become REV Group. From there, we’ll move to the 2017 IPO. Then comes the perfect storm—operational missteps and cyclical exposure that crushed the stock by more than 80%. And finally, we’ll get to the turnaround years that set REV up for its next chapter, including a transformative merger announced in late 2025.

II. The Specialty Vehicle Industry Context

To understand REV Group’s strategy, you first have to understand the strange little corner of manufacturing it lives in. This isn’t Detroit. It isn’t millions of identical units rolling off a line. Specialty vehicles are low volume, high complexity, and usually built one customer at a time. That changes everything.

Take a fire truck. A passenger car is designed once and stamped out endlessly. A fire apparatus is closer to a commissioned piece of equipment. In 2013, a pumper might run about $500,000 and a ladder truck about $900,000. Since then, prices have climbed to roughly $1 million and $2 million. And it’s not just inflation. It’s because every department has its own reality: narrow streets, steep hills, water access, staffing models, and tactical preferences. The fire chief isn’t buying a vehicle so much as specifying a system.

That same dynamic shows up across the category. Ambulances have to satisfy state rules and local EMS requirements. School buses get configured around route needs and student populations. RVs might be the most consumer-facing, but even there the “product” is really a bundle of choices—hundreds of options that turn a chassis into someone’s version of a home on wheels.

Customization is expensive, but it’s also protective. It creates natural barriers to entry because the hard part isn’t just fabrication—it’s design, engineering, testing, and the process knowledge that comes from building these things over and over without getting anyone hurt.

E-ONE is a good example. Founded in 1974 by an industrial engineer, it developed the first modular, extruded aluminum fire truck body. That structure went through extensive testing beyond industry standards, aimed at improving safety and dependability for first responders. Innovations like that aren’t overnight wins. They’re the result of years of engineering—and once you have that expertise, it’s not easily copied.

Then there’s the customer side, which is its own moat. Fire departments don’t switch manufacturers casually. They build relationships with local dealers. They train mechanics on specific systems. They standardize fleets so maintenance is faster, parts inventories are simpler, and the whole operation is less fragile when something breaks at 2 a.m. So when a chief orders from E-ONE or Ferrara, they’re not just picking a spec sheet—they’re leaning on years, sometimes decades, of institutional trust.

Municipal procurement reinforces that stickiness. Yes, there are formal bids. But specifications can be written in ways that tilt toward what a department already knows works, and the sales cycle is long enough that incumbents can build relationships over years, not weeks. Several REV brands helped pioneer their categories, and many of those names have been around for more than half a century.

Historically, that world was incredibly fragmented: family-owned shops, regional champions, proud legacy brands. Many had loyal customers but not the scale to invest in modern manufacturing tech, enterprise resource planning systems, or sustained product development. That gap—strong demand and brand loyalty on one side, limited operational scale on the other—created the opening private equity would eventually drive a truck through.

For long-term investors, specialty vehicles can look attractive: long replacement cycles (fire trucks often stay in service 15 to 20 years), regulation that keeps fly-by-night entrants out, and municipal customers whose demand is constrained but relatively steady.

The catch—and the lesson REV would learn the hard way—is that “specialty vehicles” isn’t one market. Cyclicality varies wildly by segment. And when you own a portfolio of very different businesses, operational excellence isn’t optional. It’s the whole game.

III. The Roll-Up Era: Birth of REV Group (2008-2016)

American Industrial Partners, or AIP, wasn’t a flashy, Silicon Valley-style private equity firm. It was an old-school industrial shop, founded in 1988 by Theodore Rogers and Richard Bingham, focused on buying manufacturing businesses in the U.S. and Canada. AIP said its edge wasn’t financial engineering. It was execution: cut debt, improve operations, and—crucially—leave day-to-day leadership largely in place with a relatively hands-off management style.

If you were looking for an industry where that playbook could work, specialty vehicles were a bullseye. The space was fragmented, full of proud legacy brands with loyal customers, and packed with businesses that could benefit from scale—without losing what made them special.

The company that became REV started taking shape around the 2008 era. At first, it operated as Allied Specialty Vehicles, or ASV, and by 2010 it was officially formed as a platform.

ASV was created in 2010 by merging four AIP-owned businesses: Collins Industries, E-ONE, Halcore Group, and Fleetwood Enterprises. Each brought a different piece of the puzzle—buses, fire apparatus, and, importantly, the beginnings of an RV footprint.

Within that mix, E-ONE stood out. Founded by Bob Wormser in 1974, it began in his garage with a modular, extruded aluminum fire apparatus body—an engineering-driven approach to safety and durability that helped define the brand. By the time ASV came together, E-ONE had become one of the best-known names in fire apparatus, anchored by deep relationships with municipal fire departments across the country. Decades later, it marked its 50th anniversary in Ocala, Florida, having grown to more than 1,000 employees—an indicator of just how big this “niche” really was.

And then the roll-up machine really started moving.

In September 2010, ASV acquired the assets of ambulance manufacturer Road Rescue from Spartan Motors. In May 2013, REV acquired SJC Industries from Thor Industries, a builder of ambulances sold under the McCoy Miller and Marque brands.

The Recreation segment, meanwhile, was built the way a lot of private equity platforms get built: by being ready when distress creates an opening. In 2013, ASV announced it was buying RV assets from Navistar International, including Monaco, Holiday Rambler, R-Vision, and the Beaver and Safari brands. These were household names in the RV world, with real dealer networks and decades of brand equity—picked up at a time when the industry was still bruised from the post-2008 downturn.

The bus side expanded that same year. In August 2013, ASV announced the purchase of Thor Industries’ bus businesses, including ElDorado Motor Corp., National Coach, Champion Bus, and Goshen Coach—broadening the platform beyond emergency response and into commercial and municipal transportation.

Then, in 2014, AIP brought in a CEO who had done this before at a much bigger scale: Tim Sullivan.

Sullivan had previously run Bucyrus, the South Milwaukee mining equipment manufacturer, helping grow it to nearly $4 billion in annual revenue before it was sold to Caterpillar in 2011. He also had public markets credibility—he’d overseen a standout U.S. IPO in 2004 and, between 2004 and 2010, helped grow shareholder value by more than 1,500%. His arrival signaled a shift: this wasn’t just an M&A platform anymore. It was being built to go public.

The acquisition pace continued. In April 2016, REV acquired fire truck manufacturer Kovatch Mobile Equipment Corp. Later that year, it bought Ferrara Fire Apparatus and Class C motorhome manufacturer Renegade RV.

Ferrara, founded in 1979 by Chris Ferrara and based in Holden, Louisiana, was a major prize in fire. As of 2017, it employed around 450 workers and generated about $165 million in annual sales. More than the numbers, Ferrara brought something REV wanted badly: a fiercely loyal customer base and a stronger footprint in the southern U.S.

Around this time, ASV also made a symbolic move to match the company it was becoming. In November 2015, it rebranded from Allied Specialty Vehicles to REV Group—a cleaner, platform-style identity that sounded less like a collection of businesses and more like a single enterprise ready for the public markets.

By 2016, REV had assembled 27 principal vehicle brands across fire apparatus, ambulances, school and transit buses, terminal trucks, street sweepers, and recreational vehicles. It was, on paper, the most comprehensive specialty vehicle platform in North America.

But the roll-up era always has a second story running underneath the first. Buying strong brands is the easy part. The hard part is getting dozens of factories, systems, and cultures—many built over generations—to operate like one company. And that integration challenge would define what came next.

IV. Going Public: The 2017 IPO and Initial Optimism

By January 2017, the roll-up story had its natural next step: take it public.

On January 26, 2017, REV priced its initial public offering at $22.00 per share, selling 12.5 million shares. The stock was approved for listing on the New York Stock Exchange and began trading the next day under the ticker REVG.

The offering raised $275.0 million in gross proceeds, or about $254.4 million net after underwriting discounts and IPO expenses. REV used those proceeds to pay down a portion of its existing debt—exactly what public-market investors like to see from a newly listed industrial roll-up: de-risk the balance sheet, then grow.

The underwriting lineup didn’t hurt, either. Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Baird led the deal. The message was clear: Wall Street was willing to vouch for this platform.

And, at first, the market bought the story. Shares opened at the $22 IPO price, jumped more than 13%, and closed the first day at $25. The momentum continued into the following week. By October 2017, the stock was trading at $27.56—nearly a 25% gain from where it came public.

The pitch was straightforward and easy to like. REV wasn’t a one-product bet; it sold into three end markets—Fire & Emergency, Commercial, and Recreation. It built customized vehicles for essential services like ambulances, fire apparatus, school buses, mobility vans, and municipal transit buses. It made industrial and commercial vehicles like terminal trucks, shuttle buses, and street sweepers. And it had consumer leisure exposure through recreational vehicles and luxury buses. In other words: a portfolio of specialty vehicles with both “need-to-have” and “nice-to-have” demand drivers.

Even pop-market commentary picked up on the appeal. Jim Cramer talked about the breadth of what REV made—school buses, ambulances, fire trucks, street sweepers, mobility vans, RVs—but lingered on a different detail: Tim Sullivan. This was the former Bucyrus CEO who sold his company to Caterpillar near the top of the commodity cycle. Investors heard “experienced operator with good timing,” and they leaned in.

REV also had the kind of market-position sound bites that play well in an IPO roadshow. The company was No. 1 in ambulances by market share and No. 2 in fire apparatus. In a fragmented industry, that reads like a moat.

Then came the first set of public-company results. In its first quarterly earnings report after the IPO, Milwaukee-based REV reported consolidated net sales of $442.9 million, up 19% year over year. It posted a net loss of $13.3 million, or $0.26 per share, driven by what it described as one-time items tied to the January 27 IPO. On an adjusted basis, net income was $5.7 million, or $0.11 per share, up from $3.9 million, or $0.07 per share, a year earlier.

The company said sales growth was driven by Fire & Emergency and Recreation, plus a strong quarter in higher-margin aftermarket parts—up 10.4% from the prior year’s first quarter. “Sales growth was driven by strong end-market demand, gains in market share and our new product initiatives,” Sullivan said.

Management’s initial outlook for fiscal 2017 reinforced the optimism: expected revenue of $2.25 billion to $2.35 billion, net income of $40 million to $43 million, and adjusted EBITDA of $150 million to $155 million.

And REV didn’t slow its deal engine just because it had crossed the IPO finish line. In April 2017, it acquired sprinter van manufacturer Midwest Automotive Designs. In January 2018, it acquired Lance Camper in California—expanding the RV portfolio and signaling confidence in Recreation’s growth.

From the outside, it looked like the classic roll-up script playing out perfectly: consolidation, scale, a clean public listing, strong early trading, and bolt-ons to keep momentum going.

But the script always has a second act. Buying great brands and telling a good story gets you to the IPO. Running dozens of factories like one company—and surviving the first real downturn—decides what happens after. That test was closer than anyone wanted to believe.

V. The Perfect Storm: When Everything Went Wrong (2017-2020)

The collapse came fast. In less than three years after the IPO, REV’s stock went from post-IPO highs above $27 to below $5—wiping out more than 80% of shareholder value. And it wasn’t one isolated mistake. It was multiple problems hitting at once, each making the others worse, and together exposing just how fragile REV’s “diversified, defensive” story really was.

The first domino was Recreation—the RV business that had helped power the IPO narrative. The RV industry surged through 2017 as baby boomers retired and more consumers leaned into road-trip culture and “glamping.” REV built to meet that demand. But the boom didn’t last.

By 2018, dealer lots were jammed with unsold inventory. Retail demand cooled. And when dealers stop ordering, RV manufacturers don’t just slow down—they get squeezed. Pricing pressure shows up immediately, and margins go with it. The segment that was supposed to round out the portfolio turned out to be the opposite of defensive.

On paper, REV’s mix looked elegant: pair a highly cyclical consumer business with steadier, public-service vehicle demand. When the economy tightens, people buy fewer RVs, but fire departments still need fire trucks and EMS still needs ambulances. The theory was compelling. The practice was messier—because REV didn’t just own different end markets; it owned a complicated web of plants, systems, and brands that had to run flawlessly for that portfolio to work.

Then the second shoe dropped: Fire, the segment that was supposed to be REV’s stable anchor, started wobbling too.

The first public crack showed on March 7, 2018, when REV disclosed that margins and growth rates had slipped. The next day, the stock fell 12%. That was painful, but still survivable—until June 6, 2018, when REV cut its fiscal-year earnings guidance sharply and acknowledged lower-than-expected sales in certain product categories. More important than the cut itself was what it triggered: a credibility problem with Wall Street that would linger.

A big part of the fire-side turmoil traced back to integration—especially Ferrara. Strategically, Ferrara was exactly what REV wanted: a strong brand, loyal customers, and a powerful presence in the southern U.S. Operationally, blending it into a larger platform proved far harder. Bottlenecks surfaced. Quality issues followed. Deliveries stretched out longer than customers expected.

And for a fire department, a delivery delay isn’t an inconvenience—it’s an operational problem. These are organizations that plan staffing, training, and fleet readiness around the arrival of a specific truck built to a specific spec. When that truck shows up late, or shows up with issues, the frustration is immediate, and the reputational damage sticks.

From there, the problems spread. Inventory management broke down, pushing working capital higher. ERP implementations across multiple legacy businesses disrupted operations instead of streamlining them. Leadership turnover added instability at exactly the wrong moment, with key executives leaving while the company was trying to get control of the situation.

By April 16, 2020, REVG hit an all-time low of $3.50. At the post-IPO peak, the company’s market capitalization had topped $1.5 billion. Now it had fallen below $300 million—an ugly result for a business that still had more than $2.5 billion in annual revenue and leading positions in markets that genuinely mattered.

The lawsuits arrived on schedule. A complaint filed against REV’s officers and directors related to the January 27, 2017 IPO alleged breaches of fiduciary duties, arguing the company had told investors to expect continued margin growth and highlighted “efficient manufacturing facilities,” even as its operations were not performing as effectively as portrayed. The accusation, in essence, was that optimism outlived reality—and management kept forecasting strength while the underlying machine was already slipping.

If you’re studying REV—or any industrial roll-up—this 2017 to 2020 stretch is the cautionary chapter. Consolidation can create scale, but it also creates complexity that can overwhelm management. A portfolio can diversify demand, but it can also multiply execution risk. And being a market leader in a fragmented industry doesn’t guarantee pricing power, smooth operations, or higher margins.

In this business, execution isn’t a detail. It’s the product.

VI. COVID-19: An Unexpected Reprieve and Reset

March 2020 delivered REV’s lowest stock price—and, almost simultaneously, the leadership change that would define the reset. The company announced that Timothy Sullivan was departing as CEO and stepping off the Board. In his place, the board appointed Rodney N. Rushing as Chief Executive Officer, effective March 23, 2020.

Rushing arrived with a very different kind of résumé for the job REV needed next. Before REV, he served as President, Building Solutions North America at Johnson Controls, a business with about $9 billion in revenue and roughly 30,000 employees. He’d spent three decades at JCI leading both product and service operations—exactly the kind of operational, systems-driven background REV had been missing as its roll-up complexity caught up with it.

The timing looked brutal: a new CEO walking into a manufacturing-heavy business just as a global pandemic slammed the brakes on the economy. But COVID ended up doing something counterintuitive for REV. It created disorder in the short term—supply chain disruptions, workforce constraints, and even more operational strain. And then it handed the company two tailwinds it couldn’t have scripted.

The first was policy. Federal stimulus money flowed to state and local governments through the CARES Act and other programs. For many municipalities, that funding became a pressure release valve. Fire departments and EMS agencies that had been delaying big-ticket purchases suddenly had room in the budget again, and REV’s fire and emergency backlog began to rebuild.

The second tailwind was cultural. With air travel curtailed and hotels feeling risky, Americans rediscovered domestic travel—often in the most self-contained way possible. RV demand surged as families looked for a vacation that didn’t require airports, crowds, or shared elevators. The Recreation segment that had helped sink the narrative in 2018 and 2019 suddenly had real wind at its back.

With that breathing room, Rushing started doing the unglamorous work that actually turns industrial companies around: simplify, consolidate, and invest where it matters. REV announced that plants in Nesquehoning and Roanoke, Virginia would close in 2021, with KME production shifting to Holden, Louisiana. The Nesquehoning plant ultimately closed in April 2022.

The point wasn’t just cost cutting. Consolidating the manufacturing footprint reduced duplicate overhead and made it easier to modernize the plants that remained. In November 2021, REV announced plans for a $7.46 million expansion of Ferrara’s Holden, Louisiana manufacturing facility—an example of the new posture: fewer locations, better execution.

REV also began trimming the portfolio. In May 2020, it sold its shuttle bus brands Champion, Federal Coach, World Trans, Krystal Coach, ElDorado, and Goshen Coach to Forest River. It was an early signal that the company was done trying to be everything in specialty vehicles, and was starting to focus on where it believed its strengths were most defensible.

At the same time, REV doubled down on fire apparatus in a big way. In February 2020, it announced the acquisition of Spartan ER, a subsidiary of The Shyft Group (then Spartan Motors), for $55 million. Before the deal, Spartan reported $253 million in revenue for the year ending in September 2019. The acquisition closed during the height of pandemic uncertainty, and it materially expanded REV’s fire portfolio with a strong Midwest-oriented brand and manufacturing capability.

The Spartan deal brought in Spartan Emergency Response and its subsidiaries: Spartan Fire Apparatus and Chassis, Smeal Fire Apparatus, Ladder Tower, and UST. Collectively, they design, manufacture, and distribute custom emergency response vehicles across Asia, North America, and South America.

By 2021, the market started to believe the turnaround was real. The stock recovered from its pandemic lows and traded in the $15 to $20 range—still below where it debuted, but a world away from “this might be broken forever.” The underlying message was simple: REV’s brands and end markets hadn’t disappeared. The company just needed to prove it could run them.

That’s the key takeaway from this period. In essential categories—fire, EMS, school transportation—market-leading franchises don’t usually evaporate. But when operational missteps pile up, the only way back is slow: better leadership, fewer distractions, and execution that matches the mission-critical nature of the product.

VII. The Transformation Era: 2021-Present

By early 2023, REV’s reset entered a new phase—and it started with another leadership handoff.

On January 27, 2023, REV appointed CFO Mark Skonieczny as Interim Chief Executive Officer. Rod Rushing stepped down as President and CEO and resigned from the Board. “On behalf of the Board of Directors, I want to thank Rod for his dedication and contributions to REV Group over the past three years,” said Chairman Paul Bamatter, crediting Rushing with guiding REV through COVID-19, rapidly rising inflation, and supply chain disruptions while positioning the company for the long term.

Skonieczny had joined REV in June 2020 as Chief Financial Officer after 17 years at Johnson Controls, where he held a variety of finance roles. After several months as interim CEO, REV made it permanent: on May 18, 2023, the company appointed Skonieczny as President and Chief Executive Officer, and he also joined the Board.

With Skonieczny in the top job, the portfolio rationalization accelerated. In January 2024, REV announced it would exit bus manufacturing. The company reached an agreement to sell its Collins school bus brand to Forest River for $303 million, and later sold its ENC transit bus division to Rivaz Inc.

Over four years, REV executed what amounted to a shrink-to-grow strategy. By fiscal 2024, it had exited both bus businesses (Collins Bus and ENC), and in 2025 it divested Lance Camper. What remained wasn’t a loose collection of brands chasing every corner of “specialty vehicles.” It was a tighter, clearer identity: Specialty Vehicles—fire apparatus, ambulances, and terminal trucks—built for municipal and industrial customers, supported by multi-year backlogs that, in some cases, stretched two to three years.

At the same time, REV leaned into a theme that’s starting to reshape nearly every vehicle category: electrification. REV Fire Group’s Vector is positioned as the first full-electric fire truck in North America. It was ordered by departments in Charlotte, North Carolina; Varennes, Quebec; Mesa, Arizona; and Toronto, Canada, and it was used at the 2023 Daytona 500.

E-ONE, a REV subsidiary, said in November 2021 that it was building an all-electric Vector for the Mesa Fire and Medical Department in Mesa, Arizona. According to E-ONE, the Vector offered the industry’s longest electric pumping duration, with the ability to operate four hose lines for four hours on a single charge.

The pitch for Vector was simple: do the full job, electrically. The electric motor replaces the diesel engine and can drive the pump or the rear axle in a split-shaft configuration. And it’s designed around many of the same components used on diesel-driven fire apparatus—an important point in an industry that values serviceability and familiarity almost as much as innovation.

Under the hood of the turnaround, REV pointed to process improvements translating into results. The company’s RevDrive business system delivered what it described as 28% incremental margins in Specialty Vehicles—above the 20–25% range it had guided to—through lean manufacturing, workforce training, and strategic sourcing.

Even the backlog story had a “getting healthier” interpretation. REV reported a $4.3 billion Specialty Vehicles backlog, and while it declined 6% year over year in unit terms, the company framed that as improved throughput: delivery times shortened by two months, suggesting REV was converting orders to revenue more efficiently rather than simply losing demand.

Financial flexibility followed. With leverage under 0.4x and $247 million of availability under its asset-based lending facility, REV returned $118 million to shareholders year-to-date through buybacks and dividends, while also funding a $20 million capacity expansion.

Then came the clearest signal yet that REV’s transformation had changed how the market viewed the company.

On October 30, 2025, Terex Corporation and REV Group announced a definitive merger agreement: a stock-and-cash transaction intended to create a leading specialty equipment manufacturer. The companies said the combined portfolio would span emergency, waste, utilities, environmental, and materials processing equipment—end markets they characterized as resilient and relatively low cyclicality. They also emphasized the combined company’s substantial U.S. manufacturing footprint and projected $75 million of run-rate synergies by 2028, with about half expected within 12 months of closing.

Under the terms of the agreement, REV shareholders would receive 0.9809 shares of the combined company plus $8.71 in cash per REV share, or $425 million in total cash consideration. On a pro forma, fully diluted basis, Terex shareholders would own about 58% of the combined company and REV shareholders about 42%.

REV described the deal as valuing the transaction at $3.18 billion, with implied consideration of $63.62 per REV share—a 6.07% premium to REV’s last closing price. The companies expected the transaction to close in the first half of 2026, subject to shareholder approvals, regulatory clearance, and other customary closing conditions.

For long-term investors, this period is the reminder that industrial turnarounds don’t come from one bold announcement. They come from years of narrowing focus, rebuilding operating discipline, and earning back trust—one delivery, one plant improvement, one quarter at a time. By the time REV reached the Terex merger agreement, it looked nothing like the struggling roll-up of 2019. It was leaner, more focused, and generating the kind of cash flow that would have seemed out of reach in the darkest days.

VIII. The Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand REV Group, you have to stop thinking of it as one company and start thinking of it as a portfolio of very different economics that just happen to share a parent.

Over the last few years, the center of gravity has shifted hard toward what REV now calls Specialty Vehicles. This is the fire-and-ambulance engine of the company, and it’s become the core identity REV wants the market to see. In the fourth quarter, Specialty Vehicles was the main growth driver, with net sales rising to $507.4 million from $439.9 million a year earlier. Adjusted EBITDA climbed to $70.5 million, with margin improving to 13.9% from 11.4%.

Inside that segment, REV’s strategy is simple, but very deliberate: keep the brands separate.

Fire chiefs are not choosing between generic products. They’re choosing between philosophies, regional loyalties, dealer relationships, and decades of lived experience. So REV Fire Group operates as a stable of brands rather than one consolidated nameplate: E-ONE, KME, Ferrara, Spartan Emergency Response, Smeal, and Ladder Tower. In a category where customers often won’t cross-shop “the other guy,” a multi-brand portfolio isn’t redundancy—it’s coverage.

KME is a good example of how deep these brands run. The company has been around since 1946 and builds custom apparatus for municipal, federal, and wildland/urban interface markets across the U.S. It’s also known for its steel aerials, designed around a “best in class” steel structural safety factor of 2.5 to 1.

Ambulances follow the same playbook. REV keeps multiple names in market—Horton, AEV, Road Rescue, Wheeled Coach, and Leader—covering Type I, Type II, Type III, and medium-duty vehicles for fire departments, municipalities, and private operators around the world.

Wheeled Coach is one of the most telling origin stories in the portfolio. It was founded in 1975 by Robert Collins Sr. in downtown Orlando, starting with five employees building mobility vans and Type 2 ambulances. Today, it employs more than 700 people and has produced and delivered over 50,000 ambulances.

Then there’s Recreation: smaller today than it once was, and structurally more cyclical, but still a real part of the story. REV’s RV lineup runs from Class B custom sprinter vans to high-end Class C and Super C motorhomes, all the way up to luxury Class A motor coaches. REV Recreation Group leans heavily on its dealer and distribution footprint and on recognizable brands like American Coach, Fleetwood RV, Holiday Rambler, Renegade RV, and Midwest Automotive Designs.

Across the company, the underlying revenue model is built around customized manufacturing. These aren’t off-the-lot purchases. Each vehicle is configured to the customer’s specs, and in fire apparatus, lead times can stretch 12 to 24 months from order to delivery. That long build cycle creates two things at once: visibility, because you can see revenue coming through the backlog—and risk, because long-duration builds demand working capital and leave the manufacturer exposed to input cost inflation midstream.

REV exited fiscal 2025 with a $4.4 billion backlog, which the company described as roughly two years of production for fire and emergency vehicles.

And then there’s the piece public markets often underappreciate: the installed base. The parts and service aftermarket brings in recurring revenue at higher margins than new vehicle sales. Fire apparatus often stays in service for 15 to 20 years, which means every truck REV delivers can turn into a long tail of parts, service, and refurbishment work.

Competition in fire is concentrated, and it’s intense. REV Group, Oshkosh, and Rosenbauer are estimated to control roughly 70% to 80% of the market. REV says it holds about a third of fire truck manufacturing share—more than any other single company—with independents making up the remainder.

That kind of concentration has drawn political scrutiny, too. Senator Warren pointed out that over the last 20 years, “private equity has been buying up independent fire truck manufacturers to the point that today, just three companies own approximately 80% of all fire truck manufacturers.”

REV argues that scale cuts both ways for customers. The company has said it increased production throughput for fire and emergency vehicles by almost 30% over the last two years, aiming to shorten delivery times and help departments get trucks in service faster.

Put it all together and the model becomes clear: REV has real strengths where seconds count—brand equity, regulatory know-how, deep customer relationships, and hard-earned manufacturing expertise. The tradeoff is that it still carries the inherent complexity of running a multi-brand industrial platform, and it has historically had exposure to a much more volatile consumer business in RVs.

IX. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To see where REV is truly strong—and where it’s exposed—it helps to run the business through two classic strategy lenses: Porter’s 5 Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers. The big takeaway is that REV doesn’t have one competitive position. It has three. Fire and emergency is where the moats live. RVs are where the ground moves under your feet.

Porter’s 5 Forces Assessment

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In fire apparatus, the barriers aren’t just capital and machinery—they’re trust, time, and regulation. You’re selling mission-critical equipment to customers who can’t afford “good enough.” REV’s brands have decades of credibility, and innovations like E-ONE’s modular aluminum body weren’t just marketing claims; the structure underwent testing beyond industry standards, with safety and dependability as the point.

A new entrant has to clear years of approvals, build a dealer and service network, and then convince risk-averse fire chiefs to bet their department’s readiness on an unproven name. In RVs, entry is easier—but meaningful scale still requires distribution, dealer relationships, and brand recognition.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE-HIGH

The chassis supply chain is one of REV’s structural pressure points. Across multiple product lines, the company relies heavily on Ford and Freightliner. When chassis availability tightens—as it did in the 2021–2023 shortage—production gets capped, schedules slip, and suppliers gain leverage.

And it’s not just chassis. Key components like pumps and aerial devices come from a relatively small group of specialized suppliers, which can limit REV’s flexibility when the supply chain is stressed.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

In Fire & Emergency, buyers are budget constrained, but they can’t really “substitute away” from a fire truck or ambulance. Municipal procurement introduces formal bidding, yet in practice, specs often reflect what a department already runs, and relationships matter because departments live with these vehicles for decades.

In RVs, the power dynamic shifts. Dealers are more consolidated and more sensitive to inventory levels. When retail demand cools, dealers push back fast—on pricing, on volumes, and on who carries the risk of an overstuffed lot.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

There’s no substitute for a fire truck in a structure fire. Electrification changes the drivetrain, not the job. Ambulances also have limited substitution risk because patient transport is regulated and requires purpose-built equipment.

RVs are the exception. They compete against every other way a family might spend leisure dollars: hotels, vacation rentals, flights, cruises. That’s a very different battlefield than municipal emergency response.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE-HIGH

Fire apparatus is concentrated and fiercely competitive. A handful of major players go head-to-head for municipal contracts, and the competition is less about glossy features and more about the things that keep chiefs up at night: quality, delivery reliability, service, and total cost over the life of the vehicle.

Consolidation has also drawn scrutiny. Senators Hawley and Kim sent a letter to the CEOs of REV Group, Oshkosh Corp., and Rosenbauer America arguing that industry consolidation has contributed to significant delivery delays. Even if demand is steady, rivalry stays intense because reputation and lead times can swing wins and losses in a bid-driven market.

Hamilton’s 7 Powers Assessment

Scale Economies: MODERATE

REV gets some real benefits from scale—purchasing leverage, shared overhead, and the ability to absorb fixed costs across a larger footprint. But customization puts a ceiling on how far scale alone can carry you. In fire, each truck is still close to a one-off build.

Network Effects: NONE

This is a manufacturing business selling to municipalities and dealers. The product doesn’t get more valuable because more people own one.

Counter-Positioning: NONE

REV isn’t running a business model that competitors can’t copy without breaking themselves. It largely competes the way the industry competes.

Switching Costs: MODERATE-HIGH

This is one of REV’s most durable strengths, especially in fire. Departments standardize fleets for a reason: training, maintenance routines, parts inventory, and service relationships all get simpler. Switching manufacturers can mean real operational disruption.

And because a fire truck can stay in service for 15 to 20 years, the switching costs don’t just show up at purchase—they echo through decades of aftermarket parts and service.

Branding: MODERATE-HIGH

In fire, brands aren’t logos. They’re identity. E-ONE’s longevity is tied to continuous innovation, its dealer network, and the institutional trust built over years of deliveries and service. Across REV’s portfolio, those legacy names carry weight with chiefs and fleet managers who often develop strong preferences over their careers.

Cornered Resource: LOW

REV doesn’t appear to have a single protected resource—patents, unique materials, or exclusive IP—that permanently blocks competitors. The advantage is more practical than proprietary.

Process Power: MODERATE

Decades of custom engineering and build know-how matter in specialty vehicles. Process capability is a competitive asset. But REV’s 2017–2020 struggles are the reminder that process power is only real if it’s executed consistently. These moats can be widened—or undermined—by operations.

Synthesis

REV’s strongest competitive position sits in Specialty Vehicles, where brand loyalty, switching costs, and regulatory know-how create real barriers. The catch, historically, was portfolio mix: the most defensible businesses weren’t always the ones driving the most revenue, while the most cyclical businesses could dominate results in the wrong year.

That’s why the transformation matters. Exiting buses, rationalizing RV exposure, and doubling down on fire and emergency isn’t just simplification—it’s REV aligning the company around the parts of the portfolio that actually have durable competitive advantages.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

Any serious look at REV Group as an investment has to start with one complication: the pending Terex merger. If it closes, REV stops being an independent public-company story. But the bull and bear cases are still worth unpacking, because they explain why the deal makes strategic sense—and what risks don’t magically disappear just because there’s a bigger parent on the other side.

The Bull Case

Start with demand. In fire and emergency, the tailwinds are real and they’re not a one-quarter phenomenon. As of October 2024, REV had a $4.2 billion backlog of fire and emergency vehicle orders in the United States. That’s the clearest indicator of what departments are telling the market: they still need trucks, they need them soon, and the fleet is getting old. Many fire apparatus in service have ages that exceed recommended replacement cycles, which creates a multi-year replacement runway that tends to hold up even when the broader economy gets shaky.

Then there’s execution—REV’s biggest historical weakness, and the thing it’s spent the last few years trying to prove it can do. The turnaround showed up in the numbers. In the fourth quarter, REV reported net sales of $664.4 million, up 11.1% year over year. Adjusted EBITDA grew 40.5% to $69.7 million, and margins expanded to 10.5% from 8.3% in Q4 2024. Translation: the same factories are pushing out more profitable work, and the business is starting to look like a disciplined manufacturer rather than a collection of legacy plants.

Cash flow reinforced that story. REV generated record free cash flow of $190 million for the fiscal year, ended October 31, 2025 with net debt of just $5.3 million, and returned $120.5 million to shareholders through share repurchases and dividends during the year. For an industrial business that was once defined by working-capital stress and credibility problems, that combination—cash generation, a cleaner balance sheet, and shareholder returns—reads like management finally got control of the machine.

Electrification adds another layer to the upside narrative. If fire apparatus follows the broader vehicle world toward electrified drivetrains, early credibility matters. REV has been positioning itself as an early mover: in November 2021, E-ONE was contracted by the city of Mesa, Arizona to build what it described as the first fully-electric firetruck in North America. Even if volumes are small today, the strategic bet is that electrification could support premium pricing and, if executed well, better margins over time.

Finally, there’s the Terex angle. The merger pitch is that scale and portfolio fit can unlock cost synergies and create a more resilient industrial platform. The combined company is expected to have approximately $7.8 billion in net sales and an Adjusted EBITDA margin of about 11% as of year-end 2025, excluding any synergy benefit. At closing, it’s estimated the combined company would sit at roughly 2.5x net debt to trailing twelve-month pro forma Adjusted EBITDA. In the bull case, REV’s improved operations plug into Terex’s broader specialty equipment footprint, and the whole becomes more valuable than the parts.

The Bear Case

The biggest bear argument is that REV’s historical problem never fully goes away: cyclicality and complexity still find you. Even as the company has stabilized, its mix still includes a volatile consumer-exposed business. The RV segment remains about 30% of REV and is inherently boom-bust, which means earnings can swing regardless of how strong fire apparatus demand is.

Then there’s the political and regulatory overhang in fire apparatus. Consolidation and long delivery times have attracted scrutiny, and that scrutiny can shape procurement behavior, public perception, and potentially policy. Senator Hawley, speaking about Pierce and REV Group, put it bluntly: “Your business models are identical. Your customers hate them. They hate your business model. It’s killing them. It’s literally killing people, and yet you’re both doing it and making ungodly sums of money.”

Critics argue that in a concentrated market, major manufacturers have less incentive to expand capacity or innovate in ways that bring down prices or eliminate backlogs. With demand rising and supply constrained, prices have surged. Even if REV believes those price increases reflect real costs and complexity, the risk is that public and political pressure forces changes to how the market operates—or at least makes it harder to maintain the status quo.

And then there’s execution risk—the scar tissue from 2017 to 2020. REV has done real work to improve operations, but it’s still a complicated manufacturing business dependent on suppliers and long-lead-time production. Chassis shortages could return. Municipal budgets could tighten in a recession and push purchases out, even with aging fleets. And if the Terex merger closes, integration becomes the new test. Big combinations are where “we’ll get synergies” meets the reality of systems, factories, and cultures.

Key Metrics to Monitor

For investors tracking REV Group (or the combined company post-merger), two KPIs deserve primary attention:

-

Specialty Vehicles Segment EBITDA Margin: This is the clearest scoreboard for operational execution in the core business. The move from mid-single digits to low-double digits is the turnaround in one line. Continued improvement toward peer margins (10%+) supports the strategy; any backsliding is usually an early warning that execution is slipping.

-

Specialty Vehicles Backlog Conversion: Backlog only matters if it turns into delivered trucks and recognized revenue. Watching the relationship between backlog and sales helps separate “demand is strong” from “we’re just behind.” A rising backlog with flat revenue can signal delivery constraints; a declining backlog with stable revenue can signal improving throughput; a declining backlog paired with declining revenue is when you start worrying about demand.

XI. Lessons & Takeaways: The Playbook

REV’s path—from a private equity roll-up, to a hyped IPO, to a near-breakdown, and then back to something resembling an operating company again—offers a pretty clean set of lessons for anyone studying industrial consolidation.

Roll-up risks exceed most models. The consolidation thesis sounded great on paper: more purchasing power, shared best practices, and “professionalized” operations across a messy, fragmented industry. But specialty vehicles aren’t software SKUs. Every acquisition arrived with its own culture, homegrown processes, and deeply personal customer relationships. Integrate too aggressively and you break what customers loved. Let every brand do its own thing and you never get the synergies you promised. The real lesson is that integration is less about spreadsheets and more about people—culture, tribal knowledge, and trust.

Segment diversification can create portfolio risk. REV sold diversification as a stabilizer: fire and emergency would be the steady base, while RVs would add growth. What actually happened is that the RV cycle dominated the story. When dealers slammed the brakes, it didn’t just hurt the Recreation segment—it dragged the whole company’s results, investor confidence, and valuation down with it. The lesson: a highly cyclical business doesn’t “balance” a defensive one; it can swallow it.

Public market timing matters. REV came public in early 2017, when the RV market was strong and expectations were easy to set high. When the cycle turned, those expectations didn’t just miss—they broke credibility. And in public markets, once credibility cracks, everything gets harder. The lesson: IPO windows often open when things look best, which is exactly when it’s most dangerous to assume “best” is normal.

Operational excellence in thin-margin businesses is non-negotiable. When your margins live in the mid-single digits, you don’t get to have “a couple rough quarters” operationally. Delivery delays, quality issues, inventory mistakes, and working-capital sprawl don’t nibble at profits—they erase them. The lesson: in specialty manufacturing, execution isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the entire margin.

Brand value in B2B contexts is real. Fire chiefs’ loyalty to specific manufacturers can look sentimental from the outside, but it’s mostly rational. These are low-frequency, high-stakes purchases tied to training, maintenance routines, and dealer relationships built over years. Even when REV stumbled operationally, those brands retained meaningful pull. The lesson: B2B brands can be just as powerful as consumer brands when the job is mission-critical and switching is painful.

Private equity exits create transition challenges. AIP built REV through consolidation and then took it public. But running a roll-up inside a private equity wrapper is different from running the same business under public-market scrutiny, with quarterly expectations and less tolerance for operational noise. The lesson: the shift from private to public ownership isn’t just a capital markets event—it’s an operating model change, and not every organization is ready for it.

XII. What's Next? The Road Ahead

The pending merger with Terex is the biggest turning point in REV Group’s story since AIP first started stitching the platform together. If it closes, REV won’t be an independent public company anymore. Its brands—E-ONE, Ferrara, Spartan ER, and the rest—become part of a larger specialty equipment portfolio.

Terex laid out a clear leadership plan for day one. Upon closing, Terex CEO Simon Meester is expected to serve as President and Chief Executive Officer of the combined company, backed by a management team meant to blend strengths from both organizations. Meester called the deal “a transformative step for both companies.”

Governance follows the same “blended” approach. The combined company’s board is expected to have 12 directors: 7 from Terex and 5 from REV Group.

Strategically, the logic fits the direction REV has already been moving. Over the last few years, REV has been narrowing its identity toward specialty vehicles tied to municipal and industrial demand—categories that are slower to whipsaw than consumer recreation. Terex brings adjacent end markets of its own, including utilities, waste, and environmental equipment. Put together, the pitch is a broader specialty equipment platform positioned to benefit from infrastructure-driven spending.

Terex has also said it plans to exit its Aerials segment, including evaluating a sale or spin-off, as a way to further reduce exposure to cyclical end markets. In a way, that echoes what REV has been doing all along: prune the portfolio, sharpen the story, and leave less of the business at the mercy of the next consumer downturn.

One theme doesn’t change regardless of who owns whom: electrification. E-ONE has been pushing the Vector, its electric fire apparatus. “A fine example of the innovation E-ONE is known for is the Vector, the first North American style fully electric fire truck with the highest EV battery capacity,” says McClung. “The Vector can respond, pump, operate, and return all on electric.”

But the real question isn’t whether electric fire trucks are possible. It’s whether they’re good business. Electrified apparatus can command premium prices, but they also require heavy engineering investment, and margins could get squeezed if components commoditize faster than manufacturers can differentiate. Being early can be an advantage—if adoption takes off and competitors can’t catch up quickly.

The other “watch this closely” storyline is regulatory scrutiny. Testimony has called for an investigation into the conduct of REV Group and Pierce over the last decade and a half, including urging the FTC to launch a 6(b) investigation to bring transparency to what critics describe as an opaque industry.

Congressional attention to pricing and delivery times in fire apparatus could eventually translate into policy pressure or enforcement action. It’s hard to handicap outcomes here, but the direction is clear: the more essential the product, and the more concentrated the market, the more likely it is to attract scrutiny—especially when departments are waiting years for trucks they need now.

XIII. Epilogue & Final Reflections

REV Group’s story is a neat little paradox of American business: a company that helps power the fire trucks responding to your emergencies, the ambulances carrying your loved ones to hospitals, and the school buses transporting your children has spent most of its life in the market’s blind spot.

That invisibility is partly structural. This is a B2B and B2G business. Fire chiefs and fleet managers know E-ONE and Ferrara the way car enthusiasts know Porsche and Toyota. Most retail investors have never heard the names, because they’re rarely the ones writing the checks. And when you don’t have consumer mindshare, you don’t get automatic investor mindshare either.

The paradox gets sharper when you look at competitive position. REV built leadership in industries that are genuinely essential, with real barriers to entry and long-lived customer relationships. Yet as a public company, it struggled—hard. The same roll-up strategy that created scale also created complexity. And the diversification story that sounded so comforting at IPO—steady municipal demand plus consumer growth—ended up backfiring when the cyclical side swung the whole narrative.

What the last few years showed, especially as the company narrowed its focus and rebuilt discipline, is that even an industrial business that looks “too messy” can recover when management does the fundamentals well: simplify the portfolio, fix the plants, improve throughput, and stop promising what the factories can’t deliver. The distance from a sub-$5 share price and existential questions to a merger valuation north of $3 billion is a real arc of value creation—even if it doesn’t erase the fact that much of the early public-market optimism never came back.

Now the pending Terex merger closes one chapter and opens another. REV’s brands will keep building for first responders and customers, just under a new corporate umbrella. But the lessons travel with them: roll-ups are harder than the spreadsheet says, diversification can amplify risk instead of reducing it, and in thin-margin manufacturing, execution isn’t a strategy—it’s survival.

And for the fire trucks screaming down the street, the ambulances racing to emergencies, and the school buses making their morning routes, none of this corporate drama matters. They don’t run on ticker symbols, private equity exits, or EBITDA margins. They run because people design, build, and maintain them to standards that don’t allow for excuses. That mission—connecting and protecting communities, as REV’s mission statement puts it—outlasts market cycles.

REV Group may be ending its story as an independent company. But the institution—the accumulated craft in brands like E-ONE, Ferrara, and Wheeled Coach—keeps going. In the end, that’s the real point. The vehicles show up when everything else is going wrong. And they do their job, one call at a time.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music