Arcus Biosciences: The Story of Building a Cancer Immunotherapy Powerhouse

I. Introduction and Episode Roadmap

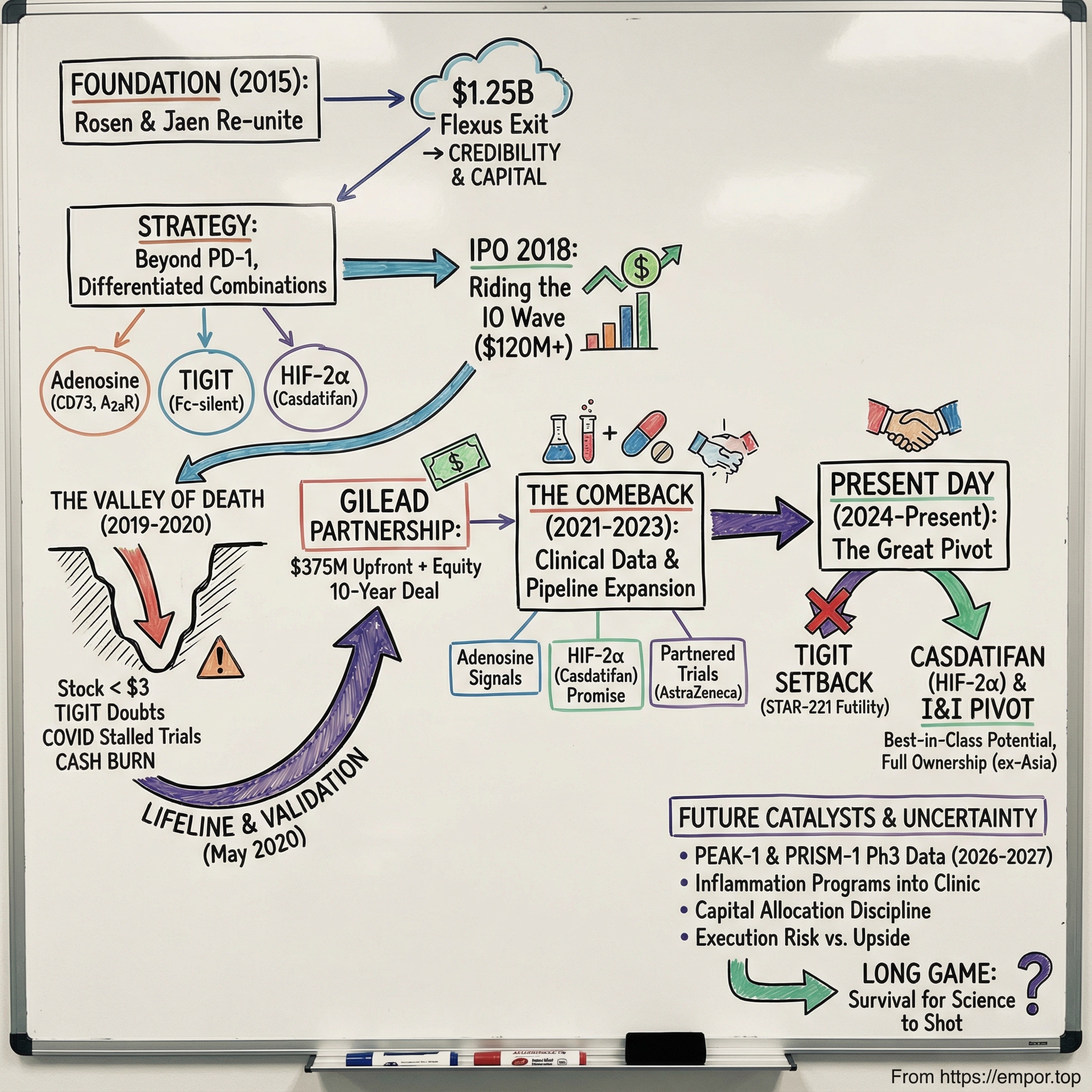

Picture this: it’s late 2024, and somewhere in a hospital ward, a patient with advanced kidney cancer is enrolled in a clinical trial and receiving an experimental drug called casdatifan. To that patient, it’s hope in an IV bag. To the people who built it, it’s the sum of nearly a decade of scientific conviction, brutal setbacks, and the kind of persistence biotech demands. The company behind it—Arcus Biosciences—is a case study in what it takes to survive long enough for the science to matter.

Arcus was incorporated in 2015 and is based in Hayward, California. It’s a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company with a market capitalization exceeding $2 billion and a pipeline of investigational cancer therapies spanning multiple mechanisms of action. But getting from “newco” to “possible breakthrough” didn’t happen in a straight line. Arcus rode the highs of an industry boom, slammed into the wall of clinical reality, nearly ran out of oxygen, and then found a lifeline that changed its trajectory.

So here’s the deceptively simple question at the center of this story: how did a startup founded during biotech’s immuno-oncology gold rush survive when so many others didn’t?

The answer runs through three things: a strategy built on differentiation instead of chasing the obvious, a partnership that arrived at exactly the right moment, and a leadership team that had already been through the war—and come out the other side.

In this deep dive, we’ll move from the founding vision that emerged out of a $1.25 billion exit, to the brutal 2019–2020 stretch when Arcus’s stock cratered below $3 and the future looked genuinely uncertain, to the transformative partnership with Gilead that reshaped the company’s prospects. And we’ll bring it up to the present: Arcus expanding development of casdatifan, a potential best-in-class HIF-2α inhibitor with robust single-agent activity, with multiple data readouts expected in 2026, while also concentrating early development on five programs targeting inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Along the way, the themes will feel familiar to anyone who follows biotech: taking scientific risks in the shadow of giants, using partnerships as a survival tool, and accepting the core truth of drug development—the long game is the only game, and most companies don’t live long enough to play it to the end.

II. The Immunotherapy Revolution and Founding Context (2010–2015)

To understand why Arcus exists, you have to rewind to the early 2010s—when cancer treatment quietly flipped from a war of attrition to something closer to systems engineering.

For most of modern oncology, the playbook was blunt: cut tumors out, burn them with radiation, poison fast-dividing cells with chemotherapy. Sometimes it worked. Often it didn’t. And for advanced cancers, “treatment” could mean buying time at a brutal cost.

A small group of scientists kept asking a different question: what if the immune system already knew how to kill cancer, but cancer had figured out how to shut it down?

In the 1990s at UC Berkeley, James P. Allison focused on a protein on T cells called CTLA-4. CTLA-4 acts like a brake—one of the body’s safeguards against an overactive immune system. Most researchers saw that brake and thought about autoimmune disease. Allison saw an opportunity in the opposite direction: if you could temporarily release the brake, T cells might attack tumors.

He developed an antibody that could bind CTLA-4 and block it. In late 1994, his team ran a pivotal experiment in mice. They were so stunned by the results that they repeated it over the Christmas break. The headline was simple and almost unbelievable for the era: mice with cancer were cured by disabling the immune “brake” and unleashing T-cell activity.

Industry interest was limited at first. Allison kept pushing anyway, and by 2010 an important clinical study showed striking effects in patients with advanced melanoma. In a disease where the usual story was rapid decline, some patients saw their remaining cancer disappear.

Around the same time, another brake came into focus. In Japan, Tasuku Honjo discovered PD-1, a separate molecular checkpoint that also dampens T-cell activity, but through a different mechanism. Clinical development followed quickly, and in 2012 a key study showed clear efficacy across multiple cancers. For some patients with metastatic disease—previously considered essentially untreatable—the results looked like long-term remission, even cures.

In 2018, Allison and Honjo would share the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for these discoveries. But long before Stockholm, the market had already rendered its verdict.

Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Opdivo (nivolumab) and Merck’s Keytruda (pembrolizumab) became the blockbuster validators of checkpoint inhibition. Keytruda won its first US FDA approval in September 2014 and reached the market days later. Opdivo followed roughly three months after. Those approvals didn’t just add two new drugs—they created a new center of gravity in oncology, and the industry started reorganizing around it.

By 2024, Keytruda had become a cornerstone therapy with more than 40 indications, including multiple lung and gynecological cancers, and about $25 billion in annual sales—surpassing Humira to become the best-selling drug in any therapeutic area. The broader PD-1/PD-L1 market ballooned into one of the largest franchises in pharmaceutical history, with estimates putting it at roughly $49 billion in 2024 and projecting continued growth.

This is the backdrop Arcus was born into: validated science, massive commercial opportunity, and a feeding frenzy. Every pharma company and biotech wanted to be in immuno-oncology. The easy move was obvious: build your own PD-1 and try to ride the wave.

Arcus’s founders chose a harder path.

In 2015, Terry Rosen and Juan Jaen co-founded Arcus with a blank sheet of paper and a very specific ambition: develop highly combinable, best-in-class cancer therapies with the potential to be curative. They weren’t naïve founders chasing the trend. They’d already built and sold an immuno-oncology company at exactly the right moment.

Rosen and Jaen had co-founded Flexus Biosciences, which Bristol-Myers Squibb acquired in 2015 for $1.25 billion—just 14 months after Flexus started. BMS was buying the rights to Flexus’s lead preclinical small-molecule IDO1 inhibitor (F001287) and an IDO/TDO discovery program. A billion-dollar outcome in barely over a year doesn’t just provide capital; it gives you credibility, momentum, and a network of people who now take your next idea seriously.

“The economic outcome was not our intent,” Rosen explained. “It enabled us to start Arcus, more than just financially.” In other words: Flexus didn’t just fund Arcus. It proved the founders could spot targets, build programs fast, and create something big pharma would pay for.

The partnership between Rosen and Jaen also ran deeper than a single deal. They’d known each other for decades, connected originally through academia. Rosen, a Chicago native with an early pull toward chemistry, went to the University of Michigan and later pursued his Ph.D. at UC Berkeley. Jaen, originally from Madrid, moved to the US as a teenager, finished high school near Detroit, and—after undergraduate studies in Madrid—also came to the University of Michigan for his Ph.D. It was there that he and Rosen first worked together in the lab.

Rosen’s assessment of Jaen stuck: “Juan was the smartest guy in the department.”

By the time Arcus was formed, Jaen had deep drug-discovery and management experience. At ChemoCentryx, he led the discovery and advancement into the clinic of eight novel drug candidates in immunology. From 1996 to 2006, he held scientific management roles at Tularik and then Amgen, ultimately becoming Vice President of Chemistry.

So Arcus entered the immuno-oncology gold rush with two founders who weren’t guessing. They were reloading.

Their thesis was also clear-eyed about timing. They knew they were late to the PD-1 race—and they didn’t pretend otherwise. Instead, they aimed at what came next: build combination therapies by targeting the ways tumors suppress immune responses. Rather than go head-to-head with Keytruda and Opdivo, Arcus would develop drugs designed to work alongside checkpoint inhibitors, creating combinations that might push responses deeper, longer, and into patient populations that weren’t benefiting yet.

That was the bet: not another checkpoint clone, but a toolkit built for mixing and matching—designed for a world where immunotherapy had already won, and the next frontier was making it work for more people.

III. The Scientific Strategy: Beyond Checkpoints

Terry Rosen and Juan Jaen made a decision early that would shape Arcus for years: they weren’t going to build yet another PD-1 inhibitor and pretend they could outrun Merck and Bristol Myers. That race already had its winners. Arcus would instead try to win the next one—by building a set of drugs that could be combined in different ways to punch holes in the various tricks tumors use to silence the immune system.

Their first big focus was the ATP-adenosine pathway, and they picked three small-molecule targets along it: CD73, CD39, and the A2A receptor. The biology is simple to say and devilish to beat. When cells are damaged or dying, they release ATP, which acts like a flare—an alarm signal that tells the immune system something is wrong. “Normally, ATP is released by cells as they die or are damaged,” Rosen explained. “It’s a signal to the rest of the immune system to mount an inflammatory response.”

Tumors, however, try to turn that alarm into a lullaby. Using enzymes like CD73 and CD39, they help convert extracellular ATP into adenosine—a molecule that dampens immune activity. So the insight wasn’t just that tumors evade detection; it’s that they can actively build an immunosuppressive “shield” around themselves. If you can block the conversion to adenosine, or block adenosine’s downstream signaling, you might keep immune cells awake and fighting.

That idea produced one of Arcus’s earliest flagship programs: etrumadenant (AB928), a dual A2a/A2b adenosine receptor antagonist. AB928—the first and only dual A2a/A2b adenosine receptor antagonist in the clinic—went into several Phase 1b/2 studies across a wide range of tumors, including prostate, colorectal, non-small cell lung, pancreatic, triple negative breast, and renal cell cancers.

But adenosine wasn’t their only swing. Arcus also moved into TIGIT, a checkpoint target that, at the time, was being talked about as “the next PD-1.” TIGIT (T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains) is another brake on T cells, and the hope was that blocking TIGIT could pair naturally with PD-1 inhibition—two brakes released at once.

That became domvanalimab (AB154), Arcus’s anti-TIGIT antibody—and they engineered a key differentiator into it. Domvanalimab was designed to be “Fc-silent,” meaning it was engineered not to bind Fc receptors. The theory was that this could improve safety while preserving efficacy, and it set Arcus apart from competitors such as Roche’s tiragolumab.

And then there was the part of the strategy that seems almost contradictory at first. Arcus didn’t want to chase PD-1—but it still needed PD-1.

So the company licensed zimberelimab (AB122), a PD-1 antibody, from China’s Gloria Pharma and WuXi Biologics. Shortly before its Series C raise, Arcus bolstered its pipeline with an exclusive licensing deal potentially worth up to $816 million, paying $18.5 million upfront for European, North American, and Japanese rights.

The logic was straightforward: combinations need a backbone. If Arcus wanted to run its own combination trials—on its timeline, in its chosen indications, with its preferred partners (or none at all)—it couldn’t depend on borrowing someone else’s PD-1 indefinitely. Owning the PD-1 piece meant control.

“Everyone knows that combinations are important, but it’s become apparent that in immuno-oncology it may be advantageous to own or control parts of the combination,” Rosen told FierceBiotech.

That was the portfolio approach in a nutshell: multiple mechanisms, both small molecules and antibodies, designed to be mixed and matched into internal combinations. Rosen even compared the immuno-oncology combo land-grab to the hepatitis C race—an era defined by assembling the right multi-drug regimens, with clear winners and painful losers along the way.

The catch was that these were big bets on unproven ground. TIGIT hadn’t been validated in humans. The adenosine pathway made biological sense, but there were no approved drugs proving it could translate into real patient benefit. Arcus was putting serious money and years of effort behind mechanisms that might turn out to be transformative—or might do nothing at all.

Rosen was also clear-eyed about the broader frenzy in immuno-oncology. He expected a wave of disappointing data, driven by poorly planned combination trials. But he wasn’t backing away from the fundamental premise. “Immuno-oncology is a very unique, rare situation,” Rosen said. “The body should be able to kill tumors, but the reality is that most things tried in the past haven’t worked so well.” He continued: “Recent trials with immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as PD-1 antibodies, have shown that if you can get the immune system to do what it’s supposed to do, you can treat cancer.” For Arcus, the conclusion was obvious: “This is something to double down on—we’re going to bet big.”

For investors, that strategy cut both ways. Multiple shots on goal meant you weren’t living or dying on a single molecule. But it also meant heavy burn, real execution complexity, and a company attempting one of biotech’s hardest feats: running several clinical programs in parallel and assembling combinations before the rest of the world caught up.

IV. IPO and Early Days: Riding the Wave (2018)

By early 2018, Arcus had done what a lot of biotechs dream about: it had raised real private capital, assembled a credible pipeline, and convinced investors it wasn’t just another “me too” immuno-oncology story. Just months after raising $107 million in its Series C, the company turned to the public markets to fund the next leg—pushing its lead programs, including AB928 (etrumadenant), deeper into the clinic.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Arcus went public in March 2018, pricing 8 million shares at $15 each. The shares began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol “RCUS” on March 15, and the deal brought in roughly $120 million in gross proceeds at pricing. With the underwriters exercising their overallotment option for an additional 1.2 million shares, the IPO ultimately totaled about $138 million in gross proceeds.

Arcus wasn’t walking into the IPO window alone, either. It had already raised $227 million in equity financing from a roster that signaled serious conviction—GV (Google Ventures), Celgene, Stanford University, and others. Rosen described the early fundraising arc simply: they started with $30 million from founders plus friends and family, expanded it to $50 million by bringing in strategic investors like The Column Group and Celgene, then raised $70 million in a Series B that was, in his words, “very oversubscribed,” led by GV alongside Invus, Taiho Ventures, DROIA Oncology Ventures, and Stanford.

The public-market pitch was clean and compelling: multiple shots on goal in immuno-oncology, a founding team that had already built Flexus into a billion-dollar outcome, and a portfolio built for combinations—targets beyond PD-1, but with a PD-1 backbone they controlled.

And 2018 was the kind of market that rewarded that story. The biotech IPO window was wide open, and immuno-oncology was still the industry’s favorite genre. Arcus came out with momentum, and investors bought into the idea that the company could translate its platform into clinical proof.

Behind the scenes, Arcus was building like a company that intended to last. Rosen was explicit about rejecting the “virtual biotech” model. “There’s nothing virtual about us,” he said. “We have good lab space. We have a very strong chemistry group and we don’t view it as a commodity or something that can be outsourced. I’ve never really believed that.”

That wasn’t just a cultural preference—it was a strategic choice. If Arcus was going to run multiple programs, iterate quickly, and engineer combinations in a fast-moving field, it needed real internal horsepower, not just a project-management layer on top of vendors.

For a while, the story tracked the way you want it to. Programs moved into human trials. Combinations were mapped out. The team expanded to match the growing operational complexity. For a brief moment, it looked like Arcus might glide from concept to clinic on a smooth updraft of capital and confidence.

But biotech doesn’t let you live in that moment for long. Plans are just hopeful hypotheses until the data arrives—and the data was about to get complicated.

V. The Reckoning: Clinical Setbacks and The Valley of Death (2019–2020)

The stretch from 2019 through 2020 was the part of Arcus’s story where the plot stops being “promising platform biotech” and starts being “will this company make it.” What began as ordinary competitive pressure turned into something closer to an existential threat—one that hit the science, the stock, and the company’s ability to fund itself, all at once.

The first cracks showed up in 2019. Roche’s tiragolumab started to dominate the conversation as the anti-TIGIT frontrunner. Arcus was in the same lane with domvanalimab, but Roche had the money, the infrastructure, and the machine-like ability to run big trials fast. Meanwhile, Arcus’s early readouts were the kind of data that kept a program moving—but didn’t create the surge of belief that lifts a stock and buys you patience from the market.

Then 2020 arrived, and COVID-19 kicked the legs out from under clinical development across the industry. Hospitals reprioritized. Trial sites slowed down. Patient enrollment became harder. Timelines that had been plotted with precision stretched into the unknown.

And just as Arcus was trying to push through that fog, the TIGIT story took a turn that rattled the entire field.

Roche reported another high-profile disappointment for tiragolumab, including a major lung cancer study that failed to slow tumor progression. Coming from a company that had made TIGIT one of the pillars of its oncology pipeline, it wasn’t just bad news—it was a referendum. Roche had already embarked on a large Phase 3 program, but repeated setbacks made it harder and harder to argue that blocking TIGIT was consistently adding meaningful benefit on top of existing immunotherapies like Tecentriq.

The market didn’t treat this as “Roche has a problem.” It treated it as “maybe TIGIT is the problem.”

Investors didn’t wait around for nuance. Confidence cracked across the whole class, and Arcus got dragged into the undertow. The narrative flipped almost overnight from “smart combination play” to something much darker: is the mechanism real at all?

Arcus’s stock reflected the panic. During the 2019–2020 stretch, it sank below $3 at its worst—down more than 80% from post-IPO highs. For a clinical-stage biotech, that kind of collapse isn’t just painful. It can be fatal.

Because when you’re a company funding multiple clinical trials, you are, by definition, burning cash continuously. You survive by keeping access to capital open. But if your stock is sitting at $3 while you’re burning roughly $150 million a year, raising money becomes brutally dilutive, and “just do a financing” stops being a viable plan. This is how biotechs enter a death spiral: the stock falls, financing becomes punitive, programs get cut, confidence drops further, and the spiral tightens.

Inside Arcus, this was the long, dark tunnel. Terry Rosen and his team had to make hard calls: what to prioritize, what to slow down, how to conserve resources without gutting the very work the company was built to do—and how to keep people focused when the outside world seemed to have decided the thesis was over.

Arcus held on to conviction, but not blindly. The company leaned into what it believed differentiated domvanalimab, including its Fc-silent design, as it watched Fc-enabled competitors struggle. And it kept pushing the adenosine pathway work forward. Even with enrollment slowed, progress didn’t stop.

But conviction wasn’t enough. Arcus needed oxygen. It needed capital.

And in 2020, a lifeline arrived.

VI. The Gilead Partnership: A Lifeline and Validation (2020)

In May 2020, with Arcus still getting pummeled by TIGIT doubts, a collapsing stock, and the general COVID-era shutdown of clinical research, Gilead Sciences made the kind of move that can change a company’s fate overnight. The two companies announced a 10-year partnership to co-develop and co-commercialize current and future candidates from Arcus’s pipeline—and to provide ongoing funding for Arcus’s R&D engine.

The headline was simple: cash, credibility, and time.

Gilead agreed to pay Arcus $175 million upfront and make a $200 million equity investment, with the broader collaboration carrying the potential for far more in funding, opt-in payments, and milestones tied to Arcus’s programs. Gilead’s equity came in at $33.54 per share, and it negotiated the right to increase its ownership over time—up to 35% of Arcus’s voting stock within five years—at a premium.

For Arcus, the structure mattered as much as the dollars. This wasn’t a distressed sale of the crown jewels. Arcus kept meaningful control and gained a partner with global reach. The companies would share global development costs. If the optioned programs were approved, they would co-commercialize in the U.S. and split profits there. Outside the U.S., Gilead would hold exclusive commercialization rights (subject to any pre-existing partner rights), paying Arcus royalties on net sales.

It was a classic “strategic marriage” at exactly the moment Arcus needed one: immediate capital to keep trials moving, plus validation that Gilead’s scientists had looked under the hood and liked what they saw.

Gilead’s motivation was straightforward, too. The company had built an empire in antivirals—HIV and hepatitis C—yet oncology hadn’t become the second act it wanted. Even after buying Kite Pharma in 2017 for $11.9 billion to get into CAR-T, Gilead still needed breadth: more assets, more shots, more ways to play in immuno-oncology. Arcus offered a ready-made portfolio of programs across different mechanisms and stages.

By the end of May 2020—after this investment and Gilead’s participation in Arcus’s follow-on offering—Gilead owned nearly 8.2 million Arcus shares, about 13% of the company.

And this was only the beginning. In February 2021, the stock purchase agreement was amended and restated as Gilead increased its stake from 13% to 19.7% through an additional $220 million investment.

In November 2021, Gilead went further, exercising options to multiple Arcus programs: domvanalimab and AB308 (both anti-TIGIT molecules), plus etrumadenant and quemliclustat. After the Hart-Scott-Rodino waiting period expired, the option exercises triggered $725 million in payments from Gilead to Arcus, expected in early Q1 2022.

The relationship capital behind the deal also mattered. Arcus wasn’t just selling molecules; it was selling a way of working—smart, fast, and disciplined in a messy part of biology. Terry Rosen’s long industry history and network helped, but more importantly, it was a bet on the team’s ability to execute.

The partnership expanded again in 2024. The companies amended their collaboration agreement, with Gilead making an additional $320 million equity investment in Arcus at $21 per share and raising its ownership stake to 33%.

For investors, the Gilead partnership was both opportunity and trade-off. Opportunity: funding, validation, shared development costs, and a global commercial machine if the drugs worked. Trade-off: Arcus gave up a big chunk of ex-U.S. economics and accepted a partner who would inevitably have a say in what got prioritized.

But in 2020, this wasn’t really a philosophical debate. The alternative wasn’t “stay independent.” The alternative was running out of runway before the data could speak. In that context, the deal did what it needed to do: it made survival—and a comeback—possible.

The market didn’t instantly throw a party. Even after the partnership, the stock remained weighed down by skepticism about the underlying science. But Arcus now had something it hadn’t had in months: breathing room. The trials could continue. The platform could keep firing. And the company finally had time to prove that its big bets weren’t just elegant theories.

VII. The Comeback: Clinical Data Revival (2021–2023)

With Gilead in its corner, Arcus moved from “can we survive?” to “can we execute?” The next few years were about doing the unglamorous, high-stakes work of clinical development: running trials, learning fast, and narrowing focus to the indications where its science had the best chance to show up in real patients.

There were, finally, green shoots. Combinations built around etrumadenant and zimberelimab started to produce encouraging Phase 1/2 signals, especially in colorectal cancer—one of the places where Arcus’s adenosine-pathway thesis seemed most plausible. The company didn’t just collect data; it used the data to learn who was actually responding, and to tighten the strategy around patient populations where the biology looked most supportive.

Domvanalimab, the anti-TIGIT bet, was messier. Results varied by indication and combination. In some settings, there were hints of differentiation; in others, the benefit was harder to separate from the noise and from what standard therapies already delivered. Arcus’s Fc-silent design—its chosen point of differentiation from Fc-enabled competitors—continued to spark debate: was it a meaningful advantage, or just a nice theory looking for clinical proof?

Arcus also strengthened the pipeline through additions that broadened its shots on goal. Over time, Gilead’s time-limited exclusive option rights to casdatifan expired. Meanwhile, new results from ARC-20 in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) showed casdatifan monotherapy improved the rate of primary progression, overall response rate (ORR), and progression-free survival (PFS). Those outcomes reinforced Arcus’s argument that casdatifan was differentiating relative to published data from HIF-2α inhibitor studies to date.

Casdatifan (AB521) started to look like more than just “another program.” It targeted a validated kidney-cancer mechanism: HIF-2α, a transcription factor that becomes dysregulated in ccRCC and helps drive tumor growth. Arcus put its enthusiasm on the record: "We are thrilled to be presenting the first clinical efficacy data from the ARC-20 study for our HIF-2a inhibitor, casdatifan, in an oral plenary session. These data support a potential best-in-class profile, and we are rapidly advancing a differentiated development program for casdatifan."

As the clinical story improved, the stock followed. From the lows under $3, shares recovered into the mid-teens and at times toward the $15–$20 range as progress accumulated and the Gilead partnership kept expanding. The narrative shifted from “this might not make it” to “this might actually work”—with the usual biotech asterisk: the hardest data was still to come.

By this point, Arcus and Gilead were co-developing four investigational medicines: domvanalimab (anti-TIGIT), zimberelimab (anti-PD-1), quemliclustat (CD73 inhibitor), and etrumadenant (adenosine receptor antagonist). The collaboration itself also widened, expanded in November 2021 and May 2023 to include research directed to two oncology targets and two inflammatory disease targets.

Arcus also began extending its reach through AstraZeneca, with two separate clinical collaborations. One was eVOLVE-RCC02, a Phase 1b/3 study evaluating casdatifan with volrustomig, AstraZeneca’s investigational PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecific antibody, as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic ccRCC. The other was PACIFIC-8, a registrational Phase 3 trial evaluating domvanalimab plus durvalumab (Imfinzi) in unresectable Stage 3 non-small cell lung cancer. AstraZeneca sponsored and operationalized both studies.

Taken together, 2021 through 2023 showed Arcus could run complex development programs while juggling partnerships with multiple pharma giants. But none of it was the finish line. The real verdict would come from pivotal readouts—the kind that don’t just move a stock, but decide whether a drug ever reaches patients.

VIII. Recent Developments and Current State (2024–Present)

The newest chapter in the Arcus story has been a whiplash mix of gut punch and regrouping.

On December 12, 2025, Arcus delivered the news it had spent years trying to avoid: its flagship TIGIT program hit the wall. The Phase 3 STAR-221 trial, which tested a domvanalimab-based regimen in upper gastrointestinal cancers, was stopped early after an interim look found the combination was unlikely to deliver a survival benefit. In biotech terms, that’s the coldest word there is: futility.

STAR-221 had been a defining bet. The study compared domvanalimab plus Arcus’s PD-1 antibody zimberelimab and chemotherapy against Bristol Myers Squibb’s Opdivo plus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced gastric and esophageal cancers. But the independent data monitoring committee overseeing the trial concluded the experimental combination did not improve overall survival versus the Opdivo-chemo regimen, and recommended the study be discontinued.

For Arcus, it wasn’t just one trial failing. It was a major blow to a thesis the company had championed for years, in a modality that had already seen many of the biggest names in pharma back away after their own disappointments. Domvanalimab was one of the last TIGIT programs still standing. STAR-221 made it much harder to argue that TIGIT, at least in this setting, was going to be the breakthrough the field once imagined.

Terry Rosen didn’t sugarcoat it. “The results from STAR-221 are not what we had hoped for, and we have important work ahead to meet the needs of patients on our domvanalimab studies and also accelerate the casdatifan and I&I programs,” he said. He also emphasized a key point for any clinical-stage company staring down a reset: Arcus still had resources and time. “We are fortunate to be well capitalized and plan to focus our resources on casdatifan, including studying new early-line combinations in kidney cancer, broadening its development into new tumor types, and extending our capabilities beyond oncology.”

That pivot had been building for a while, but STAR-221 made it decisive. Casdatifan became the center of gravity.

Rosen framed it as a turning point for the company: “We are thrilled to retain ownership of casdatifan, which has the potential to address a significant unmet need for patients with an estimated $5 billion market opportunity. Owning the rights to casdatifan represents a transformational change for Arcus, providing us with significant future strategic optionality.” He pointed to data presented at ASCO GU as evidence that casdatifan could be best-in-class among HIF-2α inhibitors, “in what appears to be a two-horse race,” and laid out the ambition plainly: “We anticipate that every patient with ccRCC will receive a HIF-2α inhibitor, and our development plan is designed to position casdatifan as the HIF-2α inhibitor of choice.”

The ownership piece matters here. When Gilead’s option on casdatifan expired in February 2025, Arcus kept the asset. That left Arcus in full control of what it believes is a best-in-class program targeting a validated mechanism in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. In ARC-20, a Phase 1/1b study in late-line ccRCC, Arcus reported robust single-agent activity from more than 120 patients, with improvements across the efficacy measures it highlighted, including overall response rate and progression-free survival, relative to reported data for the only marketed HIF-2α inhibitor. Arcus owns rights to casdatifan everywhere except Japan and certain other Asian territories, which were optioned to Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. in October 2025.

Financially, Arcus entered this reset with a cushion. The company reported $841 million in cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities as of September 30, 2025, and added roughly $270 million in net proceeds from a financing completed in November 2025. With that, Arcus projected runway through at least the second half of 2028—enough time to reach multiple major readouts, including casdatifan data expected in 2026.

In parallel, Arcus has continued to push other late-stage shots. In the fourth quarter of 2024, it initiated PRISM-1, a Phase 3 trial testing quemliclustat plus gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel versus gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel alone in pancreatic cancer. In February 2025, its partner Taiho dosed the first patient in Japan in PRISM-1.

As of this period, the pipeline was increasingly anchored by two Phase 3 efforts. One is PEAK-1 in kidney cancer, evaluating casdatifan in combination with cabozantinib versus cabozantinib in immuno-oncology-experienced patients with ccRCC, with initiation expected in the first half of 2025. The other is PRISM-1 in pancreatic cancer, with results expected in 2027.

And Arcus is also trying to turn the page into a second act beyond oncology. Early development is now aimed at five programs in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, with a small molecule targeting MRGPRX2 expected to enter the clinic in 2026 for atopic dermatitis and chronic spontaneous urticaria.

For investors, this is the new Arcus question. The TIGIT bet—once a pillar—has largely broken, and not just for Arcus. What remains is whether casdatifan, with early data that Arcus believes supports best-in-class potential in a validated kidney cancer mechanism, can carry the company into its next phase. The company has time and capital. Now it needs the kind of data that turns a pivot into a foundation.

IX. The Business Model and Strategy Playbook

Arcus’s business model sits right in the oldest argument in biotech: do you build a “platform” with multiple programs and multiple ways to win, or do you go all-in on a single best idea and run it as hard as you can?

Arcus chose the platform route on purpose. From the beginning, it built several mechanisms under one roof—so it could test combinations internally, move faster than if it had to negotiate for every component, and avoid becoming a company whose fate hinged on a single clinical readout.

The upside is easy to see in hindsight. If one bet breaks, another might carry the company. When TIGIT cracked, Arcus still had other shots—adenosine work that had generated signals, and later a very real-looking asset in casdatifan. The platform also made Arcus more valuable to a partner like Gilead, which wasn’t looking for a single molecule—it wanted access to a broader engine.

But the downside is just as real. Platforms are expensive. They multiply complexity. And they force trade-offs: advancing several programs at once can dilute focus at the exact moment you need ruthless prioritization. When TIGIT started wobbling, Arcus wasn’t only managing one rescue mission—it was managing a whole portfolio under pressure.

That’s why Arcus’s partnership strategy matters so much. The Gilead deal wasn’t just “take the money.” It was structured to keep Arcus alive without giving up the keys. Arcus secured major funding while retaining meaningful control over how programs moved forward. The co-development model shared the cost and risk as trials got bigger and more expensive. And if anything ever reached the market, Gilead’s global commercial footprint meant Arcus wouldn’t have to build a worldwide launch machine from scratch.

Of course, nothing is free. The trade-off was ex-U.S. economics. For the programs Gilead optioned, Arcus gets tiered royalties outside the United States instead of keeping profit share. It’s the classic biotech exchange: trade a chunk of long-term upside for the ability to stay in the game long enough to reach the moment of truth. In 2020, when the alternative looked a lot like running out of runway, it was a rational bargain.

You can see the shape of the model in the financials. In 2024, Arcus reported $258.00 million in revenue, up from $117.00 million the year before—driven primarily by the Gilead collaboration through milestone payments, cost sharing, and other partnership economics, not product sales, because Arcus still didn’t have approved medicines on the market. Losses were -$283.00 million, slightly improved from 2023. That’s the normal profile for a clinical-stage biotech: spending heavily now in exchange for the possibility of much larger returns later—if the science holds up.

Which brings us to capital allocation discipline. After STAR-221 was halted for futility, Arcus had to do what good biotech operators do, even when it hurts: stop spending on what isn’t working and redirect resources toward what still has a path forward. In Arcus’s case, that meant leaning harder into casdatifan and accelerating its emerging inflammation and autoimmune portfolio. In this business, knowing when to cut is as important as knowing when to double down.

Then there’s the part investors often underestimate until it becomes a problem: manufacturing and supply chain. Antibody drugs like domvanalimab and zimberelimab demand specialized biologics manufacturing. Small molecules like casdatifan come with a different set of technical and quality requirements. Arcus has relied on contract manufacturing organizations, but “outsourced” doesn’t mean “hands off”—the company still has to maintain tight oversight and quality control, because execution failures here can derail timelines just as surely as bad data.

Finally, there’s patient selection—where modern oncology increasingly lives or dies. Not all tumors respond the same way, and a drug that looks mediocre in an all-comers population can look meaningful in the right slice of patients. That’s why biomarker strategy has become inseparable from clinical strategy. Arcus has incorporated biomarker-based approaches into its trials, trying to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from each mechanism—because in precision medicine, finding the right patient can be the difference between a failed study and a viable product.

X. Porter's 5 Forces and Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To see where Arcus can actually win—and where it’s fighting uphill—you have to zoom out from trial readouts and into the structure of the industry. Cancer drugs don’t succeed in a vacuum. They succeed in a market shaped by incumbents with enormous budgets, regulators who demand clear proof, and payers who increasingly ask, “Is this meaningfully better?”

Porter’s 5 Forces:

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH. Immuno-oncology is one of the most crowded, best-funded arenas in medicine. Merck’s PD-1 inhibitor Keytruda sits at the center of it, a cornerstone therapy with more than 40 indications. Bristol-Myers Squibb has Opdivo. Roche has Tecentriq. AstraZeneca has Imfinzi. And behind them, dozens of biotechs are trying to wedge into the standard of care with new targets and clever combinations. The problem is that “slightly better” often isn’t enough. When doctors already have good options, and payers are watching costs closely, marginal improvements can be met with real skepticism.

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH. The barriers are brutal—drug development can take more than a decade and hundreds of millions of dollars. But the pipeline of new entrants never stops. Venture funding, academic discoveries, and new tooling keep producing fresh companies with fresh mechanisms. And as platform technologies, including AI-driven drug discovery, mature, the speed of early-stage competition could increase.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE. In theory, manufacturers and raw-material suppliers are replaceable. In practice, biologics manufacturing can become a bottleneck, and not every contract manufacturer has the capacity or expertise you need. For small-molecule inputs, many materials are closer to commodity. The most constrained “supplier” is people: experienced scientists, clinicians, and operators who know how to run complex oncology development are scarce, and competition for them is constant.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH. In oncology, the buyers aren’t just patients and physicians. They’re also insurance companies, pharmacy benefit managers, and government payers—and all of them demand clear evidence of value. Oncologists often have multiple treatment options, especially in major tumor types where checkpoint inhibitors are already established. The direction of travel is also clear: more pressure toward value-based pricing and hard outcomes, not just theoretical promise.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH. Immunotherapy competes with everything: surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, targeted therapies, cell therapies like CAR-T, and emerging approaches like cancer vaccines. Innovation doesn’t slow down, which means today’s breakthrough can become tomorrow’s baseline. The one counterweight is the reality of cancer itself: unmet need remains enormous, and there’s room for multiple winners if a therapy delivers truly differentiated benefit.

Hamilton’s 7 Powers:

Scale Economies: POTENTIAL (not yet realized). Arcus is still a clinical-stage company with no approved products, so it doesn’t yet have the scale advantages that come from commercial manufacturing and a leveraged sales force. If it reaches approval, oncology economics can be powerful—high gross margins—but getting there requires major infrastructure and execution.

Network Effects: NOT APPLICABLE. Drugs don’t benefit from classic network effects the way software does. The closest analogue is data: real-world evidence can compound over time, but that advantage is still emerging and isn’t a primary driver today.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE. Arcus has tried to avoid being a “me too” checkpoint company. Its focus on mechanisms like the adenosine pathway and HIF-2α gives it a different angle than pure PD-1/PD-L1 competition, and its combination mindset creates alternative ways to compete. The risk is obvious: if Arcus proves a mechanism works, much larger companies can pursue the same biology through acquisitions or internal development.

Switching Costs: LOW-MODERATE. There’s some inertia in prescribing habits and treatment protocols, and patients who are responding tend not to switch. But oncology also normalizes switching when a therapy fails—moving to the next line is built into the clinical reality. Biomarker-driven patient selection can raise switching costs somewhat, by creating a clearer “right drug for this patient” narrative.

Branding: LOW (currently). With no commercial product yet, Arcus doesn’t have a consumer or physician “brand” in the way major oncology franchises do. And in cancer care, branding is secondary to evidence—doctors follow the data. Still, the Gilead partnership offers a measure of borrowed credibility, and sustained clinical success is how a biotech earns real reputation.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE-HIGH. Patents are the obvious resource: exclusivity around molecules like casdatifan and the rest of the portfolio is the legal foundation for future economics. There’s also human capital. Dr. Jaen is an inventor on 50 patents and has helped advance more than 20 novel molecules into clinical development. And then there’s the partnership itself: Gilead’s capital, capabilities, and commitment function as a practical advantage that many similarly sized biotechs simply don’t have.

Process Power: MODERATE (building). Arcus has been forced to get good at hard things: running complex combination trials, navigating immuno-oncology regulatory pathways, and managing multi-partner development. Those capabilities compound. They’re not yet a clear differentiator versus the best large pharma teams, but they are real operational muscle.

Synthesis: Arcus’s strongest potential sources of enduring advantage sit in Cornered Resource (patents, leadership talent, and the Gilead relationship) and Counter-Positioning (especially around HIF-2α in kidney cancer). But the path from “interesting clinical-stage company” to “durable business” still runs through the same gate every biotech faces: proving efficacy clearly enough to earn approval, adoption, and ultimately the scale and reputation that can turn scientific promise into staying power.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case:

The bull case for Arcus starts with a simple idea: casdatifan could be the company’s reset button and its breakthrough at the same time. It targets HIF-2α, a mechanism that’s already been validated in kidney cancer, and Arcus believes the early clinical profile supports best-in-class potential. If the Phase 3 program confirms what the earlier studies suggested, Arcus wouldn’t just have “a product.” It would have a meaningful drug in a large market with real unmet need, and in a competitive set that, today, looks far less crowded than the PD-1 free-for-all.

Ownership is the other big lever. Arcus owns full rights to casdatifan outside Asia, which is a stark contrast to the TIGIT era where Gilead controlled significant economics on key programs. If casdatifan works, Arcus has more ways to win: keep it and build, partner it from a position of strength, or even explore a premium-valued strategic transaction.

And casdatifan isn’t the only shot still in the chamber. Quemliclustat in pancreatic cancer (PRISM-1) is another registrational swing, with Phase 3 results expected in 2027. On top of that, Arcus is trying to build a second leg of the company in inflammation and immunology, which—if it clicks—could diversify the business beyond oncology’s binary, high-volatility readouts.

Then there’s the partnership backstop. Even after STAR-221, Gilead remains deeply tied to Arcus, with a 33% ownership stake and ongoing collaboration on remaining programs. That relationship continues to offer what it offered in 2020: capital support, scientific validation, and a path to commercial scale that Arcus would struggle to replicate quickly on its own.

Finally, in biotech, management quality isn’t a soft factor—it’s often the difference between a company that survives long enough to be right and one that dies while it’s still “promising.” Arcus has already lived through the 2019–2020 near-death stretch, then absorbed the STAR-221 futility stop and pivoted decisively. That kind of scar tissue matters.

The balance sheet helps, too. With roughly $1 billion in cash and investments, Arcus expected to fund operations into at least the second half of 2028. That runway matters because it spans the next set of make-or-break readouts, lowering the odds that Arcus has to raise money at the worst possible time.

Bear Case:

The bear case is the one biotech never escapes: drug development is brutally hard, and Phase 3 is where optimism goes to die. Even if a drug gets approved, it still has to earn its place in the real world—against incumbents with entrenched prescribing habits, payer contracts, and years of comfort baked into guidelines.

STAR-221 also left a mark that’s hard to ignore. Arcus spent years arguing that its Fc-silent TIGIT approach would be the differentiated path through a mechanism that was already showing cracks elsewhere. That thesis didn’t just stumble; it effectively collapsed. For skeptics, that raises an uncomfortable question: was the problem TIGIT, or was it Arcus’s ability to pick winners?

Casdatifan, meanwhile, isn’t entering an empty field. Merck’s belzutifan (Welireg) is already approved for certain HIF-2α-driven conditions. Arcus believes casdatifan can be best-in-class, but without head-to-head data, the claim remains unproven—and competitors don’t stand still.

The Gilead deal is another double-edged sword. It kept Arcus alive and funded the portfolio, but it also shifted meaningful economics away from Arcus for optioned programs, especially outside the U.S. Casdatifan matters precisely because it sits outside that dynamic—yet the broader point remains: Arcus has already traded away upside to survive, including on programs that ultimately failed.

Then there’s the financial reality of clinical-stage biotech: the meter runs every day. Arcus reported losses of -$283.00 million, and if programs don’t create near-term value, dilution risk returns—no matter how disciplined management is.

Execution risk is real, too. Arcus has never launched a product. Manufacturing, supply, market access, and building a commercial organization (or negotiating who does what with partners) can break companies that get the science right.

And finally, the stock already reflects a comeback from the 2020 lows. At the current valuation, some level of success may already be baked in—meaning the upside can be capped, while downside scenarios are still very much alive.

Key Catalysts to Watch:

For investors tracking Arcus, several upcoming milestones will matter more than narratives:

- PEAK-1 Phase 3 data for casdatifan in kidney cancer (readout timing to be determined)

- PRISM-1 Phase 3 results for quemliclustat in pancreatic cancer (expected 2027)

- Additional ARC-20 data for casdatifan combinations (multiple readouts expected 2026)

- Inflammation and immunology programs entering the clinic (MRGPRX2 expected 2026)

- Partnership expansions or new collaborations

- Cash runway updates and any financing activity

XII. Lessons for Founders, Investors, and Strategists

Arcus’s story isn’t a neat morality play. It’s a real biotech story, which means it’s messy, nonlinear, and full of moments where smart people did the right things and still got punished by the data. That’s exactly why it’s so instructive.

Timing matters enormously. Arcus was born into the peak of immuno-oncology excitement—and then had to live through the hangover. When expectations ran ahead of evidence, the market eventually corrected, and companies without a cushion got crushed. Arcus’s big advantage wasn’t that it avoided the trough. It was that it found a way to finance itself before the trough became fatal.

Partnership strategy can be a survival tool—or a value destroyer. The Gilead collaboration bought Arcus time, capital, and credibility when those were in shortest supply. It was structured in a way that preserved meaningful control and kept Arcus from turning into a fire-sale story. But it also came with real trade-offs, especially outside the U.S. The lesson isn’t “always partner” or “never partner.” It’s that deal structure and timing decide whether a partnership is a lifeline or a long-term tax on your upside.

Scientific differentiation matters, but it isn’t a guarantee. Arcus didn’t build a “me too” PD-1 company. It went after harder biology: adenosine, TIGIT, and later HIF-2α. That willingness to be different is the only way a small company can matter in a field dominated by giants. But differentiation is not the same as validation. TIGIT largely broke across the industry. The adenosine pathway has produced mixed signals. HIF-2α looks more promising—but until pivotal data lands, it’s still a bet.

The long game requires resilience. Arcus’s journey—from post-IPO highs to sub-$3 lows to a real recovery—captures the psychological reality of biotech. Most people talk about “volatility” like it’s a chart pattern. For the teams living it, it’s a test of belief, focus, and stamina. You need runway to survive the calendar. And you need emotional durability to survive the narrative swings.

The portfolio approach has real trade-offs. Arcus’s multi-program strategy helped it avoid being a one-readout company. When TIGIT collapsed in a major setting, the company wasn’t left with nothing. But diversification comes at a cost: more trials, more complexity, and more burn. At times, running several swings at once can delay the moment when you finally commit fully to the best one.

Capital allocation discipline determines survival. The hardest skill in biotech isn’t starting programs. It’s stopping them. Cutting domvanalimab in upper GI cancers after STAR-221 wasn’t just a scientific decision—it was an operating decision that protected the rest of the company. The sunk-cost trap kills biotechs quietly: not with one dramatic failure, but with a slow bleed of resources into programs that no longer have a real path.

Leadership experience matters more than people want to admit. Arcus’s founders weren’t learning on the job. Terry Rosen and Juan Jaen had decades of experience, plus the credibility that came from Flexus’s $1.25 billion acquisition. In biotech, where the penalty for mistakes is measured in years and hundreds of millions of dollars, experience doesn’t guarantee success—but it can meaningfully improve the odds of surviving long enough to find it.

KPIs That Matter: If you’re tracking Arcus from here, a few indicators tell you far more than headlines do:

- Cash runway — Not just the balance, but whether it realistically covers the next major readouts. Arcus projected runway into 2028.

- Clinical trial enrollment progress — Are studies enrolling as planned, or slipping? Delays can be an early warning sign of execution or competitive issues.

- Efficacy signals like objective response rates and progression-free survival — These are the numbers that ultimately decide whether a story becomes a drug.

XIII. The Future: What Happens Next?

The next 12 to 24 months are the hinge point for Arcus. The company has made its choice—casdatifan is now the lead story—but a pivot only counts if the clinic agrees.

By mid-2026, Arcus expects more mature ARC-20 combination data for casdatifan plus cabozantinib in immuno-oncology-experienced patients, directly connected to the logic behind PEAK-1, its ongoing Phase 3 effort in that setting. In the second half of 2026, Arcus expects initial ARC-20 data in earlier-line patients, along with a go/no-go decision on whether to move into the Phase 3 portion of eVOLVE-RCC02. And by late 2026, the company has left the door open to starting a registrational Phase 3 trial in early- or first-line clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

Scenario analysis:

Best case: Casdatifan delivers best-in-class efficacy in Phase 3, earns approval, and grows into a blockbuster in kidney cancer—one of the more commonly diagnosed cancers in the U.S., with an estimated 81,600 Americans diagnosed in 2024. Clear cell RCC is the dominant subtype in adults, and the stakes in metastatic disease remain brutal: for advanced or late-stage metastatic RCC, the five-year survival rate is only 15%. In this upside scenario, quemliclustat also reaches the market in pancreatic cancer, the inflammation programs enter the clinic cleanly, and Arcus either becomes an acquisition target at a meaningful premium or builds the commercial infrastructure to operate independently.

Base case: One program succeeds—most likely casdatifan—but in a narrower slice of patients and indications than the bull case imagines. Sales are real but not explosive. Arcus becomes a clinical-stage and early-commercial hybrid: advancing its next wave of assets while still needing periodic capital raises, but with enough traction to keep compounding value.

Worst case: Pivotal trials disappoint across the portfolio. Partnerships are renegotiated from a weaker position. The company is forced into heavily dilutive financing, and the endgame becomes either an acquisition at a discount to the current valuation or a more dramatic retrenchment of operations.

Independence hangs over all of these outcomes. With roughly a third of the company, Gilead could, in theory, acquire Arcus outright. But its appetite may have changed after the TIGIT failure, and it chose not to exercise its option on casdatifan. If casdatifan’s data proves compelling, other large pharma players—Merck, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca—could view Arcus’s kidney cancer position as strategically valuable.

Broader industry context:

Arcus is operating in a biotech landscape that’s shifting under everyone’s feet. AI-driven drug discovery could increase the pace of competition by shrinking the time and cost required to generate new candidates. Consolidation is also accelerating as large pharma looks to refill pipelines ahead of major patent expirations and competitive threats—Keytruda, for example, faces biosimilar competition starting in 2028.

At the same time, the trend lines Arcus has been betting on are only getting stronger. Personalized medicine keeps pushing oncology toward biomarker-informed patient selection, an approach Arcus has already been incorporating into development. And the field continues to move toward combination regimens. That can be a headwind when you’re trying to build “standalone” combinations internally—but it’s also an opening for any asset that’s well characterized, differentiated, and clean enough to become a component in tomorrow’s standard of care.

XIV. Epilogue and Reflections

The emotional rollercoaster of biotech is hard to explain to anyone who hasn’t lived through it. A stock chart makes it look abstract—just candles and headlines. But every swing hides the real story: cancer patients betting on an experimental drug, scientists spending years on a mechanism that might go nowhere, investors underwriting binary outcomes, and leadership teams forced to choose between imperfect options with incomplete information.

Arcus matters because it isn’t a one-off. It’s a clean example of what hundreds of biotech companies attempt in every cycle: take a scientific idea that might change medicine, push it through the unforgiving machinery of clinical trials, and try to stay solvent long enough to find out whether it’s real. Most companies don’t. Some do. And even the ones that survive often do it with scars.

In that context, Arcus has already accomplished something nontrivial. It lived through the harshest part of the arc—post-IPO optimism, the slide into skepticism, the near-death funding dynamics of 2019–2020—and it kept producing real clinical data across multiple mechanisms. In biotech, where so many ventures end without a meaningful readout, that alone separates “a story” from “a footnote.”

The human element is the part that can’t get lost. Patients in trials aren’t data points. They’re people with families making high-stakes decisions under time pressure. The Phase 3 STAR-221 futility stop wasn’t just a narrative reset for Arcus; it meant that, in that setting, a domvanalimab-based regimen didn’t help patients with upper GI cancers live longer than an existing option. That’s disappointing for investors. For patients who enrolled hoping for something better, it’s far more than that.

The most striking thing in Arcus’s story is its resilience through the 2019–2020 crisis. When a stock collapses and the market starts treating your thesis as broken—especially in a field as fashionable, crowded, and fragile as immuno-oncology—continuing to execute is not automatic. It takes discipline, conviction, and a willingness to keep doing the work when applause disappears. Arcus kept going, and while some of its bets didn’t pan out, others did enough to keep the company alive and evolving.

And then there’s the deal that changed the trajectory: the Gilead partnership. Getting hundreds of millions in upfront funding and long-term support at a moment when Arcus badly needed oxygen—while still preserving meaningful control and avoiding an outright sale—wasn’t luck. It was elite deal-making. It bought Arcus the rarest commodity in biotech: time.

The final thought is simple. Building a biotech company is not for the faint of heart. It demands conviction about biology that may prove wrong, financial creativity to survive a decade-long development clock, operational excellence across complex global trials, and the stomach to endure volatility when the data refuses to cooperate.

Arcus has shown those qualities for nearly a decade. Whether casdatifan, quemliclustat, or its emerging inflammation and autoimmune portfolio ultimately delivers the approvals and commercial success that make the whole journey feel inevitable—that part of the story still has to be written by clinical data that hasn’t arrived yet.

XV. Further Reading and Resources

If you want to go deeper on Arcus—and on the broader immuno-oncology context it was built inside—these sources are the best starting points. They’re where the details live: the actual trial designs, the partnership terms, and the clinical updates that move the story from narrative to evidence.

Company Materials: - Arcus Biosciences investor presentations (arcusbio.com/investors) — The company’s own view of the pipeline, strategy, and evolving data - SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q) — The unfiltered record: financials, risk factors, and how the partnerships are actually structured - Clinical trial registrations (clinicaltrials.gov) — Study protocols for PEAK-1, PRISM-1, and other ongoing trials, including endpoints and enrollment plans

Partnership Documentation: - Gilead–Arcus collaboration press releases (2020, 2021, 2024) — How the deal was framed, expanded, and amended over time - AstraZeneca collaboration announcements — Structures and rationale for PACIFIC-8 and eVOLVE-RCC02

Scientific Background: - Nobel Prize materials on James Allison and Tasuku Honjo — The origin story of checkpoint inhibition - Conference presentations (ASCO, ESMO, SITC) — The cadence of biotech truth: interim updates, subgroup analyses, and competitive comparisons - Key peer-reviewed publications (NEJM, Lancet Oncology, Journal of Clinical Oncology) — The primary literature behind immunotherapy mechanisms and trial outcomes

Industry Context: - BioPharma Dive, Endpoints News, STAT+ — Reporting on the TIGIT wave of setbacks, the HIF-2α landscape, and how sentiment shifts in real time - Analyst reports from major investment banks — Useful for framing competitive dynamics and market expectations (with the usual caveats) - Patent filings (USPTO) — Where you can trace intellectual property around key molecules and understand what exclusivity might look like

Leadership Background: - Terry Rosen interviews and profiles — How the company’s strategy was shaped by its founders’ prior cycles through biotech - Flexus Biosciences acquisition materials — Context for the $1.25 billion exit that helped set Arcus in motion

The Arcus story is still being written by data. The next wave of readouts will decide whether the company fulfills its founding ambition: building therapies that meaningfully extend—and improve—patients’ lives. Until then, Arcus remains a classic clinical-stage biotech proposition: experienced leadership, a strengthened balance sheet, and a pipeline where the upside is real—but never guaranteed.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music