Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical: Engineering Solutions for the Rarest Diseases

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

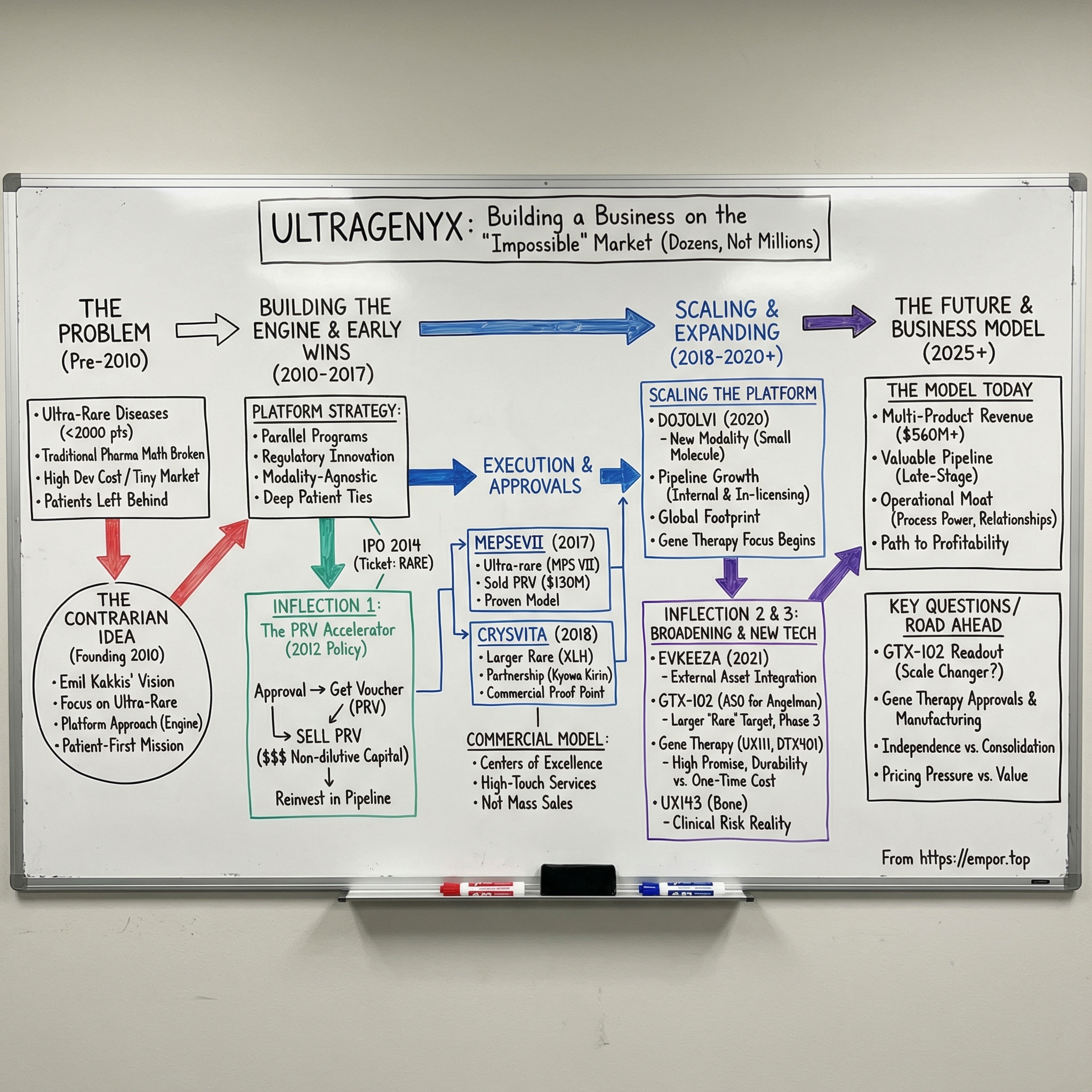

Picture a pediatrician at a bedside, watching a child with an ultra-rare genetic disease steadily lose ground. The science might be knowable. The biology might even be treatable. But the cold reality is that “the market” could be a couple hundred patients worldwide—far too small for traditional pharma math to work.

Now picture that same doctor deciding the math is the wrong constraint. And then deciding to build an entire company around proving it—again and again, not for one disease, but for many.

Ultragenyx Pharmaceutical was founded in 2010 by Emil Kakkis, a pediatrician-scientist whose career had been shaped by rare disease drug development: early work at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, leadership as chief medical officer at BioMarin, and advocacy through founding the EveryLife Foundation. Ultragenyx grew out of that mix of clinical frustration and hard-won know-how. From day one, it made a deliberately contrarian choice: focus on diseases so rare that most physicians would never see a single patient in their entire careers.

Fast-forward to today, and the “impossible” has turned into a real operating business. For the year ended December 31, 2024, Ultragenyx reported $560 million in revenue, up 29% from the prior year. It commercializes four approved therapies and has built what management calls one of the most valuable late-stage pipelines in rare disease. With pivotal Phase 3 results expected in osteogenesis imperfecta and enrollment completion anticipated in its Phase 3 Angelman syndrome trial, Ultragenyx believes it could be on track to launch three to four new therapies over the next couple of years—potentially growing to eight to nine approved products over a 10-year span.

The question at the center of this story is simple to ask and brutal to answer: how do you build a sustainable company when your total addressable market isn’t millions of people, or even tens of thousands, but sometimes a few dozen?

Ultragenyx’s answer is a blend of regulatory innovation, platform thinking, and operational discipline—turning what looks economically irrational into something repeatable. This is a story about scientific audacity meeting business model engineering; about using the system as it exists, while helping reshape it; and about what happens when a company commits, completely, to patients medicine has historically left behind.

And along the way, there are lessons—for founders, for investors, and for anyone interested in where capitalism, science, and human compassion collide.

II. The Rare Disease Landscape & Founding Context

To understand why Ultragenyx exists at all, you have to start with the economics that made rare disease drug development feel like a dead end for most of pharmaceutical history.

In the United States, a disease is “rare” if it affects fewer than 200,000 people. But inside that bucket is a much harsher category: ultra-rare diseases, generally affecting fewer than 20,000 patients—and often dramatically fewer.

Take MPS VII, also called Sly syndrome. It’s one of the rarest mucopolysaccharidosis disorders, affecting an estimated 200 patients in the developed world. That number matters because it breaks the standard pharma spreadsheet. If development costs can reach into the hundreds of millions and your entire addressable market is measured in the low hundreds, the math doesn’t just look unattractive—it looks impossible.

Congress tried to change that equation with the Orphan Drug Act of 1983. It offered tax credits, marketing exclusivity, and regulatory support to encourage companies to develop therapies for rare conditions. It worked, to a point: activity increased, and the industry learned how to navigate approvals for small populations. But for the truly ultra-rare diseases, even those incentives often weren’t enough to make a program financeable.

Then came Genzyme. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the company proved something that investors and drug developers needed to see with their own eyes: enzyme replacement therapies for lysosomal storage disorders could generate substantial revenue despite tiny patient populations—if pricing reflected the reality of the market, and if patients stayed on therapy for life. It wasn’t just a scientific breakthrough. It was a business-model breakthrough.

This was the backdrop for Emil Kakkis’s early work in the field. He began developing an enzyme replacement therapy for MPS I that would eventually become Aldurazyme®. The program started with minimal funding and support, and getting from a successful canine model to human patients was anything but straightforward. A key inflection point was financial backing from the Ryan Foundation, created by Mark and Jeanne Dant for their son Ryan. Later, BioMarin and Genzyme supported development, and Aldurazyme ultimately received FDA approval in 2003.

That experience left Kakkis with two convictions that would shape everything that followed. First: these diseases were treatable, even when the world assumed they weren’t. Second: without committed partners—patient organizations, regulators willing to adapt, and companies willing to do the hard work—the treatments would never reach the patients who needed them.

Before Ultragenyx, Kakkis worked at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, where he developed enzyme replacement therapy efforts in MPS I. He later became Chief Medical Officer at BioMarin, helping lead development programs in rare disorders including MPS VI and PKU. He wasn’t just learning the science; he was learning the mechanics of getting a therapy through trials, through regulators, and into clinics that might see only a handful of patients.

In early 2009, he founded the EveryLife Foundation to accelerate biotech innovation for rare diseases. The foundation launched the CureTheProcess Campaign, aimed at improving the regulatory and clinical development process for rare disease therapies. In 2010, Kakkis worked with the FDA and Congress to push for reforms that culminated in the Brownback Brown Amendment to the 2010 FDA appropriation bill—language requiring the FDA to review its rare disease regulatory policies and identify ways to improve them.

And the timing mattered. By 2010, several forces were converging: genomics was making the biology of many diseases more legible, regulators had built precedents from Genzyme and BioMarin that created viable approval pathways, and venture capital had begun to believe rare disease programs could be real businesses.

So when Kakkis founded Ultragenyx in 2010, the company carried an explicit patient-first mission: deep engagement with patients and caregivers to understand what families actually needed. But under that mission was a deliberately contrarian operating idea. Instead of betting the company on one rare disease and hoping it hit, what if you built an organization designed to do this repeatedly—an infrastructure that could efficiently develop therapies across many rare diseases at once?

III. The Platform Vision: Building the Rare Disease Factory

Ultragenyx’s founding thesis was a quiet rebellion against the standard biotech playbook.

Back then, most biotech companies were single-asset moonshots: one lead program, one indication, one make-or-break clinical readout. Emil Kakkis and his team wanted something closer to an engine—an organization built to run multiple rare disease programs in parallel, and to get better every time it did. The idea wasn’t just “let’s work on rare diseases.” It was: if you build the right infrastructure once—regulatory know-how, clinical operations built for tiny populations, manufacturing for small batches, and eventually a specialized commercial footprint—you can reuse it over and over across entirely different disorders.

Kakkis founded Ultragenyx in 2010 to focus on rare metabolic, bone, muscle, and neurologic diseases with limited treatment options. From the beginning, the company operated across multiple drug modalities, including biologics, small molecules, gene therapies, and newer approaches like antisense oligonucleotides and mRNA—applied across bone, endocrine, metabolic, muscle, and CNS diseases.

That “modality-agnostic” stance was contrarian in its own right. Many biotechs organized themselves around a single scientific tool—antibodies, small molecules, later gene therapy—and then hunted for diseases that fit the tool. Ultragenyx flipped it: start with the disease biology and the unmet need, then pick the therapeutic approach that actually fit the problem.

The early team reflected the ambition. Kakkis began in academia in Southern California, then moved to the North Bay in 1998. He spent years at BioMarin in San Rafael before starting Ultragenyx, and much of the early Ultragenyx team shared that BioMarin background—people who had already lived through the practical realities of rare disease development: finding patients, negotiating endpoints, working with regulators, and building trust with families who had been told “there’s nothing we can do.”

Then came the funding. Ultragenyx raised a $45 million Series A in June 2011, co-led by Fidelity Biosciences and TPG Biotech, with participation from OrbiMed Advisors, Sofinnova Ventures, and Pappas Capital, to fund preclinical research and push early programs forward. A Series B followed, bringing total early venture funding to over $120 million before the company went public.

The pitch was not “this one molecule will change everything.” It was “productive efficiency”: the belief that a dedicated rare disease platform could develop therapies faster and more effectively than a big pharma organization built for mass markets, or an academic ecosystem built for discovery rather than execution. Concentrate the expertise. Standardize what can be standardized. Build repeatable relationships with regulators and patient communities. Create economies of scope, even if true scale economics are hard when your “market” is a few hundred people.

Those patient relationships weren’t window dressing—they were core operating infrastructure. In ultra-rare disease, patients are dispersed globally, frequently undiagnosed or misdiagnosed, and often only reachable through the small foundations and caregiver networks that keep the community together. As Kakkis put it: "I've had the opportunity to support families touched by rare diseases for more than two decades. I have been present when the first patients were successfully treated with new medications for conditions that previously had no therapies, and those moments have deeply impacted me and are part of the reason I founded Ultragenyx. At Ultragenyx, our goal is to create those moments for more patients with rare diseases."

Finally, Ultragenyx built its pipeline the way a rare disease company almost has to: a mix of internal development and in-licensing from academic institutions. Many of the best ideas in rare disease start in university labs—built by researchers who understand the biology deeply but don’t have the capital, regulatory experience, or operational machinery to turn a discovery into an approved medicine. Ultragenyx positioned itself as the bridge: take promising science, and bring the execution.

Looking back, this founding strategy is still the through-line. The platform approach didn’t just produce a pipeline—it created a repeatable way to build one. And in rare disease, where trust and process matter as much as molecules, the relationships and operating muscle built over years can be just as defensible as the drugs themselves.

IV. First Inflection Point: The Rare Pediatric Disease PRV Program

In 2012, Congress introduced a policy lever that quietly rewired the business case for pediatric rare disease drugs: the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher, or PRV. For a company like Ultragenyx—building a pipeline in markets measured in dozens or hundreds of patients—this wasn’t a footnote. It was rocket fuel.

Here’s how it worked. Get an FDA approval for a therapy that treats a qualifying rare pediatric disease, and the FDA issues you a voucher. That voucher lets you put any future drug application on a faster review clock—moving from the typical ten months down to six. But the real twist, and the real economic engine, is that the voucher is transferable. You can sell it.

And buyers were willing to pay. The logic is simple: four months can be everything for a high-revenue drug. So the PRV became a tradable asset with a very real price tag—sometimes massive. AbbVie, for example, paid United Therapeutics $350 million in 2015 for a voucher. And later, Gilead Sciences paid $125 million to Sarepta Therapeutics for one.

That changed the math for Ultragenyx overnight. In an ultra-rare indication, even a successful product might top out at “meaningful but not huge.” A PRV, on the other hand, could deliver a one-time payout on the order of $100 million or more. Suddenly, each approval had two sources of value: the ongoing revenue from treating patients, plus a potential cash infusion from selling the voucher.

This wasn’t just helpful—it was a new financing mechanism for diseases that had always failed the spreadsheet test. A therapy for a couple hundred children could be hard to justify on product revenue alone. Add the prospect of a large voucher sale, and the same program starts to look investable. The PRV program didn’t eliminate scientific risk, but it made the reward side of the equation big enough to attract real capital.

Investors took notice. Ultragenyx went public in January 2014 on NASDAQ under the ticker RARE—before it had any product approvals. Since January 31, 2014, Ultragenyx’s market cap has increased from $1.19B to $3.23B. The IPO was a bet on the platform—and on the idea that the regulatory system itself had finally created an economic bridge to patients who’d been left behind.

Not everyone loved the program. Critics argued it looked like a loophole: a company could earn a voucher by serving a tiny population, then sell that voucher to accelerate review for a blockbuster drug that had nothing to do with rare disease. But from Ultragenyx’s point of view, that was the whole point. Congress had created an incentive to do work the market wouldn’t fund—and the PRV did exactly that.

It also shaped strategy. Pediatric rare disease programs became especially valuable, because they didn’t just offer the chance to help underserved families; they also offered PRV eligibility. Ultragenyx increasingly built its pipeline and development sequencing with that reality in mind—seeking to capture PRV opportunities while staying aligned with the mission that launched the company in the first place.

V. Building the Engine: Pipeline Assembly & Clinical Execution

Between 2013 and 2017, Ultragenyx moved from an idea—“a platform for ultra-rare diseases”—to something far harder: an execution machine. This was the unglamorous work of running multiple programs at once, building a team that could operate at speed, and learning, over and over, how to develop drugs when the patient population is smaller than a typical clinical trial site.

The sprint to clinic was the platform thesis made real. Instead of pushing one “lead asset” and hoping it worked, Ultragenyx advanced several candidates in parallel. Every program became both a shot on goal and a source of process learning: how to find patients, how to design endpoints, how to manufacture tiny volumes, and how to work with regulators when the textbook playbook doesn’t apply.

That effort culminated in a milestone on November 15, 2017, when Ultragenyx announced that the FDA had approved MEPSEVII™ (vestronidase alfa), the first medicine approved for children and adults with Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (MPS VII, Sly syndrome). MEPSEVII is an enzyme replacement therapy designed to replace the deficient lysosomal enzyme beta-glucuronidase in MPS VII patients.

The MEPSEVII program also exposed the core paradox of ultra-rare drug development. MPS VII is one of the rarest MPS disorders, with an estimated 200 patients in the developed world. You can’t run a conventional Phase 3 trial with large placebo-controlled arms when the entire global population barely fills a few conference rooms. So Ultragenyx had to help invent a different way to prove a drug works.

That meant leaning on tools that were still evolving at the time: adaptive trial designs, comparisons to natural history data, and endpoints built to reflect what actually changes in the lives of these patients. As Kakkis put it, “The approval of MEPSEVII is a pivotal moment for Ultragenyx and for patients suffering from ultra-rare genetic diseases for which the investment and development of treatments has not happened yet.” He emphasized that the development program aimed “to create a new paradigm in study design and endpoint evaluations” to fit the realities of ultra-rare conditions.

While MEPSEVII was proving the model in enzymes, Ultragenyx was also widening the platform through dealmaking. The company pursued acquisitions and in-licensing with a consistent filter: clear biology, high unmet need, and no approved therapies. In 2017, Ultragenyx paid $151 million to acquire Dimension Therapeutics, outbidding Regenxbio, to secure rights to DTX301 and DTX401—bringing gene therapy programs into the fold and signaling that this wouldn’t be a one-modality company.

Then there was manufacturing—the part of rare disease biotech that rarely makes headlines, but often determines whether a company can scale at all. Traditional pharma manufacturing gets cheaper as volume rises. Ultra-rare diseases invert that logic: an annual supply might treat fewer than fifty patients. Ultragenyx built manufacturing approaches meant for small-batch economics, prioritizing flexibility and repeatability over brute scale.

And even before manufacturing, you have to find the patients. When the global population is in the hundreds, “recruitment” isn’t marketing—it’s detective work. Ultragenyx built relationships with patient advocacy foundations, specialty centers, and academic researchers who effectively served as the map of where patients were, and the trust layer that made enrollment possible.

All of this forced a different kind of relationship with regulators, too. Rare disease applications had long been met with skepticism about whether the data could ever be “enough.” Ultragenyx worked to make the FDA a partner in solving the constraints: educating reviewers on what was feasible, proposing novel endpoints and designs, and still holding the line on scientific rigor. In ultra-rare diseases, the regulatory strategy isn’t an afterthought—it’s part of the product.

VI. Second Inflection Point: First Approvals & Commercial Proof Point

By 2017 and 2018, Ultragenyx crossed the line that separates most biotechs from the few that become enduring companies: it stopped being “a pipeline” and became a business. The approvals mattered, of course. But the bigger proof was commercial: could Ultragenyx actually find these patients, deliver the drug, get it reimbursed, and support families—at a scale where “the market” might be a few dozen people?

On November 15, 2017, the FDA approved Mepsevii (vestronidase alfa-vjbk) for pediatric and adult patients with MPS VII, also known as Sly syndrome. The FDA reviewed the application under Priority Review, a designation reserved for therapies that offer meaningful advances, or where no adequate option exists. And the approval came with something that, for Ultragenyx, was almost as important as the label itself: a Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Review Voucher.

Ultragenyx moved quickly to turn that voucher into fuel. The company entered a definitive agreement to sell its PRV to Novartis for $130,000,000. Emil Kakkis called it “an important source of non-dilutive capital” that could be put right back into advancing the pipeline—and, by extension, accelerating how quickly future therapies could reach patients.

Then came the other hard part: launching a drug for a disease so rare that traditional commercial logic simply doesn’t apply. On a November 15 conference call, Ultragenyx said it planned to price Mepsevii at about $375,000 per year—below what many analysts had expected. But even at that level, no one was pretending this would ever be a mass-market product. Sly syndrome affects only about 150 people worldwide, so the ceiling was always going to be defined by biology, not sales execution.

The launch forced Ultragenyx to throw out the standard pharmaceutical playbook. You don’t build a traditional sales force when the relevant treatment centers around the world number in the dozens. Instead, the company leaned heavily into medical affairs and patient services—work that looks less like “selling” and more like making the therapy usable in real life: driving disease awareness, helping identify patients, supporting treatment centers, and navigating the reimbursement maze.

Ultragenyx said Mepsevii would be available to U.S. patients later that month. While the company didn’t formally disclose a list price in that announcement, public projections had put the annual cost as high as $400,000. To support families, Ultragenyx launched UltraCare™, a service designed to help patients and caregivers obtain coverage and access financial support for both the medication and its administration. In ultra-rare disease, this is the product as much as the vial is: if families can’t get the drug approved and delivered, it might as well not exist.

And then, in 2018, Ultragenyx got something different—still rare, still specialized, but enormous by its standards.

On April 17/18, 2018, Ultragenyx and its partners Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd and Kyowa Kirin International PLC announced FDA approval of Crysvita (burosumab-twza) for X-linked hypophosphatemia (XLH) in adult and pediatric patients one year of age and older. XLH was “large” in Ultragenyx terms: roughly 12,000 patients in the United States alone. Crysvita also received a positive European Commission decision granting conditional marketing authorization for children and adolescents with growing skeletons who had radiographic evidence of bone disease.

Crysvita was built on partnership. Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Kyowa Kirin International, and Ultragenyx collaborated globally under their existing collaboration and license agreement—giving Ultragenyx access to a much bigger commercial opportunity while sharing both the development burden and the realities of worldwide commercialization.

Execution was immediate. Crysvita entered the U.S. commercial supply chain and generated its first sales to specialty pharmacies on April 27, 2018—just ten days after FDA approval. It was a small detail with big meaning: Ultragenyx could not only get drugs approved, it could launch them cleanly—an operational skill that would compound as the portfolio grew.

Out of these first two launches, Ultragenyx’s commercial template came into focus: a center-of-excellence model rather than mass prescribing, medical affairs depth over sales force breadth, patient navigation services that solved reimbursement and logistics, and a long-term relationship with patients and families instead of a transactional “script count” mindset. In ultra-rare disease, that wasn’t just a go-to-market strategy. It was the business model.

VII. Scaling the Platform: The 2018-2020 Expansion

With two approved products on the market and a commercial playbook that actually worked, Ultragenyx moved into the next, harder phase: expansion. Not the exciting kind you can brute-force with a bigger sales team, but the kind that stress-tests whether a “platform” is real—whether the company can absorb more programs, more geographies, and more scientific modalities without losing the execution discipline that got it this far.

In June 2020, the FDA approved Dojolvi (triheptanoin) for long-chain fatty acid oxidation disorders (LC-FAOD). The science was different from what had come before. Triheptanoin is a synthetic medium-chain triglyceride made of three odd-chain, seven-carbon fatty acids. For patients with LC-FAOD—where defects in mitochondrial beta-oxidation disrupt the body’s ability to break down long-chain fats—those defects can translate into energy crises, muscle breakdown, and serious organ complications. Dojolvi works as an alternative energy source, supplying heptanoate that is rapidly metabolized to generate acetyl-CoA and support the Krebs cycle.

Strategically, the approval mattered for another reason: it proved Ultragenyx wasn’t a “biologics company.” Mepsevii and Crysvita were injectable proteins; triheptanoin was a specialized triglyceride with different manufacturing and supply requirements. Same mission, different tool. That was the platform thesis in action—pick the modality that fits the disease, then execute.

Meanwhile, Ultragenyx kept squeezing more value out of what it already had. Crysvita’s label expanded to include tumor-induced osteomalacia (TIO), adding a second indication. On June 18, 2020, the FDA approved Crysvita for the treatment of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23)-related hypophosphatemia in TIO associated with phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors that can’t be curatively resected or localized, in adults and pediatric patients two years of age and older. It was a textbook example of a “strategy of indications”: once you’ve built the clinical, regulatory, and commercial foundation for a therapy, you look for adjacent diseases with shared biology where that foundation can carry you further.

At the same time, the company pushed deeper into gene therapy. Ultragenyx reported positive longer-term safety and efficacy data from the first three cohorts of its ongoing Phase 1/2 studies for DTX401, an investigational adeno-associated virus (AAV) gene therapy for Glycogen Storage Disease Type Ia (GSDIa), and DTX301, an AAV gene therapy for ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency.

Gene therapy wasn’t just “another program.” It hinted at a different endpoint for the entire rare disease business model. Chronic therapies—enzyme replacement, repeat dosing—create recurring revenue, but they also mean a lifetime of administration. Gene therapies offered the possibility of a one-time, potentially curative treatment. The economics shift with that promise: higher upfront prices, different payer dynamics, and none of the predictability of annual dosing. The operations shift too, especially manufacturing. Ultragenyx leaned into that reality and invested in building in-house gene therapy manufacturing capabilities. In 2020, it announced plans for a new gene therapy plant near Boston.

Ultragenyx also kept widening its footprint outside the U.S. and Europe. After winning regulatory clearance for Mepsevii in Brazil, the company framed it as both patient impact and strategy: “This approval in Brazil is an important milestone, particularly for children with this progressive and debilitating disorder, and also for Ultragenyx because it marks the first regulatory clearance for this important medicine outside of the U.S. and Europe. Occurring less than one year after Mepsevii was approved in the U.S., this approval validates our strategic plan to rapidly expand into other regions of the world, including Latin America.”

Then COVID hit—and for a company that depends on specialty centers, infusions, and tightly coordinated care, it could have been a disaster. Instead, the rare disease ecosystem showed why Ultragenyx had always treated patient community engagement as infrastructure, not messaging. Advocacy groups mobilized to protect continuity of care, and Ultragenyx adapted its commercial and support model to virtual engagement. The logistics changed. The mission didn’t.

VIII. Third Inflection Point: Evkeeza Acquisition & Gene Therapy Evolution

By early 2021, Ultragenyx was proving it could scale in two directions at once: broaden the portfolio through smart in-licensing, and keep pushing into higher-risk, higher-upside modalities like gene therapy. February brought a clear signal of that strategy in action.

That month, the FDA approved Evkeeza (evinacumab) for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH), the most severe form of familial hypercholesterolemia. Regeneron discovered and developed the drug, and launched it in the U.S. immediately after approval. HoFH is brutally rare—about 1,300 people in the U.S.—which made it a natural fit for Ultragenyx’s ultra-specialist operating model.

Soon after, Regeneron and Ultragenyx announced a license and collaboration agreement giving Ultragenyx the rights to clinically develop, commercialize, and distribute Evkeeza outside the U.S. That included the European Economic Area, where Evkeeza was approved in June 2021 as a first-in-class therapy used alongside diet and other LDL-C-lowering treatments for adults and adolescents aged 12 and older with HoFH.

The economics were straightforward and very “platform Ultragenyx.” Regeneron would receive $30 million upfront, with the potential for up to $63 million more tied to regulatory and sales milestones. For Ultragenyx, the point wasn’t just one more product. It was proof the company could plug an external asset into its existing rare-disease infrastructure and make it go—especially internationally, where the operational work is often harder than the science.

At the same time, the gene therapy portfolio continued to show why Ultragenyx had been willing to spend for Dimension back in 2017. In DTX401, an AAV gene therapy for Glycogen Storage Disease Type Ia (GSDIa), nine patients across Cohorts 1, 2, and 3 continued to show improved glucose control, with some tapering or discontinuing oral glucose replacement with cornstarch up to three years after dosing.

DTX301, the AAV gene therapy for ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency, also showed encouraging durability in responders. The longest-treated responders demonstrated sustained benefit out to about four years after dosing, including up to 3.5 years after discontinuing ammonia-scavenger medications and liberalizing protein-restricted diets. For gene therapy, that kind of multi-year durability isn’t a footnote—it’s the whole point. If you’re going to ask the system to pay for a one-time treatment, you have to show the benefit lasts.

But this chapter also underscored the reality that “cutting edge” cuts both ways. Safety concerns across the broader gene therapy field—including serious adverse events reported elsewhere—hung over the entire category, and Ultragenyx had to navigate that environment carefully. The company emphasized patient safety and continued to communicate with investors as the field wrestled, in public, with how to balance promise against risk.

Then came another strategic broadening: antisense oligonucleotides. In July 2022, Ultragenyx announced it would exercise its option to acquire GeneTx Biotherapeutics for $75 million upfront, plus up to $115 million more in potential milestone-based payments. The centerpiece was GTX-102, an antisense oligonucleotide therapy in early-stage development for Angelman syndrome. The acquisition closed in August 2022, adding yet another modality to Ultragenyx’s toolkit—one aimed not at metabolic pathways or bone biology, but at the central nervous system.

As the portfolio diversified, manufacturing strategy had to diversify with it. Ultragenyx continued to balance in-house capabilities with contract manufacturing organization relationships, building the hybrid approach that most multi-product rare disease companies eventually converge on: own what’s strategically essential, partner where flexibility and speed matter, and keep the entire system reliable enough to serve patient populations that can’t afford disruption.

IX. The UX143 Setrusumab Program & Clinical Risk

If the early Ultragenyx story was about proving ultra-rare drugs could be built and launched at all, setrusumab, also known as UX143, showed the next-level challenge: what happens when you go after a larger disease by Ultragenyx standards—and you still have to live with the same unforgiving truth of biotech. Late-stage trials are where confidence meets reality.

Setrusumab is being developed for osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), a group of genetic disorders that disrupt bone metabolism and leave patients with brittle bones and a high risk of fractures. In most cases—roughly 85% to 90%—OI is driven by variants in COL1A1 or COL1A2, genes tied to collagen production. When collagen is reduced or abnormal, bone strength suffers. Patients can experience repeated fractures, low bone mineral density, bone deformities, abnormal spine curvature, pain, reduced mobility, and short stature. Despite the severity and lifelong burden, there are no globally approved treatments for OI. Ultragenyx estimates the disease affects about 60,000 people in commercially accessible geographies—large enough to matter financially, and serious enough to matter clinically.

By late 2024, the program had real momentum. Ultragenyx announced that enrollment was complete across two pivotal Phase 3 trials: Orbit and Cosmic. Orbit randomized 158 patients ages 5 to 25, while Cosmic enrolled 66 younger patients ages 2 to under 7. This was the kind of operational feat the platform was built for—coordinating large, international rare disease trials where every patient is precious and every site matters.

Regulators leaned in, too. In October 2024, the FDA granted UX143 Breakthrough Therapy Designation, based on preliminary clinical evidence that included positive 14-month results from the Phase 2 portion of the Orbit study. Those data showed a rapid and clinically meaningful decrease in fracture rate, a result strong enough to earn the program closer guidance from the FDA.

But then came the reminder that Breakthrough Therapy Designation is not a guarantee, and Phase 2 is not Phase 3.

In 2025, Ultragenyx said the Phase 3 portion of Orbit was progressing toward its final analysis on the original timeline—around the end of the year. The company had hoped the study might stop early, but it didn’t. The Data Monitoring Committee met and told Ultragenyx that UX143 showed an acceptable safety profile and that the trial should continue to the final analysis.

Emil Kakkis framed it in the way rare disease leaders often have to: confident in the biology, patient about the data. “Based on the feedback we hear from investigators and families who participated in the studies, we are confident that increasing bone mass leads to stronger bone, less fractures, and improved physical abilities,” he said. “While we had hoped to be able to stop the study early, we look forward to having results from [Orbit] around the end of this year.”

In other words: no victory lap yet. The Phase 3 portion completed enrollment in April 2024, and Ultragenyx expected top-line data before the end of 2025. It was a moment that captured the real risk profile of the entire business. Even with encouraging earlier data and strong regulatory support, pivotal outcomes can’t be wished into existence.

And it also highlighted why Ultragenyx built a platform in the first place. For investors, setrusumab is the cleanest case study in both upside and uncertainty. A successful Phase 3 readout could open a meaningful new franchise. But even if it disappoints—or simply takes longer than hoped—the company isn’t a single-asset bet. The rest of the portfolio keeps moving.

Setrusumab is being developed through a global collaboration with Mereo BioPharma under an existing collaboration and license agreement. That partnership includes potential additional milestone payments of up to $245 million, plus royalties to Mereo on commercial sales in Ultragenyx territories.

X. Recent History: The Modern Portfolio & GTX-102

The next era of Ultragenyx is being shaped by two parallel bets: turning GTX-102 into a first-in-class treatment for Angelman syndrome, and pushing its most advanced gene therapy programs over the line into regulatory filings.

If GTX-102 hits, it could be the biggest commercial opportunity Ultragenyx has ever had. Angelman syndrome is estimated to affect roughly 60,000 people in commercially accessible geographies. That’s still “rare,” but it’s a very different kind of rare than MPS VII. This is the first time Ultragenyx has had a shot at something that could scale more like a franchise than a handful of patients scattered across the globe.

The Phase 3 Aspire study evaluating GTX-102 (apazunersen) in Angelman syndrome is fully enrolled. It includes approximately 129 participants, ages four to 17, all with a genetically confirmed diagnosis of full maternal UBE3A gene deletion.

In June 2025, the FDA granted Breakthrough Therapy Designation to GTX-102 (apazunersen) for Angelman syndrome—an important signal that regulators saw enough early promise to lean in with closer guidance.

“The accelerated enrollment of the Phase 3 Aspire study underscores the urgent need and strong desire for an effective treatment for these patients. Support from the Angelman syndrome community was critical to the achievement of this important milestone for GTX-102 with completion of enrollment in seven months. We are grateful to the study site teams, investigators, and families for their dedication and support,” said Eric Crombez, M.D., chief medical officer at Ultragenyx.

Ultragenyx expects study completion in the second half of 2026, and says it plans to move with urgency to deliver topline data and advance toward a regulatory submission. GTX-102 is an investigational antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) delivered by intrathecal administration. It’s designed to target and inhibit expression of UBE3A-AS, with the goal of preventing silencing of the paternally inherited allele of the UBE3A gene and reactivating production of the deficient protein.

On the gene therapy side, progress kept coming—but with the usual reminder that in biotech, nothing is linear.

For DTX401, Ultragenyx’s AAV gene therapy for Glycogen Storage Disease Type Ia (GSDIa), the Phase 3 GlucoGene study hit its primary endpoint. DTX401 led to a statistically significant and clinically meaningful reduction in daily cornstarch intake compared with placebo at Week 48. Ultragenyx said it expected a BLA filing in mid-2025.

But another gene therapy program ran into a different kind of wall: not clinical, but regulatory and operational. The FDA issued a Complete Response Letter for the Biologics License Application for UX111 (ABO-102), an AAV gene therapy for Sanfilippo syndrome type A (MPS IIIA).

“We believe the CMC observations are readily addressable and many have already been addressed. While the CRL will delay the potential approval of UX111 to 2026, we are working with urgency to respond and resubmit.” Ultragenyx said the observations related to facilities and processes, not product quality, and emphasized that the FDA had acknowledged the strength of the neurodevelopmental outcome data and the supportive biomarker package. The CRL did not cite issues with the clinical data package or clinical inspections, and asked that updated clinical data from current patients be included in the resubmission.

Through it all, management kept pointing back to the same endgame: more approved products, more revenue, and eventually a business that can fund its own ambition. “We have created a next-generation rare disease company on a pathway to profitability with meaningful revenue growth from multiple global products and a series of potential new drug approvals,” said Emil D. Kakkis, M.D., Ph.D., chief executive officer and president of Ultragenyx.

XI. The Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand Ultragenyx, you have to stop thinking like a traditional pharma company. In mass-market medicine, you win by moving volume. In ultra-rare disease, volume doesn’t exist. So Ultragenyx built a model engineered for a world where the “market” might be a few dozen families—and where the hardest work isn’t just inventing the drug, but getting it to the right patient, in the right place, with the right support, every time.

Start with pricing, because that’s the part everyone reacts to first. Ultragenyx said it intended to price Mepsevii at about $375,000 per year. That number can sound shocking in isolation. But in ultra-rare disease, the total revenue pool is capped by biology. A therapy for 100 patients priced around $400,000 a year brings in roughly $40 million annually. Out of that has to come manufacturing, post-approval monitoring, medical affairs, patient support, and, critically, the sunk cost of development—which can run $100 million to $200 million even when the trials are small. The uncomfortable truth is that if pricing doesn’t reflect that reality, the drug often doesn’t get built at all.

Then there’s the second revenue stream that made the model investable: Priority Review Vouchers. When Mepsevii earned a voucher, Ultragenyx sold it and recorded a $130 million gain—non-dilutive capital that could be recycled straight back into the pipeline. And the dynamic repeated: Ultragenyx also recorded a $40.3 million gain from its portion of the sales of the PRV received with the Crysvita approval. In a business where each individual product might be constrained by tiny patient numbers, PRVs created a separate economic “hit” that helped fund the next set of shots on goal.

Commercially, Ultragenyx doesn’t operate like a typical pharma company either. The distribution model is built around centers of excellence, not broad sales coverage. When the relevant clinics worldwide number in the dozens, the winning move isn’t deploying an army of reps. It’s building deep, durable relationships with the handful of specialist centers that actually treat the disease—then surrounding them with medical affairs teams who understand the biology and can support real-world use.

That same logic applies to patient services, which in this world aren’t a nice-to-have—they’re core product infrastructure. As the company put it: “Through the UltraCare™ program, our next job is helping everyone who can benefit from Crysvita to navigate the health-care system and gain access to this new treatment.” For therapies that can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, access is a process: insurance authorization, infusion logistics, appeals, financial support, and constant coordination. If you can’t run that machine well, your “approved drug” stays theoretical.

The portfolio matters, too. One of the reasons Ultragenyx built a platform instead of a single-asset company is that diversification is risk management in biotech. In 2024, Crysvita brought in $410 million, up 25% year over year. Dojolvi generated $88 million, also up 25%. Evkeeza added $32 million as demand continued to build in Ultragenyx’s territories outside the United States. None of these products alone defines the company. Together, they create something rarer in biotech: an operating base that can keep funding ambition.

Over time, the regulatory and operational muscle itself has become a competitive advantage. Years of negotiating novel endpoints, trial designs, and approval pathways with the FDA and EMA create institutional knowledge that’s hard to copy quickly—especially when each new disease comes with its own quirks and constraints.

And then there’s manufacturing—the quiet constraint behind every rare disease company. Making biologics in small batches, reliably and economically, forces a different set of decisions around quality systems, production planning, and supply chain resilience. Ultragenyx built a hybrid approach, combining internal capabilities with strategic CDMO relationships, designed for flexibility and repeatability rather than pure scale.

Financially, the model is still in its build-out phase, and the income statement shows it. Total operating expenses for the year ended December 31, 2024 were $1,096 million, including $158 million of non-cash stock-based compensation. For 2024, Ultragenyx reported a net loss of $569 million, or $6.29 per share basic and diluted, compared with a net loss of $607 million, or $8.25 per share, in the prior year.

But the direction of travel is the point. The company said its path to profitability was strengthening through revenue growth and expense management, with decreasing cash burn expected in 2025. In other words: the platform is built. Now the question is whether the pipeline can turn that platform into an engine that eventually funds itself.

XII. Competitive Landscape & Industry Context

Ultragenyx doesn’t operate in a huge market, but it does operate in a crowded one. Rare disease biopharma is a small world where competitors often look like collaborators one year and rivals the next—especially as the science shifts from chronic treatments to one-time interventions.

The most obvious comparison is BioMarin—appropriately so, given how much of Ultragenyx’s early DNA came from there. BioMarin helped define modern rare disease biotech: enzyme replacement therapies for MPS disorders, the regulatory playbook for tiny populations, and the commercial muscle to serve patients spread across the globe. It still operates at a much larger scale, with multiple approved products and a wider footprint, and it remains the “big brother” reference point for what a rare disease specialist can become.

Then there’s Alexion, now inside AstraZeneca after a $39 billion acquisition. Alexion proved the ceiling of the model—Soliris became one of the highest-revenue rare disease drugs ever—but also the downside of success in this category: pricing scrutiny that can follow a company for years. In rare disease, you don’t just have to win clinically. You have to be prepared to defend the entire economic logic of what you’re doing.

Sarepta is a different kind of peer: a company built around neuromuscular disease, with Duchenne muscular dystrophy at the center and gene therapy as a major bet. That focus overlaps with Ultragenyx’s ambitions in next-generation modalities, and it’s a reminder that as more companies move into gene therapy, “rare disease” stops being a niche and starts being a battlefield.

Vertex is the other lesson, even if it plays in a different corner of the map. Cystic fibrosis is rare, but not ultra-rare—and Vertex’s rise shows what happens when a company combines deep scientific focus with relentless clinical execution and then turns that into an extraordinarily profitable commercial engine. It’s a different scale of opportunity than most of Ultragenyx’s indications, but it’s still a model that shapes investor expectations for what “rare disease success” can look like.

Over the last decade, Big Pharma has moved from skeptical to hungry. The Alexion deal, ongoing speculation around rare-disease-focused companies, and Pfizer’s purchase of Global Blood Therapeutics all point to the same trend: large pharmaceutical companies want durable, defensible assets in specialized markets. For Ultragenyx, that’s a double-edged sword. More buyers can mean more partnering opportunities and higher valuations for good assets. But it also means more well-capitalized competitors willing to pay up for pipeline programs and talent.

Ultragenyx also faces a long list of direct and indirect competitors—Sarepta Therapeutics, Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, Sangamo Therapeutics, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, and Cytokinetics among them—along with many others across the rare disease landscape.

What Ultragenyx hangs its differentiation on is breadth. Most companies in the space are built around a single tool: gene therapy, antisense oligonucleotides, enzyme replacement, RNAi. Ultragenyx is built around the opposite idea: start with the disease, then use whatever modality fits the biology. That modality-agnostic stance is not just scientific philosophy—it’s a strategic hedge against any one approach falling out of favor, running into safety issues, or getting leapfrogged by new technology.

And new technology is exactly where the pressure is building. The gene therapy wave created enormous opportunity, but it also introduced a real threat to the traditional rare disease economics. A one-time potentially curative treatment can be a miracle for patients, but it can also compress what would have been years of recurring therapy revenue into a single upfront payment—forcing companies, payers, and regulators to renegotiate the business model in real time. Bluebird Bio and Spark Therapeutics helped pioneer the commercial path here, and the industry has been learning from both the wins and the hard parts ever since.

Beyond gene therapy is gene editing. CRISPR-first companies like Intellia Therapeutics and CRISPR Therapeutics represent a new class of competitor: not just improving the existing model, but threatening to replace it with something more permanent. Over time, the question won’t just be “who can commercialize ultra-rare drugs?” It will be “who can deliver durable cures safely—and get them paid for?”

Finally, there’s a force that doesn’t show up in most competitive matrices: patient advocacy groups. In rare disease, these communities can function like regulators, recruiters, and distribution channels all at once. Their trust can determine whether a trial enrolls, whether families stick with a protocol, whether physicians hear about a therapy early, and how a launch feels on the ground. Ultragenyx’s long-term relationships with patient communities aren’t a marketing asset—they’re a compounding advantage that takes years to build and can’t be bought quickly.

XIII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

Ultragenyx helped prove that “ultra-rare” can still be a real business. And once you prove that, you attract company. New entrants show up because the prize is attractive: orphan pricing power, regulatory tailwinds, and patient populations where a focused commercial team can actually cover the world.

But the barriers are real. It’s not just about having a good molecule. It’s knowing how to run trials with tiny populations, how to build trust with patient groups, how to work with regulators when the normal playbook doesn’t apply, and how to manufacture reliably when you’re making very small batches.

At the same time, the science is getting easier to start and harder to win with. Gene editing and AI-enabled drug discovery are lowering some R&D barriers, which means more shots on goal from newer players. And there’s a paradox baked into the category: the “best” rare diseases—larger populations, clearer biology, cleaner endpoints—pull in the most competitors, while the truly ultra-rare conditions remain economically difficult even with orphan incentives.

One more wildcard sits outside the lab: policy. If Congress changes the Priority Review Voucher program or other orphan incentives, it shifts the ROI for new entrants and incumbents alike.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

Ultragenyx relies on specialized suppliers in two places that matter: making the drug and sourcing the science. On the manufacturing side, it uses contract development and manufacturing organizations (CDMOs) for certain capabilities, even as it has invested in building more in-house capacity to reduce dependence. On the pipeline side, academic institutions remain a key source of early-stage assets.

The leverage sits with suppliers when the work is highly specialized and the alternatives are limited—especially in gene therapy manufacturing, where only a small number of CDMOs have the right capabilities and capacity. That can create bottlenecks and timeline risk even when the underlying science is working.

There’s also industry-level uncertainty that can ripple into supply chains. The HeLa cell line litigation is one example of how disputes around foundational biological inputs can add complexity to manufacturing and development planning.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE

Rare disease pricing creates headlines, but payor behavior is often shaped by something more mundane: budget impact. When a therapy treats dozens of patients, many insurers don’t mount the same kind of resistance they might for a broadly prescribed drug—because the total cost is small relative to the size of their book of business.

That said, scrutiny is rising, especially from government payors. Medicare in the U.S. and national health systems in Europe have increasingly pushed on ultra-high-priced therapies. And for some conditions, even “rare” adds up across regions—homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia affects roughly 1,600 people in the European Union, for example—enough to make reimbursement debates more visible and more political.

There’s also an uncomfortable dynamic in the background: patient desperation. Families facing progressive, devastating diseases will fight for access, regardless of price. That creates pricing power, but it also creates ethical pressure and reputational risk for any company operating in the space.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW-MODERATE

Orphan diseases get orphan designation for a reason: in most cases, there simply aren’t alternatives. That limits substitution pressure for many of Ultragenyx’s approved products.

The long-term substitute threat comes from technology, not competitors with me-too drugs. Gene therapy and gene editing carry the promise of one-time, potentially curative treatments that could replace chronic therapies like enzyme replacement. If a one-time gene therapy costs a few million dollars, it can still look “cheap” compared with decades of an annual therapy priced in the hundreds of thousands. That’s a scientific threat, a commercial threat, and—if it works—a profound shift in what the market wants.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE

In most of Ultragenyx’s indications, rivalry is concentrated rather than crowded: usually one or two serious programs per disease, not ten. But the competition can be ruthless because first-mover advantage is unusually strong. In ultra-rare diseases, the clinical trial itself can consume the available patient population. Once patients are enrolled—or once an approved therapy exists—running a competing trial becomes exponentially harder.

At the same time, rare disease is one of the few corners of biopharma where cooperation is often a necessity. Patient advocacy groups, academic researchers, and sometimes even competing companies may work together on natural history studies and disease understanding, because no single player can map the biology alone when the total patient count is so small.

XIV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Power #1: Cornered Resource - STRONG

Ultragenyx has accumulated assets you can’t just buy off the shelf. Years of rare disease experience become a kind of pattern recognition—how to find patients, how to design trials around tiny populations, how to keep programs moving when the “standard” playbook breaks. Natural history data and patient registries are especially hard to replicate, because they take time, trust, and sustained presence in the community. Stack on top of that the muscle memory of navigating regulators through multiple approvals, plus long-running relationships with patient foundations and advocacy leaders, and you get something close to a cornered resource in a world where access is everything.

Power #2: Scale Economics - MODERATE

Ultra-rare disease doesn’t offer classic scale. You can’t lower unit costs by selling to millions of patients, because those patients don’t exist. But Ultragenyx does get a different kind of scale benefit: repetition. Each program makes the next one a little more efficient—regulatory filings, trial ops, manufacturing planning, and the internal machinery needed to run small, global studies. Manufacturing learning curves matter too, even at small volumes. And the platform creates economies of scope: not scale within one disease, but leverage across many.

Power #3: Network Economics - WEAK-MODERATE

There are real, but limited, network effects in rare disease. Registries get more valuable as more patients join, because each new datapoint improves the picture of the disease and speeds clinical development. Centers of excellence develop their own gravity as they treat more patients and gain experience, which can further concentrate referrals and expertise. Still, this isn’t social media—traditional network effects remain muted in pharma.

Power #4: Switching Costs - STRONG

In this category, switching costs aren’t about brand loyalty. They’re about medical risk and logistical friction. Once a patient is stabilized on a therapy, stopping or switching can be dangerous, especially in progressive diseases. And even if there’s a clinical reason to change, the paperwork can be punishing: insurance authorizations, specialty pharmacy coordination, infusion scheduling, appeals. Meanwhile, the relationships that form between families, specialist physicians, and treatment centers tend to compound over time. When therapies show durability—like the longest treated responders demonstrating benefit out to about four years after dosing—that stickiness only increases.

Power #5: Branding - MODERATE-STRONG

In rare disease, the brand is trust. Families making life-altering decisions want to believe the company understands the disease, will show up for the community, and will support them through the hardest parts of access and care. Ultragenyx’s identity as a rare disease specialist carries weight with both physicians and patients. At the same time, every new therapy still requires building credibility one indication at a time—because in this world, reputation is earned locally and personally.

Power #6: Counter-Positioning - STRONG (historically)

Ultragenyx was built on classic counter-positioning: big pharma couldn’t make the economics work in ultra-rare diseases, so it didn’t try. That left room for a company willing to build a dedicated machine for tiny markets. The platform thesis also pushed against the single-asset biotech norm of the era.

The catch is that this advantage fades once everyone realizes the niche is profitable. Big pharma is now much more aggressive in rare disease, and new “platform” companies are everywhere. Ultragenyx still benefits from being early, but it no longer has the field to itself.

Power #7: Process Power - STRONG

This is the moat. Designing clinical trials when there may be only dozens of eligible patients worldwide is a learned craft. Regulatory navigation in ultra-rare disease is packed with tacit knowledge—what endpoints will fly, how to build convincing natural history comparisons, how to structure data packages that answer the real questions reviewers will ask. Commercial execution is also its own discipline: center-of-excellence strategy, deep medical affairs, and patient services that function like mission-critical infrastructure. Patient finding and enrollment, especially, depend on relationships and credibility that take years to build and can’t be replicated quickly.

Overall Assessment: Ultragenyx’s strongest, most durable advantages sit in process power, cornered resources, and switching costs. Scale economics are inherently capped by ultra-rare markets, so the company wins by getting better at doing many small things repeatedly. The threat is that well-capitalized entrants—especially those bringing gene editing and other potentially superior technologies—could leapfrog parts of the model if Ultragenyx doesn’t keep evolving.

XV. The Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case:

Clinical risk never goes away. Setrusumab (UX143) not stopping early, and the UX111 Complete Response Letter, are reminders that even well-designed, high-conviction programs can run into friction late—either in the data or in execution. And because Ultragenyx isn’t a mega-cap, every pipeline wobble tends to show up quickly in the stock.

Gene therapy remains under a microscope. The entire field has had to reckon with serious adverse events, and regulators have responded with heightened scrutiny. For Ultragenyx, the UX111 CRL—driven by CMC observations—underscored a frustrating reality: you can have strong clinical and biomarker data and still get held up by manufacturing and process requirements.

The Priority Review Voucher tailwind isn’t permanent. A meaningful part of rare pediatric disease economics has been the ability to earn and monetize PRVs, but that value exists only as long as Congress keeps the program intact. Any modification or elimination would change the financing math for future pediatric programs.

Pricing pressure keeps building, especially outside the U.S. Ultra-rare therapies can be extraordinarily expensive on a per-patient basis, and government payors are increasingly willing to challenge whether that spending is justified. Reimbursement isn’t just a negotiation—it’s a political question, and politics can shift.

Operational complexity is its own risk. Ultragenyx is juggling multiple products, across multiple modalities, produced in specialized small batches. That’s a hard manufacturing and supply chain problem even for much larger companies—and when anything breaks, patients feel it immediately.

The revenue mix is concentrated. In 2024, Crysvita generated $410 million—about 73% of total revenue. That concentration creates real exposure, including reliance on Kyowa Kirin for commercial supply and the transition back to Kyowa Kirin of exclusive rights to promote Crysvita in the U.S. and Canada. When one product is that central, any disruption matters.

And the company is still losing money. For the year ended December 31, 2024, Ultragenyx reported a net loss of $569 million. That means continued dependence on capital markets and financing flexibility—things that can disappear quickly in the wrong macro environment.

The Bull Case:

The platform is no longer theoretical. Ultragenyx has four approved therapies, multiple late-stage shots on goal, and a proven ability to turn approvals into real-world access and revenue. The stretch from 2017 through 2020 mattered because it didn’t just validate the science—it validated the company’s ability to operate like a commercial rare disease specialist.

Each new product expands the portfolio without obvious cannibalization. That’s one of the underappreciated perks of rare disease: you can add meaningful incremental revenue program by program, and diversification comes naturally because the indications don’t overlap much.

Operational leverage is starting to show. For 2025, the company guided to $640 million to $670 million in revenue. If revenue continues to grow faster than expenses, the path toward profitability becomes less of a narrative and more of a timeline.

GTX-102 is the kind of asset that can change the company’s scale. Angelman syndrome is estimated to affect about 60,000 people in commercially accessible geographies. If the Phase 3 program succeeds, it has the potential to reshape Ultragenyx’s growth trajectory in a way that few ultra-rare drugs ever can.

The moat is mostly human and procedural—and that’s why it’s hard to copy. Years of patient relationships, repeated regulatory reps, and operational muscle memory in tiny populations are advantages that don’t transfer cleanly on a balance sheet, but they compound over time.

There’s also strategic optionality. If Ultragenyx keeps building, it could become an acquirer and consolidate assets in rare disease. Or it could be acquired at a premium, given the combination of an established commercial base and a pipeline with multiple near-term catalysts.

Regulatory dynamics still favor specialists. Expedited pathways, orphan designations, and collaborative approaches from the FDA and EMA continue to support rare disease development—especially for companies that have demonstrated they can execute responsibly.

And international expansion still has runway. Ultragenyx said product sales from Latin America and Turkey grew 78% compared to the prior year. In rare disease, “global” isn’t a buzzword—it’s how you find enough patients for both trials and sustainable commercial scale.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Investors tracking Ultragenyx should keep it simple and focus on the signals that actually move the story:

-

Revenue growth rate: Sustained year-over-year growth is the cleanest proof that the commercial engine is working. The company’s guidance implies continued double-digit growth.

-

Pipeline milestone delivery: Watch the timing and outcomes for GTX-102, UX143, DTX401, and the UX111 resubmission path. In biotech, calendars and readouts are strategy.

-

Cash burn trajectory: Net cash used in operations relative to revenue is the tell. If burn declines while the company keeps advancing the pipeline, that’s the inflection investors have been underwriting for years.

XVI. Lessons for Founders, Investors & Society

For Founders:

Platform thinking can work even in a hit-driven industry. Ultragenyx didn’t bet the company on a single molecule and a single readout. It built a multi-asset, multi-modality machine, and used diversification as a feature, not a concession.

Regulatory innovation can be a real competitive advantage. In rare disease, knowing the rules is table stakes. Helping shape how the rules evolve—through deep engagement with regulators and policy—can become a moat competitors can’t replicate quickly.

Small markets can be great markets if the economics are engineered correctly. A tiny patient population doesn’t automatically mean “bad business.” It means the unit economics, access strategy, and operational execution have to be designed for that reality from day one.

Operational excellence matters as much as the science. Clinical trials with tiny populations, specialized manufacturing, global logistics, and reimbursement navigation aren’t supporting functions in rare disease. They’re core product. The companies that win are the ones that execute relentlessly.

Mission and profit don’t have to be at odds. Ultragenyx is a case study in the idea that serving patients the market historically ignored can still create a durable, valuable business—if you can actually deliver.

Partnership strategy is a craft. Knowing when to build internally, when to in-license, and when to partner—like the Kyowa Kirin collaboration on Crysvita—requires discipline and judgment. Get it right, and you can move faster than you could alone. Get it wrong, and you can give away the economics or the control you’ll need later.

For Investors:

You can’t underwrite a platform biotech like a single-asset biotech. The usual probability-weighted “one drug, one market” model misses the point. The right lens is portfolio-level: multiple shots on goal, shared infrastructure, and compounding execution advantages.

Regulatory incentives can be real value, not footnotes. Programs like Priority Review Vouchers can materially change the payoff profile of pediatric rare disease programs. Understanding those incentives—and how management plans to capture them—can be analytical edge.

Diversification reduces binary risk, but it doesn’t eliminate it. Platform companies still swing around major readouts and regulatory outcomes. The difference is that a miss hurts, but it doesn’t have to be fatal.

“Productive efficiency” is a strategy, not a slogan. When a company gets meaningfully better at running tiny trials, building natural history data, and launching into centers of excellence, that repeatability becomes a durable advantage.

When TAM is misleading, unit economics and competitive dynamics matter more. A small market with high willingness to pay, low competition, and strong switching costs can be more attractive than a large market that’s crowded and price-sensitive.

Management quality is everything in execution-dependent businesses. Kakkis was at BioMarin in San Rafael before founding Ultragenyx in 2010, and the company has grown to more than 1,100 employees worldwide. In rare disease biotech, the track record of building, approving, manufacturing, and commercializing matters as much as the pipeline slide.

For Society:

Incentives work—at least when they’re designed well. The Orphan Drug Act and the PRV program helped make previously unfundable diseases investable. Policymakers looking for ways to spur innovation in neglected areas should study what worked here.

The pricing question doesn’t go away. Society is still wrestling with what “fair” looks like when a therapy costs hundreds of thousands of dollars per year for a small number of patients. The tension between affordability and innovation is real, and there’s no clean resolution.

Patient advocacy groups have become essential infrastructure. In rare disease, these organizations aren’t just support networks. They help drive diagnosis, shape trial endpoints, enable recruitment, and influence regulatory thinking in ways traditional pharma models historically underestimated.

Rare disease development is the on-ramp to ultra-personalized medicine. The playbooks built here—small populations, novel endpoints, bespoke manufacturing—are the same muscles medicine will need as it moves toward ever more individualized treatments.

And the hard problems are still ahead. As some of the “easier” rare diseases get addressed—clear biology, straightforward replacement strategies—the frontier shifts to conditions that are more complex, especially in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disease. The work gets harder, not easier.

XVII. The Road Ahead & Future Scenarios

Near-term (2025-2027):

This window is about readouts. Not narratives. And Ultragenyx has a few that can swing the story in very different directions.

The biggest is GTX-102. Ultragenyx expects the Phase 3 Aspire study to complete in the second half of 2026, and says it intends to move quickly to deliver topline data and advance toward a regulatory submission. If Aspire works, it doesn’t just add another product. It changes the company’s scale.

UX143 is the other near-term hinge. The Orbit study is still tracking toward its final analysis on the original plan, around the end of the year. Those data will decide whether setrusumab becomes the next approved therapy—or another reminder that even “Breakthrough” programs still have to pass the final exam.

Then there’s UX111. The timeline here is less about clinical uncertainty and more about execution: addressing the FDA’s CMC observations, resubmitting the BLA, and then getting through what Ultragenyx expects could be up to a six-month review after resubmission. It’s the kind of work that doesn’t make for exciting biotech headlines, but often determines whether a medicine reaches patients.

Commercially, the company needs the base business to keep doing its job. For 2025, Ultragenyx guided to total revenue of $640 million to $670 million. Hitting that range would reinforce the idea that the portfolio can keep compounding even while the pipeline absorbs investment.

Medium-term (2027-2030):

If GTX-102 succeeds, the launch could reshape Ultragenyx’s revenue mix and growth rate. Angelman syndrome’s addressable population—about 60,000 people in commercially accessible geographies—would put Ultragenyx in a different category than its smallest ultra-rare launches, where “success” might mean serving dozens or hundreds of patients.

Gene therapy could also become a second growth pillar. Approvals for DTX401, and potentially UX111 after resubmission, would validate the gene therapy push and add new vectors beyond the company’s existing chronic-treatment franchises.

Geographic expansion should keep filling in the map—deepening presence in major markets while continuing to penetrate emerging regions where diagnosis, reimbursement, and infrastructure are often the real constraints.

And dealmaking pressure likely increases. Ultragenyx could become a compelling acquisition target for larger pharma looking for a rare disease platform. Or it could keep playing the other side of the board, acquiring and consolidating smaller rare disease assets to feed its engine.

Long-term questions:

Can Ultragenyx stay independent, or does the gravitational pull of consolidation eventually win? Rare disease has been one of the most acquisitive corners of biopharma, and Ultragenyx is exactly the kind of platform a larger player might want to buy rather than build.

Does the company keep moving “upmarket,” from ultra-rare into “just rare”? GTX-102’s target population suggests it’s already testing that boundary.

What happens as AI-enabled drug discovery speeds up target identification and optimization? That could lower the time-to-competition for everyone—raising the bar for differentiation, while also giving Ultragenyx new tools to accelerate its own pipeline.

Newborn screening is another potential reshaper. Earlier diagnosis changes everything: who gets treated, when they get treated, and what kind of therapy makes sense. It can tilt the field toward early intervention strategies, including gene therapies, rather than waiting for disease progression and managing it for life.

And then there’s the unavoidable strategic tension: one-time cures versus chronic treatments. Gene therapies that replace recurring dosing can be transformative for patients, but they also force companies to rethink revenue timing, payer dynamics, and long-term portfolio design.

Wild cards: changes to orphan drug incentives, scientific breakthroughs that push medicine toward ever more personalized therapies, and economic shocks that tighten capital markets—especially for companies still operating at a net loss.

XVIII. Epilogue & Reflections

Emil Kakkis’s path from academic pediatrician to founder and CEO of a multi-billion-dollar rare disease company took more than three decades—and it came with recognition from across the industry. Over the years, Dr. Kakkis received the Life Science Leadership Pantheon award from California Life Sciences, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National MPS Society, the Roscoe O. Brady Award for Innovation and Accomplishment from the WORLDSymposium, and BIO’s Henri Termeer Visionary Leadership award for his work in rare diseases.

What’s most surprising about the Ultragenyx story is that it worked at all.

In 2010, the founding thesis sounded like a dare: build a profitable drug company by treating diseases so rare that the total patient count might fit inside a school auditorium. The economics looked broken. The clinical trials looked borderline impossible. And yet, four therapies went on to generate more than $500 million in annual revenue, with multiple additional approvals anticipated. That didn’t happen because Ultragenyx got lucky once. It happened because the company paired scientific insight with regulatory creativity and, just as importantly, the operational discipline to do the unglamorous work repeatedly.

The human stories are the emotional core that no balance sheet can capture. When Mepsevii moved forward for MPS VII, it carried decades of scientific persistence behind it. “I am thrilled beyond belief to see this treatment advance after more than 40 years of work and anticipation. Thanks to Ultragenyx for making it happen,” said William S. Sly, Chairman Emeritus, Department of Biochemistry at St. Louis University. “I hope that this treatment will follow the other successful examples of enzyme therapy for LSDs and help improve the lives of patients with this rare disease.”

Zoom out, and Ultragenyx starts to rhyme with a few companies in the Acquired canon. Like LVMH, it’s a platform—multiple distinct “houses,” unified by a management system built to run them. Like NVIDIA, it invested early in enabling infrastructure—rare disease development capabilities—before the full set of applications was obvious. And like Berkshire Hathaway, its long-term outcome depends on capital allocation across a portfolio of opportunities, not just the fate of any single bet.

Ultragenyx also changed the rare disease industry by proving that platform thinking could win in a world long dominated by single-asset gambles. Its work on novel trial designs, endpoint selection, and regulatory navigation didn’t just advance its own pipeline; it helped establish precedents that others could follow.

That’s what makes the story so rare in the first place: the alignment. Ultragenyx created shareholder value by serving patients that conventional pharmaceutical economics would have left behind. In doing so, it reinforced the idea that incentives—like orphan drug frameworks and Priority Review Vouchers—can channel market forces toward social good, without pretending the science is easy or the risks are small.

Why the company matters extends beyond its market capitalization. It’s proof that ultra-rare patients don’t have to be invisible, that rigorous drug development can be built for the smallest populations, and that commercial viability and medical mission can coexist—if you’re willing to engineer the company around that reality.

The story, of course, isn’t finished. GTX-102 results, gene therapy approvals, the path to profitability, and the question of independence versus acquisition will shape Ultragenyx’s ultimate legacy. But whatever comes next, the first fifteen years established something remarkable: a company that took the seemingly impossible economics of ultra-rare disease and turned it into a growing enterprise for patients who had no alternatives.

XIX. Further Reading & Resources

Essential Long-Form Articles & Papers:

-

Ultragenyx SEC Filings—10-Ks and investor presentations (2014-present). If you want the clearest, most complete public record of how the strategy evolved—and what it cost and returned over time—start here.

-

FDA Rare Pediatric Disease PRV Program Documentation. The Priority Review Voucher program isn’t just policy trivia in this story; it’s one of the economic levers that made parts of the model work.

-

Clinical trial publications for Mepsevii, Crysvita, Dojolvi, and Evkeeza. These are the scientific receipts behind the approvals—what was measured, what changed, and how the data were framed for ultra-rare populations.

-

EvaluatePharma Orphan Drug Reports. Helpful industry-level context on orphan drug markets, competitive dynamics, and how rare disease portfolios get valued.

-

Patient Advocacy Foundation Publications. A grounding counterweight to the investor narrative—how families experience access, care coordination, and the real-world impact of new therapies.

Company Resources:

- Ultragenyx Investor Relations website (ir.ultragenyx.com) for earnings calls, presentations, and SEC filings