PTC Therapeutics: The Science of Rare Disease Drug Development

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

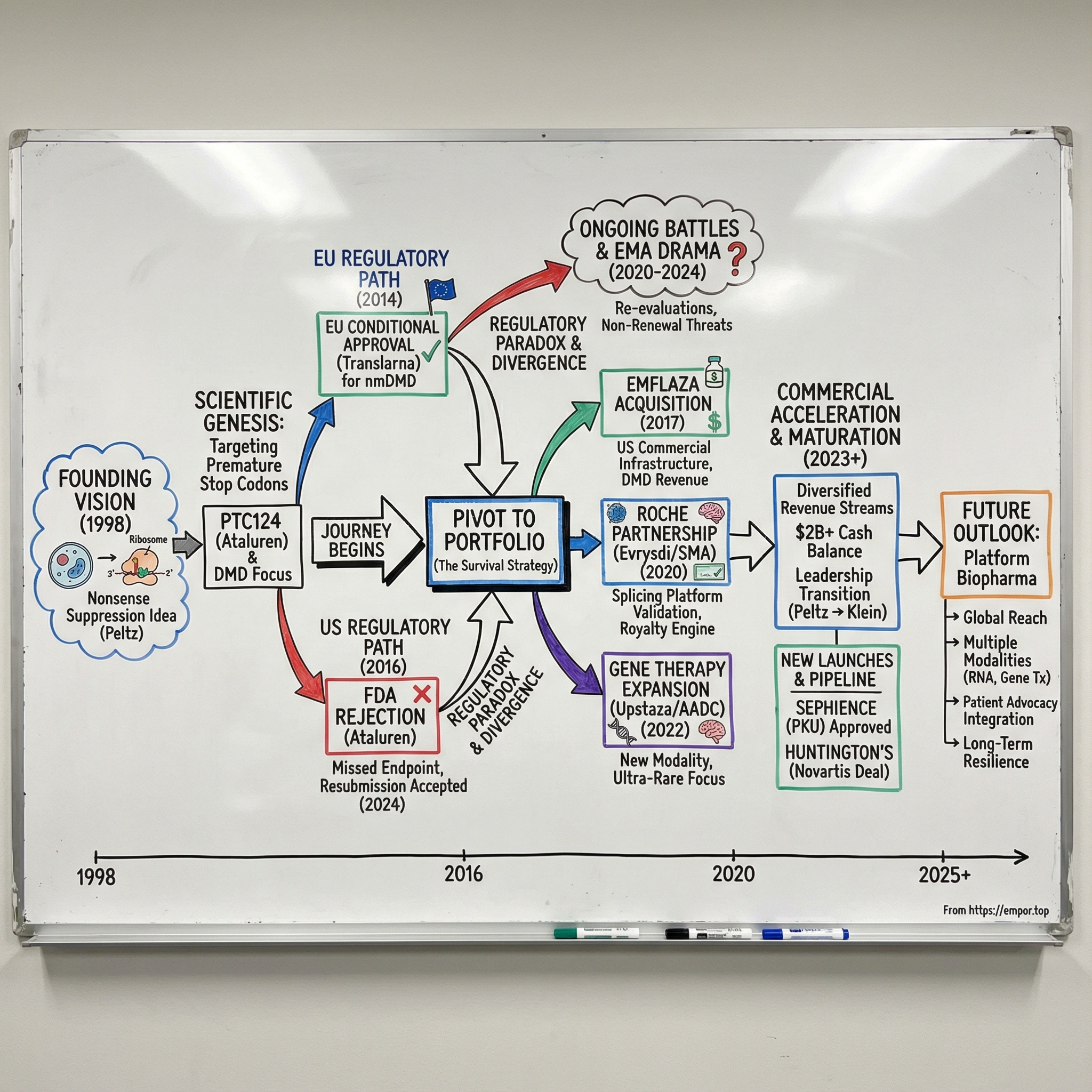

Picture a small lab in South Plainfield, New Jersey, in the late 1990s. A molecular biologist named Stuart Peltz is staring at a ribosome diagram on a whiteboard, turning over an idea that sounds almost like science fiction.

What if you could coax the cell’s protein-making machinery into ignoring bad genetic instructions? What if a small molecule could persuade ribosomes to read through a premature stop signal—a mutation that cuts a gene off mid-sentence—and keep going long enough to make a functional protein?

That question didn’t just launch a research program. It consumed the next quarter-century of Peltz’s life, grew into a publicly traded company with more than a billion dollars in annual revenue, and sparked regulatory fights that, at times, put desperate families and cautious scientists on a collision course across two continents.

Peltz founded PTC Therapeutics, Inc. in 1998 and has served as Chief Executive Officer and a member of the board of directors since the company’s inception. Under his leadership, PTC evolved from a research organization built on deep expertise in RNA processes and control into a NASDAQ-listed biopharmaceutical company focused on discovering, developing, and commercializing orally administered small-molecule treatments for genetic disorders.

The central question in PTC’s story is this: How did a small company built around a single, unproven scientific mechanism become a global rare disease powerhouse—and survive multiple near-death experiences along the way?

The themes are big, and they’re not always comfortable. Scientific vision versus commercial reality. The gulf between European and American regulatory philosophy. The economics of ultra-rare diseases, where patient populations are tiny but the stakes are enormous. And most of all, the human cost of drug development—the years that slide by while trials crawl forward and children’s diseases keep progressing.

Today, PTC Therapeutics, Inc. is a science-driven, global biopharmaceutical company focused on the discovery, development, and commercialization of clinically differentiated medicines for people living with rare disorders. Its ability to commercialize products globally has become the engine that funds a robust and diversified pipeline of transformative medicines.

What makes this story so gripping is how many times the company had to reinvent itself, how often the data refused to behave, and how frequently regulators forced PTC to defend not just a drug, but an entire worldview. By the end, we won’t just understand what PTC built—we’ll understand why building a rare disease company might be one of the hardest, most consequential games in all of biotech.

II. Founding Vision & Scientific Genesis (1998-2005)

Before Stuart Peltz ever had to think about quarterly earnings or FDA briefing documents, he lived in the world of academic science: publishing, training students, and trying to answer the kinds of questions that don’t come with neat deadlines.

Prior to founding PTC, Peltz was a Professor in the Department of Molecular Genetics & Microbiology at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School at Rutgers University. He built a reputation as a scientific leader in RNA biology, focused on post-transcriptional control—how cells decide what gets translated into protein, when, and how much. Over more than 30 years of research and more than 100 publications, his work helped clarify how RNA biology events like mRNA turnover and translation interact to ultimately control protein production in the cell.

That background matters, because PTC wasn’t born from a single “drug idea.” It was born from a mechanism—one that, if it worked, could reach across a whole category of genetic disease.

The core insight was simple to explain and brutal in its implications. In many genetic disorders, the problem isn’t that a gene is missing. It’s that a mutation introduces what biologists call a premature termination codon—a nonsense mutation. Imagine you’re reading a sentence and, halfway through, there’s a period that shouldn’t be there. The ribosome hits that false stop sign, translation ends early, and the cell spits out a truncated protein that can’t do its job.

On average, about 11% of monogenic disorders are caused by nonsense mutations. So if you could reliably persuade ribosomes to ignore those premature stop signs—to “read through” the nonsense codon and finish the sentence—you wouldn’t just be treating one disease. You’d be attacking a root cause shared by thousands.

That’s the promise of nonsense suppression therapy: suppressing translation termination at in-frame premature termination codons to restore deficient protein function. PTC’s lead compound from this approach, PTC124—also known as ataluren—is an oxadiazole discovered by PTC Therapeutics that suppresses termination at premature stop codons in mammalian cells without affecting translation termination at natural stop codons. Preclinical studies suggested PTC124 was safe, had minimal off-target side effects, had no antibacterial activity, and could be taken orally.

But “in theory” is cheap. The technical challenge was enormous. You needed a molecule selective enough to help only where the gene was broken—without causing ribosomes to barrel through normal stop codons throughout the body. Aminoglycoside antibiotics had shown that readthrough could happen, but their toxicity made them a non-starter for chronic use. PTC’s mission was to find something safer and orally available—something a patient could actually live with.

Ataluren came out of a collaboration with Lee Sweeney’s lab at the University of Pennsylvania, initially funded in part by Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy. The team used phenotypic screening of a chemical library to find compounds that increased protein expression from mutated genes, then optimized one of those hits into ataluren.

From there came a fateful strategic choice: Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

DMD affects roughly 1 in 3,500 to 5,000 male births worldwide. It’s relentless—progressive muscle weakness that often puts boys in wheelchairs around age 12, followed by life-threatening cardiac and respiratory complications in their twenties. And importantly for PTC’s mechanism, around 13% of DMD cases are caused by nonsense mutations. That meant the target population was both scientifically relevant and large enough to support clinical trials—while the unmet need couldn’t have been more urgent.

In the early 2000s, PTC built its platform by screening vast numbers of compounds and, just as importantly, building trust with the rare disease ecosystem. The development of Translarna was supported by grants from Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Inc., the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the FDA’s Office of Orphan Products Development, the National Center for Research Resources, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy.

Those relationships weren’t just a nice-to-have. In rare disease drug development, they can become the difference between a program that stalls and one that survives—financially, operationally, and later, when the stakes turn political.

III. The Ataluren Journey: From Lab to Clinic (2005-2013)

DMD is a disease that forces you to reckon with time. Every week without treatment, muscle fibers are lost. Every month, everyday tasks get harder. For families watching their sons weaken, clinical trials aren’t academic—they’re a race against a clock nobody can pause.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy primarily affects boys and is caused by the absence of functional dystrophin, a protein that helps keep muscle cells intact under stress. Without it, skeletal muscle, the diaphragm, and the heart gradually break down. Many boys lose the ability to walk around age 10, and serious respiratory and cardiac complications often follow in the late teens and twenties.

PTC’s lead compound, first known as PTC124, would become ataluren, later marketed as Translarna. The idea behind ataluren was elegant in concept and maddeningly hard in practice: make the ribosome less likely to stop at a premature stop codon. By encouraging the insertion of near-cognate tRNAs at the site of a nonsense mutation, the hope was that the cell could finish the protein—producing a dystrophin-like result closer to the body’s own, non-mutated version.

Early clinical studies offered just enough hope to keep going. In Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials, ataluren appeared safe and generally well-tolerated, and some patients showed signals that suggested potential benefit. But DMD is one of the toughest diseases to run trials in. The field’s workhorse endpoint was the six-minute walk test: how far can a child walk in six minutes? Simple to describe, brutal to interpret. Kids start at different baselines, progression isn’t linear, placebo effects can be real, and day-to-day motivation matters. When you’re hunting for modest improvements against a degenerative backdrop, the noise can easily drown out the signal.

During this period, PTC made a strategic call that would shape everything that followed: pursue Europe before the U.S. Under Europe’s conditional approval framework, a therapy aimed at a serious unmet need could reach patients earlier, provided the company committed to generating more definitive data afterward. That authorization would allow PTC to market Translarna in the 28 European Union member states, plus European Economic Area members Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway. The tradeoff was explicit: as part of the conditional marketing authorization, PTC was required to complete its confirmatory Phase 3 trial in nonsense mutation DMD, called ACT DMD, and submit additional efficacy and safety results.

It was, in many ways, a bet on regulatory philosophy. The European Medicines Agency had more flexibility to act on “promising benefit” in dire diseases. The FDA’s posture was different: approval required what it viewed as substantial evidence of effectiveness, period.

And then came the capital markets moment. In June 2013, PTC went public on NASDAQ, selling about 9.6 million shares at $15 each for roughly $144 million in gross proceeds. The timing wasn’t accidental—late-stage trials and global regulatory campaigns are expensive, and PTC needed a war chest.

Because by then, the company had already lived the biotech math. As of March 31, 2013, PTC reported an accumulated deficit of $291.9 million. Fifteen years of science had consumed nearly $300 million—before the company had anything resembling meaningful product revenue. In this business, that’s not a punchline. It’s the entry fee.

IV. The FDA Rejection & European Approval Paradox (2013-2014)

2014 became one of the most consequential—and strange—years in PTC’s history. One drug. One core data set. Two regulators. And two completely different answers.

On August 4, 2014, PTC announced that the European Commission had granted conditional marketing authorization for Translarna (ataluren) in the European Union for the treatment of nonsense mutation Duchenne muscular dystrophy (nmDMD) in ambulatory patients aged five years and older.

For families, it felt historic. Translarna became the first treatment approved in a major market that aimed at the underlying genetic cause of DMD, not just the symptoms. PTC framed it as a milestone not only for the company, but for the entire Duchenne community: “The world’s first approved treatment for the underlying cause of DMD marks a very important moment for patients and their families.”

But that approval didn’t arrive as a clean, unanimous victory. Earlier that year, in January 2014, the CHMP adopted a negative opinion. PTC requested a re-examination, and the CHMP reopened the case. The company came back with additional analyses and arguments—essentially making the case that in a disease this devastating, “suggestive” evidence could still matter. This time, Europe said yes.

And Europe’s yes came with an asterisk. Even at approval, there was uncertainty about Translarna’s effectiveness. The conditional authorization was granted in view of the lack of available treatments, with a requirement that PTC run additional studies to confirm the medicine’s benefits.

Across the Atlantic, the FDA looked at the same situation and saw something else entirely. In February 2016, the FDA declined to accept PTC’s new drug application for ataluren, which was based on a clinical trial that missed its primary endpoint. PTC appealed, and in October 2016 the FDA declined again.

That divergence created an extraordinary reality: European boys could get Translarna. American boys couldn’t. For U.S. families, it was agonizing to watch access hinge not on biology, but on how regulators weighed uncertainty.

For PTC, it was a commercial and strategic tightrope. The company now had to behave like a commercial organization in Europe—launching a drug, supporting patients, building infrastructure—while simultaneously funding expensive trials to satisfy Europe’s conditional requirements and generate the level of evidence the FDA wanted. European revenue helped, but it couldn’t carry the entire company forever.

This paradox became a forcing function for what PTC did next. The company learned, painfully, that approval was never just about the science. It was about interpretation, philosophy, and risk tolerance—and survival would require building a broader business that didn’t depend on a single, contested regulatory outcome.

V. Building the Rare Disease Portfolio (2014-2018)

By the mid-2010s, PTC’s leadership had absorbed a hard lesson from the Translarna experience: a company built around one drug can be wiped out by one regulatory decision. If PTC wanted to survive—and keep funding the long, uncertain march of rare disease trials—it had to become a portfolio company. A rare disease company, not a Translarna company.

That pivot didn’t happen in a vacuum. It happened in the shadow of controversy, and it started with a very different kind of Duchenne drug: a steroid.

In 2017, Marathon Pharmaceuticals won FDA approval for deflazacort, branded as Emflaza, for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Then came the backlash. Marathon’s planned list price—$89,000 per year—collided with a brutal optics problem: the same drug had been available in Canada for roughly $1,000 per year. The outrage was immediate, and it created an opening.

PTC stepped in and acquired Emflaza and related assets from Marathon for $140 million. The deal included upfront consideration made up of cash and PTC common stock, plus the possibility of additional contingent payments based on net sales and a single milestone payment.

For PTC, Emflaza was more than just a product—it was leverage. Emflaza was approved in the U.S. for DMD patients five years and older, regardless of genetic mutation. That meant real American revenue at a moment when Translarna still couldn’t cross the FDA’s threshold. It also meant something just as valuable: the chance to build the machinery of commercialization in the U.S.—sales execution, reimbursement expertise, patient support programs—the infrastructure you can’t improvise once you finally have a drug to sell.

And while Emflaza brought PTC deeper into Duchenne, another program was already pulling the company into a second major disease area—and into a partnership that would eventually reshape its financial trajectory.

The SMA program began back in 2006, initiated by PTC in partnership with the SMA Foundation. In November 2011, Roche gained an exclusive worldwide license to the PTC/SMA Foundation SMN2 alternative splicing program.

Spinal muscular atrophy didn’t rely on “readthrough.” It was a different RNA problem—and a different RNA solution. The goal was to modify splicing to increase production of survival motor neuron protein. The resulting drug, risdiplam—sold as Evrysdi—became the first oral medication approved by the FDA to treat SMA. Mechanistically, it’s an SMN2-directed RNA splicing modifier.

The structure of the Roche partnership mattered as much as the science. Roche took on the heavy lift of late-stage development and commercialization, while PTC earned milestone payments along the way and tiered royalties on worldwide net sales. Those royalties ranged from 8% to 16%.

By the end of this period, PTC looked nothing like the company that had bet its future on a single, disputed Duchenne readthrough drug. Under Peltz’s leadership, it had grown from a research organization into a publicly traded, global commercial organization with multiple approved products and a foundation of technology platforms feeding a broader pipeline. PTC now had a footprint in more than 50 countries, with offices in 20 countries and more than 1,000 employees.

VI. The Emflaza Acquisition & Commercial Acceleration (2016-2017)

Emflaza was a coming-of-age deal for PTC. For years, the company had lived like a classic development-stage biotech: spend heavily, pray the data holds up, and hope regulators agree. Emflaza changed that. It gave PTC something far more stabilizing than hope—real U.S. revenue and a reason to build a commercial machine.

Emflaza (deflazacort) was the first treatment approved in the United States for Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients age five and older, regardless of which mutation caused their disease. That “regardless” was the key. Translarna only applied to the subset of Duchenne patients with nonsense mutations. Emflaza, as a corticosteroid used to reduce inflammation and help preserve muscle function, fit squarely into the standard of care for Duchenne more broadly.

PTC moved quickly and publicly signaled what it was optimizing for: speed to patients and credibility with the community.

"We are pleased the acquisition was completed ahead of schedule, following early conclusion of the antitrust review period," stated Stuart Peltz, chief executive officer of PTC Therapeutics. "We've been engaging with key stakeholders in the DMD community to understand their needs and are working to make Emflaza commercially available as soon as possible. PTC is committed to bringing this important therapy to patients with DMD."

The deal structure also revealed where PTC was at financially. Marathon remained entitled to ongoing payments tied to Emflaza’s annual net sales beginning in 2018—royalty obligations that PTC expected would land in the low to mid-20s as a blended average percentage of net sales. In other words, PTC wasn’t buying a clean, fully owned profit stream. It was buying cash flow with strings attached.

Still, those strings were worth it. PTC expected the transaction to be accretive to earnings and cash flow beginning in 2018, with the transaction expected to close in the second quarter of 2017.

The market didn’t love it at first. Investors saw the baggage: a product wrapped in a fresh pricing controversy, plus a royalty structure that capped upside. On the news, PTC’s stock fell more than 11% in early Thursday trading.

But PTC was buying something Wall Street wasn’t modeling well: infrastructure. Emflaza justified hiring the sales force, building the reimbursement know-how, and setting up patient support services in the U.S. And once those pieces existed, the cost of commercializing the next product—or the next Duchenne product—would drop dramatically. Emflaza wasn’t just a drug. It was a platform for becoming a real commercial rare disease company.

VII. The Roche Partnership & Evrysdi Launch (2018-2020)

If Translarna taught PTC how brutal the regulator’s bar could be, risdiplam taught them something just as important: a platform can actually pay off. And in PTC’s case, the biggest win from that platform wouldn’t be a drug they commercialized themselves. It would be a drug they helped create—then watched Roche and Genentech turn into a global franchise.

Spinal muscular atrophy, or SMA, is one of the cruelest diseases in pediatrics. A genetic defect starves motor neurons of the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein. As those neurons die, muscles weaken, breathing fails, and in the most severe forms, infants often don’t survive without intervention. It’s rare, but for the families living it, it is all-consuming.

PTC’s angle on SMA wasn’t stop-codon readthrough. It was splicing. The biology hinges on two related genes: SMN1 and SMN2. Patients lack functional SMN1, but they still have SMN2—except SMN2 mostly gets spliced in a way that produces too little working protein. The bet behind risdiplam was that a small molecule could shift that splicing pattern and boost SMN protein throughout the body.

That’s exactly what Evrysdi became: an orally administered SMN2 splicing modifier. And the “oral” part is what made it feel like a step-change. At the time, major competing options were either repeated intrathecal injections into the spine (Biogen’s Spinraza) or a one-time gene therapy infusion priced in the millions (Novartis’s Zolgensma). Evrysdi, by contrast, could be taken as a liquid at home. For kids with fragile muscles and families already living in hospitals, that convenience wasn’t a nice feature. It was the product.

The clinical data delivered the kind of clean, emotionally undeniable result rare disease drug developers dream about. In one pivotal study, 29% of infants were able to sit unsupported for five seconds by month 12—something that does not happen in the natural history of Type 1 SMA. That’s the difference between a statistic and a life trajectory.

In 2020, the FDA approved risdiplam, branded as Evrysdi, for the treatment of SMA in adults and children two months of age and older.

Commercially, Roche scaled it fast. Evrysdi’s price was set by patient weight, with costs around $100,000 for an infant and capped at about $340,000 per year. In 2022, Roche reported Evrysdi sales of roughly CHF 1.1 billion (about $1.2 billion). The drug ultimately expanded to approvals in more than 100 countries, with tens of thousands of patients treated globally.

For PTC, the magic wasn’t in selling bottles. It was in royalties. Under the Roche deal, PTC earned tiered royalties on worldwide net sales, and those checks started to meaningfully reshape the company’s financial profile. Roche reported full-year 2024 Evrysdi sales of approximately CHF 1,631 million, which translated into $203.9 million in royalty revenue to PTC for 2024, up from $168.9 million in 2023.

Strategically, Evrysdi did something no investor deck can quite capture: it validated PTC’s core identity as an RNA company. Not a one-drug Duchenne company, and not just a scrappy commercial outfit fighting for survival—but a platform-driven builder of medicines. And that validation, plus the cash it threw off, set the stage for what came next.

VIII. Rare Disease Expansion & Pipeline Diversification (2019-2022)

With the commercial model finally gaining traction, PTC started widening its ambition. Small molecules had gotten the company this far—readthrough for nonsense mutations, splicing for SMA. But for some ultra-rare diseases, the most direct answer isn’t persuading biology to work around a broken gene. It’s replacing the missing function outright.

That’s what pulled PTC into gene therapy.

Upstaza (eladocagene exuparvovec) became the first approved disease-modifying treatment for aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency—and the first marketed gene therapy delivered by direct infusion into the brain. It is approved for patients 18 months and older.

AADC deficiency is devastatingly rare, affecting perhaps only a few hundred patients worldwide. Children with the condition can’t produce dopamine properly, leading to severe developmental delays and profound, lifelong suffering. It’s a fatal genetic disorder that typically begins in the first months of life and touches everything—physical, mental, and behavioral. The suffering can be compounded by episodes of distressing, seizure-like oculogyric crises (where the eyes roll upward), frequent vomiting, behavioral problems, and chronic sleep difficulties. For families, it’s not just a diagnosis. It’s an all-consuming reality, and lives are often severely shortened.

In that context, the clinical results landed with unusual force. In studies of eladocagene exuparvovec, patients who had shown no motor milestone development began to develop clinically meaningful motor skills and neuromuscular function as early as three months after treatment. And the improvements weren’t fleeting—transformational gains were reported to continue for as long as nine years following treatment.

In 2022, PTC Therapeutics announced that the European Commission had granted marketing authorization for Upstaza, the first approved gene therapy developed for AADC deficiency.

PTC’s eladocagene exuparvovec was also approved by the FDA for the treatment of children and adults with AADC deficiency. In the U.S., it is marketed as Kebilidi; in the European Union and United Kingdom, it is marketed as Upstaza.

Strategically, this was a major expansion of what “PTC” could even mean. Nonsense suppression and splicing modulation are small-molecule games. Gene therapy is a different sport entirely—different manufacturing, different delivery, different regulatory expectations. But by taking it on, PTC was building toward something bigger than a handful of products: a broader rare disease platform that could match the modality to the biology, instead of forcing every disease to fit one mechanism.

IX. Translarna Regulatory Battles & European Commission Drama (2020-2024)

For years, Translarna’s European approval had been both PTC’s lifeline and its lingering vulnerability: access granted, but always conditional—always one more study away from being questioned again. In 2023 and 2024, that long-running tension finally snapped into open drama, with the drug that defined the company suddenly at risk of being wiped off the European market.

It started with the evidence that was supposed to settle the debate. A first post-authorisation study, known as Study 020, failed to confirm Translarna’s effectiveness. But it did leave one thread for PTC—and for families—to hold onto: it suggested that a subgroup of patients, particularly those showing a progressive decline in walking ability, might be more sensitive to treatment. In 2016, against that backdrop, the EMA’s human medicines committee, the CHMP, asked PTC to run a new study to evaluate efficacy more definitively.

That request mattered, because Translarna wasn’t just any drug under routine review. It had lived for a decade under conditional authorization—a status that only works if the confirmatory data eventually lock in the benefit.

By early 2024, the CHMP’s view was blunt. After re-examining the available data, the committee confirmed its prior recommendation not to renew Translarna’s conditional marketing authorisation. The conclusion was the one PTC had spent years trying to avoid: the effectiveness of Translarna had not been confirmed.

From the outside, it looked like the end of the road. After a decade on the market, Europe’s scientific gatekeepers were effectively saying: enough. And it wasn’t only about renewal—the EMA also refused to convert Translarna’s conditional approval into a full one. PTC, once again, was fighting to keep the Duchenne therapy available in Europe.

Then came the twist that almost nobody expected.

In a highly unusual move, the European Commission chose not to follow the EMA’s advice and instead kept Translarna’s marketing authorisation in place, despite the EMA having advised against renewal twice, most recently in January 2024. The Commission didn’t publicly explain why it diverged. But the timing—and the intensity of the public reaction—made the likely driver hard to miss: significant outcry from patients across the EU.

Patient advocacy has long been a force in U.S. drug regulation. In Europe, it has historically been less determinative. This moment raised an uncomfortable, fascinating possibility: that European decision-making, too, could bend under the weight of organized patient pressure when the alternative is telling families their only option is gone.

But it wasn’t a permanent save. At the end of March 2025, the European Commission formalised its decision, and the result was definitive: Translarna would no longer be available to patients with DMD in the EU.

All the while, PTC was still trying to solve the problem that had haunted it since the beginning: the United States.

On October 30, 2024, PTC Therapeutics announced that the FDA accepted for review the resubmission of the New Drug Application for Translarna for the treatment of nonsense mutation Duchenne muscular dystrophy. As PTC put it, “The NDA acceptance for review is a significant milestone that brings us one step closer to providing this important treatment to boys and young men living with nonsense mutation Duchenne muscular dystrophy in the United States.”

In the U.S., there were approximately 130 individuals with Duchenne on ataluren, with some having been on the drug for more than 10 years.

X. Recent Evolution: Diversification & Financial Maturity (2023-Present)

By 2023, PTC had crossed an important line. It was no longer just a rare-disease biotech living and dying by the next regulatory decision. It had become a commercial organization with multiple revenue streams, a real operating engine, and enough scale to think in years, not quarters.

That shift coincided with a symbolic turning point at the top.

Stuart Peltz, Ph.D., PTC’s founder and longtime Chief Executive Officer, announced he was stepping down after 25 years. Peltz had led the company since its founding in 1998 and helped pioneer RNA-directed drug development. Over his tenure, PTC grew from a research organization focused on RNA processes into a publicly traded, integrated global biopharmaceutical company developing and commercializing therapies for rare disorders.

His successor came from inside the tent. Matthew Klein, M.D., M.S., F.A.C.S., PTC’s Chief Operating Officer, was named Chief Executive Officer and joined the Board of Directors, effective immediately. Prior to joining PTC in 2019, Dr. Klein was CEO and Chief Medical Officer at BioElectron Technology Corporation.

The numbers now looked like something you’d expect from a mature, revenue-generating company. Total unaudited net revenue for full-year 2024 was approximately $814 million. Total unaudited net product revenue was approximately $601 million. The DMD franchise remained the anchor, with unaudited 2024 revenue of approximately $547 million, including unaudited net product revenue for Translarna of approximately $340 million and for Emflaza of approximately $207 million.

And just as important as the income statement was what it did to the company’s posture. As PTC put it: “In 2024, our commercial team delivered another outstanding performance, we achieved all clinical and regulatory milestones on schedule and we solidified our balance sheet. We now have over $2 billion in cash to support our planned commercial and R&D activities in 2025 and beyond.”

Then came a deal that signaled something bigger than cash: validation.

PTC’s partnership with Novartis for PTC518 was framed as a major vote of confidence in its splicing platform. Under the agreement, PTC will receive an upfront payment of $1.0 billion, up to $1.9 billion in development, regulatory and sales milestones, a profit share in the U.S., and double-digit tiered royalties on ex-U.S. sales.

"PTC518 is the leading oral disease-modifying therapy in development for Huntington's disease and the economics of this agreement are consistent with the promise of this treatment. This collaboration combines PTC's expertise in developing small molecule splicing therapies with Novartis's expertise in global development and commercialization of neuroscience therapies."

And in July 2025, PTC added another notch to its commercial belt—this time in an entirely different category. PTC Therapeutics announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved SEPHIENCE (sepiapterin) for the treatment of children and adults living with phenylketonuria (PKU). The approval includes broad labeling for the treatment of hyperphenylalaninemia in adult and pediatric patients one month of age and older with sepiapterin-responsive PKU.

PKU affects an estimated 58,000 people globally, and SEPHIENCE marked PTC’s entry into metabolic disease—an expansion beyond the neuromuscular disorders that had defined so much of its earlier story.

XI. The Rare Disease Business Model Deep Dive

Rare disease drug development looks like pharma from a distance. Up close, the economics run on a different set of rules—and if you want to understand PTC, you have to understand those rules.

Start with the simple constraint: the market is small because the diseases are rare by definition. In the U.S., orphan drug designation generally applies to conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients. For ultra-rare diseases like AADC deficiency, the entire worldwide patient population may be only a few hundred people. That creates the core paradox of the space. Trials can be smaller than in diabetes or cardiovascular disease, but the commercial opportunity is capped by the reality that there just aren’t that many patients to treat.

Even within Duchenne, the addressable population can shrink quickly once you slice it genetically. Nonsense mutations are estimated to cause DMD in about 13% of patients—roughly 2,000 patients in the United States and 2,500 in the EU.

So how does a company build a business when the patient pool is that tight? Pricing is the lever.

Rare disease drugs routinely land above $100,000 per year, and gene therapies can be priced in the millions for a one-time administration. Elevidys, for example, carries a $3.2 million price tag. Payers may argue about the details, but the underlying reality is hard to escape: when the alternative is no treatment at all, the ethical and political pressure often pushes systems toward coverage.

Then there’s the part that outsiders tend to underestimate: finding the patients. Many rare diseases come with a “diagnostic odyssey,” where families spend years bouncing between specialists before anyone can name what’s happening. That means the commercial job starts long before a prescription. Companies end up funding awareness campaigns, building relationships with specialty centers, and supporting genetic testing programs—because without diagnosis, there is no market.

In Duchenne, genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis and identify the specific disease-causing mutation in the dystrophin gene. And in a world where therapies are mutation-specific, that detail isn’t trivia. It’s eligibility.

This is also why patient advocacy groups are unusually powerful in rare disease. Organizations like Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy don’t just raise awareness; they help fund research, shape trial design, connect families to testing, and advocate directly with regulators. Decode Duchenne, a program of Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, provides free genetic testing, interpretation, and counseling to people with Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy who have been unable to access genetic testing due to financial barriers. Sarepta is a proud sponsor of Decode Duchenne.

Regulation adds yet another twist. Orphan drug designation can bring major incentives, including seven years of market exclusivity in the U.S. and ten years in Europe. Regulators may accept smaller trials, and expedited pathways can compress timelines. For a company, that can mean faster access to revenue. For patients, it can mean access to a treatment while the evidence base is still evolving.

And that’s where the ethical tension comes roaring back. When the drug is for children, and the price is high, every decision becomes a referendum—not just on business strategy, but on values. Marathon’s planned $89,000-per-year pricing for deflazacort triggered outrage in part because the same medication could be purchased in Canada for around $1 per tablet and used off-label in Duchenne. That gap—between international prices and U.S. prices—doesn’t just create bad headlines. It raises hard questions about what “fair” means when the population is tiny, the need is existential, and the costs of discovery have to be paid somehow.

XII. Science & Technology Platform

PTC’s scientific foundation is RNA: how genetic messages are processed, edited, and ultimately translated into protein. That focus has given the company multiple ways to intervene in genetic disease—different tools for different biological problems.

It started with nonsense suppression, the founding idea: if a mutation inserts a premature stop codon, the ribosome quits early and produces a chopped, nonfunctional protein. The goal was to persuade the ribosome to ignore that false stop sign and keep going—restoring enough full-length protein to matter clinically.

Ataluren emerged from that search. In 2007, it was identified as a readthrough agent from a screen of roughly 800,000 low molecular weight compounds. Researchers later characterized its pharmacology, showing ataluren could promote readthrough across each of the three nonsense codons, with the highest efficiency at UGA, followed by UAG, and then UAA.

The appeal of this class of drugs is easy to understand. Nonsense mutations can create truncated, inactive proteins and contribute to diseases including cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and some cancers. Small-molecule nonsense suppressors—often called TRIDs, for translational read-through-inducing drugs—aim to stimulate stop-codon readthrough and restore protein production.

But PTC didn’t stay a one-mechanism company. Its splicing modulation platform became the clearer commercial success. Here, the intervention happens earlier in the RNA lifecycle: a small molecule changes how messenger RNA is spliced, which can increase or decrease production of a target protein. PTC518 is one such splicing-targeted small molecule, and it comes from the same underlying technology lineage that produced risdiplam, marketed as Evrysdi.

Then there’s gene therapy, which is almost the opposite philosophy. Instead of trying to coax the cell into working around a broken gene, gene therapy aims to replace what’s missing. Upstaza is the proof point: direct gene replacement that delivers a functional copy of a defective gene, sidestepping the complexities of splicing and translation modulation entirely. PTC built these capabilities through a mix of acquisition and internal development.

All of this also illustrates the uncomfortable truth about “platform” biotech. The promise is that one technology will produce many drugs quickly. The reality is usually messier: platforms can be powerful, but narrower than hoped, and they don’t always behave consistently across diseases. PTC is a case study in that tension. The nonsense suppression approach that defined the company’s founding produced long-running, debated clinical outcomes, while the splicing platform delivered Evrysdi—the kind of unequivocal win that can reshape a company’s trajectory.

XIII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate

Rare disease biotech is fragmented by design: different companies chase different genes, different mutations, and different patient subgroups. But in Duchenne muscular dystrophy, rivalry is very real. Sarepta has emerged as the category leader, with four approved antisense oligonucleotide therapies and a broad pipeline behind them. And the competitive set isn’t just “another pill.” It’s multiple modalities—exon skipping, gene therapy, and steroids—all competing for attention, trial participants, and, ultimately, the same families.

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-High

The barrier to entry isn’t just money. It’s scientific novelty. Biotech innovation doesn’t slow down, and new tools like CRISPR and next-generation gene therapies have the potential to leapfrog today’s approaches. Duchenne is a good example of how fast the ground can shift: over the last decade, progress accelerated, with eight drugs approved in the last eight years. Regulatory friction and commercial know-how help, but in biotech, a single breakthrough can redraw the map.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Moderate

PTC depends on specialized manufacturing and a web of research and development partnerships. That matters, but it’s not a single-source world—there are alternatives, and supplier power is generally manageable.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Complex

In rare disease, “the buyer” is often a payer making coverage decisions, not the patient who needs the drug. Scrutiny is intense, especially at high prices. But leverage is constrained by the reality of these conditions: small populations, serious disease, and often few meaningful alternatives. In practice, many rare disease therapies still find a path to reimbursement—though not without friction.

Threat of Substitutes: Variable

Substitution depends on the disease and the modality. In Duchenne, the long-term risk to therapies like Translarna is that newer options could change what “treatment” even means. As one observer put it, “These newer products target all tissue—including the heart and diaphragm—which is not the case for currently approved drugs. I think we're going to see some transformative therapies this year and approved the following year.” If gene therapy or other next-gen approaches deliver durable benefit, they can substitute for chronic therapies rather than merely compete with them.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: Limited

Rare disease doesn’t naturally reward scale the way mass-market pharma does. Populations are small, and manufacturing efficiency helps, but only at the margins.

Network Economies: Moderate

In rare disease, networks are assets. Patient registries, specialty clinicians, treatment centers, and advocacy relationships compound in value over time—and they can make future launches faster and more effective.

Counter-Positioning: Eroded

PTC’s early lead in nonsense suppression was once a clear differentiator. Over time, as the evidence around the approach remained debated and competitors advanced alternative modalities, that edge weakened.

Switching Costs: High

When a patient is stable on a therapy—especially in progressive pediatric disease—switching isn’t like changing brands. It carries medical uncertainty and real emotional cost for families.

Branding: Strong in Communities

PTC’s long presence in neuromuscular disease, and its deep engagement with advocacy organizations, created trust that’s hard to manufacture quickly—and hard for competitors to displace.

Cornered Resource: Moderate

Some assets are simply hard to replicate: a durable royalty stream like Evrysdi’s, hard-won geographic approvals, and the institutional knowledge embedded in those launches.

Process Power: Moderate

Over decades, PTC has built a repeatable operating capability: running rare disease trials, navigating regulators across regions, and commercializing globally in small, specialized markets. That process know-how becomes an advantage precisely because it’s learned the hard way.

XIV. The Bear vs. Bull Case

Bull Case

The diversified portfolio is the heart of the bull story. For full-year 2025, PTC guided to total revenue of $600 million to $800 million, spanning its in-line products, potential new launches, and Evrysdi royalty revenue. In other words: the company is no longer betting its future on any single program. Emflaza, Translarna (in the markets where it remained available), Evrysdi royalties, and whatever comes next each contribute a real piece of the picture.

The Novartis deal is the kind of validation platform biotechs chase for years. PTC didn’t just sign a partnership; it signed one with a global pharma player that knows neuroscience and knows how to scale. William Blair, for example, put PTC518 at a 50% probability of success and modeled peak revenue of $5 billion, with about $1.43 billion of that going to PTC under the economics of the agreement.

The balance sheet buys time—something biotech companies rarely get. With more than $2 billion in cash, PTC had the flexibility to keep investing in the pipeline without immediate pressure to raise money on unfavorable terms.

Patient advocacy relationships are another underappreciated asset. Two decades of close work with the DMD community created trust and connectivity that are hard for a newer competitor to replicate quickly, even with strong science.

And there’s still room to grow geographically. PTC has been expanding commercial access for Translarna across Europe, the Middle East, Latin America, and Asia Pacific, building a footprint that can support launches beyond Duchenne.

Bear Case

The biggest bear argument is the simplest: questions about efficacy don’t go away just because a drug has been on the market for a long time. The ESSENCE findings reinforced that the expected functional benefits of exon-skipping therapies have not yet been demonstrated, even after years of commercial use. It’s a reminder of the risk in accelerated approvals built on surrogate endpoints—and it inevitably pulls Translarna back into the same kind of debate: what’s the real-world, clinically meaningful benefit, and how confidently can you prove it?

Regulatory risk is not theoretical—it’s already happened. The European withdrawal of Translarna is a case study in what conditional approvals really mean: access can be granted early, and it can be taken away when confirmatory evidence doesn’t settle the question.

Competition in Duchenne is also getting sharper. As one example from the field put it: “Dyne's drug has the potential to transform the care of those living with DMD amenable to exon 51 skipping. The company plans to submit an application for accelerated FDA approval in the second quarter of next year.” In Duchenne, momentum shifts fast, and new modalities can change what physicians and families view as worth trying.

Emflaza faces a more traditional pharmaceutical risk: generics. Performance was pressured by the expiration of Emflaza’s orphan drug exclusivity in February 2024, which changes the economics of that franchise.

And finally, there’s the existential threat to chronic small-molecule therapies: gene therapy. If one-time, potentially curative treatments prove durable over years, the logic of long-term daily medication starts to look less compelling—no matter how well commercialized it is.

Key Metrics to Watch

Translarna Patient Numbers and Retention: The clearest real-world signal. If patients stay on therapy and physicians keep prescribing, it suggests belief in meaningful benefit—especially in the markets where access remains.

Evrysdi Royalty Growth: This is the closest thing PTC has to a steady annuity. The trajectory of Roche’s SMA franchise will tell you how durable that cash flow stream really is as the category matures.

New Product Launch Trajectory: Sepiapterin and Kebilidi launches in 2025–2026 will show whether PTC can repeatedly commercialize new products, not just manage the ones it already has.

XV. Lessons for Founders & Investors

The long game in biotech is genuinely long. Stuart Peltz has led PTC as CEO since founding the company in 1998 and helped pioneer RNA-directed drug development. It took roughly a quarter-century to get from a scientific insight to something that resembled sustainable commercial traction. In this industry, patience isn’t a virtue. It’s a prerequisite—and so is the ability to finance years of progress before you can finance yourself.

Regulatory strategy is business strategy. PTC’s decision to go Europe-first with Translarna wasn’t just a regulatory preference; it was a survival tactic. Different agencies apply different standards, weigh uncertainty differently, and move on different timelines. Sequencing your submissions to match that reality can be the difference between staying alive long enough to generate the next set of data—or disappearing before you get the chance.

Platform biology creates optionality, not certainty. PTC’s story is a reminder that “platform” doesn’t mean “inevitable.” The same company produced Evrysdi through splicing modulation, and years of debated evidence through nonsense suppression. A platform is a way to take more shots on goal. It’s not a promise that the shots will go in.

Portfolio construction reduces binary risk. A single-asset biotech lives and dies on one trial readout, one advisory committee, one regulator’s interpretation. PTC’s evolution into a multi-product company—across multiple diseases and modalities—didn’t eliminate risk, but it made the company far harder to kill.

Patient advocacy is strategic, not just ethical. Rare disease drug development is one of the few corners of healthcare where patients and families can become a real force in the system. When PTC announced the FDA had accepted its Translarna resubmission, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy founder and CEO Pat Furlong said, “We thank FDA for accepting the Translarna NDA for review.” That kind of relationship doesn’t just matter emotionally. It affects trial recruitment, shapes public pressure, and builds the trust that makes commercialization possible in tiny, tight-knit communities.

Partnership timing matters enormously. The Roche deal for risdiplam in 2011 came before PTC had the global muscle to develop and launch an SMA drug at scale. Opting for milestones and royalties on Evrysdi—rather than trying to commercialize it alone—fit the company PTC was at the time, not the company it wanted to be someday.

Surviving near-death experiences builds institutional resilience. FDA rejections, conditional approvals that never felt fully secure, non-renewal threats in Europe, and the constant need to fund expensive science through uncertainty—PTC lived through all of it. Each crisis forced the organization to get better at operating under pressure. In biotech, that kind of scar tissue can become a competitive advantage.

XVI. Epilogue & Current State

By late 2025, PTC Therapeutics sat at a familiar place in biotech: right at the edge of the next chapter, with enough scale to matter and enough uncertainty to stay interesting. As the company put it, “Our strong fourth quarter rounds out a year of significant accomplishment across every part of our company.” This was no longer the fragile, single-asset wager of the early Translarna years. It was a diversified rare disease business with more than $800 million in annual revenue, over $2 billion in cash, and products reaching patients across multiple continents.

But PTC’s world didn’t get easier just because it got bigger. The competitive landscape in Duchenne kept moving. Sarepta’s approved exon-skipping products, in combination, can treat roughly 30% of all DMD cases. And in June 2024, Sarepta received FDA approval to expand ELEVIDYS for use in ambulatory DMD patients aged four and older—another reminder that the standard of care in Duchenne is still being rewritten in real time.

Even the leaders feel the volatility. Sarepta faced a sharp reversal when shares fell nearly 40% after the company said a trial intended to confirm the efficacy of two already-marketed Duchenne drugs failed. In other words: progress is real, but so is the fragility of evidence in diseases where trials are hard, endpoints are noisy, and families are counting months, not decades.

For PTC, the near-term future hinged on a handful of high-impact catalysts: the regulatory fate of Translarna in the United States, the launch trajectory of Sephience in PKU, and the continued march of the Novartis-partnered Huntington’s disease program.

What stands out most in this story isn’t that the science was messy or that regulators disagreed. That’s biotech. It’s the persistence required to stay in the game long enough for any of it to matter. Stuart Peltz once described himself as “optimistic, relentless and undeterred. I always think there is a solution to every problem. And I don't give up.” That mindset isn’t a personality quirk here; it’s a core operating requirement.

And the central tension never really goes away. Rare disease companies often need high prices to pay back enormous R&D costs across tiny patient populations. Those same prices can create access barriers that leave some patients untreated. Every approval is a breakthrough for families who can get the drug—and, sometimes, a fresh kind of grief for families who can’t.

So PTC’s story isn’t a clean victory lap. It’s a case study in endurance, pivots, and the hard work of turning a mechanism into medicine. The nonsense suppression idea that launched the company in 1998 didn’t deliver the universally transformative outcomes that early believers hoped for. But along the way, PTC built something durable: commercial capabilities, regulatory scar tissue, and a portfolio that serves thousands of people living with devastating rare diseases.

Whether you see that as execution triumphing over an imperfect scientific bet—or as a cautionary tale about the gap between elegant biology and clinical reality—depends on where you sit. What doesn’t depend on perspective is this: PTC survived when many biotechs didn’t, adapted when the original plan wasn’t enough, and kept pushing into diseases where “no options” is still the default.

XVII. Further Learning

Top Resources for Deep Dive

SEC Filings: PTC’s 10-Ks and 10-Qs (2013 to present) are the most complete record of how the company actually evolved—strategy shifts, product-by-product performance, and the risk factors that spell out what can still go wrong.

FDA and EMA Approval Documents: If you want to understand why the same drug can be “promising” to one regulator and “not proven” to another, read the primary documents. The reasoning is all there, in plain terms, along with exactly where the evidence did—and didn’t—clear the bar.

Clinical Trial Publications: The key ataluren and risdiplam papers, including in the New England Journal of Medicine and Lancet Neurology, are where the story gets real. Endpoints, patient populations, subgroup debates—it’s the closest thing to the ground truth.

Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy Resources: This is the patient-side of the story: how advocacy groups fund research, shape trials, support genetic testing, and, at times, apply pressure that changes what “approval” looks like in practice.

JPMorgan Healthcare Conference Presentations: These annual updates are PTC’s public narrative in real time—what management says the priorities are, how they frame the tradeoffs, and how the story shifts as programs succeed, stall, or spark controversy.

FDA Advisory Committee Meeting Transcripts: For the unfiltered version of regulatory tension, nothing beats the transcripts. You see the questions reviewers asked, the disputes over clinical meaningfulness, and why decisions around drugs like Translarna became as much about uncertainty as about data.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music