Phillips 66: From Spin-off to Energy Infrastructure Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

The boardroom at ConocoPhillips’ Houston headquarters had that particular kind of quiet you only get right before something irreversible. It was July 2011. CEO Jim Mulva stood at the front of the room, teeing up a plan that wasn’t a cost cut or a portfolio tweak—it was a clean break.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he began, “we’re proposing to unlock billions in shareholder value by doing what no major integrated oil company has done—completely separating our downstream from upstream.”

This wasn’t a divestiture. It was corporate surgery on a Fortune 5 company.

Nine months later, on May 1, 2012, Phillips 66 started trading as a standalone company—at the time, the largest energy spin-off in history. The new business walked out the door with the refineries, the pipelines, and the brand: that familiar Phillips 66 shield that had been riding along American highways since 1927.

Wall Street didn’t exactly throw a parade. To many analysts, it looked like a pile of volatile, regulated, low-glamour assets. Refining margins could swing wildly. Environmental rules were tightening. And the shale revolution was only just beginning to reorder where American oil and gas would come from—and how it would move.

And yet: the “left-behind” downstream company didn’t just survive. It compounded.

That roughly $20.5 billion spin-off grew into a Fortune 50 company, generating more than $145 billion in revenue by 2024. Phillips 66 found a lane and stayed in it—building out midstream and chemicals while others chased upstream growth, and pairing that strategy with a shareholder-return machine. Since July 2022 alone, it returned $12.5 billion to shareholders through buybacks and dividends.

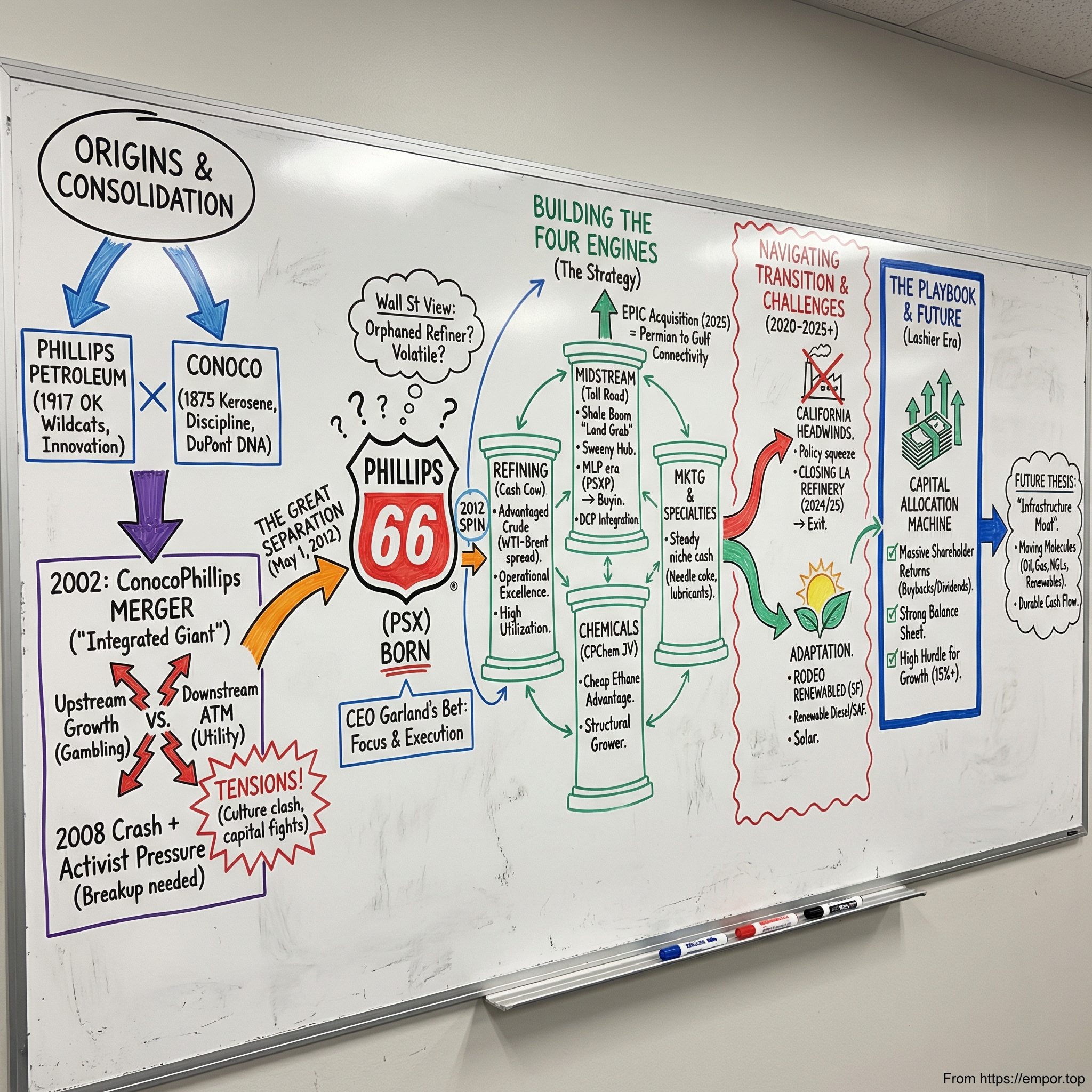

This is the story of how a cast-off downstream business became an energy infrastructure powerhouse. It’s a playbook for focus, capital discipline, and manufacturing advantage in businesses everyone loves to dismiss as “commodities.” Along the way, we’ll see how leadership under Greg Garland turned Phillips 66 into four profit engines—refining, midstream, chemicals, and marketing—and then kept them running through the realities of the energy transition, California’s policy headwinds, and the boom-bust rhythm of commodity markets.

A few big ideas keep surfacing. First: breakups can create enormous value—if the separation is real, and the new company actually behaves like a new company. Second: “boring” assets like pipes, fractionators, and storage tanks can be extraordinary businesses when they’re positioned right and managed well. And third: in a world increasingly focused on decarbonization, owning the infrastructure that moves molecules can matter as much as—or more than—owning the molecules themselves.

We’ll start with Frank and L.E. Phillips striking oil in Oklahoma in 1917, move through the mega-merger that formed ConocoPhillips, and then zoom in on the strategic tensions that made the divorce inevitable. From there, we’ll track how Phillips 66 built a midstream machine during the shale boom, why it converted its San Francisco-area facility to renewable diesel, and how it navigated the brutal economics and politics that ultimately forced difficult decisions in California.

What makes Phillips 66 so interesting is how consistently it has generated cash through cycles. While the future of energy grabs headlines, Phillips 66 has made its money in the present—moving and processing the fuels and feedstocks that still power most of the global economy. It’s an empire built out of unglamorous, irreplaceable infrastructure. And as we’ll see, it offers unusually clear lessons about corporate strategy, capital allocation, and adapting legacy assets for a new era.

II. The Pre-History: Phillips Petroleum & Conoco Legacy

This story starts far from Houston boardrooms, in the grit and gamble of early oil-country Oklahoma. In Bartlesville, two brothers—Frank and L.E. Phillips—were trying to make something of themselves after a string of false starts. They’d bounced through jobs, tried their hands at business, and then did what ambitious men did in the early 1900s when they ran out of conventional options: they went looking for oil.

It didn’t go smoothly. They drilled dry holes. The money got tight. Their standing in town took hits. L.E.’s wife urged him to stop. But the Phillips brothers had that defining trait of the great wildcatters: they could absorb humiliation and keep going.

When they finally hit oil near Bartlesville, they didn’t treat it like a lucky payday. They treated it like a beginning. Plenty of operators were content to drill and flip leases. Frank Phillips wanted something bigger—an operation that didn’t just pull oil out of the ground, but refined it, moved it, and ultimately sold it to the end customer. In 1917, they incorporated Phillips Petroleum Company, with about $3 million in assets—staggering growth from where they’d started only a dozen years earlier.

A decade later, the company stumbled into one of the most iconic brand moments in American business. In 1927, Phillips officials were road-testing a new gasoline blend on Route 66. At one point the car hit 66 miles per hour, and the name snapped into place. Highway. Speed. Modernity. That “Phillips 66” shield became a symbol of the new American lifestyle—cars, road trips, and the idea that the country was shrinking with every mile of paved highway. By 1930, Phillips 66 stations were spreading across the Midwest and Southwest, and the brand was becoming part of the landscape.

While Phillips was rising out of Oklahoma, an older, different oil story was already underway farther west. Conoco began life in 1875 as the Continental Oil and Transportation Company, making it one of the earliest petroleum marketers in the American West. It started with kerosene—lighting fuel—distributed across frontier towns. It’s hard to overstate how early that is. Conoco was moving petroleum products before the telephone existed.

Over time, Conoco changed hands and shape. Standard Oil owned it briefly before the 1911 antitrust breakup. Ownership shifted again. Assets accumulated. By the 1920s, Conoco had evolved from a marketer into a more integrated business, with operations spanning production, refining, and sales from the Rockies into the Midwest. And in 1981, DuPont bought it—an era that mattered, because DuPont brought a particular kind of operational discipline and industrial process mindset. Conoco carried that DNA long after DuPont exited in 1998.

Across the 20th century, both companies rode the same powerful wave: America’s automotive boom. As car ownership exploded, stations multiplied, refineries expanded, and pipeline networks knitted the country together. Phillips built a reputation for innovation—developing synthetic rubber during World War II, and later pushing into plastics like polyethylene in the postwar era. Its Bartlesville research center became famous in the industry, generating thousands of patents and giving Phillips the feel of an energy company with an R&D lab at its core.

Then came the late-1990s and early-2000s consolidation cycle—Big Oil’s recurring urge to bulk up. Phillips leaned into it. In 2000, it formed a major chemicals joint venture with Chevron, combining their petrochemicals and plastics businesses into Chevron Phillips Chemical, a 50–50 partnership that still exists today. That same year, Phillips acquired ARCO Alaska from BP, adding critical North Slope production.

But the defining deal was 2001, when Phillips bought Tosco for $7.5 billion. Tosco brought real heft: refining assets, major West Coast exposure, the Union 76 brand, and Circle K convenience stores. Overnight, Phillips looked less like a successful producer with a marketing arm and more like a full-scale downstream powerhouse. CEO Jim Mulva, who’d taken over in 1999, had been assembling a company with serious refining and retail reach—building exactly the kind of downstream platform that, a decade later, would be carved out into Phillips 66.

And underneath the asset maps and deal decks, the two companies still felt different. Phillips had the wildcatter streak—entrepreneurial, tech-forward, willing to take swings, with Bartlesville functioning like a campus of engineers and chemists. Conoco, shaped by DuPont, operated with a more formal industrial rhythm: process-focused, financially conservative, internationally seasoned. In 2001, with oil prices strengthening and consolidation in the air, those differences didn’t look like a problem. They looked like complementary strengths.

They were about to find out that “complementary” can also mean “in tension”—especially when you try to run upstream and downstream, under one roof, with two cultures pulling in different directions.

III. The ConocoPhillips Era: Merger & Tensions (2002–2011)

The scene was classic corporate choreography: a press conference at the Sheraton New York on November 18, 2001. Jim Mulva of Phillips and Archie Dunham of Conoco stood shoulder to shoulder, smiles fixed, hands clasped, announcing what they called a “merger of equals.” Together, they said, they’d create America’s third-largest oil company—worth about $35 billion—and the fifth-largest integrated player in the world.

Mulva promised it wasn’t some defensive mash-up. “This isn’t about cost-cutting,” he told reporters. “It’s about growth, scale, and competing with the supermajors.”

But under the stage lighting, the control story was pretty clear. Phillips shareholders would end up with 56.6% of the combined company. Dunham would take the chairman title first, but Mulva would be CEO—the person actually running the machine. The headquarters would move to Houston, a symbolic reset button. When the deal closed in August 2002, ConocoPhillips emerged as a true integrated giant: roughly 1.7 million barrels per day of refining capacity, around 2 billion barrels of proved reserves, and about 17,000 retail outlets around the world.

For a while, the timing looked brilliant. Oil prices, stuck in the $20 to $30 range through much of the 1990s, started climbing into what would become a historic boom. By 2005, crude hit $70. By 2008, it would briefly touch $147. ConocoPhillips surfed that wave, with net income rising from $4.7 billion in 2003 to $11.9 billion in 2007. It pushed even harder in 2006, buying Burlington Resources for $35 billion—the largest acquisition in the company’s history. Burlington delivered a massive natural gas position, right as technology was beginning to unlock resources that had long been considered out of reach.

And yet, inside the company, the real story was getting darker. The problem wasn’t the price of oil. It was the structure.

Upstream and downstream lived on different planets. Upstream demanded enormous, long-dated bets with uncertain payoffs—projects that could take years and billions of dollars before producing a single barrel. Downstream needed constant, steadier investment: maintenance, turnarounds, safety, compliance. Different risk profiles, different time horizons, different definitions of “success.”

When you force those worlds to share one capital budget, you don’t get harmony. You get politics.

Insiders later described the dynamic as a “civil war in slow motion.” The upstream side—heavy with legacy Conoco leadership—saw itself as the growth engine. When prices were high, they argued the company should plow cash into reserves and production. The downstream side—more Phillips in heritage—felt like it was being treated as the utility that funded everyone else’s ambition. One refining executive reportedly put it bluntly: “We’re the ATM that funds their gambling expeditions.”

Then came 2008, and the whole integrated dream took a hit. Oil collapsed from $147 to $31 in roughly five months. ConocoPhillips’ market cap cratered from $149 billion to $60 billion. In the fourth quarter of 2008, the company posted a $16.9 billion loss, driven largely by upstream writedowns. Downstream wasn’t having a good time—refining margins were ugly—but it remained a steadier source of cash. The board was left staring at an uncomfortable question: were they trying to be excellent at too many things, and ending up great at none?

Activist investors saw the opening. By 2009, hedge funds were circling, running a simple calculation: the parts looked worth more than the whole. Upstream pure-plays traded at richer multiples. Downstream names traded differently. But ConocoPhillips—an integrated blend—was stuck with a discount that had started to feel less like “diversification” and more like a punishment for complexity.

Ralph Whitworth of Relational Investors became the most credible voice pushing the idea. By 2011, he’d built roughly a $2 billion stake. His message to the board was straightforward and tough: split the businesses, and let each be valued—and managed—on its own merits. Whitworth wasn’t trying to flip the company overnight. He was a boardroom operator who pushed for performance, and that made his argument harder to dismiss.

Meanwhile, internal work was pointing to the same conclusion. A 2010 analysis found that upstream and downstream shared surprisingly little beyond the letterhead. Integration sounded great in theory, but in practice the synergies were thin. Trading functions didn’t naturally align. Technology didn’t transfer in meaningful ways—drilling breakthroughs didn’t make refineries run better. “One company” was starting to look like a managerial abstraction more than an operating reality.

Mulva eventually made the pragmatic call. Instead of fighting a battle he couldn’t win—or dragging the company through a drawn-out proxy war—he chose to lead the separation himself. In July 2011, he announced plans to spin off the downstream business and framed it as strategic focus, not surrender.

The market’s reaction said everything. ConocoPhillips stock jumped 7% that day, adding about $5 billion in value. Wall Street wasn’t debating the philosophy of integration. It was placing a bet: focus beats sprawl in modern energy.

IV. The Great Separation: Spin-off Strategy & Execution (2011–2012)

By January 2012, ConocoPhillips’ Houston tower looked less like a corporate headquarters and more like a command center. The conference room on the 47th floor had been converted into a full-time war room: whiteboards, timelines, regulatory checklists, and an org chart that tried to do the impossible—turn one company into two without breaking either.

Greg Garland, tapped to lead the new downstream business, kept it brutally simple for the transition team: they had 120 days to stand up a Fortune 100 company.

The mechanics were straightforward on paper and messy in real life. ConocoPhillips stockholders would receive one share of the new company for every two ConocoPhillips shares they held, in a tax-free distribution. Clean, elegant, and instant.

Everything underneath that was anything but. Thousands of decisions had to be made at speed. Which refineries went into the new entity? Who owned which pipelines—especially the ones that connected upstream barrels to downstream plants? How do you split up trading activity without creating risk, confusion, or finger-pointing the first time the market moves against you?

Even the name mattered more than it should have. They could have invented something new. Instead, after weeks of debate, the team landed on Phillips 66. It wasn’t nostalgia—it was leverage. The shield was still widely recognized, especially in the Midwest and Southwest. Garland’s logic was hard to argue with: why spend years and millions building a brand when you already owned an American icon?

On April 4, 2012, ConocoPhillips’ board gave final approval for the spin-off. The new company would officially come to life at 12:01 a.m. on April 30, with trading to follow the next morning. Inside the organization, it landed with a strange mix of excitement and disbelief. Employees got emails with subject lines like “Your New Company,” explaining new benefits, new reporting lines, and new email addresses—operating instructions for a business that, legally, didn’t exist yet.

April’s investor roadshow became Garland’s debut as a CEO. He wasn’t a glossy finance pitchman. He’d joined Phillips Petroleum in 1980 as a chemical engineer and worked his way up through operations. His message to Wall Street sounded like someone who had spent time in hard hats and control rooms: “We’re not trying to find oil in Kazakhstan. We’re running great assets in great markets with great people.”

The deck laid out what Phillips 66 would inherit: 15 refineries with about 2.2 million barrels per day of capacity, including major complexes like Wood River and Borger; roughly 10,000 miles of pipelines; a 50% stake in DCP Midstream, a major natural gas gatherer and processor; and 50% of Chevron Phillips Chemical, a steady earner.

Still, the early Q&A was heavy with skepticism. Refining margins were famously volatile, and the “crack spread”—the gap between what refineries pay for crude and what they sell gasoline and diesel for—could swing fast with supply, demand, and geopolitics. Environmental regulation was tightening. Electric vehicles hung over the long-term gasoline narrative. One analyst asked the question everyone was thinking: why isn’t this just ConocoPhillips dumping its least attractive assets?

Garland didn’t try to charm his way out of it. He reframed it. They weren’t a refining company that happened to own some other stuff, he argued. They were an integrated downstream business, where the mix was the point. When refining got squeezed, midstream could help stabilize results. When chemicals softened, refining might carry the load. The portfolio itself was the strategy.

Then came May 1, 2012—day one as PSX. The stock opened at $31.75, implying a market cap of about $20.5 billion. Trading volume surged as index funds adjusted and arbitrage trades unwound. By the close, the stock was up modestly. Nothing euphoric. Nothing broken. A steady, unglamorous start—very on brand.

On the first earnings call as an independent company, Garland set expectations like an operator, not a promoter: they weren’t going to promise the moon. They were going to run the assets well, generate cash, and return it to shareholders. The inaugural quarterly dividend came in at $0.20 per share—deliberately modest. And inside the company, Garland built leadership around experienced Phillips veterans rather than splashy outside hires. The message was clear: Phillips 66 intended to win through execution.

By the end of 2012, the market had changed its mind in a hurry. PSX had nearly doubled, lifted by a wide spread between Brent and inland North American crude and by cheap natural gas and NGL feedstocks that advantaged the chemical business. The supposed downstream “orphan” had stepped out of ConocoPhillips’ shadow—and the shale boom was about to give it even more room to run.

V. Building the Downstream Champion (2012–2016)

At 3 a.m. on a freezing February morning in 2013, the Ponca City refinery control room was lit up like a cockpit. Operators tracked temperatures and pressures, alarms chirped, radios crackled. Greg Garland was there in person—wide awake, walking units with the night shift.

It wasn’t a staged visit. It was a statement about how Phillips 66 was going to run itself. Garland had come up through operations, and he pushed a simple belief: you don’t manage refineries and terminals from a spreadsheet. You manage them by understanding how they actually work, on the ground, in real time. That hands-on posture—equal parts discipline and urgency—became the cultural reset that turned Phillips 66 from a spin-off “leftover” into a downstream company with momentum.

The early strategy was straightforward, almost boring in its phrasing: optimize the base business while building new earnings streams. The hard part was doing it all at once. Refining demanded huge sustaining capital just to keep plants safe and reliable. Midstream was staring at a once-in-a-generation buildout opportunity as shale volumes surged. And Wall Street wanted proof—fast—that the spin-off would mean more than a new logo and a new ticker.

The first big tailwind was the Brent-WTI spread. As U.S. shale production took off, domestic crude prices (WTI) broke away from the global benchmark (Brent). At times, the gap blew out to more than $20 a barrel. For Phillips 66, that dislocation was a gift. Inland refineries like Wood River in Illinois and Ponca City in Oklahoma could buy discounted domestic crude and sell gasoline and diesel into markets priced off the higher global level. The geography that looked like “flyover” suddenly looked like a competitive moat.

Garland’s team didn’t admire the opportunity—they attacked it. They reversed pipeline flows, expanded rail capabilities, and tuned refineries to run the barrels that were suddenly abundant. At Wood River, the company put roughly $400 million into modifications that, according to internal estimates, drove about $500 million a year in incremental earnings. In refining, paybacks like that are rare. When you get one, you move.

The second engine was chemicals, through Chevron Phillips Chemical, the 50–50 joint venture with Chevron. Shale didn’t just change crude markets; it flooded the U.S. with cheap natural gas and NGLs, the key feedstocks for petrochemicals. That advantage was structural, not cyclical. CPChem leaned into it with major expansion plans, including new Gulf Coast ethylene capacity. For Phillips 66, the result was something every refiner craves: a meaningful earnings stream that didn’t rise and fall with the crack spread.

Then there was the segment analysts loved to ignore: marketing and specialties. It wasn’t flashy, but it threw off cash. Phillips 66 owned valuable retail real estate, sold branded fuel, and made higher-margin products like lubricants and specialty coke. In specialties, products like needle coke—used in electrodes for steelmaking—delivered returns on capital that could rival the company’s best growth projects. This part of the portfolio didn’t need grand reinvention. It needed steady execution, and it delivered steadier results.

The most important change, though, was cultural. Under ConocoPhillips, downstream had often felt like a division inside a bigger upstream story—slower, more political, and frequently stuck justifying why it deserved capital. As a standalone company, Phillips 66 moved with more entrepreneurial speed. A fractionator proposal at the Sweeny Hub went from idea to board approval in about 60 days. Leaders described it as a shift from “studying” to “doing”—a recognition that in this business, waiting for perfect information often means watching the opportunity move on without you.

That urgency didn’t mean recklessness. Safety and reliability were non-negotiable, and the company pushed hard on performance. Total recordable injury rates fell sharply in the early years after the spin. Underneath it all was a capital allocation doctrine that Garland repeated relentlessly: fund sustaining capital first, then pursue high-return growth, and only then return excess cash to shareholders. The subtext mattered just as much as the policy: no empire building, no trophy deals, no growth for growth’s sake. Phillips 66 walked away from acquisitions that might have made the company bigger, but not better.

By July 2016, the move into a new headquarters campus on 14 acres in Houston’s Westchase district made the transformation feel tangible. The building was modern but restrained—more “operators and engineers” than “oil palace.” Internally, employee engagement improved dramatically compared to the downstream days inside ConocoPhillips, as people felt they were finally working for a company that was built around their business, not merely tolerating it.

And the market noticed. By late 2016, PSX had climbed from the low $30s at the spin to around $80—an extraordinary run for a company many had dismissed as a volatile refiner. Phillips 66 generated massive operating cash flow, invested heavily in growth, and still returned billions to shareholders. The early verdict was clear: downstream wasn’t dying. In the right hands, it was a cash-generating industrial machine.

Phillips 66 had built the champion. The next question was what to do with that cash and capability—because the shale boom was accelerating, and the infrastructure to move all those molecules didn’t yet exist.

VI. The Midstream Build-Out & MLP Strategy (2013–2020)

If refining was Phillips 66’s cash engine, midstream was the company’s land grab.

Picture the Sweeny Hub on the Texas Gulf Coast in September 2014. In the humid early light, it didn’t look like a “project.” It looked like a new kind of factory—towering fractionators, pipe racks stretching out like highways, and a purpose-built system designed to handle about 100,000 barrels a day of natural gas liquids.

NGLs are the in-between molecules of the shale era—ethane, propane, butane, and heavier liquids that come up alongside natural gas and oil. Fractionation is simply the sorting process: take the mixed stream and separate it into pure products, each with its own price, buyer, and destination. Sweeny mattered because shale had unleashed more of these molecules than the industry’s infrastructure was built to handle. Phillips 66 was betting that the bottleneck wouldn’t be in the ground. It would be in the middle.

The thesis was clean: don’t chase drilling acreage. Own the routes and the choke points. If shale was going to flood the country with new volumes, Phillips 66 wanted to be the toll collector—processing, storing, fractionating, and moving those molecules from where they were produced to where they were consumed.

To finance that build-out, Phillips 66 leaned hard into the era’s favorite structure: the Master Limited Partnership. In the second half of 2013, it took Phillips 66 Partners (PSXP) public. At the time, MLPs were a near-perfect match for pipelines and terminals: no corporate income tax at the partnership level, most cash paid out, and yield-hungry investors eager to fund anything that looked stable and infrastructure-like.

The playbook was the “dropdown.” Phillips 66 would use its balance sheet to build or buy midstream assets, get them up and running, then sell them to PSXP at attractive valuations. The partnership got cash-flowing assets it could distribute; the parent got capital back, booked gains, and still kept influence over the system it was assembling.

But the real compounding came from building assets with contracts that behaved more like infrastructure than commodities. The Beaumont Terminal expansion added large crude storage capacity at exactly the moment the U.S. was opening up to a new export reality, especially after the crude export ban was lifted in 2015. The Freeport LPG Export Terminal positioned Phillips 66 to ship propane abroad into markets like Asia and Europe, where demand for U.S. NGLs was rising. Again and again, the formula was the same: lock in long-term contracts with solid counterparties, keep commodity price exposure limited, and earn returns that cleared the cost of capital with room to spare.

Sitting at the center of the whole strategy was DCP Midstream, where Phillips 66 owned 50%. DCP ran an enormous gathering and processing footprint—plants, pipelines, and logistics that touched a meaningful slice of U.S. gas production. But there was a catch: when commodity prices collapsed in 2014 and 2015, DCP’s more commodity-sensitive contract mix got squeezed. Phillips 66 leaned in anyway, supporting the business and pushing toward more fee-based arrangements designed to hold up when prices didn’t.

Then, in 2014, Warren Buffett showed up in a way that made the midstream story feel even more real. Berkshire Hathaway traded more than 19 million of its 27.2 million Phillips 66 shares to acquire Phillips Specialty Products Inc., a niche business that makes additives that help crude flow more efficiently through pipelines. Buffett wasn’t buying a “theme.” He was buying something unsexy with staying power—one more signal that the plumbing of the energy system could be a durable franchise.

Meanwhile, Phillips 66 kept quietly stitching together a national logistics network. Over time, the company came to operate and/or own more than 22,000 miles of pipeline across the United States. The point wasn’t just scale. It was connectivity. When refineries needed crude, Phillips 66 could often move it on its own system. When refineries produced gasoline, diesel, and other products, Phillips 66 terminals could store and distribute them. And on the margin, that control gave its trading and optimization teams more ways to capture location and timing advantages.

Still, by the late 2010s, the MLP model was losing its shine. The promise of steady distributions depended on constant access to capital, and when energy markets turned and financing tightened, the whole sector rerated. Phillips 66 eventually decided it didn’t need two sets of stakeholders arguing over the same assets. In 2019, it bought in the public units of PSXP for $3.7 billion—simplifying the structure and pulling the midstream cash flows fully back into the parent.

That set the stage for what would later look like the endgame of the whole strategy: the 2023 integration of DCP Midstream, done through a $3.8 billion transaction that increased Phillips 66’s economic stake and consolidated control. The company hit $500 million in synergies, beating its original $400 million target. It also gained a much stronger position in an NGL value chain that ran from shale basins to Gulf Coast fractionation, including major pipes like Sand Hills and Southern Hills moving large volumes out of the Permian and Eagle Ford.

By the time the dust cleared, the “orphaned” pipelines and terminals that came with the 2012 spin weren’t side assets anymore. They were a central pillar—an infrastructure business with midstream adjusted EBITDA approaching $4 billion on a run-rate basis and a stated target of $4.5 billion by 2027. While the headlines obsessed over the future of transportation, Phillips 66 was building something more quietly powerful: the routes that would keep moving molecules—whatever they are—for a long time to come.

VII. Navigating Energy Transition & California Challenges (2020–2025)

The news landed with a thud on October 16, 2024. In a press release that read almost too plainly for what it meant, Phillips 66 said it would close its Los Angeles Refinery—138,700 barrels per day, spread across two sites in Wilmington and Carson, covering roughly 650 acres.

This wasn’t some marginal plant. The facility had been refining crude since 1913. It had lived through world wars, oil embargoes, and earthquakes. But what finally broke it wasn’t a supply shock or a safety incident. It was the slow squeeze of economics in a state that has made clear, year after year, that fossil fuels have no long-term political runway. CEO Mark Lashier put it diplomatically, but the message was unmistakable: when the rules keep tightening and demand keeps falling, you stop throwing good money after bad.

The shutdown would be phased through 2025, with operations expected to fully cease by year-end. For years, California’s policy stack—its Low Carbon Fuel Standard, cap-and-trade, and aggressive EV mandates—had been eroding refining margins and raising compliance costs. At the same time, in-state crude production had been declining as permitting grew more restrictive. That left refiners in a brutal bind: less local supply, more constraints, and a market where long-term gasoline demand was expected to keep sliding. Phillips 66 said about 600 employees and 300 contractors would be affected. The politics got loud immediately, with Governor Newsom blaming corporate “greed.” Phillips 66’s reality was simpler: the business case no longer worked.

But even as it retreated from one part of California, Phillips 66 pushed forward in another. The symbol of that pivot was the Rodeo Renewable Energy Complex in the San Francisco Bay Area—an old petroleum refinery remade into a renewable fuels plant. The inputs changed from crude oil to used cooking oil, animal fats, greases, and vegetable oils. The hardware got repurposed too: equipment once designed for petroleum processing was reconfigured to handle biological feedstocks, and existing hydrogen, tanks, and logistics infrastructure found a second life.

Rodeo was positioned as a major renewable fuels facility, with capacity to produce renewable diesel and up to 150 million gallons per year of neat sustainable aviation fuel. And the buildout didn’t stop there. In 2025, a 30.2-megawatt solar facility—built with NextEra Energy Resources—began commercial operations. Phillips 66 said it would cut the complex’s grid power demand by about half and avoid roughly 33,000 metric tons of carbon emissions each year. Then, in November 2025, the company signed a sustainable aviation fuel deal with DHL Express—one of the largest SAF agreements by a U.S. producer. Rodeo did run at reduced rates during parts of 2025 because of market conditions, but the direction was clear: if California was going to force change, Phillips 66 was going to decide where it could win inside that change.

While California captured the headlines, the company’s biggest operational story was playing out in midstream. The DCP Midstream integration, completed in mid-2023, turned into a proof point for execution. Phillips 66 captured $500 million in synergies, beating its original $400 million target. Duplicate functions came out, commercial efforts were integrated, and the portfolio got optimized. The payoff showed up in 2024, with record NGL fractionation and LPG export volumes—exactly the kind of “move-molecules” performance the company had been building toward for a decade.

Then, in early 2025, Phillips 66 doubled down with the EPIC acquisition. For $2.2 billion in cash, it bought EPIC Y-Grade GP and EPIC Y-Grade LP—two fractionators near Corpus Christi with 170,000 barrels per day of capacity, an 885-mile NGL pipeline with 175,000 barrels per day of capacity, and about 350 miles of purity distribution pipelines. The logic was consistent with the whole Phillips 66 midstream thesis: connect fast-growing basins like the Delaware, Midland, and Eagle Ford to Gulf Coast fractionation and export. Expansion projects were already underway to lift pipeline capacity to 225,000 barrels per day by mid-2025 and ultimately to 350,000 barrels per day by late 2026. The deal closed in early April 2025, and the company expected it to be immediately accretive.

All of this was paired with relentless portfolio cleanup. Phillips 66 kept selling non-core assets, including its 25% interest in the Rockies Express Pipeline, which it sold to Tallgrass Energy for $1.275 billion. By 2024, the company had exceeded its $3 billion asset disposition target, with agreements generating $2.7 billion in proceeds—capital that could go toward buybacks and debt reduction. In parallel, a business transformation program drove $1.5 billion in run-rate savings, spanning automation, overhead reduction, contract renegotiations, and operational streamlining.

This period also marked a clear leadership handoff in tone. Greg Garland had been the operator-CEO who showed up on site and talked about reliability and execution. Mark Lashier—who had led CPChem and joined Phillips 66 as president and COO in April 2021—became CEO on July 1, 2022, and later chairman. Lashier, a chemical engineer with a doctorate from Iowa State University and 13 U.S. patents, leaned into strategy and capital allocation. On ESG, his stance was notably pragmatic: Phillips 66 focused on reducing emissions intensity and improving efficiency, backed by detailed sustainability reporting, without hanging the business on sweeping net-zero promises.

By 2025, Phillips 66 had made its approach to the energy transition legible. The company wasn’t pretending its legacy operations were disappearing overnight—they still generated most of the earnings. But it was adapting with the same discipline that made the spin-off work in the first place: exit assets that no longer clear the bar, repurpose the ones that can, and keep concentrating on infrastructure advantages where the economics are durable.

VIII. Financial Engineering & Capital Allocation

Phillips 66’s capital allocation story is, in many ways, the real sequel to the 2012 spin. In the early years, the job was credibility. Keep the plants running, fund the midstream build-out, expand chemicals, and prove the new company wasn’t just a volatile refiner with a famous logo. So cash stayed inside the business.

As those projects came online and started throwing off steady earnings, the posture changed. By the middle of the decade, Phillips 66 moved toward a more balanced approach—roughly 40% of capital to growth and about 60% back to shareholders. Then came the next pivot. From 2021 onward, with many of the big growth builds largely in place and energy transition uncertainty rising, the company increasingly treated itself like an elite “harvester”: keep spending disciplined, protect the balance sheet, and send cash back to owners.

The dividend arc tells that story cleanly. That inaugural $0.20 quarterly dividend in 2012 climbed to $1.15 by 2024, and to $1.20 per quarter by late 2025. The dividend increased every year—even through the demand collapse of 2020—while management kept the payout ratio conservative, roughly 35% to 40% of operating cash flow, leaving room for buybacks and flexibility in down cycles. By early 2026, the annual dividend was $4.80 per share, yielding around 3.3%.

Buybacks, though, became the signature move. From 2012 through 2024, Phillips 66 repurchased about $25 billion of stock, cutting the share count by roughly a third. And it didn’t treat repurchases like a metronome. When markets panicked in 2020 and PSX briefly fell to around $40, the company leaned in. When the stock pushed above $130 in 2024, it eased off. This was a board that acted like it actually believed valuation mattered. When shares offered double-digit free cash flow yields, buying them back often looked better than forcing new refining projects into a world that wasn’t paying for them.

The most vivid snapshot of that commitment came right after the leadership transition. From July 2022 through the end of 2024, Phillips 66 returned $12.5 billion to shareholders—roughly 40% of the company’s market cap during that stretch. The cadence continued through 2025, with dividends and buybacks sending hundreds of millions back to shareholders quarter after quarter. The stated goal was to return more than 50% of net operating cash flow to shareholders through 2027.

All of this only works if the balance sheet can handle the cycles, and Phillips 66 treated that as non-negotiable. It maintained investment-grade ratings from all three agencies—no small feat in a commodity-exposed business. It extended maturities when rates were low, avoided restrictive structures, and kept liquidity ample enough that when banking stress hit in 2023, the company didn’t need emergency financing. Looking ahead, the target through 2027 was to reduce total debt to around $17 billion.

On growth spending, the discipline was explicit. Projects had to clear a 15% unlevered return hurdle and survive stress tests built around bottom-cycle commodity assumptions. That filter kept the company from chasing headlines. The Sweeny fractionator expansion made sense and moved forward. A biodiesel plant that didn’t clear the bar didn’t.

Even the 2026 capital plan reflected that posture: about $2.4 billion total, split between roughly $1.1 billion of sustaining capital and $1.3 billion of growth capital, weighted heavily toward midstream expansion rather than high-risk downstream bets.

Asset sales rounded out the playbook. Phillips 66 didn’t sell to plug holes; it sold to upgrade the portfolio and fund returns without levering up. The Alliance Refinery, damaged by Hurricane Ida, was sold at a price reflecting land value plus environmental remediation funding. Other international assets were packaged and sold to infrastructure funds at premium multiples. Total proceeds from asset dispositions exceeded $3 billion, feeding the buyback-and-dividend machine while keeping the balance sheet intact.

You can see the whole framework in the 2024 results. Phillips 66 reported adjusted earnings of $2.6 billion, or $6.15 per share, on $4.2 billion of operating cash flow, with revenue of $145.5 billion. Included in the year was a $230 million pre-tax accelerated depreciation charge tied to the Los Angeles refinery closure—painful in the short term, but consistent with the company’s broader approach: face reality early, take the charge, and redeploy capital toward higher-return uses.

By early 2026, the market had largely rewarded the pattern. Phillips 66 traded at premium multiples to many refining peers, reflecting confidence in its capital allocation and its growing midstream backbone. The total return from 2012 through early 2026 exceeded 400%, beating the Energy Select Sector Index, with reinvested dividends pushing the outcome even higher. The “downstream orphan” had turned into something rarer: a cyclical business run with a deliberately non-cyclical owner’s mindset—and a track record of returning more cash to shareholders since the spin than its original market capitalization.

IX. The Four Business Segments Deep Dive

Refining: The Cash Engine Under Pressure

Step into the Wood River Refinery control room outside St. Louis and it feels like a cockpit. Dozens of screens stream live readings from thousands of sensors—temperatures, pressures, flow rates—tracking a 356,000 barrel-per-day complex that runs like a city-sized machine. On an average day, Wood River can turn enough crude into gasoline and diesel to keep huge swaths of the Midwest moving.

And that’s the paradox at the heart of Phillips 66 refining. These assets are engineering marvels, irreplaceable in a practical sense, and still hugely important to the economy. But they operate under a cloud: a growing political push to phase out fossil fuels, tougher environmental rules, and investors who increasingly treat refining as a sunset business.

Before the Los Angeles closure, Phillips 66 ran 13 refineries with more than 2 million barrels per day of capacity. They’re spread across the map—from Ferndale, Washington to Lake Charles, Louisiana—which helps cushion the blow of regional disruptions. Many are complex plants, not simple “topping” refineries. That complexity matters because it means they can process heavier, cheaper crude and still yield high-value products. Rebuilding this footprint from scratch would cost a fortune, which is why incumbents still have real advantages even as demand growth slows.

Execution is what separates good refiners from great ones. Phillips 66 pushed for high utilization—typically north of 95%, versus an industry norm closer to the low 90s. When you’re running assets this large, a little reliability goes a long way. The company also took real cost out of the system, stripping about $500 million in structural expense through automation, energy efficiency, and leaner overhead. In a business where margins can disappear fast, lower operating costs per barrel can be the difference between printing cash and treading water. In 2024, the refining segment hit a record clean product yield—more of the good stuff, per barrel, with less waste.

Then there’s what Phillips 66 calls its “advantaged crude” strategy—the never-ending puzzle of buying the right barrels. When the Brent-WTI spread is wide, inland refineries lean into discounted domestic crude. When that spread tightens, the slate shifts toward Canadian heavy or discounted sour barrels. By recent estimates, about three-quarters of Phillips 66 capacity can run advantaged crude. The trading organization and refinery schedulers work as one team, adjusting feedstocks as the market moves—sometimes week to week—to capture location and quality arbitrage.

Midstream: The Toll Road Empire

If refining is where Phillips 66 takes risk and earns big when conditions cooperate, midstream is where it tries to get paid for being essential.

This segment spans product transportation, terminaling, and processing, plus natural gas and NGL transportation, storage, fractionation, gathering, and processing. By early 2026, Phillips 66 operated and/or owned more than 22,000 miles of pipelines, along with major terminals and large-scale NGL infrastructure. The EPIC acquisition added exactly what the strategy has always wanted: more direct connectivity from growth basins to the Gulf Coast, plus room to expand.

The financial model is built around stability. Roughly 85% of midstream earnings are under fee-based contracts. So when commodity prices collapse—like they did in 2020—midstream tends to bend rather than break. Refining can get wiped out in a bad margin environment; midstream generally keeps collecting tolls. With DCP integrated, Phillips 66 touches the NGL chain end-to-end: gathering at the wellhead, processing, fractionation, storage, and export. In 2024, midstream adjusted earnings were $2.75 billion, with the segment running at roughly $4 billion in EBITDA and a target of $4.5 billion by 2027.

That priority shows up in capital allocation. The 2026 plan put $700 million toward midstream growth, more than any other segment. Key projects include Iron Mesa, a 300 million cubic feet per day gas processing plant in the Permian Basin expected to start up in the first quarter of 2027. And the Coastal Bend NGL pipeline expansion is designed to raise capacity to 350,000 barrels per day by late 2026. These are classic Phillips 66 moves: build infrastructure where volumes are growing, contract it, and turn it into long-lived cash flow.

Chemicals: The Steady Compounder

Chevron Phillips Chemical—CPChem—is one of those assets that doesn’t always get headline attention, but it’s foundational to the Phillips 66 story. It’s a 50–50 joint venture with Chevron, and it operates world-scale petrochemical facilities that turn cheap U.S. ethane into ethylene, the building block for plastics.

The advantage here is structural. Ethane from shale has often been dramatically cheaper than the naphtha feedstocks used by many overseas competitors, and CPChem’s cost edge versus naphtha-based Asian production can run as high as 70%. That’s not a clever trick. It’s geology.

Demand helps too. Global plastics consumption has historically grown about 3% to 4% per year, driven by packaging, construction, and consumer goods—especially in emerging markets. CPChem is building two world-scale projects expected to come online in late 2026, adding capacity into that demand backdrop.

For Phillips 66, the beauty is diversification and structure. CPChem earnings don’t move in lockstep with refining margins, and CPChem finances its own growth—so Phillips 66 isn’t writing the capex checks directly, yet it still captures 50% of the profits.

Marketing & Specialties: The Hidden Gem

Phillips 66 may be known for refining and pipes, but it still touches consumers through about 7,500 branded outlets across the U.S. The key point, though, is that retail gasoline itself is a thin-margin business. The value is in the ecosystem around it—branded relationships, convenience economics, and a set of specialty products that quietly throw off strong returns.

The specialties portfolio is the definition of unglamorous and lucrative. Phillips 66 is one of the world’s largest producers of needle coke, used to make electrodes for electric arc furnaces in steelmaking. It makes flow improvers that help crude move through pipelines. It also produces food-grade mineral oils used in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. These aren’t moonshots. They’re niche businesses with durable demand, strong margins, and relatively low capital intensity—hundreds of millions in annual EBITDA potential that many analysts barely model.

Together, these four segments explain why Phillips 66 has stayed so resilient. Refining brings the raw earning power, midstream brings toll-road stability, chemicals brings structural cost advantage, and marketing and specialties bring the underappreciated cash. The mix is the moat.

X. Playbook: Lessons from the Spin-off

When ConocoPhillips first floated the breakup, the reaction was cautious at best. To plenty of people, it looked like another downstream cast-off—refineries, pipes, and a famous logo, spun into a business everyone agreed was “cyclical” and “challenged.” More than a decade later, it’s hard to argue with the scorecard. From the 2012 spin through early 2026, Phillips 66 delivered more than a 400% total return, outperforming most energy peers and rewriting what “downstream” was supposed to look like.

The interesting part isn’t just that it worked. It’s why it worked. Phillips 66 followed a set of principles that show up again and again in great spin-offs—and they apply well beyond oil and gas.

When breakups create value. The separation proved a counterintuitive truth: sometimes the way to create value is to kill “synergies” that only exist on PowerPoint. Upstream and downstream had incompatible strategies, time horizons, and risk profiles. Inside one company, they fought over one capital budget. After the split, each business could be run on its own terms. ConocoPhillips became a focused exploration and production company. Phillips 66 stopped apologizing for being downstream and built a portfolio designed to win there. Within a few years, the combined value of the two companies was meaningfully higher than the pre-breakup whole.

The power of focus. Integrated oil companies love the story that the whole chain belongs together—secure crude supply, capture margin at every step, diversify risk. Phillips 66 showed how often those benefits are theoretical in practice. Once downstream reported to leaders who lived and breathed downstream, execution got sharper. Reliability and utilization improved because refining was no longer the “other” business. And when time-sensitive opportunities emerged—like the crude-by-rail and logistics shifts of the early shale years—Phillips 66 moved with the urgency of a company built for that moment, not a conglomerate trying to optimize across competing priorities.

Building moats in commodity businesses. Refining is a commodity business. That part is true. The mistake is assuming commodity means defenseless. Phillips 66 built advantages the way the best industrial companies do: by stacking edges. Location advantages near discounted crude. Operational excellence that lowered costs and lifted yields. Midstream assets that turned volatility into toll-like earnings. Brands and specialties products that quietly produced higher-margin cash flow. None of those is a magic shield on its own. Together, they made the business harder to compete with and more resilient through cycles.

Capital discipline in cyclical industries. The fastest way to destroy value in energy is to spend like a hero at the top and panic at the bottom. Phillips 66 tried to do the opposite: keep a steady hand, fund what must be funded, and treat growth capital like a privilege that has to clear real return hurdles. It protected the balance sheet so it didn’t become a forced seller or a forced borrower when the cycle turned. That discipline mattered in 2020, when demand collapsed and many companies had no choice but to slash investment and scramble for liquidity.

Managing regulatory headwinds. California became the hardest test of all: falling in-state production, rising compliance costs, and a policy environment that made the long-term outlook for traditional refining progressively worse. Phillips 66 didn’t pretend it could win a political war. It adapted where adaptation had a path to returns—like repurposing Rodeo for renewable fuels—and it exited where it didn’t, choosing to close the Los Angeles refinery rather than keep investing into a deteriorating equation. The lesson isn’t that regulation always wins. It’s that capital has to be honest about where it can earn a return.

Infrastructure over molecules. The midstream build-out might be the most durable strategic bet the company made. Production gets blamed. Refining gets regulated. But pipelines, terminals, storage, fractionation, and exports tend to remain essential—because the economy still needs molecules, even as the mix changes. Phillips 66 increasingly positioned itself as the connective tissue: the system that gathers, processes, and moves product. In industries facing disruption, owning the distribution and bottlenecks often holds up longer than owning the thing being disrupted.

XI. Bear vs. Bull Case & Competitive Analysis

The argument about Phillips 66 is really the argument about energy itself right now: is this a business built to outlast the transition, or a set of great assets slowly becoming obsolete? Both camps can make a serious case, and what ultimately matters—regulation, the pace of EV adoption, commodity cycles—is genuinely hard to forecast.

The Bull Case: Infrastructure Moat and Cash Machine. Bulls see Phillips 66 as a company positioned to be the “last one standing” in downstream. Even if U.S. gasoline demand falls sharply in aggressive EV scenarios, the refineries that survive should be the biggest, most complex, and best connected—because weaker plants tend to shut first. In that world, the survivors can actually see better industry economics.

The bigger claim, though, is midstream. You can’t easily recreate a national network of pipelines, terminals, storage, and fractionation today—permitting alone is a brick wall. Phillips 66’s system, spanning more than 22,000 miles of pipeline, is the kind of infrastructure that becomes more valuable as it becomes harder to build. And the NGL chain is a long-duration story: even in a more electrified future, the world still needs petrochemicals, and petrochemicals still need NGLs moving from shale basins to the Gulf Coast and beyond.

Layer on top what management has done with capital allocation—returning enormous cash to shareholders while keeping the balance sheet investment-grade—and you get the bull summary: a toll-road business bolted onto a refining platform that can still mint cash when the cycle cooperates. The dividend yield around 3.3% is part of that appeal, and bulls argue it’s well protected by free cash flow.

The Bear Case: Structural Decline and Stranded Assets. Bears look at the same asset base and see a clock, not a moat. They argue California isn’t an outlier—it’s a preview. As policy pressure spreads and vehicle fleets electrify, gasoline demand doesn’t just fluctuate; it trends down. In that view, refining is a business where “good years” are getting rarer, and where today’s cash generation risks masking tomorrow’s stranded costs.

They also point out that refining margins are cyclical and mean-reverting. The elevated crack spreads of 2021 to 2023 were boosted by unusual conditions—capacity rationalization and global disruptions—and could fade as markets normalize. Phillips 66’s 2024 adjusted earnings of $2.6 billion already showed the comedown from peak conditions. Add in a still-constrained ESG shareholder base and an industry that requires constant reinvestment just to stay safe and compliant, and the bear conclusion is blunt: this is a managed decline story that can look attractive—right up until it doesn’t.

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis. The structure of the industry cuts both ways. Barriers to entry are enormous: nobody is building new refineries in the developed world, and major greenfield pipelines are increasingly difficult to permit. That protects incumbents. Supplier power is moderate because crude is a global commodity with many sources. Buyer power is generally low for fuels but higher in petrochemicals, where large customers can negotiate aggressively.

The main swing factor is substitution. EVs substitute for gasoline. Renewables substitute for diesel. Recycling and alternative materials can substitute for some virgin plastics demand. The pace of substitution is what determines whether these assets have a few more turns of the cycle—or multiple decades of productive life. Rivalry remains intense, but there’s a more disciplined feel than in past eras, helped by consolidation and the reality that no one wants to destroy pricing in a business that already carries enough volatility.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Framework. Phillips 66 has several real, identifiable “powers,” even if none is a single silver bullet. Scale economies show up in both refining and midstream—bigger, more sophisticated systems can run at lower unit costs. Switching costs are meaningful in midstream: once producers and customers are connected to a system, moving off it is expensive and operationally painful. Network effects show up in the NGL chain as connectivity compounds—each new connection can make the whole system more useful to everyone on it. And process power is evident in the company’s focus on operational execution and reliability metrics that have often compared well versus peers.

On the other hand, the company doesn’t have perfect counter-positioning—competitors can pursue similar strategies—and it’s hard to argue it owns a single cornered resource that no one else can access. The defense is more about accumulation: several medium-strength advantages layered together.

Competitive Positioning. Against Valero, Phillips 66 has often traded at a premium EV/EBITDA—roughly 14x trailing versus Valero’s 9x in the snapshot cited—because investors are paying up for diversification and midstream stability. The tradeoff is that Valero is frequently viewed as the cleaner pure-play refiner, with strong Gulf Coast positioning and heavy-crude capabilities that can shine when discounted barrels are available.

Marathon Petroleum is the closest structural comp, combining refining with a major midstream arm (through MPLX), though the Speedway spinoff simplified its overall profile. In broad strokes, the market tends to place Valero at the top of the “refining operator” leaderboard, while Phillips 66 gets credit for building a more balanced earnings mix—less upside when refining is ripping, but more resilience when it isn’t.

Key Metrics to Watch. If you want a simple dashboard for how the story is going, two numbers do most of the work. First: midstream EBITDA growth. That’s where the “infrastructure moat” thesis lives, and the march from roughly $4 billion toward the $4.5 billion 2027 target is the clearest read on whether the strategy is compounding. Second: refining realized margins per barrel, net of operating costs. That’s the reality check—both on the commodity cycle and on execution. When margins stay healthy even in weak conditions, it supports the “high-quality survivor” argument. When they compress hard, the bear case stops sounding theoretical.

XII. Looking Forward: The Next Decade

Mark Lashier’s framework through 2027, laid out with the fourth-quarter 2024 results, was built on a kind of brutal realism. Phillips 66 wasn’t betting on a world where demand snaps back to the old trajectory. It was planning for a U.S. where gasoline demand keeps drifting down, diesel and jet fuel hold up better, and petrochemical feedstock demand stays firm. The mix of molecules changes, but the need for molecules doesn’t disappear.

Refining will keep shrinking into a tighter, more advantaged core. With the Los Angeles closure completed in 2025, what’s left is increasingly a portfolio of complex, well-connected facilities with access to discounted crude and pathways to export markets. The strategy isn’t to preserve every barrel of capacity for pride’s sake. It’s to run fewer assets better. If more capacity comes out over time, the company wants it to be deliberate—closing underperformers while investing in the plants that can be long-term survivors.

Midstream remains the growth engine. The 2026 plan puts most growth spending here: the Iron Mesa processing plant in the Permian, the Coastal Bend pipeline expansion, and the continuing integration and optimization of the EPIC assets. And the flywheel matters. CPChem’s two world-scale projects expected to come online in late 2026 should increase demand for NGLs and related logistics, which in turn makes the pipes, fractionators, and export infrastructure more valuable. Chemicals feeds midstream. Midstream supports chemicals. That’s the kind of internal reinforcement Phillips 66 has been trying to build since the shale boom began.

Renewables, meanwhile, stay in their box: meaningful, opportunistic, but not the entire story. Rodeo produces renewable diesel and SAF, and the DHL Express agreement is a signal that real customers are willing to sign real contracts. But management has been explicit about the economics. Renewable diesel margins can hinge on policy incentives, and Phillips 66 intends to participate where the math works—without staking the company’s future on subsidy regimes it can’t control. The solar facility at Rodeo is the same mindset in physical form: cut costs and emissions where it’s economically rational, not because it makes for a good press release.

None of it works, though, without the capital allocation machine staying disciplined. The core priorities remain the same: return more than half of operating cash flow to shareholders, grow the dividend, and repurchase shares when the price makes sense. The roughly $2.4 billion 2026 capital budget is meant to signal restraint, not retreat—sustaining capital to keep the system safe and reliable, and growth capital concentrated in midstream. And every project still has to clear the same hurdle: a 15% return under stress-tested assumptions. Asset sales remain part of the toolkit too, funding shareholder returns without stretching the balance sheet.

Then there’s the endgame question hanging over all U.S. refining: consolidation. If demand declines gradually, the country won’t need the same number of refineries it has today. Phillips 66 has positioned itself to be one of the survivors—and potentially a consolidator when the right assets come available at the right price. With its balance sheet, operational track record, and midstream integration, it’s also the kind of company that could someday be viewed as an attractive target. In this industry, strength can invite both options.

So the forward-looking investment case is straightforward, if not flashy. Phillips 66 expects to generate substantial free cash flow over the next decade, send a large portion of it back to shareholders, manage refining through a slow decline, and keep growing midstream into a larger share of earnings. The company that debuted as a roughly $20.5 billion spin-off has become about a $55 billion enterprise—and it has already returned multiples of that original value to shareholders along the way. Whether the next decade repeats that kind of outperformance will depend on the pace of the energy transition, on execution, and on how durable America’s NGL advantage proves to be. What seems much less in doubt is the playbook: take assets the market calls “commodity,” build infrastructure advantage around them, and compound cash with discipline.

XIII. Recent Developments

Phillips 66’s fourth-quarter 2024 results put a number on what the company had been signaling all year: the easy part of the post-pandemic refining boom was over. Refining margins weakened, and the company also booked a $230 million accelerated depreciation charge tied to the Los Angeles refinery. The quarter ended with adjusted earnings of negative $61 million, or a loss of $0.15 per share. For the full year, adjusted earnings totaled $2.6 billion, coming in well below what analysts had expected. Even so, the business still generated $4.2 billion in operating cash flow—less than the prior couple of years, but enough to cover the capital program and keep shareholder returns moving.

In early 2025, the Los Angeles refinery entered a real wind-down, not a pause. Several units were idled first, with the rest scheduled to come down in stages through the year. Phillips 66 brought in Catellus Development Corporation and Deca Companies to evaluate what could come next for the roughly 650-acre footprint, a strong signal that the company was planning a permanent exit rather than keeping the facility in mothballs. And to blunt the obvious question—what happens to fuel supply?—Phillips 66 said it would continue supplying California by sourcing barrels from elsewhere in its system and from external markets.

On the midstream side, the company kept executing on the shale-era thesis. The EPIC NGL acquisition closed in early April 2025 for $2.2 billion, bringing with it a direct Permian-to-Gulf Coast pipeline connection and additional fractionation capacity. The first expansion, taking pipeline capacity up to 225,000 barrels per day, was completed by mid-2025. A second expansion, targeting 350,000 barrels per day, was sanctioned and was expected to be finished in the fourth quarter of 2026.

Rodeo continued to serve as the company’s most visible “energy transition” proof point. The solar facility developed with NextEra Energy Resources began commercial operations in 2025. Then, in November 2025, Phillips 66 announced a sustainable aviation fuel agreement with DHL Express—one of the largest SAF deals in the U.S. air cargo sector. At the same time, management kept its capital posture restrained: the 2026 capital budget was set at $2.4 billion, with the biggest growth weighting going to midstream.

Zooming out, the setup into 2026 looked like a blend of headwinds and tailwinds. Refining margins were normalizing. NGL volumes out of the Permian continued to grow. California’s regulatory squeeze remained a constant. And the next big potential catalyst sat in chemicals, with CPChem’s two world-scale projects expected to come online in late 2026.

By this point, the market was valuing Phillips 66 less like a pure refiner and more like the diversified infrastructure business it had spent a decade building. The stock traded around $143, with a market cap near $55 billion and a dividend yield of about 3.3%.

XIV. Key Resources

Phillips 66 Investor Relations — investor.phillips66.com — Quarterly earnings, annual reports, investor presentations, and strategy updates straight from the source.

ConocoPhillips 2012 Spin-off Documentation — SEC filings on the separation, including the Form 10 registration statement that lays out what moved into Phillips 66 and how the transaction was structured.

CPChem Joint Venture — chevronphillipschemical.com — Information on the 50–50 Chevron Phillips Chemical partnership, including operational and business updates.

DCP Midstream Integration — phillips66.com/midstream/dcp — Phillips 66’s overview of the 2023 DCP transaction, including integration progress and synergy capture.

Rodeo Renewable Energy Complex — phillips66.com/rodeo-renewable-energy-complex — Updates on the Rodeo conversion, renewable diesel and SAF plans, solar project, and feedstock approach.

EPIC NGL Acquisition — Phillips 66 January 2025 press release — The announcement and details behind the $2.2 billion EPIC transaction, plus the capacity expansion roadmap.

U.S. Energy Information Administration — eia.gov — The best public baseline for U.S. refining and NGL data: capacity, utilization, crack spreads, and production trends.

Phillips 66 Annual Sustainability Report — Phillips 66’s ESG reporting, including emissions metrics and stated environmental strategy.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music