PriceSmart: The Costco of Latin America

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture a warehouse the size of two football fields in the middle of San José, Costa Rica. Inside, a restaurant owner named Carlos pilots an oversized cart past pallets of imported olive oil, Chilean wine, and American power tools. He stops at a case of premium beef—cuts he’d expect to find at a Costco in Miami, except this is his hometown. And the price makes his menu work.

Carlos has been a PriceSmart member for fifteen years. He pays the annual fee without thinking, drives past other supermarkets to get here, and treats that little membership card like one of his most important business tools.

Versions of this scene play out every day across more than fifty PriceSmart warehouse clubs in a dozen countries and territories—Central America, the Caribbean, and Colombia. PriceSmart is a relatively small public company, with a market cap around two billion dollars, a rounding error next to Costco. But inside its footprint, it has something much rarer than size: it’s the default destination for value. In many of its markets, it got there first, built trust over decades, and earned renewal rates that stand comfortably next to the model that inspired it.

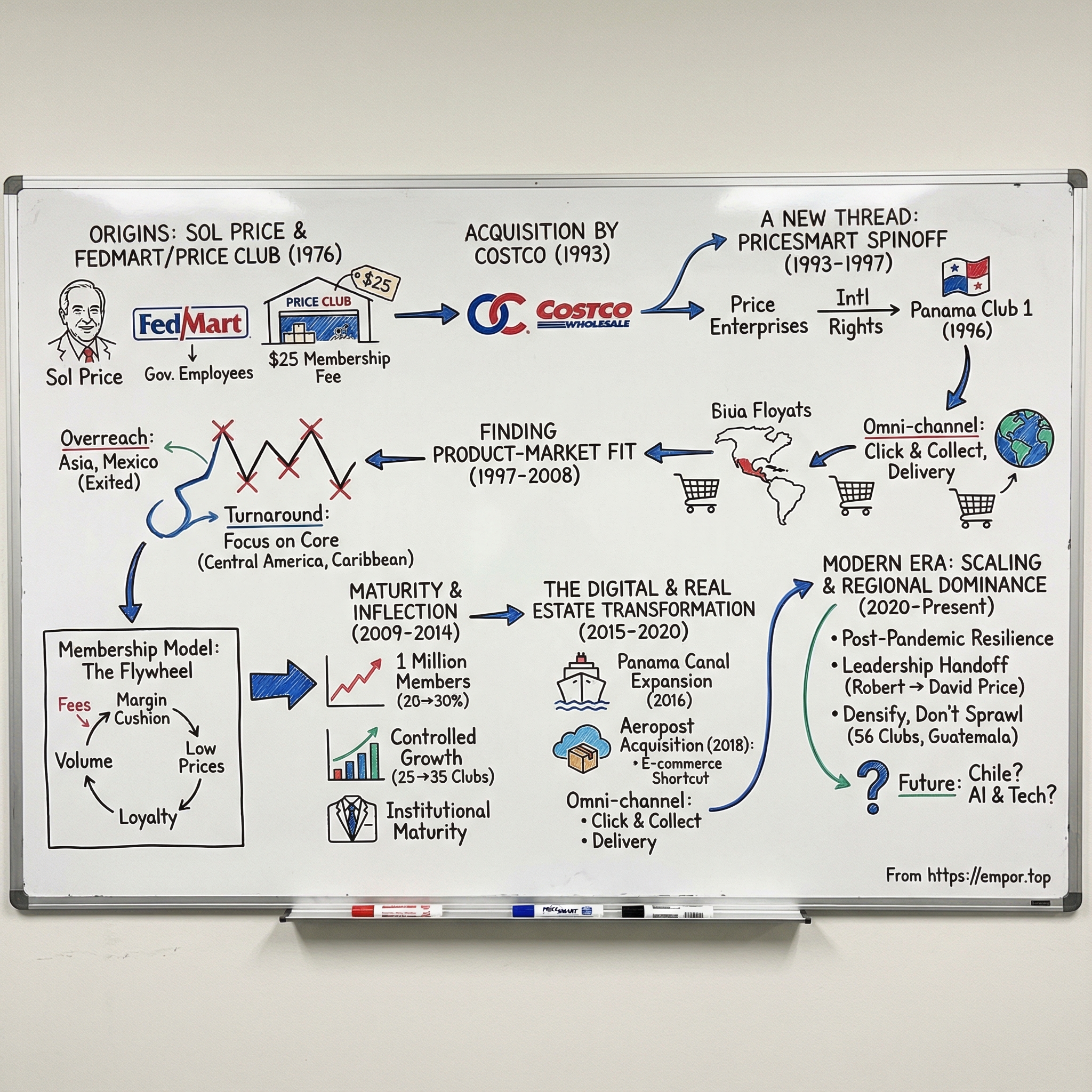

So here’s the deceptively simple question that drives this story: how did a scrappy spinoff from Price Club—the original membership warehouse pioneer—become the dominant warehouse retailer across some of the world’s messiest retail environments?

The answer runs through three big threads. The Price family’s founder DNA. A willingness to operate where global giants hesitated. And an almost obsessive commitment to adapting a proven format to places with different incomes, different infrastructure, different currencies, and very different day-to-day realities.

This story is worth telling because it’s a case study in how durable advantages get built. It shows the power of format replication—taking a model that works and translating it, not copying it. It shows why “boring” geographies can be incredible if you’re early and you’re right. And it shows how, in retail, hard-won operational knowledge compounds quietly until it becomes a moat.

Here’s our roadmap. We’ll start with Sol Price, the godfather of warehouse retail, and the philosophy behind Price Club. Then we’ll follow his son Robert through the post-merger moment when Price Club joined with Costco—and the international business needed a home. From there, we’ll watch PriceSmart learn, sometimes the hard way, what it takes to make the warehouse club model work in places like Guatemala, Panama, and Trinidad.

We’ll also cover the moments that turned this from a clever idea into an institution: the rise of professional management without losing the founding mindset, how logistics and supply chain evolved as global shipping changed, why the Panama Canal expansion mattered, and how COVID forced PriceSmart to get serious about digital.

Along the way, we’ll use a couple of lenses—Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers—to make sense of why this business has stayed hard to attack. We’ll build the bull case for PriceSmart as a long-term compounder, and the bear case for why emerging-market volatility can punish even great operators. And we’ll end with the handful of metrics that actually tell you whether this story is getting better or worse.

Now, let’s start where most great retail stories start: with the person who saw something everyone else missed.

II. The Sol Price Legacy & Price Club Origins

In the retail pantheon, Sol Price holds a strange kind of throne: adored by industry insiders, mostly unknown to everyone else, and still responsible for a format that changed how the world shops. One historian called him “the most influential retailer you’ve never heard of.” That’s not hype. It’s just that Sol wasn’t trying to be famous. He was trying to fix what felt broken.

He also wasn’t trained for retail at all. Sol Price was born in the Bronx in 1916 to Samuel and Bella Price, Jewish immigrants from Minsk, Belarus. His family moved to San Diego in the early 1920s. He graduated from San Diego High School in 1931, went to San Diego State, then earned a philosophy degree and a law degree at USC in the late 1930s. By the time he was building his career, he was an attorney in San Diego—about as far from “retail visionary” as you can get.

His pivot into commerce came through irritation and opportunity. In the early 1950s, Price was fed up with price-fixing and “fair-trade” rules that made discounting illegal. Around that time, clients asked him to visit Fedco, a membership store in Los Angeles. He came back to San Diego with a simple thought: this looks like the empty warehouse I have sitting around. So he turned that warehouse into a membership retail operation aimed at a group he could legally serve.

He called it Fed-Mart. Membership was restricted to federal, state, and local government employees. It started slowly, stocked with merchandise he sourced through his legal clients. Then he made a move that feels obvious now but was radical then: in 1954, he leaned into one-stop shopping with a discount department store model that charged a small membership fee—two dollars per family—to get in the door. FedMart worked. Over the next two decades it grew to 45 stores and more than $300 million in annual sales.

Then, in 1975, the floor dropped out. Price had sold FedMart to the German retailer Hugo Mann. He was 60 years old, and he found himself literally locked out of his office. Most people would take that as a sign to retire. Sol took it as an invitation to start over. That same year, he and his son Robert began building a new concept, funded by investments from family members and acquaintances.

Their starting point wasn’t a spreadsheet. It was listening. Sol and Robert spent time with small business owners and saw the same frustration again and again: they were getting crushed on the cost of supplies. They didn’t have leverage with vendors or shipping companies. Wholesalers didn’t want to serve them because the orders were too small and too scattered. The Prices saw a gap in the distribution system and an idea hiding inside it: what if small businesses could come buy wholesale merchandise themselves, in a single place designed for volume and efficiency?

That idea became Price Club.

The first location opened on July 12, 1976, in San Diego, in a former manufacturing building once owned by Howard Hughes. Sol and several friends put in $2.5 million to get it off the ground. The proposition was almost aggressively plain: pay a $25 annual membership fee, and in exchange you could buy bulk products at discount prices, in a no-frills warehouse.

And the brilliance was in how few moving parts it had. Price Club carried a relatively small selection across many categories. It sold in bulk. Markups were kept tight—often no more than about 10 percent over wholesale. The building was cheap industrial real estate. Merchandise sat on pallets right on the floor. Labor was minimal. There was essentially no advertising. The whole thing was engineered around one goal: take costs out so the member gets the savings.

It didn’t look like a sure thing at first. In its first year, the Price Company lost $750,000 on $16 million in sales. Then came a critical early lesson: membership breadth mattered as much as merchandise. A member suggested expanding beyond small businesses and letting government employees in. Sol raised more money from friends to keep the company going and widened eligibility further—credit unions, savings and loans, utility workers, hospital employees. That choice changed the trajectory. Suddenly the model had a much bigger base of paying members and predictable traffic to power the economics.

Underneath the operational choices was something deeper: a philosophy. Sol described his approach as “the professional fiduciary relationship between us (the retailer) and the member (the customer). We felt we were representing the customer. You had a duty to be very, very honest and fair with them and so we avoided sales and advertising.” In other words: the customer isn’t a target. They’re a client. You don’t “win” by extracting more from them—you win by protecting them.

That mindset didn’t just create loyalty. It created a flywheel. High volume plus low markups pushed Price Club to run extraordinarily tight operations. The volume, in turn, allowed the company to pay employees better wages and offer better benefits than typical retailers—another advantage that kept execution strong.

The format spread. Ultimately Price Club expanded to 94 locations across the United States, Canada, and Mexico. By 1992, it was doing $6.6 billion in revenue and $134.1 million in profit.

The shockwaves hit the entire industry. Sam Walton wrote in Made in America that he “borrowed as many ideas from Sol Price as from anybody else in the business.” He even said he liked the FedMart name so much it influenced “Wal-Mart.” Walton met with Price in 1983, and later that year the first Sam’s Club opened in Oklahoma City. A Goldman Sachs analyst, Stephen F. Mandel, Jr., called the warehouse club “the greatest revolution in retailing in the last 10 years.” And in short order, the concept spawned a new class of giants: Costco, Sam’s Club, and others.

By the early 1990s, though, the industry Sol had created was getting crowded. Sam’s Club had raced ahead, with 222 clubs by 1992. Other major players included Pace, Costco, Price Club, and BJ’s. Analysts were warning about saturation—especially on the West Coast, where the model had first taken hold.

That set the stage for consolidation. In 1993, Costco and Price Club agreed to merge. Price had declined an offer from Sam Walton to merge Price Club with Sam’s Club, and a Costco deal fit more naturally: similar size, similar model, similar culture. Together, the combined business operated 206 outlets, employed 38,000 people, and generated $15.3 billion in revenue that year. The new company was called PriceCostco, with leadership shared between Robert Price and Costco’s James Sinegal.

Then, just eight months later, a new thread split off: PriceCostco spun out a separate company called Price Enterprises, led by Robert. That move matters, because it created the bridge from Sol’s original invention to the international business that would eventually become PriceSmart.

The core DNA—member-first “fiduciary” thinking, operational discipline, value creation over value extraction, and unusually strong treatment of employees—proved durable enough to travel. Sinegal himself had learned retail climbing FedMart’s ladder, and later described Sol as a mentor who taught him to be tough and to carry a sense of social responsibility toward employees.

Sol, for his part, never seemed particularly sentimental about being the father of an entire industry. When asked what it felt like, he deadpanned: “I wish I’d worn a condom.” Classic Sol—humble, funny, and slightly profane.

But the joke hides the point. His legacy didn’t stop with Costco and Sam’s Club. One of the most interesting descendants of his thinking would be built far from the U.S., in markets most big retailers considered too risky, too small, or too complicated.

And the person positioned to do it was his son.

Robert Price had been at Sol’s side from the beginning. “My dad, his approach to things, was a very creative person,” Robert once said. “He had a great love for real estate, and he came to things in a very interesting way. My dad basically looked at things to see what was wrong with them so he could do it better.” That instinct—to look at a system, find the friction, and redesign it—would become essential as Robert stepped into the post-merger chaos and tried to build something new.

III. Birth of PriceSmart: The Spinoff Story (1993-1997)

The boardrooms of the newly merged PriceCostco in late 1993 didn’t feel like victory laps. They felt like truce talks. Two corporate cultures had been stitched together, two leadership teams were trying to share one steering wheel, and two strong-willed builders—Costco’s operational force James Sinegal and Price Club heir Robert Price—were now supposed to run as one.

It didn’t last. In less than a year, the arrangement cracked. The combined company was huge, with roughly $16 billion in wholesale club revenue, but it was trying to operate with two headquarters—Kirkland, Washington for Costco, and San Diego for Price Club. The dual-center-of-gravity setup satisfied no one. The merger had created scale, but not unity.

So the “divorce” came quickly. In 1994, Robert Price left the organization. What he walked away with wasn’t the crown jewel—North America stayed with the management team that would carry on as Costco. Price’s slice was different: control over commercial real estate operations and a set of rights tied to merchandising and membership club opportunities in certain international markets, including Australia, New Zealand, and Central America.

Those pieces were folded into a new vehicle—initially called Newco—that would ultimately become PriceSmart. In practical terms, Robert got two things. First, some shopping centers in California and Arizona that became Price Enterprises, a REIT. Second—and far more strategically interesting—the right to go build the warehouse club format outside Costco’s core territory.

That was the opening. If the U.S. was getting crowded, maybe the best place to apply Sol Price’s playbook was somewhere the giants were ignoring.

Latin America and the Caribbean fit the thesis. These were markets with growing middle classes and rising consumer expectations—and, crucially, no entrenched warehouse club competition. Walmart wasn’t focused there. Costco was busy consolidating North America. Carrefour dominated parts of South America’s bigger economies, but Central America and the Caribbean weren’t its priority.

PriceSmart’s first warehouse club opened in 1996 in Los Pueblos, Panama. The company kept its corporate headquarters in San Diego—where the warehouse club idea had been born—but it planted its flag abroad from day one.

Panama was a deliberate choice. A dollar-denominated economy reduced currency risk. The country’s role in global shipping offered logistical advantages. And its internationally oriented population—familiar with American brands and shopping patterns—made it a natural test market for the format.

In 1997, PriceSmart separated from its parent entities and became an independent publicly traded company, listing on NASDAQ under the ticker PSMT through an initial public offering. The spin involved assets contributed from Price Enterprises, which had earlier received international operations from Costco after the 1994 split.

To run the new company, the Prices tapped Gilbert Partida, who joined PriceSmart in December 1997. Like Sol Price, Partida was an attorney by training—and he also served as head of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce. In the early days, his execution looked sharp.

That same month Partida arrived, PriceSmart opened a second Panama club, on Vía Brasil. Together, the two locations generated $60 million in sales in 1998, hitting the high end of the Prices’ own projections.

No additional stores opened in 1998. But the following year, PriceSmart shifted gears. In 1999, it opened seven new warehouse outlets across Panama, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala—each launch a statement that the company wasn’t experimenting anymore. It was rolling out a chain.

Still, the skeptics had a real point. These were countries where annual GDP per capita sat in the low thousands to perhaps ten thousand dollars. Could the warehouse model—bulk buying, stocked-up pantries, and a paid membership—really translate? Would shoppers with far less disposable income be able to buy in volume? And even if demand existed, how do you run a tightly tuned retail machine in places with unreliable infrastructure, tough logistics, corruption, and political instability?

The early results in Panama delivered an unexpected answer: not only could the model work, in some ways it could work even better. Where traditional retail was fragmented and inefficient, PriceSmart’s promise—imported quality, consistent availability, and lower prices—stood out more sharply. The savings versus local supermarkets could be even wider than what U.S. Costco members were used to. And the membership fee, rather than being purely a hurdle, could function as a kind of middle-class badge—aspirational, identity-forming, and sticky.

But beneath the early momentum, problems were already forming. Expansion in these markets didn’t just demand ambition. It demanded operational excellence, local adaptation, and a management team built for complexity. PriceSmart was about to learn that the hard way.

IV. Finding Product-Market Fit in Emerging Markets (1997-2008)

PriceSmart’s first decade as a stand-alone company played out like a startup survival story—big swings, fast expansion, and a few mistakes that could’ve ended the whole experiment.

After the early momentum in Panama, the company pushed outward quickly. In 1997, two clubs opened through licensees in Indonesia and China. Then came the first real burst of owned-store growth: in 1999, PriceSmart opened seven clubs across Panama, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. On paper, it looked like the beginning of a regional land grab.

But building warehouse retail in emerging markets isn’t just “Costco, but south.” It’s logistics, customs, currency, local tastes, and a thousand operational details that will punish you if you’re sloppy.

And PriceSmart, at that stage, was sloppy—because it was still being run like a venture-backed concept, not a precision retail machine.

Gilbert Partida, the CEO brought in during the early days, hadn’t led a company before. He was a 35-year-old attorney with no retail background. As the business started to wobble, critics didn’t just blame “the markets.” They blamed leadership—either Partida for being out of his depth, or the Price family for putting him in the seat in the first place.

In a December 22, 2003 interview with Forbes, one analyst didn’t mince words about Partida: “He made a lot of ego-driven decisions that were terrible.”

The company kept expanding anyway. PriceSmart opened seven stores in 2000, and seven more in 2001. By the end of 2001 it had 23 stores across 11 countries, and annual sales had climbed to $489 million. That’s real growth. But underneath it, the engine wasn’t healthy. Profits were thin. Some decisions looked questionable. And the farther PriceSmart stretched, the more expensive every mistake became.

The Asia-Pacific efforts were especially painful. The Philippines, for example, generated early traction but never reached the scale needed to make the warehouse economics work. In markets where retail was already fragmented and competitive, PriceSmart couldn’t get big enough, fast enough, to justify the complexity.

Then came Mexico—an even clearer example of overreach.

In January 2002, PriceSmart entered a joint venture with Grupo Gigante, one of Mexico’s largest retailers, with plans to open four PriceSmart warehouse stores. Each partner agreed to contribute $20 million, for $40 million total. The ambition made sense: Mexico was huge compared to the Central American countries PriceSmart had been operating in.

But Mexico wasn’t an open runway. It was already a fight. Sam’s Club had been there for years. Costco was building. Local operators like Soriana and Comercial Mexicana understood the terrain. PriceSmart didn’t have first-mover advantage—it had late-mover headaches.

Eventually the company acknowledged it had bigger problems, too. PriceSmart announced it would restate financial results for 2002 and 2003. It settled an investor lawsuit. And it exited Mexico.

Robert Price later admitted the timing mistake in a February 13, 2005 interview with the San Diego Union-Tribune: “We were late (in entering Mexico) in terms of the number of operators. We were the last ones in and found it to be a challenging situation.”

In March 2005, PriceSmart settled the lawsuit filed by investors, agreeing to pay $2.35 million.

That combination—financial restatement, legal settlement, and retreat from Mexico—forced a reckoning. PriceSmart had expanded too fast, into markets it didn’t fully understand, without the operational discipline that made Price Club and Costco so formidable. Revenue growth was not the same thing as a working model.

The fix wasn’t a new brand campaign or a flashy strategy deck. It was adult supervision.

José Luis Laparte arrived with exactly the background PriceSmart lacked: deep warehouse-club experience and real operational chops. Before joining PriceSmart, he spent more than 14 years at Wal-Mart, working in Mexico and the United States in progressively responsible roles. He also held senior positions at Sam’s Club, including Vice President of Sam’s Club Mexico from April 2000 to September 2002, and Vice President of Sam’s International from October 2002 to September 2003. He joined PriceSmart in 2004, becoming President that year, and later served as President & CEO from July 2010 to November 2018.

Laparte’s arrival marked the shift from founder-era improvisation to professional retail execution. He understood what Sol Price and Jim Sinegal understood instinctively: this business lives or dies in the daily grind—buying right, moving product, controlling shrink, training teams, and giving members a reason to renew.

When the board later commented on his performance, Robert Price pointed to results that told the story. Under Laparte’s leadership as President, net warehouse sales more than doubled from $605 million in fiscal 2005 to over $1.3 billion in the most recent twelve-month period at the time. Operating income swung from a $5.4 million loss in fiscal 2004—just before Laparte joined—to $66.6 million for the twelve months ending May 31, 2010.

The turnaround wasn’t magic. It was focus. PriceSmart began exiting the places that didn’t work and doubling down on the places that did—its core markets in Central America and the Caribbean—where it could build local density, deepen vendor relationships, and actually compound operating knowledge instead of constantly relearning the basics.

Out of that messy first decade, PriceSmart also developed its lasting playbook: adapt the warehouse model to emerging-market realities instead of forcing a U.S. template onto countries that don’t live like the U.S.

The membership club model stayed recognizably “warehouse”—a curated assortment, value pricing, and a fee to enter the ecosystem—but the format changed. Stores were smaller, roughly 33,000 to 62,000 square feet, to match the size of the markets. Membership fees were lower, averaging about $35. And merchandising was tailored much more aggressively to local needs, serving both retail and wholesale customers.

That adaptation mattered. A typical Costco in the U.S. is a 150,000-square-foot fortress designed for suburban shoppers with big cars, big pantries, and room to store a month’s worth of paper towels. In much of Central America and the Caribbean, those assumptions break. Smaller clubs meant lower construction costs, better real estate flexibility, and a shopping experience that matched how members actually lived and moved.

The merchandise mix evolved the same way. PriceSmart learned when bulk made sense and when it didn’t. It leaned into locally sourced fresh foods where local suppliers were strong, while still using imports—supported through its Miami distribution center—for the branded and specialty items members couldn’t reliably find elsewhere.

By the mid-2000s, the company’s positioning had hardened into something powerful: PriceSmart would aim to be the membership warehouse champion in markets that were too small, too complex, or too “messy” for Costco and Walmart to prioritize. It wasn’t trying to beat giants on their favorite playing field. It was building a business in the places they were least willing to fight.

And once PriceSmart learned to execute, that choice stopped looking like a constraint—and started looking like a moat.

V. The Inflection Point: Going Public & Institutional Maturity (2009-2014)

The global financial crisis that began in 2008 tested every retailer on earth. For PriceSmart, it became something else: a proving ground. In markets where currency swings, political noise, and uneven growth were part of the weather report, the company had already been forced to build muscles that many U.S. retailers didn’t need. Now it got to show whether those muscles were real.

By 2008, PriceSmart had reached a milestone that’s easy to underestimate: operational stability in inherently unstable places. The business was still small, but it was working. In February 2008, net sales rose sharply versus the prior year, and the company was operating 25 warehouse clubs across 11 countries and one U.S. territory.

The financial picture told the same story in a cleaner way: the turnaround was sticking. EBITDA had climbed dramatically from the post-meltdown days of 2004, rising from about $7 million then to roughly $80 million for the last twelve months ended May 31, 2010. This wasn’t a concept anymore. It was an operating company.

By this point, PriceSmart started to earn a different kind of reputation—less “interesting emerging market experiment,” more “well-run, steadily growing retailer.” After the 2003–2004 restructuring, capital allocation got smarter, the pace of expansion became more deliberate, and execution improved. The early years had been marked by growing pains: profitability fell in 2003 and 2004 amid mismanagement and an expansion strategy that outran the company’s capabilities. The response was decisive. The Price family put in more equity, stepped in to stabilize leadership, and redirected the business toward a steadier, return-focused trajectory. From there, operations rebounded and the company began to deliver consistent growth with improving margins.

This era also completed the management transition the company needed. José Luis Laparte’s move into the CEO seat in 2010 put a seasoned warehouse-club operator fully in charge. Laparte, who served as President and CEO from 2010 to 2018, inherited a business that had survived its early crises—but still needed the day-in, day-out discipline that only deep retail experience can bring.

Internally, the mission was straightforward and very Sol Price: run U.S.-style membership warehouse clubs across Latin America and the Caribbean, sell high-quality goods and services at low prices, pay employees well with solid benefits, and generate a fair return for shareholders. The assortment blended U.S. brand-name items, private label, locally sourced products, and imports, serving both small businesses and everyday consumers in a warehouse format built around value.

From 2009 through 2014, the company leaned into controlled growth. Store count rose from around 25 to more than 35 locations. PriceSmart crossed the one-million-member milestone, a psychological threshold that mattered because it proved the membership model could achieve real scale in emerging markets—not just survive.

And just as important, this was when the company’s “adult” capital allocation habits set in. New clubs opened when the economics penciled out. Shareholders began to see modest dividends. Leverage stayed conservative, leaving room to absorb the inevitable currency shocks and political curveballs that come with the territory.

The crisis itself hit PriceSmart’s markets differently than it hit the United States. Many of the countries it served were tied closely to U.S. remittances and felt slowdowns, but not the same housing-led collapse that wrecked American retail. And as consumer budgets tightened, PriceSmart’s promise—buy better, pay less—did what it tends to do in rough times: it got stronger.

VI. The Digital & Real Estate Transformation (2015-2020)

In June 2016, a century-long engineering project finally clicked into place. The expanded Panama Canal opened, and suddenly a different class of cargo ship could move through it—vessels carrying as many as 14,000 containers, nearly triple the capacity of the old “Panamax” standard. For most of the world, this was a story about global trade routes. For PriceSmart, it was far more personal: a step-change improvement in how cheaply and reliably it could move goods from Miami, and from Asian manufacturing hubs, into the countries where it operated.

That mattered because, by this point, PriceSmart wasn’t just “a chain of clubs.” It was a supply chain spread across 11 countries, anchored by its global distribution center in Miami and supported by third-party logistics where that made more sense. The company kept investing in the plumbing—distribution, inbound freight, and inventory flow—because in emerging-market retail, those are often the real sources of advantage.

As CFO Michael McCleary put it to investors, opening distribution centers can mean “reduced … landing cost, reduction in lead time and improvement of working capital.” Said differently: get product into the country more efficiently, and you can lower prices, keep shelves full, and tie up less cash along the way.

While the physical network was getting stronger, PriceSmart also started taking digital seriously. And it didn’t do it the slow, committee-driven way. It bought a shortcut.

In March 2018, PriceSmart announced it had acquired Aeropost, an end-to-end cross-border package delivery service and online retailer headquartered in Miami. Aeropost was already one of the most visible cross-border logistics and e-commerce providers in Latin America and the Caribbean, with services spanning 38 countries and territories.

José Luis Laparte framed the logic clearly at the time: “Expanding on the strength of our brick and mortar clubs, the acquisition of Aeropost provides an opportunity to accelerate the development of an omni-channel shopping experience for our members.”

Aeropost brought exactly what PriceSmart needed: technology, management experience building e-commerce and logistics systems, and a working operating platform for cross-border delivery. Founded in Costa Rica, Aeropost had become a trusted layer between Latin American consumers and international shopping—helping customers buy with a fully landed price, local payment methods, and local delivery through Aeropost.com.

The key thing to understand is that Aeropost wasn’t just “an online store.” It was an on-ramp to capabilities PriceSmart could use across its entire business.

And then, in classic disciplined-operator fashion, PriceSmart treated the acquisition like a tool—not a trophy. By 2021, it announced the sale of Aeropost’s legacy cross-border casillero (package forwarding) and online marketplace businesses.

PriceSmart explained why: “The talent, technology and processes PriceSmart gained when we acquired Aeropost in 2018 have enabled us to launch our e-commerce platform, PriceSmart.com, accelerate online sales for curbside pick-up and delivery, generate online Member sign-ups, renewals and payments, and enhance our ability to better connect with and serve our Members. This sale allows us to consolidate resources and sharpen focus on our key strategies.”

The pattern is the point. Instead of trying to build e-commerce from scratch—or getting distracted running a separate, non-core marketplace—PriceSmart bought expertise, absorbed what it needed, and exited what it didn’t. Digital transformation, but with the same capital discipline it used to pick countries and open clubs.

At the same time, the company’s real estate strategy matured. PriceSmart developed a stronger bias toward owning, not just leasing, the most important sites—especially in markets where quality retail land is scarce and tends to appreciate. Site selection became more deliberate and more data-driven: high visibility, easy access, and locations that helped create density within a country, so each additional club made the whole network a little stronger.

Then COVID-19 arrived, and everything accelerated.

VII. The Modern Era: Scaling & Regional Dominance (2020-Present)

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, PriceSmart ran straight into the kind of complexity that can break retailers. It wasn’t just a demand shock. It was twelve different sets of government restrictions, supply chains snapping in real time, and consumer behavior changing faster than merchandising teams could react. For a business built on moving enormous volume smoothly and predictably, “smooth and predictable” suddenly disappeared.

That pressure also surfaced a familiar theme in the PriceSmart story: the push and pull between founder stewardship and professional management.

In December 2022, PriceSmart announced that CEO Sherry Bahrambeygui would resign, effective February 3, 2023. Robert Price, the founder and longtime Chairman of the Board, stepped back into the line of fire as Interim Chief Executive Officer.

Price wasn’t a symbolic figurehead. He had been Chairman since PriceSmart’s 1997 spin-off from Price Enterprises, and by February 2023 he was again running day-to-day operations. But he also made clear this wasn’t meant to be permanent. Announcing his plan to step down as Interim CEO, Price said: “As I approach my 83rd birthday in 2025, the time is right for me to transition from day-to-day duties and become Executive Chairman of the Board of Directors.”

That handoff became official in 2025. PriceSmart announced that Robert Price would step down as Interim CEO effective August 31, 2025. David Price—then the company’s Executive Vice President and Chief Transformation Officer, and a member of the Board—would become Chief Executive Officer effective September 1, 2025. Robert Price would move into the role of Executive Chairman.

David N. Price was elected to the Board in February 2022. He joined the company in July 2017, and as Chief Transformation Officer from August 2023 to August 2025, he led several of the areas most critical to the next phase of the business: Information Technology, PriceSmart.com, and Payment Solutions and Services.

All of this change happened while the operating results kept moving in the right direction. PriceSmart’s latest reporting puts trailing twelve-month revenue at $5.16 billion. Revenue grew from $4.52 billion in 2023 to $5.00 billion in 2024.

For the fiscal year ended August 31, 2024, total revenues rose 11.4% to $4.91 billion versus $4.41 billion the prior year. Net merchandise sales increased 11.2% to $4.78 billion from $4.30 billion, with constant-currency net merchandise sales up 8.6%.

The core of a membership retailer is whether existing clubs keep getting stronger, and here the trend was the same. Comparable net merchandise sales for the 51 warehouse clubs open more than 13½ calendar months increased 7.7% for the 52-week period ended September 1, 2024 compared to the prior-year period.

Expansion continued, but in the controlled, density-building way PriceSmart learned to prefer. The company operated 55 warehouse clubs in 12 countries and one U.S. territory: ten in Colombia; nine in Costa Rica; seven in Panama; six in Guatemala; five in the Dominican Republic; four each in Trinidad and El Salvador; three in Honduras; two each in Nicaragua and Jamaica; and one each in Aruba, Barbados, and the United States Virgin Islands. PriceSmart also planned to open a new club in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala in the summer of 2025, which would bring the total to 56.

And the company wasn’t just filling in the map—it was studying how to redraw it. PriceSmart said it continued to evaluate new markets, and specifically noted it was assessing Chile as a potential market for multiple clubs. It hired local consultants and began actively looking for sites, with the usual gating factors: securing appropriate locations for clubs and distribution facilities, completing market analysis, and receiving required permits.

Through fiscal 2025, the same themes—growth, but with currency reality always in the background—kept showing up in the numbers. In the third quarter of fiscal year 2025, total revenues increased 7.1% to $1.32 billion from $1.23 billion in the comparable period a year earlier. Net merchandise sales grew 8.0% to $1.29 billion from $1.19 billion, with constant-currency net merchandise sales up 9.5%. Foreign exchange moved the other direction, reducing net merchandise sales by $18.6 million, or 1.5%, versus the same quarter the prior year.

By May 31, 2025, PriceSmart had 55 clubs in operation, up from 54 a year earlier. Comparable net merchandise sales for the 54 clubs open more than 13½ calendar months increased 7.0% for the 13-week period ended June 1, 2025 compared to the prior-year period.

VIII. The Business Model Deep Dive

To understand why PriceSmart has held up in markets where retail is often a graveyard of broken promises, you have to look under the hood. At its core, it’s the classic warehouse-club machine—high-volume merchandise sold on razor-thin margins—adapted to emerging-market realities. And like Costco, the economic trick is that the real profit engine isn’t the stuff in the carts. It’s the small plastic card that gets you in the door.

PriceSmart generates most of its revenue from merchandise sales, but a meaningful chunk of its operating profit comes from membership fees. In fiscal year 2023, membership fees were about 1.5% of net merchandise sales, yet they represented 35.8% of operating income. That’s the model in one line: fees don’t move the top line much, but they create the margin cushion that lets PriceSmart keep markups low and still run a healthy business.

One of the biggest reinforcements to that equation is private label. PriceSmart’s Member’s Selection brand has become a real draw for members who want Costco-style value with products that fit local preferences. By Q3 FY25, Member’s Selection reached 27.7% of net merchandise sales—mix that generally improves margins, deepens loyalty, and gives PriceSmart something competitors can’t copy overnight.

Operationally, PriceSmart frames its execution around what it calls “The Six Rights”: the right merchandise, at the right time, right price, right place, right condition, and right quantity. It sounds simple—almost too simple—but in multi-country retail, “simple” is the point. The company has to do the basics extraordinarily well, every day, across very different environments.

Membership income has also been climbing steadily. From FY20 to the trailing twelve months ended February 29, 2024, membership fee income grew at a 6.3% CAGR. The company has been especially successful in expanding its premium Platinum tier, which increased at a 23% CAGR since FY20. That matters because premium members tend to be more loyal, shop more often, and anchor the renewal flywheel.

And that flywheel is very real here. Across its footprint, PriceSmart supported about $4.7 billion in trailing twelve-month revenue, served 1.86 million memberships, and posted an 88.3% renewal rate. That number deserves a pause. Costco’s global renewal rate is around 88%, and it’s about 91% in the U.S. The fact that PriceSmart can match Costco’s loyalty in countries with higher inflation, more currency volatility, and more political noise tells you the value proposition isn’t just attractive—it’s sticky.

On the merchandising side, PriceSmart runs a curated “treasure hunt” approach: a relatively limited assortment of high-quality items across categories, designed to drive volume and turn inventory quickly. That discipline—keeping choices tight, buying big, and moving product—helps protect the low-price promise for its 2.01 million membership accounts as of the end of fiscal year 2025.

Digital is now layered on top of the warehouse engine rather than competing with it. PriceSmart’s omni-channel offering includes online membership sign-up and management, click-and-collect, online-only items, and home delivery. The mobile app ties it together with product offers, digital membership cards, and order tracking. By February 28, 2025, 63.7% of members had created an online profile, helping drive digital sales growth of 19.8% year-over-year in Q3 FY25.

The important point isn’t that PriceSmart is “going digital.” It’s that the company has stayed profitable while building these capabilities—adding convenience without breaking the economics that make the membership model work.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

PriceSmart’s story isn’t just a retail history. It’s a playbook—one that keeps working precisely because it’s built on fundamentals, not fashion.

The first lesson is the power of format replication. PriceSmart didn’t invent the warehouse club. Sol Price already proved the model in the U.S.: charge a fee, run tight operations, keep markups low, and let volume do the heavy lifting. What PriceSmart proved is that a proven format can travel—sometimes with even more punch—when you bring it to markets where traditional retail is fragmented, inefficient, and expensive. When the baseline shopping experience is inconsistent and overpriced, “reliably good and reliably cheaper” stands out.

Second: first-mover advantages in “boring” geographies are real. While global retailers chased the biggest flags on the map—China, India, Brazil—PriceSmart built leadership in places that rarely make the shortlist. Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua: not glamorous, not huge, and not easy. But being early meant less direct competition, more time to earn trust, and the ability to build density country by country. Those markets didn’t just give PriceSmart room to grow. They gave it time to get good.

Third: operational excellence is the moat. Warehouse clubs look simple from the outside—big boxes, pallets, bulk packs. In reality, it’s a daily execution test. PriceSmart has to manage inventory across multiple currencies, work through import rules and customs regimes that differ by country, and protect quality—especially for perishables—in tropical climates where the supply chain doesn’t forgive mistakes. The hard part isn’t the idea. The hard part is doing it, consistently, across fifty-plus clubs. That accumulated know-how is the kind of advantage competitors can’t buy off the shelf.

Fourth: managing complexity gracefully beats trying to eliminate it. PriceSmart operates across countries with different political dynamics, regulatory systems, and consumer habits. The company’s edge has been knowing what must stay consistent—the membership value proposition, the discipline on costs, the focus on quality—and what must flex to local reality, from assortment to sourcing to store size.

Fifth: the membership flywheel is the engine. Once someone pays to join, they’re motivated to “get their money’s worth.” That changes behavior. It drives repeat trips, bigger baskets, and habit formation. And as the member base grows, PriceSmart buys with more leverage, sharpens prices, and reinforces the very value proposition that pulls in the next wave of members. It’s simple. It’s powerful. And it compounds.

Sixth: patient capital wins. PriceSmart has never been the kind of stock that thrives on hype. Its operating environments come with currency swings, political noise, and periodic economic stress. But for investors willing to sit through the turbulence, the underlying compounding—clubs getting denser, members getting stickier, operations getting better—has been the reward. The lesson isn’t that risk disappears. It’s that durability can still be mispriced when the story lives in places most people ignore.

Finally, PriceSmart shows what family business DNA can look like inside a public company. The Price family’s fingerprints—member-first thinking, fairness to employees, a bias toward honesty over gimmicks—still shape the culture decades after Sol. At the same time, the company learned it couldn’t run on legacy alone. It professionalized, bringing in seasoned operators with deep warehouse-club experience. The result is rare: founder principles with professional execution.

X. Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers

To see why PriceSmart has been so hard to dislodge, it helps to step back from the story and run the company through two classic strategy lenses: Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW-MODERATE

On paper, retail looks easy to enter: rent a box, fill it with product, open the doors. Warehouse clubs are the opposite. You need big upfront capital, the right real estate, and a supply chain that can move volume at low cost. In PriceSmart’s markets, you also need regulatory and customs know-how, reliable local partners, and the ability to operate through currency swings and political curveballs. PriceSmart has a two-decade head start in most countries, and it has already secured many of the best sites and supplier relationships. The “moderate” part of the threat is simple: if a global heavyweight like Costco or Amazon ever decided these markets were suddenly worth prioritizing, they have the resources to make life uncomfortable.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

PriceSmart isn’t Costco-scale, but in many of its countries it’s one of the highest-volume, most reliable buyers around. That matters. Local suppliers benefit from steady demand and access to a modern distribution network; international suppliers get a channel into markets that can be tough to reach efficiently. At the same time, PriceSmart’s absolute size still caps its leverage with the biggest global brands. The company also reduces dependency risk by sourcing more than half of its merchandise from within the region, building depth with local vendors rather than relying on a single pipeline.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW

The membership fee changes the psychology. Once members pay, they’re naturally inclined to consolidate purchases at PriceSmart to “earn back” the fee. And in many markets, there simply isn’t another warehouse club offering the same mix of price, quality, and assortment. That said, members aren’t captive—supermarkets, hypermarkets, and e-commerce options still exist—so PriceSmart can’t push pricing around the way a true monopolist could.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

Consumers can always spend elsewhere: traditional retailers, informal markets, or online platforms like MercadoLibre and Amazon. But substitutes usually miss the bundle that makes PriceSmart special: consistent quality, sharp pricing, and a treasure-hunt shopping trip that reliably produces “I can’t get this anywhere else” items. And while e-commerce is growing fast, many parts of Latin America still wrestle with delivery reliability and infrastructure constraints—real friction that keeps the in-club experience valuable.

Competitive Rivalry: LOW

This is the cleanest part of the picture. In most of PriceSmart’s footprint, there’s no direct warehouse club competitor fighting for the same member with the same model. Sam’s Club shows up in some Central American markets through Walmart’s regional presence, but often not in a way that creates relentless, store-for-store warfare. Limited rivalry lets PriceSmart stay disciplined—especially on pricing—without the constant margin pressure that defines most retail categories.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

Scale Economics: STRONG

PriceSmart’s advantage isn’t global scale; it’s local scale. Within each country, as it adds clubs and builds density, it gets better purchasing terms, more efficient logistics, and lower per-unit distribution costs than local retailers can match. The Miami distribution center and regional facilities reinforce those economics, especially as the network becomes more tightly connected.

Network Effects: LIMITED

This isn’t a social network. One person joining doesn’t directly make the club more valuable to another person. The closest thing PriceSmart has to a network effect is density: more members justify more clubs, which improves convenience and accessibility, which can make the membership more attractive.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG

PriceSmart’s model is hard for traditional retailers to copy because it requires a different economic religion: low merchandise margins, high volume, and a business that’s structurally built around membership loyalty. Many incumbents can’t pivot without blowing up their own P&Ls. Meanwhile, global players have historically viewed these markets as too small or too complex to prioritize. As long as that strategic dismissal holds, PriceSmart keeps the field to itself.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

The membership fee creates a real, if modest, cost to walking away: members don’t want to waste something they’ve already paid for. On top of that, habits form—people learn the layout, the rhythms, the categories that deliver the best deals. But switching costs aren’t absolute. If members feel the value isn’t there, they can simply stop renewing.

Branding: MODERATE

In its markets, PriceSmart stands for something clear: value, quality, and trust. The membership card can carry a bit of status too—a marker of being part of a growing middle class. But the brand is largely regional; it doesn’t have the broader cultural gravity Costco has in the U.S., and it doesn’t automatically transfer to new countries without doing the work again.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

This is one of the quieter moats. Great retail sites are scarce, and PriceSmart has spent decades locking in high-visibility, high-access locations. It has also built vendor relationships that take years to develop. And then there’s the hardest-to-copy resource of all: institutional knowledge about operating warehouse clubs across emerging markets—how to navigate customs, infrastructure gaps, political churn, and currency complexity without breaking the member promise.

Process Power: MODERATE-STRONG

Warehouse clubs are execution businesses, and execution compounds. Training, inventory discipline, loss prevention, merchandising cadence—these processes get better through thousands of iterations. PriceSmart has been running that loop for decades, across environments that are less forgiving than the U.S. That embedded operational muscle is not something a competitor can replicate quickly, even with capital.

Which powers are strongest? PriceSmart’s most durable advantages come from scale economics at the country level, counter-positioning against both local incumbents and global giants, and cornered resources—especially real estate and hard-earned market know-how.

XI. Bear vs. Bull Case

Bull Case:

The bull case for PriceSmart is pretty straightforward: a proven membership machine, running in markets that still have a lot of empty map left.

First, the footprint is still small relative to the opportunity. PriceSmart operates fewer than 60 clubs across twelve countries with a combined population north of 100 million. If you believe the warehouse model creates real consumer surplus—and PriceSmart’s renewal rates suggest it does—then there’s plenty of runway just from densifying existing countries and entering a few new ones.

Second, this isn’t a “maybe it works” concept. PriceSmart has been running this play for decades, in places where operating conditions swing hard. It has lived through currency shocks, political noise, natural disasters, and a global pandemic, and it kept the core engine intact: members renew, clubs stay busy, and the company remains profitable.

Third, the early-mover advantage is real, and it compounds. In many of its markets, PriceSmart isn’t one of several warehouse clubs—it’s the warehouse club. Every new location adds density, improves logistics, strengthens supplier relationships, and makes the business harder to attack without committing serious capital and patience.

Fourth, digital is no longer theoretical. The fact that a large share of members have created online profiles, and that digital sales have been growing quickly, is a signal that the member relationship can extend beyond the four walls of the club. E-commerce, click-and-collect, and delivery don’t just add a channel—they add touchpoints that can keep the membership habit sticky.

Fifth, the balance sheet gives the company options. PriceSmart has been able to fund growth without stretching financially, while also paying dividends. In a region where volatility is part of the deal, that conservative posture is an asset.

Sixth, Chile—if it happens—would be the kind of step up investors have been waiting for. It’s a more developed economy than most of PriceSmart’s current markets, with a larger middle class, and management has said it could support multiple clubs. It’s not guaranteed, but it’s a meaningful source of optionality.

Seventh, there’s a narrative and valuation angle. PriceSmart trades at a discount to Costco despite sharing some of the most important characteristics—membership economics and loyalty—while still having a long expansion runway. If the market starts treating it less like an “emerging market curiosity” and more like a disciplined compounder, the multiple could move.

Put it all together and you get the big bullish punchline: a chain with about 56 clubs today could plausibly grow to 150+ over the next decade through a mix of densifying what it already owns and adding a few new countries.

Bear Case:

The bear case is equally real—and it mostly comes down to concentration risk in complicated places.

Start with currency and politics. PriceSmart operates across a patchwork of currencies, and periodic devaluations are not an edge case—they’re part of the operating environment. Political instability can also turn into direct business risk. In countries like Nicaragua, where the government has targeted foreign businesses, the downside isn’t “a bad quarter.” It can be asset impairment with limited recourse.

Next is the e-commerce drumbeat. PriceSmart has made real progress digitally, but it’s still a retailer with finite tech resources. Amazon’s capabilities are unmatched, and MercadoLibre keeps building logistics density across Latin America. As delivery reliability improves, some of the friction that still protects club-based retail starts to fade.

Geographic diversification is another constraint. PriceSmart’s footprint is a strength when things are stable—density, focus, local knowledge—but it also means a regional downturn can hit many clubs at once. There’s no U.S. or Europe segment to stabilize results if Central America slows.

Then there’s the investor base. PriceSmart’s relatively small market cap can limit institutional ownership. That doesn’t change the underlying business, but it can amplify stock volatility when sentiment turns.

Family influence is a double-edged sword. The Price family’s involvement helps preserve the culture and the member-first DNA. But it can also reduce strategic flexibility if management wants to pursue options that don’t align with family preferences, including potential strategic deals.

Macro shocks are simply more common here than in most developed-market retail stories. Commodity spikes, political disruptions, and natural disasters can hit costs, demand, and supply chains quickly—and not always predictably.

Finally, the secular headwind: store-based retail everywhere is being pressured by online shopping. PriceSmart’s markets may be behind the U.S. curve, but the direction of travel is the same. If younger consumers become more digital-first, the in-club “treasure hunt” dynamic that drives incremental basket size could weaken over time.

Key Metrics to Watch:

If you want to track whether the bull case is playing out—or the bear case is starting to bite—three metrics do most of the work:

-

Comparable net merchandise sales growth (constant currency): This strips out new clubs and FX noise to show whether the existing base is getting stronger. Steady mid-single-digit comps are a sign the value proposition is holding.

-

Membership renewal rate: This is the truth serum. Sustained renewals above the mid-80s mean members are still getting enough value to pay again. A consistent downward trend is an early warning signal of competition or execution slippage.

-

Private label penetration: Member’s Selection supports margins and differentiation. Rising penetration usually signals a healthier model: more loyalty, better economics, and a stronger reason to choose PriceSmart over substitutes.

XII. Epilogue & What's Next

As 2025 drew to a close, PriceSmart was back at a familiar moment in its history: a handoff at the top, with the operating machine still humming underneath.

David Price—third-generation Price family leadership in the warehouse club business—had stepped into the CEO role. Robert Price, who had returned as Interim CEO during the post-pandemic turbulence, shifted into Executive Chairman as he approached his 84th birthday. The arc is almost poetic: the company that began as a spinoff after a merger “divorce” was now navigating another transition, this time by design, not necessity.

Where does PriceSmart go from here? The clearest signal is on the map.

Chile sits at the center of the company’s next expansion ambition. PriceSmart has continued advancing plans to enter the country, which it has identified as a market that could support multiple warehouse clubs. It appointed a country general manager, hired local consultants, and entered into an executory agreement for a potential club site.

Chile would be different from almost everything PriceSmart has done before. It would be the company’s largest and most developed market—one with meaningfully higher purchasing power than Central America, and the kind of retail infrastructure that can make the day-to-day job less improvised. If PriceSmart’s model has always been about delivering “reliably good and reliably cheaper,” Chile offers a customer base that could translate that promise into higher fees and bigger baskets.

But it’s not empty territory. Costco entered Chile in 2022. And local incumbents like Cencosud already operate at scale. In other words: if Central America was a place where PriceSmart could build in relative peace, Chile would be a place where it has to win.

Back in its core markets, the playbook remains what it’s been at its best: densify, don’t sprawl. The company planned to open a new warehouse club in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala in the summer of 2025. Once it opened, PriceSmart would operate 56 clubs. Guatemala, in particular, shows the compounding logic of the model: six clubs already, a seventh on the way, and each one makes the next one easier—more brand familiarity, more buying volume, and more logistics leverage inside the country.

In the Caribbean, Jamaica offered a window into how PriceSmart keeps extending its footprint without trying to boil the ocean. The company received approval for the development of another property, and PriceSmart Inc was approved to construct a new office and commercial complex at 14 South Camp Road—another sign that it intended to keep building out its presence and infrastructure on the island.

All of this growth sits on top of the bigger question: what does PriceSmart become in the next era?

David Price’s background hints at the answer. Before becoming CEO, his responsibilities included Information Technology, PriceSmart.com, and Payment Solutions and Services. That matters, because the next phase of the warehouse club model—especially in markets where convenience is improving fast—probably depends on how well the company turns membership into a year-round relationship, not just a trip to the club. If Robert Price’s chapter was defined by learning where the model works and making it operationally durable, David Price’s chapter may be defined by layering digital and services on top without breaking the economics.

That leads straight into the AI and technology wave. PriceSmart already generates what modern retailers live on: data about what members buy, how inventory moves, and what changes when prices, assortment, or availability shift. Used well, machine learning could tighten forecasting, reduce waste, and improve in-stock rates. Used poorly, it becomes expensive distraction—especially for a company that will never outspend tech giants. For PriceSmart, the challenge will be the same as it has always been: borrow the right tools, keep the focus, and make sure the member—not the technology—stays at the center.

Then there’s the physical reality of where PriceSmart operates. Climate and sustainability aren’t abstract in Central America and the Caribbean. Hurricanes, flooding, and tropical storms are operational facts, not long-tail risks. Resilient supply chains and reliable distribution—especially through hubs in Miami and Panama—only get more important as climate volatility increases. And at the same time, expectations from consumers and investors keep rising around environmental responsibility, pushing companies to show progress, not just intentions.

So, what would Sol Price think if he walked a PriceSmart club today?

You can imagine him appreciating the parts that never changed: the obsession with value, the idea that the customer is a member to be protected, not a wallet to be mined. You can imagine him liking that the warehouse club format didn’t just become a U.S. phenomenon—it became a way to bring modern retail selection and pricing to markets that had been underserved. And you can imagine him smiling at the strange, very Sol Price irony that his off-color joke about the warehouse club industry’s proliferation ended up landing close to home: half a century later, his family was still building the format he created, in places he probably never pictured serving.

That’s the real closing note of the PriceSmart story. It looks boring from far away—steady expansion, careful capital allocation, a business built on pallets and membership renewals. But that’s exactly why it’s instructive. In a world addicted to disruption narratives, PriceSmart is a reminder that moats can be built the old-fashioned way: show up early, run the basics better than anyone else, treat customers fairly, and compound quietly in markets most competitors overlook.

The seeds Sol planted in a converted San Diego hangar kept growing—just not where anyone expected.

XIII. Resources for Further Learning

If you want to go deeper than the headline narrative, PriceSmart is the kind of company that reveals itself in the footnotes: how it thinks about currency, how it measures member behavior, and what it prioritizes when conditions get messy.

Essential Reading: - PriceSmart Annual Reports and 10-K Filings (2008-Present): Start here. The shareholder letters and MD&A sections are where management lays out what worked, what didn’t, and what they’re betting on next. You can find them on the SEC’s EDGAR database and on PriceSmart’s investor relations site. - "Sol Price: Retail Revolutionary and Social Innovator" by Robert E. Price: The most direct window into the philosophy behind the format—and why the member-first mentality isn’t just branding. - PriceSmart Investor Presentations: The clearest snapshots of the strategy in motion, including market-by-market color and initiative updates that don’t always make it into earnings headlines. - Latin America Retail Market Reports: Euromonitor, BMI Research, and similar providers help you zoom out—so you can see what’s “PriceSmart-specific” versus what’s just the macro reality of retail in these countries.

Conference Calls and Investor Events: - PriceSmart’s quarterly earnings calls, available on its investor relations website, are where you’ll hear the unfiltered version of the story: what’s driving comps, what’s happening with membership trends, and where foreign exchange is helping or hurting. - Retail industry conferences occasionally feature PriceSmart executives, and those appearances can offer unusually candid perspective on expansion plans and operational focus.

Competitive Context: - Costco annual reports and investor presentations are useful benchmarks for the membership model: renewal rates, fee economics, and how a warehouse club thinks about margin discipline. - Walmart and Sam’s Club reporting on Latin America can help you understand where competition is real, where it isn’t, and how differently global giants approach the region.

On-the-Ground Perspective: - Local business reporting from Panama, Costa Rica, Colombia, and other core markets will sometimes surface the details that corporate filings can’t: new site rumors, permitting timelines, community impact, and the texture of competition. - AACCLA (Association of American Chambers of Commerce in Latin America and the Caribbean) can provide broader context on trade, investment conditions, and the operating environment that shapes what’s possible in each country.

The PriceSmart story rewards deep study. It’s not flashy, and it’s not simple—but it is remarkably consistent: a proven format, adapted carefully, executed patiently, and strengthened over time by doing the basics better than anyone else. As Sol Price might have said: take a simple idea, and take it seriously.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music