Prothena Corporation plc: The Neuroscience Spin-Out That Bet on Protein Misfolding

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

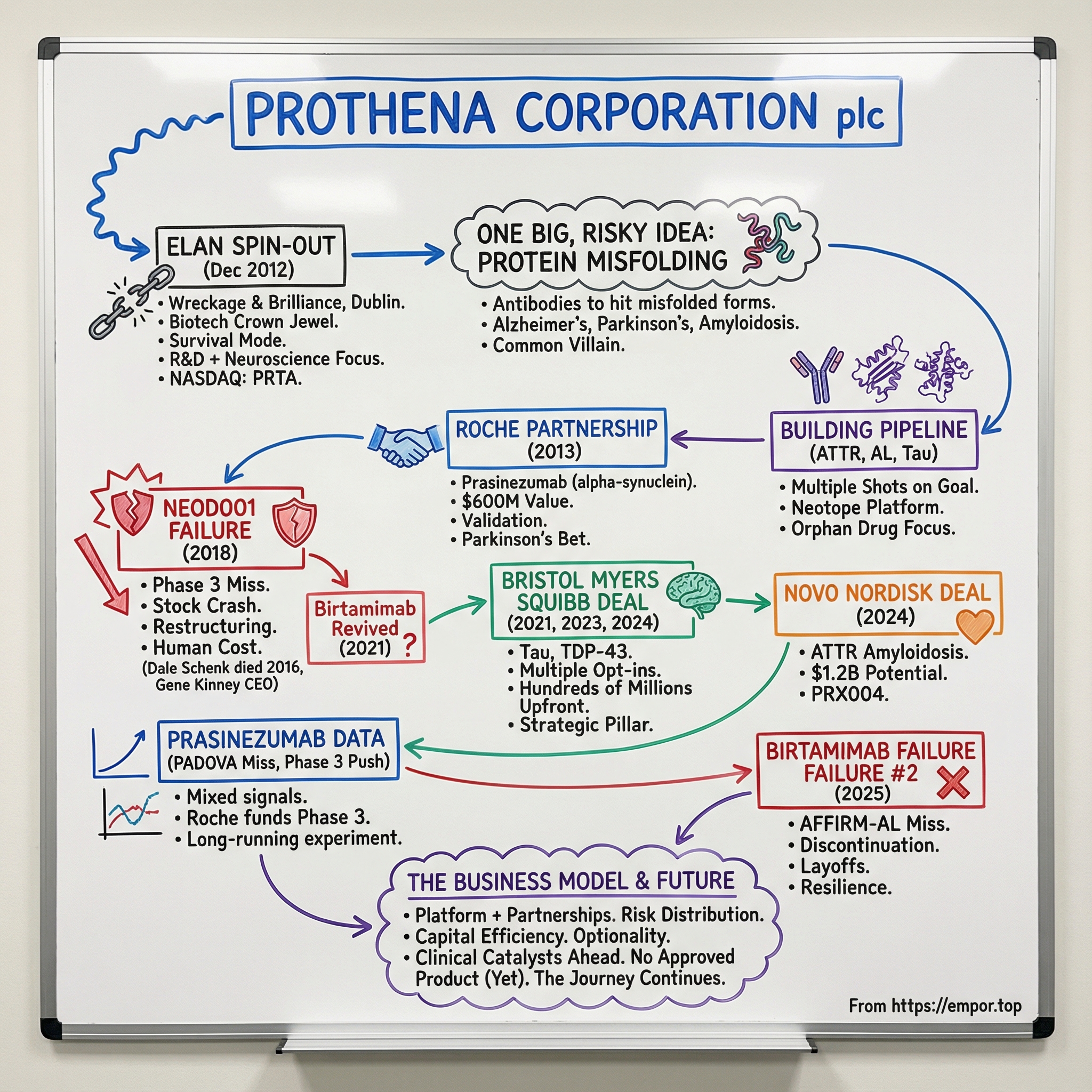

Picture this: December 2012, Dublin. Ireland is still feeling the aftershocks of the financial crisis, and Elan Corporation—once one of the country’s biotech crown jewels—is in survival mode, shedding pieces of itself like a ship tossing cargo in a storm. Out of that upheaval comes a new company: small, focused, and built around a single, risky conviction.

That company was Prothena Corporation plc.

Prothena was established in December 2012 when it separated from Elan, taking with it a substantial portion of Elan’s drug discovery platform. Soon after, its ordinary shares began trading on the NASDAQ Global Market under the symbol “PRTA” (and later on the NASDAQ Global Select Market).

Fast forward more than thirteen years, and Prothena sits in a fascinating, almost paradoxical place. On one hand, it has landed partnerships with pharmaceutical heavyweights like Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Novo Nordisk—deals that, on paper, reach into the billions in potential value. It has survived gut-punch clinical trial failures that erased huge chunks of market value overnight. And it has built a reputation for having one of the more sophisticated antibody platforms aimed at protein misfolding diseases. On the other hand, for all that progress, Prothena still has no approved product on the market.

So here’s the question that drives this story: How did a spin-out from a scandal-plagued Irish pharma company become a recognized player in one of medicine’s hardest frontiers—neurodegenerative disease research? And what does Prothena’s journey reveal about the brutal economics of drug development, the strategic role of partnerships, and the resilience it takes to survive biotech’s “valley of death”?

Because this isn’t just a story about one company. It’s also a story about a category of diseases that, in many ways, all rhyme. Alzheimer’s. Parkinson’s. Amyloidosis. Dozens of other conditions. Underneath the symptoms is a common villain: proteins that fold the wrong way, then stick together into toxic clumps that damage tissue and, eventually, destroy lives. Researchers have identified more than 35 proteins that can form amyloids under defined conditions, and many have been tied to disease. Prothena’s bet was that antibodies could be engineered not just to hit a target, but to recognize the specific misfolded shapes—the dangerous conformations—and help neutralize them.

The path has been anything but smooth. We’ll walk through the inflection points that defined Prothena’s trajectory: the Roche partnership in 2013 that electrified the market and validated its science; the NEOD001 collapse in 2018 that nearly broke the company; the Bristol Myers Squibb collaboration that signaled a comeback; and the more recent twists that forced Prothena to reshape itself yet again—even as its partners continued to push key programs forward.

What emerges is a story about persistence under pressure, disciplined dealmaking, and the central tension of biotech: you have to take enormous scientific risks, but you also have to stay alive long enough to be right.

II. The Elan Legacy: Understanding Where Prothena Came From

To understand Prothena, you first have to understand Elan. And Elan’s story reads like a very Irish mix of ambition, real scientific promise, and a collapse so public it left a scar on the whole country’s biotech identity.

Elan Corporation plc was a major pharmaceutical company headquartered in Dublin, with major interests in the United States. It was founded in 1969 by American businessman Don Panoz. What began in a Dublin garden shed expanded over the next three decades into a corporate giant. By 2001—at the top of its boom—Elan’s market value had climbed past $22 billion. It wasn’t just big. It was, by market cap, Ireland’s largest corporation, representing roughly one-fifth of the entire Irish Stock Exchange.

One company. Twenty percent of the market. Elan wasn’t merely a success story; it was a national symbol of Ireland’s shift from an agricultural economy to a modern, high-tech one.

The strategy that got Elan there was aggressive on multiple fronts. It went on a buying spree through the end of the 1990s and into the early 2000s, acquiring a large number of companies. At the same time, it stitched together a web of strategic partnerships—taking minority stakes in other companies that then paid Elan licensing fees for its technology. But that structure had a darker side: it let Elan report what were essentially research and development costs as revenue. And in 2002, that approach helped trigger the crash.

The unraveling came fast. As described in Pierce (2003), a Wall Street Journal article published on 30 January 2002 put Elan’s accounting methods under a harsh spotlight—especially painful given the mood of the time. Enron had collapsed only months earlier, and the era of “trust us” accounting was over. Regulators were suddenly looking everywhere. Three months after Enron’s fall, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) showed up at Elan’s door.

The SEC charged Elan with violating antifraud provisions of federal securities laws, alleging the company failed to disclose material information about its financial results in periodic filings and quarterly earnings releases distributed to US investors. According to the complaint, in 2000 and 2001 Elan told the public it was generating record revenue, net income, and operating cash flow from drug sales and licensing. It also said it was making meaningful progress toward becoming a fully integrated pharmaceutical company—with a goal of $5 billion in annual revenue by 2005.

The SEC’s view was that those claims were propped up by complex transactions designed to inflate results. In June 2002, Elan facilitated what the SEC described as an artificial sale of certain joint-venture-related securities between an off-balance-sheet subsidiary and an ostensibly independent third party, in an effort to preserve favorable accounting treatment. The problem, according to the SEC, was that the “unaffiliated third party” wasn’t truly unaffiliated—Elan had created it.

When the market learned Elan was under SEC investigation, the stock collapsed. Elan’s market value fell from that $22 billion peak to less than $800 million by 2002. And the timing was brutal: the company also faced debt payments of more than $2 billion before the end of 2004.

As if the financial crisis weren’t enough, Elan also suffered a separate scientific catastrophe—one that hit even harder because it involved the product that was supposed to secure the company’s future.

Tysabri, its blockbuster multiple sclerosis drug developed with Biogen, ran into serious safety problems. Natalizumab was approved for medical use in the United States in 2004, then later withdrawn after it was linked to three cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a rare neurological condition, when administered in combination with interferon beta-1a. On the day of the suspension announcement, Elan’s stock plunged 70% and Biogen’s dropped 43%. Tysabri eventually returned to the market in 2006 under a restricted distribution program, but the PML issue continued to shadow it for years.

Elan tried to stabilize. A new executive team came in, led by Garo Armen as chairman, later joined by Kelly Martin as CEO. They launched a recovery plan meant to restore shareholder confidence and simplify the organization.

But here’s the part that matters for Prothena: even amid scandal, debt, and a bruised flagship product, Elan still had something real—deep scientific expertise and a drug discovery platform focused on neurodegenerative disease. In neurology, Elan built on its research in neuropathologies like Alzheimer’s, and it studied other diseases such as Parkinson’s. Elan, in collaboration with Wyeth, ran a Phase III clinical trial of bapineuzumab, an experimental humanized monoclonal antibody intended as an immunotherapeutic treatment for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease.

By 2012, Elan’s management decided the best way forward was separation: split the drug discovery operation from the commercial business. The belief was that two focused companies would be worth more apart than together. The spin-out would become a pure early-stage R&D company, while Elan kept the Tysabri revenue stream.

And that’s the real inheritance Prothena received. Not a clean balance sheet—Elan didn’t have one. Not a pristine reputation—Elan definitely didn’t have that either. Prothena inherited the intellectual and technical core: scientists shaped by years of neuroscience work, antibody engineering capabilities, and hard-won knowledge about protein misfolding. The difference was that Prothena would try to carry that legacy forward without carrying the baggage that nearly sank the parent.

III. The Birth of Prothena: A Clean Break (2012)

In December 2012, the separation became official. Elan completed the spin-off of a substantial portion of its drug discovery business into a new, independent, publicly traded company: Prothena Corporation plc.

The mechanics mattered, because they signaled what this was meant to be: a real break, not a side project. Under the terms of the demerger, Elan shareholders on the register as of December 14, 2012 received one Prothena ordinary share for every 41 Elan ordinary shares or ADSs they held. Separately, a wholly owned Elan subsidiary subscribed $26 million and received Prothena shares representing 18% of Prothena’s total outstanding ordinary shares.

Prothena launched with a lean footprint—about 80 employees—but with serious scientific pedigree. Lars Ekman took the role of chairman, and Dale Schenk became chief executive officer.

Schenk, in particular, was a cornerstone of the early story. Before Prothena, he’d been Elan’s executive vice president and chief scientific officer, setting scientific direction across the R&D portfolio. He was also closely associated with some of Elan’s most visible Alzheimer’s work, including an experimental vaccine effort that helped earn him the Potamkin Prize from the American Academy of Neurology—an unusually big deal for someone in industry, in a world where awards like that typically go to academics.

His motivation wasn’t abstract. He’d seen Alzheimer’s up close when he was young—his grandmother, and others in his community—and that experience pulled him toward science even though he could have pursued music professionally. And when Alzheimer’s research began picking up momentum at Athena Neurosciences in the early 1990s, Schenk’s team leaned into ideas that didn’t sound “safe” at the time. There were few workable animal models, and even fewer people willing to bet on immunotherapy as a way to treat a neurodegenerative disease. They bet anyway.

That mindset carried directly into what Prothena inherited: the Neotope platform, a proprietary approach to generating antibodies designed to recognize the disease-causing conformations of misfolded proteins, not just the proteins in their normal forms. Prothena positioned itself as a discovery-and-development company aiming to build novel antibody therapies for diseases involving protein misfolding or cell adhesion—while continuing to emphasize differentiated science, intellectual property creation, and the ability to translate research into clinical-stage assets.

The opportunity set was wide from day one. The company described potential applications across AL and AA amyloidosis, Parkinson’s disease and related synucleinopathies, and even cell adhesion targets implicated in autoimmune disease and metastatic cancers.

Elan’s rationale for doing the deal was, on paper, clean and logical: two focused companies would be better than one sprawling one. The separation was framed as a way to give both Elan and Prothena tighter strategic focus, more direct access to capital, clearer investor choice, and better management incentive structures.

Operationally, Prothena’s research base remained in South San Francisco, even as it incorporated in Ireland. Elan itself had been streamlining—selling down manufacturing assets, reducing debt, and winding down what had once been a substantial R&D presence in the same South San Francisco corridor. Prothena, in other words, kept the scientific engine where the talent was, while keeping corporate continuity with Elan through Irish incorporation and its tax advantages.

Still, the market’s initial reaction wasn’t unbridled excitement. Another early-stage neuroscience biotech, with no approved products, coming out of a parent company with a complicated history, in one of the highest-failure-rate corners of drug development—skepticism was the rational default. But Prothena’s founders believed they weren’t just launching a single program. They were launching a platform—and if they could prove it even once, it could echo across multiple diseases.

They wouldn’t have to wait long for that first proof point.

IV. The Science Bet: Why Protein Misfolding Matters

To appreciate what Prothena was trying to do, you have to buy into the biological story it was betting on. It starts with a deceptively simple question: proteins are supposed to fold into precise three-dimensional shapes in order to do their jobs—so what happens when they fold the wrong way?

In many neurodegenerative diseases, the answer looks eerily similar: misfolded proteins start sticking to one another. Small clumps grow into larger aggregates. Over time, those aggregates pile up in the brain and other tissues, correlating with the slow, relentless loss of neurons and function.

You can see the pattern across the biggest names in neurology. In Alzheimer’s, two misfolded proteins dominate the pathology: beta-amyloid and tau. In Parkinson’s, the signature is alpha-synuclein accumulating in the brain. Huntington’s has huntingtin. Different proteins, different diseases—but a shared failure mode: misfold, aggregate, accumulate.

Neuropathological and genetic evidence, plus decades of work in transgenic animal models, have supported the idea that this isn’t just a byproduct of disease. The misfolding and aggregation of an underlying protein can be central to what drives the damage. Structural studies have added an important detail: the process often involves a major rearrangement of the protein into cross-β, amyloid-like fibrils—what looks like a common end point for aggregation across many of these disorders.

This is where Prothena’s thesis gets its appeal. If multiple devastating diseases “rhyme” at the level of protein misfolding, then maybe you don’t need a totally different therapeutic playbook for each one. Maybe you can go after a shared mechanism: toxic aggregates that disrupt cellular function, impair neuronal communication, trigger inflammation, and ultimately contribute to cell death and brain atrophy. These deposits can show up in multiple cellular compartments—inside the nucleus or cytoplasm, on membranes, and even outside cells. Despite the fact that beta-amyloid, tau, and alpha-synuclein differ in size, structure, and normal function, the arc from misfolding to aggregation follows strikingly similar rules.

The hard part—and the part Prothena built its identity around—was specificity. The Neotope platform’s key promise was the ability to generate antibodies that could tell the difference between a normal, properly folded protein and its pathological, misfolded counterpart. That is not a trivial distinction. The misfolded species can be a small fraction of the total protein in the body, and they don’t come in just one form. They can exist as small oligomers, larger assemblies, and fibrils—multiple conformations, potentially with different levels of toxicity.

This is also why Prothena’s approach was contrarian in 2012. The amyloid hypothesis in Alzheimer’s was under sustained attack after multiple clinical trial failures targeting amyloid-beta. Elan itself had lived that pain with bapineuzumab, helping fuel skepticism that antibodies could meaningfully change the course of neurodegeneration.

Prothena’s counterargument wasn’t that the field was wrong to be frustrated—it was that the field might have been aiming at the wrong thing. Maybe the problem wasn’t “amyloid” in the broad sense. Maybe it was precision: whether a drug was binding to the truly toxic species, like certain oligomers and disease-relevant conformations, rather than simply attaching to abundant, less relevant forms or late-stage deposits. Neotope was designed to generate antibodies against disease-relevant epitopes that appear specifically on misfolded proteins.

Zooming out, the scientific backdrop was evolving in the same direction. Researchers were building a clearer picture of amyloid fibrils and their oligomeric precursors, how aggregates form and proliferate, and how cells try to fight back through a proteostasis network that can fail under certain conditions. The hope was that better structural understanding would translate into better therapeutic strategies—ones that could prevent aggregation, neutralize toxic species, or slow the chain reaction that leads to dysfunction.

With that as the foundation, Prothena’s early target list wasn’t random—it was a statement of intent. Alpha-synuclein for Parkinson’s disease, a target that was far from clinically validated at the time. Amyloid light chains for AL amyloidosis. Transthyretin for ATTR amyloidosis. Different proteins and different commercial markets, but all tied together by the same underlying mechanism: protein misfolding.

And the portfolio approach was the business strategy that matched the biology. In biotech, any single program can fail. Prothena needed multiple shots on goal—not just to increase the odds of success, but because if it could prove the platform worked once, it could potentially speed the next programs behind it.

They were about to test that idea in the most validating way possible: a big pharma partner betting real money on their science.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Roche Deal (2013)

Less than a year after becoming independent, Prothena landed the kind of partner that instantly changes how the market sees you. It wasn’t a quiet research collaboration. It was a statement: one of the world’s biggest pharma companies was willing to put real money behind Prothena’s bet on misfolded proteins.

In December 2013, Prothena and Roche entered into a worldwide collaboration to develop and commercialize antibodies that target alpha-synuclein, including prasinezumab. Roche bought into the potential of prasinezumab in a deal valued at up to $600 million, including a $45 million upfront payment.

The structure followed the classic biotech playbook, but for a young spin-out it still carried weight: an upfront check, development milestones, and royalties if the drug ever made it to market. Roche took on sole responsibility for developing and commercializing prasinezumab, and Prothena would be eligible for up to double-digit teen royalties on net sales.

Roche’s willingness to bet big on an unproven approach came down to the target. Alpha-synuclein is a protein that can misfold and build up in the brains of Parkinson’s patients. Those aggregates—Lewy bodies—are the pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease and related conditions. But at the time, no one had shown that going after those aggregates could actually slow the disease. That made it a moonshot: high risk, potentially transformative upside.

Prasinezumab was designed as an investigational monoclonal antibody that binds aggregated alpha-synuclein, with the goal of reducing neuronal toxicity. The theory was simple to say and brutal to prove: reduce the build-up, limit further accumulation and spreading between cells, and you might slow progression.

For Prothena, the value went far beyond the headline number. Roche brought credibility, funding, and the ability to run the long, expensive clinical trials that disease-modifying Parkinson’s programs demand. Just as importantly, the partnership let Prothena stay Prothena. Roche would carry this particular program forward, while Prothena kept its platform and continued building other shots on goal.

It also set a pattern that would define the company: partner the most capital-intensive bets with pharma, keep the platform, and preserve the option to develop other programs internally.

Wall Street got the message. On the announcement, Prothena’s stock jumped—because in biotech, validation is a currency of its own. In less than a year, the spin-out that many investors would’ve written off as “another neuroscience story” suddenly looked like a credible contender.

VI. Building the Pipeline: ATTR, AL, and the Amyloidosis Opportunity

While Roche took the lead on alpha-synuclein and Parkinson’s, Prothena didn’t sit still. In parallel, it pushed hard on proprietary programs in a different corner of protein misfolding disease: the amyloidoses.

Amyloidosis isn’t one disease so much as a family of them. The common thread is the same grim mechanism: proteins misfold, clump, and deposit in tissues—slowly choking organs that can’t afford the damage. Two forms became central to Prothena’s early identity: AL (amyloid light chain) amyloidosis and ATTR (transthyretin) amyloidosis.

AL amyloidosis is rare, but brutal. Abnormal plasma cells produce misfolded immunoglobulin light chains that deposit throughout the body, especially in the heart and kidneys, leading to progressive organ failure that can be fatal. Back then, treatment largely meant going after the source—killing the plasma cells—without a therapy designed to clear the amyloid already lodged in tissue.

That gap is what Prothena targeted with NEOD001, later renamed birtamimab. It was Prothena’s first wholly owned lead asset, built around a clean, intuitive hypothesis: even if chemotherapy stops the production line, the debris is still there. If an antibody could bind the deposits and help clear them, it might add meaningful benefit on top of standard therapy.

Prothena moved with urgency. It pursued orphan drug designations to secure regulatory advantages and, if the science worked out, market exclusivity. And early clinical signals gave the company reason to believe it might be onto something—patients appeared to show improvements in organ-function markers that were consistent with reducing amyloid burden.

At the same time, Prothena advanced work in ATTR amyloidosis, driven by misfolded transthyretin. ATTR comes in hereditary forms, caused by genetic mutations, and wild-type forms that are associated with aging. Its cardiac form, in particular, was becoming increasingly recognized as an underdiagnosed contributor to heart failure in older patients—meaning the commercial opportunity could be far larger than the label “rare disease” might suggest.

Inside the company, the mindset was practical and relentless: in biotech, speed matters, but only if it’s paired with rigor. You need to reach clinical proof-of-concept quickly enough to earn confidence, capital, and partners—because the science is expensive, and the clock is always ticking. The Roche partnership gave Prothena breathing room, and the company also raised additional capital through public offerings to keep its proprietary bets moving.

By 2016, Prothena looked like it was finding its rhythm. NEOD001 was marching toward late-stage trials. Prasinezumab was advancing under Roche. The platform felt validated, the pipeline was deepening, and the company’s ambition was no longer just to be a discovery shop—it was starting to look like a company that could eventually carry a product all the way to patients.

And then, the story took a sharp, human turn.

On September 30, 2016, Prothena’s co-founder, President, and CEO, Dr. Dale B. Schenk, died. For a young company built around a scientific thesis and the people willing to bet their careers on it, the loss landed heavily.

The board moved quickly to appoint a successor who could preserve continuity. “Gene is a well-known and highly respected biotechnology executive who is uniquely qualified to lead Prothena,” said Lars G. Ekman, MD, PhD, Chairman of Prothena’s Board of Directors. “He has worked closely with Dale for many years and leads an extremely experienced and talented team.”

Gene G. Kinney, PhD, became President and Chief Executive Officer in 2016. Before that, he served as Chief Operating Officer for part of 2016, and earlier as Chief Scientific Officer and Head of Research and Development from 2012 to 2016.

Kinney had worked alongside Schenk since 2009—first at Elan, then at Prothena after the 2012 spin-out. That continuity of leadership and scientific vision would matter, because the challenges ahead wouldn’t be theoretical. They would be existential.

VII. Inflection Point #2: The NEOD001 Failure (2018)

By early 2018, Prothena was at the moment every biotech dreams about and fears in equal measure. NEOD001—its lead, wholly owned program—was in Phase 3. If it worked, Prothena wouldn’t just be a platform company with partnerships. It would have a path to becoming a commercial organization. Optimism had built for years, and the stock had climbed with it.

Then the data hit.

On April 23, 2018, Prothena announced it was discontinuing development of NEOD001, its investigational antibody for AL amyloidosis. The trigger was blunt: the Phase 2b PRONTO study missed both its primary and secondary endpoints. After seeing those results, Prothena asked the independent data monitoring committee for the Phase 3 VITAL study to review a futility analysis. The committee recommended stopping VITAL for futility. Prothena shut down the program entirely, including VITAL and the open-label extension studies.

The market reaction was instant and unforgiving. Prothena’s shares collapsed, falling roughly two-thirds in a single day.

Gene Kinney didn’t sugarcoat the human cost. “We are deeply disappointed by this outcome, particularly for patients suffering from this devastating disease,” he said. “We are surprised by the results from these two placebo-controlled studies and will continue to analyze the resulting data to share insights with our collaborators in the scientific, medical and advocacy communities.”

In biotech, the hardest part isn’t describing what happened. It’s explaining why a story that made so much sense can still end in a dead stop.

The post-mortem pointed to a few possibilities. The placebo arm performed better than expected—potentially reflecting improvements in standard-of-care chemotherapy that narrowed any incremental benefit an amyloid-clearing antibody might add. Patient selection may have been off, meaning the trials didn’t consistently enroll the people most likely to benefit. Or the core hypothesis—clear the deposits after you shut down production—may have been incomplete, flawed, or in need of sharper targeting and better endpoints.

Whatever the mix of reasons, the business consequences were immediate. Prothena moved into restructuring mode. It said it anticipated a 2018 net loss of about $80 to $85 million, including costs tied to closing NEOD001 and reorganizing the company. The workforce was expected to shrink to about 63 positions after transitioning employees involved in winding down the program—amounting to layoffs of roughly 57% of the company.

Kinney again emphasized the people behind the work: “We have an incredible team at Prothena and it is a privilege to work with these talented individuals who have dedicated their careers to advancing new treatments for patients with devastating diseases,” he said. “To our colleagues who are departing as part of this reorganization, I would like to express our sincere thanks for their many contributions.”

As often happens after a biotech blowup, the collapse also brought lawsuits. A class action was filed against Prothena and certain current and former executives on behalf of investors who bought the company’s stock during the relevant period.

But here’s the difference between a company that dies from a single failure and one that can keep going: Prothena wasn’t a one-asset story. The Roche partnership continued advancing prasinezumab in Parkinson’s. Other pipeline programs remained. And crucially, Prothena still had external partners willing to bet on its underlying science.

In fact, just weeks earlier, in March 2018, Prothena and Celgene had struck a collaboration worth up to $2 billion to develop new therapies across a broad range of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and ALS. The partnership was built around three proteins implicated in neurodegeneration, including tau.

The timing mattered. NEOD001’s failure was a crater. But the Celgene deal—announced right before the collapse—was proof that sophisticated buyers still saw value in Prothena’s platform. Even in disaster, the science hadn’t become worthless overnight.

VIII. Regrouping: The Roche Partnership Continues & New Targets Emerge

After NEOD001, Prothena had to do the hardest thing a biotech can do after a public failure: take a clear-eyed look at what it still had, and decide what it could realistically become. The company had taken a devastating hit, but it wasn’t finished.

One lifeline was already in motion. Prothena could point investors to its partnered Parkinson’s program with Roche—PRX002/RG7935, later known as prasinezumab—then in Phase 2 in the PASADENA study in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Prothena also kept advancing its broader slate of misfolded-protein targets, spanning Parkinson’s and other synucleinopathies, ATTR amyloidosis, and longer-term bets like tau, Aβ (amyloid beta), and TDP-43.

Prasinezumab mattered for more than optics. It was proof that the platform could produce a clinically viable candidate, even after NEOD001’s collapse. It was also a totally different kind of test: Parkinson’s instead of amyloidosis, alpha-synuclein instead of light chains, and a mechanism aimed at interrupting the spread of pathology rather than clearing deposits already entrenched in organs.

Internally, the NEOD001 experience also sharpened the development playbook. The next wave would need tighter patient selection, better biomarkers, and more thoughtful trial design. Because if Prothena had learned anything the hard way, it was that in neurodegeneration and rare disease alike, picking the wrong endpoints—or the wrong patients—can make a promising biology look like a dead end.

At the same time, the Celgene partnership announced in March 2018 became even more central to the survival story. The collaboration focused on three proteins implicated in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases, including tau—one of the key proteins implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. Prothena said it had identified antibodies that target novel epitopes on tau and could “block misfolded tau from binding to cells.”

That Celgene collaboration—later inherited by Bristol Myers Squibb after its acquisition of Celgene—brought both capital and a heavyweight partner to help prosecute hard CNS biology. Tau was especially compelling because it correlates more closely with cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease than amyloid-beta does. And by also taking on TDP-43, implicated in ALS and frontotemporal dementia, Prothena widened its reach beyond the Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s mainstream.

And then came one of the more unusual turns in this whole saga: Prothena eventually went back for the program it had buried.

In 2021, Prothena revived birtamimab after a post hoc analysis of the Phase 3 study linked the antibody to a significant improvement in all-cause mortality in a subset of high-risk patients. Prothena launched a new Phase 3 trial to confirm that survival signal.

“Following discontinuation of the VITAL study, we analyzed the results in order to contribute to the body of knowledge about AL amyloidosis with data from this first randomized, placebo-controlled Phase 3 study of an amyloid targeting agent on top of standard of care chemotherapy. These post hoc analyses suggest that in the category of patients at highest risk for early mortality, NEOD001 has the potential to provide a survival benefit on top of standard of care.”

It was a very biotech kind of move—equal parts stubborn and scientific. Sometimes you take the loss and walk away. And sometimes you dig through the wreckage looking for the one place the signal might have been real, then design a trial that’s actually capable of proving it.

IX. Inflection Point #3: The Bristol Myers Squibb Deal (2021)

By mid-2021, Prothena had something it badly needed after the NEOD001 collapse: not hope, but proof. Proof that a sophisticated buyer still believed the platform could produce real drugs.

In June 2021, Prothena announced that Bristol Myers Squibb exercised its option under the companies’ global neuroscience research and development collaboration to enter into an exclusive U.S. license for PRX005. BMS agreed to pay Prothena $80 million.

PRX005 was Prothena taking its protein-misfolding playbook straight into the center of the Alzheimer’s battlefield. The antibody was designed to target tau—specifically an area within tau’s microtubule binding region (MTBR)—with the goal of becoming a best-in-class anti-tau therapy for Alzheimer’s disease.

Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that aggregates and becomes hyper-phosphorylated in the brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s, forming neurofibrillary tangles. Alongside amyloid beta plaques, those tangles are one of the pathological hallmarks of the disease. The bet, as always, was that if you could precisely target the disease-relevant form, you might be able to change the trajectory—not just measure the wreckage.

Financially, the relationship was already meaningful. Including the new $80 million payment, Prothena said it had received $230 million under its collaboration with Celgene and Bristol Myers Squibb. Prothena also laid out the broader economics: the company said it could receive up to $160 million for U.S. rights, up to $165 million for global rights, and up to $1.7 billion in milestone payments—plus tiered royalties on potential product sales.

And BMS didn’t stop there.

By 2023, the partnership expanded again. Bristol Myers Squibb exercised its option to obtain exclusive worldwide commercial rights for PRX005 and agreed to pay Prothena $55 million.

The underlying collaboration targeted three proteins implicated in neurodegenerative disease: tau, TDP-43, and an undisclosed target. In other words, PRX005 wasn’t a one-off. It was one output of a broader engine BMS had decided was worth funding.

In 2024, that engine produced another opt-in moment. Prothena’s investigational new drug (IND) application for PRX019 was cleared by the FDA in December 2023, and BMS agreed to pay $80 million for exclusive global rights. The therapy targets an undisclosed protein, with a trial expected to get underway by the end of the year. Beyond the opt-in fee, Prothena said it would be eligible for development, regulatory, and sales milestones of up to $617.5 million, plus royalties.

Taken together, the strategic significance of the BMS relationship went well beyond the checks. It told the market that Prothena’s platform still commanded trust after a high-profile failure. And it reduced the company’s reliance on any single partner by building a second major pharma pillar alongside Roche.

X. Inflection Point #4: Prasinezumab Data & The Roche Pivot (2021-2025)

By the early 2020s, prasinezumab had become one of the industry’s longest-running live experiments in a single question: if you aim an antibody at alpha-synuclein, can you actually change the trajectory of Parkinson’s disease?

That’s the holy grail in Parkinson’s. Not another symptomatic patch. A drug that slows progression. And after decades of research across the field, that’s exactly where drug development has kept breaking down.

Roche ran two mid-stage studies—PASADENA and PADOVA—and the headline was frustratingly familiar: the trials showed numerical improvements in motor outcomes, but not the kind that cleanly crossed the bar for statistical significance.

Then came PADOVA.

In December 2024, Roche announced Phase IIb results showing that prasinezumab missed statistical significance on its primary endpoint, time to confirmed motor progression. The hazard ratio was 0.84 (confidence interval 0.69 to 1.01) with a p-value of 0.0657.

That’s the kind of result that drives teams crazy. A hazard ratio of 0.84 points to a meaningful reduction in risk—if it’s real and reproducible. But the p-value didn’t meet the traditional cutoff. The signal was there, just not clean enough to be definitive.

Roche did highlight a pre-specified analysis where the effect appeared stronger in participants treated with levodopa, which was most of the trial population. In that subgroup, the hazard ratio was 0.79 (confidence interval 0.63 to 0.99).

Despite the miss, Roche chose to keep going. The company said it would proceed into Phase III development in early-stage Parkinson’s, citing PADOVA, the Phase II PASADENA study, and the ongoing open-label extension (OLE) data. Roche’s Chief Medical Officer and Head of Global Product Development, Levi Garraway, said the decision was driven by “efficacy signals observed across the two phase II trials and their open-label extensions,” along with a favorable safety and tolerability profile.

For Prothena, the business stakes were clear. By that point, it had earned $135 million from the collaboration, with eligibility for up to $620 million more in milestones tied to regulatory and sales events, plus royalties if the drug ever reached the market. Prothena also held an option to co-promote prasinezumab in the U.S.

Gene Kinney framed Roche’s move as both validation and mission: “As pioneers in developing the first anti-alpha-synuclein targeting antibody, we are excited to see Roche advancing prasinezumab into Phase III development, with the potential to deliver the first disease-modifying treatment option to the millions of individuals living with Parkinson's disease and their families,” he said.

Still, plenty of observers weren’t ready to believe. Jefferies analysts pegged the Phase III program at just a 25% to 40% probability of success. Their skepticism wasn’t just about the statistics—it was about the biology. As they put it, the core debate was whether an antibody approach is potent enough to “slow the spread” of a protein that is largely intracellular.

That’s the fundamental challenge prasinezumab has always had to answer. Alpha-synuclein mostly lives inside neurons. Monoclonal antibodies mostly operate outside cells. So the bet hinges on how much of the disease process involves alpha-synuclein moving between cells through extracellular pathways—and whether intercepting that step is enough to matter clinically.

For Prothena, though, Roche’s decision to fund Phase III still mattered enormously. It meant the most expensive part of the journey would be paid for by Roche—while Prothena kept its upside if the science finally broke its way.

XI. The Current Era: Proprietary Pipeline Takes Center Stage (2023-Present)

By late 2024, Prothena had stitched together a portfolio that was, on paper, exactly what a post-NEOD001 biotech needed: multiple shots on goal, a blend of partnered and wholly owned programs, and enough cash to keep the engine running.

The company was also burning a meaningful amount of it. Prothena reported net cash used in operating and investing activities of $47.8 million in the fourth quarter and $150.3 million for the full year of 2024. It ended the year with $472.2 million in cash, cash equivalents, and restricted cash—and importantly, no debt. Between that balance and the economics embedded in its partnerships, Prothena had runway. It had options. And in biotech, options are oxygen.

One of those options turned into a major deal.

Novo Nordisk signed a definitive purchase agreement to acquire Prothena’s investigational drug PRX004, along with a broader ATTR amyloidosis program, for up to $1.2 billion. Novo agreed to pay Prothena $100 million in the near term for rights to PRX004, which Prothena had been developing for ATTR amyloidosis.

Strategically, the fit was obvious. Novo was pushing deeper into cardiovascular disease, and Prothena’s ATTR assets now had a well-resourced partner with real heart expertise. Under Novo, the program became NNC6019 (formerly PRX004), described as a potential first-in-class amyloid depleter antibody for ATTR cardiomyopathy, designed to deplete the pathogenic, non-native forms of transthyretin (TTR).

At the same time, Prothena kept moving its wholly owned Alzheimer’s portfolio forward. PRX012 stood out because it was designed as a once-monthly subcutaneous treatment, aimed at reducing treatment burden for patients and caregivers. PRX123, meanwhile, was designed to target both Aβ and tau—two proteins implicated in the causal biology of Alzheimer’s disease.

And then, in May 2025, the story swung hard in the other direction.

Prothena announced that the Phase 3 AFFIRM-AL trial of birtamimab—the revived version of NEOD001—did not meet its primary endpoint (HR=0.915, p-value=0.7680). Based on those results, the company said it would discontinue development of birtamimab, including stopping the open-label extension of the AFFIRM-AL trial.

“This is not the outcome that we expected, and we are surprised and disappointed by these results for patients, their families and caregivers, and for the entire AL amyloidosis community,” said Gene Kinney, Ph.D., President and Chief Executive Officer, Prothena.

In hindsight, the risk was well understood. Jefferies’ analysis had put the odds of success at roughly 25% to 30%. “We are at best cautiously optimistic,” the analysts wrote at the time.

But understanding the risk doesn’t blunt the impact when the result is negative—especially when it’s the second time the same fundamental program fails in late-stage testing. Prothena responded with dramatic cost cutting. In a post-market release on June 18, the company detailed a reorganization that included an approximately 63% reduction in its workforce. Prothena entered 2025 with 163 employees.

Prothena said the goal was to “substantially reduce its operating costs to those necessary to support its remaining wholly owned programs, its obligations to partnered programs, and its anticipated business development activities.”

Alongside the layoffs, Prothena revised its 2025 guidance. It now expected 2025 net cash burn from operating and investing activities of $170 to $178 million, and to end the year with approximately $298 million (midpoint) in cash, cash equivalents, and restricted cash.

Even after the birtamimab disappointment, the company still had meaningful potential catalysts ahead. Novo Nordisk expected to share data from its Phase 2 trial evaluating coramitug for ATTR-CM in the second half of 2025. Prothena expected to complete a Phase 1 clinical trial for PRX019 in collaboration with Bristol Myers Squibb in 2026. Bristol Myers Squibb expected to complete a Phase 2 TargetTau-1 clinical trial evaluating BMS-986446 in Alzheimer’s disease in 2027.

And crucially, Roche’s decision to advance prasinezumab into Phase 3 came just weeks after the birtamimab failure—providing a badly needed counterweight to the negative headlines. In a week when Prothena needed something to point to besides a shutdown and layoffs, its longest-running partnership was still alive, still funded, and still chasing the biggest prize in Parkinson’s: a true disease-modifying therapy.

XII. The Business Model & Strategic Playbook

By this point in the story, Prothena’s strategy is hard to miss. Over more than a decade, the company built itself less like a traditional “single-drug biotech” and more like a deal-driven engine: generate antibodies against misfolded proteins, advance programs to meaningful inflection points, then bring in big pharma partners to fund the most expensive parts of the journey—while Prothena keeps a slice of the upside and, crucially, keeps the platform.

You can see that playbook in the headline relationships it’s stitched together: Roche on prasinezumab, Bristol Myers Squibb across multiple neuroscience programs, and Novo Nordisk stepping in on its ATTR assets. The numbers attached to these deals run into the billions in potential payments, but the more important point is structural: Prothena repeatedly found a way to keep moving in a world where late-stage trials can bankrupt a small company.

The upside of that model is straightforward.

Risk gets distributed. Neurodegenerative trials are long, complex, and famously failure-prone. By partnering, Prothena doesn’t have to bet the entire company on the outcome of a single Phase 3. It can take its shot, survive the miss, and still have another program in motion.

Partnerships also function as validation. When companies like Roche, BMS, and Novo Nordisk commit real resources, they’re not doing it as charity. They’re signaling that Prothena’s science, assays, and antibodies are good enough to justify years of internal attention and hundreds of millions of dollars of development spend.

And then there’s capital efficiency. Upfront payments and milestones can fund operations without forcing Prothena to constantly tap the equity markets. In a business where dilution is often the silent killer, non-dilutive capital is oxygen.

But the most subtle advantage is optionality. Prothena isn’t just licensing away everything it invents. It’s choosing which programs need big pharma scale—and keeping the underlying capability to keep discovering the next wave. That’s how it remained a company even after two of the harshest moments in biotech: the 2018 NEOD001 collapse, and the 2025 birtamimab failure and restructuring.

The tradeoff is just as clear: this model caps the upside. If prasinezumab ever becomes a major Parkinson’s drug, Prothena won’t be the one building the commercial franchise. It’ll participate through milestones and royalties, but the partner captures most of the value. The same dynamic applies across the BMS and Novo Nordisk programs. For investors hunting for a single-company “moonshot,” that can feel like leaving the jackpot on the table.

Prothena’s capital allocation choices show it understands that trade. When programs fail, it has shown a willingness to cut fast and preserve runway rather than trying to maintain the illusion of scale. The layoffs in 2018 and 2025 weren’t just reactions to bad news—they were part of the survival mechanics of a company that’s trying to outlast the odds.

Even structurally, Prothena reflects this balancing act. It’s incorporated in Ireland, while its scientific center of gravity stays in South San Francisco—right in the middle of the Bay Area’s biotech talent base and within reach of the clinical and academic infrastructure needed to run sophisticated trials.

So the question that matters going forward isn’t whether Prothena can keep doing deals. It’s whether this platform-and-partnership machine can finally produce an approved medicine—through a partner, on its own, or ideally both. After more than thirteen years without a product on the market, the strategy has clearly sustained the company. What it hasn’t yet proven is the one thing biotech ultimately gets judged on: delivering a therapy that works in the real world.

XIII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Step back from the science for a moment, and Prothena’s world comes into focus as a tough, crowded arena where almost everyone is smart, well-funded, and chasing the same prize: the first therapies that actually change the course of neurodegenerative disease.

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

The barriers are real—deep scientific expertise, serious capital, and the ability to navigate regulators—but they’re no longer prohibitive. Biotech has gotten good at turning academic breakthroughs into venture-backed companies, and neuroscience remains one of the biggest magnets for ambitious founders and investors.

At the same time, the toolkit has expanded. AI-enabled discovery, faster structural biology workflows, and a steady stream of university spin-outs have all made it easier for new teams to take a credible swing at protein misfolding. The net effect for Prothena is simple: what once looked like a rare platform advantage gets harder to defend as the field learns, copies, and improves.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW-MODERATE

For most biotechs, the supplier base is a mix of CROs and CDMOs—and in many cases, those services are relatively commoditized. That gives companies like Prothena some negotiating leverage.

But not everything is interchangeable. Certain specialized reagents, platform technologies, and manufacturing capabilities can bottleneck with a smaller number of suppliers. And the most important “supplier” isn’t a vendor at all: it’s talent. Hiring and keeping experienced drug developers is still fiercely competitive, especially in the major biotech hubs Prothena depends on.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

If Prothena ever gets a drug approved, the biggest buyers won’t just be doctors and hospitals—they’ll be payers: insurers, government health systems, and pharmacy benefit managers. And in today’s environment, those buyers push hard on price, coverage, and evidence of real-world value. That scrutiny has only intensified as rare disease and specialty drug prices have come under the microscope.

Prothena also has another class of buyers: pharmaceutical partners. Those buyers negotiate aggressively, because they’re typically the ones paying for late-stage trials and carrying the commercialization risk. Prothena can secure big headline milestone numbers, but the balance of power often tilts toward the partner writing the biggest checks at the most expensive stages.

Threat of Substitutes: HIGH

Even if Prothena’s antibodies work, they don’t compete in a vacuum. Most of the company’s target diseases are battlegrounds where multiple therapeutic modalities are advancing at once.

In ATTR amyloidosis, RNAi therapies from Alnylam have become major competitors. In Alzheimer’s, approved antibodies like Leqembi sit alongside antisense approaches, small molecules, and emerging gene therapy strategies. In Parkinson’s, a successful prasinezumab would still face competition from other approaches, including gene therapy and small molecules.

That modality diversity shrinks the moat. “Working” is necessary, but it may not be sufficient—especially if other treatments are easier to give, safer, or more clearly effective.

Competitive Rivalry: VERY HIGH

This is the brutal one. Alzheimer’s approvals like Leqembi and Donanemab poured gasoline on the competitive fire, pulling in more capital, more talent, and more programs. ATTR amyloidosis is crowded too, with companies including Alnylam Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Intellia Therapeutics all active in the space. Alnylam, Ionis, and Pfizer have approved medicines on the market, though Alnylam’s and Ionis’s are currently cleared only for patients with nerve damage. Intellia, partnered with Regeneron, has also reported promising results using CRISPR gene editing to turn off production of the toxic protein.

Parkinson’s is a cautionary tale of its own. A number of alpha-synuclein programs have already disappointed—including efforts from Biogen and AbbVie—and even a UCB-developed pill licensed to Novartis has failed to deliver in clinical testing. That history doesn’t eliminate competition, but it does raise the bar for what it takes to convince the field that a new approach is truly disease-modifying.

And because clinical outcomes here are so binary, the dynamics skew toward winner-take-all. The first therapy that convincingly slows progression can capture the lion’s share of attention, adoption, and value—while “almost worked” is often treated as a failure.

XIV. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s framework is a useful way to pressure-test what Prothena really has—and what it doesn’t—when it comes to durable advantage. Because in biotech, it’s easy to confuse being scientifically interesting with being defensible.

Scale Economies: LIMITED

Biotech just doesn’t scale the way software or consumer products do. Yes, there are efficiencies in manufacturing antibodies at commercial scale, but they’re incremental—not transformative. The expensive part is R&D, and that doesn’t get cheaper just because you’re running more programs. Each new target demands new discovery work, new preclinical experiments, and a fresh gauntlet of clinical trials.

Network Economies: NOT APPLICABLE

There are no network effects in drug development. More trial participants don’t make the therapy intrinsically more valuable to the patients already enrolled. There’s no flywheel where more “users” attract more users. If a drug works, it works. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t.

Counter-Positioning: MODERATE (HISTORICALLY)

Early on, Prothena’s conformation-specific antibody approach was meaningfully contrarian. While much of the field focused on total protein levels or broader, less selective targeting, Prothena’s argument was sharper: the dangerous thing isn’t just the protein—it’s the misfolded, disease-causing form of it. Aim at that, and you might get both better efficacy and fewer side effects.

But counter-positioning fades when everyone catches up. Over time, that specificity mindset became common across neurodegeneration programs. What once differentiated Prothena increasingly became table stakes.

Switching Costs: LOW TO MODERATE

For patients, switching costs could be high once a chronic therapy is established—habits form, protocols harden, and physicians tend to stick with what works. But Prothena doesn’t have that advantage today because it has no approved products.

For partners, switching costs are more real. Once a collaboration is underway, there’s sunk spend, shared data, and organizational muscle memory built around the program. Roche and BMS have invested substantially, which creates some friction against walking away lightly.

For investors, switching costs are basically zero. Prothena is a liquid public stock. Capital can move in and out instantly.

Branding: LOW (FOR NOW)

Without an approved medicine, Prothena doesn’t have a “brand” in the way a commercial biotech does. What it has is scientific credibility—reputation with partners, researchers, and potential hires. That helps, but it’s not durable in the way consumer branding can be. In biotech, reputational capital can be damaged quickly by a single trial failure, and rebuilt only slowly over years.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE-HIGH

This is Prothena’s clearest strength. The company has accumulated assets that are hard to reproduce on a short timeline:

- Proprietary Neotope platform IP and antibody engineering know-how built over decades

- Deep institutional understanding of protein misfolding biology, across multiple diseases

- Partner-validation through relationships with Roche, BMS, and Novo Nordisk

- Scientific leadership with a long track record in this niche

A newcomer can raise money and hire talent, but it’s much harder to replicate a mature platform plus the credibility that comes from repeated pharma diligence and long-running collaborations.

Process Power: MODERATE

Prothena has also built process power: repeatable ways of discovering and optimizing antibodies against misfolded proteins, plus development experience in rare and neurodegenerative diseases. And importantly, that process power was sharpened by failure.

The NEOD001 collapse didn’t just hurt—it taught. Prothena’s later programs reflected those lessons: tighter patient selection, better biomarker strategies, and more careful trial design. That kind of hard-earned iteration is a real advantage versus teams that haven’t been through a late-stage blowup.

Overall Assessment: Prothena’s defensibility comes mainly from Cornered Resource—platform IP and specialized expertise—and an emerging layer of Process Power from years of iteration. It doesn’t benefit from scale or network effects, and its brand advantage is limited without products. Ultimately, durability still hinges on the one proof point it hasn’t delivered yet: turning the platform into an approved medicine, after more than thirteen years in the public markets.

XV. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Platform validated by multiple partnerships: Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Novo Nordisk have each signed up to work with Prothena, with deals that include large potential milestone totals. In biotech, that matters because it’s not casual money. These companies run deep diligence—on the biology, the antibodies, the assays, the manufacturability, and the clinical logic—before they commit. The simple bull argument is: if multiple world-class buyers keep opting in, the platform is probably producing real drug candidates.

Multiple shots on goal: Prothena isn’t living or dying on a single program. Its portfolio stretches across Parkinson’s (prasinezumab with Roche), Alzheimer’s (including BMS-986446 targeting tau and Prothena’s own PRX012 targeting amyloid-beta), an additional BMS program with PRX019 (target undisclosed), and ATTR cardiomyopathy through Novo Nordisk’s coramitug program. That diversification doesn’t guarantee a win—but it does make it more plausible that at least one program can break through.

Learning from failures: The company has had painful misses, but it hasn’t stood still. Trial design, endpoints, and patient selection have all evolved as the broader field has learned what does and doesn’t work in neurodegeneration and amyloid diseases. The decision to keep pushing prasinezumab forward, for example, reflects an attempt to build a Phase 3 plan informed by what the Phase 2 trials did and didn’t show.

Strong cash position: Prothena ended the first quarter of 2025 with $418.8 million in cash, cash equivalents, and restricted cash, and no debt. In that same quarter, it reported a net loss of $60.2 million, improved from $72.2 million a year earlier. After the 2025 restructuring, Prothena guided to ending 2025 with around $298 million in cash—meaning it has runway to reach several upcoming clinical and partnership milestones.

Enormous unmet need: The prize here is huge because the need is huge. Neurodegenerative diseases still have limited options that truly change outcomes, and Parkinson’s alone affects more than 10 million people worldwide. If any program in this space shows clear disease modification—not just symptom relief—the market opportunity can be transformative.

Scientific advances improving the odds: The field has gotten better at measuring disease and picking patients—biomarkers, imaging, and more refined clinical frameworks all help. And the approvals of Alzheimer’s antibodies like Leqembi and Donanemab showed that targeting amyloid can translate into clinical benefit, even if the effect sizes are debated. For the bull, that’s a sign the general “go after the misfolded protein” approach isn’t fantasy—it can work under the right conditions.

Management continuity: Gene Kinney has led Prothena since 2016, steering it through leadership transition, a major Phase 3 failure, a rebuild, and another late-stage disappointment. In a business where constant resets can kill momentum, continuity and institutional memory are real assets.

The Bear Case

No approved products after thirteen years: At some point, the cleanest bear argument is also the most brutal one: Prothena has been public for more than a decade and still hasn’t produced an approved therapy. That invites the uncomfortable question of whether the platform is good at generating candidates—but not good enough to produce approvals.

History of clinical failures: NEOD001 failed, then birtamimab failed again in May 2025. Prasinezumab also missed primary endpoints in two Phase 2 trials, even though Roche is advancing it. When multiple late-stage bets don’t pan out, investors start to wonder whether the problem is execution, biology, or both.

Highly competitive markets with better-funded rivals: ATTR amyloidosis, in particular, is crowded with serious competitors, including Alnylam Therapeutics, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Intellia Therapeutics. Several of these companies already have products, deep cash reserves, and commercial infrastructure. Even if Prothena’s science works, it may be fighting uphill against incumbents.

Protein misfolding is still debated as a path to disease modification: Alzheimer’s approvals helped validate amyloid targeting, but the benefits have been modest and the mechanism remains contested. More broadly, “protein misfolding” is a compelling framework, not a guarantee—especially in diseases where the most toxic species may be intracellular or where pathology may be downstream of earlier triggers.

Partnership dependency caps upside: Prothena has repeatedly chosen to partner, which keeps it alive—but it also means it often earns a slice rather than the whole pie. If prasinezumab becomes a major drug, Roche will capture most of the economics. Royalties and milestones can be meaningful, but they’re not the same as owning a full commercial franchise.

Dilution risk: Even with meaningful cash today, timelines in CNS drug development are long. If programs drag, trials expand, or markets close, Prothena could still end up needing to raise capital—diluting shareholders in a way that quietly erodes returns over time.

Clinical trials are long and binary: The “valley of death” is still there. Years can pass between major readouts, cash keeps burning, and outcomes can swing the stock violently. That volatility isn’t incidental—it’s the business model of clinical-stage biotech.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking Prothena, two things tend to matter more than anything else:

-

Clinical trial readouts: This is where value is created or destroyed. Major upcoming catalysts include Novo Nordisk’s Phase 2 coramitug data in the second half of 2025, PRX012 Phase 1 data expected in August 2025, and BMS-986446 Phase 2 data expected in 2027.

-

Partnership cash flows and milestones: Prothena said it could receive up to $105 million in 2026 tied to clinical milestones across partnered programs. The practical question is whether those payments actually arrive on schedule. Milestone receipts signal progress; delays, deferrals, or partnership pullbacks often signal trouble.

XVI. Epilogue: What's Next for Prothena?

As 2025 draws to a close, Prothena is back at a familiar place: smaller, leaner, and forced to focus after the birtamimab setback—but still alive, still funded, and still in position for the kind of data-driven turning point that can change the entire narrative.

The world Prothena operates in has also changed. Neurodegeneration is no longer a graveyard where every hypothesis goes to die in Phase 2. The field has matured, and Alzheimer’s in particular has moved into a new era—one where anti-amyloid antibodies like lecanemab (Leqembi), approved in January 2023, and Donanemab have shown that targeting misfolded proteins can translate into measurable clinical benefit. That’s a quiet kind of vindication for the premise Prothena was built on.

It’s also a new kind of competition. The moment the category proves itself, the best-funded players pile in, standards rise, and yesterday’s contrarian bet becomes today’s crowded trade.

One of the clearest signals of that maturation is the push toward combination strategies—simultaneously testing drugs that act on both amyloid and tau. The logic is intuitive: if these diseases have multiple pathological drivers, a single therapy may not be enough. Combination approaches raise the possibility of additive or even synergistic benefit, and they could redefine what “effective” looks like in neurodegenerative disease treatment.

So the question hanging over Prothena is the one it’s been chasing since day one: can it finally get a drug approved?

In the near term, the closest thing to that shot is still prasinezumab in Parkinson’s—now in Roche’s hands in Phase 3 development. It’s the longest-running, most public test of Prothena’s platform, and it’s aimed at one of the most valuable prizes in medicine: a therapy that slows Parkinson’s progression rather than simply masking symptoms. But the clock runs long in CNS drug development, and the uncertainty is real. Analysts putting the probability of success in the 25% to 40% range aren’t being cynical—they’re reflecting how hard it is to prove disease modification, and how unsettled the biology remains around alpha-synuclein targeting.

From here, Prothena’s strategic options are straightforward, even if none of them are easy.

Stay independent: keep costs tight, advance the proprietary pipeline, and let partners fund the most expensive swings. It preserves optionality, but it also means living with the volatility of a clinical-stage biotech where years of work can hinge on a single readout.

Get acquired: Prothena has platform expertise, long-standing partnerships, and a body of hard-won institutional knowledge in protein misfolding. Those are real assets to a larger company that wants a neuroscience footprint. But any deal would be shaped by recent clinical disappointments and whatever leverage the market is willing to assign.

Continue the partnership model: double down on what has kept the company alive—more collaborations, more shared risk, more non-dilutive capital. It extends runway and reduces existential trial risk, but it also deepens the dependence on partners and caps how much upside Prothena can capture if something hits.

Over all of this sit broader forces that could tilt the odds. AI-driven discovery may accelerate parts of antibody design and target selection, but it could also compress the time it takes competitors to replicate platform advantages. Biomarkers and precision medicine could finally improve patient selection—the silent killer of so many neurodegeneration trials—making it more likely that the right drugs show their effect in the right populations.

And what would “winning” actually look like? It could be prasinezumab succeeding in Phase 3 and becoming a marketed therapy, turning years of effort into milestones and royalties and, more importantly, a real clinical impact. It could be strong data from Bristol Myers Squibb programs, or validation from Novo Nordisk’s coramitug work in ATTR-CM. But the real finish line is simpler than any deal term: an approved drug that proves Prothena’s platform can consistently turn a scientific idea into something that helps patients.

For the millions living with Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and amyloidosis—and the families watching those diseases take their toll—that’s the only outcome that ultimately matters.

XVII. Final Reflections & Lessons

Prothena’s thirteen-year journey offers lessons that go well beyond one ticker symbol. It’s a case study in how modern biotech actually works—slowly, expensively, and with an uncomfortable amount of uncertainty.

The Long Arc of Biotech: From its spin-out to today, Prothena has lived through the full spectrum: a parent company’s accounting scandal legacy, late-stage clinical disappointments, a major leadership loss and transition, high-stakes partnership negotiations, and repeated strategic pivots. The path has been longer and harder than almost anyone would have predicted in 2012. Investors who expected a straight line to a product got whiplash. Investors who came in understanding that drug development is probabilistic—where years of “progress” can be undone by one readout—were at least emotionally and financially prepared for the volatility.

Partnership Strategy as Survival Mechanism: Prothena’s willingness to partner early and often wasn’t just smart—it was survival. The capital and validation that came from Roche, Celgene/BMS, and Novo Nordisk kept the company funded when proprietary programs fell apart. The trade is obvious: you give up some upside. But you also avoid the most common cause of death for a clinical-stage biotech—running out of money before the science has its next chance to prove itself. In a high-failure area like neuroscience, that trade-off can be rational.

Scientific Integrity Matters: Prothena preserved credibility in the moments that most often destroy it: when the data doesn’t cooperate. The company has generally been direct about failures and focused on what can be learned from them rather than trying to talk its way around them. Dale Schenk, in particular, earned respect not only for his scientific track record and science-led decisions, but for his openness to being challenged. That kind of culture—where you can admit a hypothesis didn’t pan out and still keep going—separates companies that can rebuild from companies that collapse.

Persistence in the Face of Failure: Few moves capture biotech’s stubbornness like Prothena reviving birtamimab after 2018. The second attempt ultimately failed too, but the impulse was serious: go back to the data, look for a real signal, and design a trial that could answer the question cleanly. In drug development, persistence isn’t optimism. It’s a recognition that biology is messy, endpoints can mislead, and sometimes the first trial doesn’t test the right version of the hypothesis.

The Human Element: All of this only matters because real people are waiting. Millions living with Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and amyloidosis still face limited options—especially when it comes to therapies that slow or stop disease, not just manage symptoms. Prothena’s story is ultimately about teams of scientists and clinicians trying to compress decades of suffering into something treatable. If Prothena ever “wins,” the score won’t just be measured in market value. It will be measured in time—months and years returned to patients and families.

The Future of Protein Misfolding Science: Peptides and proteins have been found to have an inherent tendency to shift from native functional states into durable amyloid aggregates. That tendency is associated with a growing list of disorders, including Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases, type II diabetes, and multiple systemic amyloidoses. Over the last decade, the field has advanced in understanding the nature of amyloid formation and its consequences.

Whatever Prothena’s eventual commercial fate, the scientific work it has helped push forward—how misfolding starts, how aggregates drive damage, and how antibodies might intervene—adds to a knowledge base the whole industry will build on. In biotech, that’s the uncomfortable truth: even the programs that fail can move the field forward, setting up the next generation of therapies—and sometimes the next generation of companies—to succeed.

XVIII. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper on Prothena—and on the broader scientific debate over protein misfolding—these are some of the most useful starting points:

Company Resources: Prothena’s investor relations site (investor.prothena.com) is the primary source for corporate presentations, SEC filings, earnings materials, and pipeline updates. It’s the best place to track what the company says about its own programs, timelines, and partnerships.

Scientific Background: The foundational biology lives in the peer-reviewed literature on protein misfolding, aggregation, and neurodegeneration. Nature Medicine and Nature Neuroscience are reliable places to start, and Amyloid (the official journal of the International Society of Amyloidosis) is especially relevant for the systemic amyloidosis side of the story.

Industry Context: Elan’s history is essential context for Prothena’s origins. Contemporary reporting in the Irish Times and The Wall Street Journal captured the accounting controversy, the restructuring, and the strategic unraveling that ultimately made the 2012 spin-out possible.

Clinical Trial Data: For the most current snapshots, medical conferences often show the data before it appears in journals. Watch meeting presentations from AAIC (Alzheimer’s Association International Conference), AD/PD (International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases), and AHA Scientific Sessions, where updates on programs like prasinezumab and BMS-986446 have been discussed.

Competitive Landscape: To understand what Prothena is up against, it helps to follow leaders in neighboring approaches—Alnylam’s ATTR portfolio, Biogen/Eisai’s Alzheimer’s antibodies, and the expanding set of gene therapy and gene editing strategies aimed at similar biology.

Partnership Economics: If you want to decode the deal terms and incentives behind Prothena’s model, Nature Biotechnology and BioPharma Dive regularly break down biotech partnership structures and the economics that shape who takes what risk—and who keeps what upside.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music