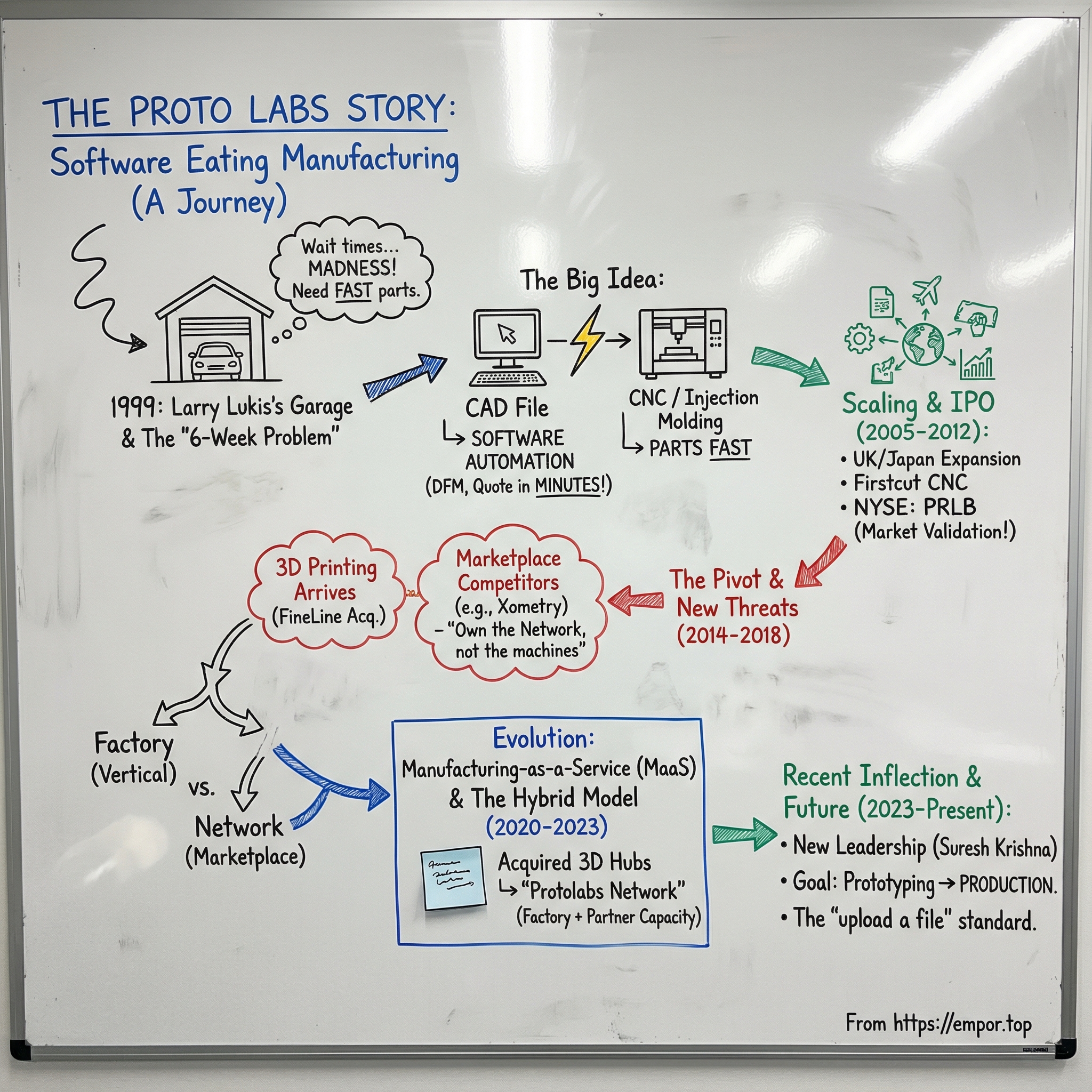

Proto Labs Inc.: The Story of Digital Manufacturing's Pioneer

I. Introduction: The Revolution That Started in a Garage

Picture the scene: late 1990s, suburban Minnesota. An engineer named Larry Lukis is staring at his calendar, doing the same math he’s done too many times before: how long until the prototype parts show up?

Six weeks. Maybe eight.

And that’s the maddening part. This isn’t a moonshot R&D program. These are prototype injection-molded parts—exactly the kind of thing a product team needs quickly, so they can test, iterate, and get on with building. But manufacturing at the time didn’t move at the speed of product development. It moved at the speed of fax machines, phone calls, and human bottlenecks—quote requests that sat in inboxes, DFM feedback that arrived days later, tooling plans that required a specialist’s time before anything could even start.

Lukis couldn’t shake a simple question: what if the whole front end of manufacturing worked like software?

What if you could upload a CAD file to a website and get an immediate answer: here’s the price, here’s the lead time, and here are the features of your design that will cause problems? What if software could do, in minutes, what took experienced engineers days—analyzing manufacturability, generating a quote, and translating a design into machine instructions?

That frustration turned into an obsession. Lukis started building the system himself—writing more than a million lines of code with a single goal: remove the humans from the slow parts of the process, so the machines could start working almost immediately. The result became Proto Labs, one of the earliest and most successful examples of “software eating manufacturing”—a company built on the idea that speed wasn’t a nice-to-have, it was a product.

By 2024, Proto Labs reported $500.9 million in revenue and served more than 51,552 customer contacts. But the numbers aren’t the point. The point is what they represent: a garage-born idea in Long Lake, Minnesota that became, for many engineers, the default answer to a high-stakes question—how fast can I get a real part in my hands?

And then the market caught up.

Proto Labs went public in 2012, its stock surged in the year that followed, and for a while Wall Street treated it like a rare creature: a manufacturing company with tech-company economics. The stock hit an all-time high closing price of $251.49 on January 27, 2021. Today it trades at a fraction of that peak, with a much harder question hanging over the business: now that digital manufacturing is a crowded category, can the company that invented the playbook still win?

Because this isn’t just a story about one company’s rise. It’s a story about what happens when software reshapes a physical industry—and what happens when the disruptor becomes the incumbent.

II. The Garage Origins and Larry Lukis's Frustration (1980s–1999)

Larry Lukis liked to describe himself as “a computer geek” who just happened to love manufacturing. And by the late 1990s, that combination put him on a collision course with one of the most aggravating realities in product development: you could design a part on a computer in hours, but getting that part made—especially in injection-molded plastic—could take six to eight weeks.

Lukis had lived that pain firsthand as a design engineer and product developer. The routine was always the same. You finished a CAD model, sent it out, and then the clock started: calls to shops, drawings back and forth, quotes that took days, terms to negotiate, and finally a long wait while tooling and production crawled through a series of manual steps. It wasn’t that manufacturing equipment was slow. CNC mills and injection molding presses could move fast. The front end was the problem.

The bottleneck was human.

Before a machine ever cut metal, skilled mold designers and machinists had to review the geometry, figure out how to make it, decide where the parting line should go, spot the undercuts that would trap the part in the mold, and program the toolpaths. None of that was easy to scale, none of it was instant, and all of it depended on scarce expertise.

So Lukis asked the question that would become Proto Labs’ founding idea: what if software did that work instead?

In 1999, he launched The ProtoMold Company—later Proto Labs—with a straightforward mission: radically reduce the time it took product developers to get plastic injection-molded prototype parts. The way he planned to do it wasn’t by hiring an army of mold designers. It was by writing software that could analyze 3D CAD models automatically, generate manufacturability feedback, and push jobs digitally into a connected set of machines for quick-turn production.

The company began in a garage in Long Lake, Minnesota, then moved into a space in Maple Plain that would eventually become Plant 1. Lukis funded the early build with his personal savings and a $500,000 loan secured against his house—real, personal conviction behind a very technical bet.

And the early years were as technical as it gets. Lukis wasn’t trying to build a traditional manufacturer. He was building a software company that happened to own machines. The code needed to replicate what experienced mold designers did almost instinctively: flag walls that were too thin or too thick, identify undercuts that would make ejection impossible, estimate cycle times, and generate toolpaths that could reliably produce quality parts. On top of that, it had to handle the messy reality of injection molding—where every geometry has its own traps and every plastic behaves a little differently.

The thesis was elegant. The execution was brutal.

But when it worked, it felt like magic. A customer could upload a CAD file and get an interactive quote with design feedback in minutes, not days. That shift—turning manufacturing’s slowest, most manual steps into software—was the real breakthrough. Proto Labs wasn’t just selling speed, even though it delivered it. It was selling certainty and convenience: know the price, know the lead time, and know what to fix in your design before you commit.

And that, more than anything, is how a frustrated product developer in Minnesota set out to compress weeks of waiting into something that behaved like the internet.

III. The Technical Magic: Building the Software-Manufacturing Stack (1999–2005)

Proto Labs didn’t invent injection molding. It didn’t invent CNC machining either. What it invented was a new way to run them: treat manufacturing like a software problem, and automate the judgment calls that used to live in a handful of specialists’ heads.

As the company put it:

"Our software allows us to feed in a customer's CAD drawing of a part, and the software will spit out commands to the machine to create the part. It happens automatically. It lets us be cost-effective in low volumes and very fast because we don't have to take the time for a person to sit down and program the machine."

To understand why that mattered, it helps to remember what “normal” looked like in a machine shop back then. A customer would send over a design, and a human would take it from there: review the geometry, trade emails and calls to clarify details, flag the manufacturing risks, estimate time and cost, and only then—if the quote was accepted—manually program the machines or design the mold. The equipment could move quickly. The process around the equipment was slow.

Proto Labs flipped the sequence. The customer uploaded a 3D CAD file through a web interface. Often within minutes, the software analyzed whether the part could be made, returned a firm price quote, and surfaced recommended design changes. When the customer hit “order,” the automation went deeper—into steps like mold design that traditionally required skilled labor.

Under the hood, Lukis was trying to do something deceptively hard: encode the instincts of experienced manufacturing engineers into algorithms. The software learned to spot trouble before it became scrap—features like thin walls that might not fill, draft angles too shallow for ejection, or sharp internal corners that could cause problems. It could estimate cycle times, material usage, and the work required to produce the part. In other words, it wasn’t just quoting faster. It was deciding faster.

That software-first stack became the company’s path through a crowded prototyping world, and a lasting advantage. Many competitors aimed their tools at helping machinists work more efficiently. Proto Labs was aiming at removing the need for a machinist to do the upfront programming at all.

By 2001, Lukis realized that building the technology and building the company were two different jobs. He had founded The ProtoMold Company, Inc. in 1999, but in 2001 Brad Cleveland joined as CEO and president—hired through an unusually direct process: Lukis placed a newspaper want ad for a CEO, and Cleveland answered it.

The split was clean and, by all accounts, ideal. Cleveland took on the operating job of scaling the business. Lukis went all-in on the core software. After Cleveland arrived, Lukis no longer had direct reports, which freed him to stay focused on the automation engine that made the whole model work.

By 2005, the business was still small, but the shape of the machine was obvious. When Brian Smith, president of Private Capital Management in Eagan, first invested that year, Proto Labs—still operating as Protomold—had $10 million in revenue and 20 employees.

The customers were exactly who you’d expect: product developers inside large companies, under constant pressure to compress development cycles. They weren’t ordering massive production runs. They were ordering small quantities to prove form, fit, and function—or to bridge to production while a high-volume mold was being built elsewhere. In those moments, Proto Labs believed it offered a combination that traditional suppliers rarely matched all at once: speed, competitive pricing, ease of use, and reliability.

And by the mid-2000s, the flywheel was starting to turn. More orders meant more real-world data feeding the software. Better software meant a smoother experience and faster turnaround. A smoother experience created repeat behavior. Over consecutive years, roughly 77%, 77%, 81%, and 85% of orders came from repeat customers.

In manufacturing, loyalty like that is rarely about brand. It’s about certainty. Proto Labs was building a system where customers could click “upload” and feel like the hard part was already done.

IV. Scaling the Model: From Protomold to Proto Labs (2005–2012)

From 2005 to 2012, Proto Labs went from “this works” to “this scales.” The core engine—CAD in, parts out, with software doing the heavy lifting—was proven. Now the question was how far they could push it.

The first big step was geographic. In 2005, Protomold opened its first UK plant in Telford, England, taking the model across the Atlantic and closer to European customers who wanted the same thing Americans did: real parts, fast, without the traditional procurement slog.

Then came the next expansion: technology. Two years later, the company introduced Firstcut, its quick-turn CNC machining service. It was a natural adjacency. Injection molding and CNC machining solve different problems, but they show up in the same development cycles and on the same engineers’ desks. A team might CNC a part to validate geometry, then move to injection molding to test material behavior or prepare for a bigger production run. By offering both—wrapped in the same software-driven experience—Proto Labs could win more of the workflow, not just a single order.

In 2009, the company pulled the branding together, combining Protomold and Firstcut under the corporate name Proto Labs Inc., commonly known as Protolabs. That same year it opened a location in Japan to serve Japanese design engineers. Firstcut also expanded what it could make, offering CNC-machined prototype parts in aluminum and plastics including ABS, nylon, and PEEK.

By this point, the value proposition had hardened into a set of advantages that were hard to unsee once you’d experienced them. Speed was the headline: Proto Labs could deliver injection-molded parts in as little as one day after receiving a design, versus weeks from traditional suppliers. Just as important was the removal of friction—instant quoting instead of a slow back-and-forth, and no minimum order requirements that forced engineers to buy more parts than they needed just to make the economics work.

The results showed up in the financials. Total revenue grew from $35.9 million in 2007 to $98.9 million in 2011, and reached $92.4 million in the nine months ended September 30, 2012. Income from operations rose from $8.4 million in 2007 to $26.9 million in 2011.

It also became clear why the incumbents struggled to respond. Traditional machine shops ran on human expertise at every step: quoting, design review, programming, process planning. To match Proto Labs’ turnaround times, they couldn’t just “try harder”—they would have needed to rebuild their workflow around software and automation. Most didn’t have that capability, and many couldn’t risk disrupting the way they already made money. Proto Labs had counter-positioned them.

Inside the company, the culture reflected what it really was: a manufacturer that thought like a software business. The workforce later grew from 750 to 1,750 just since 2014. Today Proto Labs has more software professionals than manufacturing engineers, and that means competing for talent with the Amazons, Googles, and Facebooks of the world.

In 2016, Workplace Dynamics recognized Protolabs as a top-ranked workplace in Minnesota. It was an unusual blend—proud of manufacturing craft, but with Silicon Valley-style ambition about what software could automate.

The financial profile was unusual too. Proto Labs produced manufacturing-style gross margins in the mid-40s percentage range, while benefiting from the way software scales: once the automation systems were built, additional orders could flow through with relatively little incremental human labor. That operating leverage was something most job shops simply weren’t built to achieve.

In June 2012, Larry Lukis and Brad Cleveland won the Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award for their work with Protolabs. In 2013 and 2014, Protolabs was recognized by Forbes in the top 5 of America’s Best Small Companies.

V. Going Public: The 2012 IPO and Market Validation

Proto Labs hit the public markets on February 24, 2012, listing on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker PRLB. It wasn’t an early-stage story being sold to investors—this was a profitable, already-scaling business. And the first year of trading made that clear fast.

In the weeks after the IPO, the stock took off. By mid-March, shares were up roughly 192% from the offering, and before long the stock had roughly tripled—making Proto Labs one of 2012’s top IPO performers, tied with Guidewire Software.

That response wasn’t just hype. The timing lined up with a bigger narrative investors wanted to believe in. The U.S. was crawling out of the Great Recession, “reshoring” was becoming a serious theme, and the market was hunting for proof that American manufacturing could still win—just not on cheap labor. Proto Labs was a clean example of the alternate playbook: compete on speed, automation, and software-driven precision.

In a sense, the IPO was Wall Street’s stamp of approval on Larry Lukis’s original thesis. The market valued Proto Labs less like a job shop and more like a technology company that happened to ship physical parts.

Brad Cleveland, Larry Lukis, and then-CFO Jack Judd rang the bell at the NYSE, marking the transition from scrappy, software-obsessed upstart to public company.

The business kept growing. In 2013, Proto Labs reached $150 million in revenue. But going public came with its own gravity. Quarterly expectations replaced long, quiet stretches of building. The company now had to pair its engineering-driven culture with SEC reporting, guidance, and the constant presence of analysts and investors.

Then came the next major change: leadership.

On October 31, 2013, CEO Brad Cleveland announced his intention to resign. After more than a decade taking the company from startup to IPO, he was ready to step back.

In February 2014, Proto Labs named Vicki Holt President and Chief Executive Officer. Holt brought a different kind of résumé than the founders: deep, traditional manufacturing experience and a track record running a public company. Before joining Proto Labs, she had been CEO of Spartech Corporation, where she led a turnaround that drove a major increase in operating earnings and culminated in Spartech’s sale to PolyOne in March 2013.

Proto Labs hired Holt with an ambitious goal in mind: help turn the company into a billion-dollar manufacturing business. Her operating and manufacturing background was a complement to the software-heavy foundation Lukis had built—and a signal that the next chapter would be about scaling not just the code, but the enterprise.

VI. The 3D Printing Pivot: Acquisition Strategy Begins (2014–2016)

When Vicki Holt took over in 2014, Proto Labs faced a question it could no longer ignore: what happens when the fastest way to get a part isn’t cutting or molding at all?

Additive manufacturing—3D printing—was moving from novelty to real tool. For Proto Labs, it landed as both a threat and an obvious adjacency. If engineers could print certain prototypes instead of molding them, that could siphon off some of Proto Labs’ core business. But those same engineers also wanted printed parts alongside machined and molded ones. If Proto Labs didn’t offer it, someone else would—and that “someone else” could become the front door.

So Proto Labs changed its stance.

In 2014, it acquired FineLine Prototyping Inc., an additive-heavy prototyping shop based in North Carolina, for $37 million. FineLine used processes like direct metal laser sintering, stereolithography, and selective laser sintering to produce prototypes for manufacturers around the world. It employed 85 people and had generated approximately $9.7 million in revenue the prior year.

This was a meaningful pivot. Proto Labs had built its reputation on speed through automation, mostly in subtractive and molding processes. In the past, it had said it didn’t plan to invest in 3D printing. FineLine made that position obsolete—and strategically, it fit.

As Holt put it at the time:

"The acquisition of FineLine is consistent with Proto Labs' strategy to expand sales to product developers through envelope expansions and addition of new service offerings which reduce time, cost and waste in new product development,"

The deal didn’t just add a new technology; it widened the product story. Proto Labs could now meet engineers earlier in the design cycle, when “good enough, right now” matters more than perfect tooling. And it doubled down in 2016 by expanding its additive offering and moving those services into a 77,000 square foot facility in Cary, North Carolina.

Stepping back, you can see the strategy taking shape: become the default manufacturing partner for product developers. Instead of sending files to three or four different vendors—one for printed prototypes, another for CNC, another for tooling—customers could increasingly run the whole journey through Proto Labs.

This was Proto Labs widening its identity from “fast injection molding” into something bigger: a broader digital manufacturing platform, stitched together by the same core idea that started in Larry Lukis’s garage—use software to remove friction, compress timelines, and make sophisticated manufacturing feel almost self-serve.

VII. The Inflection Point: European Expansion and Competitive Pressure (2015–2018)

By the mid-2010s, Proto Labs wasn’t just exporting its model to Europe. It was putting real weight behind it.

The company made what it described as its largest European infrastructure investment since establishing its UK business in 2005—spending around €4 million on new manufacturing technology and facility renovations, with most of the work centered in Telford and additional upgrades across its other European locations. The logic was simple: customer demand in Europe was rising, and Proto Labs wanted to meet it with more capacity and more capability.

Not long after, it went even bigger on additive. Protolabs Europe, headquartered in Telford, opened a new €16 million European Additive Manufacturing center in Putzbrunn near Munich, Germany, increasing additive manufacturing capacity by 60%.

At the time, the European footprint looked like a mini version of what Proto Labs had built in the U.S.: manufacturing facilities in Telford in the UK, in Eschenlohe and Feldkirchen in Germany, and sales and customer support offices in France, Italy, and Sweden.

But while Proto Labs was expanding its physical footprint, the market around it was changing faster than new machines could be installed.

A new generation of digital manufacturing platforms was showing up—companies that had watched Proto Labs prove the demand for instant quoting and fast-turn parts, and then asked a different question: what if you didn’t own the machines at all?

Proto Labs had become the original “digital disruptor” by bringing 3D printing and machining equipment in-house and pairing it with software that could turn a CAD file into a fast quote and a predictable outcome. The upside was control: quality, speed, repeatability. The tradeoff was inherent: if you rely on your own equipment, you’re limited by the materials, geometries, lead times, and cost structures that your factories can support.

That constraint created room for a new model to thrive.

Xometry, founded in 2013, took a marketplace approach. Instead of building factories, it built a platform that connected customers to a network of manufacturing partners. In plain terms, Proto Labs tried to be the on-demand manufacturer. Xometry tried to be the on-demand manufacturing coordinator—matching each job to a shop that could do it.

That marketplace approach brought a different kind of scale. Xometry could offer far more options than any single vertically integrated player could, because it wasn’t bounded by what fit inside its own four walls. It pointed to a network with over 55,000 active buyers and 3,400 active small-to-medium-sized manufacturers—breadth and depth that could outmatch Proto Labs’ in-house menu.

In that new competitive context, Proto Labs was no longer the only fast, digital front door. Customer acquisition got more expensive. Growth, while still solid, started to slow. And the premium investors had assigned to the pioneer—part tech company, part manufacturer—began to narrow as the category it created started to fill in.

VIII. The CEO Transition and Strategic Reset (2019–2020)

By the end of 2020, Proto Labs was heading into another leadership handoff—this time in the middle of a global stress test for manufacturing.

On December 14, 2020, the company announced that Vicki Holt would step down as chief executive officer after seven years in the role, effective March 1, 2021. Her successor would be Robert (Rob) Bodor, then Vice President and General Manager of the Americas.

Proto Labs’ chairman, Archie Black, framed it as an orderly changeover. “This transition follows a carefully planned succession process and Rob is the right person to lead the company,” he said.

But “orderly” didn’t mean “easy.” The timing was brutal.

During the 2019–2020 coronavirus pandemic, Proto Labs leaned into the moment. It began producing face shields, plastic clips, and components for coronavirus test kits for use in Minnesota hospitals. It also partnered with the University of Minnesota to produce parts for a low-cost ventilator.

COVID created a strange, contradictory set of forces for the business. On one hand, the supply chain chaos pushed more people to value local, responsive manufacturing—the exact pitch Proto Labs had been making for two decades. On the other, broader industrial activity slowed, and many customers hit pause on new product development altogether.

Holt had taken Proto Labs from high-growth public-market darling into a more complex, multi-technology manufacturing platform. Now Bodor would inherit the next question: could Proto Labs reset and re-accelerate in a world that was finally full of “digital manufacturing” options?

By the time Holt retired in March 2021, Proto Labs was still a technology-enabled rapid manufacturer of custom prototypes and on-demand production parts, with manufacturing facilities in five countries. The mission hadn’t changed. The environment had.

IX. The Manufacturing-as-a-Service Evolution (2020–2023)

In January 2021, Proto Labs made one of the clearest admissions yet that the world around it had changed. It bought 3D Hubs—and with it, a different answer to the scaling problem.

Proto Labs acquired 3D Hubs, Inc., an online manufacturing platform that gave customers on-demand access to a global network of about 240 premium manufacturing partners. Proto Labs positioned the combination as the most comprehensive digital manufacturing offer for custom parts: keep its fast, tightly controlled in-house capabilities, but add a partner network to cover jobs that didn’t fit inside its existing “envelope”—different processes, different specs, different economics. Just as importantly, the network created a wider set of pricing and lead-time options for customers who didn’t always need “fastest possible,” but did need “right fit.”

The price tag reflected how strategic the shift was. Proto Labs paid $280 million at close—$130 million in cash and $150 million in Proto Labs stock—with up to $50 million more tied to hitting financial targets in 2021 and 2022.

3D Hubs, founded in Amsterdam in 2013, had already produced more than 6 million parts across CNC machining, 3D printing, injection molding, and sheet metal fabrication. And while it began life with “3D printing” in the name, by the time Proto Labs bought it, it was really a broad custom manufacturing platform.

The deeper meaning of the deal wasn’t just the capabilities list. It was the business model.

For two decades, Proto Labs’ identity had been vertical integration: own the machines, run the factories, control the outcome. With Hubs, it leaned into a hybrid approach—what became “Factory” plus “Network.” Some parts would still be made inside Proto Labs facilities. Others would be sourced through approved partners around the world. In 2024, that network business would be rebranded as Protolabs Network, making the shift official in the brand, not just the org chart.

It was a smart expansion of the product promise: if Proto Labs couldn’t make it quickly and well inside its own four walls, it could still be the front door—and route the job to someone who could.

But the same period made one thing uncomfortable to ignore: competition wasn’t slowing down. It was accelerating.

Xometry, the marketplace rival Proto Labs had watched rise through the late 2010s, went public on June 30, 2021, raising $325 million. Its reported revenue scale and growth made the contrast hard to miss. While Xometry was still posting roughly high-teens to around 20% year-over-year growth in recent periods, Proto Labs’ revenue momentum had largely flattened. From its record high, Proto Labs’ stock price had fallen by more than 80%, a brutal market verdict on the idea that being the category inventor guaranteed you’d remain the category winner.

And then came a warning shot from a different corner of the industry.

Chicago-based Fast Radius—a company that talked like a cloud-software platform for manufacturing—went public via SPAC on February 7, 2022, trading as FSRD on the Nasdaq. Less than a year later, it filed for bankruptcy. After the collapse, Fast Radius won court approval to sell its digital manufacturing business out of bankruptcy to a SyBridge Technologies affiliate in a deal worth $17 million, including $13 million in cash and the assumption of liabilities.

Fast Radius was the reminder that in digital manufacturing, the story is never enough. You can spend hundreds of millions building a “platform,” but if the unit economics don’t work, the market eventually collects the bill.

Proto Labs had plenty of challenges—slowing growth, intensifying competition, a shifting model—but it had something Fast Radius didn’t: a business that, whatever the turbulence, remained profitable and cash-generative. In the next phase of the category, that difference would matter more than hype ever could.

X. Recent Inflection: Leadership Change and Transformation (2023–Present)

In May 2025, Proto Labs announced another leadership transition. The Board appointed Suresh Krishna as President and Chief Executive Officer—and added him to the Board—effective immediately. Krishna most recently served as President and CEO of Northern Tool + Equipment, a manufacturer and retailer of tools and commercial equipment.

Chairman Gawlick framed the hire as building on early momentum: “Protolabs has started the year strong, and we are pleased to welcome Suresh as the Company's new CEO. With a 30-year track record of overseeing profitable growth and shareholder value creation at manufacturing companies, we are confident that he has the right skills and experience to build on the Company's positive momentum. He will take Protolabs to the next level by growing our customer loyalty and share, accelerating the execution of our production expansion initiatives and continuing to drive profitable growth through our unique digital manufacturing model.”

Krishna positioned the opportunity in market-sized terms: “I'm honored to join Protolabs as its next CEO. This is an important time as the Company works to expand its offerings and gain a larger share of the $100 billion digital manufacturing market.”

He came in with a résumé built for operational scale. Before Northern Tool + Equipment—where he served as president and CEO from April 2020 to November 2024—Krishna held senior roles at Sleep Number Corp., Polaris Inc., UTC Fire & Security, and Diageo. Across those stops, he developed a reputation for operational transformations, supply chain optimization, and building customer-centric cultures.

And he was clear about what he sees as Proto Labs’ edge: “Protolabs has an amazing team, best-in-class production times and a key competitive advantage as the only digital manufacturer that combines in-house digital manufacturing with a network of manufacturing partners.”

So far, the numbers have supported the “momentum” narrative. In the third quarter of 2025, Proto Labs reported record revenue of $135.4 million, up 7.8% from $125.6 million in the third quarter of 2024. Revenue fulfilled through its digital factories was $105.3 million, a 4.9% increase year-over-year.

The quarter before that looked similar. In late July, the company reported a second-quarter revenue record of $135.1 million—up 7.5% year-over-year and ahead of expectations.

Proto Labs served 21,252 customer contacts in that quarter. Revenue per customer contact rose 14.1% year-over-year to $6,370.

Krishna’s read on the early returns was optimistic, but measured: “I am very encouraged by the progress we've made over the last two quarters—we have significant momentum into year-end. While it's still early, my short time here has strengthened my confidence that our current strategy—delivering high-quality, custom parts throughout the product lifecycle, from prototyping to production—is the right one. Together with our teams, I am focused on accelerating profitable growth, and positioning Protolabs for long-term shareholder value creation.”

Zooming out, the scale of what Proto Labs has built is still striking. The company serves about 50,000 customers per year. Having entered prototyping more than 25 years ago, it now counts about 85% of the Fortune 500 as customers, according to Krishna, and ships an average of 5 million parts per month. Proto Labs, he says, has become “the fastest prototyping company through digital manufacturing.” In some cases, “If you upload a drawing today, we can even ship the parts same-day.”

But his real emphasis is on what comes next. Proto Labs is already great at prototyping. The bigger prize is to become great at production too—and to integrate its services so customers don’t have to leave the platform when they move from early prototypes to real manufacturing runs.

XI. The Technology and Operations Deep Dive

To really understand Proto Labs, you have to see the business the way its customers see it: as a workflow that starts with a CAD file and ends with a box of parts—without the usual days of back-and-forth in between.

It starts at protolabs.com. An engineer uploads a 3D CAD model in common formats like SolidWorks, Pro/E, or STEP. From there, Proto Labs’ custom software reviews the file and returns an interactive quote that includes pricing and design-for-manufacturability analysis.

That quoting engine is the center of gravity. It doesn’t just calculate a price—it evaluates whether the part can actually be made with the chosen process, and it flags the changes that will make it cheaper, faster, or more reliable to produce. And because Proto Labs runs the machines that make many of these parts, it can deliver unusually specific, consistent DFM feedback through a UI that’s built for engineers, not procurement.

As the company expanded into its partner-based model, software became just as important on the sourcing side as it was on the factory side. In the second quarter, Proto Labs Network gross margin was 35%, up from 32.8%, driven by AI-powered pricing and sourcing algorithms.

Physically, Proto Labs is still very much a real manufacturer, not just a website. Its headquarters are in Maple Plain, Minnesota, with Minnesota-based manufacturing facilities in Plymouth, Brooklyn Park, and Rosemount, plus additional facilities in Nashua, New Hampshire and Cary, North Carolina. Outside the U.S., it has manufacturing facilities in England and Germany, alongside a supplier network of 250 manufacturing partners around the world.

Underneath the software layer, the offering spans four core manufacturing processes:

Injection Molding: Proto Labs’ Injection Molding product line uses 3D CAD-to-CNC machining technology to automate mold design and mold manufacturing. Those molds are then used to produce custom plastic and liquid silicone rubber parts, along with over-molded and insert-molded parts, on commercially available equipment. This product line works best for on-demand production, bridge tooling, pilot runs, and functional prototyping.

CNC Machining: Computer-controlled milling and turning for metal and plastic parts.

3D Printing: Multiple additive technologies including stereolithography, selective laser sintering, direct metal laser sintering, and Multi Jet Fusion.

Sheet Metal: Laser cutting, punching, forming, and bending operations.

In typical ranges, Proto Labs produces small batches of 3D-printed parts in about a week or less, CNC-machined parts in a few days, and injection-molded runs—from a few dozen parts up to much larger quantities—anywhere from about a day to a couple of weeks, depending on the job.

XII. Business Model and Unit Economics

Proto Labs’ business model has always lived in a weird, powerful middle ground: it’s a real, capital-intensive manufacturer that tries to behave like a software company. That hybrid shows up most clearly in the financials—and it’s why investors have never quite known whether to value it like a job shop or like a tech platform.

In 2024, gross margin was 44.6% of revenue, up slightly from 44.1% in 2023. For manufacturing, that’s unusually high. Traditional job shops often live in the 20–30% range. Proto Labs earns a premium because its software automation strips labor out of quoting and process planning, and because a meaningful portion of customers are willing to pay extra for speed and certainty.

Profitability held up, but not without pressure. Adjusted EBITDA was $78.3 million, or 15.6% of revenue, compared to $83.2 million, or 16.5% of revenue, in 2023.

The revenue model itself is straightforward and very “transactional”: customers pay per order, with price driven by part complexity, material, quantity, and lead time. The speed lever matters a lot—faster delivery commands a premium—so the business naturally segments customers between those who need parts urgently and those who can trade time for cost.

In 2024, Protolabs served 51,552 customer contacts, and revenue per customer contact increased 3.1% year-over-year to $9,716.

One of Proto Labs’ enduring strengths is that it throws off real cash. As of December 31, 2024, it had $120.9 million in cash and investments and zero debt. It generated $77.8 million in cash from operations in 2024, up from $73.3 million in 2023, and returned $60.3 million to shareholders through repurchases—about 88% of free cash flow. On February 4, the board approved a new $100 million share repurchase program.

The newer “Factory + Network” model adds another layer to the unit economics. Factory orders—made inside Proto Labs’ own facilities—tend to carry higher gross margins, but they require ongoing capital investment in machines, tooling, and capacity. Network orders—fulfilled by partners—tend to carry lower gross margins, but they’re far less capital-intensive and they expand what Proto Labs can offer without building it all in-house.

As the company puts it: no other company in the digital manufacturing services space can match the margin profile of its combined Factory and Network model.

XIII. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-High

The barriers to entry are uneven. Opening a machine shop doesn’t take Silicon Valley money. But building what makes Proto Labs feel different—the software that automates quoting, DFM feedback, and the handoff into manufacturing—takes years of engineering work and a lot of accumulated data. The more credible threat, then, isn’t a traditional shop “going digital.” It’s a well-funded startup that starts with software and then layers manufacturing capacity or a supplier network on top.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low-Moderate

Proto Labs mostly buys commoditized inputs: plastic resins, metal stock, and commercially available equipment like CNC machines from major manufacturers such as Haas. No single vendor has the company pinned. If a supplier gets too expensive or unreliable, Proto Labs can typically source elsewhere.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate-High

This is where the pressure shows up in the day-to-day. Customers can comparison-shop in minutes. Proto Labs, Xometry, Fictiv, and others all offer instant quoting, which makes price and lead time unusually transparent.

Even the common question—“is Protolabs cheaper than Xometry?”—doesn’t have a single answer. Pricing swings based on geometry, quantity, material, and how fast you need the parts. And because both platforms make it so easy to upload a file and get a quote, the easiest move for customers is also the most rational: run the comparison.

Switching costs are low. CAD files travel. Long-term contracts are rare. If someone else is faster, cheaper, or simply has capacity today, engineers can route the next order elsewhere.

Threat of Substitutes: High

Proto Labs is also competing against “do nothing” and “do it yourself.” In-house 3D printing has gotten more practical as printers have improved and costs have fallen. Traditional machine shops have tightened turnaround times. And when quantity gets large enough, overseas manufacturing can still win on cost, even if it loses on speed.

Competitive Rivalry: High and Intensifying

Rivalry is fierce, and it’s not just about who can make a part—it’s about who becomes the default front door for custom manufacturing.

Xometry often frames its competitive set around Protolabs and Fictiv. Proto Labs brings the scale and control of its automated in-house factories. Fictiv competes with a similar idea to Xometry, but with a more curated, managed partner network.

Proto Labs’ 2021 acquisition of the 3D Hubs supplier network was its direct response to that marketplace threat. It helped the company stop turning away jobs that didn’t fit its internal “envelope,” and instead offer customers both options in one place: its own factories when speed and control matter most, and the network when flexibility matters more.

XIV. Strategic Frameworks: Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate

Proto Labs gets real leverage from software. Once you’ve built the quoting engine, the DFM logic, and the order-management plumbing, every additional order can flow through with less incremental overhead. But there’s a hard ceiling to how “software-like” the business can become. Manufacturing capacity doesn’t appear for free; it shows up as CNC machines, presses, facility space, and people to run them. And because Proto Labs competes on speed, it can’t just centralize everything in one mega-factory. It needs regional operations close to customers, which limits how much scale it can squeeze out of any single footprint.

Network Effects: Weak

Proto Labs isn’t meaningfully more valuable to you because other engineers use it. Your quote doesn’t get better because the user base is bigger, and your lead time doesn’t compress because the platform has more customers. There’s learning and data in the background, but it doesn’t create the classic flywheel you see in marketplaces where each new participant directly increases value for everyone else.

Counter-Positioning: Strong (Historically), Eroding

For years, Proto Labs’ counter-positioning against traditional machine shops was devastating: if you were an incumbent built around manual quoting, human-driven DFM review, and one-off process planning, you couldn’t just “copy” Proto Labs’ model. You’d have to rebuild your business from the inside out.

But the market found a different angle. Marketplace competitors counter-positioned Proto Labs in return: don’t own the machines, own the routing layer. Proto Labs’ 2021 acquisition of the supplier network 3D Hubs was a direct response to that shift—an acknowledgement that the next wave of competition wasn’t coming from job shops trying to become software companies, but from software companies that didn’t want the fixed costs of factories.

Switching Costs: Weak

The customer’s main asset—the CAD file—moves easily. There are no long-term contracts locking people in. And multi-sourcing is normal: engineers will upload the same design to multiple platforms, compare price and lead time, then place the order wherever the tradeoff looks best that day. Proto Labs does benefit from familiarity and trust, but that kind of stickiness is real-world, not structural.

Branding: Moderate

Proto Labs has strong recognition with product developers and engineers. It’s “Ol’ Reliable”: a clear menu of capabilities, an interface that’s easy to use, and turnaround times that are often the baseline for “fast.” That reputation matters more when parts are headed into quality- or safety-critical applications, where reliability isn’t optional.

But brand only protects you so much in a category where competitors can match quality and the buying motion is increasingly “upload, compare, decide.”

Cornered Resource: Moderate (Declining)

Proto Labs has intellectual property, with patents expiring across a wide range of years, and it owns roughly a few dozen U.S. trademarks or service marks. Historically, the more important “resource” was the proprietary quoting and design-analysis software—plus the accumulated know-how embedded in it.

The problem is that what used to be rare is becoming more common. AI and machine learning are pushing these capabilities toward commoditization, and Proto Labs doesn’t have a single, unique manufacturing technology that stays exclusive over time.

Process Power: Moderate

This is one place Proto Labs still feels meaningfully differentiated. It has spent more than two decades integrating software and operations into a repeatable system—one that can take a file, interpret it, quote it, and produce consistent results at speed. That level of operational integration is hard to build quickly.

But “hard” isn’t “impossible.” Given enough capital and talent, competitors can assemble comparable workflows—and marketplace players can sometimes sidestep the hardest parts by pushing production into partner networks.

Overall Assessment: Proto Labs’ strategic power has faded as digital manufacturing matured and well-funded competitors entered. The company still has advantages—especially in speed and consistency—but the moat is thinner than it was in the IPO era.

XV. The Competitive Landscape and Market Position

Digital manufacturing didn’t stay a Proto Labs one-company show for long. Once the category proved itself—upload a file, get a quote, receive real parts fast—the market filled in with competitors that looked at the same customer pain and chose different ways to solve it.

Proto Labs and Xometry are the cleanest contrast.

Proto Labs’ default mode is still vertical integration: it runs highly automated factories and keeps the work in-house whenever it can. That structure buys something customers care about: control. Proto Labs can tightly manage quality, predictability, and turnaround because it owns the process end to end, from the quoting logic all the way through shipping. Over time, though, it also acknowledged the limits of being bounded by your own walls. That’s why it expanded into a network model too—most notably through the 3D Hubs acquisition—so it could take on jobs that don’t fit its internal capabilities and still keep Proto Labs as the front door.

Xometry goes the other direction. Instead of owning the machines, it owns the routing layer.

In practice, the protolabs vs xometry decision often comes down to a tradeoff: do you want the consistency of a single, highly automated manufacturer, or the sheer flexibility of a distributed network that can match your job to whoever is best positioned to make it?

Xometry (NASDAQ: XMTR): The marketplace model. Xometry connects customers to a global network of over 55,000 active buyers and 3,400 active small-to-medium-sized manufacturers. That network gives it a level of range—processes, pricing, and capacity—that’s hard for any single factory footprint to replicate. The center of the experience is its instant quoting engine, which makes the buying motion feel fast and software-native even when the manufacturing happens somewhere else.

Fictiv: The managed network model. Fictiv connects customers to a network of over 300 manufacturers across different regions, with a heavy emphasis on quality oversight—especially for complex tooling and higher-touch work. It focuses on rapid prototyping and low- to mid-volume production across CNC machining, injection molding, and 3D printing. Customers often choose Fictiv for speed and flexibility, but the premium pricing tends to make the fit strongest when quality and project management matter more than lowest cost.

Traditional Manufacturers Fighting Back: There’s also pressure from the other end of the market. Large contract manufacturers like Jabil and Flex have been digitizing their operations—potentially threatening Proto Labs from above, while marketplace platforms attack from below.

The reality is that the custom manufacturing market is enormous, and it can support multiple winners—if each player owns a distinct slice of the demand. Proto Labs remains a go-to option when speed and predictable execution are the priority. Fictiv tends to win when enterprise customers want more back-office support and oversight. And neither, at least today, matches Xometry’s breadth of options and pricing flexibility.

XVI. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

The bull case for Proto Labs starts with the simplest premise: manufacturing is still being digitized, and the shift isn’t over. The company is explicitly trying to expand its offerings and take a bigger slice of what it describes as a $100 billion digital manufacturing market—and if that market keeps moving toward “upload a file, get a part,” Proto Labs has been building for this moment for decades.

Reshoring and nearshoring add fuel. When tariffs rise, geopolitics shifts, or ocean freight gets messy, speed and geographic diversity matter more than pennies of unit cost. Proto Labs has been leaning into that angle, arguing that its mix of factory capacity plus partner network puts it in a strong position to keep serving customers even as the “where should we make this?” answer changes.

Management also points to early signs that the hybrid model is working. Customers using the combined offer grew sharply, revenue per customer expanded, and revenue tied to production use cases grew faster than prototyping—exactly the direction Proto Labs needs if it wants to be more than a prototyping specialist.

Then there’s the part investors don’t want to ignore after the last few years in tech: Proto Labs makes real money. It’s profitable and cash-generative in a category where some competitors have burned enormous amounts of capital without building sustainable economics. In a world where Fast Radius collapsed after burning through roughly $200 million, financial discipline stops being boring and starts being a competitive advantage.

And, at least recently, the top line has started to move again. The company posted record quarterly revenue of $135.1 million, up 7.5% year-over-year—evidence that the “transformation” story isn’t purely narrative.

The Bear Case

The bear case begins with the moat—because it’s clearly not what it used to be. Proto Labs helped define digital manufacturing, but the market it created has matured, and competitors have caught up on the basics. Since 2021, sales have stagnated, and from its peak, the stock has fallen more than 80%. That’s not just sentiment; it’s the market repricing Proto Labs from category-creator to one player among many.

There’s also a model risk. Xometry’s marketplace approach may prove structurally advantaged over time: less capital tied up in machines, more flexibility in capacity, and a wider menu of materials, geometries, lead times, and price points. Proto Labs’ in-house model—its original strength—also created the boundaries that “disruptor 2.0” could route around.

Competition shows up in customer acquisition costs, too. As more platforms offer instant quotes and improving turnaround times, Proto Labs’ speed premium has compressed. When “fast” becomes table stakes, differentiation gets harder and more expensive to communicate.

Finally, there’s the uncomfortable “stuck in the middle” risk: too expensive for the most price-sensitive buyers, not positioned like a mega-contract manufacturer for massive production runs, and facing the possibility that AI erodes the uniqueness of its core software advantages.

What to Watch: Key Performance Indicators

For long-term investors tracking Proto Labs’ progress, two metrics do a lot of the telling:

-

Revenue per Customer Contact: This is the clearest signal of whether Proto Labs is expanding wallet share and successfully moving customers from prototyping into production. If this rises consistently, the pivot is working. Revenue per customer contact increased 14.1% year-over-year to $6,370.

-

Gross Margin: With pricing pressure rising, gross margin is the lie detector for the automation advantage. Holding strong suggests software and process still matter. Sustained compression suggests the work is commoditizing.

XVII. Lessons for Founders, Operators, and Investors

The Proto Labs story leaves you with a handful of lessons that apply well beyond manufacturing.

The Power and Limits of Software + Atoms Businesses

Larry Lukis’s original insight—that software could “eat” manufacturing—turned out to be right. Proto Labs built a profitable engine by automating work that competitors still did by hand: quoting, design-for-manufacturability checks, and the handoff from a CAD file to machine instructions.

But atoms don’t behave like bits. Machines cost money. Capacity can’t be spun up instantly. And if your promise is speed, you don’t just need more software—you need physical capability close enough to customers to deliver on the timeline. Software creates leverage, but it doesn’t repeal geography, physics, or capital intensity.

First-Mover Advantage Can Erode Quickly

Proto Labs had a long head start in digital manufacturing. It proved the demand and taught engineers a new expectation: upload, quote, order.

And once that expectation existed, others rushed in. The underlying processes were standard. Competitors could build fast quoting. And customer loyalty, while real, wasn’t cemented by contracts or high switching costs. In a world where it takes minutes to upload the same CAD file to three platforms, the lead you earned over a decade can shrink faster than you think.

Vertical Integration vs. Marketplace Models

The central strategic debate in the category is still open: is it better to own the factory, or to own the routing layer?

Proto Labs bet on vertical integration—control, consistency, and speed from its own facilities—then later added a network to expand what it could offer. Xometry started from the opposite premise: don’t own the machines, own the coordination. Both models can win business. Both have tradeoffs. And the market hasn’t delivered a final verdict on which one becomes the dominant shape of digital manufacturing.

Unit Economics Matter

Fast Radius was the cautionary tale: big vision, enormous investment, and then a bankruptcy sale for a fraction of what went in. It’s the cleanest reminder that in manufacturing, storytelling doesn’t matter if the economics don’t work.

Proto Labs has had its own challenges—growth slowing, competition intensifying—but it has consistently generated cash and returned capital to shareholders. In a capital-heavy industry, that discipline isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s survival.

When Founder Vision Needs Professional Management

Lukis made an unusually self-aware move early: he brought in Brad Cleveland to run the company so he could focus on the technical core. Later, the board leaned on seasoned operators like Vicki Holt and, more recently, Suresh Krishna to scale and reshape the business as the market evolved.

The broader lesson is simple: founders don’t have to do every job. The best outcomes often come when the inventor of the model recognizes what the next stage demands—and hires leadership that can carry the company there.

XVIII. Epilogue: The Future of Digital Manufacturing

By 2025, Proto Labs was sharpening its strategy around a simple idea: don’t just win the first prototype. Stay with the customer all the way to end-use production. That means serving not only the engineer trying to get a first part in hand, but also the buyers and procurement teams who show up when a design becomes a real manufacturing program.

As Suresh Krishna put it:

"While it's still early, my short time here has strengthened my confidence that our current strategy—delivering high-quality, custom parts throughout the product lifecycle, from prototyping to production—is the right one. Together with our teams, I am focused on accelerating profitable growth, and positioning Protolabs for long-term shareholder value creation."

Zoom out, and the direction of the whole industry is pretty clear. Every manufacturer is being pulled toward software—because customers now expect manufacturing to behave like the internet. AI is already changing how design feedback gets generated, how quotes get built, and how work gets routed through increasingly complex supply chains. At the same time, sustainability and resilience pressures are making “make it closer to home” feel less like a slogan and more like a requirement. And the startup ecosystem keeps launching new takes on the same promise Proto Labs pioneered: upload a file, and manufacturing becomes simple.

So the open question isn’t whether digital manufacturing wins. It’s who wins it.

For Proto Labs, reclaiming a true growth trajectory will come down to execution: proving its hybrid Factory + Network model can deliver both control and breadth, and proving it can graduate from being the gold standard for prototypes into being a trusted partner for production. That’s where the market is larger, the customer relationships are stickier, and the stakes are higher.

The company Larry Lukis started in a Minnesota garage helped create a category that changed how products get developed. That part is settled history. What isn’t settled is the ending—whether the pioneer can reinvent itself for the next era of digital manufacturing, or whether it ultimately becomes the reference point that made everyone else possible.

"We are great at prototyping, but we can become great at production," Krishna says.

The story continues.

XIX. Further Reading and Resources

If you want to go beyond the narrative and dig into how Proto Labs actually works—its economics, its strategy shifts, and how competitors describe the same market—these are the most useful places to start.

Essential Documents for Deeper Research:

-

Proto Labs S-1 IPO Filing (2012) - The cleanest, most detailed snapshot of the original business model: how quoting worked, who the customers were, and why Proto Labs believed it could scale.

-

Larry Lukis Founder Interviews - The best primary-source material on the early “software-first manufacturing” thesis and what he was trying to automate.

-

"Makers" by Chris Anderson - A broader lens on why digital tools changed product development—and why faster iteration became such an advantage.

-

Xometry S-1 (2021) - The clearest articulation of the marketplace alternative: how a network model competes with a factory-owned model.

-

Proto Labs Annual Reports (2012–2024) - A year-by-year view of the company evolving: new services, acquisitions, leadership changes, and how the story to investors shifted over time.

-

Q4 2024 and Q3 2025 Earnings Calls - The most direct window into current priorities, what management says is working, and what they’re trying to fix next.

-

Fast Radius Bankruptcy Filings - A sobering counterexample: what happens when a “platform” story runs ahead of the underlying economics.

-

"The Innovator's Dilemma" by Clayton Christensen - A useful framework for thinking about Proto Labs’ core challenge: defending a category it helped create while the rules of that category keep changing.

-

Industry Reports on Additive Manufacturing - Helpful for market sizing, technology trends, and understanding where 3D printing is truly winning versus staying niche.

-

Hamilton Helmer's "7 Powers" - A practical way to pressure-test the moat: what advantages are real, which ones are fading, and what could still compound from here.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music