PRA Group Inc.: From Norfolk Startup to Global Debt Collection Giant

I. Cold Open & Episode Roadmap

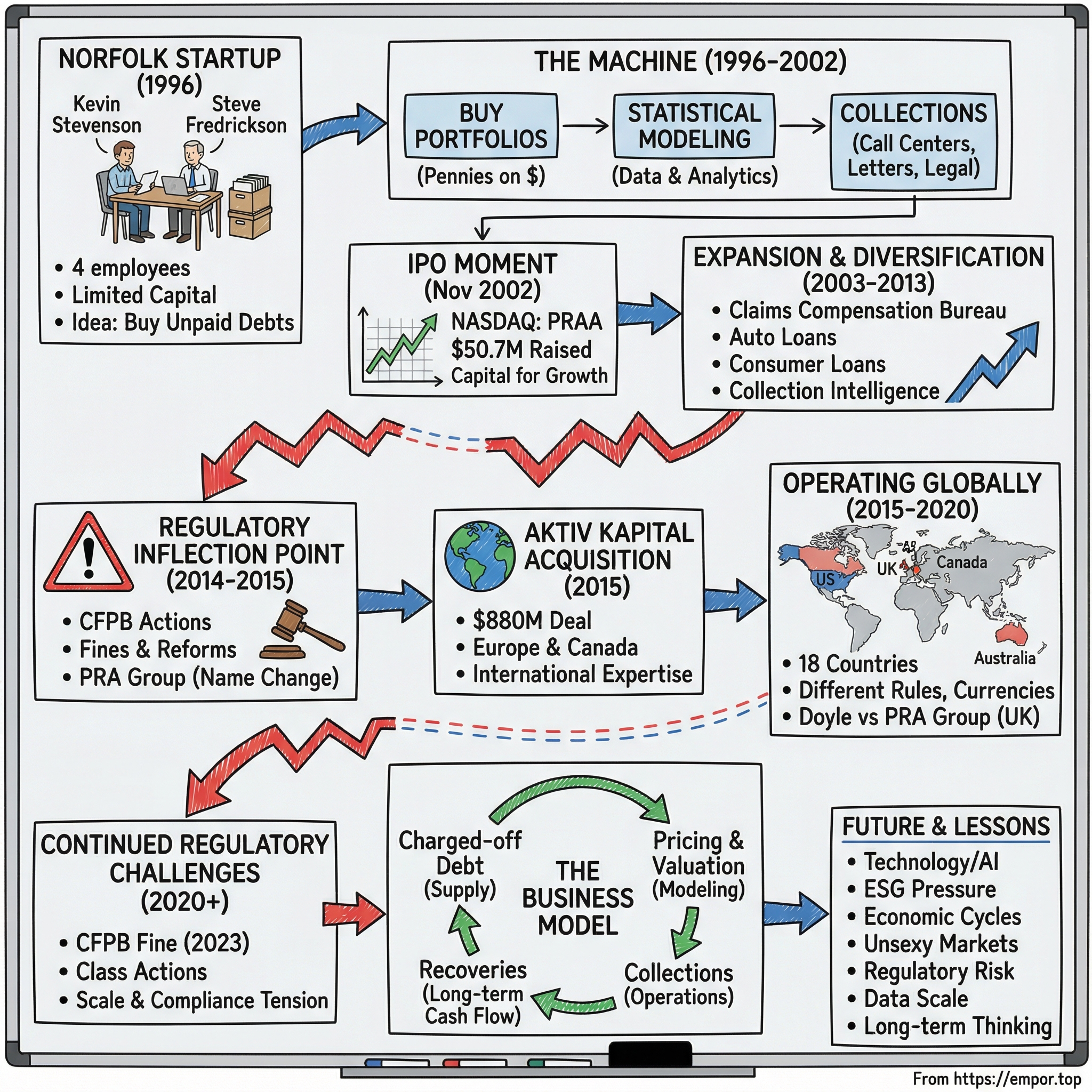

Norfolk, Virginia. March 1996. A cramped office. File boxes stacked like furniture. A handful of desks, and not much else.

Kevin Stevenson and Steve Fredrickson have just walked away from stable jobs at Household Finance, one of America’s oldest consumer lenders. They’ve got four employees, a limited pool of capital, and a thesis that most of the financial world would’ve called unglamorous on a good day—and predatory on a bad one.

They want to buy other people’s unpaid debts.

Not collect for banks as an outsourced vendor. Not run a call center for a fee. Actually purchase defaulted accounts outright—often for pennies on the dollar—and then try to recover what they can from consumers who, for any number of reasons, stopped paying their bills.

So here’s the question that makes this whole story worth telling: how did two former Household Finance employees turn a four-person Norfolk startup into a global debt collection empire spanning 18 countries?

Because PRA Group sits right at the intersection of scale and stigma. Debt buying is one of the least beloved corners of American capitalism—an industry that brings to mind relentless calls, lawsuits, and people at their financial breaking point. And yet, from that tiny starting line in Norfolk, Stevenson and Fredrickson built a company that now operates across 18 countries, employs more than 3,000 people, and communicates with consumers in 12 languages while operating in 12 currencies.

To understand PRA, you have to understand the strange little marketplace it lives in.

When someone defaults on a credit card or auto loan, the original lender eventually gives up and charges it off as a loss. But the obligation doesn’t vanish. Instead, it gets sold—bundled into portfolios and traded in a secondary market—where specialized firms like PRA buy those accounts at steep discounts.

The model sounds almost too clean: buy debt cheap, collect what you can, and keep the difference.

The reality is messier—and far more technical. How do you price a portfolio of tens of thousands of charged-off accounts when you don’t know who will pay, who can’t, who’s already filed bankruptcy, or who simply can’t be found? How do you build the systems to contact and negotiate with millions of people—across states, countries, and legal regimes—while staying inside a shifting web of consumer protection laws?

This episode follows PRA Group from that four-person beginning to a publicly traded, globally diversified debt-buying machine. We’ll hit the moments that defined the company: the regulatory crackdowns that forced a major overhaul, the Aktiv Kapital deal that took PRA international, and the constant tension at the heart of the business—collecting effectively while staying compliant in an industry that’s always under the microscope.

Because, at its core, PRA’s story is about the financialization of consumer distress: how unpaid bills became tradeable assets, how data and process turned collections into an industrial operation, and how a business nobody wants to talk about became a multi-billion dollar public company.

II. The Origins: Industry Context & Founding DNA (1996)

To understand what Stevenson and Fredrickson saw when they started Portfolio Recovery Associates, you first have to see the debt collection industry the way it looked in the mid-1990s.

It was, in a word, crude.

Back then, the dominant setup was the agency model. A consumer misses credit card payments. The bank tries to collect in-house for a while. After months of non-payment—typically somewhere between 90 and 180 days—the account either gets sold off or, more often, gets assigned to a third-party collection agency. That agency doesn’t own the debt. It’s a hired hand, paid a percentage of whatever it can bring in.

The incentives were exactly what you’d expect. Collect fast. Collect hard. Move on. High volume, blunt tactics, and not much reason to think beyond the next commission check.

And from the bank’s perspective, charged-off accounts were a nuisance. They didn’t want the reputational risk of a messy collections operation, and they didn’t have the specialized machinery to squeeze value out of portfolios full of wrong numbers, missing documentation, bankruptcies, and people who’d moved three times since opening the account.

Stevenson and Fredrickson knew this world intimately. At Household Finance—founded in 1878 and one of the original architects of American consumer credit—they’d watched the entire lifecycle up close: loans being made, accounts performing, and then the moment everything breaks and the paper turns “bad.”

What clicked for them was that the secondary market for distressed consumer debt wasn’t just unsavory—it was inefficient. Banks were unloading charged-off accounts for whatever price the market would give them. On the other side were often undercapitalized collection shops that didn’t have the analytical horsepower to value portfolios with any real precision. If you could get better at pricing and better at collecting, you didn’t just win accounts—you won the industry’s compounding advantage.

So in March 1996, they incorporated Portfolio Recovery Associates, LLC. Four people. Norfolk, Virginia.

Norfolk wasn’t an accident. It gave them lower costs than the major finance hubs, access to a workforce shaped by the military’s presence, and proximity to the mid-Atlantic banking corridor—close enough to do business, far enough to build cheaply.

By May 1996, just two months after forming the company, PRA bought its first portfolio of defaulted consumer debt. The model was simple to describe and hard to execute: purchase delinquent accounts from credit card issuers and other financial institutions at a steep discount, then try to recover as much of the balance as possible. The gap between what you paid and what you collected was the business.

But PRA wanted to differentiate on more than math. The 1990s collections world had a reputation for aggression—threats, deception, harassment—the kind of behavior that invited complaints, lawsuits, and regulators. Stevenson and Fredrickson pitched something different: a “customer-first” approach. Treat people with respect. Offer workable payment plans. Think in terms of long-term recoveries, not short-term intimidation.

This wasn’t charity. It was a strategy for better outcomes: fewer complaints, fewer blowups, and higher follow-through on payment arrangements.

And it became part of PRA’s early DNA—something that helped it win credibility with major issuers who cared how their former customers were handled. It would also become an uncomfortable contrast later, when regulatory actions alleged the company’s practices didn’t always match the standard it said it set.

But in 1996, the opportunity was real and expanding fast. Consumer credit was growing, charge-offs were inevitable, and sophisticated debt buying was still in its infancy.

The only question was whether a tiny startup in Norfolk could build the analytical and operational engine to scale—and survive—in one of finance’s least forgiving businesses.

III. Building the Machine: Early Growth & Scaling (1996-2002)

PRA’s first few years were less about bravado and more about learning—fast. Because buying distressed debt isn’t like buying a normal financial asset. On paper, a portfolio of charged-off credit card accounts looks clean: you pay a price, you own the receivables, you collect what you can.

In reality, it’s chaos in a spreadsheet.

Inside any portfolio, the accounts aren’t remotely equal. Some people hit a rough patch—job loss, a medical bill, a divorce—and may actually want a workable way to settle. Some are chronic non-payers who won’t engage no matter what you offer. Others have moved, filed bankruptcy, changed names, or left behind data that’s outdated or simply wrong. The hard part isn’t collecting after the purchase. The hard part is figuring out what you’re actually buying before you wire the money.

That’s where PRA started building its edge. In an industry that often priced portfolios with rough rules of thumb—percentages based on age and category—PRA leaned into statistical modeling. They tracked outcomes from prior purchases, built up internal databases, and tried to predict which accounts would produce real recoveries and which would be dead on arrival. The payoff was simple: don’t overpay for junk, and don’t miss value that less analytical buyers can’t see.

By 2000, the approach had scale behind it. PRA had purchased $1 billion in face value of debt and had become the tenth largest debt buyer in the United States. For a company that had started in 1996 with four people in Norfolk, that was a leap. It also said something about the moment: the market was still young enough that disciplined underwriting and process could rocket you into the top tier.

With more portfolios came a new bottleneck: operations. You can’t collect at scale from a single cramped room in Virginia. So PRA started building physical capacity to match its analytical ambition. In 2000, it opened a call center in Hutchinson, Kansas, adding a second engine to complement Virginia Beach. Kansas brought lower costs and a steady workforce—important in a business where the tone of a conversation can determine whether money comes in or a complaint gets filed. Back in Virginia Beach, the main call center grew to 380 collectors and supervisors, turning what had been a startup function into an industrial one.

At the same time, PRA aimed its purchasing toward the biggest, most consistent suppliers: major credit card issuers. By 2002, about half of the company’s portfolio came from issuers associated with Visa, MasterCard, and Discover. These sellers could provide larger, more standardized pools of accounts, typically with better documentation—and winning their business was also a stamp of credibility. In collections, who trusts you enough to sell to you matters.

By 2002, the footprint was enormous. PRA’s portfolio had a face value of $4.7 billion, tied to about 1.5 million individual debtors. That’s not just a big number—it’s a management problem. Each account is its own mini-case file with its own likelihood of paying, preferred channel, legal status, and next best action.

And that’s what PRA really built in these years: the machine. The technology to track and prioritize millions of accounts. The call center workflows to route the right people to the right conversations. The infrastructure to decide when a letter makes sense, when a phone call works, and when legal action is even an option. Plenty of firms understood the basic math of “buy low, collect higher.” Far fewer could operationalize it, repeatably, at scale, and within legal boundaries.

PRA could. And once you have that kind of machine, the natural next question becomes: how fast can you feed it? Public capital markets were about to offer an answer.

IV. Going Public: The IPO Moment (November 2002)

By late 2002, Portfolio Recovery Associates had built something that worked. It knew how to price portfolios better than most competitors, it had the call-center capacity to work millions of accounts, and it had earned relationships with major credit card issuers.

Now it ran into the constraint that defines this entire industry: cash.

Debt buying is brutally capital-intensive. You have to pay for portfolios upfront, and then you wait—sometimes years—for collections to show up. If you want to buy more paper, you need more capital. PRA had stretched as far as its existing capital base and credit facilities could take it. To keep feeding the machine, it needed a bigger funding source.

So PRA went to the public markets.

On November 8, 2002, the company went public on NASDAQ, raising $50.7 million by selling 3.9 million shares at $13 per share. The timing mattered. The U.S. was still climbing out of the post-dot-com slump, and just over a year removed from September 11. Investors were looking for real businesses with understandable economics and visible cash generation. PRA—unloved industry and all—fit that bill.

The IPO landed. By February 2003, the stock was trading about 60% above the offering price, a sign that public investors liked what they saw: a scalable model, strong growth, and a fragmented market where bigger players could keep getting bigger.

And then came the second act. In May 2003, PRA did another offering, but this one was largely insiders selling. The cofounders and a company officer collectively took about $12.2 million off the table—common for founders at this stage, and a reminder that “going public” isn’t just a financing event. It’s also a liquidity event.

Operationally, the listing changed PRA’s menu of options. Public equity could help fund more portfolio purchases. Stock could become currency for acquisitions. And the discipline and credibility of SEC reporting gave banks and credit card issuers more comfort that PRA was a stable, well-capitalized counterparty.

But the tradeoff was obvious: the spotlight.

As a public company, PRA couldn’t quietly operate in the shadows the way many private collectors did. Regulatory inquiries, consumer complaints, and aggressive collection practices wouldn’t just be operational issues—they’d become disclosure issues, reputation issues, and sometimes market-moving issues. The company’s “customer-first” identity would now be judged not by a mission statement, but by what happened across millions of real interactions.

For investors, the bet was clear too. PRA offered exposure to a profitable, growing business with barriers to entry and consolidation potential. It also came bundled with risks that never really go away in this line of work: regulation, reputation, and the unpredictability of collecting money from people who are already in trouble.

V. Expansion & Diversification (2003-2013)

After the IPO, PRA’s story shifted from proving the model to scaling it. The company had a machine that could buy portfolios, work them efficiently, and turn collections into cash. Now the question was how big it could get—and how many different kinds of “paper” it could run through that machine.

The playbook was straightforward: use access to public-company capital to keep buying portfolios, use stock as a credible currency, and widen the footprint. That meant expanding in two directions at once. Horizontally, PRA could pick up smaller debt buyers and consolidate a still-fragmented industry. Vertically, it could move into adjacent services where its core capabilities—finding people, contacting them, negotiating terms, processing payments—would still apply.

A good example of that vertical move came in April 2010, when PRA secured a controlling interest in Claims Compensation Bureau. CCB specialized in recovering funds and processing payments owed under class-action settlements. It wasn’t “debt buying” in the classic sense, but it lived in the same operational universe: messy data, hard-to-reach people, and the need for reliable payment processing and tracking. In other words, PRA was betting that its real product wasn’t just buying charged-off accounts. It was the infrastructure of recovery.

At the same time, PRA pushed beyond its credit-card roots. It expanded into auto loans, consumer installment loans, and other categories. That mattered because each category behaves differently. Credit cards are typically unsecured, high-volume, and heavily workflow-driven. Auto finance can involve repossession—an entirely different set of operational and legal muscles. Consumer loans vary widely depending on whether they’re secured or unsecured and who originated them. Diversifying wasn’t just about having more places to deploy capital; it was about building a broader collections toolkit.

Strategically, it did three things. It reduced reliance on any one supply source, especially credit cards. It opened up new growth lanes as competition intensified in the core segment. And it forced PRA to develop capabilities—systems, procedures, expertise—that would become essential later when the company expanded outside the U.S.

Much of the work that enabled this phase didn’t show up in splashy headlines. It was back-end investment: systems to manage workflows across millions of accounts, track compliance requirements, and improve analytical models that could decide, account by account, what to do next—call, letter, settlement offer, legal route, or nothing at all. PRA leaned into what you might call collection intelligence: using data to route the right action, at the right time, in the right jurisdiction, without tripping over regulations.

By 2013, the company wasn’t just bigger—it was established. The Federal Trade Commission’s report on the debt buying industry listed PRA among the top five debt buyers in the United States. That was more than a leaderboard placement. It was an acknowledgement that PRA had become one of the defining institutions of a newly professionalized sector.

Because that’s what this decade really was for the industry: a shift from fragmented, rough-edged operators to publicly traded, institutionally financed companies with increasingly sophisticated processes. PRA both benefited from that transformation and helped accelerate it.

But scale cuts both ways. The larger PRA became, the more visible it got—and the more every misstep could turn into a pattern. In an industry where the line between “effective” and “illegal” can be thin, operating at massive volume doesn’t just create efficiency. It creates the risk of systematic harm.

And regulators were paying attention.

VI. The Regulatory Inflection Point: CFPB Actions (2014-2015)

In the spring of 2014, PRA hit its first real wall. The New York Attorney General had been digging into the company’s collection practices, and the picture that emerged was not the tidy, “customer-first” story PRA liked to tell.

The settlement forced PRA to abandon collection on a large set of claims, overhaul key parts of how it collected, and pay a civil fine. But the bigger issue wasn’t the check they wrote. It was what the investigation implied: whatever PRA’s intentions were, at scale its system was producing outcomes regulators saw as fundamentally unfair.

The flashpoint was litigation.

Suing is the heavy artillery in collections. If a collector wins in court, it can unlock powerful tools like wage garnishment and levies on bank accounts. But the entire system is supposed to hinge on one thing: documentation. You need to be able to prove the debt is valid, the balance is right, and the person you’re suing is actually the one who owes it.

New York alleged PRA wasn’t consistently meeting that standard. The state said PRA had filed lawsuits without adequate documentation, obtained default judgments against consumers who didn’t respond, and then used those judgments to collect on debts that may not have been properly validated. Default judgments matter because they’re often less about who’s right and more about who shows up—and plenty of people never do, whether because they didn’t receive the notice or didn’t grasp what ignoring it would mean.

Then, in September 2015, the blow got bigger. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau stepped in with an enforcement action ordering PRA to pay an $8 million penalty and provide $19 million in consumer refunds. It also required PRA to stop collecting on more than $3 million in debt.

The CFPB’s allegations were broad: that PRA threatened and deceived consumers, stated incorrect balances, filed court cases without proper documentation, collected on default judgments that were obtained improperly, and sued on debts that were outside the statute of limitations—debts consumers were no longer legally required to pay.

This was a direct hit on PRA’s differentiator. The company had positioned itself as the more ethical, more professional alternative in a notoriously rough industry. Regulators were now saying the reality didn’t match the brand.

Inside PRA, this wasn’t just an expensive headache. Yes, the combined $27 million in penalties and refunds was meaningful. But the more dangerous problem was strategic. PRA’s best business depended on trust from major issuers—especially credit card companies that cared, intensely, about how their former customers would be treated after a sale. If PRA became known as a repeat offender, it wouldn’t just face more enforcement. It could lose access to the highest-quality portfolios that fed the entire machine.

So PRA responded with a full operational overhaul. It invested in new compliance systems, retrained collectors, and reworked its legal collections process to ensure documentation existed before a lawsuit was filed. This wasn’t optional. In debt buying, you can’t “growth hack” your way around compliance; eventually the regulator, the courts, and the sellers all catch up.

This period also overlapped with a public identity shift. In October 2014, the company changed its name from Portfolio Recovery Associates, Inc. to PRA Group, Inc. The new name was broader, more corporate, and less explicitly tied to collections. Whether or not the timing was intentional, the signal was clear: PRA wanted to be seen as something bigger—and more evolved—than what the old name implied.

For investors, the lesson was blunt. In debt collection, compliance risk isn’t a footnote. It’s existential. If you systematically cross the line, you don’t just pay fines—you lose the relationships and the operating freedom that make the model work at all. What PRA did next would decide whether 2014–2015 was a survivable turning point, or the beginning of a permanent ceiling on the business.

VII. The Transformative Deal: Aktiv Kapital Acquisition (2014-2015)

Even as PRA was fighting for credibility at home, management was placing a much bigger bet: don’t just fix the U.S. business—change the shape of the company.

In 2015, PRA Group acquired Aktiv Kapital, a Norway-based debt buyer and lender with operations across Europe and Canada, for $880 million. It was, by a wide margin, the largest acquisition PRA had ever done, and it instantly pushed the company beyond a primarily U.S. identity.

The logic was pretty straightforward. In the U.S., PRA’s market was getting tougher on two fronts at once. Competition was intensifying as more well-capitalized buyers chased the same portfolios, which drove up prices and squeezed returns. And regulators were getting more aggressive, which raised the cost of doing business and the consequences of doing it wrong. A broader footprint offered an escape hatch: new markets, different cycles, and different competitive dynamics.

Aktiv Kapital brought exactly that. It had built a real platform across Austria, Canada, Finland, Germany, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom—along with the local know-how to operate in each one. That matters because “debt buying in Europe” isn’t one business. It’s nine versions of the business, each with its own legal framework, consumer norms, and collection constraints.

PRA didn’t finance the deal with stock. Instead, it split the $880 million price tag into two equal parts: $435 million of corporate debt and $435 million drawn from its domestic revolving credit facility. The takeaway wasn’t complexity—it was intent. PRA wanted the scale and diversification without diluting shareholders.

But the most valuable thing PRA bought wasn’t just portfolios and contracts. It was expertise. European collections runs on different rules than the American model. Some countries impose stricter limits on how, when, and how often you can contact consumers. Statutes of limitations vary. Bankruptcy systems differ. Even the tone and cultural expectations around repayment can change from one border to the next. Building that from scratch would’ve taken years—and likely a lot of costly mistakes. Aktiv Kapital gave PRA a running start.

Of course, that kind of cross-border merger is also where deals go to die. Two corporate cultures. Two tech stacks. Multiple languages. Multiple time zones. Even with perfect intentions, integration can quietly unravel.

But by the metrics that matter in a people-and-process business, this one held together. More than one third of the colleagues who came over through the acquisition were still with PRA years later—an encouraging signal that this wasn’t a takeover followed by an exodus.

One reason it worked: the time horizon matched. Distressed debt is a patience business. You buy today, and recoveries show up over years. Companies built for short-term optics often struggle here; companies built for long-duration value tend to win. PRA and Aktiv Kapital approached the work with similar expectations, which made integration more than just feasible—it made it coherent.

Strategically, the prize was diversification. European portfolios could cushion the company against swings in the U.S. cycle. When conditions in one region tightened—fewer portfolios available, higher prices, lower returns—another region might be opening up. And when the U.S. market surged with supply during downturns, Europe could provide steadier cash flow in the meantime.

For investors, the message was clear: this wasn’t just an acquisition. It was a transformation. PRA was no longer simply a big American debt buyer trying to stay compliant. It was becoming a global platform—more complex, but also more resilient.

VIII. Operating Globally: The New PRA (2015-2020)

After Aktiv Kapital, PRA Group stopped being “a U.S. debt buyer with some international exposure” and became something far harder: a company that had to run the same core playbook across a map full of different laws, languages, and expectations about what fair collection even looks like.

That global footprint opened up new sources of portfolios and new ways to smooth out the cycle. It also meant PRA was now living with a constant reality of international operations: you can do everything right in one country and still get blindsided in another.

In 2019, that played out in the UK. A court case, Doyle vs PRA Group, clarified how British law treats statute-barred debt, effectively drawing a hard line: if no action had been taken within six years, creditors couldn’t pursue the debt. For PRA, this wasn’t an abstract legal debate. It changed how certain UK accounts could be worked and how UK portfolios were valued—an example of how a single ruling in one jurisdiction could ripple straight into strategy and financial outcomes.

The flip side of building an international platform is that, once it exists, you can keep adding to it. In 2019, PRA acquired Resurgent Holdings’ Canadian business, which the company described as creating a market-leading nonperforming loan business in Canada. It was a classic bolt-on: instead of figuring out a new market from scratch, PRA could plug an acquisition into an operation that already knew how to run multi-country portfolios.

Then, in 2020, PRA expanded into Australia, adding another major market to the footprint. Australia offered a familiar legal foundation in English common law, a sophisticated consumer credit market, and growing volumes of nonperforming loans—an attractive mix for a company built to buy, manage, and recover distressed receivables.

And then the world changed.

COVID-19 hit debt collection in ways that were both immediate and strangely contradictory. On the front end, collections slowed sharply. In many places, moratoria constrained activity, courts shut down and made litigation impossible, and widespread consumer distress made aggressive collection not just difficult, but often untenable.

At the same time, the pandemic set up unusual dynamics that could actually help recoveries in the near term. Government stimulus—enhanced unemployment insurance, direct cash transfers, and other programs—temporarily improved some consumers’ ability to resolve old obligations. And looking ahead, the economic dislocation and the eventual withdrawal of support foreshadowed the opposite effect: a future wave of defaults that would later feed the debt-buying pipeline.

Performance also started to reveal why PRA wanted diversification in the first place. Results varied by geography, and European markets generally came in ahead of internal expectations. When some regions bogged down, others held up better. That’s the core promise of a global portfolio: you’re no longer betting the entire company on one regulatory regime or one economic cycle.

What made this era so hard to appreciate from the outside is that much of the work was invisible. PRA wasn’t just buying more paper. It was trying to build a single operating system that could function across different currencies, legal standards, and cultural norms—without breaking. A complaint mishandled in Germany could trigger a different set of consequences than one mishandled in Spain. A payment plan that seemed straightforward in the UK could create problems in Sweden. To operate at scale, PRA had to make its compliance infrastructure both globally consistent and relentlessly local.

In other words: the acquisition made PRA bigger overnight. The years after were about proving it could actually run what it bought.

IX. Continued Regulatory Challenges (2020-Present)

The Aktiv Kapital deal helped PRA get bigger and more diversified. But it didn’t make the company invisible. And it didn’t make the compliance problem go away.

Even after the 2014–2015 crackdown and the investments that followed, PRA kept running into the same uncomfortable reality in the 2020s: when you operate at massive volume in a heavily regulated business, “mostly fixed” isn’t the same as fixed. The fact that issues continued to surface raised a hard question—had PRA genuinely changed how it operated, or had it simply patched the specific gaps regulators pointed to last time?

In March 2023, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau fined PRA $24 million for what it described as continued illegal debt collection practices and consumer reporting violations. Coming nearly a decade after PRA’s earlier enforcement action—and after years of stated reforms—this wasn’t just another line item. It was a signal that regulators believed the underlying problems hadn’t been fully eliminated.

The CFPB’s findings were, again, the kind that strike at the heart of trust in the model: allegations of conduct that violated consumer protection laws, despite PRA’s public posture as a more professional, compliance-focused collector. For a company that depends on credibility—with regulators, with portfolio sellers, and with courts—this was a reputational and operational setback, not just a financial one.

Then in 2024, more legal exposure arrived from a different direction. PRA paid $5.5 million to settle a class action lawsuit alleging violations of North Carolina debt collection law. Regulatory actions are one kind of pressure. Class actions are another: they’re brought by private plaintiffs, and they can bundle together claims from large groups of consumers into one high-stakes case.

So why do these issues keep showing up, even after “substantial compliance investments”? There isn’t a single clean answer, but a few forces tend to compound.

First, scale is a compliance stress test that never ends. When you’re managing millions of collection interactions, mistakes aren’t rare edge cases—they’re statistical inevitabilities. The real question becomes whether those mistakes are isolated and corrected quickly, or whether they add up to patterns that regulators view as systemic.

Second, there’s a built-in conflict between intensity and restraint. Collections organizations often run on performance metrics. If collectors feel pressure to produce, the risk rises that someone uses prohibited language, overstates what can happen next, or blurs a line the law draws sharply. Fixing that isn’t just about training modules and updated scripts. It can require changing incentives—what people are rewarded for, what gets audited, and what gets disciplined.

Third, the rules have tightened. The CFPB’s Regulation F took effect in 2021 and added detailed requirements around how collectors communicate, what they must disclose, and what they can’t do. Practices that might have lived in gray areas before became more clearly defined—and therefore easier to enforce against.

For investors, this is the core tension: the economics of debt buying depend, in part, on how effectively you can collect. But the harder you push, the more regulatory and litigation risk you invite. The long-term winners are the firms that can thread that needle consistently—collecting enough to earn attractive returns without triggering enforcement, fines, and reputational damage.

PRA’s continued run-ins with regulators suggest that finding that balance has been harder than the company—and the market—wanted to believe. And it leaves the story with an open question that still hangs over the entire industry: can a debt collector scale profitably while making compliance and consumer treatment as non-negotiable as financial performance?

X. The Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand PRA Group, you have to look past the simple pitch—buy debt cheap, collect more than you paid—and see what the business actually is day to day: a high-volume underwriting shop wrapped around a massive operations engine, where the “asset” is millions of individual consumer accounts and the payoff comes in cash flows that dribble in over years.

It starts with supply.

When a consumer stops paying a credit card, auto loan, or other obligation, the original lender will try its own collections process for a while. Eventually, the lender charges the account off and books it as a loss. But charged off doesn’t mean gone. Those accounts get bundled into portfolios and sold in a secondary market, where companies like PRA compete to buy them.

The whole game is pricing.

A portfolio might include tens of thousands of charged-off credit card accounts with a huge face value on paper. But the price PRA pays is only a sliver of that number—typically just a few cents on the dollar—because everyone involved knows the truth: a large percentage of those accounts will never pay anything.

Still, “most won’t pay” isn’t enough to run a profitable business. The winners are the firms that can predict, more accurately than everyone else, which slice will pay, how much they’ll pay, and how long it will take.

That’s why portfolio valuation is PRA’s core competency. Inside any pool of accounts, outcomes are all over the map. Some people eventually pay in full. Some settle for less. Some are in bankruptcy, where recoveries can be minimal. Many can’t be reached or won’t engage. The difference between a great deal and an expensive mistake often comes down to whether your model can forecast that distribution well enough to bid the right price.

PRA uses statistical modeling that looks at a long list of account-level factors—things like balance at charge-off, time since last payment, consumer credit attributes, geography, and the original creditor. Using historical performance on similar accounts, PRA builds estimated recovery curves: forecasts of how much cash a portfolio should generate and when that cash is likely to show up.

Then comes the second half of the business: turning predictions into payments.

Once PRA owns a portfolio, it works accounts through different channels depending on what the data suggests is most effective and appropriate. Some consumers get phone outreach where collectors try to set up payment plans. Some receive written communications. Some accounts move into legal collections, where PRA may sue to obtain a judgment that can enable tools like wage garnishment or bank account levies.

This is also where scale becomes a weapon. Many of the costs of collections are relatively fixed at the interaction level: a call, a letter, the overhead of running systems and compliance controls. Those costs don’t rise neatly with the size of the debt. As the company gets bigger and works more accounts, it can spread its infrastructure over a larger base—creating operating leverage that smaller players struggle to match.

The accounting adds another layer of complexity. When PRA buys a portfolio, it records it as an asset at the purchase price. Collections come in over multiple years, and revenue gets recognized as those collections arrive relative to what the company estimated it would collect in the future. Beat expectations and reported revenue rises. Miss expectations and the financial results take a hit.

That long collection horizon creates a weird mix of stability and uncertainty. Portfolios can throw off cash for years—sometimes much longer—so today’s revenue is partly the result of buying decisions made long ago. At the same time, every new portfolio is a fresh underwriting bet whose results won’t fully reveal themselves for years.

If PRA has a compounding advantage, it’s data. Every account it touches generates feedback on what works, what doesn’t, and under what conditions. That information loops back into pricing models and operating strategies, ideally making the next bid smarter than the last. Competitors without that history are, in theory, guessing with less signal.

And over time PRA has broadened what it does with that core capability. Beyond the main debt-buying and collection engine, it operates related subsidiaries, including Portfolio Recovery Associates (now a subsidiary under the PRA Group umbrella), PRA Receivables Management for bankruptcy accounts, PRA Location Services for auto recovery operations, and Claims Compensation Bureau for class action claims processing. Different revenue streams, same underlying skill: find the right person, communicate within the rules, and process payments reliably.

XI. Modern Era: Today's PRA Group

Today, PRA Group employs more than 3,000 people and operates across 18 countries—a long way from the four desks and file boxes in Norfolk in 1996. But to understand what PRA is now, you can’t just look at the footprint. You have to look at what it takes to compete in modern debt buying: scale, technology, and the ability to operate under a microscope.

The industry has consolidated dramatically. Where debt buying once had a long roster of smaller operators, the center of gravity has moved toward a handful of large platforms. PRA Group and its primary competitor, Encore Capital Group, sit at the top, with a long tail of regional and niche players behind them. The reasons are pretty intuitive: regulatory complexity has increased, capital is essential, and at this scale, data becomes a real advantage. If you can underwrite better and run a tighter operation, you can bid more confidently—and win more portfolios.

That’s where technology has become central to PRA’s strategy. The company has invested in artificial intelligence and machine learning to help prioritize accounts, using models to predict which consumers are most likely to respond and which accounts should be worked differently—or not worked at all. It has also leaned on automation for routine tasks, especially in compliance and communications, where consistency matters and human error gets expensive quickly.

How PRA communicates has changed, too. Phone calls still matter, but debt collection has steadily moved toward digital channels. Email, text messaging, and online payment portals now make up a growing share of activity, in part because consumers increasingly prefer them and in part because regulators have encouraged clearer, better-documented communication. The shift isn’t free—building and maintaining those systems takes real investment—but it can improve efficiency and create a cleaner record of what was said, when, and to whom.

At the same time, PRA now has to navigate a newer kind of pressure: ESG scrutiny. Institutional investors have made ESG screening more common, and debt collection carries obvious social risk. When your customers are financially distressed consumers, the question of how you treat people isn’t a brand nice-to-have. It’s a core part of reputational risk.

PRA has tried to respond with an emphasis on respectful collection practices, payment flexibility for consumers facing hardship, and transparency in communications. Whether that’s enough to satisfy ESG-focused investors is still an open question—especially given the company’s ongoing regulatory challenges.

The business itself has also evolved. Credit card debt remains important, but it’s no longer the whole story. Auto loans, consumer installment loans, and other categories now play a larger role than they did in the early years. And thanks to geographic diversification, the U.S. is still the largest segment, but it’s a smaller share of the overall enterprise than it was before Aktiv Kapital.

The macro backdrop has been supportive for debt buyers. Rising consumer debt across many developed economies has increased the potential supply of charged-off accounts. And post-pandemic delinquencies have been trending back upward in several categories, creating more purchasing opportunities for firms positioned to deploy capital.

Which brings us to the question hanging over PRA today: can it keep growing without stepping on the same regulatory landmines? The model is still compelling—operating leverage at scale, a data advantage that can compound, and countercyclical dynamics that can create opportunity when the broader economy weakens. But PRA’s history also shows the cost of getting compliance wrong. For investors, the bull case and the bear case both start in the same place: execution.

XII. Competitive Landscape & Industry Dynamics

The debt buying industry sits in a strange corner of financial services. It performs a necessary cleanup job—what happens after consumers default—while carrying enough stigma that most of the financial world would rather not look too closely. That mix of “essential” and “unloved” shapes everything about the competition.

PRA’s clearest head-to-head rival is Encore Capital Group. The two companies have grown up in parallel: both started in the U.S., both expanded into Europe, and both spent years rolling up smaller players. Together, they occupy the industry’s top tier, and that scale matters. When the biggest banks decide who gets invited to bid on large charged-off portfolios, size, capital, and track record can become their own kind of advantage.

Behind them is a long tail of smaller debt buyers and collection firms. Many survive by staying out of the biggest auctions and instead specializing—by debt type (like medical debt, student loans, or auto deficiencies) or by geography. They may not have the balance sheet or data history to go toe-to-toe with the giants on massive portfolio purchases, but in a niche where local knowledge or a specific playbook matters, specialization can beat scale.

Across the last couple of decades, consolidation has been the dominant force. The reasons are straightforward. Compliance has gotten more expensive and more complex, and that burden hits smaller operators hardest. Data advantages also compound: the more portfolios you buy and work, the more performance history you have to price the next one. And capital is table stakes in a business where you pay upfront and collect over years—an area where well-funded, publicly traded platforms have structural advantages over smaller private shops.

New entrants and fintech disruption are always discussed as the looming threat, but so far they’ve been slower to reshape debt buying than they have payments, lending, or investing. The barriers are high: regulation, capital requirements, and the brutal learning curve of valuing portfolios and running compliant collection operations at scale. Still, the possibility remains that technology-first players could eventually change how collections is done, especially as digital communication becomes the default.

If there’s one “customer” that matters most in this business, it’s the debt seller—banks, card issuers, and auto finance companies. Price matters, but it’s not the only variable. These institutions care deeply about reputational risk. If their former customers get mistreated after a sale, the blowback lands on the brand that issued the card in the first place. That makes professionalism and compliance a competitive weapon, not just a legal requirement. Buyers that can credibly demonstrate both are more likely to stay in the preferred circle of sellers.

Then there’s the cycle. Debt buying is tied to the economy in a way that can feel backward. In recessions, defaults rise and portfolio supply grows—creating more inventory for buyers to purchase. In boom times, fewer consumers default, supply tightens, and portfolio prices get bid up as buyers fight over fewer opportunities. The industry can benefit from downturns, but it can feel squeezed when the economy is humming and paper becomes scarce.

Finally, the secondary market itself has matured. Portfolios don’t always move from a bank to a single end owner. Sometimes they get resold, creating chains of ownership that can complicate documentation and consumer rights. For buyers trying to stay out of regulatory trouble, knowing exactly where a portfolio has been—and what records actually came with it—isn’t paperwork. It’s risk management.

XIII. Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Step back from the stigma and the headlines, and PRA looks like a fairly classic industrial business: it buys inputs (charged-off portfolios), runs them through a highly optimized machine (data, compliance, and collections operations), and tries to produce more cash than it paid. Strategic frameworks are useful here because they make clear what actually drives advantage—and what can break it.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

The threat of new entrants is moderate to high. The barriers are real: you need meaningful capital to buy portfolios, the operating complexity is high, and the regulatory environment is unforgiving. But if returns look attractive enough, well-capitalized financial services players can enter, and private equity has shown it will fund competitors when it sees opportunity.

The bargaining power of suppliers is high. In PRA’s world, suppliers are the banks and credit card issuers selling debt. They can choose among multiple buyers, they can demand specific documentation standards, and they can impose requirements around how consumers must be treated. PRA’s existing relationships help, but ultimately the sellers have leverage because they control the inventory.

The bargaining power of buyers—the consumers who owe the debt—is low. Once an account is sold, the consumer’s choices are limited: pay, negotiate, declare bankruptcy, or not pay and deal with the downstream consequences. That imbalance is not a side detail; it’s foundational to how the industry works.

The threat of substitutes is low. From a creditor’s perspective, there are only so many alternatives to selling charged-off accounts: keep trying to collect internally (costly and distracting), place the accounts with contingency agencies (often less efficient), or write them off and move on (leaving recoveries behind).

Competitive rivalry is high and, over time, has tended to get sharper at the top. PRA and Encore regularly go after the same large portfolio opportunities. When the biggest players are bidding against each other, prices rise and margins tighten. Consolidation reduces the number of serious bidders, but it can also concentrate competition among the remaining giants.

Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis:

Scale economies are one of PRA’s clearest strengths. The expensive parts of the business—technology infrastructure, compliance controls, analytics, and operating management—get spread across more accounts as you grow. A large platform can carry that fixed-cost base more efficiently than a smaller one.

Network effects are minimal. Debt buying isn’t a marketplace where more users attract more users. Having more accounts doesn’t create the self-reinforcing loop you’d see in a true platform business.

Counter-positioning is moderate. PRA has long claimed a more “customer-first” approach than the industry’s rougher operators, which in theory is hard for aggressive competitors to copy without changing their economics. The problem is that regulatory actions have repeatedly undercut this differentiation.

Switching costs are moderate. Sellers and buyers build familiarity: documentation standards, operational expectations, and a history of doing business together. That creates some stickiness—but portfolios are often sold through competitive processes, and switching is absolutely possible.

Branding is weak at best and often negative. Debt collection isn’t a brand-positive industry. In many cases, higher visibility simply increases reputational exposure, especially when public recognition is tied to enforcement actions or consumer complaints.

Cornered resources are moderately present. PRA’s historical performance data—how different portfolio types actually cash-flow over time—is hard for a new entrant to replicate quickly. So is deep talent in portfolio valuation and compliant collections at scale.

Process power is the other major pillar. PRA’s underwriting models, collections playbooks, and compliance systems represent accumulated learning. In this business, that institutional knowledge is the “factory.” It’s also where regulatory problems do the most damage—because they call into question whether the process is actually as controlled as it needs to be.

Overall Assessment: PRA’s moat is built primarily on scale economies and process power. Both can be durable. But neither is untouchable: competitors can consolidate into similar scale, and repeated compliance failures can weaken the very process advantage PRA relies on.

XIV. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

The debate over PRA Group is simple to state and hard to resolve: does the company’s scale, data, and diversification outweigh the industry’s inherent regulatory and reputational risk—and can management keep tightening compliance without breaking the economics?

The Bull Case:

PRA has built a real global platform, and the diversification isn’t just a slide-deck claim. With operations across 18 countries, the company isn’t forced to bet everything on one economy, one court system, or one regulator’s interpretation of “fair.” When portfolio supply tightens in one region, another can open up. When one market gets more restrictive, another may remain workable.

There’s also a long runway in the underlying input to the business: consumer debt. Credit cards, auto lending, and newer products like buy-now-pay-later all expand the pool of obligations that can eventually become charged-off portfolios. In that sense, PRA operates downstream of a broader, persistent trend—more consumer credit, more defaults, more paper for specialists to buy.

The compliance story, while messy, has had real investment behind it. Since the 2014–2015 enforcement actions, PRA has put substantial resources into infrastructure, training, and controls. The 2023 penalty was a serious hit, but it didn’t change the basic fact that the company has kept operating and has continued to commit to improving.

Then there’s the core technical advantage: underwriting and collections execution. PRA has decades of portfolio performance data—what actually happened when it bought certain types of accounts under certain conditions—and it has invested in analytics and machine learning to translate that history into better pricing and better sequencing of collection actions. That is hard for a new entrant to copy quickly.

Consolidation can also play to PRA’s strengths. As the regulatory burden rises and the cost of “getting it wrong” increases, smaller operators can get squeezed out. When that happens, scale players like PRA can pick up market share—or buy portfolios and businesses—without having to win every battle in the most competitive auctions.

Finally, debt buying has a feature most industries don’t: long-lived cash flows. Once PRA buys a portfolio, collections tend to arrive over years, following an expected curve. That durability can make cash generation more predictable than businesses that rely on constantly closing new sales.

The Bear Case:

The biggest bear argument is the most obvious one: the compliance problems haven’t fully gone away. A major penalty in 2023, long after the company said it had overhauled its practices, raises the possibility that the issue isn’t a few fixable gaps—it’s something deeper in the operating culture or incentive structure. If regulators remain unconvinced, profitability doesn’t just get pressured; the whole model gets constrained.

Reputation is also a permanent headwind. Debt collection is disliked by consumers by default, and that dislike translates into political and regulatory energy. On top of that, ESG-focused capital may avoid the space entirely, which can raise the cost of financing and keep the sector under a harsher microscope.

There’s also real downside risk in a downturn. Recessions can increase future portfolio supply, but they can simultaneously reduce what consumers can pay on portfolios you already own. In a severe enough contraction, that can mean portfolio underperformance and write-downs that hit the balance sheet.

Legal and policy shifts are another structural risk. If bankruptcy rules change in ways that strengthen consumer protections or expand eligibility, recoveries could fall across categories. The details matter, but the direction of travel is what worries bears: more protection for consumers generally means less cash for debt buyers.

Competition is not static either. If the business becomes more compliance-heavy—more like regulated servicing than the “Wild West” caricature—larger financial services firms with mature compliance organizations may decide the space is finally attractive enough to enter.

And then there’s the longer-term threat to PRA’s moat: technology. If AI and automation become standardized across the industry, the process advantage of “we’re better at collections” could shrink. In that world, pricing gets more efficient, returns compress, and scale becomes less differentiating than it used to be.

Key Metrics to Watch:

For investors tracking whether the bull case is winning or the bear case is taking over, three signals matter most.

First, cash collections versus expectations. PRA constantly forecasts how much it expects to collect from portfolios. When actual cash beats those expectations consistently, it suggests good pricing discipline and strong execution. When it misses repeatedly, it can mean the company overpaid for portfolios, collections are getting harder, or both.

Second, Europe versus the Americas. Diversification is only valuable if regions truly behave differently. If both move together—up and down at the same time—then complexity increases without delivering the stabilizing benefit the Aktiv Kapital strategy promised.

Third, regulatory actions and settlements. Not just the dollar amount, but the pattern: how often problems surface, what kind of conduct is involved, and whether the issues look like isolated mistakes or repeat themes. In this business, that’s the clearest window into whether compliance improvements are actually sticking.

XV. What Makes This Company Interesting

PRA Group’s story matters for reasons that go way beyond debt collection. It’s a lesson in how value gets created in markets most people avoid, what happens when regulation becomes a defining force in strategy, and how hard it is to scale an operation where the “product” is millions of human interactions.

Start with the obvious paradox: this is a multi-billion dollar company built in one of finance’s least appealing corners. That’s the point. When Stevenson and Fredrickson started buying distressed debt in 1996, the space was full of inefficiency and low expectations. Few sophisticated operators wanted in. And whenever smart capital refuses to show up, prices get sloppy, processes stay crude, and the disciplined player has room to compound.

But PRA’s rise also shows what it costs to operate in a business that lives under permanent scrutiny. The company repeatedly emphasized better consumer treatment, yet repeatedly faced regulatory actions alleging misconduct. You can read that a few ways: as proof that controlling an organization at this scale is brutally hard; as evidence of the constant pull between performance and restraint; or as a sign that leadership messaging and day-to-day execution can drift apart. Whatever conclusion you reach, the pattern itself is the story.

Then there’s the global platform. Collecting across 18 countries sounds like a neat brag until you unpack what it means: different languages, different court systems, different statutes of limitations, different consumer norms, and different definitions of what “fair” looks like. Very few firms can do that well, and if you can, it becomes a real organizational asset. It also becomes a permanent management challenge, because consistency is exactly what’s hardest to maintain when the rules change every time you cross a border.

At the center of it all is the tension the industry can’t escape: maximizing recoveries while treating consumers fairly. Debt collection exists because some people don’t pay what they owe. The toolkit ranges from reminders and payment plans to litigation. Drawing the line is hard. Enforcing it—across thousands of employees and millions of interactions—is harder.

And yet, as uncomfortable as it is, the function is part of the credit system’s plumbing. Someone has to handle defaulted debt. If nobody did, losses would simply get priced back into higher borrowing costs for everyone. That doesn’t make collections popular, but it does make it economically consequential.

Finally, PRA is a case study in how technology industrializes a messy human business. Early debt buying leaned on relationships and gut feel. Modern debt buying runs on models, predicted recovery curves, and increasingly automated decisions about who to contact, when, and how. PRA’s edge—when it has one—has often come from being early to treat debt buying less like a hustle and more like an underwriting and operations discipline.

XVI. Epilogue & Future Outlook

So where does PRA Group go from here? If the last three decades were about building scale—and then learning, sometimes painfully, how to operate that scale under a microscope—the next decade will be shaped by forces PRA can influence and forces it simply has to absorb.

Start with the raw material of the business: consumer debt itself. Credit cards and auto loans will keep producing charge-offs. But the mix of what consumers owe is changing. Buy-now-pay-later has grown into a mainstream way to finance everyday purchases, creating a newer stream of potential defaults. Crypto lending added another, stranger category—one where the underlying assets, counterparties, and legal frameworks don’t always look like traditional consumer credit. How these debts behave once they go bad, and whether PRA can underwrite and collect on them with the same discipline it built in more familiar categories, is still an open question.

Technology is also pushing the industry forward—whether it wants to move or not. Artificial intelligence and automation are already reshaping how collectors prioritize accounts and communicate with consumers. Natural language tools could make automated outreach sound more human. Predictive models will keep getting better at deciding which accounts are worth working and which aren’t. But the more decisions that get handed to algorithms, the more the compliance stakes rise. If an automated system nudges too aggressively, uses the wrong wording, or targets the wrong consumer, the “mistake” can scale instantly—and regulators will want to know who’s accountable: the person, the process, or the model.

Then there’s the variable no one in this business ever escapes: regulation. The enforcement climate tends to swing with political cycles. Some administrations push consumer protection agencies to expand restrictions and pursue aggressive oversight; others pull back. For PRA, that means building for the strict version of the world even when the permissive version shows up. In other words, compliance can’t be a posture that changes with the headlines. It has to be an operating system that holds up under the toughest likely rulebook—and still allows the company to make money.

Internationally, expansion is still on the board. Asia and Latin America offer growing consumer credit markets and, in some places, less mature debt buying ecosystems. That can look like opportunity. It can also look like a fresh set of risks: unfamiliar legal systems, thinner credit bureau data, and political uncertainty that’s harder to price into a portfolio model.

Layered on top of all of this is capital—and the growing role of ESG screens. Debt collection is one of the hardest businesses to sell as “socially positive,” and institutional investors increasingly care about how a company makes its returns, not just whether it makes them. If ESG pressure tightens access to capital for controversial industries, it could reshape the economics of debt buying. The open question is whether the industry can evolve enough to meet investor expectations without hollowing out the very cash flows that make it attractive.

Which lands us on the question that hangs over PRA—and really, over the entire sector. Can debt collection ever be truly ethical and truly profitable at the same time? The business is built on pursuing people who are already under financial strain. Even a compliant, respectful operation is still trying to extract value from distress. You can improve behavior, tighten rules, and reduce harm. But the moral complexity doesn’t disappear.

XVII. Lessons for Founders & Investors

PRA Group’s path from a four-person Norfolk startup to a global corporation leaves a set of lessons that apply well beyond debt buying.

Find unsexy markets. Stevenson and Fredrickson built a billion-dollar company in a business most founders wouldn’t touch. That was the advantage. When an industry is ignored or looked down on, it’s often inefficient, fragmented, and under-optimized. PRA stepped into that gap, brought discipline to pricing and operations, and found steady demand that flashier sectors can’t always count on.

Regulatory risk can be existential. PRA’s regulatory history is a reminder that in sensitive industries, compliance can’t be a binder on a shelf. It has to be a culture. Scripts, policies, and training help—but if incentives and norms still reward “results at any cost,” violations aren’t a surprise. They’re the outcome.

Scale matters in data businesses. Portfolio valuation gets better when you’ve seen more portfolios. The more historical performance data you have, the more precisely you can price new paper, forecast recoveries, and decide how to work accounts. At enough volume, that turns into a durable advantage: better bids, better returns, and more deals won.

Geographic diversification reduces cyclicality in economically sensitive businesses. Defaults rise and fall with the economy, but they don’t rise and fall everywhere at the same time. By operating across multiple countries, PRA reduced the risk of being overexposed to one cycle, one court system, or one regulatory climate.

Culture clash matters in M&A. The Aktiv Kapital integration worked in part because the two organizations shared a long-term approach and compatible ways of operating. Many cross-border deals fail not because the spreadsheet was wrong, but because the people and processes never truly merge. Partner fit is not soft—it’s decisive.

Reputation recovery is possible but it’s slow, and it’s never guaranteed. PRA’s enforcement actions damaged trust with consumers, regulators, and the institutions that sell portfolios. Rebuilding that standing has taken years and remained a work in progress. Still, the company survived and continued operating at scale, showing that reputations can be repaired—but only through sustained effort.

Long-term thinking is essential in businesses with multi-year asset durations. A portfolio bought today can produce cash for years. If you optimize aggressively for the quarter—by overbidding, pushing too hard on collections, or cutting compliance corners—you can destroy the economics of the asset and invite consequences that last far longer than any reporting period. The winners are the ones built to think in years, not quarters.

XVIII. Key Resources and Further Reading

If you want to go deeper on PRA Group—and on the debt buying industry that made it possible—there are a handful of sources that show you what’s really going on beneath the headlines.

Start with PRA Group’s SEC filings. The annual 10-Ks and proxy statements, from the 2002 IPO onward, are the most detailed public record of how the business works: what kinds of portfolios the company buys, how collections are performing, how management thinks about risk, and how regulatory developments filter into operations.

Then read the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau consent orders from 2015 and 2023. They’re direct, specific, and hard to ignore—essential for understanding the compliance failures regulators alleged and the standards PRA has been expected to meet.

For broader industry context, the Federal Trade Commission’s 2010 report, "Repairing a Broken System: Protecting Consumers in Debt Collection Litigation and Arbitration," lays out how debt collection litigation works, why default judgments matter, and where the system breaks down.

For a narrative view of the ecosystem, Jake Halpern’s "Bad Paper: Chasing Debt from Wall Street to the Underworld" is the most readable window into the culture and incentives of debt buying. It isn’t a PRA biography, but it makes the world PRA operates in feel real—messy data, gray-market behavior, and the human consequences that sit underneath the spreadsheets.

On the legal side, the UK case Doyle vs PRA Group (UK) Ltd (2019) is a key reference point for statute-barred debt in the UK, with real implications for how portfolios get valued and worked in that market.

And if you want the company’s own framing—how it wants investors to understand its strategy and positioning—PRA Group’s investor presentations on its investor relations site are the best place to look.

The story of PRA Group is ultimately about the financialization of consumer distress and the industrialization of debt collection. From four people in Norfolk to more than 3,000 employees across 18 countries, it’s American capitalism at its most pragmatic—and most controversial. Whether the next chapter reads like profitable growth, regulatory redemption, or a cautionary tale will hinge on decisions made in boardrooms and courtrooms, and on millions of conversations between collectors and consumers in the years ahead.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music