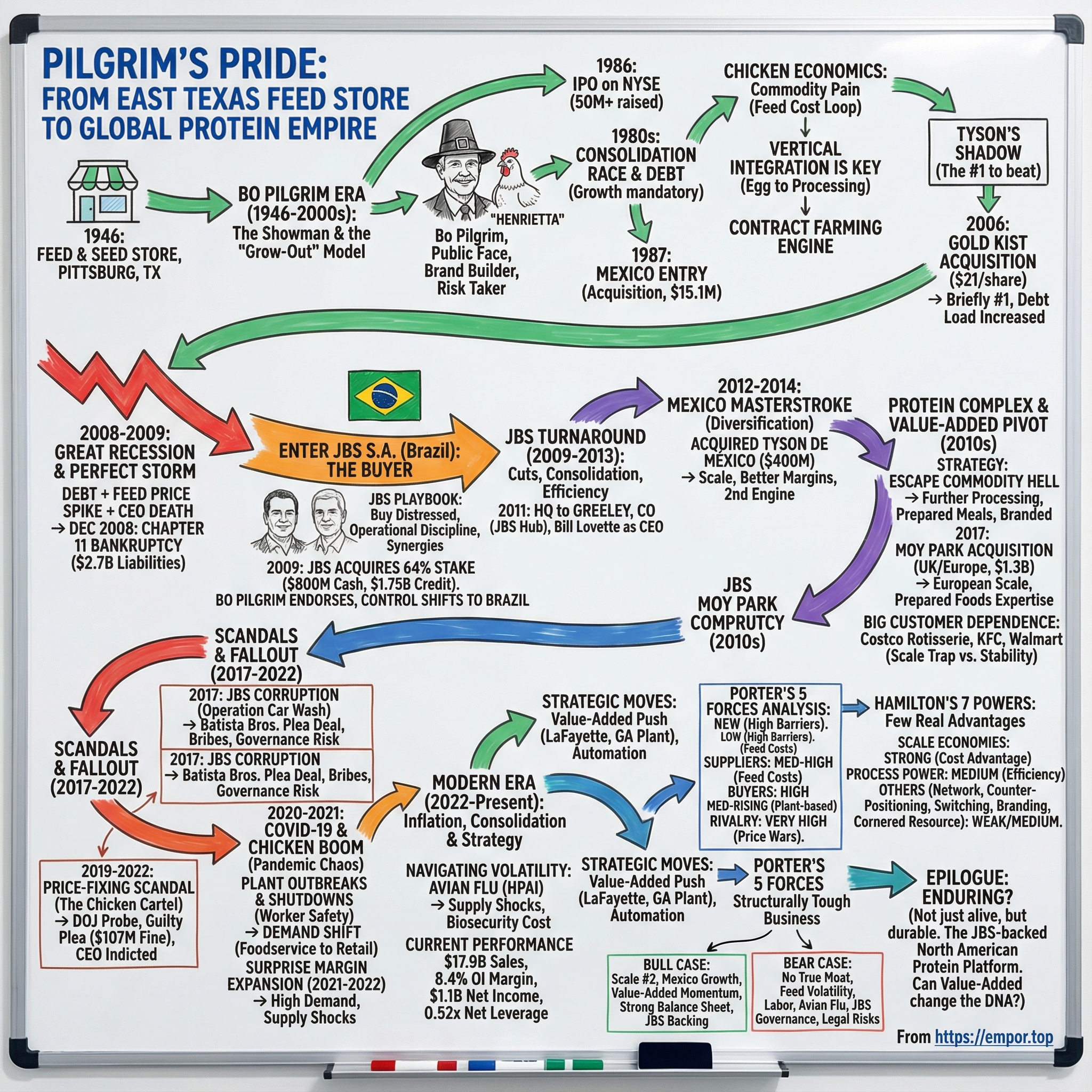

Pilgrim's Pride: From Texas Poultry Farm to Global Protein Empire

I. Introduction: America's Second Chicken and the Brazilian Question

Picture this: a man in a Pilgrim hat—buckle, feather, the whole costume—walks onto the floor of the Texas Senate and starts handing out $10,000 checks.

That man was Lonnie “Bo” Pilgrim, the co-founder of Pilgrim’s Pride. In 1989, just two days before a vote on major changes to Texas’s workers’ compensation system, Pilgrim entered the chamber and gave $10,000 checks to nine state senators. He called them campaign contributions, not bribes, even though he opposed the bill. The stunt exploded into an infamous political scandal—and two years later, Texas created the Texas Ethics Commission in response.

For Bo Pilgrim, though, it fit the brand: loud, brazen, and completely unapologetic.

Fast forward to today, and the company he helped build from a Depression-era East Texas feed store is a global protein giant. In 2024, Pilgrim’s Pride reported $17.9 billion in net sales, an 8.4% consolidated GAAP operating income margin, $1.1 billion in GAAP net income, and GAAP EPS of $4.57. It employed about 62,000 people and ran protein processing and prepared-food facilities across 14 U.S. states, plus Puerto Rico, Mexico, the U.K., the Republic of Ireland, and continental Europe.

But the real hook—the reason this story belongs in the business canon—isn’t just the scale. It’s the ownership.

How does a company born in East Texas end up controlled by a Brazilian meat conglomerate? And in an industry famous for cyclical chaos and knife-edge margins, how does Pilgrim’s survive bankruptcy, scandal, and a once-in-a-century pandemic… and still come out the other side as a steady profit generator?

That’s what we’re unpacking: the brutal economics of turning grain into meat, the consolidation logic that rules modern agriculture, and what happens when emerging-market capital collides with American commodity infrastructure. It’s a story of vertical integration, geographic expansion, and the question that never goes away in commodities—can scale ever be a real moat?

II. Origins: The Bo Pilgrim Era (1946–2000s)

A Feed Store in East Texas

It starts on October 2, 1946, in Pittsburg, Texas—a small East Texas town of roughly 4,000 people. Brothers Aubrey and Lonnie “Bo” Pilgrim, along with a partner, Pat Johns, opened a feed and seed store with $3,500.

Postwar America was gearing up for a baby boom, and with it, a boom in demand for protein. But in 1946, chicken wasn’t the everyday staple it is now. Birds were often raised in backyards, sold live, and saved for special occasions. The factory-farm, year-round chicken aisle at the grocery store was still a long way off.

The early Pilgrim’s business was straightforward: sell feed and baby chicks to local farmers. But the way they sold them hinted at something bigger. They’d sometimes give away chicks with bags of feed—an aggressive little move that helped them grow fast.

Over time, that logic evolved into what became the “grow-out” contract farming model: provide farmers with the birds and the feed, have farmers raise them, then buy back the grown chickens to process and sell. Simple on the surface. Transformative in practice. It shifted huge pieces of the day-to-day growing risk onto the farmer, while the company built the scale and the system around processing and distribution.

The Rise of Bo

Everything changed in 1966. Aubrey Pilgrim died of a heart attack at just 42, and Bo became CEO. He eventually built a fortune that reached $1 billion—and the death in the family also pushed him into a personal health kick, because heart trouble ran in the family.

That contradiction tells you a lot about Bo Pilgrim: a man focused on protecting his own heart while building a business that fed America’s appetite for comfort food. He was deeply religious, intensely competitive, folksy in presentation, and sharp in how he played the game.

And he didn’t just run Pilgrim’s Pride. He performed it.

In January 1983, he began promoting Pilgrim’s Pride through a television commercial that became a hit, with Bo on-screen in the now-famous Pilgrim hat, selling the “superiority” of the product line. He even had a pet chicken—“Henrietta”—that he carried in advertisements. In an industry where most executives stayed invisible, Bo made himself the brand. Some people thought it was corny. Bo thought it worked. And it did.

Going Public and the Acquisition Spree

On November 15, 1986, Pilgrim’s Pride went public on the New York Stock Exchange, raising more than $50 million. Bo still kept control, holding 80% of the shares.

The timing couldn’t have been better. The 1980s were the era when chicken became an industrial arms race—bigger plants, bigger distribution, tighter systems, relentless efficiency. Consolidation was the story of the category. From 1960 to 1984, the number of broiler producers fell by about 80%, and by the end of the decade there were only 45 producers left.

Pilgrim’s wasn’t going to be one of the companies that got swallowed. Through much of the 1980s, sales grew around 20% a year. A lot of that came from Bo’s willingness to play with fire financially, pushing debt-to-equity ratios beyond four-to-one just to stay ahead. He wasn’t trying to build a nice steady business. He was trying to build something that couldn’t be ignored.

Pilgrim’s first big international move followed quickly. In late 1987, it entered Mexico by acquiring four fully integrated poultry operations serving the massive Mexico City market for $15.1 million. By 1989, net sales jumped 30%, and net income climbed above $20 million—good money, but still only a little over a three percent profit-to-sales ratio.

Which is the key lesson of the Bo era: in commodity businesses, growth is often mandatory, not optional. Standing still can be fatal. Pilgrim’s expansion was risky, but it was also the playbook for survival. The lingering question—the one that will haunt this whole story—is whether the leverage and the cycles would eventually come due.

III. The Consolidation Wave & Industry Structure (1990s–2000s)

Understanding Chicken Economics

To understand Pilgrim’s Pride—and really, the chicken business as a whole—you have to start with one uncomfortable truth: this is a commodity industry with commodity pain.

The two biggest costs are corn and soybeans, the core ingredients in chicken feed. Pilgrim’s can’t control either one. When feed prices spike, processors get crushed. When feed prices fall, the whole industry breathes a sigh of relief, ramps up production, and then floods the market—sending chicken prices down and margins right back into the ditch. It’s a boom-bust loop that turns “good years” into short interruptions between bad ones.

So the industry adapted the way commodity industries always do: by trying to take as much of the value chain into the company as possible. Vertical integration became table stakes. Pilgrim’s Pride operated as a fully integrated system: egg production, hatcheries, contract growing, feed mills, rendering, and processing—then selling into retail, fast food, food service, and warehouse channels.

The contract farming model is the engine under the hood. Pilgrim’s provides chicks, feed, and technical guidance. Farmers build and own the chicken houses, raise the birds, and get paid a fee. Then Pilgrim’s buys the mature birds back and runs them through its plants.

A crucial nuance: during the grow-out phase, the company doesn’t actually own the birds. But it controls almost everything that determines performance—genetics, feed formulation, and standards—while the grower carries the capital burden of the facilities and a lot of the day-to-day risk. It’s an efficient model, and it’s also controversial, because growers tend to have limited bargaining power. In practice, they’re price-takers.

Tyson's Shadow

All of this played out under one looming fact: Tyson was the gravitational center of U.S. chicken.

Pilgrim’s could sell itself as a strong alternative—especially as it landed major customers like Kentucky Fried Chicken, Kraft General Foods, and Wendy’s. But Tyson stayed the leader. It held its position as the largest poultry producer in the United States, with about 21% market share, and it processed more than 45 million chickens a week across its network of plants.

For Pilgrim’s, competing with Tyson was like being the number-two cola. You can build a real business. You can even win big accounts. But you don’t get to relax. The strategic logic was relentless: get bigger—or eventually get acquired.

The Gold Kist Gamble

That pressure is what set up the defining move of the 2000s.

On December 4, 2006, Pilgrim’s Pride announced it had successfully acquired Gold Kist—formerly the third-largest chicken company—for $21.00 a share. Gold Kist initially resisted, but in the end, both boards voted unanimously to combine.

This was Bo Pilgrim’s final major strategic swing, and it was enormous. With Gold Kist folded in, Pilgrim’s Pride briefly became the largest chicken company in America, even surpassing Tyson. By 2007, Bo Pilgrim and his family still owned roughly 62% of the company.

On paper, it looked like the ultimate consolidation win.

In reality, the timing couldn’t have been worse.

IV. The Great Recession & Bankruptcy (2008–2009)

The Perfect Storm

2008 is remembered as the year the global economy snapped. For Pilgrim’s Pride, it was worse: the company hit the wall with a balance sheet already loaded for impact.

Just two years earlier, the Gold Kist deal had helped Pilgrim’s briefly leapfrog Tyson. It also loaded the company with debt—debt that suddenly mattered a whole lot more when the fundamentals turned.

Then the cost of feed surged. In 2007 and 2008, the ethanol boom and government mandates pushed more corn into fuel markets, tightening supply and sending prices higher. For a chicken processor, that’s existential. Feed is the biggest input, and when it spikes, the entire business model starts bleeding.

The pressure was already building when Pilgrim’s lost a key stabilizer. On December 17, 2007, CEO O.B. Goolsby Jr. died after suffering a stroke on a hunting trip in South Texas with customers. The company went into the most volatile period in decades without its operational leader.

By late 2008, the situation had turned dire. On December 1, 2008—just weeks after Lehman Brothers collapsed and credit markets froze—Pilgrim’s Pride filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The company listed $2.7 billion in liabilities, weighed down by acquisition debt and input costs that were rising faster than revenue. In a moment when capital was disappearing everywhere, a big, messy restructuring in a commodity business looked like the kind of thing that could easily end in liquidation.

Enter JBS

And then, from outside the American business conversation, came the buyer.

JBS S.A.—the Brazilian meat giant in the middle of a global acquisition sprint—stepped into the wreckage with a plan and, more importantly, cash.

The deal set Pilgrim’s at an enterprise value of about $2.8 billion. Under the plan of reorganization, Pilgrim’s agreed to sell 64% of the new common stock of the reorganized company to JBS, through JBS USA Holdings, for $800 million in cash.

When Pilgrim’s emerged from Chapter 11 on December 28, 2009, the transaction closed. Alongside the equity purchase, JBS provided a $1.75 billion exit credit facility to keep the business running. The restructuring wiped out the old shares and cleared away much of the pre-bankruptcy debt that had piled up during the feed-cost surge and poultry-price downturn.

For Bo Pilgrim, now in his 80s, it was a save—but not a victory lap. The company lived, creditors were paid in full, and existing shareholders held onto 36% of the reorganized Pilgrim’s. Bo publicly backed the outcome, saying, “We believe our reorganisation plan will pave the way for Pilgrim’s Pride to emerge from bankruptcy before the end of the year and mark a new beginning for this proud company, one that I fully support and endorse.”

But the defining change was irreversible: control had moved to Brazil. An East Texas chicken empire had survived the crash—only to wake up as the American arm of a South American meatpacking giant.

V. The JBS Turnaround & Integration (2009–2013)

The Batista Brothers: Visionaries or Cowboys?

To understand what happened to Pilgrim’s Pride after 2009, you first have to understand who caught it on the way down: JBS, and the Batista brothers behind it.

Joesley Batista is the son of José Batista Sobrinho, who founded JBS S.A. What started as his father’s Brazilian butcher shop became the backbone of one of the world’s largest meatpacking companies—and one of Brazil’s most important agribusiness giants.

Joesley and Wesley Batista took that foundation and scaled it at breakneck speed. In their late 40s and early 50s, they pushed JBS through a decade-long, debt-and-stock-fueled acquisition spree totaling around $20 billion, building a global protein empire that, in both ambition and velocity, rivaled the biggest roll-ups anywhere in the world.

Wesley M. Batista, president and chief executive officer of JBS USA Holdings, framed the approach in classic turnaround terms: “Two years ago, JBS acquired Swift & Company, a US beef and pork company, with a goal of managing its strong assets and turning it into a well-managed, efficient and profitable company. We believe the company’s performance demonstrates our continued success in meeting this goal.”

That was the JBS playbook in a sentence: buy big assets—often distressed or undervalued—impose operational discipline, pull out synergies, and plug them into a global supply chain. Pilgrim’s Pride was the move that brought that model into American poultry.

Operational Transformation

JBS didn’t waste time making Pilgrim’s look and run like the rest of its portfolio.

In January 2010, Pilgrim’s eliminated 230 corporate and administrative roles to cut overhead. In April 2010, it shut down its Mount Pleasant, Texas corporate headquarters, laying off 158 more employees as administrative functions were consolidated into JBS USA.

Pilgrim’s had emerged from bankruptcy in December 2009. Two years later, in 2011, the company relocated its U.S. headquarters to Greeley, Colorado—where JBS USA was already headquartered.

The move from Pittsburg, Texas, to Greeley wasn’t just logistical. It was a public signal that the center of gravity had shifted. This wasn’t Bo Pilgrim’s company anymore. The old Texas headquarters—complete with a massive bust of Bo’s head—turned into a kind of monument to the era that had just ended.

In 2011, Bill Lovette was appointed CEO, a steady operator for a business that didn’t need more drama—it needed execution. Under Lovette, Pilgrim’s began its transformation from bankruptcy survivor into a profitable multinational.

VI. The Mexico Masterstroke (2012–2014)

Building a North American Platform

Pilgrim’s Pride didn’t discover Mexico under JBS. It had been there for decades—and it had worked. By 1994, the company’s Mexican operations had grown to about 20% of total revenue, a signal that this wasn’t a side bet. It was a second engine.

Bo Pilgrim’s original move in 1987 turned out to be quietly brilliant. Mexico’s growing middle class was buying more protein, and chicken—cheap, familiar, and easy to scale—was the obvious winner.

Under JBS, Pilgrim’s didn’t treat that history as a nice footnote. It treated it like a blueprint.

In 2013, Pilgrim’s Pride announced a definitive agreement to buy Tyson Foods’ poultry businesses in Mexico for $400 million in cash, pending regulatory approval. The pitch was straightforward: fold in Tyson de México—a vertically integrated operation based in Gómez Palacio in north-central Mexico—and instantly deepen Pilgrim’s footprint.

Pilgrim’s said the deal would add roughly $650 million in incremental annual revenue. Tyson de México brought real infrastructure: three plants, seven distribution centers, and more than 5,400 employees, built over more than 20 years in the market.

The bigger point wasn’t just size. It was what Mexico represented strategically. In a commodity business where the U.S. market can swing from feast to famine in a single feed cycle, Mexico gave Pilgrim’s something rare: diversification that actually mattered. Different demand patterns. Different competitive dynamics. And, critically, different margin profiles.

Over time, Mexico became the crown jewel—more stable growth, stronger profitability than U.S. commodity chicken, and a platform Pilgrim’s could keep building on. The business there ultimately included 24 dedicated distribution centers and partnerships with around 3,000 family farms.

VII. The Protein Complex & Value-Added Pivot (2010s)

Escaping Commodity Hell

The fundamental challenge facing any chicken company is simple: commodity chicken is a brutal business. When your product is basically interchangeable, buyers hold the leverage, competitors race to the bottom on price, and profits disappear just as fast as they show up.

Pilgrim’s had understood this early. In January 1986, it opened a state-of-the-art further processed facility in Mt. Pleasant, Texas—an early signal that the company wanted a buffer against the endless swings of raw chicken pricing.

Under JBS, that idea turned into a strategy. The goal was to move beyond shipping raw birds and into further processing: marinated cuts, prepared meals, and branded or customer-specific products. Same underlying input. Very different economics. If you can sell a product that’s defined by recipe, consistency, and convenience—not just price per pound—you’ve got a shot at steadier margins and stickier customer relationships.

The Moy Park Acquisition

The clearest statement of that strategy came through Europe.

Pilgrim’s acquired Moy Park, a leading poultry and prepared foods supplier with operations in the United Kingdom and continental Europe, from JBS S.A., in a transaction valuing the equity interest at $1.3 billion (approximately £1.0 billion). The deal was unanimously approved by a Special Committee of the Pilgrim’s Board of Directors.

Moy Park had real history and real credibility. Founded in Northern Ireland in 1943, it built a reputation around fresh, locally farmed poultry—and a track record of top quartile profit growth. By the time Pilgrim’s bought it, Moy Park was a top 10 UK food company, one of Europe’s leading poultry producers, and a fully integrated platform working with more than 800 farmers across the UK.

But the deal came with baggage. JBS owned both Pilgrim’s Pride and Moy Park, which raised the obvious conflict-of-interest question: was Pilgrim’s paying a fair price, or was JBS simply moving assets around inside the family? Minority shareholders weren’t quiet about it, especially because JBS S.A. was the majority stakeholder of both Pilgrim’s and Moy Park when the deal closed.

Strategically, though, it fit. Moy Park processed more than 5.7 million birds per week and operated 13 processing plants across the UK, Ireland, France, and the Netherlands, supplying major food retailers. It also produced around 200,000 tons of prepared foods per year.

In other words: Europe, scale, and a much deeper bench in the higher-margin prepared foods business—exactly where Pilgrim’s wanted to go if it was serious about escaping commodity gravity.

Big Customers, Big Dependence

Even with a value-added push, Pilgrim’s still lived and died by big customers.

It had long supplied Kentucky Fried Chicken and was even named KFC’s “supplier of the year” in 1997. Other major customers included Walmart, Publix, and Wendy’s. And by 2012, Pilgrim’s had landed a marquee account: it became Costco’s exclusive rotisserie chicken supplier, providing about 50 million marinated, three-pound birds designed to go straight onto the rotisserie.

That kind of relationship is both a trophy and a trap. The volume is enormous and dependable. But it comes with razor-thin margins and enormous buyer power—especially with a customer like Costco, famous for using rotisserie chickens as a loss leader to drive store traffic. For Pilgrim’s, the contract delivered scale and stability, but it also reinforced the central tension of the business: the bigger the customer, the harder it is to keep the economics in your favor.

VIII. The JBS Corruption Scandal & Fallout (2017)

Operation Car Wash Reaches the Meat Industry

By 2017, Brazil’s sweeping anti-corruption probe—Operation Car Wash—had already torn through construction firms, politicians, and state-linked businesses. Then it reached meat.

Joesley Batista, one of the two brothers who controlled JBS, secretly recorded President Michel Temer. The recording appeared to capture Temer authorizing bribe payments to a notoriously corrupt politician who was already in prison for graft.

Agribusiness had always been a power center in Brazilian politics. Operation Car Wash suggested that influence wasn’t just lobbying muscle—it was systemic graft. In May 2017, Joesley and Wesley Batista, along with five other executives, signed a plea deal with prosecutors and admitted they had bribed politicians.

Investigators described the scale as breathtaking: over roughly 14 years, the Batistas spent $180 million to bribe more than 1,800 Brazilian regulators, government officials, and politicians, including three of Brazil’s presidents. JBS told prosecutors it had paid $123 million in bribes to Brazilian politicians in recent years.

The fallout was immediate and destabilizing. The scandal nearly toppled a president. The brothers were pushed out of day-to-day control, and the family holding company, J&F, agreed to pay 10.3 billion reais (about $2 billion) to Brazilian authorities over 25 years. J&F later reached a separate deal with the U.S. Department of Justice for $256 million. The Batista brothers spent several months in jail in 2017 and 2018 amid insider trading charges.

Impact on Pilgrim's Pride

For Pilgrim’s Pride, this wasn’t a distant headline. It was a governance alarm bell. Pilgrim’s was controlled by owners who had just admitted to systematic bribery on a global scale, and the reputational blast radius extended straight into the U.S. public markets.

The timing also collided with the Moy Park acquisition, adding another layer of tension. News of the purchase surfaced after billionaire Joesley Batista and former JBS executive Ricardo Saud turned themselves in to São Paulo police over alleged violations of the plea deal. It was a reminder that even when Pilgrim’s strategy made sense on paper, the JBS connection could turn any transaction into a credibility test.

And then came the twist: the Batistas didn’t stay away.

After about six years out of the spotlight, they effectively voted themselves back onto JBS S.A.’s board on April 26. In the shareholder vote, the motion to reinstate them lost among general shareholders—nearly 248 million votes against to 142 million in favor. But J&F Investimentos S.A. then cast its billion shares, and the brothers were reinstated anyway.

For Pilgrim’s minority shareholders, the message was hard to miss: whatever “independence” Pilgrim’s had, it lived downstream of a controlling owner that could—and would—assert its will.

IX. Price-Fixing Scandal & Legal Troubles (2019–2022)

The Chicken Cartel

If the JBS corruption scandal felt like a Brazilian problem spilling into U.S. markets, what hit Pilgrim’s next was unmistakably American: a DOJ antitrust case aimed straight at the heart of the chicken business.

Federal prosecutors alleged that a conspiracy to fix prices and rig bids for broiler chicken products began at least as early as 2012 and continued into early 2019. In other words, right as Pilgrim’s was trying to prove it could be a disciplined, post-bankruptcy operator under JBS, it was also being accused of doing the thing commodity industries are most tempted to do: coordinate.

Pilgrim’s ultimately pleaded guilty. The company was sentenced to pay about $107 million in criminal fines for participating in the scheme. In its plea agreement in U.S. District Court in Denver, Pilgrim’s admitted that from at least 2012 into 2017 it took part in a conspiracy to suppress and eliminate competition for U.S. broiler chicken sales—conduct that the DOJ said affected at least $361 million of Pilgrim’s sales.

It was the first chicken company to plead guilty in the DOJ’s broader investigation. That “first” mattered: it signaled the government wasn’t poking around the edges. It was building a real case.

And then it climbed the org chart.

In June, the DOJ indicted four current and former senior executives from two major chicken producers. Pilgrim’s CEO Jayson Penn was among them. The indictment alleged that executives at Pilgrim’s and Claxton coordinated to fix prices and rig bids for broiler chicken across the U.S. from 2012 until at least early 2017.

Inside Pilgrim’s, the leadership question became urgent: how do you keep the machine running while the CEO is fighting federal charges?

The company chose speed and continuity over a long, external search. Fabio Sandri—who had joined Pilgrim’s as CFO in June 2011—was appointed interim president and CEO on June 15. On September 23, 2020, Pilgrim’s made it permanent, naming Sandri CEO and replacing Penn, who had gone on leave after the indictment.

In February 2021, Pilgrim’s agreed to pay the roughly $107 million fine tied to the bid-rigging and price-fixing charges.

Industry-Wide Problem

Pilgrim’s wasn’t the only company under the microscope. The DOJ’s investigation sat on top of years of civil allegations that major chicken producers had colluded to inflate prices. The probe was publicly disclosed after the DOJ intervened in a lawsuit filed in 2016, which accused companies including Pilgrim’s, Perdue Farms, Tyson Foods, and Sanderson Farms of coordinating to raise prices.

After the Pilgrim’s and Claxton indictments, Tyson said it was cooperating with the DOJ under the Antitrust Division’s Corporate Leniency Program.

The deeper lesson here isn’t that chicken companies are uniquely villainous. It’s that the industry’s structure creates a constant pressure cooker. When margins are thin, the product is largely interchangeable, and buyers squeeze relentlessly, the temptation to “stabilize” pricing can start to feel like survival. That doesn’t justify it—it was illegal, and prosecutors said it cost consumers hundreds of millions of dollars—but it does explain why, in commodity hell, the line between competition and coordination can become dangerously easy to rationalize.

X. COVID-19 & The Chicken Boom (2020–2021)

Pandemic Chaos

COVID didn’t hit Pilgrim’s Pride as a neat, manageable “headwind.” It hit like a wrench in the gears—right where the company was most exposed: crowded, labor-intensive processing plants that had to run every day.

In late April 2020, an outbreak began at Pilgrim’s Pride’s plant in Lufkin, Texas. On May 8, a worker from the Lufkin plant was found dead at her home after being diagnosed with COVID-19.

Other facilities saw outbreaks too. In Moorefield, West Virginia, the West Virginia National Guard tested 520 of the plant’s 940 workers; 18 tested positive. By May 11, 2020, there were 194 diagnosed COVID-19 cases among workers at Pilgrim’s plant in Cold Spring, Minnesota, a facility that employed about 1,100 people.

Across 2020, Pilgrim’s temporarily closed several processing plants due to outbreaks among workers. The shutdowns exposed just how fragile the meat supply chain could be—and they intensified scrutiny around worker safety, health protocols, and labor conditions.

And then, as if that wasn’t enough, the demand side of the business snapped in half and reassembled itself somewhere else.

By March, the pandemic triggered what Pilgrim’s described as the fastest-ever shift in demand from foodservice to retail. “Despite the sharp decline in foodservice requirements, we were able to quickly respond to the shift in channel demand by increasing our volume mix to key customer retailers,” CEO Jayson Penn said.

Financial Impact

Financially, 2020 was ugly—but it wasn’t fatal. Pilgrim’s closed fiscal year 2020 with GAAP net income of $94.8 million. It reported adjusted operating income margins of 3.6% in the U.S. (excluding legal settlements), 5.5% in Mexico, and 3.1% in Europe. Adjusted EBITDA was $788.1 million, a 6.5% margin.

The pandemic year was challenging but survivable. What came next was the surprise: 2021 and 2022 delivered extraordinary margin expansion as demand surged and competitors struggled to keep up.

XI. Modern Era: Inflation, Consolidation & Strategy (2022–Present)

Navigating Volatility

Just as the post-COVID boom began to cool, another old enemy returned to the center of the industry’s risk map: avian flu.

On February 8, 2022, APHIS confirmed highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in a commercial U.S. flock. From there, the outbreaks spread across the map. Since 2022, reported cases have hit 1,431 poultry flocks across all 50 states and Puerto Rico—652 commercial flocks and 779 flocks kept by individual owners. USDA estimates those impacted flocks contained about 138.7 million birds.

The damage has been most severe in egg layers and turkeys. Broiler operations—where Pilgrim’s makes its living—have generally been less affected. But “less affected” doesn’t mean untouched. The virus still creates supply shocks, trade disruption risk, and a constant operational tax: tighter biosecurity, more monitoring, and more uncertainty. In 2023, U.S. economic losses from avian influenza in poultry were estimated at around $3 billion.

Current Performance

By 2024, Pilgrim’s looked like a company that had learned how to operate through chaos.

It reported $17.9 billion in net sales for 2024, with an 8.4% consolidated GAAP operating income margin. GAAP net income was $1.1 billion, and GAAP EPS was $4.57. On an adjusted basis, net income was $1.3 billion, or $5.42 in adjusted EPS. Revenue rose about 3% from 2023, while net income jumped sharply year over year.

Just as important as the income statement was what sat behind it: a 0.52x net leverage ratio, well below typical industry levels, giving the company real flexibility when the cycle turns. The business also generated strong cash flow, helped by disciplined working capital management even as the operation stayed large and complex.

Operationally, Pilgrim’s leaned into its portfolio approach. In U.S. Fresh, it benefited from strong chicken demand and continued execution on operational excellence, with a mix across bird sizes and more differentiated offerings that helped it capture the upside from above-average commodity values. In U.S. Prepared Foods, it kept pushing into the less-commoditized side of the business: branded offerings grew nearly 25% year over year, led by Just Bare® and Pilgrim’s®.

Recent Strategic Moves

Pilgrim’s didn’t treat those results as a victory lap. It treated them like fuel.

In 2025, the company announced a $400 million investment to build a new prepared foods facility in LaFayette, Georgia. Once fully operational in 2027, Pilgrim’s expects the plant to lift U.S. Prepared Foods sales by more than 40% from current levels.

It also laid out a bigger investment plan: $650–$700 million in total capital expenditures for 2025, aimed at expanding capacity in both the U.S. and Mexico. The projects included converting a commodity plant into a premium trade-pack facility and expanding air-chill processing capacity in the U.S.—more moves designed to push the mix toward higher-value products.

And then came two reminders that, for Pilgrim’s, strategy has never been purely operational—it’s also about power.

In January 2025, Pilgrim’s Pride contributed $5 million to the second inauguration of Donald Trump, the largest contribution to the inauguration fund. And in May 2025, the SEC approved the listing of JBS S.A.—Pilgrim’s controlling owner—on the New York Stock Exchange.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

If you wanted to start a major chicken processor from scratch, you wouldn’t just be competing with Pilgrim’s Pride. You’d be competing with the industrial system Pilgrim’s and its peers have spent decades assembling.

The industry has consolidated hard. The top producers now control a large majority of the U.S. chicken market, and that concentration is self-reinforcing: scale lowers unit costs, scale attracts the biggest customers, and those customers demand capabilities that only scaled players can provide.

To even get in the game, a would-be entrant needs massive capital for plants and logistics, a web of contract growers, regulatory approvals, and customer relationships that are earned over years. The simplest proof that these barriers are real: no meaningful new entrants have shown up in decades.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MEDIUM-HIGH

In chicken, your “suppliers” aren’t just vendors. They’re the global forces that set your biggest costs.

Feed is the monster line item, and corn and soybean prices are dictated by commodity markets that Pilgrim’s can’t influence. When those inputs jump, margins get squeezed fast, no matter how good the operator is.

Then there’s genetics. A small number of suppliers control the breeding stock that drives bird performance, and there aren’t many true alternatives. That concentration limits how much leverage processors have in negotiations, and it makes switching difficult.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

Pilgrim’s sells to some of the most powerful buyers on the planet: Walmart, Costco, McDonald’s, KFC, and other major retail and foodservice giants.

Pilgrim’s works hard to be more than a spot-market supplier—building long-term relationships, customizing products, and offering value-added services. But in commodity chicken, buyers still hold the cards. They can push for price concessions, set demanding specifications, and credibly threaten to move volume elsewhere because, at the base level, chicken is chicken.

The one place Pilgrim’s gets some relief is in prepared foods and branded products, where the product is less interchangeable and switching costs are higher.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM-RISING

The substitute set is getting bigger and louder, especially from plant-based “chicken” products. As taste and texture improve, and as more consumers weigh ethical, environmental, and health concerns, these alternatives become more credible—particularly for the kinds of breaded, seasoned, further-processed items where chicken is already one ingredient in a larger experience.

Still, chicken has structural advantages that are hard to beat. It’s generally the lowest-cost mainstream protein, it fits modern health preferences better than many red meats, and it’s culturally ubiquitous. U.S. per-capita chicken consumption is projected to set another record in 2025, as production edges up and chicken remains price-competitive versus beef and pork.

Competitive Rivalry: VERY HIGH

The chicken industry doesn’t do “friendly competition.” It does relentless, high-volume, low-margin warfare.

Tyson remains the largest U.S. broiler producer by ready-to-cook output, followed by Pilgrim’s and Wayne-Sanderson Farms. These are large, well-capitalized operators fighting in markets where differentiation is hard and price matters a lot.

When the industry gets even slightly ahead of demand, overcapacity shows up, pricing breaks, and margins collapse across the board. Consolidation has reduced the number of players, but it hasn’t changed the underlying dynamic: rivalry is intense because the product is hard to differentiate and the stakes are enormous.

Conclusion: By Porter’s framework, chicken is a structurally tough business. The defensible positions are scale—being #1 or #2 so you can win on cost—or building enough value-added and branded mix that you’re competing on more than price per pound.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: STRONG ✓

If Porter’s tells us chicken is structurally brutal, Hamilton’s framework tells us where the few real advantages can still exist. And in this industry, scale isn’t just helpful. It’s the whole game.

Bigger operators buy feed with more leverage, spread overhead across more pounds, and keep expensive plants running closer to full tilt. Pilgrim’s scale also shows up in its ability to push brands and higher-margin products through huge channels. The company’s branded portfolio grew 7%, and expansions like the Merida complex signal that Pilgrim’s believes it can keep compounding those regional advantages.

Network Effects: NONE ✗

There’s no network effect in chicken. A Costco rotisserie bird doesn’t get better because more people buy it, and Pilgrim’s doesn’t become more valuable to one customer because it serves another. This is manufacturing and logistics, not a platform.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK

Counter-positioning is what happens when a challenger finds a model incumbents can’t copy without breaking their own economics. That’s hard to pull off in chicken, because the incumbents already look a lot alike.

The major players have largely converged on the same formula: vertical integration, scale, and relentless efficiency. There isn’t much room for a radically different business model that the giants can’t respond to.

Switching Costs: WEAK TO MEDIUM

For raw, commodity chicken, switching costs are basically zero. Buyers can move volume between suppliers with little friction, because the product is largely interchangeable.

But Pilgrim’s does earn some stickiness where it matters most: in prepared foods and custom programs. Long-term relationships with customers like Walmart, Costco, KFC, and McDonald’s are built on meeting specific requirements—formulations, packaging, food-safety standards, and qualification processes. Those details create real, if modest, switching costs. The company has also leaned into differentiated offerings—organic, antibiotic-free, and animal welfare-certified products—to match shifting consumer preferences and make “chicken is chicken” less true.

Branding: WEAK TO MEDIUM

Pilgrim’s has brands, and some of them are working. Just Bare® was ranked number one on Circana’s Product Pacesetter’s List and has grown to more than 10% market share in fully cooked chicken, helped by expanding distribution and strong sales velocity.

Still, this remains a mostly B2B business. Most consumers don’t know—or care—who produced the chicken in their grocery cart or their fast-food meal. Perdue has built more consumer-facing differentiation than most, but in a category where the core product is still fundamentally similar, branding power has a ceiling.

Cornered Resource: WEAK

Pilgrim’s doesn’t have a resource that competitors can’t access. Land, labor, equipment, and poultry genetics are all available to any well-capitalized rival.

If there’s a “closest thing,” it’s the JBS connection: global procurement reach, operational know-how from the world’s biggest meat processor, and capital from an owner willing to play a long game. But that’s an ownership advantage—not a true moat that’s locked up exclusively by Pilgrim’s.

Process Power: MEDIUM ✓

In chicken, process is destiny. Small improvements in yields, throughput, feed conversion, biosecurity, and logistics compound into real money over time—and they’re hard to replicate quickly.

Pilgrim’s leadership has framed the strategy exactly that way. “While we experienced a positive market environment with lower input costs and strong chicken demand in 2024, we elevated our performance across all regions through a continued focus on controlling what we can control,” said Fabio Sandri, Pilgrim’s President and CEO. “As such, we improved efficiencies through operational excellence, expanded relationships with key customers, and drove growth in our value-added portfolio.”

JBS’s history of buying underperforming assets and tightening the operating system suggests Pilgrim’s process power is real. It’s not a magical advantage—but in an industry where margins can vanish overnight, being a few clicks better matters.

Overall Assessment: Pilgrim’s Pride operates in a market where durable moats are rare. The real powers here are scale economies and process power. Mexico and the value-added push improve the quality and resilience of the business—but they don’t repeal the laws of commodity gravity.

XIV. The JBS Question: Strength or Weakness?

The Bull Case for JBS Ownership

By the end of fiscal 2024, the ownership story at Pilgrim’s Pride was simple: JBS S.A. was in control. Through wholly owned subsidiaries, JBS held about 82.42% of Pilgrim’s outstanding common stock. That’s not “influence.” That’s the steering wheel.

That control dates back to the 2009 rescue out of bankruptcy, when JBS didn’t just provide capital—it effectively rewired Pilgrim’s into a much larger global protein machine. And if you’re making the bullish argument, that’s exactly the point.

JBS ownership brings some very real advantages:

Capital Access: JBS has repeatedly shown it will fund big swings—supporting initiatives like the Mexico expansion, the Moy Park acquisition, and today’s prepared foods buildout.

Global Procurement: As the world’s largest meat processor, JBS can bring purchasing leverage across geographies and protein categories that Pilgrim’s couldn’t match on its own.

Operational Expertise: JBS’s playbook is to buy complex assets and run them harder and smarter. Pilgrim’s turnaround after bankruptcy is the clearest proof of that.

Patient Capital: With a controlling owner, Pilgrim’s isn’t living quarter to quarter the way many public companies do. JBS can afford to think in years, not earnings calls.

The Bear Case

The flip side of “patient capital” is “permanent control.” With more than 80% of the stock, JBS can effectively decide what happens at Pilgrim’s—and minority shareholders mostly get to watch.

You saw that dynamic clearly in 2021, when JBS tried to buy the rest of Pilgrim’s and take it private. That effort didn’t succeed. The proposal was withdrawn in February 2022 after a special committee of Pilgrim’s board determined the offer undervalued the company. It was a sign that Pilgrim’s governance has at least some independent muscle. But it also underlined the risk: the controlling owner can try to change the game whenever it wants.

The key concerns look like this:

Corporate Governance: At 82%+ ownership, JBS controls virtually every major decision. Minority shareholders have limited leverage.

Political Risk: The Batista brothers’ corruption history—and their return to the JBS board—raises uncomfortable questions about the ethics and stability of Pilgrim’s ultimate controllers.

Trapped Minority: If you don’t like the strategy or the terms of a deal, you can’t outvote the majority owner. The 2021 buyout attempt also shows JBS is willing to pursue the remaining shares at prices others consider too low.

Regulatory Risk: JBS’s size and global ambitions draw scrutiny. Any regulatory restriction aimed at JBS can spill over onto Pilgrim’s, even if Pilgrim’s operations are running well.

XV. Playbook: Business & Investment Lessons

Commodity Hell: The Inescapable Challenge

The chicken industry is a clean demonstration of a brutal truth: when the product is hard to differentiate and the biggest input costs are set by global commodity markets, margins get squeezed again and again.

Any efficiency edge is temporary, because competitors copy it. Any period of fat profits invites more production, which pushes prices back down. The cycle doesn’t end—you just learn how to live inside it.

Pilgrim’s Pride survived by leaning into the only moves that reliably keep you alive in commodity hell: get big enough to win on cost, diversify so one market can’t sink the whole ship, and push downstream into products where you’re selling more than “chicken per pound.” None of that makes the business easy. But it makes it survivable.

Scale as Strategy

In 2018, the U.S. chicken leaderboard by weekly ready-to-cook volume looked like this: Tyson Foods at about 21% market share, Pilgrim’s Pride at about 17%, then a drop to Sanderson Farms around 10%, Perdue around 7%, and Koch Foods around 6%.

That gap is the point.

In commodity industries, being #1 or #2 isn’t bragging rights—it’s the difference between having a cost structure you can defend and having one that slowly bleeds out. The big players spread fixed costs across more volume, run plants harder, buy inputs with more leverage, and can offer the kind of consistency and coverage that the biggest customers demand.

Pilgrim’s has lived for decades in that #2 slot. It isn’t invincible. But it’s on the right side of the scale line—the side where you can keep fighting.

Geographic Diversification: The Mexico Lesson

Bo Pilgrim’s 1987 move into Mexico didn’t look like a masterstroke at the time. It looked like expansion.

In hindsight, it became one of the most important decisions in the company’s history. Mexico gave Pilgrim’s something U.S. commodity chicken rarely offers for long: a growth engine and a margin cushion. When the U.S. cycle turns ugly—as it always does—having a meaningful second geography can be the difference between riding out volatility and being crushed by it.

The lesson is that diversification only matters if it’s real diversification. New markets have to behave differently—different demand patterns, different competitive dynamics, different margin structures. Otherwise, you’ve just bought the same problem in a new place.

Governance Matters

Pilgrim’s learned the hard way that governance isn’t a “soft” issue in a low-margin business—it’s a financial one.

The price-fixing case led to more than $100 million in criminal fines, reputational damage, and the indictment of its CEO. And the JBS corruption scandal raised an even bigger question: when your controlling owner has a history of systemic bribery, every deal, every decision, and every headline comes with an added credibility tax.

In industries where competition is ruthless and profits can disappear overnight, the temptation to cut corners is always there. Strong compliance and real oversight aren’t just the moral choice. They’re part of the operating system that keeps a company from turning one bad decision into an existential event.

XVI. Bull vs. Bear Case

🐂 Bull Case

Scale Advantage: Pilgrim’s #2 position matters in a business where pennies per pound decide who lives and who dies. Being one of the two giants brings structural cost advantages that smaller competitors struggle to match. The top five producers now control nearly 65% of the U.S. chicken market, and in commodities, that kind of concentration tends to favor the leaders.

Mexico Exposure: Mexico has been Pilgrim’s best form of diversification: a market with better growth and better margins than U.S. commodity chicken, and a second profit engine when the U.S. cycle turns.

Value-Added Momentum: U.S. Prepared Foods keeps pulling the company away from pure commodity economics. Net sales in the segment grew more than 20% versus last year, and operations drove record production to keep up with demand across retail and foodservice.

Secular Protein Growth: The long-term demand backdrop remains favorable. The chicken market is expected to grow from about $160 billion in 2024 to about $268 billion by 2033, implying a mid-single-digit CAGR over that period.

JBS Backing: Whatever you think of the governance risk, JBS brings real muscle: capital, global scale, and operating expertise from the world’s largest meat processor.

Strong Balance Sheet: Sub-1x net leverage gives Pilgrim’s flexibility—room to keep investing, pursue opportunistic moves, or simply absorb the next down cycle without going back to the brink.

Automation Upside: This is still a labor-intensive business, which means productivity improvements compound. Continued automation investment can drive meaningful efficiency gains over time.

🐻 Bear Case

Structurally Unattractive Industry: Porter’s 5 Forces doesn’t just describe a tough category—it describes one that stays tough. Buyer power is high, rivalry is intense, and the product is hard to differentiate.

No True Moat: Even when a player finds margin, the industry has a way of competing it away. Commodity economics pull returns back toward the mean.

Feed Cost Volatility: The biggest cost inputs are priced by global markets, not management. That makes earnings inherently unpredictable.

Labor Challenges: Processing plants are hard places to staff and harder places to stabilize. Recruitment, retention, and wage pressure never really go away.

Avian Flu Risk: Since 2022, USDA estimates impacted flocks contained about 138.7 million birds. Broilers may be less affected than egg layers, but outbreaks still create sudden supply shocks and operational disruption.

JBS Governance: The Batista brothers’ return to the JBS board, combined with their corruption history, keeps a reputational and political cloud over Pilgrim’s—whether Pilgrim’s deserves it or not.

Legal Overhang: The price-fixing fallout didn’t end with the fine. Settlements and ongoing class action litigation continue to hang over the story.

Alternative Proteins: Plant-based and cultivated meat remain a long-term “what if.” Even partial substitution could matter in a category that depends on massive volume.

Climate/ESG Pressure: Animal agriculture is under growing scrutiny from consumers, investors, and regulators, and compliance expectations tend to rise over time—not fall.

What to Monitor

Key KPI #1 - Operating Margin: Watch consolidated and segment operating margins over time. The whole thesis of prepared foods is that it should make margins more durable and less cycle-driven.

Key KPI #2 - Mexico Performance: Mexico is the clearest proof point of diversification working. If growth and margins hold up there, the Pilgrim’s story looks meaningfully better.

Key KPI #3 - Feed Cost Spread: In the end, profitability is dominated by the spread between feed costs and chicken pricing—more than almost anything management can directly control.

XVII. Epilogue: Where Things Stand Today

As of December 27, 2025, Pilgrim’s Pride sits in a place very few Chapter 11 stories ever reach: not just alive, but durable.

This is the same company that went into bankruptcy in 2008 carrying $2.7 billion in liabilities. Today, it’s a consistent profit generator with nearly $18 billion in annual revenue, a balance sheet that looks more like a fortress than a warning sign, and market-leading positions in the U.S. and Mexico.

One person didn’t get to see the whole arc.

On July 21, 2017, co-founder Lonnie “Bo” Pilgrim died at 89. The company said at the time: “On behalf of the Pilgrim’s team, we offer our sincere condolences to the friends and family of Lonnie ‘Bo’ Pilgrim. Today’s poultry industry was built on the foundation of men like Mr. Pilgrim. He was a true icon, and his loss will resonate throughout our company and our industry.”

Bo didn’t live to see Pilgrim’s fully become what it is now: less a Texas poultry company and more a North American, JBS-backed protein platform. But the things he put in motion still show up everywhere—vertical integration, early Mexico exposure, and a culture that never shied away from big, risky swings.

The next decade’s question is the one that always hangs over a commodity business trying to evolve: can the value-added pivot actually change the DNA? Can prepared foods and branded products make Pilgrim’s less dependent on the brutal boom-bust cycles of raw chicken? Or will scale and operational efficiency remain the only advantages that truly stick?

And then there’s the owner.

The JBS relationship continues to be both a tailwind and a cloud. JBS has pursued a New York Stock Exchange listing, a move that could bring both more capital and more scrutiny to the entire corporate family. In May 2025, the SEC approved the listing of JBS S.A., Pilgrim’s holding company, on the NYSE.

For investors, Pilgrim’s is still the perfect case study in what makes this industry so captivating: the lure and limits of strategic transformation, the gravity of commodity economics, and the extra layer of complexity that comes with emerging-market control of an American staple. The company has endured bankruptcy, scandal, a pandemic, and avian flu. The only question left is whether “enduring” can become something closer to “thriving.”

From a feed store in Pittsburg, Texas, to a Brazilian-controlled global protein powerhouse, Pilgrim’s Pride is a story about American capitalism at full volume: reinvention, overreach, survival, and the relentless march toward consolidation and scale.

Bo Pilgrim would probably have something colorful to say about all of it. Henrietta the chicken, sadly, has no comment.

XVIII. Further Reading

Essential Resources:

- "The Meat Racket" by Christopher Leonard - A clear, unsettling look at how modern chicken became an industrial system, including the realities of contract farming

- JBS Annual Reports & Investor Presentations - The best window into the parent company’s strategy and how Pilgrim’s fits into the larger protein portfolio

- Pilgrim's Pride 10-K filings (2008, 2009, 2020) - The primary-source record for the bankruptcy, the post-JBS rebuild, and the legal trouble years

- DOJ Antitrust Case Documents (2020–2021) - The most direct documentation of the government’s allegations, the plea, and the enforcement narrative

- "Big Chicken" by Maryn McKenna - The broader history: how chicken went from backyard bird to commodity staple—and why the industry works the way it does

- USDA Poultry Production Reports - The data backbone for production, pricing context, and the cycle dynamics that drive the whole category

- Rabobank Protein Outlook Reports - High-quality industry analysis on demand, feed costs, and global protein markets

- Pilgrim's Pride Bankruptcy Court Documents (2008–2009) - The real-time paper trail of how the restructuring happened, and why JBS ended up in control

- National Chicken Council Industry Statistics - Helpful snapshots on market share, production volumes, and long-term category trends

- Congressional Research Service - HPAI Reports - A sober, policy-level view of avian flu, how outbreaks ripple through supply, and what the response looks like

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music