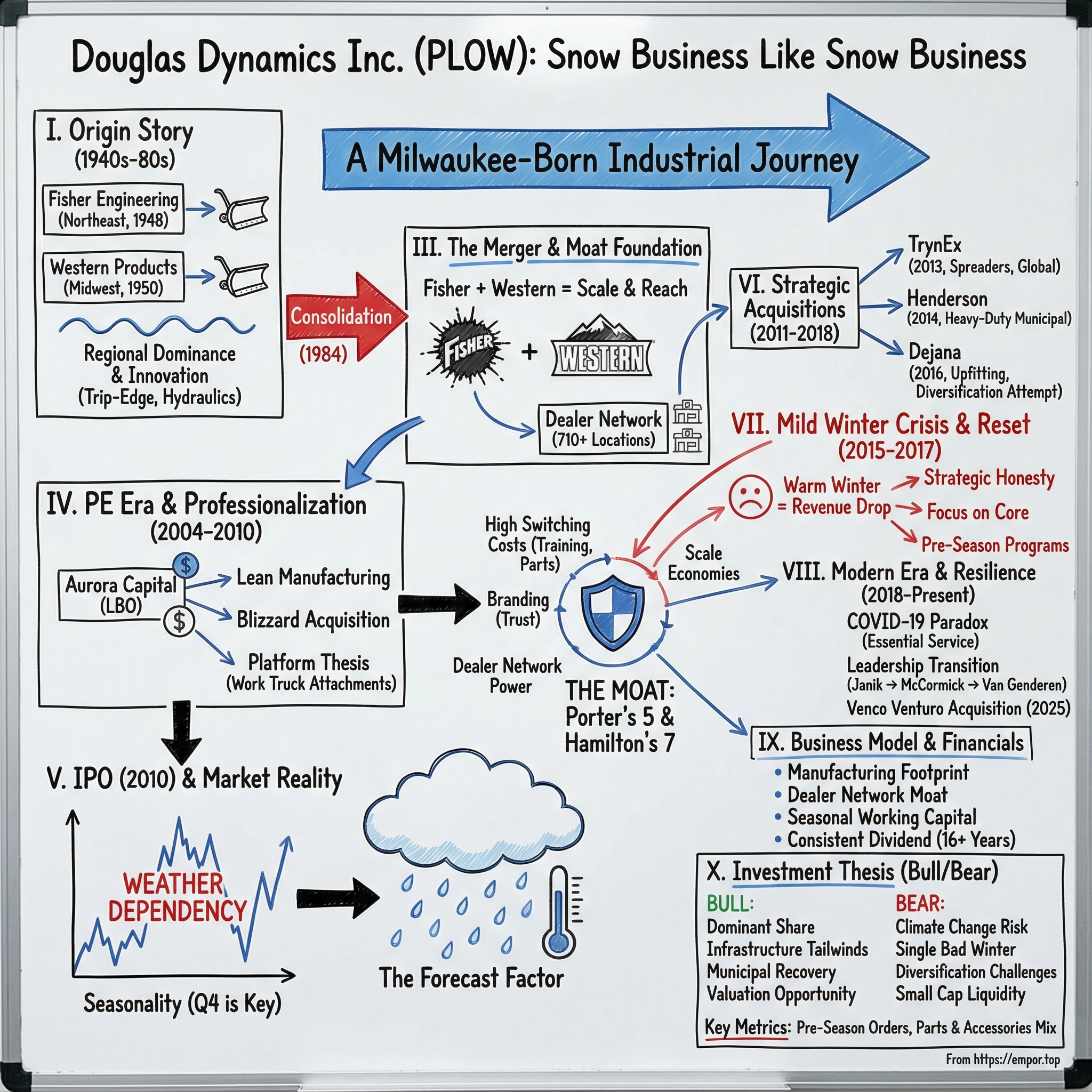

Douglas Dynamics Inc. (PLOW): Snow Business Like Snow Business

I. Introduction: The Invisible Monopoly That Clears America's Roads

It’s 4:30 a.m. on a January morning in Minneapolis. The thermometer is buried below zero. Overnight, a blizzard has dumped a foot and a half of snow, and the city is quiet in that eerie, muffled way it gets after a storm—until the call goes out.

A municipal works director watches the radar, checks the forecast, and makes the decision to roll. Within hours, trucks pour out of depots and spread across the metro: blades down, scraping to pavement; spreaders spinning, laying salt and sand in steady arcs. By the time commuters stumble toward the coffee pot, highways are open again, school buses are moving, and the economy flips back on.

Now take a step back and ask the uncomfortable question: what if your entire business depended on something you can’t control?

That’s Douglas Dynamics’ reality. It’s the company behind a huge share of the plows, spreaders, and replacement parts that make winter mobility possible across North America. In 2024, Douglas Dynamics generated $568.5 million in net sales and $56.2 million in net income—impressive numbers for a manufacturer most people have never heard of.

Inside the snowplow manufacturing world, the “big guys” list is short: Douglas Dynamics, Boss Snowplow, and Aebi Schmidt Holding AG. And Douglas is the one with the most market share. It has spent decades building a reputation for reliable gear, the kind of reputation that matters when failure isn’t an inconvenience—it’s a citywide crisis. This isn’t a flashy category, but it’s one where dominance sticks. Douglas controls a commanding share of the light-truck snowplow market, and it’s the kind of quiet market power that makes investors lean in.

Operationally, the company reports two segments: Work Truck Attachments and Work Truck Solutions. The heart of the story is Work Truck Attachments—snow and ice control equipment like plows, sand and salt spreaders for light and heavy-duty trucks, plus the parts and accessories that keep fleets running.

And that’s the tension that defines Douglas Dynamics. Over the years, it’s been pitched as everything from a broader work-truck platform to a diversified industrial consolidator. But the business keeps snapping back to its center of gravity: snow and ice. A weather-dependent company with deep brand loyalty and painful switching costs—a near-monopoly that lives and dies by the forecast.

Paradoxically, the very thing that scares people away—seasonality and weather risk—may also be what protects it. Most competitors don’t want to build a business where one mild winter can wreck your year. Douglas did. And then it learned how to win anyway.

II. The Milwaukee Tool Era & Founding DNA (1946-2000s)

Douglas Dynamics was born in the industrial heartland, in the kind of place where winter isn’t a season, it’s a fact of life. Milwaukee’s culture rewarded practical engineering: build it tough, make it fixable, and assume it’ll get used at 5 a.m. in miserable conditions. Douglas Dynamics traces its founding to 1948 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin—but the real origin story is more like two parallel winters that eventually collided.

On one track, Dean L. Fisher founded Fisher Engineering to build snowplows for Willys Jeep vehicles—the precursors to the modern Jeep brand. On the other, Douglas Seaman bought Western Welding and Manufacturing in 1950, renamed it Western Products, and started out doing small, one-off welding work for bigger manufacturers. To diversify, Seaman began making snowplows for light trucks.

In the early decades, these weren’t sleek national brands. They were regional manufacturers, selling heavy, durable equipment to customers they often knew personally. That was the industry: fragmented, local, and brutally practical. And it set up the dynamic that would define the category for decades—reputation mattered, and reputations were earned the hard way.

The Fisher Innovation Story

Fisher Engineering helped turn snowplowing from muscle work into machine work.

In 1957, Fisher developed its “trip-edge” system. The concept was simple but critical: when the cutting edge hits something that doesn’t move—like a curb or a hidden manhole cover—the edge can rotate backward instead of transferring that impact through the whole plow. In a business where downtime during a storm is essentially a financial emergency, that kind of protection wasn’t a feature. It was survival.

Then, in 1962, Fisher introduced its “Quick-Switch” hydraulic angling system. Instead of climbing out of the cab to manually change the blade angle, the operator could adjust left or right using a control lever inside the vehicle. That one change made plowing faster, safer, and dramatically more efficient—exactly what commercial operators needed as the market scaled.

By the mid-1970s, Fisher took another step forward, creating an electrically driven hydraulic system that could run off the electrical systems of modern trucks. The Northeast got its technology leader, and Fisher’s name became synonymous with equipment you could trust when the storm didn’t care.

Western Products' Midwestern Dominance

While Fisher was building its reputation in Maine and across the Northeast, Western Products was doing the same in the Upper Midwest. Demand surged as the 1960s brought more suburbs, more driveways, more parking lots, and more light trucks that could carry plows. Western rode that wave, with sales doubling between 1961 and 1968.

The post-war suburban boom didn’t just create neighborhoods; it created an entire ecosystem of snow removal work. Shopping centers, office parks, and subdivisions all had to be cleared after storms. Contractors became a permanent part of winter infrastructure. And contractors, unlike municipalities, don’t have patience for equipment that breaks—they just buy what works.

Western gained significant share through the 1970s. In 1977, Douglas Seaman formed Douglas Dynamics as the parent company for Western Products—an early move toward building something bigger than a single regional brand.

The Armco Steel Interlude

Then came the classic move of the era: the conglomerate swoop.

Armco Inc. bought Douglas Dynamics, which by that point was the nation’s largest manufacturer of snowplows for four-wheel-drive pickup trucks and utility vehicles. For Armco, this was what big industrial companies did—buy strong regional manufacturers and tuck them inside the portfolio. For Douglas Dynamics, corporate ownership meant more resources, but also meant being a division inside a steel-first company.

Later, AK Steel acquired Armco, and Douglas Dynamics remained a relatively small part of a much larger steel conglomerate. That context mattered. When your parent company’s center of gravity is steel, not snow equipment, the snow business can end up underappreciated—exactly the kind of situation that creates an opening when new owners come looking for overlooked assets.

By the time this era ended, the company’s DNA was set: engineer for durability, obsess over field performance, and win through trust built storm after storm. Snowplow brands don’t get to live on marketing. In this market, your product fails once in a blizzard and you don’t just lose a customer—you become a cautionary tale.

And that’s where the moat begins. Fleets train operators on specific systems. They stock parts for specific brands. They build service relationships with dealers over years. When the downside of experimentation is a city that can’t move and a contractor who can’t bill, buyers get conservative fast. Douglas Dynamics grew up in that world—and it learned how to become the default choice.

III. Consolidation Begins: The Fisher Acquisition (1984)

By the early 1980s, the snowplow world had a familiar shape: lots of small regional players, and two names that towered over the rest. Fisher in the Northeast. Western in the Upper Midwest. Different geographies, similar reputations—equipment that worked when the stakes were highest.

In 1984, those two lines finally converged. Dean Fisher sold Fisher Engineering to Douglas Dynamics in Milwaukee. With that one deal, Douglas Dynamics owned both Western Products and Fisher Engineering—the two biggest snowplow manufacturers in the country at the time.

This wasn’t just another acquisition. It was a structural shift. The industry didn’t fully consolidate overnight, but the center of gravity moved. And the position Douglas created in that moment would prove stubbornly durable for decades.

The strategic logic was straightforward. Scale matters in manufacturing: more volume lowers unit costs, improves purchasing leverage, and funds better engineering and service support. Distribution matters even more. Fisher and Western had built deep dealer relationships in their home regions, and those networks were hard-won—earned through reliability, parts availability, and showing up when something broke mid-storm.

Put the two together and Douglas Dynamics gained something far more valuable than a factory: reach. The company designed, manufactured, and sold snowplows, sand and salt spreaders, and accessories through a dealer network that eventually grew to roughly 2,200 dealers across the U.S. and Canada, plus about 40 more internationally. That kind of channel footprint isn’t something a new entrant can spin up quickly, no matter how good their product is.

Just as important was what Douglas didn’t do. It didn’t force Fisher and Western into one unified brand. That would’ve been a classic spreadsheet move—and a real-world mistake. Contractors in Maine didn’t want “Western.” Operators in Wisconsin didn’t want “Fisher.” They wanted the brand they trusted, with the controls they knew, supported by the dealer they’d relied on for years.

So Douglas kept both identities intact. Fisher stayed Fisher. Western stayed Western. It reduced customer friction, protected loyalty, and quietly gave Douglas a bit of regional diversification too: if one region had a light winter, the other might still be busy. Not a perfect hedge, but better than betting the company on one weather map.

Fisher’s roots also stayed visible. The company had been building plows and hopper and tailgate-mounted spreaders for more than 75 years in Rockland, Maine, and the facility continued operating—preserving the local credibility that helped make the brand what it was in the first place.

Of course, owning two iconic brands comes with internal complexity. You can’t let one brand cannibalize the other. You have to manage dealers who may carry both lines. You have to decide which plant builds what, and how engineering resources get allocated without triggering a turf war.

Douglas threaded that needle by drawing a sharp line between what customers saw and what the company could consolidate behind the scenes. Keep the brands separate in-market. Share what matters in the engine room: procurement leverage, manufacturing best practices, and innovations that can migrate across product lines. The customer still feels like they’re buying the same Fisher or Western they’ve always known, but the business gets to operate with the efficiency and muscle of a larger platform.

That became the template. Buy the best regional brand. Preserve its identity. Integrate where the synergies are real. And above all, don’t break the trust that the brand and the dealer network spent decades earning.

After 1984, the competitive terrain looked different. Anyone trying to enter the market wasn’t up against one entrenched incumbent. They were up against two—and they were both owned by the same company.

IV. The Private Equity Era: Aurora Capital Takes Over (2004-2010)

In April 2004, Douglas Dynamics finally got out from under the steel conglomerate umbrella. Aurora Capital Group, alongside Ares Private Equity Group, bought the business from AK Steel for $260 million.

On paper, it was the kind of deal private equity loves: a high-quality industrial asset sitting inside a parent company that didn’t really value it. AK Steel’s world was steelmaking. Snowplows were a niche side business. That usually means underinvestment, fewer internal champions, and an opportunity for a focused owner to step in, tighten operations, and harvest the cash flow.

But there was a catch. Douglas Dynamics wasn’t just seasonal. It was weather-dependent. That’s not a normal cyclicality problem you can smooth with better forecasting or pricing. It’s the core input to demand, and management has zero control over it.

Aurora had to answer the question that Harvard Business School later turned into a case study: how do you value—and finance—an LBO when a mild winter can blow a hole in your year?

What Aurora ultimately bet on wasn’t perfect predictability. It was dominance. If you’re going to own a weather derivative, you want to own the one with the brands, the dealers, and the pricing power.

The PE Playbook in Action

Aurora ran a very recognizable playbook: put a steady operator in charge, make the factories better, add smart bolt-ons, and get the whole thing ready for an exit.

Professionalization of Management: Jim Janik, a long-time company leader, became CEO. He wasn’t a parachuted-in turnaround artist. He’d been inside the business since 1992, starting as Director of Sales at Western Products, then running the Western division, and later serving as Vice President of Marketing and Sales. He brought the profile PE firms like most: deep company knowledge, credibility with the organization, and the willingness to install more disciplined processes. His earlier experience included roles at Sunlite Plastics and eleven years at John Deere, which helped shape his bias toward operational rigor and distribution excellence.

Lean Manufacturing Implementation: Aurora pushed systematic operational improvements, including lean manufacturing. The goal was straightforward: reduce waste, improve quality, and increase throughput. In an industrial business, those changes don’t just make the plant manager happy—they expand margins in a way that’s measurable and repeatable. Exactly the kind of improvement you can underwrite in a buyout model.

The Blizzard Acquisition: In 2005, Douglas Dynamics bought the Blizzard Corporation, known for its adjustable-wing snowplows. This is what “platform ownership” looks like in practice: instead of spending years building comparable technology internally, Douglas bought it and moved fast. Not long after, Fisher Engineering introduced the XLS adjustable-width snowplow incorporating Blizzard’s technology—innovation acquired once, then scaled through an already-dominant brand and dealer footprint.

Building the "Work Truck Attachments" Platform Thesis

Aurora didn’t want to own “a snowplow company.” They wanted to own a consolidating platform.

Douglas Dynamics already led North America in snow and ice control equipment for light trucks—snowplows, sand and salt spreaders, and the parts and accessories that keep fleets running. And it sold through some of the most established brands in the category: WESTERN, FISHER, and BLIZZARD. Those brands mattered because they carried something more valuable than awareness: trust, built season after season with end users and distributors.

The strategic pitch during Aurora’s ownership expanded from winter into the broader work truck ecosystem. The logic was intuitive. The same trucks that push snow in January can be used for other jobs the rest of the year—municipal work, construction, landscaping. If you could sell those customers more attachments through the same channels, you’d reduce the company’s dependence on snowfall without having to reinvent the business.

Financial Engineering and Exit Preparation

Of course, private equity wasn’t just improving operations. It was also preparing Douglas Dynamics to stand on its own. That meant the less glamorous work: building reporting systems, tightening governance, and putting in place incentive plans that could translate cleanly to a public-company environment.

The lesson from the PE era was that weather risk didn’t make Douglas uninvestable—it just made it volatile. Strong winters produced tremendous cash flow. Weak winters hurt, but the business could survive them. And because Douglas was the category leader, it had enough pricing power and brand strength to protect margins through the cycle.

Aurora’s bet was simple: you can’t control the weather, but you can own the company that everyone relies on when the weather hits.

V. Going Public: The 2010 IPO & Market Dynamics

Aurora’s endgame was always the public market. Douglas Dynamics completed its IPO in May 2010, and it still trades on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol “PLOW.”

The timing was… complicated. This was the first stretch of real optimism after the financial crisis: the economy was stabilizing, and capital markets were open again. But public investors weren’t exactly hungry for a company whose results could whipsaw based on snowfall totals.

That caution showed up immediately in the pricing. Douglas Dynamics had hoped to sell shares in the mid-teens. Instead, it priced 10 million shares at $11.25 each, raising $112.5 million, after cutting the expected price range. In other words: the company got public, but it didn’t get to do it on its own terms.

On day one, the stock ticked up modestly, trading around $11.80 in morning action. The market’s message was clear: interesting business, real dominance, but we’re not paying a premium for uncertainty you can’t manage.

The reduced pricing reflected a simple problem. Most institutional investors want predictability: recurring revenue, smooth quarters, guidance you can trust. Douglas Dynamics offered the opposite. A big part of demand depends on something management can’t influence, can’t hedge, and can’t “execute” its way out of: winter.

The Public Market Challenge: Explaining Weather Dependency

So the IPO story tried to reframe the company. Douglas Dynamics wasn’t just a snowplow manufacturer, it argued; it was a broader work truck attachments platform. The idea was to sell investors on durability and expansion—growth beyond winter, revenue beyond snow.

It was a reasonable pitch. It also ran into a brick wall called the income statement.

Anyone who looked at the quarterly pattern could see what this business really was. Dealers load up ahead of winter, and the fourth quarter becomes the Super Bowl. Spring and summer, by comparison, are quiet. And the first quarter is the hangover: it depends heavily on whether the inventory that shipped pre-season actually sold through once the storms hit.

No amount of messaging could change the underlying reality: Douglas Dynamics was, and is, a weather-exposed industrial company. A “weather derivative,” except the contract is made of steel, hydraulics, and dealer relationships.

The Seasonality Challenge

Douglas Dynamics has one of the most extreme seasonality profiles you’ll find in a public company. The fiscal fourth quarter typically accounts for roughly half to well over half of annual revenue, driven by pre-season stocking. Then the whole year hinges on what happens next: does winter arrive early, often, and in the right places?

That makes Wall Street’s usual toolkit less useful. Modeling Douglas isn’t just forecasting demand; it’s guessing the weather, then guessing how customers react to the guess, then watching what actually falls from the sky.

But here’s the part that makes the business investable at all: underneath the chaos is an installed base that has to be maintained and replaced. There are hundreds of thousands of plows in use, and they don’t last forever. They wear out on curbs and manholes. They get bent, cracked, rebuilt, and eventually replaced. Harsh winters pull demand forward. Mild winters push it out. Over time, the need doesn’t disappear—it just shifts.

And because snow is a public safety and economic necessity, customers don’t treat this like a discretionary purchase. A city can’t decide to “skip winter.” A contractor can’t bill for lots they didn’t clear. The question usually isn’t whether they’ll buy; it’s when.

Stock Volatility and Investor Psychology

Public investors turned that seasonality into a trading habit. Forecast a mild winter, and the stock tends to sag. A major storm hits a big metro area, and sentiment snaps the other direction. The stock starts moving like a headline-driven instrument layered on top of a real operating business.

That dynamic cuts both ways. It can create sharp drawdowns that have nothing to do with long-term market position—and rallies that can get ahead of fundamentals. The hard part, for any investor, is separating a temporary weather-driven slump from something more serious. Both look the same on a stock chart. Only one actually changes the business.

VI. Building the Platform: Strategic Acquisitions (2011-2018)

Once Douglas Dynamics had a public stock ticker, it also had something else: a tradable currency. And management went to work using it the way they said they would—buying adjacent businesses to widen the product line, pull more dollars through the same channels, and, ideally, make the company less hostage to the forecast.

The pitch was consistent: keep the snow-and-ice core, but build a broader “work truck” platform around it.

TrynEx International (2013)

In 2013, Douglas Dynamics acquired substantially all of the assets of TrynEx, Inc. for $26 million. What it really bought was a set of brands and a much bigger footprint: TrynEx’s SnowEx, TurfEx, and SweepEx lines, plus access to roughly 1,500 authorized dealers around the world across 26 countries. Douglas said the deal should be earnings accretive on a full-year basis and free cash flow positive in 2014.

Strategically, this was a clean bolt-on. SnowEx spreaders paired naturally with Douglas’s plows—many of the same customers who need to move snow also need to spread salt and sand. TurfEx broadened the “attachment” story into turf and landscaping work outside winter. And SweepEx added industrial attachment products that could sell into other maintenance use cases.

Just as importantly, TrynEx brought a global dealer network. Douglas had always been a North American winter machine; this gave it a wider map and the beginnings of an export story.

Henderson Products (2014)

A year later, Douglas stepped up in size and ambition, acquiring Henderson Products, Inc. for about $95 million in cash (subject to post-closing adjustments). Henderson had generated $76 million in net sales over the trailing twelve months ending September 30, 2014.

This deal wasn’t about getting away from snow. It was about owning more of it.

Douglas dominated snow and ice control for light trucks. Henderson was the leading North American manufacturer of customized, turnkey snow and ice control solutions for heavy-duty trucks, focused on state Departments of Transportation, counties, and municipalities. In other words: bigger trucks, bigger systems, and a customer base with a different buying process.

That municipal and DOT-heavy market came with some attractive traits. Budget cycles tend to be predictable. Procurement often rewards proven suppliers. And once a particular system is written into specs and training routines, switching becomes painful. Henderson let Douglas move upmarket into Classes 7 and 8 while staying squarely inside snow and ice control—where the company’s brands and reputation actually mattered.

Dejana Truck and Utility Equipment (2016)

Then came the biggest swing at diversification.

In 2016, Douglas entered into a definitive agreement to acquire Dejana Truck and Utility Equipment for $206 million, including a $26 million performance earn-out provision. The deal was expected to close in the third quarter of 2016, and Douglas did close it on those terms.

Dejana had spent nearly six decades growing into a major upfitter of Class 4 to 6 trucks and commercial work vehicles in the Eastern U.S. It also manufactured storage solutions for trucks and vans, plus specialized equipment like cable pulling gear. Douglas framed the acquisition as a natural extension of the upfit strategy it said it began with Henderson—expanding the portfolio, deepening customer relationships, and widening its geographic footprint.

Operationally, Dejana was a real platform in its own right, with seven manufacturing and upfit facilities totaling about 240,000 square feet across more than 90 acres in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic.

The logic was clear: unlike plows and spreaders, upfitting for utilities, telecom, and construction is year-round. If Douglas could scale that business, it wouldn’t have to explain its entire income statement through snowfall charts.

The Mixed Results of Diversification

Taken together, the strategy worked—just not in the clean, linear way the “platform” narrative implied.

Henderson was the straightforward win. It strengthened Douglas’s leadership in snow and ice by expanding into heavy-duty municipal customers, and it fit the company’s existing muscles: products that have to be trusted, sold into institutional buyers, and supported over long lifecycles.

TrynEx was also a logical add. It broadened the product lineup with complementary spreaders and attachments and brought incremental geographic reach.

Dejana, though, was harder. Upfitting is a different business than building attachments: more labor-intensive, different margins, and different customer relationships. It helped with stability, but it also pulled down margin profile and introduced integration complexity that the snow-and-ice core didn’t have.

And that’s the key takeaway from this era. Douglas Dynamics could add businesses, broaden the catalog, and smooth a few edges—but it couldn’t outrun what it fundamentally was. The company’s deepest competitive advantages still lived in snow and ice control, where brand trust, dealer support, and switching costs are the whole game. Everything else was, at best, a supplement.

VII. The Mild Winter Crisis & Strategic Reset (2015-2017)

If the IPO years were about convincing Wall Street that Douglas Dynamics was more than the forecast, the 2015–2016 winter was the forecast reminding everyone who was actually in charge.

Across the Northeast and Midwest, temperatures ran unusually warm. Snowfall was thin. The storms that normally trigger overtime shifts and frantic dealer reorder calls just didn’t show up. Cities that typically measured winter in feet were suddenly counting inches. Contractors who expected to run their plows night after night barely dropped their blades at all.

And when customers don’t plow, they don’t break cutting edges. They don’t burn through hydraulic parts. They don’t “need one more spreader just in case.” In this industry, weather doesn’t just influence demand. It is demand.

The market reacted the way it always does when a weather-dependent business hits a weather wall. Douglas Dynamics’ stock slid to around $18.50. Even with valuation metrics that made the company look cheap on paper, the psychology was brutal: with Christmas temperatures pushing toward 70 in parts of the Northeast and no snow in sight, investors didn’t want to own a company whose best days require bad weather.

The Financial Impact

By the time the first-quarter numbers came in, investors knew a mild winter would sting. What surprised them was how quickly it showed up in the core segment.

Work Truck Attachments—where the snowplows and spreaders live—saw revenue fall more than 10% to $43.6 million, and operating income dropped sharply to just under $2 million. Work Truck Solutions did what it could to offset the damage, generating $29.7 million in sales and a small operating profit of $818,000, but it wasn’t enough to change the story. When winter underperforms, the company’s center of gravity pulls everything back toward snow.

Management Credibility Crisis

This is where the “platform” narrative ran into the income statement.

Management had spent years talking about diversification—about expanding into adjacent products and smoothing out the seasonality. Two mild winters in a row made the uncomfortable point: the core snow business still dominated results, and the bolt-ons hadn’t meaningfully insulated the company from weather risk.

Investors started asking the question out loud. Was Douglas Dynamics becoming a diversified work-truck platform? Or was it still, fundamentally, a snowplow monopoly with a few side quests?

CEO James Janik didn’t try to spin the weather away. He put it plainly: “The lack of snowfall across our core markets in January and February certainly impacted the business. However, the late season storms in March helped end the season on a positive note and moved the below average season snowfall totals closer to average.”

In other words: we got lucky late, but the winter still wasn’t what it needed to be.

Strategic Response and Reset

The mild-winter shock forced a kind of strategic honesty. Douglas Dynamics could keep talking about escaping the weather, or it could accept what it had always been: a snow and ice control company with enormous share, deep trust, and powerful distribution.

The reset wasn’t about abandoning everything outside snow. It was about tightening the company around what actually worked.

Key moves included:

Enhanced Pre-Season Programs: Pushing dealers to commit earlier, encouraging orders before winter, and improving the pull-through playbook so inventory was positioned ahead of demand instead of chasing it.

Municipal Market Focus: Leaning harder into state DOTs and municipalities, where purchasing is tied to budgets and replacement cycles more than a single warm January.

Cost Structure Rationalization: Continuing operational work to make the business survivable across a wider range of winter outcomes by lowering the breakeven point.

Realistic Expectations-Setting: More direct communication with investors about what drives results—less “we’re not a snowplow company” and more “we are, and here’s how we manage it.”

Management remained optimistic that Work Truck Solutions could help carry more weight in the non-winter months, and that a return to more typical patterns in shipments of commercial snow and ice equipment, parts, and accessories would naturally lift results. But the tone had changed. It was less about reinvention and more about resilience.

The Recovery and Lessons Learned

When the 2017–2018 seasons brought more typical winter weather, results improved. But the episode left a lasting imprint on how the company operated—and how investors viewed it.

The big lesson was simple: fighting your core business is futile. Douglas Dynamics’ real advantages—brand trust, dealer relationships, scale, and switching costs—were concentrated in snow and ice control. Stretching into fundamentally different businesses could add revenue, but it didn’t magically remove the company’s dependence on winter.

For investors, the mild-winter crisis offered a clean framework. Weather volatility isn’t the question. It’s guaranteed. The question is whether the leader can absorb a bad season without losing its position, so that when winter returns, the earnings power returns with it.

Douglas Dynamics proved it could.

VIII. The COVID Surprise & Modern Era (2018-Present)

After the mild-winter gut punch, Douglas Dynamics entered what looked like a rebuilding phase. Instead, it ran straight into one of the strangest economic backdrops in modern history: the COVID-19 pandemic. For a business already tied to forces it can’t control, the next few years were a reminder that the forecast isn’t the only wildcard.

Leadership Transition

At the end of 2018, Douglas Dynamics executed an orderly succession plan. James L. Janik stepped down as President and CEO effective December 31, 2018, and moved into the role of Executive Chairman of the Board. The company elevated its Chief Operating Officer, Robert “Bob” McCormick, to President and CEO effective January 1, 2019, and added him to the Board.

McCormick wasn’t an outside swing. He’d already served as CFO and COO, with credibility across both operations and finance. Janik staying on as Executive Chairman kept institutional memory in the room, but the message was clear: this was a handoff, not a rescue.

The COVID-19 Paradox

When COVID hit in early 2020, the intuitive reaction was that Douglas would get squeezed. Big equipment purchases usually slow in uncertainty. Municipal budgets might get diverted to emergency response. Supply chains were breaking everywhere.

But snow removal is one of those unglamorous services that doesn’t get to pause. Roads still had to be cleared. Essential businesses still needed access. Municipal customers kept buying because the alternative wasn’t “wait a year,” it was “shut down the city.”

At the same time, the broader environment was messy. The outbreak created real hesitation across manufacturing as uncertainty discouraged downstream buyers. Municipalities focused spending on pandemic response, which dampened growth in 2020. The industry rebounded in 2021, and then higher interest rates in 2022 and 2023 weighed on demand for new equipment. The point wasn’t that Douglas was immune—it wasn’t. It was that, compared to plenty of discretionary industrial categories, winter infrastructure held up better than you might expect.

2024 CEO Transition and New Leadership

In 2024, the company went through another transition. McCormick informed the Board of his intention to retire in July 2024 after 20 years of service. He stayed on as a consultant through the end of 2024 to support the handoff. Janik returned as Executive Chairman and, after McCormick’s retirement, stepped in as Interim President and CEO.

Then the company named Mark Van Genderen as President and CEO. Van Genderen had served as President of Work Truck Attachments from 2023 to 2025 and as COO from 2024 to 2025. He succeeded Janik as interim chief executive, while Janik returned to his role as Chairman of the Board.

Van Genderen joined Douglas Dynamics in 2020 after 21 years at Harley-Davidson, where he held multiple leadership roles, including leading the Latin America division, running parts and accessories product development, and leading the riding gear and lifestyle apparel business, including the company’s eCommerce operation.

It’s not hard to see why that experience translated. Both businesses live and die by dealer relationships, brand trust, and serving customers who need the product to work every time. And inside Douglas, Van Genderen had already moved from major operating responsibility to enterprise-wide execution—exactly the path you want before handing someone the keys.

Recent Financial Performance

By 2024, performance snapped back in a way that highlighted Douglas Dynamics’ operating leverage when conditions cooperate. The company reported 2024 revenue of $568.5 million, flat versus 2023, and net income of $55.1 million, up sharply from the prior year. Profit margin rose to 9.7% from 4.1% in 2023.

Adjusted earnings per share increased about 45% to $1.47, up from $1.01 in 2023.

And heading into 2025, the company reported a near-record backlog of $348 million—still elevated compared to historical averages.

The Venco Venturo Acquisition (November 2025)

The next strategic chapter showed up in November 2025, when Douglas Dynamics completed the acquisition of substantially all the assets of Venco Venturo Industries LLC, a provider of truck-mounted service cranes and dump hoists.

Van Genderen framed it as an early move under the company’s “Activate” strategic pillar: acquiring more complex attachments to diversify and balance the portfolio. Venco Venturo, led by three generations of the Collins family, had built a reputation around quality and reliability—exactly the kind of brand DNA Douglas tends to buy, not build.

Venco Venturo was founded in 1952, has been privately owned and operated by the Collins family for more than 70 years, and offers electric light-duty cranes, electric-hydraulic cranes, hydraulic cranes, and conversion/dump hoists for work trucks. Based in Sharonville, Ohio, it employed about 70 people across two facilities serving customers across the United States.

Douglas said the acquisition was expected to be modestly accretive to earnings per share and free cash flow positive before synergies in 2026.

2025 Financial Guidance and Outlook

For 2025, Douglas Dynamics guided to net sales of $610 million to $650 million, adjusted EBITDA of $75 million to $95 million, and adjusted earnings per share of $1.30 to $2.10.

Early results supported the optimism. In Q1 2025, the company reported revenue of $115.1 million, up 20.3% year over year, with earnings per share of $0.09 compared to negative $0.37 in Q1 2024. Gross margin improved to 24.5%, up 470 basis points, and the quarter marked record Q1 revenue.

On the back of that performance, Douglas raised its 2025 guidance ranges, pointing to a mix of favorable weather and stronger execution.

IX. The Business Model Deep Dive

To really understand Douglas Dynamics, you have to get out of the investor deck and into the engine room: how it builds product, how it gets product to customers, and how cash moves through the business when most of the year is “prep” and one quarter is “game day.”

Manufacturing & Supply Chain

Douglas Dynamics runs a multi-site footprint designed around the reality that winter doesn’t wait. It operates regional production capabilities that serve different markets, and it leases fifteen manufacturing, upfit, and service facilities across Iowa, Maryland, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island.

Some of the locations matter not just for logistics, but for identity. Fisher Engineering’s facility in Rockland, Maine still serves the Northeast, preserving the local roots that helped make Fisher a trusted name in the first place. Henderson’s Manchester, Iowa facility anchors the heavy-duty municipal side of the house. Dejana’s facilities along the Eastern seaboard handle the upfitting work—less about blades and spreaders, more about turning a bare chassis into a ready-to-work commercial vehicle.

On the input side, steel is the big swing factor. It’s the primary raw material, and a meaningful driver of cost of goods. With steel prices recently low, the company said steel ran at around 13% of revenue in each of the past two years.

That’s great when steel is cheap. When it isn’t, Douglas faces the classic manufacturer’s dilemma: absorb the spike and watch margins compress, or raise prices and risk demand slowing. The company’s history suggests it has enough pricing power to pass through most commodity increases, but not instantly—there’s usually lag, and that lag can hurt.

Distribution Strategy: The Dealer Network Moat

If manufacturing is the engine room, distribution is the moat.

Douglas sells its lineup under Western, Fisher, and Blizzard through about 710 equipment distributors, along with the parts and accessories that keep those fleets running. That dealer footprint is hard to overstate. Building a national network of qualified, trained dealers takes decades, not quarters—and it’s not something a new entrant can replicate just by offering a slightly cheaper blade.

Dealers aren’t just sales outlets. They install equipment, stock parts, do repairs, and keep customers running when a storm is already underway. Every one of those touchpoints reinforces brand preference, raises switching costs, and makes the relationship feel less like a transaction and more like infrastructure.

The TrynEx acquisition extended that reach even further, adding the SnowEx, TurfEx, and SweepEx brands and access to TrynEx’s network of roughly 1,500 authorized dealers worldwide across 26 countries. It broadened distribution internationally, even if North America remains the core battlefield.

Product Development: Engineering for Durability

Douglas Dynamics doesn’t win by chasing novelty. It wins by building equipment that can take abuse, in the worst conditions, and still show up tomorrow morning.

Snowplows live a brutal life: sub-zero starts, salt corrosion, constant vibration, and impacts you don’t see until you hit them. When a plow fails mid-storm, it’s not an inconvenience. It’s lost revenue for a contractor, a missed service level for a city, and a frantic call to the dealer.

That mindset is embedded in the brands. Fisher, for example, has leaned into a tradition of high-quality snow and ice control equipment and service for more than 75 years, built around the idea that the product has to earn trust in the field, not in a showroom.

The replacement cycle is what makes this all financially real. Douglas estimates a large installed base—around 600,000 units in use—with an average replacement cycle of roughly 7 to 8 years. That base creates steady, replacement-driven demand: plows wear down, corrode, get rebuilt, and eventually get retired.

A mild winter can delay purchases and reduce in-season parts consumption, but it doesn’t erase the need. It mostly shifts the timing.

Financial Characteristics: Seasonality and Working Capital

The income statement is seasonal, but the balance sheet is where you really feel it.

Douglas builds inventory in Q2 and Q3, ships primarily in Q4 ahead of winter, and then collects receivables in Q1. That rhythm creates big working-capital swings and a recurring need for seasonal borrowing.

In 2024, net cash provided by operating activities increased from $12.5 million in 2023 to $41.1 million, driven by favorable working capital changes.

At year-end 2024, the company reported about $5.1 million in cash and cash equivalents, plus roughly $150 million of borrowing availability under its revolving credit facility. It also completed a sale-leaseback transaction in September 2024, which increased cash provided by investing activities by $64.2 million. Of the net proceeds, $42.0 million went toward voluntarily prepaying long-term debt.

In plain terms: the company monetized real estate, kept control of the facilities operationally, and used the cash to de-risk the balance sheet. That’s not flashy, but it’s exactly the kind of capital allocation move that matters in a business where one weird winter can stress the system.

Capital Allocation: Dividends, Buybacks, and M&A

Douglas Dynamics has consistently returned cash to shareholders. For the first quarter of 2025, its board approved a quarterly cash dividend of $0.295 per share, paid on March 31, 2025, to stockholders of record as of March 18, 2025.

Third-party analysis cited the company as having maintained dividend payments for 16 consecutive years. The bigger point isn’t the streak—it’s what it signals. In a business this seasonal, maintaining a dividend through good winters and bad is a choice. It’s management effectively saying: we know this business swings, but we believe the underlying earnings power is durable enough to keep paying you anyway.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Competitive Rivalry: LOW

In U.S. snowplow manufacturing, the roster of meaningful players is short. The biggest names include Douglas Dynamics, Boss Snowplow, and Aebi Schmidt Holding AG. And within light-truck snowplows, Douglas Dynamics is the clear market-share leader.

Yes, there are competitors—Boss, Meyer Products, and a long tail of regional brands—but rivalry stays surprisingly muted. This isn’t a market built for constant price fights. Customers buy on reliability, dealer support, and parts availability, not on saving a few dollars on the blade. And once a fleet standardizes on a brand, switching is painful enough that “let’s try someone else this year” rarely makes sense.

The result is an industry where share doesn’t slosh around much. It stays put. And stability like that is a sign that the real competition happened years ago—and Douglas already won it.

2. Threat of New Entrants: VERY LOW

If you wanted to start a snowplow company tomorrow, you could probably design a plow. What you can’t easily build is everything else: the plants, the inventory, the quality systems, and—most importantly—the distribution and service footprint.

Barriers to entry include: - The capital required for manufacturing facilities and inventory - The decades it takes to build a dealer network that customers actually trust - A brand reputation that only comes from years of performance in real storms - Regulatory certifications and safety standards - Scale economics that punish smaller operators on cost

That’s why no new entrant has meaningfully threatened Douglas Dynamics in decades. The product is only the beginning. The moat is the ecosystem around it.

3. Supplier Power: MODERATE

Steel matters. Douglas can’t simply swap it out for something else, so when steel prices move, suppliers have leverage.

But Douglas isn’t a small buyer. Its purchasing volume gives it negotiating power, and it’s not dependent on just one steel supplier. The same is true for many other inputs—hydraulic components and specialized parts come from multiple sources, keeping any single supplier from holding the company hostage.

So suppliers have influence, but not control.

4. Buyer Power: MODERATE to HIGH

On paper, buyers have clout. Municipal customers run formal bid processes. Large commercial contractors negotiate hard. And when procurement teams can line up multiple vendors, pricing pressure is real.

In practice, buyer power hits a ceiling because switching costs are so high. Operators are trained on specific systems. Fleets stock brand-specific parts. Dealers know how to install and service what they sell. And winter is the worst possible time to learn you chose the wrong equipment.

That’s why total cost of ownership dominates the conversation. A plow that fails mid-storm costs far more than any upfront discount. Serious buyers know it, which is exactly why Douglas’ brands stay sticky.

5. Threat of Substitutes: VERY LOW

There isn’t a true substitute for a snowplow. Liquids and de-icing chemicals help, but they don’t move snow. They complement the plow; they don’t replace it.

Long term, climate change might reduce snowfall in certain places. But where snow does fall, the job remains the same: you still have to physically remove it. And technology hasn’t changed the underlying physics of that problem.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: STRONG

Scale is one of Douglas Dynamics’ quiet superpowers. High volume drives lower unit costs, and big production runs mean engineering and R&D investments get spread across far more units than smaller competitors can manage. Purchasing power helps on raw materials. Distribution costs become more efficient as volume rises.

And scale compounds. Better margins fund better operations and better investment, which reinforces the advantage over time.

2. Network Effects: MODERATE

Douglas’ dealer network creates a practical, industrial version of network effects. More dealers mean better service coverage and faster parts availability. That reliability makes the brands more attractive to customers. More customers make the product line more attractive to dealers.

It’s not a classic two-sided marketplace network effect, but it does create a reinforcing loop that’s hard for smaller competitors to match.

3. Counter-Positioning: WEAK

There isn’t a clever strategic “gotcha” here—no business model choice that entrants make naturally but incumbents can’t copy. Douglas’ advantage comes from accumulated assets: brands, dealer relationships, scale, and operational depth.

4. Switching Costs: VERY STRONG

This may be the biggest one. Switching away from Douglas is rarely just a purchasing decision; it’s an operational upheaval: - Operators resist switching because they’re trained on specific controls and systems - Fleets carry parts inventories that are brand-specific - Dealer relationships are built over years - Municipal procurement specs often bake in familiar equipment - Downtime in winter isn’t acceptable, so customers can’t afford experimentation

Those frictions lock in demand and protect pricing. In a business where reliability is everything, switching costs become a moat you can feel.

5. Branding: STRONG

In this category, brand doesn’t mean glossy advertising. It means confidence.

Douglas’ brands have earned loyalty over decades by showing up—storm after storm—with equipment that works and support that’s available when it matters. For procurement teams and contractors, choosing Fisher or Western is a way of minimizing career risk. It’s a signal that you’re buying proven equipment, not running an experiment with public safety on the line.

6. Cornered Resource: MODERATE

The closest thing Douglas has to a cornered resource is its dealer footprint and the institutional knowledge behind it. Competitors can’t simply “recruit” that network overnight, and they can’t buy decades of manufacturing know-how off the shelf.

Still, there’s no single resource that explains everything. It’s the combination that matters.

7. Process Power: MODERATE to STRONG

Douglas has also institutionalized operational excellence through its proprietary Douglas Dynamics Management System (DDMS), a continuous-improvement approach focused on quality, service, and delivery performance.

Process power is unglamorous, but it shows up where it counts: fewer defects, better on-time delivery, and lower costs. Over time, those advantages become self-reinforcing—because in this market, consistently doing the basics better than everyone else is a competitive weapon.

Overall Power Assessment

Douglas Dynamics’ moat is built on Scale Economies, Switching Costs, and Branding. It’s not a tech moat. It’s an industrial one—earned over decades, protected by distribution, and reinforced every winter when customers choose “the thing that won’t fail” over “the thing that might be cheaper.”

It’s a boring business on the surface. Underneath, it’s a beautifully durable market position.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Thesis

Douglas Dynamics is one of those companies where the bull case and the bear case are the same sentence, depending on your mood: it’s the dominant player in an essential category… whose demand is ultimately decided by the sky.

Bull Case

Durable Monopoly with Dominant Market Share: In light-truck snowplows, Douglas Dynamics sits in a commanding position that has held for decades. That kind of stability doesn’t happen by accident. It’s the result of brands people trust, dealers who can install and service equipment fast, and switching costs that feel unbearable when a storm is already underway.

Infrastructure Spending Tailwinds: When state and local governments invest in infrastructure, they don’t just pour concrete. They also fund the equipment that keeps roads usable. Better-funded municipal customers can modernize fleets, replace aging gear, and expand capacity—especially on the heavy-duty side of snow and ice control.

Municipal Budget Recovery: After the pandemic squeezed public budgets, many municipalities saw revenues recover. And snow removal tends to sit in the “non-negotiable” bucket of essential services. When budgets stabilize, replacement cycles can normalize too.

Climate Paradox: Long-term warming is a real risk, but it comes with a twist. Climate change can also mean more unpredictable and severe winter events. Bigger, messier storms tend to be hard on equipment and can pull replacements forward. Paradoxically, volatility can be good business for the company that supplies the gear everyone scrambles to rely on when the forecast turns ugly.

At the same time, industry commentary points to drivers like changing snowfall patterns, demand for more efficient snow removal, and infrastructure expansion in snowy regions as supportive forces for the broader snowplow market.

Parts and Service Revenue: The more Douglas can grow parts and accessories, the more it leans into a higher-margin, more recurring stream that doesn’t depend entirely on new unit sales. Even in mild winters, fleets still need maintenance, repairs, and replacements—just usually less urgently.

Valuation Opportunity: Because the stock can trade like a “weather headline,” mild winter fears can create windows where the valuation disconnects from the company’s long-term position and installed base.

Consistent Cash Flow and Dividend: The company has maintained dividend payments for 16 consecutive years. In a business this seasonal, that consistency matters. It signals confidence that, across the cycle, the cash generation is durable enough to keep paying shareholders.

Bear Case

Climate Change Long-Term Threat: If secular warming reduces snowfall over decades, the addressable market could shrink. And if snow shifts geographically, Douglas could face a tougher, slower problem: the risk that parts of its dealer footprint and manufacturing footprint become less ideally positioned over time.

Single Bad Winter Risk: This is the one you can’t diversify away entirely. A mild winter can crater earnings. The company has said that low snowfall in core markets can stretch replacement cycles and pressure net sales for both a quarter and a full year.

Diversification Failure: Douglas has tried to broaden beyond snow, but the results have been mixed. The uncomfortable truth is that the company still behaves like a snow business first—and investors will keep treating it that way until the financials say otherwise.

Limited Growth Runway: With high share in a mature category, growth is hard to manufacture. Expansion tends to require either pushing into new geographies or building real scale in adjacent categories—both of which take time and carry execution risk.

Small Cap Liquidity Challenges: With a market cap around $683 million and roughly 23 million shares, the stock can be thinly traded relative to large industrial names. That can amplify volatility and make it harder for bigger institutions to build or exit positions cleanly.

Commodity Input Volatility: Steel and other inputs can swing, and Douglas can’t control those prices. It may have pricing power, but pass-through is rarely instant, and margin pressure can show up before price increases do.

EV Transition Uncertainty: As fleets shift toward electric vehicles, attachments may need redesigns, and installation and service could change. That could create friction in the dealer and upfitter ecosystem that the business relies on.

Regional Concentration Risk: The Upper Midwest and Northeast matter disproportionately. If those core regions have weak winters, the company feels it fast.

What to Watch: Key Performance Indicators

If you want a simple dashboard for Douglas Dynamics, start with two numbers that tell you what’s happening before the income statement does:

1. Pre-Season Order Rates: Orders placed in Q2 and Q3 for winter delivery are the clearest leading indicator. Strong pre-season orders usually mean dealers are confident, inventory is being positioned, and the company has a better shot at a strong Q4.

2. Parts and Accessories Revenue: Watch the mix. If parts and accessories grow faster than new equipment, that’s progress toward a more recurring, more weather-insulated revenue base—and usually a better margin profile.

Beyond that, keep an eye on municipal budget health, snowfall in core markets (including NOAA tracking), and dealer inventory levels. In this business, those three often tell you the ending before the quarter does.

XII. Epilogue & Lessons

Douglas Dynamics’ path from a Midwestern industrial shop to a public-company giant in snow and ice control carries a few lessons that are easy to miss if you only look at it through the lens of quarterly weather charts.

Lesson 1: Boring Monopolies Can Be Beautiful Businesses

Not everything needs to be software. Douglas Dynamics earns its keep the old-fashioned way: scale in manufacturing, deep dealer relationships, brands that signal “this won’t fail,” and switching costs that are brutally real when the roads need to open by morning. Those advantages don’t go viral. They compound slowly, over decades, and they’re hard to copy once they’re in place.

Lesson 2: Fighting Your Core Business Is Futile

The company spent years trying to soften its dependence on winter by pushing into adjacent categories. Some of that helped at the margins, but it didn’t rewrite the plot. Douglas is a snow and ice control business first, with complementary operations around it. Once management leaned into that reality—rather than apologizing for it—the strategy got clearer and execution got tighter.

Lesson 3: Switching Costs and Scale Create Real Moats in Industrial B2B

In theory, buying a plow is just procurement. In practice, it’s training, parts inventory, dealer service, and operational muscle memory. Municipalities can’t gamble on unproven equipment in a blizzard. Contractors can’t afford downtime when they’re billing by the hour and the storm doesn’t care. Those constraints lock in market share more effectively than patents ever could.

Lesson 4: Weather Dependency Looks Like a Bug But May Be a Feature

Weather exposure scares investors because one mild season can punish results. But that same volatility scares off would-be competitors, too. Not many companies want to build a business whose demand curve is controlled by snowfall maps. Douglas did—and by doing it at scale, with trusted brands and a dense service network, it turned a scary input into a kind of natural barrier.

Lesson 5: Private Equity Consolidation Playbooks Can Create Lasting Value

Aurora Capital’s ownership wasn’t just about leverage and an exit. It professionalized the company, pushed operational discipline, and accelerated the consolidation strategy that helped Douglas widen its lead. Not every private equity story is financial engineering. Sometimes it’s focus, execution, and industry rationalization—done well enough that the value persists after the IPO.

Lesson 6: In Industrial Businesses, Distribution Often Matters More Than Product Innovation

Douglas sells Western, Fisher, and Blizzard through about 710 equipment distributors. That network is the business. Dealers don’t just sell; they install, service, and keep fleets running mid-storm. You can build a blade. You can’t quickly build decades of trust, training, parts coverage, and “we’ll get you back on the road tonight” capability.

Final Reflection

Douglas Dynamics is proof that old-economy monopolies can be exceptional businesses—if you can tolerate the volatility that comes with them. The company will likely keep doing what it has always done: dominating a narrow, essential niche where performance matters more than hype.

Next winter, and the winter after that, roads will still need clearing. And a huge share of the trucks doing the work will be running Douglas Dynamics equipment. In a world obsessed with disruption, there’s something quietly powerful about winning by being the reliable choice—year after year, storm after storm.

XIII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Resources for Douglas Dynamics Research:

- Douglas Dynamics 10-K filings (2010-present)—The single best place to understand the business in its own words: seasonality, working capital swings, weather risk, and why the moat holds.

- Douglas Dynamics investor presentations and earnings call transcripts—How management explains strategy, what they emphasize in good winters vs. bad ones, and what they’re watching in the dealer channel.

- The Outsiders by William Thorndike—A great lens for thinking about capital allocation in unsexy, cash-generative businesses like this one.

- Harvard Business School Case: Aurora Capital Group - Douglas Dynamics—A clear look at the private equity logic of buying, operating, and financing a business that behaves like a weather derivative.

- Industry reports from IBISWorld and similar sources—Useful for market sizing and competitive landscape, even if the real story is often in distribution and switching costs.

- Municipal budget and infrastructure spending trend reports—A window into the more stable side of demand: planned replacement cycles and public spending priorities.

- NOAA snowfall data and climate reports for key markets—Because with Douglas, the macro variable isn’t GDP. It’s inches.

- Snow & Ice Management Association (SIMA) publications—On-the-ground industry perspective from the contractors and professionals who live this business every winter.

- Competitor annual reports (Boss, Meyer)—Helpful for triangulating positioning and seeing how others describe the market Douglas dominates.

- Hamilton Helmer's "7 Powers"—A strong framework for making sense of an industrial moat built on scale, branding, and switching costs rather than software.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music