Piper Sandler: From Regional Broker to Middle-Market Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

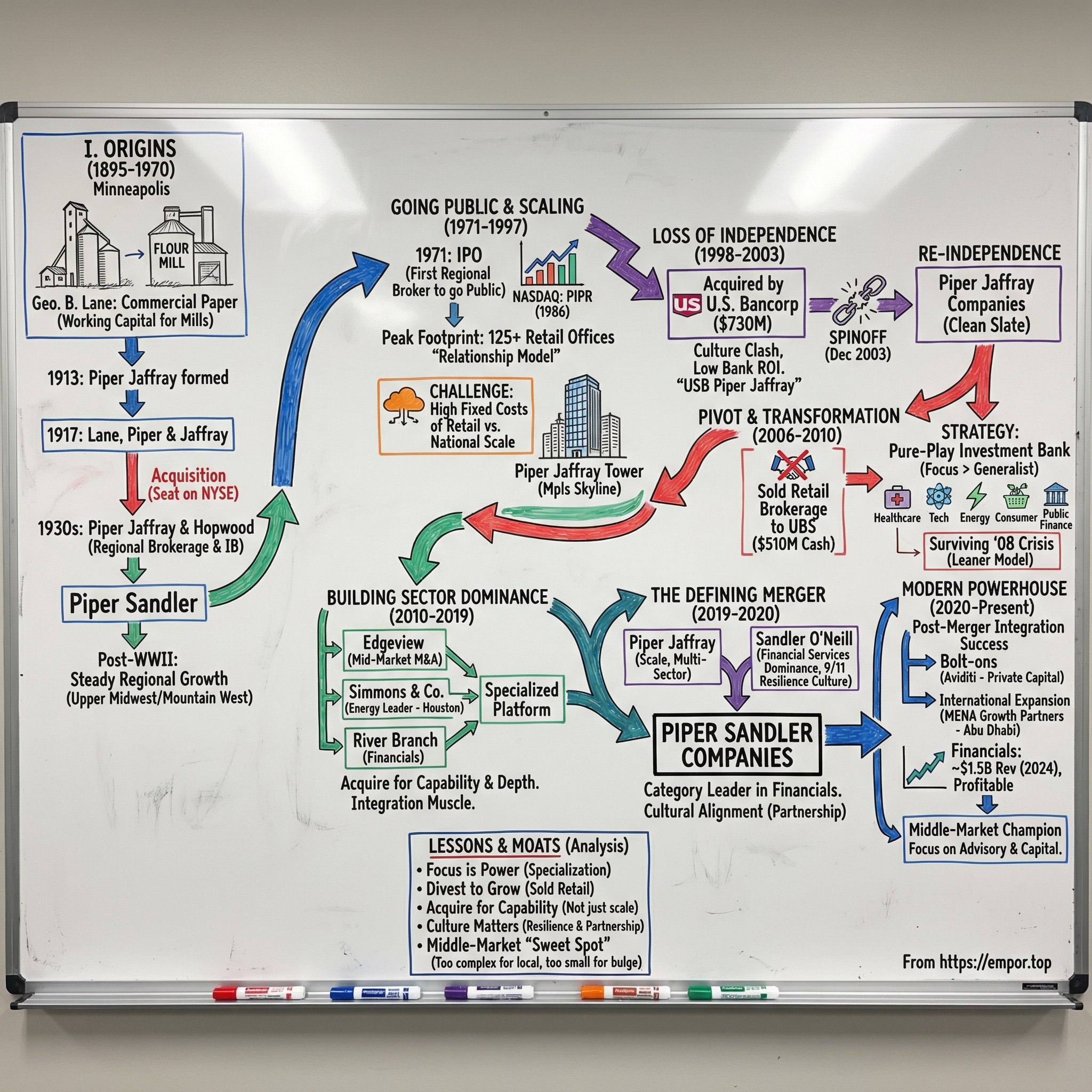

Picture Minneapolis in the spring of 1895. Flour mills along St. Anthony Falls ran day and night, grinding wheat hauled in from the prairies. The whole city pulsed with the logistics of feeding a growing country. And in a modest office off Nicollet Avenue, a young commercial paper broker named George Lane opened shop, arranging short-term financing for grain elevators and millers who needed cash to keep the machinery moving. He called it George B. Lane, Commercial Paper and Collateral Loans & Co.

Lane couldn’t have known he was laying the first stone for what would eventually become Piper Sandler: a Minneapolis-headquartered investment bank that, over the next century-plus, would expand into mergers and acquisitions, financial restructuring, public offerings, public finance, institutional brokerage, investment management, and securities research. Today, the firm operates from more than 60 offices across five countries.

At its core, this is a story about survival and reinvention. How a regional brokerage built to serve the upper Midwest evolved into a specialist platform that now ranks among the most influential advisors in middle-market dealmaking—especially in financial services M&A. The journey is full of pivots: some forced by markets and crisis, others chosen with unusual clarity.

The question driving this episode is simple to ask and hard to pull off: how did a 130-year-old Minneapolis commercial paper broker become a leading middle-market investment bank—one of the trusted go-to advisors for banks, healthcare companies, and energy firms?

The modern results make the transformation hard to dismiss. In 2024, Piper Sandler grew net revenues to about $1.5 billion, and profitability jumped sharply versus the year before. This wasn’t a regional also-ran putting up middling numbers. It was a firm showing what happens when focus stops being a slogan and becomes a strategy.

That’s what we’ll unpack: how independence—lost and regained—shaped the firm’s identity. How divestitures that looked risky at the time created the room to build something bigger. And how one defining merger, with Sandler O’Neill, brought not just category-leading capability in financial services, but a culture forged by tragedy and rebuilt with purpose.

If you care about moats in professional services, the real power of specialization, or why the middle market can be the best battlefield in American finance, this story has a lot to teach. So let’s start where it all began: Minneapolis, the founders, and the world they were financing.

II. The Minneapolis Origins & Early Evolution (1895-1970)

In the 1890s, Minneapolis was the flour-milling capital of America, a city powered by St. Anthony Falls and fed by an almost endless stream of wheat rolling in from the Great Plains. In 1895, George Lane stepped into that world and started George B. Lane, Commercial Paper & Collateral Loans & Co., financing the growth of grain elevators and mills that needed cash long before they needed headlines.

This wasn’t glamorous Wall Street finance. It was the essential, unromantic business of working capital—making sure the machinery kept running and the checks cleared.

Commercial paper brokerage back then meant playing matchmaker between businesses that needed short-term funding and investors willing to provide it. Lane’s edge wasn’t some complex product. It was trust. He had to understand the credit of local enterprises and the expectations of faraway capital, then bridge the two with reputation and relationships.

Nearly twenty years later, Minneapolis produced another version of the same idea. In 1913, two Yale classmates, H.C. Piper and C. Palmer Jaffray, launched Piper Jaffray & Co., also focused on commercial paper. The Yale connection mattered: even in the Midwest, capital markets ran on credibility, and Eastern credentials helped open doors.

In 1917, the two firms merged, becoming Lane, Piper & Jaffray. Then came a subtle but important widening of ambition. During the 1920s, the firm expanded beyond commercial paper into advising on mergers and raising capital in public and private markets. It was an early pivot toward full-service investment banking—and it arrived just in time.

When the Great Depression hit, American finance buckled. Banks failed, securities firms collapsed, and confidence evaporated. Out of that chaos came one of the firm’s most consequential steps: acquiring Hopwood & Company, which had been devastated by the crash. Lane, Piper & Jaffray hadn’t yet been trading listed securities, so it hadn’t taken the same direct blow. The combination created Piper Jaffray & Hopwood—and, critically, brought with it a seat on the New York Stock Exchange.

That NYSE seat wasn’t just a trophy. It was a scarce asset and a direct pipeline into the center of U.S. securities markets. The Minneapolis firm was still regional in footprint, but it now had a real line into Wall Street’s core infrastructure.

After World War II, growth was steadier and more methodical. Almost fifty years after the original Minneapolis founding, Piper Jaffray & Hopwood began pushing west, opening an office in Great Falls, Montana. By the mid-1960s, it had acquired Jamieson & Company and added eight offices—quiet expansion that reflected the firm’s relationship-first approach.

And this is where the culture set. Minneapolis shaped the firm’s DNA: civic-minded, practical, and built for long-term relationships—the kind that matter in agricultural and industrial communities where business ties can last generations. It was a temperament that didn’t chase speculation so much as durability.

By 1970, Piper Jaffray & Hopwood had become a true regional powerhouse across the upper Midwest and Mountain West, offering clients brokerage and investment banking services that went well beyond its commercial paper roots. The next question was the one that would define the coming decades: in a financial world turning increasingly national, could a regional champion stay independent—and stay relevant?

III. Going Public & Building the Regional Champion (1971-1997)

In 1971, Piper made a move that looked almost audacious for a regional brokerage: it went public. It became the first regional brokerage firm to offer its own stock for public sale, with investors buying 300,000 shares of common stock. In an industry still dominated by partnerships, this was a clear signal that Piper wanted more than steady, local success. It wanted the capital to grow.

That decision mattered even more as the decades rolled on. In 1986, Piper’s common stock began trading on NASDAQ under the ticker PIPR, giving the market a straightforward bet: a pure-play regional brokerage that believed the Midwest relationship model could scale.

And for a while, it did. Through the 1980s and into the early 1990s, Piper’s regional footprint hit its peak: more than 125 retail offices across 18 states in the Midwest, Mountain West, and beyond. This wasn’t an outpost strategy. It was a dense network meant to feel local everywhere it operated.

The engine was old-school brokerage at its best. Piper’s advisors weren’t just names on statements; they were fixtures in their communities. They knew families across generations. They showed up at the same events, served on the same boards, and earned trust the slow way—one relationship at a time. In smaller markets, that kind of embedded presence was hard for the wirehouse giants like Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley Dean Witter to replicate.

But success didn’t erase the structural problem hiding underneath: retail brokerage is expensive to run at scale. Trading infrastructure, technology upgrades, and an ever-rising regulatory burden demanded constant investment. The biggest firms could spread those fixed costs across massive client bases. A regional player, no matter how well-loved, felt the weight more directly.

At the same time, Piper kept building out its investment banking capabilities—especially in public finance. The upper Midwest was a natural fit: cities, counties, hospitals, and school districts all needed financing, and Piper’s local relationships made it easier to understand community priorities and navigate local politics.

And then came the physical symbol of the era: the firm moved into a building that carried its name and reshaped the Minneapolis skyline, the Piper Jaffray Tower. It was more than a headquarters. It was a declaration that you could build a serious financial institution far from New York—and mean it.

By the mid-1990s, though, the ground was shifting. Technology was shrinking distance. Wealth was concentrating. The national brands were getting louder. And consolidation—already transforming the banking industry—was creeping into securities firms too.

The question hanging over Piper was no longer whether the regional model could win. It was whether it could keep winning in a world that was rapidly becoming borderless. The firm was about to find out—soon, and not on its own terms.

IV. The U.S. Bancorp Interlude: Loss of Independence (1998-2003)

By the late 1990s, American finance had caught consolidation fever. The walls between commercial banking, investment banking, and insurance were about to come down with the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999. Even before Washington made it official, big banks were already moving as if one-stop financial supermarkets were inevitable—and securities firms were suddenly in demand.

In 1998, Piper Jaffray was acquired by U.S. Bancorp—another Minneapolis institution—for $730 million in cash. From 1999 through 2003, the firm operated under the name U.S. Bancorp Piper Jaffray. For a regional brokerage, it was a hefty price tag, and it reflected just how much franchise value Piper had built over a century.

On paper, the logic was clean. U.S. Bancorp could sell investment banking and wealth management to its commercial banking customers. Piper could tap the bank’s distribution and balance sheet. Cross-selling wasn’t just a strategy; it was the era’s religion.

But the marriage never really worked.

For U.S. Bancorp, the capital markets division—made up primarily of the Piper Jaffray unit—generated $737.3 million in revenue in one year, yet contributed less than 1% of the bank’s overall net income. In a company dominated by commercial banking economics, the securities business wasn’t a core profit engine. It was a business that demanded constant attention, tolerated volatility, and paid its best people like athletes.

And culturally, the two worlds didn’t mix. Investment banking runs on relationships, rainmakers, and incentive-heavy compensation. Commercial banking runs on process, risk controls, and operational efficiency. The incentive structures, time horizons, and management instincts clashed—at every level.

Speculation about Piper’s future started almost immediately, especially after Jerry Grundhofer—U.S. Bancorp’s chairman and CEO, long known to have reservations about owning an investment bank—ended up overseeing the combined organization following Firstar Corp.’s purchase of the old U.S. Bancorp, the investment banking firm’s parent. Eventually, U.S. Bancorp began to put Piper at arm’s length. Then, nearly a year later, it moved to finish the job.

U.S. Bancorp announced it would complete the separation by spinning off the business via a stock distribution to its shareholders, capping years of uncertainty about what it would do with its investment banking and asset management operations.

On December 31, 2003, Piper was independent again. In the spin-off, U.S. Bancorp distributed one share of Piper Sandler Companies (formerly Piper Jaffray Companies) common stock for every 100 shares of U.S. Bancorp common stock.

Independence was restored—but not without scars. The bank-owned years left the firm with drift, distraction, and a dulled sense of identity. Now came the hard part, and the opportunity: with a clean slate, what kind of firm should Piper Jaffray become?

V. The Strategic Transformation: Selling the Brokerage & Pivoting to Investment Banking (2006-2010)

Freshly independent again, Piper Jaffray had to answer a question it had managed to avoid for decades: was it going to be a retail brokerage with an investment banking arm, or an investment bank that happened to have a brokerage?

In 2006, management made the choice—and they made it loudly. Piper sold its brokerage business to Zurich-based UBS for $510 million in cash. Roughly 800 brokers went with it.

It was hard to overstate how counterintuitive this looked from the outside. The retail brokerage was the original franchise. It was the part of the business that made Piper a household name across the upper Midwest. It also produced the steadier, recurring wealth-management revenue that most financial firms love to lean on. Selling it meant trading perceived stability for the lumpy, cycle-driven world of investment banking.

And this wasn’t some distressed fire sale. Piper’s private client business had real scale: 91 branches, almost all west of the Mississippi with a few in the Northeast, and about 840 representatives. The point wasn’t that the brokerage was broken. The point was that it was expensive to keep competitive. Technology, compliance, and infrastructure costs kept rising—and without wirehouse-level scale, those fixed costs bite harder every year.

The UBS deal did two things at once. It removed a capital-intensive business that could quietly drag a regional firm into mediocrity. And it handed Piper more than half a billion dollars in cash—dry powder for a very different identity: a focused, pure-play investment bank.

That clarity mattered because the middle of investment banking is a brutal place to be a generalist. At the top end, bulge brackets like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and JPMorgan dominate the biggest relationships and bring balance sheets when clients need them. At the other end, advisory boutiques like Lazard and Evercore win by offering senior attention and specialized judgment. A “we do everything” middle-market firm risks being the third call—if it gets a call at all.

Piper’s answer was to stop trying to be broadly good and start trying to be unavoidably great. Sector specialization became the strategy: healthcare, technology, energy, consumer, financial services. The goal in each was straightforward: build teams with deep industry fluency, embed relationships with executives, and stack enough closed deals that the next client wouldn’t be taking a risk—they’d be hiring the obvious choice.

Of course, there was still the geographic question. Could an investment bank headquartered in Minneapolis really win national mandates against New York firms? Increasingly, yes. Deals get done in conference rooms and over screens. What mattered was expertise and execution, not the watercooler you stood next to. If anything, Minneapolis offered a quieter advantage: a lower cost base that made it easier to compete on price without giving up profitability.

Along the way, Piper began assembling new capabilities through acquisitions. In 2007, it acquired FAMCO and Hong Kong-based investment bank Goldbond Capital Holdings Limited. In 2010, it acquired Advisory Research, Inc. These were early building blocks—more reach, more tools—but the bigger transformation was still unfolding.

Then came the stress test no strategy can dodge: the 2008–2009 financial crisis. Investment banking revenues fell across the industry as M&A and capital raising seized up. For Piper, the downturn was painful—but it also underscored the value of focus. The firm had already shed the sprawling retail brokerage footprint and the costs that came with it. Leaner and more clearly defined, Piper made it through the crisis intact, positioned to keep building when the market reopened.

VI. Building Sector Dominance: The Acquisition Playbook (2010-2019)

Coming out of the financial crisis, Piper Jaffray leaned hard into a simple idea: if you can’t out-muscle the bulge brackets, out-specialize them. And instead of trying to build every new capability the slow way, it went shopping—carefully. The acquisitions in the 2010s weren’t about getting bigger for the sake of it. They were about becoming unquestionably relevant in the sectors where Piper wanted to win.

In 2013, Piper Jaffray bought Seattle-Northwest Securities Corporation, a move that significantly expanded the firm’s municipal business. That same year, it acquired Edgeview Partners, L.P., a middle-market M&A boutique. Together, the two deals widened Piper’s reach on two fronts that matter in middle-market banking: public finance distribution and advisory firepower.

Two years later, in 2015, Piper acquired River Branch Holdings, bolstering its financial institutions coverage. It also grew its fixed income services group with the acquisition of BMO Capital Markets GKST. At the time, the River Branch deal looked like another smart bolt-on. In hindsight, it did something more important: it planted a flag in financial services that would later matter enormously.

But the marquee move of the decade was the energy bet.

Piper Jaffray reached a definitive agreement to acquire Simmons & Company International, a Houston-based specialist founded in 1974 and one of the largest independent investment banks dedicated to energy. Simmons brought the full kit: M&A advisory, capital markets execution, and investment research, with coverage across energy services and equipment, exploration and production, midstream, and downstream. It also brought a deep bench of professionals—more than 170 across investment banking, sales and trading, equity research, and private equity.

Piper agreed to acquire 100% of Simmons for approximately $139 million, made up of $91 million in cash and $48 million in restricted stock. On top of that, Piper committed an additional $21 million in cash and stock for retention.

The Simmons acquisition changed the firm in two ways. First, it gave Piper instant credibility in a sector where reputation and relationships are everything—and where the center of gravity sits in Houston, not New York or Minneapolis. Simmons itself traced back to a very specific niche: Matthew R. Simmons originally founded the firm to advise the fast-growing energy services sector. Piper didn’t have to spend a decade proving it belonged in energy. Overnight, it did.

Second, Simmons proved the playbook worked. Buying a specialized boutique is the easy part. Integrating it—keeping the talent, keeping the client relationships, and turning “us and them” into “we”—is where these deals usually break. Piper showed it could do the hard part. That integration muscle would become a prerequisite for what came next.

As the platform expanded, so did the leadership bench guiding it. Chad Abraham was a Piper lifer, joining in 1991 as an investment banking analyst. He spent the next 13 years on the West Coast in the technology investment banking group, rising to managing director and head of technology investment banking in 1999. In 2005, he became head of capital markets, and by 2010 he was global co-head of investment banking and capital markets.

Under Abraham and co-head Scott LaRue, the investment banking division scaled dramatically—growing revenues from around $150 million to more than $500 million. And the growth wasn’t accidental. They pushed deeper into energy and financial services, expanded debt capital markets capabilities, and added key offices and talent to meet clients where the action was.

By this point, Piper’s strategy had hardened into something close to a doctrine: be number one or two in every sector you choose to serve. That was counter-positioning in its purest form. Don’t be a generalist middle-market shop. Don’t try to be everything. Pick your battles, then build enough depth that clients feel like choosing you is the safe option.

By the late 2010s, the results were visible. Piper had assembled a platform with real weight: healthcare investment banking with deep subsector expertise; an energy franchise built on Simmons; growing capabilities in technology and consumer; and a public finance business that ranked among the nation’s leaders.

But there was still one glaring gap. Financial services M&A—the business of advising banks, thrifts, and other financial institutions in strategic transactions—was the prize category in the middle market. Piper had started building there, but it didn’t own the space the way it did in healthcare or energy.

Closing that gap would take an extraordinary transaction—and it would require bringing together two remarkable stories.

VII. The Sandler O'Neill Merger: The Defining Transaction (2019-2020)

To understand the Sandler O’Neill merger, you have to understand Sandler O’Neill itself—not just as a financial-services franchise, but as one of the most searing resilience stories on Wall Street.

Sandler O’Neill + Partners, L.P. was founded in 1988 by Herman S. Sandler, Thomas O’Neill, and four other executives from Bear Stearns. From the beginning, they aimed the firm at an overlooked corner of the market: community banks and mid-size institutions. These companies needed sophisticated advice—capital raising, M&A strategy, and help navigating regulation—but were often too small to be a priority for the bulge brackets. Sandler’s bet was simple: take those clients seriously, build deep expertise, and become indispensable.

It worked. Sandler O’Neill grew into a trusted advisor across U.S. financial services, building its business around focus, relationships, and credibility—exactly the traits Piper had been trying to compound in its own sector strategy.

In 1993, Sandler O’Neill moved from Two Wall Street to the South Tower of the World Trade Center, and opened an equity sales and trading division. The World Trade Center offered room to grow and a central perch in the financial world. But it also placed the firm on the 104th floor of the South Tower on the morning of September 11, 2001.

That day, Sandler O’Neill suffered one of the greatest losses of any company. Out of 171 employees, 68 were killed—about 40% of the firm. One third of its partners were lost, along with almost the entire equity desk, the entire syndicate desk, and all of the bond traders. Among those killed were Herman Sandler and Christopher Quackenbush, two of the three senior executives who ran the firm.

The human toll was staggering. On that floor alone, 83 Sandler employees worked that morning. At 9:03 a.m., United Airlines Flight 175 struck the building. Sixty-six of the firm’s employees were killed in the impact and aftermath. Those 66 men and women left behind 76 children.

The third senior leader, Jimmy Dunne, wasn’t there. He would typically have been in the office, but that morning he was trying to qualify for the U.S. Mid-Amateur—something he later credited with saving his life.

Then came the second act of the Sandler story: what the firm did next.

When markets reopened on Sept. 17, 2001, CNBC reported that Sandler O’Neill was out of business. Dunne went on the network two days later to refute it, furious and resolute, vowing the firm would rebuild. Sandler restarted operations as early as September 12, working first from temporary space lent by Banc of America, and later out of the Solow Building in space provided by Bank of America. On September 19—three days after the U.S. financial markets reopened—Dunne told CNBC the firm was open for business.

But the defining choices weren’t just operational. They were moral.

Sandler took care of its people in a way that became a permanent part of its identity. The firm sent every family a check covering the deceased employee’s salary through the end of the year, and within two weeks decided to extend health-care benefits for five years. It agreed to pay full salaries through the end of 2001, plus maximum-level bonuses, and extended health coverage for dependents. Employees and friends raised millions to start the Sandler O’Neill Assistance Foundation, funded by the company, with an explicit mission: to pay 100 percent of the children’s college costs, without regard to merit or need.

The firm also rebuilt with stunning speed. Two months after the attacks, Sandler O’Neill was profitable again. Over the years that followed, it added staff, reopened offices, and grew larger than it had been before 9/11. By Dunne’s account, annual revenues rose by “three or four times,” and profits by “four or five times.”

By 2019, Sandler O’Neill had become exactly what Herman Sandler set out to build—and then some. It published research on about 300 financial institutions across the United States. It retained a private partnership structure even as much of Wall Street moved the other way, and it stood as the largest private investment bank dedicated to the financial sector.

Which brings us back to Piper—because Piper’s biggest remaining gap was the very category Sandler dominated.

On July 9, 2019, Piper Jaffray announced it would buy Sandler O’Neill for $485 million. Chad Abraham would continue to lead the combined company, and the new name would carry both legacies: Piper Sandler Companies.

The strategic logic snapped into place. For Piper Jaffray, Sandler delivered immediate, category-leading strength in financial services and bank M&A advisory. For Sandler O’Neill, Piper offered a broader platform—more sector breadth, a larger capital base, and the ability to serve clients beyond financial institutions while staying true to what made Sandler special.

The name choice mattered. “Piper Sandler” wasn’t just a branding decision; it was an acknowledgement that the Sandler culture—earned through tragedy, rebuilt with purpose—was now part of the combined firm’s identity. Jimmy Dunne became vice chairman and senior managing principal of Piper Sandler. Based in the firm’s Palm Beach office, he remained active in key client relationships and advised across mergers and acquisitions, drawing on decades of work in some of the industry’s largest transactions.

And importantly, the integration was unusually smooth. Both firms were partnership-oriented, relationship-driven, and built around deep sector expertise. Together, they created something neither could have built as effectively alone: a multi-sector investment bank with dominant positions in financial services, healthcare, and energy, backed by institutional brokerage and public finance.

VIII. Piper Sandler Today: The Modern Middle-Market Champion (2020-Present)

The Sandler O’Neill merger closed in January 2020. The timing could hardly have been worse. Within weeks, COVID-19 slammed the brakes on the global economy, froze large parts of the deal market, and sent bankers into a work-from-home experiment no one had ever run at scale.

And yet, the integration held together—remarkably well.

Part of that was structural. Sandler brought clear dominance in financial services, while legacy Piper Jaffray brought real platforms in healthcare, technology, and energy. Because the fit was complementary, there was less painful overlap to unwind. Part of it was cultural. Both firms were built on the same instincts: specialize deeply, stay close to clients, and play the long game. That alignment reduced the friction that normally follows a merger of equals.

What’s striking is that the Sandler deal didn’t mark the end of Piper Sandler’s buildout. It accelerated it.

In 2020, the newly combined firm kept moving, adding capabilities with acquisitions including The Valence Group and TRS Advisors. In 2022, it expanded again with Cornerstone Macro, Stamford Partners LLC, and DBO Partners—moves that broadened the platform into areas like macro research and specialized advisory.

Then, on August 23, 2024, Piper Sandler completed the acquisition of Aviditi Advisors, adding 41 professionals to its private capital advisory group. The logic was straightforward: as private capital took up more oxygen in the market, clients needed help not just with M&A, but with fundraising, secondary solutions, and direct investment capital. Aviditi widened Piper Sandler’s toolkit in exactly those areas.

The firm also kept pushing outward geographically. Piper Sandler Companies (NYSE: PIPR) announced it had entered into a definitive agreement to acquire MENA Growth Partners, a merchant bank based in Abu Dhabi that would serve as its strategic investment banking hub in the GCC region.

The pitch was connectivity: pair MENA Growth Partners’ relationships—built over more than 40 years facilitating the growth of innovative Middle East companies—with Piper Sandler’s sector expertise in areas like energy, infrastructure, chemicals, healthcare, technology, equity capital markets, and private capital advisory.

And the macro backdrop was hard to ignore. As the firm put it, nearly 40% of the world’s sovereign wealth assets are managed from the GCC region, and about two-thirds of the global population sits within an eight-hour flight. In other words: capital, geography, and growth all point in the same direction.

Financial performance has largely validated the strategy. The fourth quarter of 2024 was a standout, with adjusted net revenues of $499 million—Piper Sandler’s second-highest quarterly revenue on record. For the full year, adjusted net revenues were about $1.5 billion, up 16% from 2023.

The engine was investment banking. Revenues across advisory services, corporate financing, and municipal financing rose to about $1.11 billion. Advisory revenues climbed to roughly $809 million on more completed transactions and higher average fees, while corporate financing grew to about $174 million as equity and debt capital-raising activity picked up.

The firm also showed improved operating discipline. Its compensation ratio improved in 2024 versus 2023, and margins expanded meaningfully as revenue growth outpaced costs.

Looking ahead, management has described an aggressive next chapter: keep growing advisory, benefit from a stronger financing environment, expand the geographic footprint, and deepen relationships with private equity clients. The stated ambition is to grow annual corporate investment banking revenues to $2 billion over the medium term.

Public finance remains a major pillar as well. Piper Sandler has ranked No. 2 in underwriting over the last five years and has consistently ranked No. 1 as a placement agent over the same period.

And the heart of the combined firm’s identity—financial services and healthcare—continues to do the heavy lifting. In one recent quarter, corporate investment banking revenues reached $292 million, with strong contributions from both franchises. Piper Sandler has continued expanding these industry teams with additional subsector coverage, product expertise, and tighter connectivity to private equity.

That matters because in investment banking, platforms don’t win—people and reputations do. Piper Sandler’s healthcare and financial services groups are now among the largest in their sectors, led by senior bankers with long tenures at the firm, reinforcing the continuity clients look for when the stakes are high.

The firm has also remained active on marquee mandates. It advised on the largest U.S. bank M&A deal that closed in 2025.

IX. Business Model & Strategic Analysis

So how does Piper Sandler keep winning in a business where the “product” walks out the door every night, competitors will undercut you tomorrow, and a bad quarter can make people forget a decade of great work?

Two lenses help make it click: Porter’s Five Forces (what the industry does to you) and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers (what you’ve built that lasts).

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate-Low

Investment banking looks easy to enter—rent an office, hire a few rainmakers, print business cards. In reality, the barriers are steep. CEO and board relationships take years. Credibility comes from closed deals, and you can’t fake a track record. Regulation and capital requirements add friction too.

Yes, new boutiques form all the time, because talented bankers can leave and take relationships with them. But Piper Sandler’s edge is that it doesn’t just “do deals.” In its core sectors, it’s built real domain expertise. Knowing bank capital requirements or the practical realities of healthcare regulation isn’t something you pick up from a briefing book.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate

In this industry, the suppliers are people: senior bankers, analysts, sales and trading professionals. And they have leverage, because relationships can follow them to the next firm. That’s why compensation is so high across Wall Street—it’s the price of keeping the franchise together.

Piper Sandler tries to blunt that leverage with a culture that looks more like a partnership than a revolving door: long-tenured senior teams, alignment, and incentives designed to keep talent in the building.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

Piper Sandler’s clients are sophisticated. Middle-market CEOs and boards know how to run a process, line up multiple advisors, and push on fees. There are plenty of credible firms that would love the mandate, and that keeps pressure on pricing.

Where that buyer power weakens is in situations where expertise is truly specialized. If you’re a healthcare company with regulatory complexity, or a bank navigating capital constraints and consolidation dynamics, you don’t want a generalist learning on the job. Real specialization creates real stickiness.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate-High

There are substitutes at the edges. Some simple transactions can be done “in-house.” Private equity firms increasingly have internal M&A capabilities. And for smaller deals, tech-enabled platforms can nibble away at the bottom of the market.

But once a deal gets complicated—multiple bidders, regulatory scrutiny, sensitive stakeholder dynamics—the substitute breaks down. For complex middle-market transactions, expert human judgment is still the product.

Competitive Rivalry: Very High

This is as competitive as professional services get. Bulge brackets, elite boutiques like Evercore and Lazard, regional specialists, and sector-focused firms all fight over the same mandates. Fee compression is constant. Talent poaching is part of the business model.

Piper Sandler’s defense is not size—it’s focus. Being known as the expert in a category like bank M&A or healthcare services M&A creates a kind of reputational gravity that’s hard for generalists to match.

Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Limited

Investment banking doesn’t scale like software. Every transaction needs real senior time. You can’t just “ship more units.” That said, some parts of the platform do benefit from scale—research, technology, and distribution for underwriting all get incrementally better when spread across a larger franchise.

Network Effects: Moderate

There’s a flywheel here, just not a Silicon Valley one. Success begets credibility, credibility begets mandates. A strong record in bank M&A leads to more bank M&A opportunities, because clients want the advisor who’s already been in the room for the last ten deals. Research coverage can reinforce this too: more coverage improves insight and access, which improves relevance, which attracts more clients.

Counter-Positioning: YES—This is a Key Power

This is one of the cleanest explanations for why Piper Sandler can thrive alongside giants. Bulge bracket banks could go after middle-market, sector-specific mandates more aggressively. But doing so would pull senior attention away from mega-deals and risk cannibalizing more lucrative large-cap relationships.

In other words: the best competitors are structurally disincentivized to fully chase Piper Sandler’s core business. That’s counter-positioning.

Switching Costs: Moderate-High

Switching costs in banking aren’t contractual; they’re relational. Trust compounds over time. A CEO and board that have worked with an advisor through multiple transactions know how that team thinks, how it negotiates, and how it behaves under pressure.

Clients do switch—especially after a mistake, or when they believe another advisor has sharper expertise for a specific moment. But relationship history is a real friction point, and Piper Sandler benefits from it in its core verticals.

Branding: Strong in Specific Verticals

Piper Sandler isn’t a universal brand across every corner of Wall Street. It doesn’t need to be. Where it matters—financial services, healthcare, energy, and public finance—the name signals credibility. In sectors where it’s less established, the brand naturally carries less weight.

Cornered Resource: YES—Another Key Power

This is the talent-and-relationships business, and the scarcest assets are the people who have both. Senior bankers embedded in community bank ecosystems. Analysts who truly understand specialty pharma economics. Energy bankers who know the decision-makers across oilfield services.

Those relationships and that lived expertise take years to build—and they’re hard to replicate quickly, even with money.

Process Power: YES

Over time, Piper Sandler has built institutional muscle: proprietary sector data, repeatable execution playbooks, and a research engine that reinforces client work. Covering hundreds of financial institutions creates insight that firms without that footprint simply don’t have. And standardized approaches—refined over thousands of transactions—make execution more efficient and more consistent.

Where Piper Sandler Wins

Put it together, and the shape of the strategy becomes clear.

Against bulge brackets, Piper Sandler wins on focus and senior attention: specialists who live inside a sector every day can out-execute generalists juggling everything. Against small boutiques, it wins on platform: research, distribution, and multi-product capability that can support clients across more of what they need.

The “big enough to do anything, small enough to care” line can sound like marketing. In Piper Sandler’s case, it’s also a pretty accurate description of the advantage it has engineered in the middle market.

X. Bear Case vs. Bull Case

🐻 Bear Case

Cyclicality: Piper Sandler lives and dies by market activity. When M&A slows, IPO windows shut, or capital raising gets postponed, revenue can drop fast. Unlike asset managers with recurring fees or banks with net interest income, an investment bank doesn’t have the same built-in stabilizers. In a real downturn, dealmaking doesn’t just soften—it can freeze, and industry investment banking revenues have historically fallen sharply in periods like 2008–2009.

Talent Risk: This is a relationship business, and relationships aren’t owned by the firm so much as carried by the people inside it. If a star banker leaves—whether for a rival, a new boutique, private equity, or retirement—clients can follow. Keeping talent in place is expensive, and even with improvement, compensation tends to remain a large share of revenue. The war for talent never ends.

Fee Pressure: Buyers have gotten smarter and more price-sensitive. Competitive processes are more common, and technology makes it easier for clients to benchmark pricing and pit advisors against each other. That means the fee per transaction can compress over time, especially when many firms are chasing the same mandates.

Middle-Market Squeeze: The middle market can get pinched from both sides. The largest deals increasingly draw bulge-bracket attention, while smaller transactions can be handled by local specialists or tech-enabled platforms. If that “sweet spot” narrows, it raises the bar for maintaining share.

Integration Risk: Piper Sandler has grown by acquisition, and that strategy carries accumulated risk. Every deal adds new systems, new cultures, and new retention challenges. Over time, integration fatigue can set in—or one acquisition can fail to deliver the value that looked obvious on paper.

Regulatory Uncertainty: The firm’s biggest vertical—financial services M&A—depends heavily on regulatory approvals. A tougher stance on bank merger review, or shifts in policy priorities, can slow deal activity right at the center of Piper Sandler’s franchise.

🐂 Bull Case

Irreplaceable Sector Expertise: Piper Sandler’s biggest advantage is depth. Decades of accumulated knowledge in bank M&A, healthcare services, and energy isn’t something a new entrant can copy quickly. In a business where credibility is the product, that kind of specialization becomes a real moat.

Massive Addressable Market: The middle market remains huge—and underserved. The number of U.S. banks has fallen dramatically over the past several decades, but the system is still unusually fragmented. At the end of 2024, there were 4,487 U.S. banks, most with less than $10 billion in assets. That fragmentation is fuel for ongoing consolidation.

"Small banks account for most of the M&A activity across the industry, indicating that there is still no shortage of potential sellers over the coming years. As a result, consolidation will remain a fundamental theme for the industry given the numerous benefits of M&A."

Favorable Bank M&A Environment: A more supportive regulatory tone, paired with improving confidence in the economy, could kick off another wave of consolidation. For the first time since the 2007–2008 financial crisis, agencies like the FDIC and the OCC have been easing certain rules for the industry. And in 2025, bank deal announcements have already surged past all of 2024—signaling that the cycle may be turning.

Diversification Across Sectors: Piper Sandler isn’t a one-trick boutique. It has meaningful franchises across financial services, healthcare, energy, technology, consumer, and public finance. When one sector slows, another can pick up slack—giving the firm more resilience than a single-sector competitor.

Counter-Cyclical Capabilities: Restructuring work tends to show up when traditional M&A dries up. That counter-cyclical capability can help keep the engine running through downturns, when many advisory-only shops feel the full impact of a weak market.

Proven Acquisition Playbook: The firm has shown it can integrate and retain what it buys—no small feat in finance. Simmons in energy and Sandler O’Neill in financial services weren’t just acquisitions; they became pillars. If that integration muscle holds, it’s a repeatable way to add new capabilities and extend leadership in core sectors.

Partnership Culture Creates Long-Term Thinking: A partnership heritage can be a competitive weapon. It supports decisions that prioritize franchise value over quarter-to-quarter optics, and it can help retain talent and deepen client relationships—two things that matter more than almost anything else in investment banking.

Platform Benefits from Cross-Selling: Piper Sandler’s platform lets one relationship turn into many. A healthcare M&A mandate can become an equity raise later. A bank advisory client can become a public finance client. That cross-product connectivity creates growth paths that narrower firms simply don’t have.

XI. Epilogue & Lessons

The Piper Sandler story isn’t just a finance story. It’s a playbook for how professional-services firms survive, sharpen, and win over decades—often by doing less, not more.

Focus is Power

For years, Piper’s identity was tied to being a broad regional brokerage. It served lots of client needs across a wide footprint. But the real breakthrough came when the firm stopped trying to be everything and committed to sector-focused investment banking. In professional services, focus compounds. The narrower the mandate, the deeper the expertise—and the harder it becomes for generalists to keep up. The counterintuitive lesson is that narrowing scope can expand opportunity.

Strategic Divestitures Unlock Value

Selling the retail brokerage to UBS looked, to many observers, like walking away from the company’s heritage. In reality, it bought Piper something more valuable than nostalgia: capital and attention. The $510 million in proceeds didn’t just strengthen the balance sheet; it helped fund the buildout that followed. Sometimes the most strategic move isn’t acquiring. It’s subtracting the business that keeps you anchored to the past.

Acquire for Capability, Not Scale

Piper Sandler’s biggest deals weren’t about getting bigger. They were about getting better. Simmons brought energy credibility and a Houston foothold. Sandler O’Neill brought category leadership in financial services advisory. Aviditi expanded private capital advisory capabilities. The discipline was simple: every acquisition had to answer, “What do we gain that we can’t easily build ourselves?” That mindset is how serial acquirers create value instead of collecting complexity.

Culture Matters More Than Strategy

Strategy sets direction, but culture determines whether the firm can hold the team together long enough to execute. Piper Sandler’s partnership-oriented model supports long-term thinking, collaboration, and the patient relationship-building that investment banking depends on. Firms that treat bankers as interchangeable parts—or as short-term competitors inside the same building—often struggle to sustain trust with clients and cohesion among their best people.

Geographic Origins Need Not Limit Ambition

Piper Sandler is still headquartered in Minneapolis, not New York. In earlier eras, that could have been a real handicap. Today, expertise travels. Technology and remote work have made location far less determinative than reputation and execution. If anything, Minneapolis can be an advantage: a lower cost base and a grounded culture that many clients find refreshing.

Tragedy Can Forge Purpose

Sandler O’Neill’s experience on 9/11—and what it did afterward—shows how tragedy can harden a firm’s identity in ways no strategic plan ever could. The decision to care for families, to rebuild quickly, and to prove the firm would endure created a moral intensity that became part of the culture. No one would choose that catalyst. But the broader lesson holds: purpose, once earned, can become a durable competitive asset.

The Middle Market Is the Sweet Spot

The middle market is large enough to matter and small enough to value senior attention. Bulge brackets chase mega-deals. Tiny boutiques often lack platform capabilities. Piper Sandler built a durable position in the gap: serving clients that are too complex for local advisors but not big enough to be Wall Street’s top priority.

KPIs to Track

For investors tracking whether the story keeps working, three metrics are especially telling:

-

Advisory revenue per managing director: A proxy for pricing power and productivity. If this starts sliding, it can be a sign that growth is becoming more commoditized.

-

Compensation ratio (compensation expense as % of net revenue): In investment banking, compensation is the biggest line item and the clearest signal of competitive intensity. The key question isn’t whether the ratio is high—it usually is—but whether the firm can keep it disciplined while still retaining talent.

-

Senior banker retention: In this business, relationships and expertise live in people. Unusual departures of managing directors and above—especially to direct competitors—can be an early warning sign that something is off, whether that’s compensation, leadership, or culture.

What's Next?

Piper Sandler’s diversified model and acquisition-driven capability building suggest it will keep evolving. Management has pointed to continued growth opportunities in advisory, a healthier financing environment, and further expansion of private equity connectivity. The firm has also shown it’s willing to keep buying in areas where it sees underpenetrated growth—so long as the capability is additive.

International expansion, including the planned Middle East presence through MENA Growth Partners, reads like the next logical extension: take sector expertise and plug it into where global capital is increasingly concentrated. Private capital advisory is another clear vector, as fundraising and secondary solutions become essential services—not optional add-ons.

Zoom out, and the arc is the point. A commercial paper broker financing Minneapolis grain elevators in 1895 became a regional brokerage champion, lost independence inside U.S. Bancorp, then reclaimed it and made the hardest kind of pivot: walking away from the steady business to build the exceptional one.

And despite all that reinvention, something of George Lane’s original instinct still shows through: the idea that knowing businesses deeply and building trust over time is the real product. In an industry that can look increasingly like algorithms and process, Piper Sandler’s rise is a reminder that expertise and relationships—earned the slow way—still win.

The story continues.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music