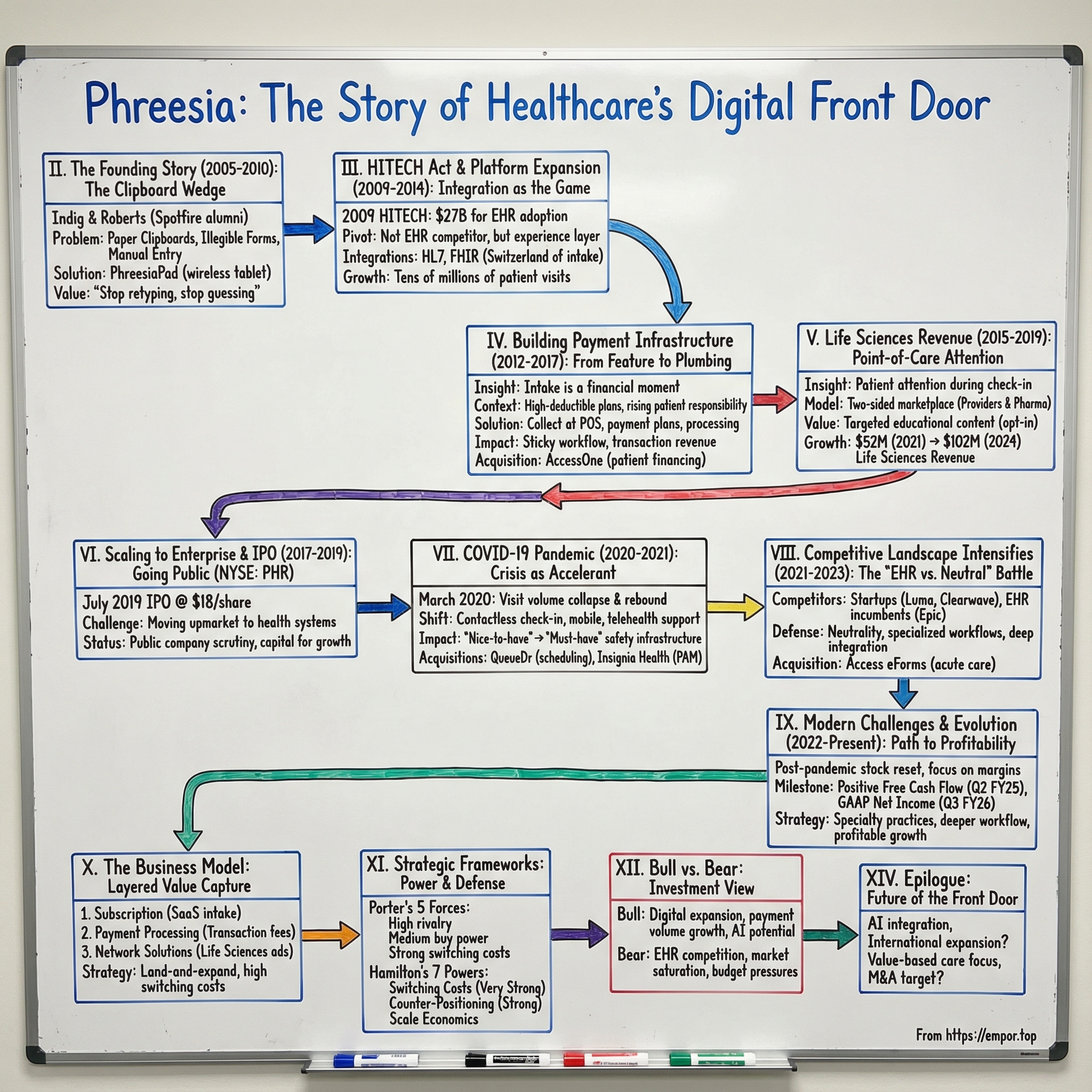

Phreesia: The Story of Healthcare's Digital Front Door

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture the waiting room of almost any American medical practice in 2005. Clipboards stacked high. Dog-eared forms passed from hand to hand. Patients hunched over, squeezing illegible handwriting into tiny boxes. Front-desk staff retyping everything into a computer later, one line at a time. And, inevitably: “Do you have your insurance card?”

It was a scene that hadn’t meaningfully changed in decades. Meanwhile, the rest of the economy was sprinting into the digital age. Banks had ATMs and online portals. Airlines had self-service kiosks. Retail was already training customers to do the work themselves. But healthcare? Healthcare was still running on paper.

Phreesia was founded in January 2005 by CEO Chaim Indig and COO Evan Roberts with an audacious idea that sounded almost obvious: what if checking in for a doctor’s appointment worked more like checking in at an airport? Let patients do it themselves. Digitally. Cleanly. Before they ever saw the clinician.

Fast forward to today, and Phreesia enabled approximately 170 million patient visits in 2024—about one in seven visits across the U.S. That’s not a rounding error. That’s a company quietly sitting in the flow of American healthcare.

In fiscal year 2025, Phreesia reported $419.8 million in revenue, up 18% year over year. But the numbers only tell you what it is. They don’t tell you what it means. Because Phreesia isn’t just replacing clipboards. It’s become infrastructure: a system that shapes how patients enter care, how practices capture the information they need, how money gets collected, and how pharmaceutical companies reach patients right at the point of care.

This is the story of how a “digital check-in” product turned into healthcare’s front door—and what that journey teaches about building vertical SaaS in an industry that hates change. We’ll follow Phreesia from a scrappy New York startup through a series of inflection points: the HITECH Act lighting a fuse under healthcare IT, the pivot into payments, the discovery of a life sciences business hiding in plain sight, COVID turning “nice-to-have” into “must-have,” and the competitive pressure that now threatens to turn today’s differentiators into tomorrow’s table stakes.

Along the way, we’ll pressure-test the business with Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers. We’ll flag the metrics that actually matter if you’re tracking the company. And we’ll keep coming back to the question at the heart of the whole story: is Phreesia a feature that gets absorbed into someone else’s platform, or is it becoming the platform—an operating layer for access to care?

The answer doesn’t just shape Phreesia’s future. It says a lot about how technology finally rewires industries that have spent decades resisting it.

II. The Founding Story & Early Context (2005-2010)

Phreesia starts with two colleagues from Spotfire, an analytics software company that sold into pharma. Chaim Indig helped push Spotfire into pharmaceutical marketing, learning firsthand how data could change behavior in a heavily regulated industry. Evan Roberts, a senior sales engineer, lived closer to the product—building applications, supporting customers, and bridging the gap between what the software could do and what the market actually needed. He also had the engineering chops to ship real systems, not just slide decks.

It was a clean division of labor, and they both knew it. Indig brought the commercial instincts and the industry context. Roberts brought technical depth and product judgment. Together, they’d watched analytics modernize pockets of healthcare-adjacent work. The obvious question was: why did the front door of healthcare still look like 1985?

They didn’t need a grand theory to find the wedge. They just needed a waiting room.

In 2005, the patient check-in process was still built around paper. A receptionist handed you a clipboard. You rewrote the same demographic details you’d written last time. You tried to remember medication names and dosages. You guessed at dates. You signed a form you didn’t really read. Then staff took that paper and manually retyped it into a practice management system—introducing mistakes, losing time, and creating a slow-motion mess that would surface later as billing errors, rejected claims, and frustrated patients.

Indig and Roberts saw something bigger than annoyance. This was operational drag, baked into every appointment. Administrative complexity consumed a meaningful share of healthcare spending. Bad intake data produced bad downstream outcomes. Payments were missed. Eligibility wasn’t verified. And the entire experience signaled, from the first minute, that healthcare was the one major industry that couldn’t—or wouldn’t—modernize.

So they built a literal replacement for the clipboard.

Their first product was hardware-centric: the PhreesiaPad, a wireless touchscreen tablet designed specifically for medical offices—years before the iPad made the idea mainstream. Patients could enter and verify information, complete clinical and administrative forms, sign consents, and even pay copays. And instead of getting stuck in a stack of paper, that data flowed directly into the practice’s systems. The pitch wasn’t “cool new gadget.” It was: stop retyping, stop guessing, stop losing money at the front desk.

Of course, selling into healthcare meant the hard part started after the demo.

The early years were brutally difficult. Clinics didn’t want to change their workflows. Physicians were skeptical of vendors. Implementation took real effort. And because Phreesia was effectively selling hardware to ambulatory practices, it faced thousands of individual purchasing decisions—each one requiring trust, training, and a willingness to disrupt the routine of a front desk that was already overloaded.

This wasn’t an overnight rocket ship. Before going public, Phreesia raised $109 million across nine funding rounds from investors including Polaris Partners, Sandbox Industries, and LLR Partners. It was the kind of patient capital you need when you’re building infrastructure in a market where sales cycles are long and “just ship it” isn’t a strategy.

Along the way, financing helped Phreesia keep pushing. The company announced a $30 million investment led by LLR Partners to accelerate product development and expand nationally. Echo Health Ventures, backed by Cambia Health Solutions and Mosaic Health Solutions, also invested as Phreesia’s network grew—at one point, the company reported managing tens of millions of patient intakes annually.

But the real asset Phreesia was accumulating wasn’t just customers—it was embedment.

Every time a practice rolled out the PhreesiaPad, trained staff, and rewired intake, something important happened: Phreesia stopped being a tool and started becoming part of the daily operating system. The more patient data flowed through it, the more collections improved, the more manual work disappeared, and the harder it became to imagine ripping it out.

In these early years, long before the platform became a platform, Phreesia was already laying the foundation for what would become its strongest moat: switching costs.

III. The HITECH Act Catalyst & Platform Expansion (2009-2014)

If Phreesia’s first years were about proving the clipboard could be replaced, the next chapter was about an external force that dragged the whole industry into the digital era: the HITECH Act.

In 2009, as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the U.S. passed the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act—HITECH. The federal government set aside roughly $27 billion in incentives to push hospitals and clinicians to adopt electronic health records, with additional funding aimed at training and implementation support. The point wasn’t just to buy software. It was to drive “meaningful use”—getting EHRs embedded into real workflows in a way that improved care.

The impact was immediate and structural. Before HITECH, EHR adoption was sluggish. After it, adoption accelerated sharply, and healthcare began a rapid shift from paper-based records to digital systems of record.

For Phreesia, this could have been a disaster. When every practice is suddenly buying an EHR, the obvious fear is that the EHR vendor simply bundles everything—records, scheduling, intake, payments—and squeezes out the point solution.

But HITECH created a second-order effect that turned out to be far more important: it made integration the game.

Once practices had EHRs, they needed everything around the EHR to connect cleanly—registration, forms, insurance capture, patient questionnaires, and eventually payments. And because the EHR market wasn’t one system but many—Epic, Cerner, Allscripts, athenahealth, and plenty of others—no single “native” workflow fit everyone. Every front desk still had its own reality.

This is where Phreesia made the pivot that defined the next decade of the company. Instead of trying to compete head-to-head with EHR vendors, Phreesia positioned itself as the experience layer in front of them: the neutral platform that could plug into whatever system the practice had chosen and make intake actually work.

Technically, that meant meeting healthcare where it was. Phreesia integrated using open standards, including HL7, FHIR, CCD, and even simple file-based formats like CSV when that’s what a practice could support. That flexibility mattered, because in the real world of healthcare IT, “integration” isn’t a checkbox—it’s a thousand edge cases across versions, workflows, and specialties.

Commercially, the message was simple: keep your EHR as the system of record. Let Phreesia run the front door.

That positioning wasn’t theoretical. Customers talked about the pain they were escaping. As Frank Letherby, CEO of Health First Community Health Services, put it: “Phreesia proposed to alleviate all of the registration bottlenecks and pain points by fully integrating with our athenahealth electronic health record and digitizing the patient administrative and clinical intake forms, including collecting copays and balances due, and setting up payment plans – all before the patient even set foot in the clinic.”

Over time, this “works with everyone” stance became a strategic weapon. Practices wanted choice. They didn’t want to be forced into whatever intake tool their EHR happened to ship, especially when the front desk had to live with it every day. Phreesia became the Switzerland of the category—a best-of-breed layer that sat upstream of the EHR and made the rest of the visit run smoother.

And quietly, the flywheel started to turn. Every new integration expanded the addressable market. Every new practice taught Phreesia more about what intake looked like across specialties and patient types. That learning fed product development—more configurable workflows, more tailored forms, fewer bottlenecks.

By the early 2010s, Phreesia was processing tens of millions of patient visits each year. The company had outgrown its original identity as a hardware-centric clipboard replacement. It was becoming a platform—one that could sit in front of the EHR, standardize intake, and reduce the administrative chaos that started the moment a patient walked in the door.

And once you’re sitting at the front door, you start seeing the next problem clearly: money.

IV. Building the Payment Infrastructure Play (2012-2017)

The insight that would transform Phreesia from a patient intake company into healthcare infrastructure came from simply watching what happened at check-in. Patients weren’t only typing in their address and allergies. They were pulling out insurance cards. They were confirming copays. They were being told, sometimes for the first time, that they owed a balance. Intake was already a financial moment—Phreesia was just treating it like an administrative one.

So the question became obvious: if you already have the patient’s attention, the necessary information, and the connection into the practice’s systems… why wouldn’t you collect the money right there?

This is where Phreesia’s model starts to look less like “software that replaces clipboards” and more like a bundle of three businesses that reinforce each other: a SaaS platform for intake and engagement, payment processing, and a life sciences advertising business that would come later. In this chapter, the key move is payments—because payments turn a workflow tool into something closer to financial infrastructure.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Across the 2010s, American healthcare shifted more of the bill onto patients through the rise of high-deductible plans. Out-of-pocket responsibility climbed meaningfully from the 1990s into the mid-2010s, and with it came a brutal operational truth for providers: it’s much harder to collect from thousands of individual patients than from a handful of insurance companies. Patient payments weren’t a rounding error anymore. They were becoming essential to staying afloat.

But most practices were structurally bad at it. They didn’t have great real-time eligibility tools. They struggled to calculate what a patient actually owed. They couldn’t present clear estimates. And they rarely offered modern payment options that made it easy to pay now instead of “later.” The predictable outcome was massive leakage—bills sent out, ignored, disputed, or eventually written off.

And the larger the balance, the worse it got. Industry research showed that a meaningful portion of patients with balances above a couple hundred dollars don’t pay in full within a year. More broadly, a huge share of medical bills goes uncollected, contributing to tens of billions of dollars in bad debt write-offs, including $17.4 billion in 2023 alone.

Phreesia was sitting in the perfect place to attack this. It already owned the moment before the visit. It already had the integrations. It already had the patient’s demographics and insurance details. Adding eligibility checks, copay and balance prompts, payment plans, and actual payment processing wasn’t a detour—it was the most natural extension of the product.

And the business impact was immediate. Phreesia pointed to results like higher point-of-service collections when payments ran through the platform, with most patients paying their copays at the time of service, and a high percentage of scheduled payments successfully collected. Whether you frame it as convenience for patients or cash flow for practices, the effect was the same: this stopped being “nice-to-have” software and started becoming “don’t-touch-this” revenue cycle plumbing.

That shift also created a flywheel. Better collections helped justify the subscription. Once a practice trusted Phreesia with intake, it was easier to expand into payments. More payments volume created transaction revenue for Phreesia. And the transaction stream created a new dataset—one that could be fed back into product improvements, smarter workflows, and more effective billing experiences.

By fiscal 2019, that expansion was clearly showing up in scale. In its SEC filing, Phreesia said it facilitated more than 70 million patient visits for roughly 50,000 providers across nearly 1,600 healthcare provider organizations in all 50 states, and processed more than $1.4 billion in patient payments. Around that time, the company generated close to $100 million in total revenue, with the SaaS subscription business representing about 44% of revenue. Payment processing contributed the rest through fees: it recorded roughly $37 million in fees on that payment volume—about a 2.6% take rate—offset by about $22 million of direct payment processing expense, implying a net contribution closer to $15 million, or around 1% on volume. In other words, payments weren’t just a feature. They were becoming a meaningful business line.

The strategic logic goes even deeper. Intake workflows matter, but payment workflows are sticky. Once a practice has trained staff, wired Phreesia into daily collections, and connected the system to the rest of its financial operations, ripping it out becomes a real operational risk. And unlike subscription revenue—which tends to grow in steps as you add customers and modules—payment revenue can scale automatically with the simple fact that healthcare keeps getting more expensive. As the dollars owed by patients rise, the dollars flowing through the platform rise too.

Phreesia kept pushing further into that direction over time. The company later acquired AccessOne, a healthcare payments and receivables financing platform, to expand its patient payment solutions. According to Visible Alpha consensus estimates, AccessOne is expected to add a modest amount of revenue in fiscal 2026 given the timing of the deal, then ramp significantly in fiscal 2027 and beyond as integration matures, ultimately becoming a meaningful portion of Phreesia’s payment processing revenue.

And then there’s the byproduct Phreesia didn’t set out to collect, but couldn’t avoid once payments were running through the system: insight. When you sit at the front door and handle the transaction, you can see—at a population level—how payment behavior changes by specialty, geography, and economic conditions.

That visibility wouldn’t just shape product decisions. It would help unlock the third leg of Phreesia’s business stool: life sciences.

V. The Life Sciences Revenue Stream & Pharma Pivot (2015-2019)

The third business Phreesia built on top of its platform was the one no one would’ve predicted at the beginning—and the one that tends to spark the most debate. Phreesia realized it was sitting on something pharma values enormously: attention at the point of care.

Think about the setup. Phreesia was already facilitating tens of millions of check-ins a year. During intake, patients were engaged for several minutes, answering questions, confirming details, and getting ready to see their clinician. And because this all ran through a digital workflow, Phreesia could, with patient consent, use information like demographics and condition-related context to deliver content that was actually relevant.

Phreesia’s pitch to the market said it plainly: the platform supports well over a hundred million check-ins each year across mobile, tablets, and kiosks, and it can connect life sciences brands to patients before, during, and after check-in. With consent, Phreesia could show tailored health content at moments when patients are already thinking about their health—and are about to have a conversation that could change their treatment.

By fiscal 2019 alone, Phreesia said it facilitated 54 million patient visits. And once you’re in that flow, the question becomes hard to ignore: why not use some of that time to educate and engage patients on an opt-in basis? It turned out a lot of the industry liked the idea. Phreesia reported that 13 of the top 20 pharma companies were using the platform, and claimed that patients exposed to a brand campaign on Phreesia were, on average, more than four and a half times as likely to have a prescription filled for that product versus control patients.

This became Phreesia’s “Life Sciences” segment: a business selling point-of-care engagement to pharmaceutical and biopharma companies. And it grew into a meaningful revenue stream. Life Sciences revenue rose from $52 million in 2021 to $102 million in 2024—nearly doubling in three years.

The value proposition to pharma was straightforward. Traditional direct-to-consumer advertising is broad and blunt. A TV spot for a diabetes drug reaches everyone watching—most of whom don’t have diabetes. Phreesia offered something radically different: the ability to reach a relevant patient, right before an appointment, when that patient is primed to ask questions and when a clinician conversation is imminent.

Phreesia’s own survey data supported that thesis: 40% of patients said they asked their doctor about pharma brands after seeing them at the point of care, compared to 27% of patients who had seen ads on TV. The company also highlighted an average 5.1x lift in new patient-to-brand conversions.

Strategically, this turned Phreesia into a two-sided marketplace. Providers used Phreesia’s intake and payments platform to run their front door. Pharma companies paid to reach patients moving through that same front door. And the economics were elegant: life sciences revenue could help subsidize the cost of the provider platform, giving Phreesia more flexibility to compete on price while still protecting margins.

But it also raised the stakes. The moment you bring pharma into the check-in flow, privacy and compliance stop being features and become existential. Phreesia had to operate on a regulatory tightrope: patient data used only with appropriate consent, and programs designed to remain compliant with healthcare privacy rules. The company pointed to independent third-party audits and certifications, including Alliance for Audited Media (AAM) certification for transparency in campaigns and DoubleVerify certification to provide assurance that engagement messages were delivered as intended.

And then there’s the softer risk: trust. Some patients and providers might be uncomfortable with pharmaceutical messaging during check-in, even if it’s opt-in and positioned as health education. Phreesia had to balance the commercial opportunity against the potential for reputational backlash.

Still, the strategic outcome was undeniable: diversification. Phreesia was no longer a single-product SaaS company. It now had three distinct revenue streams—provider subscriptions and related services, payment processing fees, and Life Sciences engagement—making the business less dependent on any one buyer, budget, or cycle.

By the time Phreesia approached its IPO in 2019, the company had evolved into something much bigger than a clipboard replacement. It had become a platform with multiple interlocking businesses—each one strengthened by the fact that Phreesia owned the moment a patient enters care.

VI. Scaling to Enterprise & The IPO Journey (2017-2019)

By the late 2010s, Phreesia had done the hard part: it proved that clinics would change their workflows, and that “digital check-in” could actually stick. Now came the even harder part—moving upmarket.

Enterprise healthcare isn’t just “bigger customers.” It’s a different sport. In a small practice, you can win with a strong demo and one champion at the front desk or in the physician group. In a health system, you’re selling through committees: IT, compliance, security, revenue cycle, operations, clinical leadership, and the C-suite. Sales cycles stretch from months into years. And implementation isn’t a few tablets in a waiting room—it can mean thousands of staff, multiple sites, and integrations that have to work across a messy reality of departments, specialties, and sometimes even more than one EHR.

But the prize is enormous. Win one health system, and you don’t just land a logo—you land scale, visit volume, and a deployment that becomes very hard to unwind.

At the same time, Phreesia was reaching a milestone that changes how a company thinks about its next chapter: it was 14 years old, with a real footprint, multiple revenue streams, and a product that had become operationally important to customers. Management began signaling that the moment was right to step onto a bigger stage. As CEO and co-founder Chaim Indig put it around the time of the debut, Phreesia believed the industry was still in the early innings—and that the opportunity ahead was large enough to justify entering the public markets.

In July 2019, Phreesia went public on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “PHR.” The deal was priced at $18 per share, above its initial range, and the stock opened well above that price—an immediate sign that investors wanted exposure to healthcare’s digitization wave.

The IPO did what IPOs are supposed to do: it put meaningful capital on the balance sheet to fund growth. But it also rewired the company’s operating environment overnight. A private company can be patient. A public company is measured every quarter. Analysts model your future. The stock becomes a daily referendum. And decisions that once lived entirely inside the business—how fast to hire, when to prioritize margin over growth, what to build next—suddenly play out under a spotlight.

Still, the public filing and the market response made one thing clear: Phreesia had earned a credible strategic position. It wasn’t just another point solution. It sat in the workflow, integrated into core systems, and touched patients at the exact moment healthcare begins.

The open question—and the one investors were really underwriting—was whether that position would expand into broader platform dominance… or whether bigger players would eventually compress it into a feature.

Phreesia wouldn’t have to wait long for a definitive test. Because the next chapter wasn’t a competitor. It was a global pandemic.

VII. The COVID-19 Pandemic: Crisis as Accelerant (2020-2021)

When COVID-19 hit in March 2020, outpatient healthcare didn’t just get disrupted—it partially shut down. For Phreesia, it was the most extreme stress test imaginable: a company built around in-person visits suddenly watching in-person visits evaporate.

The early data was brutal. In the first wave of the pandemic, visits to ambulatory care providers dropped by nearly 60%. By mid-May, office visits had rebounded meaningfully, but by late June that recovery had largely plateaued—still well below pre-COVID patterns.

Phreesia wasn’t guessing. It could see the collapse in real time because it sat at the front door for more than 50,000 providers. Working with Harvard researchers, Phreesia analyzed visit-volume changes across its client base, turning its platform data into a widely cited read on what was happening to outpatient care. In a moment when policymakers and health system leaders were making decisions with limited visibility, Phreesia’s dataset became one of the clearest windows into the crisis.

But COVID didn’t just reduce volume. It rewrote the requirements for care delivery almost overnight. Providers needed new workflows immediately: pre-visit screening, safer check-in, less time in waiting rooms, better patient communication, and support for telehealth. Phreesia moved to meet the moment, positioning itself as the operational layer that could be updated quickly while EHRs and legacy systems struggled to keep pace.

As the company put it at the time, its goal was to help medical groups and health systems stay safe and continue seeing patients—whether that meant transitioning to telehealth, communicating changes to patients, screening for COVID-19 risk factors, or minimizing contact during in-person visits.

Customers echoed that shift from “efficiency tool” to “essential partner.” Scott Silvestri, CFO of Memorial Health System, said: “We initially chose Phreesia to help us provide a convenient, consistent patient experience and improve efficiency across our system, but they have also become an essential partner in our response to COVID-19.”

Phreesia’s COVID-19 module alone was used in over 45 million patient screenings during fiscal 2021. And as the pandemic evolved, providers used Phreesia’s COVID-19 Vaccination Management Solution to support vaccine delivery and identify vaccine-hesitant patients.

Then came the moment Phreesia had been building toward for years: contactless check-in went from optional to non-negotiable. Waiting rooms—with shared surfaces and close proximity—were suddenly a risk. Mobile check-in, where patients could complete intake on their own phones before arriving or before walking inside, wasn’t just more convenient. It was part of infection control.

Telehealth surged too. Phreesia and Harvard’s analysis showed telemedicine use plateauing around 7% of pre-COVID visit volume—still a more than 70-fold increase compared to pre-pandemic levels. And telehealth wasn’t the only adaptation. Providers layered on universal masking, digital pre-visit screening, virtual or alternative waiting rooms, and mobile registration. The “digital front door” had stopped being a strategy deck concept. It became the minimum viable way to operate.

Memorial Health System’s Director of Patient Access, Missy Fleeman, captured the operational reality: “The timing of our Phreesia implementation was paramount for our health system. I can't imagine how challenging patient encounters would have been throughout the COVID-19 pandemic without a zero-contact intake process. We have been able to keep both our patients and staff safe while still capturing all of the necessary information.”

Investors noticed the same thing providers did: once digital intake becomes embedded as safety infrastructure, it tends to stick. Phreesia’s stock, which bottomed around $26 in March 2020, more than tripled in less than a year, reaching an all-time high closing price of 80.61 on February 9, 2021.

And crucially, the pandemic didn’t just accelerate adoption. It expanded the surface area of what “the front door” could include. Phreesia used the moment to broaden its platform beyond intake and payments into scheduling and deeper engagement.

In January 2021, Phreesia acquired QueueDr, a SaaS scheduling technology company, to enhance its appointments solution. The total consideration included $5.8 million in cash at close, $2.1 million of liabilities incurred, and $2.2 million in performance-related contingent payments. QueueDr became part of what Phreesia now offers clients as Appointment Accelerator.

Then, in December 2021, Phreesia announced the acquisition of Insignia Health, the licensor of the Patient Activation Measure. Insignia held an exclusive worldwide license for the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), created by a research team at the University of Oregon led by Dr. Judith Hibbard, who joined Phreesia in an advisory role. PAM is widely viewed as the gold standard for measuring patient activation, backed by more than 700 peer-reviewed studies over 17 years.

Taken together, these moves signaled where Phreesia wanted to go next. Intake was the wedge. COVID made it urgent. But the long-term ambition was bigger: to understand and shape patient behavior across the journey—helping providers not just process patients, but engage them, schedule them, and move them through care more effectively.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape Intensifies (2021-2023)

As Phreesia’s profile rose, so did the number of companies that wanted to be “the digital front door,” too. Patient intake and engagement wasn’t a sleepy niche anymore. It was a category with gravity—pulling in well-funded startups, adjacent patient-communication platforms, and, most ominously, the EHR incumbents who already owned the system of record.

Depending on how you define the market, Phreesia started showing up alongside names like Clearwave, Solutionreach, Klara, and Weave—tools that overlap in pieces of the same workflow: intake, messaging, scheduling, practice operations. In other parts of the ecosystem, you’d see competitors and near-competitors like Phluence, PatientPoint, RxPx, SOAP Health, and DOCPACE.

Then there were the purpose-built challengers going after enterprise health systems. Luma Health, founded in 2015 and based in San Mateo, is a good example. It offered automated scheduling, referral management, patient communication, and feedback management—exactly the set of modules health systems were shopping for as they tried to modernize access and reduce friction.

But the competitive pressure that mattered most wasn’t coming from startups. It was coming from the EHR vendors.

Epic, the dominant EHR inside large health systems, had its own patient intake capabilities built directly into its platform. And Epic customers weren’t shy about the benefits of that tight coupling—especially during COVID. Users pointed to steady product updates and new pandemic-related functionality, delivered quickly and supported through an existing vendor relationship.

Phreesia’s response was essentially: we win because we’re not the EHR.

Its argument was that neutrality and specialization created advantages that EHR-native tools couldn’t replicate as easily. Phreesia could integrate across different systems, tailor workflows by specialty, and keep iterating on the front-door experience without being constrained by the EHR’s priorities. And customers noticed that focus. As one report put it, “Phreesia respondents say the vendor has continued to innovate and deliver new technology that is relevant and useful to their practices while also working to improve customer relationships.”

Still, the moat here wasn’t just features. It was friction—in the best possible way.

Once Phreesia was embedded into daily operations, with staff trained, workflows configured, and data flowing into downstream systems, replacing it became a real operational lift. That pain compounds in multi-location health systems, where standardizing on one platform creates meaningful value—and where a messy transition can disrupt everything from registration to collections.

That “rip and replace” reality cuts both ways. A practice already using an EHR’s native intake tools also faces switching costs to move to Phreesia. So the competitive battle increasingly tilted toward new implementations, not head-to-head displacement. The question in 2021 through 2023 wasn’t whether Phreesia had a product that worked—it did. The question was whether it could keep winning greenfield opportunities as EHR vendors kept improving what came in the box.

Phreesia also responded the way strong vertical SaaS companies often do: by buying capability and deepening its footprint.

On August 11, 2023, Phreesia acquired Access eForms, LLC, an electronic forms management and automation provider used by hospitals to streamline workflows, improve compliance, and improve the patient experience. The total consideration was $38.4 million, made up of $6.5 million in cash, 1,096,436 shares of Phreesia common stock valued at $30.6 million, and $1.2 million in liabilities. The logic was clear: strengthen functionality in acute care, and expand the network of clients and partners—right as competition for the front door was getting louder.

IX. Modern Challenges & Strategic Evolution (2022-Present)

The post-pandemic reality was sobering for Phreesia shareholders. After peaking in early 2021—when the stock closed at an all-time high of 80.61 on February 9 (and traded as high as 81.59 the next day)—PHR spent the next two years in a long reset, eventually hitting an all-time low of 12.05 on October 30, 2023.

Some of that drawdown had nothing to do with Phreesia specifically. 2022 and 2023 were brutal for growth stocks as interest rates rose and the market abruptly stopped rewarding “growth now, profits later.” But there were also company-specific questions layered on top: growth was slowing from pandemic-era highs, losses persisted, and investors wanted a clearer answer to the simplest question in public markets: when does this become sustainably profitable?

Phreesia’s leadership has been trying to draw a line under that era. “We reached another very important milestone in Phreesia's evolution by crossing over to positive Free cash flow in the fiscal second quarter of 2025,” said CEO and co-founder Chaim Indig. “We believe this milestone marks the start of a new era for Phreesia in which we are able to deploy internally generated cash to drive stakeholder value.”

Around that same period, the company tightened its fiscal 2025 outlook: revenue was narrowed to $418 million to $420 million (from $416 million to $426 million), implying 17% to 18% year-over-year growth. More importantly for how investors were now grading the business, adjusted EBITDA guidance moved up to $34 million to $36 million (from $26 million to $31 million), reflecting both strong quarterly performance and a sharper focus on margins.

Then came an even clearer signal that the business was maturing financially. In its third quarter of fiscal 2026, Phreesia reported revenue up 13% year over year to a little over $120 million, alongside 7% growth in the average number of healthcare services clients to 4,520. And on the bottom line, it posted GAAP net income of nearly $4.3 million, or $0.07 per share—reversing a $14.4 million loss in the year-ago quarter.

That shift mattered. After years of operating in investment mode, Phreesia showed it could generate real earnings—not just adjusted metrics. The company also tightened full-year fiscal 2026 guidance, now expecting $479 million to $481 million in revenue and adjusted EBITDA of $99 million to $101 million, up from its prior $89 million to $92 million range.

And yet, in classic public-market fashion, the stock dropped 23% after the quarter. The reaction appeared to be driven less by the profitability milestone and more by concerns that revenue guidance was a touch lighter than investors wanted. It was a reminder of what changes when you’re public: even when the fundamentals improve, the market can still punish anything that looks like deceleration.

Operationally, Phreesia has kept pushing the strategy that got it here: expand the platform, deepen the workflow, and go where complexity is highest. Recent priorities have included moving further into specialty practices like oncology, women’s health, and behavioral health—areas where intake is more nuanced, workflows vary widely, and the value of a configurable front door is easier to defend.

The company has also continued to collect the kinds of third-party validation that matter in day-to-day buying decisions. In 2025, Phreesia was named to the Capterra Shortlists in the Appointment Reminder and Appointment Scheduling categories—its third and fourth shortlist placements that year—and it reported a 4.3 out of 5 overall rating on Capterra. It also appeared on the 2025 Deloitte Technology Fast 500 for the first time, a ranking of the 500 fastest-growing technology-related companies in North America.

The throughline is straightforward: the pandemic proved Phreesia could become essential. The post-pandemic period has been about proving it can be durable—and profitable—while the market gets more competitive and investors demand real operating leverage.

X. The Business Model Deep Dive

Phreesia’s business model is a study in layered value capture. It isn’t one product with one pricing plan. It’s three revenue streams stacked on top of the same core asset: owning the moment a patient enters care.

Subscription and Related Services is the foundation. Healthcare organizations pay recurring fees to use Phreesia’s intake platform, with pricing generally tied to things like practice size, number of locations, and which modules they deploy. This is the classic vertical SaaS engine: recurring revenue that grows as Phreesia expands its footprint inside a customer.

Payment Processing is the second layer, and it’s where the model starts to look like infrastructure. As patient payments flow through the platform, Phreesia earns transaction-based revenue. The company’s take rate has been about 2.6% on payment volume, and after processing costs, the net take rate is closer to 1%. The important point isn’t the percentage—it’s the direction of travel. As patient responsibility keeps rising, more dollars flow through the front door, and that expands the payment stream without needing a whole new sales motion.

Network Solutions (Life Sciences) is the third pillar: revenue from pharmaceutical and life sciences companies paying for point-of-care engagement. It’s grown into a real business line, with Life Sciences revenue rising from $52 million in 2021 to $102 million in 2024.

What ties these together is the land-and-expand playbook. A practice might start with basic intake. Then it turns on payments. Then it adds clinical screening tools. Then it layers in patient engagement. Each step increases revenue per client, but more importantly, each step makes Phreesia harder to remove. By the time a health system is relying on Phreesia for registration, collections, and patient communications, “switching vendors” isn’t a procurement exercise—it’s an operational event.

That expansion shows up in the metrics Phreesia emphasizes. The company has said it is maintaining its expectation for Average Healthcare Services Clients (AHSCs) to reach approximately 4,200 for fiscal 2025, up from 3,601 in fiscal 2024. It has also said it is maintaining its expectation for total revenue per AHSC to increase in fiscal 2025 compared to the $98,944 it achieved in fiscal 2024.

Put it together and you get something relatively unusual in healthcare IT: diversification built on a single workflow beachhead. If one segment hits headwinds—say life sciences budgets tighten—the others can help steady the overall business. And because all three streams ride on the same front-door presence, they reinforce each other instead of competing for attention inside the company.

XI. Strategic Framework Analysis: Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Competitive Rivalry (Medium-High): Phreesia operates in a crowded, fragmented market. There are plenty of specialists—Luma Health, Clearwave, Solutionreach, and others—going after pieces of the same “front door” workflow. And then there’s the heavyweight competition: EHR vendors like Epic, who can ship native functionality inside the system providers already rely on. In that environment, Phreesia’s differentiation has to come from what’s hardest to copy: deep integration across EHRs, specialty-specific workflows that match real clinic operations, and the compounding advantage of its Life Sciences network.

Threat of New Entrants (Medium): Healthcare is not an easy market to casually enter. HIPAA compliance, security posture, implementation rigor, and especially EHR integration know-how are learned the hard way—and usually over years. That said, “hard” doesn’t mean “impossible,” particularly when well-funded startups decide the prize is worth it. And if big tech ever puts sustained focus on this layer of healthcare infrastructure, it has the capital and talent to become dangerous quickly.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Medium): Buyer power depends on who you’re selling to. Large health systems can negotiate hard, run long RFPs, and demand concessions. Small practices have less leverage. The counterweight is switching costs: once Phreesia is woven into intake, payments, and daily staff routines, changing vendors becomes a project with real operational risk. Still, healthcare budgets are perpetually tight, and even satisfied customers remain price sensitive.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low-Medium): Phreesia relies on EHR integration relationships and payment processing infrastructure, but many of the underlying inputs are relatively commoditized. As Phreesia’s volume and footprint have grown, it has gained more leverage in how it negotiates and partners—reducing supplier power, even if it can’t eliminate the dependency.

Threat of Substitutes (Medium): The most obvious substitute is “just use what the EHR offers,” and those native solutions have kept improving. The other substitute is the oldest one in healthcare: doing nothing and sticking with manual processes. That status quo is shrinking, but it’s still surprisingly persistent, especially in smaller practices where change feels risky and staffing is tight.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis:

Switching Costs (Very Strong): This is the heart of Phreesia’s defensibility. Once it’s embedded—staff trained, workflows configured, integrations tested, data flowing where it needs to go—switching isn’t a simple vendor swap. It’s operational surgery. And the bigger the organization, the more painful it gets: multi-location health systems standardize for a reason, and undoing that standardization is disruptive.

Counter-Positioning (Strong): Phreesia benefits from being the neutral layer. EHR vendors have a built-in tension: if they push too aggressively into “best-of-breed” front-door territory, they risk undermining partners and complicating their own ecosystem. Phreesia, meanwhile, can position itself as the choice-preserving option—working across EHRs and letting providers avoid being locked into a single vendor’s roadmap.

Scale Economics (Medium-Strong): A major chunk of Phreesia’s cost structure is fixed: building and maintaining integrations, security, compliance, and implementation capability. As the customer base grows, those costs get spread over more volume. Payments also benefit from volume economics. And on the Life Sciences side, scale makes the platform more valuable: more check-ins mean more opportunities for engagement, which makes the product more attractive to pharma marketers.

Network Effects (Medium): The clearest network effects show up in Life Sciences. More provider adoption creates more patient touchpoints. More touchpoints attract more pharma demand. More demand improves economics, which can make the provider offering more compelling. It’s not a classic “users directly attract users” dynamic between providers, but the indirect marketplace effect is real.

Branding (Weak-Medium): Phreesia isn’t a household name, and it doesn’t need to be. But within healthcare IT, reputation matters: reliability, security, implementation quality, and support. That brand is meaningful in purchasing decisions, just not the dominant force compared to integrations and workflow fit.

Cornered Resource (Medium): Over time, Phreesia has built assets that are difficult to recreate quickly: a broad integration library, compliance infrastructure, and a large base of patient touchpoints that can be used with appropriate consent. The acquisition of Insignia Health’s Patient Activation Measure also added proprietary IP to the mix—an asset competitors can’t simply replicate with another sprint cycle.

Process Power (Medium): A lot of advantage in healthcare software comes down to execution: implementations that don’t fail, security and privacy operations that hold up under scrutiny, and customer success playbooks built from years of hard-earned experience. Those strengths are difficult for rivals to see from the outside and hard to copy precisely.

Overall Assessment: Phreesia’s strongest powers are Switching Costs and Counter-Positioning, reinforced by Scale Economics and the growing Network Effects of its Life Sciences platform. The question isn’t whether Phreesia has moats—it does. The question is whether those moats can hold as EHR vendors keep improving what comes in the box, and as well-funded competitors keep pushing into the same front-door territory.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Considerations

Bull Case:

The optimistic thesis is that healthcare’s digital transformation still has a long runway. A lot of patient encounters still begin with paper, manual data entry, and downstream clean-up. As “digital front door” workflows become the default expectation, Phreesia’s addressable market naturally expands.

Then there’s the money. The shift toward high-deductible plans keeps pushing more of the bill onto patients, which makes payment collection at check-in less of a nice-to-have and more of a survival skill for providers. Phreesia is already sitting in that moment, so it’s well positioned to keep growing payment volume and attach more revenue cycle capabilities.

The Life Sciences business adds another lever. With campaigns already running for 13 of the top 20 pharma companies, the bull case is that Phreesia’s point-of-care reach has reached a scale that’s hard to replicate quickly—and that scale becomes a real competitive advantage.

AI is the wild card. If Phreesia can use AI to make forms smarter, reduce friction for patients, and give providers better predictive insights, it can widen the gap between “a digital form” and “a system that actually improves operations.” And because Phreesia is embedded in day-to-day workflows, switching costs protect the installed base while the company keeps running its land-and-expand playbook. Finally, the recent proof points on profitability and cash generation support the idea that the model can work at scale, not just in theory.

Bear Case:

The pessimistic thesis starts with the most dangerous competitor: the EHR. If Epic and other EHR vendors keep improving their native intake, scheduling, and payments tools—and bundle them aggressively—Phreesia risks getting squeezed into “optional add-on” territory, especially in large health systems where consolidation is already the default instinct.

There’s also the question of growth. As early adopters mature and the category gets crowded, new customer acquisition can get harder, and expansion inside existing accounts becomes more competitive. Life Sciences, for all its attractiveness, carries its own risks: pharma budgets can tighten, and privacy rules or public sentiment could shift in ways that limit point-of-care engagement.

Competitive pressure isn’t just from incumbents, either. Well-funded startups with modern stacks and tight product focus keep coming for the same “front door” territory. And even if Phreesia executes well, providers are still operating under chronic budget pressure, which makes every additional software line item a fight. The bear case, in short, is that the company ends up in a tougher growth environment while the market continues to value it like a high-growth platform.

Key Metrics to Monitor:

If you want a clean dashboard for how the story is actually unfolding, three metrics matter most:

-

Average Healthcare Services Clients (AHSCs): This is the clearest read on whether Phreesia is still expanding its provider footprint. If AHSC growth slows materially, it’s a warning that distribution is tightening.

-

Revenue per AHSC: This tells you whether Phreesia is deepening relationships—selling more modules, driving more payment volume, and expanding life sciences monetization on top of the same client base.

-

Adjusted EBITDA Margin Progression: This is the proof of operating leverage. As Phreesia shifts from growth-first to durable economics, margin expansion shows whether the business can scale profitably, not just grow.

Together, these three metrics give you the simplest possible narrative arc: Is the network still growing? Is each client becoming more valuable over time? And is the company getting more efficient as it scales?

XIII. Lessons for Founders & Investors

Phreesia’s journey is full of lessons for anyone building—or backing—a vertical SaaS company.

Find the wedge, build the platform. Phreesia began with a problem that looked almost trivial: replacing the clipboard. But that “small” workflow turned out to be the gateway to much bigger value. Once you own intake, you’re sitting in the stream of eligibility, payments, clinical forms, and patient attention. That’s how a single product becomes infrastructure. The founder question isn’t just “what’s a painful problem?” It’s “what pain puts me in the flow of adjacent problems I can solve next?”

Integration as moat. In messy markets with multiple systems of record, the company that becomes the integration layer earns a defensible position. Phreesia’s library of EHR integrations—built over years of real-world implementations—doesn’t just make the product work. It creates switching costs and a time advantage that’s hard for a new entrant to compress.

Two-sided marketplaces in B2B. The Life Sciences segment is proof that you can build marketplace dynamics even in enterprise software. Providers adopt Phreesia to run the front door. Pharma pays to reach patients moving through that same front door. Phreesia captures value on both sides—diversifying revenue and creating a scale-driven flywheel that most vertical SaaS businesses never get access to.

Regulatory complexity as competitive advantage. Healthcare’s rules aren’t optional. HIPAA, privacy expectations, and industry compliance requirements raise the cost of doing business—and that cost becomes a barrier. Teams that can operate safely and credibly inside the regulatory perimeter earn trust, win bigger customers, and face fewer “weekend project” competitors.

Timing matters enormously. Phreesia benefited from multiple tailwinds it didn’t create: HITECH pulled the industry toward digitization, high-deductible plans made payments urgent, and COVID turned contactless workflows into operational necessity. You can’t control macro timing. But you can build in the direction of the trend, and you can be fast when a catalyst hits.

Patience is required. Phreesia was founded in 2005, went public in 2019, and didn’t reach GAAP profitability until 2025. That’s the tempo of healthcare. Sales cycles are long, change is slow, and trust is earned in years. The reward, if you can stick with it, is that the same slowness that makes healthcare hard also makes defensible positions incredibly durable.

XIV. Epilogue: The Future of Healthcare's Front Door

So where does Phreesia go from here? Its stated ambition—to become the operating system for healthcare access—is still big, and still only partially fulfilled. Because as valuable as digital intake is, it’s just one moment in a much longer journey: finding care, scheduling, prepping, checking in, paying, following up, and actually sticking with treatment.

AI is the next wave that could either widen Phreesia’s moat or wash it out. Imagine intake that changes in real time based on how a patient answers, so nobody gets buried in irrelevant questions. Or analytics that flag likely no-shows and unmet needs before they become expensive problems. Or ambient documentation that captures what happens in the encounter so less of the burden falls on forms and staff. Those are the kinds of capabilities that could make Phreesia feel less like “digital paperwork” and more like a smart front door. But they’re also the kind of capabilities that could get bundled and commoditized by larger platforms with more resources and deeper AI stacks.

Then there’s geography. International expansion is still largely unexplored, and it’s not obvious how portable the model is. Phreesia was built for the uniquely American mix of fragmented providers, complex insurance, and high out-of-pocket payments. Other countries’ healthcare systems don’t always have the same incentives—or the same payment pain—which means Phreesia’s wedge may not cut as cleanly elsewhere.

The shift toward value-based care is another wildcard that could pull Phreesia deeper into the core of healthcare operations. As reimbursement moves from “how much did you do” to “how well did it work,” engagement and activation stop being soft concepts and start being economic inputs. In that world, measuring and improving patient activation matters more, and Phreesia’s acquisition of the Patient Activation Measure gives it a credible entry point.

And of course, there’s M&A. Phreesia could keep buying its way into adjacent workflows—rolling up smaller patient engagement vendors to broaden the platform and lock in more of the journey. Or Phreesia itself could be the target: an EHR vendor that wants a best-of-breed front door, a healthcare services company that wants a technology layer, or a private equity firm that sees recurring revenue plus high switching costs and starts doing the math.

The most striking thing, after all the research, is how essential Phreesia has become while staying largely invisible outside healthcare. It processes roughly one in seven patient visits in the U.S., helps move billions of dollars in patient payments, and gives pharma a channel at the exact moment health decisions get made—yet most people couldn’t pick the name out of a lineup.

Maybe that’s the final tell. The best infrastructure doesn’t seek attention. It just works. Phreesia has quietly become the plumbing of healthcare’s digital front door. Whether it evolves from plumbing into platform—or gets treated like a utility that someone else eventually bundles—will go a long way toward deciding whether the story from here is upside… or a warning.

XV. Further Reading

If you want to go deeper on Phreesia—and on the broader healthcare IT landscape it’s riding—these resources are a strong place to start:

- Phreesia S-1 Filing (2019) - SEC.gov - The IPO prospectus lays out the business model in plain terms, along with the historical financials and the risks the company itself thought mattered most.

- KLAS Research reports on patient intake management - The closest thing healthcare IT has to a trusted scoreboard: vendor comparisons, customer feedback, and how buyers talk about switching costs in the real world.

- Health Affairs (HITECH Act and EHR adoption) - Academic work on the policy catalyst that reshaped the market Phreesia grew up inside.

- Phreesia quarterly investor letters and earnings materials - ir.phreesia.com - The most direct window into management’s strategy, what they’re emphasizing, and how priorities have shifted over time.

- Commonwealth Fund COVID-19 impact studies - The Harvard + Phreesia research that tracked outpatient visit-volume collapse and recovery, using real platform data during the pandemic.

- Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA) reports - Good industry-level context on the patient payment problem, revenue cycle pressure, and why “pay at check-in” became so important.

- HL7 FHIR standards documentation - For the technical underlayer: how modern healthcare data exchange is supposed to work, and why integrations are such a durable moat.

- Vertical SaaS case studies (Battery Ventures, Bessemer) - Frameworks for understanding the playbook Phreesia ran: land-and-expand, switching costs, and category creation in a slow-moving industry.

- Research on healthcare administrative costs - The “why this exists” background: the scale of administrative burden and how much money leaks through broken workflows.

- Phreesia customer case studies - phreesia.com - Practical examples of how implementations roll out, what gets adopted first, and what outcomes customers highlight when they’re happy.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music