Pfizer: From Brooklyn Chemical Shop to Global Vaccine Pioneer

Introduction and Episode Roadmap

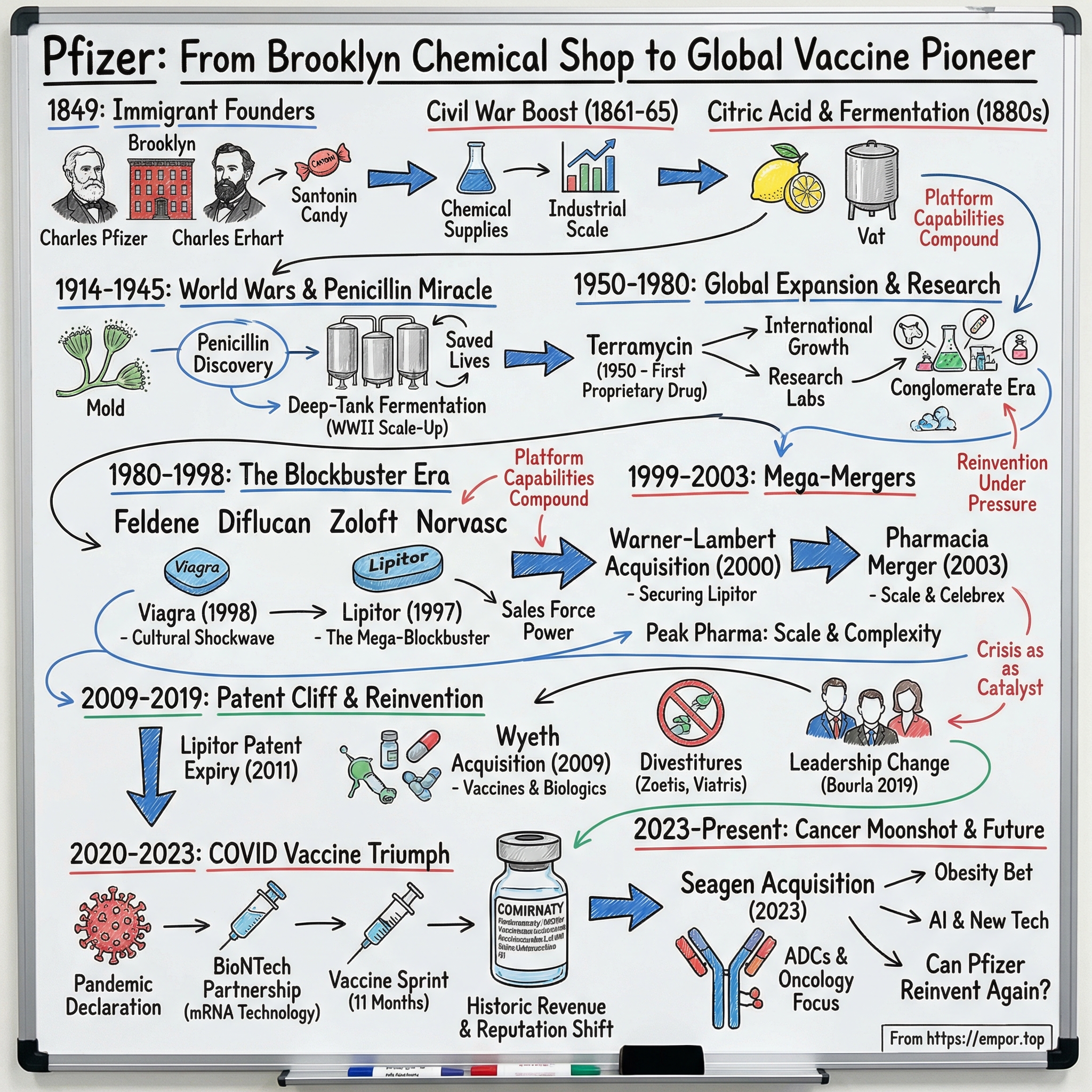

How did two German immigrants selling candy-coated worm medicine in 1849 Brooklyn end up building the company that helped deliver one of the most widely distributed vaccines in history? The answer runs through the Civil War, two world wars, accidental blockbuster pills, hostile takeovers, and a pandemic that briefly made Pfizer feel like the most important company on Earth.

This isn’t a straight-line success story. It’s a story of reinvention under pressure: a company that keeps running into moments that could have broken it, and instead comes out the other side as something new. Pfizer begins as a chemical supplier, becomes an antibiotics pioneer, evolves into a blockbuster drug machine, and then—almost unbelievably—reemerges as a vaccine and antiviral powerhouse. Across 175 years, the pattern stays consistent: scientific innovation sparked by necessity, mergers and acquisitions used as a strategic weapon, and crisis acting as the forcing function for transformation.

Today’s Pfizer—roughly a $146 billion company with more than $60 billion in annual revenue—barely resembles the red brick building in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where it started. And yet the throughline is real. The fermentation know-how Pfizer built to make citric acid in the 1880s later enabled mass penicillin production during World War II. That industrial-scale manufacturing muscle, refined over decades, is part of what made billions of COVID vaccine doses possible. In pharma, platform capabilities compound. Sometimes across centuries.

The arc of Pfizer’s story also maps to the arc of American capitalism: immigrant entrepreneurship in nineteenth-century Brooklyn; industrial-scale production supercharged by war; international expansion during Cold War globalization; the blockbuster era of modern healthcare; and, finally, the crisis-response chapter that produced the fastest vaccine development the world had ever seen.

Along the way, Pfizer created some of the most recognizable drug names on the planet—Lipitor, Viagra, Zoloft, Celebrex, Prevnar, Comirnaty—and pulled off some of the biggest mergers in corporate history. Over and over, it has proven a counterintuitive rule of business: the greatest growth often comes from the darkest moments.

This is the story of Pfizer—from chemicals to antibiotics to blockbusters to vaccines—and the question hanging over it today: can a 175-year-old company reinvent itself one more time?

Immigrant Founders and Chemical Origins (1849-1900)

In 1849, two cousins arrived in America from Ludwigsburg, Germany, with a rare kind of complementary skill set. Charles Pfizer was a trained chemist who had apprenticed under Karl Friedrich Mohr, one of the leading analytical chemists of the era. Charles Erhart was a confectioner—someone who understood sugar, texture, and, most importantly, how to make something people actually wanted to swallow.

They pooled $2,500—borrowed from Pfizer’s father—and opened a small operation in a red brick building on Bartlett Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Their first hit was a product that reads like a metaphor for Pfizer’s entire future: take santonin, a bitter compound used to treat intestinal worms, and hide it inside almond-flavored toffee.

The insight was simple and commercially powerful. Medicine that tastes awful doesn’t get taken. Medicine wrapped in candy does.

That wasn’t a gimmick. In mid-nineteenth-century America, intestinal parasites were widespread, especially among children, and the remedies were so unpleasant that “compliance” was the problem. Parents couldn’t get kids to take what doctors prescribed. Pfizer and Erhart solved it by combining chemistry with confectionery—a small, practical innovation that hinted at something bigger: drugmaking isn’t just about what works in a lab, it’s about what works in real life.

The early years were grind-it-out years. Brooklyn in the 1850s was a noisy, crowded industrial district, dense with immigrant families and ringed by shipyards and factories along the East River. The chemical business was competitive and unforgiving. Pfizer and Erhart weren’t running a sleek research organization; they were working shoulder to shoulder—mixing chemicals by hand, tending fires under reaction vessels, and hauling their own deliveries.

And there was no real safety net. No FDA. No clinical trials. Little meaningful intellectual property protection. If you could copy a formula, you did. In that world, the only durable advantage was trust: consistency, purity, and relationships with the pharmacists and druggists who decided what to stock. If your product was reliable, you got repeat orders. If it wasn’t, you were gone. That pressure built a quality-first mindset that would stick with the company for generations.

Then the Civil War arrived—and with it, Pfizer’s first major growth catalyst. When fighting began in 1861, the Union Army suddenly needed huge quantities of medical and chemical supplies, and Pfizer was positioned to fill orders. The company supplied tartaric acid and cream of tartar, along with chemicals like iodine, morphine, and chloroform. Revenue jumped, but the deeper change was operational. Meeting military demand forced Pfizer to scale manufacturing, tighten processes, and deliver consistent quality at volumes far beyond a neighborhood business.

War wasn’t just a boost in sales. It was a forcing function that pushed Pfizer to become an industrial operation.

That pattern would repeat throughout the company’s history: crisis doesn’t just create demand; it forces Pfizer to level up.

The next leap came from something far less dramatic than war, but just as transformative for the business: citric acid. In the 1880s, demand surged as the food and beverage industry expanded. Coca-Cola was invented in 1886, and soft drinks quickly became major consumers of citric acid for flavoring. At the time, citric acid largely came from imported citrus—lemons, especially—from Italy. That meant supply was expensive, unpredictable, and vulnerable to harvest swings and shipping disruptions.

Pfizer responded by investing in fermentation, building expertise in using biological processes to make chemicals at scale. The underlying idea was that microorganisms could convert sugar into valuable compounds more reliably than global agriculture and trade could. It was a strategic choice that probably didn’t feel like destiny in the moment, but it became one. The fermentation capabilities Pfizer built in this era would later prove essential to one of the most important manufacturing achievements of the twentieth century: producing penicillin at scale during World War II.

By 1900, Pfizer had outgrown its origin story. The company incorporated in New Jersey as Charles Pfizer & Company Inc. Charles Erhart had died in 1891, and control consolidated within the Pfizer family. By the time founder Charles Pfizer died in 1906, his youngest son, Emile, had already become president the year before. Sales had climbed past $3 million—large for the era. The company had moved from Brooklyn to a larger facility in Manhattan and was expanding westward, establishing itself as one of America’s leading chemical manufacturers.

The lasting lesson from this first chapter is subtle but crucial: Pfizer didn’t win by inventing santonin or discovering citric acid. It won by making existing compounds easier to take, easier to trust, and easier to produce at scale. That “best-at-scale” muscle—manufacturing reliability, quality control, and operational execution—would become one of Pfizer’s defining advantages. In pharma, discovery matters. But the company that can consistently make and ship at massive scale often ends up shaping the world.

World Wars and the Penicillin Miracle (1914-1945)

World War I did what wars always do to business: it snapped supply chains. For Pfizer, the break was existential. The company’s citric acid operation depended on calcium citrate imported from Italy. Once Europe was at war—and Mediterranean shipping became unreliable at best—Pfizer’s most important product line suddenly looked fragile.

The escape hatch came from an unlikely place: a mold.

At the U.S. Department of Agriculture, food scientist James Currie had been experimenting with Aspergillus niger, a common fungus. He found that, under the right conditions, it could convert ordinary sugar into citric acid through fermentation. No Italian imports required. Just microbes, vats, and process control.

Pfizer licensed Currie’s work and, in 1919, put the method into commercial production. It didn’t just patch a wartime hole. It rewired the business. Instead of being hostage to lemon harvests and shipping lanes, Pfizer could make citric acid industrially from commodity sugar. Within a decade, the company had effectively cornered the global citric acid market. What started as a survival move became the most important manufacturing capability Pfizer had built to date.

In the years between the wars, Pfizer kept climbing the learning curve of industrial biochemistry. Dr. Richard Pasternack developed a fermentation-free method to produce ascorbic acid—vitamin C—and Pfizer became the world’s leading producer. This wasn’t just another product. It was another round of operational upgrading: tighter controls, larger batches, better purification, more consistency. The vitamin boom of the 1920s and 1930s gave Pfizer a steady stream of demand and, more importantly, a reason to keep sharpening the same underlying skill: turning biology into reliable, scalable manufacturing.

Then World War II arrived—and with it, the moment that would change what Pfizer was.

Alexander Fleming had discovered penicillin back in 1928 after noticing a mold contaminant killing bacteria in a petri dish. But discovery is one thing; production is another. For years, penicillin was a lab curiosity because nobody could make enough of it. The Penicillium mold produced tiny yields and was usually grown in shallow trays, in thin surface layers. It was slow, temperamental, easy to contaminate, and hard to scale. Penicillin also degraded quickly, making storage and transport tricky even when you could produce it.

In 1941, the U.S. government—desperate to prevent soldiers from dying of infection—asked American companies to solve the manufacturing problem. Several firms joined the effort, including Merck, Squibb, and Lederle. Pfizer made the boldest bet: deep-tank fermentation at full commercial scale.

Instead of growing mold in trays, Pfizer proposed growing it submerged in enormous tanks, continuously aerated and agitated. It sounds straightforward until you try it. The organism needed precise temperature, pH, and oxygen control. One contamination event could wipe out an entire batch. The tanks themselves had to be custom-built for biological production at a scale that was almost unheard of.

Pfizer converted an old ice plant in Brooklyn into a penicillin factory and installed rows of 7,500-gallon fermentation tanks. This is where that earlier citric acid story stops being background and starts being destiny. Decades of fermentation experience meant Pfizer already understood how to run large biological processes, maintain sterile conditions, and troubleshoot the messy reality of scaling life in steel. By D-Day in June 1944, Pfizer was producing the majority of the penicillin used by Allied forces—helping turn once-deadly wound infections into something doctors could actually treat.

Penicillin didn’t just deliver revenue. It delivered identity. Pfizer incorporated in Delaware in June 1942, a corporate restructuring that matched its growing ambitions and the scale of what it was becoming. By the end of the war, its facilities were producing enough penicillin to treat hundreds of thousands of patients. The War Production Board awarded Pfizer the Meritorious Service Award, recognition that its contribution wasn’t incremental—it was critical.

Internally, the shift was even bigger. Before penicillin, Pfizer was a chemical manufacturer that happened to sell medical ingredients. After penicillin, it had proven it could manufacture medicine at a scale that saved lives. That changed how employees saw the company, and how the outside world saw it. Pfizer could attract scientists who wanted impact, not just industrial work. It could credibly call itself a pharmaceutical company.

And like so many wartime miracles, the success carried its own expiration date. By 1950, government contracts had ended and more than twenty companies were producing penicillin. Supply exploded, competition intensified, and penicillin began to commoditize. Margins shrank. The very product that had elevated Pfizer was turning into a low-margin bulk business—exactly the kind of trap the company would spend the next decades trying to avoid.

Pfizer was at a crossroads: drift back toward being a scaled chemical producer, or push forward into the riskier world of proprietary drug discovery. The choice it made would define the next era of the company.

The International Expansion and Research Revolution (1950-1980)

Pfizer’s shift from chemical manufacturer to true pharmaceutical company started, fittingly, in the dirt.

In 1950, Pfizer scientists isolated oxytetracycline from a soil organism. It was a broad-spectrum antibiotic, and Pfizer branded it Terramycin—“terra,” as in earth, a nod to where it came from. Terramycin could treat a wide range of infections, from pneumonia to urinary tract infections to certain sexually transmitted diseases. But what mattered most inside Pfizer was simpler: this was Pfizer’s first proprietary pharmaceutical product.

For the first time, Pfizer wasn’t just supplying ingredients that other companies turned into medicines. Pfizer owned the product, the brand, and the relationship with the doctor who would decide whether a patient ever received it.

Terramycin’s success proved Pfizer could play in the branded-drug business. It also exposed how unprepared the company was for it. Pfizer initially tried to sell the drug through its existing chemical distribution channels—and quickly learned that pharmaceuticals are sold in a different universe. Doctors had to be educated. Hospitals needed consistent supply. Regulators needed credible clinical data. Pfizer didn’t have that machine yet, so it built one.

The other defining move of this era wasn’t a molecule. It was a map.

The architect was John “Jack” Powers Jr., who would eventually become president. Powers saw what many American executives in the 1950s didn’t: pharma was inherently global, and the companies that showed up early would compound their advantages for decades. His logic was practical. Once you have a drug, getting it approved in a second country is often far easier than discovering it in the first place. But building the commercial infrastructure—relationships with doctors, hospitals, distributors, and regulators—takes years. If you wait, you’re always playing catch-up.

Powers didn’t believe in parachuting American products into foreign markets and assuming the world would adapt. He told international teams to “study the economy, establish proper contacts, learn language, history, and customs” before entering. And then he did the most important thing: he let local leaders run local businesses. They had real autonomy to make decisions fast, without waiting for permission from New York. In an era before email, before modern telecommunications, and before global coordination became cheap, that decentralization wasn’t just enlightened—it was how you won.

The model worked. While competitors tried to manage foreign operations from headquarters, Pfizer’s teams could respond in real time—adjusting pricing, distribution, and promotion to fit what was actually happening on the ground. The playbook scaled across wildly different environments: fast-growing Latin American markets, postwar Europe, and newly independent countries across Asia and Africa. By the mid-1960s, Pfizer was among the most international companies in the industry, with operations in dozens of countries and a meaningful share of revenue coming from outside the United States.

That footprint became part of Pfizer’s DNA. Decades later, roughly half of its revenue still comes from outside the U.S., and its global commercial infrastructure remains one of its most valuable advantages. The payoff in pharma is straightforward: patents are ticking clocks. The faster you can launch broadly after approval, the more of that limited window you can capture. And for smaller companies without that reach, partnering with Pfizer can be the difference between a good drug and a global drug.

At the same time, Pfizer leaned into the conglomerate instincts of the 1960s. Between 1961 and 1965, it spent $130 million in stock or cash to buy 14 companies, spanning vitamins, animal antibiotics, specialty chemicals, and even Coty cosmetics. Some of this had logic—especially in areas adjacent to Pfizer’s core, like animal health. Some of it was pure era-specific confidence: the belief that strong management could run anything.

The animal health bet, in particular, turned out to be a keeper. Pfizer established an animal health division in 1959, anchored by a 700-acre farm and research facility in Terre Haute, Indiana. It had the same attractive physics as human pharma: long development timelines, heavy regulation, and high barriers to entry. Over time it grew into a major business, eventually becoming Zoetis when Pfizer spun it off in 2013. Zoetis later reached a market capitalization above $70 billion—an outcome that underscored just how valuable that “adjacent” business had become.

Behind all of this—the product successes, the overseas expansion, the acquisition spree—Pfizer was building something even more consequential: a modern pharmaceutical research organization.

The company invested heavily in major research labs in Groton, Connecticut, which would grow into one of the largest pharmaceutical research campuses in the world. Pfizer recruited top scientists, built disciplined drug development processes, and expanded the clinical trial capabilities needed to run large studies across many sites and countries. This was the era when the Big Pharma model hardened into its recognizable form: huge R&D organizations, long time horizons, and the expectation that one blockbuster could pay for years of effort that went nowhere.

By the late 1970s, Pfizer was also learning the limits of its own diversification. Some of the 1960s acquisitions, especially Coty cosmetics, didn’t fit—and didn’t perform. Leadership began to internalize a lesson that would later become business-school orthodoxy: diversification for its own sake often destroys value, and management attention is the scarcest resource in a complex organization. The cleanup would take time, but the realization mattered. It nudged Pfizer toward a sharper focus on what it could do better than anyone else.

By 1980, the transformation was real. Pfizer had global reach, industrial-scale manufacturing, a sophisticated regulatory organization, and a growing research engine. It had become a diversified pharmaceutical company with the ability to discover, develop, and launch drugs worldwide.

Now it needed the products that would justify the machine it had built—the blockbuster era was about to begin.

The Blockbuster Era Begins (1980-1998)

The 1980s opened a new chapter for Pfizer, one defined by a simple, industry-changing idea: a single drug could be so widely prescribed that it paid for an entire research engine.

The conditions were lining up. Medicinal chemistry was getting better. Wealthy countries were getting older. Chronic disease was becoming the biggest market in medicine. And marketing rules—especially in the U.S.—were evolving in ways that made it possible for drug companies to build brands, not just sell compounds. Pfizer didn’t invent the blockbuster era, but it was early to understand what it would reward: scale, speed, and a salesforce that could make a good drug feel unavoidable.

Pfizer’s first proof point arrived in 1980 with Feldene, the arthritis drug piroxicam. On paper, the innovation wasn’t flashy. It was convenience. In a world where many arthritis patients were taking handfuls of pills across a day, Feldene was once daily. That small change mattered. Chronic pain isn’t managed in a laboratory; it’s managed in real life, where missed doses are common and relief is fragile. Feldene fit into people’s routines, and doctors noticed.

It became Pfizer’s first drug to cross the $1 billion threshold in annual revenue—an internal landmark that quietly rewired strategy. If you could do this once, you could build a company around doing it repeatedly. The math, of course, was brutal: spend huge sums on research, accept that most programs fail, and bet that a small number of winners will carry the entire portfolio. But Pfizer now had a winner. And it wanted more.

The next year brought Diflucan, or fluconazole—an oral treatment for serious fungal infections. Before Diflucan, many of these infections were treated with intravenous amphotericin B, a drug so harsh doctors nicknamed it “amphoterrible.” Diflucan didn’t just work; it changed where treatment could happen. A patient could take a pill at home instead of being tethered to an IV in a hospital.

That difference became life-and-death during the AIDS crisis. As immunocompromised patients became vulnerable to opportunistic infections like cryptococcal meningitis and esophageal candidiasis, Diflucan became a crucial tool. It also showcased something Pfizer was getting very good at: finding large patient populations stuck with bad options, then using its reach to make the better option the default.

Then came Zoloft. Approved in 1991, it entered a depression market that Prozac had already cracked open—and, in many ways, normalized. But competing in that category required more than a molecule. It required messaging that could meet patients where they were, and a commercial machine that could win mindshare with physicians and consumers at the same time.

Pfizer had that machine. Zoloft eventually became one of the company’s defining products, peaking at more than $3 billion in annual sales in 2005. And it turned Pfizer into something new: a consumer-facing brand. Zoloft ads became a staple of American television, including the famously simple “bouncing blob” character with a rain cloud overhead—an attempt to make depression feel understandable and treatment feel acceptable. It was direct-to-consumer pharma marketing at full power, and Pfizer was one of the best in the business at it.

Through the mid-1990s, Pfizer kept stacking wins. Aricept, co-developed with Japan’s Eisai, became a standard treatment for Alzheimer’s symptoms—even as debates continued about how much it truly moved the needle for patients. Alzheimer’s was, and still is, one of the hardest categories in medicine: enormous unmet need, messy measurement, and clinical trials that can produce frustratingly ambiguous outcomes. Aricept’s success underscored a reality of the blockbuster era: a drug didn’t have to be perfect to be massively adopted, especially when a company could educate physicians at scale and deliver globally.

Norvasc did something different. It was a hypertension drug that became one of the most widely prescribed blood pressure medications in the world. Doctors liked it. Patients tolerated it. And it fit into the daily rhythm of chronic care. Like Feldene, it reinforced a lesson Pfizer was internalizing as a commercial advantage: in real-world medicine, tolerability and once-daily convenience can matter as much as marginal differences in efficacy. A drug only works if people actually take it.

By the late 1990s, Pfizer had built what rivals feared: a broad blockbuster portfolio. That breadth mattered because pharma has a built-in doomsday clock—patent expiration. A single product can throw off billions, and then, almost overnight, generics can rip it apart. Pfizer was trying to avoid being a one-hit wonder by building multiple hits at once. By the end of the decade, it had a lineup of billion-dollar products that no competitor could match.

But two drugs came to define Pfizer’s image in this era: Viagra and Lipitor. And both would end up changing the company’s trajectory—one through cultural shockwave, the other through corporate warfare.

Viagra started as a disappointment. At Pfizer’s Sandwich research facility in Kent, England, scientists were developing sildenafil for angina, the chest pain caused by reduced blood flow to the heart. In trials, the cardiovascular effects were underwhelming. The program looked headed for the shelf.

Then the trial participants began reporting something else: improved erections. Many didn’t want to give their unused pills back. The clinical team, led by Dr. Ian Osterloh, saw what it meant immediately.

Pfizer made a decisive pivot. Instead of forcing sildenafil into a crowded cardiovascular market, it would aim directly at erectile dysfunction—an enormous condition that was rarely treated because it was too stigmatized to talk about. The existing options were invasive and unappealing: injections or vacuum devices. Pfizer realized that a simple pill wouldn’t just compete in a market. It would create one.

When Viagra launched in March 1998, demand detonated. Doctors wrote about 40,000 prescriptions in the first two weeks. It brought in $788 million in its first year and nearly $2 billion by its second. But the revenue was only part of the story. Viagra broke the cultural silence. Bob Dole went on television to talk about erectile dysfunction. Late-night comedy built an entire genre of jokes around a prescription drug. Pfizer had turned an awkward medical issue into mainstream conversation, and in doing so proved it could do something rare: unlock demand by changing behavior, not just offering a treatment.

Lipitor was the bigger prize.

Atorvastatin was developed inside Warner-Lambert’s Parke-Davis unit under Dr. Bruce Roth. Warner-Lambert faced a problem: the statin market was already crowded with Merck’s Zocor and Bristol-Myers Squibb’s Pravachol. Rather than fight alone, it signed a co-promotion deal with Pfizer—effectively renting Pfizer’s most powerful asset, the largest sales force in the industry, to help push Lipitor.

Lipitor launched in 1997 and started taking share fast. By the late 1990s it was clearly headed toward historic status, ultimately reaching peak annual sales above $12 billion. Pfizer’s sales force was the accelerant: large, disciplined, and deployed with relentless focus. And Lipitor gave them the perfect pitch—clinical data suggesting it could lower LDL cholesterol more effectively than its rivals.

But the deal structure mattered. Pfizer got a slice of the profits for doing the work, while Warner-Lambert kept ownership and the larger share of the economics. As Lipitor’s trajectory steepened quarter after quarter, that arrangement began to look less like a partnership and more like Pfizer doing the heavy lifting while someone else collected most of the upside.

Then there was the risk. The co-promotion agreement had termination provisions tied to a change of control at Warner-Lambert. If another company bought Warner-Lambert, Pfizer could lose access to the most important drug in its portfolio—right as it was becoming the most important drug in the industry.

So Lipitor became both a threat and a temptation: a franchise Pfizer couldn’t afford to lose, and one it increasingly didn’t want to share. The question inside Pfizer’s leadership sharpened into something almost inevitable.

Why split the future—when you could own it?

The Warner-Lambert Hostile Takeover (1999-2000)

The fight for Warner-Lambert was, at its core, a fight for Lipitor. By 1999, the cholesterol drug was doing roughly $5 billion a year, had about half the U.S. statin market, and was still growing fast. This wasn’t just a blockbuster. It was the blockbuster—already on a trajectory to become the most commercially successful drug the industry had ever seen. And Pfizer knew exactly what it had in its hands, because it had helped build Lipitor’s momentum through the co-promotion deal.

Then, in November 1999, the ground shifted. American Home Products and Warner-Lambert announced a friendly merger. On paper, it was two mid-tier pharma companies combining. In reality, it threatened Pfizer’s future. A change of control at Warner-Lambert could disrupt—or even end—Pfizer’s access to Lipitor. For Pfizer CEO William Steere, it wasn’t an abstract risk. Losing Lipitor would have punched a crater in Pfizer’s growth story and handed the most valuable drug franchise in the world to someone else.

So Pfizer did something that was still unusual in pharma: it went to war.

Within days, Pfizer filed a complaint to challenge the deal and launched its own hostile bid for Warner-Lambert at a higher value. The structure was a strategic flex—an all-stock offer that leaned on Pfizer’s larger market cap to outbid American Home Products without loading up on debt.

It was a gutsy move, and not just financially. Hostile takeovers were rare in a business built on long-term relationships—with physicians, regulators, academic researchers, and patients. A public brawl risked reputational damage and internal distraction. Warner-Lambert’s leadership painted Pfizer as a corporate raider and warned that a takeover would slash jobs, upend research, and harm the company’s pipeline.

What followed was a full-scale corporate campaign: boardrooms, courtrooms, and headlines. Warner-Lambert threw up every defense it could—legal maneuvers, shareholder outreach, conversations with alternative suitors, and intense behind-the-scenes lobbying. The message was consistent: the American Home Products deal was the better fit; Pfizer was acting out of desperation; and Warner-Lambert would be better off independent.

But Pfizer held two advantages that were hard to argue with. First, money: Pfizer’s bid was simply richer, and shareholders tend to vote with their wallets. Second, credibility: Pfizer already knew the Lipitor machine from the inside. To investors and analysts, that meant less execution risk on the one thing that mattered most.

As shareholder pressure mounted, Warner-Lambert’s options narrowed. In February 2000, the board gave in. Pfizer agreed to pay about $90 billion in stock, creating the world’s second-largest pharmaceutical company. The promised synergies were huge—Pfizer projected $1.6 billion in cost savings by eliminating duplicate functions, with a ramp that started quickly and hit full run-rate within a couple of years.

Then came the hard part: integrating two massive organizations. Jobs overlapped. Teams competed. Research programs were triaged—some got new resources, others were shut down. And there was a cultural clash baked into the deal: Pfizer’s aggressive, sales-driven identity colliding with Warner-Lambert’s more research-oriented posture. The friction showed up everywhere, from leadership meetings to lab benches.

Still, the logic that drove the acquisition remained simple and brutally compelling. Pfizer now owned Lipitor outright. And Lipitor kept climbing, eventually surpassing $12 billion in peak annual sales. The deal also delivered other assets—consumer health brands and additional pharma products—but the center of gravity was always Lipitor.

Just as importantly, the takeover revealed a new version of Pfizer’s playbook: use scale, financial firepower, and a world-class commercial engine to buy the franchises that could feed that engine—and then make them even bigger.

It also left behind a question that would follow Pfizer for decades: is Pfizer primarily a research company that uses deals opportunistically, or a deal machine that also does research?

The shockwaves went beyond Pfizer. The Warner-Lambert battle sent a message across the industry: if a company had an asset valuable enough, it could become a target—no matter how established it seemed. Defensive consolidation accelerated, and mega-mergers became a defining feature of Big Pharma in the years that followed.

For Pfizer shareholders, the verdict was ultimately delivered by Lipitor’s performance. Lipitor became the first drug to top $10 billion in a single year, and its lifetime revenue eventually exceeded $125 billion—more than enough to justify a $90 billion takeover. In the end, Pfizer didn’t just protect its access to Lipitor.

It bought the future outright.

The Pharmacia Mega-Merger and Peak Pharma (2003)

Three years after swallowing Warner-Lambert, Pfizer went back to the deal table—this time for Pharmacia. On April 16, 2003, the two companies began operating as one, creating what was then the world’s largest pharmaceutical company. The combined Pfizer suddenly had an R&D budget of $7.1 billion and a portfolio that touched almost every major therapeutic area. If Warner-Lambert made Pfizer huge, Pharmacia was meant to make it unassailable.

Part of what Pfizer was really buying was a matryoshka doll of other companies. Pharmacia itself had been assembled through prior mergers, and inside it sat Searle—the storied drugmaker that pioneered oral contraceptives in the 1960s—plus Searle’s biotech arm, SUGEN. And, crucially, Searle brought something Pfizer cared about immediately: Celebrex.

Celebrex was a COX-2 inhibitor, part of a new class of anti-inflammatory drugs promoted as a gentler alternative to traditional NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen. The promise was elegant: relief from pain and inflammation, with fewer gastrointestinal side effects like ulcers. Searle had co-developed Celebrex with Pfizer, and the Pharmacia merger pulled the whole franchise fully into Pfizer. At its peak, Celebrex would generate billions in annual revenue.

Then the category’s dream turned into a nightmare. In September 2004, Merck pulled Vioxx, a competing COX-2 drug, after evidence of increased risk of heart attacks and strokes. The Vioxx withdrawal was an industry-wide earthquake. Merck was hit with tens of thousands of lawsuits and ultimately settled for $4.85 billion. More damaging than the money was the broader consequence: once Vioxx collapsed, every COX-2 inhibitor—including Celebrex—fell under suspicion. Suddenly, a “breakthrough” class was being re-litigated in the court of public opinion, in doctors’ offices, and in regulators’ conference rooms.

Pfizer navigated that moment better than Merck did, helped by data suggesting Celebrex’s cardiovascular profile looked somewhat better in studies, and by steadier crisis management. But the bigger lesson didn’t depend on who handled the headlines better. Pharma’s margin between triumph and disaster can be terrifyingly thin. A single safety signal can vaporize years of revenue forecasts and put an acquisition thesis on trial overnight.

Financially, the merger reflected who was in charge. Pfizer shareholders owned 77% of the combined company; Pharmacia’s shareholders received 23%. Pfizer’s stock gained a modest 7% over the 245-day merger period—hardly a market celebration. The signal was clear: investors weren’t sure these ever-larger combinations were still creating value, or just creating size.

Because what the merger undeniably produced was scale—extraordinary, almost absurd scale. Pfizer now had leading positions across cardiovascular, central nervous system, inflammatory disease, infectious disease, and oncology. It had the biggest pharmaceutical sales force in the world, more than 100,000 employees. It had the biggest R&D budget. And it still had Lipitor, the best-selling drug on the planet. This was Peak Pfizer: the logical endpoint of “grow through acquisition.”

But the flaw in the logic was already visible. In pharma, size does not automatically produce innovation. A huge R&D budget can just as easily become a tax—spread across too many sites, too many therapeutic areas, and too many internal committees deciding what gets funded. Critics started saying Pfizer had become too big to invent: a place where unconventional ideas died slowly and safe, incremental programs crowded out the risky bets that create real breakthroughs. In the years ahead, that critique would look less like sniping and more like diagnosis.

The Pharmacia era also pushed Pfizer into a long overdue cleanup. It started shedding businesses that didn’t fit a more focused strategy. Adams—the confectionery unit behind Trident gum and Halls cough drops—was sold to Cadbury Schweppes. The company moved toward narrowing itself around human pharmaceuticals and animal health, unwinding pieces of the old conglomerate logic. It was Pfizer acknowledging, belatedly, what markets had learned again and again: focus tends to create value; diversification for its own sake often destroys it.

And even after all that scale, all that “portfolio,” and all those deals, the uncomfortable truth remained: Pfizer was still anchored to a handful of blockbusters. The science is glamorous, but the business model is unforgiving. Every drug comes with an expiration date, and when patents end, the economics can collapse fast. The only real defense is to keep finding or buying new winners faster than the old ones fall off the cliff.

Pfizer had built the biggest machine in pharma. Now it had to prove the machine could keep feeding itself—because the treadmill was about to speed up.

The Patent Cliff and Reinvention (2009-2019)

From 2009 to 2019, Pfizer ran straight into the defining fear of modern pharma: the patent cliff. The company had built an empire on blockbuster drugs with ticking clocks. Now those clocks were about to hit zero. What followed was a decade of enormous bets, painful cuts, and strategic reshaping—Pfizer trying to rebuild itself before its biggest money-makers evaporated.

The decade opened with Pfizer’s largest acquisition ever. On October 15, 2009, it completed the purchase of rival Wyeth for $68 billion in cash and stock, making Pfizer the largest pharmaceutical company in the world by revenue. This wasn’t another Warner-Lambert or Pharmacia—buying a pile of small-molecule pills and a sales force. Wyeth brought something different: biologics and, especially, vaccines.

Wyeth’s crown jewel was Prevnar 13, a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine that protected against thirteen strains of bacteria that can cause pneumonia, meningitis, and bloodstream infections. Prevnar 13 went on to become one of the world’s best-selling vaccines, generating billions in annual revenue and proving something Big Pharma had historically undervalued: vaccines could be not just impactful, but massively commercial.

Wyeth also brought capabilities Pfizer needed for the next era: biologic manufacturing. Small-molecule drugs like Lipitor are chemical compounds that can be precisely replicated. When patents expire, generic manufacturers can produce identical copies and price collapses.

Biologics play by different rules. They’re large, complex proteins grown in living cells. The manufacturing is so delicate that small process changes can alter the final product. Competitors don’t make perfect copies; they make “biosimilars,” and getting those approved is typically harder than launching a traditional generic. Strategically, that meant something very simple: a portfolio with more biologics and vaccines is harder to attack when exclusivity ends.

Pfizer’s leadership—first under Jeff Kindler and then under Ian Read—was signaling that the future couldn’t be built on easily copied pills alone. But the crisis the company feared most was still coming.

It arrived on schedule in November 2011, when Lipitor’s U.S. patent expired. For years, Lipitor had been the industry’s undisputed champion, generating more than $12 billion at its peak and throwing off an outsize share of Pfizer’s profits. Analysts had been counting down to the moment for a decade, yet the drop still landed like a shock.

Once generic atorvastatin hit the market at a fraction of the price, Lipitor’s revenue cratered. In the first full year after expiry, U.S. Lipitor sales fell by roughly 70%. This is the brutality of the patent cliff: not a slow decline, but a trap door.

Pfizer responded the way large companies often do when a core profit stream disappears: restructure, cut, and simplify. It eliminated thousands of jobs, closed research facilities, and took costs out of the system wherever it could. And it began to separate businesses that no longer fit the version of Pfizer it wanted to be.

The most prominent divestiture was the spinoff of its animal health business as Zoetis in 2013. It was a successful IPO, and Zoetis later grew into a standalone company with a market capitalization above $70 billion. But it was also a telling moment. Animal health had been a steady, reliable growth engine. Spinning it out was a tacit admission that Pfizer wanted focus—and needed flexibility—more than it wanted diversification.

Then came an even more deliberate piece of surgery. Pfizer combined its established brands and off-patent drugs with Mylan, a major generic manufacturer, to create Viatris. The logic was straightforward: Pfizer’s older products were increasingly commoditized, and a business built around generics and mature brands didn’t belong inside a company trying to convince investors it was an innovation-led growth story. The deal let Pfizer push slower-growth assets into a structure better suited to them, while it concentrated its own resources on areas like innovative medicines, vaccines, and oncology.

That Viatris spinoff ultimately completed in 2020, but the thinking belonged to the 2010s: Pfizer was no longer trying to be everything at once. Over the years, it had accumulated consumer health, animal health, generics, innovative pharma—an empire built through decades of dealmaking. Now it was shrinking itself on purpose, betting that a tighter company would perform better than a sprawling one.

Not every move was a divestiture. Pfizer also tried to buy its way out of the cliff with mega-deals, and two of the biggest failed in spectacular fashion.

In 2014, Pfizer made an unsolicited bid for AstraZeneca. Part of the structure was a tax inversion—moving Pfizer’s legal domicile to the U.K. to reduce its effective corporate tax rate. AstraZeneca rejected the offer, and the political backlash around inversion logic helped sink the attempt.

Two years later, Pfizer tried again, this time with a proposed $160 billion merger with Allergan, the Botox maker headquartered in Ireland. This deal was also designed as a tax inversion. But the U.S. Treasury Department issued new regulations aimed directly at stopping inversions, and Pfizer and Allergan abandoned the transaction.

Those failures exposed the tension of the era. Pfizer was still a cash-generating machine, but it was struggling to deploy that cash in ways big enough to replace aging blockbusters. The patent cliff wasn’t one event. It was a conveyor belt: every year, more revenue rolling toward expiration.

There was also a reputational low point that shaped how the public saw Pfizer heading into the next decade. In 2009, Pfizer paid $2.3 billion to resolve federal charges related to the illegal marketing of several drugs, including the painkiller Bextra. The settlement included a $1.195 billion criminal fine, the largest in U.S. history at the time. Federal allegations included promoting drugs for uses not approved by the FDA and paying kickbacks to healthcare professionals. The business kept moving, but the episode poured fuel on a skepticism about Big Pharma that would linger—and matter—when Pfizer would later need public trust most.

The decade’s final—and most consequential—move was leadership. On January 1, 2019, Albert Bourla became CEO, succeeding his mentor Ian Read. Bourla was a Greek-born veterinarian from Thessaloniki who had spent his entire career at Pfizer, rising through animal health and vaccines. He didn’t come from the traditional power centers of Big Pharma leadership: blockbuster sales or Wall Street dealmaking.

What he did bring was firsthand experience in biologics and vaccines, operational instincts sharpened in global and emerging-market roles, and a higher tolerance for decisive bets. At the time, it read like an internal promotion during a messy rebuild.

In hindsight, it was Pfizer unknowingly choosing the right CEO for the moment that was about to arrive—one that would rewrite the company’s reputation, its finances, and its place in history.

The COVID Vaccine Triumph and mRNA Revolution (2020-2023)

In January 2020, as reports of a new coronavirus began leaking out of Wuhan, most pharmaceutical executives reacted with caution. Vaccines usually take years—often a decade—to develop, and the odds are punishing. Historically, fewer than one in ten vaccine candidates that enter clinical trials ever make it to approval. The record for “fast” was still measured in years. Bringing a brand-new vaccine from concept to authorization in under twelve months wasn’t just unlikely; it was widely considered impossible.

Albert Bourla looked at the same situation and made a different bet. He’d been CEO for barely a year, still defining what his Pfizer would be. But he’d come up through vaccines and biologics. He knew the tools that existed, and he knew what was at stake. If Pfizer could move fast enough, it wouldn’t only help save lives—it could reset the company’s reputation, its financial future, and its strategic freedom for a generation.

So in late January, Bourla called Ugur Sahin, the Turkish-German physician and scientist who had co-founded BioNTech with his wife, Ozlem Tureci. BioNTech was a small biotech in Mainz, Germany, founded in 2008 around an ambitious idea: using messenger RNA technology to train the immune system, initially for cancer. It had no marketed products. It had never run a Phase 3 trial. It lived on collaboration revenue. What it did have was a platform that, in theory, could be repurposed against a new pathogen at breathtaking speed.

mRNA is, at its simplest, a set of genetic instructions. In human biology, it’s the courier between DNA and the cellular machinery that builds proteins. BioNTech’s approach was to synthesize mRNA that encodes a specific protein—in this case, the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2—inject it, and let the body’s own cells manufacture the target. The immune system learns the shape of that protein, mounts a response, and remembers it. When the real virus shows up, the immune system is already trained.

The appeal wasn’t just elegance. It was velocity. Once scientists had the genetic sequence of a virus, an mRNA candidate could be designed in days and pushed toward manufacturing in weeks. Traditional approaches—growing weakened or inactivated virus—move on a very different clock.

When Pfizer and BioNTech announced their partnership in March 2020, it was a classic “two halves make a whole” deal. BioNTech brought the mRNA science and the ability to rapidly design candidates. Pfizer brought the heavy machinery: global regulatory expertise, the operational capability to run a 44,000-person Phase 3 trial across 150 sites in six countries, manufacturing scale measured in billions of doses, and a distribution network built to reach the world.

Then Bourla made a decision that shaped everything that followed. Pfizer would not take Operation Warp Speed funding for development and manufacturing. It would accept only a U.S. government advance purchase agreement—$1.95 billion for 100 million doses, contingent on authorization.

The logic was speed. Government money came with government oversight, reporting requirements, and layers of process. In normal times, that can be sensible. In a pandemic, every additional gate can cost weeks, and weeks cost lives. Pfizer would finance the work itself—about $2 billion invested “at risk”—and run the program at full throttle. If it failed, Pfizer would eat the loss. If it worked, Pfizer wouldn’t just be early. It would be first.

The choice was controversial. Critics argued that refusing funding reduced transparency and amplified fears of profiteering. Others worried that public trust demanded more government involvement. But on timing, it worked: the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine became the first to receive emergency use authorization in the United States and in many other countries, beating Moderna’s government-funded vaccine by about a week.

What happened next still reads like science fiction.

Pfizer and BioNTech went from sequence to emergency authorization in under eleven months. They enrolled 44,000 participants into a Phase 3 trial—an enormous global undertaking—on a timeline normally reserved for much smaller studies. On November 9, 2020, they announced the first major readout: 95% efficacy against symptomatic COVID-19. The result was so strong it surprised even many optimists.

The FDA granted emergency use authorization on December 11, 2020. Three days later, Sandra Lindsay, an intensive care nurse in New York, became the first American vaccinated outside a clinical trial.

The science was extraordinary. The manufacturing might have been even harder.

No one had ever produced an mRNA vaccine at this scale. It required dozens of tightly controlled steps: synthesizing mRNA from a DNA template, packaging that fragile molecule inside lipid nanoparticles so it could survive and enter cells, filling and sealing vials, and then moving everything through a supply chain that had to stay ultra-cold—around minus 70 degrees Celsius. Pfizer expanded and repurposed major sites, including Kalamazoo, Michigan and Puurs, Belgium, and built a global system that could ultimately produce around four billion doses per year. To ship it, Pfizer designed specialized containers packed with dry ice and tracked by GPS, able to hold temperature for up to ten days.

It was industrial mobilization that echoed Pfizer’s penicillin sprint in World War II: a company turning process engineering into a life-saving weapon, under impossible time pressure.

The financial impact was just as historic. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, Comirnaty, generated $36.8 billion in revenue in 2021 and about $37 billion in 2022—more in a single year than Lipitor, previously the best-selling drug in history, ever produced at its peak. Pfizer also brought Paxlovid to market, an oral antiviral that inhibits a key enzyme the virus needs to replicate. In 2022, the vaccine plus Paxlovid pushed Pfizer’s COVID-related revenue above $56 billion, and total company revenue peaked near $100 billion—more than double what Pfizer had done pre-pandemic.

Just as important, the moment rewrote the narrative around the company. Pfizer had spent years being treated by many investors as a mature, slow-growth pharma giant living in the shadow of expired patents. Now it was the most visible healthcare company on Earth. Bourla became one of the world’s most recognizable CEOs, and Pfizer’s stock climbed above $59 in late 2021.

But the same surge that made Pfizer look unstoppable also created a new vulnerability: a mountain of revenue tied to a once-in-a-century emergency.

As the acute phase of the pandemic faded, vaccination rates plateaued, booster demand dropped, and governments cut or canceled orders. Pfizer’s COVID revenue fell sharply in 2023 and continued declining through 2024 and 2025. COVID-related sales fell from an estimated $11 billion in 2024 to roughly $6.5 billion in 2025, with another $1.5 billion decline expected in 2026. Investors reset expectations just as quickly as they’d raised them. After peaking above $59 in late 2021, the stock fell below $26 by early 2024.

The operational downside of pandemic-scale production hit, too. Pfizer wrote off billions in excess vaccine and antiviral inventory as demand collapsed, including a $5.6 billion charge tied to Paxlovid inventory. It was the brutal math of crisis manufacturing: produce too little and you fail the world; produce too much and you absorb the financial whiplash when the emergency ends.

And as COVID receded, the old questions came roaring back, louder than ever. Without COVID, was Pfizer actually growing? Would the company reinvest its windfall into the next generation of breakthroughs—or spend it chasing deals at inflated prices? Had the pandemic simply postponed another patent-cliff-style reckoning?

Then there was the social backlash. Anti-vaccine sentiment intensified in parts of the population, fueled by misinformation and political polarization. Pfizer, as the most visible vaccine maker, became a lightning rod. Bourla received death threats. The company that had helped deliver the fastest vaccine response in history found itself at the center of conspiracy theories and political attacks.

Pfizer had just lived through its greatest modern triumph. The question now was whether it could convert that triumph into a durable new era—or whether COVID would prove to be a brilliant, singular peak followed by a long slide back to the treadmill.

The Seagen Acquisition and Cancer Moonshot (2023-Present)

Albert Bourla’s answer to the post-COVID hangover was to place another big, concentrated bet. In March 2023, Pfizer announced a $43 billion agreement to acquire Seagen, the Seattle biotech best known for pioneering antibody-drug conjugates. The deal closed in December 2023. It was the biggest biopharma acquisition since AbbVie bought Allergan in 2019, and it signaled a clear strategic pivot: Pfizer was going to try to make oncology the next engine that could carry the company.

To understand why Pfizer paid up for Seagen, you have to understand what ADCs are—and why they’re such a big deal in modern cancer care.

An antibody-drug conjugate is built from three parts: an antibody that recognizes a specific protein on the surface of a cancer cell, a powerful chemotherapy agent (the “payload”), and a chemical linker connecting them. The antibody works like a homing device. It circulates until it finds cells displaying the target, binds, gets pulled inside, and then releases the payload right where it can do the most damage. Conceptually, it’s the difference between blasting the whole body with chemo and delivering a highly targeted hit to tumor cells. The promise is brutal efficiency: use an incredibly potent drug, but concentrate it where it’s needed most.

Seagen—founded as Seattle Genetics in 1998 by Clay Siegall—had spent more than two decades pushing that platform from theory into real medicines. Like many biotechs, it lived through a long stretch of patient, expensive development with no approved products for years, funded by venture capital and partnerships. Its first breakthrough, Adcetris, was approved in 2011 for Hodgkin lymphoma and became a major treatment in blood cancers. Thirteen years from founding to first product is a reminder of the clock biotech investors sign up for—and the persistence required to win.

After Adcetris, Seagen built a broader portfolio: Padcev for bladder cancer, Tivdak for cervical cancer, and Tukysa for breast cancer. Each one helped prove ADCs weren’t a one-shot trick. Different targets, different payloads, different tumor types—still the same underlying platform. Together, they made Seagen the leading ADC-focused biotech and one of the most credible owners of this technology in the world.

Still, the deal came with baggage. Siegall had left Seagen in 2022 amid domestic violence allegations, creating reputational risk. And Pfizer’s $229 per share offer represented a meaningful premium, prompting the obvious question: was Pfizer overpaying in a rush to put COVID cash to work? But the strategic logic was hard to miss. Pfizer needed a new growth platform, and ADCs were—and still are—one of the most promising frontiers in oncology.

What Pfizer really bought was two things at once: four marketed cancer drugs that could generate revenue immediately, and a platform that could spawn new therapies for years. Overnight, Pfizer’s oncology pipeline roughly doubled to 60 programs across modalities—ADCs, small molecules, bispecific antibodies, and other immunotherapies.

The organizational response was just as decisive. Pfizer created a dedicated Oncology Division, led by Dr. Chris Boshoff as Chief Oncology Officer, bringing together oncology R&D and commercial operations across the combined company. Boshoff laid out an aggressive goal: shift Pfizer’s oncology portfolio from 6% biologics to 65% biologics by 2030. If that happens, it would change the business profile of Pfizer’s cancer franchise—away from small-molecule drugs that can be copied more easily, and toward complex biologics that are tougher to replicate.

Early signs from the integration have looked solid. Seagen’s products contributed about $3.1 billion in revenue in 2024, coming in ahead of initial expectations. Padcev, in combination with Merck’s Keytruda, has become a new standard of care in first-line bladder cancer, and Pfizer has described its potential in “mega-blockbuster” terms. In January 2026, Pfizer also reported positive results from the BREAKWATER trial of Braftovi in combination with cetuximab and chemotherapy for colorectal cancer, with an objective response rate of 64.4% versus 39.2%, data presented at the 2026 ASCO GI Cancers Symposium.

Of course, oncology is the most competitive arena in Big Pharma. Merck’s Keytruda is still the category-defining giant, with annual sales above $25 billion and an ever-expanding set of indications. Roche remains a deep, formidable competitor. AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and AstraZeneca all have major oncology positions. And the ADC race is getting crowded fast: Daiichi Sankyo’s Enhertu, partnered with AstraZeneca, has become one of the most successful ADC launches ever, while Chinese biotech companies like RemeGen are developing their own ADC platforms with lower cost structures.

Pfizer’s edge is what it has always been when it’s at its best: scale, execution, and the ability to industrialize complex science. Few companies can run global oncology trials across dozens of countries at once, navigate parallel regulatory pathways, and then launch worldwide at speed. And Seagen brought the specialized know-how—the chemistry, biology, and manufacturing experience behind ADC design—that’s difficult to copy and takes years to build.

The open question is the same one Pfizer has faced after almost every reinvention: can a huge organization turn a platform into a steady stream of breakthroughs, or does size become drag? In oncology, scale is unusually valuable. Phase 3 cancer trials can be enormous and expensive, and commercialization is unusually complex—oncologists need education, hospitals need protocols, and reimbursement can make or break uptake. Those are places where Pfizer’s footprint can be advantage, not overhead.

Pfizer has projected that Seagen’s products could generate more than $10 billion in annual revenue by 2030, and that the combined oncology pipeline could deliver at least eight blockbuster medicines by the end of the decade. Whether it can hit those targets while navigating upcoming patent pressures on drugs like Xeljanz, Eliquis, and Ibrance is likely to define the next five years. Oncology already makes up about 28% of Pfizer’s sales, growing around 7%, and it’s increasingly the center of gravity for the whole company.

Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

Pfizer’s 175-year history isn’t just a timeline of products and mergers. It’s a playbook for how a giant company survives, grows, and occasionally trips over its own size.

The biggest lesson is the power of platform technologies—capabilities that can be reused again and again in new ways. Pfizer’s investment in fermentation in the 1880s didn’t just unlock citric acid. It led to vitamin C, then made deep-tank penicillin possible, and—much later—helped build the manufacturing mindset and infrastructure that could scale a COVID vaccine to billions of doses. Each chapter made the next chapter easier. It’s compound interest, but applied to industrial know-how. The Seagen deal is the same pattern in a modern form: antibody-drug conjugates aren’t one product, they’re a platform that can generate many products over time.

The second lesson is that M&A isn’t something Pfizer dabbles in. It’s a core muscle. Warner-Lambert, Pharmacia, Wyeth, Hospira, Seagen—these weren’t “nice-to-have” deals; they were identity-shaping. The pattern tends to repeat: find a product or technology that can ride Pfizer’s global development and commercial machine, pay up to secure it, then integrate hard and pull out costs. Pfizer’s recent $7.2 billion cost-savings program shows how central that integration discipline is to the strategy. But there’s a tradeoff. Pfizer has sometimes overpaid, and the constant churn of acquisitions, reorganizations, and site changes can create exactly the kind of internal instability that makes great research harder.

That leads to the third lesson: the R&D productivity paradox. Pfizer has routinely been one of the industry’s biggest R&D spenders, yet many of its most important growth engines came from outside its own labs. Lipitor was developed at Warner-Lambert. Comirnaty came through a partnership with BioNTech. This doesn’t mean Pfizer can’t innovate—it can—but it raises a sharp question about Big Pharma: does massive scale help discovery, or smother it? The more consistent answer in Pfizer’s story is that scale is a superpower in clinical development, regulatory navigation, manufacturing, and commercialization—but not always in early-stage breakthrough invention, where speed and risk-taking matter more than process.

The fourth lesson is Pfizer’s most distinctive pattern: crisis as catalyst. The Civil War helped Pfizer scale. World War I forced a reinvention in citric acid production. World War II created the penicillin moment. COVID turned Pfizer into a central character in global history. Over and over, the company levels up when time is short and the stakes are high. That’s both a compliment and a warning: Pfizer can look ordinary in calm periods, then extraordinary when the world is on fire.

The BioNTech partnership points to a final lesson: when to partner versus when to acquire. Pfizer didn’t buy BioNTech. It paired BioNTech’s mRNA science with Pfizer’s operational engine and let BioNTech keep its independence. The result was speed—unprecedented speed. Against that, Pfizer’s history is full of acquisitions designed to bring science in-house. The contrast suggests a useful rule: when the science is truly cutting-edge and still evolving, partnership can outperform ownership.

There’s also a myth worth adjusting, not repeating: the idea that Pfizer is “a marketing company, not a science company.” Reality is messier. Pfizer’s researchers discovered Viagra (sildenafil), Zoloft (sertraline), Norvasc (amlodipine), and Diflucan (fluconazole), among others—real scientific wins that reshaped major markets. At the same time, its two most commercially important modern franchises, Lipitor and Comirnaty, originated outside the company. The more accurate takeaway is that Pfizer can do both internal discovery and external sourcing, but its clearest, most durable competitive advantage is what happens after discovery: clinical development, regulatory execution, manufacturing at scale, and global commercialization.

That global scale advantage is easy to underestimate if you haven’t lived inside regulated markets. A U.S. approval doesn’t unlock Europe, Japan, or China. Each requires separate data packages, separate filings, and separate negotiations with regulators. For smaller companies, that’s a bottleneck measured in years. Pfizer has the infrastructure—relationships, expertise, and teams across major agencies—to run parallel pathways and launch in multiple markets close together. In a business where patents are ticking clocks, that ability to compress time is money.

Finally, Pfizer’s history shows the blockbuster model’s brilliance—and its danger. When it works, it funds everything. Lipitor threw off enough profit to pay for enormous R&D budgets, cover failures, and underwrite acquisitions. But it also creates a structural vulnerability: concentration. When a single drug becomes too large a share of revenue, patent expiration becomes an existential event. One way to read Pfizer’s decades of dealmaking is as a constant attempt to outrun that trap—replenishing the next wave of blockbusters through acquisition and partnership, not just through the lab.

Analysis: Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

Pfizer has real strengths that the market may be discounting too harshly. It’s positioned squarely in two of the most attractive growth arenas in global healthcare: oncology and vaccines. The Seagen acquisition didn’t just add products; it expanded Pfizer’s opportunity set by bringing in a deep antibody-drug conjugate platform and roughly doubling the oncology pipeline. Early commercial performance has been encouraging. And if even a portion of those roughly 60 oncology programs hit, the payoff could be meaningful. The pipeline also includes candidates Pfizer hopes can compete in indications where Merck’s Keytruda—the category-defining giant—still sets the bar.

Even after the COVID surge faded, Pfizer came out of the pandemic with something most companies never get: strategic breathing room. It has the capital to invest, to absorb near-term volatility, and to take swings that might be out of reach for peers with tighter balance sheets. On top of that, Pfizer’s $7.2 billion cost-savings program creates another lever: protect margins while the company rebuilds its growth engine.

Pfizer is also trying to buy into the next mega-market. Its move into GLP-1 obesity treatments through Metsera and YaoPharma is late, but the market is enormous—Bourla has estimated it could reach $150 billion by 2030. In a category that big, being late doesn’t necessarily mean being irrelevant, especially if Pfizer can pair a viable product with its global development and commercialization machine.

Then there’s the core Pfizer competency that tends to get underestimated until it matters: integration. Warner-Lambert, Pharmacia, Wyeth, and now Seagen all tested Pfizer’s ability to digest big acquisitions and turn them into operating businesses. Over time, Pfizer has generally delivered the cost synergies it promised and expanded its commercial footprint in the process. Seagen, in particular, has been folded in quickly, with the new Oncology Division already operating as a unified organization. And while the “Pfizer overpaid” critique is often fair in the moment, history shows that the true scorecard in pharma is the full product lifecycle, not the first year after a deal closes.

Finally, Pfizer’s global footprint remains a quiet advantage. It operates in more than 175 countries, giving it distribution and regulatory muscle that’s incredibly hard to replicate. As healthcare spending rises in developing markets, Pfizer can often capture growth using infrastructure it already has, rather than building from scratch.

Put that all together with a valuation that implies little optimism—around 8 times forward earnings, nearly a 7% dividend yield, and a dividend paid for 349 consecutive quarters—and the bull case becomes straightforward: Pfizer doesn’t need perfection. It needs a few big programs to land, and it needs the patent cliff to be survivable. If that happens, today’s expectations may be too low.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with the same brutal reality that has haunted Pfizer before: the patent cliff is not a one-time event, it’s a schedule. Xeljanz faces key expirations in 2026. Eliquis and Ibrance follow. These are major products, and replacing that revenue is the central operational challenge of the next few years. Even Pfizer’s own 2026 guidance—$59.5 billion to $62.5 billion, essentially flat versus 2025—signals how hard it is to grow while absorbing expirations, even with aggressive cost cutting.

COVID is no longer a tailwind; it’s a shrinking line item. And while Seagen strengthens oncology, the $43 billion price tag added meaningful debt at a time when interest rates are higher. Meanwhile, competition in oncology is relentless. The ADC field, in particular, is getting crowded quickly, not only from established global players but also from increasingly capable Chinese biotech companies, many with lower cost structures and faster iteration cycles.

Pfizer’s obesity ambitions also come with a timing problem. After discontinuing its earlier GLP-1 candidate danuglipron in April 2025, Pfizer is trying again—but it’s chasing leaders. Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly have multi-year head starts and entrenched market positions.

Policy risk adds another layer of pressure. Pfizer raised prices on roughly 80 products entering 2026—more than any other pharmaceutical company—which drew political scrutiny in a climate where drug pricing is still a live wire. The Inflation Reduction Act’s Medicare drug price negotiation provisions also loom as a structural headwind, limiting pricing power in a way that simply didn’t exist in the Lipitor era.

Underneath all of this sits the most uncomfortable bear argument: R&D productivity. Pfizer spends well over $10 billion a year on research and development, but in recent years its biggest growth drivers have often come from outside its own labs. That approach can work—Pfizer is excellent at late-stage development and commercialization—but it gets more expensive as competition for biotech assets intensifies. Pfizer paid $43 billion for Seagen and up to $10 billion for Metsera. There’s a point where externally sourced innovation can become a treadmill of its own: necessary to stay in the game, but increasingly costly relative to the returns.

And then there’s the dividend. Nearly 7% is attractive, but it’s also a constraint. Pfizer pays roughly $9.8 billion a year in dividends. Combined with debt service after Seagen, that becomes a large fixed obligation—money that can’t be redirected to R&D, internal reinvestment, or the next acquisition without increasing leverage.

Structural Analysis

Zooming out, the industry structure is a mixed bag for Pfizer. Barriers to entry remain extremely high—regulation, development costs, and manufacturing complexity keep most would-be entrants out. But buyer power is rising, as governments and insurers negotiate more aggressively. Rivalry is intense among Merck, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, and AbbVie. And the threat of substitution from biosimilars and generics grows as more major drugs lose exclusivity.

Through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, Pfizer’s durable advantages are scale economies in manufacturing and distribution, and process power built from decades of regulatory and clinical development execution. Its vulnerability shows up in “cornered resource”: many of the most valuable modern franchises in Pfizer’s orbit originated externally, which reinforces the view that Pfizer excels most at scaling, de-risking, and commercializing discovery rather than consistently producing it. Counter-positioning risk is real, too—smaller, nimbler biotechs may be better suited to breakthroughs in newer modalities like cell therapy, gene editing, and AI-designed molecules.

Stacking Pfizer against peers sharpens the tradeoffs. Merck has Keytruda generating over $25 billion annually, giving it a dominant oncology engine but also concentration risk. Johnson & Johnson has diversification through MedTech that Pfizer lacks. AbbVie has already demonstrated a playbook for surviving a major cliff by replacing Humira with newer immunology drugs like Skyrizi and Rinvoq. Roche benefits from diagnostics cash flows that help fund pharma R&D. Pfizer’s mix—global scale, broad pipeline, and a depressed valuation—stands out, but so do its near-term pressures.

All of this leads to a bigger question about what Big Pharma is becoming. Are companies like Pfizer still the best engines of pharmaceutical innovation? Or are they increasingly the industrial and commercial layer—the global development, manufacturing, and distribution machine that monetizes discoveries made upstream at biotechs and universities? If the second view is right, a lower valuation multiple may be justified. If the first view is right—if scale and integration truly improve outcomes—then Pfizer’s current discount could be an opportunity. Reality likely sits between the extremes, which is exactly where market disagreements tend to live.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

Two metrics matter most.

First: non-COVID operational revenue growth. This strips out the volatility of pandemic products and highlights whether the underlying business is actually expanding. Pfizer has targeted roughly 4% operational growth in 2026 on this basis. If it can sustain that pace, the rebuilding thesis holds. If growth settles in the low single digits, it suggests the patent cliff is winning. If it turns negative, the bear case is playing out.

Second: oncology revenue as a share of total sales, currently around 28% and rising. This is the simplest scoreboard for the Seagen bet and Pfizer’s pivot toward cancer. If oncology climbs meaningfully over time—toward 40% or more by 2030—it would signal that Pfizer has successfully reset its center of gravity. If it stalls, it raises the risk that Seagen was more expensive patch than platform.

A useful third metric is late-stage pipeline momentum: how many assets advance through Phase 3 toward regulatory filing. Pfizer has said it plans to initiate a significant number of Phase 3 studies in 2026. Ultimately, the conversion rate from Phase 3 to approval—and then the launch trajectory of new products—will determine whether Pfizer can replace the revenue that falls away as exclusivities expire. In a company built on ticking clocks, the pipeline isn’t an abstract concept.

It’s the future.

Epilogue: The Next Reinvention

Pfizer’s history moves in cycles. A crisis hits, the company reinvents itself, a stretch of growth follows—and then the next shock arrives and forces the next transformation. The current cycle is easy to see: COVID created a once-in-a-century windfall, that windfall is now fading, and Pfizer is trying to replace it with something that can last. So far, that “something” is oncology. The next candidate is obesity.

If oncology has been the defining market of modern pharma, obesity could become the defining market of the next era. GLP-1 drugs—originally developed for diabetes—proved remarkably effective for weight loss and rapidly changed how the medical profession thinks about obesity treatment. Novo Nordisk’s Ozempic and Wegovy, and Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro and Zepbound, have produced tens of billions in revenue and turned a long-neglected condition into one of the most commercially important categories in healthcare. Bourla has estimated the total market could reach $150 billion a year by 2030—big enough to reshape the industry’s center of gravity.

Pfizer’s route into that market has been rough. Its earlier oral GLP-1 candidate, danuglipron, was discontinued in April 2025 after disappointing clinical results—a painful setback that cost time and momentum. Pfizer regrouped by acquiring Metsera for up to $10 billion and signing a collaboration with China’s YaoPharma worth up to $2.1 billion. The strategic idea is clear: give Pfizer multiple shots on goal, including oral formulations that could stand out in a market still dominated by injections. Metsera alone has said it plans to launch up to 10 Phase 3 trials in obesity.

But the gap is real. Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly have multi-year head starts not only in clinical development, but also in the specialized manufacturing capacity needed to produce GLP-1 drugs at scale. In this category, the bottleneck isn’t just a good molecule. It’s supply chains, factories, and execution—areas where Pfizer is strong, but where incumbents are already deep into the buildout.

Beyond obesity, Pfizer is also staring at a longer horizon: gene therapy, CRISPR-based treatments, and AI-driven drug discovery. These are the kinds of shifts that could change what Pfizer’s pipeline looks like ten years from now, not next quarter. The company has tied part of its cost-savings effort to modernization, with about $500 million earmarked for digital enablement and automation aimed at improving R&D productivity.

AI is the most tantalizing of these bets, because it targets the industry’s most stubborn problem: R&D is slow, expensive, and full of failure. The traditional process often takes a decade or more and consumes billions of dollars per successful drug, and roughly 90% of drugs that enter clinical trials never reach approval. If AI can improve success rates or shorten timelines—even modestly—the economic impact would be enormous.

Pfizer has been investing in machine learning tools for molecular design, using AI to help predict which candidates are more likely to succeed and to identify patient populations most likely to benefit. It has also deployed AI in manufacturing, using predictive algorithms to optimize production processes and reduce waste. In theory, Pfizer has an advantage here: size creates data. Decades of clinical trial records and real-world evidence from millions of patients are powerful raw material.

In practice, that advantage isn’t automatic. Large organizations can struggle to adopt new tools as quickly as startups, and pharma has a long history of big “technology transformations” that sounded revolutionary and delivered incremental change. Whether Pfizer can turn AI into a meaningful edge is still unanswered.

Hovering over all of this is a perennial corporate question: should Pfizer break itself up? The argument for a split is that oncology, vaccines, and the legacy pharmaceutical portfolio might each earn higher valuations as independent companies, eliminating a conglomerate discount that some believe weighs on the stock. The argument against is that Pfizer’s scale—especially in manufacturing and global distribution—creates advantages that would be hard to replicate in smaller, separated entities, and that the ability to allocate capital across multiple therapeutic areas gives Pfizer flexibility that pure-play rivals don’t have.

What’s not in dispute is the pattern. Pfizer has reinvented itself before: from chemicals to antibiotics, from antibiotics to blockbuster pills, from pills to vaccines. Each transition looked improbable in the moment and obvious in hindsight. The current pivot toward oncology—and the attempt to re-enter the obesity race—fits the same rhythm.