Penguin Solutions: From Linux Workstations to AI Infrastructure Powerhouse

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: January 2022. Meta announces what it says will become the world’s fastest AI supercomputer: the AI Research SuperCluster. The headlines are full of Meta’s metaverse ambitions and NVIDIA’s GPUs. But tucked into Meta’s own technical write-up is a name almost nobody outside infrastructure circles recognizes: Penguin Computing.

Meta credited “Penguin Computing, an SGH company” as its architecture and managed services partner—working with Meta’s operations team on hardware integration, helping deploy the cluster, and setting up major parts of the control plane. And this wasn’t a one-off cameo. Meta and Penguin had been working together since 2017, when Meta began building out its first serious AI infrastructure efforts.

So how did a San Francisco Linux server company—founded in 1998 by a 25-year-old open-source believer—end up playing a behind-the-scenes role in one of the most important AI systems on the planet?

Here’s the twist: today’s Penguin Solutions (Nasdaq: PENG) didn’t start as Penguin Computing. It began in 1988 as a specialty memory company. Over decades—and through strategic acquisitions—it evolved into what it is now. The defining moment came in 2018, when that memory-focused business acquired Penguin Computing: a pioneer in custom, high-performance, turnkey Linux clusters and cluster management software, and an early commercializer of the NASA-developed Beowulf approach to cluster computing.

That deal didn’t just add a product line. It rewired the company’s identity—from memory to infrastructure, from components to full systems, from obscurity to the center of AI’s “picks-and-shovels” economy.

This is a story about survival and timing. About a company that spent years building hard, unglamorous expertise in high-performance Linux clustering—only to discover that this exact skill set was suddenly in demand when AI training exploded. Today, Penguin says it has more than 75,000 GPUs under management, putting it among the largest operators in the world.

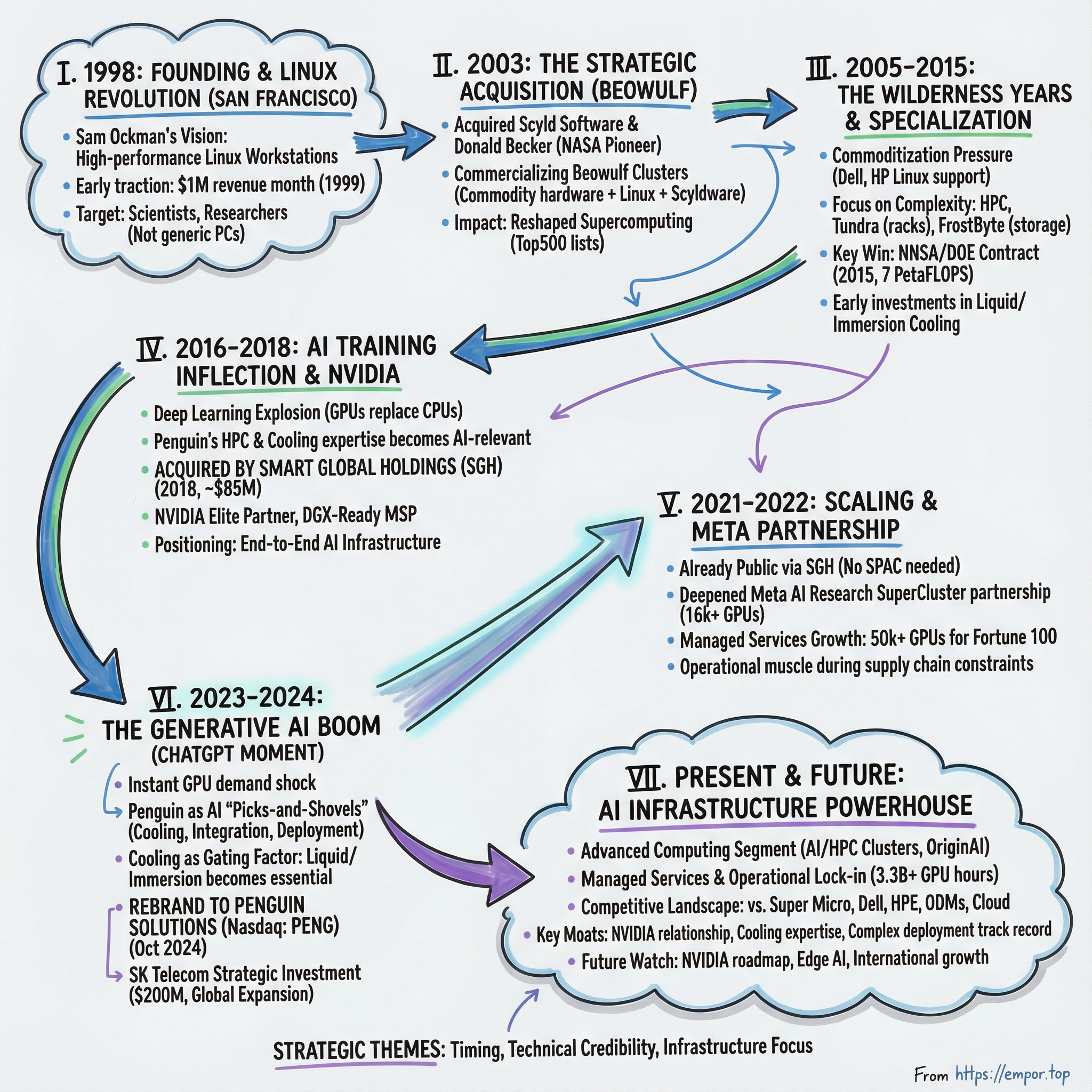

We’ll follow the journey in a few acts: the Linux revolution of the late 1990s, the long wilderness of server commoditization, the inflection point when AI training became the new HPC, and then the generative-AI gold rush that turned GPUs into the most fought-over resource in computing.

Along the way, we’ll look at the decisions—some inspired, some imperfect—that positioned Penguin to catch one of the biggest waves in technology history.

For investors, the themes are simple: timing, technical credibility, and the underrated power of being the infrastructure provider when everyone else is chasing gold. Let’s begin.

II. Founding Context & Early Years: The Linux Revolution (1998-2005)

San Francisco, 1998. The dot-com boom is heating up. Linux is starting to graduate from “tinkerer’s toy” to something you can actually run serious workloads on. And a young computer systems engineering student named Sam Ockman sees the gap: plenty of people are selling computers, but almost nobody is building great systems for the people who want Linux to be the center of their world.

Ockman wasn’t just adjacent to the open-source scene—he helped define it. While still a student, he was among the early pioneers of the movement. He was even one of the five people who coined the term “open source.” That matters, because Penguin wasn’t founded as a cynical “Linux is trendy” hardware shop. It came from someone who believed, technically and philosophically, that open software was going to change computing.

His origin story fits the mold. He got his first computer, an IBM PC, when he was seven. He grew up as the kind of person who didn’t just use machines—he took them apart, understood them, and rebuilt them better.

By 1999, Penguin was already showing traction. In May, Ockman—then 25—said the company cleared $1 million in revenue that month. For a startup that was barely a year old, that was real momentum.

The premise was straightforward and, at the time, contrarian: build high-performance Linux workstations and clusters when the mainstream market still revolved around Windows PCs and proprietary Unix boxes. This was the classic whitebox approach—custom systems, sold directly, where credibility came from engineering and support, not from a brand name on the bezel. The founders talked about open source in idealistic terms—democratic, anti-monopoly, driven by merit. But they weren’t pretending this was a hobby. They wanted to build a major computing company, something with the ambition of a Dell or Compaq for the next era.

Even the name signaled exactly who they were for. “Penguin” was a nod to Tux, the Linux mascot. To the customers Penguin cared about—scientists, researchers, and technical computing teams—that wasn’t cute branding. It was instant recognition: these are our people.

Of course, the skeptics had a point. Penguin could celebrate a million-dollar month, but Dell was selling far more than that every day—just through its website. Dell could buy components at massive scale, squeezing prices in a way a small builder couldn’t. People wondered how companies like Penguin (and VA Linux Systems, another Linux-era darling) could compete when price pressure inevitably arrived. Ockman and co-founder David Huynh argued they’d win differently: by knowing Linux better, by building more creative systems, and by tightening operations enough to stay nimble even without Dell’s purchasing power.

Their early customer list tells you everything about how they survived: scientific computing groups, rendering farms, universities, and early high-performance computing environments. These weren’t shoppers in a big-box aisle. They were specialists buying capability, not logos.

Then the music stopped. When the dot-com crash hit, 2001 was extinction-level for a lot of tech companies. For Penguin, it became a forcing function. Ockman retook the CEO role, cut about a third of the staff, and reorganized the business around a brutal but simple goal: be profitable every month.

“It’s a shame, but it’s what has to be done,” he said at the time. “The number one thing is to continue the company for our customers and be profitable every month. We’re a profitable company with this restructuring.” He’d brought in professional management earlier—then stepped back in when survival demanded founder-level urgency.

The most important strategic move of this early era came a couple years later. Penguin had started as a Linux server company. In 2003, it acquired Scyld Software, a leader in Beowulf cluster management. Scyld was led by Donald Becker, a former NASA scientist and a pioneer in Linux networking development, who stayed on as CTO.

To understand why this mattered, you need to understand Beowulf. The original Beowulf idea came out of NASA Goddard in 1993: instead of paying for rare, expensive supercomputer time, you could string together lots of commodity PCs with Ethernet, run Linux on top, and get serious compute for a fraction of the cost. It was a conceptual breakthrough—and a practical one. NASA couldn’t afford to give every scientist “top-of-the-line Cray” cycles. Beowulf clusters made high-performance computing accessible, reportedly at around a tenth the cost.

Penguin became one of the companies that made that approach commercially viable. And buying Scyld changed Penguin’s role in the stack. They weren’t just assembling hardware anymore—they now owned the software layer that made clusters manageable in the real world. As Penguin would later put it: “Through the commercialization of the Beowulf cluster and Penguin Computing’s Scyld Clusterware, we have changed the face of technical computing for generations to come.”

The impact of Beowulf-style thinking is hard to overstate. Today, nearly every supercomputer in the Top500 is essentially a Beowulf-style cluster: commodity nodes running Linux. As of June 2021, seven of these supercomputers were run on Penguin’s computing technology. And in April 2022, Beowulf Cluster Computing was inducted into the Space Technology Hall of Fame—recognition for an idea born inside NASA that ended up reshaping the entire industry.

This is the early Penguin story in a nutshell: they didn’t win by being big. They won by being specific. They built real expertise for a real community, then deepened it by moving from “hardware vendor” to “hardware plus the software that makes it all work.” In a market where scale eventually crushes the generic, being niche and technical wasn’t a weakness. It was how they stayed alive.

III. The Wilderness Years: Commoditization & Search for Differentiation (2005-2015)

Victory creates its own problems. Linux won. By the mid-2000s, every major server vendor supported it. Dell, HP, IBM—pick a logo, and you could buy “Linux-ready” right off the menu. The specialized knowledge that once made Penguin stand out was turning into the minimum requirement to even be in the conversation.

And like a lot of early-era infrastructure startups, Penguin hit a long, frustrating stretch where staying relevant was harder than getting started. It had been a deeply sales-oriented company, but it learned the hard way that selling alone wouldn’t carry it. To keep up—and to actually support customers running mission-critical clusters—it needed a more balanced blend of sales, engineering, and research.

Because the whitebox server business was turning brutal. Components got cheaper, competitors multiplied, and the product itself started to feel interchangeable. Price competition intensified. Margins compressed. The existential question became: what does Penguin offer that Dell and HP don’t?

Penguin’s answer was to stop trying to win the generic server fight and lean into the places where complexity is the moat. It went deeper into high-performance computing and focused on markets where the workload, the deployment, and the support requirements create real switching costs. Over time, that specialization showed up in a portfolio that looked less like “we’ll build you a box” and more like “we’ll build you a system”: rack-level server solutions under the Tundra name, high-speed storage solutions called FrostByte, an Ethernet product line for software-defined networking, and the Scyld software brand for cluster management.

Then came the kind of customer that changes your credibility overnight: the U.S. government. In 2015, Penguin won a major contract with the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration—its tri-laboratory Commodity Technology Systems program, CTS-1. Under a $39 million award, Penguin delivered more than 7 petaFLOPS of computing capacity across Los Alamos National Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratories, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

The deployment was positioned as one of the world’s largest Open Compute-based installations. More importantly, it was a public stamp that Penguin could architect and deliver serious, production-grade HPC—at scale, under the scrutiny that comes with national lab workloads. As Penguin put it, these clusters would “provide needed computing capacity for NNSA's day-to-day work at the three labs managing the nation's nuclear deterrent.”

This is a very different kind of business than selling servers to a typical enterprise IT department. National-security computing isn’t won on price alone. It demands security clearances, compliance know-how, and years of proving you won’t break when the stakes are high. Penguin started building moats that a commodity sales force can’t conjure up overnight: technical credibility, deep government relationships, and fluency in specialized workloads.

And quietly, it began investing in another kind of edge—one that would look almost boring at the time, and then become everything later: cooling. High-density computing generates enormous heat, and as power consumption climbed, cooling started to become the constraint. Penguin worked on liquid and immersion cooling approaches early, including work with Asperitas “to incorporate an optimized immersion cooling capability into our HPC Solutions.” It was exactly the kind of unglamorous engineering that rarely makes headlines—until the whole industry suddenly needs it.

Penguin also took a swing at a version of cloud built for its own niche. In 2009 it launched Penguin Computing On-Demand, or POD: an HPC cloud service offered on a pay-as-you-go monthly basis. It wasn’t trying to be a general-purpose AWS clone. The model was bare-metal compute for running real HPC code, with each user accessing the environment through a virtualized login node. It was a signal that Penguin understood something early: HPC workloads have different needs, and “cloud” for scientists doesn’t look like cloud for web apps.

Still, for all the product depth and hard-won wins, Penguin remained a small player in a big pond. Intersect360 Research pegged it at about 1.2 percent of the HPC server market—enough to sustain a real business, but not enough to make it a household name. The company also touted ten supercomputers on the TOP500 list, eight of them at a petaflop or better.

That’s what these years were: not the glory days, not the breakout moment, but a long stretch of staying alive by getting sharper. Penguin stacked capabilities—cluster software, government-grade delivery, high-density design, cooling expertise—that didn’t necessarily translate into explosive growth in the moment.

But they were quietly assembling the exact toolkit that the next wave would demand.

IV. Key Inflection Point #1: The AI Training Breakthrough & NVIDIA Partnership (2016-2018)

By 2016, the next wave was already breaking. Deep learning wasn’t just an academic parlor trick anymore. AlphaGo beat the world champion. Image recognition started matching, and in some benchmarks beating, humans. And the center of gravity in compute began shifting from CPUs to GPUs.

But there was a catch. GPUs were phenomenal at training neural networks—and brutally unforgiving to deploy at scale.

One GPU server could run hot. A rack full of them became a thermal and power-management problem. Scale that to hundreds or thousands of GPUs and now you’re also dealing with specialized networking, storage bottlenecks, and a level of system integration that most enterprise IT teams simply weren’t staffed, or designed, to do. The industry was waking up to a new reality: AI training wasn’t “buy some servers.” It was infrastructure engineering.

This is where Penguin’s “wilderness years” suddenly looked like preparation. All those years building dense HPC systems for research labs and the U.S. government—plus the unsexy work in liquid and immersion cooling—mapped almost perfectly onto what AI training clusters demanded.

Then, in June 2018, Penguin’s trajectory snapped into a new shape. SMART Global Holdings, a publicly traded memory company, announced it was acquiring Penguin Computing, describing Penguin as a leader in specialty compute and storage solutions for AI, machine learning, and HPC built on open technologies and advanced architectures.

The headline number was “up to $85 million.” In practice, it was a $60 million price at close, plus up to $25 million more if Penguin hit certain profit milestones by year-end. That “up to” mattered. This wasn’t a casual trophy deal; it was structured around performance and near-term execution.

So why would a memory company buy an HPC integrator?

Because SMART could see where the puck was going. As one industry take put it, even though Penguin’s core business had been traditional HPC, SMART appeared intent on using the acquisition to gain a foothold in the adjacent AI and machine learning market—and expand its customer base beyond memory.

The deal also reflected something pragmatic: Penguin needed capital to scale. The $60 million figure included SMART assuming Penguin’s debts, which likely covered the roughly $33 million Penguin had borrowed earlier that year from Wells Fargo Supply Chain Finance to expand manufacturing capacity. Penguin wasn’t cash-rich; it was gearing up for bigger builds. SMART, meanwhile, had the balance sheet and public-market access to fund that push.

SMART’s own backstory set the stage. The business had been acquired from Solectron by private equity in 2004, went public in 2006, and then was taken private again in 2011 by funds affiliated with Silver Lake Partners and Silver Lake Sumeru. After that acquisition, SMART Worldwide repositioned itself into two business units. Then, in 2017, SMART Global Holdings priced its IPO—5.3 million shares at $11 each—and began trading on Nasdaq under the ticker SGH.

By the time it bought Penguin, SMART could do something Penguin couldn’t easily do alone: invest through the ramp. The combined entity now had the capital to pursue AI infrastructure aggressively, with the Penguin brand as the tip of the spear for systems and deployments, and SMART’s memory expertise as a natural complement to high-performance compute.

And this is where NVIDIA comes fully into the story.

Penguin’s relationship with NVIDIA deepened as the market shifted, and the company positioned itself as an expert partner for end-to-end AI infrastructure: planning, deployment, and ongoing management. Penguin highlighted its status as an NVIDIA Elite Partner and DGX-Ready Managed Services Provider, framing the value proposition in plain terms: organizations wanted AI, but they didn’t have the skills—or the operational muscle—to stand up and run GPU fleets reliably.

They also leaned on credibility built over years in HPC. Penguin pointed to its experience deploying CPU and GPU-based systems, along with the storage subsystems required for AI and machine learning architectures, HPC, and data analytics—and noted recognition in the NVIDIA ecosystem, including being named NVIDIA’s HPC Preferred OEM Partner of the Year multiple times.

Underneath the marketing language was a real technical distinction: AI training servers weren’t “regular servers with GPUs bolted on.” They demanded the full stack—high-speed networking like InfiniBand, thermal management that increasingly meant liquid cooling as GPU power climbed, storage architectures built for throughput, and the integration discipline to make it all behave as one system. This was exactly the kind of complexity Penguin had chosen to live in.

And strategically, it put Penguin in the best kind of infrastructure business: picks and shovels. Instead of trying to guess which AI lab or model would win, Penguin bet on the one thing every contender would need—more compute, more GPUs, more capacity, delivered in systems that actually worked in the real world.

V. Key Inflection Point #2: Going Public via SPAC & Scaling the Business (2021-2022)

Zoom out to 2021 and you can see why so many tech companies sprinted toward the public markets. The SPAC boom was at full blast. Going public looked faster, easier, and—at least for a moment—almost fashionable. At the same time, AI infrastructure spending was picking up speed.

But here’s the important nuance in Penguin’s story: the parent company, SMART Global Holdings, didn’t go public via SPAC in 2021. It was already public.

SMART priced a traditional IPO in May 2017—5.3 million ordinary shares at $11 per share—and began trading on the NASDAQ Global Select Market under the ticker “SGH.” That matters because the 2018 acquisition of Penguin Computing happened while SMART was already a public company. Penguin didn’t need a SPAC to tap public-market capital; it got that access simply by being inside SGH.

That timing turned out to be quietly valuable. As the AI infrastructure wave accelerated, SGH could fund growth without inheriting the “SPAC hangover” that hit so many 2021-era listings.

SGH also kept buying. In October 2020 it purchased Cree’s LED business in a deal that included $175 million of cash and notes, plus a potential earn-out of $125 million. Some analysts criticized the move as “diworsification”—a step away from the core that would later put parts of the portfolio on the shortlist for divestiture.

Then, in June 2022, SGH acquired Stratus Technologies, a long-established provider of fault-tolerant computing—systems designed for environments like ATMs, where downtime simply isn’t an option. SGH acquired Stratus for $225 million in cash, with a potential $50 million earn-out. At the time, the company said the deal would add more than $80 million of higher-margin recurring revenue.

Strategically, Stratus broadened the story beyond data-center training. It brought edge computing and mission-critical systems expertise—useful in a world where more and more AI inference happens outside the core data center.

Meanwhile, Penguin’s AI infrastructure opportunity was becoming very real, very visible, and very hard to replicate. The Meta partnership deepened into a crown-jewel reference. Meta said that, in its final build-out in mid-2022, the AI Research SuperCluster would use more than 16,000 NVIDIA GPUs and one exabyte of storage—what Meta believed would make it the largest AI supercomputer in the world.

Penguin leaned into that credibility. “As a full-service integration and services provider, Penguin has the capabilities to design at scale, deploy at speed, and provide managed services for NVIDIA DGX SuperPOD solutions,” the company said—pointing to work designing, building, deploying, and managing some of the largest AI training clusters in the world. It also said it managed over 50,000 NVIDIA GPUs for Fortune 100 customers, including Meta’s AI Research SuperCluster—built around 2,000 NVIDIA DGX systems and 16,000 NVIDIA A100 Tensor Core GPUs.

But scaling this business wasn’t just about demand. The operational reality was brutal. After 2020, supply chains were shaky across the industry. GPU allocation became a kind of quiet politics: NVIDIA couldn’t make enough chips to satisfy everyone, and priority went to partners with deep relationships and a track record of delivering. In that environment, Penguin’s long-standing NVIDIA partnership stopped being a nice logo for a slide deck and started functioning like a real competitive moat.

VI. Key Inflection Point #3: The ChatGPT Moment & Generative AI Boom (2023-2024)

November 30, 2022: ChatGPT launches. In a matter of weeks, generative AI jumps from “interesting research” to boardroom mandate. The pace was unprecedented—within two months, ChatGPT reportedly hit 100 million users, faster than any app in history.

The infrastructure shockwave was immediate. Every major company suddenly wanted GPU compute. Not in a budget cycle. Now. NVIDIA’s H100s turned into the most fought-over piece of hardware in tech, with allocations rationed and lead times stretching from months to nearly a year.

This was the moment Penguin had been accidentally training for. The company already had the relationships inside NVIDIA, the muscle memory to integrate and operate GPU clusters at scale, and the cooling playbook to keep dense systems stable. For customers staring down a “we need AI yesterday” problem, that combination mattered.

As CEO Mark Adams put it: “Our strong performance this quarter, highlighted by a 49% year-over-year increase in Advanced Computing revenue, reflects the continued execution of our strategy to support customers navigating the complexities of AI infrastructure implementation. Our approach as a provider of differentiated hardware, software and managed services enables us to serve as a trusted advisor for our large enterprise customers.”

At the same time, the competitive landscape started to tilt. The big incumbents—Dell, HPE, Lenovo—were absolutely in the game. But AI infrastructure wasn’t a standard enterprise refresh. It demanded deep systems engineering, new thermal constraints, and deployment patterns that didn’t fit neatly into traditional sales and support motions.

Penguin leaned hard into the credibility it had earned the slow way. “Penguin has 25 years of experience building and deploying large HPC clusters that run some of the world's most demanding workloads,” said Phil Pokorny, Penguin Solutions’ Chief Technology Officer. “Our technology partnerships allow us to be at the forefront of integrating new and emerging technologies, like immersion cooling.”

And cooling stopped being a niche feature and became a gating factor. As GPU power climbed, air cooling began to look less like a default and more like a limitation. “In the past six years alone, we've gone from 140-watt chips to 360-watt chips. This has taken us to the point where air cooling isn't sufficient. We implemented direct-to-chip liquid cooling, but we felt we needed to take that next step to immersion cooling.”

“As a data center operator, we believe immersion cooling is the future.” That belief—once a forward-looking engineering choice—started to pay off as customers realized you can’t scale GPU density if you can’t move heat.

The customer roster reflected the shift. Beyond Meta, Penguin deployed infrastructure for Shell, Georgia Tech, and a growing list of AI labs and enterprises. Shell, for example, powered its sustainable high-performance data centers with Penguin’s HPC solutions, including immersion cooling.

Then came the moment that made the transformation official. In October 2024, the company announced it was changing its name from SMART Global Holdings, Inc. to Penguin Solutions, Inc.—a signal that the center of gravity had moved. The announcement framed it as a strategic evolution toward areas including AI infrastructure deployment, advanced memory enterprise solutions, and high-performance computing, and noted that the company’s shares would trade under the new Nasdaq ticker symbol, “PENG.”

The rebrand was more than cosmetic. It was the company choosing its story. No longer a holding company with an assortment of businesses—now an AI infrastructure company wearing the name it had spent two decades building credibility around.

VII. The Modern Business Model & Competitive Position (2024-Present)

By the time the company renamed itself Penguin Solutions, it wasn’t just telling a new story. It was organizing the business around what it had effectively become: a systems-and-services company that designs, builds, deploys, and runs complex computing infrastructure for customers around the world.

On paper, Penguin operates through three segments: Advanced Computing, Integrated Memory, and Optimized LED. In practice, Advanced Computing is the engine of the modern Penguin narrative—the part most directly plugged into the AI infrastructure boom.

Advanced Computing is where Penguin does what it’s become known for: AI and HPC infrastructure. Not “a few servers,” but full GPU clusters—designed, integrated, deployed, and then managed in production. This is where the company sells its OriginAI platform, positioned as an “AI factory” infrastructure solution built on proven, pre-defined architectures. The pitch is simple: customers want the outcome—AI compute at scale—without spending a year reinventing the design. OriginAI pairs validated architectures with Penguin’s cluster management software and the services teams that plan, build, deploy, and operate these environments. In Penguin’s framing, it can scale from hundreds of GPUs to clusters with more than 16,000 GPUs.

Integrated Memory is the legacy SMART business line: specialty memory products used in embedded applications, networking, and telecom—less flashy than AI factories, but rooted in decades of domain expertise.

Optimized LED is the Cree LED business SGH bought in 2020. It’s widely viewed as non-core to the AI infrastructure thesis and has been seen by many as a potential divestiture candidate down the road.

The company’s place in the NVIDIA ecosystem remains central to how it competes. Penguin describes itself as an NVIDIA-certified Elite Solution Provider and DGX Managed Service Provider, and it’s also a Dell Technologies Authorized Partner. In a market where the bottleneck isn’t just demand but the ability to deliver working systems on time, these relationships—and the execution history behind them—matter.

Penguin’s “lock-in” isn’t the traditional software kind. It’s operational. Building an AI cluster forces hundreds of choices: GPUs, networking topology, cooling design, storage architecture, software stack, and how all of that gets monitored and maintained. Once a system is in production and delivering results, switching vendors doesn’t feel like swapping a supplier. It feels like risking downtime on one of the most expensive, mission-critical assets the company owns.

That’s also where the managed services layer becomes strategically important. It turns one-time infrastructure builds into ongoing operational relationships—and recurring revenue. Penguin points to Meta as the flagship example: helping manage the Meta Research Super Cluster, described as having over 2,000 NVIDIA DGX systems, 16,000 NVIDIA A100 Tensor Core GPUs, 500 PB of storage, and 40,000 NVIDIA InfiniBand networking links.

Penguin also markets the compounding advantage of experience at scale, saying its AI and HPC experts have more than 3.3 billion hours of GPU runtime management experience. The core point isn’t the exact number—it’s what it signals: this company has spent years learning the hard, unglamorous lessons of keeping massive GPU fleets stable in the real world.

Then, in 2024, Penguin added something it had historically lacked: a strategic partner that could help fund expansion and open doors internationally. The company announced the closing of a strategic investment by SK Telecom, an affiliate of SK Group. SKT, through Astra AI Infra LLC, acquired 200,000 convertible preferred shares at $1,000 per share.

The broader agreement was framed as a $200 million strategic investment signed in July 2024. Soon after, SK Telecom, SK hynix, and Penguin formed a task force to look for ways to combine their strengths to enhance customer offerings.

This wasn’t positioned as passive capital. Under a collaboration agreement, the three companies planned to explore opportunities in Asia-Pacific and Middle East markets, including Japan, as a path to global expansion. They also said they would build on their existing software capabilities to jointly develop and commercialize a full-stack software solution needed to build and operate AIDCs.

VIII. The Competitive Landscape & Strategic Alternatives

The AI infrastructure world has stratified. At the top end, hyperscalers are increasingly building their own chips—think AWS Trainium and Google TPU—because at their scale, vertical integration can beat buying GPUs forever. At the bottom end, the ODMs—Foxconn, Quanta, and the rest—can assemble commodity configurations cheaply and ship them in bulk. In the middle sits the battleground where Penguin plays: integrators and OEMs like Super Micro, Dell, and HPE, competing on who can actually deliver working systems, on time, at scale.

If you want the cleanest comp for Penguin, it’s Super Micro Computer. And the size gap is hard to miss. Super Micro reported about $22 billion in revenue for fiscal 2025, up from about $15 billion in fiscal 2024—breakneck growth. Penguin, by comparison, generated $1.37 billion in net sales in fiscal 2025, roughly a mid-single-digit percentage of Super Micro’s revenue.

But scale doesn’t automatically translate into safety. Super Micro’s rapid rise has come with very public scrutiny—governance issues, accounting delays, and margin pressure that raised a simple question: how durable is the model when the market normalizes? The financials show some of that tension. In fiscal 2025, Super Micro’s revenue jumped while net income declined versus the prior year—an early signal that in an AI gold rush, volume is one thing, but profitability is the real test.

Then there’s the ODM threat, which is very real—just not universally lethal. If a customer wants a standard configuration, especially at high volume, ODMs can win on price and speed. That’s the part of the market where “integration” starts to look like basic assembly. Penguin’s defensible ground is the work that doesn’t fit into a clean BOM: deployments with real systems engineering, tight thermal constraints, custom storage and networking, complicated rollouts, and the ongoing managed services layer that keeps expensive GPU fleets producing instead of sitting dark. Add in government and security-sensitive enterprise customers, and suddenly “can you build it?” becomes “can you deliver it, operate it, and stay compliant?”

Cloud is the other strategic pressure point, because it offers a tempting substitute: why buy anything when you can rent GPUs from AWS or Azure? Penguin’s implicit counterargument is that at serious scale, the math and the control often tilt back toward ownership. Large AI training runs can get punishingly expensive in the cloud. Many enterprises also want tighter control over data, privacy, and security as they move toward private AI. And during periods of GPU scarcity, allocation itself becomes part of the product—if you can’t reliably get capacity on your timeline, “renting” stops feeling flexible and starts feeling constrained.

Which brings us to Penguin’s most important—and most delicate—strategic asset: NVIDIA. The relationship can function like a moat when chips are scarce, because allocation priority and ecosystem credibility directly translate into wins. But it’s also a dependency. NVIDIA holds the power to shift routes to market, change partner programs, or favor different channels. For Penguin, maintaining that relationship isn’t just good business development. It’s existential.

IX. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE

The barriers here aren’t about buying parts. They’re about making the whole system work. At-scale AI infrastructure integration demands hard-earned expertise in thermal management, InfiniBand networking, storage throughput, GPU utilization, and the operational discipline to deploy and keep clusters running. NVIDIA’s partner ecosystem adds another layer of gating; becoming an Elite Partner isn’t something you do overnight. Still, the capital required for basic assembly is not that high. New entrants can show up quickly—but most can’t reliably execute the complex, high-stakes deployments where Penguin makes its living.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: HIGH

This is the defining constraint of the entire AI infrastructure market: NVIDIA. When one company controls the GPUs—and the allocation of those GPUs—supplier power is enormous. AMD exists as an alternative, but in AI training it remains a distant second. Other components like memory and networking are more competitively sourced, but in practice they orbit the real bottleneck. If you can’t get the GPUs, nothing else matters.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

Penguin’s buyers tend to be big and sophisticated: hyperscalers, large enterprises, and institutions with real engineering teams. They negotiate hard, and they can credibly threaten to switch vendors or bring more of the stack in-house. There are switching costs, but they’re mostly operational rather than contractual—painful, but not impossible. And when revenue is driven by a handful of large projects, customer concentration becomes its own kind of leverage: a few big purchasing decisions can swing results.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

The cloud is the obvious substitute. If you can rent GPUs, why own anything? But cloud hasn’t erased on-prem infrastructure—especially for customers who care about cost at scale, data control, privacy, or predictable access. Hyperscaler custom chips like TPU and Trainium reduce dependency on NVIDIA for the very largest players, but they don’t solve the broader market’s need for deployable, supported systems. Meanwhile, edge computing and private AI are creating durable demand for owned infrastructure in places the public cloud doesn’t neatly serve.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a knife fight. Super Micro, Dell, and HPE are all chasing the same deals, and ODM price pressure keeps the “just build a box” portion of the market brutally competitive. Differentiation exists—cooling expertise, managed services, deployment speed, and a track record at scale—but the center of gravity is still a crowded field where execution wins and margins are always under attack.

X. Strategic Analysis: Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economies: WEAK

Penguin is primarily an integrator, not a high-volume manufacturer. Scale helps a bit on component purchasing, but in AI infrastructure the bigger constraint is access—GPU allocation and the ability to actually deliver working systems. There are some efficiencies in reusing engineering patterns and support playbooks across deployments, but not the kind of structural cost advantage that compounds into a true scale moat.

Network Effects: NONE

Penguin’s customers don’t make the product better for other customers. There’s no network dynamic here. This is not a platform business.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK-MODERATE

For a while, legacy server vendors were slow to take liquid cooling and AI-specific integration seriously. Penguin leaned into both early, and that helped. But this edge is shrinking fast. Once AI infrastructure becomes everyone’s top priority, incumbents reallocate resources, copy the playbook, and close the gap. The counter-positioning window is real—but it isn’t permanent.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

The lock-in is operational. These deployments are complex, expensive, and tightly tied to day-to-day workflows. Ripping out and replacing an AI cluster is painful and risky, especially once it’s in production and delivering results. Still, this isn’t software-level lock-in with proprietary data formats or deep embedded dependencies. A motivated customer can move—just not quickly or casually.

Branding: WEAK

Penguin has credibility where it counts: among technical buyers who’ve lived through real HPC and AI deployments. But it’s not a broadly recognized brand, and it doesn’t have the kind of mass-market pull that creates demand on its own. Here, trust matters—but it’s earned through execution and references more than logo power.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE (potentially STRONG)

This is the heart of the story. Penguin’s NVIDIA Elite Partnership can translate into real advantage, especially when GPUs are scarce and allocation is a competitive weapon. Layer on more than 25 years of HPC experience, hands-on AI infrastructure work dating back to 2017, and deep expertise in liquid cooling and large-scale deployment, and you get a bundle of scarce resources: relationships, know-how, and battle-tested engineering talent that’s hard to replicate quickly.

Process Power: MODERATE

Penguin’s real product is the process: integrating, deploying, and operating complex GPU clusters reliably. The company has built institutional muscle around things like liquid cooling implementation and at-scale operations. Competitors can copy pieces of it, but doing it consistently—under real customer constraints—takes time. Still, well-resourced rivals can catch up.

Overall Assessment: Penguin’s durable advantages come mainly from Cornered Resource—its NVIDIA relationship and accumulated expertise—and from Switching Costs created by complex deployments. It’s not a “fortress moat” business. But in a high-growth market where getting systems live and keeping them stable is the whole game, execution and relationships can be decisive.

XI. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

🐂 Bull Case:

AI infrastructure spending still looks like it’s in the early innings. The training wave that produced ChatGPT was the starting gun, not the finish line. What comes next—enterprise “private AI,” inference at scale, and AI at the edge—plays out over years, not quarters. Every big organization now feels pressure to build AI capability, and most don’t have the in-house talent to design, deploy, and operate GPU infrastructure safely and efficiently.

Cooling is a perfect example of how Penguin can win. As GPU power density climbs, liquid cooling stops being an “advanced option” and becomes a requirement. Penguin’s long head start in high-density design and liquid and immersion cooling becomes a real advantage right when the broader market is forced to learn it. Layer in the NVIDIA relationship, and the bull story is that as the ecosystem consolidates, Penguin ends up in the smaller set of partners trusted to deliver the hard stuff.

The SK Telecom investment is the other tailwind. It’s not just capital—it’s a door-opener into regions where Penguin has had limited presence, like Asia-Pacific and the Middle East. And with SK hynix in the mix, the pitch becomes stronger: compute plus memory expertise plus deployment and operations, packaged into something closer to a full-stack infrastructure offering.

Financially, the company pointed to continued momentum. In the third quarter of fiscal 2025, Penguin Solutions reported net sales of $324 million, up 7.9% from the year-ago quarter. The bigger point isn’t the single quarter—it’s that this is a business that can land and execute large, complex projects in a market where execution is the whole game.

From an investor lens, the upside case is straightforward: if Penguin can make results more predictable and expand profitability, the valuation can rerate. And there’s optionality in how this ends—larger infrastructure players or private equity could look at Penguin as a way to buy real AI infrastructure capability instead of building it from scratch.

🐻 Bear Case:

The bear case starts with a single-word problem: NVIDIA. If NVIDIA changes allocation priorities, shifts routes to market, favors different partners, or pushes further into vertical integration, Penguin’s advantage can disappear fast. And there’s no clean substitute for NVIDIA GPUs at scale today.

Competition is another pressure point. Dell and HPE aren’t asleep; they’re just late. Once they decide AI infrastructure is strategic, they can bring enormous global sales reach and channel power to bear—and they can tolerate lower margins while they build capability. If AI infrastructure becomes more standardized, it gets harder for Penguin to defend premium positioning.

Then there’s concentration and lumpiness. This is a project-driven business, and big projects can swing results dramatically. Meta is a public reference point, but many other customers aren’t disclosed. Losing a major account—or even seeing a few large deployments slip in timing—can hit revenue hard.

At the top end, hyperscalers continuing to bring compute in-house also reduces the addressable market for integrators. Custom silicon efforts like AWS Trainium and Google TPU won’t replace NVIDIA everywhere, but they do mean the biggest buyers are actively trying to reduce dependence on the GPU supply chain. And at the other end, ODMs like Foxconn and Quanta going direct can compress margins on anything that looks like a commodity configuration.

Portfolio complexity is part of the bear narrative too. The LED business is often viewed as non-core and a distraction. The argument goes that non-core assets dilute management attention and obscure the economics of the AI infrastructure engine underneath.

Finally, there’s cycle risk. If AI spending pauses—because of macro pressure, skepticism about ROI, or simple infrastructure overbuild—growth can stall quickly. In that world, Penguin looks less like a uniquely advantaged picks-and-shovels provider and more like a smaller player facing larger, better-capitalized competitors who can outspend it when the market tightens.

XII. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

Timing is everything. Penguin spent decades building expertise in high-density systems, liquid cooling, and GPU-heavy integration—skills that suddenly became priceless when AI training took off. You can’t script the timing, but you can invest in capabilities that give you options when the world changes.

Survival creates optionality. Penguin got punched in the dot-com crash, made painful cuts, and reorganized around one unglamorous goal: stay profitable and stay alive. That wasn’t a victory lap. It was endurance. And endurance is what gave them the chance to catch the AI wave years later. Companies that don’t survive never get a second act.

Picks-and-shovels advantage. Infrastructure is a way to win without picking the “right” AI company. Penguin doesn’t need to guess which model or lab becomes the next OpenAI. If the category keeps scaling, everyone needs GPUs, networking, cooling, and operations—and Penguin gets paid when any of them show up.

Technical credibility compounds. Government contracts, research lab deployments, and supercomputer work weren’t just revenue. They were reputation. In AI infrastructure, where failures are expensive and public, trust is currency—and Penguin built that trust the slow way, then carried it into a much bigger market.

Partnership leverage cuts both ways. NVIDIA is a force multiplier for Penguin: ecosystem credibility, technical alignment, and, in tight markets, access. It’s also a single point of dependency. The lesson isn’t “avoid partnerships.” It’s to treat them like strategic assets: protect them, deepen them, and diversify where you realistically can.

Niche can become mainstream. Liquid cooling and cluster management used to sound like specialist hobbies. Then GPUs got so power-dense that cooling became a constraint for the whole industry. The expertise that once felt like a narrow corner turned into the center of the map.

Know your place in the value chain. Being the integrator is valuable—but it’s not forgiving. Penguin doesn’t control GPU supply, and it doesn’t own a software platform that automatically locks customers in. Its edge has to be earned over and over through engineering, delivery, and operations.

Public markets require scale. Renaming the parent company to Penguin Solutions wasn’t just branding. It was focus. Public companies can’t afford a fuzzy identity for long—investors want a clear story, and the business has to keep delivering results that match it.

XIII. The Future & What to Watch

The biggest question hovering over the entire story is the simplest one: is this AI infrastructure boom structural, or is it a cycle? In the bull version of the world, we’re still in the early stages of multi-year buildouts as enterprises adopt AI, inference scales, and edge deployments spread compute outward. In the bear version, the industry overbuilds, enthusiasm cools into an “AI winter 2.0,” or the public cloud absorbs more of the demand than on-prem ownership ever does.

The next big test will come from NVIDIA’s roadmap. Blackwell, and then Rubin, will tell us a lot about whether Penguin can keep its spot in line. If NVIDIA ramps supply enough that allocation pressure fades, then an Elite partnership becomes less of a weapon. But the opposite could also be true: if NVIDIA tightens and consolidates its ecosystem, deep relationships and proven execution could matter even more.

Then there’s competition. Dell and HPE are not static targets; the question is how quickly they close the gap on the messy, real-world engineering of dense GPU deployments. On the other side, ODMs can keep pushing down the value of anything that looks like standard hardware. That puts pressure on Penguin’s bet: that its service layer—design, deployment, and ongoing operations—creates enough differentiation to justify premium positioning.

Edge AI and inference are the other major growth vectors to watch. Training tends to concentrate, especially at hyperscale. Inference spreads out—to factories, hospitals, retail, telecom, and all the places where latency and data residency matter. Penguin has a potential bridge here through Stratus and its edge computing footprint, but “positioned for” isn’t the same as “winning.” Execution will be the proof.

International expansion is another open thread. The SK Telecom partnership could become a real door into Asia-Pacific and the Middle East—or it could become a distraction if it pulls attention away from the North American core while the market is still moving fast.

And finally, there’s the exit question. Penguin could keep acquiring capabilities and customers, but it could just as easily become a target itself. Private equity might see a chance to buy a hard-to-build set of relationships and expertise. Larger infrastructure players might decide it’s faster to acquire AI integration and managed services capability than to recreate it.

Key Metrics to Track:

-

Advanced Computing segment revenue growth and gross margin — The cleanest read on whether the AI infrastructure engine is scaling profitably, or getting squeezed as the market gets more crowded.

-

NVIDIA relationship indicators — Elite partner status, allocation commentary, and certifications for new architectures. Any slippage here is more than optics; it’s a signal that the core “cornered resource” may be weakening.

XIV. Epilogue: Recent Developments & Final Reflections

Penguin Solutions most recently reported financial results for Q4 and for full-year fiscal 2025, including net sales of $1.37 billion for the year. It’s a reminder that this isn’t just an interesting technical story—it’s a real operating business, growing while the AI infrastructure build-out reshapes the market around it.

The October 2024 rebrand—from SMART Global Holdings to Penguin Solutions—was the company making its bet explicit. The center of gravity had shifted, and the name caught up. Then, in December 2024, the SK Telecom investment closed, bringing not just capital but a partnership designed to help open doors and accelerate geographic expansion. Management’s message has been consistent: AI infrastructure demand remains strong, and expansion beyond the company’s historical base is a priority.

What makes this story compelling isn’t the headline numbers. It’s the arc: a company founded by a 25-year-old open-source advocate to build Linux machines, surviving the dot-com crash, buying cluster software rooted in NASA’s Beowulf work, grinding through years serving government labs and scientific researchers—and then, almost improbably, finding itself in the slipstream of the biggest compute land grab in decades.

The broader lesson is that the most important companies aren’t always the ones on the posters. NVIDIA gets the spotlight. OpenAI gets the cultural attention. But the infrastructure underneath—cooling, cluster management, integration, and operations—is where a different kind of value gets created. When the limiting factor isn’t ideas but execution, the companies that can make systems run reliably at scale become essential.

And there’s a deeper throughline here. The Beowulf approach helped democratize high-performance computing by proving you could get serious capability from commodity building blocks—if you knew how to assemble and manage them. Scyld and Penguin Solutions helped commercialize that model, and that same “make commodity compute act like a supercomputer” philosophy now shows up again in modern GPU clusters.

For investors, Penguin Solutions’ risk/reward profile is unusually clean to describe: exposure to AI infrastructure without paying NVIDIA’s valuation—but with real risks around NVIDIA dependency, customer concentration, and an execution-heavy competitive position in a crowded market. The path to upside runs through continued large customer wins, improving margins as services become a larger part of the mix, and proving it can expand internationally without stretching the organization too thin.

The ultimate question is the one the whole category is now wrestling with: is Penguin building a durable franchise, or riding a cyclical wave? The answer depends on whether AI infrastructure integration stays specialized and relationship-driven—or eventually commoditizes the way traditional server assembly did. Penguin’s first 25 years suggest it knows how to adapt. The next chapter will test whether that’s still enough.

XV. Further Reading

Top 10 Resources for Deeper Research:

-

Penguin Solutions SEC filings (10-K, 10-Q, DEF 14A) on SEC.gov — The primary source for how the business actually works: segment performance, risk factors, customer concentration, and what management chooses to highlight (and disclose).

-

NVIDIA Partner Network documentation — The best window into how the ecosystem is structured, what different partner tiers mean, and why certifications and status can translate into real go-to-market advantage.

-

"The Datacenter as a Computer" by Barroso, Clidaras, Hölzle — A foundational guide to how modern, warehouse-scale computing systems are designed—and why integration details matter as much as the chips.

-

Gartner/IDC reports on AI infrastructure and x86 server market trends — Useful for market sizing, competitive context, and understanding how AI infrastructure is reshaping the broader server landscape.

-

Super Micro Computer filings and presentations — The closest public-company comparison point for Penguin, and a great way to study the economics and dynamics of the AI server boom.

-

"Chip War" by Chris Miller — Essential background on semiconductor supply chains and geopolitics—the forces that turn “GPU shortages” into strategy, not just logistics.

-

AI infrastructure podcasts: Latent Space, Gradient Dissent episodes on infrastructure — Deep, practitioner-level conversations on what breaks in real deployments and what it takes to run AI systems reliably at scale.

-

Data Center Dynamics and Data Center Knowledge publications — Great ongoing coverage of the unglamorous constraints that shape the category: power, cooling, density, and build-out timelines.

-

NVIDIA GTC conference presentations — A direct feed of where NVIDIA is taking the hardware and software stack, and how infrastructure partners are expected to keep up.

-

Historical HPC market analysis — Helpful context for seeing Penguin’s roots clearly: how supercomputing evolved, why clustering won, and how that legacy feeds directly into today’s AI infrastructure playbook.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music