Pegasystems Inc.: The Story of Enterprise Software's Best-Kept Secret

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

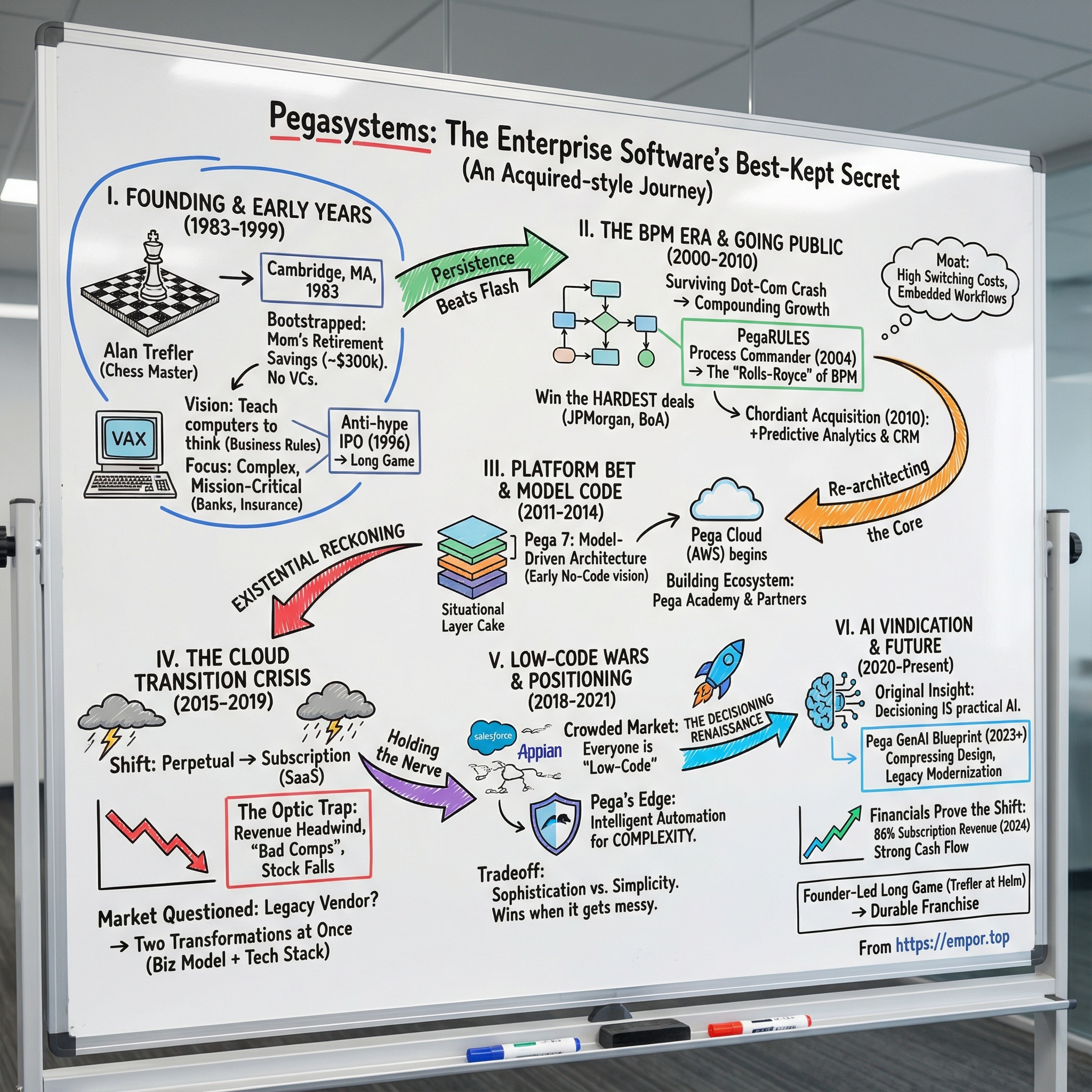

Picture a chess grandmaster who decided to teach computers how to think—not just about moving pieces across a board, but about moving entire corporations through their hardest decisions. That person is Alan Trefler. And the company he built—starting in a modest Cambridge office and funded with his mother’s retirement savings—has quietly become one of the most durable franchises in enterprise software.

Alan N. Trefler, born March 10, 1956, is an American billionaire businessman and chess master best known as the founder and CEO of Pegasystems. He started the company in 1983. Pegasystems is based in Waltham, Massachusetts, and has been publicly traded since 1996 on NASDAQ under the ticker PEGA.

Today, Pegasystems generates more than $1.5 billion in annual revenue. It’s embedded inside the operating core of huge institutions—banks, insurers, healthcare companies, and government agencies. By Pega’s own account, its customer list includes seven of the top ten U.S. banks, seven of the top ten asset managers, seven of the top ten U.S. health plans, five of the top ten U.S. insurers, four of the top five U.S. telcos, the five largest pharmaceutical companies, and more than 30 major federal agencies. And yet, outside of enterprise IT circles, Pega is still a name most people have never heard.

So how did a workflow automation company founded during the Reagan administration survive the dot-com crash, make it through the brutal shift from on-prem software to SaaS, and end up positioned for the AI era? The answer is a rare combination: technical depth that borders on obsession, switching costs that make “rip and replace” nearly unthinkable, and a founder who consistently played the long game.

This story is also a window into how enterprise software really works. Persistence beats flash. The deepest moats aren’t always the loudest. And the companies closest to mission-critical processes can become enormous while hiding in plain sight. Trefler, still at the helm, has spent decades as a trusted advisor to senior executives around the world—less Silicon Valley celebrity, more steady architect of how big organizations actually run.

And make no mistake: this journey wasn’t linear. Pegasystems hit an existential crisis during its cloud transition. The stock fell hard as Wall Street questioned whether a legacy on-prem vendor could reinvent itself. The company endured a $2 billion lawsuit from a bitter rival. Somehow, it came out the other side. Four decades under a single founder-CEO later, Pega remains one of tech’s most remarkable—and least celebrated—success stories.

II. Founding Context & Early Years (1983–1999)

Pega’s origin story doesn’t start in Silicon Valley. It starts in a Brookline antique restoration shop.

Growing up, Trefler worked in his father’s business, Trefler & Sons Antique Restoring. It’s easy to miss how foundational that was. Day after day, he watched his father deal with picky customers, impossible constraints, and high expectations—then still deliver work that met the brief. The lesson that stuck wasn’t “sell harder.” It was: understand what the customer actually needs, then deliver it precisely. That mindset—service as a craft—would show up later in the way Pega built software for enterprises that couldn’t afford mistakes.

The other formative arena was chess.

Before Pegasystems, Trefler was already comfortable walking into rooms where everyone else looked stronger on paper. In 1975, he tied for first at the World Open Chess Championship with grandmaster Pal Benko. He’d entered as a Dartmouth student with a 2075 Elo rating—well below master level and nowhere near the favorites. He also worked as a software engineer at Casher Associates and TMI Systems.

Trefler graduated from Dartmouth College with distinction in Economics and Computer Science, and won the John G. Kemeny prize in computing. The through-line here isn’t just “smart founder.” It’s the combination of structured, adversarial thinking—chess—and the impulse to encode that structure into systems.

In the early 1980s, he built chess-playing computer systems. Then he made the leap that would define his company: if you can teach a computer to evaluate a board position and choose a next move, you can teach it to evaluate a business situation and choose the next best action. That bridge—from chess algorithms to business rules—became the foundation of everything Pega would build.

At 27, he had a conventional path in front of him: Stanford Business School. Instead, he chose the harder one. In April 1983, he founded Pegasystems.

He started the company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with Kenneth W. Olson and Ira Vishner. The initial funding wasn’t venture capital. It was more than $300,000 from his mother’s retirement funds. No institutional backstop. Just conviction—and a very personal sense of responsibility to make it work.

The founding idea was wildly ahead of its time. Trefler looked at the “primitive” enterprise systems of the day—especially in banks and insurance companies—and saw a gap between what the business needed and what software could express. As he put it:

"when I started Pega, it was with the vision that we could create a set of metaphors—an intermediate visual language that would enable business people to more directly instruct the machine..."

In 1983, that was almost science fiction. Personal computers were still novelties. “Enterprise software” meant mainframes, green screens, and armies of COBOL developers. And yet here was Trefler describing a world where the business could define the rules and the workflow directly, without translating everything through programmers.

The hardware reality was… less futuristic. Trefler remembered it like this:

"Now, the computer systems at the time that we could use were implemented by IBM, which was an enormous machine we could not possibly afford. And Digital Equipment Corporation, which created a machine called the VAX, which is about the size of a very large dining room table and has probably 1/100 of the power of my current cell phone. And, you know, that's how we built the first generation of our software."

And the early days were as scrappy as you’d hope. When their VAX arrived, the building basically couldn’t accommodate it. It had to be hoisted up an elevator shaft because there wasn’t a workable elevator. At one point, Trefler left to meet a prospect and returned to chaos—one of his co-founders had sent the VAX away because they didn’t have the right equipment to get it upstairs. So they sprinted around Cambridge trying to catch the truck carrying their only computer.

It’s an almost perfect startup parable: the founders, literally chasing the machine that will determine whether the company lives.

Even the name carried Trefler’s fingerprints. It nods to chess—he liked the idea of having a chess piece in the logo—and to the myth of Pegasus. Trefler also connected it to a more personal origin: he and his co-founders were leaving behind a company they felt had “sold out the staff,” and they believed they could build something better.

In its early years, Pegasystems focused on case management, including work for companies such as American Express. The pattern was set early: Pega aimed at the biggest, messiest, most operationally critical environments—banks, insurers, and financial services giants where “simple software” simply didn’t survive contact with reality.

And while most tech companies of that era were learning how to play the venture capital game, Pega opted out. Trefler believed the incentives could be corrosive:

"One of the problems with venture capital culture is that it puts a clock on businesses. Typically, VC-funded businesses need to go public or be purchased in five to seven years."

This wasn’t a moral stance as much as a strategic one. Pega was building in a domain where trust takes years to earn and implementations can take forever. A five-to-seven-year clock would force the wrong decisions. So Pega bootstrapped through the 1980s, building expert systems and decision management tools back when “artificial intelligence” was an academic label—not a budget line item.

By the late 1990s, the technical foundation was hardening into real IP. In 1998, Trefler was granted a U.S. patent for Pegasystems’ rules-based architecture—the framework that underpinned its business process management solutions. And the company had already planted itself in exactly the industries where rules, exceptions, and edge cases aren’t nuisances—they are the business: insurance underwriting, banking operations, telecom billing.

Pega did go public in 1996, trading on NASDAQ under the symbol PEGA. But this wasn’t the classic, hype-driven IPO story. It was a way to fund the next chapter while keeping the company’s long-term posture intact. Trefler, who founded the company at 27, remained clerk and president until 1999, and afterwards became CEO.

In hindsight, the early era set the template for everything that followed: obsessive technical depth, a bias toward the hardest enterprise problems, implementations that embedded Pega deep in mission-critical workflows—and a founder determined to optimize for durability, not applause.

III. The BPM Era & Going Public (2000–2010)

The turn of the millennium was supposed to be the internet’s coming-out party. Instead, it became enterprise software’s stress test: dot-com mania, a spectacular crash, and then a wave of consolidation as big vendors swallowed smaller ones.

For Pegasystems, it was also an opening.

While consumer web startups were vaporizing, Pega’s customers—banks, insurers, healthcare companies—kept funding the unglamorous work of process automation. When your business still runs on paper-heavy workflows and manual decisioning, the case for automation doesn’t disappear in a downturn. If anything, tighter budgets make “do more with less” feel urgent, not optional.

That’s why Pega could keep compounding through this era. Between 2005 and 2015, it averaged 21% annual sales growth. Not because it rode a hype wave, but because it sold into industries with long investment cycles, high regulatory pressure, and enormous switching costs once the software was in.

The product story matters here, too. In 2004, the company introduced PegaRULES Process Commander, later evolving into what’s now the Pega Platform. At the center was the same core idea Trefler had been refining since the 1980s: a rules-based engine that can model complex business decisions and workflows—and then execute them consistently across channels.

In the BPM world, that made Pega the “Rolls-Royce” option. Powerful. Elegant. And priced accordingly. As analyst Neil Ward-Dutton of MWD Advisors put it: “Pega is super-sophisticated. And it’s brilliant if you need to do those incredibly big, multi-year, complicated transformations.”

That became the tradeoff Pega embraced. It wasn’t trying to win every deal. It was trying to win the deals where complexity would break simpler tools.

The customer roster told you exactly who those deals came from: JPMorgan, ING, Lloyds Banking Group, Cisco, Philips, Everything Everywhere, and Bank of America. Companies used Pega for everything from automating business rules in call centers to managing health insurance claims—and even, at Heathrow Airport, coordinating the fueling, maintenance, and restocking of aircraft.

Once Pega got embedded in those workflows, it didn’t behave like a typical software product. It behaved like infrastructure. Implementations could take years. Organizations invested millions. Teams encoded institutional knowledge into configurations. And that’s the real moat: replacing Pega wasn’t just swapping software—it meant untangling how the business actually operated.

The biggest strategic move of this era arrived in 2010 with the Chordiant acquisition. In March of that year, Pegasystems acquired enterprise software company Chordiant for around $161.5 million.

Chordiant, headquartered in Cupertino, sold software aimed at improving customer experience, with offerings spanning BPM, customer relationship management, and enterprise decision management. It claimed more than 200 customers, including financial institutions like AIG, Barclays, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, and ING.

For Pega, the deal brought two things it cared deeply about: predictive analytics capabilities and a wider foothold in telecommunications and healthcare. It also pushed Pega’s story beyond “process automation” and toward something that would become the next enterprise obsession: orchestrating the customer experience. Pega integrated Chordiant’s CRM and predictive analytics technology into its own platform, letting businesses apply decisioning across a broader range of interactions—not just internal workflow, but customer-facing moments too.

By the end of the decade, Pega’s footprint across major industries was hard to miss. The company said its software was used by 7 of the top 10 insurance companies, 8 of the top 10 global banks, 2 of the top 5 global telecommunications firms, and 4 of the top 5 health insurance payers—names like Farmers Insurance Group, JPMorgan Chase, Aetna, AIG, Amgen, Bank of America, HSBC, and numerous Blue Cross Blue Shield organizations.

By 2010, Pega had earned a clear position: the premium choice for high-stakes, high-complexity enterprise automation. The question wasn’t whether the software worked. The question was whether Pega could scale its go-to-market and expand awareness beyond the circles that already knew it.

Because the next industry shift—the one that would force every enterprise vendor to rewrite its business model—was already gathering speed.

IV. The Model Code Architecture & Platform Bet (2011–2014)

The early 2010s forced every serious enterprise software company to answer a simple question: were you going to keep patching an aging foundation, or were you going to rebuild for what came next?

Alan Trefler chose the painful option. While competitors shipped incremental upgrades, Pega set out to re-architect its platform—work that would take years, risk near-term disruption, and only pay off if the industry moved the way Trefler believed it would.

The result was Pega 7, built to manage the full application life cycle end-to-end. It brought together support for agile development, automated testing, deployment, and continuous monitoring—less “install it and hope,” more “run it like a living system.”

Under the hood, one of the defining ideas was something Pega called the Situational Layer Cake. Yes, the name sounds like peak enterprise branding. But the concept solved a real, expensive problem.

In traditional enterprise software, every new geography, business unit, or product line tends to produce a fork: another customized version of the same application. Over time, those forks become incompatible. Upgrades turn into nightmares. Maintenance costs balloon. Everyone ends up trapped.

Pega’s approach organized change in layers. Shared enterprise logic sits at the base, with specialized rules layered above it for different markets, customer segments, and product lines. That meant a single application could behave differently depending on context—without creating a sprawl of separate codebases. For large organizations with lots of variation and lots of compliance constraints, that wasn’t just elegant. It was a reason to standardize on Pega.

The other big bet was “model-driven” development. Pega’s Unified Model Driven Architecture—patented, and central to the platform—was designed so teams could model an application once and let the system generate the underlying code. Pega positioned this as no-code software: configure the rules and workflow, and the platform does the rest.

That vision landed before the market had a name for it. “Low-code” and “no-code” wouldn’t become buzzwords for years, but Pega was already building toward a world where business users demanded more direct control, and where companies couldn’t afford to rebuild the same processes from scratch over and over.

Then came a quieter move that, in hindsight, mattered a lot: in 2012, Pega Cloud was introduced using Amazon Web Services. Pega wasn’t walking away from on-premise customers—far from it. But it was laying track in the direction the industry would eventually sprint.

From 2013 through 2014, Pega filled in more pieces around the platform through acquisitions and investment. In October 2013, it acquired mobile application developer Antenna Software for $27.7 million, adding mobile development capability right as smartphones reshaped customer engagement. It also acquired MeshLabs, a Bangalore-based text mining startup, and Firefly, a co-browsing tool. Together, these expanded what Pega could do with unstructured data and real-time customer collaboration—more signals, more context, more ability to steer a customer interaction instead of just recording it.

By 2014, Pegasystems was also investing in network operations in North America and India to support its growing cloud services footprint.

As the platform grew more capable, another reality became unavoidable: Pega’s software was powerful, but it wasn’t plug-and-play. Enterprises needed skilled people to implement it—and Pega couldn’t staff every engagement itself.

So the partner ecosystem became strategic infrastructure. By early 2015, Pegasystems had active partnerships with IT outsourcing firms including Hexaware, NIIT Incessant Technologies, Tata Consultancy Services, Infosys, Wipro, HCL Technologies, Accenture, and Cognizant. This gave Pega reach and credibility in the enterprise, while keeping it from becoming a services-heavy business with all the margin pressure that implies.

To make those partners effective, Trefler created Pega Academy in 2014—online resources, classroom training, and certification designed to produce more Pega specialists. He could point to a long list of consulting firms that built Pega practices through the program, including Accenture, Ernst & Young, and Cognizant. Wipro even built a Pega campus in India, and smaller firms like Virtusa developed specialist teams too.

By early 2015, Pegasystems had roughly 3,000 employees, 30 offices, and more than half a billion dollars in revenue. And on November 25, 2013, Trefler’s net worth surpassed $1 billion, driven by his 52 percent ownership stake in the company.

Pega had reached real scale—deep in the Fortune 500, with a modernizing platform strategy and an ecosystem to implement it.

But the biggest test was about to arrive. Enterprise software was shifting into the cloud era, and Pega’s predominantly on-premise business model was headed toward an existential reckoning.

V. THE CLOUD TRANSITION CRISIS (2015–2019)

Every enterprise software company eventually hits the same wall: the market changes, and your business model has to change with it. For Pegasystems, that wall showed up in 2016 and 2017—suddenly, unmistakably, and painfully in public.

The problem wasn’t that customers stopped wanting Pega. It was that they stopped wanting to buy it the old way.

For decades, Pega’s engine ran on perpetual licenses: a big upfront check for the right to use the software, followed by smaller annual maintenance fees. It was high-margin, but lumpy. One “whale” deal could make a quarter. The downside was that it trained investors to judge the company on the timing of a few giant transactions.

Then enterprise buying norms shifted. Subscription models became the expectation: smaller payments over time, recurring revenue, and a tighter linkage between vendor and customer outcomes. Salesforce had mainstreamed the playbook. Procurement teams loved it. CFOs loved it. And Pega’s customers began pushing back on the idea of big, permanent commitments.

The result was the classic cloud-transition trap. When a deal that used to be booked largely upfront turns into a subscription, the cash may still be attractive over the life of the contract—but the revenue you recognize immediately shrinks. So the healthier your transition is, the worse your near-term reported numbers can look.

That dynamic showed up in the worst possible way: in the optics.

Pegasystems took heat for “bad comps” as the subscription mix grew and earlier large license deals stopped repeating on schedule. In one quarter, revenue missed consensus sharply, and it looked, from the outside, like something had broken. In reality, much of the mismatch came down to timing—especially compared to the prior year’s unusually large license deals.

Other enterprise companies had lived through the same turbulence—Autodesk is a common comparison—but it doesn’t feel any less brutal when it’s your own income statement. Even in quarters where the underlying business indicators improved, headline revenue could dip year over year. And when a company prints negative growth in the middle of a supposed reinvention, the market doesn’t wait around for nuance.

Inside Pega’s own commentary, you can hear the tension between what was happening operationally and what was being reported financially. In 2017, CFO Ken Stillwell framed it like this:

"Our movement to recurring commitments further accelerated in the third quarter of 2017 with a significant increase in our cloud offering. This mix shift has contributed to the year over year growth of $65 million in ACV and $104 million in Term license and Cloud backlog. This faster than expected shift to recurring has led to a headwind of over $40 million in revenue and $0.33 in diluted EPS year to date. Nonetheless, we are pleased by this transition to recurring and that our clients are increasing their move to cloud and subscription licensing."

In other words: the business was booking more recurring value, building backlog, and pulling customers into cloud commitments. But the same progress created a meaningful revenue and earnings headwind in the current year.

As if that weren’t enough, the adoption of ASC 606 piled on another layer of confusion. Changes in how revenue was recognized across term licenses, subscriptions, and cloud services made year-over-year comparisons messy and, for many observers, borderline unreadable. Even when guidance looked solid under the new standard, the path between quarters could feel like whiplash.

That’s how you end up with a market narrative that’s simultaneously wrong and understandable: investors saw noisy results and assumed the company was struggling. Analysts openly questioned whether Pega could pull off the shift without damaging near-term performance more than expected. And the competitive framing turned harsh fast. CRM was crowded and dominated by Salesforce, with other giants like Oracle and Microsoft always in the conversation. In BPM and low-code, Appian was fresh off its IPO and marketing itself as simpler and more modern. Pega, meanwhile, carried the label every on-prem veteran fears: “legacy provider.”

So a lot of the sentiment boiled down to some version of: too much execution risk, too much competition, and not enough clarity in the numbers.

But the turmoil wasn’t only financial. The technology had to evolve, too.

By 2017, the industry conversation had shifted toward microservices and cloud-native architectures. Pega’s platform had long been built as a powerful, integrated system—a monolith in the technical sense, even as it embedded lots of modern capabilities. As cloud expectations rose, Pega began the slow, careful work of transforming its architecture toward microservices, while also upgrading its cloud operations to meet enterprise demands for reliability and performance. And crucially, customers did keep moving: more organizations began migrating from on-premise setups to Pega’s cloud services.

It was, effectively, two transformations at once: changing how the company sold and got paid, while also modernizing how the product was delivered and run.

By Pega’s own description, the cloud transition that began in early 2018 typically takes four to five years. The company expected to complete that journey by early 2023. And while that finish line sat beyond this chapter’s timeline, the implications were already clear during 2018 and 2019: reported quarterly results would remain choppy, and the clearer picture of the underlying fundamentals would only emerge later.

There’s an irony at the heart of this phase: the faster Pega succeeded in shifting customers to cloud and subscriptions, the worse the near-term revenue optics could become. That’s the cruel math. The quality of the business improves, but the scoreboard looks like it’s moving in the wrong direction.

That’s what made this period a genuine crisis. Not because the company lacked demand, but because the transition punished the numbers investors were trained to watch. It also compressed Pega between two forces: the expectations of a modern SaaS market and the realities of a deeply embedded enterprise platform that can’t be rewritten overnight.

And it taught a few hard lessons.

First, founder-led companies can choose pain now for durability later in a way many public-company management teams simply can’t. Second, enterprise transitions happen on multi-year timelines—quarterly snapshots can be wildly misleading. Third, in enterprise software, the quality of revenue often matters more than the quantity you can recognize this quarter.

For the investors and customers who understood what was happening beneath the surface, this was the “hold your nerve” era. For everyone else, it looked like uncertainty.

Either way, Pegasystems was committed. The company was rebuilding its business model in public—and there was no easy way back.

VI. The Low-Code Wars & Market Positioning (2018–2021)

Just as Pega fought through the cloud transition, the ground under it shifted again. “Low-code” stopped being a niche idea and became the default pitch in enterprise software. Suddenly, everyone claimed they could help you build apps faster, automate work, and modernize legacy systems—without needing armies of developers.

For Pega, that created a strange kind of pressure. On paper, low-code should have been its moment. Trefler had been preaching the same core idea since the 1980s: capture business logic as rules and models, not endless hand-coded software. But once low-code became a buzzword, Pega wasn’t just competing with the old giants anymore. It was competing with a crowded category full of platforms optimized for speed, simplicity, and adoption.

The competitor list got wide fast. Salesforce was everywhere in CRM—and pushed into low-code with the Lightning Platform. Microsoft showed up with Power Platform for building apps and automations, plus Dynamics 365 for CRM and customer service. ServiceNow expanded beyond IT service management into broader workflow automation. IBM pushed Digital Business Automation. And in Pega’s most direct lane—BPM and case management—Appian positioned itself as the modern low-code alternative, while OutSystems and Mendix sold rapid application development as the cure for slow-moving IT.

In other words: where Pega once sparred mainly with IBM, Oracle, and SAP, it now faced a swarm of credible options. And many of them were easier to start with.

Part of what made this era so intense was that low-code platforms benefited from the same forces reshaping the rest of software: cloud delivery, easier integration, and a world where data from almost anywhere could be pulled into an app. As automation and AI features spread across the market—and as “citizen developers” became a boardroom talking point—buyers increasingly expected tools that looked accessible, quick, and modern from day one.

That expectation cut both ways for Pega.

Because Pega’s real strength wasn’t that it was easy. It was that it was unified.

At its core, Pega was built as a single model-based development and runtime architecture: business rules, workflow, case management, decisioning and predictive analytics, data handling, integrations, UI, mobile support, monitoring, and governance—designed to work together rather than as a stitched-together stack. That architecture is exactly what makes Pega so powerful in large enterprises. It’s also what makes it feel heavy compared to platforms designed to help you stand up a departmental app in a week.

So the “low-code” label became both blessing and curse. It validated the direction Pega had taken for decades. But it also invited apples-to-oranges comparisons with simpler tools that could win deals on time-to-value, even if they couldn’t handle the messy edge cases that dominate real enterprise operations.

Pega’s response was not to try to be the simplest. It was to argue that “simple” breaks when the work gets real.

The company leaned into the idea that it wasn’t a low-code app builder. It was intelligent automation: digital process automation plus governance, security, orchestration, and AI-driven decisioning—all at enterprise scale. In customer reviews and analyst commentary, the pattern was consistent: Pega excelled when the use case was hard. Complex case management. Regulatory requirements. Deep integration with legacy systems. Omnichannel customer journeys where every exception matters.

And that’s where the market segmentation became clearer.

Pega wins when complexity is genuine—when a bank can’t “move fast and break things,” when an insurer’s claims process is a maze of policies and exceptions, when a healthcare workflow can’t afford ambiguity. In those environments, Pega’s sophistication is the product.

But the flip side is unavoidable: sophistication carries a cost.

Customers frequently called out the same drawback—Pega can be difficult to implement and hard for citizen developers to use. Compared with some competitors, it demanded specialized skills, longer training, and often a heavier reliance on systems integrators. Pega talent could be scarce and expensive, and some users felt partners and the community lagged in training and support for newly released functionality. For buyers looking for something lightweight, that complexity was disqualifying.

For others, it wasn’t.

In the Pega world, complexity isn’t a bug; it’s an admission of the domain. If your organization is already complex—and most Fortune 500 operations are—then the question isn’t whether the tool feels simple on day one. It’s whether it can run mission-critical processes for years, survive audits and upgrades, and adapt without becoming a spaghetti mess of custom code.

That’s the framing Pega tried to own. Not “we help you build apps.” More like: we help you run the business.

Even the head-to-head comparisons in the category, like Appian versus Pega, came down to that tradeoff. Both offered visual development with the option to drop into custom code. But they differed in target users, ideal use cases, technical requirements, and implementation complexity. In practice, the choice wasn’t really about who had the prettiest designer. It was about how much complexity you needed to absorb—and how much you were willing to pay, in time and expertise, to do it.

For investors watching the low-code wars unfold, the takeaway was simple: category labels matter less than the problems being solved. Pega might get grouped into “low-code,” “BPM,” or “CRM,” but its edge lived somewhere else. It won when the work was too complex for simpler tools—and as long as large enterprises kept living with regulatory pressure, legacy integration, and multi-channel customer demands, there would be plenty of that work to go around.

VII. The AI Vindication & Decisioning Renaissance (2020–Present)

When ChatGPT launched in late 2022, the business world talked about AI like it had just arrived. For Pegasystems, it felt like the rest of the industry finally showing up to a party Pega had been hosting for forty years.

That’s not marketing spin. Pega’s original 1983 insight was decisioning: teach computers to choose a next step the way a skilled human would. Rules engines, decision management, predictive analytics—these were practical AI long before “AI” became a boardroom word.

So when the generative AI wave hit, Pega’s move wasn’t to bolt a chatbot onto the product and call it innovation. In 2023, it rolled out Pega GenAI—about 20 generative AI “boosters” integrated across Pega Infinity, its core product portfolio. By the end of that year, Pegasystems generated $1.4 billion in sales.

Then came the product that made the strategy feel crisp: Pega GenAI Blueprint.

Pegasystems introduced Pega GenAI Blueprint as a collaborative app that combines generative AI with Pega’s industry best practices to speed up application design. The premise was simple: instead of generating more code, Blueprint generates a better starting point—a workflow design and decision logic that looks like it came from years of hard-won enterprise experience.

Describe what you want the application to do, and Blueprint proposes an optimized design. Not just a sketch, but the full shape of the system: stages and steps in the workflow, data models and objects, and user experiences for different personas. Under the hood, Pega GenAI—powered by Azure OpenAI—pulls from Pega’s repository of patterns developed across financial services, healthcare, government, telecom, and other heavily regulated, high-complexity industries.

The point wasn’t novelty. It was leverage. Historically, that early “design” phase is where big enterprise programs go to die: weeks of meetings, circular stakeholder debates, expensive consultant-led discovery. Blueprint was Pega saying: what if we compress that chaos into something usable on day one?

That idea landed. Since the tool went live in April 2024, more than 150,000 blueprints have been created. At its 2025 PegaWorld event, Pega showcased how its AI agent could shrink workflow design cycles from months to weeks, even when customers were dealing with outdated systems and massive technical debt.

A key detail here is what Pega chose to emphasize. Rather than blending design and development into a single “AI makes your app” promise, Pega treated design as its own discipline—and leaned into it. One observer framed the appeal this way: focusing on design plays to what Pega is already good at, and it delays the harder work of translating every nuance into production software automatically.

There was also a business-model rationale. If GenAI could reduce the consulting burden that made Pega implementations slow and expensive, customers would see a lower total cost of ownership—and Pega could expand faster with better margins. Services revenue might take a hit, but the software business would get stronger. And customers, who almost always want less professional services in the critical path, would benefit too.

Pega pushed further with a second smart wedge: legacy modernization.

Pegasystems announced AI-driven legacy discovery capabilities inside Pega GenAI Blueprint, aimed at modernizing old systems faster. The pitch was that IT teams could analyze existing systems in seconds, reimagine workflows, and reduce technical debt. It’s hard to find a more universal enterprise pain point than “we can’t move because the legacy stack is in the way,” and Pega aimed GenAI directly at it.

On the ecosystem front, Pega expanded GenAI to integrate with large language models from Amazon Web Services and Google Cloud in 2024. And in 2025, it released Pega Infinity ’25, the latest version of the Pega Infinity portfolio, continuing to push AI, low-code, and automation across products like Pega Cloud, Pega Platform, Pega Customer Decision Hub, Pega Customer Service, and Pega Sales Automation. The portfolio uses Constellation UX, including case management capabilities.

And then—finally—the numbers started to tell the story the market had missed during the transition years.

In fiscal year 2024, Pega reported revenue of $1.50 billion, up 5% year over year. Growth was driven by continued momentum in Pega Cloud, which delivered a 21% increase in annual contract value on a constant-currency basis.

By 2024, subscription services accounted for 86% of total revenue. Pega Cloud ACV reached $652 million, up 21% on a constant-currency basis. At the same time, maintenance revenue fell 10% and subscription license revenue fell 2% as customers continued shifting onto Pega Cloud—exactly the mix shift Pega had been enduring, and engineering toward, for years.

The profitability picture improved too. Gross profit rose 5% to $1.11 billion in 2024, and gross margin held steady at 74%, helped by improved cost efficiency in the cloud business. Net income increased 29% to $75 million, with an effective tax rate of 30%. Operating cash flow climbed 59% to $346 million, and the company used that cash to invest in the business, settle litigation, and return capital through repurchases and dividends. Free cash flow for the year was $338 million.

In 2025, the momentum continued. Management noted that 85% of new ACV was coming from Pega Cloud. Pegasystems reported Q3 CY2025 results that beat revenue expectations, with sales up 17.3% year over year to $381.4 million, and non-GAAP profit of $0.30 per share, well ahead of consensus estimates.

The stock reflected the shift, too. After falling during the cloud transition, it recovered as investors started pricing in what the fundamentals were showing: cloud mix, improving margins, and an AI story that wasn’t a pivot—it was a continuation.

“Pega GenAI Blueprint is creating enormous excitement and fundamentally changing how we engage with our clients,” Alan Trefler said.

For a founder still in the CEO seat after more than four decades, this was the rare tech moment that reads like closure. The vision Trefler articulated in 1983—software that can express business logic clearly and make intelligent decisions—wasn’t being replaced by AI. It was being amplified by it. Pega wasn’t chasing the AI era. The AI era was catching up to Pega.

VIII. Leadership & Culture: The Alan Trefler Factor

Very few technology companies of real scale are still run by their founders four decades in. The list is tiny—Oracle’s Larry Ellison is an obvious comparison, though the governance realities are very different. At Pegasystems, Alan Trefler isn’t just the founder. He’s the gravitational center of the company’s strategy, culture, and time horizon.

Trefler founded Pegasystems on April 1, 1983, and has served as its CEO since its inception. By 2023, that meant four decades at the helm—an almost unheard-of tenure in public-company tech.

Control matters here, not as trivia, but as strategy. With a 52 percent ownership stake in Pegasystems, Trefler’s net worth surpassed $1 billion in 2013, and he appeared on the Forbes Billionaires List for the first time in March 2017. More importantly, that majority ownership changes what’s possible. He can’t be forced out by activist investors. He can’t be cornered into managing to the quarter. And he can make multi-year bets that would be nearly impossible for a hired CEO whose job security depends on short-term optics.

If you want a case study, look at the cloud transition. Pega spent years absorbing ugly near-term numbers so it could rebuild its business model for a subscription world. Under different governance, that kind of self-cannibalization often gets delayed, watered down, or abandoned. Under Trefler, it happened—painfully, publicly, and on a timeline measured in years, not earnings calls.

That same control also shapes how Pega thinks about independence. As majority shareholder, Trefler can simply refuse to sell. “BPM, this whole technology that we are in, is way too young to be bought by the bone collectors. It’s just too early,” he has said.

“Bone collectors” is Trefler’s term for buyers—private equity or strategics—who acquire companies primarily to cut costs rather than push innovation. His resistance to that outcome shows up in the operating posture: heavy R&D investment, a preference for building long-term capability instead of maximizing near-term profitability, and an insistence that Pega’s best years should be ahead, not monetized in an exit.

But founder gravity has a downside: it can be hard to tell where the founder ends and the company begins. To many people, Trefler and Pegasystems are synonymous, and that can become limiting at scale. “Pega is still very much Alan’s baby, and he treats it as such. He needs to step back,” one former employee told Computer Weekly.

It’s a familiar critique, and it’s not frivolous. Founder-led companies can struggle with succession. They can calcify. They can overfit to one person’s instincts—even when those instincts built the company in the first place. And whether it happens in five years or fifteen, Pega will eventually face the hardest transition of all: leadership beyond Alan.

There are signals that Pega is building bench strength. Kenneth Stillwell joined as chief financial officer in 2016 and was promoted to chief operating officer in 2023, overseeing operations, finance, and administrative functions, and bringing more than 20 years of experience across high-growth tech firms. Stillwell’s expanded remit suggests that succession planning is at least being taken seriously. But investors will watch this closely: founder transitions are among the highest-risk events in public markets, and Pega’s will be no exception.

Trefler’s leadership style is unusually consistent with his background. In 2014, he authored the book Build for Change, about adapting to shifting consumer markets. The title is basically Pega’s product philosophy in four words: software should make change easier, not trap companies in rigid processes.

People who’ve worked with him describe a leader who treats business like strategy, not improvisation. “He reads his briefs and prepares thoroughly. He doesn’t fly by the seat of his pants,” one co-worker said. That’s the chess player showing up: systematic, prepared, thinking several moves ahead.

And there’s another dimension that doesn’t usually make it into enterprise software stories: philanthropy. Trefler and his wife donated $1 million to Dorchester High School in Dorchester, Boston in 1995. They established The Trefler Foundation in 1997, which seeks to improve urban public education in the Boston area. Whatever you make of it, it reinforces the broader pattern: Trefler builds for the long term, and he seems comfortable investing in outcomes that take years to show up.

For investors, the “Trefler factor” is a double-edged advantage. On one side: aligned incentives, deep expertise, and the freedom to play a multi-decade game. On the other: concentration of decision-making, key-person risk, and the unavoidable question of what Pegasystems looks like when Alan Trefler is no longer in the CEO chair.

As Pega enters its next phase, that tension won’t fade. It will matter more.

IX. Business Model & Economics Deep Dive

To really understand Pega’s business, you have to do two things at once: follow the twists of enterprise software revenue accounting, and then deliberately look past them to see what’s actually happening underneath.

By 2024, subscription services made up 86% of Pega’s revenue. That’s the end state of the long, painful cloud transition: what used to be a perpetual-license machine is now, overwhelmingly, a recurring subscription business.

Under that subscription-heavy umbrella, Pega still makes money in a few different ways: Pega Cloud (its SaaS offering), term licenses (software delivered on-prem but paid over time), maintenance on older perpetual licenses, and professional services. They don’t all behave the same. Some are predictable and compounding, some are in managed decline, and some exist because the product is powerful enough that customers often need help getting it right.

The clearest engine is Pega Cloud. In 2024, Pega Cloud annual contract value grew 21% on a constant-currency basis to $652 million. And as you’d expect in a conversion story, that growth came alongside declines elsewhere: maintenance revenue fell 10%, and subscription license revenue fell 2%, as more customers moved onto Pega Cloud.

The pattern here is the one you want if you believe in the long game. Cloud becomes the growth flywheel. Maintenance shrinks as the installed base migrates. And even if the transition can make reported revenue look weird quarter to quarter, the business gets cleaner and more durable as the mix shifts.

Profitability tells the same story. In 2024, gross profit rose 5% to $1.11 billion, and gross margin held at 74%. That’s not “pure SaaS at 85%+” territory, but it’s still firmly enterprise-software strong—especially for a company that runs real cloud infrastructure and supports large, demanding deployments.

Cash flow is where Pega really starts to feel like a mature, disciplined enterprise franchise. The company generated $343 million in cash from operations, funding continued investment across R&D and go-to-market. It ended the year with $1.23 billion in cash and investments and no debt. That’s a very specific posture: conservative, durable, and built to survive long transitions without needing capital markets to cooperate.

That conservatism also fits the Trefler blueprint. Cash-rich, debt-free, reinvesting—less “financial engineering,” more “make sure we’re still here and still relevant ten years from now.”

The customer economics are the hidden superpower. As Pega puts it: JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo have been customers for 37 years. The company has rewritten its technology multiple times, and those customers stayed through the rewrites because they kept getting ROI. That’s what switching costs look like in the real world: not just “hard to replace,” but “why would we replace it when it keeps paying us back?”

And once you accept that reality—implementations that can cost millions, processes that become mission-critical, institutional knowledge embedded in the platform—retention stops being a nice metric and becomes the core economic engine. Rational customers don’t rip this out. They expand. They add more workflows. They move more interactions onto the platform.

On market size, Pegasystems believes its combined opportunity across CRM and BPM is about $80 billion—implying the company is still at roughly low-single-digit penetration. That’s the optimistic framing. The more sober version is that not every process at every enterprise is a fit for Pega’s depth and complexity. So the real growth question becomes: how much can Pega expand inside its installed base, and how many new large customers can it win where the work is truly complex?

Pricing reinforces that segmentation. Pega’s tiers can start at $97 per user per month, but the sticker price is only part of the story. Because the platform is sophisticated, implementation and customization typically require a real technical team—either in-house or through partners—so total cost of ownership is meaningfully higher than lighter-weight tools.

Pega also offers pricing that starts around $35 per user per month or $0.45 per case, with minimum commitments like at least 500 named users or 350,000 annual cases. That makes the product a tough fit for small teams or casual use cases. It’s designed for big, sustained workloads—exactly where Pega’s economics make sense.

One important evolution is the shift toward usage-based pricing: charging based on work processed rather than purely per-seat licensing. The logic is clean. It aligns incentives. Customers pay more when they run more real work through the platform, and Pega benefits when adoption turns into throughput, not shelfware. Management views this as structurally ahead of competitors still anchored to seat-based models.

For investors, the “watch list” is simpler than the accounting makes it look. Track ACV growth—especially Pega Cloud ACV. Watch net revenue retention to see whether customers are expanding. And keep an eye on new logo acquisition to measure whether Pega is winning fresh footprints, not just deepening old ones. Those metrics tell you whether Pega is actually gaining share in complex enterprise automation—regardless of how revenue recognition can distort the headline numbers along the way.

X. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

To understand where Pega really sits in the enterprise software landscape, it helps to look at it two ways at once: the classic industry forces pushing on everyone, and the specific moats that explain why Pega can stay so deeply embedded once it wins.

Competitive Rivalry: High

Pega lives in the most competitive neighborhoods of enterprise software: CRM, BPM/case management, workflow automation, and the ever-expanding “low-code” universe. Salesforce dominates CRM. Appian is a frequent head-to-head in BPM and case management. ServiceNow comes at the problem from workflow automation and IT service management, but keeps expanding outward. Microsoft attacks from two angles at once: Power Platform for low-code, and Dynamics 365 for CRM and customer service.

It’s a fragmented, constantly shifting battlefield. Vendors blur category lines, ship overlapping features, and market hard. The pressure toward feature parity never stops. Pega’s defense is depth: it’s built for the use cases that get messy fast. That’s a defensible position—but it’s also one that’s harder to scale in a world that rewards fast, easy adoption.

Threat of New Entrants: Medium-High

Low-code lowers the barrier to building basic automations, and cloud infrastructure has commoditized what used to require massive upfront investment. But what Pega does best—deep integration into core systems, complex rules, regulated workflows, and long-lived processes—is still difficult to replicate. Generative AI could lower barriers further, though it could just as easily favor incumbents that already have mature platforms and decades of implementation patterns.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low

Infrastructure is effectively a commodity across AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud, and Pega has certified its platform across the major providers. On the services side, the bench is broad: Accenture, Deloitte, Cognizant, TCS, and Wipro all run Pega practices, among many others. No single supplier holds meaningful pricing power over the company.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Medium-High

Pega sells to large enterprises with real negotiating leverage. Procurement teams push hard on price and terms, especially on the first deal. But once Pega is implemented, the leverage shifts. Switching costs are enormous: multi-year programs, millions invested, and institutional knowledge encoded into configurations. Closing the deal requires negotiation; keeping the relationship usually isn’t a knife fight, because the platform has become part of how the business runs.

Threat of Substitutes: Medium-High

There’s no shortage of point solutions: chatbots, RPA tools, standalone workflow products. And for big enterprises with strong engineering teams, “build vs. buy” is always on the table. But when the requirement is end-to-end, cross-channel, highly governed automation, substitutes get harder. Stitching together point tools pushes the integration burden—and the operational risk—back onto the customer.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

1. Scale Economies: Medium

As Pega Cloud grows, infrastructure and operating costs spread across a larger base, improving margins over time. But this isn’t a consumer platform where scale automatically makes the product better.

2. Network Effects: Low-Medium

The ecosystem provides some lift: more trained consultants, more reusable implementation patterns, more shared expertise. But it’s not a viral, user-to-user network effect that creates runaway dominance.

3. Counter-Positioning: Medium-High

This is one of Pega’s underrated advantages. Salesforce and ServiceNow could pursue Pega-level depth in decisioning and complex workflow—but doing so risks complicating, and potentially cannibalizing, the simpler, higher-volume offerings that power their scale. Meanwhile, many low-code platforms could try to move upmarket into heavier enterprise complexity, but that would undermine the “easy and fast” story that wins them deals. Pega’s position is attackable in theory, but awkward to attack in practice.

4. Switching Costs: HIGH ⭐ Primary Power

As Pega puts it: JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo have been customers for 37 years of this journey. One of the unique things about Pega is that when companies come on board, they tend to stay. They have been getting value for over three decades.

This is the core moat. Implementations can run 12–24 months. Mission-critical processes end up living on the platform. Institutional knowledge becomes configuration. Replacing Pega isn’t a software swap; it’s a multi-year business transformation with serious risk and cost. Once embedded, customers rarely leave—they expand.

5. Branding: Medium

Among enterprise buyers, Pega’s reputation is strong, reinforced by consistent leadership positioning from firms like Gartner and Forrester. But it lacks the broad awareness of a Salesforce. Being the “best-kept secret” helps credibility with insiders, but it limits mindshare outside those circles.

6. Cornered Resource: Medium-High

Pega brings four decades of intellectual property in rules engines and AI decisioning. Trefler’s vision and relationships have also been uniquely durable. But the company isn’t protected by a monopoly on talent; engineers and product leaders are sourced from competitive labor markets like everyone else.

7. Process Power: High

Pega has decades of hard-earned implementation methodology, and a partner ecosystem trained on how to deliver Pega successfully. Its center-out architecture and design patterns create repeatability in environments where most enterprise software projects devolve into one-off chaos. That “how we do this” institutional knowledge is a real advantage.

Verdict: Pega’s moat is primarily switching costs plus process power in complex enterprise environments. It’s more exposed in simpler use cases where the work isn’t deeply embedded and alternatives can be swapped in. But where complexity is real, Pega is built to stick.

XI. The Appian Litigation: A Legal Cloud with Resolution

No discussion of Pegasystems is complete without the elephant in the room: the Appian lawsuit—an explosive courtroom fight that, for a moment, produced the largest verdict in Virginia court history before the decision was overturned on appeal.

Appian and Pegasystems have been longtime rivals in high-end process automation. On May 9, 2022, a Virginia jury unanimously found that Pega violated the Virginia Computer Crimes Act by infiltrating Appian, and also unanimously found that Pega misappropriated Appian trade secrets. The jury and judge described Pega’s conduct as “willful and malicious.” Damages were set at $2.036 billion—at the time, the biggest damages verdict Virginia had ever seen, according to the Court of Appeals of Virginia.

The allegations themselves were stark. Appian claimed Pega began infiltrating Appian in 2012, when Pega was more than ten times Appian’s size. Appian alleged Pega lost access to its “spy” in 2014, then in 2017 used false identities to regain access to Appian information. Appian further alleged that even after it discovered the infiltration and filed suit in 2020, Pega continued the activity into 2021.

Pega maintained throughout that the verdict was unjust. It argued the trial was riddled with errors, including limits on Pega’s ability to defend itself on key issues, and that the resulting award was wildly disproportionate.

Then came the reversal. On July 30, 2024, the Virginia Court of Appeals—Virginia’s intermediate appellate court—vacated the $2 billion award tied to the “willful and malicious” misappropriation findings, based on rulings by the trial court judge that the Court of Appeals did not agree with. The Court of Appeals sent the case back to the trial court for a new trial. Appian petitioned the Supreme Court of Virginia for review, and on March 7, 2025, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

That March 2025 decision matters for another reason, too: the Supreme Court of Virginia also agreed to hear Pega’s arguments for why the case should be dismissed entirely.

A key issue in the appellate decision was how the jury was instructed on damages causation. The Court of Appeals found that the trial court improperly instructed the jury on Appian’s burden to prove that the alleged misappropriation caused damages. In effect, the instruction allowed a presumption that Appian’s trade secrets were the but-for cause of all of Pega’s sales—even including product lines that did not use information associated with Appian’s claimed trade secrets. By letting Appian use all of Pega’s sales to calculate damages, the instruction severed the causation link between specific sales and the alleged misconduct.

So the legal saga wasn’t over—but the shape of the risk changed. The $2 billion judgment that once hung over Pegasystems had been vacated, even as the ultimate resolution moved to Virginia’s highest court.

For investors, the case is both a cautionary tale and a reminder of how much headline risk can matter in enterprise software. Whatever the final outcome, the litigation is likely to clarify Pega’s liability exposure—and, just as importantly, remove a long-running source of uncertainty that has periodically weighed on the stock.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case & Future Outlook

The Bull Case:

The cloud transition is done—and what created years of noisy, confusing financials has flipped into an advantage. By 2024, subscription services made up 86% of total revenue. Pega is now a much more predictable, recurring business than it was in the perpetual-license era.

AI also lands in Pega’s sweet spot. Decisioning engines, rules automation, and workflow optimization are the company’s original DNA. Generative AI doesn’t replace that; it accelerates it. Tools like GenAI Blueprint can compress the front end of big implementation programs, potentially shrinking timelines and making Pega practical in more situations than the old “multi-year transformation” stereotype.

Then there’s the installed base—Pega’s quiet superpower. Many leading global enterprises use Pegasystems, including seven of the top ten U.S. banks, seven of the top ten asset managers, seven of the top ten U.S. health plans, five of the top ten U.S. insurers, four of the top five U.S. telcos, the five largest pharmaceutical companies, and more than 30 major federal agencies. In a business where switching costs are enormous, that footprint isn’t just a customer list—it’s a runway. Most customers still use Pega for only a slice of what they could run on it.

Financial discipline is tightening, too. In 2024, cash flow from operations grew 59% to $346 million, giving Pega room to keep investing, settle litigation, and return capital through repurchases and dividends. That’s the kind of profile investors tend to reward once the story shifts from “transition” to “durable compounding.”

And finally: valuation. Pega has often traded at a discount to enterprise software giants like Salesforce and ServiceNow. If the market’s skepticism was rooted in the cloud transition and a “legacy vendor” narrative, that discount may not hold if Pega keeps proving the new model works.

The Bear Case:

Pega’s growth profile is still slower than the market’s favorite SaaS names. Mid-single-digit to low-double-digit growth can be a tough sell in a world where faster-growing competitors often command the premium multiples. Even if Pega is executing, the market may simply keep paying up for speed elsewhere.

Customer feedback also points to the same recurring friction: complexity. Compared with some competitors, Pega can feel less accessible to citizen developers and more dependent on systems integrators and specialized Pega talent. Successful deployments often require experienced teams, and that means hiring, training, and retention become part of the product cost. For some organizations, that’s manageable; for others, it’s a deal-breaker.

That implementation burden also caps the addressable market. Plenty of enterprises will choose simpler tools that do less, faster—even if they can’t match Pega’s depth. The practical market may be smaller than headline TAM estimates suggest.

Founder-CEO risk is another overhang. Trefler is 68 years old. Succession planning appears to be underway, but it hasn’t been tested, and Pega’s culture and long-term posture have been closely tied to one person for decades.

Cost can be a barrier too, especially outside the Fortune 500. Licensing is only one part of the bill; implementation and ongoing support can add up quickly, making the ROI harder to justify for smaller and mid-sized companies.

And Microsoft bundling remains the ever-present threat. As Power Platform continues to improve and gets bundled into Office 365, many enterprises may default to “good enough” Microsoft tooling rather than committing to a best-of-breed Pega deployment.

Key Metrics to Watch:

Two KPIs matter most for tracking whether Pega’s next chapter is working:

-

Pega Cloud ACV Growth: This is the engine. Sustained growth above roughly the mid-teens signals healthy demand; a drop into the low double-digits, or below, would raise questions.

-

Net Revenue Retention: This is the proof that customers are expanding, not just renewing. Above 110% suggests the installed base is widening its Pega footprint; below 100% points to churn pressure.

These are the numbers that cut through the noise. Revenue can get distorted by mix shifts and accounting. ACV and retention tell you what’s really happening underneath—quarter after quarter.

XIII. Epilogue & Reflections

The Pegasystems story doesn’t fit the usual startup script. There was no venture-fueled rocket ship, no blitzscaling phase, no founder cash-out a decade in. Instead, there was a stubbornly consistent arc: more than four decades of patient building, under one leader’s vision, aimed at the hardest enterprise problems.

That’s the paradox at Pega’s core: technically excellent, commercially under-appreciated. The company shows up near the top of analyst rankings for capability, then disappears from the broader conversation next to competitors with louder brands and bigger marketing machines. It’s the Rolls-Royce of business process automation—exceptional for the organizations that need it, almost invisible to the ones that don’t.

There are clear lessons here for founders. Patient capital buys you the right to make long-term bets. Technical depth can create moats that look boring from the outside but become nearly unassailable once they’re embedded. And if you want to survive the real history of enterprise computing—mainframe to client-server to web to cloud to AI—you have to keep reinventing delivery and business model without abandoning the core strengths that made you valuable in the first place.

There are lessons for investors, too. Inflection points don’t always show up neatly in quarterly results. Cloud transitions take four to five years, not four to five quarters. And switching costs might be the most powerful moat in enterprise software—but they require a different kind of patience, because the proof doesn’t arrive as a viral adoption curve. It arrives as a customer relationship that quietly lasts for decades.

The bigger takeaway is what this story says about enterprise software itself. It’s not built on network effects or consumer-style virality. It’s built on solving complex problems deeply, earning trust over years, and winning renewals because the software is genuinely running the business. Pega’s approach is unfashionable in a world that rewards flash. But it works.

And the open questions that define the next chapter are still there. Can Pega expand meaningfully beyond the Fortune 500? What happens when Alan Trefler eventually steps back? Does generative AI commoditize what Pega does—or does it amplify Pega’s advantage by making its power easier and faster to deploy?

The endgame isn’t written. Pega could remain independent for a long time under founder control. It could become attractive to a larger platform that wants enterprise automation and decisioning at scale. Or it could use AI to compress implementation friction and unlock a wider slice of the market than it historically could reach.

What does seem clear is this: after more than 40 years, Pegasystems has proven it can survive the transitions that wipe out most companies. The firm that set out to teach computers to make decisions—methodically, strategically, planning several moves ahead—has been playing a longer game than most observers ever noticed.

In a world of hype cycles and overnight unicorns, Pega is the tortoise that keeps moving—steady enough that people forget the race is even happening, until they look up and realize who’s still standing.

XIV. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper on Pega—and separate what’s changing in the business from what’s merely changing in the accounting—these are the sources that give you the clearest picture.

Primary Sources: - Pegasystems Annual Reports and 10-K filings (SEC EDGAR) – The most complete record of the cloud transition, told in management’s own words - Quarterly earnings call transcripts (2023-2025) – Where the AI strategy, go-to-market shifts, and metric choices show up without the marketing gloss - PegaWorld annual conference presentations – A direct look at the product roadmap and how customers describe real deployments

Analyst Perspectives: - Forrester Wave Reports for Low-Code Development Platforms – Useful for understanding how Pega stacks up in execution and why it often wins the hard use cases - Gartner Magic Quadrants for Intelligent Business Process Management – Category context and peer comparison, especially around automation and case management

Historical Context: - Alan Trefler's book "Build for Change" (2014) – The founder’s philosophy, and a surprisingly good lens on why Pega keeps betting on adaptability - Computer Weekly feature "How Pegasystems is capturing the Fortune 500" – Helpful background on how Pega built its footprint long before it became fashionable

Technical Understanding: - Pega Platform documentation and architecture briefs – The best way to understand what “model-driven” actually means in practice, and why it creates both power and complexity - Pega Academy training materials – A window into the implementation reality: what teams have to learn, and why the ecosystem matters

The Pegasystems story is still being written. But if you’re willing to look past quarterly noise and follow the underlying signals—cloud adoption, customer expansion, and the pace of AI-assisted implementation—there’s a lot here that applies to far more than one company or one market cycle.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music