Pitney Bowes: From Postage Meter Monopoly to Digital Survival

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

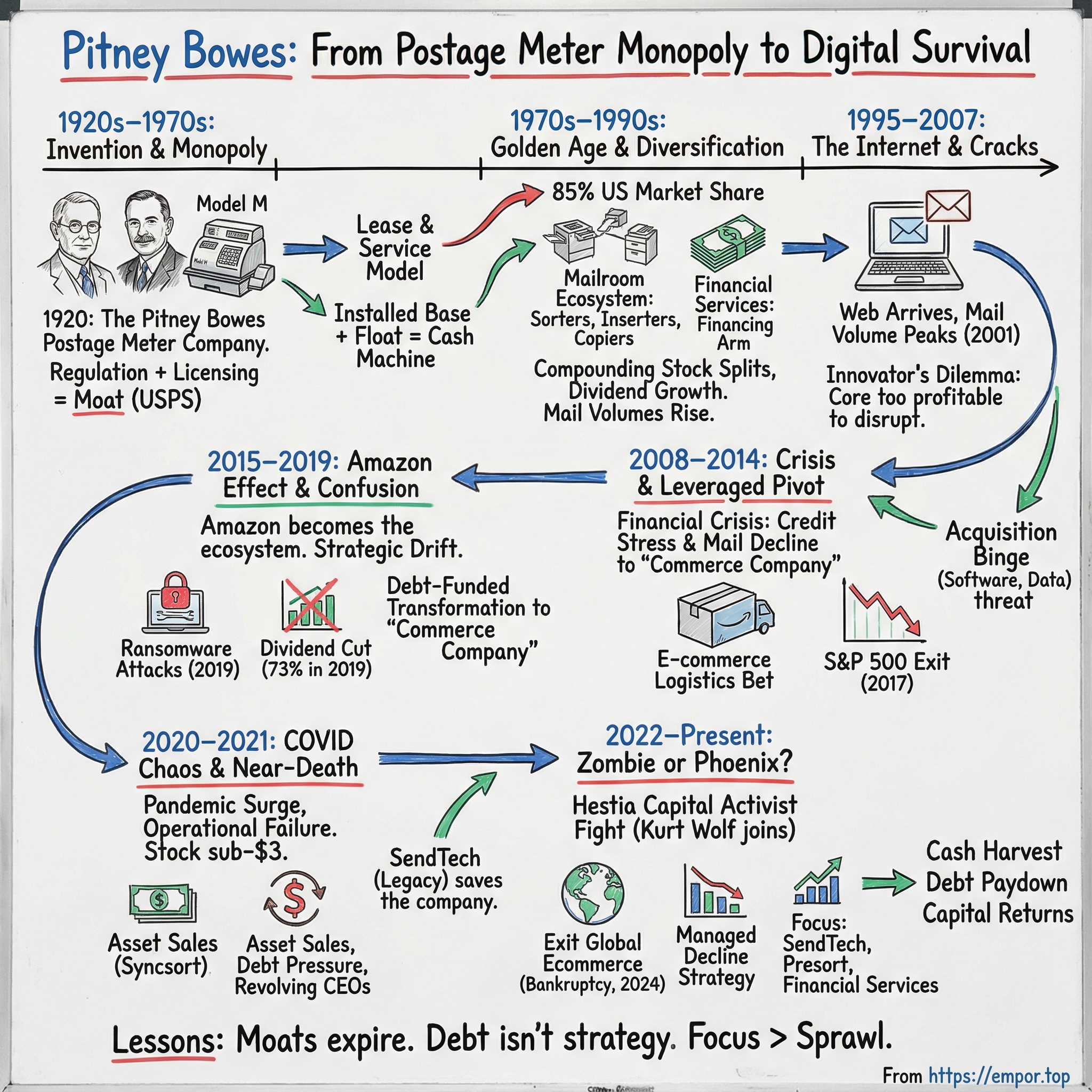

What do you get when a 104-year-old postage meter monopoly meets the internet age?

Picture the scene. It’s 1999, and Pitney Bowes is at an all-time high, trading around $65 a share. For nearly eight decades, it has dominated postage meters—owning and leasing roughly 85 percent of America’s 1.5 million machines. Fortune 500 mailrooms run on its equipment. The revenue is recurring, the customers are locked in, and the dividend has been raised for years. Wall Street can’t get enough of this boring, beautiful monopoly.

Now jump to December 2025. In 2024, Pitney Bowes generated about $2.0 billion in revenue and $500 million in EBITDA, serving more than 600,000 clients worldwide. The stock trades around $10. The company has exited its e-commerce logistics business through bankruptcy. Headcount has shrunk dramatically too: by December 2024, Pitney Bowes employed roughly 7,200 people, about 78% in the U.S.—down from about 10,500 a year earlier. And in the ultimate late-stage twist, an activist investor who once stormed the boardroom now sits in the CEO chair.

That’s the arc we’re unpacking: one of the cleanest case studies of what happens when a regulatory moat starts to erode, when technology eats the category that made you rich, and when financial engineering can paper over strategic problems—until it can’t. This is the innovator’s dilemma playing out in slow motion over decades. It’s acquisition binges that destroy value. It’s a dividend policy that keeps the optics intact while the foundation cracks. And it’s the sheer difficulty of turning a hardware rental machine into a digital-era company.

But it’s also a story about survival. Despite the steady decline of mail, the cyberattacks, the near-death moments, and the activist fights, Pitney Bowes is still here—still headquartered in Stamford, Connecticut, still employing thousands.

The central tension: how does a company built on regulatory permissions and leased machines adapt when email replaces letters—and when Amazon decides it doesn’t need middlemen to move packages? The answer is a playbook, and a warning, about competitive advantages, their expiration dates, and the difference between reinvention and managed decline.

II. The Invention & Early Monopoly (1920–1970s)

The invention that would eventually power one of America’s most profitable, boring monopolies didn’t start in a lab or a boardroom. It started in a wallpaper store in Chicago.

In 1901, Arthur Pitney was working as a clerk when he began tinkering with a better way to mail. His early postage machine was a decidedly mechanical contraption—manual crank, chain action, printing die, counter, and a lockout device—but the idea behind it was clean and modern: print postage directly onto an envelope, track exactly how much had been dispensed, and eliminate the messy, fraud-prone world of licking stamps and handling cash.

Pitney filed a patent application in Stamford, Connecticut on December 9, 1901. But an invention isn’t a business. And a business that depends on the U.S. government changing how it collects revenue is a special kind of hard. For the next two decades, Pitney pushed uphill against bureaucratic inertia, congressional skepticism, and a Post Office that didn’t love the idea of a private company sitting in the middle of its money flows.

Adoption was slow. Pitney’s finances—and even his marriage—were battered by the project. At one point he sold insurance to keep going. That detail matters, because Pitney wasn’t improving an existing process. He was trying to create an entirely new category and persuade the Postal Service to bless it.

The break came in 1919, when Pitney was introduced to Walter Bowes. Bowes was an industrialist who’d already had success marketing a stamp-canceling machine to the Post Office. Where Pitney was the inventor, Bowes was the operator: commercially sharp, politically connected, and comfortable turning a clever mechanism into a scaled enterprise. A Post Office Department official—seeing that the two products could complement each other—made the introduction.

On April 23, 1920, the pair formed the Pitney Bowes Postage Meter Company. And almost immediately, the pieces clicked into place. The very next day, they helped push legislation through Congress that allowed all classes of mail to be posted by meters instead of stamps, and the Pitney-Bowes meter was licensed for use throughout the postal system.

That one-two punch—legal permission plus official licensing—became the bedrock of the Pitney Bowes moat.

The Model M became the cornerstone product, officially recognized by the U.S. Postal Service and introduced on November 16, 1920. Years later, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers would designate the Model M an International Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark, the kind of honor reserved for inventions that genuinely changed how the world works.

From there, the company expanded quickly off a small base. By 1922, Pitney Bowes had branch offices in 12 cities and 404 meters in operation. It also moved fast internationally: manufacturing was established in Stamford, and the meter gained approval for use in Canada and England.

But the founder story didn’t resolve into a tidy partnership. In 1924, Arthur Pitney retired after a dispute with Bowes and went on to start a competing company making postage-permit machines. It could have been the kind of founder rupture that derails a young business. Instead, Bowes’s stepson, Walter Wheeler II, stepped into leadership and went on to guide the company for decades.

Regulation, meanwhile, was both the rocket fuel and the handcuffs. In many quarters, it was assumed Pitney Bowes had a government-created monopoly. That perception triggered pushback. In its first decade, government regulation—encouraged by competitors—limited Pitney Bowes’ scope and restrained how aggressively it could exploit its technological lead. Even the Post Office was ambivalent, wary of appearing to hand a private company a license to print money.

Still, the meters spread. By the end of 1933, there were 9,620 Pitney Bowes meters in service. Even the Great Depression couldn’t kill the underlying logic of the product. Pitney Bowes retrenched like everyone else, and profits shrank considerably, but it didn’t face critical financial difficulty. It was, almost unfairly, on the right side of a long-term operational trend: businesses were mailing more, not less—and they wanted to do it faster and with less friction.

World War II and the postwar boom poured gasoline on adoption. By the end of 1946, nearly half of Pitney Bowes’ employees were World War II veterans. And as business correspondence surged, meters became a staple of the modern office. By the end of 1947, the number of meters in service had more than doubled in less than a decade, rising to over 60,000.

With dominance came scrutiny. By 1957, domestic competition had virtually disappeared—and the government came knocking with antitrust action. The resolution is one of those details that tells you what the moat really was: Pitney Bowes agreed to a consent decree requiring it to license its patents to any manufacturer who wanted to compete, at no charge. The patents were opened up, and competitors still struggled to gain traction. The advantage wasn’t just intellectual property. It was the installed base, the service network, the customer relationships, and the switching costs baked into the leasing model.

By 1960, when Walter H. Wheeler retired as president and chief operating officer, Pitney Bowes had 281,100 meters in service. Metered mail accounted for 43 percent of U.S. postage. Nearly half of the country’s postage revenue was literally being processed through Pitney Bowes equipment.

The business model that emerged was as elegant as it was relentless. Meters weren’t sold—they were leased. Customers paid recurring fees for the machine, mandatory maintenance, and consumables. Pitney Bowes held postage deposits, earning float. And when postage rates went up, the system kept humming and the economics improved without the company having to reinvent anything.

It was one of the cleanest cash machines in American corporate history.

And that’s why this origin story matters. Pitney Bowes didn’t just build a product. It built a regulatory relationship, a physical installed base, and an operational service footprint that became the business. When your edge comes from permissions, infrastructure, and habit, you don’t get to simply “pivot” when the world goes digital. You have to unwind—and rebuild—while the old machine is still paying the bills.

III. The Golden Age: Diversification & Dominance (1970s–1990s)

By the 1970s, Pitney Bowes had achieved something rare in American capitalism: dominance so complete it felt permanent.

In the U.S., it controlled about 85% of the postage meter market. Worldwide, about 60%. Those aren’t “we’re doing well” numbers. Those are “this is basically a utility” numbers—share levels you only get when regulation, distribution, and customer inertia all point in the same direction.

So the playbook in this era was simple: protect and milk the core, then expand outward into the rest of the mailroom. If you already had the relationship, the service techs, the contracts, and the billing cadence, why stop at the meter?

Pitney Bowes pushed into the broader “mailroom ecosystem.” It launched early versions of automatic mail sorting equipment in 1957, introduced mail inserters in 1961, and kept layering in adjacent tools designed to make high-volume mailing faster and cheaper. Over time, Pitney Bowes became a one-stop shop: scales, folders, inserters, sorters—and yes, even copiers and fax machines for a period, a business it would eventually spin off in 2001 as Imagistics International.

Then came the other brilliant extension: financing. In the late 1970s, Pitney Bowes built a financial services arm that started as a way to support customers leasing meters, and expanded into financing equipment purchases more broadly. This wasn’t just a helpful add-on. It let Pitney Bowes capture more of the total economics of each customer: manufacturing margin, lease revenue, service and maintenance, supplies, and then the financing spread on top.

By the 1980s into the mid-to-late 1990s, this machine was at full speed. From 1983 to 1998, Pitney Bowes split its stock four times. In that era, stock splits were corporate swagger—management’s way of saying, “We think this compounding story keeps going.” And for a long stretch, it did. Mail volumes rose. New businesses opened and mailed invoices and statements. The dividend increased steadily. The whole system reinforced itself.

The culture matched the business. This wasn’t a Silicon Valley company chasing disruption. It was a Stamford, Connecticut institution: conservative management, serious engineering, and a sales force with deep, multi-generational customer relationships. It was built to execute, to service, to renew contracts—not to imagine a world where the mailroom shrank.

To be fair, Pitney Bowes wasn’t asleep at the wheel. In 1978, it introduced “Postage by Phone,” letting customers refill postage remotely and reducing the need for post office visits. That’s real innovation. But it was innovation that made the existing model more convenient and more sticky. It wasn’t a bet on a different future.

And the economics were exactly what Wall Street loves: high gross margins on equipment, recurring revenue from leases and maintenance, captive customers with real switching costs, plus float on postage deposits. Underneath it all was the great tailwind of the 20th-century office: business mail that just kept growing.

At one point, postage paid on metered mail hit an all-time high of about $500 million—around 36% of all USPS postal revenues. Pitney Bowes wasn’t just important to corporate America. It was structurally important to the Postal Service. That kind of mutual dependence doesn’t just create revenue; it creates confidence.

But every golden age hides a trap. The very things that made Pitney Bowes so formidable—regulatory relationships, a massive installed base, the lease-only model, and decades of optimizing for growing mail volumes—also made it harder to adapt if the world ever moved on.

And that’s the tell. When a company owns 85% of its market and seems invulnerable, the real question isn’t whether competitors will appear. It’s whether the underlying market will change. Pitney Bowes had engineered itself for a world where mail only went up and to the right. It just hadn’t built itself for what would happen when that assumption stopped being true.

IV. The Internet Arrives: First Cracks in the Foundation (1995–2007)

The first email sent on ARPANET in 1971 didn’t matter to Pitney Bowes. Neither did the early commercial email systems of the 1980s. But by the mid-1990s—when the web went mainstream and email started showing up on every desk—the threat wasn’t theoretical anymore. If communication could move at the speed of software, what happened to a company built on ink, metal, and the U.S. Postal Service?

In June 1999, Pitney Bowes stock traded around $65 a share. The market was pricing in a simple story: mail keeps growing, the monopoly keeps humming, and this steady cash machine keeps compounding. In hindsight, it was the last moment of innocence.

Pitney Bowes didn’t ignore the internet. It did what great incumbents often do: it responded with smart, incremental upgrades that fit neatly inside the existing worldview. In 1996, it launched a line of credit for postage. In 1998, it introduced D3 software, designed to manage messages across email, fax, hard copy, and the web. Reasonable moves—modern touches for a modern office.

But they missed the core point. Email didn’t need to be organized alongside fax and paper. Email was going to replace them.

As that reality crept in, the company’s identity started to slide. Pitney Bowes was no longer “a postage meter company.” It was “a communications company,” later “a commerce company.” The shifting labels weren’t a sign of reinvention; they were a sign of uncertainty. When you have to keep renaming what you are, it’s often because you don’t yet know what you’re becoming.

So Pitney Bowes did the other thing incumbents do when the ground starts moving: it bought. Starting in 2001, the acquisition engine spun up, with the company spending about $1 billion on deals. The logic was defensive and understandable: if the core is heading into decline, buy exposure to whatever might grow next.

In 2001, Pitney Bowes bought Bell & Howell’s international Mail and Messaging Technologies business. In 2002, it acquired PSI Group, a mail presorting company in Omaha, for $130 million. In 2004, it bought Group 1 Software, a mailing technology company based in Lanham, Maryland, for $380 million.

Each deal made sense on its own. Put together, they tell a more sobering story: Pitney Bowes was assembling adjacent pieces in the hope that the sum would outpace the decline of the thing it actually was.

And here’s why that was so hard. The core postage meter business was still extremely profitable. This was the innovator’s dilemma in its purest form: the legacy product kept producing so much cash that almost any digital alternative looked worse in the near term. Why take a painful leap into uncertain software and services when the meters were still printing money—almost literally?

But the underlying market was already turning. First-Class mail volume peaked around 2001 and then began a decline that wouldn’t reverse. Bill payment moved online. Business correspondence went digital. Younger workers didn’t grow up with stamps as a default. Even the fax machine—another product category Pitney Bowes played in—was sliding from office staple to cultural punchline.

At the same time, the competitive landscape was getting weird in a way regulation couldn’t easily protect against. Stamps.com arrived with PC-based postage printing that could bypass physical meters altogether. Founded in 1996, it built a subscription model around serving the USPS and mailers through e-commerce—aimed at small businesses and home-based enterprises that wanted to be their own mailrooms without leasing a machine.

So Pitney Bowes began to morph, at least in ambition, from a near-monopoly with a predictable playbook into something closer to a challenger: trying to open new markets with new products, while dragging a huge legacy model behind it. The problem wasn’t intelligence or effort. It was fit. The culture, processes, and incentives were built for regulated hardware rentals and long-term service contracts—not fast-moving software markets with low switching costs.

By 2007, Pitney Bowes was still big and still profitable. The stock had come down from its peak, but it hadn’t collapsed. It was easy for investors—and maybe for management—to believe the company was adapting. What they couldn’t see yet was how quickly “mail decline” would go from a manageable headwind to an existential force.

The takeaway from this era is simple and brutal: when your core market enters secular decline, incremental adaptation usually isn’t enough. Pitney Bowes spent a billion dollars on acquisitions and years on initiatives. None of it changed the fundamental equation that email—and the broader shift to digital—was steadily replacing the mail.

V. The Great Financial Crisis & Leveraged Pivot (2008–2014)

The financial crisis of 2008 hit Pitney Bowes from multiple directions at once.

First, the credit business—the financing arm it had built up since the 1970s—suddenly wasn’t a quiet profit center anymore. Small businesses were under stress, defaults rose, and what had looked like steady, low-risk spread income started to feel cyclical.

At the same time, the recession poured accelerant on a trend that had already begun: fewer letters, fewer catalogs, less marketing mail. When companies tighten budgets, the mailroom is one of the first places you feel it. That double hit exposed an uncomfortable truth: Pitney Bowes’ “boring stability” depended more on a friendly economy than most investors wanted to believe.

Management was staring at a fork in the road. One path was retrenchment: protect the core, cut costs, accept that the business would shrink, and prioritize balance sheet safety. The other path was the bolder, more dangerous story: use acquisitions and leverage to buy a future.

They chose the future—funded with debt.

The narrative they rallied around was e-commerce logistics. Yes, physical mail was in secular decline. But packages were growing fast. And in the late 2000s and early 2010s, the infrastructure behind e-commerce still looked fragmented. Amazon hadn’t yet built the vertically integrated delivery machine we think of today. Pitney Bowes saw an opening: leverage its USPS relationships, its operational muscle, and its experience moving physical items to become a meaningful player in parcels.

In December 2012, the company made the pivot explicit at the top. The board appointed Marc B. Lautenbach as President and CEO, effective immediately—an IBM veteran with nearly 30 years in technology and business services. The choice was deliberate. Pitney Bowes didn’t want to be seen as a mailing equipment company trying to defend a shrinking category. It wanted to be seen—under a leader with the right résumé—as a technology company transforming itself for the digital age.

Lautenbach’s IBM background became part of the pitch: senior leadership roles across IBM North America and IBM Global Business Services, and responsibility for large customer segments and multi-billion-dollar businesses. The implication was clear: if anyone knew how to steer a legacy company through a brutal transition, it was someone who’d done it at IBM.

The vision was sweeping: remake Pitney Bowes into a commerce enabler for the digital era. Lautenbach framed the approach as choosing “the alternative that creates the most long-term value,” even when it caused “short-term disruptions”—and he acknowledged how hard that message can land with public market investors.

The disruptions weren’t theoretical. Over this period, revenues were shrinking more often than not. The company could post pockets of improved earnings—even sharp increases in net income—but the top line kept sliding, a sign that the engine driving the business was still weakening even as management worked the levers to stabilize results.

And the deal machine sped up. Pitney Bowes bought companies in software, location intelligence, and cross-border shipping—trying to assemble a portfolio that could offset the decline of meters and mail. But every acquisition also brought integration headaches, culture clashes, and, crucially, more debt.

This is when the financial engineering started to define the era. The company was trying to do three expensive things at the same time: fund a transformation, service a growing debt load, and maintain a dividend that was increasingly treated as sacred. The more pressure the business felt, the more the dividend became a symbol—and symbols can be costly.

By March 2017, the market’s verdict showed up in a very public way: Pitney Bowes left the S&P 500, where it had been listed since the index was established in 1957, and moved to the S&P 400. After roughly six decades as a large-cap staple, it was officially a mid-cap turnaround story.

Underneath all the messaging, the tension was brutal and, in many ways, unsolvable. SendTech—the legacy business—still threw off real cash, but less each year. The newer e-commerce and software bets needed investment and time, and they weren’t reliably profitable. The debt had to be serviced no matter what. And the dividend kept draining flexibility.

Something was going to have to give. The only question was what—and how painful it would be when it happened.

For investors, this stretch is the cautionary template. Debt-funded transformations can work, but they demand ruthless clarity: a believable path to profitability in the new businesses, discipline on acquisitions, and capital allocation that matches reality instead of pride. When those pieces aren’t in place, leverage doesn’t buy you time. It narrows your options.

VI. The Amazon Effect & Strategic Confusion (2015–2019)

From 2015 to 2019, Pitney Bowes hit the part of the story where the backdrop changes faster than the company can.

Amazon was no longer just a customer of the shipping ecosystem—it was becoming the ecosystem. The retailer-turned-logistics-machine started building its own delivery infrastructure, squeezing out middlemen in the process. At the same time, platforms like Shopify were pulling millions of small merchants online. Those sellers didn’t want a “mailroom.” They wanted a few clicks, a label, a competitive rate, and something that just worked.

Pitney Bowes tried to meet that moment by buying its way into relevance—and by rebranding itself as a technology provider. The deal cadence picked up again. In May 2015, it acquired Borderfree, an online shopping services provider, for about $395 million. It also acquired the cloud-based software developer Enroute Systems Corp. for an undisclosed amount. In mid-2016, it acquired Maponics, a provider of geospatial boundary and contextual data, also for an undisclosed amount. Then, in September 2017, it made the biggest swing: buying Newgistics Inc., an e-commerce and retail logistics company, for $475 million.

Newgistics is the one that mattered most, because it was the clearest declaration of intent. Pitney Bowes announced a definitive agreement to acquire the Austin-based company—positioning it as a way to move into parcel delivery, returns, fulfillment, and digital commerce solutions “at scale,” and to accelerate expansion into U.S. domestic parcels.

Marc Lautenbach framed it as catching a wave. Parcel volume was rising quickly, and Pitney Bowes paired the deal with the rollout of its SendPro C-Series products and shipping solutions. The message was simple: mail may be shrinking, but packages are booming, and Pitney Bowes is going where the growth is.

The logic looked impeccable on paper. The problem was that the upside didn’t show up in reality. Despite heavy investment to build out the Global Ecommerce (GEC) network, performance deteriorated after the Newgistics deal. GEC posted consistent annual declines in earnings before income and taxes from 2017 onward, turning what was supposed to be the growth engine into a drag.

Strategically, the company ended up in one of the worst places you can be: the middle.

It was too expensive for small sellers who could get what they needed from cheaper, simpler alternatives. It wasn’t sophisticated enough for large enterprise customers that wanted a true end-to-end logistics partner. It couldn’t compete on price with Amazon or the major carriers. And it wasn’t nimble like the software-native startups that were redefining shipping workflows.

Meanwhile, the legacy engine kept shrinking. SendTech—the postage meter business that still funded the whole experiment—was declining roughly 5–10% a year. It was still a cash cow, but it was a melting one. Fewer meters under lease. Fewer supplies sold. A smaller installed base. The thing that had once felt permanent was slowly, visibly receding.

Then, in 2019, the operational damage turned into a headline crisis.

Pitney Bowes confirmed that its systems had been hit by a malware attack that encrypted information—ransomware. The company said it had seen no evidence that customer or employee data had been improperly accessed, but many internal systems went offline, disrupting client services and corporate operations. The impact was especially painful in the place Pitney Bowes could least afford to wobble: customers’ ability to upload funds to their postage meters to pay for and print postage.

For a company built on the promise of reliable processing, weeks of disruption wasn’t just a bad quarter. It was a reputational wound.

And then came an even worse signal: after the October attack, Pitney Bowes reported it had blocked another ransomware attempt before any data was encrypted, this time linked to the Maze ransomware variant. Two attacks in close succession didn’t just imply bad luck. They suggested real vulnerabilities in the company’s technology foundation—exactly the foundation it was claiming to rebuild.

The market’s patience finally snapped. The stock cratered. And in 2019, Pitney Bowes slashed its dividend by 73.33%—a stunning reversal for a company that had treated the payout as a cornerstone of its identity for decades. The cut wasn’t just a financial decision. It was a public admission that the old playbook—debt, acquisitions, and “we’re transforming”—had hit its limits.

Management responded with moves that were overdue but unavoidable: cut the dividend, begin restructuring, and acknowledge that something fundamental had to change. But by then, the company had burned time, credibility, and flexibility. Investors were furious. Customers had experienced failure at the worst possible moment. And the balance sheet was still carrying debt from acquisitions that hadn’t delivered the returns the story promised.

The lesson of this chapter isn’t about branding. It’s about coherence. When a company keeps changing what it calls itself—meter company, communications company, commerce company, technology company—without building a profitable new center of gravity, the problem isn’t the narrative. The problem is that there isn’t one strategy strong enough to hold.

VII. COVID Chaos & Near-Death Experience (2020–2021)

March 2020 should have been Pitney Bowes’ moment.

Lockdowns forced commerce online overnight. Parcel volumes surged. Years of “e-commerce is the future” forecasts got pulled forward in a matter of weeks. If the Newgistics deal and the Global Ecommerce build-out were ever going to justify themselves, this was the window.

Instead, COVID exposed the difference between having a strategy slide and having an operation that can actually deliver.

The pandemic threw the U.S. Postal Service into turmoil. Letter volume fell in 2020, but packages hit record levels. That mix shift should have favored Pitney Bowes. But the spike in parcels overwhelmed its network. Service levels cratered. Packages got delayed. Some went missing. And for customers, that’s not a rounding error—it’s the whole product. Logistics is trust, measured in days and scans, and Pitney Bowes was suddenly failing that test at scale.

Yes, this part of the business grew during the pandemic. Pitney Bowes even opened three e-commerce service centers—in Baltimore, Orlando, and Oakland—in 2020 to expand capacity. But growth didn’t save them, because the unit economics were backwards. The more volume they handled, the more they lost per package. It’s the nightmare version of “scale.”

Financial stress followed fast. Debt covenants came under pressure. Liquidity became a daily concern. The stock sank below $3 at its low point—down roughly 95% from the 1999 peak. For a company that had spent decades as a conservative S&P 500 stalwart, trading at penny-stock levels wasn’t just humiliation. It was a flashing red sign that the market was openly questioning survival.

So Pitney Bowes did what distressed companies do: it sold pieces of itself to buy time.

In August 2019, Syncsort announced plans to acquire Pitney Bowes’ software solutions business for about $700 million, and the deal closed in December 2019. Asset sales then accelerated. Businesses that had once been pitched as the company’s digital future—often acquired at premium prices—were divested for less than management would’ve wanted. Every sale added cash. Every sale also narrowed the company further, leaving it more exposed to the parts of the portfolio that were already wobbling.

Next came the internal triage. Headcount was reduced. Management layers were removed. Facilities were consolidated. The cost structure that had been built for a much larger company had to be cut down to match a smaller reality—and even that reset still risked being too slow.

Debt talks became unavoidable. Lenders who had underwritten a transformation story were now negotiating with a company in distress. The stakes were simple: if Pitney Bowes tripped covenants, creditors could demand accelerated repayment—something the company didn’t have the capacity to meet. The negotiations were tense because they had to be.

And then you get to the most revealing question of this entire chapter: why didn’t Pitney Bowes go bankrupt?

Because the original engine, the one everyone had been trying to outrun, kept the company alive. SendTech—the legacy postage meter business—continued to throw off cash. Even in a pandemic. Even as mail volumes declined. Even while the growth bet was bleeding. The installed base kept paying leases and buying supplies. The cash flow was shrinking, but it was steady enough to keep the lights on and service the debt.

The situation churned leadership, too. Pitney Bowes ended up on its fourth CEO in three years, a revolving door that reflected how hard the job had become—and how urgently the board was searching for a path that didn’t end in a restructuring.

Under that pressure, the operational turnaround finally began in earnest: fix the delivery network, exit unprofitable contracts, right-size the cost structure. These were the moves that could have been made from a position of strength. Instead, they happened in survival mode, when every mistake was amplified and every delay was costly.

The COVID period distilled the company’s modern paradox into one line. The legacy postage meter business—unsexy, declining, but reliably cash-generative—saved Pitney Bowes. The e-commerce logistics bet—sexy, fast-growing, and structurally unprofitable—nearly broke it.

VIII. The 2020s: Zombie or Phoenix? (2022–Present)

The Pitney Bowes story in the 2020s is, at its core, about what happens when a long-suffering shareholder decides the company has had enough “strategy” and wants results.

Years of underperformance had drawn activists to the name, most notably Hestia Capital. The Pennsylvania-based hedge fund first disclosed a stake in 2019. By December 2022, it had built its position to roughly 7% of outstanding shares, making it one of Pitney Bowes’ largest shareholders.

Hestia’s argument was simple and cutting: management was lighting cash on fire in unprofitable e-commerce logistics while underinvesting in, and underappreciating, the parts of Pitney Bowes that still worked. Their prescription followed from that: sell or shut down Global Ecommerce, cut costs hard, focus on cash generation, and return capital to shareholders.

Pitney Bowes pushed back. In its response, the company argued that Hestia was angling for a public fight that served its own takeover interests rather than the interests of the company and its shareholders. The temperature rose quickly, and it set up a bruising proxy contest at the annual meeting.

The fight got personal and very specific. Pitney Bowes issued shareholder letters describing its engagement with Hestia and urging investors to back the board’s slate. Hestia, meanwhile, put forward its own slate—stacked with industry veterans, including former executives from Stamps.com and Newgistics.

And yes, the irony was obvious: the CEO of the very company Pitney Bowes had paid $475 million to acquire—Newgistics—was now being nominated to help clean up the aftermath of that acquisition.

Hestia ultimately won. Its founder, Kurtis Wolf, joined the Pitney Bowes board in May 2023 after the hedge fund prevailed in the proxy fight. The activists didn’t just land a seat at the table—they grabbed real influence over the agenda.

In the reshuffle that followed, Pitney Bowes appointed Lance Rosenzweig as Interim CEO, framing the choice around a familiar turnaround checklist: drive efficiencies, simplify the corporate structure, and accelerate debt paydown. Management targeted additional annualized cost savings of $60 million to $100 million, alongside tighter cash management and balance sheet improvement.

The reset wasn’t subtle. Leadership moved to strip out cost, improve cash discipline, and refocus the company around the businesses with durable economics—SendTech, Presort, and Global Financial Services. The message was basically: fewer bets, less sprawl, more cash.

And then came the decision that critics had been demanding for years. Pitney Bowes finally exited Global Ecommerce.

On August 8, 2024, Pitney Bowes announced it had sold a controlling interest in the entities representing a substantial majority of the Global Ecommerce segment to Hilco Commercial Industrial, an affiliate of Hilco Global. The sale was structured to support a value-maximizing liquidation of certain GEC entities under Chapter 11 protection.

The company didn’t sugarcoat why it was doing this. Global Ecommerce had struggled to reach profitability for years amid macro and industry headwinds. Pitney Bowes said it expected the exit to eliminate substantially all of the losses associated with the segment—losses that were about $136 million in 2023.

The scale-versus-profitability mismatch was the damning part. Global Ecommerce could move massive volume—millions of packages a month—serving hundreds of brands across a network of 12 U.S. parcel sortation centers. And it still didn’t generate the returns Pitney Bowes needed. As the company put it: “Simply put, the GEC business is no longer profitable and has not been for some time.”

Even the attempted sale process underscored how little value was left. Acting on Pitney Bowes’ behalf, J.P. Morgan contacted 30 potential buyers starting in November 2023, executed NDAs with 17, and ran what the company described as a robust marketing process over more than eight months. In the end, Pitney Bowes said it received no binding bids at an acceptable price.

No one wanted to buy a money-losing logistics operation—not for anything close to a price that let Pitney Bowes save face. The least-worst option was to hand it to a liquidation specialist and walk away.

By May 2025, the activist era reached its clearest milestone: Pitney Bowes announced that its board had appointed sitting director Kurt Wolf as CEO, effective immediately. Wolf succeeded Rosenzweig, who retired from his CEO and director roles.

The board pointed to the stock’s performance during the activist-led turnaround—saying total shareholder returns had exceeded 200% since Wolf joined the board and later chaired the Value Enhancement Committee—and argued that his familiarity with the company and experience as an operator made him the right person to lead the next phase.

What’s left is a much smaller, more narrowly defined Pitney Bowes than the one that once dominated mailrooms. The company expected 2025 revenue of $1.95 billion to $2.0 billion and Adjusted EBIT of $450 million to $480 million, with adjusted EPS expected to range from $1.10 to $1.30.

Operationally, Pitney Bowes now runs primarily through two core segments: SendTech, the legacy mailing and shipping technology business, and Presort Services, which sorts mail to qualify for USPS workshare discounts. They’re stable, profitable, and slowly declining. Management also emphasized that it had improved free cash flow, strengthened the balance sheet, and pushed maturities out—saying there was no debt maturing over the next 24 months.

So the investment question changes. This isn’t a “transform into a growth company” story anymore. It’s a managed-decline and cash-harvest story—can the remaining businesses keep throwing off enough cash, for long enough, to make shareholders whole while the company gradually shrinks?

That’s not as exciting as the old transformation pitch. But after a decade of big promises and ugly economics, it’s the first version of the Pitney Bowes strategy in years that matches the reality of what the company actually is.

IX. Business Model Deep Dive & Unit Economics

To understand Pitney Bowes today, you have to stop thinking about “the old postage meter company” versus “the failed e-commerce pivot,” and start looking at what’s actually left. It’s a smaller business now, but it’s not a mystery. It’s basically two operating engines—plus a financing layer that makes the whole system work better.

SendTech Solutions is the original monopoly, updated for modern times. It provides physical and digital shipping and mailing technology—tools for sending, tracking, and receiving letters, parcels, and flats—along with supplies, maintenance, and financing options that help customers buy equipment and products.

The model is still the same elegant loop Pitney Bowes has run for decades. Equipment is leased, not sold. Customers pay recurring fees for service and support. Consumables like ink and supplies layer on high-margin revenue. Financing adds spread income. And Pitney Bowes also operates a state-chartered bank in Salt Lake City that clients use to purchase U.S. postage—another way the company stays embedded in the workflow.

Even in decline, this is the cash engine. SendTech Solutions accounted for 38% of Pitney Bowes’ revenue and generated $429 million in earnings before interest and taxes in 2021. Revenue has continued to trend down, but margins stay attractive because the installed base produces recurring revenue that’s expensive for customers to unwind and relatively cheap for Pitney Bowes to service.

Now the job isn’t “turn SendTech back into a growth story.” It’s to manage the decline without breaking the economics. The company has said it expects SendTech revenue to flatten out by the start of fiscal year 2026, and it sees longer-term opportunity from expanding further into e-commerce shipping. In other words: even inside a shrinking business, shipping-related software and services can still be a pocket of growth.

Presort Services is the quieter segment, but it matters just as much. Presort offers mail sortation services that help clients qualify first-class mail, marketing mail, marketing mail flats, and bound printed matter for USPS workshare discounts.

The economics here are refreshingly simple. The USPS offers discounts to big mailers if they do part of the sorting work themselves. Pitney Bowes acts as the aggregator and operator—taking in mail from multiple customers, sorting it to postal requirements, and keeping a portion of the workshare discount as revenue. Pitney Bowes is a certified work-share partner of the United States Postal Service, and it helps the agency sort and process 15 billion pieces of mail annually.

This is the toll-road business inside Pitney Bowes. As long as meaningful mail volume exists and USPS continues to incentivize worksharing, Presort can keep producing profit. And the relationship with USPS—nearly a century in the making—adds a kind of durability that’s hard to replicate.

The Financial Services segment rounds out the picture. The Pitney Bowes Bank continues to operate in the normal course, and equipment financing plus the postal bank generate interest spread income that diversifies the revenue base and supports the core segments.

Once Global Ecommerce is stripped out, the unit economics look a lot cleaner. Pitney Bowes now expects $170 million to $190 million in net annualized cost savings, up from the previous target of $150 million to $170 million. And on cash optimization, the focus is less about “having cash” and more about needing less of it—driven by exiting GEC, improving internal forecasting, and actively managing liquidity instead of simply holding balances.

For investors, the hard part isn’t understanding how the business works. It’s modeling the slope. If SendTech revenue declines around 5% a year but the company can reduce costs faster than that, margins can expand even as the company shrinks. That’s the core idea behind value extraction: harvest what’s left without starving the machine. Done well, it can generate real shareholder returns. Done poorly, it turns managed decline into accelerated collapse.

X. Strategic Frameworks: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Mixed

In SendTech, the barriers are still real. You can’t just wake up one day and decide you’re going to lease postage meters—USPS approval is required, and only a small handful of companies have it. Pitney Bowes is one of only five authorized by the USPS to lease meters.

But the moment you move from regulated hardware into software—shipping labels, rate shopping, workflow tools—the moat disappears. Anyone with a decent product team can build a shipping platform. Distribution and execution matter, but the door is wide open.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low

For traditional equipment, Pitney Bowes largely controls its own destiny: it manufactures its own machines and buys mostly commodity inputs. The relationship that matters most isn’t a component supplier—it’s the USPS.

And that’s less a classic “supplier” dynamic and more a partnership that shapes the entire business. Pitney Bowes has leaned on its last-mile delivery relationship with the USPS as a core capability, arguing it gives the company the resources to compete against larger players in its target markets.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH and Increasing

Small businesses have more choices than ever—for postage, for shipping, for label software, for everything. And at the enterprise level, procurement is brutal: big customers negotiate hard, and they have options.

The installed base that once acted like a captive audience now cuts the other way. Those customers are still there, paying leases and buying supplies—but many are effectively “on the clock,” and when contracts expire, switching gets easier.

Threat of Substitutes: EXTREME

This is the existential one. Digital communication didn’t just create a competitor; it removed the need. Every email is a letter that never gets mailed. That’s the secular decline underpinning SendTech.

On the parcel side, technology is also the driver—just in the opposite direction. E-commerce created more packages. But it also concentrated power in the biggest ecosystems. Every Amazon delivery is one more reminder that the most scaled players don’t need a middleman to get a box to a doorstep.

Competitive Rivalry: Intensifying

Pitney Bowes still plays from a position of scale, but not dominance. It holds the number-two spot with roughly 30% market share—meaning it has gone from “utility-like monopoly” to “large competitor.”

And the competition comes from both sides. Legacy rivals like Quadient keep pressure on meters and mailroom equipment. Meanwhile, software-first players like Stamps.com (now Auctane) attack with simpler products, faster iteration, and lower switching costs.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

-

Scale Economies: ERODED

Pitney Bowes once benefited from classic scale: a big installed base, a massive service network, and the economics of running the category. But software competitors can now scale without trucks, technicians, or physical footprint. Scale still matters—just less in the places Pitney Bowes historically owned. -

Network Effects: WEAK

There’s no meaningful network effect in meters. One customer leasing a meter doesn’t make another customer’s meter better. Contrast that with software platforms where usage and data can compound value across users. -

Counter-Positioning: NONE

Pitney Bowes is the incumbent being counter-positioned against. When Stamps.com brought PC-based postage to market, it wasn’t trying to out-Pitney Bowes Pitney Bowes—it reframed the whole category away from meters. -

Switching Costs: MODERATE and Declining

In meters, switching costs still exist: multi-year contracts, equipment swaps, process change. But they’re fading as contracts roll off and alternatives proliferate. In software shipping, switching costs are close to zero—if the product disappoints, customers can leave in an afternoon. -

Branding: WEAK

Pitney Bowes is a known B2B name, but not a magnetic one. It doesn’t command a premium based on brand alone. For many customers, it’s less “the company we want” and more “the vendor we’ve had.” -

Cornered Resource: ERODED

The USPS relationship used to be a cornered resource in the purest sense—hard to access, hard to replicate, and critical to the category. It still matters, but it’s less exclusive and less differentiating than it once was. The patents are long expired, and the company doesn’t have a unique talent lock, either. -

Process Power: SOME

This is where Pitney Bowes still has something real. Presort is operationally complex, and doing it well takes years of accumulated know-how. That expertise is replicable in theory, but difficult in practice—and it’s concentrated in one segment where execution matters.

The Verdict: Pitney Bowes once had multiple durable powers—scale, switching costs, and a cornered resource through USPS access. Today, most of that has eroded. What remains is a company leaning on process advantages in presort and the cash flow of a managed legacy base, not a company building a new, defensible growth moat.

XI. Lessons & Playbook: What Founders & Investors Should Learn

The Monopoly Trap

Pitney Bowes’ 85% market share felt permanent—until it wasn’t. That’s the hidden risk in any regulatory moat: it can flip from fortress to cage the moment policy shifts, or the moment technology routes around the whole system.

The postage meter business depended on USPS authorization. When the USPS approved PC-based postage, the wall cracked. When email replaced letters, the wall stopped mattering.

Lesson: Regulatory moats only endure with regulatory stability. If your advantage comes from permission, you have to track not just today’s rules, but the technological and political changes that could make those rules irrelevant.

The Debt-Funded Pivot

Pitney Bowes tried to buy its way into the future, largely with debt. The Newgistics deal alone cost $475 million. Borderfree was about $395 million. Add in the broader software and data acquisitions, and the price tag climbs fast.

When those bets didn’t produce durable profits, the debt didn’t go away. It just sat there—demanding interest, tightening covenants, and limiting options.

Lesson: Debt-funded transformations only work when the new business reliably earns returns above the cost of capital. When it doesn’t, leverage isn’t rocket fuel. It’s an anchor.

The Innovator's Dilemma in Practice

Why didn’t Pitney Bowes build Stamps.com? It had the customer relationships. It had decades of USPS knowledge. It had engineering talent. But it also had a legacy business that was so profitable that the alternatives looked puny.

Why cannibalize something like $400 million in meter EBIT for a software business that might generate $40 million?

Lesson: The same math that makes self-disruption feel irrational is the math that guarantees you’ll get disrupted by someone else.

Dividend Policy as Signal

For decades, Pitney Bowes treated the dividend as a core part of its identity—maintaining and increasing it even as the underlying business weakened. When the company finally cut the dividend by 73% in 2019, the market didn’t read it as “prudence.” It read it as “we waited until we had no choice.”

Lesson: Dividend policy should follow sustainable cash generation, not investor expectations or management pride. If you’re borrowing to defend a dividend, you’re not rewarding shareholders—you’re selling them optics.

The Conglomerate Discount

At different points, Pitney Bowes stretched across postage meters, copiers, fax machines, software, location intelligence, cross-border logistics, domestic parcels, and financial services. The pitch was “diversification.” The lived experience was complexity and a strategy that never quite added up.

Lesson: Diversification without real synergies usually creates confusion, not resilience. Focus is what enables excellence—especially when your core business is already under pressure.

The Amazon Lesson

Pitney Bowes made a big bet on becoming an e-commerce logistics player at the exact moment Amazon was building its own logistics infrastructure. That’s a brutal place to stand: your potential customer is also building the machine that will make you unnecessary.

Lesson: Partner relationships can turn into competitive threats faster than most forecasts assume. When one company is building the ecosystem, it usually captures most of the value of serving it.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Perspective

The Bull Case

-

SendTech cash flows hold up longer than people expect. Even with mid-single-digit annual declines, the installed base still throws off meaningful cash. If management can take costs out faster than revenue falls, you can actually see margins improve even while the top line shrinks.

-

Debt reduction buys breathing room. With no debt maturing over the next 24 months, Pitney Bowes has something it hasn’t had in a long time: time. In a turnaround, time is optionality—especially compared to the “refinance or die” dynamic that leverage can create.

-

Presort Services is a real asset, not a narrative. The USPS workshare relationship—built over decades—can’t be copy-pasted by a startup with a slick UI. As long as physical mail remains a meaningful channel, Presort can keep generating profit.

-

Expectations are already in the basement. After years of missed promises and strategic whiplash, the market isn’t paying up for a comeback story. That’s the setup where even modestly better execution can re-rate the stock.

-

Capital returns are coming back. The company intends to repurchase $150 million of shares in 2025, using the remainder of the board’s previously disclosed repurchase authorization. In other words: management is saying the cash flows are stable enough to start shrinking the share count again.

-

Management incentives are aligned with the equity. Kurt Wolf isn’t just a hired operator—he’s also a major shareholder through Hestia. The bet he’s making is the same one shareholders are making: that disciplined execution and cash generation can translate into stock appreciation.

The Bear Case

-

The core market can keep falling—and it might fall faster. Market Dominant mail volume dropped 46% between fiscal years 2008 and 2023. The scary part isn’t that it’s declining; it’s that there’s no obvious floor. If the decline rate accelerates, cost cuts may not keep up.

-

USPS reform is an existential variable. Presort depends on workshare economics and the structure of USPS operations. Major changes—privatization, service reductions, or bankruptcy—could hit the very segment that now looks like the “stable” one.

-

Technology debt isn’t optional spending. The ransomware attacks weren’t just bad headlines; they were signals that systems and controls needed investment. If Pitney Bowes has to spend heavily just to keep operating reliably, that’s cash that can’t go to debt paydown or shareholders.

-

Competition doesn’t stop just because you’re shrinking. Cloud-native shipping platforms keep improving, and they keep taking share from legacy mailing and shipping workflows. Pitney Bowes’ roughly 30% share could erode further, turning “managed decline” into something uglier.

-

There’s no obvious growth engine left. With Global Ecommerce gone, the bull case is mostly about harvesting cash, not reigniting growth. That can work—but it puts a ceiling on upside if the business simply stabilizes rather than surprises.

-

The company’s recent history earns skepticism. Pitney Bowes churned through CEOs and swung at multiple transformations that didn’t stick. Even with new leadership, investors have plenty of reasons to demand proof before trusting the next plan.

What to Watch

Two numbers matter most:

-

SendTech revenue decline rate. If the decline stays around the mid-single digits, the “milk the installed base” strategy can work. If it accelerates toward the high single digits, the runway shrinks fast—and the whole thesis gets harder.

-

Free cash flow conversion. Management guided to 2025 free cash flow of $330 million to $370 million. Hitting that range—and showing it’s repeatable—will determine whether this is a durable cash machine or a short-lived stabilization.

Beyond that, keep an eye on customer churn, USPS policy changes, the credit rating trajectory, and whether cost reductions show real operating leverage or just one-time relief.

XIII. Epilogue & Future Scenarios

The story of Pitney Bowes admits multiple endings. None of them are Hollywood. But some are clearly better than others.

Scenario 1: Managed Decline

The most likely path. Pitney Bowes becomes what GE or IBM became in their mature phases: a melting ice cube that focuses on cash, not growth. SendTech and Presort keep drifting down a few percent a year. Management keeps taking costs out to defend margins. Debt gets paid down. Capital returns—dividends and buybacks—do what they’re supposed to do: give shareholders the cash the business no longer needs to reinvest. Over time, the company either becomes small enough to be strategically irrelevant or gets folded into a larger player that wants the installed base and the cash flow.

Scenario 2: Acquisition

Private equity has circled companies like Pitney Bowes for years because the playbook is obvious: buy at a depressed valuation, cut overhead hard, harvest cash from declining-but-profitable units, and eventually sell pieces or run it off. Wolf and other members of leadership planned to conduct a comprehensive strategic review over the remainder of 2025, supported by independent advisors. And in the real world, “strategic review” is often the first public step toward a sale.

Scenario 3: Breakup

There’s a plausible argument that the pieces are worth more than the whole. SendTech could be rolled into a competitor like Quadient. Presort could be sold to a logistics or mail-services operator. Financial services could go to a bank or a private credit buyer. Strip out the corporate overhead, hand each business to an owner optimized for it, and the conglomerate discount disappears.

Scenario 4: Reinvention (Low Probability)

The miracle ending: some new technology—AI-driven logistics optimization, a new postal workflow, an adjacent platform—creates a real growth engine. This is the outcome management teams love to imply. It’s also the outcome incumbents almost never deliver once the core market is structurally shrinking. Low probability.

The Bigger Picture

What does Pitney Bowes tell us about American industry in the digital era?

First: no moat lasts forever. Regulation, installed bases, and decades of customer relationships can look unbreakable—until technology routes around the entire system. The more a company optimizes for the old world, the harder the new world hits.

Second: financial engineering can’t replace strategic clarity. Pitney Bowes tried acquisitions. It tried leverage. It tried rebrands and pivots. But the question never went away: what do we do that is uniquely valuable when communication becomes software and shipping becomes platform-driven? Without a compelling answer, the moves were motion, not progress.

Third: incentives aren’t a footnote—they’re the plot. For years, management behavior was shaped by protecting the dividend and hitting near-term targets, even as the long-term base eroded. Today’s leadership is more directly tied to the equity. That can change decisions. It doesn’t guarantee success, but it does change what “success” means.

Fourth: sometimes the best outcome is accepting reality early. In a declining business, the highest-return move is often not reinvention—it’s disciplined harvest: simplify, protect the profitable core, pay down debt, and return cash. Pitney Bowes spent billions chasing e-commerce logistics. In hindsight, much of that capital would have created more value through debt reduction or shareholder returns.

Final Reflection

Arthur Pitney, tinkering in that wallpaper store in 1901, couldn’t have imagined email, Amazon, or a world where physical mail becomes a legacy channel. But he probably would’ve understood the underlying tension: the gap between a great idea and a durable business—and how quickly “what works” can turn into “what traps you.”

Pitney Bowes was 105 years old in 2025. It had already survived the Great Depression, World War II, the rise of computing, the internet, multiple ransomware attacks, and a near-death balance sheet. Whether it survives another decade—let alone another century—comes down to choices being made right now.

The difference between a 100-year company and a 150-year company isn’t luck. It’s the willingness to face the competitive reality, allocate capital without nostalgia, and accept that what made you great might not be what keeps you alive.

Pitney Bowes’ next chapter is being written in real time. Whether it ends in a quiet fade or something closer to renewal, the lesson is the same: technological disruption doesn’t ask for permission. And every company—eventually—gets its turn.

XIV. Recommended Resources & Deep Dive Links

Top 10 Resources:

-

Pitney Bowes Annual Reports (2008, 2015, 2019, 2024) - SEC filings that trace the “transformation” in management’s own words, including what worked, what didn’t, and what got glossed over

-

The Innovator's Dilemma by Clayton Christensen - The cleanest lens for why Pitney Bowes struggled to cannibalize a highly profitable legacy business before someone else did it for them

-

USPS Office of Inspector General reports on mail volume trends - Ground truth on the secular decline behind the story, and why it wasn’t just a cyclical downturn

-

Hestia Capital proxy presentations (2023) - The activist investor’s full case for change, with pointed critiques of capital allocation and strategy

-

Pitney Bowes earnings call transcripts (2015-present) - A play-by-play of how the narrative shifted over time—what management emphasized, what it de-emphasized, and when reality forced a reset

-

USPS Delivering for America 10-Year Plan - Critical context for how USPS plans to modernize, and what that could mean for Presort Services and workshare economics

-

Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital by Carlota Perez - A broader framework for why incumbents often pair real disruption with financial maneuvering—and why that mix can end badly

-

Wall Street research on Stamps.com/Auctane - A useful contrast case: how a software-first approach to postage and shipping outflanked the legacy meter model

-

Court filings from the Global Ecommerce bankruptcy (August 2024) - The most detailed record of how the e-commerce logistics bet unraveled, including the mechanics behind the exit

-

Recent investor presentations and CEO letters - Where the current strategy is spelled out plainly: what Pitney Bowes says it is now, and what it’s no longer trying to be

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music