Paycom: The Assassin of the Service Bureau

I. Introduction: The "Oklahoma Standard"

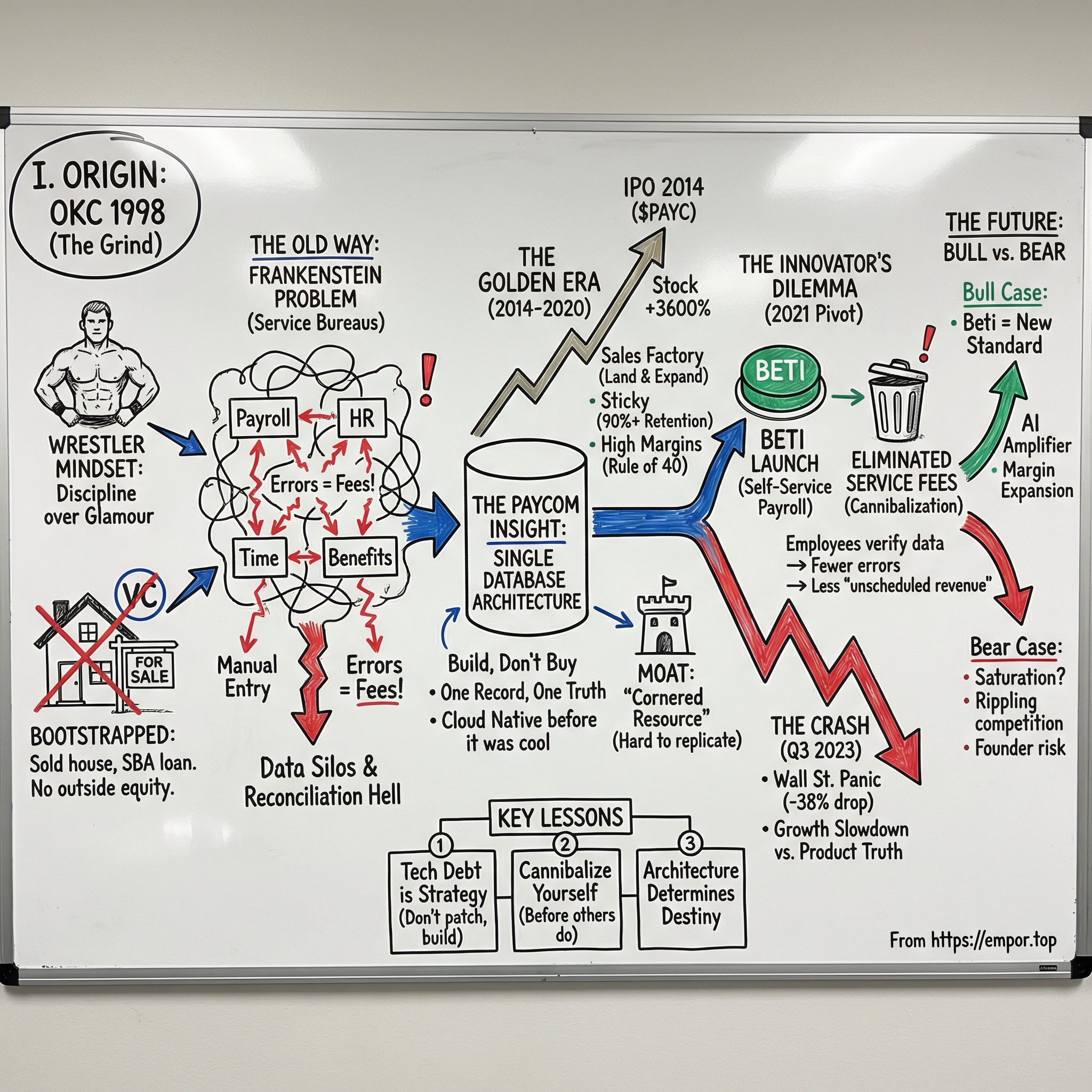

Picture Oklahoma City in 1998. The skyline is modest. Oil and real estate still define the economy. And “tech” is something happening fifteen hundred miles away, on the coasts. In that unlikely setting, a 27-year-old former college wrestler is about to start a company that will eventually reshape how millions of Americans get paid.

His name is Chad Richison. He grew up in Tuttle, Oklahoma, graduated from Tuttle High School, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in mass communications and journalism, with a minor in German, from the University of Central Oklahoma in 1993. While he was there, he wrestled.

Wrestling is the kind of sport that rewires you. It’s not glamorous. It’s repetitive. It’s painful. And it teaches a very specific lesson: the work happens long before anyone is watching. Richison has said, “Wrestling has had a profound impact on my life and helped instill the values, work ethic and competitiveness that remain with me to this day.” That intensity becomes an important thread in the Paycom story—because this company is built like a grind, not a gamble.

This is not a Silicon Valley origin story. There were no Stanford intros, no Sand Hill Road meetings, no venture term sheets. To fund the start, Richison sold his house in Denver, took out a Small Business Administration loan, and liquidated his 401(k). Paycom began with zero outside equity. It was bootstrapping in the purest form: a founder putting everything on the line behind an insight formed in the trenches of payroll sales.

Richison has served as CEO and President since founding Paycom in 1998. By 2024, Paycom was a $1.88 billion revenue business that stored data for over 7 million people employed by its clients. The stock hit an all-time high on November 2, 2021, at $558.97—more than 3,600% above its IPO price. And then came the part of the story that matters just as much: a choice that slowed growth, rattled Wall Street, and tested the faith of shareholders—a deliberate act of self-cannibalization.

At its core, the Paycom thesis is simple, almost stubborn. What if you built payroll software from scratch on a single database—and never acquired your way to growth? What if you refused to bolt together mismatched systems the way the rest of the industry did? And what if, after you won, you shipped a product so effective it wiped out a meaningful chunk of your own revenue?

This is the story of the Single Database versus the world. It’s a masterclass in counter-positioning, an innovator’s dilemma playing out in real time, and one of the clearest modern examples of a company choosing long-term product truth over short-term financial comfort. Whether the gamble ultimately pays off remains to be seen. But to understand Paycom now, you have to understand how it got here.

II. Context: The Frankenstein Problem

To understand what Paycom disrupted, you have to understand what payroll looked like before software started eating it.

In the late 1990s, the industry revolved around two giants: ADP (Automatic Data Processing) and Paychex. Both had been around for decades, and both offered a widening menu of payroll and HR services. But they weren’t “software companies” in the way we mean it today. They were service bureaus—massive processing operations that took your employee data, disappeared into a back room, and came back with printed checks.

That model made perfect sense in a world of mainframes, paper, and physical distribution. A company would fax its time sheets (yes, fax) to ADP or Paychex. Clerks would key in the numbers. Payroll would run on the bureau’s systems. Checks would get printed, stuffed, and shipped. The loop took days, sometimes a week. And errors weren’t edge cases; they were part of the operating system.

Now put yourself in the shoes of a mid-sized business. If someone’s hours were wrong, you often didn’t discover it until after the check was cut. Fixing it meant an off-cycle run—something the service bureau could do, and would happily charge for. Want to see your own payroll data? Request a report. Need to change benefits elections or tax withholdings? Call your rep. The whole relationship was built around information asymmetry: they held the data, and you paid to interact with it.

But the real crack in the foundation wasn’t just service. It was architecture.

As the human capital management world matured, everyone realized payroll wasn’t a standalone function. It touched time tracking, benefits, hiring, performance, compliance—everything. And the broader HR tech market fragmented into a sprawl of point solutions, with many companies stitching together a dozen-plus tools. The predictable outcome was data silos: multiple “sources of truth,” inconsistent employee records, and a never-ending reconciliation exercise.

So what did the incumbents do? What incumbents always do. They bought their way forward.

They acquired time-tracking companies, benefits administration tools, talent management systems—then tried to integrate them. The result was what insiders started calling “Frankenstein software”: a patchwork of acquired products, each with its own database, its own screens, its own logic, its own version of the employee record. In practice, “integration” often meant the same data living in multiple places, loosely stitched together with exports, imports, and manual work.

And that’s where a technical problem turns into a human one. When data has to move from System A to System B, somebody has to push it—re-enter it, map it, verify it, fix it when it breaks. Every handoff is a chance for an error. Forrester has estimated that payroll mistakes alone can cost businesses millions annually. And each error triggers a correction: more time, more stress, more off-cycle runs, more fees.

This was the industry Chad Richison learned from the inside. In the early 1990s, he started in sales at ADP, then moved to Colorado to work for a smaller regional payroll provider. For roughly two and a half years, he watched the machine work up close—hearing the same complaints, over and over, from customers and HR teams stuck doing manual entry and cleanup.

The insight that became Paycom wasn’t flashy. It was almost obvious—once you saw it.

The internet didn’t have to be just a window into payroll. It could be the engine. What if, instead of sending your data into a black box and waiting for results, the company itself could enter and manage payroll in real time? What if payroll, time, benefits, and HR all lived in one place—one system, one login, one record? And what if the person who created the data could verify the data?

That wasn’t an incremental improvement to the service bureau model. It was a different model entirely. And in 1998, when the internet was still young and most businesses were barely getting comfortable online, it was a bet that sounded, to many, like insanity.

But here’s why it matters even now: the Frankenstein problem didn’t disappear. Despite decades of consolidation and billions spent on acquisitions, most HCM vendors still run on multiple databases that have to be “integrated” after the fact. HR and payroll professionals have reported using an average of 6.17 HCM providers. Every time data moves, friction shows up. Friction creates errors. Errors create cost.

And cost—especially avoidable cost—creates opportunity.

III. The Founding: 1998 & The Dot-Com Survivor

The founding of Paycom reads less like a startup fairy tale and more like a stress test.

In 1998, Chad Richison was 27. He had a vision, a journalism degree, roughly two and a half years of payroll sales experience, and essentially no financial safety net. So he made the kind of funding decision you only make when you have no other choice: he sold his house in Denver, took out a Small Business Administration loan, and liquidated his 401(k). No venture capital. No outside equity. If Paycom didn’t work, it didn’t just fail on a cap table. It failed in his living room.

And in the beginning, “product” wasn’t a department. It was Richison.

He was instrumental in designing the original online interface, sketching workflows with whatever tools he could get his hands on—Lotus Notes, Microsoft Word, even Paint. Let that land: the first version of what became one of the most successful payroll software platforms in America was mapped out with Microsoft Paint. No sprawling engineering team. No product org. Just a founder trying to make something real enough to sell.

Around that same time, Richison moved back to Oklahoma and founded Paycom in Oklahoma City. That choice looked unconventional, and it stayed unconventional. Silicon Valley wasn’t just far away geographically; it was far away culturally. Oklahoma was cheaper. The talent pool was smaller but under-recruited. And the norms rewarded work ethic, humility, and long-term relationships—ingredients that fit a business built on trust and repetition.

Paycom is believed to be one of the first companies to process payroll completely online. That statement is easy to gloss over now, in a world where every bank transfer and benefits election happens on a phone. But this was 1998. It was the year Google was founded. “Cloud” wasn’t a strategy; it was something in the sky. And most businesses were still uneasy about doing anything important on the internet, let alone payroll.

The timing was perfect and terrible at the same time. Perfect because the web finally made a different payroll model possible. Terrible because the dot-com era trained everyone to expect startups to burn money like kindling. Two years later, the dot-com crash would wipe out roughly 78% of the NASDAQ. Pets.com and Webvan became cautionary tales of what happens when capital is plentiful and discipline is optional.

Paycom didn’t have that option. It had to sell to survive.

From day one, the model was to deliver payroll through a software-as-a-service platform. That sounds ordinary now. Back then, it was a bet that customers would trust an online system with the most sensitive thing they do every two weeks: paying their people. The pitch wasn’t just “better software.” It was “a better way to run the whole function.”

The early years were a grind, and the culture followed Richison’s wrestling DNA. Competitive. Disciplined. Allergic to excuses. Reps were expected to prospect relentlessly, learn the product cold, and win over customers who were deeply skeptical that an internet startup could handle payroll without mistakes.

But bootstrapping created an advantage that only becomes obvious in hindsight: it forced Paycom to be real.

When the bubble burst in 2000, the companies that got hit hardest were the ones that had raised huge rounds and spent them before they’d earned the right to exist. Paycom didn’t have massive capital to burn, which meant it didn’t build a business that required massive capital to continue. It had been forced into a kind of operating discipline from the start. When the market turned, Paycom didn’t “pivot.” It just kept selling.

By 2001, only three years in, Paycom broadened its offerings into additional human resource management functionality. The ambition was clear: this wouldn’t be a narrow payroll tool. It was going to become a suite.

That same discipline also shaped the company’s long-term product strategy. Paycom’s balance sheet ended up nearly debt-free, and goodwill remained minimal—about $50 million—because the company didn’t grow by buying other companies. It grew by building. This wasn’t just frugality. It was architecture as strategy.

From the beginning, Paycom focused on building a comprehensive, cloud-based HCM platform on a single database. Every module lived in the same system, pulling from the same employee record. No bolt-ons. No messy integrations. No acquired codebases with different assumptions and different definitions of the truth.

That decision—to build rather than buy—became the most important strategic choice the company ever made. It meant slower, harder growth early on. It meant passing on the quick revenue that comes from acquisitions. But it also meant that decades later, Paycom would own something incredibly rare in this category: a truly unified platform that competitors couldn’t copy without rebuilding their stacks from scratch.

And this is why the founding story still matters. It explains the company’s DNA: the discipline, the organic-growth bias, and the willingness to trade short-term comfort for long-term structural advantage. Those aren’t just origin-story details. They’re the same instincts that, a quarter-century later, would drive Paycom to launch Beti—even knowing it would rattle Wall Street.

IV. The Architecture as Strategy

If you take away one thing from the Paycom story, it should be this: the database is the strategy. A single system—one database—means data can move without friction, without handoffs, and without the “somebody has to re-enter it” tax. And in HR and payroll, that’s the difference between software that helps and software that actually automates.

That can sound abstract until you picture a normal Tuesday for an HR manager.

An employee gets promoted. In a Frankenstein setup, you update the HR system. Then you jump to payroll to change the pay rate. Then benefits, because eligibility might change. Then time and attendance, because PTO accrual might be tied to role or tenure. Each step may mean a different screen, a different workflow, sometimes a different login. And every handoff is a chance to create a mismatch—two “sources of truth,” three versions of the employee record, and a reconciliation project hiding inside what should’ve been a two-minute update.

In Paycom’s world, you change the record once.

Because Paycom built its HR and payroll tools itself—inside the same database—those downstream fields update automatically. Pay rate. benefits eligibility. PTO accrual. Everything is drawing from the same underlying employee record, so there’s no syncing and no “integration” glue holding the product together. There’s nothing to integrate.

This is also why Paycom’s timing mattered. Back when payroll was dominated by on-prem software and manual processes, Paycom offered one of the first fully online payroll platforms in the country. That meant real-time processing without installing hardware or running a mini data center in your office. Richison leaned into a subscription model with pay-as-you-go pricing, which lowered the barrier for small and mid-sized employers to try something new. But the real innovation wasn’t just “online payroll.” It was building payroll and HR together, from day one, in a single architecture designed to eliminate silos and the manual re-entry that creates errors.

Once you see the implications, you start to understand why this became a moat.

Payroll is already a high-switching-cost category. You’re dealing with compliance, taxes, benefits, and people’s money. But Paycom’s integrated platform and employee self-service tools turn that natural switching cost into something even stickier. Competitors can copy features. They can’t easily copy foundations.

Take ADP. ADP is the giant of the service-bureau era, and it got there partly through decades of acquisitions. Each acquisition came with its own database, its own data model, its own logic, and its own legacy code. To match Paycom’s single-database design, ADP would have to do something brutal: either rebuild the platform from scratch and migrate millions of customers, or attempt a multi-year integration effort of staggering complexity—with no guarantee it works.

That’s why the single database looks a lot like what Hamilton Helmer calls a cornered resource. It isn’t mysterious. Everyone can see why it’s valuable. But replicating it would require what one industry observer described as a “10-year suicide mission.”

And it wasn’t just hard to build. It was hard to protect.

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, the HCM industry consolidated in waves. Competitors bought their way into new modules, new verticals, new geographies. Paycom mostly sat out. Because every acquisition comes with a bill: a new codebase, a new data model, and—eventually—another seam in your product where errors can leak through. For Paycom, buying growth would have meant diluting the very thing that made it different.

That restraint shaped how the company moved upmarket. The first customers were small businesses, the ones willing to take a chance on an internet-native payroll provider. But as the platform matured, the “one record, one system” pitch started to resonate with larger organizations—especially the mid-market, where complexity is real but IT budgets and patience are limited.

Paycom has an estimated 6% market share in the midsize segment of 50 to 999 employees, and that segment makes up about three-quarters of its client base. More broadly, the mid-market—companies with roughly 50 to 5,000 employees—became Paycom’s sweet spot. They’re too big for duct-taped point solutions, but not always ready to take on enterprise-heavy systems. They need payroll, HR, time, benefits, and compliance to work together without turning HR into a data-entry job.

That strategy culminated in a milestone that, for most startups, is the finish line. For Paycom, it was more like a receipt.

On April 21, 2014, Paycom went public on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker PAYC. It priced 6,645,000 shares at $15 per share and raised about $69.1 million in net proceeds for the company. The offering price had been reduced, and when trading began, the stock opened at $17.90 and closed at $15.35. The debut carried a very public shrug from the market: why do we need another payroll stock?

But the fundamentals were already speaking for themselves. An analyst at Barclays said Paycom was disrupting payroll servicing with better technology and expected the company to grow quickly in the coming years, arguing the valuation looked low versus peers.

Looking at the architecture today, the real question isn’t whether a single database matters. It’s whether the gap it creates is getting smaller—or larger.

The case for “larger” is straightforward: as the industry piles on automation and AI, multi-database systems become a bigger liability, not a smaller one. You can’t automate cleanly on top of messy foundations. If your stack is stitched together, your “intelligence” is, too. Paycom’s bet is that the future belongs to the platform that doesn’t just display the data—but actually keeps it consistent everywhere it lives.

And that brings us to the next turn in the story: what happens when you build software that’s unified enough to stop depending on human cleanup.

V. The Golden Era: Sales, Scale, and Margins

From the IPO in 2014 through 2024, Paycom hit what every software company chases: a long, sustained run where the product worked, the market pulled, and the machine got faster with every rep you added. It went from being “that payroll company from Oklahoma” to a national force. And the engine behind it wasn’t a viral loop or a clever ad campaign. It was Chad Richison’s sales factory.

“We continue to experience success as a result of our disciplined sales office expansion strategy,” Richison said. “This strategy allows us to better develop our current and potential sales managers and provides a more solid foundation for future sales performance.”

Paycom’s expansion playbook was straightforward and repeatable. Pick a metro with enough business density to matter. Send in an experienced manager from an established office. Then hire a team of sales reps—often recent college grads with zero payroll background—and train them in the Paycom way. After that, it was sheer volume: call, demo, follow up, and keep showing prospects the same core promise. One system. One record. No duct-tape integrations. Less cleanup.

The company kept leaning on that direct sales approach for years, and it showed up in how aggressively it planted flags. In 2014, Paycom opened in places like Baltimore, Indianapolis, Philadelphia, Portland, and Silicon Valley. In 2015, it added Brooklyn, Cincinnati, Kansas City, Nashville, and Pittsburgh. The point wasn’t just growth—it was coverage. A territory-based sales force that could methodically work its way across the country.

That cadence didn’t stop. Paycom opened three new sales offices in January 2025, bringing the total to 57 outside sales teams.

And when Paycom opened three more offices in 2025, Providence became a small legend inside the company—hitting a million dollars in sales faster than any city Paycom had ever launched.

Here’s the compounding effect: payroll is one of the stickiest categories in enterprise software. Paycom reported an annual revenue retention rate of 90% as of December 31, 2024. That number reflects something simple and brutal about the category: switching payroll providers is open-heart surgery for a business. You have to migrate data, reconfigure rules, rebuild reporting, retrain admins, and then hope nothing breaks—because if anything breaks, it breaks in the one place employees notice immediately: their paychecks.

So once Paycom landed a customer, it usually kept them—often described as being above 92% in the mid-market segment. And that meant Paycom could spend aggressively to acquire customers, confident that the lifetime value on the other side of the sale would justify it.

The financial profile that emerged was exactly what public-market investors dream about: growth paired with real profitability. Since the 2014 IPO, Paycom delivered investors a return of over 1,800%, or about 43% annually. It consistently cleared the “Rule of 40,” not by trading margin for growth, but by getting both at the same time.

In 2024, revenue reached $1.883 billion, up 11% year-over-year. GAAP net income was $502 million, about 27% of revenue. Adjusted EBITDA was $775 million, about 41% of revenue.

Those are software-company margins—rare in general, and almost unheard of in an industry built on service bureaus and manual processing. Paycom also reported zero total debt. It was, by most measures, a machine in peak form.

But inside the customer experience, something wasn’t adding up.

Even with automation, even with a single database, HR managers were still buried. They were still doing endless data entry. Still correcting mistakes. Still acting like human middleware between employees and the system. Paycom had solved the integration problem. It hadn’t solved the ownership problem: who was responsible for the accuracy of the data in the first place?

That’s where the next idea came from, and it was almost uncomfortable in its simplicity. The people creating the data—employees—weren’t the ones verifying it. HR was stuck fixing what employees could have confirmed themselves.

What if you could cut out the middleman?

VI. The Innovator's Dilemma: The "Beti" Pivot

In July 2021, Paycom did something payroll companies aren’t supposed to do: it tried to make itself less necessary.

On July 6, 2021, Paycom launched Beti—the Better Employee Transaction Interface—positioning it as the industry’s first self-service payroll technology that allows employees to do their own payroll. The promise was simple: better accuracy, clearer oversight, and a smoother experience for both employers and employees on every payroll cycle.

“With Beti, employees do their own payroll,” Chad Richison said. “It should have always been this way, but the tech didn’t exist. Today it does, and employers and employees will win with it.”

That quote sounds like marketing until you realize how aggressively Beti flips the process.

In the old model, employees create the mess and HR cleans it up. Someone forgets to clock in. A reimbursement sits unapproved. A job change doesn’t get reflected in time. HR discovers the problem late—usually when they’re already trying to close payroll—and then scrambles to chase down the right person, correct the data, and hope nothing else breaks.

Beti moves the work to the source.

It self-starts each pay period and pulls live employee data that affects pay. It pushes notifications to employees and managers throughout the cycle about what’s missing or unresolved—things like a missed punch or an unapproved expense. And instead of waiting for payroll day to surface the damage, Beti identifies issues early and guides the employee to fix them before payroll is submitted.

So in practice, the “missing punch” scenario changes completely. The employee doesn’t get a surprise when the check arrives. They get a nudge mid-week, fix it themselves, and payroll closes without HR playing detective.

A commissioned Total Economic Impact study conducted by Forrester Consulting on behalf of Paycom said Beti cut payroll-processing labor by 90% for a composite organization, projecting nearly $3.8 million in savings over three years. The exact numbers matter less than the direction: Paycom wasn’t promising a slightly nicer interface. It was promising a different operating system for payroll.

And it was built on a philosophy Paycom had been circling for years: the person who creates the data should verify the data. With Beti, employees are doing their own payroll.

That should have been an unambiguous win. For customers, it was. For Paycom’s business model, it came with a trap.

Because Paycom—like virtually every payroll company—didn’t just make money on subscriptions. It also made money on what the industry calls “unscheduled revenue”: fees charged when payroll went wrong. Off-cycle runs. Manual corrections. Special checks. Extra service time. In a service-bureau world, errors aren’t just inevitable. They’re monetizable.

Beti wasn’t designed to generate more of that revenue. It was designed to destroy it.

That tradeoff became public in Q3 2023. Paycom reported its financial results and disclosed what the product was doing in the real world: clients were cutting back on certain services and purchases because Beti made them unnecessary. On the earnings call, CFO Craig Boelte explained that growth was being curbed by cannibalization.

Wall Street didn’t treat that as a product breakthrough. It treated it as a revenue problem.

On November 1, 2023, Paycom’s shares fell $94.28, a 38% drop, closing at $150.69. The quarter’s revenue was $406.3 million, below the forecast range of $410 million to $412 million, and the market response was swift and brutal.

Analysts raced to rewrite their models. After the Q3 2023 results, BMO Capital Markets cut its price target by more than 40%, from $320 to $190. Stifel Nicolaus downgraded the stock from “buy” to “hold” and reduced its target from $400 to $160.

A securities class action lawsuit followed. It alleged Paycom failed to adequately warn investors about the cannibalization risk—claiming the company misrepresented and concealed that Beti led to cannibalization of other services and revenues, and that as a result Paycom missed expected Q3 2023 revenue and would have to revise its FY 2023 outlook.

From a capital markets perspective, it was a crisis. From a strategy perspective, it was almost textbook.

This is Clayton Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma in the wild: the incumbent chooses to undercut its own high-margin, familiar revenue to pursue what it believes is the future. Beti’s adoption spread quickly across Paycom’s customer base—reaching roughly half of clients by early 2023—and as it did, customers increasingly skipped the add-on services that used to generate those one-off fees.

The philosophical argument is uncomfortable but clean. If your product depends on your customer failing—on errors, rework, and clean-up—you’re exposed. Somebody else can come along, eliminate the failure, and take the relationship. Better to cannibalize yourself than be cannibalized.

That’s the bet Paycom made.

Paycom has been a top revenue grower in the SaaS HCM industry, compounding sales at about 20% annually over five years. Even after the 2023 setback tied to Beti’s cannibalization, the company framed the move as positioning for the long run, with a 25% EBITDA margin and 8% projected growth in 2025.

For long-term investors, Beti is both the biggest risk and the biggest opportunity in the Paycom story. The risk is that Paycom permanently slowed its growth by eliminating a meaningful stream of revenue. The opportunity is that Beti becomes the industry standard—and that competitors, weighed down by multi-database architectures and service-driven economics, can’t replicate it cleanly.

Even amid slower growth, Paycom’s financial profile still reflected real software economics: an 86.17% gross profit margin and a forward free cash flow yield of 3.25%. Beti was initially dilutive to revenue per transaction. But strategically, it was Paycom trying to do what it’s always done: use architecture and product truth to force the category forward—even if the first punch lands on itself.

VII. Power Analysis: 7 Powers & 5 Forces

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

Cornered Resource: The Single Database Architecture

Paycom’s strongest advantage is also its least flashy: the foundation. Since 1998, Paycom built its HR and payroll tools in-house, inside one database. The modules don’t “connect” through exports and imports because they were never separate in the first place. They share the same employee record, which is what makes full-suite automation—and the ROI that comes with it—actually possible.

This is the kind of advantage that’s easy to admire and brutal to copy. Competitors can match features. They can’t match the underlying architecture without rebuilding their technology stacks, then migrating customers over without breaking payroll. That’s a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar project with no guarantee it works. In most cases, it’s not just hard. It’s strategically irrational.

Switching Costs: Open-Heart Surgery

Payroll may be the ultimate “don’t touch it if it’s working” system. The data is messy, compliance is unforgiving, and mistakes are immediately visible—because employees don’t get paid. That reality creates natural switching costs. Even when customers are frustrated, many decide the risk of disruption is worse than the pain of staying.

Counter-Positioning: Beti vs. Service Fees

Beti is Paycom’s clearest counter-positioning move. If Beti prevents errors, it prevents the off-cycle runs, manual fixes, and special checks that have historically generated fee revenue across the industry. Paycom chose to automate that work away.

For incumbents, copying that is difficult in two ways. First, many don’t have the architecture to make employee-driven, end-to-end automation clean. Second, even if they could ship something similar, it would attack their own high-margin service revenues. Beti doesn’t just compete with other products. It competes with the incentive structure of the legacy model.

Porter's 5 Forces

Rivalry: Intense but Segmented

HCM is crowded and competitive, with large players like ADP, Workday, Paychex, and Paylocity, plus newer entrants like Rippling. But the market is segmented by customer size. Workday is strongest in enterprise. ADP spans segments but is often seen as complex. Paylocity competes more directly with Paycom in the mid-market.

Paycom’s differentiation is its closed, internally built ecosystem: every module was built inside the same platform, which can mean a more unified system and less manual re-entry than “integrated” suites. That contrasts with competitors that lean more heavily on open architectures and third-party connections.

That said, Paycom’s anti-integration stance—limiting third-party systems feeding data into Paycom—creates a walled-off ecosystem. The upside is data integrity. The downside is that, as organizations scale and want more best-of-breed tools, those constraints can start to feel like a tradeoff.

Threat of New Entrants: Low

Payroll is a hard business to break into. Regulation is complex across states and localities, and trust is non-negotiable when you’re handling pay. On top of that, customer switching costs make it difficult for a new entrant to dislodge an incumbent once payroll is running.

Among newer threats, Rippling stands out as the most significant. It’s growing quickly and has pushed modern capabilities into the market, including no-code automation, an integration marketplace, and IT management tools.

Buyer Power: Moderate

Mid-market companies can negotiate on price, but they don’t have endless options if they want a truly unified HCM platform. The scarcity of alternatives with Paycom’s single-database architecture limits buyer leverage.

Supplier Power: Low

Paycom’s primary inputs are engineering talent and cloud infrastructure. Neither creates outsized supplier power in the way a single critical vendor might.

Threat of Substitutes: Emerging

The substitute threat is AI-driven automation. If AI can automate payroll work regardless of underlying architecture, Paycom’s single-database advantage could narrow. Paycom’s response has been to push AI into the product, including its AI engine, IWant, designed to provide fast access to employee data without users having to navigate or learn the software in depth.

VIII. The Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bear Case

Market Saturation and Growth Deceleration

For most of its public life, Paycom trained investors to expect something close to “up and to the right.” Lately, that slope has flattened. Revenue growth decelerated from the mid‑20s historically to roughly the high single digits at the midpoint of the company’s 2025 outlook.

The client base tells a similar story. As of December 31, 2024, Paycom reported 19,422 clients on a parent-company grouping basis—basically unchanged year over year. That raises the uncomfortable question: is Paycom starting to saturate its core mid-market sweet spot?

Competition from Modern Stack Players

If there’s a challenger with real momentum, it’s Rippling. It comes with modern architecture, aggressive pricing, and a strong automation narrative.

This is also where Paycom’s product philosophy cuts both ways. Paycom has long emphasized data integrity inside its own system, and that has meant a “walled city” approach—third-party systems generally can’t send data into Paycom. That can protect the single source of truth, but it can also limit what customers can automate across their broader stack. If a company wants end-to-end workflows that span multiple systems, Paycom’s approach can feel constraining.

CEO/Founder Concentration Risk

Paycom is still, in many ways, Chad Richison’s company. Through a dual-class structure and personal ownership, he controls the business and holds a large stake—about 14%. That alignment has been a feature, not a bug, for most of Paycom’s history. But it’s also concentration risk: the culture, strategy, and decision-making are deeply tied to one person.

Retention Trends

Paycom’s retention remains high, but the direction has not been flattering. Annual revenue retention was 94% in 2021, 91% in 2022, and 90% in 2023. That kind of gradual decline doesn’t prove anything on its own—but in a category built on stickiness, it’s the kind of metric you keep your eyes on.

The Bull Case

Beti as Industry Standard

The upside case starts with the simplest thought: what if Beti is the future of payroll?

If employee-driven payroll becomes the expected default, Paycom has a multi-year head start—and it has already done the painful part: absorbing the revenue cannibalization that comes from eliminating errors. Beti has been positioned as a step-change in efficiency, including findings from a Forrester Consulting Total Economic Impact study commissioned by Paycom that said Beti cut payroll-processing labor by 90%. And if competitors try to match that experience, they run into the same dilemma Paycom chose to walk into: you can’t eliminate payroll mistakes without also eliminating a bunch of the fees tied to fixing them.

Margin Expansion Potential

Beti doesn’t just change the customer workflow. It changes Paycom’s cost structure.

As more payroll work shifts away from HR and away from Paycom’s own service teams, service costs should fall. Even with the near-term growth slowdown, Paycom continued to project strong profitability, including an adjusted EBITDA margin of roughly 43% at the midpoint for 2025. If automation keeps eating the manual work, there’s a plausible path to even higher margins over time.

International Expansion

Paycom’s core story has been built in the U.S., but the company has begun expanding its footprint with Global HCM and native payroll processing in Mexico and Canada. International remains a much less penetrated opportunity relative to the domestic business.

AI as Architecture Amplifier

There’s also a world where AI doesn’t weaken Paycom’s moat—it widens it.

If the future of HCM is command-driven interfaces and AI layers that pull answers instantly from workforce data, the quality of the underlying data matters even more. In a single-database system, the AI can operate on one consistent record. In multi-database systems, you run into a familiar problem: garbage in, garbage out. Paycom has been pushing AI into its product, including its AI engine, IWant, aimed at giving users faster access to employee data without having to learn every corner of the software.

Key KPIs to Track

For investors following Paycom, three metrics matter most:

-

Annual Revenue Retention Rate: About 90%. This is the clearest indicator of whether Paycom’s “open-heart surgery” switching costs are holding—and whether competition is starting to bite.

-

Recurring Revenue Growth Rate: Around 10% year over year for 2025 in recurring and other revenue. This is the core engine of the business, separate from float income.

-

Adjusted EBITDA Margin: Targeting roughly 43%. This is the scoreboard for operational efficiency—and a proxy for whether automation is truly taking cost out of the system.

IX. Conclusion & Lessons

The Paycom story lands with three lessons that travel well beyond payroll.

Lesson 1: Technical Debt is Strategy

Most companies in payroll and HR tech grew the “normal” way: they bought adjacent products, stitched them together, and told customers it was integrated. The hidden bill came due later, in the form of messy data handoffs, duplicated records, and endless reconciliation.

Paycom took the harder path. It built, module by module, inside a single database, and largely avoided acquisition-driven sprawl. Twenty-five years later, that discipline isn’t just a clean codebase. It’s a structural advantage—because the competitors trying to match the experience aren’t copying features, they’re fighting their own foundations.

Lesson 2: Cannibalize Yourself

Beti is a reminder of a brutal truth: if you make money when your customer makes mistakes, you’re exposed. Someone will eventually show up with a better way—one that makes the errors disappear—and the fees disappear with them.

Paycom chose to be that someone, even though it meant blowing a hole in a revenue stream Wall Street had been happily modeling. The market response was immediate and punishing: a 38% one-day stock drop, lawsuits, and a wave of analyst skepticism. But strategically, it was the cleanest move available. Better to take the hit on your own terms than cling to a model built on customer pain and wait to be forced into it.

Lesson 3: Architecture Determines Destiny

Beti didn’t come out of nowhere. It’s downstream of the most important decision Paycom ever made: building on a single database back in 1998.

Switching costs, automation, employee self-service, fewer errors—those aren’t just “good product.” They’re what becomes possible when the underlying system is unified enough to make the employee record the truth everywhere, all the time. In software, features are easy to demo and easy to copy. Architecture is neither.

Is Paycom a Legacy Company or a Pioneer?

That’s the real question investors are left with.

The bear case says Paycom is maturing into saturation, and modern competitors—especially Rippling—are applying pressure just as growth slows. The bull case says Paycom is early to a new default: self-driving payroll, where the employee owns the data and the system enforces correctness before the money moves.

What makes it complicated is that both can look true at the same time. Paycom’s stock fell more than 70% from its 2021 peak. It also remained profitable, operating in a large and still-growing market. The share price dropped back to levels not seen since 2019, even though the business became materially larger and more profitable in the years since.

Valuation alone won’t settle the debate. Whether the current price is a gift or a trap hinges on the same thing that caused the selloff in the first place: the Beti pivot. If Beti becomes the standard workflow for payroll, this era will look like the uncomfortable transition period before the payoff. If competitors match the experience without suffering the same economics, Paycom may have permanently traded away growth for a feature others can neutralize.

What’s certain is that Paycom is still in the middle of its most consequential bet. It has wagered the future of the business on a philosophy—the person who creates the data should verify the data—that runs directly against the old service-bureau world. The next few years will decide whether that choice becomes Chad Richison’s defining triumph, or the moment Paycom gave up too much of what made the machine so powerful.

X. Outro

Further Reading:

- The Innovator's Dilemma by Clayton Christensen — The classic on why great companies get disrupted, and why the hardest move is often cannibalizing your own best business.

- 7 Powers by Hamilton Helmer — A clear framework for spotting what actually makes an advantage durable.

- Competitive Strategy by Michael Porter — The foundational toolkit for understanding industry structure, rivalry, and where profits come from.

Sources:

Paycom SEC filings, investor presentations, and earnings call transcripts; Forrester Consulting Total Economic Impact studies; Paycom press releases; industry publications including HR Executive, Business News Daily, and TechRepublic; analyst reports from Barclays, Stifel, and BMO Capital Markets; University of Central Oklahoma Athletics archives; National Wrestling Hall of Fame records.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music