Par Pacific Holdings: From Distressed Debt Play to Hawaii's Energy Lifeline

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

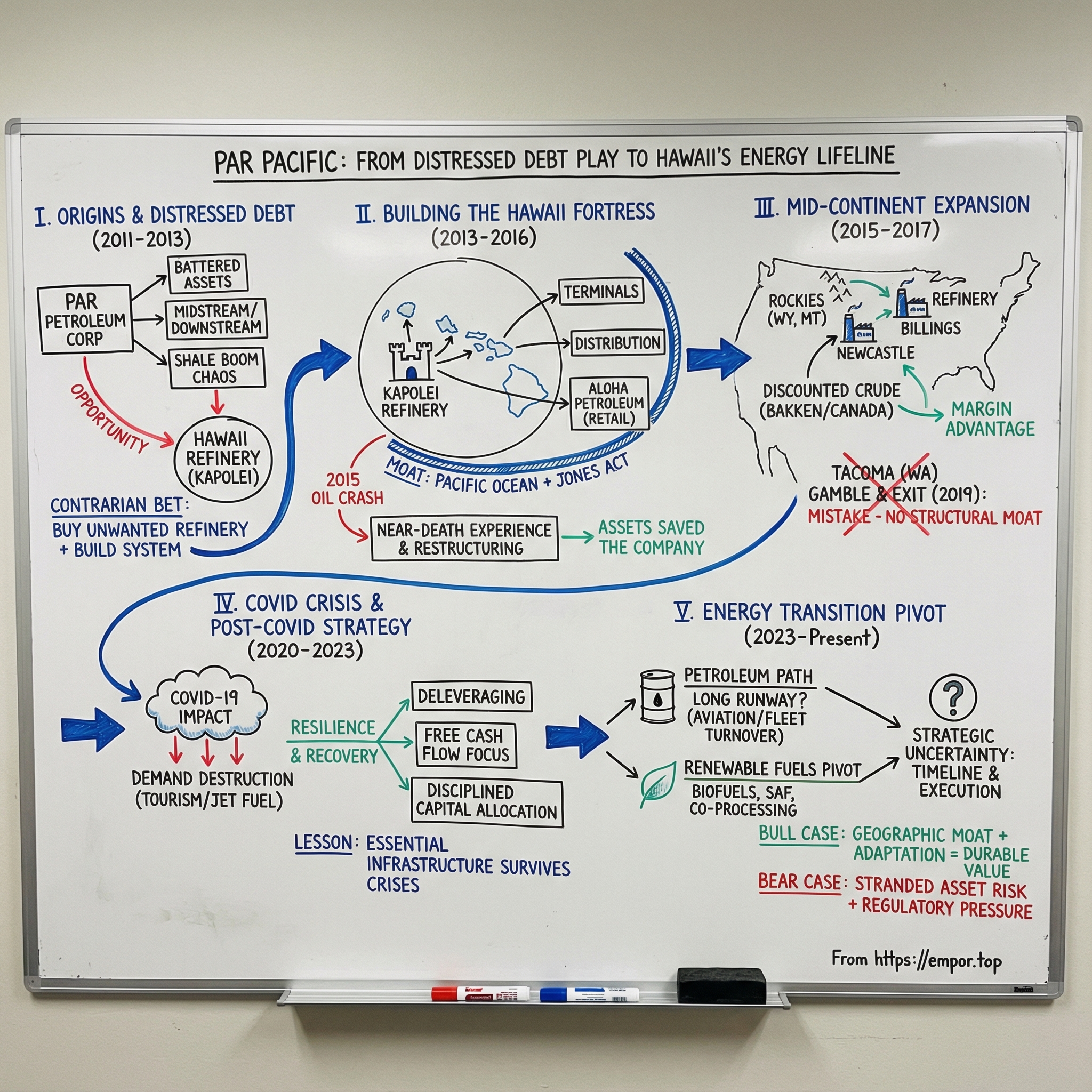

Picture this: it’s 2013, and the refining business is in full retreat. Big oil is shedding refineries as fast as it can. Margins are thin, the cycle looks ugly, and the Wall Street consensus is simple: refining is a capital-intensive headache with shrinking upside and growing regulatory pain. If you don’t have a special edge, you get out.

Now drop a contrarian into that moment and have him say, “I’m going to buy Hawaii’s only refinery. And then I’m going to build the rest of the fuel system around it.”

That’s Par Pacific. On paper, it sounds like financial self-harm. In practice, it turned into one of the more interesting infrastructure stories in modern American business: a lesson in distressed-asset turnarounds, the power of geography, and how something that looks like a “dinosaur” from 3,000 miles away can be a lifeline up close.

Par Pacific Holdings sits in a weird, easy-to-miss corner of U.S. energy. It’s not Exxon. It’s not Chevron. It’s a mid-sized independent that evolved from a distressed-asset aggregator into Hawaii’s primary fuel supplier, while also building a second leg of advantaged refining operations in the Rockies. Today, it controls Hawaii’s sole remaining refinery, runs a network of gas stations across the islands, and operates refineries in Wyoming and Montana. It’s roughly a three billion dollar enterprise that many investors barely recognize—and that obscurity is part of why the story is so compelling.

Here are the questions we’re going to chase: How did a company built around battered, unwanted assets end up owning an irreplaceable piece of Hawaii’s critical infrastructure? What does it actually mean to have a geographic monopoly in an essential commodity like fuel? And in a world racing toward electrification and lower-carbon energy, is Par Pacific a durable transition story—or the last owner standing in a business that’s slowly being legislated out of existence?

This is a story about private equity instincts colliding with real-world infrastructure. It’s about doubling down when everyone else is running for the exits—and also about learning when to admit a mistake and walk away. Because in refining, the line between “brilliant contrarian” and “blown-up balance sheet” is thin, and Par Pacific has spent its entire life walking it.

II. Setting the Stage: The Refining Business & Why Geography Matters

Let’s say the quiet part out loud: oil refining is a lousy business most of the time. It’s capital-intensive, brutally cyclical, and commoditized at both ends. Refiners buy crude at market prices, run it through giant machines that never stop breaking, and then sell gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel into markets where buyers can usually shop around. The profit you get for all that work is often a thin sliver—and that sliver can disappear fast.

The whole game is the “crack spread,” basically the gap between what crude costs and what refined products sell for. When the spread is wide, refiners look like geniuses. When it collapses, the same plants turn into cash incinerators. And because refineries cost a fortune to build and require constant upkeep just to stay safe and compliant, you don’t have the luxury of pausing the business until conditions improve. Shutting down is expensive. Restarting is expensive. Staying open is expensive. Refining is a treadmill with a mortgage.

Then there’s the slow squeeze from regulation and politics. Environmental standards tighten. Compliance costs rise. Carbon rules hang over every long-term plan. And over the horizon, the energy transition keeps getting louder: electric vehicles, renewable fuels, efficiency mandates. So it’s not surprising that, in the years leading up to Par’s big move, major oil companies were unloading refineries and shrinking their exposure. They were deciding this wasn’t where they wanted to fight.

But here’s the twist: in refining, the average is awful—and the exceptions are everything. A refinery with the right geography isn’t just a plant. It’s a toll booth.

On the mainland, most refineries are plugged into a massive web of pipelines, terminals, rail, and trucks. That connectivity is great for the consumer and terrible for the refiner: if you try to charge too much, supply flows in from somewhere else. Gulf Coast barrels can chase East Coast demand. Mid-Continent barrels can leak into neighboring states. Competition is constant because the logistics system makes competition possible.

Now put that same product on an island chain in the middle of the Pacific.

Hawaii is separated from the mainland by open ocean and physics. There are no pipelines across the sea. No rail shortcuts. No “we’ll just truck it in from the next state.” If Hawaii needs fuel, it has only two realistic choices: refine locally, or import by tanker.

And then the Jones Act steps onto the stage.

The Jones Act is a 1920 law that requires goods shipped between U.S. ports to move on vessels that are American-built, American-owned, and American-crewed. It was designed for national security. In practice, it makes domestic ocean shipping far more expensive than using international carriers. For Hawaii, that means bringing fuel from the U.S. mainland carries a built-in cost penalty—before you even talk about the price of crude.

That cost penalty functions like protection. If you’re running a refinery in Hawaii, you’re not competing on equal terms with a refinery in California. The mainland option arrives with an extra layer of shipping cost baked in. Geography and regulation combine into something rare in refining: a structural moat.

This is why Hawaii is different. It’s not that Hawaiian refiners have secret technology or superior scale. It’s that the market is captive, the alternatives are limited, and the “import it instead” option is inherently expensive.

A version of that advantage shows up again in the Rockies, just through a different mechanism. In places like Wyoming and Montana, refineries can sit close to sources of crude that don’t always have easy access to coastal markets. When pipelines bottleneck and transportation gets constrained, local crude can trade at discounts versus big benchmarks. If you own a refinery positioned to buy those discounted barrels, you can earn margins that are hard for coastal refiners to match.

This is the lens you need for Par Pacific. The company didn’t win by out-muscling ExxonMobil or out-engineering Chevron. It won by planting flags in places where the map itself creates the advantage—and then building control over the surrounding system so that advantage sticks.

III. The Petrohawk Origins & Distressed Birth (2011-2013)

Par Pacific’s story doesn’t start with refineries. It starts with shale.

In 2011, at the height of the American shale boom, Par Petroleum Corporation—the predecessor to today’s Par Pacific—was formed with a very different plan: go hunting in the wreckage and build a portfolio of overlooked energy infrastructure. The shale revolution was pumping out new barrels faster than the country could move them. Pipelines were late. Storage was tight. Processing and logistics were playing catch-up. That mismatch created chaos… and in chaos, prices get weird.

Par’s initial strategy was to aggregate distressed assets across the midstream and downstream world—pipelines, terminals, and processing facilities that bigger companies were happy to label “non-core” while they chased flashier upstream returns. The problem was that the sellers were motivated, but capital was still cautious. The financial crisis was fresh, and buying distressed assets always looks smarter in hindsight than it feels in the moment.

The shale context matters because it explains the opportunity set. In the Bakken, light sweet crude was surging out of North Dakota, but the infrastructure wasn’t there to carry it. Rail became the workaround, turning transportation, storage, and processing into profit centers for whoever could solve the bottleneck. Similar dynamics played out across the Permian, the Eagle Ford, and other shale basins. If you were nimble and willing to get your hands dirty, you could buy useful assets at prices that assumed the worst.

Par’s early team came out of that world—energy infrastructure, distressed investing, operational turnarounds. They weren’t trying to outscale the majors. They were trying to outmaneuver them: buy what the big guys didn’t want to bother with, fix it, and let geography and logistics do the rest.

Then, in 2013, the defining opportunity showed up.

Tesoro Corporation announced it was selling its Kapolei refinery on Oahu. It was a relatively small plant by mainland standards—about 94,000 barrels a day—but in Hawaii it was the center of gravity for the entire fuel system. Tesoro was consolidating around its West Coast footprint. Hawaii, with its distance, complexity, and smaller scale, looked like a distraction—an operation you had to manage across an ocean from a headquarters in San Antonio.

Par looked at the exact same asset and saw something else entirely. Not just a refinery, but Hawaii’s only refinery. A piece of infrastructure protected by the Pacific Ocean and a century-old shipping law. A plant that sat inside a captive market where “just bring it in from somewhere else” isn’t a casual decision—it’s an expensive, logistically heavy commitment.

The logic was simple and deeply contrarian. Yes, refining was unpopular. Yes, margins could be punishing. Yes, the energy transition was getting louder. But Hawaii was still going to need fuel. Planes would still need jet fuel. Cars would still need gasoline. Ships would still need diesel. And whether the supply came from local refining or imports, someone would earn the spread for keeping the islands moving.

Par closed the acquisition in September 2013, paying about three hundred million dollars for Kapolei and associated assets—an “out of favor” price in an “out of favor” sector. And that was the point. Building something similar from scratch would cost billions, if it could be permitted at all. Par wasn’t paying replacement cost. It was paying distressed-market reality, and betting it could turn that gap into a durable advantage.

At the time, it was easy to frame the move as either brilliant or reckless. Par was smaller, more leveraged, and largely unproven as a refiner. The majors were heading for the exits. The obvious question was: what did these guys see that Tesoro didn’t?

The answer was that Par wasn’t valuing Kapolei like a generic refinery. It was valuing it like infrastructure with a moat—where the map, the law, and the logistics stack the odds in your favor.

The bet was made. Now Par had to operate it, integrate it, and build the rest of the system around it.

IV. Building the Hawaii Fortress (2013-2016)

Buying Kapolei was the entry ticket. The real plan was bigger: don’t just own the refinery—own the system around it. Control the critical links that connect crude oil to a jet engine on the tarmac, a tanker at the harbor, and a driver pulling up to a pump.

So Par didn’t stop at the refinery gates. The initial deal came with terminal infrastructure too: the storage tanks and distribution facilities that move finished fuel from the refinery into the rest of the islands’ economy. In Hawaii, those terminals aren’t just “nice to have.” They’re the choke points. They determine who can reliably supply airports, harbors, and wholesale customers, and when.

Then Par went after the part of the chain that touches customers directly.

Just months after closing on Kapolei, Par announced it would acquire Aloha Petroleum, one of the largest fuel distributors and retail station operators in the state. Overnight, Par wasn’t only making fuel; it was also selling it through a network of branded stations, convenience stores, and commercial supply contracts spread across the islands.

The logic here is simple, and powerful. An integrated fuel business can keep making money even when one segment is getting squeezed. If wholesale margins are ugly, retail can help cushion it. If retail gets competitive, the refinery and terminals still matter. Instead of living and dying by one thin slice of the profit pool, Par put itself in position to earn something at every step.

Just as important, retail and distribution gave Par a real-time view of the market. When you’re supplying a remote island chain, you don’t get to be sloppy with inventory. You want to know what’s moving, where it’s moving, and how fast—so you can plan shipments, manage storage, and keep the whole system balanced. Owning the downstream footprint made that feedback loop tighter.

And the market itself was unusually attractive for a refiner. Hawaii’s roughly 1.4 million residents were a captive customer base with limited alternatives. Tourism layered on even more demand, from rental cars to tour buses to inter-island flights. Add in the military presence—another large, consistent consumer of fuel—and you had an island economy that simply could not opt out of petroleum overnight.

But stitching all of this together wasn’t a plug-and-play exercise. Running a refinery is one kind of operational discipline. Running retail and distribution is another. And refineries have an additional cruelty baked into the business: turnarounds. Those planned shutdowns for maintenance and upgrades are necessary, expensive, and disruptive. When the refinery stops, the ripple effects don’t stay inside the fence line—they echo through terminals, distribution schedules, and customer commitments. In a place like Hawaii, where relationships are tight and logistics are unforgiving, Par had to learn fast how to be both a newcomer and an essential service provider.

Then the macro world turned on them.

In 2015, oil prices collapsed. The market went from over a hundred dollars a barrel to levels that made entire parts of the industry look uninvestable. The shale boom that created so much opportunity also created a brutal reality: abundance can crush everyone’s economics at once.

For Par, it hit at the worst possible time. The company had taken on debt to buy and build out its Hawaii position. When the downturn arrived, cash flow tightened, covenants got closer, and the fear moved from “this is a bad year” to “does this company make it?”

This was Par’s near-death experience. Management worked to renegotiate debt, cut costs, and protect liquidity. The Hawaii assets still mattered—fuel demand didn’t disappear, and the geographic moat didn’t evaporate—but the balance sheet was under real strain. This wasn’t a theoretical risk. It was existential.

What ultimately kept Par alive was the difference between a bad capital structure and great assets. Lenders could do the math: Hawaii wasn’t going to stop needing fuel, and Par controlled infrastructure that couldn’t be easily replaced. A foreclosure wouldn’t solve the underlying reality; it would just hand the same problem to a new owner. Working with Par, restructuring obligations, and waiting for conditions to improve was the pragmatic choice.

Par came out of that period with a scar and a lesson. Geographic advantage doesn’t just protect you from competitors—it can buy you time when the financial world is closing in.

By late 2016, the panic had eased. Oil prices stabilized, margins improved, and Par was still standing—with its Hawaii fortress intact.

V. The Wyoming Pivot & Mid-Continent Expansion (2015-2017)

Even while Par was fighting for survival in the 2015 crash, management was already looking for a second pillar. Hawaii was proving the big idea—geography can turn a brutal commodity business into something closer to infrastructure. The question was whether Par could find another place where the map did the heavy lifting.

They found it in Wyoming.

In 2015, Par bought a small refinery in Newcastle, in the northeastern corner of the state. It was tiny compared to Kapolei—roughly fourteen thousand barrels per day—but size wasn’t the point. Positioning was.

Newcastle sat in the orbit of multiple crude supply streams. Bakken barrels from North Dakota, Canadian crude moving through regional systems, and local Wyoming production all showed up in the neighborhood. And because this crude was landlocked—far from the coasts and, at times, trapped behind pipeline constraints—it could trade at discounts to the big benchmark prices everyone quotes on TV. For a refiner, that discount is oxygen. Buy cheaper feedstock, sell finished products into nearby markets, and you’ve built a margin buffer that coastal refiners often don’t have.

It was the same Par playbook as Hawaii, just with different physics. In Hawaii, the moat came from ocean distance and the Jones Act making imports structurally expensive. In Wyoming, the advantage came from landlocked geography: bottlenecks that punished producers could benefit the local refinery willing and able to take the barrels.

Around the same time, Par also invested in Laramie Energy, stepping upstream into natural gas production. It added commodity exposure and offered another way to connect supply with Par’s broader operating footprint.

Zoom out and a new shape started to emerge—a barbell strategy. On one side: Hawaii, a protected, captive market where Par controlled the critical infrastructure. On the other: the Mid-Continent, where the right refinery could win by sitting close to discounted crude and selling into regional demand.

That diversification was comforting after Hawaii’s near-death experience. But it also came with a cost. These were very different businesses operating under very different conditions, separated by thousands of miles. They demanded different operational muscle, different capital decisions, and—most scarce of all—more management attention.

Still, in 2015 and 2016, it felt like the responsible move. Concentration in Hawaii had almost broken the company. A second leg meant Par wouldn’t live or die on one set of market dynamics.

The barbell was taking shape. And Par wasn’t done adding weight to it.

VI. The Washington State Gamble & Overextension (2016-2019)

Success has a way of making the next bet feel easier. In Par’s case, it also made the next bet bigger. In 2016, the company made what it would later come to view as its most consequential strategic mistake: buying the Tacoma, Washington refinery from U.S. Oil & Refining.

On the whiteboard, the deal had a clean story. Tacoma put Par in the Pacific Northwest, with access to Puget Sound markets and nearby demand centers. And management believed West Coast refining had structural tailwinds: capacity had been shrinking for years as regulations tightened and older plants became uneconomic. With limited new refineries being built, scarcity should have helped whoever remained.

It also looked familiar. Buy a distressed asset. Put operational muscle into it. Let geography do the rest.

But Tacoma wasn’t Hawaii.

Almost immediately, the refinery demanded more attention—and more money—than expected. Operational issues turned into maintenance needs, and maintenance needs turned into capital spending. Instead of plugging neatly into Par’s existing footprint, Tacoma added another complicated operating system, another set of constraints, and another set of problems to solve across thousands of miles.

At the same time, the market didn’t cooperate. Margins in the Pacific Northwest tightened, and cash flow got squeezed. And unlike Hawaii—where the ocean and the Jones Act combine into real protection—Tacoma sat in a region where alternative supply could still show up. Rail and coastal shipping meant competition was real, and the “moat” Par thought it was buying just wasn’t as deep.

Then there was the timing. The acquisition also added leverage when Par could least afford it. The company had only recently staggered out of the 2015 crash. Taking on more debt to fund a tougher-than-advertised turnaround pushed the balance sheet back toward uncomfortable territory.

You could see the strain in the organization. Management turnover during this stretch mirrored the broader reality: Par had started with a sharp thesis—find places where geography turns energy into infrastructure—and now it was drifting into expansion that was more opportunistic than coherent. Tacoma was a refinery with real assets, but it didn’t have the structural protections that made Hawaii special.

By 2018 and 2019, the verdict was hard to avoid. Tacoma wasn’t going to earn the returns that would justify the time, capital, and balance sheet risk it demanded. Fixing it would likely take years, and even then the payoff was uncertain. Meanwhile, the leverage burden limited Par’s flexibility—whether that meant pursuing better opportunities or simply strengthening the company.

So Par did the thing that separates survivors from cautionary tales: it cut the cord. In 2019, Par sold the Tacoma refinery to HollyFrontier and exited an asset that had absorbed three years of management attention and financial resources without delivering strategic value.

The sale wasn’t just a financial decision. It was a cultural reset. Par was publicly admitting the thesis had been wrong. The Hawaii playbook—geographic moat plus control of the surrounding system—didn’t automatically copy and paste onto the mainland. And sometimes an asset is cheap because it deserves to be.

From that point forward, capital allocation discipline stopped being a slogan and became a necessity. Not every distressed refinery was worth buying. Not every “good location” was a durable advantage. Knowing when to walk away mattered as much as knowing when to pounce.

Par came out of Tacoma bruised, but clearer-eyed. Hawaii was still the crown jewel. Wyoming was still the second leg. And now the company had a sharper understanding of what its competitive advantages actually were—and what they weren’t.

VII. COVID, Demand Destruction & The 2020 Crisis

If 2015 was Par’s near-death experience, COVID was the moment the heart monitor flatlined—and the company had to figure out, in real time, whether its Hawaii fortress was actually a fortress, or just a beautiful trap.

In March 2020, the world slammed on the brakes. Air travel collapsed. Hawaii’s tourism economy, which had been bringing in more than ten million visitors a year, effectively shut down. Hotels went dark. Rental cars sat idle. Flights were canceled. And jet fuel demand—the highest-value product in Par’s Hawaii mix—fell off a cliff.

This was the vulnerability at the center of the entire Hawaii strategy. Kapolei wasn’t just “a refinery on an island.” It had been tuned to serve Honolulu’s airport, military demand, and inter-island aviation. When planes stopped flying, the economics didn’t just get worse. The margin structure that supported the operation broke.

Par moved fast. It curtailed refinery operations. It reduced its workforce. It cut discretionary spending to the bone. And then it went to the one stakeholder group that ultimately decides whether leveraged commodity businesses live or die: lenders. What followed weren’t routine discussions about terms and flexibility. They were survival talks. Par needed covenant relief and breathing room just to stay standing.

Hawaii, meanwhile, had its own problem to solve. If the state’s only refinery shut down, the islands would be forced into full import dependence at the exact moment global logistics were getting messy and unpredictable. That’s how you get shortages and price spikes, fast. Whatever Kapolei was earning in the short run, its existence mattered.

That reality shaped the outcome. Par’s lenders agreed to modified terms—a grace period that bought time—because the alternative was worse. The bet was simple: tourism would eventually come back, flying would resume, and refining economics would normalize. Par made the same bet, keeping the core capability intact while stripping everything else down to essentials.

Then came the waiting. Summer 2020 brought flickers of reopening, followed by new waves and fresh uncertainty. Fall arrived with no vaccine yet. Par ran lean, guarded liquidity, and tried to survive a downturn where the timing of the recovery was unknowable.

When vaccines arrived, the story snapped into a new chapter. By spring 2021, inoculation campaigns accelerated, restrictions began to lift, and travel demand surged. Hawaii came roaring back. Planes filled. Hotels reopened. Jet fuel demand returned.

Across the industry, margins rebounded sharply as demand recovered into a supply base that had been constrained by shutdowns and underinvestment. For refiners that made it through 2020, the cash flow reversal was dramatic—whiplash after a year that had felt existential.

Par didn’t come out of COVID thinking refining had gotten easier. It came out with something more valuable: proof that its core asset wasn’t optional. Hawaii’s fuel system was essential, hard to replace, and therefore worth supporting through crisis. The same geography that protected Kapolei in normal times also mattered when the world broke—because lenders and policymakers understood that letting the refinery fail could create a bigger emergency than keeping it alive.

It also left Par with a hardened view of risk. Two existential shocks in five years was enough. The company’s next chapter would be built around discipline: fewer distractions, more balance sheet resilience, and a tighter focus on assets where Par could clearly explain why it deserved to win.

VIII. The Billings Acquisition & Post-COVID Strategy (2021-2023)

The post-COVID refining boom created a strange reversal. Par Pacific—an operator that had been fighting for oxygen just eighteen months earlier—was suddenly throwing off real free cash flow. And with that came a question it hadn’t been able to ask in years: do we just repair the balance sheet, or do we press the advantage?

In 2022, Par made its answer clear by buying the Billings, Montana refinery from Calumet Specialty Products. It wasn’t a random land grab. It was a swing back toward Par’s original idea: if you can’t win in refining with scale, win with positioning. The Billings plant ran at roughly sixty-five thousand barrels per day, putting it in the same weight class as Hawaii—and far bigger than Newcastle.

The appeal was the map. Billings sits where discounted crude can reliably find a home. On one side: Canadian heavy oil. On the other: Bakken light crude. Both have historically traded below coastal benchmarks, especially when transportation gets tight. With the right pipeline access, a refinery there can capture that gap and sell into regional markets across Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakotas.

But buying another refinery right after a crisis comes with a familiar trap: you can improve the portfolio and wreck the balance sheet at the same time. Par tried to avoid that by structuring the deal carefully, using a mix of existing cash flow, new debt facilities, and other financing to get the transaction done while still pushing overall leverage down. The point wasn’t growth at any cost. It was growth that didn’t undo the hard-earned stability coming out of 2020.

Once Billings was in the fold, Par went back to what it had become good at: the unglamorous mechanics that make a refinery consistently cash-flow positive. Improving utilization, tightening turnaround execution, and squeezing smarter economics out of procurement. The three refineries shared operating practices and lessons learned, creating the kind of modest but meaningful gains that rarely make headlines, but show up in margins.

The same discipline showed up across the rest of the portfolio. Par leaned into what fit its advantaged-geography thesis and moved away from what didn’t. Capital allocation centered on keeping the core facilities healthy, paying down debt, and buying back shares when management believed the market was mispricing the business.

What emerged was a new playbook with three simple priorities: generate free cash flow, reduce leverage, and concentrate investment in assets where Par could clearly explain its edge. The company that had chased Tacoma was gone. In its place was a tighter, more focused operator—one trying to behave like an infrastructure owner in a commodity world.

By 2023, Par looked fundamentally different from the version that had nearly failed in 2015 and again in 2020. Leverage was down. Cash generation was strong. And the portfolio finally made strategic sense: Hawaii’s protected island market, advantaged Rocky Mountain refining in Wyoming and Montana, and the retail distribution network that connected barrels to end customers.

But even as Par was getting its footing, a bigger question was gathering force—one that could eventually rewrite the economics of every refinery it owned.

IX. The Energy Transition Question & Renewable Fuels Pivot (2023-Present)

The next threat to Par Pacific isn’t the usual refining villain—a commodity crash, a bad turnaround, a sudden demand shock. It’s simpler, and scarier: the possibility that the core products Par makes steadily lose their place in the economy.

Electric vehicles have moved from novelty to mainstream momentum. Sustainable aviation fuel and renewable diesel are pulling in capital, headlines, and policy support. And governments aren’t being subtle about the direction they want transportation to go: less petroleum, more low-carbon.

In Hawaii, that pressure is concentrated. The state has set some of the most ambitious clean energy goals in the country, including one hundred percent renewable electricity and steep cuts to transportation emissions. It’s a place with real environmental urgency, and a political culture that’s more willing than most to use mandates and incentives to push change.

For Par, that creates an uncomfortable irony. The same isolation that made Hawaii such an attractive refining market can also trap you. If demand for petroleum shrinks quickly, Par can’t just “send barrels somewhere else.” There is no nearby alternative market. The moat that kept competitors out could also keep Par boxed in.

So management’s message has been adaptation, not denial. Par has been investing in renewable diesel capabilities and looking at how far it can push its existing infrastructure toward biofuels. The company has also been in discussions around sustainable aviation fuel partnerships—because if there’s one category where liquid fuels likely remain essential for a long time, it’s aviation.

One practical bridge is biofuel co-processing: running renewable feedstocks through parts of an existing refinery alongside petroleum inputs. It’s not a magic wand, but it’s a pathway that tries to reuse what Par already owns—equipment, logistics, and operating know-how—instead of betting the company on entirely new facilities.

The competitive picture gets trickier here too. If renewable fuels become the preferred product in Hawaii, mainland producers could try to ship them in and compete—something Par’s petroleum position historically didn’t face in the same way. The Jones Act still shapes the economics of getting anything from the U.S. mainland to the islands, but renewable fuels don’t map perfectly onto the old petroleum playbook. The incentives, credits, and supply chains are different, and that can change the math.

Which is why capital allocation is suddenly loaded with long-term consequences. Money spent maintaining petroleum capacity is, implicitly, a bet that demand holds up longer than critics think. Money spent on renewables is a bet that policy, technology, and customer adoption will arrive at scale—and that Par can earn a return during the transition, not just participate in it.

Lately, that’s translated into joint venture conversations with renewable fuel specialists, feasibility work on conversions and upgrades, and ongoing dialogue with Hawaii regulators about a transition path that lowers emissions without putting the state’s fuel security at risk.

The timeline is the whole game. Vehicle fleets turn over slowly; even aggressive EV adoption takes years to materially reshape gasoline demand, and decades to fully replace what’s already on the road. Aviation has fewer substitutes, which likely stretches liquid-fuel demand further out. The direction seems clear. The pace is the uncertainty.

And that’s why this chapter matters. Par has already survived the kinds of crises that kill most refiners. But this is different. This isn’t about enduring a bad year. It’s about whether Par can evolve fast enough to keep its role as Hawaii’s energy lifeline—or whether, years from now, Kapolei becomes a case study in what happens when a perfect geographic advantage meets a shifting world.

X. The Business Model Deep Dive: How Par Actually Makes Money

To really understand Par Pacific, you have to get comfortable with an odd truth about refining: the product is basically a commodity, but the profits aren’t. The money shows up in the gaps—between crude and products, between one geography and another, and between the operator that controls the chokepoints and the one that doesn’t.

At the simplest level, Par is a crack spread business. It buys crude oil at market prices, runs it through refineries, and sells gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel at market-linked prices. The business lives on the spread between what goes in and what comes out. When that spread is healthy, refiners print cash. When it isn’t, they burn it.

But crack spreads aren’t one universal number. They swing wildly by region and by year, because local competition, local rules, and local logistics all matter. The Gulf Coast is the most competitive neighborhood in America, and that tends to compress margins. The West Coast often earns premiums because of tight capacity and unique fuel specifications. And then there’s Par’s best asset, which doesn’t fit neatly into either bucket.

Hawaii is its own category.

In Hawaii, the crack spread isn’t just about commodity pricing. It also includes a logistics premium created by isolation. If someone wants to compete with local supply, they have to move product across the ocean—and if that supply is coming from the U.S. mainland, Jones Act shipping requirements stack extra cost into every delivered barrel. That doesn’t make Par invincible, but it does create structural protection that most mainland refiners simply don’t have.

On top of that, product mix matters. In Hawaii, jet fuel has historically been a more valuable part of the barrel than it is for many inland refiners, because the islands’ fuel demand isn’t just drivers filling up at the pump. It’s aircraft, tourism, and a large military presence. Demand also moves with the travel calendar: peak seasons lift volumes, while shoulder periods soften them. Par feels that rhythm in real time.

The Rockies play by different rules.

In Wyoming and Montana, Par’s advantage is less about being able to charge more for finished products and more about being able to buy crude at a better price. Landlocked barrels can trade at discounts when transportation gets tight and pipelines bottleneck. When that happens, Par’s refineries can capture the value on the input side—cheaper feedstock in, competitively priced products out. Same crack spread concept, different engine.

All of that sits on top of the less glamorous reality: refineries are maintenance machines. A big chunk of capital spending isn’t about growth at all. It’s about staying safe, compliant, and reliable—turnarounds, equipment replacements, and regulatory investments that keep the plant running. Growth capital is the optional stuff: expansions, efficiency projects, conversions, or acquisitions.

Coming out of COVID, Par’s capital allocation message has been clear: prioritize staying power. More maintenance discipline, more debt reduction, and share repurchases when management thinks the stock is cheap. It’s the posture of a company that learned—twice—what leverage and volatility can do, and that also knows the long-term direction of the industry is uncertain. Free cash flow, not empire-building, is the scoreboard.

And then there’s retail, which looks small next to refining but plays an outsized strategic role. Gas stations and convenience stores capture the markup between wholesale fuel and the price at the pump, with in-store sales adding another layer of margin. Just as importantly, that network is a sensor. It gives Par direct visibility into demand patterns and competitive behavior, and it tightens the feedback loop between what the refinery makes, what the terminals move, and what customers actually buy.

Put it together and the model becomes clearer: Par makes money when it can combine operational execution with geographic advantage—Hawaii’s logistics protection and the Rockies’ advantaged crude—while keeping enough balance sheet flexibility to survive the next inevitable downcycle. The balance sheet today reflects that mindset: more liquidity, more manageable debt, and structures designed to leave room to operate, rather than forcing decisions at the worst possible moment.

XI. Management & Governance: Who's Running the Show?

Par Pacific’s leadership has changed a lot since the company’s earliest days, when the core skill was spotting distressed assets and figuring out how to finance and stabilize them. Over time, that emphasis shifted. As Par became less of a deal story and more of an operator of essential infrastructure, the center of gravity moved toward people who live and breathe day-to-day refining: reliability, turnarounds, safety, and disciplined capital spending.

Even so, the private equity imprint is still part of the company’s DNA. Sponsor-affiliated investors have held meaningful stakes and, through board representation, have continued to influence governance. That can be an advantage in a business like refining, where being decisive matters and where “good enough” strategy isn’t enough—you need speed, clarity, and the willingness to make hard calls. But it also creates a natural tension. Private equity typically optimizes for returns and timelines. Infrastructure businesses often reward patience and multi-decade thinking. Par has had to balance both.

You can see that push and pull in the board’s composition. There are directors with traditional oil and gas operating backgrounds, alongside finance and private equity expertise, and voices attuned to environmental and regulatory realities. In a sector where the rules can shift as fast as the market, that mix can be a real asset. It can also mean competing priorities at the exact moments when the company needs to pick a lane.

Management pay reflects what the business demands. Equity-heavy compensation ties leadership to shareholder outcomes, while performance focus sits where it should for a refiner: utilization, cost control, safety, and the ability to reliably generate free cash flow and earn returns on invested capital. In other words, the incentives are built around the unsexy fundamentals that separate a good refinery from an expensive headache.

And the personnel choices have mattered. The decision to exit Tacoma wasn’t just a portfolio move; it signaled a willingness to admit a mistake and protect the balance sheet. The Billings acquisition showed Par could still act opportunistically—but within a tighter, clearer thesis. Now the next test is different. Renewable fuels and decarbonization initiatives require new skills, new partnerships, and a different talent mix than traditional petroleum refining. Whether Par can recruit and develop that capability will shape what this company becomes.

Finally, it’s worth understanding the ownership dynamics. Concentrated sponsor ownership can enable faster, more unified decision-making than a widely dispersed shareholder base. But it also raises the question every sponsor-influenced company eventually has to answer: when exit goals and long-term company-building diverge, which one wins?

XII. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

If you run Par Pacific through Michael Porter’s Five Forces, you get a picture that’s almost unfair in a few places—and deeply unsettling in one. The company is well protected against competitors. It’s hard to dislodge. But it can’t geography its way out of a world that simply uses less petroleum.

Competitive Rivalry: In Hawaii, Par operates as an effective monopoly after Chevron exited local refining. There isn’t another player with anything close to Par’s combination of refining, terminals, and distribution. On the mainland, it’s a different story. In the Rockies, Par faces real competition from other regional refiners—but its edge isn’t about being the lowest-cost operator on every line item. It’s about crude access and positioning, the kinds of advantages that show up before the barrel even hits the plant.

Threat of New Entrants: In Hawaii, it’s essentially zero. A new refinery would mean billions in capital, years of permitting, and community buy-in—just to enter a market that already has supply and where the incumbent owns the critical infrastructure. And the Jones Act adds another layer of friction that makes “someone else will just ship it in” harder and more expensive than it sounds. In the mid-continent, the story is similar in spirit: the regulatory burden and the economics of building new refining capacity make greenfield projects extremely unlikely.

Supplier Power: Moderate. Crude oil is a global commodity with plenty of potential counterparties, and Par isn’t hostage to a single producer or one specific stream. It can source cargoes from different origins and work with multiple suppliers. On the non-crude side, refining is still a world of specialized parts and services, but there are enough vendors and enough alternatives to keep any one supplier from holding the company hostage.

Buyer Power: This one depends on who the buyer is. At the retail level in Hawaii, consumers don’t have much leverage. If you need gasoline, you’re not negotiating; you’re paying the posted price. Wholesale customers have more power, especially airlines, which can push on contract terms and, at least in theory, can import supply. But “in theory” matters here—Hawaii’s logistics and costs make alternatives real but limited. In the Rockies, buyers generally have more options, and Par’s products compete in more standard regional wholesale markets.

Threat of Substitutes: This is the force that keeps the whole story from feeling like a permanent toll road. EVs substitute for gasoline. Renewable diesel substitutes for petroleum diesel. Sustainable aviation fuel substitutes for jet fuel. None of this flips overnight—fleet turnover takes years, aviation alternatives face real constraints, and demand doesn’t vanish in a straight line. But the direction is clear, and it’s pointing straight at the heart of what Par sells. Over the next ten to twenty years, this becomes the defining strategic uncertainty.

Taken together, the Porter view says Par has done an excellent job building defenses against rivalry and new entrants. But it also highlights the uncomfortable truth: geographic moats protect you from competitors. They don’t protect you from obsolescence.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Hamilton Helmer lays out seven ways a company can earn durable advantage. When you run Par Pacific through that lens, you don’t get a business with strength everywhere. You get a business with a couple of powers that really matter, and a bunch that are either limited or situational.

Scale Economies: Moderate at best. Par’s refineries aren’t the biggest in their regions, and refining doesn’t have the winner-take-all feel of software or platforms. Being larger helps—purchasing, maintenance planning, and operating leverage all improve—but it’s not the kind of scale that permanently changes the rules of the game.

Network Economies: Minimal. This isn’t a network business where each additional participant makes the whole system more valuable. Par has distribution infrastructure, and infrastructure can feel “network-like,” but it doesn’t create true network effects in Helmer’s sense.

Counter-Positioning: Mostly historical. Par’s origin story is textbook counter-positioning: buying assets the majors were dumping and leaning into a business everyone wanted to flee. That move created the company. But today, it’s less of an ongoing advantage and more of the moment that put Par in the right places on the map.

Switching Costs: High in Hawaii, more moderate elsewhere. In Hawaii, many commercial customers are effectively built around Par’s system—relationships, contracts, delivery patterns, terminal access, and the practical reality that the islands run on tightly managed logistics. Importing is possible, but switching isn’t frictionless. It can mean new supply chains, different storage arrangements, and more operational uncertainty. Those frictions create real stickiness even when alternatives exist in theory.

Branding: Moderate in Hawaii through the Aloha Petroleum name, which has local familiarity and trust. On the mainland, it matters far less. In mid-continent wholesale markets, fuel is usually bought on price and availability, not brand loyalty.

Cornered Resource: This is the big one. Kapolei is a cornered resource in the most literal sense: Hawaii has no other refinery, and geographic and regulatory barriers make replacement extremely difficult. Par’s mid-continent refineries have a softer version of this power through advantaged crude access, but nothing as absolute as “we are the only local refiner.”

Process Power: Moderate. Par has built real competence in refinery operations, turnarounds, and integrating distressed assets. That matters because execution is everything in refining. But it’s not a capability only Par possesses—strong operators elsewhere can do similar work.

Put it together and the takeaway is clear: Par’s most durable advantages come from Cornered Resource and Switching Costs—being embedded in Hawaii’s fuel system in a way that’s hard to replicate and inconvenient to unwind. Those powers held up through commodity crashes and even COVID. The looming question is whether they hold up through something slower but potentially more permanent: the energy transition.

XIV. The Bear Case: Why Par Pacific Might Struggle

The bearish view of Par Pacific starts with a blunt premise: the products that built the company are on the wrong side of history. Every electric vehicle that replaces an internal-combustion car in Hawaii is one less long-term gasoline customer. Every push toward sustainable aviation fuel changes what airlines and airports want to buy. The shift may take years, but the arrow points in one direction.

Hawaii makes that risk feel more immediate. The state’s decarbonization goals are among the most aggressive in the U.S., and the political appetite to use mandates and incentives is real. If Hawaii leans harder into EV adoption, requires more renewable blending, or puts a price on carbon, Par’s economics could get squeezed faster than those of a similar refinery on the mainland.

That’s where stranded-asset risk comes in. Par’s refineries are massive, specialized pieces of infrastructure. They’re valuable because they turn petroleum into finished fuels. If the market moves away from those fuels quickly enough, the value of the plants can fall a lot faster than the depreciation schedules suggest. And unlike many businesses, you can’t casually repurpose a refinery into something else without spending a lot of money and taking on a lot of technical risk.

The balance sheet and scale matter here, too. Par can generate meaningful cash flow, but it doesn’t have the same financial firepower as the supermajors. Big oil can spend billions building portfolios of low-carbon options. Par’s investment capacity is far smaller. If the transition demands major, repeated bets—new units, new feedstock systems, new compliance capabilities—Par may not have the margin for error.

Small scale also shows up in technical depth. Renewable fuels, feedstock optimization, and conversion engineering aren’t just capital problems; they’re expertise problems. Larger companies can keep big technical teams in-house. Par is more likely to depend on partners, licensors, and outside specialists, which can mean less control, more dependency, and sometimes slower iteration.

Regulation is another pressure point even before demand falls off. Stricter emissions standards, higher compliance costs, and the possibility of carbon pricing can compress margins in a business where margins are already cyclical. And the trend line, historically, has moved toward tighter rules, not looser ones.

Then there’s concentration risk. Hawaii is Par’s crown jewel, but it’s also a single geography with a single economic engine: tourism. COVID was the reminder of how quickly island demand can crater when visitors stop showing up. Another pandemic, a recession, or a geopolitical shock that hits Pacific travel could once again attack Par right where it matters most.

Finally, there’s execution risk. Recognizing the need to pivot toward renewable fuels is not the same as pulling it off. The transition demands new supply chains, new commercial relationships, and a different operating playbook. In a business where small mistakes can become expensive quickly, there’s no guarantee Par gets the renewable shift right on the first try.

XV. The Bull Case: Why Par Pacific Could Thrive

The bullish view begins with a simple claim: Par’s moat is real, and it has already been stress-tested. Hawaii needed fuel in 2013. It still needed it in 2015 when oil crashed. It needed it in 2020 when tourism vanished. And it’s very likely to need it for a long time yet. Even if new car sales swing hard toward EVs, the cars already on the road don’t evaporate. Fleet turnover is slow, and that buys time.

That timeline is everything. A business staring at a slow, multi-decade decline is a different animal than one facing disruption next quarter. If Par can keep generating strong free cash flow through the next decade, it can deleverage, build a war chest, and move deliberately instead of desperately. In that world, the energy transition becomes a strategic repositioning—not a scramble for survival.

There’s also a more contrarian angle: Hawaii’s renewable fuel shift could end up strengthening Par’s position. The same factors that made petroleum supply defensible—ocean distance, logistics complexity, and regulatory friction—don’t disappear just because the molecule changes. If Par can convert parts of its system to produce renewable diesel or sustainable aviation fuel, the competitive dynamics may look familiar: limited local alternatives, high barriers to entry, and an incumbent that already controls the chokepoints.

And those chokepoints matter. Par’s terminals, distribution relationships, and retail footprint aren’t just assets on a balance sheet—they’re the operating system of Hawaii’s fuel supply. A would-be competitor doesn’t just need product; it needs tanks, docks, trucks, contracts, and trust. Building that from scratch would be slow and expensive. Partnering with Par may be the only practical route.

Free cash flow is the other quiet advantage. Par isn’t forced to fund its future by begging for capital at exactly the wrong point in the cycle. If the core business keeps throwing off cash, management can finance transition projects internally, try approaches that aren’t all-or-nothing, and adjust as policy and economics evolve.

Meanwhile, the Rockies assets give Par a second engine. Montana and Wyoming play a different game than Hawaii, with different crude supply dynamics, different regulations, and different demand patterns. That diversification matters if Hawaii decarbonizes faster than expected—or if another Hawaii-specific shock hits tourism and jet fuel demand.

Even the private equity influence, for all its tradeoffs, can work in shareholders’ favor here. Sponsors tend to push for discipline: don’t chase deals just to get bigger, don’t overleverage, and return cash when reinvestment doesn’t clear the bar. In refining, that restraint can be the difference between compounding and blowing up.

Put it all together and you get the final bullish point: the market may be pricing Par as if obsolescence is imminent. If the transition actually unfolds over fifteen to twenty years—slow enough for Par to harvest cash, reinvest selectively, and evolve—the gap between perception and reality could be where the opportunity lives.

XVI. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

Par Pacific’s story is about refining on the surface. Underneath, it’s a case study in how to buy, build, and survive when you’re playing with essential assets in volatile markets. Here are the lessons that travel well beyond oil.

The distressed asset playbook. Every industry has windows where good assets get thrown into the “too hard” pile—prices collapse, sentiment turns toxic, and incumbents rush for the exits. Par bought Hawaii’s refinery in one of those windows. The takeaway isn’t “distressed equals cheap.” It’s that when everyone agrees something is uninvestable, the few people willing to do real work can sometimes buy long-lived assets for a fraction of what they’d cost to replace.

Geographic moats matter more than scale. Business school loves scale. Par’s edge came from the map. A smaller operator in a protected geography can earn better economics than a larger operator surrounded by pipelines, competitors, and easy alternatives. That idea applies far outside energy: if a location creates structural friction—logistics, regulation, or natural constraints—you can’t value the business like a generic commodity player.

Infrastructure businesses require patient capital. Par’s two brush-with-death moments, in 2015 and 2020, both ended the same way: stakeholders looked past the short-term income statement and focused on the underlying reality that the assets were essential. That kind of patience isn’t available to every company. But when you own critical infrastructure, the question becomes less “is this quarter ugly?” and more “what happens if this system fails?” That changes behavior—especially for lenders.

Know when to cut losses. The Tacoma refinery is the reminder that discipline isn’t just about what you buy. It’s about what you’re willing to sell. Par could have kept pouring money and attention into a turnaround that wasn’t delivering, hoping the cycle would bail them out. Instead, they admitted the thesis wasn’t working and walked away. In cyclical, capital-intensive businesses, that ability to exit is often the difference between a setback and a balance-sheet-ending mistake.

Regulatory moats are double-edged swords. The Jones Act and Hawaii’s isolation helped protect Par’s position for years. But regulation can flip from shield to constraint. If policy pushes faster renewable adoption, the same petroleum system that once looked like an irreplaceable advantage can start to look like a stranded bet. Regulatory protection isn’t “set it and forget it.” It’s something you have to track, anticipate, and adapt around.

Energy transition requires different skills. Running a petroleum refinery rewards execution: reliability, turnarounds, crude optimization, and ruthless maintenance discipline. Renewable fuels are adjacent, but not identical. They bring new feedstocks, new economics, new incentives, and often new partners. Companies that assume the transition is just a bolt-on project tend to learn, the hard way, that it’s also a capability shift.

Capital structure matters. Par’s biggest crises weren’t only operational—they were financial. Leverage that looks reasonable in normal conditions becomes suffocating when demand collapses. The company’s post-COVID push to deleverage wasn’t conservative posturing. It was a recognition that flexibility is a competitive advantage when your industry’s downturns arrive fast and without mercy.

The private equity influence has trade-offs. Sponsor ownership helped create Par and, at key moments, imposed discipline—decisive action, capital focus, and a willingness to make unpopular calls. But sponsor timelines don’t always line up with the slow compounding that infrastructure can reward. That tension—between optimizing for returns on a schedule and building an essential system for the long haul—runs through the entire Par story.

XVII. What to Watch: KPIs & Signposts

If you want to track Par Pacific without getting lost in refinery jargon, there are a handful of signals that tell you, quickly, whether the story is strengthening or starting to fray.

Start with Hawaii jet fuel demand and crack spreads. This is the heartbeat of the whole thesis. Jet fuel ties directly to tourism and flight activity, and it has historically been one of the most attractive parts of the barrel for Par in Hawaii. When jet fuel demand is strong and margins are healthy, Kapolei looks like the fortress it was built to be. When that demand softens, you’re reminded how exposed Hawaii can be to travel cycles and structural shifts in aviation.

Next, watch refinery utilization across all three plants. Refining is unforgiving: when you run well, you generate cash; when you don’t, problems compound fast. Utilization is the cleanest shorthand for operational execution, and it’s tightly linked to turnaround performance. Planned maintenance will always take barrels offline, but the tell is whether turnarounds come in on time and on budget, and whether the plants return to steady, reliable operation afterward.

Then there’s the transition. Renewable fuel project progress is the clearest public window into whether Par is adapting fast enough. Updates on sustainable aviation fuel partnerships, renewable diesel initiatives, and any conversion or co-processing work aren’t just “nice to have” announcements—they reveal where management believes demand, policy, and economics are headed. Just as importantly, the spending tells you what the words don’t: how much capital is going to renewables versus keeping petroleum capacity optimized.

After that, the scoreboard becomes financial resilience. Leverage and free cash flow show whether Par is building flexibility or drifting back toward the balance-sheet risk that nearly sank it before. This is a cyclical business. The companies that survive are the ones that don’t force themselves into bad decisions at the bottom of the cycle.

Also keep an eye on Hawaii’s regulatory posture. Decarbonization mandates, renewable blending requirements, and EV incentives can move from “long-term goals” to near-term economics faster than most investors expect. Policy is one of the few forces that can change demand without waiting for a normal market cycle.

For the Rockies assets, the key external driver is mid-continent crude differentials. Billings and Newcastle are most advantaged when local crude is meaningfully discounted versus coastal benchmarks. When those discounts widen, Par’s input economics improve. When they compress, the edge gets smaller.

Finally, watch competitors—especially around renewable fuels in the Pacific. The big question isn’t whether someone can make a product elsewhere. It’s whether anyone can reliably land it in Hawaii at scale, at attractive economics, and with enough infrastructure behind it to matter. If that starts to change, Par’s moat is still there, but it’s no longer static.

The trick is matching the signal to the time horizon. Utilization and crack spreads tell you what the next quarter or two might look like. Regulatory shifts and renewable project milestones tell you what the next five to fifteen years might look like. Knowing which is which is how you separate noise from a real change in the story.

XVIII. Epilogue: The Next Chapter

As 2025 draws to a close, Par Pacific sits in a strangely powerful spot in the American energy landscape. It’s lived through the events that usually end refiners—commodity crashes, a once-in-a-century demand collapse, and an ill-fated expansion—and it’s still here. Not as a sprawling empire, but as a tighter portfolio of assets that can throw off real cash flow, backed by advantages that come from geography as much as engineering.

The last few quarters have been a reminder of what Par actually is when the world isn’t on fire. The post-COVID refining boom faded, margins cooled back toward normal, and yet the company kept standing. Hawaii’s visitor economy kept healing, pushing jet fuel and gasoline demand closer to where it was before the pandemic. In the Rockies, the thesis has stayed intact: when pipeline and logistics constraints show up, the ability to source advantaged crude still matters.

The backdrop, though, is pulling Par in two directions at once. On one side, energy security has come roaring back as a political priority. With geopolitical tensions and fragile supply chains, domestic refining capacity suddenly looks less like yesterday’s problem and more like today’s insurance policy. On the other side, climate policy keeps tightening. Federal and state frameworks keep nudging markets toward lower-carbon fuels, and Hawaii remains one of the places most willing to move fast. Par’s near-term relevance is being reaffirmed at the same time its long-term role is being questioned.

Meanwhile, the industry around it keeps consolidating. Bigger players keep buying advantaged assets and shedding the rest. That dynamic inevitably puts a spotlight on Par’s crown jewel. Hawaii’s only refinery isn’t just an earnings stream; it’s control of a critical system. The strategic value of that kind of asset can exceed what the quarter-to-quarter numbers would suggest, which means Par will always live on some buyer’s map. Whether it stays independent or ends up inside a larger platform is one of the futures the market has to keep in mind.

And then there are the true wild cards. A step-change in renewable fuel technology could compress the timeline. Policy could swing, making petroleum either harder to sell or, in a security-driven moment, harder to replace. Another geopolitical shock could scramble crude flows, freight markets, or demand patterns. For a company this tied to both regulation and logistics, the range of outcomes is wider than you’d expect for a “mature” industry.

So the core investor question doesn’t really change: is Par a value trap, or a misunderstood transition story?

If it’s a value trap, the transition speeds up faster than real-world fleet turnover, Hawaii’s policies land in a way that directly erodes petroleum economics, and renewable fuels become something Par can’t compete in—either because the technology moves elsewhere or because the import economics overwhelm the moat.

If it’s the opportunity, the transition plays out at infrastructure pace, not headline pace. Par uses its existing assets and chokepoints to stay essential—first for petroleum, then increasingly for lower-carbon molecules. And eventually, the market stops valuing the company like a stranded relic and starts valuing it like what it has often behaved like in practice: critical infrastructure with a long runway and real options.

Neither ending is locked in. Par’s next chapter will be decided the same way the last one was: by management choices, regulatory realities, technology that either arrives on schedule or doesn’t, and the energy market’s constant ability to surprise. The company that once turned a discarded refinery into Hawaii’s energy lifeline now faces its next reinvention—and it may be the most consequential one yet.

XIX. Further Learning & Resources

If you want to go deeper on Par Pacific, the best sources fall into a few buckets: what the company says about itself, what the industry says about refining, and what Hawaii’s policy environment says about the future.

Start with Par Pacific’s own materials. Investor presentations and SEC filings are where you’ll see the strategy in the company’s own words, plus the hard details behind it. The annual 10-Ks are especially useful: they lay out operations, risk factors, and the “what keeps management up at night” context that quarterly updates often gloss over. Earnings calls tell you what happened. The 10-K tells you what has to go right.

For broader oil-and-refining context, Daniel Yergin’s The Prize is still the classic. It’s not a Par book, but it gives you the historical muscle memory for why refining behaves the way it does—cyclical, political, essential, and constantly underestimated. Pair that with more modern writing on the energy transition to understand how petroleum demand may evolve, and which parts of the barrel are most exposed versus most resilient.

To understand why Par’s Hawaii position is so unusual, go straight to Hawaii-specific sources. State energy policy documents and the clean energy roadmap will show you the direction of travel on decarbonization, and the likely tools policymakers will use to get there. Academic work on island energy systems is also worth your time, because islands don’t get to pretend logistics are a rounding error. Isolation shapes everything: costs, reliability, storage, redundancy, and what happens when supply chains break.

Then there’s the Jones Act. If you want to understand the moat around Hawaii fuel supply—and the political risk around that moat—read analysis from maritime policy institutes. The law is a century old, but the debate around it is alive, and it matters for how expensive it is to move fuel between U.S. ports.

For current, operational reality, industry publications help. Oil & Gas Journal is a staple for technical refining developments. Trade association reports and renewable fuel coverage are useful for tracking renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel momentum. And EIA refining industry reports provide the neutral baseline: capacity, utilization, and regional dynamics that let you separate a company-specific story from an industry-wide cycle.

If you like strategy frameworks, Michael Porter’s Competitive Strategy and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers are the right tools for this kind of business. They’re not written for refiners, but Par is exactly the sort of company where clear thinking about advantage—geography, switching costs, barriers to entry—matters more than elegant narratives.

Finally, Par is also a private equity and distressed-asset story. Case studies on refinery turnarounds and acquisition histories—especially involving companies like Tesoro and HollyFrontier, which have bought and sold similar assets—are useful for pattern recognition. They help you see what tends to work in refining M&A, and what tends to turn into an expensive lesson.

And if you’re trying to gauge Par’s next decade, keep a close eye on sustainable aviation fuel and renewable diesel. Reports from groups like IATA on aviation’s fuel transition and the IEA on renewable fuel economics are good places to track the moving target: timelines, incentives, supply constraints, and competitive dynamics.

The story doesn’t really end here. Par Pacific is a case study in how geography can turn a brutal commodity business into something closer to infrastructure—and how even the best moat has to evolve when the underlying world changes. Whether you’re an investor, competitor, or just a student of strategy, the company’s first decade offers a lot of lessons that will still matter as the next chapter gets written.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music