Oxford Industries: The Story of America's Apparel Architect

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

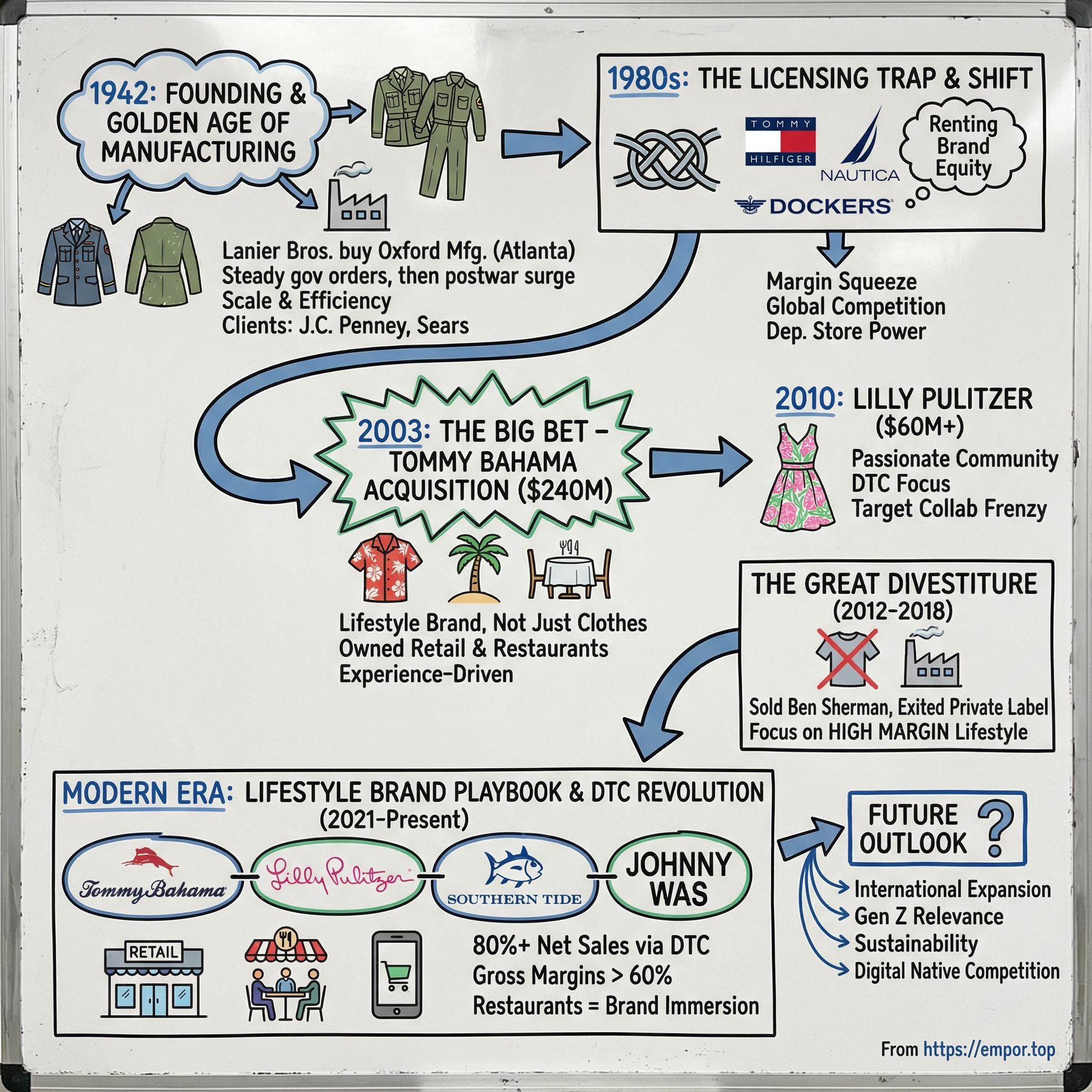

Picture this: it’s 2003, and you’re in a boardroom in Atlanta. Around the table are executives who’ve spent their entire careers mastering a very specific craft: cutting fabric and sewing shirts—millions of them—on behalf of brands they don’t own, for customers they’ll never meet.

For six decades, that model built Oxford Industries. But now it’s starting to suffocate. Globalization is pushing manufacturing overseas. Department stores are consolidating and squeezing suppliers. The dependable middle of the apparel industry—the place Oxford has lived for generations—is disappearing.

And then the CEO puts a proposal on the table that sounds, to some people in that room, like a controlled burn: spend $240 million—nearly half the company’s market value—to buy an island-themed lifestyle brand known for Hawaiian shirts… and restaurants.

The skeptics aren’t being dramatic. Oxford is, at its core, a manufacturer. Even when it expanded into licensing, it still played the behind-the-scenes role: make the product, ship it out, let someone else own the customer. Marketing? Direct retail? Hospitality? That’s not in the company’s muscle memory. And Tommy Bahama, while beloved, is small and strange by Oxford’s standards—more mood than machine.

But that moment—the willingness to bet big on something Oxford wasn’t yet—kicks off one of the more instructive transformations in modern American retail. Over the years that followed, Oxford would evolve from an anonymous supplier into the owner-operator of a portfolio of premium lifestyle brands: Tommy Bahama, Lilly Pulitzer, and Southern Tide.

By 2024, Oxford generated $1.52 billion in revenue. That’s a long way from its roots as a contract manufacturer. But the headline isn’t the size. It’s the reinvention: a company that moved from making clothes for other people’s brands to building, owning, and selling its own—with a playbook built around acquisitions, direct-to-consumer retail, and an unusually experiential approach to what “apparel” can be.

In this episode, we’re going to trace that arc. We’ll start with how a family of brothers from Nashville bought a small military uniform operation during World War II—and turned it into a public company. We’ll dig into the licensing era that powered Oxford for decades, and why it eventually became a trap. Then we’ll go deep on the pivotal leap: the Tommy Bahama acquisition in 2003, the move into owned retail, and the restaurant strategy that looks weird on paper but turns out to be central to the brand.

Along the way, we’ll pull out the frameworks that explain what Oxford did right, where its advantages actually come from, and what could still go wrong. If you’re an investor trying to understand apparel, a founder thinking about reinvention, or just someone who loves a great American business pivot, this story has a lot to teach.

So let’s start where a lot of great American business stories start: three brothers, a world war, and a bet on the future.

II. Founding & The Golden Age of Apparel Manufacturing (1942–1980s)

In 1942, as the U.S. ramped up for a two-front war, three brothers from Nashville—Sartain, Hicks, and Thomas Lanier—saw opportunity in the scramble. They bought Oxford Manufacturing Company, a military-uniform maker based in Atlanta. The business was already doing roughly $1 million a year in sales, which mattered: this wasn’t a napkin-sketch startup. It was a working factory with real demand behind it.

And that demand was about as dependable as it gets. War meant uniforms. Uniforms meant government orders. For a manufacturer, it was steady volume, low guesswork, and the kind of production discipline that becomes habit.

The Laniers weren’t chasing fashion. They were chasing a durable industrial footing, and the American South offered it: cotton, a growing manufacturing base, and lower labor costs than the North. Oxford fit neatly into that picture.

When the war ended, they faced the classic post-boom question: do you go back to what you were doing before, or do you commit to what’s working now? Before apparel, the brothers had sold dictaphones and business forms. But postwar America was gearing up for a consumer surge—returning soldiers, new households, office jobs, and a country that suddenly wanted to buy again. The U.S. didn’t just need clothing. It needed lots of it, fast.

Oxford moved quickly. In 1943, the company acquired its first manufacturing facility, Champion Garment Company, in Rome, Georgia. Wartime scarcity, oddly, helped too. With retailers short on merchandise and materials tightly controlled, being able to secure fabric—even a little more than your allotment—could make your year. Sartain Lanier later summed up the era with a kind of blunt clarity: there was such a shortage that if the pants had two legs and the button fly worked, you could sell them.

Expansion followed demand. As the war years gave way to the late 1940s, Oxford added plants in Vidalia and Monroe, Georgia, and Tupelo, Mississippi. The Vidalia facility had originally been a bowling alley; for a time, the lanes doubled as cutting tables. By 1944, the brothers bought out their original partners. What started as a wartime purchase was now the family business.

Through the 1950s, Oxford’s core competency became scale manufacturing for big retailers. But even in those early decades, you can see the company learning to adapt. When the slack-suit set that fueled early growth started to fade in popularity, Oxford pushed into outerwear, denim, and women’s shirts. In 1956, it began producing slacks for J.C. Penney—an important win that soon became a defining relationship. By 1959, sales had reached $29 million. Nearly half of that came from pants, and J.C. Penney alone represented 44 percent of Oxford’s business.

That kind of concentration is a double-edged sword. It can fill factories and smooth planning. It can also put a supplier in a chokehold—one customer’s decisions becoming your destiny. Oxford would run into that dynamic more than once.

Still, in mid-century America, this was the way the apparel system worked. The big department stores and national retailers controlled the customer. Oxford controlled the execution. Over time, it became a major private-label manufacturer for household names like J.C. Penney, Sears Roebuck, and Montgomery Ward—quietly building a business that most consumers never knew existed.

By the 1960s, Oxford was big enough to look like an institution. The company listed on the New York Stock Exchange in 1964. In 1965, it moved its headquarters into a new 70,000-square-foot site in Atlanta. At that point, Oxford employed more than 7,000 people and generated $81.7 million in annual sales.

The 1970s brought both growth and early warning signs. U.S. labor costs rose, the economy lurched through the recession that followed the OPEC oil embargo, and American life changed in ways that reshaped wardrobes. As more women entered the workforce, demand surged for affordable, office-friendly sportswear. Meanwhile, the growth of white-collar jobs continued to support the shirt business. Oxford took a hit during the 1974–1975 downturn, but demand recovered quickly. By 1976, apparel sales had climbed to more than $230 million.

Leadership stayed in the family. Sartain Lanier served as chairman and CEO until retiring in 1981, when his son, J. Hicks Lanier, became chairman and CEO. The handoff was smooth—continuity was a feature of Oxford, not a bug. But the industry around them was shifting in ways that would eventually make continuity dangerous.

At its peak, Oxford owned and operated a sprawling manufacturing footprint: dozens of domestic factories and additional offshore operations. For decades, that footprint was the advantage. It meant capacity, control, and speed. But it also locked the company into a cost structure that would become harder to defend as globalization accelerated.

This was the contract-manufacturing bargain in its purest form. Retailers specified what they wanted. Oxford made it. The company didn’t need to persuade anyone with ads or dream up a lifestyle. Its job was operational excellence: cut, sew, ship—on time, at scale, at the right cost.

The problem was that this is a business where the product becomes a commodity. You’re rarely paid for creativity; you’re paid for efficiency. And as Asian manufacturing grew into a global force, “efficiency” increasingly meant labor arbitrage—something American factories were structurally ill-suited to win.

In the 1970s, most investors would’ve seen Oxford as a strong, steady Southern manufacturer with reliable customers and growing sales. The seeds of the next chapter—reinvention out of necessity—were already in the ground. They just hadn’t sprouted yet.

III. The Licensing Era: Building a House of Brands (1980s–Early 2000s)

By the mid-1980s, the economics of American apparel manufacturing had flipped. Offshore production—first nearby in the Caribbean under the 807 tariff provisions, and then increasingly in Asia—made it harder and harder for U.S. factories to compete. Oxford’s leadership could read the trend line. Private-label work, which had been about 80% of sales in the late 1970s, was shrinking. By the mid-1980s, Oxford had pushed that reliance down to around 60%.

So Oxford adapted the way a great operator adapts: it didn’t abandon what it was good at—designing, making, and moving product at scale—but it changed what it was making and for whom. The company pivoted toward branded apparel. Not brands it owned. Brands it licensed.

Oxford went out and won exclusive licenses to produce and sell specific categories under names that already meant something to consumers: Tommy Hilfiger, Nautica, Dockers, Geoffrey Beene, Slates, and Oscar de la Renta. Tommy Hilfiger, for instance, was licensed to Oxford for men’s and women’s golf apparel and men’s dress shirts. In 1997, Oxford added licenses for Nautica and the more moderately priced Geoffrey Beene.

This was a meaningful evolution. Oxford wasn’t just sewing anonymous private-label garments anymore. It was building product lines under designer labels, then distributing them through the retail channels that mattered—especially department stores. The appeal was obvious: Oxford could tap into established brand equity without spending years (and huge budgets) creating consumer demand from scratch. Meanwhile, the brand owners could expand into new categories without building manufacturing and sourcing capabilities in-house. Everyone looked like they was winning.

But the trap was embedded in the model. If you’re a licensee, you’re renting someone else’s relationship with the customer. You can execute flawlessly and still wake up one day to find the contract gone—and with it, the reason the product sells. Oxford felt that risk firsthand when the Polo for Boys license wasn’t renewed after it expired in fiscal 1999.

Around the same time, another shift hit even closer to the core. Oxford’s large wholesale customers weren’t just buying product anymore; many were building their own product development and sourcing capabilities. And the mega-brands—Tommy Hilfiger, Liz Claiborne, Polo, Nautica—were becoming the industry’s gravitational centers. These were companies that, in many cases, had never needed to manufacture. They needed brand builders, marketers, and distributors. They didn’t particularly need a legacy cut-and-sew specialist in Atlanta.

This was the existential moment: Oxford was playing in other people’s games, on other people’s terms. The company didn’t control its own destiny. And the conclusion, once you see it, is hard to unsee: if the real advantage in apparel is brand, then renting brand equity is not a long-term strategy. Oxford needed to own, not rent.

That realization hardened into action. In 1999, Oxford developed a plan and spent the next two years searching for brands to acquire. But the market didn’t offer many easy fits. Much of what was available were “retreads”—distressed names that would require turnaround expertise. And Oxford, at that point, was still largely a manufacturing-and-sourcing machine, not a brand-revival shop.

Meanwhile, the old Oxford was disappearing. By this time, about 85% of its clothing was being made outside the United States. The domestic manufacturing base that had built the company was largely gone. Oxford also started pruning away lower-return businesses, closing underperforming divisions like the Cos Cob sportswear and JBJ womenswear lines in 1991, and taking roughly $25 million in related costs as it tried to exit segments that weren’t worth the effort.

In hindsight, this era did something invaluable for Oxford: it taught the company what actually matters in consumer businesses. Manufacturing can be outsourced. Distribution can be replicated. But brand equity—the durable, emotional connection with a customer—is the one asset you can’t easily copy.

And once Oxford truly absorbed that lesson, the next step wasn’t incremental. It was transformational.

IV. The Inflection Point: Acquiring Tommy Bahama (2003)

By 2003, Oxford wasn’t just looking for “another license.” It was looking for an escape hatch.

Inside the Atlanta headquarters, strategic planning had turned into a search mission: a long list of potential targets—roughly 50 names—filtered through a new set of rules. Oxford wanted a brand with real loyalty, clear positioning, and, most importantly, retail operations already in motion. Not a turnaround. A working engine.

They found it in Viewpoint International, the company behind Tommy Bahama.

On June 13, 2003, Oxford acquired all of Viewpoint’s outstanding stock and its subsidiaries, which it ran as the Tommy Bahama Group. The deal totaled $240 million in cash, $10 million in Oxford common stock, and up to $75 million more in contingent payments tied to performance.

Tommy Bahama wasn’t an obvious fit on paper. It had been founded just a decade earlier, in 1993, in Seattle—far from Oxford’s Southern manufacturing roots—by three apparel veterans: Tony Margolis, Bob Emfield, and Lucio Dalla Gasperina. And instead of building around a designer or a founder’s name, they built around a fictional character: Tommy Bahama, the guy who lived “island life” wherever he happened to be.

That distinction mattered. The brand wasn’t really about Hawaiian shirts. It was about permission. A fantasy of relaxation and ease—an attitude that landed especially well with affluent baby boomers.

The founders treated the character like a real decision-maker. In meetings, they’d literally set out an extra chair for Tommy. Then they’d ask the question that became their strategy filter: “What would Tommy do?” Would Tommy golf? Of course. Would Tommy drink piña coladas? Absolutely. And if that was true… why not build places for him to do it?

That’s how restaurants entered the picture—almost by accident. After Tommy Bahama took off in wholesale, the team decided to open a store in 1995. They found a spot in Naples, Florida. The only catch: the landlord offered 10,000 square feet, and the brand only needed about 2,000. So they improvised. With no restaurant background, they used the extra space for a bar and restaurant, reasoning it would be exactly where Tommy would want to hang out.

Customers agreed. In the first year, the neighboring store sold more than $2 million of merchandise—enough to make the risky build-out look, in retrospect, like destiny.

For Oxford, this was the missing piece. Tommy Bahama had about 30 retail stores, some with attached restaurants, and it was expanding quickly. It was also something Oxford had never had before: a well-known designer label it actually owned, not rented.

J. Hicks Lanier, Oxford’s CEO at the time, put the internal dilemma in blunt terms: “the only thing scarier than doing it was not doing it.” The deal was nearly half of Oxford’s market capitalization. If it went wrong, it wouldn’t be embarrassing—it could be fatal. But Lanier also understood the bigger risk. As he said, “we knew that our historical business model just was not going to be very successful going forward.”

You can see why the urgency was real. In fiscal 2003, Oxford generated $764 million in sales, ran at a 20.7 percent gross margin companywide, and earned $1.34 per share. It was a business, as Lanier described it, “fighting for nickels and dimes.”

Tommy Bahama offered a different game entirely—one where value didn’t come from squeezing cost out of a shirt, but from building a consumer relationship strong enough that people wanted to step into the world of the brand.

The original founders stayed on until their retirements, which helped preserve the tone, the instincts, and the “Tommy” filter through the integration. And Oxford understood what it had really bought: not just a clothing line, but a new operating system—own the customer, build the experience, and stop competing on price alone.

Everything Oxford did next would trace back to that shift.

V. Doubling Down: The Lilly Pulitzer Acquisition (2010)

Seven years after Tommy Bahama, Oxford’s leadership had a new conviction: the real value in apparel wasn’t the shirt. It was the tribe. If you could find a lifestyle brand with a genuine community behind it—and you could own the customer relationship—you could build something far more durable than any manufacturing advantage.

The question was whether Tommy Bahama was a one-time miracle… or the start of a repeatable strategy.

In December 2010, Oxford acquired Sugartown Worldwide, the parent company of Lilly Pulitzer, for $60 million in cash, plus potential adjustments. With earn-outs tied to performance, the total price could reach as high as $80 million.

Lilly Pulitzer came with one of the great origin stories in American fashion. The brand began 52 years earlier with Lilly Pulitzer Rousseau, a Palm Beach socialite who opened a juice stand to sell oranges from her husband’s grove. The juice stained her clothes, so she asked her dressmaker for a shift dress in a loud, colorful print that could hide the mess. Customers didn’t just notice—they wanted one. Before long, the dresses were outselling the juice, and Lilly Pulitzer was born.

Those pink-and-green prints became a kind of coded language: unmistakable, instantly recognizable, and closely tied to a very specific world of prep, resort, and Palm Beach polish.

Like Tommy Bahama, Lilly had something Oxford couldn’t manufacture: loyalty that looked almost irrational from the outside. The brand had drawn interest from would-be buyers before, but it hadn’t found a partner that felt right. Oxford’s CEO J. Hicks Lanier said they were looking for a “cultural fit,” with “shared values, approach to business and vision of how to build lifestyle brands.” Lilly fit—distinct from Tommy Bahama, but complementary in its sunny, escapist DNA.

That devotion became impossible to miss in April 2015, when Target launched a 250-piece collaboration with Lilly Pulitzer. The collection went live at 3 a.m., and the demand was so intense it overwhelmed Target’s website and apps, knocking them offline not long after launch. Shoppers reported racks being cleared out within minutes—sold out within ten minutes of opening in many stores.

The frenzy sparked criticism that Target should have made more inventory. But for Oxford, the takeaway was crystal clear: this wasn’t just a clothing label. It was a community that showed up, hunted product, and treated the brand like an event. The 2015 Target moment didn’t create the Lilly thesis—it proved it.

At the time Oxford bought it, Lilly Pulitzer was contributing over $75 million in annual sales. Importantly, it already had a meaningful direct-to-consumer engine: 16 company-owned stores plus an e-commerce site, together accounting for about 45% of total annual net sales. Oxford’s plan was straightforward: open four to seven new stores a year in carefully chosen locations and lean harder into e-commerce, which it saw as “the biggest opportunity.”

By fiscal 2023, Lilly Pulitzer had grown to $299 million in sales. In Q1 2025, it delivered low double-digit sales growth, helping offset declines elsewhere in the portfolio. That’s exactly what Oxford wanted from a multi-brand strategy: different brands, different customer moods, and less reliance on any single engine.

Lilly’s core customer is typically 35 to 60, with a sweet spot in the 40s and 50s. And the women’s side of the business was the growth story—expanding faster than men’s. Over the last five years, women’s grew 53 percent as a percentage of sales, compared with 22 percent for men’s.

Seasonality also rhymed with Tommy Bahama. Lilly is a resort-first brand, with spring and summer as the most important seasons, representing about 60% of sales and a substantial majority of operating profit. The calendar concentration created synergy with Tommy Bahama’s resort orientation, while still serving a distinct, complementary customer base.

Most importantly, Lilly Pulitzer showed that Oxford’s Tommy Bahama win wasn’t a fluke. Oxford was starting to look less like a former manufacturer that happened to buy a great brand—and more like a company developing a real playbook for acquiring and scaling lifestyle brands with passionate communities.

VI. The Great Divestiture: Exiting Licensing (2012–2018)

As Oxford built its new lifestyle portfolio, it made an equally important move in the opposite direction: it began cutting away the businesses that tied it to the old world. This wasn’t housekeeping. It was identity work—walking away from the very lines that had once made Oxford “Oxford.”

If you want the clearest example of how the company learned, experimented, and then got ruthlessly disciplined, look at Ben Sherman.

In 2004, a year after buying Tommy Bahama, Oxford acquired Britain’s Ben Sherman, Ltd. from the European venture capital firms 3i and Enterprise Equity. The price was about $146 million—a big swing for what was positioned as an iconic British label aimed at hip, urban youth.

For a moment, it looked like the swing connected. Management later admitted, “The first year was a home run.” But then reality set in. “The next three years were difficult.” The brand never found consistent momentum inside Oxford, and the fit just wasn’t the same as Tommy Bahama. Even with U.S. distribution that rhymed with the Tommy playbook—men’s specialty stores and Nordstrom—the execution never quite clicked.

By 2010, Ben Sherman sales had fallen 15 percent to $86.9 million. Losses improved, but the bigger point was hard to ignore: Oxford was spending time and capital on a business that didn’t strengthen the core strategy it was building around Tommy Bahama and Lilly Pulitzer.

So Oxford did the unglamorous thing that separates a portfolio builder from a collector: it sold.

In 2015, Oxford sold 100% of Ben Sherman for £40.8 million, or $63.7 million, to Marquee Brands. It expected net cash proceeds of about $58 million. Against that original $146 million purchase price, it was a painful outcome—but Oxford was clear-eyed about why it was doing it. As management put it at the time, with the strength of Tommy Bahama and Lilly Pulitzer, “Oxford is well-positioned to continue to generate long-term value for our shareholders.” The subtext was even clearer: we’re doubling down on what works, and we’re done subsidizing what doesn’t.

Ben Sherman wasn’t an isolated move. It fit into a broader unwind of Oxford’s legacy operations.

In 2006, Oxford sold its Womenswear Group to Li & Fung for $37 million. That business was large—about $300 million in sales—but it carried the same DNA as Oxford’s older model. As management put it, it had “all the same characteristics as its legacy men’s manufacturing business,” and “that was concerning to us.”

Oxford also sold the bulk of its Oxford Apparel business—private label shirts—to Li & Fung for $122 million. To make that transition real, Oxford closed all but one of its manufacturing facilities.

And then came the final, symbolic break: the exit from the Lanier Apparel tailored clothing manufacturing division. CEO Tom Chubb captured what made this period so consequential: “A lot of companies have a hard time moving past their history. But we didn’t get so mired in our heritage that we couldn’t move forward.”

The market didn’t immediately love this strategy. Wall Street tends to flinch when revenue shrinks, and Oxford was deliberately making itself smaller on the top line. But what the company was really doing was upgrading the quality of its earnings—trading volume businesses where price was everything for brand businesses where the customer relationship actually mattered.

You could see that upgrade in the gross margin profile. Before the transformation, when Oxford was still largely a contract manufacturer, companywide gross margins were around 20.7 percent. After the shift to owned lifestyle brands, gross margins expanded to above 60 percent.

Oxford’s philosophy during the divestiture era was simple, and it became the operating principle for everything that followed: “We are working to control our own destiny and be in businesses where price is not the primary ingredient.”

That’s what this chapter really was. Not a cleanup. A controlled demolition—so Oxford could rebuild around brands it owned, customers it knew, and experiences it could charge for.

VII. The DTC Revolution & Restaurant Strategy (2010s–2020)

Oxford’s transformation from manufacturer to brand owner was only half the escape. The other half was more radical: stop living and dying by wholesale partners, and build a business where Oxford owned the customer relationship.

That realization crystallized during the 2008 financial crisis. Department stores and other wholesale accounts pulled back hard, and Tommy Bahama felt it immediately. But in the middle of that contraction, something else showed up in the numbers: e-commerce was rising. People still wanted the Tommy Bahama feeling. They just weren’t reliably finding it on a department store rack.

So management leaned into what it could control. “We made a hard pivot to shift our resources to our own stores. We took control of the brand and the messaging.” Over time, the mix flipped—away from a business dominated by wholesale and toward one dominated by owned retail.

And once you start thinking like that, the restaurants stop looking like a quirky side quest and start looking like strategy.

Today, Tommy Bahama’s 22 Restaurants and Marlin Bars generate over $100 million in sales. CEO Doug Wood put it in perspective: “How many restaurants can say they are still growing after 28 years?” But the point isn’t just that the restaurants make money. They do three jobs at once: they produce profit, they send traffic into nearby stores, and they turn the brand from something you buy into somewhere you go.

Most locations are next to, or connected to, a retail store. The company says having a restaurant can lift adjacent retail productivity dramatically—up to roughly double the sales per square foot. And the logic is simple: time equals attachment. As Wood explained, “When we look at our opportunity to show people what our brand is about, we have eight minutes online, 15 minutes at a store, and anywhere from an hour or two in a restaurant.” An hour with the brand, in a booth with a cocktail and live music, is a very different relationship than a quick browse on a website.

The Marlin Bar concept was the next evolution—built for places where a full restaurant wouldn’t fit. Oxford asked Robert Goldberg, EVP of Restaurants, to design something smaller that kept the same food and aesthetic in a fraction of the space. It’s “[a] bar first,” Wood said—more casual, easier to drop into, and more scalable.

Even internally, expectations started conservative. “At first, we thought even if we break even on food and beverage and increase our retail sales by as much as 30%, it is a win.” What followed surprised them. At Coconut Point in Estero, Florida, the Marlin Bar’s sales were expanding at a 300% clip. The ninth Marlin Bar opened in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, and the company planned to open four to five a year.

The broader trend was clear: experiential retail wasn’t dying—it was being redesigned. In fiscal 2021, restaurant sales rose 15 percent to $96 million compared with fiscal 2019, and the momentum carried forward with sales up 23 percent in subsequent quarters. Wood captured the changing consumer mood: “People are looking for something quicker—they don't want to always give us an hour to two hours. They can shop from their couches now. And I do love our business on the website, but the human interaction is important. This gives them a reason to come have a drink, hear live music, and shop.”

Then Tommy Bahama pushed the idea to its logical extreme: if a restaurant gives you one or two hours, what do you get from a resort? In November, the company opened the Tommy Bahama Miramonte Resort & Spa outside Palm Springs, California. “To be a true lifestyle brand, you have to have products and experiences that allow guests to immerse themselves in your brand. The resort is simply an extension of that.” The ambition was to let customers live the brand for three, five, or seven nights—not just minutes on a sales floor.

All of this fed the same outcome: Oxford’s economics changed because its relationship with the customer changed. By fiscal 2023, direct-to-consumer channels—retail stores, e-commerce, and outlets—accounted for about 80% of net sales. Owning the point of sale meant more full-price selling, more control over merchandising, and far less dependence on wholesale partners who could squeeze margins or cut orders overnight.

The financial story follows the strategy. Oxford’s gross margin expanded from roughly 20% in the manufacturing era to above 60% in the DTC era. That margin expansion, more than any single acquisition, explains how Oxford could move from a “nickels and dimes” supplier into something closer to a modern brand platform—one built not just to sell clothes, but to sell a lifestyle directly to the people who want it.

VIII. COVID Crisis & The Acceleration (2020–2021)

In March 2020, Oxford Industries ran straight into what looked like an existential threat. Overnight, the very things that made its brands special—stores you could wander through, restaurants where you could linger, that whole “island life” escape—became liabilities. Every Tommy Bahama restaurant went dark. Retail stores closed. Discretionary spending froze.

Oxford’s first move was simple and human: it temporarily shut all owned retail stores and restaurants in North America, effective March 17 through March 30, 2020, and continued paying its retail and restaurant associates during that time. Meanwhile, the digital storefronts stayed open. Tommy Bahama, Lilly Pulitzer, and Southern Tide could still sell online, even if the physical experience had vanished.

Then something surprising happened: customers showed up anyway—just through a screen.

With people stuck at home, e-commerce surged. And Tommy Bahama, of all things, found itself with a very specific product-market fit for the moment. Comfortable, polished shirts that looked great on camera became the unofficial uniform of the new world of video calls. The brand’s relaxed fit and easy confidence turned into a pandemic staple—the “Zoom shirt” effect.

Oxford also got an unexpected assist from its own map. Before COVID, a heavy footprint in Florida and resort markets could look like concentration risk. During COVID, it became an edge. As remote work spread and travel patterns shifted, affluent customers weren’t just visiting coastal towns—they were spending more time there, and in many cases relocating. Tommy Bahama’s core fantasy started looking less like escapism and more like a lifestyle people could actually live.

By the time the dust settled, Oxford hadn’t just survived. It had learned. The company came out of the crisis with permanent cost reductions, sharper digital capabilities, and a leaner operating structure. Trends that were already underway—online buying and work-from-anywhere living—suddenly compressed from “slow shift” into “new default,” and Oxford was forced to get good at meeting the customer where they were.

By fiscal 2021, the rebound showed up clearly. Restaurant sales rose 15 percent to $96 million versus fiscal 2019. Oxford’s stock, after plunging during the initial lockdowns, recovered and went on to exceed pre-pandemic highs as investors recalibrated: this wasn’t a fragile mall-and-department-store story. This was a controlled-distribution, direct-to-consumer portfolio with real pricing power and real flexibility.

In a strange way, COVID ended up validating the entire Oxford thesis. Brands built on wholesale racks and department store traffic got squeezed as those channels weakened further. Oxford, with owned stores, owned digital channels, and experiences that could flex from physical to online, proved it could adapt—fast—without handing the steering wheel to anyone else.

IX. Modern Era: The Lifestyle Brand Playbook (2021–Present)

Today, Oxford Industries runs a portfolio of lifestyle brands that together generate about $1.5 billion in annual revenue. The company owns and markets Tommy Bahama, Lilly Pulitzer, Johnny Was, Southern Tide, The Beaufort Bonnet Company, Duck Head, and Jack Rogers. This is not the contract manufacturer Oxford was in 2003. It’s a brand-led, experience-driven consumer business.

That portfolio didn’t get built by accident. Oxford kept expanding, but it did it the same way it reinvented itself in the first place: disciplined acquisitions of brands with real followings.

In April 2016, Oxford acquired Southern Tide for $85 million. The headline wasn’t just “another brand.” It was the fit. Southern Tide already had a well-defined point of view—classic Southern style, high-quality construction, and a growing multi-channel footprint—and Oxford didn’t have to guess whether the brand was real. It had been watching it up close since 2009, when Oxford began providing sourcing and production services. By the time Oxford bought the company, it wasn’t stepping into the unknown; it was formalizing a relationship and backing a brand it had already seen resonate with customers.

Southern Tide was founded by 23-year-old Allen Stephenson, who saw a gap in the market for premium apparel with a traditional Southern sensibility. It remained primarily a men’s brand, anchored in sport shirts, swimwear, shorts, and accessories—especially strong in specialty and department stores across the South. It also built a collegiate line for nearly 50 colleges and universities, extending the brand into a ready-made community.

Then, in September 2022, Oxford made its next major move: acquiring Johnny Was for $270 million. Johnny Was is a California-based “affordable luxury” lifestyle brand, built around a free-spirited, signature aesthetic and a distinct take on the California lifestyle. The pitch from Oxford was straightforward: beautifully crafted clothing and accessories that aren’t chasing micro-trends—they’re expressing an identity.

Oxford told investors Johnny Was checked every box on its acquisition list: premium pricing, well-defined positioning that drives loyalty, a profitable model, a capable leadership team, and a growth trajectory that could be sustained. Just as importantly, it complemented the existing portfolio instead of cannibalizing it.

By this point, you can see the Oxford playbook in full focus. Find lifestyle brands with passionate customer communities. Make sure the brand identity is unmistakable. Look for proven economics and leaders who can keep running the brand. Then plug the business into Oxford’s infrastructure—sourcing, e-commerce, real estate, and capital—without sanding off what made the brand special in the first place.

Operationally, during fiscal 2023 the company ran through four groups: Tommy Bahama, Lilly Pulitzer, Johnny Was, and Emerging Brands. Those groups accounted for 57%, 22%, 13%, and 8% of consolidated net sales, respectively.

A key part of making a portfolio like this work is governance. Oxford uses a brand president model: each brand keeps its own CEO and leadership team, preserving distinct positioning and culture, while benefiting from shared capabilities—Oxford’s scale in sourcing, e-commerce infrastructure, real estate relationships, and capital allocation.

But even a great playbook gets tested. In fiscal 2024, Oxford reported consolidated net sales of $1.52 billion, down 3% from $1.57 billion in fiscal 2023, driven primarily by softer demand across both wholesale and direct-to-consumer channels. Adjusted earnings per share fell to $6.68 from $10.15 the year before.

Rather than retreat, Oxford continued investing in the parts of the machine it believes compound over time—especially direct-to-consumer. The company committed to significant capital expenditures, including a multi-year project to enhance its Southeastern United States fulfillment center, aimed at strengthening its DTC capabilities.

X. Leadership & Culture: The Hicks Family Legacy

Oxford’s transformation is inseparable from the way it’s been led. In an industry famous for turnover and trend-chasing, this has been a continuity story—eight decades of leadership shaped by the Lanier family and the successors they chose.

It starts in 1942, when Sartain, Hicks, and Thomas Lanier bought Oxford Manufacturing Company in Atlanta. As the business grew into a public company—joining the New York Stock Exchange in the 1960s—Sartain Lanier remained at the helm, serving as chairman and CEO until he retired in 1981. Then came the handoff that defined the next era: his son, J. Hicks Lanier, stepped in as chairman and CEO.

J. Hicks Lanier led Oxford through the licensing years and, more importantly, through the moment the licensing model stopped being “strategy” and started being a slow squeeze. The Tommy Bahama deal in 2003 was the proof point. He didn’t just approve an acquisition—he endorsed a new identity for the company, choosing reinvention over extracting a few more years from a business model that was clearly getting worse.

That same long-view mindset carried into the next generation of leadership. Oxford is led by Thomas C. Chubb III, who has served as Chairman, Chief Executive Officer, and President since January 2013. Chubb’s story is Oxford in miniature: he joined as a summer intern in 1988 and stayed, taking on a series of executive roles over more than three decades, including President beginning in 2009 and Executive Vice President before that.

Chubb’s rise also says something important about Oxford’s culture: this isn’t a company that tries to solve every problem by importing a celebrity outsider. He didn’t come up through a traditional fashion pipeline. He came up through Oxford. That gave him a deep feel for the company’s operating reality—how product gets made, how channels behave, where the risks hide, and how hard it is to change a legacy business without breaking it. His background includes a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and he previously served as Chief Executive Officer of Ben Sherman (Manufacturing) Ltd.

The structure Oxford built around its portfolio reflects that same preference for clarity and accountability. Each brand runs with real autonomy under a brand president model. Douglas B. Wood has been Chief Executive Officer of the Tommy Bahama brand since 2016, after serving as President and Chief Operating Officer there. Before Tommy Bahama, his career included roles at Boeing Defense and Space Group and McCaw Cellular/AT&T—an unconventional résumé for an apparel executive, but a useful one for a brand where experience, operations, and hospitality matter as much as merchandising.

The result is a decentralized system: brand leaders own the voice, the customer, and the creative direction, while the corporate center provides capital allocation discipline and shared capabilities. It’s not identical, but the logic resembles the Berkshire Hathaway approach—autonomous operators, paired with a parent company that focuses on resources, guardrails, and long-term value.

And then there’s geography. Oxford is headquartered in Atlanta, not New York or Los Angeles. That matters. It reinforces a Southern business culture built on long-term relationships, steady decision-making, and community ties. It also shows up in how the company behaves financially. Oxford has paid quarterly dividends consistently since 1960—an unusually long streak that signals discipline and a commitment to returning capital to shareholders.

Tom Chubb once captured the balancing act at the heart of Oxford’s culture: “A lot of companies have a hard time moving past their history. But we didn’t get so mired in our heritage that we couldn’t move forward.” That’s the throughline—hold onto the values that made the company durable, but stay willing to rebuild the business when the old model stops working.

XI. Strategic Frameworks & Analysis

To really understand Oxford Industries, it helps to stop thinking like a shopper and start thinking like a strategist. Oxford isn’t competing with “better shirts.” It’s competing with attention, loyalty, and the right to charge full price in a category that loves to discount.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants (Moderate): Starting an apparel brand has never been easier. A digital-native label can spin up product, buy ads, and sell direct without ever opening a store. But building what Oxford owns—lifestyle brands with real communities and decades of emotional equity—takes time, patience, and consistent execution. That’s harder to copy than a product line.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low): Oxford isn’t captive to one factory or one region. It sources globally through a diversified network, which limits any single supplier’s leverage. The company’s advantage here isn’t owning production—it’s orchestrating it.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Moderate): In wholesale, big retailers can still push on price and terms. But Oxford dramatically weakened that force by shifting most of its business to direct-to-consumer—about 80% of sales through channels it controls. When you own the storefront, the website, and the customer data, the “buyer” has a lot less power.

Threat of Substitutes (High): Apparel is always under attack from the next thing: fast fashion, athleisure, and whatever shift in taste is coming next. Consumers can swap brands with a click. That’s why Tommy Bahama and Lilly Pulitzer matter: their staying power is unusual in an industry where relevance is fragile.

Competitive Rivalry (High): The premium lifestyle space is crowded and noisy. Oxford competes with brands like Vineyard Vines and also with larger players like PVH Corp and Tapestry. In a market like that, you don’t win by being slightly better—you win by being meaningfully different, with an identity and experience customers can’t get elsewhere.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: Limited. Oxford doesn’t win on being the cheapest producer, and it isn’t big enough to out-scale the giants on cost.

Network Effects: Weak. Clothing doesn’t get more valuable because more people wear it in the way a social network does.

Counter-Positioning: STRONG. This is Oxford’s clearest structural advantage. The DTC-plus-restaurants model is a different operating system than the wholesale-heavy approach many competitors still rely on. For a wholesale-dependent brand, trying to copy Oxford means risking channel conflict and cannibalizing the very relationships that pay the bills. Oxford built an experience moat that’s hard to replicate without tearing up someone else’s business model.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Customers build preferences—fit, feel, and an emotional connection to the brand. But there’s nothing stopping them from testing a competitor the next time they shop.

Branding: STRONG. Oxford’s best brands sell a feeling as much as a garment. Lilly’s Target collaboration frenzy showed how intense that devotion can be. Tommy Bahama’s “island life” positioning creates a durable emotional hook that goes beyond trends and features.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE. Oxford owns valuable brand IP and has built strong positions in prime resort-market locations. Those advantages are meaningful, but not untouchable.

Process Power: MODERATE. Oxford has built a repeatable playbook: acquire lifestyle brands with real followings, keep their voice intact, and then grow them using Oxford’s sourcing, capital, e-commerce, and real estate capabilities. That institutional muscle makes execution easier for Oxford than for a first-time acquirer trying to stitch together a portfolio.

Key Strategic Insights:

Oxford’s edge comes down to two things: Branding and Counter-Positioning. Its best brands trigger emotion—relaxation, optimism, escape—and the business model reinforces that by selling directly and wrapping the product in experience.

The portfolio strategy adds another layer of resilience. Different brands bring different customers, seasons, and geographies, while the parent company provides shared infrastructure and discipline. That reduces single-brand dependence without turning everything into the same beige corporate product.

But the risks don’t disappear. Oxford sells premium discretionary goods, which means downturns hurt. Fashion risk is real; brand heat can cool. And while wholesale is no longer the center of gravity, the remaining 20–30% of revenue still leaves Oxford exposed to the ongoing decline and consolidation of department stores.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

Oxford Industries has a rare mix: genuinely differentiated brands, an operating model that keeps control close to the customer, and a management team that has already proven it can reinvent the company when the old playbook stops working.

Proven Track Record: Oxford didn’t stumble into its current identity—it built it. Over two decades, management executed a deliberate pivot from licensing and manufacturing into owning and scaling lifestyle brands. Tommy Bahama and Lilly Pulitzer weren’t just acquisitions; they were proof that Oxford could buy brand equity and then compound it.

Premium Margins: Gross margins above 60% are what “brand power” looks like in financial form. The shift to direct-to-consumer matters here: selling through your own stores and sites doesn’t just lift margins versus wholesale, it also gives Oxford better visibility into demand and customer behavior.

Experiential Moat: The restaurants and resort strategy makes Tommy Bahama harder to copy. Plenty of companies can design shirts; far fewer can create a place customers choose to spend an evening—or a weekend—that also feeds retail traffic and brand attachment.

Balance Sheet Strength: Oxford has emphasized shareholder returns for decades, including paying quarterly dividends consistently since 1960 and using share repurchases opportunistically. By the end of fiscal 2023, it had also reduced borrowings meaningfully, giving it flexibility in a volatile retail environment.

Demographic Tailwinds: Tommy Bahama’s core customer has long been affluent boomers, a group with real spending power. Layer on work-from-anywhere and the continued normalization of casual, vacation-leaning wardrobes, plus the travel recovery that benefits resort-oriented brands, and the demand backdrop is still supportive.

Acquisition Optionality: Oxford has shown it can identify brands with real followings, buy them at a reasonable moment, and scale them with its infrastructure. A strong balance sheet keeps the door open to future deals.

The Bear Case:

Oxford’s strengths don’t exempt it from the core risks of apparel—and investors should treat those risks as real, not theoretical.

Category Risk: Apparel is discretionary and cyclical. In downturns, consumers delay purchases, trade down, and wait for promotions. Premium lifestyle brands can feel that pressure faster because they’re not “need-to-have” staples.

Brand Fatigue Risk: Tommy Bahama staying relevant for roughly 30 years is impressive—and rare. But longevity cuts both ways: the island-life positioning has worked incredibly well for its core customer, yet younger consumers may not connect to it in the same way.

Geographic Concentration: Oxford has meaningful exposure to Florida and coastal resort markets. Those markets have been strong in recent years, but they’re still subject to real estate cycles and shifting migration patterns.

Recent Softness: In 2024, Oxford reported revenue of $1.51 billion, down from $1.57 billion in 2023. For 2025, it projected net sales of $1.475 billion to $1.515 billion and adjusted earnings per share of $2.80 to $3.20, citing a tough retail environment and significant tariff headwinds.

Tariff Exposure: With substantially all products sourced overseas, Oxford is exposed to trade policy shifts. Higher tariffs can squeeze margins, especially in a consumer environment that may not tolerate price increases.

Department Store Dependency: Even after the pivot, wholesale is still a meaningful piece of revenue. Department store consolidation and ongoing traffic declines remain a structural risk.

Acquisition Risk: Oxford’s strategy depends on buying and scaling the right brands. Ben Sherman is the cautionary tale: not every label fits culturally or strategically, and not every acquisition compounds.

What to Monitor:

The clearest signals for whether Oxford’s playbook is still working show up less in the headline revenue number and more in a few operating truths:

-

Comparable Store Sales Growth: This is the cleanest read on organic demand. Strong comps usually mean the brand is healthy; weak comps often show up before bigger problems do.

-

Direct-to-Consumer Mix and Full-Price Selling: How much of the business runs through Oxford-controlled channels—and how much sells at full price versus on promo—tells you whether the company is maintaining pricing power and protecting brand equity.

If those two indicators hold up, Oxford’s model stays intact. If they crack, the story changes fast.

XIII. Lessons for Founders & Investors

Oxford Industries’ transformation offers lessons that reach well beyond apparel.

The Power of Strategic Transformation: Oxford didn’t “optimize.” It reinvented itself—first from contract manufacturer, then into licensing, and eventually into an owner of lifestyle brands. Most companies never pull off pivots that big. The ones that do tend to share a few traits: they admit when the old model is dying, they make uncomfortable bets before they’re forced to, and they stay patient long enough for the new model to actually take root.

Own the Customer Relationship: Moving from wholesale to direct-to-consumer wasn’t a channel tweak—it was survival. When department stores controlled the customer, Oxford lived downstream from other people’s decisions and other people’s discounting. When Oxford built its own stores, websites, and customer file, it gained pricing power, feedback loops, and loyalty. The broader lesson is simple: intermediaries take leverage. Direct relationships create it.

Brand Beats Manufacturing: In Oxford’s early decades, the edge was operational excellence—cutting, sewing, shipping at scale. By the 2000s, that advantage had been competed away and globalized. Value migrated to the intangibles: brand equity, trust, and an emotional connection. Manufacturing can be hired. Brand has to be earned.

Portfolio Diversification: A single brand can be a rocket ship—or a single point of failure. Oxford’s portfolio spreads risk across different customers, aesthetics, and seasonal rhythms. When one brand hits turbulence, another can stabilize the overall business. But portfolio strategies only work with discipline: buying the right assets, integrating without homogenizing, and being honest about what fits.

Experience Matters: The restaurant strategy looked weird until you viewed it the way Oxford did: as brand-building with a profit-and-loss statement attached. A meal, a drink, live music—those aren’t just “nice extras.” They turn a label into a place in someone’s life, and they create a level of attachment that a rack in a department store can’t replicate.

Patient Capital Wins: Oxford’s transformation took decades. The Tommy Bahama acquisition didn’t instantly turn the company into a DTC powerhouse, and the operational shift away from licensing and manufacturing was slow and, at times, painful. But the compounding came from staying the course long enough for the new model to become the default.

When to Exit: Knowing what to stop doing is a strategy, not a footnote. Oxford didn’t just add Tommy Bahama and Lilly Pulitzer—it systematically sold or shut down pieces of the old business that no longer matched where it was going. Even when exits were painful, like Ben Sherman, they cleared focus and capital for the businesses that actually compounded.

Acquisition as Transformation: Sometimes the capabilities you need can’t be built quickly enough from the inside. Oxford didn’t try to “invent” Tommy Bahama in Atlanta; it bought a brand with real equity, then learned how to operate it and scale it. The core competency became not creation, but selection, integration, and stewardship.

Culture Eats Strategy: Oxford’s Southern roots, long time horizon, and leadership continuity made a 20-year reinvention possible. Not every organization can tolerate shrinking revenue in the short run to build a better business in the long run. Strategy is only as good as the culture that has to execute it.

XIV. Epilogue & Future Outlook

As Oxford moved into 2026, the backdrop looked a lot less forgiving than the post-pandemic surge. In Q3 fiscal 2024, consolidated net sales fell to $308 million from $327 million a year earlier. Oxford posted a loss of $0.25 per share, versus earnings of $0.68 in the prior-year quarter. And it wasn’t only demand. Two major hurricanes in the Southeastern United States created real, physical disruption—management estimated about $4 million in lost sales and roughly a $0.14 per share impact.

That’s the new version of risk for Oxford: not whether the company can escape an obsolete business model, but whether it can keep compounding in a world where premium apparel demand swings, weather can erase a week of selling, and consumer attention is more fragmented than ever.

Back in 2003, the question was survival: could a legacy manufacturer reinvent itself? Today, the questions are more nuanced—and in some ways harder. Can Oxford find a fourth brand that belongs in the same sentence as Tommy Bahama and Lilly Pulitzer? Can international expansion become a real growth vector instead of an expensive distraction? And can these brands stay relevant as the customer base shifts over time?

International Opportunity: Tommy Bahama’s “island life” fantasy isn’t uniquely American. In theory, it travels. In practice, international expansion demands investment and operating muscle—real estate, logistics, localization—that many American lifestyle brands underestimate. The opportunity is there, but it’s not automatic.

Generational Questions: Tommy Bahama’s core customer skews older. That’s a strength—affluent, loyal, and repeat-driven—but it also creates a clock. The hardest trick in brand building is broadening appeal without breaking what made the brand work in the first place. Attracting younger consumers without alienating existing ones is one of the most difficult problems in retail.

Sustainability Demands: Expectations are rising, especially among younger shoppers, around sustainability and ethical production. Oxford has made commitments to responsible sourcing, but apparel is still resource-intensive by nature. Meeting the next wave of consumer standards will require ongoing effort and investment, not just marketing.

Digital Native Competition: Digital-first brands are built around customer acquisition, content, and rapid feedback loops. Oxford has invested heavily in e-commerce, but “good at digital” keeps getting redefined. The landscape shifts fast, and staying sharp is now table stakes.

Acquisition Pipeline: The playbook that rebuilt Oxford still depends on finding the right brands at the right moment. Management has historically been patient—disciplined but opportunistic. The October 2023 acquisition of Jack Rogers footwear signaled that Oxford is still looking, and still willing to expand the portfolio when the fit is right.

Could Oxford Be Acquired? At current valuations, a portfolio like Oxford’s could draw interest from larger strategics or private equity—especially given that the company’s enterprise value can screen as a discount versus pure-play branded peers. But Oxford’s identity is shaped by long tenure, long memory, and the Lanier family legacy. This has never been a company that feels built to sell.

The Meta-Lesson: Oxford’s story is proof that sometimes the best business model is the one you pivot to—not the one you started with. The Lanier brothers who bought a military uniform maker in 1942 couldn’t have pictured a future that included restaurants, resorts, and silk Hawaiian shirts. But the throughline wasn’t luck. It was the willingness to accept hard truths early, make uncomfortable bets, and execute patiently for decades.

Oxford stands as one of the more successful reinventions in American retail: from commodity manufacturing to brand-led lifestyle business; from wholesale dependency to direct-to-consumer dominance; from fighting for pennies to earning premium margins.

The next chapter isn’t written yet. But if Oxford’s history teaches anything, it’s that this company doesn’t cling to the past when the world changes. It adapts—while holding onto the cultural steadiness that made a multi-decade transformation possible.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music