OneSpaWorld Holdings: The Story of the World's Largest Cruise Ship Spa Operator

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

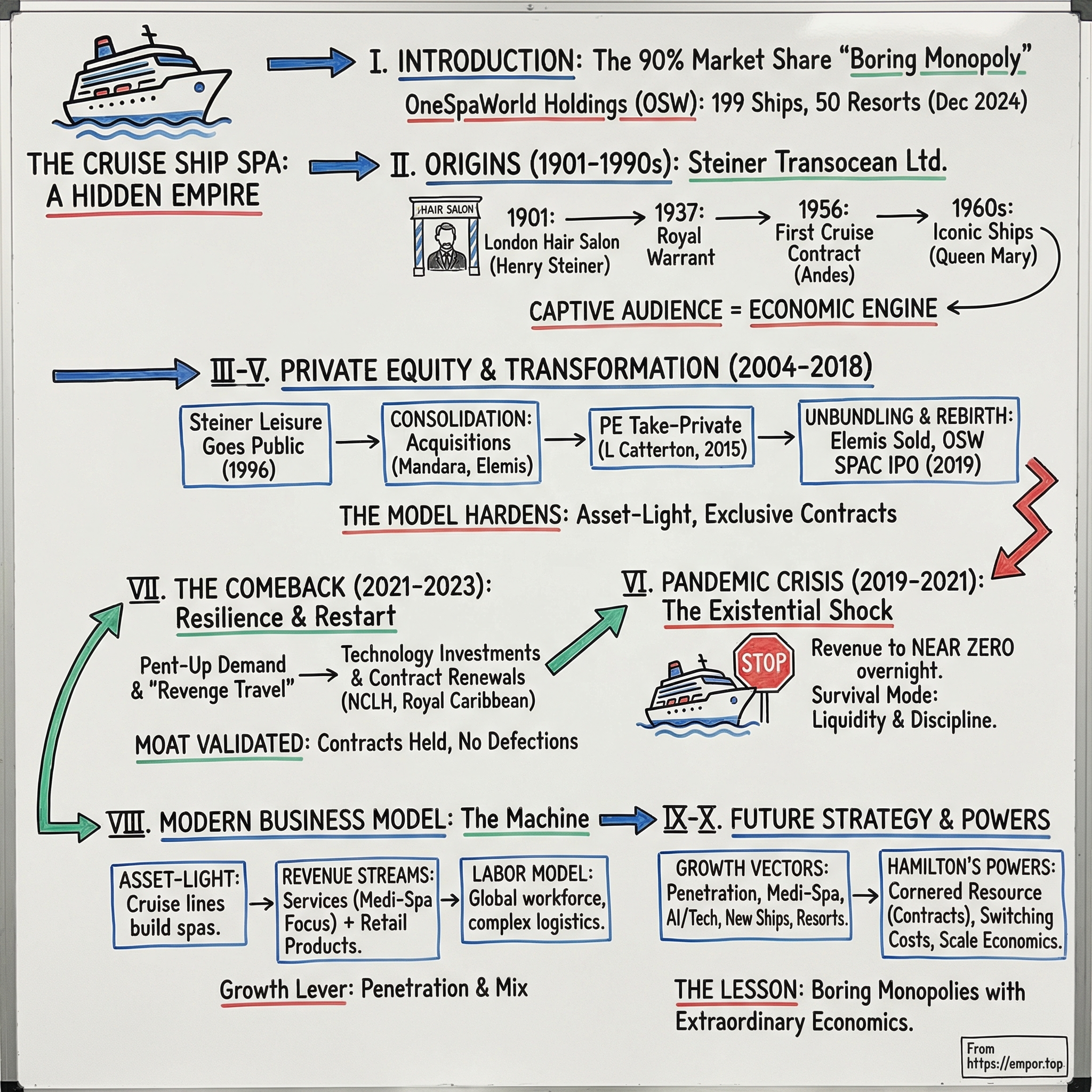

Picture this: you’re on the deck of a Royal Caribbean mega-ship, three days into a Caribbean cruise, when the morning announcement invites you to a “relaxation seminar” at the onboard spa. You wander in thinking you’ll see a massage menu and maybe a few facials. Instead, you find a sprawling wellness hub offering everything from traditional treatments to Botox injections, CoolSculpting, and acupuncture. The staff speaks a dozen languages. The shelves are lined with luxury products you don’t recognize. And behind it all, running with quiet, almost invisible precision, is a company most passengers have never heard of: OneSpaWorld Holdings.

Here’s the part that should make you sit up. OneSpaWorld controls more than 90% of the outsourced maritime wellness market. In an economy where dominance rarely lasts, this company has built — and held — a near-monopoly on cruise ship spa operations for decades. As of December 31, 2024, OneSpaWorld managed health and wellness centers on 199 cruise ships and in 50 destination resorts.

So how did that happen? How does a business that started as a small UK beauty salon more than a century ago end up as the undisputed operator of wellness at sea?

The answer runs through transatlantic steamships, private equity reinvention, and one of the cleanest real-world examples of captive-market economics you’ll ever see. It also includes a brush with extinction during COVID-19 — the moment when the entire cruise industry went dark and OneSpaWorld’s revenue effectively vanished overnight.

In this episode, we’ll follow the full arc: from Henry Steiner’s west London hair salon in 1901 to a public company generating nearly a billion dollars in annual revenue. We’ll dig into the private equity playbook that professionalized the business and consolidated the industry, the pandemic crisis that nearly broke it, and the comeback that followed. And along the way, we’ll break down what makes OneSpaWorld’s model so defensible — and why it’s a master class in building a “boring monopoly” with extraordinary economics.

The themes are timeless: the power of captive customers, the strategic value of long-term exclusive contracts, the way private equity manufactures category leaders, and the operational toughness required to survive an existential shock. If you’re an investor, a builder, or just someone who loves discovering hidden empires in plain sight, this one’s for you.

II. The Founding Era: Steiner Transocean Ltd. Origins (1901–1990s)

OneSpaWorld’s story begins far from the open ocean. It starts in west London in 1901, when Henry Steiner opened a single hair salon — a small, service-business bet in an Edwardian city full of them. Steiner himself was part of the broader wave of European immigrants who helped shape London’s early twentieth-century service economy, and his little shop built a reputation for fashionable, continental styling that appealed to well-heeled clients.

The salon didn’t just survive; it gained stature. In 1926, Henry’s son joined the business, and a little over a decade later, in 1937, the company received a Royal Warrant from Queen Mary. That detail matters. A Royal Warrant wasn’t just a plaque on the wall — it was a credibility accelerant. Suddenly, Steiner wasn’t simply a local salon; it was officially endorsed at the highest level of British society. The client list broadened to include aristocrats, prominent social figures, and, over time, Hollywood stars passing through London.

Still, none of that explains how a single London salon becomes the force behind wellness on nearly every major cruise ship. The real inflection point came mid-century, when Steiner made a leap that would define the next several decades of the business.

In 1956, Steiner won its first cruise ship contract, operating the salon onboard Royal Mail Lines’ Andes, as well as ships of the Cunard Line. More ships followed — including the Queen Elizabeth — and Steiner began showing up on the great transatlantic liners of the era, across operators like Cunard, P&O Cruises, and Royal Mail Lines.

The business logic was almost unfair. On land, a salon is one option among many. On a ship, there is exactly one. Passengers are effectively trapped — in the best possible way — inside a floating resort, and if they want a haircut, a blowout, or a bit of pampering before a formal night, they can’t just walk down the street to a competitor. This captive-audience dynamic would become the company’s economic engine.

At first, the onboard offering was simple: a handful of hairdressers providing cuts and styling for passengers who wanted to look sharp for dinner. But over time, the footprint expanded. Steiner added treatment rooms. Then fitness facilities. The offering slowly shifted from grooming to beauty, then from beauty to wellness — the early outline of what would eventually become the modern cruise-ship spa.

Along the way, Steiner deepened relationships with the most iconic ships in the world. Its history includes opening a hair salon at sea onboard Cunard’s Queen Mary in 1967, followed by the Queen Elizabeth II. These weren’t just contracts; they were flagship platforms — places where reputations were built and where partnerships, once formed, tended to last.

During this period, the operating model also hardened into something repeatable. Steiner ran under concession agreements: the cruise line provided the space and the passenger traffic; Steiner provided the staff, the know-how, and the products — and the two shared in the revenue. The build-out was typically funded by the cruise lines, while Steiner carried the day-to-day operating costs.

By the 1990s, the company had expanded from a single London storefront into a global operation across dozens of ships. But it was still, fundamentally, a family-controlled business — profitable, respected, and established, yet not fully industrialized. That next step would require a more aggressive playbook.

A preview of what was coming arrived in 1994, when Steiner purchased Coiffeur Transocean and became known as Steiner Transocean Limited. The acquisition knocked out a meaningful competitor and brought additional relationships, markets, and experienced staff — the first clear move toward consolidation.

Looking back, the most important asset Steiner built in this era wasn’t just operational expertise. It was trust and embeddedness. Those early partnerships with Cunard and other cruise operators in the 1950s and 1960s laid the groundwork for the long-term, sticky contracts that would later become extraordinarily hard to dislodge — the kind of early positioning that looks small at the time, and inevitable in hindsight.

III. The Private Equity Inflection: Steiner Leisure Goes Public (2004–2010)

Steiner Leisure began trading on the NASDAQ under the ticker STNR on November 22, 1996. Going public was the moment Steiner stopped being “the Steiner family’s cruise salon business” and started becoming an institution—one with outside shareholders, public-market expectations, and access to real capital.

But the deeper shift came after the listing, as professional managers and sophisticated investors leaned into what had been hiding in plain sight for decades: the cruise spa business had unusually attractive economics.

The pitch practically wrote itself. Cruise lines were building bigger ships that carried more passengers. Wellness was becoming a mainstream consumer spend category. And once people were on vacation—already in the mindset to treat themselves—they were surprisingly willing to pay premium prices for massages, facials, and products.

Even better, the competitive dynamics were lopsided. Steiner’s roots on iconic ships like the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth II in the 1960s weren’t just a fun historical footnote—they were a signal of how long these relationships could last, and how hard they could be to replace once embedded.

Which raises the obvious question: why didn’t the cruise lines just run the spas themselves?

Because “a spa” on a ship isn’t just a few massage rooms and a menu. It’s a specialized operation: treatment protocols, product sourcing, intensive staff training, and compliance across a patchwork of international rules. Cruise lines are world-class at moving floating resorts around the planet, feeding thousands of passengers a day, and running entertainment at scale. Recruiting and managing a rotating global workforce of massage therapists, aestheticians, and nail technicians isn’t their core business—and it’s not a business most of them wanted to build.

The outsourcing structure also made the decision easy. Under the revenue-sharing model, cruise lines took a percentage of every treatment and product sale while avoiding the day-to-day operational risk. Steiner got the space and the foot traffic—effectively the best “real estate” on the ship—without paying rent. When the spa did well, everyone won.

Then the 2000s supercharged the whole system. As the cruise industry boomed, new ships launched with larger, more elaborate spa facilities. The mega-ship era—pioneered by Royal Caribbean’s Voyager-class and Carnival’s Destiny-class vessels—turned ships into floating cities, and the wellness areas expanded right along with them. Steiner wasn’t just winning contracts for these new builds; it was often involved early, shaping layouts and helping design the experience from the planning stages.

Around the same time, Steiner pushed beyond services and into retail. It acquired Elemis, a British luxury skincare brand, and made it a core part of shipboard operations. Now, after a facial, passengers could buy the exact products used during the treatment—turning the spa into a store, not just an appointment book.

Elemis wasn’t a throw-in. Founded in 1990 by chief executive Sean Harrington and fellow directors Noella Gabriel and Oriele Frank, the brand became known for hero ranges like Pro Collagen and the expanded Superfoods line. It carried premium positioning and built a loyal customer base well beyond cruising. Under Steiner’s ownership, Elemis expanded into department stores, hotels, and airlines—distribution that reached far past the gangway.

From an investing standpoint, this era had one especially powerful attribute: consistency. Steiner delivered steady performance quarter after quarter, fueled by a simple flywheel. More ships meant more spa square footage. More passengers meant more potential customers. And as wellness spending rose, so did the average ticket.

This was the moment the cruise-spa business stopped looking like a quirky niche and started looking like a machine. And once Wall Street and private equity saw the machine, they began asking the next question: if this model works so well on a handful of ships, what happens when you scale it across the entire industry?

IV. The Consolidation Machine: Acquisitions & Market Dominance (2010–2015)

By 2010, Steiner Leisure was already the name you’d most often find behind the spa doors at sea. But the company could see the next problem coming: organic growth was getting harder. Cruise lines had made their choices. New ships still meant new opportunities, but the fastest way to gain share now wasn’t to out-sell rivals ship by ship. It was to buy them.

The clearest example was Mandara Spa. Around 2000, Mandara—a Hawaii-based company that began in Bali and built a presence in resort hotels—pulled off something few could: it won spa operations aboard Norwegian Cruise Line and Silversea away from Steiner. Steiner’s response was swift. In 2001, it took a 60% interest in Mandara.

That move captured the playbook in one stroke. Instead of fighting a prolonged battle for contracts, Steiner absorbed the threat. Mandara brought resort-spa know-how, an Asian wellness heritage, and relationships with cruise lines Steiner had briefly lost. And after the deal, Steiner could pitch something cruise lines loved: a single operator that could run a spa program across different brands and guest expectations, whether the ship was mass market, premium, or ultra-luxury.

Competitors kept trying. Harding Brothers, a Bristol-based ship chandler and shipboard retail operator, pushed into spas by forming the Onboard Spa Company. Steiner didn’t wait for that business to mature. It purchased the shares of the Onboard Spa Company, taking another emerging rival off the board and folding its relationships into Steiner’s orbit.

The contract structure made these acquisitions even more potent. Once Steiner locked in a cruise line, the deal wasn’t easily contestable. Contracts typically ran seven to fifteen years, and during that period, competitors were effectively shut out. So buying a competitor didn’t just add revenue—it converted contested accounts into protected ones, without having to wait for renewals.

Steiner also kept widening the map beyond ships. Mandara, in particular, operated spas at luxury hotels and resorts around the world. That expansion helped diversify the business and built expertise that transferred back to sea: selling wellness experiences to travelers, managing premium hospitality partners, and running multi-site operations with consistent standards.

And then there was the unglamorous advantage that became almost impossible to copy: infrastructure. Steiner built a global recruiting and training engine and paired it with a logistics machine that could actually deliver. It recruited staff from dozens of countries, trained them through company academies, and deployed them onto ships sailing every ocean on earth. That meant handling visas, rotations, onboarding, inventory, and quality control—at scale, continuously, across borders. For most would-be competitors, that wasn’t just hard. It was prohibitive.

Steiner increasingly described itself as far more than a cruise-salon operator: "Steiner Leisure has built a portfolio of industry leading brands and businesses, including the global leader in spa management services on land and at sea, renowned skincare brands Elemis and Bliss, as well as the nation's largest branded cosmetic services treatment provider in Ideal Image."

But dominance comes with a new kind of ceiling. By 2015, growth was slowing—not because the core business was broken, but because Steiner already sat on virtually every major cruise line. Getting bigger now meant squeezing more from the same footprint, taking share from the last remaining competitors, or pushing into adjacent categories. Wall Street started to worry about what the next act looked like.

That’s when private equity stepped back in. On August 21, 2015, Steiner Leisure Limited signed a definitive merger agreement under which an affiliate of Catterton would acquire all outstanding shares for $65 per share in cash. The offer represented a premium of approximately 21.5% over the 90-day weighted-average closing share price. Including assumed net debt, the total transaction value was approximately $925 million.

The take-private marked the end of Steiner’s first public chapter. And it set up the most dramatic reinvention yet: a period of restructuring and repositioning, with fresh capital, sharper priorities, and the freedom to think long-term without quarterly earnings pressure.

If the story of 2010 to 2015 is about anything, it’s this: once you’re the leader in a fragmented industry, M&A isn’t just growth. It’s defense. Steiner didn’t simply outcompete rivals—it removed them, one deal at a time, and turned a strong position into something that started to look unassailable.

V. The Transformation: Private Equity Returns & The OSW Rebirth (2016–2018)

To understand the next chapter, you have to start with the buyer. In 2015, Steiner Leisure was taken private in a $925 million buyout led by L Catterton. A year later, Catterton merged with LVMH and Groupe Arnault, creating a firm with deep consumer and luxury-brand DNA—exactly the kind of owner that looks at a business like Steiner and sees parts, not a monolith.

And Steiner, by that point, really was a bundle of very different businesses living under one roof. The cruise spa operation was the jewel: capital-light, high-margin, and already the category leader. Elemis was a luxury skincare brand with a life far beyond ships. Ideal Image was a network of medical aesthetics clinics across North America. And there was even an education arm training massage therapists and skincare professionals.

L Catterton’s bet was simple: these pieces could be worth more—and run better—if they weren’t forced to move in lockstep. So Steiner began to unbundle. The business was split into One Spa, Cortiva Institute (which trained massage therapists and skincare professionals), and product-driven businesses like Elemis and Ideal Image. Instead of a conglomerate trying to be everything at once, each unit could now pursue its own strategy and be valued on its own merits.

The biggest value unlock was Elemis. Under Steiner, it had grown, but it was still tethered to a parent company whose main identity was “the cruise spa operator.” L Catterton saw what strategic buyers would pay for a standalone, premium skincare brand—and they were right.

In January 2019, L’Occitane International agreed to buy Elemis for about $900 million, its biggest deal ever, aimed at expanding in the U.S. and U.K. The implication was hard to miss: in roughly three years, L Catterton had effectively recouped almost the entire price it paid for all of Steiner Leisure—while still holding onto the core spa-operations business.

“Over decades, ELEMIS has built an enduring and truly unique brand with powerful consumer appeal across generations, a relentless focus on innovation and an unwavering commitment to high quality sourced ingredients. Since partnering with Steiner Leisure in 2015, we have worked alongside ELEMIS' talented management team to invest in its innovation capabilities.”

With Elemis monetized, the next move was to bring the remaining business—now cleaner, simpler, and more focused—back to the public markets. The route was a SPAC, Haymaker Acquisition Corp., a $330 million blank-check company led by Steven Heyer, the former president of Coca-Cola and CEO of Starwood Hotels.

On November 1, 2018, Haymaker and OneSpaWorld announced a definitive business combination agreement. The plan was for Haymaker and OSW to merge under a new holding company, OneSpaWorld Holdings Limited, and list on Nasdaq under the symbol OSW. The deal valued the transaction at $948 million.

Crucially, this wasn’t a management reset. The same leaders who had run Steiner for years stayed in the driver’s seat. Leonard Fluxman, the chairman, and Stephen Lazarus, the CFO and COO, had each spent more than 15 years leading Steiner through its long public-company run. Glenn Fusfield, OSW’s CEO since 2016, continued to lead a senior team with decades of industry experience.

The combination closed on March 19, 2019. OneSpaWorld Holdings Limited was public again—this time as a pure-play operator of cruise ship and destination resort spas, rather than a collection of loosely related wellness and beauty assets.

The name change mattered, too. Rebranding to OneSpaWorld was the company’s way of shedding the legacy “Steiner Leisure” identity and signaling a broader, more modern ambition: global reach, a wider wellness menu, and a platform designed to scale.

From an investor’s lens, it’s the private equity playbook in clean form: buy a conglomerate, separate the pieces, optimize them independently, sell the crown jewel at a premium, then take the streamlined core back to market. And they did it fast—the cycle from take-private to public company again took less than four years.

VI. The Peak & The Pandemic: COVID-19 Existential Crisis (2019–2021)

OneSpaWorld entered 2019 with tailwinds at its back. The SPAC deal had just closed, the cruise industry was humming, and wellness was moving from “nice to have” to core vacation spend. Before the world had ever heard of Wuhan, OneSpaWorld looked like exactly the kind of steady, high-cashflow niche leader public markets love.

The company’s own numbers reinforced the narrative. It slightly beat the revenue target laid out for investors, landing at $541 million for 2018. It was operating on more than 160 cruise ships, employing thousands of spa professionals worldwide, and holding exclusive relationships with virtually every major cruise line.

The market bought in quickly. The stock traded strong enough that Haymaker I was released early from its lock-up; about 150 days after closing, shares were changing hands in the mid-teens. The pitch was clean: dominant share, asset-light operations, a massive captive audience, and a management team that had been running this playbook for decades.

Then came 2020.

In the early days of COVID-19, cruise ships became headline symbols of how fast the virus could spread in a closed environment: crowded spaces, limited medical resources, and passengers cycling through ports and airports across the globe. The British-registered Diamond Princess was the first major outbreak that made the risk impossible to ignore.

Cruise lines began suspending voyages. By June 2020, more than 40 cruise ships had confirmed positive cases onboard.

For OneSpaWorld, the implications were immediate and brutal. As voyages stopped, the company temporarily suspended spa operations. One by one, every ship it served went dark. Revenue didn’t gradually decline—it effectively fell off a cliff.

“Consistent with the guidance provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, our cruise line partners have voluntarily suspended all voyages through April 30, 2020.” In those early statements, you can still hear the hope: that this was a short pause. Weeks. Maybe a couple months. Not the start of an industry-wide shutdown that would stretch on and on.

As the market absorbed what was happening, the stock collapsed. From a February 16, 2020 close of $14.80, shares fell to $3.04 by March 15 and hit a low of $2.52 later that month.

In the financials, the damage was even clearer. In 2020, revenue fell 72.7% as voyages were canceled and destination resort wellness centers closed. The question wasn’t “how bad will this quarter be?” It was existential: could OneSpaWorld survive long enough for cruising to return?

And the operational reality was grim, too. “We have a team in place actively and diligently working on travel arrangements to repatriate our shipboard employees to their country of origin. Logistics are complex, and conditions such as flight availability, port restrictions, local government authorization, and destination border closures have delayed staff repatriation.” Thousands of employees were stranded on docked ships, unable to work, waiting for flights and permissions that kept slipping.

Management moved into pure survival mode. Costs were slashed, marketing went to zero, and staff were furloughed or repatriated wherever possible. Following these actions, OneSpaWorld reduced its monthly cash burn rate to $3.6 million, including debt service. The goal was simple: stop the bleeding and buy time.

Then came the next constraint: liquidity. OneSpaWorld announced a definitive agreement to sell $75 million in common equity and warrants to Steiner Leisure Limited and its affiliates and other investors, including certain funds advised by Neuberger Berman Investment Advisers LLC, plus members of management and the board.

“We are proud to have the opportunity to increase our investment and further our partnership with OneSpaWorld. The cruise industry has shown unabated resilience for over 40 years, and for each disruption experienced, the industry has responded by returning to even higher passenger levels within 24 months. We have worked with OSW's outstanding team since 2015 and now have re-committed our resources to assist OSW during these challenging times.”

That $75 million bought runway—but it didn’t buy certainty. The CDC’s no-sail order kept getting extended. Cruise lines posted historic losses. And the bear case got louder: maybe this time was different. Maybe people were done with cruising.

In an odd twist, being public became an advantage. As the stock recovered to above $9, OneSpaWorld raised another $50 million through an at-the-market offering in December 2020—capital it likely couldn’t have accessed as easily as a private company.

“Amid a global pandemic that shuttered our operations for the majority of the year, our intense focus on ensuring the safety of our staff, strengthening liquidity, and preparing for a successful resumption of our cruise and resort operations...” That became the company’s posture through 2020 and into early 2021: keep people safe, keep cash in the bank, and prepare for a restart date that kept moving.

For investors, this period became a stress test of everything that matters when revenue goes to zero: balance sheet discipline, access to capital, and management’s ability to make brutal decisions quickly. OneSpaWorld made it through because it entered the crisis with manageable leverage, because backers stepped in with emergency funding, and because leadership treated the shutdown like what it was—an existential event.

Not everyone in the cruise ecosystem could say the same.

VII. The Comeback: Restart, Recovery & Resilience (2021–2023)

When the restart finally came, it came faster—and cleaner—than most people expected.

By mid-2022, OneSpaWorld was already talking like a business that had found its footing again. “We delivered an outstanding second quarter, highlighted by significant growth in net revenue and adjusted EBITDA compared to the second quarter last year while generating positive free cash flow.” And this wasn’t just a couple of test voyages. As of June 30, 2022, operations had resumed on 167 cruise ships and in 48 destination resort spas.

The reason was simple: the pent-up demand thesis was real. After nearly two years of lockdowns and disrupted travel, people didn’t just want to vacation—they wanted to make up for lost time. Cruise Lines International Association data captured the sentiment shift: 85% of people who had cruised before said they planned to cruise again, a figure that was even higher than before the pandemic. In other words, cruising didn’t just come back. It reasserted itself.

And when the ships filled up, OneSpaWorld benefited immediately. “Revenge travel”—that post-pandemic urge to splurge—showed up in the spa first. Passengers booked premium treatments, bought more products, and started treating wellness as part of the vacation, not an optional add-on. The broader wellness trend that had been building for years didn’t pause for COVID; if anything, it accelerated as self-care moved from indulgence to priority.

The financial comparisons looked dramatic, but the story underneath them was straightforward. In 2022, OneSpaWorld reported growth of 279%, driven partly by the fact that 2021 was still heavily impacted by COVID, and partly because more voyages simply meant more onboard spas open for business. In 2023, the company kept growing—up 45.3% year over year—fueled by an increase in average ship count of 23% as cruise lines took delivery of ships ordered before the pandemic and continued planning future capacity.

Just as important as the numbers was what didn’t happen: nobody defected. When cruising resumed, no major cruise line used the disruption as a chance to switch spa operators. The exclusive contracts held. The relationships endured. The “embeddedness” Steiner had been building since the mid-century era proved to be exactly the kind of moat that matters when the world breaks.

Management leaned into that narrative. “As the preeminent operator of health and wellness centers at sea and on land, I am even more confident today that we are stronger than prior to the pandemic.” It wasn’t just chest-thumping. The company had survived the worst-case scenario and reopened at scale—an outcome that, in hindsight, validated both the business model and the operating discipline.

One reason the restart worked so well is that the shutdown created an unusual gift: time. OneSpaWorld used it to invest in technology that would have been hard to roll out in a fully humming fleet. Digital booking, dynamic pricing, and more personalized marketing made operations more efficient and helped drive higher revenue per passenger once demand returned.

And as the industry normalized, contract renewals reinforced the company’s position. OneSpaWorld entered a new agreement with Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings, under which OSW became the exclusive provider of spa, medi-spa, fitness, beauty, and wellness services. The agreement had a seven-year term and covered the 29 ships then sailing across Norwegian Cruise Line, Oceania Cruises, and Regent Seven Seas Cruises fleets, plus eight new ships anticipated to enter service during the term.

Royal Caribbean and Celebrity Cruises disclosed new agreements on March 12, 2024, saying the contracts began on January 1, 2024. Royal Caribbean had been contracting with OneSpaWorld for more than 30 years—exactly the kind of continuity that makes the company’s near-monopoly so hard to dislodge.

For investors, the lesson of 2021 through 2023 was bigger than a rebound. It was proof of antifragility. OneSpaWorld went through an existential shock, held its partnerships together, upgraded its capabilities, and came out looking more defensible than it did going in.

VIII. The Modern Business Model: How OneSpaWorld Actually Works

To really understand OneSpaWorld, you have to zoom in from the big, dramatic arc—century-old origins, private equity, COVID survival—and look at the machine itself. Because the company’s near-monopoly isn’t built on hype. It’s built on a model that’s unusually clean: asset-light operations, recurring contracts, and the best kind of demand curve—customers who are already onboard and can’t take their business down the street.

Start with the asset-light part. On most ships, the cruise line pays to build the spa and keeps it maintained. OneSpaWorld doesn’t show up with construction crews; it shows up with an operating playbook. So when Royal Caribbean decides a new ship should have a massive wellness complex, Royal Caribbean funds the build-out. OneSpaWorld supplies the staffing, the training, the menu, the products, the pricing strategy, and the day-to-day execution that turns square footage into revenue.

That’s the fundamental advantage versus most hospitality businesses. Hotels sink capital into real estate. Restaurants buy equipment and build kitchens. Retailers pay for fixtures and carry inventory risk across locations. OneSpaWorld gets to walk onto a finished facility, flip the lights on, and start selling.

From there, the engine runs on two revenue streams: services and product sales. In fiscal 2024, OneSpaWorld generated total revenue of $895.0 million—$723.3 million from services and $171.7 million from product revenue. Services are the anchor, and retail is the high-margin add-on that turns a treatment into a basket.

Service revenue is what you’d expect—massages, facials, salon services—but the real evolution has been what sits at the top of the menu. More than a decade ago, OneSpaWorld pushed onboard spas into a new category by adding Medi-Spa offerings. It became the first wellness provider to bring cosmetic medical services to the cruise industry, and rolled those rejuvenation treatments out across every major and luxury cruise line.

That shift matters because Medi-Spa services change who walks through the door—and how much they spend. Treatments like Botox, dermal fillers, and CoolSculpting carry premium price points and pull in passengers who might not be tempted by a classic Swedish massage. Cruises also happen to be an ideal environment for it: people have time, privacy, and a built-in “recovery window” while the ship keeps moving. You can do a procedure, take it easy, and step off the gangway looking like you slept for a week.

OneSpaWorld has continued leaning into that expansion. By Q1 2025, medi-spa services were available on 148 ships, up from 142 in Q1 2024.

Then there’s the retail layer. A passenger tries a facial, likes the results, and the therapist recommends the products used during the treatment. That’s not incidental—it’s designed. Product sales complement services by lifting each guest transaction, and it gives OneSpaWorld a way to extend the relationship beyond the appointment itself.

All of this sits inside revenue-sharing contracts with cruise lines, which is where the incentives lock together. Cruise lines get a share of spa revenue without having to recruit, train, and manage a global wellness workforce. OneSpaWorld gets high-traffic “real estate” onboard and a steady stream of vacationers primed to spend. The longer the relationship runs, the more operationally embedded OneSpaWorld becomes—which is why those contracts function like both revenue and defense.

The hardest part to replicate—and one of the biggest reasons new entrants struggle—is the labor model. OneSpaWorld’s workforce spans 88 nationalities, with shipboard retention exceeding 70%. The company recruits globally, trains through its academies, then deploys staff based on language needs, technical skills, and regulatory credentials. And it does all of that while navigating visas, maritime labor conventions, and tax and compliance regimes that vary by itinerary. It’s the kind of operational complexity that doesn’t show up in a marketing deck, but it absolutely shows up in a competitor’s failure rate.

Here’s the punchline: because the audience is so large, OneSpaWorld doesn’t need every passenger—it only needs a small slice. The company only needs to serve roughly 10% of cruise passengers to meet its financial targets. If that penetration rate inches up—driven by new, higher-value offerings like CoolSculpting—the upside can be meaningful, because incremental spa guests drop into an already-built, already-staffed system.

So if you’re trying to track how healthy the business really is, the best signals aren’t the headline revenue totals. They’re the operating indicators underneath: (1) revenue per passenger day, which captures both penetration and average ticket; (2) treatment penetration rates, showing how many passengers convert into spa customers; and (3) contract renewal rates, which tell you whether the relationships powering the whole machine are holding—and on what terms.

IX. The Competitive Landscape & Market Position (2024–Present)

With more than 90% share of the outsourced maritime health and wellness market, OneSpaWorld sits in a position that almost never survives in modern business: it’s the default answer. Its footprint isn’t just massages and facials. It spans full spa operations on cruise ships and at resorts, fitness and pain-management therapies, medi-spa treatments, nutrition programs, and even an online channel for product sales.

That kind of concentration leads to the obvious question: if this business is so attractive, why hasn’t a real competitor broken through?

Because the game is rigged—in the structural sense, not the scandal sense. The barriers are punishing.

First, contracts. When OneSpaWorld signs a multi-year exclusive agreement, that account is simply unavailable. A seven-year exclusive deal with a group like Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings doesn’t just mean stability for OneSpaWorld; it means there’s no seat at the table for anyone else until renewal time.

Second, switching costs disguised as “guest experience.” Cruise lines don’t choose spa operators the way they choose soap suppliers. Swapping operators risks service gaps, unhappy passengers, and operational headaches across an entire fleet. Even if a challenger promises marginally better economics, cruise lines tend to prize reliability and consistency over a slightly higher revenue share.

Third, the operational complexity is the moat. Running a spa on land is hard. Running one at sea is a different sport: global recruiting pipelines, training standards, regulatory and credential requirements, product sourcing, and systems that can coordinate thousands of staff members rotating across dozens of ships. Those capabilities take years to build, and they only get cheaper and better with scale—exactly where OneSpaWorld already has the advantage.

There are competitors, but they’re narrow. Beyond Steiner’s legacy and OneSpaWorld’s dominance, Canyon Ranch is the only other meaningful operator with a shipboard presence. It has carved out space on Cunard’s Queen Mary 2 and on the seven ships of Oceania and Regent within the Prestige Cruises group. That’s real, but it’s also telling: Canyon Ranch shows up where its premium wellness brand fits the guest profile—on a small number of luxury ships—rather than competing head-on across the mass-market fleet.

Then there’s the idea people always raise when they see a near-monopoly: why don’t the cruise lines just do this themselves?

In theory, they could. In practice, they don’t want to. Cruise companies are great at sailing ships, selling vacations, and running hospitality and entertainment at industrial scale. Spa operations are a specialist business with its own staffing, training, compliance, and merchandising muscles—none of which sit naturally inside a cruise line’s core DNA. And the revenue-sharing model makes outsourcing even more appealing: cruise lines participate in the upside without taking on the operating risk. If spa demand softens, the cruise line’s take shrinks too—but the fixed operational burden stays with OneSpaWorld.

Land-based wellness brands also haven’t translated into credible sea-based challengers. The maritime environment punishes operators built for hotels and city spas: international waters, shifting port rules, constrained supply chains, and staffing logistics that are far more complicated than “hire locally and restock tomorrow.” A few have tried. Most have stayed subscale or faded out.

Meanwhile, the direction of travel in the industry plays straight into OneSpaWorld’s hands. Wellness and sustainability have become mainstream consumer priorities, and cruise lines have responded by expanding wellness programming, spa services, and fitness offerings as core parts of the onboard experience. And when cruise lines decide they want bigger wellness complexes and more sophisticated menus, they tend to lean on the operator already embedded in their fleet—especially one that can help design, staff, and monetize those spaces from day one.

The other tailwind is simpler: the cruise industry keeps growing. CLIA’s 2025 State of the Cruise Industry Report forecast the sector welcoming 37.7 million ocean-going passengers in 2025, alongside a global fleet of 310 ocean-going vessels. By the end of 2025, the report projects 370 ships carrying 33.7 million passengers—up 4.9% versus 2024 and 22.4% versus 2019.

Put it together, and OneSpaWorld starts to look less like a typical vendor and more like infrastructure. For investors, the company’s position resembles a toll road: most of the industry’s traffic flows through its system, competition is boxed out by contracts and complexity, and growth in cruising tends to translate into growth for OneSpaWorld.

The real risk isn’t a rival storming the gates. It’s what hits the whole ocean at once—recessions, health crises, or a lasting shift in consumer preferences away from cruise vacations.

X. Strategy & Future Growth Vectors

At this point, OneSpaWorld doesn’t need a moonshot. When you already run the overwhelming majority of shipboard spas, the playbook is less about conquering new territory and more about getting more out of the territory you already have. The company’s growth strategy shows up in a handful of clear vectors—each incremental on its own, but meaningful in combination.

Penetration growth is the simplest lever. OneSpaWorld only needs to serve roughly 10% of cruise passengers to meet its financial targets. That means there’s a lot of headroom just by nudging more passengers through the spa doors—through smarter marketing, easier entry-point services, and better onboard promotions—without needing new ships or new contracts.

The second lever is mix: moving customers up the value chain. Medi-spa is the centerpiece here. OneSpaWorld planned to add nine new maritime health and wellness centers in fiscal 2025, bringing the total to at least 207 vessels. At the same time, it expected medi-spa services to expand to 151 ships by year-end 2025. These treatments generate premium revenue and pull in a different customer—people who may skip a traditional spa day but will absolutely consider a rejuvenation treatment when they’ve got time, privacy, and a built-in “vacation glow-up” mindset.

Technology is the quiet multiplier. Management has been explicit about pushing into AI, not as a buzzword, but as a revenue and efficiency tool: “We are currently piloting an AI-driven initiative focused on increasing revenue by enhancing yield improvement through machine learning-powered recommendations and algorithmic optimization. And in parallel, we are advancing a second group initiative centered on efficiency and automation using AI to streamline operations.” In plain English: use better algorithms to sell the right service at the right time, and automate the operational grind that eats margin in a people-heavy business.

Fleet expansion is the tailwind that keeps the whole machine moving. Cruise lines continue launching new ships, and each one needs a spa. OneSpaWorld expected to open health and wellness centers on nine new ship builds in fiscal 2025. These aren’t hard-fought competitive wins so much as the natural result of being the embedded operator when a fleet grows: new ships plug into the existing relationship.

Contract renewals are where the moat turns into economics. Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings signed a seven-year agreement covering all ships across its three brands. Royal Caribbean and Celebrity Cruises didn’t disclose the length of their renewed agreements, but they did confirm something just as important: the arrangement applies not only to existing ships, but also to any new-builds that enter service during the term. That’s the dream clause—your customer grows, and you grow with them.

Geographic expansion is the long runway. The Asia-Pacific cruise market is the most significant untapped opportunity, and Asia and China saw the biggest passenger growth, at 96%. As cruise lines deploy more capacity to Asian ports, OneSpaWorld follows the ships and brings its operating system with it.

And then there’s the diversification play: destination resorts. Cruise ships still dominate the portfolio, but resort spas offer a way to expand on land and build deeper hospitality partnerships. As of December 31, 2024, OneSpaWorld managed health and wellness centers on 199 cruise ships and in 50 destination resorts.

Against that backdrop, the company reaffirmed its fiscal year 2025 guidance, projecting revenues between $950 million and $970 million and Adjusted EBITDA between $115 million and $125 million.

The biggest strategic question hanging over all of this is brand. OneSpaWorld is, by design, mostly invisible. Guests experience “Vitality Spa” on Royal Caribbean or “Mandara Spa” on Norwegian—not OneSpaWorld. Building real consumer awareness could open up opportunities beyond the current B2B model, but it would also require meaningful investment and a different kind of positioning.

So for investors, the growth story is mostly about compounding, not transformation. OneSpaWorld should grow as cruising grows, as penetration inches higher, and as the treatment mix shifts toward higher-priced services. The truly explosive upside would require something bigger—either a dramatic expansion in cruising or entry into new markets. Both are possible. Neither is guaranteed.

XI. Playbook: Business & Investment Lessons

OneSpaWorld’s arc is fun to tell, but it’s also unusually useful. Strip away the cruise ships and sea days, and you’re left with a set of lessons that show up again and again in great businesses.

The Power of Captive Markets: When customers can’t easily go elsewhere, the economics change. Pricing gets easier, marketing gets cheaper, and churn drops. OneSpaWorld’s near-monopoly at sea is the cleanest version of that idea. But the same dynamic shows up anywhere the audience is “trapped” by context: airport concessions, stadium vendors, hospital gift shops, and theme parks.

Relationship Moats Compound Over Time: The contracts OneSpaWorld holds now aren’t just sales wins—they’re the descendants of relationships built decades ago, starting in the 1950s and 1960s. Each year of solid execution made the next renewal more likely, and each renewal made the operator more embedded. In businesses where trust and consistency matter, relationships can become a moat that’s harder to attack than technology or branding.

Private Equity Transformation Playbook: L Catterton ran a classic value-creation sequence: buy a bundled set of assets, separate them, run each business with sharper focus, monetize the most valuable piece, then bring the streamlined remainder back to the public markets. Once you learn to spot this pattern, you start seeing it everywhere—and you also get better at spotting when a “conglomerate discount” is really hiding a set of valuable parts.

Surviving the Unsurvivable: COVID-19 took OneSpaWorld’s revenue to near-zero almost overnight. The company made it through because it had manageable debt going in, moved fast to cut cash burn, secured emergency capital from committed backers, and kept preparing for a restart even when the restart date kept slipping. In a real crisis, balance sheets matter, speed matters, and execution matters more than strategy decks ever will.

Vertical Integration Trade-offs: Owning Elemis was a vertical-integration move: control the products alongside the services. Selling Elemis for $900 million later was a reminder of the other side of that coin—focus can be worth more than integration. For investors, it’s a useful filter: sometimes the combined story sounds compelling, but the standalone pieces are simply more valuable apart.

The Boring Monopoly: OneSpaWorld isn’t a consumer household name, and it doesn’t have the mystique of a tech platform. But high share, long-term exclusivity, recurring revenue, and capital-light operations can produce business quality that flashier companies would love to have. The lesson is simple: the best economics often live in the least glamorous places.

Riding Partner Waves: OneSpaWorld wins big when cruising grows, and it hurts when cruising stalls. That dependency is both the opportunity and the risk. In good times, it benefits from industry momentum without having to build demand from scratch. In bad times, there’s no easy hedge. If you invest in a partner-dependent business, you’re also making a bet on the partner industry’s long-term trajectory.

XII. Powers & Forces Analysis

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework:

Scale Economics: OneSpaWorld’s sheer size shows up as a real cost advantage. Recruiting pipelines, training programs, and supplier relationships get spread across roughly two hundred-plus locations. A challenger starting with a few ships would be running the same playbook with far higher costs per spa—and far less leverage.

Network Economics: Limited. This isn’t a business where each new customer makes the service more valuable for every other customer in the way a social network does.

Counter-Positioning: Not really applicable. OneSpaWorld didn’t win by flipping the table with a new model; it won by relentlessly refining the concession model over decades, then scaling it.

Switching Costs: High for cruise lines. Swapping spa operators isn’t like changing a vendor behind the scenes. It means renegotiating contracts, potentially reworking branding, transitioning staff, keeping service levels consistent during the handoff, and taking on the risk of passenger dissatisfaction. The operational mess alone is a deterrent.

Branding: Moderate where it matters, and weak where it doesn’t. Cruise lines know and trust OneSpaWorld. Passengers usually don’t. Guests experience “The Spa” or “Vitality Spa,” not “operated by OneSpaWorld.”

Cornered Resource: The big one. Long-term exclusive contracts with major cruise lines are scarce assets by definition—if OneSpaWorld holds the deal, a competitor simply can’t compete for that fleet until renewal. Some of these relationships run back decades, which makes them even harder to pry loose.

Process Power: The other big one, and the hardest to copy. Decades of operating in the maritime environment have created a deep institutional muscle: international recruiting and staffing rotations, maritime regulatory compliance, onboard inventory and logistics, multilingual service delivery, and consistent execution across a moving, global footprint. You don’t build that quickly.

Primary Powers: Cornered Resource (exclusive contracts) + Switching Costs + Scale Economics

Porter's 5 Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: LOW. Exclusive contracts block access to the biggest fleets, and the operational complexity keeps most would-be entrants from even trying. Building the recruiting and training infrastructure to compete at scale takes real capital, and the remaining “available” market is too small to justify that investment for most players.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW. Most beauty and wellness products have plenty of substitutes, and no single brand is essential. Labor supply, particularly from developing markets, has historically been ample. That combination limits supplier leverage.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH. The buyers are concentrated: the largest cruise groups account for a meaningful share of the market, they negotiate hard, and they can always raise the theoretical threat of bringing spas in-house. But they also know what they’d be taking on—complex staffing, training, compliance, and guest-experience risk—and that reality tempers their leverage.

Threat of Substitutes: LOW on ships, MODERATE on land. At sea, the captive-market advantage is real: there isn’t another spa down the street. On land, resort spas compete with local alternatives, though OneSpaWorld’s resort footprint is smaller relative to its cruise business.

Competitive Rivalry: LOW. OneSpaWorld’s near-monopoly position means there isn’t much head-to-head price competition. Canyon Ranch is the only other operator with meaningful shipboard presence, and it’s concentrated on a small number of luxury ships. Competition, where it exists, is more about service quality and treatment innovation than bidding wars.

Overall: Highly attractive industry structure with significant competitive advantages.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Considerations

Bull Case:

The bull case for OneSpaWorld is basically the bull case for a well-defended toll booth in a growing ecosystem.

Start with the moat. With more than 90% share of outsourced maritime health and wellness globally, OneSpaWorld isn’t just the leader—it’s the default. That kind of dominance comes with the kind of switching costs cruise lines don’t like to talk about, but absolutely feel: retraining staff, reworking onboard programs, risking guest dissatisfaction, and potentially disrupting an entire fleet’s operations.

Then there’s the tide underneath the whole business. The cruise industry has been growing, and industry forecasts continue to point up. CLIA expects 37.7 million passengers to cruise globally in 2025, rising to 41.9 million by 2028. More passengers and more ship capacity generally mean more opportunities to sell wellness services—especially for the operator already embedded across the major fleets.

The wellness mega-trend adds another layer. Post-COVID, self-care stopped being a niche indulgence and became normal behavior. And cruising itself has been broadening: in 2024, 12% of cruisers chose to sail solo (up from 6% in 2023); 28% traveled with three to five generations of family members; and 25% of repeat cruise travelers sailed two or more times a year. More variety in who’s onboard—and how often they cruise—creates more shots on goal for the spa business.

The company’s recent financial performance also supports the story that this isn’t just a rebound, but an improving engine. Income from operations rose 44% to $78.1 million versus $54.2 million in fiscal 2023. Adjusted EBITDA increased 26% to $112.1 million compared to $89.2 million in fiscal 2023. The takeaway isn’t the decimals—it’s that profitability has been moving in the right direction as revenue has scaled back up.

And the cleanest upside lever is still penetration. If only about 10% of passengers are using spa services, even small improvements can matter, because they don’t require new ships or new contracts. It’s the same facility, the same foot traffic—just a slightly higher conversion rate.

Finally, the balance sheet provides some breathing room. OneSpaWorld ended the year with $58.6 million of cash and full availability under its $50 million revolving loan facility, for total liquidity of $108.6 million. It also reduced debt to $100 million, strengthening the capital structure compared to the fragile days of the shutdown.

Bear Case:

The bear case is simpler, and it starts with the uncomfortable truth: OneSpaWorld’s fate is tied to cruising.

Cruises are discretionary travel, and discretionary travel is cyclical. The industry can be hit by recessions, geopolitical shocks, and health events, and history has already shown how quickly “full ships” can become “zero sailings.” Even with the strong recovery, the risk isn’t theoretical—it’s the same category of sudden stop that defined COVID-19.

Customer concentration amplifies that. A huge share of OneSpaWorld’s revenue comes from the top three cruise corporations: Carnival, Royal Caribbean, and Norwegian. That’s great when relationships are stable, but it also means any disruption, renegotiation, or strategic shift at one major partner can ripple through the company’s results.

Longer-term, climate change and environmental scrutiny are real headwinds for the entire cruise sector. Younger travelers are paying more attention to the footprint of cruise vacations, and regulatory pressure around emissions could raise costs and, over time, weigh on demand.

There are also labor and execution risks that don’t show up in the glossy “wellness” branding. This is a people-heavy, globally staffed business. Visas, maritime labor rules, retention, and rising labor costs can all squeeze margins, especially when demand is volatile.

And even if the business performs well, the market may not reward it with a premium valuation. OneSpaWorld has what investors often say they want—recurring contracts, scale advantages, strong cash flow—but it may still trade with a “boring business discount” if the story feels more like compounding than disruption.

Key Metrics to Watch:

1. Revenue per Passenger Day (RevPPD): This rolls penetration and ticket size into one signal. If RevPPD rises, it usually means OneSpaWorld is getting better at monetizing the passengers it already has—often the highest-quality kind of growth.

2. Contract Renewal Rates and Terms: The real moat is the contracts. Watch whether renewals happen, how long they run, and whether economics move in OneSpaWorld’s favor or the cruise line’s.

3. Same-Store Sales Growth / Average Ship Count: This separates “we grew because the fleet grew” from “we grew because we got better.” Both matter, but only one is pure operational strength.

XIV. Epilogue: Where Does OneSpaWorld Go From Here?

OneSpaWorld closed fiscal 2024 with another record year for total revenue, income from operations, and adjusted EBITDA. In practical terms, the post-pandemic chapter is over. The company is back in growth mode.

Now comes the harder question: can it keep its grip as cruising changes shape?

The mega-ship era isn’t slowing down. Royal Caribbean’s Icon-class vessels are effectively floating cities, carrying more than 7,000 passengers and offering an endless menu of things to do. That’s great for demand, but it also creates a new kind of competition onboard: every incremental dollar of passenger spending has more places to go. OneSpaWorld’s job is to keep the spa feeling like a must-do experience, not an optional afterthought buried under water parks, specialty dining, and Broadway-style shows.

Inside the company, there’s also a generational handoff underway. “Stephen’s appointment as President further underscores the strength of our leadership development culture to resource and empower our amazing people to imagine and realize value for our stakeholders across our complex global operations.” After Leonard Fluxman’s long tenure, moving leadership responsibilities to the next generation is both a continuity test and an opportunity to modernize without breaking what works.

Innovation will be a big part of that modernization. OneSpaWorld has been piloting AI-driven initiatives aimed at improving yield through machine learning-powered recommendations and algorithmic optimization, while also pursuing efficiency and automation initiatives using AI to streamline operations. The open question is whether this becomes a true edge—or simply the cost of staying world-class in a business where execution is the product.

Then there’s the biggest strategic temptation: the wellness platform dream. Expanding beyond B2B spa operations into broader health, fitness, and mental wellness sounds like the natural “next act.” But OneSpaWorld’s superpower has never been consumer branding. It’s been operational excellence inside tightly integrated cruise partnerships. Pushing into new frontiers could unlock growth, or it could dilute focus. That tension—between compounding the core and chasing the adjacent—will shape the next chapter.

Stepping back, the arc is still remarkable. Henry Steiner opened a single salon in London in 1901. The business prospered when his son joined in 1926, and it earned a Royal Warrant from Queen Mary in 1937. From that west London storefront to a global wellness operator on nearly every major cruise fleet, the story is a case study in how positioning, relationships, and relentless execution can compound over a century.

And the ultimate irony remains: OneSpaWorld is both recession-resistant and recession-vulnerable. Spa services can behave like “affordable luxury” once passengers are onboard—small splurges that survive even when people tighten budgets. But the entire platform rests on discretionary cruise travel, which can evaporate when the world turns.

For anyone who loves hidden monopolies—dominant share, high switching costs, durable contracts, and a captive customer base—OneSpaWorld is one of the cleanest examples out there. Whether it’s a great investment ultimately comes down to your belief in the long-term trajectory of cruising, your comfort with partner concentration risk, and how much you value the economic elegance of a business that sells indulgence in the middle of the ocean.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music