Old Second Bancorp: A Century of Community Banking Through Crisis and Consolidation

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

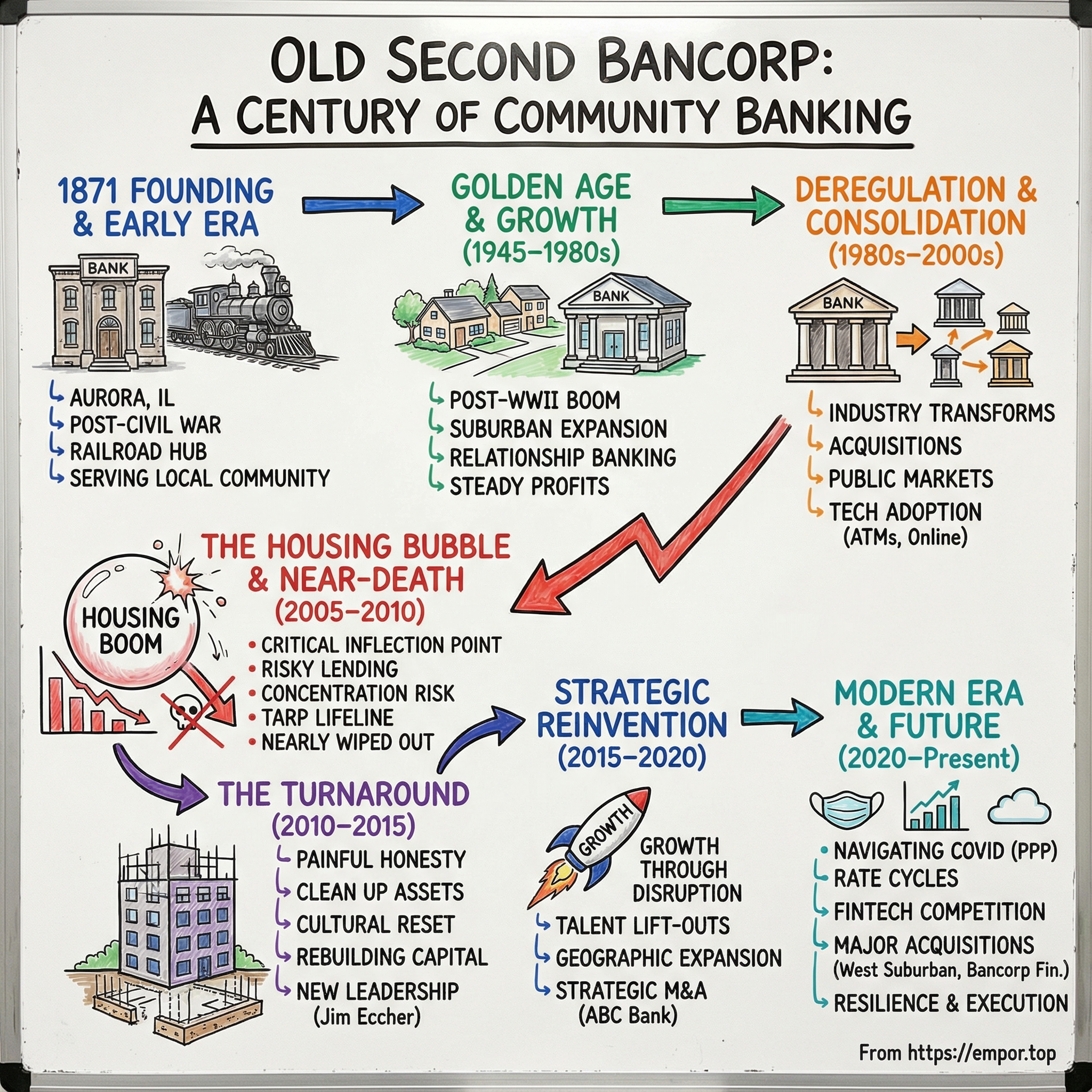

Picture this: Aurora, Illinois, 1871. The Civil War ended just six years earlier. Ulysses S. Grant is in the White House. The railroad has turned this Fox River town from a quiet agricultural stop into a humming industrial hub. And in the middle of all that post-war momentum, a group of local business leaders decides to open a bank—not to bankroll faraway speculation, but to serve the people right in front of them: farmers, factory workers, and Main Street merchants trying to build something real.

Old Second National Bank opened its doors that year. And more than 150 years later, it’s still headquartered in Aurora. Through booms and busts, Old Second grew the way community banks are supposed to grow: by helping local customers expand first, and earning trust the slow way—relationship by relationship, loan by loan.

Which makes the central question of this story hard to ignore: how does a small-town Illinois bank survive the Panic of 1893, the Great Depression, the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, and then the main event—the 2008 financial crisis—when Old Second came within a whisker of becoming another FDIC statistic… and still manage to come out stronger?

This isn’t a story about a flashy fintech or a too-big-to-fail megabank. It’s something rarer, and arguably more useful: a community bank that got in trouble, faced the consequences, and then rebuilt itself from the inside out. Today, Old Second operates across Kane, Kendall, DeKalb, DuPage, LaSalle, Cook, and Will Counties in Illinois. Its flagship bank dates back to 1871. The holding company was formed in 1982. Both remain based in Aurora.

Why does any of this matter in an era of JPMorgan Chase and fintech unicorns? Because community banks like Old Second do a job neither can fully replicate. They make relationship-based loans to small businesses that don’t fit neatly into a checkbox model. They serve families who still value face-to-face banking and a banker who knows them. And they take local deposits and cycle them back into local economies—something a distant headquarters can’t do with the same fidelity.

Over the next sections, we’ll follow Old Second through a century and a half of American banking: resilience through recurring crises, the very real dangers of growth at any cost, the hard work of cultural and leadership change, and the opportunities that show up when an industry is shaken and the nimble players move fastest.

II. Founding & Early Era: Building Community Banks in the Midwest (1871–1930s)

To understand why Old Second was founded when and where it was, you have to start with what Aurora was becoming in the decades after the Civil War: not a sleepy river town, but a node in the machinery of Midwestern growth.

Back in 1849, the Illinois General Assembly chartered the Aurora Branch Line—a short, 12-mile stretch connecting Aurora to West Chicago. On paper, it looked modest. In reality, it plugged Aurora into Chicago’s economic orbit. With capital from the East, that line evolved into the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, eventually running across Illinois to Peoria and Galesburg and on toward the Mississippi River. Grain and livestock moved east. Manufactured goods moved west. Aurora sat right in the middle of that flow.

And the railroad didn’t just pass through. It put down roots. The Chicago, Burlington & Quincy extended its line to Aurora in 1849 and soon made the town a major operating center, building repair and railcar construction shops there. Aurora wasn’t merely “on the route.” It was a railroad town—one where the shops and roundhouses employed thousands and shaped much of the city’s political, economic, and social life.

That’s the backdrop for 1871. Old Second National Bank opened its doors into a growing, industrializing community that needed a stable place to store money and a reliable source of credit. The timing mattered. The National Banking Acts of the 1860s had created a framework for nationally chartered banks and a more uniform currency. Across the Midwest, banks were forming to finance the region’s agricultural and industrial expansion. Old Second was part of that wave—but with a distinctly local purpose.

Its mission was simple and practical: take deposits from factory workers, shopkeepers, and farmers, and turn those deposits into loans that helped the community function and grow—mortgages, farm equipment, inventory financing, and the everyday working-capital needs of small businesses. No exotic financial engineering. Just relationship banking at its most fundamental: the banker knew the borrower, understood the local economy, and made credit decisions based on character and context as much as collateral.

Aurora’s civic identity helped too. Before the Civil War, the city openly supported abolitionism. It was progressive for its era in education, religion, welfare, and women’s civic life. The first free public school district in Illinois was established there in 1851, and a high school for girls followed in 1855. In a place that invested early in local institutions, a community bank wasn’t just tolerated—it was valued.

Then came the stress tests. The Panic of 1893 triggered failures and runs nationwide. The Panic of 1907 was so severe it helped spur the creation of the Federal Reserve System. And the Great Depression of the 1930s wiped out thousands of banks across America.

Old Second made it through. Not because it had cutting-edge models or some secret weapon—but because it stayed grounded: conservative lending and deep ties to the people on both sides of the balance sheet. When your depositors are your neighbors and your borrowers are the same people you see at church, at the shops, and at work, speculation has a way of looking less tempting. There’s a built-in accountability that can keep a bank from drifting too far from reality.

Aurora remained a manufacturing force through both World Wars and even through the Depression years. As long as the railroad kept operating and local industry kept producing, Old Second’s customers had the ability to keep paying their loans. From the beginning, the bank’s fortunes were tightly bound to the fortunes of its community—a bond that helped it survive early crises, and one that would become far more complicated in the decades ahead.

III. Post-War Growth & The Golden Age of Local Banking (1945–1980s)

The end of World War II kicked off what many community bankers still think of as the golden age. Glass-Steagall and strict geographic rules kept banking local and predictable. If you were a bank in Aurora, you competed with other banks in Aurora—not with a money-center giant from New York, and not even necessarily with the big names in downtown Chicago.

Meanwhile, the ground was literally shifting beneath Chicagoland. Suburbanization took off. Returning GIs started families, and the western suburbs—Aurora, Naperville, Downers Grove, Wheaton—expanded fast. Every new subdivision needed mortgages. Every new strip mall needed construction financing. Every small manufacturer needed a working-capital line to buy inventory and make payroll.

Old Second was right in the path of that growth. It expanded carefully through the Fox River Valley and into the collar counties surrounding Chicago, adding branches in a way that mirrored the outward march of the metro area itself. Branch by branch, it became part of the daily life of those communities.

By this period, Old Second looked like a classic full-service community bank: consumer and commercial products, commercial and industrial lending, consumer loans, and real estate lending. It also offered electronic banking services such as web and mobile banking, plus corporate cash management—including remote deposit capture—for business customers.

The underlying model was straightforward and durable. Bring in deposits through the branch network—checking, savings, and CDs. Lend those deposits back out as mortgages, car loans, and business credit at higher rates. That spread—what the bank earned versus what it paid—powered steady profits as long as borrowers kept paying.

And it wasn’t just interest income. Trust services and wealth management added fees that didn’t rise and fall with rates. As Aurora’s middle class built savings and started thinking about retirement, Old Second could be the bank that held your checking account, financed your home, and managed your assets over time. Those multi-decade relationships created loyalty that was hard for competitors to pry loose.

Culturally, the bank leaned conservative—sometimes almost stubbornly so. Many of the people shaping credit decisions had lived through the Depression. They cared less about how hot the market felt and more about whether a borrower could still repay when things cooled off. That mindset helped Old Second stay out of trouble through the recessions that interrupted the post-war boom.

That long memory also showed up in leadership. William Skoglund, for example, started at Old Second in 1972 as a teller, rose through a variety of roles, and became President of Old Second National Bank in 1992. He later served as President and CEO of the holding company beginning in 1998 and became Chairman of the Board in 2004. This kind of continuity reinforced the bank’s identity: steady, relationship-driven, built for the long haul.

But even in the golden age, the landscape was changing. The collar counties were turning into a major metro market, and the bigger that prize became, the more competitors would show up. The calm, protected world of local banking wouldn’t last forever—and the next era would be far less forgiving.

IV. Deregulation & Consolidation: The Industry Transforms (1980s–2000s)

The 1980s brought the biggest rewrite of American banking since the Great Depression. And for community banks like Old Second, it meant the rules that had kept competition local were suddenly evaporating.

A wave of deregulation—capped by the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act—started dismantling the geographic guardrails that had long protected hometown banks. Once those barriers came down, the industry did what industries always do when the map opens up: it consolidated. Money-center banks could buy regionals. Regionals could roll up community banks. And the deals kept coming.

Over the next few decades, the U.S. banking roster thinned dramatically. From 1984 to 2020, the number of commercial banks fell by almost 70 percent, dropping from 14,376 to 4,404. A huge chunk of that decline came in just the last stretch—between 2000 and 2020, the count fell by almost half again. Put simply: the era of thousands of small, insulated local banks was ending.

Then the savings and loan crisis hit in the late 1980s, sending shockwaves across the financial system. Hundreds of thrifts failed. Regulators were reshaped. Depositors got a blunt lesson in why FDIC insurance mattered. For survivors like Old Second, the takeaway was clear: conservative underwriting wasn’t just tradition—it was survival. But the crisis also left a vacuum. When institutions disappear, their deposits and customers don’t. The banks that stayed standing had a chance to capture both.

Old Second still faced the defining fork in the road for community banks in that era: sell to a larger acquirer and lock in a payout, or stay independent and fight it out. The Skoglund family and the board chose independence—but they also understood the catch. Independence required scale. A bank sitting around $500 million in assets couldn’t easily fund the technology and compliance buildout needed to compete with much larger players.

That’s where structure mattered. Old Second Bancorp, Inc. was incorporated in 1981 and headquartered in Aurora, Illinois. Creating a holding company gave the organization more flexibility—more tools for raising capital, and a cleaner platform for acquisitions.

Then came the leap into public markets. Old Second went public on NASDAQ in the mid-1980s, which changed the game. Public stock could become acquisition currency. Access to capital markets could finance growth. And, in theory, the scrutiny of public investors could sharpen governance. It also created a way for the Skoglund family to monetize part of its stake while keeping control.

With the new playbook in hand, Old Second started doing what so many banks did in the consolidation era: buying neighbors. In 1997, it acquired First State Bank of Maple Park. In 1999, it purchased both The Old Second Community Bank of North Aurora and The Old Second Community Bank of Aurora. In February 2000, it acquired Bank of Sugar Grove.

None of these were moonshot acquisitions. That was the point. Each deal added branches, deposits, and customers across the fast-growing collar counties—small steps that, stitched together, built real scale.

At the same time, banking was becoming a technology business whether it wanted to or not. ATMs became mainstream in the 1970s and 1980s. Online banking arrived in the 1990s. Behind the scenes, core system upgrades—expensive, disruptive, and unavoidable—became the price of admission for any bank that wanted to process more transactions, launch new products, and serve customers who expected speed and convenience. More than 50 years after the first ATM, the trend line was unmistakable: IT-based delivery, automated payment clearing, internet banking, and a growing menu of financial products.

By the early 2000s, Old Second had grown into a respected regional player, with more than $2 billion in assets and a strong franchise in Chicago’s western suburbs. The conservative culture was still there. But the ambition was rising. And just as Old Second had built the scale to compete in a tougher industry, the housing market began offering what looked, at the time, like the easiest growth opportunity in banking.

V. The Housing Bubble & Near-Death Experience (2005–2010)

The Critical Inflection Point

What happened to Old Second between 2005 and 2010 is the part of the story where a century of careful, conservative banking almost gets wiped out in a handful of years. It’s a cautionary tale—but it’s also a survival story.

First, the setup. The U.S. housing market didn’t just rise in the early 2000s; it reset people’s sense of what was “normal.” From 1998 to 2006, the price of a typical American house rose 124%. And the math stopped making sense: in the 1980s and 1990s, the median home price usually sat at roughly three times median household income. By 2004 it was about four times. By 2006, closer to five.

In the Chicago suburbs, the boom felt endless. Subdivisions were going up everywhere. Developers needed money to buy land. Builders needed construction loans. Investors wanted commercial mortgages. For a community bank rooted in those neighborhoods, the opportunity was right outside the branch doors.

And the product set was seductive. Commercial real estate and construction loans paid better than plain-vanilla residential mortgages. The borrowers were familiar—local developers the bank had known for years. The collateral was physical—land and buildings that, in that moment, seemed like they could only climb in value.

So what could go wrong?

Pretty much everything.

The downturn hit housing first, then rolled downhill into commercial real estate. As journalist Kimberly Amadeo put it: “The first signs of decline in residential real estate occurred in 2006. Three years later, commercial real estate started feeling the effects.”

Old Second was positioned in the blast zone. Its loan book had become dangerously concentrated in exactly the kind of lending that breaks a bank when values fall: CRE and construction, tied tightly to one geography. When home sales dried up, projects stalled. When projects stalled, land couldn’t be developed or sold. And when developers couldn’t refinance or liquidate, the loans stopped performing—leaving the bank holding collateral suddenly worth far less than the balances owed.

At the time, Old Second had about $1.9 billion in assets and 27 branches, largely across Chicago’s western suburbs. The retail franchise—especially along the Fox River—still had real strength. But it wasn’t big enough to absorb the wave of losses created by the bank’s earlier real estate push.

Then the metrics that kill banks started flashing red. Non-performing loans went from trivial to alarmingly high. Capital ratios dropped as losses mounted and loans were written down. Investors, smelling trouble, ran for the exits. The stock fell from the teens to pennies.

And this wasn’t happening in a vacuum. Late 2008 into early 2009, confidence in bank solvency evaporated across the system. Credit tightened. Asset prices fell. The shock spread globally, and bank failures became a recurring headline.

By late 2009, regulators were no longer watching from the sidelines. Old Second entered an informal memorandum of understanding that required it to hit steep capital targets: a Tier 1 leverage ratio of 8.75% and a total risk-based capital ratio of 11.25%. Even then, the bank’s leverage ratio was still short of what the OCC wanted.

Old Second needed capital—fast. Emergency equity raises diluted existing shareholders. And then came the lifeline that, for many banks, was also a public scarlet letter: TARP.

The federal government invested $73 million through the Troubled Asset Relief Program. That money helped keep Old Second alive. But the damage to the franchise was visible in what came next. When the Treasury later exited its position, it sold most of those shares at a steep discount—about 35 cents on the dollar. Taxpayers took a loss, and the market got a blunt signal: this bank had been hurt badly.

So what went wrong? A few forces combined into a near-fatal cocktail:

Concentration risk: Too much of the portfolio was tied to one asset class—commercial real estate and construction—in one region. When that local market froze, there was no diversification to soften the blow.

Underwriting erosion: As competition heated up, credit standards loosened. Loan-to-value ratios crept higher, terms got friendlier, and the old conservatism started to slip.

Growth-at-any-cost mentality: In the race to grow and compete with larger banks, risks that would have failed the test a decade earlier began to look acceptable.

Inadequate risk monitoring: The guardrails—concentration limits and internal controls that should have prevented the buildup—weren’t strong enough, or weren’t followed.

By the end of the decade, the question wasn’t about earnings or market share. It was existential: would Old Second survive—or become one more name on the long list of community banks that didn’t make it through the crisis?

VI. The Turnaround: From Crisis to Recovery (2010–2015)

The Second Critical Inflection Point

Bank turnarounds are some of the hardest transformations in business. A bank doesn’t sell a gadget or a subscription. It sells trust. And once that trust cracks, the customers you most want—sticky depositors and high-quality borrowers—are often the first to quietly move their money down the street. At the same time, regulators don’t hand you the space to experiment. After a near-miss, they tighten the box: more capital, more scrutiny, fewer options.

That’s the context for what came next at Old Second. After nearly losing the franchise, the bank had to do the unglamorous work of recovery—quarter after quarter, loan after loan, policy after policy.

Old Second’s turnaround under Jim Eccher became one of the more notable community bank recoveries of the post-crisis era.

Eccher wasn’t parachuted in from the outside. He had deep roots in the organization and the local market. He served as Senior Vice President and Branch Director from 1999 to 2003, and before that he was President and Chief Executive Officer of the Bank of Sugar Grove from 1996 to 1999. He joined the company in 1990 and was appointed CEO of Old Second National Bank 11 years ago. He also held the chief operating officer title at the holding company for the last seven years.

The playbook was straightforward. Executing it was not.

Painful honesty about problem assets: Instead of stretching out bad credits and hoping the market bailed them out, Old Second moved to recognize losses and clean up the portfolio. It meant taking write-downs that hurt in the short term—but it stopped the bleeding and made recovery possible.

Disposal of problem assets: Foreclosed properties—other real estate owned, or OREO—were sold off, even when it meant accepting steep discounts. Non-earning assets were a drag on capital and on management’s focus. The bank chose to clear them rather than cling to them.

Balance sheet shrinkage: Old Second got smaller before it got healthier. As problem loans were resolved and risk was reduced, total assets fell—but capital ratios and flexibility improved.

Cultural reset on credit: This was the real long-term fix. The credit committee was reworked. Underwriting standards tightened. Concentration limits were put in place and enforced. The goal wasn’t just to survive the last crisis; it was to prevent the next one from being fatal.

Rebuilding capital: The bank emphasized strengthening the foundation. Earnings were retained rather than paid out. The TARP investment was eventually resolved not through a simple repayment moment, but through the Treasury selling its shares to private investors in 2013.

Talent acquisition: The bank rebuilt its bench. Experienced bankers were brought in to replace those who had left or been let go, adding expertise and, in many cases, relationships that could help restart momentum once the bank was stable.

Even with those steps, the constraints were real. The OCC order required the roughly $2.1 billion-asset Old Second to obtain fresh appraisals on properties securing certain troubled real estate loans. And while credit quality improved, nonperforming assets stayed elevated for a while—an ongoing reminder that this wasn’t a quick reset. It was a long unwind.

From 2010 through 2014, the recovery looked less like a comeback montage and more like a grind. The focus was execution, not growth. Quarter by quarter, credit metrics improved. Non-performing loans came down. Criticized assets declined. Profitability moved from negative, to break-even, to modestly positive.

Over time, the relationship with regulators normalized. As capital strengthened and asset quality improved, the consent orders and memoranda of understanding that had constrained the bank were lifted.

By 2015, Old Second wasn’t just surviving anymore. It was preparing to compete again. The stock, which had traded in the low single digits at the depths of the crisis, recovered into the teens. Investors who stuck around for the slow, difficult work of the turnaround saw that patience pay off.

For investors, the Old Second story underscores a few hard-earned lessons: proof of changed behavior matters more than promises; balance sheet cleanup has to come before growth; culture doesn’t change in a quarter; and the banks that survive a crisis—if they truly learn from it—often come out tougher than the ones that never got tested.

VII. Strategic Reinvention: Growth Through Disruption (2015–2020)

The Third Critical Inflection Point

By 2015, Old Second had done the hard part: it survived, cleaned up the mess, and rebuilt credibility with regulators, customers, and investors.

Now it faced the question every turnaround eventually runs into: what do you do once you’re no longer in triage?

Jim Eccher and his team didn’t try to win by outspending the megabanks or out-acquiring the regionals. Instead, they leaned into a smarter idea: when the big institutions are distracted, the best community banks can steal the moment.

And the mid-2010s handed them plenty of distraction. Wells Fargo’s fake-accounts scandal blew up trust and triggered leadership upheaval. Big-bank mergers created internal chaos—new bosses, new credit boxes, new priorities—exactly the kind of disruption that causes good commercial bankers and their clients to start looking around. Post–Dodd-Frank compliance piled on process and committees, and for a lot of relationship bankers, that bureaucracy felt like a direct hit to the thing they were actually paid to do: serve customers.

Old Second saw opportunity in all of it. The strategy came together in a few deliberate moves:

Talent arbitrage through lift-outs: Old Second didn’t just recruit individuals; it recruited teams. A middle-market team doesn’t arrive empty-handed. It brings expertise, momentum, and—most importantly—relationships. For Old Second, that was a way to build capability and presence quickly. For the bankers, it was a chance to operate on a platform that promised fewer layers and more autonomy.

Old Second National Bank publicly highlighted these additions to its middle market Commercial Banking group. “We are genuinely excited to add Carl to the team,” said Alan Kohn, Senior Managing Director and head of Commercial Banking, “and to continue to build upon our existing group of talented bankers and expanding commercial capabilities.”

Geographic expansion through people, not branches: Instead of buying a bank every time it wanted to enter a new market, Old Second expanded by hiring lending teams with established books of business in places like Wisconsin and northwest Indiana. Compared to traditional M&A, it was simpler, cheaper, and easier to control from a risk standpoint—especially for a bank that had learned the hard way what uncontrolled growth could cost.

A safer mix of growth: Old Second intentionally shifted toward commercial and industrial (C&I) lending and away from the kind of CRE concentration that had nearly sunk it. At the same time, it built out treasury management, wealth management, and specialty lending—lines of business that deepened client relationships and added fee income, not just spread income.

Technology as a competitive equalizer: The bank invested in digital onboarding, online business banking, and mobile platforms so customers could get the convenience they expected—without sacrificing the high-touch relationship model. In practice, that meant a small business owner could start the process online, then sit down with a relationship manager in a branch to work through the complicated parts.

Strategic M&A returns: Old Second didn’t abandon acquisitions. It just became more selective about them. On April 20, 2018, it completed its acquisition of Greater Chicago Financial Corp. and its wholly owned subsidiary, ABC Bank.

As part of the deal, Greater Chicago Financial merged into Old Second Bancorp and ABC Bank merged into Old Second National Bank. Old Second—long viewed as a mostly suburban franchise—agreed to acquire the four-branch ABC Bank and its parent company for about $41.1 million. The acquisition added customers and helped expand lending in the city.

ABC Bank traced its roots back to 1891, when it was incorporated as Austin State Bank. Greater Chicago Financial acquired Austin Bank of Chicago in 1987 and later rebranded it. As of Sept. 30, the bank had $350.4 million in total assets, including $246.3 million in loans.

The ABC deal captured Old Second’s preferred style of M&A: bolt-on acquisitions that added scale and presence without overwhelming the organization. No giant, distracting integration. No “bet the bank” merger. Just a digestible step forward.

By this point, the geographic thesis was clear. Old Second would dominate the collar counties—Kane, Kendall, DuPage, Will—where it already had density and deep local knowledge, while building a selective foothold in Chicago itself. The idea wasn’t to be everywhere. It was to be important where it chose to compete.

By 2020, the shift was tangible. Old Second had moved from survival mode into growth mode. Assets grew from roughly $2 billion to more than $3 billion. Profitability stabilized. The stock recovered. And the bank entered the next decade not as a cautionary tale, but as a contender—one built to take advantage of disruption instead of being crushed by it.

VIII. Modern Era: Navigating COVID, Rate Cycles, and Fintech (2020–Present)

The 2020s opened with a stress test nobody asked for. Overnight, banking became remote, anxious, and intensely personal. Customers didn’t want a new app feature; they wanted answers. For Old Second, the pandemic became both a disruption and a proving ground—one that put its relationship model back in the spotlight.

PPP lending demonstrated relationship value: When the Paycheck Protection Program launched in April 2020, many small businesses discovered a hard truth: their “primary bank” might not actually be there when things got messy. Megabanks were swamped, their systems strained and their processes impersonal. Community banks, by contrast, did what they’ve always done—they picked up the phone, walked customers through paperwork, and helped keep payrolls alive.

Old Second leaned in. In its assessment area, 719 loans—about sixty-two percent—were PPP loans. And in 2020, when uncertainty was at its peak, PPP made up the majority of Old Second’s innovative loan program originations.

The PPP wave delivered a three-part payoff. First, fee income from origination. Second, customer acquisition—businesses that couldn’t get attention elsewhere started looking for a bank that would. And third, a stronger bond with existing customers who watched their community banker show up when it mattered.

And importantly, Old Second wasn’t forced into heroic lending to make that happen. It had minimal exposure to the industries hit hardest by COVID. Consumer lending exposure was modest compared to peers and the portfolio was well-seasoned. The crisis didn’t erase risk, but it validated the post-2008 credit culture the bank had rebuilt.

The 2020–2021 rate environment compressed margins: Then came the other pandemic-era reality for banks: rates pinned near zero. The spread between what a bank earns on loans and pays on deposits narrowed across the industry. At the same time, low rates fueled a refinancing boom, supporting mortgage banking income and giving banks another reason to stay close to their customers—helping them restructure debt and manage cash in a volatile economy.

2022–2023 brought relief—and new risks: As the Federal Reserve raised rates aggressively to combat inflation, margins expanded. Old Second, with a strong deposit franchise, benefited more than banks that relied heavily on wholesale funding.

Then came March 2023—the moment that jolted confidence in the entire banking system.

On March 10, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank was closed by the state banking authority, which appointed the FDIC as receiver. Stress had become visible days earlier when SVB disclosed a large loss on the sale of securities. A day later, the stock collapsed and uninsured depositors ran. In a matter of hours, tens of billions in deposits left, with even more queued up to leave next.

SVB wasn’t alone. In March 2023, four regional banks experienced depositor runs at record speed and failed. Three of the resulting failures—Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic—ranked among the largest in U.S. history.

For community banks like Old Second, the episode created both fear and opportunity. Fear, because any bank can face a run if confidence breaks. Opportunity, because the failures highlighted exactly what relationship-driven banks had been preaching for decades: a diversified deposit base matters, and concentration can kill.

As community banks and credit unions worked to distance themselves from the turmoil, the message was consistent: different customer bases, different risk profiles, and little to do with hot-money deposits or crypto exposure. “We have very little exposure to what happened at these regional banks. Clearly, there is a crisis of confidence in the market right now, but we don't want to attach ourselves to problems that we simply do not have. We're just a different animal.”

Old Second made it through for the same reason it had survived its own near-death experience years earlier—after the turnaround: diversified deposits, strong capital, and sticky funding built on long-term relationships rather than a narrow, volatile niche.

The transformational West Suburban acquisition: Even as the industry wrestled with COVID and then rate whiplash, Old Second kept executing on growth. The biggest move was West Suburban.

Old Second Bancorp and West Suburban Bancorp jointly announced a definitive merger agreement in a cash-and-stock transaction. Under the terms, West Suburban shareholders would receive 42.413 shares of Old Second common stock and $271.15 in cash for each share of West Suburban common stock. Using Old Second’s July 23, 2021 closing price of $11.76, the implied value was $769.93 per share, for an aggregate transaction value of about $297 million.

This one changed the shape of the company. Adding West Suburban nearly doubled Old Second’s size. Together, the combined banks had $6.2 billion in assets, $5.3 billion in deposits, and more than 70 branches—creating the 14th largest Chicago-area bank.

Old Second completed the merger effective December 1, 2021. That same day, West Suburban Bank merged into Old Second National Bank.

And this wasn’t a quiet bolt-on. The proxy materials describe a competitive process: a six-bank race to acquire the roughly $3 billion-asset West Suburban narrowed to two bidders—Wintrust and Old Second. On June 8, Old Second increased its offer to $330 million and Wintrust walked away. The deal was agreed to on July 25 and announced the following day.

The 2025 Bancorp Financial merger: More recently, Old Second announced a definitive merger agreement to acquire Bancorp Financial and its wholly owned bank subsidiary, Evergreen Bank Group, in another cash-and-stock transaction. Under the terms, Bancorp Financial stockholders would receive 2.5814 shares of Old Second common stock and $15.93 in cash for each share of Bancorp Financial common stock.

Old Second completed the merger effective July 1, 2025. On the same date, Evergreen Bank Group merged into Old Second National Bank. After closing, Old Second had, on a pro forma basis as of March 31, 2025, approximately $6.98 billion in assets, $5.95 billion in deposits, and $5.09 billion in loans, with 56 locations.

Current financial performance: Coming out of the 2023 volatility, Old Second delivered strong profitability. In the third quarter of 2023, it reported net income of $24.3 million, with ROAA of 1.67% and ROATCE of 22.80%. Management emphasized near-term focus on assessing risks in the loan portfolio, optimizing the earning asset mix, and reducing sensitivity to interest rates—while arguing that strong returns in a tight-spread environment reflected a higher-quality franchise built on a strong balance sheet and low-cost, granular funding.

By the third quarter of 2024, results were still robust: net income of $23 million, or $0.50 per diluted share, with return on assets of 1.63% and return on average tangible common equity of 17.14%. The company also announced a 20% increase in the common dividend, pointing to strong profitability and a well-capitalized balance sheet. Tangible equity strengthened as well, with the tangible equity ratio rising by 75 basis points to 10.14%.

IX. The Community Banking Business Model & Competitive Dynamics

To really understand Old Second’s strategic position, you have to understand what a community bank is selling—and what it’s constantly fighting against. The “product” isn’t just a checking account or a loan. It’s trust, delivered through a balance sheet. And the business model is simple enough to explain in a sentence, but hard enough to execute that thousands of banks have disappeared trying.

Revenue drivers: Most community banks live on two streams of revenue. The first is net interest income—the spread between what they earn on loans and investments and what they pay depositors. The second is fee income: wealth management, treasury services, mortgage origination, and a long list of smaller services that add up.

That spread gets summarized in one all-important metric: net interest margin, or NIM. For Old Second, NIM stayed strong at 4.64%, helped by higher rates on variable securities and loans. In community banking, anything north of 4% is typically a very good place to be.

The deposit franchise advantage: The real edge for a bank like Old Second starts with deposits—but not just “rate shoppers” chasing an extra few basis points. Relationship banking has long been viewed as an advantage in lending to small or newly formed businesses, especially the ones that don’t have pristine financial statements or a long credit history that fits neatly into standardized models.

That’s why community banks tend to hold a disproportionate share of smaller-balance commercial loans, including both commercial real estate and non-real-estate commercial and industrial credits. These are often relationship-driven deals, where the banker’s knowledge of the borrower matters as much as the spreadsheet.

The community bank challenge: Then comes the catch: scale. Banking has become a technology and compliance arms race, and those are two areas where size compounds. Core systems, mobile apps, cybersecurity, anti-money laundering controls, regulatory reporting, marketing—bigger institutions can spread those costs across a much larger base.

Banks of every size know they have to spend on tech. A 2018 Florida International University study found that median real technology spending per bank had doubled since 2000 for both small and large banks. But “spending” isn’t the same as “winning.” For similar proportional investment, the payoff from technology differed.

Research on mobile banking adoption suggests smaller community banks are often slower to roll out these tools—and the penalty can be real: lost deposits and reduced small business lending. Even for the banks that do manage to adopt digital platforms, digital banking can pressure profits in ways that are hard for smaller institutions to absorb.

Why community banks still exist: And yet, they persist—because they do something large institutions often can’t profitably do at scale.

Their biggest advantage is the relationship itself. A community bank’s tight connection to small business customers is not easy for a smartphone-based fintech app to replicate. That relationship-driven model also helps insulate banks like Old Second from fintech competition, especially when the relationship includes operating accounts, treasury services, and multiple products that make switching inconvenient.

Local knowledge is a real asset here. A community banker who has lived in Aurora for decades often knows which developers are steady and which ones are perpetually overextended. That kind of judgment is built through years of doing business in one place, across multiple cycles—and it’s not something you can fully replace with an algorithm.

Speed matters too. A small business owner who needs a fast answer on a line of credit increase might get a decision from Old Second in days, not the weeks—or months—that can come with megabank layers and committees.

That doesn’t mean fintech is the enemy. In many cases, fintech firms complement community banks well. Small businesses may value local relationships, but they don’t love slow applications, delayed credit decisions, or the lag between approval and funding. Those are exactly the frictions data-driven, smartphone-first platforms try to remove.

The technology question: So can community banks keep up? Increasingly, the answer is yes—but not by building everything themselves. Partnerships are becoming the path forward. Fintech-to-bank partnerships can bring everything from automated mortgage and auto loan origination to improved anti-money laundering transaction monitoring.

One caveat: a community bank’s ability to plug into these tools often depends on whether its core service provider is open to third-party integration. In modern banking, even innovation has its own gatekeepers.

X. Strategic Frameworks Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Competitive Rivalry (HIGH)

Old Second plays on one of the toughest fields in American banking. The Chicago metro area is packed with megabanks like JPMorgan Chase and BMO Harris, super-regionals like Wintrust and Old National, plus a long tail of community banks and credit unions—all chasing the same households and businesses.

Old Second’s answer has been consistent: don’t try to out-scale the giants. Out-serve them. The lift-out strategy and the West Suburban acquisition are two sides of the same bet—win customers through relationships and responsiveness, while building enough scale to keep up on technology and marketing.

2. Threat of New Entrants (MEDIUM-HIGH)

Starting a brand-new bank the old-fashioned way has been rare since 2008. The capital requirements are heavy, the regulatory process is slow, and the compliance burden is real.

But fintech doesn’t need a branch network to show up in your market. A software company can start competing for small business lending without ever applying for a bank charter.

Surveys back up how this pressure shows up differently by bank size. In the 2018 Survey of Community Banks by the Conference of State Bank Supervisors, small banks overwhelmingly said fintech firms weren’t their primary competitor—an outcome consistent with the FDIC’s 2018 Small Business Lending Survey. Large banks, by contrast, were far more likely to report fintech as a frequent competitor.

Old Second’s built-in defenses are the classic banking moats: insured deposits, regulatory experience, and long-standing customer relationships that a pure-play fintech can’t easily recreate.

3. Bargaining Power of Suppliers (MEDIUM)

In banking, “suppliers” are depositors—the people and businesses whose money funds the balance sheet.

The 2022–2023 rate hikes made something painfully clear across the industry: depositors have options. When money market funds offered yields around 5%, banks had to compete harder for funding, and customers became much more willing to move cash.

Old Second’s operating accounts and relationship-based deposits give it some protection. But no bank is completely insulated when rates rise and depositors start shopping.

4. Bargaining Power of Buyers (MEDIUM-HIGH)

On the other side of the balance sheet, borrowers—especially commercial borrowers—have leverage.

Large companies can tap the capital markets directly. Middle-market businesses can run a competitive process across multiple banks. Only the smallest businesses, with limited alternatives, are truly locked into a single lender.

Old Second targets the middle market—the segment where relationships still matter, but customers are sophisticated enough to demand competitive pricing and terms.

5. Threat of Substitutes (HIGH)

The list of substitutes for traditional bank products keeps getting longer: fintech lenders, private credit funds, credit unions, and even consumer options like buy-now-pay-later.

Research suggests fintech firms can reduce small banks’ small-business demand through a substitution effect. BigTech has also become a more meaningful credit provider to small and mid-sized businesses, though it has primarily served groups historically excluded from formal financial systems.

Old Second’s differentiation is breadth and depth: full-service banking, treasury management, and the “trusted advisor” role that a single-product lending platform can’t easily match.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE

After the Bancorp Financial merger, Old Second was approaching $7 billion in assets on a pro forma basis. That’s meaningful scale in community banking: compliance, technology, and marketing costs can be spread across a larger base than a smaller local bank can manage.

But it’s still a different universe from the super-regionals and megabanks, where scale advantages compound much faster.

2. Network Economies: WEAK

Banking doesn’t have the classic winner-take-all network effects you see in social media or major payment networks. One customer choosing Old Second doesn’t inherently make the bank more valuable to the next customer.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE-STRONG

This is the heart of Old Second’s edge. Big banks, structurally, are built for automation and standardization. That model makes it hard to profitably deliver high-touch, relationship-driven service to small businesses.

Community banks are built around local judgment and customization. And that’s not something a megabank can simply copy without breaking its own cost structure. The two models are designed to do different jobs.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG

Switching banks is easy in theory and painful in practice—especially for businesses. Operating accounts, credit lines, treasury management, payroll, merchant services, automatic payments: changing banks means changing routines, account numbers, vendor instructions, and often rebuilding trust with a new credit team.

Consumer banking switching costs are lower, but inertia is still a force—most people don’t move their primary bank unless something pushes them.

5. Branding: MODERATE

Old Second National Bank was named number one among “Best Banks in Illinois 2021,” marking the second straight year it was selected by customers. The award was based on a survey of over 25,000 U.S. customers rating banks on satisfaction, trust, terms and conditions, branch services, digital services, and financial advice.

The “Old Second” name itself signals stability and longevity—valuable traits in banking. But the brand is a regional asset, not a national one.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK-MODERATE

Old Second’s lift-out strategy helped it assemble experienced commercial bankers, and that talent matters.

But it’s not truly cornered. Good bankers can be recruited away, and relationships can move with them.

7. Process Power: MODERATE

One real advantage Old Second earned the hard way is process: the post-2008 rebuild of credit discipline and risk management. Underwrite prudently, move quickly, and don’t let growth overwhelm controls.

Competitors can improve their own processes over time, though, so this is an edge that requires constant maintenance.

Overall Assessment: Old Second’s advantage comes primarily from counter-positioning (relationship banking versus megabank automation) and switching costs (the stickiness of business banking relationships). Those are reinforced by moderate scale economies and a trusted regional brand. It’s a valuable franchise, but not an untouchable one—long-term success still comes down to execution: credit quality, relationship depth, and operational efficiency.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Considerations

Bull Case

Proven management: Jim Eccher and his team steered Old Second through its near-death period, did the hard work of a real turnaround, and then kept producing consistent results for more than a decade. In a business where trust is the product, continuity and credibility matter—and Old Second has had both.

Strong market position: The West Suburban and Bancorp Financial acquisitions reshaped the franchise, turning Old Second into a leading community bank across Chicago’s collar counties. Those are attractive markets—affluent, growing, and still very relationship-driven.

Economic moat: Relationship banking is not a marketing line; it’s a business model. Big banks can offer convenience and scale, but it’s difficult for them to profitably deliver high-touch service to small and mid-sized businesses. For many owners, the difference between a banker who knows the business and a call center script is the difference between getting a deal done and getting stuck.

M&A optionality: Old Second has two paths that can both create value. It can keep executing on smaller, bolt-on deals at reasonable valuations, or it can become the deal—an acquisition target for a larger regional that wants real share in Chicagoland.

Rate environment: A more normalized rate backdrop tends to reward banks with sticky, relationship-based deposits. The near-zero world of 2020–2021 squeezed spreads across the industry; today’s conditions are generally more supportive for a bank with a strong local funding base.

Fee income diversification: Wealth management, treasury services, and specialty lending reduce the bank’s dependence on rate spreads alone. That kind of mix matters when the next cycle inevitably turns.

Bear Case

Scale limitations: Even at roughly $7 billion in assets, Old Second is playing a different game than the $100 billion-plus institutions. The biggest banks can outspend on digital platforms, AI-driven tools, and marketing—and they can do it year after year.

Regulatory burden: Compliance is a fixed cost that doesn’t scale down neatly. New rules—whether CECL, shifting stress-testing expectations, or consumer protection requirements—can weigh more heavily on smaller banks that don’t have massive back-office leverage.

Geographic concentration: Old Second is still largely a Chicagoland story. That focus is a strength when the region is healthy, but it also creates single-market risk. A sharp regional downturn could hit harder than it would for more geographically diversified peers.

Economic sensitivity: Commercial banking is cyclical by nature. In a recession, credit losses typically rise at the same time loan demand slows—exactly the two-direction squeeze banks try to avoid.

Technology disruption: Fintech and BigTech can reduce the value of “soft information” by turning more borrower behavior into usable data. If alternative data and automated underwriting keep improving, that can erode part of the relationship-lending advantage smaller banks have historically relied on.

Talent retention: The lift-out strategy cuts both ways. The bankers Old Second recruited can be recruited again—especially if larger competitors decide they want those relationships and are willing to pay for them.

Historical risk: Old Second nearly didn’t make it through 2008–2009. The turnaround rebuilt discipline, but the question investors always have to keep asking is whether the lesson sticks when the next real estate boom makes risky growth look “safe” again.

Key Metrics to Watch

For investors tracking Old Second, three metrics deserve particular attention:

1. Credit Quality (NPLs, Criticized Assets): This is the one that matters most. Banks don’t usually die from bad strategy decks—they die from bad loans. Watch non-performing loans as a percentage of total loans, net charge-offs, and the direction of criticized and classified assets. Old Second’s asset quality improved meaningfully as substandard and criticized loans fell sharply from peak levels, but this is the category you monitor religiously.

2. Net Interest Margin (NIM): NIM is the engine: what the bank earns on assets versus what it pays for funding. Compression is often a warning sign; expansion can be a tailwind. Old Second’s NIM has been strong, but the trend matters more than the snapshot.

3. Deposit Costs and Mix: Deposits are the bank’s raw material. Pay attention to how much of the base is non-interest-bearing, what it costs to keep interest-bearing deposits, and whether customers are shifting into higher-rate products. Rising costs or a shrinking share of non-interest-bearing deposits can signal that competition is heating up.

XII. Lessons & Takeaways: What Old Second Teaches Us

Old Second’s story isn’t just a banking history lesson. It’s a case study in how institutions survive, almost fail, and then earn their way back—one hard decision at a time.

Survival matters: Coming back from the edge is rare in banking. Most troubled banks don’t get a second act; they either fail outright or get sold for a fraction of what they once were. Old Second lived through its crisis because it had external support (including TARP) and, just as importantly, because it was willing to change internally under Jim Eccher. You need both. Capital buys time, but only transformation buys a future.

Crisis reveals character: The 2008–2009 period exposed what had quietly built up during the boom: underwriting drift, concentration risk, and an appetite for growth that outpaced controls. The years that followed were the real test. The turnaround only mattered if the bank actually learned—and then behaved differently when the pressure eased. For investors, that’s the signal to look for in any turnaround: not just new faces, but new habits.

Relationship banking endures: Technology has changed how people bank, but it hasn’t eliminated why people bank. Small businesses still want a banker who answers the phone, understands the business, and can make a decision without sending them into a corporate maze. That’s why community banks still exist. In many situations, the competition isn’t about features—it’s about trust and responsiveness.

Strategic talent acquisition accelerates growth: Old Second’s lift-out strategy—bringing over entire teams, not just individuals—created a fast, practical form of expansion. Teams arrive with a way of working, an ability to execute, and a book of relationships. Done well, it’s a shortcut to building new capabilities without the cost and complexity of a full bank acquisition.

Conservative culture post-crisis is essential: Risk management isn’t exciting, but it is the job. The credit culture Old Second rebuilt after 2008 is what gave it resilience in later stress periods, including the 2023 regional bank turmoil. The lesson is simple: the time to tighten discipline is not in the middle of a crisis. It’s before the next one.

Industry consolidation creates opportunity: Big bank mergers don’t just move assets around—they disrupt relationships. Customers get reassigned. Credit boxes change. Decision-making slows down. And good relationship managers, frustrated by bureaucracy, start looking for a platform where they can actually serve clients. Old Second benefited from that disruption by recruiting talent from institutions like Wells Fargo, MB Financial, and others caught up in consolidation.

Long-term thinking wins: Old Second National Bank marked 150 years in 2021. That kind of longevity doesn’t come from winning every quarter; it comes from surviving cycles. The patience required to rebuild after 2008—cleaning up loans, re-earning trust, and choosing durability over fast growth—only makes sense if you’re optimizing for decades, not headlines.

Management continuity enables consistent execution: Eccher’s tenure—now more than a decade as CEO—helped Old Second avoid the strategy whiplash that can derail turnarounds. Consistency matters in banking because culture compounds. When leadership stays steady long enough to install discipline, enforce it, and prove it across cycles, the organization becomes more than a recovery story. It becomes a real franchise again.

XIII. Epilogue: Where Does Old Second Go From Here?

Old Second entered 2026 in a position of strength that would have been hard to imagine during the dark days of 2009. After the Evergreen deal, the company stood at roughly $7 billion in assets, with close to $6 billion in deposits and just over $5 billion in loans, spread across 56 locations in downtown Chicago and the west and south suburbs.

From here, the agenda is less about reinvention and more about execution. The priorities are clear: squeeze real efficiency out of recent acquisitions, keep investing in technology so the digital experience doesn’t fall behind, stay open to selective M&A that adds scale without breaking discipline, and grow fee income so results aren’t overly dependent on the rate cycle.

The $10 billion asset threshold question: At around $7 billion in assets, Old Second is creeping toward the $10 billion line that changes the regulatory game—bringing enhanced requirements like stress testing and the Durbin Amendment’s impact on debit interchange income. The choice is strategic: manage growth to stay under the threshold and avoid the added burden, or push through it and accept higher compliance costs in exchange for the benefits of greater scale.

Succession planning: With more than a decade of Jim Eccher’s leadership behind the turnaround and growth story, succession naturally becomes part of the forward-looking conversation. The lift-out approach has helped build bench strength, but investors will watch closely for signals about how leadership continuity is handled when the time comes.

Technology evolution: Banking is moving into an era shaped by AI and automation, from fraud detection to customer service to credit decisioning. Old Second’s competitiveness will hinge on how quickly it can adopt new capabilities—through its core provider, fintech partnerships, or internal buildout—without losing the relationship-driven model that differentiates it.

Market dynamics: The Chicago MSA, particularly the collar counties where Old Second is strongest, remains the bank’s home-field advantage. Continued growth and favorable demographics in those markets support the core strategy—if the bank keeps executing.

Competition ahead: None of this gets easier. Fintechs are maturing, large banks are getting more serious about small business offerings, and credit unions continue expanding. The competitive pressure won’t let up.

M&A scenarios: Old Second’s future could plausibly include both sides of the deal table. It can keep acquiring smaller community banks, but it could also remain attractive to a larger regional looking for meaningful share in Chicagoland. For investors, that optionality can cut both ways—potential upside, but also the possibility that the independent story ends early.

The arc from near-failure in 2009 to a nearly $7 billion franchise by 2025 stands out as one of the more remarkable community bank turnarounds of the post-crisis era. The next test is the one that gets every bank eventually: the next economic cycle, and whether the discipline that was rebuilt under pressure holds when growth looks easy again.

For an institution that survived the Panic of 1893, the Great Depression, and the 2008 financial crisis, the next chapter will be written from something it earned the hard way: resilience.

XIV. Resources & Further Reading

If you want to go deeper—into the filings, the crisis-era documents, and the data behind the narrative—these are the most useful starting points.

Essential Sources: - Old Second Bancorp Investor Relations (SEC filings, annual reports, earnings presentations) - FDIC Crisis and Response: An FDIC History, 2008-2013 — a clear, comprehensive account of how the last banking crisis unfolded and how regulators responded - Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Research — essential context on the Chicago-region economy and local banking dynamics - Conference of State Bank Supervisors annual surveys — great for understanding how community banks are evolving, especially around technology and competition - KBRA and other rating agency reports on Old Second’s credit ratings

Key Metrics to Monitor: 1. Credit quality trends (NPLs, charge-offs, criticized assets) 2. Net interest margin evolution 3. Deposit cost and composition changes

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music