Oklo: The Story of Nuclear's Startup Revolution

I. Introduction: When Silicon Valley Meets the Atom

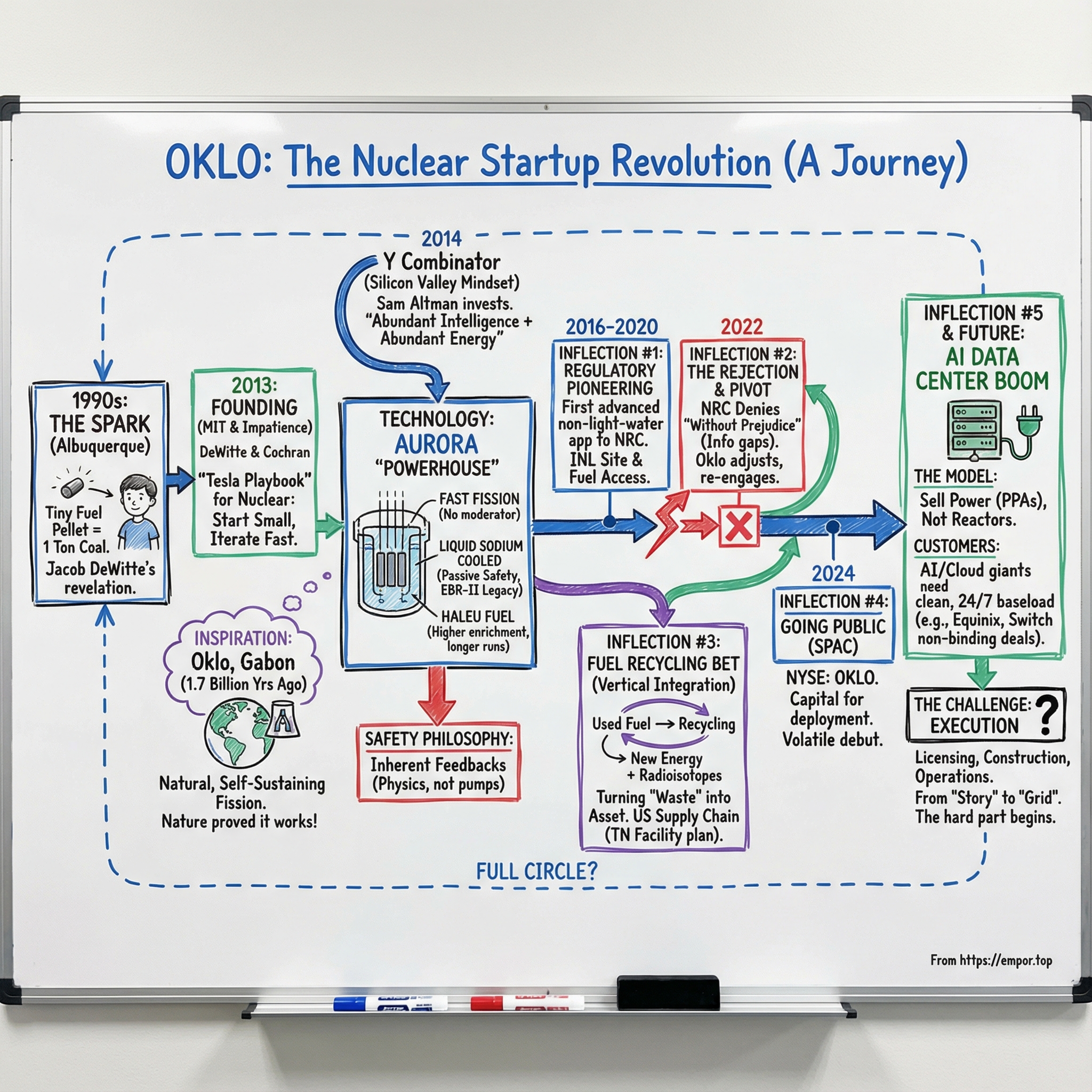

Picture a Saturday morning in Albuquerque, New Mexico, sometime in the early 1990s. A young boy and his father make their weekly ritual: donuts first, then the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History. The boy isn’t drawn to the flashy stuff. His favorite exhibit is a simulated nuclear fuel pellet—smaller than a pencil eraser. The placard explains what sounds like a magic trick: that tiny cylinder holds roughly the same energy as a ton of coal, or about 149 gallons of oil. For him, it’s less trivia and more revelation.

That boy is Jacob DeWitte. Decades later, he’s the CEO of Oklo Inc.—a company making one of the most audacious bets in modern nuclear. Oklo is a Santa Clara, California-based designer of small modular reactors, founded in 2013 by DeWitte and fellow nuclear engineer Caroline Cochran. But calling it “an SMR company” is like calling SpaceX “a rocket manufacturer.” Technically true. Totally incomplete.

Oklo is building fast fission power plants aimed at delivering clean, reliable electricity; pushing a domestic supply chain for critical radioisotopes; and advancing nuclear fuel recycling—turning what most people think of as “waste” back into usable energy.

Even the name is a thesis statement. In 1972, French scientists studying uranium from mines in Gabon noticed something impossible on paper: the uranium-235 content was lower than it should have been, as if it had already been burned in a reactor. The conclusion was wild and undeniable. About 1.7 billion years ago, nature ran its own self-sustaining fission reactions in the Oklo region—effectively, a natural nuclear reactor that operated for a long time without catastrophe. Oklo the company is borrowing that credibility: fission isn’t some new, fragile human experiment. It’s something the Earth has already proven can work.

And Oklo arrives at exactly the right moment. AI is driving a power demand curve that looks less like a slope and more like a wall. The climate clock is still ticking. And after decades of stagnation, the U.S. regulatory and political environment is finally showing signs of making room for nuclear innovation again.

Oklo’s stock has had its share of drama, but the price chart isn’t the story. The story is what it took for two MIT-trained engineers to bring startup speed—and startup ambition—into the most safety-critical, tightly regulated industry in the world.

This is how Oklo set out to convince Silicon Valley that the future of AI runs on nuclear power—and what their journey says about where energy is headed next.

II. The Natural Reactor: Origin of the Name & Nuclear Context

To understand what Oklo is trying to do—and why anyone should take the bet seriously—you have to start with the strange, almost poetic fact that Earth got there first. Nature ran nuclear reactors long before humans had the vocabulary for “fission,” “criticality,” or “containment.”

In 1972, French nuclear physicist Francis Perrin was studying uranium from the Oklo mines in Gabon when he spotted a tiny anomaly with huge implications. The uranium-235 concentration was a hair lower than it should have been: 0.717% instead of the typical 0.720%. That difference isn’t “interesting.” In Perrin’s world, it’s evidence. Uranium-235 doesn’t just vanish. It gets used.

The conclusion was astonishing: about 1.7 billion years ago, those ore deposits were rich enough—and groundwater was present in just the right way—to sustain self-starting chain reactions. A natural nuclear reactor had operated there, on and off, for hundreds of thousands of years, generating roughly 100 kilowatts of thermal power.

The bigger point wasn’t the wattage. It was the durability. The Oklo site showed something modern nuclear debates often miss: fission can be stable and self-regulating over geological time. Many of the reaction products stayed largely where they formed. The planet didn’t just “survive” fission—it managed it.

Oklo the company borrows that story on purpose. The name is a reminder that nuclear isn’t inherently a brittle, high-wire act. Under the right physics, it can be boringly stable—and boring is exactly what you want from your power source.

The Rise and Fall of American Nuclear

America’s relationship with nuclear energy has swung between utopian optimism and near-paralysis.

The 1950s and 60s were the Atoms for Peace years: a national push that imagined nuclear-powered prosperity everywhere. The commercial fleet ramped quickly, eventually peaking at 112 operating reactors.

Then the public narrative turned—hard.

Three Mile Island in 1979 released negligible radiation, but it permanently rewired public perception. Chernobyl in 1986 became the global nightmare scenario: catastrophic failure magnified by flawed design and institutional breakdown. Fukushima in 2011 delivered the modern version of the same lesson—this time in a technologically sophisticated country—showing how natural disasters could still overwhelm backup systems.

By 2020, the U.S. construction pipeline had largely frozen. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission had become exceptionally good at regulating an aging fleet, and far less practiced at shepherding genuinely new designs to the finish line. And the industry’s most recent marquee build-out—Vogtle Units 3 and 4 in Georgia—became a cautionary tale: more than a decade of construction and billions over the original budget.

So when Oklo shows up talking about new reactors, it’s not entering a neutral market. It’s entering one shaped by trauma, cost overruns, and regulatory muscle memory.

The EBR-II Legacy

And yet, beneath the stagnation, there’s another thread in American nuclear history—one that Oklo is explicitly trying to pick up.

Experimental Breeder Reactor-II, or EBR-II, was a sodium-cooled fast reactor designed, built, and operated by Argonne National Laboratory at what’s now Idaho National Laboratory. It ran from the 1960s until 1994, generating a trove of real-world data on fast reactors, fuels, and materials. That knowledge didn’t disappear when the plant shut down. It became the reference library for the next generation.

EBR-II’s most famous moment came in 1986, in a demonstration that reads like science fiction if you’re used to the “nuclear is fragile” storyline. In April of that year, engineers ran two tests with the reactor at full power—62.5 megawatts thermal—and then shut off the primary cooling pumps. Crucially, they didn’t allow the normal shutdown systems to step in. They simply watched what the reactor would do.

Within about 300 seconds, the power dropped to near zero. The fuel and reactor weren’t damaged.

It didn’t work because someone saved the day. It worked because of physics. As the system heated up, the fuel and structures expanded, which reduced reactivity and choked off the reaction. The reactor stabilized itself.

For Jacob DeWitte and Caroline Cochran, this wasn’t just a legendary story from the old guard. It was the technical spine of a new kind of nuclear company: one that would lean on inherent feedbacks and proven fast-reactor behavior, then try to wrap it in a startup’s speed and a modern commercial model.

The hard part, in other words, wasn’t whether the underlying physics could behave. EBR-II had answered that decades earlier. The hard part was everything else: regulation, financing, siting, customer demand—and convincing a skeptical world that nuclear could be rebuilt without repeating the last generation’s mistakes.

III. Founding & Early Years: MIT to Y Combinator (2013–2015)

The MIT Genesis

By the time Jacob DeWitte arrived at MIT in 2008, he was already deep in the weeds of advanced reactor engineering. He spent his master’s work studying next-generation designs, then turned to a very different problem for his PhD: how to squeeze more life and more output out of the massive reactor fleet already operating around the world.

He also wasn’t coming at this as a purely academic exercise. Before Oklo, DeWitte had built experience across the nuclear ecosystem, with roles at GE, Sandia National Laboratories, Urenco USA, and naval reactor research laboratories. He’d worked across multiple reactor types—sodium fast reactors, molten salt reactors, and next-generation pressurized water reactors. At GE, he led core design work on the PRISM sodium fast reactor. At Sandia, he contributed to irradiation facility development.

But the more time he spent around “big nuclear,” the more he couldn’t shake a nagging conclusion: the technology wasn’t the only thing holding the industry back. The way nuclear was commercialized—huge projects, huge checks, decade-plus schedules—made it almost impossible to move fast, learn quickly, or build momentum.

So while he was still a PhD student, DeWitte began thinking about what an advanced nuclear company could look like if it were built like a startup. In 2013, he partnered with someone who’d been thinking along the same lines: Caroline Cochran.

They’d met at MIT in the nuclear engineering world, but Cochran brought a different set of lenses to the problem. She had an S.M. in Nuclear Engineering from MIT, plus a B.A. in Economics and a B.S. in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Oklahoma. She was also one of the youngest recipients of the University of Oklahoma Regent’s Alumni Award. In other words: fluent in the technical details, but equally comfortable thinking in terms of markets, incentives, and how a product actually gets adopted.

Together, DeWitte (CEO) and Cochran (COO) founded Oklo in 2013—before DeWitte had even finished his PhD. Cochran had completed her MIT master’s in 2010. What bound them together wasn’t just shared training. It was shared impatience.

“Newness was favorable because it shed some of the legacy inertia around how things have been done in the past, and I thought that was an important way of modernizing the commercial approach,” DeWitte has said.

The Tesla Playbook

From day one, Oklo’s pitch wasn’t “we have a better reactor.” It was “we have a better way to build a nuclear business.”

DeWitte drew inspiration from an unlikely place: Tesla. “The idea was if we take this technology, we start small and use an iterative approach to tech development and a product focused approach, kind of like what Tesla did with the Roadster [electric car model] before moving to others,” he said. “That seemed to yield an interesting way of getting some initial validation points and could be done at a higher cost efficiency, so less cash needed, and that could incrementally fit with the venture capital financing model.”

In nuclear, that mindset was borderline heretical. The default playbook was to go big, go slow, and rely on enormous institutional backing. Oklo wanted to go smaller, learn faster, and fund the journey with venture-style rounds—building credibility step by step instead of trying to win the entire war upfront.

Y Combinator (Summer 2014)

Which is how a nuclear reactor company ended up at Y Combinator.

By 2014, DeWitte and Cochran applied to the accelerator that had become synonymous with software and consumer startups. YC hadn’t exactly been a home for energy projects, let alone fission. But Oklo was accepted into the Summer 2014 batch.

DeWitte went in curious—partly because no one at YC was going to help them calculate neutron flux or design a core. And that wasn’t the value anyway. YC was useful where nuclear startups are usually weakest: narrative, strategy, focus, and how to build a company around an idea that sounds impossible.

It also exposed a stark cultural difference. Back on the East Coast, conversations about nuclear often started with suspicion: Is it safe? Out in Silicon Valley, the instinct was different. People leaned forward. The question wasn’t “should this exist?” It was “how do you make it real?”

Sam Altman’s Entry

Sam Altman met DeWitte and Cochran in 2013. He pulled Oklo into Y Combinator in 2014, then invested in 2015 and became chairman.

Altman’s interest wasn’t a random side quest. He’d framed the future as a function of two inputs: “I think the two most important inputs to a great future are abundant intelligence and abundant energy.” Oklo was, in a very literal sense, an attempt to make the second input scale.

Capital followed. Oklo attracted venture backing from a roster that didn’t look like the traditional nuclear world: Hydrazine Capital (founded by Altman, with Peter Thiel as its sole limited partner), Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz, Ron Conway of SV Angel, Kevin Efrusy of Accel, and Tim Draper of Draper Associates. The company raised small early rounds in 2013 and 2014 while going through accelerators including MassChallenge and Y Combinator.

To anyone watching, the obvious question hung in the air: could a company built on seed rounds and startup tempo really take on the most regulated industrial category in America?

Oklo didn’t have the answer yet. But it was about to find out—by walking straight into the Nuclear Regulatory Commission with a first-of-its-kind application.

IV. The Aurora Design: Technology Deep Dive

The Core Innovation

Oklo’s bet centers on its Aurora “powerhouse”—a name chosen on purpose. This isn’t meant to conjure images of concrete domes and skyline-sized cooling towers. It’s meant to feel like a product: compact, repeatable, and designed to be deployed.

The key technical shift starts inside the reactor core. Most conventional reactors use water not just for cooling, but also as a moderator—something that slows neutrons down before they trigger the next fission event. Aurora doesn’t use a moderator. By letting neutrons stay fast, the reactor can be much more compact.

That “fast” label often trips people up. It’s not a promise about construction speed. It’s about neutron speed.

In Oklo’s design, a sodium-cooled fast-neutron reactor produces heat, which is transported out of the core and into a supercritical carbon dioxide power conversion system that generates electricity. The Aurora-INL concept is a 50–75 MWe sodium-cooled fast reactor that draws directly from the design and operating heritage of the Experimental Breeder Reactor II (EBR-II), which ran at the same Idaho site from 1964 to 1994.

The product offering has also changed as Oklo’s ambitions expanded. Early on, the company talked about a roughly 1.5 MWe microreactor. As the design matured and the customer set shifted, the target grew—first to tens of megawatts, and more recently to a broader range that reaches up to about 100 MWe.

Liquid Sodium Cooling

Aurora’s most distinctive feature is its coolant: liquid sodium instead of water. Sodium lets the reactor operate at higher temperatures without the same pressure-driven plumbing and sprawling infrastructure you associate with today’s large light-water plants. In the Aurora-INL concept, that sodium-cooled fast reactor would use metal fuel derived from legacy EBR-II material.

The bigger implication is safety philosophy. Sodium cooling supports what the industry calls passive safety—where the system’s response to problems is driven by physics, not by motors, valves, or perfect human decisions under stress. In a pool-type configuration like the one Oklo draws from, heat moves efficiently from the fuel into the coolant. If temperatures rise in off-normal conditions, thermal expansion in the coolant, fuel, and structures naturally reduces reactivity and brings power down—echoing the core lesson of EBR-II’s famous tests: the reactor wants to shut itself down.

The HALEU Fuel Advantage

Fast reactors also change the fuel equation. Aurora is designed to run on HALEU—high-assay low-enriched uranium—meaning uranium enriched to above 5% and below 20% uranium-235. That’s materially higher than the fuel used across the current U.S. reactor fleet, which is enriched to under 5%.

The payoff is endurance. With more uranium-235 available to sustain the chain reaction, a reactor like Aurora can run longer between refueling intervals—one of the traits that makes the whole “powerhouse” idea plausible.

Oklo’s early fuel story is also unusually concrete for an advanced reactor startup. Its initial supply is tied to Idaho National Laboratory and, remarkably, to EBR-II itself. Oklo has been granted access to 5 metric tons of HALEU as part of a cooperative agreement with INL that was competitively awarded in 2019. The plan is for that HALEU to be recovered from used fuel from the Department of Energy’s EBR-II, closing a loop that most nuclear projects only talk about in theory.

Safety Features

Aurora’s safety philosophy is a deliberate break from the traditional nuclear approach: fewer active systems, less reliance on operator intervention, more dependence on inherent feedbacks.

“Aurora’s inherent safety allows us to use proven, commercially available power systems like Siemens Energy’s turbine technology. That design philosophy shortens timelines, lowers costs, and turns advanced nuclear into a deployable product.”

Of course, none of this matters if the technology can’t win regulatory acceptance and reach real-world deployment. That question started to get its first serious test in 2016, when Oklo made a move no advanced fission startup had made before: it went straight to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

V. Inflection Point #1: First-Mover on NRC Licensing (2016–2020)

The Regulatory Pioneering

In 2016, the Department of Energy did something rare for a government agency: it tried to get ahead of the problem. It began an industry-led effort to create new approval processes for advanced reactor applications—because the existing ones weren’t built for what Oklo, and others like it, were proposing.

Two years later, Oklo became one of the first real test cases for that new structure.

That mattered because the NRC wasn’t just reviewing a different reactor. It was being asked to apply a framework built for massive, water-cooled light‑water reactors to something fundamentally different: a compact fast reactor, with different operating assumptions and a different fuel story.

There were no templates. No comfortable precedents. No “just fill out the same form Westinghouse used.”

Oklo had to build the path while walking it. “We had to look at regulations with a fresh eye and not through the distortion of everything that had been done in the past,” DeWitte said.

And in a business where permitting is often the true critical path, being first isn’t a bragging right. It’s a risk. If you get it right, you don’t just win a license—you help define how the entire category will be judged.

Idaho National Laboratory

Oklo also needed more than regulatory progress. It needed a real place to deploy—and real fuel to run.

That’s where the Department of Energy’s Idaho National Laboratory came in. INL announced it would provide Oklo access to recovered fuel material to support the development and demonstration of Aurora. Oklo applied through a competitive process INL launched in 2019, and selection notifications went out that December.

In 2019, Oklo received two things that startups almost never get in nuclear: a site-use permit at INL and access to fuel recovered from the historic Experimental Breeder Reactor-II.

This wasn’t just helpful. It was a federal signal flare. The DOE was effectively saying: we’re willing to back this with the two assets that matter most—where you can build, and what you can fuel it with.

The Application

With a site and a fuel pathway coming into focus, Oklo took the biggest step.

In March 2020, it submitted a combined license application to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission for an advanced reactor to be built at the Idaho National Laboratory site. In June, the NRC accepted the application for review—using a novel two-step approach to docketing that let Oklo address identified information gaps before a full review schedule was set.

It was the first combined construction-and-operation license application for an advanced fission technology that the U.S. regulator had accepted for review in more than a decade.

For the broader nuclear industry, the implications were obvious. If Oklo could make it through, it wouldn’t just mean one company had a shot at deployment. It would mean the licensing system could, in fact, bend toward the next generation of reactors.

The open question was whether that bend would hold—or snap back.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The NRC Rejection & Pivot (2022)

The Shock

In early 2022, the story Oklo had been trying to write—first-of-a-kind advanced reactor, first-of-a-kind licensing path—hit an abrupt wall.

Federal regulators denied Oklo’s application to build and operate its Aurora reactor at Idaho National Laboratory. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission said it didn’t have enough information to keep going, particularly around how Aurora would behave in accidents and how Oklo was defining the safety features meant to address them.

The language mattered: the NRC denied the application “without prejudice.” In plain English, that meant this wasn’t a final thumbs-down on Aurora. It was the agency saying, “Come back when the package is complete.”

Inside Oklo, though, it didn’t feel procedural. It felt like a blindsiding. Caroline Cochran told CNBC they had no warning it was coming: “It was pretty much as much of a surprise to us as anyone else. We weren’t given any heads up at all before it basically went public yesterday. We really didn’t have any indication that this was coming.”

For a company that had spent years doing the hard thing—being the first startup to push an advanced reactor application through a system built for the last generation—this was the nightmare scenario: not a long review, but a stop sign.

The Reason

The NRC’s explanation was specific and direct. NRC Director Andrea Veil said Oklo’s application still had “significant information gaps” in its description of potential accidents and in how it classified its safety systems and components. Those gaps, the NRC said, prevented the staff from moving forward with further review.

More concretely: the NRC pointed to unresolved issues around Aurora’s “maximum credible accident,” the safety classification of key structures, systems, and components, and other topics the staff said it needed in order to establish a schedule and complete a technical review. The agency’s view was that, over the course of the process, Oklo had not provided substantive answers to certain requests for additional information.

Critics piled on. Edwin Lyman at the Union of Concerned Scientists argued that Oklo wasn’t giving the regulator the basics it needed to do its job, and claimed the company was effectively asking to be treated differently because it believed the reactor’s small size and design made it inherently safe.

Oklo’s supporters read the same facts through a different lens: this was what happens when a first-of-a-kind design meets a first-of-a-kind process. You don’t get rejected because the physics are wrong. You get rejected because the paperwork has to map cleanly onto a regulatory machine that was never designed for your kind of reactor.

The Response and Lessons

Oklo didn’t walk away. It adjusted.

Rather than treating the denial as the end of the road, Oklo moved to re-engage the NRC with a more structured plan. The company submitted a Licensing Project Plan outlining how it wanted to work with the agency to support future licensing activities.

The deeper lesson was one nuclear founders eventually learn the hard way: in this industry, there are no shortcuts. The standards are demanding for a reason—partly safety, partly institutional muscle memory—and you don’t win by insisting the rules don’t apply. You win by translating a new technology into terms the system can evaluate.

That’s also why the words “without prejudice” mattered so much. For investors and partners, this was a major setback—but not a death sentence. The denial wasn’t a judgment on Aurora’s safety, security, or merits. It was a judgment on completeness.

Oklo could come back. The real question was whether it could absorb the hit, do the unglamorous work, and return with an application strong enough to survive the most unforgiving gatekeeper in American industry.

VII. Inflection Point #3: The Fuel Recycling Bet (2021–2024)

Vertical Integration Strategy

While Oklo was wrestling with the NRC, it was also quietly placing a second, equally consequential bet: fuel.

Most nuclear startups talk about reactors as the product. Oklo kept circling a tougher constraint—the thing that can bottleneck deployment no matter how elegant your design is. Where does the fuel come from, and how do you control that supply chain?

For Oklo, fuel recycling wasn’t a science project. It was a strategic moat. A way to turn a national political problem—used nuclear fuel—into an asset the company could build on.

“Fuel recycling can impact how quickly we decarbonize. Since used fuel is about 95% recyclable, you can transform waste into a viable resource,” Jacob DeWitte said. “There is enough energy content in today’s used fuel to power the entire country’s power needs for over 100 years without carbon emissions.”

It’s a provocative claim, but the point is simple: if you can extract more value from what’s already been mined and used, you don’t just shrink the waste problem. You unlock a new fuel source—and you do it with material that’s already sitting here.

DOE Awards

The U.S. government noticed.

Oklo won a series of competitive Department of Energy cost-share awards aimed at turning recycling from concept into commercial reality. One of the headline wins was a $5 million project with Argonne National Laboratory, Idaho National Laboratory, and Deep Isolation, funded through ARPA‑E’s ONWARDS program—designed to rethink how nuclear waste and advanced reactor disposal systems work in practice.

Across four DOE cost-share projects, Oklo said it had been selected for more than $15 million in support to commercialize advanced reactor fuel made from used nuclear fuel. The theme across those awards was consistent: build the technical pathway, prove it can scale, and do it in a way that works inside the U.S. regulatory system.

The Tennessee Facility

By 2025, that strategy had moved from R&D and awards to something much bigger—and much more public.

In September 2025, Oklo announced plans to design, build, and operate a fuel recycling facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, as the first phase of an advanced fuel center. The company said it was targeting investment of up to about $1.7 billion and aiming to create more than 800 jobs.

The facility is planned for a 247-acre site at the Oak Ridge Heritage Center, and Oklo described it as the first privately funded nuclear fuel recycling center in the U.S.—built to turn used nuclear fuel into a domestic supply for advanced reactors.

“Fuel is the most important factor in bringing advanced nuclear energy to market,” DeWitte said. “By recycling used fuel at scale, we are turning waste into gigawatts, reducing costs, and establishing a secure U.S. supply chain that will support the deployment of clean, reliable, and affordable power.”

Zoom out, and you can see why Oklo is leaning in. The U.S. has stored more than 94,000 metric tons of used nuclear fuel at power plant sites around the country. Oklo argues that the energy still sitting in that material is enormous—on the order of about 1.3 trillion barrels of oil in equivalent energy, roughly five times Saudi Arabia’s reserves.

For Oklo, recycling isn’t just about cleaning up the past. It’s a competitive edge that’s hard to copy: it reduces exposure to fuel supply constraints, creates another potential line of business, and fits neatly with a national interest in doing something—anything—more productive with nuclear “waste” than parking it indefinitely.

VIII. Inflection Point #4: Going Public via SPAC (2023–2024)

The SPAC Announcement

Oklo’s next big inflection point wasn’t technical. It was financial.

In July 2023, Sam Altman announced the deal structure that would take Oklo public: a merger with AltC Acquisition Corp., the special-purpose acquisition company he’d helped create. The pitch was straightforward and ambitious. This wasn’t just a liquidity event. It was a way for AltC’s shareholders to become owners in Oklo—and, in doing so, help fund the first deployment of the Aurora powerhouse.

By May 2024, the merger closed and Oklo began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker OKLO. The deal left the company with more than $300 million in gross proceeds to fund its next stage of development.

The SPAC route, though, came with baggage. By then, SPACs had earned a reputation for hype and disappointment, with many post‑merger companies trading far below their splashy headline valuations. Oklo argued it wasn’t another “story stock.” It had a defined technology roadmap, deepening government relationships, and a market that was suddenly re-learning what “clean baseload” meant.

The Rocky Debut

Wall Street didn’t exactly greet that narrative with calm.

Oklo’s first day of trading was choppy, with volatility halts in the first hour. The whiplash wasn’t just about the company—it was about what investors were being asked to underwrite: a richly valued, pre‑revenue nuclear startup that hadn’t yet put a commercial reactor in the ground.

In other words, it looked like a public-market version of what Oklo had always been: a big bet on a future that still needed to be built.

Why SPAC Made Sense

For Oklo, the SPAC structure solved a set of very Oklo problems.

It brought in substantial capital without the traditional IPO gauntlet. It allowed the company to share forward-looking plans and projections that a conventional offering wouldn’t typically accommodate. And it tightened the company’s association with Altman—an advantage that mattered as Oklo increasingly positioned itself around a new customer class: the AI ecosystem and the data centers that power it.

The merger valued Oklo at $850 million, with the deal structure also pointing to a larger capital pool—up to about $500 million—to accelerate development and support the path to deployment.

IX. Inflection Point #5: The AI Data Center Boom (2024–2025)

The AI Energy Crisis

By 2024, Oklo didn’t have to work as hard to explain why the world might suddenly want new nuclear. The customers were starting to do the explaining for them.

Artificial intelligence had gone from a buzzword to an industrial buildout. Training and running models at scale takes a shocking amount of electricity, and the companies building the AI future—Microsoft, Google, Amazon—ran into a constraint they couldn’t code their way around: power.

As data center developers hunted for reliable, carbon-free electricity, nuclear came back into the conversation in a new way. Not as a decades-long public works project, but as a clean, always-on energy source that could actually match the shape of the demand. Amazon and Alphabet underlined that shift in October when they announced investments in small nuclear reactor technology.

The headline numbers were arresting, but the real issue was simpler: AI loads don’t politely follow the sun or the wind. They want steady power, around the clock. That happens to be nuclear’s home turf.

Oklo's Positioning

Oklo leaned into that moment with a message that sounded bold in public, but pragmatic in context. “Advanced nuclear is going to be standard for data centers in the future,” said Brian Gitt, Oklo’s head of business development.

More importantly, Oklo started putting real commercial markers down.

In its S‑4 filing with the SEC, Oklo disclosed a deal-in-motion with Equinix, the data center colocation giant. After signing a letter of intent in February, Equinix made a $25 million prepayment to Oklo tied to future power supply.

The LOI contemplated Equinix buying power from Oklo’s planned “powerhouses” to serve U.S. data centers over a 20‑year timeline, with the right to renew and extend power purchase agreements for additional 20‑year terms. It wasn’t a finished, fully built project yet—but it was the kind of structure nuclear has always needed: long-duration demand from a creditworthy customer.

The Switch Deal

Then came the agreement designed to grab everyone’s attention.

In December 2024, Oklo announced what it called “one of the largest corporate clean power agreements ever signed”: a 12‑gigawatt, non-binding Master Power Agreement with Switch, a provider of AI, cloud, and enterprise data centers.

The framework, announced Dec. 18, laid out an ambition to deploy Oklo Aurora powerhouse projects across the U.S. through 2044, with Oklo developing, building, and operating the plants under a series of power purchase agreements. The key words were “non-binding,” and Oklo was explicit about that. The idea was that individual binding agreements would be finalized as milestones were reached.

Still, even as a framework, it signaled something important: data center operators weren’t just shopping for a cleaner grid. They were trying to secure new generation capacity that could be built for them.

Sam Altman Steps Down

In April 2025, Oklo made a governance move that telegraphed how serious these conversations were becoming.

Sam Altman stepped down as Oklo’s chair to avoid a conflict of interest ahead of talks between OpenAI and Oklo on a potential energy supply agreement.

“As Oklo explores strategic partnerships to deploy clean energy at scale, particularly to enable the deployment of AI, I believe now is the right time for me to step down,” Altman said.

Jacob DeWitte, Oklo’s CEO and cofounder, took over as chair while remaining on the board. The practical effect was straightforward: it cleared Oklo to pursue deals across the AI landscape—including, potentially, with OpenAI—without a governance overhang.

Stock Performance

Public markets, predictably, tried to price all of this in real time—and did it messily.

Oklo’s shares swung hard. Over the past year, the stock posted enormous gains, then gave back a meaningful chunk in a sharp pullback that erased billions in market value from peak levels.

That volatility captured the core tension in the Oklo story at this stage. The opportunity looked gigantic, and the customer pull was suddenly real. But the company still had to do the thing nuclear companies are ultimately judged on: execute—through licensing, deployment, and operating proof that the “powerhouse” model can leave the slide deck and enter the grid.

X. The Business Model: Selling Power, Not Reactors

The PPA Model

Oklo’s biggest break from traditional nuclear isn’t a materials breakthrough or a new coolant. It’s how the company wants to get paid.

Instead of selling reactor designs to utilities—or licensing technology and walking away—Oklo plans to build, own, and operate its Aurora plants itself, then sell electricity to customers through long-term power purchase agreements.

That matters because it flips the burden of nuclear complexity. The customer isn’t signing up to become a nuclear operator. They’re buying what they actually want: reliable power, on a contract, at a predictable price.

It’s the same logic behind Oklo’s headline “master agreement” with Switch. The point wasn’t just the scale. It was the structure: a direct path for large customers to secure clean, around-the-clock power without needing to build a power plant company along the way.

Oklo says Aurora will be a smaller, simpler plant, with designs that it expects to range from 75 megawatts up to 100 megawatts or more. Oklo intends to develop the sites, run the facilities, and deliver electricity under long-term contracts.

The advantages are straightforward if Oklo can execute:

- Recurring revenue: long-term PPAs can create stable cash flow once the plants are online

- Customer simplicity: customers get power without taking on nuclear licensing or operational risk

- Asset ownership: Oklo keeps ownership of long-lived infrastructure

- Learning curve: running more plants should let Oklo iterate and improve over time

Vertical Integration

Oklo is also trying to widen the business beyond electrons.

The company signed a letter of intent to acquire Atomic Alchemy Inc., a U.S.-based radioisotope producer. Oklo’s pitch is that its fast reactor and fuel recycling technologies can produce valuable coproducts, including radioisotopes—materials used across medicine and industry.

Oklo proposed acquiring Atomic Alchemy for $25 million in an all-stock transaction.

If the deal closes, Oklo expects radioisotopes to become an earlier revenue source than power generation, with initial revenues anticipated before it completes its first radioisotope production reactors. The strategic appeal is obvious: it diversifies the company’s income while it works through the long, sequential path to first reactor deployment.

There’s also a supply-chain argument. The British Institute of Radiology has highlighted that demand for radioisotopes continues to rise while supply struggles to keep pace, constrained by aging reactor infrastructure and a fragmented global supply chain—one Oklo notes is currently dominated by Russia. Oklo says it aims to help close that gap with reliable, U.S.-based production.

Put it together, and you get the full thesis: build a vertically integrated nuclear company that controls fuel inputs, produces power outputs, and captures additional value through radioisotopes. If it works, it’s multiple revenue streams and fewer choke points. If it doesn’t, it’s a lot of moving parts to get right in an industry that punishes mistakes.

XI. Current State & Recent Developments (2025)

Groundbreaking at Idaho National Laboratory

On 22 September 2025, Oklo held a groundbreaking ceremony at Idaho National Laboratory for its first commercial powerhouse: Aurora‑INL, part of the Department of Energy’s new Reactor Pilot Program.

Construction is set to be led by Kiewit Nuclear Solutions, a major industrial engineering, procurement, and construction contractor, under a master services agreement meant to bring large‑project discipline to a first‑of‑a‑kind build. Symbolically, it’s a line in the sand. For years, advanced nuclear has been plagued by “paper reactor” skepticism. Oklo is working to move the story from renderings and filings to an actual site with federal backing.

Oklo has also said it plans to have at least one reactor in the DOE program switched on by mid‑2026, aligning with a deadline designed to force speed into an industry that rarely moves quickly.

Regulatory Progress

On the fuel side, Oklo cleared a notable checkpoint. The DOE Idaho Operations Office approved the Nuclear Safety Design Agreement for Oklo’s Aurora Fuel Fabrication Facility (A3F) at INL, which was selected to participate in the DOE’s Advanced Nuclear Fuel Line Pilot Projects.

Oklo said the approval came in under two weeks—the first NSDA under the Fuel Line Pilot Projects—and framed it as evidence of a faster authorization pathway that could help unlock U.S. industrial capacity and strengthen national energy security.

Oklo and its subsidiary, Atomic Alchemy, were also selected for three DOE reactor pilot projects under the newly established Reactor Pilot Program. The program’s stated goal is to demonstrate criticality in at least three test reactors by July 4, 2026—America’s 250th birthday. It’s a deadline with marketing flair, but it’s also a forcing function: a government attempt to turn “someday” into a schedule.

Siemens Partnership

Oklo also tightened up an important part of the “sell power, not reactors” thesis: using proven industrial hardware wherever possible.

Oklo and Siemens Energy signed a binding contract for the design and delivery of the power conversion system for Aurora. Under the contract, Siemens Energy will conduct detailed engineering and layout for a condensing SST‑600 steam turbine, an SGen‑100A industrial generator, and associated auxiliaries.

The logic is straightforward. Pair novel reactor technology with commercial, widely understood turbine‑generator equipment, and you can lower execution risk, shorten timelines, and make projects easier to finance. In nuclear, “boring” is often the feature.

Q3 2025 Financial Results

The other side of the story is capital.

In Oklo’s Q3 2025 earnings reported on 11 November, the company posted an EPS loss of –$0.20 versus a consensus expectation of –$0.13. The stock slid more than 6% in after‑hours trading.

The broader point isn’t the quarter—it’s the scale of what Oklo is trying to build. A fleet of reactors and fuel‑fabrication facilities will require far more funding than the roughly $1.2 billion the company currently holds. Oklo’s own disclosures have flagged the need for substantial additional capital—whether that’s equity, project finance, or a mix—and the possibility of dilution for existing shareholders.

That’s the reality of advanced nuclear in 2025: momentum is building, partnerships are getting real, and government programs are putting dates on the calendar. But the company still has to run the gauntlet that decides whether a nuclear startup becomes an operator—or another cautionary tale.

XII. Bull Case: The Nuclear Renaissance Unfolds

For the bulls, Oklo isn’t just “a nuclear startup.” It’s a rare chance to own a company sitting where several massive waves collide: exploding electricity demand from AI, growing pressure for clean power, and a U.S. government that’s suddenly trying to make room for new reactor designs again.

Market Opportunity

Start with the simplest driver: AI data centers need a lot of electricity, and they need it all the time. As that buildout accelerates, the grid doesn’t just need “more power.” It needs new, firm generation that can run 24/7.

That’s the gap nuclear is built for. Gas can scale but carries carbon and fuel-price risk. Solar and wind can be clean and cheap, but they’re intermittent, and matching them to always-on compute loads usually means pairing them with storage and transmission that can take years to permit and build.

Oklo’s pitch is that small, modular nuclear plants can be a direct answer to that problem—purpose-built, long-duration, clean baseload for customers who don’t want to gamble their uptime on the weather.

Oklo said its latest agreement expanded its “order book” from the previously announced 2.1 gigawatts to approximately 14 gigawatts.

Of course, an order book isn’t the same thing as contracted revenue. The bull case is about conversion: if Oklo can turn even a portion of that pipeline into binding, long-term PPAs—and then actually build and operate the plants—the revenue potential becomes enormous. At full utilization, that much capacity would translate into billions in annual electricity sales once deployed.

Regulatory Tailwinds

The second pillar of the bull case is that the rules of the game may finally be shifting.

Oklo could benefit from the 2024 ADVANCE Act, which includes provisions intended to speed advanced reactor licensing and reduce costs. That includes fee reductions that could cut Oklo’s NRC hourly licensing costs by more than half, and an emphasis on faster reviews for reactors with unique safety features—exactly where Oklo positions Aurora. The company has also said it is “well-positioned to receive regulatory awards that would make licensing early plants essentially free.”

And then there’s the political posture. President Trump’s nuclear executive orders this year signaled an aggressive push to modernize regulation, streamline reactor testing, deploy reactors tied to national security needs, and strengthen the U.S. nuclear industrial base. For Oklo, the implication is clear: if Washington is serious about turning “advanced nuclear” into an American manufacturing and security priority, companies already in the arena stand to benefit.

Competitive Position: Applying Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers

One way to frame Oklo’s advantage is through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers—how enduring competitive moats actually get built.

- Process Power: Oklo’s integrated approach—reactor development, owning and operating plants, fuel recycling, and radioisotopes—creates operational complexity that’s hard to copy, even for well-funded competitors.

- Cornered Resource: Access to EBR-II fuel material and deep relationships with DOE and national laboratories are scarce assets in a world where fuel and siting can decide who ships first.

- Counter-Positioning: Traditional nuclear incumbents are built around a different business model and a different cadence. Moving to a startup-like approach could threaten their existing businesses.

- Scale Economies: If Oklo can move from “first plant” to “fleet,” it can spread fixed engineering, licensing, and supply-chain investments across many deployments.

- Network Effects: Limited in nuclear, where customers don’t choose a reactor because other customers did.

- Switching Costs: Long-term PPAs can lock customers in for decades, especially if Oklo is providing dedicated, on-site or near-site power.

- Brand: Oklo’s visibility has grown as one of the leading advanced nuclear pure-plays, especially in the AI-energy conversation.

XIII. Bear Case: The Risks Are Real

For bears, Oklo is the clean-energy version of a classic public-market trap: a compelling vision, a massive addressable market, and a painfully long distance between here and cash flow. In nuclear, that distance isn’t measured in quarters. It’s measured in years, regulators, and concrete.

No Revenue, Significant Losses

Oklo still hasn’t generated revenue. And it’s already spending like a company preparing for prime time, posting net losses of about $25 million in the second quarter and about $55 million for the year ending in June.

In its own regulatory filings, Oklo has also acknowledged a harder truth: it hasn’t yet signed a contract committing to deliver electricity or heat. That means investors are underwriting a story that hasn’t crossed the most basic commercial milestone—selling the thing it exists to sell.

Non-Binding Agreements

A lot of what looks like traction is still provisional.

Many of Oklo’s agreements—including those tied to AI data centers and the Air Force—are non-binding, or sit at the letter-of-intent / notice-of-intent stage. The path from “we’d like to buy power” to “power is flowing under a long-term PPA” runs straight through licensing, construction, commissioning, and operations. Any one of those steps can stretch timelines.

Oklo’s own guidance has pointed to first power from Aurora‑INL around 2027–2028. Bears see plenty of ways that date could slide—regulatory process, technical details, supply-chain realities, or funding.

And then there’s the Switch agreement. Twelve gigawatts makes for a great headline, but it’s non-binding. Converting that framework into actual power delivery requires the hardest part: getting a reactor deployed, approved, and operating—and then repeating it, over and over, for years.

Valuation Concerns

Oklo’s valuation has, at times, looked detached from traditional fundamentals.

The company has been valued far ahead of revenue, with a price-to-book ratio of 22.6x—well above the sector—and no sales projected until 2027. That’s the kind of setup where sentiment drives the stock more than performance, and where any bad news—an engineering delay, a licensing snag, a financing hiccup—can hit harder than it “should.”

Oklo’s stock has also drawn a growing short base. Koyfin data shows short interest rising to 9.20%, up from 0.03% in June. Whether shorts are ultimately right or wrong, the message is clear: a meaningful slice of the market is betting that the timeline, the economics, or the credibility of the plan won’t hold.

Technical and Regulatory Risk

At the core of the bear case is the simplest point: Oklo has never operated a commercial reactor.

Yes, EBR‑II provides real heritage and real confidence in the physics. But turning that heritage into a commercially deployable product—built on schedule, licensed cleanly, run reliably, and scaled into a fleet—is a different game. Nuclear doesn’t just punish failure. It punishes surprise.

And the global proof points are thin. Today, the only commercially operating liquid‑metal fast reactors are in Russia. China and India have experimental units in operation. All of them took decades to develop. That doesn’t mean Oklo can’t move faster—but it does mean history is not on the side of “fast.”

Capital Requirements

Even if the technology works, the balance sheet has to keep up.

Oklo is attempting to raise up to $1 billion in additional capital. And building a fleet of reactors will require far more than what the company has today—likely implying dilution for existing shareholders, plus the challenge of securing project financing for first-of-a-kind plants in a market that still has nuclear scar tissue.

For bulls, that’s simply the cost of building infrastructure. For bears, it’s the point: the company may have to raise, and raise again, long before it ever proves it can deliver a single electron at scale.

XIV. Key Performance Indicators for Investors

If you’re trying to track Oklo like a business—not a story—you can boil most of the signal down to three metrics.

1. Binding PPA Conversion Rate

This is the clearest tell.

Oklo has talked about an “order book” of roughly 14 gigawatts of potential capacity, but the important word is potential. Today, most of that pipeline is still letters of intent, master agreements, and other non-binding structures.

What changes the game is when Oklo starts announcing executed, binding power purchase agreements with real commercial teeth: defined pricing, a defined delivery schedule, and clear conditions for what happens if milestones slip. That’s the moment demand stops being enthusiasm and becomes contractual reality.

2. Regulatory Milestone Achievement

In nuclear, progress is measured in gates. Oklo’s valuation won’t be driven by incremental prototype updates as much as by whether it clears each regulatory checkpoint.

The milestones to watch are straightforward: - a new combined license application submission, which the company has indicated is expected in 2025 - progress against the DOE Reactor Pilot Program timeline, with a target of July 4, 2026 - whether Aurora-INL actually reaches operation on the company’s stated timeline of 2027–2028

Each of these reduces uncertainty. Miss enough of them, and the market starts to assume the timeline is fiction.

3. Cash Burn vs. Capital Raise Trajectory

Even if the technology and the customer demand are real, Oklo still has to fund its way through first-of-a-kind deployment—and that’s expensive.

So investors have to keep one eye on quarterly cash levels and another on the pace of spending. The third eye—if you can grow one—goes to the next capital raise: when it comes, how large it is, and what it costs existing shareholders in dilution.

In a company like this, financing terms can matter almost as much as engineering terms.

XV. Material Risks and Regulatory Considerations

Legal/Regulatory Overhangs

Oklo is trying to build a startup in one of the most tightly controlled industries in the country. That reality doesn’t just shape the timeline—it can decide whether the company gets to ship at all.

A few risks sit at the center of the story:

- NRC licensing: The 2022 denial was a reminder that progress isn’t linear, and approval is never automatic. In nuclear, “we’ll fix it later” isn’t a plan—the application has to be complete, in the regulator’s language, before the process can move.

- Proliferation concerns: Oklo’s approach—metal-fuel, sodium-cooled fast reactors and recycled, plutonium-bearing fuel—has drawn criticism from some nuclear engineers and non-proliferation experts. Oklo and the Department of Energy, meanwhile, argue the fuel form is highly resistant to misuse. Either way, this is the kind of debate that can slow progress and raise the bar for scrutiny.

- HALEU supply chain: Even if the reactor is ready, the industry still has a gating factor: access to enriched fuel. HALEU availability remains a constraint across advanced nuclear, and it’s not a problem any one company can fully solve on its own.

Accounting Considerations

Oklo is still pre-revenue, so the financial statements tell a different story than they would for a mature power company. Most of what shows up on the income statement is the cost of building the machine: research and development, administrative overhead, and stock-based compensation.

That makes the fine print matter. Investors tend to focus on a few areas in particular: - how the company capitalizes (or doesn’t capitalize) development costs - how stock-based compensation flows through the numbers and what it implies for dilution over time - how DOE awards and grants are treated in the financials

XVI. Conclusion: Nuclear's Startup Revolution

Oklo’s story comes down to a single, audacious question: can startup thinking reshape one of the most regulated, capital-intensive industries in America?

In just over a decade, the company has done things that used to sound like category errors. It brought nuclear into Y Combinator. It convinced venture capitalists to fund reactor development. It pushed an advanced reactor design into an NRC process that wasn’t built for it. And it got in the room with the customers who increasingly define the next era of electricity demand: the biggest technology companies on Earth.

There’s even a surreal moment that captures how far the conversation has shifted. In May 2025, Jacob DeWitte appeared at the White House as President Donald Trump signed executive orders aimed at advancing nuclear energy policy. A nuclear startup founder, in the Oval Office, as the federal government tried to put real momentum behind a “nuclear renaissance.” That would have been unthinkable not long ago.

Public markets have also treated Oklo like a proxy for that renaissance. DeWitte and Caroline Cochran—the husband-and-wife founders—became new billionaires as Oklo’s shares surged, driven largely by a growing belief that nuclear power could become a cornerstone of the energy-hungry AI boom.

But none of that is the finish line. It’s the prologue to the hard part.

Oklo still has to convert headline-grabbing, often non-binding agreements into binding power purchase contracts. It has to get through licensing in a way that holds up to scrutiny. It has to raise the kind of capital that infrastructure demands. And it has to do what the industry ultimately cares about most: build, operate, and reliably deliver power.

These are the steps that have broken larger, better-funded companies with deeper institutional history. Nuclear doesn’t grade on potential. It grades on commissioning.

Sam Altman once said Oklo “is the best positioned player to pursue commercialization of advanced fission energy solutions.” Maybe. But whether that ends up true won’t be decided by narrative, stock charts, or proximity to the AI boom. It’ll be decided by execution—under regulation, under schedules, and under the unforgiving reality of steel, concrete, fuel, and physics.

What is already clear is that Oklo has put itself in the center of one of the most important energy transitions in a generation. And for the kid who once stared at a tiny fuel pellet in Albuquerque and saw a future hidden inside it, the dream is closer than it’s ever been.

Now comes the part where the dream has to work.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music