Organon & Co.: The Story of Women's Health Carved from Pharma Giants

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

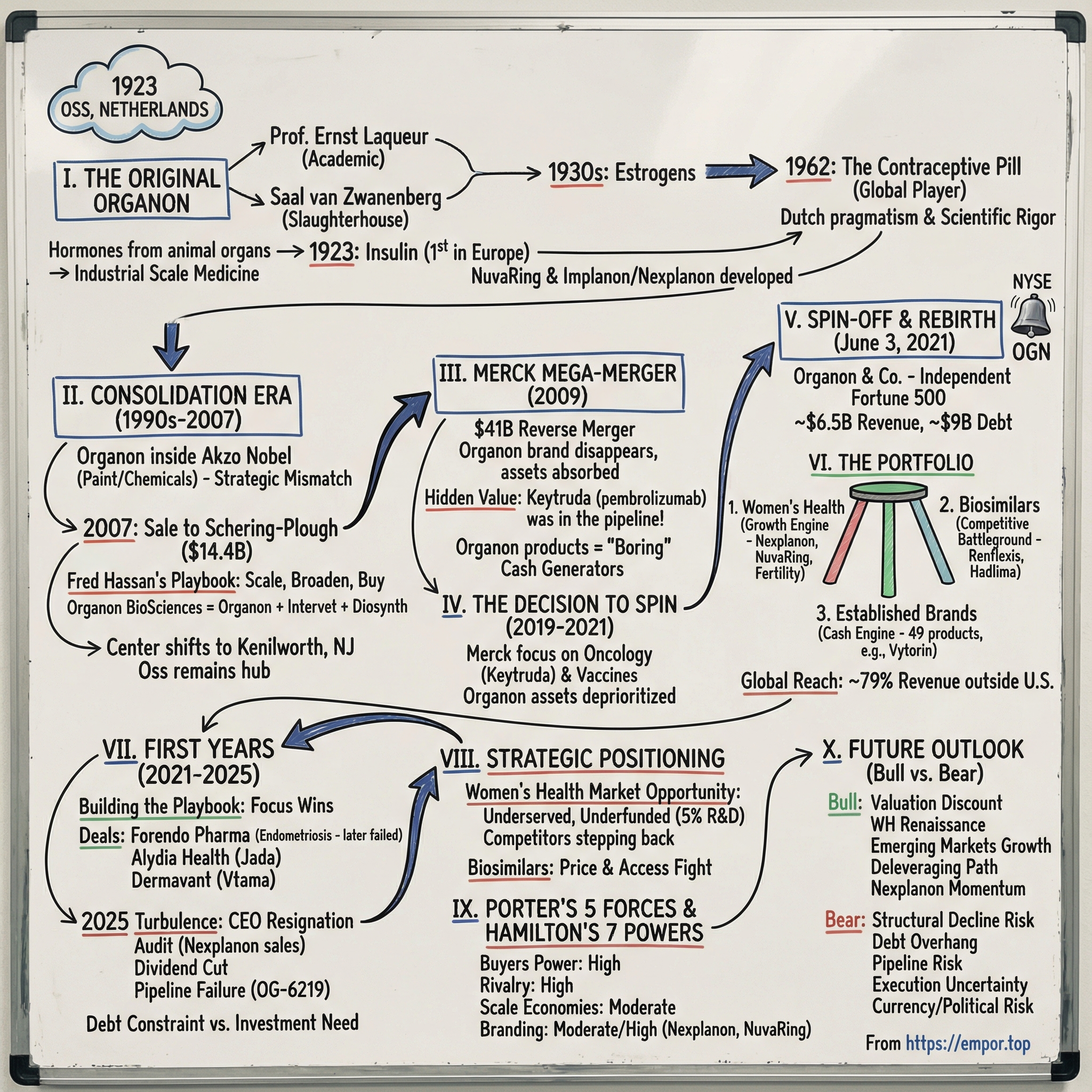

Picture this: it’s June 3, 2021. A company walks onto the floor of the New York Stock Exchange and rings the opening bell. The ticker is OGN. The name on the screen is Organon.

And yet, to most of the market, it might as well have been a startup—an overnight Fortune 500 with more than $6 billion in revenue, created through the corporate alchemy of a spin-off.

That’s the audacious question at the heart of this story: how does a nearly 100-year-old pharmaceutical brand become a brand-new public company overnight?

Organon began life in 1923 in Oss, in the Netherlands. Over the decades it passed through the hands of much larger owners, until it ended up inside Merck & Co. Then, in June 2021, Merck did something that sounds simple and is anything but: it carved out a portfolio of women’s health, biosimilars, and established medicines—and sent it into the world as an independent company. The Organon name resurfaced like something pulled from the archives, polished up, and reintroduced with a new mission.

But the “new” Organon is really a company with multiple lives: a story of Dutch scientific pioneers, billion-dollar M&A, years of strategic neglect inside Big Pharma, and finally, rebirth under the harsh light of the public markets.

It’s also a story about the economics of what people casually call “boring” pharma: contraceptives, fertility treatments, and off-patent medicines that can throw off enormous cash, even as they struggle to win attention on Wall Street. It’s about why spin-offs happen, what they unlock, and what they saddle the newborn company with—especially when patent cliffs and generic competition are always somewhere on the horizon.

And it’s about an opportunity hiding in plain sight: women’s health. McKinsey research has pointed out that female-only conditions account for just 4 percent of pharmaceutical R&D spending. Other estimates put women’s health at roughly 5 percent of global healthcare R&D funding. Either way, the takeaway is the same: a massive category, chronically underfunded—creating both a moral imperative and a commercial white space that Organon wants to own.

So here’s how this episode unfolds. First, we’ll go back to the original Organon: the Dutch roots, the scientific legacy, and how women’s health became part of the company’s DNA. Then we’ll track the consolidation era—Akzo Nobel to Schering-Plough to Merck—where Organon the brand effectively disappears, even while its products keep generating cash. Finally, we’ll get to the modern chapter: the 2021 spin-off and the first years of independence, where the company has to prove it’s more than a portfolio of mature assets with a new logo.

Because that’s the real question Organon has been asked since day one: can a company built on established, increasingly genericized products reinvent itself—into a focused, growing leader in women’s health—while standing on its own?

II. The Original Organon: Dutch Origins & Scientific Legacy (1923–1990s)

To understand Organon, you have to start in Oss, a small Dutch town in the early 1920s—where one of the most unlikely pairings in pharma history took shape: an academic endocrinologist and a slaughterhouse owner.

Organon was founded in 1923 as a partnership between Professor Ernst Laqueur, a physiologist and endocrinologist at the University of Amsterdam, and Saal van Zwanenberg, who ran Zwanenbergs Slachterije en Fabrieken, a slaughterhouse and factory operation in Oss in North Brabant.

The setup sounds almost absurd by modern standards, but it was perfectly suited to the science of the time. Animal organs from the slaughterhouse contained hormones. If you could extract and purify those compounds reliably, you could turn biology into medicine at industrial scale.

Even the name carried that scientific ambition. “Organon” comes from ancient Greek and means “an instrument for acquiring knowledge.” It wasn’t just branding. It was a mission statement: this would be a company built around turning emerging biological insight into real therapies—especially in endocrinology, where hormones were becoming one of the great frontiers of medicine.

The founding itself was a break from the norms of Dutch science and industry. As one account put it, Dutch scientists couldn’t easily partner with a homegrown pharmaceutical industry because, in the 1920s, there wasn’t really a Dutch pharma company doing organ preparations at all. So Laqueur didn’t simply consult—he helped create the vehicle.

Organon’s early credibility came fast. In its inaugural year, the company launched insulin, becoming the first company in Europe to commercialize this life-saving treatment for diabetes. That accomplishment matters for two reasons: it showed Organon could manufacture complex biological medicines, and it set a tone that the company wasn’t going to be a niche local supplier—it was going to compete on innovation.

After insulin, the company leaned deeper into what would become its defining domain. In the 1930s, Organon expanded into estrogens. The playbook emerged: isolate hormones from biological material, purify them, standardize them, and get them into clinics.

Then came the inflection point that would put Organon on the global map. In 1962, Organon introduced the contraceptive pill. It’s hard to overstate what that did to the company’s trajectory. This wasn’t just a successful product—it was medicine colliding with one of the biggest societal shifts of the twentieth century. The pill turned Organon into a world player and made it an economic engine for the region around Oss.

From there, the company kept building on the same foundation: reproductive health, hormones, and delivery innovation. Over time, Organon would develop NuvaRing, its vaginal ring contraceptive, and Implanon—later known as Nexplanon—a long-acting contraceptive implant. Across decades, the Organon name became associated with advances in women’s health “like no other,” including both early birth control pills and the then-novel idea of a vaginal ring.

What made this era distinctive wasn’t only the product list. It was the culture behind it: Dutch pragmatism paired with serious scientific rigor. Organon invested in R&D and expanded its footprint. One notable move was the acquisition of the Newhouse research site in Scotland in 1948, which strengthened its research capabilities. Even as it grew internationally, it kept Oss at its core, and it built manufacturing depth that would become a quiet strategic asset later—especially once the company started changing hands.

By the 1990s, Organon had become a specialty pharma company with deep expertise in reproductive health, fertility treatments, and central nervous system medicines. Its portfolio included products like Follistim for fertility and Zemuron, a muscle relaxant, alongside a broad range of contraceptive options. Revenue had approached $3 billion, with operations spanning Europe, the Americas, and Asia.

And yet, the next twist in the story was already baked in. Organon now lived inside Akzo Nobel—a Dutch conglomerate known far more for paints, coatings, and specialty chemicals than pharmaceuticals. No matter how strong Organon’s science was, it was still a strategic odd fit.

That mismatch is one of the recurring forces in Organon’s history: a valuable business that doesn’t quite belong where it sits. The question hanging over the 1990s was simple—and ominous. When an asset is both successful and misaligned, what does the parent company do with it?

The answer would shape Organon’s next life. But the DNA forged in these decades—women’s health focus, hormone expertise, and a global manufacturing footprint—would survive every ownership change. And when the company was reborn in 2021, it would deliberately reach back to this era, reviving the Organon name because of what it had come to represent.

III. The Akzo Nobel Era & Sale to Schering-Plough (1990s–2007)

By the mid-2000s, pharma was living with a brutal paradox. The blockbuster model—one patented molecule that could throw off billions—was still the engine of the industry. But it also built in a timer. When patents expired, revenue didn’t taper. It fell off a cliff. So across the sector, companies were hunting for ways to refill pipelines fast, and more and more, the answer was M&A.

Inside Akzo Nobel, Organon was exactly the kind of asset that creates tension in a boardroom. It was profitable and respected—but it didn’t fit. Akzo’s world was paints, coatings, and specialty chemicals: different cycles, different regulations, different muscle memory. Organon, meanwhile, required deep pharmaceutical expertise and constant strategic attention. It performed, but it wasn’t core.

That’s when Fred Hassan showed up in the story. Hassan had taken Schering-Plough from a struggling pharma company and turned it into a deal-driven contender. His playbook was simple and aggressive: build scale, broaden the portfolio, and buy what you can’t build quickly enough.

Organon was a clean match for that strategy.

Schering-Plough’s agreement to acquire Organon BioSciences was announced on March 12, 2007. The deal closed in November, with Schering-Plough framing it as “creating a stronger combined company with broader human and animal health portfolios, an enhanced pipeline and increased R&D capabilities.”

The headline number got everyone’s attention. Schering-Plough was paying $14.4 billion to buy Akzo Nobel’s drug unit—and with it, a ready-made suite of women’s health products and a slate of late-stage experimental medicines.

Hassan laid out the logic in plain terms: “With Organon, we expand into two important prescription pharmaceutical franchises, women’s health and central nervous system (CNS). These therapeutic areas add to our existing strengths in cardiovascular care, respiratory, immunology and oncology.”

But this wasn’t just a shopping trip for a few brand names. What Schering-Plough really bought was an integrated platform. Alongside the Organon business, it picked up Intervet in animal health, Diosynth as an active pharmaceutical ingredient manufacturer, and vaccine production capabilities through Nobilon. Organon BioSciences, as a bundle, was Organon, Diosynth, and Intervet—products, manufacturing, and infrastructure in one package.

On day one, the acquisition also upgraded Schering-Plough’s commercial lineup. The company pointed to Organon products that would now sit among its leading prescription brands: FOLLISTIM/PUREGON for fertility, ZEMURON/ESMERON as a muscle relaxant, and NUVARING and IMPLANON for contraception.

And then there was the promise of what came next. Hassan emphasized that the deal didn’t just add revenue; it added shots on goal: “We expand and strengthen Schering-Plough’s late-stage Rx pipeline with five additional promising Phase III compounds.” At the time, those compounds were mostly just line items in investor decks—potential energy waiting to be converted into something real.

For Organon, though, the meaning of the deal was simpler and more emotional. This was the end of the independence that had lasted, in one form or another, since 1923. The corporate center of gravity shifted from Oss to Schering-Plough’s base in Kenilworth, New Jersey. Still, Schering-Plough was careful to preserve Organon’s Dutch engine room: “Organon’s research and manufacturing facility in Oss, the Netherlands, will be the center of Schering-Plough’s global gynecology and fertility activities.”

So the heritage stayed. But control moved.

And here’s the twist: Hassan wasn’t just collecting assets—he was also changing the shape of Schering-Plough itself. As one summary put it, “The Organon acquisition, which strengthened Schering and gave it a more diversified drug pipeline, made Schering itself an appealing takeover target.”

That’s the irony. In trying to make Schering-Plough bigger, broader, and harder to ignore, Hassan may have made it irresistible.

Organon’s next life wouldn’t be defined by what Schering-Plough did with it. It would be defined by what happened to Schering-Plough.

IV. The Merck Mega-Merger: Organon Disappears (2009)

The 2008 financial crisis didn’t just rattle banks. It rewired the entire corporate landscape. In pharma, the timing couldn’t have been worse: blockbuster drugs were marching toward patent cliffs, pipelines were thinning, and capital markets suddenly weren’t there to cushion the fall. The industry’s instinct was the same as always in a downturn—get bigger, faster.

In late January 2009, Pfizer kicked off the consolidation wave with its $68 billion deal for Wyeth. Merck wasn’t going to sit still. On March 9, 2009, it announced it would acquire Schering-Plough in a deal valued at $41 billion:

"The pharmaceutical giant Merck announced Monday it is acquiring rival Schering-Plough in a deal valued at $41 billion. Merck will pay a hefty premium for Schering in the cash and stock deal, which has already been approved by both boards."

The backdrop was brutal. Markets were in free fall; the S&P 500 was roughly half its 2007 peak. But for Merck, this wasn’t opportunism as much as necessity. The company had long believed its science-first culture was enough. Now even Merck was conceding that the old model—stay independent, out-innovate everyone—wasn’t a plan. As one report put it:

"The planned purchase is a major change of course for Merck, which long maintained that its own science-driven culture was sufficient to create strong sales growth. But earlier this year, Merck CEO Richard T. Clark told investors that, in the current challenging climate, the company could no longer rule out acquisitions of scale."

The mechanics of the deal were just as telling as the headline price. Merck structured it as a reverse merger:

"The transaction will be structured as a 'reverse merger' in which Schering-Plough, renamed Merck, will continue as the surviving public corporation."

"Merck shareholders are expected to own approximately 68 percent of the combined company, and Schering-Plough shareholders are expected to own approximately 32 percent."

That structure wasn’t an accounting parlor trick—it was strategic. It helped preserve Schering-Plough’s existing partnership agreements, especially the lucrative Remicade franchise with Johnson & Johnson. And it created, overnight, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies.

But here’s the key question for our story: what did Merck actually want?

Because when you look closely, you can see where Organon landed on Merck’s priority list—and it wasn’t near the top.

One of the great ironies of this merger is that the single most valuable thing to come out of the Schering-Plough orbit wasn’t what anyone was talking about in 2009. It was a molecule sitting quietly in the pipeline:

"Keytruda was originally from Organon, and when S-P bought them in 2007, it wasn't even mentioned in the press release or the articles written at the time. So it's a pretty safe bet that Merck's management would have been nonplussed to hear that Keytruda would turn out to be the best thing that they got out of the deal."

That compound—pembrolizumab, later branded as Keytruda—wasn’t the star of the announcement. It wasn’t even close. Years later, it would become one of the best-selling drugs in pharmaceutical history, generating more than $25 billion a year by the 2020s. In 2009, though, the spotlight stayed on the assets that seemed more immediate: the Remicade economics, vaccines, and the late-stage pipeline that could plug holes faster.

The merger closed in November 2009:

"On November 4, 2009 Merck & Co. merged with Schering-Plough with the new company taking the name of Merck & Co."

For Organon, this was the moment the curtain fell. A brand that had made it from a Dutch slaughterhouse-adjacent lab in 1923, through Akzo Nobel, and then through Schering-Plough, now effectively dissolved into Merck’s corporate structure. The products didn’t vanish—NuvaRing, Nexplanon (the evolved version of Implanon), Follistim, and many more kept selling. But the Organon name itself was shelved. The identity that once anchored a whole scientific culture got absorbed into the portfolio of a much larger machine.

What came next is what you might call the hidden years: more than a decade where these assets kept doing their job—generating cash—while getting less and less strategic oxygen.

Inside Merck, Organon’s former women’s health products and a long list of established brands slotted into an unglamorous but vital category: dependable cash generators, not growth bets. Organon would later describe that reality bluntly:

"Our day one portfolio consists of many well-known products that were once core to Merck's business but have since strategically received limited resources and investment."

That wasn’t a moral failure. It was how Big Pharma works. Merck was increasingly oriented around the areas where it could build the next decade of growth—oncology and vaccines. As Keytruda rose, and as Merck leaned into franchises like Gardasil, everything else competed for attention against businesses with massive upside and board-level urgency.

And that’s where the idea of a spin-off begins to form—not in a single board meeting, but in the slow accumulation of deprioritized decisions. As one account put it:

"The CEO of Merck at that time, Ken Frazier, approached me because he thought that the more than 60 products that today are represented by Organon were deprioritized, receiving no major investment at a time when Merck was mainly focusing on oncology and vaccines. Ken knew that these products had a second life to them, and that in the hands of a separate organization they would do much better."

That’s the seed. Not that the products were broken—they weren’t. The problem was fit. They were valuable, but they weren’t central to Merck’s story. They were maintained, not nurtured. Kept alive, not pushed forward.

And in a way, that’s the most important setup for everything that happens in 2021: Organon didn’t get spun out because it was failing. It got spun out because, inside Merck, it could never truly be the main character again.

V. The Decision to Spin: Merck's Strategic Calculus (2019–2021)

By 2019, Merck’s transformation was essentially complete. Keytruda had turned into the company’s gravitational center. Vaccines were thriving. The oncology pipeline was expanding. And that success created an awkward, very Big Pharma problem: what do you do with a portfolio of mature products that still throws off cash, but no longer fits the story you’re telling Wall Street?

Merck was increasingly explicit about where it wanted to spend its time and credibility:

"Merck stressed its commitment to what it deemed as its growth pillars in oncology, vaccines, hospital and specialty products, and animal health, which it expects will drive approximately 90% of Merck's revenue growth post the spin-off."

Once you say that out loud, the rest of the portfolio gets reclassified. Not as “bad,” but as non-core. These assets can be profitable and still become strategically heavy: they take attention, they add operational complexity, and they muddy the narrative of a company trying to look like a focused growth machine.

Merck put that simplification into concrete operating terms:

"Merck explained at the time of the announced spin-off in February 2020 and again in an investor presentation in May 2021 that spin-off would reduce Merck's human health manufacturing footprint by approximately 25% and the number of human health products it manufactures and markets by approximately 50% to allow for a more focused operating model in support of its growth products."

The formal announcement arrived on February 5, 2020—just weeks before COVID-19 would upend the world. If anything, the pandemic reinforced the logic. When everything is stressed, focus stops being a buzzword and becomes survival strategy.

Merck tapped Kevin Ali to build the spin-off. Ali was a 35-year Merck veteran who had run international operations—exactly the kind of executive who understood how to operate across dozens of countries without needing headquarters to micromanage every move. As one account described it:

"About 30 years after Ali walked out of the auditorium in Berkeley and into a lifelong Merck career, he was presented with a new challenge by his mentor, then-Merck CEO Kenneth Frazier, to create the new company that would become Organon."

Frazier’s pitch was simple and almost daring:

"I know you're used to dealing with all the international markets and so many of our people outside of the US. Now see if you can make a company out of it."

Ali’s mandate came with real shape. Frazier, who retired as CEO the following year, offered him a portfolio and a thesis:

"Frazier, who retired as CEO last June, offered Ali a chance to come back with a value proposition that included 64 products and two potential growth components, women's health and biosimilars, as well as an established brands portfolio that would provide a stable foundation for the business."

That value proposition was the core bet: harvest cash from established brands, build a more focused women’s health leader, and use biosimilars as a second engine. Ali framed the ambition bluntly:

"I see a future here if we focus on something that no other company our size has focused on so far, being a women's health global leader."

And the timing mattered. As the category was being deprioritized by many large pharmaceutical companies, focus could become a form of differentiation:

"Big Pharma companies have been backing away from women's health in recent years, with Merck & Co. being the latest example."

Of course, the strategy was the easy part. The execution was the monster.

Spinning out a global pharma business isn’t like splitting a product line. Organon needed its own IT systems, its own supply chain, its own manufacturing and quality infrastructure, and its own commercial teams—across dozens of markets—without missing shipments or tripping regulatory wires. It was a corporate heart transplant while the patient kept running.

By Merck’s own reporting, the scale was significant right away:

"The new company consists of approximately 9,000 employees, which represented 12% of Merck's global workforce as of December 31, 2020."

Then came the part that would define Organon’s first years: the capital structure.

"In connection with the spinoff, Merck received a distribution from Organon of approximately $9 billion."

Translation: the new company would be born with a major debt load so Merck could extract value on the way out. Organon launched at roughly $9 billion of debt against about $6.5 billion in revenue. From day one, that leverage constrained what the company could do next—how aggressively it could invest, how freely it could pursue deals, and how patient it could afford to be.

From Merck’s perspective, the logic was clean: slim down the company, sharpen the focus on its growth pillars, and pull cash out of mature assets via debt. From Organon’s perspective, it was a steep hill to climb, immediately.

And then, the handoff.

"Merck completed the spinoff and Organon & Co. became a publicly traded company on June 3, 2021."

The market debut was tightly choreographed:

"Thursday, Merck officially spun off Organon with its women's health, legacy products and biosimilars franchises, which collectively brought in $6.53 billion in sales last year. The newco will debut on the New York Stock Exchange today under the symbol 'OGN.'"

Ali, now CEO of a company that was “born big,” sounded equal parts energized and exhausted:

"Veteran pharma leader Kevin Ali, today CEO of Organon, the nascent women's healthcare spinoff of Merck & Co., speaks proudly of his time with the global independent company so far—one he acknowledges may be his most fulfilling—and exhaustive—assignment yet. 'It is the happiest and most excited I've ever been in my entire life and I've spent 35-plus good years in the industry.'"

Wall Street’s initial reaction, though, was cooler. Investors saw what Merck had effectively packaged up: a portfolio of mature, increasingly genericized assets, plus biosimilars—wrapped in a new ticker and paired with a lot of debt. The question wasn’t whether Organon could operate. It was whether it could build a second act.

Survive, sure. But could it actually thrive?

VI. The Organon Portfolio & Business Model Deep Dive (2021–Present)

To understand Organon, you have to understand the three-legged stool it was born with: Women’s Health, Biosimilars, and Established Brands. Each leg plays a different role. One is the identity. One is the knife fight. One is the cash register.

Women's Health: The Growth Engine

In 2024, Organon generated $1.8 billion in women’s health revenue, with Nexplanon doing a lot of the heavy lifting. This is the company’s highest-margin, fastest-growing franchise—and the clearest expression of what Organon wants to be.

The heart of the portfolio is contraception and fertility, and the crown jewel is Nexplanon, a long-acting reversible contraceptive implant. Organon describes it plainly: it’s among the most effective forms of hormonal contraception, with a low long-term average cost. It’s inserted just under the skin in a patient’s arm and works for up to three years—no daily pill, no weekly routine, no monthly refill cadence. That “set it and forget it” convenience is the point, and it’s why long-acting methods have steadily gained acceptance with both patients and providers.

That momentum has shown up in the numbers. Nexplanon growth of 14% (ex-FX) put it on track to exceed $1 billion in revenue in 2025. For a product that’s been on the market for years, that’s not supposed to happen. It’s a sign that the category is still expanding—and that Organon has been pushing it harder than a giant parent company ever would.

NuvaRing, the other marquee contraceptive brand, tells the opposite story. In the same period that Nexplanon grew, NuvaRing fell sharply, with Organon attributing the decline to ongoing generic competition. It’s the recurring reality of mature pharma: even products with differentiated delivery forms eventually get dragged into price pressure once exclusivity is gone.

Then there’s fertility. Organon’s portfolio includes Follistim, used in assisted reproductive technology. The company said the fertility portfolio grew about 9% ex-FX for the full year 2022. The underlying driver is straightforward: as more people delay having children, demand for IVF and related treatments rises. It’s not a mass-market business like contraception—but it has durable demand and clear demographic tailwinds.

Biosimilars: The Competitive Battleground

Biosimilars are where Organon goes from brand-building to trench warfare. The pitch is simple: lower-cost versions of blockbuster biologic drugs in areas like oncology and immunology. The execution is not.

Organon’s lineup includes Renflexis (Remicade), Hadlima (Humira), Ontruzant (Herceptin), and Brenzys (Enbrel). In the fourth quarter of 2024, biosimilars revenue declined 18% both as reported and ex-FX versus the prior year quarter. Organon pointed to a few specific drivers: the timing of tenders in Brazil for Ontruzant and Brenzys, plus a 16% ex-FX decline in Renflexis from competitive pricing pressure in the U.S. The bright spot was Hadlima, which continued to ramp following its U.S. launch in July 2023.

The bigger point is structural. Biosimilars don’t get to compete on novelty. They compete on price, contracting, and access. That means scale matters—a lot. And Organon doesn’t have the same commercial muscle here as the largest biosimilar specialists.

Established Brands: The Cash Engine

Established Brands is the part of the portfolio that doesn’t get people excited—and that’s exactly why it exists. Organon has described it as 49 products across areas like respiratory, cardiovascular, dermatology, and non-opioid pain. These are mostly brands that have already gone off-patent in most markets, with only modest remaining loss-of-exclusivity exposure beyond 2021.

Some of these products are still meaningful to the overall mix. Organon notes that cardiovascular products such as Vytorin make a combined 24% of company revenue. But the economics here are very different from Women’s Health: many of these products face generics and declining volumes in developed markets. The strategic job is to keep them efficient and cash-generative.

That cash matters because it pays for everything else: servicing the debt the company was born with, supporting dividends, and—most importantly—funding deals and pipeline-building moves that can keep Women’s Health from becoming a single-product story.

In the fourth quarter of 2024, Established Brands revenue grew 2% both as reported and ex-FX. Organon attributed that largely to contributions from Emgality and Vtama, which more than offset the impact of the loss of exclusivity of Atozet in key European markets and in Japan. That’s the Established Brands playbook in action: manage erosion, and use selective additions to keep the cash engine running.

Geographic Mix: The Emerging Markets Advantage

If you want the clearest fingerprint of Organon’s Merck heritage, look at where it sells. Around 79% of revenue has been generated outside the U.S.—an unusually international profile for a U.S.-listed pharma company.

Organon itself has highlighted that global reach: in 2023 it recorded $6.3 billion in revenue, operated in more than 140 countries and territories, and generated about 76% of that 2023 revenue internationally.

This is both the opportunity and the tradeoff. In the U.S., many of these products lost exclusivity long ago. Internationally—especially in emerging markets—branded, trusted medicines can hold on longer, and volume growth can do real work. The flip side is that you inherit emerging-market realities: currency swings, policy shifts, tender timing, and regulatory unpredictability.

Put it all together and you get Organon’s operating model in one line: use established medicines to generate cash, use women’s health to build a future, and use biosimilars to compete where price and access rule the day.

VII. The First Four Years: Independence, Execution, and Turbulence (2021–2025)

Building the Playbook

From day one, Organon’s leadership tried to square a weird circle: act like a focused, hungry challenger while inheriting the footprint of a global incumbent. Kevin Ali captured the tension with a line that sounded half joke, half warning: “Organon has about 9,500 ‘founders,’ but if something goes bump in the night, that’s on me.”

By early 2023, Ali was publicly projecting confidence. “We enter 2023 with momentum, building off the significant achievements in our short history as an independent company,” he said. And he pointed to tangible proof points: multiple quarterly sales records for Nexplanon, two straight years of double-digit biosimilars growth, and what he framed as the durability of the Established Brands franchise.

But Organon also knew it couldn’t just run the portfolio it was handed. To be a real women’s health company—and not simply a well-managed collection of mature products—it needed more pipeline, more platforms, and more shots on goal. So it went shopping.

In 2021, the company completed its acquisition of Forendo Pharma, describing it as a women’s health-focused clinical-stage developer. The price structure signaled both ambition and caution: “Consideration for the transaction includes a $75 million upfront payment, assumption of approximately $9 million of Forendo debt, payments upon the achievement of certain development and regulatory milestones of up to $270 million and commercial milestones payments of up to $600 million, which together could amount to total consideration of $954 million.”

The strategic target was endometriosis—an enormous, underserved condition affecting up to 10% of women of reproductive age, with limited treatment options. Forendo’s lead program was positioned as a bet on a novel mechanism, with the potential for a non-hormonal approach.

Organon layered in other deals, too: it acquired Alydia Health for the Jada postpartum hemorrhage device, licensed products from ObsEva, and broadened its reach into dermatology through the Dermavant acquisition. As Organon put it, “Vtama was acquired as part of Organon’s acquisition of Dermavant Sciences Inc., which closed on October 28, 2024.”

Financial Performance

Operationally, the company could point to stability—especially given the debt load it carried out of the spin. Organon reported: “Full year 2024 revenue of $6.4 billion, up 2% as-reported and 3% at constant currency. Full year 2024 diluted earnings per share of $3.33.”

It underscored the trend line too: “For the full year 2024, revenue was $6,400,000,000 representing a 3% growth rate at constant currency. This is the third consecutive year that Organon has delivered constant currency revenue growth.”

But the physics of the portfolio never went away. In 2025, management guided to a softer year: “The company’s guidance for 2025 projects revenue between $6.125 billion and $6.325 billion.” The key driver was painfully familiar in pharma—loss of exclusivity—specifically for Atozet, which the company described as its second-largest product, in key European and Japanese markets.

The 2025 Turbulence

Then, late 2025 brought the kind of turbulence that doesn’t show up in a revenue bridge—governance, credibility, and leadership.

Organon disclosed that CEO Kevin Ali resigned, alongside the results of an internal audit committee investigation. The company said the investigation “uncovered improper wholesaler sales practices related to its contraceptive implant, Nexplanon,” and described findings that “certain wholesalers were encouraged to purchase more product than needed in order to meet revenue expectations.”

Joe Morrissey stepped in as Interim CEO, saying, “I am humbled to be working alongside our talented team during this pivotal time for Organon.”

At the same time, the balance sheet started dictating strategy more loudly. Organon had long positioned its $0.28-per-share quarterly dividend as its “number one capital allocation priority.” But on May 1, 2025, it reversed course dramatically, cutting the dividend to $0.02 per share and pointing to a shift toward debt reduction.

And one of the company’s most visible pipeline bets unraveled. Organon had picked up the endometriosis program in the Forendo deal, but later reported that “OG-6219 did not demonstrate improvement in moderate-to-severe endometriosis-related overall pelvic pain compared to placebo.” The conclusion was clear: “Based on these results, the company plans to discontinue the OG-6219 clinical development program.”

Still, even in a rough year, there were flashes of the underlying business doing what it was built to do. In the third quarter of 2025, the company reported: “Biosimilars revenue increased 19% on both an as-reported basis and ex-FX… primarily due to strong performance of Hadlima and the favorable timing of an international tender for Ontruzant.”

That’s Organon in independence in a nutshell: a company trying to build a focused future while managing the unforgiving realities of mature products, patent expirations, leverage—and, in 2025, a sudden test of trust.

VIII. Strategic Positioning & Competitive Landscape

The Women's Health Market Opportunity

By now, the macro case for women’s health isn’t subtle. It’s a giant market hiding in plain sight—and the underinvestment is so extreme it borders on irrational.

One analysis put the upside in sweeping economic terms: “Addressing this disparity could improve quality of life for women and unlock more than $1 trillion in annual global GDP by 2040 and create new market opportunities for conditions with significant unmet needs.” In other words: this isn’t just an ethical gap. It’s a commercial one.

And the funding gap is stark. “A mere one per cent of global R&D funding targets female-specific conditions (excluding female-specific cancers) and women's health research receives disproportionately less funding compared to conditions affecting men.”

You can see that imbalance show up in dealmaking, too. “A 2019 study found that, in the U.S. and Europe, there were 3,225 biopharma deals, with a total value of $122 billion. Only 60 of those deals… with a combined value of just $1.3 billion, were specific to women's health.” For a category that touches half the human population, that’s not a trend. It’s a void.

What makes this even more interesting is what the biggest incumbents did with that void: many stepped back. “At the same time, several life sciences companies have curtailed investments in the women's health market. Teva in 2017 and 2018 sold off its women's health business. That was followed by the spinoff of Organon from Merck in 2021. AbbVie and Bayer have also reportedly shifted funding away from research on women's health.”

Bayer was unusually direct about the pivot. “German pharmaceutical giant Bayer is no longer prioritizing R&D investments in women's health… The company said… it would focus instead on four core therapeutic areas: oncology, cardiovascular, neurology and rare diseases/immunology.”

So the paradox is real: massive unmet need, and a lot of the industry moving on. For Organon, that’s both opening and pressure. The bet is that focus can do what scale won’t—that a company built around women’s health can move faster, invest more consistently, and win mindshare in categories that get sidelined inside diversified pharma giants.

Biosimilars Competition

If women’s health is the identity story, biosimilars are the knife fight.

This market is crowded by design. Amgen, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Celltrion, and others are often chasing the same reference products at the same time. When multiple near-equivalents land, the product doesn’t “differentiate” its way to share. It contracts its way there. Price erosion can be fierce, and access is won through payer and pharmacy benefit manager negotiations that reward scale, leverage, and breadth.

That’s where Organon is structurally disadvantaged. It doesn’t have the sheer portfolio weight or commercial muscle of the biggest biosimilar players. Its biosimilar portfolio brings in roughly $500–600 million a year—real money, but not market-defining. Larger competitors can bundle more products, spread fixed manufacturing costs wider, and lean on deeper payer relationships.

The Debt Constraint

And then there’s the constraint that sits on top of everything: leverage.

As one summary put it, “It has $8.7 billion of debt versus a market cap of $5.4 billion. This is a significant debt load, but it is not unmanageable, and the company has been paying down debt since the 2021 spinoff.”

Another snapshot makes the same point in more balance-sheet language: “Organon has a total shareholder equity of $906.0M and total debt of $8.8B, which brings its debt-to-equity ratio to 974.4%.”

This is the practical limiter on Organon’s options. Big acquisitions get harder when they require more borrowing at higher rates. Dividend policy becomes a constant trade-off against deleveraging. And every dollar pointed at expanding R&D or doing deals is a dollar not going to interest expense and debt reduction.

So when you zoom out, Organon’s competitive landscape comes into focus: a huge, underfunded women’s health opportunity; a brutal biosimilars arena where scale matters; and a balance sheet that forces discipline. The question isn’t whether the strategy makes sense. It’s whether Organon can execute it fast enough—and cleanly enough—to earn the right to keep investing.

IX. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces Assessment

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate

Building a new drug the classic way still takes huge capital, deep regulatory expertise, and years of clinical work—high barriers that protect incumbents from true “new entrants.” But in women’s health, a different kind of entrant has started showing up: digital health and telehealth platforms that don’t invent new molecules, but do change how patients access existing ones. Companies like Nurx and Hers have built direct-to-consumer channels for contraception that can bypass the traditional physician-to-pharmacy path—and that matters for a portfolio like Organon’s.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low to Moderate

For many established medicines, active pharmaceutical ingredients are relatively commoditized. There are multiple capable manufacturers for a lot of molecules, which keeps supplier leverage in check. Biosimilars are the exception. Manufacturing is more complex, the qualified supplier base is smaller, and that gives suppliers more power in that part of the business.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: High

In the U.S., pricing power largely sits with payers and pharmacy benefit managers. The three largest PBMs control roughly 80% of prescription volume, which gives them real negotiating leverage—especially in categories where products are substitutable. In emerging markets, the power often shifts to government procurement and tender systems; the dynamic varies by country, but the theme is the same: large, consolidated buyers can force price and terms.

Threat of Substitutes: Moderate to High

In contraception, “substitutes” are everywhere: IUDs like Bayer’s Mirena and products like Paragard, condoms, and potentially future male contraceptives. In biosimilars, the substitute is often the reference biologic itself, with competition playing out mainly on price and access rather than clinical differentiation. And in established brands, substitution is direct and ruthless: generics.

Industry Rivalry: High

Women’s health is fragmented, with big players like Bayer, smaller biotechs, and generics competing across methods and indications. Biosimilars are even more combative: multiple competitors frequently target the same reference product, and when that happens, the market tends to clear on contracting power and price. Established brands, meanwhile, live in commoditized categories where differentiation is thin and erosion is constant.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Assessment

Scale Economies: Moderate

Organon benefits from a global manufacturing and distribution footprint, with facilities in six countries and reach into more than 140 markets. That scale helps on cost and logistics. But it’s not dominant scale—certainly not compared to giants like Pfizer, Roche, or Novartis—so the advantage is real but capped.

Network Effects: Low

Most pharma products don’t get stronger as more people use them. One patient choosing a contraceptive doesn’t meaningfully pull in other patients through a network dynamic. There may be early hints of network effects through digital health partnerships—where larger patient bases can attract more telehealth providers—but it’s still nascent.

Counter-Positioning: Low to Moderate

Organon’s focus on women’s health creates some counter-positioning because many large pharma companies have deprioritized the category. For a diversified giant, shifting resources back into women’s health could mean fighting internal capital allocation battles against flashier areas like oncology or immunology. Still, this isn’t a free moat: Organon can be outflanked by specialized entrants with novel mechanisms and cleaner growth stories.

Switching Costs: Moderate

Some of Organon’s core products do create friction. Nexplanon requires a clinical procedure for insertion and removal, which naturally raises switching costs. NuvaRing has a learning curve in proper use. But for many oral contraceptives—and for established brands facing generics—switching is easy and often driven by coverage and price.

Branding: Moderate to High

In contraception, brand still matters, and Organon owns meaningful equity here. NuvaRing and Nexplanon are recognized by providers and patients as trusted options. The corporate brand is a different story: after the 2021 rebirth, it’s still being rebuilt, and that takes sustained investment.

Cornered Resource: Low

The company doesn’t have many “you can’t copy this” assets left. Most key patents have expired or are nearing expiration. Organon generated USD 1.8 billion in women's health revenue during 2024, driven heavily by Nexplanon, yet faces patent expiration threats beginning in 2025 outside the U.S. The reality is that the most defensible resources here are commercial and operational, not legal exclusivity.

Process Power: Moderate

This is one of the quieter strengths. Decades of manufacturing quality, regulatory know-how, and operating experience across emerging markets add up to a real process advantage. Managing supply chains, registrations, and compliance across 140+ countries is institutional knowledge that’s hard to replicate quickly.

Overall Assessment: Organon has moderate power where it can lean on branding and switching costs—especially in parts of women’s health. It has weaker power in biosimilars and established brands, where competition is commoditized and scale tends to win. To build durable differentiation, Organon needs new sources of power: innovation, smart M&A, and geographic expansion that turns its global operating muscle into an advantage competitors can’t easily match.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case & Future Outlook

The Bull Case

Valuation Discount: Even after the stock’s early post-spin swings, the market has often priced Organon like a runoff book, not a company with levers to pull. As one commentator put it, “Even after this momentous run, it still trades at a ridiculously cheap valuation of just 4.7 times consensus 2024 earnings.” The underlying point is simpler than the multiple: if Organon stabilizes the base and proves it can grow women’s health, a re-rating alone could do a lot of work.

Women's Health Renaissance: The category winds are finally shifting. Women’s health is getting more attention from policymakers, founders, and investors—after decades of being treated like a niche. That matters when you’re one of the few scaled, global pure-plays. Or as one observer said, “Executives and investors are optimistic further investment in women's health could be forthcoming. 'It's about time and I think all the right pieces are in place.'” If capital and innovation really flow back into the space, Organon is positioned to be a primary beneficiary.

Emerging Markets Growth: Organon’s revenue base is unusually international—roughly three-quarters outside the U.S. That exposure comes with volatility, but it also creates a different growth profile: expanding middle classes, rising healthcare access, and, in many countries, less aggressive generic erosion than you see in the most price-optimized developed markets.

Deleveraging Path: The company’s best argument is that it can be a steady cash machine while it pays down the debt it was born with. Management has pointed to the combination of revenue durability and improving profitability: “In 2024, we achieved our third year of constant currency revenue growth and delivered adjusted EBITDA margin expansion.” If that holds, debt can come down year after year—and as leverage declines, Organon gets more room to invest, acquire, and return cash.

Nexplanon Momentum: Nexplanon is the clearest proof point that this isn’t just a melting ice cube. Organon has said the implant “showed strong growth, expected to exceed $1 billion in 2025.” In a world where many pharma products are fighting erosion, a durable, growing contraceptive franchise is a real asset—and it anchors the entire women’s health thesis.

The Bear Case

Structural Decline Risk: The core fear is that Organon is, at its heart, a collection of mature products fighting gravity. One blunt summary captures the story: “Organon's revenue has been in decline since 2016. This has been stemming from a loss of patents that expire after a certain time period.” If the pipeline doesn’t thicken—and if acquisitions can’t offset erosion—decline can become the default mode.

Debt Overhang: The balance sheet is the weight in the backpack. “The $8.96 billion debt pile, exacerbated by the Dermavant acquisition, now looms large,” and critics point out that “OGN's debt is not well covered by operating cash flow (10.7%).” However you frame it, high leverage narrows options: it pushes cash toward interest and repayments, limits how aggressive Organon can be in M&A, and makes any operational stumble feel larger.

Pipeline Risk: Organon has already felt the pain here. The Forendo endometriosis program didn’t work out in Phase 2. As one report put it: “A drug candidate Organon hailed as perhaps its 'biggest potential opportunity' has flunked a phase 2 trial, prompting the company to end clinical development.” That failure reinforces the larger concern: with limited internal R&D depth, Organon relies on partnerships and M&A to replenish the pipeline—an approach that can be both expensive and uncertain.

Execution Uncertainty: The company doesn’t just have to execute operationally; it has to rebuild credibility. CEO turnover, audit findings tied to sales practices, and the dividend reset all hit investor trust. Even strong quarterly results can get discounted if the market believes the story is unstable.

Currency and Political Risk: The international footprint is a double-edged sword. When you generate most of your revenue outside the U.S., you inherit currency swings, tender timing, and geopolitical risks that domestic-focused competitors simply don’t have to absorb.

Key Performance Indicators to Watch

For investors tracking Organon's ongoing performance, two KPIs merit particular attention:

-

Nexplanon Revenue Growth (Constant Currency): Nexplanon is the highest-margin, fastest-growing product in the portfolio. Its trajectory is the cleanest read on the health of Organon’s women’s health franchise—and on whether the company’s “focus wins” strategy is actually working.

-

Net Leverage Ratio (Debt/EBITDA): In a leveraged spin-off, strategy is constrained by the capital structure. Deleveraging progress determines flexibility. Management has targeted reducing net leverage below 4.0x; steady movement toward that line is one of the most important signals that Organon is earning back room to maneuver.

XI. Playbook: Lessons for Founders, Operators & Investors

The Spin-Off Playbook

Organon is a clean case study in both the upside and the hidden landmines of corporate spin-offs. When a giant decides certain assets are “non-core,” a predictable set of forces kicks in:

Hidden value in neglected portfolios: Inside a mega-cap parent, plenty of good products get managed for cash, not momentum. Spin them out, put a dedicated team and real commercial focus behind them, and some can surprise on the upside. Nexplanon’s post-spin trajectory is the clearest example of what happens when a franchise stops competing internally for oxygen.

Capital structure determines strategic flexibility: Organon didn’t just inherit products and people—it inherited constraints. The roughly $9 billion of debt it took on at birth shaped every decision that followed: how aggressive it could be in M&A, how much it could invest in R&D, and even how it thought about returning cash to shareholders. If you’re designing or investing in a spin, this is the part that compounds.

"Born big" advantages and challenges: Launching with about 9,500 employees and roughly $6.5 billion in revenue gives you instant scale most companies will never touch. But it also means you’re not really a startup—you’re a large enterprise that’s expected to move like one. As Kevin Ali put it, “Spinning out and creating Organon and leading the first two years of its existence is like drinking from a fire hose.”

Focusing on Underserved Markets

"We feel that the world needs a company that is not watered down but focused on women's health and solving these needs."

Organon’s central strategic bet is simple: focus can be a weapon. And the company’s experience offers a few lessons that travel well beyond pharma:

Category focus can substitute for scale: Organon can’t outspend Pfizer or Novartis across the board. But it can try to win by choosing one arena—women’s health—and showing up there every day with more consistency than diversified giants that are juggling ten “priority” areas at once.

Underinvestment creates white space: Women’s health receives just 5% of global healthcare research and development funding despite serving half the population. That mismatch is exactly what opportunity often looks like in mature industries: not a brand-new market, but a massive one that everyone chronically underserves.

Niche focus requires execution excellence: The trade-off is that focus cuts both ways. When you don’t have a dozen growth engines, a single clinical miss can hit harder. The disappointment in the Forendo endometriosis program is the reminder: concentrated portfolios magnify both wins and setbacks.

The Generic/Biosimilar Threat

Every pharmaceutical company eventually runs into the same wall: patents expire, competitors arrive, and pricing power leaks away. Organon’s early years as a standalone company show the few levers you actually have:

Lifecycle management matters: You’re never fully “done” with a product. Formulation upgrades, delivery improvements, new indications, and geographic expansion are how you stretch a franchise’s useful life. The evolution from Implanon to Nexplanon, with added features, is what strong lifecycle management looks like.

Brand value persists beyond patent: Losing exclusivity doesn’t instantly erase trust. In many international markets, brand recognition can still support meaningful revenue even in the presence of generics. Organon’s Established Brands segment is built on exactly that reality.

OTC switches as strategic lifelines: The Opill over-the-counter approval—“the first daily oral contraceptive approved for use in the U.S. without a prescription”—shows how a regulatory shift can open a new market for an established category. That said, Opill is manufactured by Perrigo, not Organon.

XII. Epilogue: What the Future Holds

Organon’s story is still being written. A company that began in Oss in 1923—born from the unlikely pairing of hormone science and a slaughterhouse supply chain—spent decades getting bought, bundled, and absorbed by American pharma giants. Then, in 2021, it reappeared as something rare: an independent public company with real scale and a very specific mission.

The women’s health thesis remains as compelling as ever. As one industry view put it: “The biopharmaceutical industry has a clear opportunity to close the health gap by investing in women's health. Pharma companies can drive innovation for female-specific conditions such as endometriosis, improve outcomes and reduce risks for shared conditions such as heart disease, and tap into high-growth markets to accelerate near-term growth.” In other words, the demand signal is there. The question is whether Organon can translate that signal into durable products, durable growth, and durable trust.

Because the next chapter isn’t just about market opportunity. It’s about execution under pressure. Organon needs to stabilize leadership after the CEO transition, rebuild credibility after the sales-practice disclosures, keep grinding down the debt it was born with, and find new “shots on goal” after the Forendo endometriosis program fell short.

Meanwhile, the world around it keeps moving. Women’s health is attracting more attention, more capital, and more competition. As one summary described it, there’s “growing deal activity and investment momentum, as pharma and biotech companies recognize its market potential and clinical importance across menopause, reproductive health and chronic conditions,” alongside “expanding clinical development pipelines, with new non-hormonal and targeted therapies addressing previously overlooked conditions such as endometriosis, uterine fibroids and menopause-related symptoms.” That momentum is good news for the category—and a reminder that focus only matters if you can out-execute the field.

For long-term investors, that sets up a familiar tension: value versus growth. Today’s valuation bakes in skepticism that Organon can outrun the structural headwinds of generic erosion and leverage. If management delivers—steady constant-currency revenue growth, a clear deleveraging trajectory, and a pipeline that’s more than hope and press releases—there’s meaningful upside in a re-rating. If erosion accelerates, or the balance sheet tightens faster than the business can adapt, the downside remains real.

Zoom out, and the larger lesson is the one Organon has been teaching for a century: pharma runs on cycles. Breakthroughs mature into franchises. Franchises get commoditized. Big companies shed what no longer fits. And the “boring” assets—contraceptives, established brands, steady cash flows—can become either dead weight or the seed capital for a new strategy, depending on who owns them and how they’re run.

Organon sits right at that intersection. The science is still compelling. The economics are still unforgiving. And the outcome will come down to the hardest part of any spin-off story: proving that independence isn’t just a change in ticker—it’s a change in trajectory.

This analysis reflects publicly available information as of December 26, 2025. Material developments affecting Organon may have occurred after this date. Readers should conduct their own research and consult appropriate professionals before making investment decisions.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music