OFG Bancorp: The Story of Puerto Rico's Banking Survivor

I. Introduction: From Small-Town Savings and Loan to Island Champion

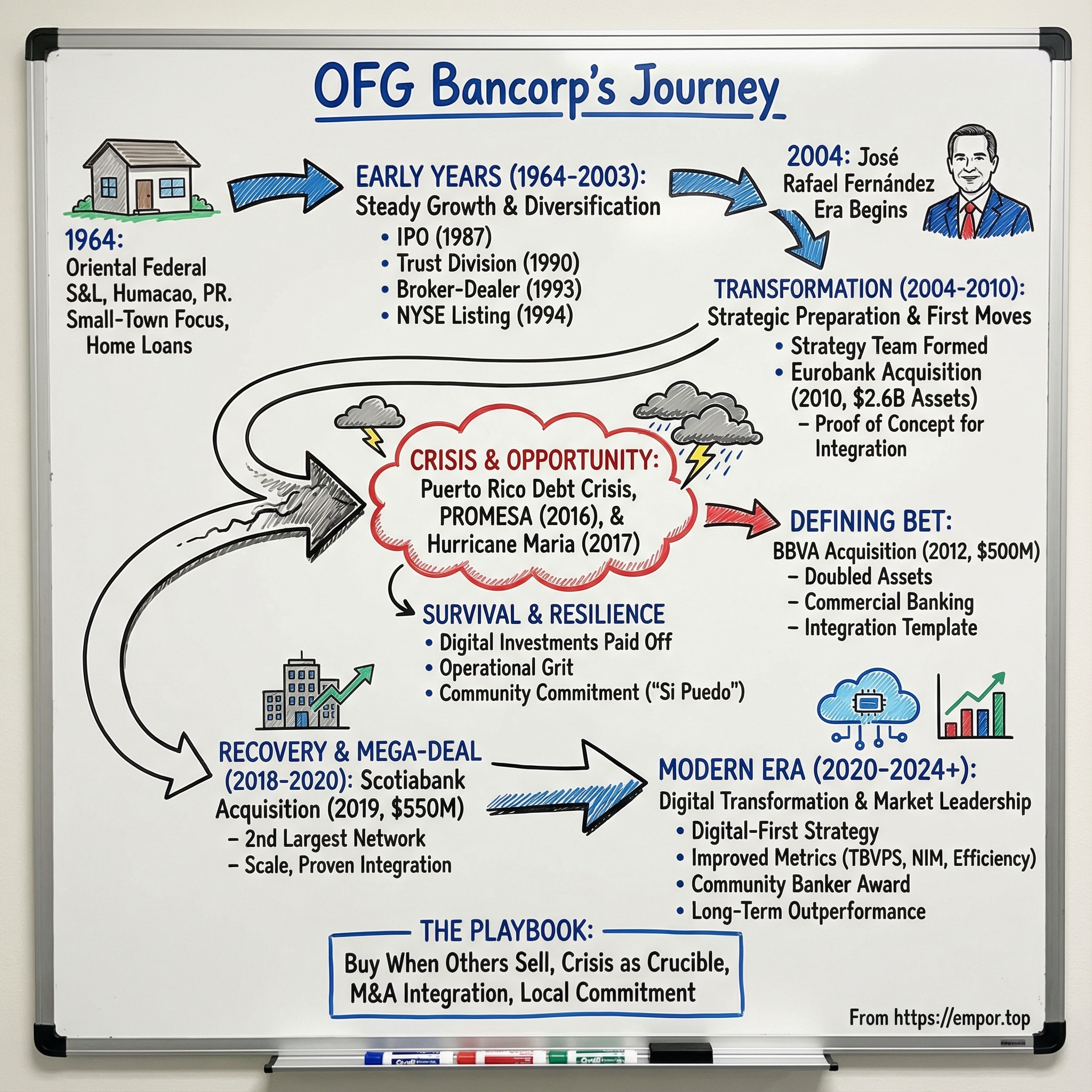

Picture Humacao on Puerto Rico’s eastern coast in 1964. The Vietnam War was escalating, the Beatles were taking over American radio, and a group of local entrepreneurs opened a modest savings and loan association with a straightforward purpose: help working families in the eastern municipalities buy homes and build savings. That institution—Oriental Federal Savings and Loan—would go on to become OFG Bancorp, the holding company for Oriental Bank, now headquartered in San Juan.

Today, OFG sits in a very different weight class. It manages $11.5 billion in assets and employs roughly 2,246 people. It went from a small player—ninth-largest on the island in 2004—to running the second-largest branch network in Puerto Rico. And it didn’t get there by slowly compounding deposits for six decades. It got there by making big, uncomfortable bets at exactly the moments most banks were looking for the exits.

That sets up the deceptively simple question at the heart of this story: how did a small-town savings and loan make it through Puerto Rico’s debt crisis, through the near-apocalyptic aftermath of Hurricane Maria, and come out the other side as one of the island’s most important financial institutions? The answer is part contrarian capital allocation, part operational grit, and part something that’s hard to put on a spreadsheet: deep local commitment in a market where global players could—and did—walk away.

CEO José Rafael Fernández captured the strategy in one line when the company announced its defining BBVA deal: “The combination will create a market leading bank that is strongly capitalized, locally controlled and totally focused on Puerto Rico.” That phrase—“locally controlled and totally focused on Puerto Rico”—wasn’t just PR. It became the operating system.

Three acquisitions mark the turning points. In 2010, OFG acquired Eurobank. In 2013, it bought BBVA’s Puerto Rico operations. In 2019, it acquired Scotiabank’s Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands operations. Each deal arrived in a moment of stress—the global financial aftermath, the European sovereign debt crisis, and Puerto Rico’s post-hurricane rebuilding years. And each time, OFG bought from sellers who needed to leave, not sellers who simply wanted a better price.

That’s the arc we’re going to follow: resilience through disaster, growth through acquisition, and the advantage that comes from commitment—especially when everyone else keeps an escape hatch.

II. Puerto Rico Context: The Indispensable Backdrop

To understand OFG, you have to understand Puerto Rico—because Puerto Rico doesn’t fit neatly into any American box. It’s a U.S. territory, so banks operate under U.S. federal regulation and the same core safety-and-soundness rules you’d see on the mainland. But the economy, the politics, and even the population trends behave very differently from any state. That tension—U.S. rules, island realities—sits underneath every decision OFG made.

Puerto Rico’s modern economic arc starts with Operation Bootstrap in the 1940s and 1950s: an aggressive push to industrialize and move the island from agriculture into manufacturing. And for much of the next half-century, the biggest tailwind wasn’t local policy—it was the U.S. tax code. Washington used incentives to pull U.S. corporations to the island, and the most influential of those incentives was Section 936, introduced in 1976, which let companies avoid federal tax on income earned in U.S. territories.

Section 936 turned Puerto Rico into a magnet for capital-intensive manufacturing, especially pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Pharma companies became the clearest winners, and the incentives were enormous. Factories, high-paying jobs, and tax revenues followed. For a while, it worked: Puerto Rico built a real manufacturing base, and a lot of the island’s middle-class growth rode on the back of that deal.

Then Congress changed the terms. In 1996, lawmakers voted to phase out Section 936, arguing it was too costly and too concentrated among a small number of large companies. The phase-out ran for a decade and fully ended in 2006. Suddenly, Puerto Rico-based subsidiaries were treated more like other offshore units for tax purposes—and many companies did what companies do when incentives disappear. They consolidated. They closed plants. They left.

The timing could hardly have been worse. Employment peaked around the eve of the Great Recession, and then Puerto Rico fell into something far more punishing than a normal downturn: a long, grinding contraction that began in 2006 and stretched for years. By the mid-2010s the island was stuck in a deep fiscal “death spiral,” and then, as if the macro picture weren’t brutal enough, Hurricanes Irma and Maria arrived in 2017 and turned a financial crisis into a humanitarian one.

By 2016, Puerto Rico’s finances hit a breaking point. The territory owed over $70 billion to bondholders and other creditors, and it didn’t have a workable legal path to restructure like a U.S. municipality. Congress responded with PROMESA—the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act—signed by President Barack Obama on June 30, 2016. PROMESA created the Financial Oversight and Management Board and gave it sweeping authority over the Commonwealth’s budget, with the goal of forcing fiscal discipline and enabling debt restructuring.

For banks, PROMESA was a double-edged sword. On paper, an orderly restructuring and budget oversight could stabilize the system. In practice, the medicine was austerity: pressure to raise revenues, cut services, and reduce pensions. That meant less money flowing through the economy, fewer government deposits, and a growing fear that the customer base itself was shrinking.

Because it was. Between 2010 and 2020, Puerto Rico lost over 400,000 residents to the mainland United States. For a bank, population decline is existential: fewer households, fewer small businesses, fewer mortgages, fewer deposits. But it also creates a strange kind of opportunity. When a market looks structurally harder, competitors with the option to exit often take it.

That’s exactly what happened across Puerto Rico’s banking landscape. Consolidation accelerated, and the competitive map simplified. Banco Popular—founded in 1893—remained the giant: the largest franchise, the largest network, the default institution for huge portions of the island. FirstBank, which traces its roots back to 1948, held another major position. And then there was OFG: the challenger brand, smaller than Popular, increasingly competitive with FirstBank, and steadily building relevance through a mix of local focus and well-timed acquisitions.

This is the backdrop that makes OFG’s strategy so striking. In a place defined by prolonged economic stress, fiscal oversight, and outward migration, most outside institutions looked at the same data and saw reasons to shrink or leave. OFG’s leadership looked at it and saw a different equation: if you’re locally controlled, committed to the island, and willing to invest when others can’t justify it, you don’t just survive the cycle—you can inherit the market.

III. The Early Years: From Humacao to San Juan (1964-2003)

Oriental was founded in Humacao in 1964—on Puerto Rico’s eastern coast, a world away from the marble lobbies and headquarters towers of San Juan. The mission was simple and local: serve working families who needed mortgages, auto loans, and a trustworthy place to keep their savings.

For years, the formula looked like a classic savings-and-loan story. Gather deposits. Make home loans. Grow steadily, branch by branch, year by year. But inside the institution, the ambition was already drifting beyond “local thrift.” Starting in the late 1980s, Oriental began quietly building the kind of toolkit you’d expect from a much larger financial company.

In 1987, it completed an initial public offering of common stock on NASDAQ. That did two things at once. It brought in capital, and it put Oriental under the bright lights of public-market expectations—quarterly scrutiny, performance pressure, and, crucially, a stock that could eventually function as acquisition currency.

Then came a run of strategic “firsts” that signaled where management wanted to take the company. In 1990, Oriental became the first local bank to have a trust division, accomplished through the acquisition of a subsidiary of Drexel Burnham Lambert Puerto Rico. It wasn’t just a new product line. It was a statement: Oriental wanted to compete for higher-value relationships, including clients with complex wealth and estate needs.

In 1993, it became the first bank in Puerto Rico to establish a broker-dealer, Oriental Financial Services. In 1994, its shares moved to the New York Stock Exchange—another step that widened its access to capital and credibility beyond the island.

By this point, Oriental had assembled a broader platform than you’d expect from a bank that started in Humacao: a broker-dealer, an insurance agency, and wealth management and trust capabilities. The diversification created additional revenue streams—useful in any environment, but especially valuable in a place where economic cycles could swing hard.

Still, by the early 2000s, Oriental’s footprint didn’t yet match its ambition. It had outgrown its origins, but it remained a relatively small player in Puerto Rico’s banking hierarchy, ranked ninth among the island’s financial institutions. To make the leap from “promising platform” to island-scale competitor, the next chapter would need a different kind of leader.

IV. The José Rafael Fernández Era Begins: Transformation to Full-Service Bank (2004-2010)

José Rafael Fernández didn’t set out to run a bank. After graduating from the University of Notre Dame in 1985, he thought he was headed for medical school. He took a job in a lab doing biochemistry experiments—measuring brain hormones in rats, trying to understand whether they connected to human intelligence. And then came the realization that changed everything.

“I hated it, and I’m not fond of rats,” Fernández later said. “That’s when I realized medicine wasn’t for me.”

His path into finance came through a coincidence and a conversation. At a Notre Dame alumni event, he met José Enrique Fernández, then the CEO of the investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert Puerto Rico. They shared a last name but weren’t related. Still, José Enrique saw promise in the young Notre Dame grad and opened the door to the financial world.

By 1991, José Rafael joined Oriental as an Assistant Vice President in the treasury department. A year later, he was put in charge of sales and marketing for Individual Retirement Accounts. It was a proving ground—and it helped propel Oriental into becoming a leader in Puerto Rico’s trust and retirement business. His rise inside the company kept accelerating: Vice President of Sales and Marketing for Oriental Financial Services, the broker-dealer subsidiary, in 1993; Senior Vice President four years later; Executive Vice President in 1999; and by 2001, President of Oriental Financial Services.

He’d already built a career that moved between Puerto Rico and the wider financial world. Before joining Oriental, he had served in Chase Manhattan Bank’s investment department in New York City and Buenos Aires. He’d started even earlier, in 1985, as an investment executive at Drexel Burnham Lambert.

Then, in late 2004, Oriental made the choice that would define its next era. On December 6, José Rafael Fernández was named President and CEO of Oriental Financial Group, effective January 1, 2005. José Enrique Fernández announced the decision plainly and confidently: “Jose Rafael is the ideal chief executive to lead Oriental… We have worked side by side at Oriental for more than a decade, building the Company from a small savings and loan institution on the eastern end of the Island into its present state as a fast-growing, $6.6 billion institution.”

By the time he took the top job, Fernández had effectively rotated through the company’s core businesses. And from that perch, he set out to do something bigger than manage a thrift. He aimed to build a full-service bank with the scale, capabilities, and discipline to compete on an island that was about to get much tougher.

The timing was both perfect and brutal. Puerto Rico’s long decline was beginning to harden into a reality, and the global financial crisis was only a few years away.

When 2008 hit, the stress rippled quickly across Puerto Rico’s banking system. Many of the island’s largest banks, including Banco Popular, lined up for assistance through the U.S. Treasury Department’s Troubled Asset Relief Program. Inside Oriental, Fernández was working a different angle. His view was simple: if the industry was about to consolidate, Oriental needed capital, stronger core capabilities, and a plan to move fast when opportunities appeared.

One of his smartest moves, he said later, was forming a small internal strategy team—four people including himself—focused on preparing for acquisitions as the crisis played out and the failure of three of Puerto Rico’s 10 largest banks reshaped the landscape. “We started to realize that there were more shoes to drop in the banking industry in Puerto Rico,” Fernández said, “and in order for us to be well-positioned, we had to be opportunistic and we had to be intentional.”

He also built the bench to execute. Fernández worked closely with Ganesh Kumar, the bank’s chief operating officer at the time and now OFG’s senior executive vice president of banking. And he made a key hire in Jose Ramon Gonzalez, a former president, CEO, and director at Banco Santander Puerto Rico, who joined as a senior vice president running the bank. (Gonzalez later became president and CEO of the Federal Home Loan Bank of New York.)

Then the first real opening arrived.

In 2010, Oriental acquired Eurobank, a $2.6 billion-asset institution, through an FDIC-assisted transaction that included a $1.6 billion loss-sharing agreement. The mechanics mattered: the deal gave Oriental an unusually attractive way to buy assets while sharing downside risk with the federal government. But the bigger win wasn’t just the balance sheet.

Eurobank was OFG’s proof of concept. It was the first time Fernández and his team had to absorb a complex bank, integrate systems and people, and hold onto customers—under real pressure, in a stressed economy. They did it successfully, and that experience became institutional muscle. The kind you only build by doing.

And it came at exactly the right moment. Puerto Rico’s economy was still deteriorating, which meant more exits were coming—and Oriental was now positioned to be the buyer, not the bystander.

Fernández would go on to become the longest-serving CEO among the three publicly traded Puerto Rico banks, and one of the longer-tenured leaders among banks listed on the NYSE. By now, he had been at OFG for 32 years, and next year he will mark his 20th anniversary as CEO. In a story defined by shocks—economic, political, and natural—that kind of continuity matters. It also says something about his defining trait as a leader: not just consistency, but the ability to adapt, keep moving, and keep buying when the moment calls for it.

V. The BBVA Acquisition: The Defining Bet (2012-2013)

In 2012, Spain was in crisis. The European sovereign debt emergency was hammering Spanish banks, forcing them to raise capital, simplify, and sell anything that wasn’t essential. For Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria—BBVA—one of the country’s biggest institutions, that meant looking across its global footprint and asking a blunt question: what helps us survive back home?

BBVA’s Puerto Rico business was meaningful, but it wasn’t core. And the island’s own worsening fiscal picture didn’t exactly make the case easier. So BBVA made a rational decision: exit Puerto Rico, send capital back to Madrid, and focus on the fight in Europe.

For José Rafael Fernández, BBVA’s retreat looked like a once-in-a-decade opening.

In late 2012, Oriental bought BBVA’s Puerto Rico operations for $500 million in cash. It was a gutsy move in a market most outsiders were learning to fear—and it was instantly transformative. The deal nearly doubled OFG’s assets to roughly $9 billion, added 36 branches, and brought in a deep bench of seasoned bankers—many of whom are still with the company.

It also came with real substance: about $3.7 billion in loans and $3.3 billion in deposits. Overnight, Oriental went from ambitious challenger to island-scale competitor. By December 2012, the combined franchise had the second-largest branch network in Puerto Rico, along with more than 90 ATMs and about 1,500 employees.

But the strategic value wasn’t just “bigger.” BBVA brought experienced commercial bankers, more sophisticated systems, and long-standing corporate relationships. Oriental—still carrying its roots in retail banking, trust, and wealth management—picked up capabilities that would have taken years to build the slow way.

Investment banker Frank Cicero summed up what this said about Fernández: “You can say José’s been lucky, but you create your own luck. The BBVA deal showed José’s ability to be flexible. They did all the blocking and tackling down there and then things fell their way and they were positioned to take advantage of it.”

Of course, buying a bank is the easy part. The hard part is making it one bank.

Integration meant stitching together two cultures, two technology stacks, and two different operating rhythms—without losing customers in the process. Fernández set an aggressive timeline: a 10-month systems conversion.

“Our goal was to seamlessly integrate both banks’ platforms, while maintaining the quality of service that our clients are accustomed to receiving from us,” Fernández said. “After 10 months of intensive planning, testing and standardization of processes and procedures, we have successfully completed the conversion.”

The speed mattered, and so did the outcome. After the conversion, Oriental’s loan book had jumped dramatically—more than tripling to $5.0 billion by June 30, 2013, from $1.6 billion a year earlier. It was a bigger version of a skill the team had already developed with Eurobank: absorb a complex institution, convert systems, keep the franchise intact, and move on stronger.

In 2013, the company also changed its name—from Oriental Financial Group to OFG Bancorp. It was a signal to the market and to itself: this was no longer a small eastern Puerto Rico thrift with a handful of “nice-to-have” businesses. It was a scaled, full-service bank with island-wide presence.

The BBVA deal became the template. Buy from sellers who need to exit, not those shopping for a premium. Step in during crisis, when pricing and terms make sense. Integrate quickly and completely. Put capital to work rather than waiting for perfect conditions that never arrive.

And the timing, in hindsight, was almost unnerving. Puerto Rico’s fiscal crisis only deepened. More international players headed for the door. But now the island had a clear, proven consolidator—locally controlled, integration-tested, and willing to bet on Puerto Rico when others couldn’t justify staying.

VI. The Perfect Storm: PROMESA and the Debt Crisis (2016-2017)

By 2015, Puerto Rico’s fiscal situation had gone from serious to existential. Governor Alejandro García Padilla declared the island’s debt “unpayable”—a rare moment of political candor that instantly rippled through municipal bond markets and made the crisis impossible to ignore.

The numbers behind that admission were staggering: more than $72 billion in debt and more than $55 billion in unfunded pension liabilities. But the real problem wasn’t just the size of the burden. It was that Puerto Rico didn’t have a workable way to renegotiate it.

Unlike U.S. cities, Puerto Rico couldn’t file for Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy. That quirk of territorial status left the Commonwealth trapped: creditors demanded payment, essential services were strained, and there was no clean legal mechanism to restructure obligations. Something had to give.

On June 30, 2016, President Barack Obama signed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management and Economic Stability Act—PROMESA. The law created a seven-member Financial Oversight and Management Board, with sweeping authority over the Commonwealth’s budget and the power to negotiate the debt restructuring. In Puerto Rico, it quickly got a simpler name: la junta.

For the island’s banks, PROMESA was immediate uncertainty made official. Austerity meant less government spending, and government spending had long been a major engine of economic activity. At the same time, population flight accelerated as Puerto Ricans looked to the mainland for stability and opportunity. Every bank faced the same ugly question: do you ride this out, or do you reduce exposure and look for an exit?

OFG went into the PROMESA era in a comparatively strong position—by design. As one analyst put it, “The combination of a very liquid bank with a prudent growth strategy and innovation has distinguished them from other banks. They also have little exposure to public corporations and the government, so that helps.”

That lower government exposure wasn’t an accident. While some Puerto Rican banks had loaded up on Commonwealth bonds—drawn by the triple tax-exempt appeal—OFG stayed disciplined. Risk management wasn’t a slogan; it was a prerequisite for being able to act when others couldn’t.

The strategic choice was clear, but not comfortable. Banks could pull back: tighten credit, close branches, and shrink alongside the economy. Or they could prepare to capitalize on the consolidation that crises always trigger. Fernández chose the latter.

As he explained, “OFG has been very focused on acquiring assets, growing its capital and its market share. Demographics are a challenge. There are fewer people and they are older, so the market needs to adjust. The consumers are not there. So, we need to look at the competitive landscape and adjust to that climate.”

It was a subtle, contrarian insight: yes, Puerto Rico’s economic pie was shrinking—but the number of banks fighting over it was shrinking faster. Every multinational that left didn’t just remove competition; it left behind customers, deposits, and relationships. If you were locally controlled and willing to stay, you could inherit share even in a contracting market.

And then, just as PROMESA began to reshape the island’s finances, Puerto Rico was about to be hit by a shock that would make the debt crisis feel almost abstract.

VII. Hurricane Maria: Banking in Apocalypse (September 2017)

Between September 19 and 21, 2017, Hurricane Maria tore through Puerto Rico and triggered a humanitarian crisis that swallowed the entire island. It was the strongest storm to hit Puerto Rico in nearly 90 years.

Maria had briefly reached Category 5 strength over the Atlantic before weakening slightly. By the time it made landfall on September 20, it was still a high-end Category 4—bringing a dangerous storm surge, torrential rain, and wind gusts well above 100 miles per hour. It flattened neighborhoods, shredded the power grid, and left an estimated 2,982 people dead, with damage pegged at roughly $90 billion.

For Puerto Rico’s banks, the days after landfall didn’t feel like a recession, or even a credit cycle. It felt like the rules of modern life had been unplugged.

By September 26, about 95% of the island was without power. Fewer than half of residents had tap water. And roughly 95% of the island had no cell phone service. Banking—an industry built on networks, connectivity, and trust—was suddenly being asked to function in a place where the networks were gone.

Branches began reopening where they could, but the system was running on partial capacity. More than half of FDIC-insured branches still hadn’t reopened. Popular, OFG Bancorp, First BanCorp, Banco Santander Puerto Rico, and Scotiabank de Puerto Rico collectively opened about 129 of 321 branches—often with limited hours, running on generators, and improvising day-to-day.

Fernández addressed what everyone could see: this wasn’t just a storm, it was a stress fracture in the island’s foundation.

“Hurricanes Irma and Maria devastated Puerto Rico and exposed the fragility of our infrastructure and economy,” he said. “Our deepest sympathy and concern goes out to everyone who has suffered. That includes our own staff and customers. We admire the resilience of all island residents in the face of extremely challenging recovery efforts.”

Then came the cash crisis.

With card networks unreliable and many electronic systems down, commerce snapped back to cash. That meant lines at branches and ATMs, and intense pressure on banks to physically supply currency. Puerto Rico’s financial commissioner described the scramble: “The New York Fed had already pre-positioned about $350 million here in Puerto Rico in the reserve. After the hurricane struck, they were able to get another $700 million in here within a week.”

Fernández saw what it looked like on the ground. In the early mornings after the hurricane, he visited branches before sunrise. One day he arrived around 4 a.m. to find a line of roughly 200 people already waiting for the doors to open. Another morning, he walked into a branch and saw something that captured the surreal intimacy of the moment: a teller blow-drying a customer’s hair.

“We had to send an email to all the employees saying, ‘Look, blow-drying hair in the branch can break the generator, so please be careful!’”

That’s what “banking” meant in Puerto Rico after Maria: people showing up in crisis, serving neighbors, and trying to keep a functioning economy alive with whatever tools were left.

And amid all of that, something quietly decisive happened. OFG’s digital bets—the ones that had seemed like modernizing investments in normal times—became a survival advantage.

“Due to our investments in technology, OFG’s digital channels, core banking and electronic funds transfer systems continued to function uninterrupted during and after the hurricanes.”

It wasn’t magic, and it wasn’t luck. It was preparation. OFG had invested in cloud-based systems and mobile capabilities because management understood a basic truth of operating on a Caribbean island: physical infrastructure fails. When the grid collapsed, the bank’s ability to keep core systems running mattered. For the customers who could get any connectivity at all, they could still check balances, move money, and manage essentials without stepping into a branch.

Financially, the quarter told the story of a franchise that took a hit—but didn’t break. OFG reported a net loss to shareholders of $146 thousand, or $0.00 per share, in Q3 2017, compared with a profit of $13.6 million, or $0.30 per share fully diluted, in the prior quarter.

Operationally, the footprint changed too. OFG ultimately closed about a dozen branches—roughly a quarter of its network—following Maria. Fernández said the storm “fit perfectly” into the bank’s digital strategy, not because it was welcome, but because it forced behavior change overnight.

“Maria hit and everybody had to close their branches,” he said. “There was no electricity, there was no communication, and we had to get branches up to speed as fast as we could.”

Hovering over every operational decision was the question no one could answer: how many customers would leave the island, and how many would ever come back? The migration trend that had already defined Puerto Rico’s 2010s accelerated after Maria. But OFG’s plan was never built on the island getting bigger. It was built on becoming more essential—capturing a larger share of whatever market remained.

“We are committed to doing everything we can to help our customers rebuild their personal lives and businesses,” Fernández said. “As we say, juntos lograremos más – together we will achieve more!”

Hurricane Maria tested OFG’s resilience in a way no stress test could simulate. The bank came out battered but operating—its digital backbone intact, its people battle-tested, and its commitment to Puerto Rico more visible than ever.

And as the island began the long, uneven work of rebuilding, the consolidation playbook that had worked before started to come back into view—because once again, someone was looking for the exits.

VIII. Recovery and The Scotiabank Mega-Deal (2018-2020)

The months after Hurricane Maria weren’t a clean rebound. They were a grind—power coming back in pockets, businesses reopening in waves, federal money moving slower than anyone wanted. But as Puerto Rico began to stitch itself together, something else happened in parallel: the market started to reprice the banks that had survived.

OFG was one of the clearest beneficiaries. By September 2019, its stock had delivered a total return of 132.10 percent since Maria, ranking first among the five companies in the Puerto Rico Stock Index.

Fernández credited that performance to a simple posture: adapt to the Puerto Rico that existed, not the Puerto Rico everyone wished for. “The island has to be rebuilt and is in the process of reconstruction,” he told the Weekly Journal. “The island needs to be resilient.”

That word—resilient—wasn’t just rhetoric. It was also a roadmap for what came next.

As the island stabilized, international banks took another look at their Caribbean footprints. For Canada’s Bank of Nova Scotia, better known as Scotiabank, Puerto Rico had been a long-running outpost—but not a core market. And when global banks simplify, they often sell good businesses for strategic reasons, not because the local franchise is broken.

In June 2019, OFG and Scotiabank announced a definitive agreement: Oriental Bank would acquire Scotiabank’s Puerto Rico operation for $550 million in cash, plus Scotiabank’s U.S. Virgin Islands branch operation for a $10 million deposit premium. The plan was straightforward—merge the Puerto Rico and USVI operations into Oriental Bank and its related businesses.

This wasn’t a small bolt-on. As of March 31, 2019, Scotiabank’s Puerto Rico and USVI operations included $2.5 billion in net loans, $3.2 billion in deposits, 21 branches, 225 ATMs, and approximately 1,000 employees.

Strategically, it was the same contrarian pattern OFG had already run—now at even larger scale. The deal expanded Oriental’s reach, brought in a seasoned team, and strengthened its position across the fundamentals that matter in a retail banking franchise: deposits, branches, ATMs, and mortgage servicing. The company described the result plainly: Oriental became the second largest in Puerto Rico in core deposits, branches, automated and interactive teller machines, and mortgage servicing.

And OFG didn’t have to stretch to do it. The transaction was funded with excess capital, and the pricing was conservative: 1.15x adjusted tangible book value for the Puerto Rico operation and a 2% deposit premium for the USVI branch operation.

This is where OFG’s reputation became a real asset. Scotiabank didn’t just need the highest bidder—it needed a buyer who could close, convert, and keep the franchise intact. OFG could point to two prior integrations that mattered in exactly this context: Eurobank in 2010 and BBVA’s Puerto Rico operations in 2012. By now, integration wasn’t an ambition. It was a demonstrated capability.

The company expected to close by December 31, 2019, and it did. “We ended 2019 on a high note, closing the Scotiabank acquisition at year-end as originally anticipated,” Fernández said.

The year-end financial snapshot reflected the new scale: book value of $18.75 per common share, up 4.8% from the prior year; tangible book value of $15.97 per common share, down 1.1% as a result of the acquisition; total stockholders’ equity of $1.05 billion, up 4.6%; and record total assets of $9.3 billion, up 40.9%.

Then, almost immediately, the world changed again.

Integration in 2020 meant integrating in a pandemic. COVID-19 forced customers into remote banking, disrupted business activity, and turned “business continuity” into an everyday requirement. Once again, OFG’s investments in digital capabilities paid off—not as a nice-to-have, but as the core way customers could bank. And once again, the company showed that crisis response wasn’t a one-time heroic effort after Maria. It had become part of the operating model.

Zooming out, the Scotiabank acquisition fit the larger story. The big deals—BBVA in 2012 and Scotiabank at the turn of 2020—weren’t just about getting bigger. They changed OFG’s standing on the island, deepened its operational scale, and expanded its footprint across Puerto Rico and into the USVI.

Most importantly, they proved the thesis Fernández had been executing for more than a decade: in a hard market where outside institutions keep pulling back, the bank that stays—and can integrate—doesn’t just survive. It accumulates.

IX. Modern Era: Digital Transformation and Market Leadership (2020-2024)

The Scotiabank integration marked the end of OFG’s acquisition-heavy sprint. But Fernández knew something important: being bigger didn’t automatically make you safer, faster, or more loved. Scale was table stakes. The next battleground was technology—because that’s where customer expectations were heading, and where a bank could either compound advantages or slowly leak relevance.

In many ways, Oriental had started placing that bet earlier than most people remember. Back in 2014, it became a pioneer in Puerto Rico’s online and mobile banking with FOTOdeposit and People Pay—mobile check deposit and peer-to-peer payments. Those features sound standard now. At the time, on the island, they were a meaningful leap.

Over the last decade, OFG’s sustained investment in digital platforms reshaped the way the bank operated. It made the organization more efficient, improved the customer experience, and helped Oriental compete not just with other banks, but with a new kind of threat: fintech products that can steal transactions without ever opening a branch.

Fernández pushed that “first-mover” posture across the franchise. Oriental expanded wealth management with a broader set of offerings—stock brokerage, trust, and insurance—and kept layering on digital capabilities like cardless cash, photo deposit, and P2P payments; mobile banking for consumers and businesses; online account opening and personal-loan applications; and video interactive teller machines.

The result was a customer base that increasingly banked without needing a teller window. By recent measures, 96% of routine retail customer transactions and 97% of retail deposit transactions were happening through digital and self-service channels, along with 68% of retail loan payments. Adoption was still growing, too—digital enrollment increased 12% year over year, and digital loan payments rose 21%.

That shift reinforced Oriental’s positioning as a challenger brand: win on experience. Not by trying to out-muscle the biggest incumbent on sheer footprint, but by pairing a real physical presence with digital convenience, faster service, and expert advice.

The financials reflected a bank that had found its post-acquisition rhythm. In 2023, OFG earned $160.7 million in net income while managing over $10.3 billion in assets, delivering a 1.61% return on average assets.

That same year, American Banker named José Rafael Fernández its Community Banker of the Year, citing his leadership in growing the company. Fernández pointed the recognition back to the organization, crediting the work of the Oriental team over the last 20 years.

The momentum continued into 2024. Full-year diluted EPS was $4.23, up from $3.83 in 2023, while total core revenues rose to $709.6 million from $682.7 million. Performance metrics for 2024 included a net interest margin of 5.40%, return on average assets of 1.75%, return on average tangible common stockholders’ equity of 16.71%, and an efficiency ratio of 54.82%.

Fernández framed it as execution plus strategy: “The fourth quarter and last year reflected solid performance with strong financial results. 4Q24 EPS-diluted increased 11.2% year-over-year on a 3.6% increase in total core revenues. 2024 EPS increased 10.4% year-over-year on a 3.9% increase in total core revenues. We demonstrated consistent and excellent operational execution on our plans, with our Digital First strategy helping to grow our banking franchise and market share.”

Zoom out further, and OFG’s long-term track record stood out even against mainland benchmarks. Since its NYSE listing on December 29, 1994, OFG Bancorp’s total return increased 2,522% versus 2,112% for the S&P 500, according to Bloomberg data as of October 2024.

And alongside the product and performance story, Oriental built something less measurable but just as powerful: cultural resonance. The “Si Puedo” (“Yes I Can”) brand campaign positioned the bank as an optimistic, can-do partner for Puerto Rican families and businesses—and it landed because it matched the island’s lived reality: rebuild, adapt, keep going.

Looking ahead, the constraints haven’t disappeared. Puerto Rico’s energy grid remains fragile. Population decline continues, even if the pace has slowed. Federal reconstruction funds have moved more slowly than many expected, but they still represent major potential stimulus. As Fernández put it, “the pending reconstruction funds, which have yet to be released by the federal government, are very important to boost the economy. We have an opportunity here to fix the patient once and for all.”

X. Playbook: Business & Strategic Lessons

The Contrarian Playbook

If you strip OFG’s rise down to its purest move, it’s this: buy when everyone else is trying to sell.

Eurobank in 2010. BBVA in 2012. Scotiabank in 2019. Three big acquisitions, all struck when Puerto Rico felt like a hard place to explain to a distant boardroom—and when sellers weren’t negotiating from a position of enthusiasm. They were negotiating from necessity.

That’s the opening OFG repeatedly stepped through. International banks, pressured by problems at home or simply rethinking where they wanted to be in the world, decided Puerto Rico wasn’t essential. But leaving isn’t as simple as putting up a “for sale” sign. In banking, you need a buyer that regulators will approve, customers will accept, and employees can follow. You need certainty of closing. And once the deal closes, you need someone who can actually make two banks operate as one.

OFG made itself that buyer.

Fernández started preparing early. After the 2008 financial crisis and the failure of three of Puerto Rico’s 10 largest banks, he put together a small internal strategy group to hunt for what might come next. “We started to realize that there were more shoes to drop in the banking industry in Puerto Rico,” he said, “and in order for us to be well-positioned, we had to be opportunistic and we had to be intentional.”

The takeaway isn’t “do M&A.” It’s that, in banking, the biggest opportunities often show up wearing distress. The winners aren’t the ones who notice first—they’re the ones who are ready first: capital in place, integration muscle built, relationships warm, and a reputation for getting deals done.

Crisis as Crucible

Hurricane Maria didn’t just test OFG’s balance sheet. It tested whether the bank could function at all.

This is where the unglamorous work of preparation paid off. OFG’s digital infrastructure—built before the crisis—kept core systems running even as the island’s physical infrastructure failed. In normal times, those investments looked like modernization. In September 2017, they were survival gear.

Fernández later said the hurricane “fit perfectly” into the bank’s digital strategy, because it forced adoption overnight. Customers didn’t gradually migrate to digital channels. They had to. And OFG was one of the banks positioned to meet them there.

The lesson here is broader than technology. Resilience is expensive before it’s necessary. Capital buffers, redundancy, continuity planning—none of it feels urgent when the lights are on. Then the lights go out, and it becomes the whole game.

M&A Integration as Core Competency

Plenty of banks can buy. Far fewer can integrate—reliably, repeatedly, and at increasing scale.

OFG did three major acquisitions in a decade, each bigger than the last. And with each one, it built something that compounds: institutional knowledge. How to convert systems without breaking customer trust. How to retain key employees. How to standardize processes fast enough to realize benefits, but carefully enough to avoid chaos.

That track record became a strategic asset in its own right. When Scotiabank decided to exit, OFG wasn’t just a bidder with cash. It was a buyer with credibility—someone the seller, regulators, and the market could believe would actually close and actually make it work.

Integration capability doesn’t appear fully formed. It’s learned. Eurobank was the proving ground. BBVA scaled the playbook. Scotiabank validated that OFG could run it again, under pressure, with even more on the line.

Commitment as Competitive Advantage

Fernández’s line from the BBVA announcement—“strongly capitalized, locally controlled and totally focused on Puerto Rico”—was more than a slogan. It described a structural advantage.

International banks in Puerto Rico always had an option: leave. That option can look like prudent risk management, but it also changes incentives. If a market gets harder, the path of least resistance is to shrink, sell, and redeploy capital somewhere calmer.

OFG didn’t have that mindset. It was built for the island because it was of the island. And that “nowhere else to go” posture, paradoxically, made it stronger. Employees could believe the company wouldn’t abandon them. Customers could trust the franchise would still be there. Regulators could see a long-term partner.

When you can’t exit, you optimize differently. You invest through cycles. You get good at operating in imperfect conditions. And when competitors with more choices decide they’ve had enough, you’re the one left standing—with the opportunity to inherit what they leave behind.

XI. Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Banking is a tough business to enter anywhere. In Puerto Rico, it’s even tougher. A new bank needs approvals from multiple regulators—the Federal Reserve, the FDIC, and Puerto Rico’s Commissioner of Financial Institutions—along with serious capital and the patience to operate under PROMESA-era complexity. And even if you clear every regulatory hurdle, you still run into the real barrier: this is a relationship market. Local knowledge and trust take years to build, and you can’t import them overnight.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Depositors): LOW-MODERATE

Depositors always have choices in theory. In practice, consolidation has narrowed the field, and OFG’s large physical footprint gives it a built-in advantage. Convenience matters, and in Puerto Rico, trust and presence often matter more than chasing the best rate. The result is that core deposits tend to be sticky—customers don’t move their primary bank relationship lightly.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Borrowers): MODERATE

Borrowers have some leverage, but it depends on who they are. Larger commercial clients can negotiate, yet they still need lenders who understand the island’s economy and can make decisions locally. Retail borrowers have fewer real alternatives, and even wealth management clients—who can technically move anywhere—often stay because relationships and local expertise carry real value. OFG’s network reinforces inertia: switching banks is possible, but rarely painless.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH

Fintech is a credible substitute, but it’s a slower burn in Puerto Rico than on the mainland. Remote-first U.S. banks can pick off certain segments, too. Still, OFG has structural defenses that matter here: Spanish-language service, cultural familiarity, and a physical presence customers can rely on. And ironically, disasters strengthen the case for the hybrid model. When life gets disrupted, people want both digital access and somewhere real to go.

Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE (declining)

This is a competitive market—but it’s becoming less crowded. Over the last decade, Puerto Rico’s banking industry consolidated dramatically, with Scotiabank and Banco Santander joining a longer list of banks whose operations were absorbed by others.

That leaves a clearer hierarchy. Banco Popular is the dominant incumbent. FirstBank is the strong number two. OFG plays the challenger role, growing through both execution and acquisition. Smaller banks exist, but each controls less than 10% of deposits—enough to keep the market honest, not enough to reset the competitive order.

Overall Porter Assessment: Puerto Rico banking is moderately attractive in a difficult geography. Entry barriers are high, and consolidation has reduced rivalry. The real separator isn’t clever pricing—it’s survival through macro shocks. The banks that make it through inherit what the others leave behind.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies: MODERATE-STRONG

After Scotiabank, OFG became the second-largest branch network in Puerto Rico. That scale matters because banking is loaded with fixed costs: technology, compliance, risk, and operations. As those costs spread over a bigger base, efficiency improves—reflected in an efficiency ratio around the high-50s in late 2024.

This is meaningful power in a small market. But it’s still relative. Popular remains larger, and in banking, the biggest player always gets advantages the number two can’t fully match.

2. Network Economies: WEAK-MODERATE

Traditional banking doesn’t have the kind of flywheel you see in social networks. Branch density helps, but it doesn’t compound exponentially. OFG’s digital capabilities may create some local “network-ish” benefits—especially with merchants and payments—and mortgage servicing scale brings incremental advantages. Still, this isn’t the core engine of OFG’s defensibility.

3. Counter-Positioning: MODERATE

OFG’s positioning is a tightrope, and it’s one it walks well: digital-first, but not digital-only. That creates a credible alternative to both the biggest incumbent and pure online challengers. As the company puts it, “As a challenger brand, Oriental differentiates itself through enhanced customer experience enabled by increased digital capabilities.”

Popular can’t easily adopt the same challenger posture without undermining its own positioning, while digital-only players can’t replicate OFG’s physical trust and reach. That “middle way” is harder to copy than it looks.

4. Switching Costs: MODERATE-STRONG

Banking relationships get sticky fast—especially in commercial banking. Mortgage servicing adds long-duration ties. A large branch footprint makes switching inconvenient. And in Puerto Rico, culture and language create softer switching costs that still matter a lot.

Add in the trust earned during Hurricane Maria, and you get something even stronger: customers remember who showed up when systems were failing. That kind of loyalty doesn’t show up neatly on a balance sheet, but it’s real.

5. Branding: STRONG

Oriental’s brand is deeply local—and it’s been stress-tested. “Si Puedo” resonates because it fits the island’s reality: rebuilding, adapting, pushing forward. The line “juntos lograremos más – together we will achieve more!” isn’t just a tagline; it matches how the bank has tried to behave.

In a place where international banks have repeatedly exited, the idea of banking with an institution that shares the island’s future becomes a competitive advantage. Sixty years of history helps, too—trust-based businesses compound trust over time.

6. Cornered Resource: WEAK

OFG doesn’t have a patented technology or a unique natural monopoly. Talent can leave. Customers can switch. Licenses matter, but competitors have them.

If there’s a near-cornered resource here, it’s leadership know-how: José Rafael Fernández’s multi-decade experience and the organization’s learned integration capability. That specific combination—built over 30+ years—can’t be bought quickly.

7. Process Power: STRONG

This is the big one. OFG has a proven, repeatable ability to acquire and integrate banks—successfully, multiple times, through very different crises. That’s rare.

Each integration created playbooks, muscle memory, and internal confidence. Each crisis forced improvements in continuity, technology, and operations. And the compounding effect is powerful: every acquisition made the next one easier; every shock navigated built capabilities for the next one.

Primary Power Sources:

1. Process Power (M&A integration capability)

2. Branding (local champion narrative)

3. Switching Costs (relationship banking + network)

4. Scale Economies (relative to market size)

Hamilton Assessment: OFG has built several reinforcing powers that fit its environment: scale in a protected market, a real integration advantage, and a brand rooted in local trust. The limitation is equally clear: these powers are concentrated in Puerto Rico and the USVI—an advantage in focus, and a constraint on growth.

Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case: - A rational oligopoly of two to three major players supports pricing discipline - Market share gains from acquisitions tend to stick—customers rarely change primary banks - Puerto Rico’s recovery, as federal reconstruction funds arrive, supports loan growth - Digital capabilities position OFG to defend against fintech and remote competitors - The Puerto Rico banking sector has shown strong profitability, helped by materially lower delinquencies across key portfolios

Bear Case: - Demographic decline continues, slowly shrinking the customer base over time - A fragile energy grid creates ongoing operational risk - Single-geography concentration limits long-term growth options - Credit metrics weakened in Q3 2025, including a higher net charge-off rate and non-performing loan rate, alongside a larger provision for credit losses—moves that triggered a negative market reaction - PROMESA oversight adds regulatory and political uncertainty

XII. Key Metrics for Ongoing Monitoring

If you want a simple dashboard for how OFG is really doing, there are three numbers that tell most of the story:

1. Tangible Book Value Per Share (TBVPS)

Over the last five years, OFG’s tangible book value per share has compounded at about 12% annually—and over the last two years, that pace has been even faster, at roughly 17% a year.

TBVPS matters because it ignores the accounting haze that acquisitions can create. When a bank buys other banks, it often books goodwill and other intangibles. Tangible book value strips those out and gets you closer to what’s actually there: concrete per-share net worth, and whether management is genuinely building value over time.

2. Efficiency Ratio

OFG’s efficiency ratio has hovered around 57% in recent periods, a sign of real operational leverage.

This metric is basically the bank’s “cost to produce a dollar of revenue”—non-interest expense as a percentage of revenue. Lower is better. And for OFG, the point isn’t just that the number is reasonable; it’s that the bank held onto efficiency even while absorbing large acquisitions. That’s the integration machine showing up in the financials.

3. Net Interest Margin (NIM)

In recent quarters, OFG posted a net interest margin of about 5.40%—the spread between what it earns on loans and securities and what it pays for deposits and other funding.

In a consolidated market like Puerto Rico, NIM is a quick read on discipline and competitive intensity. If that spread holds steady—or widens—it usually means pricing power is intact and deposit competition hasn’t turned into a race to the bottom.

XIII. Material Risks and Regulatory Considerations

For all the admiration OFG’s story earns, banking is still banking. And Puerto Rico is still Puerto Rico. A handful of risks sit underneath the narrative—and they’re worth taking seriously.

Several material risks warrant investor attention:

Geographic Concentration: OFG operates almost entirely in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. That focus has been a competitive advantage, but it also means there’s nowhere to hide. If the economy weakens, if regulation shifts, or if disaster strikes in the territories, OFG feels it directly. Diversification isn’t part of the model.

Hurricane Exposure: Puerto Rico’s geography makes major storms less a question of “if” and more a question of “when.” OFG has already shown it can operate through catastrophe, but every hurricane still brings two kinds of risk at once: the operational challenge of keeping the bank running and the credit challenge of customers suddenly under financial stress.

PROMESA Oversight: The Financial Oversight and Management Board still has real authority over Puerto Rico’s fiscal policy. Shifts in its priorities, tactics, or leadership can change the island’s economic backdrop quickly—especially when austerity and public spending flow through to household and business activity.

Demographic Decline: Puerto Rico’s population continues to shrink. OFG has offset that by taking share as competitors exited, but that’s not an infinite lever. Over time, fewer residents means fewer deposits, fewer loans, and a smaller base for growth.

Credit Quality: Credit is a moving target, and the story in 2025 began to show some strain. OFG’s total delinquency rate rose to 4.06% in Q3 2025 from 3.71% in Q2 2024. If that trend persists, it could mean more provisioning ahead—and less room for error.

Regulatory Scrutiny: Oriental Bank operated under a severe enforcement action starting in 2015 tied to allegations of Bank Secrecy Act violations. While it appears to have been resolved, the larger point remains: banking is heavily regulated, and the compliance bar is unforgiving—especially after you’ve been on regulators’ radar.

XIV. Conclusion: The Local Champion Model

OFG Bancorp’s story carries lessons that reach far beyond Caribbean banking. It’s proof that competitive advantage doesn’t always come from being everywhere. Sometimes it comes from being somewhere completely—building a business that’s designed for a specific place, with all its quirks, constraints, and cycles.

Oriental’s climb from the ninth-largest bank on the island to a franchise with the second-largest branch network didn’t happen by accident, and it didn’t happen by playing the “safe” game. It came from a clear, repeatable approach: find sellers who need to exit, keep capital ready for the moment that exit arrives, build real integration muscle by doing hard deals, and commit fully to Puerto Rico in a way outside banks rarely could.

Fernández put a human voice to that arc when reflecting on OFG’s 60th anniversary: “We are extremely proud of what we’ve accomplished since 1964 when we were one of the smallest banks in Puerto Rico. Since then, we have been able to reach new heights, becoming one of the top three banks on the island. This is a credit to our dedicated teams who work tirelessly to help fulfill our purpose of making progress possible for our customers, employees, shareholders and the communities we serve.”

The open question now isn’t whether OFG can point to a great past. It’s whether the model keeps working. Can OFG keep taking share in a market shaped by long-term demographic pressure? Do its digital investments translate into durable differentiation, not just nice features? And what happens when the island faces the next inevitable shock—another major storm, another macro downturn, another moment when operations get tested under stress?

So far, the pattern has held. OFG went through the debt crisis, Hurricane Maria, and the pandemic—and came out not just intact, but stronger. Each crisis hardened the organization, deepened the playbook, and made the “local champion” idea more real than any marketing line ever could.

But that last step belongs to the reader. The story of OFG Bancorp is, in the end, a story about betting on a place—and deciding that the risks are worth the commitment.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music