Intellia Therapeutics: Editing the Future of Medicine

I. Introduction: The Dawn of Programmable Medicine

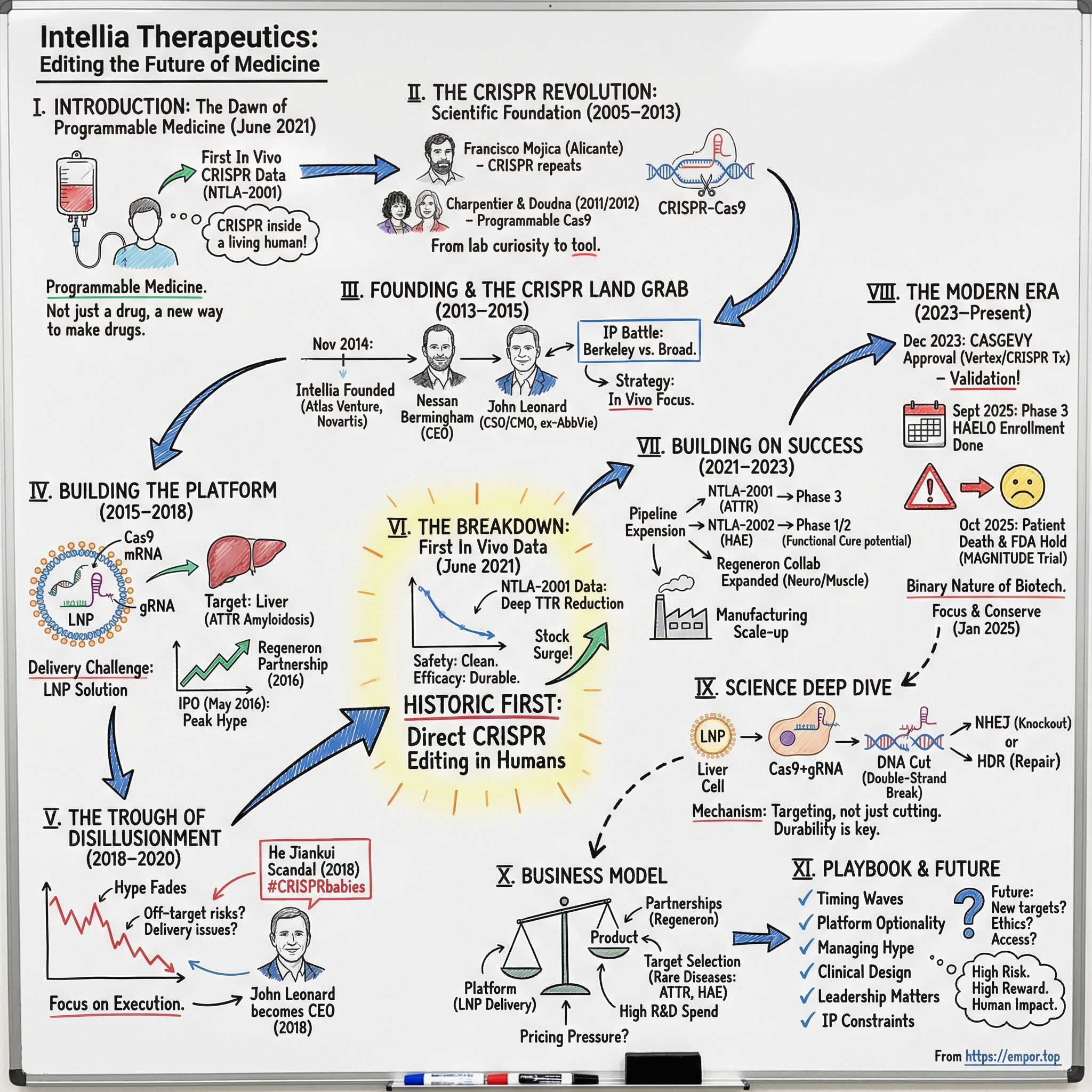

Picture June 2021. Inside a clinical research center in New Zealand, a patient with a rare, fatal genetic disease sits for an IV infusion that takes less than an hour. The fluid looks ordinary. What isn’t ordinary is what’s inside it: billions of lipid nanoparticles carrying a set of molecular instructions—CRISPR machinery designed to hunt down one specific gene inside the body and cut it.

For the first time, this wasn’t CRISPR in a petri dish. It was CRISPR at work inside a living human being.

That month, Intellia announced interim Phase 1 data for NTLA-2001. The takeaway was as stunning as it was simple: a single intravenous dose could precisely edit cells in the body to treat a genetic disease. And it marked a historic first—human clinical data for an in vivo CRISPR gene-editing therapy.

This is the story of Intellia Therapeutics. It began in November 2014 with $15 million and a radical idea: take the most powerful tool biology had produced and turn it into programmable medicine. Atlas Venture helped create and back the company, Novartis was an early supporter, and the founding leadership reflected the blend Intellia would bet on from day one—venture building plus serious drug-development experience. Nessan Bermingham, from Atlas, became the founding CEO. John Leonard, formerly AbbVie’s CSO, became the founding CSO.

The question that drives this story is straightforward, and it’s bigger than one company: How did a startup born in the white-hot hype of the CRISPR revolution become the first to successfully edit genes inside the human body—and what does that success, and everything that followed, tell us about where medicine is headed?

CRISPR’s real break from the past is programmability. Traditional drugs are molecules that bind to proteins and nudge them up or down. Pre-CRISPR gene therapy often meant inserting genes in ways that could be imprecise, even random, and hoping the biology cooperated. CRISPR is different: change the guide RNA sequence, and you can redirect the same core system to a new genetic target. That’s why CRISPR isn’t just a new kind of drug. It’s a new way to make drugs.

Today, Intellia is living at the edge of that promise. Its lead programs have reached Phase 3. Enrollment in the Phase 3 HAELO trial of lonvo-z for hereditary angioedema has been completed, with topline data expected by mid-2026 and a potential U.S. launch in the first half of 2027. But the reality of clinical-stage biotech is that progress and peril travel together. In October 2025, the FDA placed a clinical hold on Intellia’s flagship ATTR amyloidosis program after a patient death. The stock has swung from euphoria to despair—peaking above $200 in 2021, then falling below $10 in recent months. NTLA hit an all-time high of $202.73 on June 30, 2021, and later an all-time low of $5.90 on April 7, 2025.

This is what it looks like when a new medical paradigm is being born in real time: breathtaking potential, gut-wrenching setbacks, and a technology that—if it works—changes everything.

II. The CRISPR Revolution: Scientific Foundation (2005–2013)

Before we can understand Intellia, we need to understand the scientific earthquake that made it possible.

The CRISPR story doesn’t begin in a gleaming biotech lab. It begins in places that look like science has no business being—like the salty marshes of Santa Pola on Spain’s Mediterranean coast. There, microbiologist Francisco Mojica at the University of Alicante was studying bacteria that survive in harsh conditions when he noticed something odd in their DNA: the same short sequences repeated again and again, interrupted by “spacers” that didn’t repeat.

Those spacers turned out to be the tell.

Many matched the DNA of viruses that attack bacteria. Mojica realized the repeats and spacers weren’t random at all. They looked like a molecular scrapbook of past infections—an ancient immune system, written directly into the genome, that lets bacteria recognize and destroy invaders they’ve seen before.

Scientists had been glimpsing pieces of this puzzle for years. Short DNA repeats—what we now call CRISPR—were first noticed in bacterial genomes back in 1987, and later in archaea in 1995. By 2005, researchers proposed what Mojica was converging on: CRISPR loci help protect prokaryotes from foreign genetic material. Around this same period, the Cas9 protein was described for the first time—one of the key “weapons” the system uses to cut DNA.

Still, “bacteria have an immune system” is not the same thing as “humans can edit genes.”

That leap came from an unlikely scientific pairing.

Emmanuelle Charpentier, a French microbiologist working at Umeå University in Sweden, was studying Streptococcus pyogenes—one of the most medically important bacteria on Earth. In 2011, she published a discovery of a previously unknown RNA molecule called tracrRNA, and showed it was part of the CRISPR/Cas defense machinery that disarms viruses by cleaving their DNA.

Charpentier then teamed up with Jennifer Doudna, a biochemist with deep expertise in RNA. In 2011, they began collaborating to recreate the bacterial system in a test tube—and, crucially, simplify it. If CRISPR was going to become a tool, not just a curiosity, it needed to be something a lab could reliably program and run.

Their 2012 Science paper landed like a thunderclap. Doudna and Charpentier showed CRISPR-Cas9 could be guided to cut DNA at chosen sites—programmable genome editing. In the experiments, they picked a gene, selected multiple locations to cut, and programmed the system to hit those predetermined targets. It wasn’t just a new technique. It was a new interface for biology.

And the key idea was almost shockingly elegant: instead of redesigning a protein each time you wanted to target a new gene, you could redesign an RNA guide. Change the sequence of the guide RNA, and you change where the system goes.

That was the difference between CRISPR and the tools that came before it. Prior approaches—zinc finger nucleases and TALENs—could also cut DNA in specific places. But they required scientists to engineer new proteins for each new target, a slow and expensive process. CRISPR flipped the economics and the pace. To aim at a new gene, you didn’t need a months-long protein-engineering campaign. You needed a new short RNA sequence—something that could be synthesized quickly and cheaply.

In practical terms, it meant genome editing could go from a bespoke craft to something closer to software: design, synthesize, test, iterate. Faster, cheaper, and for many applications, more precise.

But just as the scientific community was absorbing what this meant, another battle kicked off—one that would shape the business of CRISPR for years. The University of California, Berkeley (associated with Doudna) and the Broad Institute at MIT and Harvard (associated with Feng Zhang) both claimed priority over foundational CRISPR inventions, especially around using CRISPR systems in eukaryotic cells like those of animals and humans. The dispute played out through the U.S. Patent Office and effectively split the emerging CRISPR world into distinct licensing camps—an invisible map that would later influence which startups could pursue which programs, and on what terms.

By 2020, the scientific impact was impossible to argue with. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry went to Charpentier and Doudna for the development of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing—less than a decade after their landmark paper, and less than a decade after the full system’s principal components had come into view.

But rewind to 2013 and 2014, and what investors and founders saw was even more intoxicating: a platform that could, at least in theory, go after the root cause of thousands of genetic diseases. The question stopped being “Will CRISPR be commercialized?” and became “Who’s going to build the company that turns this into medicine—and what’s the fastest path from a lab tool to something you can safely put into a human being?”

III. Founding & The CRISPR Land Grab (2013–2015)

By the fall of 2014, Atlas Venture was doing what it did best: not just funding startups, but manufacturing them. Atlas called it “venture creation”—spot the next platform shift, pull the pieces together, and build a company around it before the rest of the market fully catches up. Partner Jean-François Formela looked at CRISPR and saw the chance to create a defining genome-editing company, not a one-off drug shop.

Atlas didn’t do it alone. It co-founded Intellia with Caribou Biosciences, incubated the company from day one, co-led the Series A with Novartis, and tapped Atlas entrepreneur-in-residence Nessan Bermingham to become Intellia’s CEO.

From the start, the company’s strategy wasn’t just scientific—it was legal. CRISPR’s intellectual property was already turning into a battlefield, and you couldn’t build a platform company without a credible claim to the platform. Intellia in-licensed patents from Caribou, which in turn had licensed patents from the University of California tied to Jennifer Doudna’s work. Doudna had co-founded Caribou in 2011 to commercialize CRISPR, and Caribou provided Intellia an exclusive license to use its technology platform for discovering, developing, and commercializing human gene and cell therapies.

That licensing chain put Intellia squarely in the Berkeley camp of the CRISPR patent wars. It also meant the company was building on contested ground—an uncertainty the team knew could resurface at any time, with rulings that could move markets and reshape competitive positioning.

The founding roster reflected the moment: a deliberate blend of cutting-edge CRISPR science and people who knew what it takes to turn experiments into medicines. Intellia’s founders included Nessan Bermingham, Ph.D.; Rachel Haurwitz, Ph.D., CEO and co-founder of Caribou Biosciences; Andrew May, Ph.D., Caribou’s Chief Scientific Officer; Rodolphe Barrangou, Ph.D., an associate professor at North Carolina State University; Erik Sontheimer, Ph.D., a professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School; and Luciano Marraffini, Ph.D., an assistant professor at Rockefeller University.

But the hire that really signaled Intellia’s ambitions was John Leonard as Chief Medical Officer. Leonard had spent three decades in pharmaceutical R&D and had just retired in 2013 from his role as AbbVie’s Chief Scientific Officer and Senior Vice President of R&D. CRISPR pulled him back in. He’d helped develop landmark HIV protease inhibitors Norvir and Kaletra, led AbbVie’s HCV programs, laid the groundwork for its oncology efforts, and guided the development of HUMIRA, the world’s top-selling drug.

Leonard’s arrival was a statement: Intellia wasn’t trying to be the smartest lab on the block. It was trying to become a company that could survive the FDA.

All of this was happening during the CRISPR land grab—2013 to 2015, when the industry’s center of gravity was forming in real time. Three companies emerged as the early “founding triumvirate” in therapeutics: Intellia; CRISPR Therapeutics, co-founded by Emmanuelle Charpentier; and Editas Medicine, initially associated with Feng Zhang and the Broad Institute. In a sign of just how chaotic and personal the early days were, Doudna co-founded Editas in September 2013 alongside Zhang and others despite the simmering legal conflict, then left in June 2014. Charpentier invited her to join CRISPR Therapeutics, but Doudna declined after what she described as a “divorce”-like experience at Editas.

Inside Intellia, one strategic choice quickly rose above the rest: ex vivo or in vivo. Ex vivo therapies edit cells outside the body and then return them to the patient—powerful, but constrained to diseases where you can safely remove and reinfuse the right cells. In vivo therapies edit genes directly inside the patient. That approach is much more ambitious, but it opens the door to vastly more diseases—if you can make delivery work.

Intellia went further, describing longer-term development of in vivo applications administered systemically or locally to correct genes within specific cells of the body, including ophthalmic, central nervous system, muscle, liver, anti-infective, and other disease areas.

Then came the first real fuel. In November 2014, Intellia raised a $15 million Series A. “We believe the impact of this technology will be far-reaching, leading to new therapies for diseases that have been underserved with current therapeutic approaches,” Formela said.

In hindsight, that early commitment to in vivo wasn’t just a technical preference—it became Intellia’s identity. It was the bet that would later define the company’s edge, and eventually set up the “first” that made the world pay attention.

IV. Building the Platform: Technology & Strategy (2015–2018)

The years between Intellia’s founding and its eventual clinical breakthrough were the grind years—the unglamorous stretch where the company had to turn CRISPR from a breathtaking lab trick into something you could safely infuse into a living person.

The core problem sounded simple and was anything but: how do you get CRISPR machinery into the right cells, inside the human body, and have it do its job without causing collateral damage?

CRISPR-Cas9 needs two main ingredients. First, Cas9—the enzyme that cuts DNA. Second, a guide RNA—the “address label” that tells Cas9 exactly where to cut. Both are big, fragile, and electrically charged, which is biology’s way of saying: they don’t just slip through cell membranes. And even if you can get them into cells, you still have to solve the harder part—getting them into the right cells, at the right dose, while avoiding edits in the wrong places that could create serious safety risks.

What unlocked Intellia’s path wasn’t a new CRISPR enzyme. It was delivery.

The company leaned into lipid nanoparticles, or LNPs—tiny fat-like bubbles originally developed to deliver small interfering RNA (siRNA). LNPs offered an attractive nonviral approach: flexible, relatively low in immunogenicity, and potentially repeatable. Years later, the world would come to understand LNPs through the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, which used the same basic technology class to deliver mRNA. But in the middle of the 2010s, betting the company on LNP delivery still looked like a leap.

By 2016, Intellia had obtained a license for another company’s lipid nanoparticle drug delivery system as it worked to deliver CRISPR payloads to the liver without having them degraded in the bloodstream.

Then came the other critical decision: where to start.

Intellia’s target-selection philosophy followed the path of least resistance in biology. When you inject LNPs into the bloodstream, they tend to accumulate in the liver. Instead of treating that as a limitation, Intellia treated it as a starting advantage—build proof of concept in the organ your delivery system naturally prefers, then expand outward from there. Under a six-year agreement, Regeneron would hold the exclusive right to discover and develop CRISPR-based products against up to 10 targets, focused primarily on diseases that could be treated by editing genes in the liver.

For Intellia, the first major disease target was transthyretin amyloidosis, or ATTR amyloidosis: rare, progressive, and often fatal. In hereditary ATTR (ATTRv), mutations in the TTR gene cause the liver to produce an abnormal transthyretin protein that tends to misfold. Those misfolded proteins accumulate as amyloid throughout the body, damaging tissues including the heart, nerves, and digestive system.

ATTR was a near-perfect fit for what Intellia was trying to prove. The protein is produced in the liver, where LNPs naturally go. A knockdown strategy made sense—you want to stop production of the harmful protein, not necessarily repair the gene. And unlike a typical drug that requires chronic dosing, a successful gene edit could be a one-time intervention. Even better, Alnylam’s Onpattro had already established that knocking down TTR could benefit patients using siRNA, creating a meaningful precedent for regulators and clinicians.

Then, in April 2016, Intellia landed the kind of deal that changes how the world looks at a young platform company. Regeneron and Intellia announced a licensing and collaboration agreement to advance CRISPR/Cas gene editing for in vivo therapeutic development, including joint work on improving the platform itself. Intellia would receive $75 million upfront and could earn additional milestone payments and royalties on potential Regeneron products. ATTR amyloidosis became the first target the companies would jointly develop, and potentially commercialize.

This wasn’t just money. It was validation from one of biotech’s most respected R&D engines—an organization with deep genetics capabilities and the credibility to signal, to everyone else, that CRISPR wasn’t just science-fair magic.

And almost immediately after that validation, Intellia stepped onto the public markets. In May 2016, the company went public, pricing its IPO at $18.00 per share. Shares began trading on May 6, 2016, and Intellia took in roughly $112.9 million in net proceeds after underwriting discounts, commissions, and offering expenses.

The timing was electric. CRISPR was at peak hype, and the public market wanted in. But with an IPO came a new kind of pressure: the story had to graduate from promise to proof. Investors could buy the vision in 2016, but the world was going to demand human data. And getting there would take years—long enough to test not just the science, but everyone’s patience.

V. The Trough of Disillusionment (2018–2020)

Every technology hype cycle has a trough, and for CRISPR it hit in the late 2010s—hard. After the excitement around Intellia’s 2016 IPO, the story slowed down. Wall Street wanted a straight line from breakthrough science to blockbuster medicine. Drug development doesn’t work that way. Intellia’s stock slid for years as timelines stretched and the company kept spending heavily on R&D and manufacturing with no product revenue to show for it.

And Intellia wasn’t fighting just one battle.

Across the sector, uncomfortable questions piled up. Off-target editing—CRISPR cutting DNA where it wasn’t supposed to—became the headline risk. Delivery, the very thing Intellia was betting the company on, still looked like a narrow solution: the liver was one thing, but what about the rest of the body? Hanging over everything was the question skeptics loved to ask: is CRISPR a medical revolution, or just the world’s greatest lab tool?

Then the field took a reputational body blow.

In late November 2018, news broke that a Chinese scientist, He Jiankui, had used CRISPR to edit human embryos—and that those embryos had resulted in live births. The scientific community condemned the work immediately. Chinese authorities suspended his research activities within days, calling the work “extremely abominable in nature” and a violation of Chinese law. In December 2019, a court in Shenzhen found He guilty of illegal medical practice and sentenced him to three years in prison, along with a fine of 3 million yuan.

For companies like Intellia, it was a nightmare scenario: years of careful, regulated progress suddenly competing with a global “CRISPR babies” narrative. As UC Berkeley researcher Fyodor Urnov put it, “The field of gene editing will carry the hashtag #CRISPRbabies in the mind of the public for a period longer than He’s sentence…”

Inside Intellia, there was another kind of shift underway—one that mattered just as much as the headlines.

In January 2018, John Leonard took over as President and CEO, succeeding founding CEO Nessan Bermingham. Leonard had joined Intellia at the start as Chief Medical Officer, moved into the role of R&D chief, and now stepped into the top job. It was a signal that Intellia was moving from startup mode into clinical-stage execution mode—less about the promise of CRISPR, more about the grind of turning it into a regulated therapy.

By 2020, Intellia also doubled down on the partnership that had helped validate its platform early on. Regeneron and Intellia expanded their collaboration to include potential treatments for hemophilia A and B. Regeneron paid $70 million upfront and made a $30 million equity investment, reinforcing that—at least to one of biotech’s most respected operators—this still looked real.

And then, late in 2020, after six years of building, iterating, and waiting, Intellia reached the moment that mattered most.

NTLA-2001 became the first in vivo CRISPR medicine infused into a patient’s bloodstream.

The first patient had been dosed. Now the world was about to find out whether CRISPR could actually edit genes inside a living human.

VI. The Breakthrough: First In Vivo Data (2021)

June 2021 was when everything changed. At the Peripheral Nerve Society Annual Meeting, Intellia presented the first real proof point that its in vivo bet wasn’t just plausible—it worked.

The data came from Part 1 of a two-part, global Phase 1, open-label, multicenter study. Patients received a single IV dose of NTLA-2001 between November 2020 and April 2021, at either 0.1 mg/kg or 0.3 mg/kg of total RNA.

And the signal was unmistakable.

In the first 28 days after infusion, the safety picture looked clean: few adverse events, and those that showed up were generally mild. Then came the pharmacodynamics—the part everyone cared about. By day 28, Intellia reported a dose-dependent reduction in serum transthyretin (TTR) protein. The mean drop from baseline was 52% at 0.1 mg/kg and 87% at 0.3 mg/kg. Subsequent updates pointed to mean reductions in the same ballpark—roughly the high-80s to low-90s by day 28 across the two dose levels.

To understand why the field erupted, you have to compare it to what came before. The best available ATTR drugs—siRNA therapies and antisense oligonucleotides—work, but they demand chronic dosing: regular injections or infusions, month after month, year after year. They can drive TTR down dramatically, often around the 80–85% range with continued treatment. NTLA-2001 was hitting comparable reductions after a single infusion. And because it was designed to edit the gene itself, the promise wasn’t “keep taking this.” The promise was “edit once.”

It’s hard to overstate how much hung on the safety readout, too. In vivo gene editing had always carried a scarlet letter risk: what if you cut the wrong place, or trigger an immune reaction you can’t take back? In the first six patients, the therapy appeared to be tolerated with few side effects—an early but pivotal reassurance for the entire category. This wasn’t just a win for Intellia; it was the first clinical proof that CRISPR-based editing could be done directly in patients.

Markets moved like they understood that immediately. The stock surged. Days later, on July 2, Intellia did what biotech companies do when the window opens: it raised capital, announcing a new public offering that brought in $690 million.

The result wasn’t just a conference headline. The work was published in The New England Journal of Medicine, cementing NTLA-2001’s place as a historic first: direct CRISPR genome editing in humans to treat transthyretin amyloidosis.

Under the hood, the mechanism was almost beautifully straightforward. Intellia’s non-viral platform used lipid nanoparticles to deliver a two-part payload to the liver: a guide RNA programmed to target the TTR gene, and messenger RNA encoding the Cas9 enzyme. Liver cells took up the LNPs. The mRNA was translated into Cas9 protein. The guide RNA led Cas9 to the exact address in the genome. Cas9 cut the DNA. The cell repaired the break in a way that disrupted the TTR gene, shutting down production of the toxic protein—durably.

And on the question everyone feared most—off-target edits—Intellia reported that potential off-target sites identified through Cas-OFFinder, GUIDE-seq, and SITE-seq were in noncoding regions, and that there was no evidence of off-target editing in experiments treating primary human hepatocytes with high levels of NTLA-2001.

What this proved was the platform thesis in its purest form: CRISPR could work inside the body, not just in a dish. Solve delivery to the liver, and you don’t just get one program—you get a doorway into an entire class of diseases.

For investors and competitors, the strategic meaning was obvious. Intellia hadn’t just advanced a drug. It had shown that a new therapeutic modality—programmable, in vivo genome editing—was real.

VII. Building on Success: Pipeline Expansion (2021–2023)

Once Intellia had human proof that in vivo editing could work, the company did what platform companies are supposed to do: press the advantage. The strategy was clear—take the same liver-targeting LNP delivery system that powered NTLA-2001 and run the playbook again, disease by disease, gene by gene.

First, it pushed its flagship ATTR program toward late-stage development. NTLA-2001 moved into Phase 3 studies: MAGNITUDE, focused on transthyretin amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy, and MAGNITUDE-2, focused on ATTRv with polyneuropathy.

Then came the follow-on program that made the platform feel less like a one-hit wonder and more like a repeatable machine.

NTLA-2002 targeted hereditary angioedema (HAE), a rare genetic disorder marked by severe, unpredictable swelling attacks that can be debilitating—and in some cases, life-threatening. The biology was a clean fit for Intellia’s approach. NTLA-2002 was designed to knock out the KLKB1 gene in liver cells, lowering production of kallikrein. When kallikrein activity runs unchecked, it drives excess bradykinin, which in turn triggers those swelling attacks.

Like NTLA-2001, NTLA-2002 was built as a one-time, systemically administered therapy: a single IV infusion intended to edit a disease-driving gene inside the body. And under the hood, it used the same core delivery concept—Intellia’s non-viral platform, with lipid nanoparticles carrying a two-part genome-editing payload to the liver.

The early clinical signal was hard to ignore. Extended Phase 1 data supported the idea that NTLA-2002 could potentially be a functional cure for people living with HAE. Across all patients reported (n=10), a single dose led to a 95% mean reduction in the monthly HAE attack rate through the latest follow-up. In the study, single doses of 25 mg or 50 mg also reduced angioedema attacks and produced robust, sustained reductions in total plasma kallikrein levels.

While Intellia was building its wholly owned pipeline, it was also widening the circle around the platform. The Regeneron relationship—already a key source of validation—expanded again, with the two companies announcing plans to extend their in vivo CRISPR collaboration beyond liver diseases into neurological and muscular disorders.

At the same time, Intellia kept a foot in ex vivo editing through partnerships aimed at engineered cell therapies. It signed a license and collaboration agreement with AvenCell Therapeutics to develop allogeneic universal CAR-T therapies, and partnered with Kyverna Therapeutics to develop an allogeneic CD19 CAR-T therapy for various B cell-mediated autoimmune diseases.

All of this expansion raised a less glamorous but unavoidable question: could Intellia actually make these medicines at scale?

Manufacturing became a central priority. Gene-editing therapies don’t come off a standard pill press. Producing clinical-grade lipid nanoparticles, Cas9 mRNA, and guide RNA—reliably, repeatedly, and at commercial volumes—requires specialized processes, rigorous controls, and serious facilities. Intellia invested heavily here, knowing that clinical success would be meaningless without a supply chain that could support hundreds, and eventually thousands, of patients.

Regulators also began to treat NTLA-2002 as something worth fast-tracking. The program received five notable designations: Orphan Drug and RMAT from the U.S. FDA, an Innovation Passport from the U.K. MHRA, PRIME from the European Medicines Agency, and Orphan Drug Designation from the European Commission.

Behind the scenes, the organization stretched to match the ambition. Intellia grew from its early founding team into a company with hundreds of employees, adding the capabilities you need when you’re no longer just proving science—you’re building a pipeline, running global trials, scaling manufacturing, and preparing for the possibility of commercial launch.

VIII. The Modern Era: Platform Company Emergence (2023–Present)

From 2023 to the present, Intellia has been living through the phase that separates exciting science from enduring companies: late-stage execution. It’s been a stretch defined by real clinical momentum, a historic regulatory milestone for the broader CRISPR field, and then the kind of gut-check that reminds everyone why biotech is never a straight line.

In December 2023, the industry crossed a line people had been debating for a decade: CRISPR made it to an FDA approval. Vertex Pharmaceuticals and CRISPR Therapeutics announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration had approved CASGEVY™ (exagamglogene autotemcel [exa-cel]), a CRISPR/Cas9 genome-edited cell therapy for sickle cell disease (SCD) in patients 12 and older with recurrent vaso-occlusive crises (VOCs). For the first time, roughly 16,000 patients with SCD could be eligible for a durable, one-time treatment with the potential for a functional cure.

"CASGEVY's approval by the FDA is momentous: it is the first CRISPR-based gene-editing therapy to be approved in the U.S."

CASGEVY wasn’t Intellia’s style of medicine. It’s ex vivo—cells out, edited in a lab, and put back—rather than editing directly inside the body. But it mattered enormously for Intellia anyway. It proved regulators would approve CRISPR. It showed the modality could clear the bar on manufacturing, safety, and durability. And it put a price tag on the future: Vertex and CRISPR priced the one-time treatment at $2.2 million.

Inside Intellia, the engine kept turning. In its Phase 3 ATTR program, enrollment moved quickly—fast enough that management spoke publicly about pulling timelines forward. "The enthusiasm from both patients and physicians for Intellia's late-stage programs has resulted in strong enrollment numbers that allow us to plan to enhance the Phase 3 MAGNITUDE trial in ATTR-CM and accelerate completion of the Phase 3 HAELO study in HAE ahead of our original plans. We are full steam ahead in achieving our mission of getting one-time therapies to more patients."

And the HAE story—Intellia’s other flagship—kept getting stronger with time, which is what you want to see from a “one-and-done” therapy. The company released three-year follow-up from the Phase 1 portion of its ongoing Phase 1/2 study in hereditary angioedema after a single dose of lonvoguran ziclumeran (lonvo-z, also known as NTLA-2002). "Today's results underscore the promising potential of Intellia's approach to gene editing therapy—a one-time treatment that was well tolerated and offered a highly differentiated, durable effect for patients suffering from a serious disease," said Intellia President and Chief Executive Officer John Leonard, M.D. "Seeing all 10 patients in the Phase 1 portion of this study free from both HAE attacks and chronic therapy at nearly two years of median follow-up is incredibly encouraging."

In September 2025, Intellia completed enrollment in its global Phase 3 HAELO trial, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Then, in October 2025, the ATTR program hit the kind of moment that can redefine a company overnight. Intellia announced it had temporarily paused dosing and screening in MAGNITUDE and MAGNITUDE-2, its Phase 3 trials of nex-z in ATTR cardiomyopathy (ATTR-CM) and polyneuropathy (ATTR-PN). The pause followed a report, dated October 24, 2025, of Grade 4 liver transaminases and increased total bilirubin in a patient dosed in MAGNITUDE.

A few days later, Intellia shared worse news. "We were deeply saddened to learn that the patient who experienced Grade 4 liver transaminase elevations and increased total bilirubin following a dose of nex-z in the MAGNITUDE Phase 3 clinical trial, as reported on October 27, 2025, passed away last night," said Intellia President and Chief Executive Officer John Leonard, M.D.

The FDA placed a clinical hold on the Investigational New Drug applications for MAGNITUDE and MAGNITUDE-2. Two days after the pause, on October 29, the FDA verbally confirmed the holds and said a formal letter outlining next steps would follow within 30 days. More than 450 participants had received nex-z across the MAGNITUDE trials. This was one case among hundreds, but the protocol included pre-defined rules requiring a pause when specific safety thresholds were met.

It was a sharp illustration of the binary nature of clinical-stage biotech: years of careful progress can be forced to stop on a single severe safety event, especially in late-stage trials.

Financially, Intellia went into 2025 with meaningful resources. It ended 2024 with approximately $862 million in cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities. In 2024, Intellia Therapeutics's revenue was $57.88 million, up from $36.28 million the year before. Losses were $519.02 million, higher than 2023.

In January 2025, the company also made a classic “focus and conserve” move. After a strategic review, it chose to prioritize its late-stage programs—NTLA-2002 for HAE and nex-z for ATTR amyloidosis—plus select research investments aimed at near-term value creation. It discontinued NTLA-3001 and other undisclosed programs, and planned to reduce its workforce by roughly 27% in 2025.

All of this has played out against a tightening competitive backdrop. At the moment, Intellia is probably the better gene-editing stock. It's simply much closer to obtaining its first approval, which will be a major milestone, as well as a critical de-risking catalyst for shareholders. The fact that it might be able to price its candidate to steal market share from the existing therapies is also a major plus.

IX. The Science Deep Dive: How CRISPR Medicine Actually Works

To really understand Intellia’s business, you have to picture what’s happening inside those lipid nanoparticles. “Molecular scissors” is the popular shorthand for CRISPR-Cas9, but the interesting part isn’t the cutting. It’s the targeting. This is cutting with an address label.

Cas9 is an endonuclease—an enzyme that can cut DNA. What makes it different is that it doesn’t decide where to cut on its own. It’s directed by a short piece of RNA called a guide RNA, or gRNA. That guide is the program. Swap the guide sequence, and you can redirect the same Cas9 machinery to a completely different gene.

In Intellia’s approach, the lipid nanoparticle delivers two main payloads into liver cells: messenger RNA that encodes Cas9, and the guide RNA that tells Cas9 where to go. Once inside the cell, the mRNA is translated by the cell’s ribosomes into Cas9 protein. Cas9 then pairs up with the guide RNA and begins the search—moving through the genome until it finds the matching DNA sequence.

When it finds the match, Cas9 makes a double-strand break: a clean cut through both strands of the DNA helix. That’s a big deal biologically. A double-strand break is one of the most serious forms of DNA damage a cell can face, so cells have evolved multiple repair pathways to fix it. Which repair pathway wins determines what kind of edit you end up with:

-

Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ): The cell reconnects the broken DNA ends, but it’s often sloppy. It can introduce small insertions or deletions—“indels”—that disrupt the gene. This is the workhorse mechanism for making a “knockout.”

-

Homology-directed repair (HDR): If a DNA template is present, the cell can use it to repair the break precisely, which can enable gene correction or insertion of new DNA.

Intellia’s lead programs have leaned on the first pathway—knockout. For ATTR, the goal is to disrupt the TTR gene so the liver stops producing the problematic transthyretin protein. For HAE, the goal is to disrupt KLKB1 so the liver produces less kallikrein.

The nanoparticle isn’t just a delivery vehicle, either. The lipid coating helps protect the RNA payload from degradation in the bloodstream—shielding it from enzymes like RNases—and helps the cargo get into cells in the first place.

So why use lipid nanoparticles at all? LNPs have become a compelling nonviral delivery option because they can carry nucleic acids without using viral vectors like AAV. They don’t integrate into the genome, they generally avoid the same kind of long-lived immune barriers that can complicate viral delivery, and—crucially for a platform—there’s a path to repeat dosing in some settings.

"For the first time ever, we demonstrated that redosing with CRISPR, utilizing our proprietary, non-viral LNP-based delivery platform, enabled an additive pharmacodynamic effect on the target protein," said Intellia President and Chief Executive Officer John Leonard, M.D.

Then there’s the question that sits underneath every promise of “one-and-done” medicine: durability.

Intellia has continued to report extended follow-up from patients treated with NTLA-2001 across multiple single-ascending dose cohorts. In the most recent data described here, follow-up reached as long as 12 months, and patients showed sustained reductions in TTR protein.

In theory, the durability logic is simple: CRISPR edits the genome itself, not just the RNA or the protein. If you successfully edit a cell’s DNA, that edit should persist for as long as that cell survives. Hepatocytes—the liver cells Intellia targets—are long-lived, even if they slowly turn over. But “in theory” isn’t enough in medicine. The field will need long-term follow-up measured in years to understand how durable these effects truly are.

And even with targeting and durability, safety remains the governing constraint. Off-target editing is only one risk category. Immune responses to the LNPs, to the Cas9 protein, or to edited cells are also important. And Intellia’s own story makes the broader point: the liver toxicity event that triggered the MAGNITUDE trial pause showed how, in larger patient populations, even a platform that looks well understood can still produce severe, unexpected outcomes.

X. Business Model & Strategic Positioning

Intellia has always tried to be two things at once: a platform company and a product company. That choice—build the engine and also drive the car—shows up everywhere, from how it spends R&D dollars to how it structures partnerships and how much control it keeps over its most important programs.

The platform thesis is simple, and it’s the reason Intellia exists in the first place. If you can reliably deliver CRISPR to the liver with lipid nanoparticles, then the hard part is largely reusable. You don’t have to reinvent delivery each time you pick a new disease. In theory, you just swap the guide RNA, point Cas9 at a new gene, and run the same playbook again. That’s what “programmable medicine” looks like in business terms: one delivery system, many shots on goal, with each new program benefiting from everything learned before it.

Partnerships are where that platform value gets monetized and de-risked. The Regeneron deal that helped validate Intellia early came with $75 million upfront, plus additional milestones and royalties (not disclosed) tied to up to 10 targets. In 2020, the companies revised the agreement, adding another $70 million upfront and a $30 million equity investment from Regeneron.

Those collaborations do three jobs at once. They provide non-dilutive capital, they share scientific and clinical risk, and they act as a credibility stamp from a top-tier biotech operator. But Intellia has also been intentional about what it keeps. It retained full ownership of NTLA-2002, and it has positioned its most advanced efforts so it can capture the upside if the platform becomes a real commercial franchise. NTLA-2001 has been co-developed with Regeneron, but Intellia has planned to commercialize it.

The choice of early indications follows the classic biotech pattern: start where the path is clearest. Rare diseases have more definable patient populations, more straightforward trial designs, and a reimbursement world that’s already accustomed to premium-priced therapies when the benefit is dramatic. Hereditary angioedema is one of those diseases—estimated at about one in 50,000 people—and both HAE and ATTR come with severe unmet need and an existing precedent for expensive chronic therapies.

None of this is cheap, and Intellia has spent accordingly. R&D has been the center of gravity. In the third quarter of 2024, research and development expense was $123.4 million, up from $113.7 million in the third quarter of 2023, primarily driven by advancing the lead programs.

As the pipeline has moved closer to potential approvals, the business starts to look less like a research project and more like a launch organization. Intellia has said it plans to submit a Biologics License Application in the second half of 2026 to support a U.S. launch in 2027, and it has indicated it intends to commercialize its lead products directly in the U.S., while potentially partnering outside the U.S.

Then there’s the question that hangs over the entire gene-editing category: price. One-time genetic medicines have already set expectations north of $2 million per patient—Vertex and CRISPR Therapeutics priced CASGEVY at $2.2 million. A one-and-done therapy for ATTR or HAE could land in that neighborhood too, but the real number will be shaped by payers, competitive alternatives, and the growing scrutiny around how health systems absorb “curative” costs upfront.

XI. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Intellia’s story is a case study in what it takes to commercialize deep tech—where the breakthrough is real, but the path to a product is long, capital-intensive, and full of ways to fail.

Timing technology waves: The CRISPR pioneers understood that the 2012 breakthrough opened a window—but not a permanent one. Move too early, and you’re building on science that can’t yet survive the clinic. Move too late, and the best targets, partners, and IP positions are already spoken for. Intellia was founded in 2014—two years after the seminal Science paper, and years before anyone had proven in vivo editing in humans—which gave it time to build the machine while the science caught up.

Platform thinking creates optionality: Intellia didn’t build a company around “an ATTR drug.” It built around a repeatable way to deliver CRISPR payloads in vivo—starting with LNP delivery to the liver. That decision created real optionality. Once NTLA-2001 showed the approach could work, NTLA-2002 could follow the same core delivery paradigm into a different disease, faster and with less technical reinvention.

Managing hype cycles is essential: CRISPR’s public narrative has been a whiplash machine—from Nobel-level celebration to the He Jiankui scandal in just a few years. In markets, that kind of volatility is brutal. Intellia’s stock hit an all-time high of $202.73 on June 30, 2021. Anyone who bought at the peak of “this changes everything” learned the hard truth of biotech: validation moments are real, but so are multi-year drawdowns when timelines slip or safety questions emerge.

Clinical trial design as competitive advantage: Intellia’s early success wasn’t just about the molecule—it was about picking an indication where the signal would be clean. Starting with TTR knockdown gave the company an endpoint that was both biologically direct and easy to interpret. A big drop in TTR is a number that clinicians, regulators, and investors can grasp instantly—and compare to existing therapies—which helped turn early data into real conviction.

Leadership matters enormously: Intellia’s handoff from founding CEO Nessan Bermingham to John Leonard wasn’t just a change in title. It marked the shift from formation to execution. Leonard brought the muscle memory of late-stage pharma—someone who had lived through the reality of getting major drugs developed and through regulators. In a modality as new as in vivo gene editing, that credibility isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s part of the risk management.

The patent landscape creates structural constraints: CRISPR isn’t just a scientific race; it’s an IP maze. Companies aligned with Berkeley/UC versus Broad/MIT have operated under different rights, risks, and negotiation leverage from day one. The 2022 patent ruling against the Berkeley camp rippled through stock prices and the perceived durability of competitive positioning. For investors, this is a reminder that in frontier biotech, your moat isn’t only in the lab—it can live, or die, in courtrooms and licensing agreements.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces

Competitive Rivalry (Medium-High): CRISPR therapeutics is crowded with well-funded rivals—CRISPR Therapeutics, Editas, Beam, Verve, and others—each pursuing different editors, delivery approaches, and disease targets. Editas has generally been viewed as behind the leaders. CRISPR Therapeutics, with Vertex, got the first CRISPR-based medicine approved. Intellia was the first to show CRISPR editing could happen inside the human body. Today, the market is partially segmented—ex vivo versus in vivo—so not everyone is fighting over the exact same patients. But as delivery improves and modalities blur, those lanes could start to merge.

Threat of New Entrants (Medium): The barriers are real: elite science, specialized manufacturing, long timelines, and massive capital needs. Still, the field keeps getting refreshed by academic breakthroughs and newer modalities like base editing and prime editing. That steady flow of innovation means disruption can come from the outside, not just from the current public-company cohort.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low-Medium): These therapies depend on specialized inputs—LNP components, mRNA and guide RNA production, and GMP capacity. But COVID-era scale-up dramatically expanded the ecosystem around nucleic acid manufacturing and lipid supply, which reduced dependence on any single supplier and made the supply chain less fragile than it looked pre-2020.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (High): If you’re selling a rare-disease therapy with a one-time price tag in the millions, you’re negotiating with buyers that have leverage: insurers, national health systems, and large hospital networks. They decide access, coverage rules, and how much “curative” benefit is worth upfront. Gene therapy pricing has already attracted scrutiny, and the pushback tends to increase as the number of eligible patients grows.

Threat of Substitutes (Medium-High): In diseases like ATTR and HAE, there are already effective chronic options, including siRNA and antisense therapies. And the substitute risk isn’t only “another drug.” It could also be a better editor, a safer delivery system, or a next-generation approach that leapfrogs CRISPR-Cas9 in certain settings.

Hamilton's Seven Powers

Scale Economics (Emerging): A platform helps spread R&D and infrastructure costs across multiple programs—assays, delivery know-how, manufacturing processes, and regulatory playbooks. The bigger scale economics show up later, when commercial manufacturing ramps and volumes rise, but you can see the early shape of them as the pipeline grows.

Network Effects (Limited): This isn’t a consumer product. Treating more patients doesn’t create classic network effects. The closest analog is data—each trial and follow-up period improves understanding of safety, durability, and editing outcomes—but that advantage is real yet subtle, and competitors can generate their own datasets.

Counter-Positioning (STRONG): This is Intellia’s clearest power. The company staked its identity on in vivo systemic delivery early, and it became the first to show systemic CRISPR editing in humans. That matters because in vivo isn’t just “ex vivo, but inside the body.” It changes delivery, trial design, manufacturing, and risk. Competitors built around ex vivo workflows can pivot, but doing so often means rebuilding the core of what they are. Traditional pharma faces an even steeper climb without years of modality-specific repetition.

Switching Costs (Potentially STRONG): If a one-time therapy truly cures or meaningfully prevents disease, the ultimate switching cost is obvious: a cured patient doesn’t switch. There are also softer switching costs—center-of-excellence dynamics, physician comfort, and hospital processes. But this power only becomes real once there’s an approved product and a standard of care built around it.

Branding (Building): “First-in-human in vivo CRISPR” is a real credibility marker with investors, clinicians, and partners. But in biotech, brand is rented, not owned. It depends on years of durable efficacy, a clean safety story, and the confidence that the therapy performs outside the controlled environment of early trials.

Cornered Resource (MODERATE): Intellia’s ties to the Doudna ecosystem, its licenses through Caribou, and the clinical and operational know-how accumulated from being early all matter. But CRISPR IP has been contested, and talent is mobile. The resource is meaningful, but not untouchable.

Process Power (Emerging): This is the slow-burn advantage that can become decisive. Manufacturing LNP-CRISPR therapies, running trials in new modalities, and building regulatory muscle memory create a body of tacit knowledge that’s hard to copy quickly. Each program—successful or not—adds to that internal playbook.

Key Insight: Intellia’s advantage comes most from counter-positioning—getting out in front in in vivo—and from process power that compounds with every iteration. The long-term moat, if it forms, will be earned the old-fashioned way: sustained clinical outcomes, reproducible manufacturing, and the trust that comes from years of follow-up.

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

Bull Case

The optimistic thesis starts with the most important thing Intellia has already done: it showed that in vivo CRISPR editing can work in humans. Based on the interim data reported to date, NTLA-2001 has looked like a genuinely promising treatment for ATTR amyloidosis, with deep reductions in serum TTR that appear durable after a single infusion. If that effect translates into meaningful clinical benefit, the upside isn’t incremental—it’s paradigm-shifting: stop, and potentially reverse, a progressive disease without lifelong dosing.

That first proof point matters because it de-risks the platform itself. The hardest step for in vivo CRISPR was never designing a guide RNA. It was delivery, tolerability, and demonstrating you can cut the intended gene inside a living patient. Once that’s real, each follow-on program isn’t starting from zero. It’s starting from a validated delivery approach and a growing body of human safety and durability experience.

From there, the market opportunity widens quickly. Intellia doesn’t just have “an ATTR drug” or “an HAE drug.” In theory, it has a repeatable way to knock down liver-produced proteins implicated in disease. The liver is a high-leverage organ, and many genetic and metabolic conditions trace back to proteins made there.

The nearer-term bull catalyst is hereditary angioedema. Intellia has completed enrollment in the Phase 3 HAELO trial of lonvo-z for HAE, with topline data expected by mid-2026 and a potential U.S. launch in the first half of 2027. If that trial reads out cleanly, it would do two things at once: deliver Intellia’s first potential approval pathway that’s not entangled in the ATTR hold, and prove the company can execute not just on science, but on late-stage development and commercialization.

And if these therapies work as intended, pricing power follows. The logic is familiar across gene therapy: pay once for durable relief versus paying indefinitely for chronic treatment. The health-economics case can be compelling when a one-time intervention replaces years of expensive standard-of-care dosing.

Finally, the tech doesn’t stand still. Next-generation editors, improved delivery systems, and expanded tissue targeting are advancing across the industry. A platform company’s advantage is that it can incorporate those improvements over time, rather than being trapped inside a single product.

Bear Case

The cautious thesis begins with the most uncomfortable fact in the entire story: the risk isn’t hypothetical anymore.

The MAGNITUDE clinical hold is exactly the kind of binary event that can break a biotech narrative. “We were deeply saddened to learn that the patient who experienced grade 4 liver transaminase elevations and increased total bilirubin following a dose of nex-z in the MAGNITUDE phase 3 clinical trial, as reported on October 27, 2025, passed away last night.” Even if the hold is ultimately resolved, the interruption delays timelines and, more importantly, dents confidence in the safety envelope of systemic in vivo editing at scale.

Long-term safety remains the core unknown for the whole category. CRISPR is permanent. If unexpected consequences emerge years later—whether from on-target effects, immune responses, or something harder to predict—there’s no “stop taking the drug” option. Traditional medicines earn trust over decades of post-market use. In vivo gene editing hasn’t had that luxury.

Then there’s the operational reality: manufacturing. Supplying a clinical trial is hard; supplying a commercial market is harder. Batch consistency, cost of goods, and supply reliability all become make-or-break constraints when a therapy moves from dozens of patients to hundreds or thousands.

Reimbursement is another pressure point. Ultra-high-priced, one-time treatments are under growing scrutiny. Payers increasingly demand outcomes-based arrangements or novel payment structures, which can complicate uptake and revenue timing even after approval.

Competition isn’t slowing down, either. Beam Therapeutics is advancing base editing, which may avoid the double-strand breaks of Cas9. Verve is pursuing in vivo editing for cardiovascular diseases. And large pharma companies continue to build, partner, or acquire capabilities in gene editing, raising the bar on speed and resources.

Finally, there’s the plain financial gravity of development-stage biotech. Losses were $519.02 million, up from 2023. Intellia reported $670 million in cash, cash equivalents, and marketable securities, and has said that is expected to fund operations into mid-2027. But cash burn stays substantial, and if timelines slip or markets remain hostile, future equity raises—and dilution—remain a real risk.

Key Metrics to Track

For anyone tracking Intellia, two things matter more than everything else:

1. Clinical trial progress and readouts: Resolution of the MAGNITUDE hold, progress across late-stage trials, and the next topline data will drive the story. In pre-revenue biotech, clinical outcomes are the product.

2. Cash burn rate and runway: With limited revenue, cash is oxygen. How fast Intellia spends, and how long it can operate before needing to raise again, shapes negotiating leverage and dilution risk—especially when the stock is under pressure.

Secondary signals help frame the picture: partnership economics (validation and funding), regulatory designations (potentially smoother pathways), and competitor readouts (whether Intellia’s lead is widening or shrinking).

XIV. Epilogue: The Future of Programmable Medicine

We’re watching a new pharmaceutical paradigm come into focus. For the first time, medicine isn’t limited to blocking a protein or boosting a pathway. It can, at least in certain tissues and diseases, reach upstream and change the underlying genetic instruction set. Whatever happens to Intellia as a business from here, it has already helped prove that this is possible in living humans—and that alone earns it a permanent place in the story of modern biology.

The implications stretch well beyond the company’s current pipeline. If you can reliably and safely deliver gene editors to the right cells, the menu of possible targets expands fast: common cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, certain cancers, and a long tail of genetic disorders that today are managed, not solved. And, more speculatively, some people imagine gene editing playing a role in diseases of aging itself. The science is moving faster than the rulebook, and faster than society’s ability to agree on what should be allowed.

That’s why the ethical questions don’t sit on the sidelines—they are the sidelines. The He Jiankui scandal showed how quickly the technology can be misused, and how much public trust can be damaged by a single reckless act. As more gene-editing therapies reach patients, the access question becomes unavoidable: who gets the “one-time cure” when the price tags can reach into the millions? And where, exactly, is the boundary between treating disease and enhancing humans? The technology doesn’t draw that line. We do.

The competitive landscape is likely to evolve the way new modalities usually do: through a mix of consolidation and specialization. Some CRISPR companies will run out of time, money, or luck. Others will be acquired by larger pharma companies that decide they’d rather buy capability than build it. The independent survivors may look less like generalists and more like focused leaders in a particular delivery system, organ, or therapeutic category.

Regulators, too, have moved faster than many expected. In December 2023, the FDA approved CASGEVY for sickle cell disease—the first CRISPR-based therapy approved in the U.S. That milestone didn’t belong to Intellia, but it mattered to Intellia and to everyone building in this field. It signaled that CRISPR could clear the bar not just in a paper or a conference talk, but in the real world of manufacturing, safety, and long-term follow-up. And it underscored how compressed the timeline has been: from the Nobel Prize in 2020 to approved CRISPR medicines in 2023.

For Intellia, the next chapter is more tactical and more unforgiving. It has to navigate the ATTR clinical hold while pushing hereditary angioedema toward a potential approval path. If it succeeds, it could emerge as a commercial-stage leader in in vivo gene editing. If it fails, it will still have advanced the frontier—but at a cost that biotech investors know all too well.

And that’s what makes “success” here bigger than a stock chart. Yes, shareholders care about market capitalization. But the deeper scoreboard is human: ATTR patients who avoid heart failure and neurological decline, HAE patients freed from unpredictable and sometimes life-threatening attacks, families who stop living in the shadow of inherited disease. If one-time curative therapy becomes real at scale, it’s not just a better business model. It’s genuine medical progress.

The most surprising part may be the speed of the whole arc. CRISPR went from an odd bacterial immune mechanism to a programmable editing tool in 2012, to first-in-human trials in 2020, to FDA approval in 2023. The compounding pace of biology is accelerating, and it’s pulling medicine along with it.

For founders and investors, Intellia’s story is both inspiration and warning. Patient capital matters—measured in years, not quarters. The shift from scientific pioneers to operational leaders matters when you’re trying to survive the FDA, not just impress a lab meeting. Platform thinking creates real optionality. And even then, biotech remains brutally nonlinear: one serious adverse event can halt a program, reshape a narrative, and steal years from a timeline.

That’s the nature of breakthrough medicine. High risk. High reward. And consequences that matter in a way quarterly earnings never can.

We’re standing at the edge of programmable medicine. Intellia helped open that edge. What the industry builds from here—scientifically, commercially, and ethically—will shape medicine for the rest of the century.

XV. Further Learning

Essential Reading

If you want to go back to first principles, start with Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier’s work—the scientific spark that turned CRISPR from a bacterial curiosity into a programmable tool. For the story behind the science, Walter Isaacson’s The Code Breaker is the most readable way to understand the revolution, the rivalries, and the people who pushed it forward.

To understand Intellia as a business, go where the unvarnished details live: its SEC filings. The 10-Ks and 10-Qs lay out the pipeline with real specificity, alongside the financials and the risk factors that matter when you’re underwriting clinical-stage biotech. For the clinical side, the New England Journal of Medicine publications on NTLA-2001 and NTLA-2002 are the clearest, most rigorous window into how the data were generated and presented.

Industry Resources

To keep up with what’s changing week to week, outlets like Endpoints News and FierceBiotech track the gene therapy and gene-editing landscape as it evolves—new trial readouts, safety signals, financings, and partnerships. For the annual “state of the union,” JP Morgan Healthcare Conference presentations are where management teams set expectations, defend strategy, and signal what they think is coming next.

And if you want an accessible bridge between the bench and the clinic, the Innovative Genomics Institute, founded by Jennifer Doudna, publishes clear educational material on CRISPR technology and its medical progress.

Academic Foundations

For the original “starting gun,” read the 2012 Science paper that established CRISPR-Cas9 as a gene-editing system. From there, Cell and Nature papers map the hard part that made companies like Intellia possible: delivery—how you actually get editors into cells in ways that are safe, repeatable, and clinically meaningful.

Finally, for the rules of the road, FDA gene therapy guidance documents—especially the draft guidance on human gene therapy for rare diseases—are essential. They don’t just explain regulation; they explain how the agency thinks, what it expects, and why getting a therapy approved is as much about process and evidence as it is about scientific promise.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music