Nelnet Inc.: The Student Loan Giant That Became a Tech Conglomerate

I. Introduction: How Did a Nebraska Student Loan Servicer Survive Regulatory Extinction?

Picture Lincoln, Nebraska in the late 1990s. Modest office parks. Endless cornfields. The University of Nebraska football team as a civic religion. And “finance” meaning community banks and insurance—not high-flying Wall Street innovation.

In that setting, two lawyers, Mike Dunlap and Steve Butterfield, helped launch what would become one of the strangest reinventions in American financial services.

Nelnet was founded in 1996 as a spin-off from Union Bank & Trust, built to capitalize on federal student loan programs. It was, at the time, a straightforward bet: originate loans backed by the government, manage them at scale, and collect steady fees. But over the decades, that simple model morphed into something analysts still struggle to neatly categorize—a portfolio that spans student loan servicing, education payments technology, fiber-optic telecommunications, solar energy investments, and venture-style bets.

By 2024, Nelnet generated $1.35 billion in annual revenue, growing 15.70% that year. It employed more than 7,000 associates across offices worldwide. It serviced hundreds of billions of dollars in student loans, processed billions in tuition payments, and delivered gigabit fiber internet to communities across the Midwest.

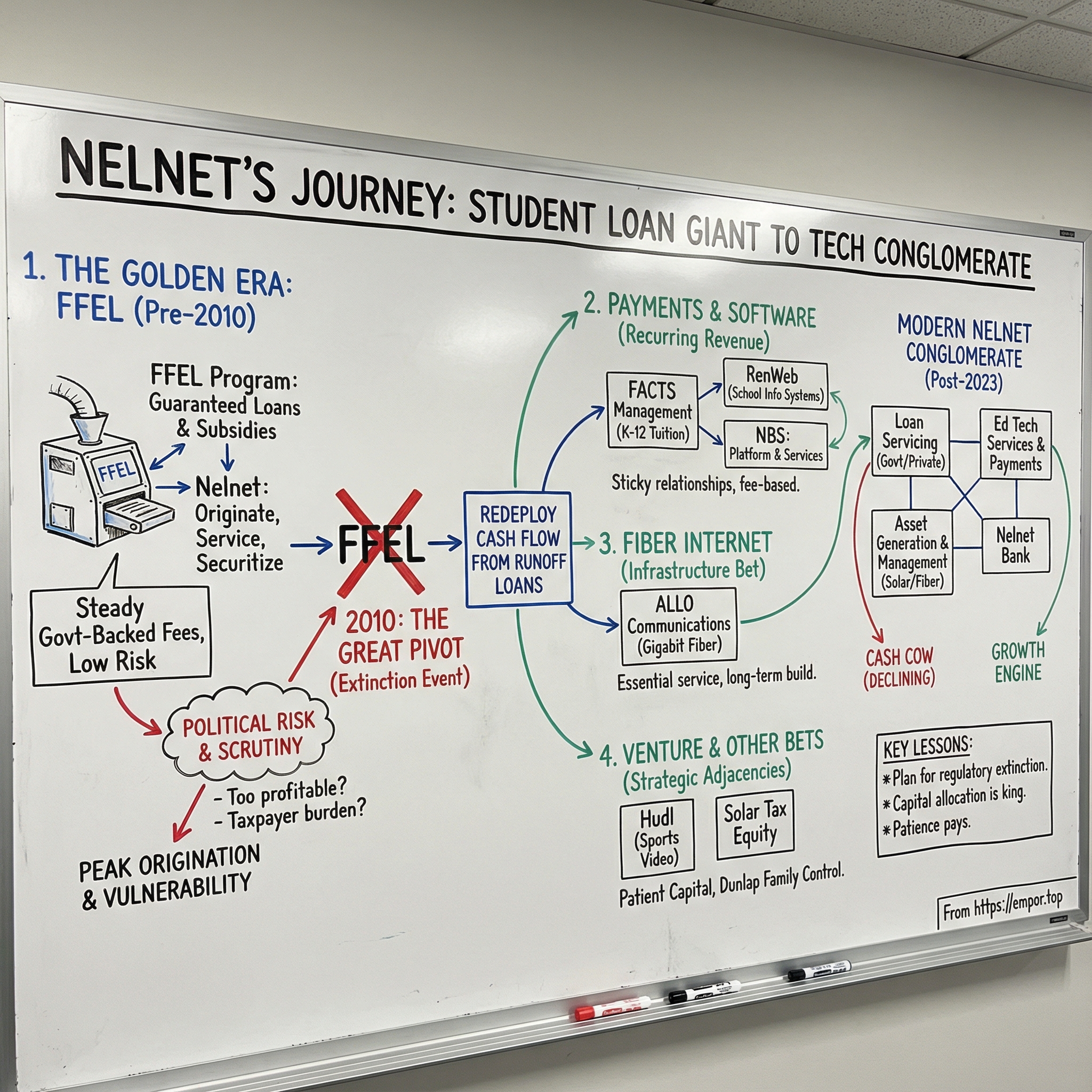

The paradox is that Nelnet’s original engine didn’t just slow down—it was deliberately dismantled. The Federal Family Education Loan Program, the government-guaranteed origination machine that made companies like Nelnet rich, was effectively ended by the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. After June 30, 2010, no new loans could be made under FFEL. The money printer was turned off.

And yet, more than fifteen years later, Nelnet wasn’t a corporate relic. Its stock hit an all-time closing high of 139.63 on December 22, 2025, with a 52-week high of 140.87. Shares had been listed at $21.65 back in December 2003—meaning a long-term holder would have seen a total return of about 465.31% over the last 21 years.

So how did a company built on government-guaranteed student loans keep winning after that system went away?

The answer is a rare mix: Midwestern patience, an aggressive but disciplined push into adjacent businesses, and leadership willing to say the quiet part out loud—that the core business was dying, and pretending otherwise would kill the company.

This is the story of Nelnet: a masterclass in capital allocation, regulatory adaptation, and building a second act before the first one ends.

II. Founding Context: The Student Loan Industry Before 2000

To understand why Nelnet existed in the first place, you have to understand just how unusually attractive federal student lending was in the 1990s.

For decades, the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) Program let private lenders make student loans that were subsidized and guaranteed by the federal government. FFEL loans were issued by banks and state-affiliated lenders, but Washington backstopped the credit risk. If a borrower stopped paying, the government absorbed the loss—not the lender.

And it didn’t stop at protection from defaults. The government also paid lenders interest subsidies designed to keep rates “affordable.” Put those together and you get the core truth of FFEL: lenders could earn steady, government-supported returns in a market where the biggest downside had been socialized.

It’s hard to build a more lender-friendly product than that.

By the late 2000s, the scale was enormous. In 2007–08, FFEL served about 6.5 million students and parents and originated roughly $54.7 billion in new loans—about 80% of all new federal student loans. This wasn’t a niche program. It was the system.

Nebraska, of all places, had deep roots in it. Nelnet’s lineage runs through Union Bank & Trust (UBT), which financed its first federal student loan in 1970. At the time, UBT was the only bank offering those loans across Nebraska, Colorado, Iowa, and Kansas. That early push built on the bank’s acquisition by Jay Dunlap, father of future Nelnet co-founder Mike Dunlap.

Over time, the Dunlap family kept expanding its education-finance footprint. In 1978, UBT grew through acquisitions—Labor Finance Industrial Bank and Packers Bank—and formed UNIPAC Service Corporation to handle nationwide student loan servicing. This wasn’t just lending. It was the infrastructure around lending: processing, servicing, scale.

Mike Dunlap entered that world directly. After graduating from the University of Nebraska College of Law, he joined UBT and UNIPAC in 1988. He brought legal training, but more importantly, a practical operator’s instinct for systems and process—exactly what this industry rewarded.

In 1996, Mike Dunlap and Stephen Butterfield formed Union Financial Services, the company that would become Nelnet. It rebranded in 1998, and then came the big leap: an IPO on the New York Stock Exchange in 2003. The name itself—short for “National Education Loan Network”—was a declaration that this wouldn’t stay a Nebraska business.

The timing couldn’t have been better. Borrowing was rising as college costs climbed, and public markets were still happy to fund scalable finance businesses. Going public on December 11, 2003 gave Nelnet the currency and capital to accelerate acquisitions and expand into a national player.

But the founding era also planted the tension that would define everything later. FFEL was too good a deal for lenders to stay politically invisible forever. The more profitable it became, the more obvious the question sounded in Washington: if taxpayers are taking the risk and paying subsidies, why are private companies collecting the economics?

That’s the DNA Nelnet carried forward—patient Midwestern builders who understood the mechanics of a complex, government-shaped market. It would serve them well. And then, eventually, it would force them to reinvent.

III. The Golden Era: FFEL and Loan Origination Dominance (2003-2010)

After the IPO, Nelnet stepped into what—at the time—looked like the permanent sweet spot of American finance: a government-designed market where the risk was capped, the rules were known, and scale rewarded the operators who could execute.

The basic engine was simple. Nelnet originated federally backed student loans, packaged them into student loan asset-backed securities (SLABS), serviced the borrowers, and lived off a steady mix of fees and the spread between its funding costs and government-supported returns. It was finance with training wheels—until it wasn’t.

By early 2005, Nelnet had climbed into the top tier of the industry. As of March 31, 2005, it ranked among the nation’s leaders in total net student loan assets, at $14.5 billion. From its headquarters in Lincoln, it did the whole stack: originate, consolidate, securitize, hold, and service student loans—mostly under FFEL.

It didn’t get there by growing slowly.

Nelnet pushed hard on acquisitions to build servicing scale and widen its footprint. In March 2000, it bought UNIPAC Service Corporation, a Denver-based servicing company founded in 1978. A few months later, in June 2000, it acquired In Tuition, Inc., a Jacksonville-based loan-servicing company. These were the kinds of deals that mattered in this business: more accounts, more processing capacity, more operational muscle.

The market around them was crowded and combative. Sallie Mae loomed large as the converted government-sponsored enterprise, while a long tail of regional players fought for share. Nelnet’s edge wasn’t flashy product innovation—it was customer service, process, and operational efficiency. Those sound like soft advantages. In servicing-heavy businesses, they’re everything. And they’d turn out to be portable when the rules changed.

In 2005, Nelnet also made a move that didn’t look like a lifeboat at the time—but absolutely was. The company joined with FACTS Management Co., then the largest provider of tuition payment plans in the country, and acquired an 80-percent interest in FACTS and its affiliates. FACTS had started in 1986 serving a single parochial school, then grew into the nation’s largest tuition management provider.

Back then, you could have described it as a tidy adjacency: a way to deepen relationships with schools and families. In hindsight, it was the early blueprint for a different kind of Nelnet—one built less on government-designed loan economics and more on recurring, fee-based services.

Then the ground started to shift.

In February 2007, New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo launched an investigation into alleged deceptive practices across the student loan industry. Nelnet was among the names pulled in, alongside The College Board, EduCap, Citibank, and Sallie Mae. The allegations centered on kickbacks, improper inducements, and gifts from loan providers to colleges and universities.

Nelnet agreed to provide $1 million to support a national financial aid awareness campaign. Nebraska Attorney General Jon Bruning later forgave that obligation after Nelnet announced it had reached a separate $2 million settlement with Cuomo’s office.

Financially, it was survivable. Strategically, it was a warning shot. The industry’s biggest vulnerability wasn’t credit risk. It was political risk—and the narrative that private companies were profiting too comfortably inside a taxpayer-backed system.

That narrative hardened with an audit. A U.S. Department of Education review found that from 1993 to 2007, Nelnet had used a loophole in federal tax legislation that allowed it to receive a higher interest rate on certain loans, generating $278 million from taxpayers.

Then came 2008.

When the financial crisis hit, the securitization machine seized up. Credit markets froze. SLABS became difficult to issue. And Washington stepped in to keep student lending moving at all. Through the Ensuring Continued Access to Student Loan Act (ECASLA) of 2008, Congress allowed the federal government to buy loans directly from FFEL lenders—an intervention that kept the system alive, but also made the private lenders feel a lot more optional.

So yes: these were Nelnet’s golden years. But the peak came with a tell. The same period that delivered the best economics also pulled the most scrutiny, the most investigations, and the most government involvement.

Peak profitability had become peak vulnerability. The era was ending. And whether management fully saw it yet or not, the company was drifting toward a brutal question: when the loan origination machine gets turned off, what exactly is Nelnet?

IV. The Great Pivot: Losing the Origination Business (2010-2012)

On April 24, 2009, President Barack Obama went straight at the logic of FFEL. He called for the program to end, arguing it was a wasteful, inefficient arrangement where “taxpayers… [were] paying banks a premium to act as middlemen—a premium that costs the American people billions of dollars each year.”

Washington’s math lined up with the message. In July 2009, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that shifting to direct government lending would save roughly $80 billion over a decade. Later revisions pulled that number down to about $61 billion, but the conclusion didn’t change: the political case for cutting out private lenders was strong.

The student loan industry didn’t take that quietly. Lenders and servicers lobbied hard, and America’s Student Loan Providers warned that “large scale changes in the financial aid delivery system should be carefully considered.” They were buying time, not winning the argument.

It wasn’t enough. The Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 effectively ended FFEL. After June 30, 2010, no new loans could be made under the program.

For Nelnet and its peers, this wasn’t a downturn. It was a deletion. The core business—originating new federally guaranteed student loans—simply stopped. The money printer didn’t slow down; it got unplugged.

So Nelnet did what most companies say they’ll do when their world changes, but few actually execute: it rewrote its identity. After 2010, the company pushed to reduce its dependence on interest income from owned loans and leaned into fee-based businesses—education technology, payments processing, telecommunications, renewable energy, and banking—designed to be steadier and less exposed to both interest rates and political rewrites.

The plan had two legs.

First: double down on servicing. Even if the government was now originating loans directly, it still needed contractors to answer phones, process payments, manage accounts, and keep the system running. Nelnet leaned into that operational role.

Second: accelerate diversification. Not random side bets, but adjacent businesses with recurring revenue and long-lived customer relationships—areas where Nelnet’s muscle memory in high-volume, high-compliance operations could actually translate.

Two financial realities made that pivot possible. The servicing business generated cash flow as the company reoriented. And the existing loan portfolio didn’t vanish overnight; it ran off over a long stretch as borrowers repaid—effectively a multi-year harvest period that threw off cash Nelnet could redeploy into new bets.

Over time, that shift showed up in the mix. By 2023, fee-based businesses like FACTS and Nelnet Campus Commerce were generating the majority of net income—evidence that the company’s center of gravity had moved away from holding loans and toward running operating businesses.

And the internal shift mattered just as much. Nelnet went from being a financial services company with a few operating lines on the side to an operating company that still happened to have financial assets. The same service culture that had been built handling borrower relationships became the template for serving schools, families, and communities in entirely different ways.

This is the inflection point that defines modern Nelnet. Most companies don’t survive the elimination of their core business model. The ones that do usually have three things: a strong balance sheet, leaders willing to face the ugly truth early, and at least one adjacency they can scale into. Nelnet had all three.

V. Building the Servicing Fortress and the Servicing Rollercoaster (2012-2020)

With origination gone, servicing became Nelnet’s remaining bridge to federal student lending. If the Department of Education was now the lender, companies like Nelnet were the operating layer—answering phones, taking payments, processing paperwork, and keeping millions of borrower accounts from collapsing into chaos. Winning and keeping those servicing contracts wasn’t just important. It was survival.

On paper, the work sounds painfully unglamorous: process payments, respond to borrower questions, manage income-driven repayment plans, and handle forbearance and deferment requests. But at national scale, “mundane” becomes mission-critical. One broken workflow can turn into millions of angry borrowers. One confusing communication can become a headline. Operational excellence wasn’t a nice-to-have—it was the product.

That’s why Great Lakes mattered.

Great Lakes had about 1,800 employees and had served as Great Lakes Higher Education Corporation Affiliates’ technology provider and student loan servicing company. By the end of 2017, it was servicing $224.4 billion in government-owned student loans for 7.5 million borrowers.

In 2018, Nelnet made the definitive move: it acquired Great Lakes Educational Loan Services. Nelnet paid $150 million in cash for 100% of the stock, and the deal reshaped the competitive map overnight. When the acquisition closed on February 7, 2018, the combined company became the largest student loan servicer in the United States—servicing $397 billion in loans, around 42% of all student loans.

The logic was straightforward and, given the direction of the industry, almost inevitable. If the servicing world was going to shrink, the winners would be the ones with the most scale, the best unit economics, and the strongest technology. Nelnet and Great Lakes had already been collaborating for nearly two years in a joint venture to build a new servicing system for government-owned loans—modern infrastructure designed to handle more volume without breaking.

But there was a catch: servicing was becoming politically toxic.

As borrowers struggled, repayment programs multiplied, and forgiveness debates intensified, the public perception of servicers deteriorated fast. Confusion that was often rooted in policy complexity landed, in practice, on the companies answering the phones. Regulators took notice. Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Joy Campbell announced a $1.8 million settlement with Nelnet, resolving allegations that the company failed to appropriately communicate with borrowers about renewing Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans—precisely the kind of compliance-and-communications issue that can define a servicer’s reputation.

Then came the event that broke the business model’s rhythm entirely: COVID-19.

In March 2020, the Trump administration paused federal student loan payments and interest accrual as a temporary relief measure. The pause covered roughly 90% of outstanding student loans, affecting about 38 million people with a combined balance of $1.5 trillion. The primary relief—no interest accrual and no required monthly payments—ran from March 13, 2020 to September 1, 2023.

For borrowers, it was a lifeline. For servicers, it was brutal. Servicing revenue is tied to accounts and activity. When borrowers weren’t paying, the economics of the system changed immediately—and the “temporary” pause stretched on for more than three years, suppressing revenue far longer than anyone expected. The total cost of the payment pauses since spring 2020 was estimated at around $195 billion, and for servicers it meant years of operating in a world where the normal revenue engine simply wasn’t spinning.

And even as the pause dragged on, the contract environment got tougher. The Department of Education continued shifting away from volume-driven economics toward performance-based requirements, squeezing margins. Later, that trend culminated in a contract transition: on April 1, 2024, Nelnet began earning revenue under its new Unified Servicing and Data Solution (USDS) contract, which replaced its legacy servicing contract. On a blended per-borrower basis, the revenue under USDS was lower than under the legacy contract.

By the end of this period, the direction was obvious. Student loan servicing wasn’t a growth business anymore—and it might not be a stable one long-term. The best thing Nelnet had done wasn’t becoming bigger in servicing. It was building a future that didn’t depend on servicing at all.

VI. The Diversification Machine: Payments, Software, and Services

With the core student loan business in long-term decline, Nelnet started doing something that would’ve sounded almost heretical during the FFEL boom: it used student-loan cash flows to buy and build operating businesses.

The strategy was consistent even when the targets weren’t. Look for recurring revenue. Find defensible niches. Stay close to education and community services. And lean into what Nelnet already knew how to do—run high-volume, high-compliance operations without falling apart.

FACTS Management: The K-12 Payments Foundation

The 2005 FACTS deal turned out to be the prototype for “new Nelnet.”

FACTS had started in 1986 with one parochial school and grew into the nation’s largest provider of tuition management services for private and parochial K-12 schools, along with colleges and universities. It handled the unglamorous but mission-critical work: tuition payment plans, online payment processing, reporting, and data integration.

And the value proposition was simple. Many private schools live and die by tuition timing. Families want flexibility; schools need predictability. FACTS sat in the middle—helping families spread payments out, while giving schools steadier cash flow and fewer collection headaches. It also offered financial aid assessment, tying payment plans to affordability.

Over time, FACTS scaled to serve more than three million students and families across more than 11,500 K-12 schools, managing about $9 billion in tuition funds annually.

That adjacency to student loans was obvious—same households, same underlying need, different product. But the economics were different in all the ways Nelnet needed them to be. FACTS had sticky relationships, recurring fees, and far less exposure to federal policy swings.

Then FACTS expanded from “payments” to “platform.”

FACTS acquired RenWeb School Management Software, a school information system used by private and faith-based schools. RenWeb helped more than 3,000 schools run core administrative workflows—admissions, scheduling, billing, attendance, and gradebook management. The 2014 move widened the moat: if a school used FACTS for tuition and RenWeb for daily operations, switching became harder. The combined offering aimed to deliver more integrated software and services to thousands of schools.

By the mid-2020s, that arc—payments to platform—was a big part of Nelnet’s identity. “This past year was a record-breaking one for Nelnet Business Services, one of our three core businesses,” CEO Jeff Noordhoek said about 2024.

Hudl: The Surprise Home Run

If FACTS was the blueprint, Hudl was the curveball that worked.

Hudl was founded in 2006 by University of Nebraska graduates David Graff, Brian Kaiser, and John Wirtz. Graff had seen the problem up close while working with the Nebraska football program: game film was painful to share, painful to analyze, and expensive to manage. Hudl made it easy.

Early financial backing came from Nelnet and Jeff and Tricia Raikes—local capital backing local founders.

At first glance, it didn’t fit. What does sports video analysis have to do with student loans?

But Nelnet wasn’t buying “sports.” It was buying distribution through schools and a product used by coaches, athletes, and recruiters—right in the middle of the education ecosystem. The connection was less about a neat org chart and more about where the product lived.

Hudl later announced $72.5 million in funding and grew into the world’s most utilized video recording, editing, distribution, and analysis tool for coaches, athletes, and recruiters, with more than 3.5 million athletes in 40 countries.

“With tens of thousands of youth, high school, college and professional teams, millions of viewers, and millions of hours of content, the team at Hudl has built an easy-to-use platform that is the standard across all sports,” said Mike Dunlap, Nelnet’s executive chairman and a Hudl board member.

Hudl raised $230 million from investors including Accel, Nelnet, and Bain Capital, became a category leader, and expanded through acquisitions and international growth. Raikes and Dunlap were each directors and 5 percent stakeholders in the company. And the relationship ran both ways: Hudl CEO David Graff later joined Nelnet’s board of directors.

ALLO Communications: The Telecom Bet

Then came the move that made outsiders do a double take.

In 2015, Nelnet agreed to acquire ALLO Communications, a Nebraska-based telecommunications provider offering fiber-optic service to homes and businesses—broadband internet, television, and phone services. ALLO was founded in Imperial, Nebraska in 2003 and positioned itself around building “gigabit communities.”

The rationale wasn’t subtle: diversify Nelnet into an entirely new operating business, one with recurring revenue and essential-service characteristics. “We are excited to team up with ALLO to support their rapid growth plans and diversify Nelnet into a new operating business,” said Jeff Noordhoek. He framed it as community infrastructure—fiber that could change what families, start-ups, and small businesses were able to do.

Nelnet acquired 92.5 percent of ALLO for $46.2 million, then invested significant additional capital to build networks in Lincoln, Hastings, Imperial, and Norfolk, Nebraska, and Fort Morgan and Breckenridge, Colorado.

In 2020, to accelerate the buildout, Nelnet brought in SDC Capital Partners. Funds managed by SDC made a $197 million equity investment for roughly a 48% ownership stake.

ALLO eventually provided communications services to 53 cities across Nebraska, Colorado, Arizona, and Missouri, spanning more than 1.4 million people.

Renewable Energy: Tax-Advantaged Diversification

Nelnet also built a renewable energy investing arm—another diversification that looked odd until you saw the throughline.

Nelnet became a tax equity investor in solar projects, investing more than $200 million across over 100 solar project sites nationwide, powering nearly 45,000 homes. Beginning in 2018, Scott Gubbels started and led Nelnet’s Renewable Energy group, which focused on solar tax equity funding and portfolio management.

Nelnet’s tax equity investments later spanned 19 states and 252 solar projects, with enough capacity to power nearly 118,000 homes each year.

Different businesses, same pattern: essential services, recurring economics, and a deliberate step away from dependence on a shrinking student loan portfolio.

VII. The Conglomerate Question: Berkshire Hathaway or Too Complicated?

Walk through Nelnet’s business today and the diversity is impossible to miss. It’s no longer just a student loan company with a few side projects. Nelnet now runs loan servicing, education technology services, and payments businesses, and it organizes itself into four segments: Loan Servicing and Systems, Education Technology Services and Payments, Asset Generation and Management, and Nelnet Bank.

Then you add what sits outside the consolidated boxes—its stake in ALLO’s fiber networks, its equity in Hudl, its solar investments—and the structure starts to look less like a single “company” and more like a small portfolio manager that happens to be publicly traded.

So what is this, really? Berkshire Hathaway for education and essential services? Or a collection of unrelated bets that’s destined to trade at a permanent conglomerate discount?

The bull case is that the structure is the strategy. Nelnet can take cash generated from mature, runoff businesses and redeploy it into areas with longer runways. It’s not forced to bet the whole company on any one industry or any one regulatory regime. And because ownership and leadership are willing to think in years, not quarters, Nelnet can fund projects that would be hard to defend in a more Wall Street-driven boardroom.

That long-term posture traces back to its founders. Michael S. Dunlap established the company that would become Nelnet with Stephen Butterfield in 1996, and Dunlap served as Chairman and CEO from the beginning. The Dunlap family’s continued involvement has given Nelnet something rare in public markets: permission to be patient. ALLO’s fiber buildout, Hudl’s long arc of growth, and the solar tax equity platform all demanded sustained capital and the willingness to wait for the payoff.

The bear case is simpler: complexity has a cost. Running student loan servicing, K-12 payments software, renewable energy investing, and a fiber telecommunications business doesn’t just require different skill sets—it can require different cultures. Investors have a hard time valuing the whole when each part behaves differently, and that confusion often shows up as a discount in the stock. Even if each business is solid, the combined story can feel messy.

The honest answer is somewhere in the middle. Diversification almost certainly saved Nelnet. Without FACTS, ALLO, and the other non-loan businesses, Nelnet would be living out the endgame of a shrinking servicing franchise with fewer and fewer places to grow.

But survival isn’t the same thing as optimization. The open question now is whether this structure is the best way to build value from here—or whether it mainly preserves what Nelnet already fought so hard to keep.

VIII. Current State and the 2020s Transformation

When the COVID-era payment pause finally ended in September 2023, Nelnet moved into a new chapter—one where student loans were no longer the whole story, but still a meaningful part of the machine.

By the fourth quarter of 2024, the company was back to posting clear profitability under GAAP: net income of $63.2 million, or $1.73 per share, versus a GAAP net loss of $7.9 million in the same quarter the year before.

“We are pleased with the results in the fourth quarter of 2024 and optimistic about the opportunities ahead in 2025,” CEO Jeff Noordhoek said. “This past year was a record-breaking one for Nelnet Business Services, one of our three core businesses.”

Servicing, meanwhile, kept evolving in the direction Nelnet had been bracing for. The new federal contract paid less per borrower, but the volume still mattered. As of December 31, 2024, Nelnet serviced $532.4 billion across government-owned loans, FFELP, private education loans, and consumer loans for 15.8 million borrowers.

The more interesting shift was where growth started showing up: private loan servicing.

In July 2024, Discover Financial Services announced the sale of an approximately $10 billion private education loan portfolio—about 400,000 borrowers—to partnerships managed by two global investment firms, with Discover retaining servicing responsibility. The conversion of those loans began in September 2024. Around the same time, Nelnet’s results also reflected conversions of loan portfolios from Discover and SoFi Lending Corp., which drove higher private education loan servicing volume in the fourth quarter of 2024 and the first quarter of 2025.

Then ALLO—Nelnet’s “wait, they do fiber?” bet—delivered a moment of real validation. On June 4, 2025, Nelnet received $410.9 million in cash proceeds from ALLO for the redemption of a portion of Nelnet’s voting membership interests and all of its outstanding preferred membership interests. Nelnet recognized a $175.0 million pre-tax gain.

“We’re pleased with Nelnet’s strong operating results to kick off 2025,” Noordhoek said. “In a challenging and uncertain economic environment, all our core businesses are performing well and contributing to this momentum.”

Put it all together and the company’s self-description starts to make more sense. Management has been increasingly explicit that Nelnet is becoming an education technology and services business—not a student loan company that happens to own some other assets. The FFEL portfolio is still running off and still throwing off cash, but the point now is what that cash funds: payments, software, servicing systems, and long-duration operating businesses built to outlast the political life cycle of federal student loans.

IX. Playbook: Business and Investing Lessons

Lesson 1: Regulatory Risk is Existential—Plan for Your Business to Disappear

The FFEL elimination in 2010 wasn’t a headwind. It was an extinction event. If your economics depend on a government program or a specific regulatory structure, you don’t get to treat policy as “background.” You have to ask, early and often: what happens if this disappears? Nelnet made it through because it started building a second act before the first one was legislated away.

Lesson 2: Capital Allocation is Everything When Core Business is in Runoff

Once origination died, Nelnet was left with something both dangerous and powerful: a shrinking loan portfolio that still generated meaningful cash. That’s the classic Buffett-style problem in miniature—your legacy business throws off money, but it’s not where the future is. Nelnet’s move was to redeploy into adjacent operating businesses with recurring revenue. The contrast is sharp: many competitors leaned harder into servicing, and today they’re stuck in a margin-compressing, politically exposed corner.

Lesson 3: Strategic Adjacencies Matter More Than Pure Financial Returns

From the outside, Nelnet can look like a grab bag. From the inside, there’s a thread. FACTS sits inside schools. ALLO builds essential infrastructure for communities. Hudl lives in athletics departments and education ecosystems. The cohesion isn’t perfect, but it’s real—and it’s what makes the portfolio feel like a strategy rather than a collection of unrelated wagers.

Lesson 4: Family Control Enables Long-Term Thinking

A more typical public-company setup would have pushed Nelnet toward quick wins: optimize, cut, buy back stock, and squeeze what’s left. Instead, the Dunlap family’s influence created room for patience. Bets like ALLO’s fiber buildout don’t work if you can’t stomach years of heavy investment before the payoff. Nelnet could.

Lesson 5: Boring Businesses with Pricing Power Beat Sexy Businesses with Competition

Tuition management. School payments. Fiber internet. None of it sounds like the future—until you look at the unit economics. These are markets where switching costs are real, customers don’t churn casually, and the revenue is predictable. In other words: the kind of “boring” that compounds.

Lesson 6: Sometimes the Best Offense is Accepting Your Core is in Decline

This might be the hardest one. When your identity is built around a flagship business, admitting it’s shrinking can feel like surrender. But denial is worse. Student loan servicing has faced political backlash, contract resets, and margin pressure. Nelnet’s advantage wasn’t that it saved servicing. It was that it stopped treating servicing as the future—and used the cash it still produced to buy time, build options, and widen the company’s definition of what it could be.

X. Porter's 5 Forces and Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces: Education Payments and Services Business

Threat of New Entrants (Medium): Writing software is relatively easy; earning a school’s trust isn’t. K-12 schools are relationship-driven, procurement moves slowly, and selling into thousands of private schools can mean long sales cycles and high customer acquisition costs. New entrants can show up, but breaking in at scale is hard.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Low): This business mostly runs on software talent, payment rails, and cloud infrastructure—important, but not scarce or exclusive. Nelnet isn’t dependent on a single proprietary input or a must-have partnership that can hold it hostage.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (Medium-High): Schools operate with tight budgets and negotiate aggressively. Still, once a payments system is integrated and families are used to a portal, switching becomes disruptive—new workflows, retraining, new communications—so schools don’t change vendors lightly.

Threat of Substitutes (Medium): Stripe or Square could process payments, and school management platforms like PowerSchool can expand into adjacent features. But schools aren’t generic merchants. They have unique workflows—tuition plans, financial aid, reconciliation, reporting—which is where purpose-built K-12 solutions tend to win.

Industry Rivalry (Medium): The market is competitive and fragmented. FACTS faces rivals like PowerSchool Holdings, Edusys, Infinite Campus, and Independent School Management. FACTS is a leader, but not a monopoly—so competition shows up as feature races, service quality battles, and price pressure in school renewals.

Porter's 5 Forces: Student Loan Servicing (Legacy Business)

Threat of New Entrants (Low): This is a gated market. The Department of Education controls access through contracts, and the direction has been consolidation, not expansion.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers (High): For federal loans, the Department of Education is essentially the only customer—and it sets the rules. Terms are effectively non-negotiable, and when requirements change, servicers either comply or lose the business.

Bargaining Power of Buyers (N/A): Borrowers don’t choose their servicer. Accounts are assigned based on program rules and operational considerations, not consumer preference.

Threat of Substitutes (High): The clearest substitute is the government doing more of the work itself—reducing or eliminating the role of private servicers. Forgiveness programs and other policy shifts also shrink the pool of loans that need to be serviced.

Industry Rivalry (High): Under the USDS system in 2024, the Department contracted with five companies—Nelnet, Aidvantage, MOHELA, EdFinancial, and Central Research, Inc. Competition is intense, with pricing pressure and constant regulatory scrutiny shaping the economics.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

1. Scale Economies (Moderate): Payments platforms benefit from scale as technology costs spread across more transactions. ALLO also needs density market-by-market to make the network economics work. But neither business is structurally winner-take-all.

2. Network Effects (Weak): School payments and servicing don’t meaningfully improve simply because others use them; most relationships are independent. Hudl is the exception: the more coaches and athletes on the platform, the more valuable it becomes—especially in recruiting.

3. Counter-Positioning (Moderate): ALLO’s push into fiber in underserved markets is a direct counter-position to incumbent cable operators. Nelnet’s education-first focus also differentiates it from companies chasing broader consumer fintech, even if it’s not an absolute shield.

4. Switching Costs (Strong in FACTS/NBS, Moderate in ALLO): In education payments, switching means integrations, training, new processes, and reintroducing families to a new portal. That friction is real, and it’s one of Nelnet’s most defensible advantages. In fiber, switching exists too, but it’s generally less operationally complex.

5. Branding (Moderate): Nelnet is recognized in K-12 education circles, but it’s not a mainstream consumer brand. In student loans, reputation is complicated by the broader industry’s perception problems.

6. Cornered Resource (Weak): There’s no single exclusive asset—no irreplicable patent, locked-up distribution channel, or unique partnership that competitors can’t work around.

7. Process Power (Moderate): Years of servicing at scale created operational muscle and institutional knowledge that’s hard to copy quickly. That same execution discipline shows up in ALLO’s buildout as a developing capability.

Overall Assessment: Nelnet’s strongest power is switching costs in education payments and services, backed by process power from decades of operational execution. The diversification strategy is coherent, but it doesn’t automatically produce compounding moats. ALLO, in particular, is a bet on scale and counter-positioning—and the jury remains out.

XI. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

Even in decline, student loan servicing can still be a cash engine for years. The FFEL portfolio doesn’t vanish overnight; it runs off gradually, producing interest income and servicing fees that can be redeployed into whatever comes next. Nelnet’s edge here isn’t that the legacy business is growing—it’s that management has shown it can harvest it without betting the company on it.

Meanwhile, the businesses Nelnet wants to be known for are holding up. In the second quarter of 2025, revenue from the Education Technology Services and Payments segment rose slightly year over year, to $118.2 million from $116.9 million. That’s not a breakout, but it’s steady momentum—and it reinforces the thesis that FACTS and NBS have long runways as schools and families keep shifting payments and workflows online.

ALLO is the biggest “if it works, it really works” lever. Fiber is essential infrastructure, demand for faster connections keeps rising, and underserved markets can offer room to expand without fighting the most brutal forms of competition. Nelnet’s partnership with SDC Capital Partners helped validate the value of the asset, and the later redemption didn’t just look good on paper—it returned meaningful cash and crystallized a gain.

Then there’s the market setup. Nelnet often trades like a company that’s hard to categorize, and that confusion can show up as a conglomerate discount. If the market ever starts valuing the parts more fairly—or if management finds ways to make the portfolio easier to understand—patient investors could benefit from that gap closing.

Family ownership reinforces the long-game mindset. The Dunlaps aren’t building around the next quarter’s narrative; they’re allocating capital as if they’ll still be stewarding the company decades from now. That patience is exactly what made ALLO, solar tax equity, and long-cycle education services possible in the first place.

And finally, Hudl is pure optionality. As of late 2024, major stakeholders included Bain Capital, Accel Partners, and Nelnet. If Hudl ever goes public or is sold strategically, Nelnet’s stake could unlock value that doesn’t show up cleanly in the day-to-day story.

The Bear Case

The most obvious bear point is also the simplest: the core student loan business is shrinking, and there’s no policy path that reliably reverses that. Contract restructuring has compressed margins, forgiveness programs shrink balances, and every year the legacy economics matter less.

ALLO is also a risk, not just an upside story. Fiber buildouts demand heavy upfront capital, and returns can take years to prove out. If competitive markets end up more contested than expected, the unit economics may never justify the investment.

It’s also possible the conglomerate discount is earned. Running education payments, telecommunications, and solar investing isn’t just diversification—it’s operational complexity. Different industries demand different playbooks, and focus often beats breadth.

Even in the “good” part of the portfolio, competition is real. Education payments is crowded, with players like PowerSchool and Blackbaud holding scale advantages in certain segments. And FACTS’s core strength in private and faith-based schools can also be a ceiling if expansion doesn’t broaden that addressable market.

Another risk is that growth leans too heavily on deals. If organic growth isn’t enough, then execution depends on buying the right assets at the right prices and integrating them well—never a guarantee.

The regulatory and reputational overhang remains, too. Student loan servicing can become a political target regardless of which party is in power. Being in the middle of that system means periodic scrutiny is part of the job description.

And family control cuts both ways. It enables long-term thinking, but it also means minority shareholders have limited influence. The company will reflect Dunlap family priorities—and those priorities may not always align with maximizing near-term value for outside investors.

Key KPIs to Watch

1. NBS Payment Volume and Take Rates: This is the clearest “new Nelnet” growth engine. Payment volume shows adoption; take rates show whether Nelnet is keeping pricing power as competition heats up.

2. Loan Servicing Volume Trends: As of June 30, 2025, Nelnet serviced $516.1 billion across government-owned, FFELP, private education, and consumer loans for 14.5 million borrowers. The key question is whether growth in private loan servicing can meaningfully offset federal runoff.

3. Capital Allocation Decisions: What Nelnet buys, builds, or funds next matters as much as quarterly results. In a portfolio company, the quality of capital allocation is the product—and the biggest determinant of whether diversification compounds value or dilutes it.

XII. Epilogue: What's Next

The big question still hangs over everything: is Nelnet mostly a survivor—ingenious at outrunning extinction—or has it actually pulled off a durable transformation?

There are a few plausible futures from here.

Scenario 1: ALLO scales and becomes the growth engine. Fiber demand keeps rising, ALLO reaches profitability as it densifies its networks, and the market starts valuing Nelnet less like a legacy finance company and more like an infrastructure owner. In this version of the story, telecommunications grows big enough to outweigh what’s left of student lending.

Scenario 2: Payments becomes the center of gravity. Education technology and payments keep compounding while the student loan book steadily runs off. Over time, student loans shrink into a small slice of the overall value, and Nelnet looks, behaves, and gets valued more like an education services and software company.

Scenario 3: The conglomerate breaks up. Management decides the cleanest way to unlock value is simplification—spin-offs, sales, or other separation moves that let ALLO, NBS, and the remaining loan assets stand on their own. The theory is straightforward: remove the confusion, erase the conglomerate discount.

Scenario 4: The “muddle through” path. Nelnet continues executing well across the portfolio, generating respectable returns, but never gets the clean narrative or obvious catalyst that changes how investors see the company.

If there’s a meta-lesson here, it’s bigger than Nelnet: sometimes the best move is to admit—early—that your industry is dying, and redeploy capital while you still have the time and cash flow to do it. The companies that spent the 2010s fighting for FFEL’s restoration weren’t really fighting for a strategy; they were fighting for the past. Many are still paying for that.

And the counterfactual is worth sitting with. What if Nelnet had responded to FFEL’s end by doing the most “shareholder-friendly” thing in the short term—buying back stock and shrinking? A declining loan portfolio can’t carry a standalone company forever. Without a second act, Nelnet likely wouldn’t have had one at all. Diversification wasn’t a luxury. It was the plan to stay alive.

That’s what makes the Nelnet story feel uniquely American: Midwestern pragmatism applied to a brutally political market, and long-term thinking in a world that rarely rewards it. From Union Bank & Trust financing Nebraska students in 1970 to ALLO delivering gigabit fiber to communities across the Midwest and beyond by 2025, the business changed almost completely—without losing its underlying temperament.

For investors, Nelnet remains a case study in capital allocation under pressure. The ending is still unwritten. But the approach has been consistent: accept reality, preserve optionality, and keep building for the long term.

XIII. Further Reading and Resources

Key Primary Sources

- Nelnet 10-K Annual Reports (2010, 2015, 2020, 2024) – The best place to track how Nelnet’s mix shifts over time, segment by segment, and how management explains each pivot.

- Department of Education Federal Student Aid Reports – The clearest window into servicing contracts, performance metrics, and the rules servicers actually have to live under.

- Nelnet Investor Presentations – How management frames the diversification strategy in plain language, and what they emphasize (or don’t) in different cycles.

- CFPB Student Loan Servicing Reports (2015-2020) – Essential context on the compliance environment, where reputational risk came from, and how scrutiny shaped the industry.

- ALLO Communications Press Releases – Updates on where ALLO expands and how it talks about growth and network buildout.

Industry Context

- Josh Mitchell’s reporting on FFEL elimination and the broader industry collapse for the political and regulatory backdrop that forced Nelnet’s reinvention.

- Congressional Budget Office analyses of student lending program costs, which help explain why FFEL became an easy target.

- Brookings Institution research on the payment pause and restart, to understand how COVID-era policy rewired servicer economics.

Comparable Analysis

- PowerSchool Holdings filings for a grounding in the education software landscape Nelnet competes in.

- Sallie Mae and Navient investor materials for a useful contrast on how other student-loan-era giants adapted (or didn’t).

- Research and filings from regional fiber providers to benchmark ALLO’s positioning and economics market by market.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music