NMI Holdings: The Hidden Giant Behind America's Homeownership Dreams

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

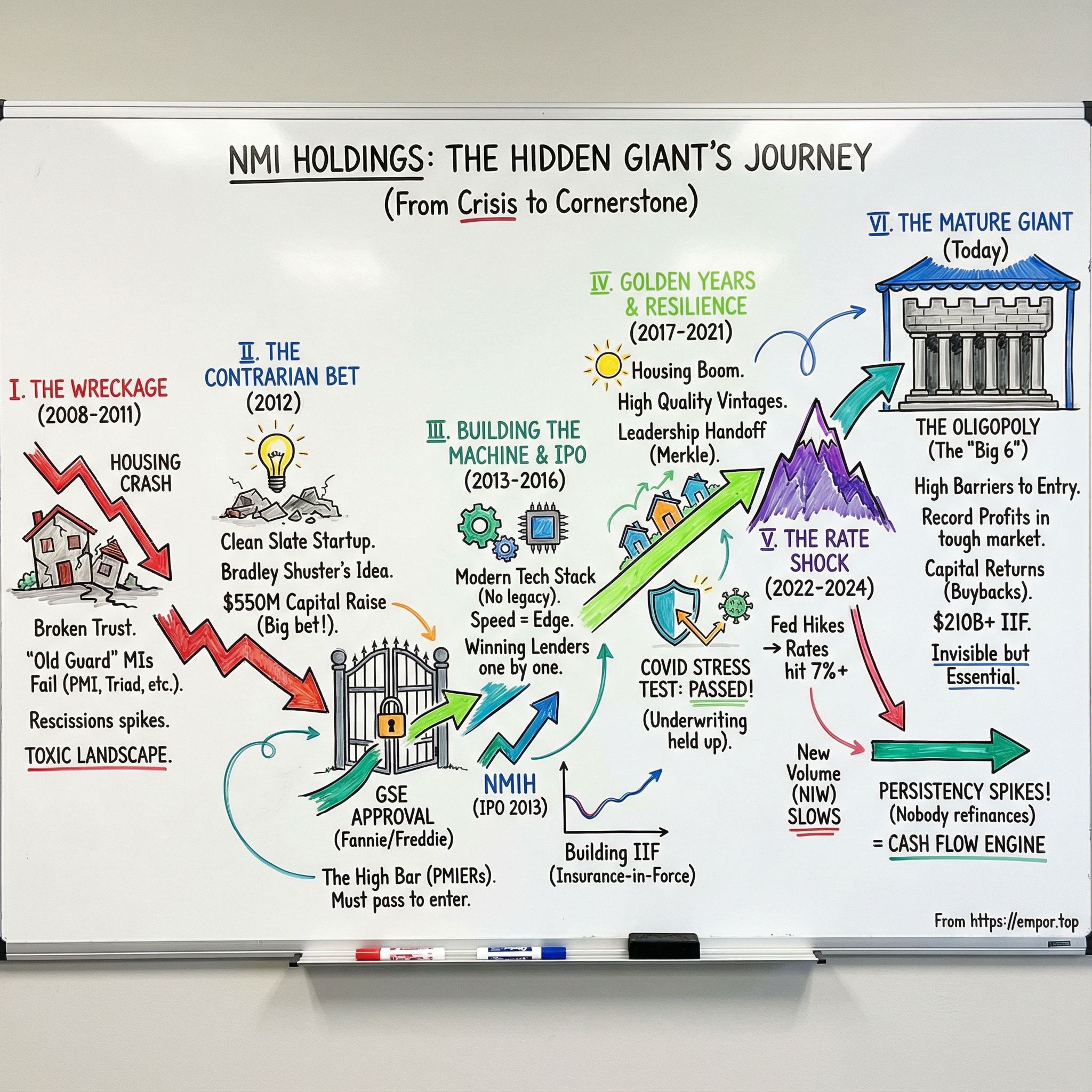

Picture a Tuesday afternoon in 2011. The housing crisis isn’t history yet—it’s still in the air. Foreclosure signs dot suburban streets from Nevada to Florida. Lenders are battered, regulators are wary, and “trust” in the mortgage machine feels like a punchline.

And then a small group of insurance veterans walks into that wreckage with an idea that sounds, on its face, absurd: let’s start a mortgage insurance company. From scratch. Right now.

That company became National Mortgage Insurance Corporation, the operating subsidiary of NMI Holdings. And the arc of what followed—turning a contrarian, post-crisis startup into a billion-dollar enterprise—has become one of the more unlikely success stories in modern financial services. NMI was established in 2011 and is headquartered in Emeryville, California. Today, it has $210.2 billion of primary insurance-in-force and generates a 17.4% return on equity.

But here’s the twist: you’ve almost certainly never heard of them.

If you bought a home with less than 20% down in the last decade, there’s a meaningful chance NMI sits quietly behind your mortgage—collecting premiums, absorbing risk, and making the deal possible in the first place. They operate in one of the most consequential and invisible corners of American finance: private mortgage insurance.

This is a picks-and-shovels story, not a gold-rush story. While everyone debates home prices and interest rates, just six companies sit at the junction between aspiring homeowners and the American Dream. They’re the gatekeepers that make low-down-payment lending work, and the shock absorbers that keep Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from taking on even more risk. NMI is the youngest of those six—born in crisis, built with a clean slate, and now competing head-to-head with incumbents like MGIC and Radian.

So why dig into this now? Because the next chapter of American housing is being written in real time. Interest rates have stayed elevated, affordability has cratered, and a wave of millennial and Gen Z buyers is trying to break into a market that feels increasingly out of reach. If you want to understand where housing goes from here, you have to understand the companies that make low-down-payment homeownership possible—how they work, how they compete, and what happens when the cycle turns.

II. Understanding the Business: Mortgage Insurance 101

Before we can appreciate what NMI Holdings pulled off, we need to understand the strange little corner of finance they chose to enter. Private mortgage insurance exists because of one stubborn math problem: most Americans can’t put 20% down, and lenders don’t love the idea of lending 95% of a home’s value with nothing standing between them and a loss.

That 20% hurdle blocks a lot of would-be homeowners who could otherwise handle the monthly payment just fine. PMI is the workaround. It lets families with limited savings buy with less down, while still giving lenders and investors enough comfort to fund the loan. In other words, it’s a system that makes low-down-payment homeownership possible—while also creating a profitable niche for the companies willing to insure it.

The setup is counterintuitive. In most insurance, the person paying the premium is the person who gets the benefit. With PMI, it’s split. The borrower pays the premium—typically somewhere in the neighborhood of 0.46% to 1.50% of the loan amount per year, depending on things like credit score and loan-to-value. But if something goes wrong, the check doesn’t go to the borrower. It goes to the lender. When a borrower defaults and the foreclosure sale doesn’t cover the full balance, the mortgage insurer reimburses the lender for a portion of the shortfall.

The reason this whole structure exists traces back to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—the government-sponsored enterprises that sit at the center of U.S. housing finance. By charter, the GSEs can’t simply load up on low-down-payment loans unless those loans come with defined credit protection. PMI is one of the main ways that protection shows up, which is why private mortgage insurance plays such a central role in keeping the conventional mortgage market liquid.

And here’s the key distribution twist: PMI companies don’t really sell to consumers. Their true customers are lenders—the Wells Fargos, the Quickens, and thousands of regional banks and credit unions. The borrower pays, but the lender chooses the insurer. That little detail shapes everything about competition in this industry, and it’s a major reason why breaking in as a new player is so hard.

Historically, private mortgage insurance has been around since the late 1950s, helping borrowers get conventional loans—meaning loans not insured or guaranteed by the federal government—with down payments below 20%. Premiums generally scaled with the down payment: the less you put down, the more you pay. And the industry has long operated under a stabilizing constraint: mortgage insurers must put half of their premium inflow into contingency reserves that generally can’t be accessed for 10 years, except in unusually large loss events. That rule pushes insurers to price based on long-term loss expectations, which is one reason rates tend not to whip around month to month.

That long-term mindset is also baked into the economics. This is not like property and casualty insurance, where claims show up quickly and policies reset every year. Mortgage insurance has a long tail. A loan insured today might look perfectly fine for years—and then sour much later if the economy turns or home prices fall. The industry talks in “vintage years” for a reason: loans originated in 2006 behaved nothing like loans originated in 2016, and those differences can echo across a decade-plus of performance.

To follow the business, investors tend to anchor on two metrics. First, New Insurance Written (NIW): the dollar amount of new mortgages insured in a given period. Second, Insurance-in-Force (IIF): the total amount of insured mortgages still on the books. NIW is the inflow. IIF is the base that throws off recurring premium revenue.

Because once a policy is written, the mortgage insurer collects premiums month after month—until the borrower builds enough equity to cancel (typically around 80% loan-to-value), or refinances into a new loan that wipes the old policy away. That creates the central quirk of the model: mortgage insurers can keep earning even when new mortgage volume slows, as long as their existing book sticks around. And the flip side is just as weird—refinancing booms, which are great for mortgage originators, can actually be bad for mortgage insurers because they accelerate the runoff of their most profitable in-force portfolio.

III. The Old Guard & The Housing Crisis

To appreciate why NMI could even exist, you first have to understand the carnage that created the opening.

By 2007, private mortgage insurance was an eight-company club. Within a few years, three of those eight had failed and couldn’t fully pay claims. The firms that survived did so badly scarred that the whole industry’s credibility was shot.

Before the crash, the roster looked familiar: MGIC, the pioneer founded by Max Karl, who essentially invented modern mortgage insurance. Then Radian, PMI Group, Genworth, Triad, Republic, and a handful of smaller players. During the housing boom, these businesses expanded fast—and not just in volume, but in risk. In the name of “affordability,” they leaned into products and loan types that left them exposed when defaults surged.

And they made another mistake that looks almost unbelievable in hindsight: they largely didn’t price for regional housing risk, even though everyone understood that house prices don’t fall evenly across the map. When the bubble popped, that lack of nuance turned into a blender. The rapid growth in insurance written at the top of the cycle didn’t just hurt the insurers; it contributed to the strain on the entire mortgage system, including the GSEs. Among loans originated in 2007, the share that became delinquent despite being insured jumped sharply—approaching the ugly default behavior of the infamous 2006 private-label vintage.

The destruction, once it started, was brutal. The industry’s total market value fell more than 90% from mid-2007 to the end of 2008—roughly $24 billion in value erased in about a year and a half.

If you want a single company that captures what that felt like, look at PMI Group. It was the third-largest mortgage insurer at the time—and it’s where NMI founder Bradley Shuster had spent more than a decade as a senior executive. PMI didn’t just struggle; it unraveled in public. It lost money for 16 straight quarters, including a staggering $1.01 billion loss in the fourth quarter of 2007. In October 2011, Arizona regulators seized PMI’s main subsidiary and cut claim payouts to 50%, deferring the rest. The next month, on November 23, 2011, PMI filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy with $736 million in listed debt.

Triad Guaranty wasn’t far behind. Formed in 1987, Triad stopped writing new mortgage insurance in July 2008 and entered voluntary run-off. It spent years fading out, then filed for Chapter 11 in June 2013. At its peak, it employed around 250 people in Winston-Salem and had been one of the eight primary providers in the country. By mid-2008—barely six months into the financial crisis—it was already done writing new business.

Republic followed a similar trajectory. By 2011, the club had shrunk from eight players to five, and the survivors weren’t healthy—they were limping, scrambling to satisfy capital requirements and win back trust.

And then came the move that poisoned relationships for years: rescissions. In 2008 and 2009, mortgage insurers ramped up claim denials, with rescission rates running around 20% to 25%. To lenders and to Fannie and Freddie, it felt like the insurers were disappearing exactly when they were supposed to be most reliable. The entire point of mortgage insurance is that it pays when the borrower can’t. In the crisis, too often, it didn’t. And nobody forgot.

For borrowers, the fallout was immediate. Jumbo borrowers and anyone with weaker credit found it harder to get a loan at all. Even borrowers with solid credit but limited savings—the classic PMI customer—ran into tighter standards and higher prices as the industry tried to protect itself.

That was the backdrop: toxic, distrusted, seemingly beyond repair. And it was into that wreckage that a new entrant would soon walk in and say, essentially, we can build a mortgage insurer you can trust again.

IV. Birth of NMI: Launching into the Storm (2011-2012)

The person who decided to take on this broken industry wasn’t an outsider with a theory. He was an insider with scars.

Bradley Shuster had spent seventeen years inside mortgage insurance before founding National Mortgage Insurance Corporation in 2012. He served as Chairman and CEO from 2012 to 2018. Before National MI, he was a senior executive at The PMI Group, where he led international and strategic investments and served as CEO of PMI Capital Corporation. And before PMI—back when the world still thought housing risk was boring—he was a partner at Deloitte, leading Northern California’s insurance and mortgage banking practices.

On paper, it was the perfect background for an almost impossible job: a CPA and CFA who could speak the language of regulation, accounting, and risk modeling, but who also understood the gritty operational reality of mortgage insurance. He’d even been instrumental in PMI’s sale of its Australian operations to QBE for about $1 billion. Shuster knew how value got created in this business. And then he watched it get vaporized.

After the crisis, from 2008 to 2011, he took on consulting work with private investors looking at insurance opportunities. Those years became his post-mortem. What failed? Where were the blind spots? What would lenders and the GSEs need to see to trust an insurer again? If you were going to build a new MI company, what would you do differently on day one?

His pitch to investors flipped the conventional wisdom on its head. The very things that made mortgage insurance look untouchable were, in his view, the opening. Incumbents were trapped under legacy losses that would drag on capital for years. Relationships were strained after the rescission wars. Systems were old. A new insurer—built clean, properly capitalized, and disciplined—could show up with something the market suddenly valued above all else: reliability.

The capital raise came fast and big. On April 24, 2012 (perfected on April 26), NMIH raised $550,000,000 in gross proceeds by selling 55,000,000 shares at $10 per share. In the wreckage of the mortgage crisis, more than half a billion dollars of private money flowed into one of the most distrusted corners of finance. That wasn’t optimism. That was a thesis—and a willingness to bet real capital on it.

National MI was headquartered in Emeryville, California, and its parent, NMI Holdings, was built around the idea that experience and a clean balance sheet could matter as much as price in this market. But none of that mattered without one thing: approval from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. In conventional mortgages, the GSEs aren’t just customers—they’re the gate. They set the eligibility rules, dictate standards, and decide who gets to play.

And the bar had gotten higher. The GSEs were under federal conservatorship, rewriting oversight as they went, and mortgage insurers were now expected to prove they could withstand stress—not just in theory, but in capital and in operations. In 2010, Essent became the first new private mortgage insurer approved by the GSEs since 1995. National MI would follow in 2013, joining a club that remains extraordinarily difficult to enter.

That environment cut both ways. The housing market was still fragile, which meant volume wouldn’t come easy. But the new, tougher framework also played to a startup’s advantage: if you could build to the new standards from scratch, you didn’t have to retrofit a battered legacy business to get there.

Inside National MI, Shuster moved quickly to build the operating muscle that would decide whether the company survived its first decade. Claudia Merkle joined in May 2012 as Senior Vice President of Underwriting Fulfillment and Risk Operations. She was promoted to Executive Vice President and Chief of Insurance Operations in 2013, then Chief Operating Officer in 2016, and President in May 2018. Her early arrival signaled what Shuster understood: mortgage insurance isn’t forgiving. Underwriting discipline isn’t a slogan—it’s the business. The loans you insure in your first year can define your results ten years later.

National MI also wasn’t alone. Essent Guaranty had formed earlier, backed by a deep bench of financial services investors. It announced $500 million in equity funding from Pine Brook Road Partners, Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, PartnerRe, and Renaissance Re. And in a twist that captured the moment perfectly, Essent even bought Triad Guaranty’s information technology and operating platform as Triad wound down—acquiring Triad’s proprietary mortgage insurance software and much of the supporting hardware.

Two post-crisis startups coming to the same conclusion—and both finding serious backers—wasn’t just coincidence. It was the market quietly admitting something important: the old guard might survive, but the future of mortgage insurance didn’t have to look like its past.

V. The Market Awakens: 2013-2016 Growth Phase

When the housing market finally started to heal, it didn’t do it politely.

Home prices hit bottom in early 2012 and then began to move again. Originations recovered. First-time buyers—missing in action through the worst years—started showing up. And the biggest change wasn’t just volume. It was quality. Post-crisis lending standards were tighter, documentation was stricter, and the loans being originated looked nothing like the anything-goes vintages that blew up the old MI industry.

For National MI, that shift was the whole bet coming to life. They were writing policies on cleaner borrowers, collecting strong premiums, and assembling the kind of book that—if underwriting held—would age into a profit engine. Mortgage insurance is a long game: what you write in 2013 and 2014 doesn’t just generate revenue today, it becomes the seasoned portfolio that can carry you through the next downturn.

To win business, National MI leaned on three things that sounded basic but were decisive in practice: technology, service, and speed.

The incumbents still had plenty of scale, but many were operating on legacy systems built for a different era. National MI didn’t have to retrofit anything. They built their stack from scratch, designed integrations to fit modern lender workflows, and focused on turning approvals around fast. In mortgages, speed isn’t a nice-to-have. Every extra day a loan sits waiting is another day the borrower can shop, another day the rate can move, another day the whole deal can die.

That made the distribution fight—getting in the door with lenders—worth the pain. And it was pain. Big lenders almost never bet on one insurer. They spread volume across multiple MIs to diversify counterparty risk and keep pricing competitive. For a new entrant, that meant earning trust in tiny increments: win a test allocation, prove you can underwrite and service cleanly, pay what you’re supposed to pay, and then ask for a little more.

Essent, the other post-crisis startup, showed what “getting in” could look like at scale. As of June 30, 2013, it had master policy relationships with approximately 800 customers, including 21 of the 25 largest U.S. mortgage originators in the first quarter of 2013. Essent believed those customers represented nearly 70% of annual new insurance written in the private MI market. National MI was chasing the same outcome—one lender relationship at a time.

Meanwhile, the old guard wasn’t rolling over. MGIC and Radian were bruised, but still very much alive—raising capital, restructuring, and fighting to hold share. The difference was gravity. They were still carrying the weight of their crisis-era books: elevated claims, capital pressure, and management attention pulled backward, even as the market finally started moving forward.

Quarter by quarter, National MI’s new insurance written climbed. And as the flow of new business accumulated, the more important number—the insurance-in-force—started to build. NIW is what you do this quarter. IIF is what you’ve built. And in mortgage insurance, that growing stock is what eventually determines the company’s earnings power.

By 2015, National MI had crossed a key threshold: it wasn’t just an idea with capital anymore. It was licensed in all 50 states, approved by both GSEs, and doing business with hundreds of lenders. Profitability still sat out ahead on the road—but now you could see it.

VI. Going Public: The 2013 IPO

Less than two years after raising its initial capital, NMI Holdings decided to step onto the public stage.

In early November 2013, NMIH priced its initial public offering at $13.00 per share. The stock began trading on November 8 on the NASDAQ under the symbol “NMIH.”

This wasn’t a blockbuster fundraising moment. The IPO raised about $27.34 million—small on purpose. NMI already had the war chest from its 2012 private placement. The real point of going public was different: open a permanent channel to the capital markets, give early investors liquidity, and earn the kind of credibility that comes with SEC filings, quarterly calls, and public scrutiny.

The offering closed on November 14, 2013, subject to customary closing conditions. NMI sold about 2.1 million shares, with a tiny number coming from selling stockholders. Underwriters also had a 30-day option to purchase up to an additional 315,000 shares from the company at the IPO price.

Of course, going public this early came with real trade-offs. NMI was still in build mode, not profit mode. Wall Street’s quarterly scoreboard can be unforgiving, and there was skepticism about timing—some worried the company was arriving late in the housing recovery, just as the cycle might be peaking.

But the upside was meaningful. Public equity gave NMI a tangible recruiting tool—stock that could help it hire and retain talent in a business where experience matters. The transparency also played well with rating agencies, which fed into credibility with the GSE ecosystem. And inside the company, the cadence of public reporting forced a new level of operational rigor.

In the early years, the stock was volatile. Markets were trying to price a company that was still losing money on paper while its underlying engine—new insurance written turning into recurring premiums—was quietly compounding. If you only looked at GAAP earnings quarter to quarter, you saw red ink. If you understood the model, you saw a book being built.

More capital markets activity followed. In February 2018, NMI completed a secondary public offering of 3,700,000 shares, raising $78.63 million at $21.25 per share. By then, the story had changed: the company had reached consistent profitability, and the stock had climbed well above its IPO price.

VII. The Golden Years: 2017-2021

From 2017 through 2021, the bet finally paid off in full. U.S. housing shifted into a sustained boom—fueled by low interest rates, a wave of millennial demand, and then the pandemic-era reshuffling of where and how people wanted to live. Prices climbed. Transactions stayed brisk. Confidence came back.

For mortgage insurers, it was close to an ideal setup. Purchase originations were strong, which meant a steady stream of new insurance written. And while refinancing is usually the mortgage insurer’s nemesis—because it cancels policies before they’ve had time to become really profitable—this time it was less damaging than it might have been. Many of the loans getting refinanced were relatively new, so there wasn’t a huge pile of mature, high-margin policies getting wiped out overnight.

National MI used that environment to keep climbing. Market share rose steadily, and the company cemented itself as a real top-tier competitor—even while going up against incumbents with far more scale. The cultural choices from the early days mattered here. Lenders weren’t just buying a rate; they were buying responsiveness, consistency, and a partner that could keep the gears turning when mortgage pipelines got chaotic.

That maturity showed up inside the company, too. NMI Holdings, Inc. announced that Claudia Merkle, the company’s President, would succeed Bradley Shuster as Chief Executive Officer effective January 1, 2019. Shuster, the founder, Chairman and CEO, moved into the role of Executive Chairman. He continued to lead the Board, oversee special projects, and stay involved with key stakeholders—working closely with Merkle as she took over day-to-day leadership.

It was the kind of leadership handoff that signals strength, not stress: the founder who built the machine stepping back, and an operator who had been there from the early build-out years stepping forward.

And by now, the economics that make mortgage insurance such a peculiar business started to shine. In the early life of a mortgage insurance “vintage,” the risk is front-loaded—those first few years are when delinquencies tend to appear. But as time passes, borrowers pay down principal, home prices (hopefully) rise, and equity builds. The pool gets safer. Claims fall. Premiums keep coming. National MI’s early books, written under tighter post-crisis standards, were now aging into exactly what Shuster had promised investors they could become.

Then COVID-19 arrived—an event that, on paper, should have been a mortgage insurer’s worst nightmare. For a brief stretch, it looked like the industry might be staring down a replay of 2008. Millions of borrowers entered forbearance. The word “default” was suddenly back on everyone’s lips.

But the wave never broke. Stimulus and policy support helped households stay current. And the housing market did the opposite of collapse—it surged. Borrowers worked through forbearance without turning into claims at anything like crisis levels. The post-2010 underwriting playbook—better documentation, better credit quality, more discipline—held up under a stress test nobody would have voluntarily chosen.

By the end of 2021, the company looked nothing like the audacious startup of 2012. As of December 31, 2021, NMIH’s audited GAAP consolidated financial statements reported assets of $2,450,581,000, liabilities of $884,795,000, and shareholders’ equity of $1,565,786,000. Operations for 2021 produced net income of $231,130,000.

In under a decade, NMI had gone from an idea launched in the rubble of the housing crash to a business producing more than $230 million in annual net income—and it had done it by building the kind of book the old industry forgot how to write.

VIII. The Interest Rate Earthquake: 2022-2024

The Federal Reserve’s inflation-fighting campaign in 2022 hit the mortgage market like a sudden change in gravity. Rates that had floated near 3% during the pandemic sprinted past 7%—levels Americans hadn’t seen in more than two decades. Buyers’ purchasing power collapsed. Purchase activity fell. And the refinancing machine, which had been running nonstop, effectively shut off.

For mortgage insurers, it produced a reality that looked bad from the outside and great from the inside. Yes, new insurance written dropped sharply. But the existing book performed beautifully—and it all came down to one simple behavioral truth: when you’re sitting on a historically low mortgage rate, you don’t refinance.

Even if rates were expected to drift down over time, refinancing stayed limited because the incentive was close to nonexistent for a huge share of homeowners. And when borrowers don’t refinance, they don’t pay off their mortgages. Which means the mortgage insurance attached to those loans doesn’t disappear.

That’s persistency, and it became the defining theme of 2022 through 2024. Policies that might normally have rolled off after five or six years were now expected to stay in force much longer—eight, ten, or more. Every extra month meant another premium payment, and in a mature MI book, those premiums can fall through at very attractive margins.

The industry had a name for it: the paradox of high rates. Lower new volume, but better unit economics and longer duration. National MI’s insurance-in-force kept growing even as new originations slowed.

The results were striking. Net income for the full year ended December 31, 2024 was $360.1 million, or $4.43 per diluted share, compared to $322.1 million, or $3.84 per diluted share, for the year ended December 31, 2023. Revenue in 2024 was $650.97 million, up 12.43% from $579.00 million the year before, while earnings rose 11.80% to $360.11 million.

Record profits—in what most people would describe as a terrible environment for housing.

But the calm on the back book came with a fight up front. With fewer new mortgages being written, the competitive temperature rose fast. Industry-wide, NIW was roughly half of what it had been in the record-setting year of 2020, when total volume topped $600 billion. In 2024, the six active underwriters wrote $298.9 billion. In a smaller market, share is zero-sum, and everyone pushed harder to win allocations.

National MI ended 2024 with $46 billion of total NIW volume and a record $210.2 billion of high-quality, high-performing primary insurance in force. Even with the headwinds, the portfolio kept compounding.

That environment also reshaped what “good strategy” looked like. With fewer opportunities to pour capital into growth, returning capital became the obvious move. Share repurchases took center stage, and the company announced its Board of Directors authorized an additional $250 million share repurchase plan effective through December 31, 2027.

IX. The Competitive Landscape & Industry Structure

Private mortgage insurance today is a classic oligopoly: six companies, enormous barriers to entry, and just enough mutual visibility that pricing usually doesn’t spiral into a self-destructive race to the bottom. The cast is familiar if you live in this world: MGIC (the original), Radian, Arch Capital’s mortgage insurance unit, Enact (formerly Genworth), Essent, and NMI.

NMI is still the smallest by insurance-in-force, but it’s far from an afterthought. By the end of the quarter, it was writing new business at roughly the same pace as Arch. As of September 30, NMI had $218.4 billion of insurance-in-force. Essent—the other company built from scratch after the Great Financial Crisis pushed three players into run-off—was the next smallest at $247 billion.

So why only six? And why will there likely never be more? Because the gatekeepers are real, and they’re stacked on top of each other.

First, capital. You need hundreds of millions of dollars before you can write a single policy. And once you start writing, you don’t get to “grow into” your balance sheet later. Under PMIERs—the Private Mortgage Insurer Eligibility Requirements—your capital cushion has to scale with the risk you take on. As of June 30, 2024, the industry held more than $26.8 billion in PMIERs available assets, a 171% sufficiency ratio.

Second, GSE approval. If you want to insure loans that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will buy, you need to be an approved insurer under PMIERs. That’s not a formality. It’s a multi-year proving ground where you have to demonstrate operational capability, capital adequacy, and a management team the system can trust. During NMI Holdings’ third quarter earnings call, management was asked about the possibility of a new entrant. Adam Pollitzer, President and CEO, said the company was aware of the development—but emphasized it’s “a very high bar,” and that just meeting the PMIERs requirements demands a large amount of capital.

Third, time. Mortgage insurance is a long-tail business. New entrants typically have to stomach years of losses while they build an in-force book large enough to generate durable earnings. After what happened in 2008, there just aren’t many investors eager to fund another multi-year wait in a sector with a proven capacity for catastrophic downside.

Within that structure, the competitive story of the last couple of years has been about share in a smaller market.

MGIC, for example, moved from the fourth-largest underwriter in 2023 to the top spot in 2024. It grew to $55.7 billion of new insurance written from $46.1 billion—a 46% increase. It’s still the scale leader, backed by decades of lender relationships and the biggest balance sheet in the group.

Radian also gained ground. Its new insurance written reached $14.3 billion, up from $9.5 billion and $13.9 billion over comparable periods. Its market share rose to 17.6%, making it the only other MI besides MGIC to increase share. “Our primary mortgage insurance in force, which is the main driver of future earnings for our company, grew to another all-time high of $277 billion,” CEO Rick Thornberry said.

And then there’s the matchup everyone watches: NMI versus Essent. They were both born out of the same post-crisis insight, funded with similar levels of initial capital, and built to win trust in a damaged industry. In a way, they validate the idea that a clean-sheet MI could work. In practice, they’re often chasing the same lender allocations, with the same playbook: service, consistency, and execution.

Across the industry, management teams have kept a steady refrain: pricing is still balanced and constructive, and the recent rise in macro uncertainty hasn’t meaningfully changed pricing dynamics so far.

The scars of 2008 still shape behavior. Pricing discipline—once treated as optional—is now part of the culture. Companies compete hard, but more often on responsiveness and relationships than on cutting rates to levels that don’t make sense. And the oligopoly structure reinforces that. With only six players, nobody gets to pretend they don’t know what everyone else is doing.

X. Business Model Deep Dive: The MI Money Machine

Once you see how mortgage insurance works over time, the appeal becomes obvious. Premiums arrive steadily, month after month. Claims, by design, are infrequent. And if you underwrite well, that spread doesn’t just create profit—it compounds into strong returns on equity.

You can see the steady drumbeat in NMI’s recent results. Total revenue came in at $173.2 million, up from $166.5 million in the fourth quarter and $156.3 million in the first quarter of 2024. Net premiums earned were $149.4 million, compared to $143.5 million in the fourth quarter and $136.7 million in the first quarter of 2024.

Underneath those topline numbers is the core dynamic of the product: the loss curve. Mortgage insurance has a very specific rhythm. The risky window is early—roughly the first one to three years—when a borrower has the least equity and the fewest sunk costs. If a loan is going to go bad, it often goes bad before the homeowner has built much of a cushion.

But if the borrower makes it through that period, the odds improve with time. Principal gets paid down. Home prices, in many environments, drift higher. Equity builds. And equity is the enemy of default. It’s a lot harder to walk away from a home when you’ve got something real to lose.

That’s why “seasoned” books are so valuable, and why NMI’s decade-long build now matters so much. The portfolio is older, safer, and still throwing off recurring premium revenue. The loss ratio did move around—12.0% versus 7.2% in the third quarter and 6.2% in the fourth quarter of 2023—but even at 12%, it’s still low for an insurance product. The bigger point is what it signals: this is a high-quality book that, so far, simply hasn’t been producing many claims.

Then there’s the metric that quietly controls everything: persistency. Every extra month a policy stays in force is another month of premium. And in a world where nobody wants to refinance out of a low-rate mortgage, policies stick around.

NMI’s persistency was flat at 84.7% from the first quarter. That’s high. In more “normal” times, when refinancing is common, persistency can live in the 70s. High rates flipped the model on its head: fewer new policies coming in, but the existing portfolio sticking around longer and earning more.

Capital discipline is the other half of the engine. Mortgage insurers don’t get to run thin—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac require approved insurers to meet PMIERs, a risk-based capital and operational framework. The game is to hold enough capital to stay comfortably compliant, but not so much that returns get smothered by idle equity.

For NMI, that balance has translated into meaningful per-share compounding. Book value per share excluding unrealized gains and losses reached $29.80, up 17% year over year, and the company generated an annualized return on equity of 15.6% in the fourth quarter. In a business that’s fundamentally built around prudence and low-frequency losses, mid-teens ROE is exactly why mortgage insurance can look so good when it’s working.

And there’s one more layer: investments. Premiums don’t immediately leave the building—they sit on the balance sheet, waiting for claims that may or may not ever come. Those dollars get invested, largely in conservative fixed income. When interest rates are higher, that portfolio throws off more income, adding a second stream of earnings on top of underwriting.

In other words, done right, the mortgage insurer gets paid to take risk—and then gets paid again while waiting to see if the risk ever shows up.

XI. The Regulatory & GSE Relationship

To understand private mortgage insurance, you have to understand who really sets the rules. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac aren’t just big customers. In practice, they function like quasi-regulators, because if your insurance can’t wrap loans that are going to be sold to the GSEs, you’re not a meaningful player in the conventional market.

The centerpiece is the Private Mortgage Insurer Eligibility Requirements, or PMIERs. Developed under FHFA oversight, PMIERs lays out the aligned requirements an MI company must meet to be approved to insure loans delivered to, or acquired by, Fannie and Freddie. PMIERs took effect in December 2015 and was revised in March 2019.

Since the Enterprises issued the aligned PMIERs standards, they’ve revisited them periodically with a clear goal: make sure counterparties can pay claims through the full economic cycle. That’s not abstract. It’s the lesson the system paid for in 2008. One major focus has been what counts as “Available Assets”—the capital and liquidity mortgage insurers are allowed to rely on to pay claims. The GSEs have pushed for those assets to be high quality, highly liquid, and actually there when stress hits.

This entire framework exists because the crisis exposed the nightmare scenario. When mortgage insurers denied claims or couldn’t fully pay them, they didn’t just damage their own reputations—they undermined confidence in the whole housing finance chain. PMIERs is the institutional response: tighter rules, broader oversight, and a willingness to adjust standards as the market evolves.

Then there’s the second regulator: the states. Mortgage insurers have to be licensed in all 50 states and the District of Columbia to operate nationally, and each jurisdiction comes with its own filings, examinations, and ongoing requirements. Keeping up with 50-plus separate regulatory relationships isn’t paperwork. It’s a real operational burden—and another reason the club stays small.

Over all of it hangs the biggest unresolved question in housing finance: conservatorship. Fannie and Freddie have been under federal conservatorship since 2008, and every few years a new wave of proposals shows up—release them, restructure the market, shrink their footprint, eliminate them entirely. None of it has been resolved. As Mattke put it, “Many things could happen” in any release scenario. The GSEs could try to reduce their role, which would affect how much conventional volume flows through the system and, by extension, how much flows to private MI. Or the balance could shift in the other direction, depending on how policymakers weigh the GSEs versus the Federal Housing Administration.

For now, the direction of travel has been consistency. FHFA Director Thompson and her team, along with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, have shown ongoing commitment to PMIERs and to the industry’s role. The stated aim is to keep conventional mortgages accessible and affordable, while making sure the system is still standing when the cycle turns.

XII. Porter's 5 Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

Everything we’ve talked about so far points to the same conclusion: it’s brutally hard to start a mortgage insurer. You need enormous upfront capital, you have to survive a long approval and licensing process, and even after you’re “open,” you’re typically staring down years of building before the economics really show up. The last successful new entrant was Arch Capital’s mortgage insurance unit in 2014. Before that, it was NMI and Essent. No one has broken in since—and the system is designed to keep it that way.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

For an MI company, the key “inputs” are capital and reinsurance. If you’re well-managed and have credible ratings, capital markets are generally open. Reinsurance, too, tends to be a competitive marketplace with multiple firms willing to provide risk transfer. NMI’s history of executing quota-share and excess-of-loss reinsurance transactions is a good signal here: supply has been available when they’ve wanted it.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

On the other side of the table sit lenders—and they know exactly what they’re buying. Volume is concentrated, and the biggest lenders can pressure pricing and terms simply because they can shift allocations. Essent, for example, reported master policy relationships with roughly 800 customers, including 21 of the 25 largest U.S. mortgage originators. That gives you a sense of both the breadth of the buyer base and how much the biggest players matter.

Still, it’s not a pure commodity market where you can swap providers overnight with no friction. There are real switching costs: system integrations, training, and the relationship capital built over years. Most lenders also use multiple MIs, which creates leverage—but it also means no single insurer can take any relationship for granted.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

PMI isn’t the only way to get a borrower into a low-down-payment loan. FHA and VA programs are direct alternatives, especially for lower-income borrowers, because they effectively bundle credit protection into the government-backed loan structure. When PMI and GSE pricing rises, it can push some borrowers toward FHA or VA if the economics look better for them.

There are other workarounds too. Piggyback loans—often structured as 80-10-10—can substitute for MI when rate spreads make them viable. And portfolio lenders can avoid MI altogether on loans they keep on their own books.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH

This is a six-player fight, and it stays intense because growth isn’t evenly distributed. When the overall origination market is flat—or shrinking—market share becomes a zero-sum game. Adding to that, once private MIs adopted the “black box” version of risk-based pricing, quarterly share became more volatile as lenders shifted flow and insurers tuned pricing.

The product itself is largely standardized. So the battle tends to happen on execution: service levels, speed, tech integrations, and relationship quality. And when volumes fall, rivalry spikes—because everyone is chasing a smaller pool of new loans.

XIII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

Scale Economies: MODERATE

There are meaningful fixed costs in this industry—technology, compliance, and the ongoing work of staying in good standing with the GSEs. The bigger your insurance-in-force, the more you can spread those costs out.

But mortgage insurance isn’t software. Underwriting still takes experienced people, and when claims do show up, the work scales with the number of policies and the complexity of files. NMI also still operates at a scale disadvantage versus the largest incumbents like MGIC and Radian, who have bigger books and deeper infrastructure.

Network Economies: NONE

This is not a network effects business. Insuring more borrowers doesn’t make the product more valuable to the next borrower, and it doesn’t create a self-reinforcing flywheel. Growth helps through scale, not through network dynamics.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK (Historically Strong)

NMI’s original wedge was classic counter-positioning: a clean balance sheet versus crisis-damaged incumbents, modern systems versus legacy infrastructure, and a fresh culture versus organizations still dealing with the fallout of 2008. In that moment, “new” wasn’t risky—it was the point.

You can hear the era’s pitch in how competitors framed their own entry: “Essent is well-positioned to enter the market for primary mortgage insurance, which has historically played a critical role in helping Americans achieve homeownership. Along with new, private capital, Essent will offer lenders, mortgage investors, and other market participants a risk management approach tailored specifically to meet the challenges of today's mortgage banking industry.”

Over time, though, that advantage dulled. Incumbents rebuilt capital, modernized technology, and repaired relationships. What once felt like a structural edge became more like table stakes.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

For lenders, switching MI providers isn’t a one-click decision. There’s integration work, training, workflow changes, and all the small frictions that come with moving a core piece of the mortgage process.

But lenders rarely go all-in on a single insurer. Most spread volume across multiple MIs, which means no one provider truly “owns” the relationship. The switching costs are real, but they’re procedural rather than structural.

Branding: WEAK

To borrowers, the MI company is basically invisible. Most homeowners couldn’t name who insures their loan, and they don’t choose the provider anyway.

Lenders care about reliability and service, but brand alone doesn’t win the business. Trust matters, but it’s earned more through execution than advertising.

Cornered Resource: NONE

NMI doesn’t have a cornered resource in the classic sense. There’s no proprietary dataset nobody else can access, no irreplaceable pool of talent, no technology advantage that can’t be rebuilt.

Capital is generally available to qualified players. The real scarcity isn’t the inputs—it’s the ability to clear the regulatory and approval hurdles to even enter the market.

Process Power: MODERATE

Process is where the real differentiation lives. Underwriting judgment, risk models, and operational discipline matter, and years of claims experience create a learning curve competitors can’t instantly buy.

NMI’s service culture and technology capabilities are genuine advantages in day-to-day competition. But they’re not magic. Process power is defensible, just not permanent—it can be matched, given enough time and commitment.

Summary: Limited Moats

The clean takeaway is that NMI sits in a good business, not a great one, under Hamilton Helmer’s framework. Regulatory barriers create an oligopoly, but inside that club, rivalry is real and advantages are hard-won.

The company can generate attractive returns on equity, but those returns aren’t protected by a structural moat that keeps competitors from coming after the same lender relationships and the same loans.

XIV. Strategic Inflection Points & Future Scenarios

Everything, in the near term, comes back to one question: when do rates normalize enough for the purchase market to thaw?

The problem is that “normalize” isn’t a date on the calendar. It’s a moving target tied to inflation, Federal Reserve policy, and how long households can tolerate today’s monthly payments. Mortgage rates whipsawed in 2023, with the average 30-year fixed rate swinging from the low 6% range to the high 7% range, according to Freddie Mac. That band tightened in 2024, and tightened again in 2025—but it’s still an elevated world, and the market remains sensitive to every new data point.

Meanwhile, the demand story hasn’t gone away. If anything, it’s been delayed.

Demographics are pushing in one direction even as affordability pushes in the other. The median age of a first-time homebuyer climbed to 40 in 2025, the highest on record and a sharp jump from 2014. That isn’t just a lifestyle choice; it’s what happens when a massive cohort of millennial and Gen Z buyers wants to buy but can’t make the math work. If rates settle and inventory improves, that backlog doesn’t disappear—it comes off the sidelines, and it can come fast.

That’s where the affordability crisis becomes both the biggest risk and the biggest source of relevance for mortgage insurance.

On one hand, homeownership has become increasingly unaffordable nationally since the pandemic. As of July 2025, the annual cost of owning a median-priced U.S. home consumed 47% of median household income, topping prior peaks before the 2008 financial crisis. In that environment, PMI can feel like one more fee piled onto buyers who are already stretched.

On the other hand, PMI is also the mechanism that makes homeownership possible for households who can afford the monthly payment but can’t produce a 20% down payment on top of closing costs. If the market’s path back to “normal” involves more first-time buyers scraping together what they can, mortgage insurance stays central—unloved, invisible, but necessary.

There’s also the industry chessboard to consider. Consolidation is always the rumored next move. Could private mortgage insurance go from six players down to four or five? The scale advantages are real, and private equity has long been interested in the sector’s cash-generation once a book matures. But it’s not a simple roll-up business. Between regulatory oversight and the system-level desire to preserve competition among insurers, getting a deal approved could be as hard as financing it.

And then there’s the risk that doesn’t fit neatly into historical models: climate.

A recent report estimated extreme weather events cost the global economy more than $2 trillion over the last decade. Even in years that start quietly—like 2024’s relatively calm early hurricane season—single events can dominate the ledger. Hurricanes Helene and Milton, with an estimated $55 billion in losses, were a reminder of how quickly “tail risk” becomes real. Mortgage insurers don’t take the direct property-loss hit, but they do carry concentrated exposure to specific geographies. If climate events drive local economic damage and, crucially, sharp home price declines, claims can rise—fast—because mortgage insurance risk is ultimately tied to what a home is worth when a loan goes bad.

Put it all together and the next era for NMI—and for the whole MI oligopoly—looks like a test of patience and positioning. Rates decide the pace. Demographics decide the ceiling. Policy and consolidation decide the structure. And climate decides whether the tails are getting heavier.

XV. Bull vs Bear Case

Bull Case:

The simplest bull case starts with structure. Private mortgage insurance is an oligopoly: six players, massive barriers to entry, and a regulatory framework that forces the industry to carry real capital. In a market like that, competition can be intense without becoming suicidal, and pricing tends to stay more rational than people expect.

Then there’s the demand backdrop. The U.S. is still living with the consequences of years of underbuilding, and tight inventory keeps pressure on would-be buyers. In March 2024, just 1.1 million homes were available for purchase—down 34 percent from March 2019—equal to about 3.2 months of supply even with a slowed sales pace. Annual home sales fell 19 percent in 2023 to a nearly 30-year low. The point isn’t the exact figures; it’s that the shortage looks structural, not cyclical.

That matters because a constrained, unaffordable market doesn’t eliminate demand—it changes how people buy. When buyers can’t produce 20% down, they lean on low-down-payment conventional mortgages. And that keeps PMI central, even if it’s invisible and unpopular.

Finally, there’s the “when rates normalize” kicker. If and when mortgage rates ease, housing transactions should thaw, and new insurance written should rise with them. Meanwhile, the existing book keeps generating cash even in a slow origination environment. NMI also has a strong case on execution: management navigated both the pandemic and the rate shock, and 2024 was a record year—$365,600,000 of adjusted net income, adjusted EPS of $4.5, and a 17.6% adjusted return on equity.

Bear Case:

The bear case is that none of this is truly protected. Within the six-player club, the product is close to a commodity. Regulatory barriers keep new entrants out, but they don’t stop the existing players from competing hard for the same lender allocations. That competitive pressure can cap returns, especially when the overall origination market shrinks and everyone fights over a smaller pie.

The business is also brutally sensitive to macro conditions—rates, unemployment, and home prices. According to the National Association of Realtors, sales of previously owned homes were 4.06 million in 2024, the lowest since 1995, and the third straight year of sharp declines from 2021, when 6.1 million homes were sold. Since existing-home sales represent most of the U.S. market, a prolonged slump limits new opportunity for mortgage insurers.

And the tail risk never goes away. Another housing crash would be devastating, full stop. The last crisis showed these companies can fail under severe stress. On top of that, NMI is smaller than the biggest incumbents, and scale matters in distribution, pricing leverage, and operating efficiency.

There’s also the constant substitute in the room: FHA, especially for lower-income borrowers. And the regulatory chessboard is always a risk—changes to capital requirements or coverage rules could reshape the economics quickly.

What to Monitor:

Two metrics matter most for tracking NMI's ongoing performance:

-

Insurance-in-Force (IIF) growth: This is the stock that determines future premium revenue. Whether IIF is growing or shrinking tells you more about the company's trajectory than any other single number.

-

Persistency rate: How long policies stay on the books determines the economic value of the portfolio. Higher persistency means more premium collection from existing policies. Monitor for signs that refinancing activity is accelerating and eroding the book.

XVI. Playbook: Lessons for Founders & Investors

Timing isn’t everything—but thesis is. NMI launched when the sector looked radioactive. That wasn’t reckless. It was a deliberate bet that crisis conditions create openings—because incumbents are distracted, trust is broken, and customers are willing to try something new if it feels safer. Starting in a boom would’ve meant fighting entrenched players at full strength. Starting in the bust meant building for the recovery.

Regulatory moats are real. In private mortgage insurance, the barriers—major upfront capital, GSE approval, and licensing across all the states—aren’t quirks of the system. They are the system. If you can clear them, you enter a club that is structurally protected from a flood of new competitors.

Clean slate advantage matters. Legacy is often framed as “experience.” In turnaround industries, it can be dead weight. NMI got to build modern systems without ripping out decades of tech debt. It got to write business without carrying a minefield of crisis-era losses. In this case, starting from zero was an asset.

Distribution is destiny. Great underwriting and slick technology don’t matter if lenders won’t send you loans. NMI treated distribution like the main product: earn a lender’s trust, integrate cleanly, respond fast, and then expand the relationship over time. In this business, the borrower pays—but the lender chooses.

Capital requirements can be competitive advantage. In most markets, needing more capital is a problem. Here, it’s a filter. NMI raised $550 million because they needed it to be credible—and because they knew it would keep most would-be entrants from even trying.

Cyclicality requires patience. Mortgage insurance doesn’t reveal itself quarter to quarter. It reveals itself vintage by vintage. The value shows up as books season, persist, and mature into high-margin cash generation. If you demand smooth GAAP results every quarter, this industry will disappoint you. If you can think in cycles, you can see compounding happening long before it shows up cleanly in the headline numbers.

Market misunderstanding creates opportunity. MI is full of dynamics that are easy to miss: persistency can matter more than new production, losses can emerge slowly, and NIW and IIF tell different stories about where earnings are headed. That complexity pushes casual investors away—and rewards the ones willing to actually learn how the machine works.

XVII. Epilogue: Where Are They Now?

NMI Holdings entered 2026 as what its founders were trying to build all along: a mature, consistently profitable public company, with a market capitalization approaching $3 billion. Along the way, the stock touched new highs—closing at an all-time high of 43.15 on July 3, 2025, with a 52-week high of 43.20.

The leadership team has shifted from the founding chapter into the “run it well” chapter. Adam Pollitzer, President and Chief Executive Officer of National MI, joined the company in 2017 and served as Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer from 2017 to 2021 before moving into the top job. Bradley Shuster, the founder, remains Executive Chairman—still in the room, still providing continuity and strategic guidance—while the next generation runs the day-to-day.

And the numbers in 2025 showed why the model works when it’s built correctly. For the first quarter ended March 31, 2025, NMI Holdings reported net income of $102.6 million, or $1.28 per diluted share, up from $86.2 million, or $1.07 per diluted share, in the fourth quarter of 2024, and $89.0 million, or $1.08 per diluted share, in the first quarter of 2024.

This is exactly what you’d want to see from a company founded on a simple thesis: write high-quality business, protect the balance sheet, and let time do the compounding.

Operationally, the engine kept turning. Primary insurance-in-force stood at $218.4 billion. Net premiums earned were $151.3 million, and total revenue was $178.7 million. Book value per share excluding unrealized gains reached $33.32, up 16% year over year.

Of course, the world around them still looked messy. Interest rates had come down from their peaks, but they were still high by historical standards. Home prices stayed elevated, affordability remained stretched, and first-time buyers continued to feel boxed out. As Daryl Fairweather, chief economist at Redfin, put it: “2025 was a year of stagnation. High mortgage rates—averaging about 6.6 percent—kept buyers on the sidelines, while sellers with low rates and plenty of equity largely chose to wait, keeping sales stuck around 4.1 million. The market was largely frozen.”

So what does “success” look like from here? Not hypergrowth—that’s not how mortgage insurance works once you’re established. It looks like steady compounding: growing insurance-in-force, staying consistently profitable, returning capital with discipline through share repurchases, and positioning patiently for whenever the housing cycle finally turns back up.

And the “hidden giant” paradox remains the perfect ending. NMI Holdings, Inc. is a U.S.-based private mortgage insurance company that helps low down payment borrowers achieve home ownership while protecting lenders and investors from losses tied to borrower default. It sits behind billions of dollars of mortgages—yet has essentially zero consumer awareness.

From a crisis-era startup to a billion-dollar public company in a little over a decade. No celebrity founders. No consumer brand. No flash. Just a hard, unglamorous kind of execution: identify the opening, raise the capital, earn the trust, and keep the machine humming—one policy at a time.

XVIII. Further Reading & Resources

Primary Sources: - NMI Holdings Investor Relations (ir.nationalmi.com) — The cleanest, most direct way to follow the story in NMI’s own words: annual reports, quarterly filings, and investor presentations - FHFA PMIERs Documentation — The rulebook that defines who gets to play in private MI, and on what terms - U.S. Mortgage Insurers (USMI) publications — Industry research and commentary on mortgage insurance’s role in the housing finance system

Academic & Policy Research: - Urban Institute Housing Finance Policy Center — Deep, data-driven work on mortgage finance, affordability, and where MI fits - "Moral Hazard during the Housing Boom: Evidence from Private Mortgage Insurance" (Bhutta and Keys) — A sharp look at how incentives warped behavior in the run-up to the crisis - Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies annual reports — The broader backdrop: affordability, household formation, and the structural forces shaping housing demand

Industry Analysis: - KBW (Keefe, Bruyette & Woods) equity research on mortgage insurers — Sector-focused analyst coverage that helps translate MI economics into investor language - National Mortgage News coverage of quarterly industry results — A practical way to track market share moves, pricing commentary, and competitive shifts as they happen

Historical Context: - "Guaranteed to Fail" by Viral Acharya et al — A useful lens on the GSE system and the incentives that shaped modern housing finance - Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission Report — The definitive timeline and source material for how the 2008 crisis unfolded, including the role of mortgage credit and risk transfer

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music