National Fuel Gas: A Century of Integrated Energy in Appalachia

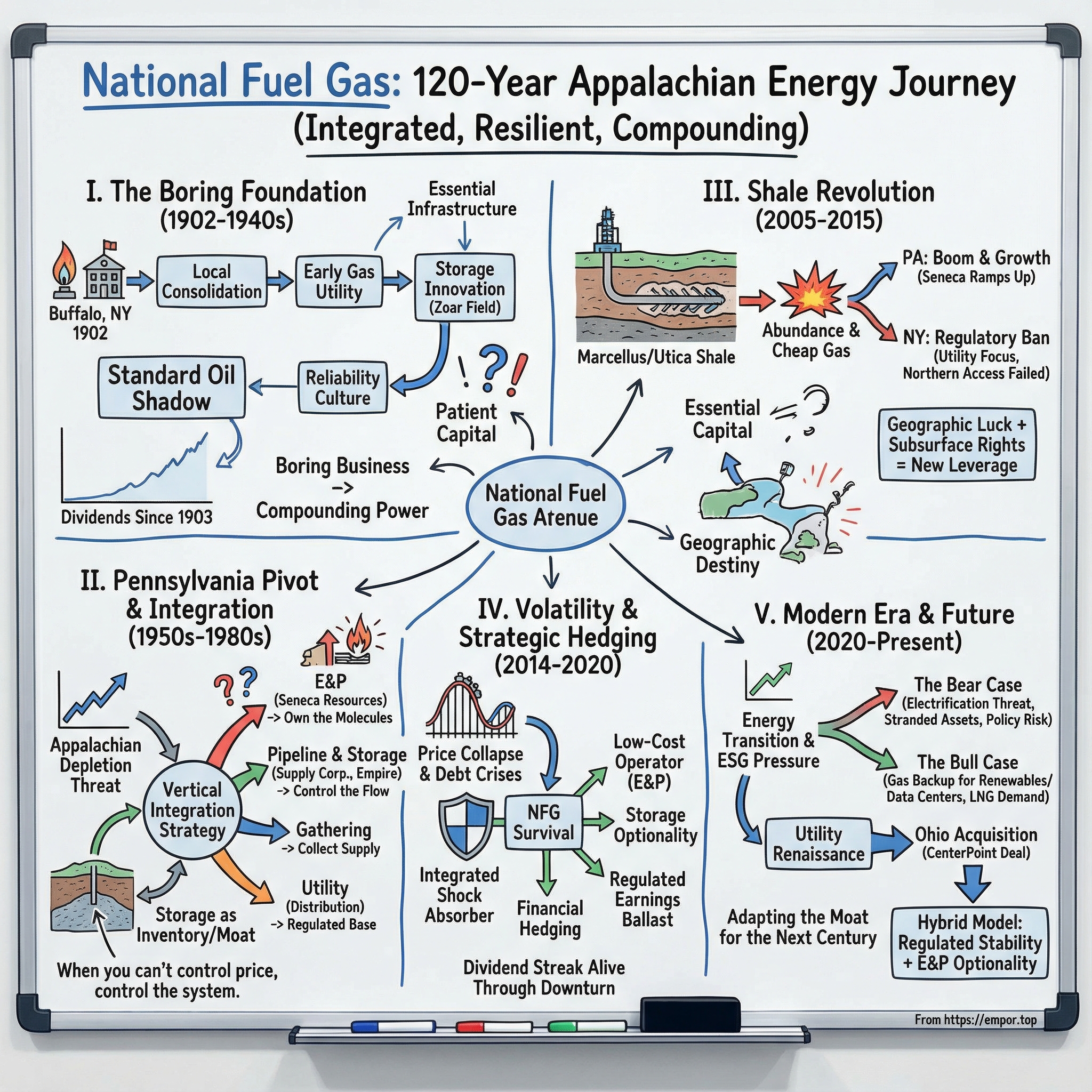

I. Introduction: The Boring Business That Keeps Compounding

Picture a bitter January night in Buffalo. The temperature drops below zero, wind knifes off Lake Erie, and across Western New York, hundreds of thousands of homes crank up their furnaces without thinking twice. Heat just shows up. No drama, no decisions.

Behind that quiet reliability is a company most people have never heard of—one that’s been doing essentially the same job, in the same region, for more than 120 years.

National Fuel Gas was incorporated in 1902 and is based in Williamsville, New York. It started as a consolidation of small Buffalo-area gas distributors. Over the decades, it evolved into something that’s become genuinely rare in American energy: a vertically integrated natural gas company. NFG’s business spans five operating segments—Exploration and Production, Pipeline and Storage, Gathering, Utility, and Energy Marketing—with $6.2 billion in assets spread across that system.

The simplest way to understand NFG is the line the company itself could have written decades ago: “We find it, pipe it, store it, and sell it.” They drill wells in Pennsylvania, move the gas through their own pipes, tuck it away underground for later, and deliver it to homes and businesses—sometimes all within a few hundred miles. It’s one of the last full, end-to-end natural gas operations still standing at meaningful scale in the U.S.

Which brings us to the real question. How did a small Buffalo gas company survive Standard Oil’s era, two world wars, the rise of utility regulation, commodity price collapses, and the shale revolution—then come out the other side as one of America’s steadiest dividend machines? National Fuel has paid dividends for 123 consecutive years and increased its annual dividend for 55 straight years, placing it among the Dividend Kings: the tiny set of companies that have raised payouts for at least half a century.

This story matters because NFG is a living case study in something modern business culture tends to ignore: the power of essential infrastructure, local monopolies, and patient integration. It sits in the crossfire of today’s biggest energy debates—electrification, infrastructure buildout, energy security, and the tension between ESG pressure and the reality that people still need heat in January. And it’s also a reminder that geography can be destiny. The Marcellus Shale didn’t just appear under NFG’s footprint; the company spent a century building a system in exactly the place where the next energy jackpot would eventually be found.

The themes that keep showing up: integration as a moat, subsurface rights as a strategic weapon, and regulation not as a burden but as an arena you can learn to win. Most of all, it’s the idea that “boring” businesses can produce extraordinary outcomes—if they keep showing up, keep compounding, and don’t break when the world changes around them.

II. Founding Context and the Early Gas Wars (1902–1940s)

National Fuel Gas didn’t start with a grand strategy deck. It started with geology, accidents, and a region that was learning—messily—what “energy” even meant.

To see why, rewind to the mid-1800s, when upstate New York and Western Pennsylvania sat on the front edge of America’s first oil-and-gas boom. In 1863, during the Civil War, oil was discovered in Titusville, Pennsylvania—close enough to ripple through every town with a drill rig and a dream.

Not long after, a group of investors in Bloomfield, New York, tried their luck. The contractor they hired struck gas at about 480 feet. It blew off so forcefully that work stopped for weeks. They pushed to roughly 500 feet, found no oil, and walked away.

And then they did something that sounds insane now but made perfect sense then: they set the well on fire. At the time, gas was mostly viewed as a nuisance—an unwanted by-product of searching for oil. That well burned until 1870, when another group bought it and, crucially, treated the gas not as waste, but as a product.

That shift in mindset—gas isn’t the problem, it’s the business—helped spark one of America’s earliest utility plays. Those investors built a pipeline out of bored pine logs, banded together with iron, to supply Rochester, New York, with gas for street and residential lighting. It was crude infrastructure by modern standards, but the idea was sophisticated: take a resource from where it sits and turn it into everyday reliability in a growing city.

By the early 1900s, demand had expanded well beyond streetlamps. Natural gas was proving itself as a flexible fuel for cooking, heating water, heating homes, and lighting. Communities built their own small gas systems to serve local customers. The problem was that these systems were only as good as their nearby wells. When production fell off—or when the town grew faster than the wells could support—everything got shaky. Supply shortfalls weren’t hypothetical. They were the defining failure mode of early gas utilities.

That’s the backdrop for 1902. On December 8 of that year, National Fuel Gas Company was incorporated—formed to coordinate Buffalo-area interests along with natural gas investments in Western Pennsylvania that had been placed inside John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Natural Gas Trust. That Rockefeller connection cut both ways. It brought capital and operational experience, but it also meant living under the shadow of Standard Oil’s power and the political backlash that power attracted.

Even in these early years, you can see the DNA of what NFG would become: not just a distributor, but a builder of systems.

One example stands out. A predecessor to National Fuel Gas Supply Corporation developed the first underground natural gas storage reservoir in the United States at Zoar Field, about 40 miles south of Buffalo. The breakthrough was deceptively simple: depleted gas fields could be converted into storage reservoirs. Instead of treating an “empty” field as the end of the story, engineers turned it into a reusable asset.

That storage innovation became a strategic advantage as demand surged in the 1940s and 1950s, when pipelines across the East increasingly connected to new pipelines and fields in the Southwest. With storage in Western New York, NFG could buy large volumes of cheaper summer gas from the Southwest, transport it north, inject it underground, and pull it back out when winter demand—and prices—rose.

This wasn’t just clever trading. It was an early form of inventory control in an industry where “inventory” is normally impossible. And it planted a theme that will keep returning in this story: when you can’t control the commodity price, you build advantages in everything around it.

Through the Great Depression and World War II, that utility model delivered stability. While many industrial businesses whipsawed with economic collapse and wartime disruption, regulated utilities operated under a rate-of-return framework that created a floor under profitability. NFG’s early decades didn’t produce flashy reinvention—they produced something rarer: consistency.

From the beginning, the company’s playbook was taking shape. Expand carefully within a defined territory. Invest in infrastructure that lasts. Manage conservatively. Keep the service reliable. And let time do the heavy lifting.

III. The Pennsylvania Pivot and Supply Chain Strategy (1950s–1980s)

By mid-century, National Fuel Gas ran into a problem that every early gas utility eventually faced: the wells that built the franchise were fading. The shallow Appalachian supply that had fed Buffalo and the surrounding region for decades was depleting. And for a company whose entire promise was “the gas will be there when you turn the knob,” that wasn’t a slow-moving inconvenience. It was an existential threat.

NFG’s answer set the course for the next several decades: stop being just a buyer of gas, and start being an owner of it. Instead of relying on outside producers for the one input the whole system depends on, NFG chose backward integration into exploration and production.

In 1952, it formed Seneca Resources to drill for and produce oil and gas. The point wasn’t to become a swashbuckling wildcatter; it was to lock down supply. Seneca gave NFG a way to secure volumes on its own terms rather than shopping the market whenever shortages hit.

That move put NFG on a very different path than most gas distribution companies. The standard utility model was straightforward: buy gas from producers, move it through pipelines that were often owned by someone else, then sell it to captive customers under regulated rates. It worked—until it didn’t. NFG’s leadership saw the fragility: if you don’t control supply, you’re only as reliable as the people you buy from.

Over the 1960s and 1970s, Seneca expanded across Pennsylvania’s traditional oil and gas regions, acquiring mineral rights and drilling into the kind of steady, workmanlike production that could keep a utility fed. For a time, Seneca also stepped outside Appalachia, establishing West Coast operations by acquiring a 75% interest in Argo Petroleum Corporation’s principal oil and gas properties in California. That diversification would later be unwound, but it said something important about the culture: NFG was willing to go where the molecules were, not just where the headquarters sat.

At the same time, the company kept building the rest of the chain around that supply. The 1970s and 1980s brought more midstream muscle, including the formation of National Fuel Gas Supply Corporation for interstate pipeline operations and the acquisition of Empire Pipeline. Empire mattered because it was connective tissue—linking production areas to the distribution system and turning NFG’s upstream ambitions into delivered, usable gas.

And hovering over all of this was the quiet superpower NFG had already started to accumulate: storage.

The storage play kept getting better as the broader U.S. gas market matured. As demand surged and new supplies from the Southwest began flowing into the East, NFG’s Western New York storage fields gave it a practical and financial edge. It could buy cheaper gas in the summer, move it north, inject it underground, and pull it back out when winter demand—and prices—spiked.

In natural gas, that’s as close as you get to having inventory on a shelf.

Underground storage isn’t something you can just decide to build anywhere. It depends on geology, and the industry relies on a few types of formations: depleted hydrocarbon reservoirs, aquifer reservoirs, and solution-mined salt caverns. Depleted reservoirs are the workhorse of the system, representing about 80 percent of total U.S. working gas capacity.

That detail matters because it highlights why NFG’s early bets compounded. Pipelines can be expanded—painfully, slowly, and with lots of paperwork—but the right rock formations are finite. You can’t manufacture them. So every storage field NFG developed wasn’t just an operating asset; it was a cornered resource.

Then the rules of the game started changing.

The Natural Gas Policy Act of 1978 kicked off the long march toward deregulation. For much of the industry, this era brought disruption: contract structures broke, pricing dynamics shifted, and the market went through waves of restructuring. For NFG, the turbulence created openings. With production, pipelines, storage, and distribution under one umbrella, it could move gas between segments, optimize across the system, and take advantage of dislocations that would have hit a single-segment company much harder.

By the 1980s, the shape of the modern NFG was largely in place: E&P through Seneca, connected to gathering, flowing into pipelines like Empire and National Fuel Gas Supply Corporation, supported by storage, and delivered through the utility to customers. Most utilities were still essentially buyers and resellers. NFG had built a full value chain from wellhead to burner tip.

The takeaway from this period is simple: in a commodity business where you can’t control price, control what you can. Vertical integration doesn’t eliminate volatility, but it changes how volatility hits you. When gas prices fall, production suffers but distribution benefits from cheaper supply. When prices rise, the upstream segment can thrive even as the utility side tightens. NFG wasn’t trying to predict the cycle. It was building a structure designed to survive it.

IV. The Shale Revolution: From Threat to Tailwind (2005–2015)

The Inflection Point

In 2004, a single well in Washington County, Pennsylvania helped flip American natural gas from “scarce and expensive” to “abundant and cheap.” And for National Fuel Gas, it turned out to be one of the most fortuitous shifts the company could have asked for.

In October 2004, Range Resources completed the Renz Unit 1 well in Mount Pleasant Township using a Barnett Shale-style slick-water hydraulic fracturing treatment. That completion produced the kind of results that make an industry lean in: suddenly, the Marcellus wasn’t just a line on a geologist’s map. It looked like a commercial resource.

The irony is that the Marcellus Shale had been hiding in plain sight for a long time. It’s a roughly 390-million-year-old formation that underlies large portions of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, reaches into eastern Ohio, and extends into southern New York. It’s organic-rich source rock—but also extremely fine-grained, with very low permeability. For decades, that low permeability was the whole story: the gas was there, but you couldn’t get it out at meaningful rates. So the Marcellus was dismissed as an impractical target.

Then the technology and the economics caught up. Before long, the Marcellus went from “inconsequential potential” to what is now believed to be the largest volume of recoverable natural gas in the United States. Virtually overnight, it shifted from geological curiosity to world-class resource.

By 2008, the land rush was on—especially in Pennsylvania. Leasing agents moved fast, and lease prices jumped sharply in just a few months. Drilling ramped just as aggressively: Pennsylvania went from only a handful of Marcellus wells in 2005 to well over a thousand by 2010.

For NFG, this wasn’t an abstract boom happening somewhere else. The Marcellus sat directly beneath the company’s footprint—and, critically, beneath its infrastructure. NFG already owned mineral rights in north-central Pennsylvania. Seneca Resources had been drilling in the region for decades and had a deep working understanding of the local geology. In 2007, Seneca launched its Marcellus Shale program by drilling a network of exploration and test wells across its acreage.

In other words: while much of the industry was scrambling to assemble positions, NFG already had a seat at the table.

Execution and Transformation

From 2008 through 2012, NFG didn’t dabble. It pivoted hard into shale development. Seneca ramped investment in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing—the two technologies that made shale gas work at scale. The basic problem was always permeability: gas doesn’t flow easily through shale. Hydraulic fracturing creates pathways in the rock so the gas can move, and horizontal drilling lets operators expose far more of the formation than a traditional vertical well ever could. Put them together, and a “nonproductive” source rock becomes a factory.

As Seneca’s program accelerated, the business changed shape. NFG went from a company worried about sourcing gas to a company sitting on top of one of the most important gas plays on earth. Production rose year after year, and Seneca became a meaningful producer in the Appalachian Basin.

But NFG’s geography came with a twist. The Marcellus footprint crossed a political border, and Pennsylvania and New York made very different choices.

On December 17, 2014, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a statewide ban on high-volume hydraulic fracturing, formalizing a moratorium that had effectively been in place since 2008. New York became the first state with known gas reserves to prohibit extraction using fracking, following a statewide health investigation that concluded the practice could release toxic pollutants into air and drinking water.

For NFG—straddling the New York–Pennsylvania line—this created a real strategic complication. A significant portion of its distribution customers were in New York, where fracking was banned. Its production growth, meanwhile, was in Pennsylvania, where shale development was welcomed. The company now had major assets living under fundamentally different regulatory regimes.

NFG’s response was practical: keep running the New York utility like the steady franchise it had always been, and lean into Pennsylvania for growth. Seneca remained focused on developing natural gas in Appalachia, concentrating its drilling in the Marcellus and Utica shales in Pennsylvania, where it controlled approximately 1.2 million net prospective acres.

The financial shift was just as significant as the operational one. Exploration and production, once a modest contributor, became a major earnings engine. Over time, the upstream segment generated about 48% of total EBITDA, with natural gas making up roughly 90% of output.

And yet, the market was slow to update its mental model. NFG still traded like a sleepy utility, even as it increasingly looked like an integrated company with real shale leverage. Investors gravitated to cleaner labels—pure-play E&P names like Chesapeake and Range Resources, or pure midstream giants like Williams and Kinder Morgan. NFG’s integrated structure—neither fish nor fowl—was easy to overlook.

But that was the story’s punchline: geographic luck, paired with owned subsurface rights and an already-built network of pipes and storage, created a compounding advantage that didn’t show up in the stock’s narrative for years.

V. The Commodity Price Rollercoaster and Strategic Hedging (2014–2020)

The shale revolution delivered abundance—so much of it that the industry tripped over its own success. As volumes poured out of the Marcellus and other shale basins, natural gas prices fell hard. Between 2014 and 2016, NYMEX natural gas slid from above $6 per MMBtu to below $2, wrecking the economics for producers across the country.

The carnage was real. Many pure-play E&P companies had borrowed aggressively to fund drilling, assuming strong prices would stick around. When they didn’t, the debt didn’t go away—it just got heavier. Chesapeake Energy, once the face of the shale boom, eventually filed for bankruptcy in 2020. Plenty of smaller operators never made it to the other side.

National Fuel Gas did. And the reason wasn’t luck. It was structure.

First, the integrated model acted like a shock absorber. Seneca’s wells took the hit when prices collapsed, but the rest of the system kept humming. The utility and pipeline businesses still generated steady cash flow, giving NFG something most producers don’t have in a downturn: a stabilizing base underneath the volatile part of the portfolio.

Second, Seneca was positioned as a low-cost operator. Its Marcellus acreage sat in a core area, and it was close to existing infrastructure. In a commodity business, that cost position is survival. The producers with the best rock and the shortest path to a pipe can keep drilling when everyone else is forced to retreat.

Third, NFG stayed financially conservative. Unlike levered E&P peers that were effectively making an all-in bet on higher prices, NFG kept more flexibility. It also managed its dividend with that reality in mind, targeting a conservative payout ratio of around 50%. That margin of safety mattered—because when the cycle turns, dividends aren’t protected by optimism. They’re protected by cash flow and balance sheet room.

Fourth, storage created optionality. If you own storage, you’re not always forced to sell the moment the molecules come out of the ground. You can inject gas and wait. That kind of “inventory” flexibility is rare in this business, and it functions as a form of natural hedging when markets are ugly.

On top of the physical advantages, NFG leaned into financial hedging. The company used derivatives and contract structures to reduce exposure to short-term swings and protect the dividend. Seneca also lined up firm sales commitments: about 88% of its expected fiscal 2025 natural gas production was under firm sales contracts, and roughly 60% was supported by financial hedges or fixed-price contracts—enough downside protection to stay steady, without completely giving up upside.

But prices weren’t the only problem. Moving gas out of Appalachia—and into better-paying markets—became its own battle.

NFG’s answer was the Northern Access Pipeline project: roughly 100 miles of new pipe intended to move Pennsylvania gas into New York and beyond. The proposal ran from Sergeant Township, Pennsylvania to the Porterville compressor station near Elma, New York, designed to provide 500 MMcf/d of transportation capacity, with potential deliveries into Empire Pipeline and Tennessee Gas Pipeline.

Then it collided with New York’s regulatory reality.

Northern Access became a years-long fight, centered on a crucial water quality certification. A major turning point came when a federal appeals court backed FERC’s view that the New York Department of Environmental Conservation had waived its authority by failing to act within the Clean Water Act’s one-year deadline. NFG celebrated the ruling, calling it the clearing of “the most significant hurdle” to moving the project forward.

And yet, even with that legal win, the project never became a physical one. After years of litigation, delays, and rising costs, NFG pulled the plug. In the company’s words, it “never put shovels in the ground.” Nearly a decade in, ballooning expected costs and the continued difficulty of building pipelines in New York led management to stop development efforts.

Through all of this—crashing prices, industry shakeouts, and a marquee pipeline that died in regulatory gridlock—NFG made one decision that anchored the whole era: it kept the dividend growth streak alive. While many energy companies cut payouts after the 2014–2016 collapse, National Fuel Gas continued raising its dividend.

That commitment did more than reward shareholders. It broadcast confidence in the model, attracted a stable base of income-focused investors, and imposed discipline on management. Because a dividend you keep growing through a commodity downturn isn’t a slogan.

It’s proof you built the business to survive the cycle.

VI. Modern Era: Energy Transition, ESG, and Utility Renaissance (2020–Present)

The COVID Shock and Recovery

COVID delivered another demand shock to natural gas, but it wasn’t a simple “everything down” story. Commercial and industrial loads fell off a cliff as offices and factories went quiet. At the same time, the utility side held up—people were home all day, heating and cooking more, and the residential meter kept spinning.

Once again, NFG’s integrated model did what it was built to do: keep the company steady when one part of the system gets hit.

In June 2020, the board approved a 2.3 percent dividend increase. That made National Fuel’s streak even more striking: dividends paid for 118 consecutive years, and 50 straight years of annual increases. In a year when “uncertainty” became a daily headline, they raised the dividend anyway.

Then, in the middle of that chaos, NFG made a move that looked almost counterintuitive: it completed the largest acquisition in its history.

National Fuel Gas bought integrated upstream and midstream gathering assets in Pennsylvania from SWEPI LP, a subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell plc, in an all-cash deal of approximately $504 million, after customary purchase price adjustments. CEO David P. Bauer called it “the largest acquisition in our 118-year history” and said it left the company “well-positioned for the long-term.”

What did NFG get? About 450,000 net leasehold acres in Pennsylvania, roughly 350 producing Marcellus and Utica wells in Tioga County, and the associated facilities to gather and move that gas.

The timing worked in NFG’s favor. Shell was stepping back from Appalachian gas as it shifted toward higher-margin light tight oil. NFG was doing the opposite—doubling down in a basin it knew cold. And because the assets were contiguous with NFG’s existing footprint, the deal wasn’t just “more acreage.” It was operationally practical, with cost synergies that could show up quickly.

Then the market turned.

The energy crisis of 2021–2022—driven by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—sent global energy prices surging. Europe’s natural gas prices spiked to extraordinary levels, and U.S. LNG exports rose to meet the moment. For years, Appalachian gas had been trapped behind infrastructure constraints and forced to sell at discounts. Suddenly, molecules from Pennsylvania looked a lot more valuable.

Seneca felt that change immediately. In the third quarter, Seneca’s adjusted operating results increased $52.9 million, primarily from higher realized natural gas prices and higher production, along with lower per-unit operating expenses. That same quarter, Seneca produced a company record 112 Bcf of natural gas—up 15 Bcf, or 16%, from the prior year.

The Energy Transition Paradox

By the early 2020s, NFG wasn’t just riding cycles anymore. It was operating inside a political and cultural argument: what role, if any, should natural gas play in a decarbonizing economy?

The bear case is simple and loud. Natural gas is a fossil fuel. Climate policy is getting tougher. New York has already banned fracking and has considered restrictions on gas hookups in new construction. And there’s a thornier second-order effect: if electrification happens in an uncoordinated way while gas infrastructure costs remain, the people left on the gas system can end up paying more—raising real affordability and equity concerns in the messy middle of the transition.

The substitute is no longer hypothetical. Building decarbonization is increasingly driven by real-estate investors with net-zero targets, policymakers setting emissions limits, and tenants demanding greener buildings. Electrifying space and water heating is one of the clearest levers available, and heat pumps—better than they used to be, and in some markets cost-competitive—have become the poster child for that shift.

But the bull case still has weight. Natural gas has continued displacing coal in power generation, which has been the single largest driver of U.S. emissions reductions over the past fifteen years. Wind and solar bring intermittency; the grid still needs fast, reliable backup, and gas turbines ramp in a way few alternatives can. And now there’s a new demand engine: data centers, which want enormous amounts of dependable power.

NFG’s stance has been measured. It points to Seneca’s ability to develop low-cost, low-emissions-intensity reserves, and to the Appalachian Basin’s relatively low greenhouse gas and methane intensities compared with many other regions. It isn’t trying to reinvent itself overnight or lead with sweeping pledges. Management’s approach is closer to: keep the machine running, improve it where you can, and look for adjacent opportunities like renewable natural gas.

And in October 2025, NFG signaled that “utility renaissance” wasn’t just a phrase. It announced a definitive agreement with CenterPoint Energy Resources Corp. to acquire CenterPoint’s Ohio natural gas utility business.

National Fuel is acquiring the equity interests in CNP Ohio for total consideration of $2.62 billion on a cash-free, debt-free basis, subject to customary closing adjustments—an acquisition multiple of approximately 1.6x estimated 2026 rate base of $1.6 billion.

If it closes, NFG also picks up the team that runs the system: approximately 5,900 miles of distribution and transmission pipeline serving about 335,000 customers across residential, commercial, industrial, and transportation classes—customers that consume roughly 60 Bcf of natural gas per year.

Strategically, the direction is clear. This deal, pending regulatory approval, would meaningfully expand NFG’s regulated utility base and shrink the company’s reliance on the more volatile E&P earnings stream. In NFG’s framing, it would effectively double the gas utility rate base to approximately $3.2 billion and expand the customer base to around 1.1 million across New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.

In a world where commodity exposure is a feature in good times and a bug in bad ones, the logic is straightforward: tilt more of the business toward regulated, rate-based stability—without giving up the integrated engine that made the company durable in the first place.

VII. Business Model Deep Dive and Competitive Dynamics

The Integration Advantage

To really understand why National Fuel Gas has endured—and why it behaves differently from both utilities and producers—you have to follow the gas molecule through the system. NFG isn’t built as a collection of unrelated businesses. It’s built as a chain.

Exploration and Production (Upstream): The upstream engine is Seneca Resources Company, LLC. From its base in Houston, Seneca explores for, develops, and produces natural gas in Appalachia, including the Marcellus and Utica shales. It’s also the part of the company that feels the cycle first and hardest—because when prices move, producers feel it immediately.

By September 30, 2025, Seneca’s proved reserves were 4,981 Bcfe, up 229 Bcfe from the prior year. That increase came from Seneca replacing more than all of what it produced during fiscal 2025. At the end of fiscal 2025, proved developed reserves were 3,665 Bcfe, about three-quarters of the total proved reserves—meaning a large share of the resource base was already in the “drilled and producing” category, not just on paper.

Pipeline and Storage (Midstream): Once the gas is produced, NFG can move it through its own midstream backbone. National Fuel owns and operates nearly 2,800 miles of interstate natural gas pipelines and more than 190 compressor units across New York and Pennsylvania.

Two affiliated operators do the heavy lifting here: National Fuel Gas Supply Corporation and Empire Pipeline, Inc. Together, they provide rate-regulated interstate transportation for both affiliated and nonaffiliated customers through a system that includes 2,233 miles of pipeline and 29 underground natural gas storage fields.

Distribution (Downstream): At the end of the chain is the utility—the part customers actually experience. NFG’s Utility segment sells natural gas, or provides transportation service, to more than 754,000 customers through a local distribution system in western New York and northwestern Pennsylvania.

And then there’s the part of the system that ties the whole model together: storage.

Storage arbitrage is not a side hustle for NFG. It’s core infrastructure. Underground storage fields function like warehouses for a product that’s otherwise extremely difficult to “stock.” Gas is injected during warmer months and withdrawn during colder months, when demand spikes. Operationally, this balances loads and keeps the system reliable. Economically, it gives NFG flexibility—because it’s not always forced to buy or sell at the worst moment.

On the downstream side, the moat is regulation. Utility distribution is a local monopoly with rate-of-return regulation. There isn’t a rival pipeline on the next street over. Customers don’t switch gas utilities the way they switch cell phone plans. Rate cases set the allowed return, which makes the utility business predictable—even if it rarely looks exciting.

The Competitive Landscape

Upstream peers like EQT, Range Resources, and Coterra are essentially pure plays on gas prices. They can deliver more torque when the market is strong, but they don’t have a regulated earnings base to steady the ship when prices crash.

Midstream peers like Williams Companies and Kinder Morgan make money moving molecules. Their models tend to be more fee-based and less directly tied to commodity prices than upstream producers—but they still don’t have the same rate-regulated utility foundation that underwrites NFG’s cash flow.

Distribution peers like Atmos Energy and Spire are the opposite: classic utilities. Lower volatility, lower upside—regulated returns without the whiplash of owning a producer.

NFG is different. It’s one of the few companies that combines meaningful Marcellus/Utica production, integrated pipelines and gathering, irreplaceable underground storage, and a regulated utility—stacked on top of each other in the same region.

And the geography matters. NFG sits close to the Northeast demand center, a market that consumes enormous volumes of gas. Meanwhile, the rights-of-way for pipelines and the subsurface geology required for storage aren’t things you can easily duplicate—especially in today’s permitting environment. In a strange twist, the same forces that made Northern Access so difficult also make existing infrastructure more valuable. When it’s hard to build new pipes, the pipes you already have get more defensible.

VIII. Strategic Frameworks: Applying Porter's Five Forces and Hamilton's 7 Powers

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: LOW

In utility distribution, new entry is basically a non-starter. Franchise agreements carve up exclusive service territories, and once a utility has the pipes in the ground, there’s no practical way for a competitor to “build a second set” and win customers.

Pipelines and storage are even worse for would-be entrants. The capital is massive, and the permitting gauntlet is brutal. Northern Access was the proof: even with demand, even with a plan, getting new steel in the ground can turn into a decade-long grind.

E&P is the one area where entry is more feasible in theory—but the best Marcellus acreage has largely already been leased, and the remaining opportunities are rarely as attractive.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW to MEDIUM

Vertical integration changes the usual utility math. For the distribution business, NFG can often supply itself, which blunts supplier power right where it would normally hurt most.

Upstream, the “suppliers” look different—drilling rigs, pressure pumping crews, steel, and services. Those markets are typically fragmented, and NFG has enough scale to compete for pricing and availability.

The catch is regulation: on the utility side, higher costs can’t always be passed through to customers immediately, which creates timing risk even when long-term recovery is likely.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW (Distribution) / HIGH (E&P)

On the utility side, the buyer has almost no leverage. Customers are captive, rates are regulated, and switching providers isn’t a thing.

In E&P, it flips. Gas is sold into commodity markets, and NFG is a price taker like everyone else.

But the integrated system matters here too. NFG can “sell to itself” across the chain and capture margin in multiple places, rather than living or dying on the wellhead price alone.

Threat of Substitutes: MEDIUM to HIGH

This is the big long-term question hanging over every gas utility: what happens if heating electrifies faster than pipes can be paid for?

Heat pumps, electric resistance heating, and building electrification are real substitutes, especially as policy pushes in that direction. There’s also a serious equity issue embedded in the transition: households that don’t electrify may see meaningfully higher gas bills over time—one estimate puts the average increase at 46% over the next 15 years—as the fixed costs of the system get spread across fewer customers. Targeted electrification can reduce energy burdens, but a smooth transition likely requires coordinated, neighborhood-scale planning, not a household-by-household scramble.

At the same time, gas still has meaningful infrastructure lock-in, and today’s economics often still favor it. The pressure is also uneven: New York policy has become increasingly hostile, while other parts of NFG’s footprint are less so.

Competitive Rivalry: LOW (Distribution) / HIGH (E&P)

Distribution rivalry is effectively zero. It’s a regulated monopoly.

E&P rivalry is intense, with operators competing on acreage quality, cost structure, and access to infrastructure. Midstream sits in the middle: rivalry exists, but once infrastructure is in place, it often becomes a local oligopoly shaped by geography and rights-of-way.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Powers NFG Possesses:

Scale Economies: STRONG (Distribution & Midstream)

Pipes and compressor stations are high fixed-cost assets, and scale spreads those costs across more throughput and more customers. The storage system adds another layer: it creates opportunities—both operational and economic—that smaller players can’t easily replicate. Dense gathering systems in core Pennsylvania areas also compound efficiency.

Network Effects: WEAK

There isn’t a meaningful network effect in commodity production or in a regulated gas utility. More customers don’t make the product inherently more valuable the way they would in software or marketplaces.

Counter-Positioning: NOT APPLICABLE

NFG isn’t a challenger attacking incumbents with a new model. It is the incumbent, and it’s been building this integrated system for decades.

Switching Costs: STRONG (Distribution) / NONE (E&P)

In distribution, switching costs are effectively prohibitive. Customers would need to change appliances and reconfigure their homes, and there’s no competing gas utility to switch to anyway.

In E&P, switching costs are basically zero. Buyers can purchase the same commodity from someone else at the market price.

Branding: WEAK

In a captive utility market, branding doesn’t drive outcomes the way it does in consumer products. In E&P and pipelines, relationships matter, but the product is still molecules and capacity—price, reliability, and contracts dominate.

Cornered Resource: STRONG

This is NFG’s superpower. Mineral rights in core Marcellus and Utica areas can’t be conjured out of thin air. Pipeline rights-of-way through dense, permit-heavy regions are even harder to recreate today. And underground storage fields are the rarest of all: they depend on specific geology, and once you have them, you’re holding an asset class that can’t simply be manufactured somewhere else.

Process Power: MODERATE

A century-plus of operating experience builds real institutional knowledge—especially when you’re running both regulated and unregulated businesses under one roof. The ability to manage safety, reliability, and regulators while also operating a competitive E&P business is learned over decades. That said, process advantages help, but they aren’t invincible.

Overall Assessment: NFG’s moat is strong but bifurcated—almost unbreakable in regulated distribution and much of midstream, but fundamentally exposed to commodity forces in E&P. The integration doesn’t eliminate risk; it reshapes it, creating optionality and resilience that pure utilities and pure producers don’t have.

IX. Bull Case vs. Bear Case and Investment Analysis

The Bull Case: "Hidden Asset Value + Defensive Compounder"

The bull case starts with a simple claim: the market still tends to treat National Fuel Gas like a sleepy utility, and in doing so may underappreciate what’s sitting inside the box—real upstream assets, plus the optionality that comes from owning the chain from wellhead to customer.

The dividend record is the headline proof point. In 2024, NFG raised its dividend for the 55th consecutive year, placing it among the Dividend Kings—companies that have increased payouts for at least 50 straight years. In the energy world, that kind of consistency is almost unheard of; among the major energy companies, only Exxon Mobil and Chevron can point to comparable streaks.

Bulls also argue that Seneca’s upstream position is better than it looks at first glance. The company controls Tier-1 Marcellus and Utica acreage, with proved reserves approaching 5 Tcf, and production has reached record levels. That’s not a speculative “maybe.” It’s a demonstrated asset base that throws off real volumes.

Then there’s the energy transition argument—counterintuitive, but not crazy. Natural gas continues to displace coal in power generation. Wind and solar introduce intermittency, which increases the value of fast, reliable backup. Data centers are emerging as a meaningful new source of load growth. And LNG export growth is pulling more U.S. gas into global markets, improving the long-term demand picture for Appalachia.

Finally, bulls point to the company’s tilt toward more regulated earnings. The pending acquisition of CenterPoint’s Ohio natural gas utility business, if completed, would expand NFG’s rate-based foundation. The transaction is subject to regulatory approvals and was expected to close in the fourth quarter of 2026. CEO David P. Bauer emphasized the appeal of Ohio’s regulatory environment, the ability to reinvest free cash flow into the system, and the potential to strengthen the company’s investment-grade credit profile.

Management’s own expectations reflect that confidence. The company initiated fiscal 2025 earnings guidance of $5.75 to $6.25 per share, which it described as a meaningful step up from fiscal 2024 at the midpoint. NFG has said it expects its average annual increase in earnings per share to exceed 10% over the next three years.

The Bear Case: "Melting Ice Cube with Commodity Exposure"

The bear case begins with the uncomfortable part: NFG is still, unavoidably, a fossil fuel company. And some of its most important customers live in a state that has become openly skeptical of that future.

New York’s fracking ban is already in place, and policymakers have considered restrictions on gas in new construction. For a utility, that’s not just “headline risk.” It’s demand risk, political risk, and long-term planning risk all rolled together.

Then there’s stranded asset risk. If building codes and climate policy push electrification hard enough, the distribution system can flip from moat to burden. Pipes still need to be maintained, replaced, and monitored—even as the customer base potentially shrinks. In a harsher scenario, parts of the system could eventually require expensive decommissioning.

The other vulnerability is the one NFG can never fully escape: its E&P segment is a price taker. Commodity volatility creates earnings uncertainty, and that can bleed into dividend safety at the wrong moment. NFG has made it through downturns before, but bears argue that a sustained low-price environment, combined with faster-than-expected electrification, could stress the model in ways that past cycles did not.

And this is an inherently capital-intensive business. Pipelines age. Distribution systems require ongoing modernization. Those obligations don’t pause when markets are soft.

Bears also question the growth ceiling. NFG’s core territories are mature, and customer growth in the legacy distribution footprint is modest at best. Meanwhile, ESG-driven capital avoidance can weigh on valuation multiples, even if the underlying business performs.

The Realistic Case

The middle view is that NFG is better thought of as a yield vehicle with embedded options than as a pure growth compounder. The most likely path is a mix: gradual pressure on distribution volumes over time, offset by rate base growth and periodic upside or downside from E&P, depending on the commodity cycle.

For income-focused investors, the math is straightforward: roughly a 3% dividend yield plus 1–2% dividend growth gets you to about 4–5% annual returns from income alone. If you layer in modest earnings growth or multiple expansion, total returns could plausibly land in the 6–8% range—attractive for a lower-drama portfolio, but not a rocket ship.

The integration is the point. It doesn’t make NFG invincible, but it does make it harder to break than a pure-play producer or a pure-play utility. The next decade may look manageable; the next few decades are far less certain.

Who should own this: Income investors looking for reliable yield with modest growth. Value investors comfortable with energy exposure. Portfolio diversifiers who want regulated utility stability with some E&P upside.

Who should avoid this: Growth investors looking for outsized capital appreciation. ESG-focused funds with fossil fuel exclusions. Anyone structurally bearish on long-term natural gas demand.

X. Key Performance Indicators for Ongoing Monitoring

If you want to keep tabs on National Fuel Gas without getting lost in the weeds, three metrics tell you most of what you need to know.

1. E&P Production Growth and Unit Costs

Seneca’s production and per-unit costs are the pulse of the upstream business. In the third quarter, Seneca produced a company record 112 Bcf of natural gas, up 15 Bcf, or 16%, from the prior year. And management has pointed to improving capital efficiency continuing into fiscal 2026: capital expenditures were expected to decline by about $20 million, or 4% at the midpoint, while production was expected to rise into a range of 440 to 455 Bcf.

The signal to watch is simple. Rising production while unit costs hold steady or fall is what “good shale execution” looks like. Rising costs, slipping volumes, or both is what it looks like when the rock, the plan, or the market is pushing back.

2. Utility Customer Count and Rate Base Growth

Customer count is the demand reality check. If customer growth stalls—or starts to slide—in the core New York territory, that’s the electrification story showing up in hard numbers.

But don’t stop there. Rate base growth is just as important, because rate base is what the utility is allowed to earn on. Even in a flat-customer world, a utility can still grow regulated earnings by investing in pipeline safety, modernization, and system upgrades that regulators include in the rate base.

3. Dividend Coverage Ratio

NFG’s 55-year dividend growth streak isn’t just a bragging right; it’s a constraint management has chosen to live under. The most telling measure here is coverage—how comfortably earnings or cash flow cover the dividend.

Historically, NFG has targeted a payout ratio around 50%. If that ratio starts drifting toward 70% or higher, it’s a sign the cushion is thinning—and that the company may be relying on a friendlier commodity tape or a stronger utility outcome to keep the streak intact.

XI. Playbook: Lessons for Founders and Investors

Strategic Lessons

Vertical integration as defensive strategy: When you can’t control the commodity price, control the system around it. NFG’s ability to produce, move, store, and ultimately deliver natural gas creates built-in shock absorbers that pure-play businesses simply don’t have.

Geographic advantage compounds: Infrastructure plus subsurface rights plus proximity to demand can become a multi-decade moat. The Marcellus sitting under NFG’s footprint looks like luck in hindsight, but it only mattered because NFG had spent a century building the pipes, storage, and positions in Appalachia that could actually capitalize on it.

Boring businesses can have great economics: Monopolies don’t need to be glamorous to be valuable. NFG has rarely been marketed as a high-growth story, yet it has produced consistent outcomes for generations by doing the unglamorous work—reliability, reinvestment, and steady execution.

Regulated doesn’t mean bad: Rate-of-return frameworks can put a floor under returns and add stability that commodity businesses don’t get. At NFG, the regulated distribution segment has repeatedly acted as the ballast when E&P gets hit by the cycle.

Resource ownership beats operational leverage: Operational excellence matters, but some assets are simply harder to replicate than others. NFG’s mineral rights, underground storage fields, and pipeline rights-of-way are the kind of irreplaceable advantages that competitors can’t “out-execute” their way into.

Capital Allocation Lessons

Dividend discipline as commitment device: A 55-year streak doesn’t survive on slogans. It forces management to protect the balance sheet and produce real cash flow. You don’t keep raising a dividend through down cycles with financial engineering—you do it with a business that can take a punch.

Balanced portfolio approach: Mixing growth (E&P), stability (distribution), and optionality (storage and pipelines) creates resilience that pure-play strategies lack. When one segment is under pressure, another can keep the overall system standing.

Survival over optimization: In commodity businesses, staying alive through the down cycle matters more than squeezing every last dollar out of the up cycle. Conservative leverage and diversified earnings aren’t exciting, but they’re how you get to year 120.

Investor Lessons

Markets often misprice sum-of-parts businesses: NFG has often landed in an awkward middle ground—too slow for growth investors, too commodity-exposed for pure utility buyers. That gap can create opportunity for investors who understand what the integrated model is really doing.

Long-term survivability is underrated: A company that lasts more than a century is telling you something that a single quarter can’t. Institutional memory, regulatory competence, and being embedded in communities can translate into real durability—especially in infrastructure businesses.

Transitions create opportunity: The shale revolution flooded markets with supply and crushed prices, but it also became NFG’s biggest opening—because the company already had the mineral rights and the infrastructure to turn a geological shift into an operating advantage.

The Meta-Lesson

NFG is adaptation within constraints. The company can’t change geology, can’t opt out of regulation, and can’t set commodity prices. So it built a model designed to function anyway—sometimes even benefitting from the very constraints that frustrate others. In regulated infrastructure, limits can double as protection.

The optionality in an integrated system is real: storage plus pipelines plus production can be worth more together than apart. The ability to move molecules across segments, manage timing, and cushion volatility isn’t theoretical—it’s strategic value.

And sometimes, “boring and local” beats “exciting and global.” NFG stayed focused on Western New York and Pennsylvania for 120 years, and that focus enabled deep infrastructure investment, durable regulatory relationships, and community trust that a roaming national player would struggle to replicate.

XII. The Road Ahead

Near-Term Outlook (2025-2027)

After a century of surviving whatever the energy world threw at it, National Fuel Gas is heading into the next couple of years with unusually clear momentum. The company initiated fiscal 2025 earnings guidance of $5.75 to $6.25 per share—about a 19% lift from fiscal 2024—and said it expects average annual EPS growth to exceed 10% over the next three years. For a business that so often gets labeled “boring utility,” that’s a meaningful statement about how much earnings power management believes is sitting inside the model right now.

The biggest near-term swing factor is the Ohio deal. NFG agreed to acquire the equity interests in CNP Ohio for total consideration of $2.62 billion, an acquisition multiple of approximately 1.6x estimated 2026 rate base. If it closes—expected in late 2026, pending regulatory approvals—it would be the kind of move that changes the company’s center of gravity: more regulated earnings, less dependence on commodity pricing, and a larger platform to reinvest capital into rate base.

On the infrastructure side, pipeline expansion is still on the agenda—but it’s been reshaped by hard-earned lessons. With Northern Access abandoned, NFG has pivoted toward other projects, including the Tioga Pathway and the Shippingport Lateral, aimed at connecting supply to pockets of growing power generation demand. In today’s permitting climate, the ability to do smaller, more targeted expansions matters—and the company is clearly prioritizing what can actually get built.

Medium-Term Questions (2027-2035)

In the medium term, the entire downstream story hinges on one question: how fast does electrification actually happen?

Heat pump adoption, building codes that restrict gas in new construction, and shifting state climate policy will show up in the only metric that really counts for a utility over time—customer counts and usage. If the transition is gradual and managed, utilities can keep growing earnings through modernization and rate base investment. If it’s fast and uneven, you get the ugly scenario: fewer customers left paying for a system that still has to be maintained.

Pennsylvania’s posture is the other pillar. New York has already made its position clear. Pennsylvania, so far, has remained supportive of natural gas development—and that difference is central to why Seneca’s growth has lived on one side of the border. A meaningful policy shift in Pennsylvania would ripple through NFG’s upstream economics and, by extension, the whole integrated engine.

Then there’s LNG. As more export terminal capacity comes online, the pull on U.S. natural gas demand could strengthen. For Appalachia, that matters because it has long struggled with regional price discounts driven by takeaway constraints. If more gas can reliably reach higher-value markets, the basis differential that has weighed on regional realizations could narrow—changing the economic ceiling for Marcellus production.

Long-Term Existential Questions (2035+)

Past the mid-2030s, the questions stop being cyclical and start being structural.

What does “net zero by 2050” actually mean for natural gas utilities? If current commitments are implemented as written, it implies a dramatic reduction—possibly an elimination—of direct fossil fuel use in buildings. Whether those commitments hold, what exemptions get carved out, and how transition timelines are managed remains deeply uncertain, but the direction of travel is hard to ignore.

Could renewable natural gas or hydrogen blending preserve the value of gas infrastructure? Utilities across the industry are exploring both as decarbonization pathways that keep pipes relevant. The challenge is that neither has yet proven economically viable at scale.

And then there’s a more interesting, harder-to-price form of optionality: storage. NFG’s subsurface formations are already valuable for natural gas. In a different energy system, could those same geological assets matter for CO2 or hydrogen storage? It’s not a base-case assumption. But it’s the kind of “real asset” option that integrated infrastructure companies sometimes wake up to one day and realize they’ve been holding for decades.

What to Watch

- Pennsylvania and New York regulatory proceedings

- E&P capital allocation and production trends

- Dividend coverage ratios

- ESG ratings and investment fund inclusion/exclusion

- Customer growth or decline in distribution segment

- Natural gas forward curve and basis differentials

- Ohio acquisition regulatory approval process

- Data center and power generation demand in region

Final Reflection

National Fuel Gas is a case study in how regulated monopolies navigate disruption—not by trying to become something completely different, but by doubling down on what they do best while keeping enough optionality to survive the next regime. The company has lived through Standard Oil’s shadow, two world wars, the Great Depression, multiple commodity price collapses, and the shale revolution. The defining question of the next chapter is whether the integrated model can hold up through an energy transition that’s as political as it is technological.

The biggest surprise in researching this company is how much the integration actually matters. Not in a consultant-slide way—in a survival way. The cushion between segments, the storage flexibility, and the diversification across regulated and unregulated earnings created resilience that pure-play competitors simply didn’t have.

The broader takeaway is easy to miss in an era obsessed with the new: sometimes the best businesses aren’t the ones trying to change the world. They’re the ones that quietly keep the world running—and keep compounding while nobody’s looking.

In the end, National Fuel Gas is a bet on three things: that natural gas stays essential longer than the bears expect, that infrastructure moats persist even as the energy system changes, and that boring, steady compounding can beat exciting volatility. For 120 years, that bet has worked. The next chapter will decide whether it still does.

Further Learning and Resources

Company-Specific: - National Fuel Gas Annual Reports and 10-K filings (2015–2025). If you want the story in management’s own words—strategy, segment performance, risk factors, and the “why” behind capital allocation—start here. - NFG Investor Presentations. These are the cleanest way to see how the company frames the integrated model, where it’s investing, and what it believes the next few years look like. - Pennsylvania and New York Public Utility Commission rate case filings. Dry, but essential: this is where the rules of the regulated game are actually written, argued, and enforced.

Industry and Context: - The Frackers by Gregory Zuckerman. A fast, human view of how shale went from weird experiment to world-shaping supply shock. - The Prize by Daniel Yergin. The long arc: geopolitics, energy power, and why “molecules in the ground” have always mattered. - EIA Annual Energy Outlook. The baseline reference for demand, supply, and long-range assumptions—imperfect, but a useful anchor.

Strategic Frameworks: - 7 Powers by Hamilton Helmer. The clearest guide to identifying durable competitive advantage—and a great lens for understanding why NFG’s cornered resources matter. - Understanding Michael Porter by Joan Magretta. The most readable way to use Five Forces without turning your brain into a spreadsheet.

Market and Trends: - RBN Energy blog on natural gas markets and infrastructure. Great for the mechanics—basis, constraints, flows, and why pipes and storage can matter as much as drilling. - Natural Gas Intelligence for Appalachian market coverage. A strong source for day-to-day developments in the basin and the infrastructure around it.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music