NBT Bancorp: The Story of Upstate New York's Community Banking Survivor

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

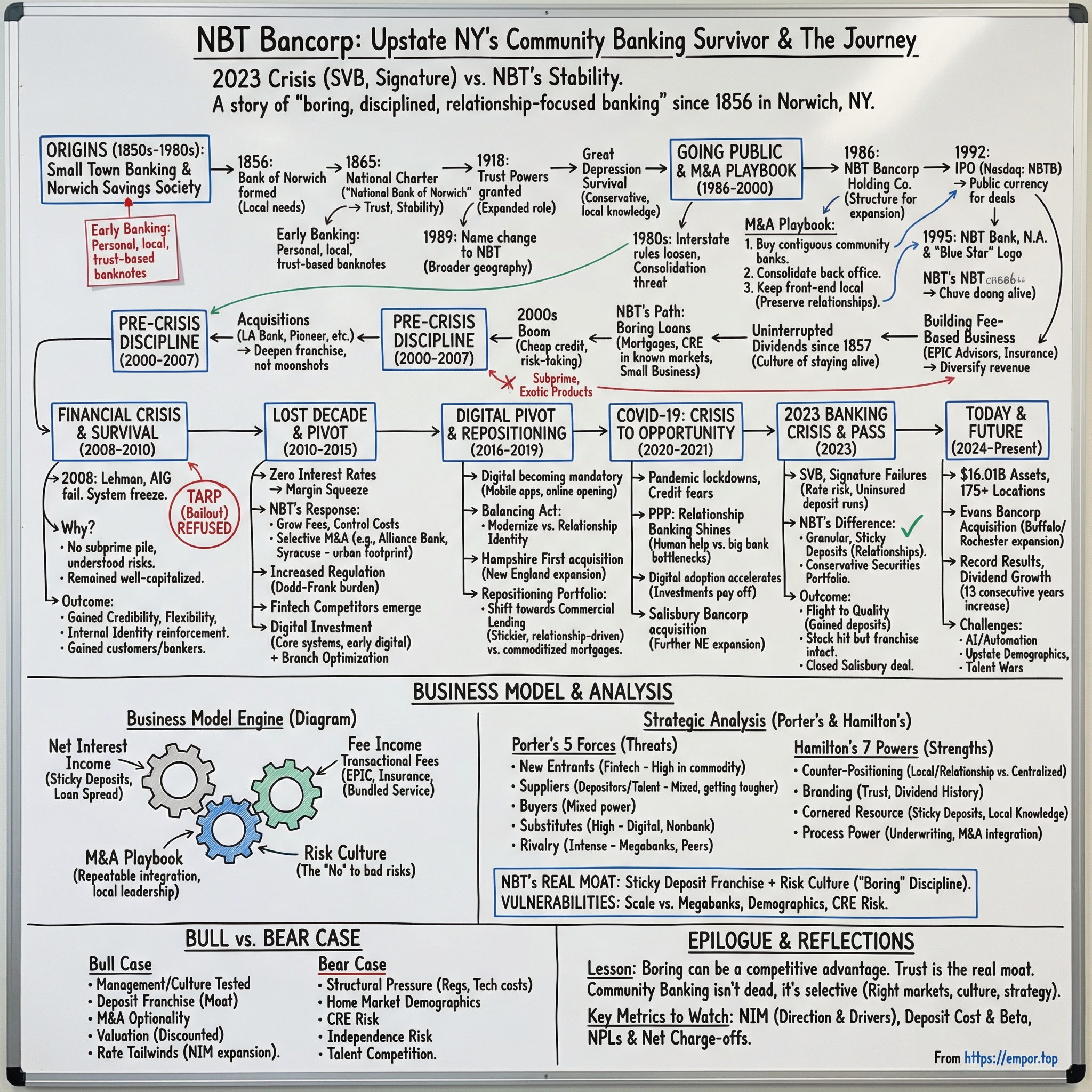

Picture this: it’s March 2023, and American banking suddenly looks a lot less stable than everyone thought. Silicon Valley Bank collapses in what becomes the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history. Signature follows days later. First Republic is wobbling. Depositors everywhere start yanking money from regional banks, not because they’ve read the footnotes, but because fear moves faster than facts. Cable news fills the airtime with the same question on loop: is this the start of something bigger?

Now cut to Norwich, New York, a town of roughly seven thousand people tucked into the hills of Chenango County. The phones at NBT Bank are ringing too. But the calls aren’t from customers in a sprint to the exits.

They’re from people asking how to move their accounts in.

That contrast is the hook for this entire story. Because NBT Bancorp isn’t supposed to be the bank that wins when confidence evaporates. It started in 1856 as a small-town savings institution. And yet, nearly 170 years later, it’s still headquartered in Norwich—and it runs a network of more than 175 banking locations across seven states: New York, Pennsylvania, Vermont, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, and Connecticut. As of June 30, 2025, NBT Bancorp reported $16.01 billion in total assets, placing it firmly in the category of a real regional player in the Northeast.

So how does a bank born in a rural New York community make it through the Civil War, multiple financial panics, the Great Depression, the 2008 crisis without taking a bailout, the fintech era, and then the 2023 banking shock—and come out the other side intact, sometimes even stronger?

NBT’s own answer is almost unfashionable: boring, disciplined, relationship-focused banking. The company says that, since 1856, it has stayed committed to “providing our customers with superior banking services,” and that “our greatest competitive advantage remains our people.”

And that’s where this story lives. Community banks like NBT are the financial plumbing of regional America. They make the loans that keep Main Street businesses alive, finance the mortgages that let families buy homes, and do the unglamorous work of keeping local economies functioning. When big banks pulled back from smaller towns and rural markets, banks like NBT stayed.

This is the story of how one small-town bank built a regional franchise through patient acquisition, conservative underwriting, and a stubborn belief that relationships matter more than transactions. It’s a story about choosing “no” when “yes” would’ve been faster, easier, and more profitable—right up until it wasn’t. And it’s a story about what happens when boring banking runs into existential crisis… over and over again.

II. The Origins: Small Town Banking & The Norwich Savings Society (1850s–1980s)

In the mid-1850s, Norwich, New York was a town with momentum. Tucked into the hills of Chenango County about an hour south of Syracuse, it sat on the Chenango Canal, a watery supply chain that linked the region’s farms and small manufacturers to the Erie Canal and, from there, to the broader economy. Commerce was picking up. Money was moving. And for a growing town, there was one obvious bottleneck: banking.

Warren Newton, a local attorney, captured the problem plainly in 1872: “Sixteen years ago the business of this community seemed to a few of the citizens to require more banking facilities than then existed.” At the time, Norwich had just one bank: the Bank of Chenango. For a town trying to grow, that wasn’t enough.

So on January 31, 1856, eleven local business leaders decided to build the missing piece themselves. They formed the Bank of Norwich. The group included Newton—who’d previously worked as a contractor on the Erie and Chenango canals—his brother Isaac Newton, and James H. Smith, who became the bank’s first president. Their first board meeting took place on March 3, 1856, at the Newtons’ law office. And on July 15, 1856, the new bank opened for business in a storefront on South Main Street.

Early banking was personal, local, and a little wild by modern standards. The Bank of Norwich even printed its own banknotes. This was before federal paper money, in an era when individual banks issued notes backed not by the government, but by their own capital and credibility. These notes weren’t legal tender. Nobody had to take them. In practice, a bank’s “currency” worked only if the community believed the bank would still be standing tomorrow.

That same dynamic—trust first, balance sheet second—shaped the bank’s next big step. On June 28, 1865, just months after the Civil War ended, the Bank of Norwich received a national charter and became the National Bank of Norwich. Today, state versus national charters feel like technicalities. In the 1860s, a national charter was a public signal: this institution was built to last. And in banking, perception isn’t marketing; it’s oxygen.

The bank grew with the town. Canals that helped Norwich take off were eventually joined by railroads. Farmers needed credit to plant and harvest. Merchants needed working capital. Small manufacturers needed financing to expand. Families needed a place to save. The bank’s business wasn’t abstract finance—it was the day-to-day economics of a community trying to build a future.

In 1918, the bank took a step that would echo through the next century: it became one of the first national banks in New York State to apply for and receive trust powers under the Federal Reserve Act, creating a Trust Department. This wasn’t just a new product line. It was an early version of a strategy NBT would repeat again and again: don’t just hold deposits and make loans—become the institution customers rely on for their broader financial lives.

Then came the 1930s. The bank completed its first acquisitions just as the Great Depression tore through American finance. Thousands of banks failed nationwide. The National Bank of Norwich survived the way community banks most often survive: by being conservative, by staying close to its customers, and by making loans based on local knowledge. Depositors knew the bankers. The bankers knew the businesses. This wasn’t banking by model or formula. It was banking by relationship.

Along the way, the name evolved to match a widening role. In 1925, the bank changed its name to reflect its expanded services. And as its footprint broadened beyond Norwich, it later changed its name again in 1989 to The National Bank and Trust Company, dropping “of Norwich.” The geography was growing, even if the identity stayed the same.

Through the Great Depression, World War II, and the postwar boom, the bank remained what it had always been: steady, local, and deliberately unflashy. In an industry where “innovation” often meant stretching for risk, the most important thing the National Bank and Trust Company kept doing was refusing to get cute.

But by the 1980s, the ground under banking was shifting. Interstate restrictions were loosening. Consolidation was accelerating. Bigger institutions were getting bigger—and getting closer. For a bank rooted in a small upstate town, the question was no longer theoretical: stay small and slowly become irrelevant, or change shape and fight for the future.

III. Going Public & The M&A Playbook Begins (1986–2000)

By the mid-1980s, the rules of American banking were being rewritten in real time. The Depression-era framework that kept banks small, local, and boxed into state lines was loosening. Interstate restrictions were starting to fall. Big banks were getting bigger. And for smaller institutions, the choice was becoming painfully binary: scale up, or get swallowed.

NBT’s first big move was structural. In 1986, it incorporated NBT Bancorp Inc. in Delaware as a holding company for NBT Bank, N.A. That sounds like paperwork, but it was really a new operating system—one designed for expansion.

The bigger leap was the ownership shift. For generations, mutual banks had been owned by their depositors. It was a stable model, but it came with a ceiling: limited access to growth capital. In a world where banking was consolidating fast, that ceiling mattered. Converting to a stockholder-owned institution gave NBT a new tool kit—capital to fund acquisitions, equity to attract and reward talent, and the ability to play offense instead of just defending its home turf.

In March 1992, NBT’s common stock began trading on the Nasdaq under the symbol NBTB. Now it had something every consolidator needs: a public currency it could use to compete for deals.

The strategy that followed was simple, and very NBT. Management looked at the landscape and saw an uncomfortable middle: too small to go toe-to-toe with the money-center giants on scale, too big to rely only on handshakes and hometown inertia. Their answer became a repeatable playbook—buy community banks in nearby, contiguous markets, consolidate the back office, and keep the customer-facing side local.

Then came the brand that matched the ambition. In 1995, the bank changed its name again—this time to NBT Bank, N.A., with “N.A.” standing for National Association—and rolled out the logo customers still recognize today: a blue star and red lettering. It was a signal that NBT was thinking beyond a single town, without pretending it wasn’t still a community bank at heart.

What made the acquisition approach work wasn’t just deal volume. It was integration philosophy. NBT didn’t want to be the conquering outsider that walked in, fired local leadership, and centralized decisions two counties—or two states—away. In many acquisitions, local leadership stayed. Loan decisions and service stayed close to the customer. The efficiencies came from consolidating systems and back-office functions, not from stripping the community out of community banking.

That wasn’t charity. It was a competitive edge. When a national or super-regional bank bought a local institution, customers often bolted to the next place that still felt familiar. NBT’s goal was to be that familiar place—even if it was the buyer. Preserve the relationships, add the resources of a larger bank, and keep depositors from treating the merger as an eviction notice.

And underpinning all of this was a reputation that few financial institutions can claim: uninterrupted dividend payments since 1857. Through wars, depressions, panics, booms, and busts, the bank kept paying. That kind of record doesn’t happen because of one great year. It happens because an institution builds a culture around staying alive.

By the end of the 1990s, the pieces were in place: a holding company built for growth, publicly traded stock to fund it, a disciplined acquisition model, and a brand anchored in stability. The foundation was laid.

Now the question was whether NBT could execute—at scale, and through whatever the next cycle would bring.

IV. The Pre-Crisis Buildup: Strategic Discipline (2000–2007)

The early 2000s were a strange kind of boom for American banking. The dotcom bubble had popped, the Fed drove rates down, and credit got cheap. For banks, that’s catnip. Growth was there for the taking—if you were willing to relax standards, reach for yield, and say yes to products that looked safe on paper.

A lot of the industry did exactly that.

NBT didn’t.

Starting in 2000, NBT kept running the playbook it had been building for a decade: buy small community banks in markets that looked and felt like home. It acquired LA Bank in Scranton, Pennsylvania and Pioneer American Bank in Carbondale, Pennsylvania (both in 2000). It followed with First National Bank of Northern New York in Norfolk, New York and Central National Bank in Canajoharie, New York (both in 2001). Then, in 2005, it added City National Bank and Trust Company in Gloversville, New York.

None of these were moonshot deals. That was the point. They were the kind of additions that quietly deepen a franchise: deposits, loans, branches, and local relationships—without forcing the bank into unfamiliar geographies or unfamiliar risk.

But the most important part of NBT’s story in this era is what it didn’t do.

While competitors chased subprime mortgages, complex structures, and anything that could goose returns, NBT stuck to loans it could underwrite with its eyes open: residential mortgages to borrowers with documented income; commercial real estate where the bankers knew the developers; small-business loans tied to real cash flow. The culture was consistent and plainspoken: we lend to people we know, in markets we understand.

It wasn’t flashy. It didn’t produce the kind of growth that gets you onto magazine covers. But it built something far more valuable in banking: a balance sheet you can sleep on.

At the same time, NBT quietly made another move that would matter later—building businesses that didn’t depend on the spread between deposit rates and loan rates. EPIC Advisors (later renamed EPIC Retirement Plan Services), a Rochester-based 401(k) recordkeeping firm, provided retirement plan administration services nationally. NBT Insurance Agency expanded the bank’s ability to serve customers with insurance products through its branch network. Together, those fee-based lines helped diversify revenue and reduce dependence on interest income alone.

Behind the scenes, the bank also invested in the unglamorous infrastructure that makes a community-bank roll-up work: core system upgrades, early digital banking capabilities, and back-office improvements. This was the kind of spending that rarely feels urgent in good times—and becomes existential when times turn.

And then there was governance. At community banks, boards are often made up of local business leaders with deep roots and real reputations at stake. That kind of board tends not to reward recklessness. It reinforces a long-term mindset—especially when the bank’s brand is built on being the steady one.

By the end of 2007, NBT had expanded across upstate New York and northeastern Pennsylvania with a loan book that was, by design, boring. Capital was strong. The franchise was bigger. And just as important, the bank hadn’t filled its cupboards with financial products it couldn’t explain.

As the first cracks started to show in the broader system, NBT wasn’t scrambling to unwind yesterday’s decisions. It was braced—ready to absorb the shock, and potentially pick up ground while others tried to stay standing.

V. The Financial Crisis: Survival Without a Bailout (2008–2010)

In September 2008, the American financial system was staring into the abyss. Lehman Brothers failed in the biggest bankruptcy in U.S. history. AIG needed a rescue. Money market funds “broke the buck.” Credit markets seized up. For a few weeks, it felt like the machinery of modern finance might simply stop.

For banks, the government’s response came with a dilemma wrapped in a lifeline: TARP, the Troubled Asset Relief Program. Congress authorized up to $700 billion to stabilize the system, and about $250 billion ultimately went into banks through the Capital Purchase Program. The biggest names took it—Citigroup, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley—along with plenty of regionals and community banks.

The trade-off was clear. Take the money and accept the headlines, the stigma, and the strings—limits on executive compensation, constraints around dividends, and less strategic flexibility at exactly the moment you wanted options. Or refuse it and risk being lumped in with the weak, in a market that was punishing first and asking questions later.

NBT refused.

Not because it couldn’t qualify. The program was designed to support healthy banks of all sizes, and many community banks participated. NBT’s difference was that it didn’t need the capital to stay upright.

This is where all that “boring” from the earlier chapter cashes out. NBT didn’t have a pile of subprime mortgages. It didn’t have exotic structures it couldn’t unwind. It wasn’t sitting on the kinds of exposures that were detonating balance sheets across Wall Street. And even where it did take risk—as every bank has to, because lending is the business—the risk was the kind it understood. Its commercial real estate lending was concentrated in places its bankers knew intimately: the same upstate towns and regional markets where the loan officer had likely driven past the property a hundred times.

Credit quality still got worse—of course it did. This was the worst downturn since the Great Depression. NBT increased provisions for loan losses, and those hits were real. But they weren’t fatal. The damage was contained, and the bank stayed well-capitalized through the storm.

Declining TARP also gave NBT something that’s hard to buy in a crisis: credibility.

First, it sent a simple, powerful message to customers: we’re strong enough to stand on our own. When depositors everywhere were questioning institutions they’d trusted for decades, NBT could say—truthfully—that it hadn’t needed government support to keep operating.

Second, it kept NBT free from the operational handcuffs that came with TARP, preserving flexibility around leadership decisions, capital planning, and strategy.

And third—maybe the most important—it strengthened the bank’s internal identity. Surviving without outside help wasn’t just a financial outcome; it was cultural reinforcement. It rewarded the very instincts that had kept the bank from chasing the pre-crisis frenzy in the first place.

While competitors struggled—some failing outright, others being forced into mergers—NBT was in position to play offense. Customers leaving troubled institutions needed a safe place to land. Businesses whose banking relationships were suddenly disrupted needed a new partner. And bankers at stressed institutions started looking for stability.

In a consolidation-heavy industry, 2008 to 2010 was the kind of sorting event that permanently separates survivors from future footnotes. NBT came out the other side intact—balance sheet stronger, strategy validated, and reputation sharpened. The discipline of saying no—to subprime, to exotic products, to markets it didn’t understand—paid off in the most dramatic way possible.

But the crisis wasn’t the end of the test. The post-crisis world brought a different kind of pressure: years of near-zero interest rates, a surge of regulatory burden, and a new generation of fintech competitors determined to make traditional banking feel obsolete.

VI. The Lost Decade: Zero Interest Rates & The Search for Growth (2010–2015)

The crisis ended, but for banks, the hangover lasted a lot longer. The Federal Reserve cut interest rates to near zero—and then kept them there for years. That policy helped stabilize the economy. For community banks like NBT, it created a slow-moving grind that threatened the core engine of the business.

A traditional bank lives on the spread between what it pays for deposits and what it earns on loans. When rates collapse, that spread gets pinched from both sides. Deposit costs can’t go meaningfully below zero, but loan yields fall quickly, and competitors keep pushing them lower. So even if credit quality holds up, earnings get squeezed. Not by one bad quarter, but by year after year of arithmetic.

This was the era when a lot of community banks tried to “solve” the problem by stretching. They reached for yield by taking more duration risk, loosening credit standards, or loading up on longer-dated securities that looked safe—right up until rates eventually moved the other way. A decade later, that exact dynamic would become part of what sank Silicon Valley Bank.

NBT largely refused to play that game. Instead of trying to force profitability out of risk, it leaned into the levers it could actually control: grow fee-based businesses, keep a lid on costs, and use selective M&A to build scale in markets it understood.

The biggest move of the period was the 2013 acquisition of Alliance Bank in Syracuse. The merger closed on March 8, 2013, and it became NBT Bank’s largest deal to date. Syracuse—metro population north of 600,000—was a different kind of market from the small towns NBT had been stitching together for decades. It was the bank’s largest urban footprint, and it materially deepened NBT’s commercial banking capabilities. Just as importantly, it brought experienced bankers and long-standing customer relationships that could power the next chapter.

Alliance also fit NBT’s acquisition playbook. Stick to contiguous markets. Find a compatible culture. Keep the local trust intact. Take out complexity in the back office, but don’t “strip mine” the franchise by ripping out the very people customers came to the bank to see. The goal wasn’t a quick cost-cutting win. It was long-term franchise building.

That same logic shaped NBT’s broader strategy in the lost decade. Rather than scatter across far-flung geographies, it focused on building density in upstate New York—connected markets where brand recognition, operating efficiency, and relationship banking reinforce each other. In banking, being “everywhere” can be a trap. Being strong in the places you choose can be a moat.

And while the branch network still mattered, the world was clearly shifting. NBT accelerated technology investments: core system work, early digital banking features, and the behind-the-scenes infrastructure upgrades that never make headlines but determine whether a bank can keep up when customer behavior changes. This wasn’t flashy spending—it was survival spending.

At the same time, regulation tightened dramatically. Dodd-Frank, passed in 2010, added new layers of compliance and reporting. The biggest banks could amortize that burden across massive balance sheets and armies of specialists. Smaller banks couldn’t. NBT landed in an awkward spot: large enough to face serious scrutiny, not large enough to make the cost painless. Compliance didn’t just hit the income statement; it consumed management time, attention, and flexibility.

Then came the new kind of competitor. Fintechs started popping up with a simple message: we can do the bank’s job without the bank. Lending platforms offered personal loans without branches. Mortgage tech streamlined home buying. Payments companies routed around traditional rails. The question facing any branch-based institution was blunt: if a smartphone can do what a branch used to do, what is the branch for?

NBT’s answer was that the branch wasn’t the product—relationships were. A fintech could approve a loan, but it couldn’t replace a banker who understood a local business and could structure financing around a real-world situation. An app could move money, but it couldn’t sit with a family and talk through retirement planning. NBT bet that “human” would still matter—that relationship banking could differentiate it from both megabanks and algorithms.

By the time this period ended, NBT had done what it always tried to do: stay upright, stay disciplined, and quietly prepare for the next turn of the cycle. It hadn’t found an easy growth hack—because there wasn’t one. But it had built scale in the right places, kept risk in check, and invested in the infrastructure it would need for a world that was becoming digital whether community banks liked it or not.

VII. The Digital Pivot & Portfolio Repositioning (2016–2019)

By 2016, it was obvious that digital banking wasn’t a nice-to-have anymore. Mobile adoption was accelerating. Younger customers expected to open accounts, move money, and apply for loans without ever walking into a branch. And even NBT’s most loyal, long-tenured customers—the ones who still liked a handshake—were getting comfortable checking balances and paying bills online.

That year, NBT hit its 160th anniversary and published an updated history of the bank to mark the milestone. It was a celebration, but it also underscored a hard truth: the next chapter would be nothing like the first. If NBT wanted to keep being “the steady one” for another generation, it had to look steady on a phone screen too.

That required real investment. Mobile apps. Online account opening. Digital mortgage tools. Cybersecurity that could keep up with a world of constant threats. None of it was glamorous, and none of it was free. This was capital that could’ve gone elsewhere—dividends, buybacks, acquisitions. But management’s view was simple: if you don’t invest in the plumbing, eventually the whole house stops working.

The trick was that NBT wasn’t serving one customer base. It was serving two—often in the same town.

In rural upstate New York, many customers still valued the comfort of a local branch and a banker who knew their name. At the same time, younger customers—some of whom had never set foot inside a bank—compared NBT’s experience not to the bank down the street, but to whatever app they used every day. That gap in expectations forced a balancing act: modernize without losing the relationship-driven identity that made NBT, NBT.

So the branch strategy evolved. Underperforming locations were closed or consolidated. Investment went into the branches that mattered most, and into the digital infrastructure that made the physical footprint less central. The goal wasn’t to abandon branches. It was to right-size the network for a world where routine transactions had moved online, while branches still mattered for the moments that actually require people—complex lending decisions, problem-solving, and trust-building.

This period also reflected a longer-running geographic shift. Even though it predated 2016, NBT’s acquisition of Hampshire First Bank in 2012 helped set up where the franchise was headed next. The $45 million deal, completed in June 2012, expanded NBT into southern New Hampshire by bringing in Hampshire First—an institution with $273 million in assets at the time. Its five branches in Manchester, Londonderry, Nashua, Keene, and Portsmouth initially continued operating under the Hampshire First name.

Just as telling as the footprint was the leadership choice. Martin Dietrich, NBT’s president and CEO at the time, highlighted the retention of Hampshire First’s founding CEO, James Dunphy, as New Hampshire regional president—something Dietrich described as “the first time we have had the opportunity to welcome a bank’s founding CEO into our ranks following a merger.” That wasn’t a throwaway quote. It was the NBT integration philosophy in one sentence: keep the people who carry the relationships.

New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts—these weren’t random pins on a map. They were logical extensions: nearby markets with similar demographics, similar banking needs, and economies where a community bank could still matter.

At the same time, NBT was repositioning what it did inside those markets.

The traditional community bank model leaned heavily on residential mortgages and consumer lending. But by the late 2010s, those products were becoming increasingly commoditized. Fintechs could often do them faster, with slicker interfaces and aggressive pricing. Commercial and industrial lending, on the other hand, was different. It required context. Judgment. Creativity. A banker who understood how a business actually worked—and who could structure financing around real-world cash flow, seasonality, and risk—could deliver something no algorithm could fully replicate.

NBT leaned into that advantage. It expanded its commercial and industrial lending capabilities and began remixing the portfolio away from residential mortgages and toward commercial lending, including commercial real estate. It was a deliberate bet that commercial relationships would be stickier and more valuable, and that the bank’s edge—local knowledge and long-term relationships—would matter more there than in a race to approve the fastest personal loan.

Then, after years of near-zero rates, the environment finally started to change. From 2017 through 2019, rising rates offered banks like NBT some relief. Higher yields improved the spread between what the bank earned on loans and what it paid on deposits, and net interest margin began to recover after the long post-crisis squeeze.

By the end of the decade, the outline of a different NBT was visible. The footprint had widened beyond upstate New York. Digital capabilities were no longer an afterthought. The balance sheet was tilting more toward commercial customers. Efficiency improved as the bank adapted its costs to new customer behavior. NBT entered 2020 with what looked like strong positioning: a more diversified loan book, a modernized platform, solid capital, and an established presence in growing New England markets.

And then the world changed again.

VIII. COVID-19: From Crisis to Opportunity (2020–2021)

March 2020 hit banking like a freight train. A global pandemic shut down parts of the economy almost overnight, and banks were forced to operate in a reality they’d never rehearsed for. Lobbies closed or went appointment-only. Employees scrambled into remote setups. And every loan portfolio—no matter how “safe” it looked in February—suddenly had a giant question mark hanging over it: how many borrowers can survive if commerce just… stops?

For community banks like NBT, the crisis also opened a strange, high-stakes lane to prove what they were good at. That lane was the Paycheck Protection Program.

PPP was designed to keep small businesses alive by offering forgivable loans to cover payroll and a few essential expenses. But the government didn’t distribute the money directly. Banks did. Which meant banks had to become emergency-lending machines—processing waves of applications fast, under intense pressure, while the rules and guidance shifted in real time.

A lot of big banks struggled. Their systems weren’t built for rapid, high-volume lending to tiny businesses. Processes bogged down. Call centers melted. And small business owners who thought they had a banking relationship discovered they mostly had a routing number.

This is where community banks—NBT included—looked less like a quaint legacy model and more like the right tool for the moment. Relationship banking, the thing that can feel inefficient in normal times, became an advantage when business owners needed a human being to help them navigate a confusing government program. NBT’s bankers knew their customers. They could pick up the phone, walk through what documents were needed, and help owners get a lifeline in place before payroll bounced.

It was a marketing moment you couldn’t buy. The businesses that got help remembered who answered and who didn’t.

Operationally, the bank had to pivot fast. Branches that used to be the center of daily activity became less important as routine transactions flowed through online and mobile channels. Employees adjusted to remote work—imperfectly, like everyone else, but well enough to keep the machine running. And the digital investments NBT had been making for years suddenly stopped looking like optional modernization and started looking like insurance that paid out exactly when it was needed.

Back in March 2020, credit fears were everywhere. It was easy to imagine a cascading wave of defaults. Instead, the worst-case scenario largely didn’t materialize. Government support—stimulus checks, enhanced unemployment benefits, and PPP itself—kept many consumers and businesses afloat longer than anyone expected. The downturn was sharp, but the recovery came faster than the early headlines suggested.

On NBT’s balance sheet, the pandemic created some unusual dynamics. Deposits surged as households held onto stimulus money and businesses parked PPP proceeds. Fee income rose as PPP lending generated processing revenue. And while the loan book lived under a cloud of uncertainty for months, it ultimately performed far better than that first wave of fear implied.

Then, coming out of the pandemic period, NBT pushed its footprint further into New England. The Salisbury Bancorp deal—announced in December 2022—expanded NBT into Connecticut and Massachusetts. The acquisition of Salisbury Bancorp, Inc. closed on August 11, 2023, adding 13 offices and approximately $1.2 billion in loans and $1.3 billion in deposits. Strategically, it was classic NBT: a move into attractive, higher-growth markets, done through a community bank with an established local presence, rather than a greenfield expansion that would take years to earn trust. The transaction was valued at approximately $204 million and followed the same familiar playbook: compatible culture, local continuity, and efficiencies behind the scenes without breaking the customer relationships on the front end.

The pandemic also poured gasoline on another pressure point: talent. Good bankers—especially experienced commercial lenders—were suddenly even more scarce. Competition came from every direction: other regionals, national banks, and fintechs that could often pay more. NBT’s reputation for stability and community focus helped, especially for people who valued the mission and the culture, but retention became a constant fight across the industry.

By the time the world started inching back toward normal, NBT had a new set of realities to manage. Customers now expected better technology by default. PPP had reinforced that relationships still mattered when it counted. Expansion brought more opportunity—and more complexity. And the talent market wasn’t going back to the old rules.

NBT’s answer was consistent with its history: stay rooted in community banking, but keep adapting fast enough to stay relevant. The model didn’t change. The execution had to.

IX. The 2023 Banking Crisis: Another Test, Another Pass (2023)

March 2023 brought another test—one that separated well-managed regional banks from the pretenders.

Silicon Valley Bank had to sell bonds at a loss. The market smelled blood. SVB’s stock price plunged, depositors panicked, and the whole thing turned into a classic bank run—fast, contagious, and merciless. It became the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history. Signature Bank followed. And suddenly, every regional bank with a meaningful base of uninsured deposits was guilty until proven otherwise.

SVB’s collapse also made one thing painfully clear: interest rate risk isn’t theoretical.

The federal funds rate had jumped from about 0.25% in March 2022 to roughly 4.75% by February 2023. That kind of move is a wrecking ball for long-dated, low-yield securities. If you’re sitting on a big pile of “safe” bonds classified as held-to-maturity, you might not have to mark them down on paper—but the economics still show up the moment you need liquidity.

SVB’s real vulnerability, though, wasn’t just its bond book. It was its deposit base.

SVB banked tech and life sciences companies, which meant many customers kept balances far above the $250,000 FDIC insurance limit. Those weren’t sleepy retail accounts. They were large, concentrated, and highly networked. When confidence cracked, those depositors had every incentive to move first and ask questions later.

Within days, the depositor runs helped topple Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and then First Republic. In a higher-rate world, uninsured depositors stopped believing in the old playbook of taking in deposits and investing the proceeds in long-term assets to earn a term-spread carry—especially if they weren’t sure they’d be there to see the maturity date.

NBT’s world looked nothing like SVB’s.

Community bank deposits tend to be smaller, more granular, and built on relationships. A local business owner with a few hundred thousand dollars in a checking account usually isn’t monitoring social media for the latest rumor. They’re trying to make payroll, manage inventory, and get through the week. That “stickiness,” which can look like a growth constraint in boom times, becomes a shock absorber when panic hits.

NBT’s securities portfolio also reflected a more conservative posture. The bank hadn’t piled into long-duration bonds at the top of the market, so unrealized losses in the held-to-maturity portfolio were manageable. As investors and regulators went balance sheet by balance sheet hunting for SVB-style weak points, NBT’s profile read as reassuring instead of alarming.

And then there was the part that’s hard to model, but easy to feel in a crisis: communication.

Regional bank management teams had to walk a tightrope—acknowledge the stress in the system without sparking fear about their own institution. NBT leaned on transparency with investors and customers, explaining why its funding and risk profile were different from the banks that had failed. In banking, confidence is a liability and an asset at the same time. The banks that could hold it, held everything else too.

In fact, the crisis created an odd reversal: rather than losing deposits, well-managed community banks like NBT could gain them. Customers leaving institutions that looked unstable needed somewhere they could trust. And a bank that had been around for more than a century and a half—one that had already made it through every kind of American financial chaos—looked like the opposite of experimental.

The market didn’t reward nuance. It rarely does.

Regional bank stocks were sold off broadly as investors fled the sector, and NBT’s shares fell along with peers despite its more conservative positioning. For long-term investors, that kind of indiscriminate punishment can create the rarest thing in public markets: a quality business marked down for someone else’s mistakes.

NBT was also executing in the middle of the storm. The Salisbury Bancorp acquisition closed in August 2023 for approximately $204 million—right as the sector was still digesting the panic. Closing a deal in that environment takes conviction: conviction in the target, in the integration plan, and in your own balance sheet. Salisbury Bank President and CEO Richard J. Cantele Jr. joined NBT Bank’s board of directors and executive management team, continuing NBT’s long-running habit of keeping local leadership in place rather than stripping it out.

Just like 2008, the 2023 crisis drew a bright line. Banks that chased yield, concentrated themselves in flighty deposits, or mismanaged interest rate risk paid the price. Banks that stayed boring—disciplined underwriting, conservative balance-sheet management, and relationship-based funding—did what they’ve always done.

They survived. And in the process, they got stronger.

X. Today & The Road Ahead: AI, Fintech, and Community Banking's Future (2024–Present)

If the last few chapters were about passing stress tests, the current one is about building the next version of the franchise while the industry keeps changing underneath it.

Today, NBT Bancorp is a financial holding company still headquartered in Norwich, New York, with $16.01 billion in total assets as of June 30, 2025. It operates through NBT Bank, N.A.—with 175 banking locations across seven Northeastern states—plus two fee-based businesses that have become increasingly important to the model: EPIC Retirement Plan Services and NBT Insurance Agency, LLC.

Financially, the momentum carried through the post-crisis years. Net income for the year ended December 31, 2024 was $140.6 million, or $2.97 per diluted common share, up from $118.8 million, or $2.65 per diluted common share, the year before. And the trend continued into 2025: first-quarter net income came in at $36.7 million, or $0.77 per diluted common share, compared to $33.8 million, or $0.71 per diluted common share, in the first quarter of 2024.

Leadership was evolving too. In May 2024, NBT completed a planned transition at the top. The Board unanimously approved the succession plan it had announced in January. Scott Kingsley—who joined NBT in 2021 as Executive Vice President and Chief Financial Officer—brought more than 35 years of experience, including 16 years on the management team at Community Bank System, Inc., where he served as Chief Operating Officer and previously as Chief Financial Officer. Earlier in his career, he worked at PricewaterhouseCoopers, LLP, before joining the Carlisle Companies.

And NBT kept leaning into the move it has made for decades when the timing and geography make sense: acquire, integrate, and expand in contiguous markets.

On May 2, 2025, the company completed the acquisition of Evans Bancorp, Inc., adding 200 employees and 18 banking locations in Western New York, along with $1.67 billion in loans and $1.86 billion in deposits.

Strategically, Evans did something simple but powerful: it brought NBT into Buffalo and Rochester, the two largest metro areas in upstate New York by population. As CEO Scott Kingsley put it, “We are enthusiastic about this opportunity to partner with Evans and are confident it is a high quality and incredibly impactful way to expand NBT's presence into Western New York. Adding the greater Buffalo and Rochester communities to the markets served by NBT is a natural geographic extension of our footprint in Upstate New York where we have been very active and successful for nearly 170 years.”

By the third quarter of 2025, the company was putting up record results. Net income was $54.5 million, or $1.03 per diluted common share. “For the third quarter of 2025, we achieved record net income and earnings per share, and we reported a return on average assets of 1.35% and a return on average tangible common equity of 17.35%,” Kingsley said.

The shareholder story kept its familiar rhythm, too. The Board approved an 8.8% increase in the quarterly cash dividend to $0.37 per share, marking the 13th consecutive year of dividend increases. Net interest margin improved to 3.59%. Total deposits reached $13.52 billion, and period-end total loans were $11.62 billion.

NBT also got an external stamp of approval, landing on the Forbes 2024 World’s Best Banks list. “At NBT, we remain dedicated to providing excellent customer experiences with every interaction,” said NBT Bank President and CEO John H. Watt, Jr. “This acknowledgment serves as a strong validation that our relentless efforts resonate positively with our valued customers.”

But the next chapter isn’t just about performance. It’s about pressure.

Upstate New York still comes with the realities of slower growth: population decline, aging communities, and fewer tailwinds than faster-growing regions. That’s part of why the New England expansion matters—it gives NBT exposure to more dynamic markets. And it’s part of why the commercial focus matters too. Serving businesses that feel overlooked by big banks optimized for scale and standardization is exactly where a relationship-driven bank can still win.

Then there’s the wave that’s crashing over every financial institution at once: AI and automation. Used well, it can take cost out of the back office, speed up routine servicing, and make the bank easier to do business with. Used poorly—or adopted too slowly—it can make a community bank feel dated overnight.

NBT’s core bet remains the same as it’s always been: technology should support the relationship, not replace it. The open question, for NBT and for every community bank still standing, is whether the industry’s next era will reward that balance—or punish anyone who can’t keep up with both the human side and the machine side at the same time.

XI. Business Model Deep Dive & The Playbook

At its core, NBT runs a community bank model that’s been refined over nearly 170 years without losing its original DNA: relationship banking built on actually knowing the customer, the business, and the town.

The revenue engine has three big moving parts. First—and still the largest—is net interest income: the spread between what NBT pays for deposits and what it earns on loans and securities. This is the classic banking flywheel, and NBT’s edge here starts with its deposit franchise. Community bank deposits tend to be sticky: local households with checking accounts, small businesses with operating balances, and municipalities managing public funds. Those customers generally don’t bolt at the first scary headline, and they aren’t always shopping for the absolute top rate the way “hot money” depositors do.

Second is fee income from wealth management, insurance, and retirement plan services. EPIC Retirement Plan Services is a national benefits administration firm based in Rochester, New York, with locations in St. Louis, Missouri, Peoria, Illinois, and Portland, Maine. The Company’s retirement plan services business also includes The TPA Experts with locations in New Gloucester, Maine, Bedford, New Hampshire, and West Des Moines, Iowa. NBT Insurance Agency, LLC is a full-service insurance agency based in Norwich, New York. These businesses help diversify revenue beyond interest income, and they create natural cross-sell opportunities with banking customers.

Third is transactional fee income from deposit accounts, card services, and other day-to-day banking activity. This is where fintech pressure is real—plenty of competitors advertise “free” banking. But for many customers, especially businesses, the value isn’t in a single fee. It’s in the bundled relationship: the service, the responsiveness, and the ability to get something solved by a person who can actually make a decision.

The loan book has also shifted with intent. The company’s loan portfolio comprises indirect and direct consumer, home equity, mortgages, business banking loans, and commercial loans; commercial and industrial, commercial real estate, agricultural, and commercial construction loans; and residential real estate loans. Over time, NBT has leaned more into commercial lending because that’s where relationship banking still shows up as an advantage. Commercial relationships are harder to commoditize and harder for fintechs to replicate, because they rely on judgment, context, and trust—not just speed.

NBT’s M&A integration playbook is another core capability. After decades of acquisitions, it has turned integration into a repeatable process: focus on contiguous markets, look for compatible cultures, keep local leadership in place to preserve relationships, consolidate back-office functions for efficiency, and keep the community bank experience intact on the front end. After the Evans acquisition, for example, three Evans executives stepped into leadership roles at NBT Bank. Ken Pawlak became President of the Western Region of New York and Buffalo Regional President. Tim Brown became Rochester Regional President. Audrey Meyers became Senior Territory Manager for Retail Banking in the Buffalo and Rochester markets.

The branch network still matters, even as its role keeps evolving. Branches provide physical presence and brand visibility. They’re where complex conversations happen, where trust is built, and where commercial relationships often start. But branches are also fixed costs, which is why optimization—closing underperformers, consolidating where it makes sense, and investing in high-traffic locations—remains a constant discipline rather than a one-time project.

If you had to pick the most important asset NBT has, though, it might be the one you can’t see on the balance sheet: its risk culture. The conservative underwriting that kept NBT out of subprime before 2008, and the balance sheet posture that helped it avoid SVB-style problems in 2023, reflects something that’s been reinforced for generations. It isn’t a policy you can copy and paste. It’s how the organization is wired to think about risk.

Capital allocation follows the same steady logic. The company has maintained dividend payments for 40 consecutive years, demonstrating remarkable financial stability. The dividend has increased for 13 consecutive years, signaling management confidence in sustainable earnings. Acquisitions are funded primarily with stock to preserve capital flexibility. Share repurchases are used opportunistically when valuations make sense.

XII. Porter's Five Forces & Hamilton's Seven Powers Analysis

To understand where NBT is strong—and where it’s exposed—you have to look at two things at once: what the banking industry is doing to everyone from the outside, and what NBT has built on the inside that actually holds up under pressure.

Porter’s Five Forces:

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate to low. Banking is still one of the most regulated businesses in America. You need a charter, capital, compliance muscle, and years of credibility. That said, fintechs have found workarounds—partnering with chartered banks or pursuing specialized charters—so “new entrants” show up less as new banks and more as new interfaces. The pressure is worst in commoditized products like payments and personal loans, and less intense in relationship-based commercial banking where trust and judgment matter.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Mixed, and getting tougher. Depositors are the key “suppliers” of funding, and in a higher-rate world they have more leverage. Banks have to pay up to retain balances, and that squeezes margins. The same thing is happening in talent: experienced bankers cost more because everyone is competing for them. And on the technology side, core processors and major vendors have power too—switching is painful, expensive, and risky.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate. On the lending side, sophisticated commercial borrowers can shop rates and terms. But a pure rate quote isn’t the whole product; local decision-making and relationship value still differentiate a bank like NBT, especially for businesses that want flexibility and responsiveness. Consumer borrowers have more options than ever—fintechs, megabanks, and comparison tools—yet many still stick with community banks for service and trust.

Threat of Substitutes: High, and rising. Digital-only banks can deliver many of the same services without branches. Private credit and other nonbank lenders have expanded into areas banks used to dominate. Payments and fintech platforms increasingly handle transactions that once required a traditional bank relationship. Crypto remains niche, but it’s still a long-term substitute threat for certain functions, especially as infrastructure matures.

Competitive Rivalry: Intense. NBT faces megabanks with enormous scale and technology budgets, regional peers running similar playbooks, credit unions with tax advantages, and fintechs built with lower cost structures. The Northeast is especially competitive, with multiple strong regional franchises packed into overlapping markets.

Hamilton’s Seven Powers:

Scale Economies: Moderate. NBT does get real benefits from being a regional bank rather than a single-market community bank: fixed costs spread across a larger base, and technology spend amortized across more customers. But banking scale isn’t like software scale, and megabanks still have dramatically greater advantages here.

Network Effects: Limited. Banking doesn’t get materially better for existing customers just because more customers join. The closest thing is a weak form in commercial banking, where local concentrations and relationships can create referral flywheels.

Counter-Positioning: Meaningful. NBT’s core model—relationship banking with local decision-making—stands in contrast to megabanks built around centralized systems and algorithmic efficiency. The biggest banks can’t easily replicate the “local” experience without giving up the cost structure and standardization that make them big-bank machines in the first place.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Business banking can be sticky: changing accounts, moving treasury management, rebuilding permissions, and re-establishing credit relationships is real work. Consumer banking is easier to switch, but it still comes with friction—direct deposit changes, bill pay updates, linked accounts, and general inertia.

Branding: Strong locally. Uninterrupted dividend payments since 1857 isn’t just a trivia fact—it’s a trust signal built over generations. In banking, especially during moments of panic, that kind of reputation matters. The “community bank” identity also carries weight for customers who distrust large institutions or want local relationships.

Cornered Resource: Yes. NBT’s deposit franchise in specific geographies is a cornered resource in the practical sense: relationships built over decades are hard to dislodge and even harder to recreate quickly. The same goes for local market knowledge and community ties, which can translate into informational advantages in underwriting.

Process Power: Yes. Two processes stand out: conservative underwriting through cycles, and a repeatable M&A integration playbook. Those aren’t slogans—they’re organizational capabilities that have been developed, tested, and reinforced over decades.

Where NBT’s Real Moat Lies:

NBT’s moat starts with deposits. Sticky, relationship-based funding tends to be more stable and, over time, cheaper than rate-chasing “hot money.” That deposit base is what makes the rest of the model work.

The second moat is cultural: the discipline to say no. In banking, avoiding one disastrous category of risk can matter more than winning a dozen growth initiatives. NBT’s risk management culture has endured through cycles and leadership changes because it’s embedded in how the bank operates, not bolted on as a policy.

Where NBT Is Vulnerable:

Scale cuts both ways. Competing with megabanks means competing with technology budgets NBT can’t match dollar-for-dollar. Core upstate New York markets also face demographic headwinds over the long run. And like every bank with commercial real estate exposure, NBT operates under uncertainty as remote work and shifting demand reshape parts of the office market.

XIII. Bull Case vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case:

The bull case for NBT rests on a handful of advantages that tend to matter most in banking—especially when the cycle turns.

First is management and culture. NBT has now been tested in three very different crises—2008, 2020, and 2023—and it came through without the kind of existential balance-sheet damage that took out less disciplined peers. That track record buys credibility, and management has continued to frame recent performance as the product of steady execution. As the company put it, “These results reflect productive growth in earning assets, deposits, and our sixth consecutive quarter of net interest margin improvement, including a full quarter of our merger with Evans Bancorp, Inc. completed in May.”

Second is the deposit franchise. Relationship-based deposits are the closest thing banking has to a moat: they’re typically less price-sensitive than institutional “hot money,” and they’re more likely to stick around when fear hits the system. The 2023 crisis was a live-fire demonstration of that advantage across the industry, and NBT benefited from the same dynamic—trust moving deposits toward banks that felt stable and familiar.

Third is consolidation optionality. Banking is still shrinking in terms of the number of institutions, and NBT has proven it can be the acquirer—not just the one hoping not to get acquired. Its ability to integrate deals and keep local relationships intact gives it a path to grow even when organic growth is slow. In a sector where weaker players eventually need an exit, that matters.

Fourth is valuation. Regional bank stocks were hit hard in the post-2023 hangover, and NBT’s stock has been pulled down with the group despite its more conservative posture. If sentiment toward the sector ever normalizes, a higher-quality franchise trading at depressed multiples has room to re-rate.

Fifth is geographic diversification. NBT’s footprint across seven states helps reduce the risk of being overly tied to any single local economy. The company’s expansion into New England also matters strategically, because it provides exposure to markets with stronger growth dynamics than many of its legacy upstate New York towns.

Sixth is the rate environment—at least so far. Higher rates have been a tailwind for profitability, and NBT’s net interest margin continued to improve into 2025. In the third quarter of 2025, NIM on an FTE basis was 3.66%, up slightly from the second quarter. With an asset-sensitive balance sheet, NBT has been positioned to benefit as assets reprice.

The Bear Case:

The bear case is less about one big blow-up risk and more about the slow, grinding pressures that make regional banking a hard business.

First, the entire category is under structural pressure. Regulation keeps getting heavier, and compliance costs don’t scale down nicely. Technology investment is mandatory just to stay relevant, and at NBT’s scale it’s not always obvious those dollars earn software-like returns. Meanwhile, competition—from fintechs, megabanks, and credit unions—doesn’t let up.

Second, the home market problem is real. Upstate New York faces long-running demographic headwinds: slower population growth, aging communities, and limited economic dynamism in many areas. That makes organic growth harder, and it raises the importance of execution elsewhere.

Third, commercial real estate is a lingering question mark for every bank. Office demand has been reshaped by remote work, and parts of retail continue to fight e-commerce gravity. NBT’s exposure is largely in smaller markets that can behave differently than major urban cores, but “less exposed” is not the same as “no risk.”

Fourth, independence isn’t guaranteed. In a consolidating industry, NBT could become a target. Shareholders might get a premium, but the long-term compounding story ends the day the deal closes.

Fifth, net interest margin can swing the other way. The same asset sensitivity that helped as rates rose can become a headwind if rates fall and yields reset downward faster than funding costs.

Sixth, there’s the people problem. Banking is still a relationship business, which means talent matters—and talent is expensive. Larger institutions can often outbid smaller ones for experienced commercial bankers, making retention and recruiting a constant contest.

Key Metrics to Watch:

If you’re monitoring NBT, three things do most of the work in telling you whether the story is strengthening or fraying:

-

Net Interest Margin (NIM): This is the heartbeat of a community bank. Watch the direction, not just the level—especially what’s driving it: funding costs, loan yields, and how competitive deposit pricing is getting.

-

Deposit Cost and Beta: This is the real-time test of deposit quality. If NBT can hold onto deposits without paying up aggressively as market rates move, that’s evidence the franchise is relationship-driven. If deposit costs jump quickly, it can signal more rate-sensitive funding.

-

Nonperforming Loans and Net Charge-offs: Credit quality is where “boring” banks prove they’re boring. Any sustained deterioration matters more than a single quarter’s noise. NBT’s provision for loan losses rose to $7.6 million from $2.2 million in the previous quarter—worth watching closely, but still within a range the company has described as manageable.

XIV. Epilogue & Reflections

So what does NBT Bancorp’s 168-year run actually teach us about surviving—and compounding—in one of the most unforgiving industries in America?

Start with the most counterintuitive lesson: boring can be a competitive advantage.

Banking has a long history of turning “innovation” into shareholder value destruction. Different decade, different packaging: the savings and loan crisis, the mortgage machine that detonated in 2008, the duration-and-uninsured-deposits cocktail that took out banks in 2023. Against that backdrop, NBT’s defining skill has been the willingness to say no.

No to subprime when everyone else was getting rich. No to complicated structures that looked like free money. No to building a funding base that could disappear in a group chat. Each time, the bank gave up some short-term juice. Each time, it bought itself another decade of staying power.

Underneath that is the harder-to-copy ingredient: culture.

Conservative underwriting isn’t just a credit policy you paste into a binder. It’s a shared reflex—a way of making decisions that has to hold up when the incentives are screaming at you to loosen up. NBT managed to carry that reflex through leadership transitions, changing technology, shifting products, and multiple economic cycles. That kind of continuity is rare, and in banking, it’s worth a lot.

Then there’s the relationship-banking thesis, which has been pronounced dead more times than the branch itself.

For years, the story was that technology would make community banks obsolete—that algorithms would do the job faster and cheaper, and branches would be relics. But the last few years offered a reality check. In 2020, when PPP rules were changing by the hour, small businesses didn’t want a slick interface. They wanted a person who would pick up the phone and help them get it done. And in 2023, when confidence cracked, depositors didn’t look for the cleverest app. They looked for a name they trusted.

Technology matters, and it will keep mattering. But in banking, trust is still the real moat.

NBT’s dividend record is maybe the cleanest proof point of what that trust-and-discipline model produces. The company has made uninterrupted dividend payments since 1857. That means it kept paying through financial panics, wars, depressions, inflation shocks, the savings and loan crisis, 2008, COVID-19, and the 2023 banking panic. That isn’t luck. It’s an institution built to endure.

The bigger takeaway is that community banking isn’t dead. It’s just selective.

Not every market can support it. Not every bank has the discipline to execute it. But in the right geographies, with the right culture, and with a strategy built around relationships instead of volume, the model can still work—and can still win customers precisely when the system is under stress.

As for what comes next, the outline is familiar. NBT will likely keep leaning into acquisitions in and around its footprint, because the industry is still consolidating and scale still matters. The Evans acquisition brought Buffalo and Rochester into the franchise—two of the largest metro areas in upstate New York—and that creates room for both organic growth and deeper commercial relationships.

NBT will also keep walking the same tightrope every community bank faces: invest enough in technology to stay competitive, without trying to outspend megabanks on features that don’t differentiate. The bet, consistent with its history, is that technology should support the relationship—not replace it.

And demographic headwinds in parts of upstate New York won’t vanish. That’s why the New England expansion matters, and why the continued push toward commercial banking matters too: it puts the franchise in markets and customer segments where the relationship advantage is more valuable.

For long-term investors, NBT is ultimately a bet that relationship banking still has a future—even in a world of AI, fintech, and relentless competition. The past 168 years suggest that bet isn’t naive. Whether the next 168 look anything like the first is unknowable.

But very few institutions earn the right to even ask that question.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

If you want to go deeper—either into NBT specifically or into why community banking still works at all—here are the sources that add the most color and credibility:

-

NBT Bancorp SEC Filings (10-K Annual Reports, 10-Qs, 8-Ks): The primary source for the facts: financial performance, risk disclosures, management’s discussion, and the unvarnished version of what the bank thinks could go wrong. These are available on SEC.gov. The most revealing reads tend to be the 10-Ks from stress years (2008–2009, 2020, and 2023), because management has to explain decisions when the stakes are real.

-

NBT Bancorp Investor Presentations and Annual Reports: Found on the company’s investor relations site. These are the “how we want you to understand the business” versions—strategy, priorities, and key metrics in a more digestible format than a 10-K.

-

FDIC Historical Banking Statistics and Quarterly Banking Profiles: Great for zooming out. If you want to understand consolidation, profitability trends, credit cycles, and what the regulatory environment has done to community banks, this is the baseline dataset.

-

Federal Reserve papers on community banking: Research that gets into what drives community bank outcomes—why relationship banking can be durable, where it breaks down, and how regulation and technology change the economics.

-

"NBT Bank: A History of Growth and Change 1856-2016": NBT’s own historical publication. It’s not an independent critique, but it’s a detailed narrative of how the institution evolved over its first 160 years—and it’s invaluable for understanding how the bank sees itself.

-

American Banker archive coverage: Contemporary reporting on NBT’s acquisitions and crisis-era decisions. It’s useful precisely because it captures what people thought in the moment, before the outcome was obvious.

-

S&P Global Market Intelligence / SNL Financial regional bank coverage: For numbers-driven readers: peer comparisons, industry screens, and a way to benchmark NBT against other banks running similar playbooks.

-

NYU Stern’s "SVB and Beyond: The Banking Stress of 2023": A strong framework for understanding the mechanics of the 2023 panic—interest rate risk, uninsured deposits, confidence shocks—and why some banks failed while others, including NBT, held steady.

-

Community Banking in the 21st Century Conference Proceedings: Research and practitioner perspectives hosted jointly by the Federal Reserve and CSBS. It’s one of the best places to see what community bank leaders and regulators are actually worried about—often a few years before it shows up in headlines.

-

Hamilton Helmer’s "7 Powers": A strategy lens that helps translate banking from “spreads and ratios” into something closer to competitive advantage—process power, branding, switching costs, and what a moat looks like when your product is trust.

NBT’s story, of course, isn’t over. It’s still being written—quarter by quarter, acquisition by acquisition, crisis by crisis—in the branches and boardrooms of a bank that’s been forced to adapt for nearly 170 years without losing the core promise it started with: be the place people trust when they need money to move, plans to get made, or problems to get solved.

If you’re trying to understand the durability of relationship banking, there aren’t many case studies cleaner than this one.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music