Myers Industries: From Rubber Tires to Material Handling Innovation

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

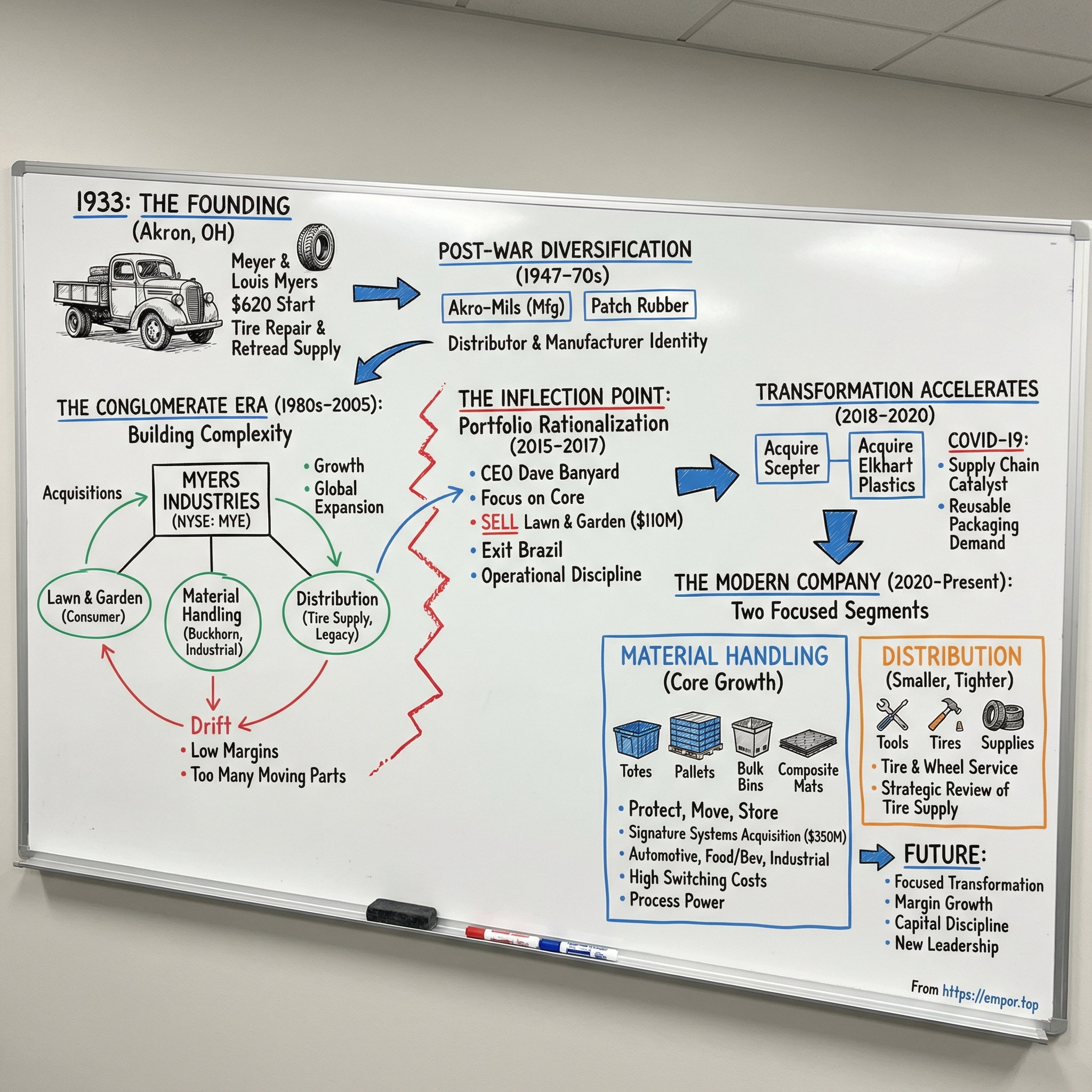

Picture this: a gray morning in Akron, Ohio, in 2015. In a nondescript industrial conference room, a group of executives is staring down a decision that would’ve sounded like heresy just a decade earlier.

Myers Industries has been tied to tires since the Great Depression. That legacy isn’t just in the history books—it’s baked into the company’s identity. And yet here they are, seriously debating whether to sell off the entire distribution segment that traces its roots back to the founder’s original business.

That moment is the doorway into this story.

Because Myers is the kind of company most people—and frankly, most investors—never notice. It doesn’t make headlines. It doesn’t “disrupt” anything. It makes the quietly essential stuff that keeps factories, warehouses, and supply chains moving: plastic pallets, reusable containers, bulk bins. The products are unglamorous. The markets are industrial. The work is steady, physical, and precise.

And that’s exactly why it’s interesting.

This is the story of an $800-million-plus industrial company that had to relearn what it was. Over decades, Myers had grown into a complicated, low-margin conglomerate. The path back wasn’t a flashy new invention. It was focus. Operational discipline. And, most importantly, the willingness to admit that a legacy business can be a weight—not an asset.

The central question sounds simple: how did a small-town Ohio tire retreader become a leader in reusable packaging and material handling?

The answer runs through multiple near-death moments, activist pressure, hard internal debates, and painful divestitures. It’s also a counterintuitive kind of turnaround: Myers didn’t buy its way into greatness. In many ways, it sold its way there. It shrank to get healthy—walking away from huge chunks of revenue to become something better.

Today, the company operates in two core segments: Material Handling and Distribution. For the full year 2024, Myers reported $836.3 million in net sales, up from $813.1 million the year before, delivering sustainable plastic and metal solutions designed to protect and move products through modern supply chains.

In this deep dive, you’ll see how a business founded during the Great Depression by two brothers with six hundred dollars and a used truck evolved into a case study in corporate transformation. We’ll follow the arc of American industrial conglomerates—the boom, the bust, and the eventual realization that “more businesses” doesn’t always mean “more value.” And we’ll dig into the hidden strength inside so-called boring companies, where the real advantage comes from doing a few things exceptionally well.

Let’s start where all good stories do—at the beginning.

II. Post-War Industrial America & The Founding Vision (1933–1970s)

In 1933, Akron, Ohio wasn’t the kind of place that rewarded big dreams. The Great Depression had hollowed out the city. Jobs vanished, banks folded, and factory floors went quiet.

But for Meyer and Louis Myers—two brothers who’d grown up around tires—that misery also created a very specific kind of demand. When people can’t afford new tires, they stretch the life of the ones they already have. Repair. Patch. Retread. Keep the wheels turning one more mile.

So the brothers did what good operators do in bad times: they started small and aimed directly at what the market needed. In 1933, they scraped together $620, bought a used truck, stocked a handful of tire repair merchandise, and opened a tire repair and retreading supply business in Akron. That modest start became Myers Industries.

They weren’t guessing. Louis had worked for a local tire patch company. Meyer ran his own used tire store. They understood not only the customer, but the psychology of the customer under pressure. In Depression economics, tire repair wasn’t a compromise—it was survival. And that turned retreading into a thriving, steady business.

Akron helped, too. By the mid-1930s, the U.S. tire industry had effectively consolidated into four dominant players—Goodyear, Firestone, B.F. Goodrich, and U.S. Rubber (later Uniroyal)—collectively supplying the vast majority of tires in the country. And all but Uniroyal were headquartered in Akron. This wasn’t Silicon Valley. It was Rubber Valley, a dense cluster of expertise, suppliers, and customers that made the city the “Rubber Capital of the World.”

That status had been decades in the making. Akron had exploded in the 1910s and 1920s, becoming America’s fastest-growing city for a stretch. The tire giants even built neighborhoods for their workers—Goodyear Heights, Firestone Park. The industry wasn’t just a big employer; it was the city’s identity. As one longtime industry employee, Alan Peterson, later put it: “We were the Rubber Capital of the World.” He graduated from college and went to work at General Tire in 1954—one more data point in a region where rubber wasn’t a niche, it was a career path.

Myers Tire Supply quickly found its footing. Within six years, business was strong enough to bring a third brother, Isidore, into the operation. The company specialized in supplying the equipment and consumables that tire service shops relied on every day: patches, wheel-balancing and alignment hardware, tire-valve parts, and all the tools of the trade—jacks, hand tools, air compressors, tire changers, display and storage units, and vulcanizing machines used in retreading.

And retreading itself wasn’t some back-alley hack. It was technical, precision work. Vulcanizing—bonding new rubber to a worn tire carcass—required the right chemicals, the right temperatures, and careful control. Get it wrong and you didn’t just disappoint a customer; you could create a catastrophic failure on the road. Myers became a trusted source for the equipment and materials that made the process consistent and safe.

Then World War II arrived and remade American industry. The war effort didn’t just pull the U.S. out of the Depression; it put rubber at the center of military mobility—truck tires, airplane tires, Jeep tires. But there was a looming problem: the U.S. supply of natural rubber, largely from Asia, was cut off by Japan. The solution was synthetic rubber, first developed by German scientists during World War I when their own natural rubber supply was severed. Now the U.S. faced the same constraint—and Akron’s rubber companies responded by shifting development and production toward synthetic rubber.

Myers rode that post-war industrial wave, but the truly defining move came just after. In 1947, the company diversified into manufacturing by creating Akro-Mills Inc. and Patch Rubber Co. Those businesses became the core of Myers’ manufacturing operations—and introduced a two-part identity that would shape the next several decades: manufacturer and distributor.

Akro-Mils, founded by Louis and Isidore on October 4, 1946, took its name from Akron plus the brothers—Meyer, Isidore, and Louis—along with their original last name, Schneiderman. This wasn’t diversification for its own sake. The brothers saw the vulnerability in being a pure distributor. Manufacturing meant control—over product, margins, and destiny.

Akro-Mils began as a mail-order business under Isidore’s direction. It started manufacturing its own products in 1964 and later expanded overseas. Looking back, the move into manufacturing proved especially well-timed. In a 1986 interview with Barron’s, Chairman Louis Myers noted that cycles in distribution and manufacturing usually offset one another, producing steadier growth.

That logic—that counter-cyclical business lines create stability—became one of Myers’ strengths. It also planted the seed for a future problem. If one side slowed down, the other side could carry the company. And because the company could keep moving without confronting trade-offs, it didn’t have to make hard decisions about which business truly deserved capital, attention, and leadership focus.

By 1971, Myers had grown enough to go public. The Myers family sold a minority stake to the public markets. Over the rest of the decade, revenues climbed and profits grew alongside them. In 1983, Myers Industries was listed on the American Stock Exchange.

By the time it became a public company, Myers was no longer just “Everything for the Tire Dealer.” It was a diversified manufacturer and distributor serving industrial customers across multiple categories. It looked like progress. The question that would define the next fifty years was whether that expansion was disciplined strategy—or the beginning of opportunistic drift.

III. The Diversification Era: Building an Industrial Conglomerate (1980s–2000s)

Stephen L. Myers took the CEO job in 1980 with a straightforward mission: make the company bigger. He’d spent more than a decade inside the family business and now, as Louis Myers’ son, he inherited a firm with deep roots in tire distribution and a growing manufacturing footprint. The next step, in his mind, wasn’t to protect what they had. It was to expand it.

And in corporate America at the time, expansion had a script.

The 1980s were the high era of the industrial conglomerate. The playbook was familiar: buy adjacent companies, stack up product lines, and use your distribution network to sell more things to more customers. Diversification wasn’t considered messy—it was considered prudent. If one market went soft, another would carry you.

Myers leaned into that logic, and the defining move arrived in 1987: the acquisition of Buckhorn, Inc., an Ohio-based manufacturer of reusable plastic containers. The deal cost $40 million—$22 million in cash plus $18 million in assumed debt—and it changed the company’s center of gravity overnight. Sales jumped sharply from 1986 to 1987, and manufacturing became more than half of total revenue. Myers wasn’t primarily a distributor anymore. It was becoming a plastics manufacturer with a distribution engine attached.

Buckhorn also landed at exactly the right time. Two trends were reshaping supply chains in the late ’80s and early ’90s: rising environmental awareness and the spread of just-in-time inventory systems. As Crain’s Cleveland Business noted in 1988, just-in-time meant smaller, more frequent shipments—which meant more containers moving through more loops. Buckhorn’s products fit that world perfectly.

By the early 1990s, Buckhorn’s reusable containers were everywhere: food, apparel, electronics, automotive parts, health and beauty, hardware, agriculture, and inside factories for in-plant handling. Tote boxes, bins, tubs, straight-walled boxes, modular cabinets—the kind of standardized, durable plastic infrastructure that quietly keeps production lines fed and warehouses organized. The company sold both directly and through independent dealers and product reps.

Buckhorn also brought something else with it: consumer lawn and garden products—tool boxes, storage containers, planters—distributed widely through mass merchandisers, department stores, hardware chains, warehouse outlets, and specialty shops. It wasn’t a clean, single-threaded portfolio. It was variety, and in that era, variety looked like strength.

From there, the deal machine kept running. In 1992, Myers bought Alpha Technical Systems (renamed Myers Systems), an Ohio manufacturer of material handling systems like conveyors and hoists. In 1995, it acquired Ameri-Kart Corp., which produced municipal, industrial, and commercial waste handling and collection products.

By the mid-1990s, Myers had effectively become three companies under one ticker:

- Lawn & Garden, selling plastic pots, planters, and decorative consumer goods

- Material Handling, producing reusable packaging, pallets, and bulk containers for industrial customers

- Distribution, still anchored in tire service supplies and equipment—the original business

On paper, the rationale was tight. Cross-selling. Shared plastics know-how. Scale in polyethylene. Manufacturing processes that could be applied across multiple product lines.

And the numbers looked like validation. Through the 1980s, the company added 11 Myers Tire Supply branches, reaching 37 by 1990. Revenue grew from $67.5 million in 1980 to $194.8 million by 1989, while net income rose from $3.4 million to $9.6 million.

The 1990s brought more of the same. By 1996, Myers Tire Supply had 42 domestic branch outlets. Company revenue climbed from $195.6 million in 1991 to nearly $321 million in 1996, and profit increased from $10.5 million to more than $21 million over the same period.

Management described the strategy as aggressive expansion, and they weren’t shy about the formula: reinvest heavily in production capacity, keep debt low, and keep acquiring. Geographic expansion was also part of the story, with special attention on Asia and the Pacific Rim during the 1990s. They planned annual investments of $15 to $20 million through the end of the century to expand capacity, improve efficiency, and develop new products. In 1993, Smith Barney Shearson analysts summed up the market’s view: “a tightly managed company with a focus on disciplined, long-term growth.”

In 2001, Myers moved up another rung in visibility, listing on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol MYE.

By 2005, Myers hit a new peak: record net sales of $903.7 million. A business that began with $620 and a used truck was now brushing up against a billion dollars in revenue. It had also become—by many accounts—the largest wholesale distributor of tire servicing equipment and supplies in the world.

Under the hood, the manufacturing side had become legitimately sophisticated. Rotational molding and blow molding were now core capabilities, and those aren’t “press a button and out comes plastic” processes. They require real expertise: mold design, polymer behavior under heat and pressure, material formulations tuned to specific use cases, and the operational discipline to make consistent parts at scale. This was specialized industrial production.

But the bigger Myers got, the harder it became to answer a simple question: what business are we actually in?

Because beneath the growth was a portfolio that was getting harder to manage and even harder to judge. Lawn & Garden was seasonal and tied to consumer spending. Distribution demanded heavy working capital and lots of inventory. Material Handling served industrial customers with longer sales cycles—but also stickier relationships and higher switching costs once a container became part of a production process.

And here was the uncomfortable truth that rarely shows up in celebratory annual reports: a lot of what Myers owned was, at its core, low-margin and increasingly commodity-like. Diversification was supposed to smooth the ride. Instead, it was building complexity—layer by layer—until it became difficult to see which parts of the company were creating real value, and which parts were quietly dragging everything down.

IV. The Lost Decade: Struggling with Complexity (2005–2014)

When the Great Recession hit in 2008, Myers Industries learned the hard way what “diversified” really meant. The downturn wasn’t a quick shock—it was a long, grinding collapse followed by an unusually slow recovery. The economy shrank sharply, unemployment spiked, and industrial demand fell off a cliff.

Myers was exposed from every angle at once.

Lawn & Garden, which looked steady in good times, turned out to be tied to the housing market and consumer confidence more than anyone wanted to admit. As homeowners pulled back and construction projects froze, retail nursery and garden center demand dried up. At the same time, automotive customers—an important end market for Material Handling’s reusable containers—cut production hard. U.S. manufacturing took a major hit overall, and Myers felt it in orders, plant utilization, and pricing.

Even the legacy tire distribution business—supposedly the “defensive” part of the portfolio—didn’t provide the protection you’d expect. Yes, vehicles still needed maintenance. But fleet customers delayed equipment purchases. Service centers tightened inventory. And the core physics of distribution didn’t change: it soaked up working capital. In a downturn, that meant cash drain.

This was the dark side of the conglomerate logic. Diversification hadn’t smoothed the ride—it had created a company that was spread across businesses with different cycles, different economics, and different operational needs. And management attention was split three ways, which meant none of the problems ever got fully solved.

Leadership churn didn’t help. John C. Orr became CEO in 2005 and guided the company through the recession, but the post-crisis years still didn’t produce a clean strategic identity or compelling returns. The board would later credit him with positioning Myers as a value-added manufacturer with strong positions in agricultural, industrial, and automotive markets. But “positioning” wasn’t the same as performance—and the market could tell the difference.

By the early 2010s, the portfolio problem was no longer theoretical. It demanded action.

In June 2014, Myers announced its intent to sell the Lawn & Garden business. In January 2015, it signed a definitive agreement with Wingate Partners. And then the company closed the sale: Myers Industries completed the divestiture of Lawn & Garden to an entity controlled by Wingate Partners V, L.P., a Dallas-based private equity firm, for $110 million.

This wasn’t just a transaction. It was a public admission that the company couldn’t keep being everything to everyone.

The sale included manufacturing facilities and offices across Twinsburg and Middlefield, Ohio; Sparks, Nevada; Sebring, Florida; Brantford and Burlington, Ontario. Lawn & Garden had generated about $188 million in net sales in 2014. Myers was walking away from a meaningful chunk of revenue—roughly a quarter of the company—because it no longer fit the future.

Management tried to frame it plainly. After what it described as a detailed evaluation, the company and board concluded the Lawn & Garden segment “has the greatest opportunity as part of an organization that is strategically focused on its primary markets for future growth.” In other words: someone else could run this better, and Myers needed to stop carrying it.

Then came the leadership reset.

In December 2015, the board unanimously elected R. David Banyard as the company’s next President and CEO, succeeding Orr. The subtext mattered as much as the announcement: Banyard’s background included Danaher Corporation and Roper Technologies—two names synonymous with operational discipline and a relentless focus on what drives returns.

The chairman made the board’s intent clear: they’d run a comprehensive search, and they believed Banyard had the leadership profile and industry experience to lead what came next.

Banyard, for his part, signaled a simpler story than Myers had told in years. He believed the now re-focused Material Handling and Distribution segments had attractive prospects for growth and value creation—and he wanted to take them to the next level.

The market wasn’t impressed yet. Myers stock had effectively gone nowhere for a decade. To investors, this still looked like another industrial company promising a turnaround after years of drift.

But under the surface, the tone was changing. Activist pressure that had been building through the early 2010s forced harder conversations about where the real value was. Some investors looked at Material Handling and saw a good business trapped inside a complicated company—its economics obscured by the rest of the portfolio. Myers could point to financial discipline, including maintaining dividend payments for 53 consecutive years. But the stock price told you what Wall Street believed: discipline wasn’t the same as a plan.

As 2016 approached, the question wasn’t whether Myers needed to change. That part was settled.

The question was whether a new CEO could actually finish the transformation—by doing the hardest thing for an old industrial company: choosing what not to be.

V. The Inflection Point: Portfolio Rationalization Begins (2015–2017)

The real inflection point for Myers Industries came when leadership stopped treating Material Handling like “one of three segments” and started seeing it for what it was: the best business in the building.

The tire distribution operation had history on its side. It traced straight back to the founders. It had branches, relationships, and decades of muscle memory. But the more management studied the portfolio, the clearer the contrast became. Material Handling was riding structural tailwinds that distribution simply didn’t have—reusable packaging demand, tighter food safety standards, and industrial customers who were redesigning their supply chains around returnable systems.

The difference showed up most clearly in how customers behaved.

In a tire shop, switching is easy. If a competitor has the same patches and supplies at the right price, a buyer can move without much pain. Availability and cost drive the decision, and loyalty is thin.

Material Handling is the opposite. When an automotive manufacturer designs a production line, packaging isn’t an afterthought—it’s part of the system. Components are engineered to arrive to the right station, in the right sequence, in containers designed for that exact part and that exact workflow. Those reusable containers are often purpose-built, with tooling created specifically for the application. They get integrated into plant routines, logistics routes, and training. Changing suppliers can mean revalidating packaging, reworking the flow, and risking downtime. The switching costs are real, and they’re expensive.

Once Myers recognized that, the playbook shifted from “manage the whole portfolio” to “protect and build the parts that actually compound.”

That meant shedding non-core operations, even when doing so wasn’t comfortable. One clear example was the decision to exit Brazil. As President and Chief Executive Officer Dave Banyard put it: “We are pleased to have reached this agreement, as this strategic transaction will allow us to better focus energy and resources on targeted niche markets where we see opportunities for stronger growth and value creation for the Company. Our exit from Brazil should improve our future cash flow generation.” In 2016, the combined Brazilian entities generated about $24 million in revenue—meaningful, but not central to where Myers wanted to go.

The operational changes ran just as deep as the portfolio changes. Lean manufacturing initiatives went after waste in the system. Footprint optimization meant closing underperforming plants—painful decisions for workers and communities, but necessary for a company that had accumulated too many facilities for too many different businesses.

And Material Handling kept proving it deserved the attention. Buckhorn’s reusable plastic containers had long been used across food, apparel, electronics, automotive components, health and beauty, hardware, in-plant handling, and agriculture. The product lineup—tote boxes, bins, tubs, straight-walled boxes, modular cabinets—wasn’t flashy, but it was foundational. And the manufacturing know-how behind it mattered. Processes like rotational molding and injection molding are technical, experience-driven crafts. They’re hard to get right consistently, and they’re not something a pure distributor can copy with a phone call and a purchase order.

As the strategy clarified, a few trends pulled everything into focus:

Reusable packaging was accelerating. Companies facing pressure to reduce waste were rethinking single-use packaging. Reusable containers cost more upfront, but over time they often delivered a much lower total cost of ownership.

Automotive was moving to returnable containers. Lean manufacturing and just-in-time delivery demanded predictability. Cardboard introduced variability. Custom reusable plastic removed it.

Food and beverage safety requirements were driving plastic adoption. Plastic could be cleaned and standardized in ways that wood and corrugate struggled to match. It also opened the door to tracking and traceability tools like RFID.

Sustainability wasn’t just marketing—it had real ROI. When customers accounted for purchasing, disposal, and compliance costs, reuse frequently penciled out even before any brand benefit entered the conversation.

Wall Street didn’t reward Myers for this immediately. After a decade of drift, investors were conditioned to doubt industrial turnaround narratives, and analysts still tended to lump Myers into the category of “just another struggling industrial.” The changes were real, but they were incremental—no overnight reinvention, no headline-grabbing pivot.

But inside the business, the trendline was turning. Margins improved. Cash flow strengthened. And for the first time in years, Myers wasn’t trying to be a little bit of everything. It was becoming deliberate about being great at something.

VI. The Transformation Accelerates: Shedding More Legacy (2018–2020)

By 2018 and 2019, Myers’ transformation stopped looking like a set of isolated clean-up moves and started looking like a real repositioning. Management wasn’t just trimming around the edges. It was using the balance sheet to build up Material Handling with acquisitions that fit the strategy, while continuing to back away from anything that didn’t.

One deal in particular made the direction obvious. Myers completed the $157 million acquisition of Scepter Corp. and Scepter Manufacturing LLC, a producer of portable marine fuel containers, portable fuel and water containers and accessories, ammunition containers, storage totes, and environmental bins. Scepter had about $100 million in 2013 sales and trailing twelve months EBITDA of $23.5 million, and Myers said the deal would be immediately accretive to adjusted earnings per share.

At the time, then-CEO John C. Orr pointed out that “Scepter is the third acquisition to the company’s Material Handling unit in the last two years.” That line mattered. Myers was telling the market, plainly, what it intended to become: bigger and stronger in Material Handling, and less distracted everywhere else.

Then came 2020, and with it, the moment that both validated the strategy and put it under real stress.

As COVID-19 tore through global supply chains, Myers announced it had acquired the assets of Elkhart Plastics, Inc., one of the largest rotational molding companies in the United States. The acquisition was framed as part of a long-term plan to transform Myers into a high-growth, customer-centric innovator of value-added engineered plastic solutions.

Elkhart, headquartered in South Bend, Indiana, had six U.S. manufacturing facilities and about 460 employees. In 2019, its revenues were approximately $100 million, with an adjusted EBITDA margin of about 9%.

Strategically, the fit was straightforward: pair Elkhart with Myers’ Ameri-Kart business and you create the fifth-largest rotational molding business in the United States. Financially, Myers expected annual cost synergies of roughly $4 million to $6 million, with most of that projected to show up within the first two years.

Leadership was also changing. Mike McGaugh, who took the CEO role in 2020, laid out the priorities in plain language: “We recently launched our new, long-term strategic plan which, in the near term, is focused on strengthening the Company through organic growth initiatives, commercial and operational excellence, pursuing bolt-on acquisitions in plastics molding, and driving a high-performing culture.”

COVID created a strange kind of clarity across industrial America. It didn’t invent supply-chain fragility; it exposed it. Suddenly, a “high-performing supply chain” wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was a competitive necessity. Companies learned, the hard way, that suppliers with reliable delivery and domestic manufacturing footprints were worth paying for.

That shift benefited Myers. An EY survey found that in 2020, 60% of executives said the pandemic increased their supply chain’s strategic importance. Myers’ customer base—automotive OEMs, food processors, agricultural businesses—needed partners who could deliver consistently under pressure.

And on the Distribution side, Myers Tire Supply told customers it was responding proactively, increasing inventory levels, enhancing its supply chain, and developing processes to better support customers during the pandemic.

At the same time, end markets like food and beverage, medical, and e-commerce surged—areas where reusable packaging is essential infrastructure. When disposable packaging ran into shortages, reusable alternatives didn’t just look sustainable. They looked dependable.

By now, the company’s shape was changing in a way that would’ve sounded backwards a decade earlier. Myers was moving from a $900 million conglomerate with too many moving parts toward a smaller, more focused specialist with better margins and a clearer story. Shrinking to grow worked because the pieces it shed were low-margin, capital-intensive, and strategically distracting. As Myers simplified, it could put more management attention into making Material Handling better, and more capital into manufacturing capability and targeted acquisitions.

The operational side had to catch up to the portfolio strategy, too. In 2020, Myers began looking for a way to integrate its planning function across six business groups serving multiple markets and product types. As Jeff Baker, senior vice president of shared services, put it: “There was no consistency within our supply chain approach or best practices,” and fixing that became part of the transformation.

VII. The Modern Company: Two Focused Segments (2020–Present)

Today, Myers Industries looks nothing like the sprawling, hard-to-explain conglomerate it was in the early 2000s. The company now reports in two core segments: Material Handling and Distribution. In Material Handling, Myers engineers and manufactures plastic and metal products designed to protect, move, and store goods—durable, reusable infrastructure for modern supply chains.

Material Handling is now the center of gravity. The segment spans pallets, small parts bins, bulk shipping containers, storage and organization products, custom plastic solutions, and molded components made through injection molding, rotational molding, and blow molding. It also includes consumer fuel containers and tanks used in water, fuel, and waste handling. Those products show up across industrial manufacturing, food processing, retail and wholesale distribution, agriculture, automotive, recreational and marine vehicles, healthcare, appliances, bakeries, electronics, textiles, and a range of other end markets—sold under brands like Akro-Mils, Jamco, Buckhorn, Ameri-Kart, Scepter, Elkhart Plastics, Trilogy Plastics, and Signature Systems, both directly and through distributors.

The biggest recent bet in that strategy was Signature Systems. In 2024, Myers announced the Signature acquisition for total consideration of approximately $350 million, subject to customary adjustments. The deal was expected to close in the first quarter of 2024. Myers said it would be neutral to slightly dilutive to U.S. GAAP EPS in 2024, then turn meaningfully accretive—projecting $0.20–$0.30 of EPS accretion in 2025, $0.40–$0.50 in 2026, with additional accretion beyond 2026.

The integration thesis was simple: make one plus one equal more than two. Myers projected $8 million in annualized run-rate operational and cost synergies, fully captured by 2025. Financing would come from a new $350 million credit facility, with leverage expected to be around 3x at closing and paid down to under 2x within two years, supported by combined free cash flow.

CEO Mike McGaugh laid out why Signature fit: “Signature aligns extremely well with our targeted acquisition criteria: Signature has a leading market position, with branded and differentiated products, serving fast-growing end markets. Signature provides Myers an attractive complementary platform for long-term growth driven by world-wide investments in infrastructure over the next decade.”

Signature’s products are a different flavor of “material handling,” but they rhyme with the same theme: protection and reuse. The company manufactures and distributes composite matting used for industrial ground protection, stadium turf protection, and temporary event flooring. In plain terms, Signature builds engineered surfaces that keep equipment from sinking, protect high-value turf, and create safe, durable walkways and work zones—used across industrial sites and major venues around the world.

Signature CEO Jeff Condino framed the tailwind driving the business: “We look forward to joining the Myers Industries team and for Signature to represent an important and complementary addition to the combined Company. Signature's business continues to benefit from powerful tailwinds in infrastructure investments. Our highly engineered ground protection products are well positioned for continued growth due to the conversion from wood products to composite matting solutions.”

Myers said Signature would immediately strengthen profitability and cash flow and help push toward its Horizon 1 target of $1 billion in revenue at a 15% EBITDA margin.

The Distribution segment is the smaller sibling now—and much more tightly defined than the “everything distribution” Myers once ran. This segment distributes tools, equipment, and supplies for tire, wheel, and under-vehicle service across passenger vehicles, heavy trucks, and off-road vehicles. It also manufactures and sells tire repair materials, custom rubber products, and reflective highway marking tapes. The products go to retail and truck tire dealers, commercial fleets, auto dealers, general service and repair centers, tire retreaders, truck stops, and government agencies, under brands including Myers Tire Supply, Myers Tire Supply International, Tuffy Manufacturing, Mohawk Rubber Sales, Patch Rubber Company, Elrick, Fleetline, MTS, Seymoure, Advance Traffic Markings, and MXP.

But the company’s “power of subtraction” story isn’t over. In a significant development, the Board approved launching a strategic review of the Myers Tire Supply business—positioning it as another step toward simplifying the portfolio and narrowing focus around the mission of “protecting the world from the ground up.” Alongside that review, Myers also moved to consolidate rotational molding production capacity to better utilize its assets.

Chairman F. Jack Liebau Jr. made the board’s view explicit: “As a Board, we are confident in this management team and unanimously support the strategic review of Myers Tire Supply. If the review results in the divestiture of MTS, we believe Myers will be a simplified, more profitable company better able to create long-term shareholder value.”

The message to investors was clear: Myers was willing to divest an underperforming piece of distribution to concentrate on higher-margin Material Handling. The company pointed to Material Handling generating over $600 million in sales, with segment margins in the low 20s—supporting a steadier earnings profile.

By 2024, the financials started to reflect a company that had finally found its shape. For the full year, Myers reported net sales of $836.3 million, up from $813.1 million in 2023. Gross margin improved to 32.4%, up 50 basis points.

And leadership was again signaling execution mode. CEO Aaron Schapper said, “In closing 2024, we reported solid fourth quarter financial results with margin growth led by our Signature and Scepter brands, demonstrating the valuable assets we have within our portfolio. Building on these results, we are launching our 'Focused Transformation' program with a target to implement $20 million of annualized cost savings, primarily in SG&A, by year-end 2025.”

VIII. The Quiet Competitive Moats & Business Model Deep Dive

Material Handling looks simple from a distance. Plastic containers. Pallets. Bulk bins. Things you stack, move, and forget about.

But the business gets a lot more interesting when you look at how customers actually buy—and what happens after they do.

Start with automotive. When an OEM designs a new assembly line, the reusable containers that shuttle parts from suppliers to the plant floor aren’t picked out of a catalog at the last minute. They’re engineered for that exact job: built to protect a specific part, sized to fit a specific rack system, and often designed around a specific workflow. That’s the world Buckhorn plays in, with a wide lineup of reusable storage products including intermediate bulk containers, handheld containers, and pallets.

And that’s where the moat begins to show up.

Because once a customer builds a “container program,” they’re not just buying plastic. They’re investing in custom tooling, training the workforce around a standardized process, and integrating the packaging into logistics routines and, in many cases, software systems. At that point, switching suppliers isn’t a simple rebid. It’s a disruption risk. The procurement manager who signs off on the original program is not eager to roll the dice on a change that could slow a line—or stop it—to save a little on unit cost.

The other underappreciated advantage is technical craft.

Elkhart Plastics is a 32-year-old company that makes rotationally molded products in an almost endless variety of shapes, lengths, and thicknesses. It provides custom designs across industries like recreational vehicles, marine, agriculture, commercial construction equipment, heavy truck equipment, and material handling. It also manufactures TUFF Stack™ and TUFF Cube™ Intermediate Bulk Containers, Connect-A-Dock products, and products for KONG Coolers.

Rotational molding isn’t something you get good at by accident. The learning curve is steep: how polymers behave under heat, how wall thickness varies across complex shapes, how to design molds that produce consistent parts run after run. Myers believed the combination of Elkhart with its Ameri-Kart business would create the fifth-largest rotational molding business in the United States—and that scale matters. With more capability spread across more facilities, customers get practical value: backup capacity, more reliable supply, and the ability to serve regions without shipping everything across the country.

That manufacturing footprint also changes the relationship. Multiple plants create redundancy if one facility goes down. A regional presence can mean faster delivery and lower freight costs. And owning production—rather than outsourcing—lets Myers control quality in ways contract manufacturing often struggles to replicate.

Just as importantly, this is not a “lowest price wins” sales motion.

In Material Handling, deals are often won through engineering-led, consultative selling. Myers’ teams work with customers to design solutions that make a facility run smoother and safer, reduce damage, and eliminate small sources of friction that quietly cost money every day.

Signature Systems is a good example of that solution-driven model. Signature manufactures and distributes composite matting for industrial ground protection, stadium turf protection, and temporary event flooring. It designs, engineers, and manufactures composite matting systems used globally, offering application-based solutions and customer-informed engineering across industries—from industrial sites to the world’s highest-profile venues and events.

If a utility needs to move heavy equipment across protected wetlands, or a stadium needs to host an event without destroying expensive turf, the value isn’t “a bunch of panels.” It’s avoiding damage, downtime, and regulatory headaches. And Signature has been positioned for continued growth as customers convert from wood products to composite matting solutions.

This is the unsexy excellence at the heart of Myers’ business model. The critical relationships aren’t with CEOs making grand pronouncements. They’re with procurement managers and operations leaders trying to keep things moving. You earn those relationships the slow way: consistent delivery, responsive service, and showing up with real technical answers when something breaks or needs to change.

Finally, there’s capital allocation—another quiet edge.

Myers moved away from empire-building and toward acquisitions meant to deepen capabilities inside defined segments. As of December 31, 2024, the company had $32.2 million of cash on hand and $383.6 million of total debt. Debt reduction remained a priority, and Myers said it reduced total debt by $26 million since March 31, 2024—the quarter Signature Systems was acquired.

And it’s still a company that signals stability the old-fashioned way: it has maintained dividend payments for 53 consecutive years.

IX. Strategic Analysis: Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers

To understand Myers’ competitive position, it helps to step back from products and segments and look at the forces shaping the game. Two frameworks are useful here: Porter’s Five Forces, which explains the structure of competition, and Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers, which explains why certain advantages actually persist.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Low-Medium

On paper, it doesn’t look that hard to start a plastics operation. The upfront capital isn’t like building a semiconductor fab.

But the real barriers aren’t on the factory floor—they’re inside the customer. In material handling, relationships and qualification matter. Automotive OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers don’t just place an order and hope for the best. They qualify suppliers, demand certifications, and expect proven performance. And even when a new entrant can make a part, matching the accumulated know-how in rotational molding and blow molding—the muscle memory of how to make consistent product at scale—takes time.

Supplier Power: Medium

Myers’ biggest input is polyethylene resin, and resin pricing follows energy markets. The company can often pass through higher costs, but usually with a delay. In volatile periods, that lag can compress margins.

And there’s no easy escape hatch. Vertical integration into resin production isn’t realistic at Myers’ scale; petrochemical manufacturing is a different universe of scale and economics.

Buyer Power: Medium-High

Myers sells to some very large, very sophisticated buyers—especially in automotive. Those customers can negotiate hard.

But buyer power is not the same thing as buyer freedom. When a reusable container program is designed into a plant’s workflow, switching suppliers can mean redesign, requalification, and operational risk. Customization and embedded processes blunt pure price leverage, even when the customer is big.

Threat of Substitutes: Low

There are substitutes—wood pallets, corrugated packaging—but they break down quickly once you move past the simplest use cases.

Wood is heavier, less consistent, and harder to sanitize. Corrugated can work for one-way shipping, but it doesn’t hold up in closed-loop, reuse-heavy systems. And as companies push harder to eliminate single-use packaging, the “substitute” trend often runs in Myers’ favor: the sustainability narrative reinforces reusable systems rather than displacing them.

Competitive Rivalry: Medium

Reusable packaging is competitive, but not dominated by a single giant. The industry includes many regional players and several larger competitors, including Orbis (owned by Menasha) and Schoeller Allibert.

That fragmentation matters. It means customers have options, and pricing discipline matters. But it also means the market is broad enough for specialization to work. Myers’ North American manufacturing footprint and focus on particular end markets lets it compete on more than unit price alone.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Moderate

Scale helps in manufacturing: spreading fixed costs, buying materials more efficiently, and keeping plants utilized. The Elkhart acquisition was explicitly about building that kind of scale—together with Ameri-Kart, Myers said it created the fifth-largest rotational molder in the United States.

Still, this isn’t winner-take-all. Regional competitors can be plenty viable, especially when freight costs and local service matter.

Network Economics: Limited

This isn’t a network business. One customer adopting Myers containers doesn’t inherently make Myers more valuable to the next customer in the way that payments networks or software ecosystems do.

Counter-Positioning: Yes

Myers’ emphasis on reusable packaging is a form of counter-positioning. Companies tied to disposable packaging face a real dilemma: pushing reuse can cannibalize their existing economics. Myers built its capabilities around reuse, without having to protect a legacy disposable base in the same way.

Switching Costs: Strong

This is the clearest and most durable advantage in the portfolio. Custom tooling, program specifications, logistics integration, and shop-floor training create real friction. Once a customer standardizes on a container system, the incumbent supplier gets an edge that’s hard to dislodge without a compelling reason.

Branding: Weak

This is an industrial, relationship-driven business. Brand matters at the level of trust with procurement and operations teams, but it’s not consumer-style branding power. Names like Buckhorn and Akro-Mils have credibility in the channel, yet the purchase decision is still anchored in performance, reliability, and service.

Cornered Resource: Moderate

Myers has valuable resources—manufacturing expertise, established customer relationships, and application engineering talent. But none of it is exclusive in a permanent way. A determined competitor can build similar capabilities over time with investment and patience.

Process Power: Growing

The company’s push toward operational excellence—often described in its own communications as the Myers Business System—points to process power. Continuous improvement in procurement, manufacturing execution, and customer service can compound quietly. It’s not flashy, but it becomes hard to match if you’re not running the same playbook with the same discipline.

Conclusion: Myers’ advantage isn’t one towering moat. It’s a set of practical, reinforcing edges—especially switching costs, growing process power, and real counter-positioning around reuse. That’s typical of strong industrial businesses: durable advantages that look modest on a slide, but matter a lot in day-to-day competition.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Key Risks

The Bull Case

If you buy the Myers story, the big bet is that the transformation is no longer a promise—it’s the base case. After years of portfolio pruning and operational cleanup, this is now the “good” company that was hiding inside the conglomerate.

Management framed the Signature deal as a line in the sand: a catalyst that moved Myers into Horizon Two of its Three Horizon strategy. They said they expected to disclose full-year 2023 pro-forma financial results for the combined company in the first quarter of 2024, and to lay out the long-term repositioning at a March 2024 Investor Day in New York City.

From there, the bull case is straightforward: margins still have runway. Operational improvements can keep compounding, and Signature was positioned as an immediate upgrade to profitability and cash flow. As the company put it, “The addition of Signature Systems immediately strengthens our profitability and cash flow profile and will support Myers in achieving our Horizon 1 goals of one billion dollars in revenue at a 15% EBITDA margin.”

The tailwinds are real, too. Sustainability pressure is pushing corporations away from single-use packaging, and regulators are increasingly nudging or mandating reusable alternatives in certain applications. Meanwhile, e-commerce keeps building warehouses and distribution centers, which tend to be steady consumers of pallets, containers, and the other “invisible infrastructure” Myers sells.

There’s also a classic small-cap setup here. Myers gets limited analyst attention, and the market often assigns a discount to companies that feel complicated or underfollowed. If the transformation becomes easier to understand—and the earnings profile becomes steadier—multiple expansion can amplify whatever operational gains the company delivers.

And finally: this is the kind of business private equity likes. Industrial platforms with recurring replacement demand and strong cash flow are natural roll-up targets. Myers could attract interest from financial sponsors or strategics that want scale in material handling.

A key part of the bull argument is credibility. Management has already shown it can do the hard things: divesting Lawn & Garden, exiting Brazil, and then following that with disciplined capability-building acquisitions like Elkhart and Signature.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with a reminder: this is still an industrial company. Myers remains exposed to cyclical end markets, especially automotive and broader industrial demand. In a recession, volumes can fall quickly, and pricing power tends to weaken at exactly the wrong time. The company also acknowledged that some end markets were still in near-term trough or trough-like conditions—something that showed up in first quarter results, with weak demand in its Automotive Aftermarket and Vehicle (RV and Marine) end markets.

Scale is another constraint. Myers competes in markets where larger players can invest more aggressively in capacity, technology, and customer relationships. Being smaller can mean fewer shots on goal for the biggest programs, and less room for error when demand softens.

Input costs are a chronic risk. Polyethylene resin volatility can squeeze margins, and even when Myers can pass those costs through, it often happens with a lag. That creates earnings variability the market tends to punish.

There’s also a geographic limitation: Myers is still mostly North America. That reduces exposure to faster-growing international markets and concentrates economic risk in one region.

Acquisitions, while core to the strategy, can cut both ways. In the third quarter of 2024, Myers’ GAAP results included a $22.0 million non-cash goodwill impairment charge in the Material Handling segment—an acknowledgment that at least some acquired value didn’t materialize as expected.

And the Distribution segment remains a drag. The company cited lower volume and pricing as the primary drivers of weaker performance. While SG&A fell year-over-year, largely due to lower incentive costs, margins compressed sharply: operating income margin fell to 1.6% versus 4.3% in 2023, and adjusted EBITDA margin declined to 3.7% from 6.2%.

Key Risks to Monitor

Automotive production volumes: The EV transition adds uncertainty. Will EV manufacturers adopt similar reusable container programs? Will the transition disrupt existing relationships and volumes?

Resin spread: Profitability depends on the gap between polyethylene costs and product pricing. Watch resin trends and how quickly Myers can pass increases through.

Customer concentration: A single customer above 10% of revenue can create real leverage over pricing and terms. Check annual filings for concentration disclosures.

Acquisition integration: Signature is still being integrated. Track whether synergies show up as expected and whether any operational friction emerges.

Economic indicators: PMI, industrial production, and automotive build rates are useful leading indicators for demand across Myers’ end markets.

XI. Lessons & Takeaways: The Playbook

The Myers Industries story offers lessons that travel well beyond one small-cap industrial.

The power of subtraction. Sometimes the highest-leverage strategic move is deciding what to stop doing. Myers spent decades adding businesses and complexity, then discovered that simplifying the portfolio unlocked more value than another acquisition ever could. Selling Lawn & Garden, exiting Brazil, and even putting Myers Tire Supply under strategic review all point to the same idea: focus isn’t what you say you care about—it’s what you’re willing to walk away from.

Industrial value creation is slow and boring. There’s no overnight “pivot” in manufacturing. Improvement shows up the hard way: tighter procurement, cleaner plant footprints, better pricing discipline, fewer SKUs that don’t earn their keep. It’s years of compounding execution to turn a mediocre margin profile into a competitive one. Investors looking for instant gratification tend to miss it.

Focus beats diversification. The conglomerate discount is real because complexity hides the truth. Focused companies are easier to understand, easier to manage, and harder to screw up. Myers’ evolution—from a multi-segment sprawl to two core segments, and potentially fewer—demonstrates why markets tend to reward clarity and punish “a little bit of everything.”

Legacy business nostalgia is expensive. The tire supply business wasn’t just a segment; it was the origin story. That kind of legacy creates emotional gravity inside organizations. But businesses aren’t museums. If a legacy operation is low-return, capital-hungry, or strategically distracting, protecting it for sentimental reasons can quietly tax everything else.

Activist pressure can be constructive. External pressure isn’t always pleasant, but it can accelerate decisions that boards and management teams might otherwise postpone. At Myers, that pressure helped force the portfolio conversation into the open—and pushed the company toward actions that ultimately made it simpler and more valuable.

Small-cap industrials can compound quietly. These companies don’t dominate headlines. They don’t get breathless product launches. But if you can identify a durable niche, real switching costs, and a management team that executes, the compounding can be very real—even while most of the market isn’t watching.

Management matters in turnarounds. The leadership shift toward operational excellence—more Danaher and less “industrial conglomerate inertia”—changed the pace and quality of execution. Strategy is necessary, but in turnarounds, operators decide whether the plan becomes results.

Market inefficiency in boring companies. It took years for Myers’ operational progress to show up in how investors valued the business. That gap between reality and perception is the opportunity—if you’re willing to do the work and wait.

Sustainability as business driver, not just marketing. Reusable packaging wins because it often makes financial sense: lower total cost of ownership, less waste, more consistent performance, and better standardization. The sustainability narrative helps, but the economics are what keep customers buying.

Key Performance Indicators to Track

For investors following Myers Industries, these are the critical metrics to monitor:

1. Material Handling Segment Adjusted EBITDA Margin: This is the most important indicator of whether the core business is getting stronger. Myers has targeted a 15% EBITDA margin company-wide; watching Material Handling’s margin trajectory tells you whether operational improvements and mix are moving in the right direction.

2. Organic Revenue Growth vs. End Market Conditions: Separate what Myers is winning organically from what it’s buying through acquisitions. The most useful test is relative performance: how does Myers grow versus industrial production and automotive build rates?

3. Free Cash Flow Conversion: Myers’ strategy depends on turning earnings into cash. Track how much EBITDA becomes free cash flow, because that’s where working capital discipline, capital spending choices, and integration costs show up—cleanly and unforgivingly.

XII. Epilogue: What's Next for Myers?

As 2025 wound down, Myers Industries found itself at another familiar place in its history: the edge of a new decision, with the old identity in the rearview mirror and the new one still being sharpened.

The company was actively executing what it called its Focused Transformation initiative—a program meant to do in operations what the past decade of divestitures did in the portfolio. The message was straightforward: concentrate resources on what Myers does best, improve profitability across the remaining businesses, build a culture of performance, and allocate capital with more discipline than the old conglomerate-era playbook ever required.

The biggest unresolved question was also the most symbolic one. The strategic review of Myers Tire Supply could become the final major move in the company’s long portfolio reset. The logic is hard to argue with: Material Handling has become the profit engine, while parts of distribution have lagged. Myers has pointed to Material Handling generating more than $600 million in sales, with segment margins in the low 20s—exactly the kind of steadier earnings profile investors tend to reward. And if a divestiture happens, the company has indicated leverage is expected to move down toward roughly 2x afterward.

But the emotional weight is real. If Myers ultimately separates from Myers Tire Supply, the founder’s original tire business—the reason the company is called “Myers” in the first place—would no longer be part of the enterprise. That would mark the end of a nearly century-long arc: from tire repair supplies in Akron to a company centered on engineered, reusable infrastructure for supply chains.

Looking forward, a few big questions define what “the next Myers” could look like.

First: the EV transition. Automotive has been a major end market for reusable packaging, and the industry is being rebuilt in real time. The question isn’t whether EV makers need logistics—they do—but whether shifts in platforms, suppliers, and production footprints change who wins the container programs. Early signs are encouraging, since EV manufacturers face the same fundamental challenge: moving parts safely, efficiently, and repeatedly. Still, transitions create openings, and openings create risk.

Second: automation and smart packaging. The next layer of value may come from making “dumb” containers a little less dumb—IoT-enabled tracking, better traceability, real-time visibility into where assets are and how they’re used. If reusable packaging becomes connected infrastructure, the supplier relationship can deepen from “we sell you plastic” to “we help you run your system.”

Third: geography. Myers remains primarily a North American business. Europe and Asia are largely untapped, which can be read two ways: as runway for expansion, or as a signal that global competitors may have advantages Myers would need to earn the hard way.

And then there’s the ever-present question for companies like this: does it stay independent? Private equity interest in industrial platforms remains strong, especially for businesses with stable cash flow and a clear operational improvement path. A company that has already done much of the painful simplification work can be a particularly attractive target.

Finally, leadership. Aaron M. Schapper became President and CEO in January 2025, following Mike McGaugh’s departure. CEO transitions are always consequential, but especially so in the middle of a multi-year transformation—when the strategy is set, the to-do list is long, and execution is the whole game. Schapper signaled both optimism and unfinished work early in his tenure: “During my first two months with Myers, I have met with many members of our organization and have been impressed with and encouraged by their dedication and desire to drive improvement. There are tremendous opportunities here and I am confident that we will build a brighter future working together. To begin this journey, we are launching a process to refine our strategy to create value and deliver results.”

Why does this story matter beyond Myers? Because it’s a template hiding in plain sight. A lot of industrial companies live for years in the uncomfortable middle: too many businesses, too little clarity, and not enough returns to justify the complexity. Myers shows a path out. The operational excellence playbook isn’t mysterious. What’s rare is the willingness to shed legacy businesses, accept a smaller revenue number, and do the unglamorous work of becoming better—rather than merely bigger.

The takeaway isn’t that every company should copy Myers point for point. It’s that transformation is possible when leadership stops negotiating with reality, makes the difficult choices, and then executes long enough for the results to compound.

From two brothers with $620 and a used truck to an $800-million-plus focused industrial company, Myers’ story spans nearly a century of American manufacturing. It began by helping people stretch the life of a tire in the Great Depression. Today, it helps companies protect and move products through modern supply chains. The founders might be surprised by what their business became. But they’d probably recognize the throughline: practical problem-solving, built for the real world.

Sometimes the best growth strategy is becoming excellent at fewer things. Myers learned that the hard way—through decades of complexity and a long, deliberate simplification. For anyone willing to look past the lack of glamour in industrial businesses, it’s a lesson worth keeping.

XIII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Resources for Deeper Understanding:

-

Myers Industries annual reports (2015-present) — The clearest way to watch the strategy evolve in real time, especially as segment reporting shifts and management explains what it’s exiting, what it’s doubling down on, and why.

-

"The Outsiders" by William Thorndike — A great lens on capital allocation, and a helpful way to frame Myers’ move away from “bigger at any cost” toward returns, cash flow, and focus.

-

"Good to Great" by Jim Collins — The Hedgehog Concept maps well to Myers’ journey: stop trying to be broadly diversified, and commit to the intersection of what you can do best and what actually creates value.

-

Industry reports from Freedonia Group on reusable packaging markets — Useful for understanding the underlying demand drivers in reusable packaging: where growth is coming from, how customers think about total cost of ownership, and what the competitive landscape looks like.

-

"Competition Demystified" by Bruce Greenwald and Judd Kahn — A practical framework for businesses like Myers, where advantage often comes from switching costs, process discipline, and customer embeddedness—not flashy branding.

-

SEC filings (10-Ks, proxy statements 2010-present) — If you want the quantitative story, this is where it lives. Segment disclosures, restructuring actions, acquisitions, and impairments show up here first—and with the least spin.

-

Industrial packaging trade publications (Modern Materials Handling, Plastics News) — Good for industry context: new product trends, customer requirements, and how competitors position themselves.

-

Automotive logistics industry analysis — Helpful background on why “just a container” becomes mission-critical in automotive, and how packaging decisions tie into assembly-line efficiency and supplier networks.

-

Private equity portfolio company case studies — Myers’ transformation has a lot in common with the PE playbook: simplify the portfolio, improve operations, and allocate capital ruthlessly.

-

"Where the Money Is" by Adam Seessel — A strong guide to small-cap value investing—and why underfollowed, unglamorous industrials can be mispriced for long stretches.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music