MaxLinear Inc.: From Cable Modems to the Edge of Everything

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: you’re streaming a 4K movie while your teenager games online. Your smart home cameras are uploading footage, your doorbell catches a delivery, and somehow your Wi‑Fi doesn’t collapse into chaos. In the background, a router hums away in a closet. And deep inside that box sits a tiny slice of silicon doing the heavy lifting.

The company behind that chip is probably not one you’ve ever heard of.

MaxLinear, Inc. is a U.S. semiconductor company that designs highly integrated RF, analog, and mixed-signal chips for broadband and connectivity. It’s based in Carlsbad, California, and it’s fabless, meaning it doesn’t own factories. Instead, it lives and dies by design: turning tricky real-world signals—coax, fiber, radio waves—into fast, reliable data.

But MaxLinear’s story isn’t just a tour of networking hardware. It’s a study in how you survive in semiconductors when you’re not a giant. It’s about platform risk—what happens when your core market stops growing. It’s about M&A as both a lifeline and a landmine. And it’s about the constant stress of competing in categories where companies like Broadcom, Qualcomm, and Marvell can outspend you, out-scale you, and outlast you.

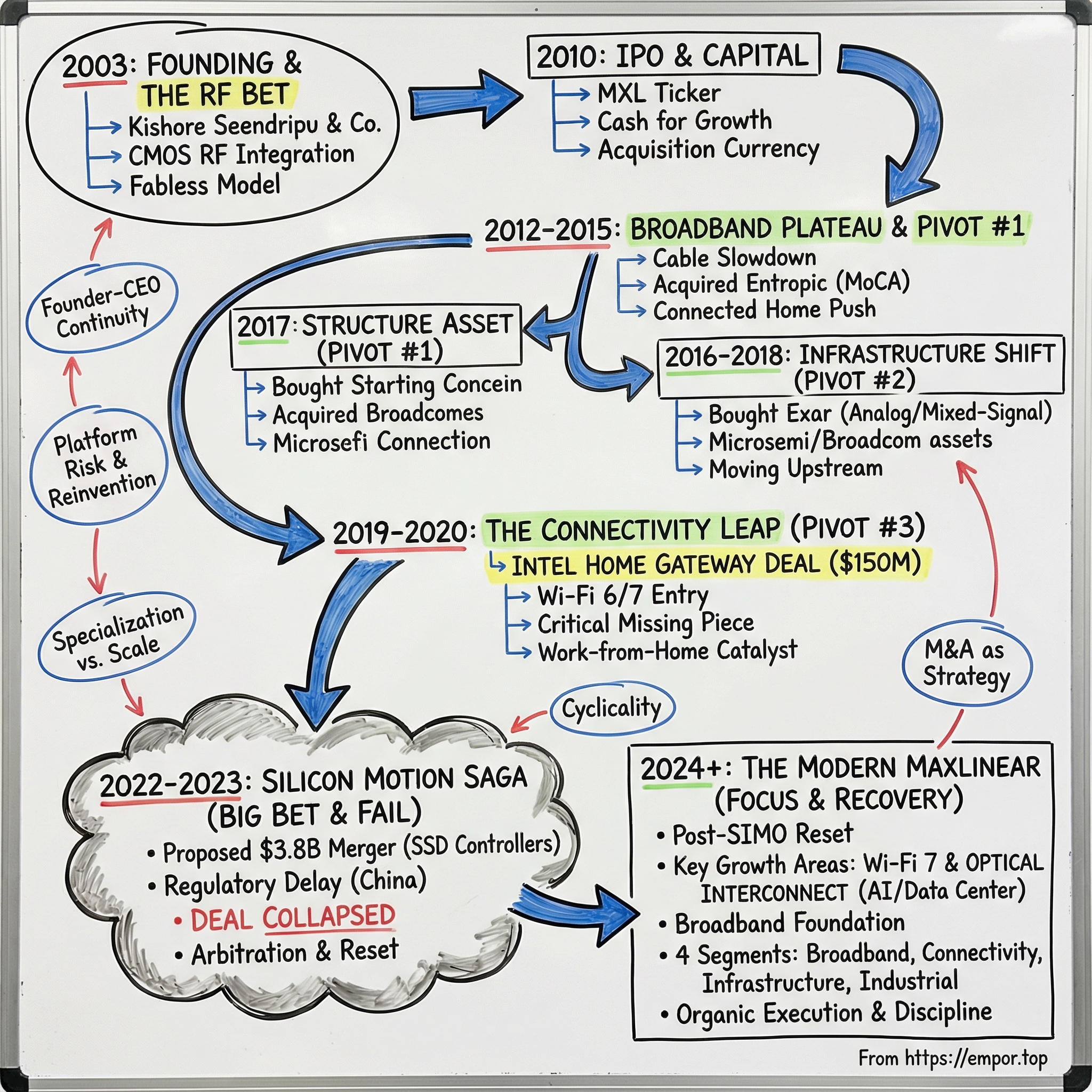

MaxLinear was founded in 2003 in Carlsbad by eight semiconductor industry veterans, and from day one it was led by Kishore Seendripu, who went on to serve as chairman, president, and CEO. Over the next two decades, the company would ride the cable boom, watch parts of that world flatten out, then repeatedly reinvent itself—moving from consumer-facing silicon into the infrastructure that powers the internet itself.

So here’s the question that frames everything: how does a fabless chipmaker born in the cable era navigate multiple platform shifts and survive the semiconductor bloodbath?

The answer takes us through strategic pivots into broadband infrastructure and optical interconnects, a $150 million acquisition of Intel’s home gateway division in the middle of a global pandemic, and then an audacious $3.8 billion attempt to buy a company more than twice its size—an attempt that ultimately collapsed.

Along the way, we’ll keep coming back to a few big themes: specialization versus diversification, what founder-CEO longevity looks like in a brutally cyclical industry, and whether a mid-scale semiconductor company can carve out something sustainable when the economics increasingly favor scale.

MaxLinear matters because it’s an archetype: the specialized mid-cap chip company trying to build a defensible position while the ground keeps shifting under its feet. If you want to understand how the semiconductor industry punishes complacency—and rewards the rare team that can pivot before it’s too late—this is a great place to start.

II. Founding Context & the Broadband Gold Rush (2003–2006)

The early 2000s were a weirdly perfect moment to start a communications chip company. Broadband was flipping from “nice to have” to “can’t live without,” and a real fight broke out over the last mile—the final connection between the internet backbone and your living room. Cable companies pushed data over coax. Telcos fought back with DSL over phone lines. Whoever delivered the best experience would win the home, and eventually hundreds of millions of households worldwide.

Kishore Seendripu saw that shift coming early. He had a PhD in electrical engineering from UC Berkeley, additional credentials from Wharton, and the kind of résumé you see when someone has been in the RF trenches for a while. From 1996 to 2002 he held engineering and management roles at Rockwell Semiconductor Systems, Broadcom, and Silicon Wave, working on radio-frequency systems-on-chip for wireless and broadband products.

In September 2003, Seendripu and a small group of fellow engineers formed MaxLinear in Carlsbad, California (incorporated in Delaware). There were eight founders in total—people with different backgrounds, but a shared instinct that the next wave of connectivity would need better, cheaper, more integrated silicon. Seendripu became the first CEO. Curtis Ling came in as co-founder and chief technical officer.

The pairing mattered. Ling brought deep technical credibility: he’d been a Member of Technical Staff at Silicon Wave and had also been an assistant professor at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Seendripu brought the operator’s perspective—how to turn hard RF problems into products, customers, and a business. Together they aimed at a problem the industry had been wrestling with for years.

The goal was simple to describe and brutally hard to execute: put high-performance radio systems onto a single chip using standard CMOS. That meant integrating RF circuits, mixed-signal components, and digital signal processing onto one piece of silicon.

This was a big deal because, at the time, high-performance RF often lived on more expensive process technologies like gallium arsenide (GaAs) or specialized silicon germanium (SiGe). If MaxLinear could make RF behave on standard CMOS—the workhorse process behind mass-market digital chips—it could tap into the cost curve and manufacturing scale that the GaAs world couldn’t touch. Even the name was a mission statement: “Maximum” data rates with “Linear” analog performance.

MaxLinear also made a second bet alongside the technology one: it would be fabless. No factories, no massive fixed costs—just design. The company could lean on contract manufacturing partners like UMC and TSMC and keep its energy focused on what it thought was the real differentiator: engineering talent and integration.

Early on, that bet looked smart. One of MaxLinear’s first products, introduced in 2003, was the MxL5003, which the company described as the world’s first single-chip CMOS digital terrestrial TV tuner. It helped enable smaller, cheaper TV reception modules for devices like set-top boxes—exactly the kind of “take a bulky multi-chip solution and collapse it into one” move that becomes a calling card in this industry.

By the time MaxLinear went public, its venture backers included Mission Ventures, U.S. Venture Partners, Battery Ventures, and UMC Capital. It raised around $35 million in venture funding before the IPO—and had only spent about half. Building a company to public-company readiness with roughly $17 million in burn isn’t normal in semiconductors. That was the fabless model working the way it’s supposed to: capital-light, fast, and disciplined.

MaxLinear’s founding team also came from the Southern California semiconductor corridor—alumni of places like Conexant, Broadcom, and Silicon Wave. This wasn’t a “move fast and break things” startup. It was an engineering shop, built around the idea that if you could reliably pull clean signal out of noisy reality—coax, antennas, and air—you could earn your seat at the table.

But there was an early reminder of how unforgiving platform bets can be. Prior to 2009, most of MaxLinear’s revenue came from “mobile handset digital television receivers” using its digital TV RF chips, primarily sold in Japan. Key customers included Panasonic, Murata, and MTC Co. Mobile TV was real revenue and real demand—until the world moved on and smartphones changed how people consumed video. The lesson was already there in the company’s early chapters: great silicon can still be at the mercy of where the market decides to go.

That founding DNA—deep RF expertise, capital-efficient execution, and exposure to fast-shifting consumer platforms—set the pattern MaxLinear would spend the next two decades trying to master. The question wasn’t whether the team could build great chips. It was whether they could keep picking the right battlegrounds as the ground kept moving.

III. Building the Moat: Cable & Satellite Supremacy (2007–2011)

By 2009, MaxLinear’s business had quietly but decisively changed shape. The company was no longer defined by Japanese mobile TV receivers. Instead, it was selling chips into digital set-top boxes in Europe, plus a mix of digital TVs and automotive navigation displays. It was a platform shift—not the last one—and it showed something important early: MaxLinear could move when demand moved.

The scale was real. In 2009, MaxLinear shipped 75 million chips to customers like Panasonic and Sony, with 99 percent of its sales coming from Asia. Shipping that kind of volume meant the company’s “integration-first” pitch wasn’t just a lab success. It was working in mass production, where cost, yield, and reliability decide who gets to stay designed in.

And the advantage wasn’t abstract. Operators and equipment makers liked MaxLinear’s chips for the unglamorous reasons that matter: better power efficiency, smaller footprints, and higher levels of integration that simplified designs and lowered the bill of materials. In the set-top box world, those savings stacked up fast—less heat to dissipate, fewer components to source, and more flexibility in industrial design.

Financially, the business looked unusually crisp for a young semiconductor company. By the end of 2009, MaxLinear had $17.9 million in cash. It generated $51.4 million in revenue and $4.3 million in profit. Being profitable before going public isn’t the typical “growth-at-all-costs” tech story—it’s what happens when you win real design slots with tier-1 OEMs and ship at scale.

In November 2009, MaxLinear announced its intention to go public.

The company priced its IPO on March 24, 2010 on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker MXL. It initially expected to raise around $43 million, then lifted the projection to roughly $90 million after increasing the share price late in the process. The market rewarded the story: shares jumped 34 percent on their debut. MaxLinear raised about $92 million, opening at $14 and touching $18.70 on the first day.

By May 2010, MaxLinear employed 135 people. Read that again: about $51 million in revenue, profitability, and 135 employees—classic fabless leverage. And the company was explicit about what the new capital was for. The proceeds would go toward “general corporate purposes,” and potentially acquisitions of competitor businesses or products.

That line was the tell. The post-IPO MaxLinear wouldn’t just be a company that shipped great tuners and connectivity chips. It would increasingly become a company that bought capability—using public-market currency and, later, debt capacity to expand beyond its original core.

It also had to. The competitive environment was unforgiving. Broadcom towered over the category with massive R&D budgets, platform-level integration, and the ability to price aggressively. Smaller specialists like Entropic and Sigma Designs fought for niches, often under constant pressure—on margins, on design wins, and on whether they’d get acquired or squeezed out.

So MaxLinear’s existential question sharpened: was it a cable-centric business that would live and die with set-top box volumes, or a semiconductor company with transferable mixed-signal expertise that could keep climbing the connectivity stack?

By 2011, MaxLinear had reached roughly a $100 million annual revenue run rate with strong profitability. But the threat was already visible on the horizon. Cord-cutting was shifting from a speculative fear to an emerging reality, and the operators at the center of MaxLinear’s ecosystem were starting to see subscriber growth slow.

The implication wasn’t subtle. If your core platform is peaking, you either find new platforms—or you spend the next decade shrinking. MaxLinear’s next chapter would be defined by how it responded.

IV. The Broadband Plateau & Diversification Imperative (2012–2015)

The years after the IPO forced MaxLinear to face the reality it had been trying not to stare at too hard: the set-top box engine wasn’t dead, but it wasn’t going to keep compounding forever. Shipments were still healthy, yet growth was slowing as developed markets saturated. And at the exact same moment, Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon Prime Video were training consumers to think of TV as an app, not a subscription.

When your core platform starts flattening, semiconductors has a well-worn playbook: consolidate, broaden the product map, and buy time to find the next wave. For MaxLinear, that logic pointed to a familiar neighbor.

That neighbor was Entropic Communications, another San Diego-area fabless chip company with technology that fit neatly next to MaxLinear’s: MoCA, the Multimedia over Coax Alliance standard for home networking.

Entropic had been founded in 2001 and built its reputation around the idea that coax shouldn’t just carry TV into the home—it should also move data around it. MoCA did exactly that, pushing high-speed connectivity over the same coax already in the walls. Entropic also developed related connected-home silicon, including technology used in satellite outdoor units and set-top box systems-on-chip.

Entropic went public in December 2007 on NASDAQ under the ticker ENTR. But by the mid-2010s, it wasn’t a growth story anymore. After showing up on Deloitte’s fast-growing list in 2011 and pursuing acquisitions earlier in the decade, Entropic’s results deteriorated. Revenue fell, losses piled up, offices were closed, and the company ultimately replaced its CEO. In September, Entropic hired Barclays to explore “strategic alternatives,” and two months later longtime chief executive Patrick Henry departed. The subtext was clear: Entropic was for sale.

MaxLinear announced the acquisition, and on February 3, 2015 it closed the deal for total consideration of about $287 million. The structure told you where the leverage was. Entropic shareholders received $1.20 per share in cash plus 0.2200 of a share of MaxLinear stock for each Entropic share. MaxLinear put up roughly $111 million in cash and issued about 20.4 million shares. After the merger, existing MaxLinear shareholders owned about 65% of the combined company, and former Entropic shareholders held about 35%.

In other words: this wasn’t MaxLinear paying a premium for a rocket ship. This was a strategic, price-conscious purchase of a distressed peer—one part capability grab, one part consolidation.

On paper, the pitch was clean. MoCA was a way to monetize the installed base of coax, a theme MaxLinear already understood deeply. Add Entropic’s engineering talent and a portfolio of roughly 1,500 issued and pending patents, and you could tell a story about a bigger, broader “connected home” platform. MaxLinear also pointed to about $20 million in expected annual savings, driven by supplier leverage and eliminating duplicate roles. Entropic had around 280 employees worldwide; MaxLinear had about 370.

The bull case was straightforward: consolidation plus cost synergies, with the bonus of cross-selling each company’s products into the other’s customer relationships.

The bear case was equally straightforward, and it turned out to be hard to dismiss: integration is messy, customer overlap is often higher than you think, and buying more share of a slow market doesn’t magically turn it into a fast one.

After Entropic, MaxLinear was roughly a $200 million revenue company—but with margins under pressure. Integration costs hit, competitive pricing tightened, and Broadcom’s highly integrated platforms kept winning the biggest, highest-volume sockets where scale mattered most and specialization mattered less.

The most consequential thing in this entire period might have been what didn’t change. Kishore Seendripu stayed in the CEO seat, steering through the acquisition and the operational churn that followed. In semiconductors, that kind of continuity through M&A is rare. Whether it was steady-handed vision or a lack of strategic reset would become one of the recurring debates around MaxLinear in the years ahead.

By the middle of the decade, the picture was sobering: around $200–$250 million in revenue, margins compressing, and a company that had strengthened its position—inside a market that no longer looked like it had much runway. MaxLinear didn’t just need another cost synergy. It needed a new growth engine.

V. Inflection Point #1: The Infrastructure Pivot (2016–2018)

By 2016, MaxLinear had internalized a deceptively simple truth: the money wasn’t just in the devices at the edge of the network. It was in the network itself.

Cable operators weren’t merely refreshing set-top boxes anymore. They were rebuilding their systems to survive the internet era—because the business had flipped from “deliver TV” to “deliver bandwidth.” And that shift demanded new generations of gear in the home and, just as importantly, deep inside operator networks. That gear needed sophisticated mixed-signal silicon—the kind MaxLinear knew how to build.

DOCSIS 3.1 became the forcing function. The standard promised multi-gigabit cable broadband that could hold its own against fiber-to-the-home. With threats coming from Google Fiber, Verizon FiOS, and even municipal broadband efforts, operators had strong incentives to upgrade. That meant a sweeping replacement cycle for cable modems and gateway equipment—rolling through tens of millions of households.

MaxLinear’s response was to start buying the building blocks it needed to follow the spend upstream.

In April 2016, it acquired Microsemi’s wireless backhaul business, adding about 30 employees. A month later, MaxLinear announced another backhaul deal—this time acquiring Broadcom’s wireless backhaul infrastructure business for $80 million in cash and bringing on about 120 more people.

That Broadcom transaction was a tell. Broadcom was the apex predator in connectivity silicon, and MaxLinear was now picking up assets Broadcom didn’t want to prioritize—turning itself into a disciplined scavenger with a strategic plan.

On February 8, 2017, MaxLinear added another piece: it acquired Marvell Technology Group’s G.hn business for $21.0 million in cash. G.hn enabled networking over power lines, phone lines, and coaxial cables—yet another way to move data around homes and buildings using whatever wiring already existed.

But the defining move in this era wasn’t a bolt-on. It was a step into an adjacent identity.

MaxLinear went after Exar Corporation, announcing a definitive agreement to acquire Exar for $13.00 per share in cash, a 22% premium to Exar’s closing price of $10.62 on March 28. The deal valued Exar at about $700 million, or approximately $472 million net of Exar’s cash. MaxLinear paid roughly $687 million in cash to close it.

Strategically, Exar was a departure. Exar’s power management and interface products weren’t RF tuner chips. They were the “picks and shovels” components that show up everywhere—wireless and wireline communications infrastructure, broadband access equipment, industrial systems, enterprise networking, and even automotive platforms. In other words: less dependent on any single consumer cycle, and far more reusable across customers and markets.

MaxLinear said the deal advanced its goals of increasing scale, diversifying revenue by end customers and addressable markets, and expanding its analog and mixed-signal footprint on tier-1 platforms. Exar brought a broader catalog of high-performance analog and mixed-signal products, plus a team that could help MaxLinear sell into new sockets.

“We are pleased to complete the acquisition of Exar,” said Dr. Kishore Seendripu, CEO of MaxLinear. “Exar’s talented team and expertise in power management and interface technologies will enable us to more effectively serve our customers and furthers our goal of increased scale and diversification.”

As these pieces came together, the mix began to change in a way that mattered. Infrastructure—silicon destined for operator equipment, fiber network terminals, and backhaul—grew from a smaller part of the business into the center of gravity. Consumer exposure shrank. By 2018, MaxLinear had worked its way out of the mental box of “set-top chip company” and into a new role: broadband infrastructure enabler.

The numbers reflected that stabilization. Revenue settled into the $250–$300 million range, gross margins improved on better mix and scale, and the company showed that infrastructure demand could be less whiplash-prone than consumer electronics.

But even with the pivot working, there was still a glaring gap in the story. The connected home was increasingly defined by Wi‑Fi—and MaxLinear didn’t yet have a compelling Wi‑Fi platform. Infrastructure had given the company a steadier foundation. The next inflection point would be about adding the missing layer that sat on top of it.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The Intel Acquisition & Connectivity Leap (2019–2020)

April 2020 was not an obvious moment to go shopping. COVID-19 was freezing economies, supply chains were jolting from one disruption to the next, and nobody knew whether demand for electronics was about to collapse—or surge. In the middle of that fog, MaxLinear made one of the most consequential moves in its history.

It announced an all-cash, $150 million asset deal to acquire Intel’s Home Gateway Platform Division.

Strip away the press-release language and the point was simple: MaxLinear was buying a ready-made connectivity stack. Intel’s unit included Wi‑Fi access point technology, Ethernet products, and home gateway system-on-chip platforms used by both broadband operators and retail networking brands. For MaxLinear, it wasn’t just “another product line.” It was the missing layer that sat on top of its broadband access silicon.

The reason Intel was willing to part with it was also straightforward. Intel had been retreating from parts of the connectivity edge, especially after its smartphone modem effort sputtered and the company refocused on its core priorities: data center computing and manufacturing leadership. The connected home business could be profitable and still not be strategic. Intel’s “non-core” became MaxLinear’s wedge into Wi‑Fi at real scale.

Inside MaxLinear, the logic was blunt. The company already had credibility in DOCSIS modems and gateways. But in the modern connected home, the experience is defined by Wi‑Fi. And MaxLinear didn’t have a first-class Wi‑Fi platform of its own. Kishore Seendripu called Wi‑Fi “a long-sought critical missing strategic element” and framed it as the growth catalyst for the overall business.

Then the world made the bet look prescient.

Work-from-home didn’t just increase broadband usage—it changed the baseline. Homes became offices, schools, and entertainment hubs all at once. Operators had to upgrade networks to handle sustained load, and consumers started treating home networking gear like essential infrastructure. MaxLinear suddenly had the right bundle at exactly the right time: broadband access plus in-home connectivity, under one roof.

As MaxLinear updated investors, it raised expectations for what the Intel assets would contribute, projecting roughly $80 million to $90 million in quarterly revenue at the outset—up from earlier assumptions. The company financed the deal with a term loan A facility that was upsized to $175 million from $140 million.

Of course, buying into Wi‑Fi also meant stepping into a brawl. With Intel’s technology, MaxLinear would now compete more directly in Wi‑Fi silicon against an established crowd that included Broadcom and Qualcomm, alongside players like MediaTek, Marvell, and others. But strategically, that was the whole point: Wi‑Fi wasn’t optional anymore. If MaxLinear wanted to be a “connected home” company in the 2020s, it needed a real seat at that table.

Intel’s portfolio also broadened the connectivity map around MaxLinear’s existing technologies. What it gained in DOCSIS, Wi‑Fi, DSL, and fiber access capabilities complemented MaxLinear’s positions in G.hn and MoCA—more ways to move data around the home and into the network, and more complete platform conversations with the same operator customers.

The human element mattered too. The integration brought in roughly 400 employees with Wi‑Fi and systems experience—exactly the kind of expertise MaxLinear needed to execute on Wi‑Fi 6 and push toward future roadmaps. The scale boost was immediate: MaxLinear moved toward an approximately $500 million annual revenue run rate, though the integration also brought near-term friction in the form of costs and inventory-related challenges.

At a high level, this was MaxLinear at its sharpest: find valuable assets a giant no longer wants, buy them at a price a mid-cap can digest, and plug them into a portfolio where they matter more. The bigger question was what came next. With a larger platform and a taste for bold moves, MaxLinear had increased its range—but also raised the stakes on execution.

By 2021, the company looked very different than it had just a few years earlier. It wasn’t only a cable silicon specialist anymore. It was trying to become a broader connectivity and infrastructure platform. And once you start thinking like a platform company, it’s hard not to keep reaching.

VII. Inflection Point #3: Silicon Motion & The Infrastructure Bet (2022–2023)

If the Intel acquisition showed MaxLinear at its sharpest, the Silicon Motion saga exposed the outer edge of what this company could realistically pull off.

In May 2022, MaxLinear agreed to acquire Silicon Motion Technology in a cash-and-stock deal valued at about $3.8 billion. The offer was pitched as the equivalent of $114.34 per Silicon Motion American depositary share, made up of $93.54 in cash plus 0.388 shares of MaxLinear.

The structure told you everything about the swing. MaxLinear planned to fund roughly $3.1 billion of cash consideration using cash on hand from the combined companies and fully committed debt financing from Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. After closing, MaxLinear shareholders were expected to own about 86% of the combined company, with Silicon Motion stockholders owning about 14%.

This wasn’t a tuck-in. It was MaxLinear trying to rewrite its own origin story.

The scale gap was jarring: a company with roughly a $1.5 billion market cap attempting to buy one around $3.5 billion. But the strategic argument wasn’t random. Silicon Motion was a leader in NAND flash controllers—the chips that sit at the heart of SSDs, translating raw flash into the high-speed storage your laptop, server, and data center depends on. Pair that with MaxLinear’s RF, analog/mixed-signal, and processing capabilities, and you could paint a picture of an “infrastructure semiconductor” company that touched both networking and storage.

The companies said the combination would create a more complete end-to-end platform stack and accelerate expansion into enterprise, consumer, and adjacent markets. They projected combined revenue of more than $2 billion annually and framed the addressable market opportunity at roughly $15 billion.

Kishore Seendripu leaned into the ambition: “The enhanced scale of the combined organization creates a new significant $2B+ player in the semiconductor industry with compelling positions across a diversified set of end-markets.”

And in 2022, you could see why the idea had heat. Data center infrastructure was converging. Storage performance was becoming inseparable from networking performance. And the AI infrastructure buildout was starting to turn “bandwidth everywhere” into the default requirement.

Then reality set in.

The deal needed regulatory approvals in multiple jurisdictions, including China, where U.S.-China tech tensions had turned approvals into a geopolitical chess match. Silicon Motion was NASDAQ-listed and headquartered in Taiwan, but it also had significant operations in mainland China—exactly the kind of footprint that could slow everything down.

By July 2023, the transaction was effectively out of runway.

Silicon Motion said that about 10 hours after China’s SAMR announced its approval of the merger, it received a termination letter from MaxLinear—something it described as a complete shock after more than a year of cooperative work toward closing. Silicon Motion said it would pursue arbitration in the Singapore International Arbitration Centre for substantial damages in excess of the termination fee, under the terms of the merger agreement.

MaxLinear responded publicly, saying it had terminated on multiple grounds, including that Silicon Motion had experienced a material adverse effect and multiple contractual failures, and that the decision was supported by what it called an indisputable factual record. MaxLinear said it was entirely confident in its decision.

The end result was simple: MaxLinear’s attempt to buy Silicon Motion was over.

Silicon Motion then commenced arbitration against MaxLinear for breaching the May 5, 2022 merger agreement, seeking payment of a $160 million termination fee as well as further substantial damages, interest, and costs.

The collapse was messy, expensive, and confidence-shaking. Both stocks swung around. The arbitration—and the size of that termination fee claim—hung over MaxLinear’s financial story. But the deeper damage was strategic: after a year of telling investors it was building a new $2 billion-plus diversified chip platform, MaxLinear was suddenly right back where it started, still a connectivity-and-infrastructure semiconductor company—just with more scrutiny.

You can find two readings of what happened, and the market oscillated between them.

One view said the termination was a dodge: MaxLinear avoided loading up on massive debt just as the semiconductor cycle turned down and the original economics started to look a lot less attractive than they had in early 2022.

The other view said this was what it looked like when ambition outran execution—and that regulatory delay didn’t just derail the deal, it gave MaxLinear an exit ramp it didn’t know how to build for itself.

Either way, the aftermath forced a reset. Without Silicon Motion’s SSD controller business, MaxLinear stayed a roughly $700 million connectivity and infrastructure player, not the scaled “everything infrastructure” semiconductor company the deal had promised. The question that followed wasn’t about the merits of storage controllers. It was whether MaxLinear could find its next leg through organic growth and smaller, more controllable moves—or whether the company had just spent a year proving that transformational M&A was a bridge too far.

VIII. The Modern MaxLinear: Portfolio & Positioning (2023–Present)

After Silicon Motion fell apart, MaxLinear came out the other side leaner—and forced into focus. But the timing was brutal. Fiscal 2024 was a down year across semiconductors, and MaxLinear got hit hard as customers worked through the excess inventory they’d built up during the COVID-era scramble. Revenue fell to $360.53 million, down from $693.26 million the year before.

Then the first signs of oxygen started to show up. By late 2024 and into 2025, results began to rebound: quarterly revenue reached $126.5 million, up 56% year-over-year and 16% sequentially. Earnings per share came in at $0.14, ahead of forecasts. Gross margins were 56.9% on a GAAP basis and 59.1% non-GAAP, and the company generated $10.1 million in operating cash flow.

“Our Q3 2025 revenue of $126.5 million represents 16% sequential and 56% revenue growth year over year and drives a substantial increase in non-GAAP net income both sequentially and year over year. Our focused investments in data center, optical interconnects, wireless infrastructure, PON, broadband access, Wi-Fi 7, Ethernet, and storage accelerator products are enabling us to lay the significant groundwork required for broadening customer traction, new and increased content opportunities, and sustained growth in 2026.”

That quote is basically the modern MaxLinear thesis in one breath: keep the broadband engine running, use Wi‑Fi to stay relevant at the edge, and push hard into infrastructure where the next wave of bandwidth spending is happening.

Today, the company organizes itself around four connected segments.

Broadband is the foundation—the cable modem, PON terminal, and DOCSIS infrastructure silicon that traces straight back to MaxLinear’s roots. Connectivity is the in-home layer: Wi‑Fi 6, 6E, and 7; home gateways; mesh networking—largely built from the Intel home gateway assets. Infrastructure is where the company is trying to earn its next identity, spanning optical networking (including PAM4 DSPs for data center interconnects), wireless backhaul, and 5G radio units. And Industrial & Multi-market is the diversification bucket—power management, interface products, and automotive connectivity—much of it tied to the Exar acquisition.

On an earnings call, management said it believes infrastructure revenue can reach $300 million to $500 million over the next two to three years. That’s an aggressive target, but it tells you where the company thinks the puck is going.

The geographic mix still has a notable tilt. In Q2 2025, Asia accounted for over 80% of total revenue. The end demand might be in the U.S. and Europe, but the supply chain—and many of the module makers and contract manufacturers—runs through Asia, and the revenue shows it.

In the near term, Wi‑Fi 7 is one of the clearest shots on goal. “At MaxLinear, we're not just leading the pack with Wi-Fi 7 technology; we're redefining it. Our single-chip tri-band device is an industry first, symbolizing a giant leap in wireless communication,” said Will Torgerson, VP/GM Broadband Group. “With our focus on power efficiency and peak performance, we're at the forefront of the Wi-Fi 7 revolution, offering blazing-fast speeds, reduced latency, and robust connectivity.”

MaxLinear’s Wi‑Fi CERTIFIED 7 SoC family, including the MxL31712 and MxL31708, targets the IEEE 802.11be standard. The company says its architecture combines tri-band access point functionality into a single Wi‑Fi SoC and is designed to improve throughput, latency, and performance across single-link and multi-link scenarios.

But the longer-term opportunity—and the one tied most directly to the AI infrastructure buildout—is optical interconnect. “With the explosion in deployments of AI clusters, the demand for multimode transceivers and AOCs continues to accelerate for 100G/lane 400G and 800G interconnects. These applications needed integrated, low-power, high-performance, cost-effective solutions to support the massive scale of these networks,” said Drew Guckenberger, Vice President of High Speed Interconnect at MaxLinear.

MaxLinear expects its optical products to generate between $60 million and $70 million of revenue in 2025. It says its Keystone PAM4 family has now been qualified at major data centers in the U.S. and Asia for 400-gig and 800-gig deployments—real signs of traction in a market where “qualified” is often the hardest word in the sentence.

One thing that has not changed, through all the pivots and deals, is leadership. Kishore Seendripu, Ph.D., remains co-founder, Chairman, President, and CEO—roles he has held since 2003. That kind of founder-CEO continuity is rare in semiconductors. It can be an advantage—long memory, consistent strategy, deep credibility. It can also invite the question: does continuity eventually become inertia?

Operationally, 2024 was also a year of tightening. MaxLinear ended the year with 1,294 employees as of December 31, a 26% reduction versus the prior year, reflecting cost controls and restructuring during the downturn.

So what is MaxLinear now, in plain terms? A specialized connectivity-and-infrastructure chip company coming out of a cyclical trough, with legitimate technology in Wi‑Fi and a growing footprint in optical. The upside is optionality—especially if the company can turn data center interconnect design wins into durable revenue. The risks are the ones that have always followed it: competing without the scale of Broadcom-class giants, staying too exposed to customers and categories that face secular pressure, and proving—after the Silicon Motion saga—that execution can match ambition.

IX. Technology Deep Dive: What MaxLinear Actually Does

To understand MaxLinear, you have to zoom in on a part of semiconductors that doesn’t get the spotlight. Not CPUs. Not GPUs. Not the clean, orderly world of digital logic.

MaxLinear lives in the messy part of reality—where information rides on radio waves, copper, and light.

The company’s founding idea was straightforward and ambitious: take complicated communications functions that used to require multiple chips, and collapse them into a single, highly integrated piece of silicon. If you can do that, you don’t just make things smaller. You make them cheaper, more power-efficient, and easier for customers to design into real products at scale.

That’s the mixed-signal/RF job. The physical world produces continuous, noisy signals. Computers want clean 1s and 0s. The chips MaxLinear builds sit at that boundary, dealing with interference, distortion, and signal loss—and still squeezing as much data as possible out of whatever medium they’re given.

A cable modem is a perfect example. The coax line coming into a home can carry TV, internet, and voice simultaneously, separated into frequency bands. To make that usable, you need silicon that can lock onto the right channels, reject what it doesn’t want, amplify what it does, and convert those analog waveforms into digital streams without adding its own errors along the way. That’s not glamorous work. But it’s essential work—and it’s hard.

That’s also why the DOCSIS roadmap matters. DOCSIS 4.0 is cable’s answer to the “fiber is inevitable” narrative: push multi-gigabit performance over an infrastructure that, in many places, was originally built for one-way TV broadcast. MaxLinear’s Puma 8 DOCSIS 4.0 platform is aimed at that world, and the company has said it expects to demonstrate more than 9 Gbps using ESD/FDD technology. The pitch isn’t just speed for speed’s sake—it’s giving service providers a path to upgrade on their own timeline, including cost and power optimization for Ultra DOCSIS 3.1.

Wi‑Fi is the same kind of physics problem, just in a different arena. Instead of coax, you’re dealing with air: signals reflecting off walls, colliding with neighboring networks, and fighting for spectrum with everything from Bluetooth devices to microwave ovens. Wi‑Fi 7 pushes performance with wider channels (up to 320 MHz), higher-order modulation (4096‑QAM), and Multi‑Link Operation so devices can transmit across multiple bands.

MaxLinear has positioned its Wi‑Fi 7 SoCs around that leap, describing a single‑chip tri‑band access point solution built to the IEEE 802.11be standard (also called Extremely High Throughput). The company has said its Wi‑Fi 7 platform can deliver 11.5 Gbps peak throughput on the 6 GHz spectrum.

Then there’s optical interconnect—arguably the most demanding corner of the portfolio, and the one most tied to the AI data center buildout. When AI clusters scale out, bandwidth between servers and switches becomes a bottleneck. Optical links using PAM4 modulation can deliver 100 Gbps per lane, and 400G and 800G transceivers aggregate multiple lanes to reach the speeds modern data centers require.

MaxLinear’s bet here is its Keystone family of PAM4 DSPs, including an 800G DSP built on 5nm CMOS. The company positions Keystone as its third generation of PAM4 DSPs, emphasizing integration, small form factors, and power efficiency across 400G and 800G transceiver use cases. It has also said Keystone enables sub‑8W 400G module designs (like QSFP112 and QSFP‑DD) and sub‑15W 800G designs (like QSFP‑DD800 and OSFP).

This market also makes the competitive dynamics easy to see. According to supply chain research cited here, Marvell’s quoted pricing for the DSP in an 800G optical module is around $90–$100, with the TIA + Driver around $40–$50. By comparison, Broadcom and MaxLinear’s 800G DSP pricing is cited at roughly $50–$60. And the field is getting more crowded: Broadcom and MaxLinear qualifying 800G DSPs, while Macom and Semtech qualify TIA + Driver components with module customers.

That pricing gap hints at MaxLinear’s recurring strategy. It’s often not trying to out-platform the biggest players with an end-to-end stack. It tries to win specific sockets by being very good—sometimes cheaper—at the hard mixed-signal piece.

And that’s the through-line across the company’s entire story. MaxLinear doesn’t sell routers, servers, or AI systems. It sells the silicon that lets those systems move information through coax, through the air, and through fiber. So when a cable operator upgrades its network, when a router brand ships a Wi‑Fi 7 gateway, or when a hyperscaler qualifies a new generation of optical modules, MaxLinear can be inside—all but invisible, but doing the work that makes the whole experience feel effortless.

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

MaxLinear’s two-decade run is a compressed case study in how semiconductor companies survive—or don’t—when platforms shift, customers consolidate, and cycles swing from boom to bust.

The details are specific to MaxLinear. The patterns aren’t.

The Fabless Model’s Double Edge

MaxLinear’s founding bet on fabless design gave it a huge head start on capital efficiency. It built to an IPO while burning less than $20 million of venture money, largely because it didn’t have to fund the expensive, endless treadmill of building and maintaining factories. That freed the company to spend its scarce resources where it believed advantage actually lived: engineering and integration.

But fabless is also a dependency story. When foundry capacity tightens, MaxLinear doesn’t set the schedule—it gets in line behind the biggest, most important customers. In calm markets, the model looks like magic. In supply shocks, it can turn into a bottleneck you don’t control.

Platform Risk Management

MaxLinear’s history is basically a sequence of platform transitions: from early TV tuner success, to cable and satellite, then into broadband infrastructure, and finally into Wi‑Fi and optical interconnect. Each shift was a reminder that “core markets” don’t stay core forever. The cable set-top box business that helped fund the IPO is now in secular decline, and many of the companies that lived and died by that market simply disappeared or got absorbed.

The lesson is uncomfortable but simple: even great platforms decay. Diversification is hardest before it’s obviously necessary—and that’s exactly when you need to do it.

M&A as Strategy

If there’s a through-line to MaxLinear’s strategy, it’s that acquisitions weren’t occasional—they were a primary tool for reinvention.

Entropic was consolidation: more scale and more share in a market that was already maturing. Exar was diversification: new categories, new customers, and a broader analog/mixed-signal catalog. The Intel Home Gateway deal was the most “plot-changing” move, because it filled a missing layer—Wi‑Fi and gateway SoCs—at a price MaxLinear could afford, right as home connectivity became critical infrastructure.

And then there’s Silicon Motion, which showed the other side of the playbook: once deals get big enough, the risk isn’t just integration. It’s financing, timing, regulators, and macro conditions—things you can’t engineer your way out of. The ambition was clear. So was the execution risk.

Founder-CEO Longevity

Kishore Seendripu leading MaxLinear for more than twenty years is rare in semiconductors, an industry where boards often swap CEOs after a missed cycle, and where consolidation and rollups frequently bring in new management.

There are real benefits to that continuity: long memory, consistent strategic direction, and deep customer and ecosystem relationships. But the tradeoff is just as real. Founder-led continuity can slip into inertia, and it raises a governance question that never quite goes away: is leadership being challenged hard enough, often enough, by the board and the organization?

Specialization vs. Scale

MaxLinear’s position captures one of the central tensions in semiconductors. Specialists can win by being exceptional at a hard technical problem—mixed-signal integration, power efficiency, optical DSPs—and that can support strong gross margins in the right sockets.

But scale is its own advantage. It buys bigger R&D budgets, more leverage with customers, broader platforms, and the ability to amortize engineering across massive volumes. Broadcom generates more operating profit in a quarter than MaxLinear generates in annual revenue. That kind of gap isn’t just a statistic—it’s a strategic gravity field that shapes what smaller companies can realistically take on.

Customer Concentration Reality

In infrastructure and connectivity, customer concentration isn’t a risk you “solve.” It’s a condition of the market. There are only so many major cable operators, hyperscalers, and telecom equipment vendors—and they’re sophisticated buyers with enormous negotiating power.

Those same customers are also increasingly capable of designing silicon themselves. So MaxLinear’s job is to keep delivering enough performance, integration, and economics that building it in-house doesn’t pencil out. That value equation shifts over time, especially as customers get larger and more confident.

Cyclicality as Feature

MaxLinear got hit hard in the 2022–2024 correction, with revenue falling roughly 50% from peak to trough. But the cycle is not just something that happens to semiconductor companies—it’s also where strategic openings appear.

The Intel home gateway assets were available during COVID uncertainty, when priorities were shifting and sellers were motivated. The Silicon Motion breakup came after valuations and expectations had compressed. In semis, the companies that keep financial flexibility through the downcycle are the ones that can buy capability at the moment others are cutting back—and come out of the trough with a better portfolio than they went in with.

XI. Competitive Dynamics & Structural Analysis

To understand where MaxLinear sits in the semiconductor food chain, you have to look at two things at once: the structure of the industry, and the specific advantages—and constraints—of being a mid-scale, fabless mixed-signal specialist.

Porter's Five Forces Assessment

The threat of new entrants is moderate. Mixed-signal and RF talent takes years to develop, real customer relationships are built across multiple product generations, and IP portfolios create real friction for anyone trying to design around an incumbent. But the fabless model lowers the upfront capital barrier, and venture-backed specialists like Credo and Alphawave show that teams can still break in—especially in narrow, fast-growing niches. In practice, though, MaxLinear’s bigger danger isn’t the startup in a garage. It’s the adjacent giant that can simply expand into your category.

Supplier power is a constant undercurrent for any fabless company. MaxLinear relies on outside foundries for wafer manufacturing and third-party contractors for assembly and test. Historically, the company used third-party contractors in Asia for manufacturing and assembly, and in 2010 all of its chips were made by United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) at foundries in Taiwan and Singapore. Over time, dependence on large foundries like TSMC, GlobalFoundries, and UMC creates concentration risk. The one mitigating factor is that MaxLinear often uses mature process nodes, which can offer more flexibility than companies competing for scarce leading-edge capacity.

Buyer power is high—and it’s getting higher. Cable operators like Comcast and Charter, equipment OEMs like Cisco and Arris, and increasingly hyperscalers all have enormous leverage. Multi-sourcing is normal. Switching doesn’t happen overnight, but it does happen at product refreshes, and buyers know it. Design wins are sticky, but they’re not forever, and they don’t carry anything like the lock-in you see in enterprise software.

Substitution threats are real and persistent. Fiber-to-the-home is a long-term substitute for parts of the cable ecosystem. Vertical integration—large customers building their own chips—is a broader existential threat to merchant silicon suppliers across the industry. And software-defined networking can, in some cases, shift value away from specialized silicon. All of that forces companies like MaxLinear to keep reinvesting just to maintain relevance.

Competitive rivalry is brutal. MaxLinear’s top 13 competitors are Semtech, MACOM, Silicon Labs, NXP, MediaTek, Broadcom, Rafael Micro, Marvell, Qorvo, Texas Instruments, HiSilicon, Analog Devices and MPS. When you line it up that way, the dynamic becomes obvious: MaxLinear is often fighting companies that are either much larger, much more diversified, or both. Against Broadcom, the fight is rarely about out-platforming it. It’s about winning on specific attributes—power efficiency, integration choices, and pricing flexibility. In optical, Marvell is a major reference point, and MaxLinear positions itself as a credible alternative at more aggressive price points.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework

Scale economies are a weak point. Broadcom can spend more on R&D in a year than MaxLinear brings in as revenue, which changes everything: how many bets you can place, how broad a platform you can build, and how much you can absorb a mistake. Being fabless helps on manufacturing scale dynamics, but it doesn’t solve the core issue that larger competitors can amortize R&D and customer coverage across much bigger volume.

Network effects basically don’t exist here. Semiconductor companies don’t get stronger because more people “use” them the way consumer platforms do. Standards participation—MoCA, DOCSIS—matters for staying relevant, but it’s not a defensible network effect.

Counter-positioning used to be more meaningful. MaxLinear’s early bet on CMOS-based RF went against legacy approaches like GaAs, and the Intel home gateway acquisition was a clear example of taking something a giant considered non-core and making it central. Today, the company is more often competing as an alternative supplier than as a fundamentally different approach.

Switching costs are moderate. Once you’re designed into a platform, you tend to stay there for a while—design-in cycles can last 18 to 36 months, and customers invest in software, reference designs, and validation. But transitions are natural reset points, and multi-sourcing reduces lock-in. MaxLinear benefits from switching costs, but it can’t rely on them.

Branding is weak as a structural advantage. This is not a consumer business. Reputation with engineers and procurement teams matters, but it’s earned through support and performance, not brand gravity.

Cornered resources are limited. Kishore Seendripu’s long tenure provides continuity, but dependence on any single individual is fragile. Talent is valuable, but it’s poachable. IP helps, but rarely creates an unassailable wall in semiconductors.

Process power is moderate. Two decades of accumulated mixed-signal and RF integration experience is real advantage—you can’t shortcut it. But with enough time and money, well-funded competitors can develop comparable capabilities.

Overall Assessment

MaxLinear plays in attractive markets, but it doesn’t have dominant structural advantages. Its success has come from execution, selective M&A, and making the right platform bets at the right time—more skill than power. That leaves it in a tricky middle zone: too small to fight Broadcom and Qualcomm on scale, too big to move like a tiny specialist, and still exposed to the reality that in semiconductors, the ground eventually shifts under every “core” market.

XII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

The core bullish story is that MaxLinear is finally aligned with where bandwidth spending is headed. Fiber keeps getting deployed globally. Wi‑Fi 7 is moving from demos to real rollouts. And the AI data center buildout is turning optical interconnect from “nice-to-have” into a requirement. MaxLinear has credible positions in all three.

You can see that ambition in the product push. Its Keystone PAM4 family is aimed squarely at high-speed optical links, and its Sierra Radio SoC has been gaining customer traction—most notably being selected by Pegatron 5G for next-generation 5G Open RAN macro radio units. The company also unveiled its Panther V storage accelerator, targeting enterprise and hyperscale data centers—another signal that it wants to be more than “just broadband.”

The second bullish leg is diversification. MaxLinear is no longer a one-platform company. Broadband is still the base, but connectivity, infrastructure, and industrial/multi-market broaden the revenue map and, in theory, reduce the risk that any one market slowdown becomes existential. The Intel home gateway acquisition is the proof point here: it filled the Wi‑Fi hole that used to cap MaxLinear’s relevance at the edge of the network.

Then there’s the positioning argument. MaxLinear tends to win in the zones where power efficiency, integration, and cost matter, and where the largest players’ premium pricing leaves room for a strong alternative. Profitability suggests it’s not a commodity supplier: MaxLinear’s non-GAAP gross margin of 59.1% is competitive—roughly in the neighborhood of peers like Texas Instruments (57.42% in Q3 2025) and Analog Devices (55.69%), though still below Broadcom (67.10%).

A more subtle bull case is that the Silicon Motion experience may have forced discipline. The termination was painful, but it also meant MaxLinear avoided loading up on massive debt at a potentially bad point in the cycle. If management takes the lesson as “smaller, more controllable deals,” that could set up smarter tuck-ins rather than another moonshot.

Finally, there’s the market setup. If MaxLinear executes and the portfolio starts to look more like an infrastructure compounder than a cyclical broadband supplier, a valuation re-rating is possible. Today, it trades at lower multiples than many growth-oriented semiconductor names, leaving room for upside if confidence returns. And Kishore Seendripu’s continuity cuts both ways—but in the bull case, it’s an asset: a twenty-year record of navigating transitions, backed by technical credibility and deep industry relationships.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with a harsh structural fact: scale matters in semiconductors, and MaxLinear doesn’t have it. Broadcom, Marvell, and Qualcomm can outspend it in R&D, offer broader platforms, and absorb missteps that would be painful for a mid-cap. As design costs rise—especially at advanced nodes—the gap can widen, not shrink.

Then there’s customer concentration and platform exposure. Cable operators remain a major gravity well, and that ecosystem faces secular pressure as cord-cutting continues. At the same time, operator consolidation concentrates buyer power further. Even if MaxLinear executes well, it’s still tethered to a platform that isn’t growing like it used to.

The company’s M&A history is also a source of skepticism. Entropic was difficult to integrate. Silicon Motion didn’t close and turned into a public, expensive fight. Whether you blame management judgment, geopolitics, or bad luck, the takeaway is the same: acquisition-driven “step change” growth is hard, and MaxLinear has scars.

Profitability is not immune either. Competitive intensity and customer leverage can squeeze margins, especially for a mid-scale supplier without dominant pricing power. Revenue can recover while margins stall—or even compress—if wins come at the cost of pricing.

Technology transitions remain a constant risk. Optical interconnect is promising, but MaxLinear is competing against more established positions, especially Marvell. Wi‑Fi 7 is crowded, with Qualcomm, Broadcom, and MediaTek all fighting for the same sockets. In these markets, “good” doesn’t always win—roadmaps, ecosystem leverage, and platform bundling matter.

Layer on geopolitics and the risk profile gets sharper. The Huawei ban already hit the business. Foundry dependence in Taiwan adds supply chain exposure. And China’s regulatory complexity was part of the Silicon Motion story, showing how quickly external factors can derail strategy.

Finally, there’s the long-term existential risk facing all merchant silicon suppliers: vertical integration. Hyperscalers like Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta keep designing more of their own custom silicon. If that trend accelerates, the addressable market for third-party chips can shrink, and the remaining sockets become even more competitive.

Key Metrics to Track

For investors following MaxLinear, two metrics matter because they tell you whether the company is actually becoming what it says it is:

Revenue mix evolution—especially Infrastructure as a percentage of total revenue. This is the clearest indicator of whether MaxLinear is pivoting toward higher-growth markets or staying anchored to legacy broadband. Management’s view that infrastructure revenue can reach $300 million to $500 million over the next two to three years creates a simple yardstick.

Gross margin trajectory—currently around 59% non-GAAP. This is the scoreboard for differentiation and pricing power. Holding above the high-50s suggests the portfolio is winning on value, not just volume. Sliding toward the mid-50s would be a sign that competition and customer leverage are taking the upper hand.

XIII. Epilogue: What Comes Next?

As 2025 comes to a close, MaxLinear is back at a familiar crossroads. The semiconductor cycle has moved off the bottom and into recovery. AI infrastructure has opened up demand that barely existed on MaxLinear’s roadmap a few years ago. And the company now has real shots on goal in two places that matter: Wi‑Fi 7 at the edge, and optical interconnect in the data center.

The biggest question is the one everyone is asking in some form: can MaxLinear win meaningful share in AI data center networking, or did it arrive too late? Keystone, its PAM4 product family, has earned qualifications at major customers—no small feat. But optical is a knife fight. Marvell is already deeply entrenched, and Broadcom has the resources to make almost any market brutally competitive. Over the next five years, MaxLinear’s ability to turn those qualifications into sustained, expanding deployments may matter more than any other single factor.

The second thing to watch is consolidation—because semiconductors is always consolidating. MaxLinear has assembled a portfolio that could be attractive to a larger buyer looking for optical, broadband access, or connectivity assets. Names like Marvell, Microchip, or private equity come up in any “who could buy whom?” conversation. At the same time, the Silicon Motion episode is a reminder that dealmaking cuts both ways: MaxLinear has shown it wants to be an acquirer, but also that large, complex transactions can consume a year of management attention and still end in a very public reset.

That’s why the most plausible near-term path is the least dramatic one: organic execution. Keep prioritizing profitability and cash generation. Use selective, tuck-in M&A where integration is controllable and the strategic fit is obvious. If MaxLinear can build a sustainably profitable business in a handful of valuable niches, it doesn’t need to out-scale the giants to create real long-term shareholder value.

The wildcards, as always in semiconductors, are the next platform transitions. 800G is ramping, and 1.6T is already on the horizon. Wi‑Fi 8 will eventually follow Wi‑Fi 7 into the market. New broadband standards will keep shifting the economics of last-mile connectivity. Even longer-dated ideas—like quantum networking—represent the kind of “maybe it’s nothing, maybe it’s everything” wave that can either create a new category or distract a company into the wrong bet. MaxLinear’s history suggests it can adapt. The question is whether it can adapt fast enough, and with enough discipline, to translate that adaptation into durable value.

Then there’s leadership—still one of the most unusual parts of the story. Kishore Seendripu’s eventual succession, whenever it happens, will be the biggest leadership change in MaxLinear’s history. For investors, that makes board composition and succession planning more than governance footnotes; they’re strategic variables.

Zooming out, MaxLinear is a concentrated case study in what it takes to survive as a mid-scale specialist in a consolidating industry. It has navigated multiple technology transitions. It has repeatedly used M&A to patch gaps and widen its product map. It has put itself in growth markets that matter. What it has not yet proven—at least not in a way the market will fully credit—is that those positions translate into a sustained competitive advantage that can compound through cycles.

The surprises in the history underline the point. The Intel acquisition looked opportunistic at the time, but it turned out to be genuinely transformational for the portfolio. The Silicon Motion bid was breathtakingly ambitious—and it revealed just how thin the margin for error becomes when you try to buy scale instead of building it. And simply staying alive through multiple platform shifts is its own achievement in an industry filled with specialists that never made it to the next transition.

For founders and executives building in similar terrain, MaxLinear’s experience offers a few hard-earned lessons: capital efficiency buys you time when cycles turn; M&A can accelerate a roadmap, but big deals multiply risks you can’t engineer away; founder-CEO continuity can be a strength, but only if the organization has strong counterweights and fresh thinking around the table; and even world-class technology needs a strategy for competing in a world where scale shapes access to the largest accounts.

MaxLinear heads into 2026 with recovering revenue, improving profitability, credible positions in growth categories, and the battle scars of two decades in the semiconductor trenches. Whether the next decade brings continued independence, a strategic acquisition, or another reinvention, the arc of the company already makes one thing clear: in semiconductors, survival is never the finish line. It’s the entry ticket.

XIV. Resources for Further Research

Top Long-Form Resources:

- MaxLinear Investor Relations annual 10-K filings (2010–2024) — the cleanest way to track how the business mix, customers, and risk factors evolved over time

- The Fabless Semiconductor Industry by Daniel Nenni & Paul McLellan — helpful context on the model MaxLinear built around, and why it works until it doesn’t

- Intel Home Gateway Platform acquisition press releases and analysis (April–August 2020) — primary sources on the deal that vaulted MaxLinear into Wi‑Fi and gateway SoCs

- Silicon Motion acquisition saga coverage (Bloomberg, Reuters, EE Times; May 2022–September 2023) — the chronology, the regulatory grind, and the breakup

- DOCSIS evolution whitepapers from CableLabs — the technical backbone behind the cable upgrade cycles MaxLinear sells into

- Wi‑Fi Alliance standards documentation — accessible briefs on Wi‑Fi 6/6E/7 that map directly to the connectivity roadmap

- Optical Internetworking Forum (OIF) publications — roadmaps and standards work that frame the data center interconnect opportunity

- McKinsey semiconductor industry reports — a big-picture view on cycles, consolidation, and why mid-cap chip companies face structural pressure

- Competitor investor presentations (Broadcom, Marvell, Credo, Astera Labs) — useful for understanding how peers position themselves, and where MaxLinear overlaps or diverges

- Dell’Oro Group broadband research — specialist coverage of broadband access markets and operator-driven demand signals

Key Industry Publications: EE Times, Light Reading, and Broadband Technology Report for telecom and infrastructure coverage; Semiconductor Engineering and SemiWiki for deeper technical reporting on chip design, process tech, and manufacturing trends.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music