Microvast Holdings: The Battery Bet That Went Public

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

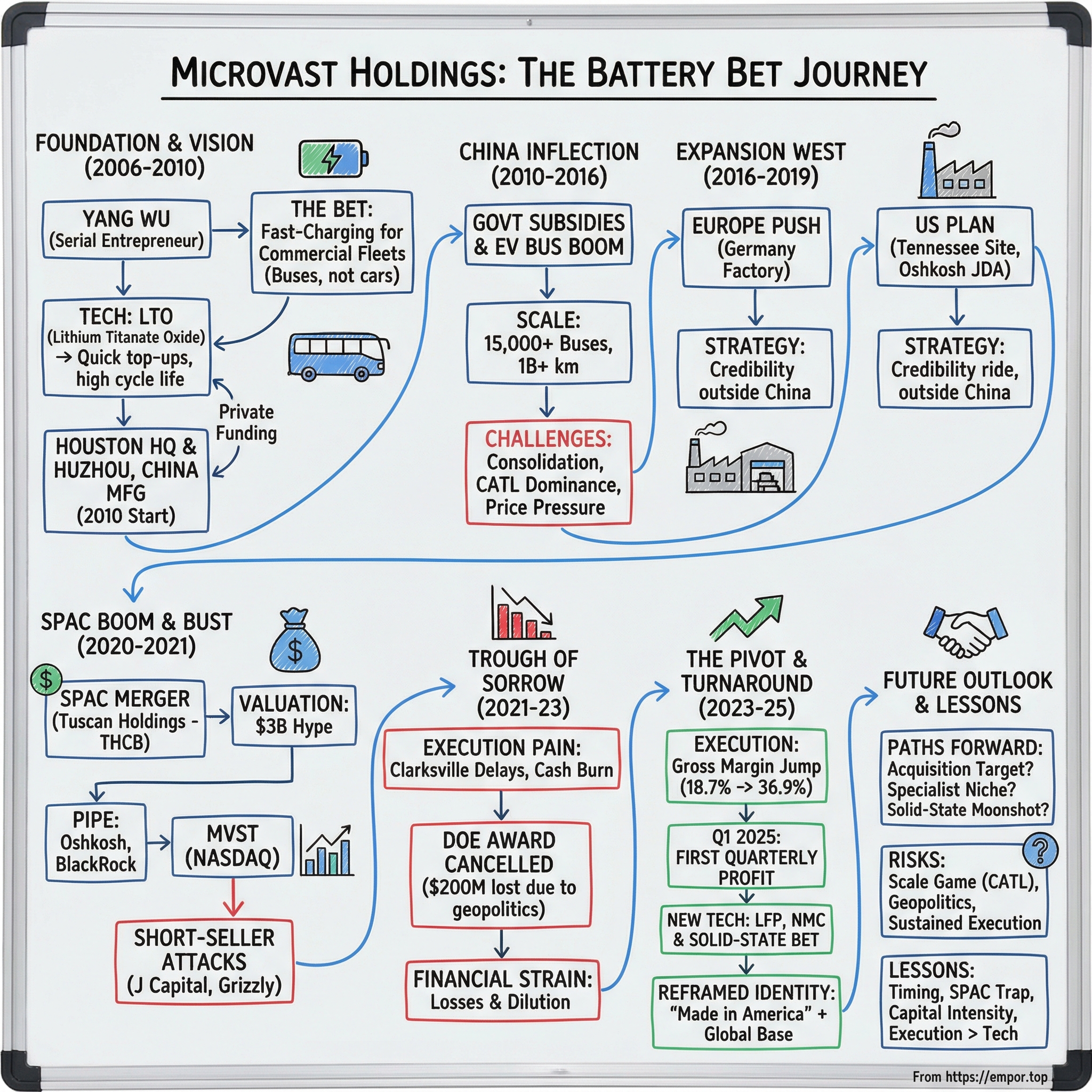

Picture this: a Chinese-born entrepreneur who’d already built and sold companies in oil services and water treatment makes a bet in 2006 that most people would’ve laughed out of the room—that fast-charging batteries were going to be the unlock for electric vehicles. Not for sleek sedans. For buses. City buses. Commercial fleets. The unglamorous machines that keep cities moving.

Nearly two decades later, that bet became Microvast, founded by Yang Wu in 2006 in Houston, Texas, along with its Chinese subsidiary, Microvast Power Systems in Huzhou, China. Today it trades on the NASDAQ under MVST, after one of the wildest rides in modern cleantech: real traction in China’s electric bus boom, a made-for-2021 SPAC debut, short-seller crossfire, years of execution pain… and a comeback attempt that’s still unfolding.

The tension at the heart of Microvast is the one that stalks every hardware company: can great technology become a great business when the industry is dominated by giants? CATL controls roughly 38% of the global EV battery market. BYD is around 17%. LG Energy Solution sits near 12%. CATL continued to remain the world's largest power battery maker in 2024, with a 37.9 percent share that is higher than the 36.6 percent in 2023. Microvast? It’s not on the global leaderboard.

And yet, it’s still here. More than that—in Q1 2025, Microvast achieved record company Q1 revenue, increased 43.2% year over year to $116.5 million, with gross margin increased from 21.2% to 36.9%. After years of losses, it posted its first quarterly profit. The Tennessee factory that once felt like a perpetual promise has become the backbone of its “Made in America” narrative.

So how did a Chinese-founded battery company end up in Tennessee, go public via SPAC, survive the cleantech bloodbath, and re-emerge as a plausible—if still improbable—survivor? That’s what we’re here to unpack. Microvast is the battery world’s middle child: not as dominant as CATL, not as moonshot-hyped as QuantumScape, but arguably closer to commercial reality than either.

Here’s the roadmap. We’ll start with the founder’s vision and the first battery dream. Then we’ll hit the inflection point: winning in Chinese electric buses. From there, the push into Europe and America, the SPAC boom and bust, the trough of sorrow, and the recent signs of a turnaround that have investors asking whether this beaten-down stock finally has legs. Along the way, we’ll pressure-test Microvast with Porter’s Five Forces and Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, and we’ll close with the bull and bear cases—without pretending this is an easy story with a clean ending.

II. Founder Origins & The First Battery Dream (2006–2010)

Yang Wu and his wife arrived in the United States in 1994, epitomizing the embodiment of the American dream. Wu would later describe it more personally: "I'm proud to be a Chinese American. My wife and I first came to America in 1994 to pursue the American Dream. I wanted a better life with freedom and opportunity, for myself and my family."

But Microvast didn’t come from a straight line. Before batteries, Wu built businesses in industries that couldn’t be more different.

First, oilfield services. From 1989 to 1996, Mr. Wu was the founder of World Wide Omex, Inc., an agent for a large oilfield service company. Then construction engineering. From 1996 to 2000, Mr. Wu served as chief executive officer and founder of Omex Engineering and Construction Inc. And then water treatment—where he not only built something real, but exited it. From 2000 to 2006, Mr. Wu served as chief executive officer at Omex Environmental Engineering Co., Ltd., a water treatment company, which he founded and was acquired by Dow Chemical Company in 2006.

That sale mattered. It provided capital, but maybe more importantly, it reinforced a pattern: spot a coming shift, build the capability, and scale. By one account, Microvast wasn’t even close to his first swing. Mr. Wu is a very experienced entrepreneur with Microvast being his eighth successful business. The question in 2006 wasn’t whether he could start another company. It was what problem was worth a decade of his life.

The EV world in 2006 was a very different universe. Tesla was still showing prototypes. A123 Systems was winning buzz for lithium iron phosphate batteries. And the era that would later get labeled “cleantech 1.0” was just getting started—big promises, big funding rounds, and, eventually, a lot of wreckage.

Wu’s thesis wasn’t “EVs will be cool.” It was more specific, and more commercial. Microvast’s name captured the philosophy: "The name 'Microvast' reflects Yang Wu's belief that small improvements in battery components can have a big, long-term impact on the environment." But the business insight was blunt: early electric vehicles didn’t just have a range problem. They had a time problem.

If you’re a consumer, maybe you can live with charging overnight. If you run a fleet, downtime is the enemy. A bus sitting still isn’t just inconvenient—it’s lost service, lost utilization, lost money. Wu’s bet was that if you could turn charging from an all-night event into something closer to a pit stop—say, minutes instead of hours—you could make electrification viable for the kinds of vehicles that actually rack up miles.

Yang Wu is the founder of Microvast and has been its Chairman, Chief Executive Officer and director since its inception in October 2006. Microvast incorporated in Houston, Texas—but from day one, the operational plan pointed across the Pacific. "Just like many American companies, we decided to develop and manufacture our products in China first because of the early adoption of electric vehicles there."

This wasn’t simply about cheaper labor. China already had the gravity: battery supply chains were largely in Asia, manufacturing know-how was concentrated there, and Chinese cities were starting to take electric buses seriously in a way that few Western governments were.

By the end of the decade, Microvast had product, and it had a place to build it. It introduced its first generation of batteries in 2009, with manufacturing starting in 2010 in Huzhou factory. And it had made its core technology choice: lithium titanate oxide, or LTO.

LTO is one of those chemistries that sounds like a footnote until you see what it enables. Microvast’s version was branded “LpTO.” Microvast, based in Houston, Texas, makes a lithium-titanate battery that it calls "LpTO". In 2011, the world's first ultrafast charge bus fleet was launched in Chongqing, China. An 80 kWh LpTO battery system was installed in 37 twelve-meter electric buses, which can be fully charged within 10 minutes with a 400 kW charger.

The appeal was all about the use case. The lithium-titanate battery has the advantages of a longer cycle life, a wider range of operating temperatures, and of tolerating faster rates of charge and discharge than other lithium-ion batteries. The primary disadvantages of LTO batteries are their higher purchase cost per kWh and their lower energy density. That’s a deal you’d never take if you’re selling a consumer car on “how far can it go.” But if you’re powering a bus that runs predictable routes all day and you can top it up quickly, cycle life and fast charging can beat energy density.

Microvast leaned into that performance edge. Microvast's LpTO Lithium-Titanate Battery Technology has the ability to accept up to 20C high-rate charging, which translates into 5-10 minute fast-charging for your vehicle. This was the wedge: not the biggest battery, but the one that could charge fast, survive hard duty cycles, and keep working.

The early money was private. "Microvast started with private funding, though the exact amounts from that time aren't public." By around 2010, Wu had done the hard part that kills most battery startups: he’d moved from idea to manufacturing. Now came the part that kills most of the rest—getting customers to bet their fleets on it.

III. The Inflection Point: Winning in Chinese Electric Buses (2010–2016)

China’s New Energy Vehicle push changed the rules of the game. In the early 2010s, Beijing poured massive subsidies into EV adoption, with public transportation at the top of the list. Cities weren’t just encouraged to electrify their bus fleets—they were effectively told to. The money was real, the timelines were tight, and the market was enormous.

"Early success in China's electric bus market helped prove the technology's value. The early growth of the Microvast company was marked by significant developments, particularly within the Chinese market." Microvast landed in the sweet spot. Bus operators didn’t need the highest energy density battery on earth. They needed buses that could stay in service all day. And Microvast’s fast-charging LTO approach fit that operational reality: quick top-ups, long cycle life, fewer headaches.

Then came the customer list—the kind that turns a battery company from “interesting” into “real.”

"We can count as our customers some of the leading global bus OEMs including Yutong, Higer, Foton, King Long, VDL and Wright Bus." And it wasn’t just a logo slide. Microvast became the main battery supplier for China's New Energy bus makers, providing batteries on new energy buses for eight bus makers, including such well renowned brands as Yutong, Foton, North Bus, Wuzhoulong and CRRC.

To get why that mattered, start with Yutong. As of 2016, Yutong was the largest bus manufacturer in the world by sales volume. If you could win there—if you could get designed into buses rolling off the line at scale—you weren’t just shipping packs. You were getting validated in the most demanding, most high-volume proving ground on the planet.

By the late 2010s, Microvast was being described in language every hardware startup dreams of hearing. By 2017, Microvast was described as "a fast-growing and profitable market leader in the design, development and manufacturing of safe, ultra-fast charging, long-life lithium-ion battery systems." The company had supplied more than 15,000 hybrid and fully electric buses with battery systems, operating in more than 100 cities across six countries with over one billion kilometers traveled.

And the footprint kept expanding. "The company has supplied more than 20,000 hybrid and fully electric buses with battery systems, operating in more than 150 cities across six countries with over one billion kilometers traveled."

Underneath those deployments was the unsexy part that makes them possible: manufacturing. In Huzhou, Microvast was building the kind of industrial machine you need to survive in batteries. "Microvast's manufacturing plant in Huzhou, China has more than 2,500 employees working across three production facilities. These are all in full operation." And it was still adding capacity. "By March, 2017, it began construction on its 'Phase III' production facility in Huzhou."

But this wasn’t a quiet corner of the market for long. Subsidies attract competition the way honey attracts ants—and China’s electric bus boom pulled in the biggest, best-capitalized players in the industry. CATL and BYD were scaling fast, and the market started to consolidate hard. "CATL's market share grew from 79% in 2022 to 87% in 2023. Correspondingly, the market share of smaller suppliers decreased." Those figures came later and reflect the broader heavy-duty landscape, but the direction of travel was already clear: the game was tilting toward scale, cost, and political gravity.

Microvast still had a niche—fast-charging applications where cycle life and uptime mattered more than anything. But the easy years were ending. Competitors were improving, price pressure was rising, and the subsidy tailwind that had powered the entire category was starting to weaken.

That forced the next strategic question: keep fighting for share in an increasingly brutal China market, or take what it had proven—technology, deployments, credibility—and try to win somewhere else.

Microvast chose to go global. And that decision would define the next decade.

IV. Going West: The Shift to Europe & America (2016–2019)

The pivot west wasn’t just about growth. It was about risk—how do you keep building a global battery business when China’s market is consolidating around national champions, geopolitics are getting sharper, and customers in the West are starting to ask an uncomfortable question: do we really want our batteries to come from one place?

Microvast’s first foothold was Europe. In July 2020, Microvast inaugurated its new Germany factory in Ludwigsfelde, with production planned to start in March 2021. Think of it as a credibility play as much as a capacity play: closer to European OEMs, a manufacturing footprint outside China, and a way to answer “local content” concerns with something more than a promise.

And it got noticed. "Olaf Scholz, German Vice-Chancellor & Federal Minister of Finance, further recognized Microvast's innovative approach to next generation battery technologies at an onsite visit to the Company's EMEA headquarters in June 2021."

But the bigger bet was always the United States. "In 2019, in consultation with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Microvast began planning the establishment of a Li-ion battery facility in the United States." That planning turned into a public announcement in February 2021: "Tennessee officials and Microvast announced that the company will establish a new manufacturing facility in Clarksville to manufacture battery cells, modules and packs."

Why Clarksville? Microvast didn’t just pick it off a map. "We shopped. We looked around at different places in the United States, particularly sites in the Northwest and Southeast. Tennessee is really good at providing a conducive environment for a company to stick a flag in."

Clarksville also came with practical advantages. "Clarksville's assets included possible partnerships with Austin Peay State University, having the Clarksville Regional Airport for use by customers, and having a steady supply of workers thanks to Fort Campbell." The nearby base mattered for another reason too: "Microvast is a proud employer of many American veterans, including myself, and we look to continue that tradition at our Clarksville facility."

On paper, the commitment was real. "Microvast plans to invest $220 million and create 287 jobs in Montgomery County." The site itself left room to grow. "The Clarksville facility includes approximately 82 acres of land, providing immediate additional expansion opportunities and anticipated future manufacturing capacity of up to 8 GWh annually."

Then came a piece of timing that, in 2021, investors couldn’t ignore. In February 2021, "Oshkosh announced it was investing $25 million in Texas-based Microvast, which it refers to as a 'global provider of next-generation battery technologies for commercial and specialty electric vehicles.'"

A few days later, "Oshkosh Defense won a contract to design and build what it calls it Next Generation Delivery Vehicle to the U.S. Postal Service." "The contract calls for 50,000 to 165,000 new USPS vehicles to be built over the next 10 years."

To the market, the storyline practically wrote itself: Oshkosh wins the USPS deal, Oshkosh backs Microvast, so Microvast must be the battery supplier. There was at least some foundation for that assumption. "Back in February 2021, Microvast had entered into a Joint Development Agreement (JDA) with Oshkosh for battery production. The agreement forms the foundation for further collaboration."

But it was never that clean. The USPS program wasn’t all-electric from day one. The mix of battery electric and internal combustion vehicles was still in flux. And Oshkosh had options—Microvast was a contender, not a lock.

Still, Microvast now had the elements Wall Street loves: a European footprint, an American factory plan, and a headline customer connection. And in the SPAC era, that was rocket fuel.

Because the SPAC boom was cresting, cleantech was getting priced like the future had already arrived—and Microvast was about to go public right into the middle of it.

V. The SPAC Boom and Tuscan Holdings Merger (2020–2021)

The SPAC mania of 2020–2021 was what happens when market euphoria meets financial engineering. Blank-check companies raised huge sums with a simple promise: we’ll find something transformative, merge with it, and you’ll own the future. EVs were the hottest corner of the market, and battery companies were the picks and shovels of the new gold rush.

Microvast was tailor-made for that moment. "Microvast, Inc., a leading global provider of next-generation battery technologies for commercial and specialty vehicles and Tuscan Holdings Corp. (Nasdaq: THCB), a publicly-traded special purpose acquisition company ('SPAC'), announced today that they have entered into a definitive merger agreement that will result in Microvast becoming a publicly listed company."

The headline numbers were attention-grabbing: "Battery maker Microvast Inc. will go public via a merger with blank-check company Tuscan Holdings Corp. in a deal that values the combined company at $3 billion. The companies will receive more than $800 million in cash when the deal closes, including a $540 million investment led by Oshkosh Corp., BlackRock Inc., Koch Strategic Platforms and InterPrivate."

And that PIPE list did real work. When Oshkosh and BlackRock show up, it reads like institutional validation, not just SPAC hype. "PIPE anchor investors include strategic partner Oshkosh Corporation as well as funds and accounts managed by BlackRock, Koch Strategic Platforms and InterPrivate."

By July 2021, the deal was through the vote and across the finish line. "The business combination was approved at a special meeting of stockholders on July 21, 2021, resulting in the combined company being renamed 'Microvast Holdings, Inc.', with its common stock and warrants to commence trading on the Nasdaq on July 26, 2021 under the ticker symbols 'MVST' and 'MVSTW'." And it brought a serious cash infusion. "Upon closing, the combined company received approximately $822 million in cash, comprised of approximately $282 million in cash held in trust by Tuscan and the proceeds of a $540 million PIPE."

To justify that kind of moment, the story had to be big. The investor deck didn’t whisper; it projected. "On page 20 of its slide presentation, Microvast projects that it will grow revenue quickly over the next 6 or 7 years. For example, from $101 million in 2020 in estimated sales, Microvast expects 2021 revenue will grow 128% to $230 million." The broader arc was clear: dramatic growth through 2025, turning Microvast from a proven niche player into a scaled global supplier.

The stock traded like the market wanted to believe it. MVST jumped as retail money—still riding the meme-stock wave—flooded into anything with “EV” or “battery” on the label. For a moment, Microvast looked like one of the SPAC winners.

Then the mood flipped.

In September 2021, short sellers came after the company. Microvast pushed back hard. "The allegations in the short seller J Capital Research Report are unfounded. The Report is based on errors of fact, misleading speculations, and malicious interpretations of events." But in public markets, the rebuttal rarely travels as far as the accusation. Once doubt sets in, it’s sticky.

The critiques focused on governance, related-party dealings, and questions about Chinese ties—and they kept coming. "Microvast Holdings Inc stock tumbled 7% following a scathing report from Grizzly Research that questioned the battery company's production capabilities and financial reporting. The short-seller report, titled 'Microvast's House of Lies,' claims the company is 'fabricating a significant part of its business and capabilities.'"

The result was brutal. The post-merger highs—above $14—gave way to single digits, and then lower. The SPAC premium vanished almost overnight. What should’ve been Microvast’s victory lap into the public markets became something else entirely: a company trying to scale manufacturing while simultaneously fighting for its credibility.

VI. The Trough of Sorrow: Execution Challenges & Market Reality (2021–2023)

After the SPAC, gravity returned—fast. Microvast missed the kind of projections that had helped sell the deal. The Tennessee factory slipped. Cash went out the door faster than the business could pull it in. And just as the company needed investor patience most, the market turned on anything that looked like “growth now, profits later.”

By 2024, the strain was visible on the ground in Clarksville. "Three years after announcing it would bring an EV battery plant in Clarksville with almost 300 jobs, Microvast this week terminated several employees as part of a reduction in force." It wasn’t just belt-tightening. It was an admission that Microvast had staffed up for a production ramp that wasn’t arriving on schedule.

On an earnings call, Yang Wu was blunt about why. "The challenging financing environment means that for the time being, we have got Clarksville as far as we can on our own balance sheet," Yang Wu said on an earnings call. "Accordingly, we are not currently anticipating material production volumes or revenues from our Clarksville facility."

And the math didn’t help. "The plant had been scheduled to open in the fourth quarter of 2023. During the call, then-Chief Financial Officer Craig Webster said the Clarksville plant is about halfway there, and another $150 million is needed to finish it." In other words: the “Made in America” plant existed, but not in the way Wall Street had priced it—more promise than output, and still demanding a fresh pile of capital to cross the finish line.

Then came the gut punch from Washington.

In October 2022, Microvast landed what looked like a game-changing win: a major DOE award tied to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. "On Oct. 19, 2022 the U.S. Department of Energy released 'Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Battery Materials Processing and Battery Manufacturing & Recycling Funding Opportunity Announcement', awarding US$2.8 billion to a number of public and private US companies. The company was awarded US$200 million to support development of a Thermally Stable Polyaramid Separator Manufacturing Plant in Clarksville, Tennessee, in partnership with General Motors."

But the celebration didn’t last. "In May 2023, the U.S. Department of Energy canceled the $200 million award to Microvast." The cancellation—attributed to concerns about Chinese government ties—didn’t just remove a funding source. It undercut the entire strategy of using U.S. policy momentum to finance a domestic buildout. And it rippled immediately into other plans. "A planned Microvast plant in Hopkinsville, Kentucky was halted as a result."

Microvast said it would pause that project. "Microvast announced that it will not proceed with its plan to build a factory in Hopkinsville, Kentucky—at least for now. Microvast had diligently pursued the establishment of the polyaramid separator manufacturing plant with the aim of expanding its operations, creating local jobs, and contributing to the growth of the Hopkinsville, KY community."

This was the double bind Microvast couldn’t escape. It was too China-adjacent for a political moment obsessed with “trusted supply chains,” but it also wasn’t some offshore phantom—Yang Wu himself was American. "Mr. Wu is a U.S. citizen and resides in the U.S" Still, the company’s manufacturing gravity remained in China, and that was the part regulators and critics kept circling.

The financial picture only intensified the existential questions. Losses mounted even as the company kept pushing to grow. "Net loss widened to $195.5 million in FY 2024 compared to $106.4 million in 2023." Along the way came the classic spiral for capital-intensive public companies: going-concern language in filings, equity raises to stay alive, and dilution that made long-term shareholders feel like they were paying for every additional month of runway.

All of this was happening inside an industry that rewards the biggest balance sheets and the lowest costs. EV demand cooled as rates rose and affordability tightened. Meanwhile the leaders kept extending their lead—CATL, for example, remained on top globally. "CATL continued to be the world's largest power battery manufacturer in 2024, with a 37.9 percent share above the 36.6 percent in 2023." Microvast wasn’t just competing with other startups. It was competing with industrial empires.

So what actually went wrong? Some of it was predictable: SPAC-era forecasts were almost always aggressive. But much of it was painfully concrete. Battery manufacturing is unforgiving—ramps take longer, quality demands are higher, and every delay burns cash. The market stopped funding money-losing growth. And geopolitics turned what had once been a cost advantage—deep Chinese operations—into a headline risk.

For Microvast, the dream of going public to fund a global expansion quickly turned into the public-market version of survival mode.

VII. The Pivot & Recent Developments: Survival Mode to Strategic Bets (2023–2025)

Against this backdrop of struggle, something unexpected began to happen: Microvast started to execute.

"Revenue increased 23.9% year over year to $379.8 million in FY 2024. Record quarterly revenue of $113.4 million, up 8.4% year over year in Q4 2024. Gross margin increased from 18.7% to 31.5%, a 12.8 percentage point improvement year over year."

The gross margin jump was the tell. In batteries, where pricing pressure is relentless and scale players squeeze everyone else, you don’t expand margins by accident. Moving from under 19% to over 31% suggested the business was getting tighter—better mix, better yields, better execution, or all three.

There was also finally some visibility. "Our backlog has grown to $401.3 million as regional demand for our technology continues to rapidly grow." That kind of backlog doesn’t guarantee anything, but it does change the conversation from “Where will revenue come from?” to “Can you deliver what you’ve sold?”

Then came Q1 2025—and it looked even more like a turn. "Record company Q1 revenue, increased 43.2% year over year to $116.5 million. Gross margin increased from 21.2% to 36.9%, a 15.7 percentage point improvement year over year."

And, for the first time as a public company, Microvast could point to profitability. "For the quarter we booked a net profit of $61.8 million and a positive adjusted EBITDA of $28.5 million, underscoring the increasing demand for our advanced battery solutions."

Management followed with a more confident posture for the year ahead. "For 2025, the Company is targeting a revenue growth of 18% to 25% year over year and revenue guidance of $450 million to $475 million."

So what changed?

For one, performance improved across geographies, with Europe leading and the Americas ramping. "By region, Microvast expects EMEA to continue its strong performance with over 20% year-over-year growth in 2025, while the Americas region is projected to grow by approximately 50%."

For another, Microvast stopped being just the LTO company. It broadened its chemistry toolkit to match more use cases and price points. "Microvast offers a broad range of cell chemistries, including lithium titanate oxide (LTO), lithium iron phosphate (LFP), nickel manganese cobalt version 1 (NMC-1), and nickel manganese cobalt version 2 (NMC-2)."

And it kept refreshing the product lineup. "The new lineup includes the introduction of silicon-based HnSO Cells, Lithium Titanate Oxide (LTO) Cells, and the third-generation MV-I Pack, offering an unprecedented combination of energy density, safety, and sustainability."

The most ambitious signal, though, was a swing at solid-state—one of the most hyped and most unforgiving frontiers in batteries. "In January 2025, Microvast announced a significant milestone in the development of its True All-Solid-State Battery (ASSB) technology. This advancement represents a key step forward in improving safety, energy density, and efficiency."

Microvast framed part of the advantage as architecture: "Microvast's ASSB utilizes a bipolar stacking architecture that enables internal series connections within a single battery cell. Traditional lithium-ion and semi solid-state batteries, constrained by the limitations of liquid electrolytes, typically operate at nominal voltages of 3.2V to 3.7V per cell." "This breakthrough allows a single cell to achieve dozens of volts or higher based on specific application needs. A voltage unattainable by any battery containing liquid electrolytes."

Of course, “solid-state milestone” is not the same thing as “solid-state product.” The industry is littered with great lab results that never survive manufacturing reality. Microvast pointed to early performance—"Early testing shows promising results with 99.89% Coulombic efficiency in 5-layer tests."—but also acknowledged what comes next: "Microvast is advancing to the next phase: the pilot production study. This phase represents a bold step into a new technological frontier, where our engineering team will apply innovative approaches to overcome unique manufacturing challenges." Translation: it’s still a bet.

Meanwhile, the physical manufacturing story—the part Wall Street had lost patience with—started to look less stuck. Microvast kept investing in capacity where it already had momentum. "In APAC, we are underway with our Huzhou Phase 3.2 expansion and anticipate to have this additional capacity online in the fourth quarter of 2025 to meet increasing customer demand."

And as the company tried to rebuild trust in the U.S., it leaned hard into a reframed identity: not a China-first battery maker attempting to land in America, but an American company expanding domestic footprint while keeping a global manufacturing base. "Following the spur of America's electrification, we decided to bring our innovative technology back to the United States. So far, Microvast has created more than 140 American jobs across Florida, Texas, Colorado, and Tennessee, with over 25% of our employees being military veterans or their spouses."

VIII. Playbook: What Microvast Teaches About Battery Businesses

If Microvast’s story feels messy, that’s because battery businesses are messy. But it does leave a handful of lessons that show up again and again for investors—and founders—trying to build anything physical at scale.

Timing matters more than being right. Microvast was early on the idea that fast charging would matter. The problem is that, in hardware, “early” can be a disadvantage. Years of R&D, pilot lines, and factory buildouts have to be financed long before demand is predictable. That gap between “the tech works” and “the market is ready” is where a lot of cleantech companies die—right about the future, broke in the present.

The SPAC trap is real. The SPAC merger handed Microvast roughly $822 million of fuel. It also strapped the company to public-market expectations, quarterly scrutiny, and a valuation narrative built on forecasts rather than delivered results. And once you’re public, you don’t just compete in factories—you compete in headlines. The short-seller attacks were part of that new arena. Staying private longer might have bought Microvast more time to ramp without being judged every 90 days.

Vertical integration is a double-edged sword. "Microvast's vertically integrated model allows for complete control over all phases of development, from R&D to manufacturing. This unique model allows for faster innovation, tailored customization, and exceptional quality." That control can be a real advantage when customers need specific pack designs and reliability is everything. But vertical integration also means you’re signing up for higher capex, more operational complexity, and more ways for a schedule slip to turn into a cash crisis. It’s a great strategy—if you can reach scale before the money runs out.

Niche strategies require discipline. Microvast largely avoided the passenger-car arena where CATL and BYD are monsters. Instead, it went after commercial vehicles and specialty applications where uptime and fast charging can justify a premium. That’s smart positioning. But niches also have ceilings. The challenge is turning “focused” into “dominant,” before larger players decide the niche is attractive and bring their cost advantage with them.

Geopolitics are unavoidable. A company founded by a Chinese immigrant, with major manufacturing roots in China, trying to build credibility as a U.S. supplier—Microvast sits right in the blast radius of rising U.S.-China tension. The DOE grant cancellation showed how quickly that can go from background noise to a business event. And it’s not the kind of risk you can engineer your way out of overnight.

Capital intensity is brutal. Battery manufacturing eats capital. "Another $150 million is needed to finish" the Clarksville plant. The painful reality is that every meaningful step forward—new lines, higher yield, more automation—usually requires spending before you earn. For smaller players, that can turn financing into the whole ballgame.

Execution trumps technology. Microvast’s early LTO differentiation was real, especially in safety, cycle life, and fast charge capability. "LTO cells are known for their extreme safety and long service life of up to 20,000 cycles." But technology spreads. Competitors improve. What starts as an edge becomes table stakes. In the end, the winners aren’t just the ones with clever chemistry—they’re the ones who can manufacture reliably, hit cost targets, deliver on time, and keep customers coming back.

IX. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of New Entrants: MODERATE-HIGH

Battery manufacturing is one of the most capital-intensive games on earth. Building a real gigafactory takes billions, plus years of process learning. But subsidies and industrial policy have changed the math. Governments around the world are effectively paying new entrants to show up, and China keeps minting new manufacturers with frightening speed. Layer in the possibility that a step-change like solid-state actually works at scale, and you have a market where the barriers are high—but not high enough to keep challengers out.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

The raw materials story is still a choke point. Lithium, nickel, and cobalt supply is concentrated, and the pricing can swing hard. The fact that lithium carbonate fell sharply in 2024 is a reminder that the “scarcity narrative” can flip quickly—but volatility cuts both ways, and manufacturers don’t get to choose when it hits. Microvast’s vertical integration, including moves into separator production, helps around the edges. It doesn’t eliminate exposure to the commodities underneath the whole industry.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH

The buyers here—OEMs and fleet operators—have all the leverage. Batteries are increasingly treated like a spec sheet and a price quote, with cost per kilowatt-hour setting the tone. There are switching costs once a battery is designed into a platform, validated, and warrantied, but big customers can multi-source, negotiate aggressively, and use competition as a weapon. In a world with too much capacity and too many hungry suppliers, the buyer usually wins.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

Substitution in batteries rarely means “no battery.” It means a different chemistry. LFP, NMC, and LTO each win in different corners, and sodium-ion keeps hovering as the next contender. On the edge of the map, hydrogen fuel cells still matter for certain heavy-duty use cases. And the thing that once made Microvast distinctive—fast charging—has been getting democratized. What used to be a differentiator is steadily turning into an expectation.

Industry Rivalry: VERY HIGH

This is the brutal one. "CATL's global installed capacity reached 339.3 GWh, with its market share further increased to 37.9%, widening the gap with the second place by nearly 21%." The top tier—CATL, BYD, LG Energy Solution—controls roughly two-thirds of the global market, and everyone else fights over what’s left. Korean players like Samsung SDI and SK On bring scale and deep OEM relationships. Chinese competitors bring cost advantages and policy tailwinds. The result is constant price pressure, fast technology iteration, and very little room for error.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: WEAK

Scale is the superpower in batteries, and Microvast doesn’t have it. CATL is operating at hundreds of gigawatt-hours of installed capacity; LG is far beyond Microvast’s footprint. Microvast’s Tennessee ambitions are in the single-digit gigawatt-hour range. Without massive volume, costs stay higher, and margin becomes harder to defend.

Network Effects: NONE

There’s no flywheel where each new customer makes the product more valuable to the next. A battery pack doesn’t become more useful because your competitor also bought one.

Counter-Positioning: WEAK-MODERATE

Microvast’s original counter-positioning was crisp: prioritize ultra-fast charging and long cycle life with LTO, even if energy density and cost per kWh weren’t best-in-class. That was a real wedge in buses and other high-utilization applications. But the wedge has narrowed. Competitors have pushed fast-charging across multiple chemistries. "CATL is building a multi-chemistry portfolio: low-cost LFP for mainstream vehicles, high-energy NMC for long-range models, sodium-ion for stationary storage, and the ultra-fast charge Shenxing pack aimed at five-minute top-ups." When the giants copy the feature, the differentiation fades.

Switching Costs: MODERATE

Batteries get designed into platforms, and once that happens, switching suppliers is painful: revalidation, supply chain changes, warranty risk, and engineering work. That’s real stickiness. But Microvast’s customer concentration means switching costs are a double-edged sword. A single lost relationship can move the entire business.

Branding: WEAK

This is B2B hardware. Brand matters, but it’s downstream of specs, reliability, and price. “Made in USA” could become a meaningful brand signal for customers focused on supply chain security, but it only works if the U.S. footprint is clearly scaled and dependable.

Cornered Resource: WEAK-MODERATE

Microvast has meaningful IP in fast-charging and thermal management. "As of September 30, 2021, we have been granted 369 patents and have 130 patent applications pending." That’s not nothing. But patents don’t automatically translate into a monopoly, and Microvast doesn’t control any exclusive resource like a unique material supply. The solid-state work could become a cornered resource if it proves commercially viable—if. For now, that’s potential, not protection.

Process Power: MODERATE (Developing)

If Microvast has a path to something moat-like, it’s here. Vertical integration can turn into process power if it produces better yields, faster iteration, and lower defect rates over time. And in theory, blending China’s manufacturing learning curve with credible U.S. production could be strategically valuable. But process power only counts once it’s repeatable, scaled, and clearly better than alternatives. Microvast is still in the “proving it” phase.

Verdict: Microvast doesn’t have a durable moat today. The best case is process power, reinforced by switching costs, if it can keep executing—especially on the Tennessee manufacturing ramp—and broaden from a few key relationships into a deeper customer base. The encouraging part is that execution has improved recently. The hard part is sustaining it in an industry that punishes every stumble.

X. Bull vs. Bear Case & Investment Framework

The Bull Case:

Fast-charging still matters—especially in the parts of the EV world that actually earn their keep all day. Buses, trucks, port equipment, and construction machinery don’t have the luxury of long charging stops. They need uptime, safety, and batteries that can take punishment. That’s exactly where Microvast’s LTO roots have always fit. "LTO cells are known for their extreme safety and long service life of up to 20,000 cycles and offer an energy density of 100Wh/kg. They are ideal for ultra-high-performance applications under difficult conditions."

The Tennessee footprint is more than a factory story—it’s a strategic option. As the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act push customers toward domestic content and trusted supply chains, “we can build in the U.S.” becomes a selling point, not a nice-to-have. And the flip side is just as important: companies that can only ship from China are running into higher friction, higher scrutiny, and sometimes outright barriers.

The financial picture has also started to look like something other than survival. "Record first quarter revenue of $116.5 million, compared to $81.4 million in Q1 2024, an increase of 43.2%. Gross margin increased to 36.9% from 21.2%." For a business that spent years fighting the narrative that it couldn’t execute, improving margins at the same time as growing revenue is the strongest counterargument it can offer.

There’s also a second act beyond buses. Energy storage systems are becoming one of the biggest demand pools for batteries, as utilities and companies chase backup power and grid services. Microvast has positioned its product line to play there. "Microvast's products are engineered to provide solutions to a variety of applications, including battery energy storage systems (BESS), commercial vehicles, construction machinery, and specialty vehicles."

And then there’s the moonshot: all-solid-state. If Microvast’s ASSB work ever becomes manufacturable at meaningful scale, it would be a legitimate leap in safety and performance, and not just a marketing bullet. "This advancement represents a key step forward in improving safety, energy density, and efficiency for critical applications."

Finally, there’s the simple public-market setup: expectations are low. The stock is nowhere near its SPAC-era highs. If Microvast can keep executing, the upside can be asymmetric because so much disappointment is already priced in.

The Bear Case:

The biggest bear argument is the simplest one: this is a scale game, and Microvast is fighting giants. CATL and other Chinese leaders win on integration, cost, and capacity. In most procurements, price per kilowatt-hour eventually dominates the conversation, and Microvast can’t manufacture its way into CATL-like economics overnight.

The U.S. factory story is still not fully proven. Clarksville has been delayed, it has required substantial capital, and making batteries competitively in the U.S. is hard even for far larger players. The DOE award cancellation wasn’t just a lost check—it was a reminder that geopolitics can hit Microvast directly, at the worst possible time.

Customer concentration is another existential risk. Microvast isn’t large enough to absorb the loss of one or two major customers without it showing up immediately in revenue, cash flow, and investor confidence. Backlog helps with visibility, but it doesn’t eliminate execution risk or the reality that big customers can squeeze suppliers.

Then there’s credibility. The SPAC-era projections created a high bar, and the misses that followed burned institutional investors. Even if operations improve, trust tends to rebuild slowly—and that can translate into a higher cost of capital and less flexibility when the next funding decision arrives.

EV adoption has also cooled from the straight-line extrapolations of 2021. Higher rates, affordability issues, and charging infrastructure gaps have all tempered demand. Commercial electrification has its own friction: fleet purchase cycles are long, and operators are conservative when uptime is on the line.

And the technical edge that once felt unique is getting crowded. "BYD's mine-to-pack integration is narrowing cost differentials in the mass-market segment, while LG Energy Solution's solid-state pilot lines and Panasonic's high-nickel 4680 ramp with Tesla are emerging threats at the premium end." Fast charging is spreading across chemistries and competitors. What used to be a wedge risks becoming table stakes.

Lastly, Microvast sits in the crosshairs of U.S.-China tension in both directions. It can face skepticism in the U.S. because of China-linked manufacturing history, while also operating in an environment where being perceived as foreign-owned can create complications in China. That’s not a quarterly issue—it’s a structural one.

Key Metrics to Watch:

For investors tracking Microvast’s progress, three KPIs matter most:

-

Gross margin trajectory — The move from 18.7% to 31.5% in 2024 and 36.9% in Q1 2025 signals improving execution. The question now is whether margins can stay healthy as volumes scale and pricing pressure returns.

-

Revenue growth by region — Especially EMEA and the Americas. A business that becomes less dependent on any single geography is a business with fewer single points of failure.

-

Cash burn or cash generation — Recent positive operating cash flow is encouraging, but consistency is everything. Sustained cash generation lowers going-concern risk and reduces the odds of dilution.

XI. Epilogue: The Future of Microvast & The Battery Wars

So where does Microvast sit in the battery landscape today? It’s a survivor, no question. It’s also, by global-share standards, an underdog. A dark horse? Only if the next few years break its way.

What Microvast has proven—painfully, publicly—is that it can take hits that would kill most hardware companies and keep shipping. Yang Wu has led it for nearly two decades, through subsidy booms, China-market consolidation, the SPAC bubble, short-seller fire, and a U.S. buildout that repeatedly ran into the reality of capital. In batteries, where timelines stretch and factory learning curves are brutal, that kind of persistence isn’t a personality trait. It’s a requirement.

But the economics don’t care about perseverance. Batteries are a scale game, and scale keeps concentrating. "CATL's market share further increased to 37.9%, widening the gap with the second place by nearly 21%. This marks the fourth consecutive year that CATL has been the only battery manufacturer in the world to capture more than 30% of the market share." And as the giants get bigger, differentiation gets harder to hold. Features that used to be a wedge—like fast charging—have a way of turning into table stakes.

If Microvast thrives from here, it likely does it through one of a few paths. It could become an acquisition target, especially for a larger player that wants a foothold in U.S. manufacturing or a portfolio of fast-charging know-how. It could lean into being a specialist—winning specific corners like port equipment, specialty vehicles, or other high-uptime applications where fast-charging and durability actually change the economics for customers. Or the company’s solid-state effort could become something real. That’s the high-upside path, but it’s also the one with the longest odds, because “promising milestone” and “manufactured at scale” are very different sentences.

Zoom out, and the story gets even more interesting. The push for battery independence in the U.S. and Europe is creating a new kind of demand: not just for cells, but for trusted supply chains and domestic production. The opportunity is obvious. The tension for Microvast is, too. Can it convincingly position itself as part of that local-manufacturing answer, or will it stay stuck in the uncomfortable middle—too small to dictate terms, and too China-connected to be an easy political fit?

In that sense, Microvast’s story is the story of hardware startups everywhere: real technology, uneven execution, and an industry that punishes delays with dilution and disbelief. The ending isn’t written. The recent numbers suggest Microvast might be finding its footing. But in a world where the leader’s R&D budget can dwarf a small competitor’s entire market value, simply staying alive is only the first step.

For long-term investors, Microvast is still a bet—on execution continuing to improve, on a niche staying defensible, and on the U.S. manufacturing strategy ultimately paying off. Those aren’t certainties. They’re conditions.

Sometimes the companies that make it through the cleantech bloodbath come out tougher. Sometimes founders who refuse to quit build something durable. And sometimes a bet that looks early in year five looks obvious by year fifteen.

Yang Wu’s fast-charging thesis from 2006 may still be vindicated. Or it may not. As always in batteries, it comes down to the least glamorous variable of all: execution.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music