Murphy USA: The Capital Allocation Engine Behind the Pump

I. Introduction: The "Boring" Compounder

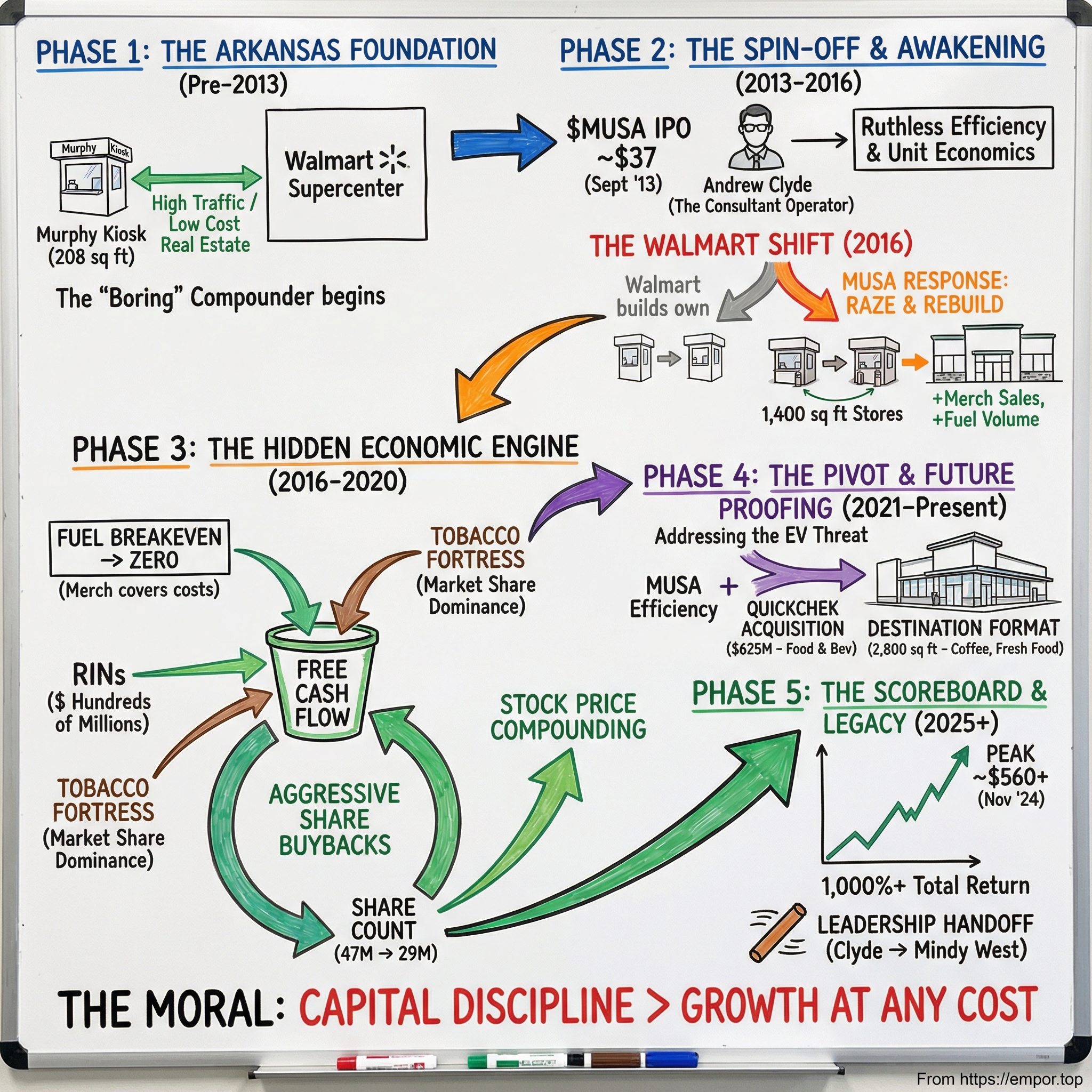

Picture this: a 208-square-foot kiosk in a Walmart parking lot in Arkansas. No baristas. No artisanal sandwiches. No EV chargers glowing under designer canopies. Just a handful of pumps, a register, and a cigarette case behind glass. This is Murphy USA—and over the last decade, it has been one of the most effective wealth-creation machines in American retail.

Since its 2013 spin-off from Murphy Oil, Murphy USA has delivered total shareholder returns north of 1,000%, handily outpacing the S&P 500 over the same stretch. While investors piled into high-growth SaaS, streaming, and electric vehicles, this unglamorous chain kept doing the unthinkable: quietly compounding.

And it did it while selling two categories that are supposedly going away: gasoline and cigarettes.

So what’s going on here? How does a company built around tiny boxes in big-box parking lots outperform the NASDAQ? The answer isn’t a secret technology or a viral consumer brand. It’s three things working together: a real estate position you can’t easily recreate, an almost consulting-like obsession with operational efficiency, and a capital allocation discipline that turns a “boring” retailer into a compounding machine.

At its core, Murphy USA markets retail motor fuel and convenience merchandise. It runs stores under the Murphy USA, Murphy Express, and QuickChek brands, plus some non-fuel convenience stores, with a footprint concentrated across the Southeast, Southwest, and Midwest.

But the real story lives in the paradox. In an industry where scale often leads to bloat, Murphy built a fortress out of minimalism. In a sector where cash flow gets burned on flashy new formats and marginal locations, Murphy used its cash to shrink its share count and sharpen its economics. In a market obsessed with growth at any cost, Murphy got very, very good at profitable decline.

This is the story of how a sleepy Arkansas spin-off became the “last man standing” in American convenience retail—and what happens when you apply real capital discipline to a business almost everyone else has written off.

II. Pre-History: The Arkansas Connection & The Walmart Handshake (1996–2013)

To understand Murphy USA, you first have to understand Murphy Oil. And to understand Murphy Oil, you have to start in El Dorado, Arkansas.

El Dorado was shaped by oil. The boom that swept through town in the 1920s brought people and money fast—and then it faded just as quickly. But the industry didn’t disappear, and Murphy didn’t either. Over the decades, Murphy Oil grew into one of the state’s signature companies, part of the same Arkansas business orbit as Walmart in Bentonville, Tyson Foods in Springdale, and J.B. Hunt in Lowell. For years, Murphy family members and executives were fixtures in the state’s business and political circles.

Murphy Oil was founded in 1944 as CH Murphy & Co by Charles H. Murphy Sr., and incorporated in Louisiana in 1950. By the mid-1990s, it was a serious exploration and production company with international reach—Malaysia, Congo, the Gulf of Mexico. But it also had something else on the side: an odd little retail effort that didn’t fit neatly inside an upstream oil company.

Then came the insight that changed everything. In 1996, Murphy wanted a way to sell gasoline directly to consumers—cheap, convenient, high-volume. The hard part of that business isn’t the fuel; it’s the locations. You can have the best supply contract in the world, but if you’re on the wrong corner, you’re dead.

Walmart had the opposite problem. Supercenters were becoming the center of gravity for suburban shopping, and Walmart had learned something simple: putting fuel in front of a store increased traffic. But gasoline margins were thin, and running fuel operations wasn’t what Bentonville wanted to spend its time on. Walmart wanted a low-price gasoline and tobacco offering for its customers—without having to build the machine to operate it.

Murphy saw the trade immediately. Walmart could solve the real estate and traffic problem in one move. Murphy could solve the fuel-and-tobacco execution problem and do it with a retailer’s obsession for pennies. So the two companies partnered, and the core playbook snapped into place: Murphy would build tiny, efficient kiosks on or near Walmart Supercenter lots, capturing massive traffic without the usual site-selection slog.

The deals were straightforward, and they mattered. Walmart sold Murphy small parcels on or adjacent to Supercenter properties. There were no royalties, no ongoing cents-per-gallon payments, and no traditional lease structure on many sites. Over time, Murphy ended up owning a large portion of its footprint—today, it owns 77% of its real estate.

Not every site looked identical. Sometimes Walmart bought extra parcels around a Supercenter and sold them to Murphy. Sometimes it carved out a section of parking lot and assigned it over. If Walmart itself was leasing a site, it could lease space onward to Murphy. And when Walmart couldn’t offer a spot, Murphy went outside the ecosystem—buying or leasing outlots from third parties. Those stations weren’t tied into the Walmart discount fuel program, so Murphy branded them differently: Murphy Express instead of Murphy USA.

What resulted was a retail machine that looked almost unfair. Murphy didn’t have to hunt for corners or win zoning battles block by block. It didn’t have to guess where traffic would be. It just built next to the highest-traffic box in town, over and over again.

The partnership began in 1996 and became the backbone of the network: 1,012 of 1,155 stations were tied to Walmart. By 2012, Murphy had built more than a thousand of them, at a pace that worked out to roughly 125 stores per year.

And here’s the lasting consequence: a structural advantage that most competitors simply couldn’t copy in those markets. Not 7-Eleven. Not Sheetz. Not the local independent. In those Walmart-heavy geographies, the Walmart customer became Murphy’s customer—and Murphy got that demand without paying for it in the way everyone else pays for demand: through expensive real estate and constant marketing.

This Arkansas handshake set the stage for everything that followed. But back at Murphy Oil, that created a new problem: the retail business was becoming a gem inside a company Wall Street valued for drilling, not selling coffee and cigarettes. And eventually, that mismatch would force a decision.

III. Inflection Point 1: The Spin-Off & The "Raze and Rebuild" (2013–2016)

In the fall of 2012, Murphy Oil’s board made the call that would finally make the retail business make sense to public-market investors: spin it out.

The plan was clean and shareholder-friendly. Murphy Oil would separate its U.S. downstream subsidiary, Murphy Oil USA, Inc., into a standalone, separately traded company. At the same time, the board authorized a $2.50 per share special dividend, totaling about $500 million, and a share repurchase program of up to $1 billion.

Chairman Claiborne Deming framed it as a classic “two great businesses trapped in one structure” problem: separating them would let each pursue its own path—Murphy Oil as a pure-play exploration and production company, and Murphy USA as a focused fuel-and-convenience retailer with more than 1,100 outlets.

On August 30, 2013, the split became real. Murphy Oil completed the spin-off, creating Murphy USA Inc. Murphy USA began regular-way trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker “MUSA” on September 3, 2013. The stock opened around $37.30 per share and traded up modestly during the day.

But the market mechanics were the least interesting part. The bigger change was managerial and cultural. The new Murphy USA would be run by an outsider.

That outsider was Andrew Clyde, and he didn’t come up through store ops, merchandising, or site selection. He came out of Booz & Company, where he’d spent about two decades advising energy companies—leading the Dallas office and the North American Energy Practice, serving clients across more than 30 countries. He brought an operator’s industry familiarity, but through a consultant’s lens: structure, incentives, unit economics, and ruthless prioritization.

Clyde’s background also had an Arkansas thread running through it. His family moved to El Dorado when he was young, and he grew up around the ecosystem that produced Murphy Oil’s leadership ranks. His grandfather, Robert Aycock, sold fuels for PanAm Southern across south Arkansas and northern Louisiana. Clyde spent summers and winter breaks riding along on customer calls—an early crash course in what he called “Personal Service 101.”

When Clyde took the job in January 2013, he had to earn trust inside a team that had been running this model for years. By his own telling, his habit of asking a lot of questions took some adjustment. But he leaned into it: when you ask a store manager how something really works—or how it could work better—you’re also signaling that their experience matters.

At the time of the spin-off, Murphy USA was already big. The new company had 1,179 retail outlets across 23 states, with plans to exceed 1,200 by year-end. It represented roughly 47% of Murphy Oil’s revenue base, which had topped $28.6 billion in 2012. Projections for 2013 had Murphy USA easily clearing $19 billion in sales across fuel, merchandise, and other transactions. About 77% of the locations were those famously tiny 208-square-foot kiosks, collectively handling around 1.6 million transactions a day.

And those kiosks were the point. They were almost comically small—just enough room for a register, tobacco behind glass, and a tight assortment of snacks. Most didn’t even have restrooms. They weren’t designed to be destinations. They were designed to be efficient.

Then came the moment that forced Murphy USA to stop being “Walmart’s gas station” and start becoming a company with its own destiny.

In the first quarter of 2016, Murphy USA announced a change in its relationship with Walmart as Walmart began opening its own in-house gas stations and convenience stores. The alliance that had powered Murphy’s growth since 1996 wasn’t being ripped up overnight, but the growth engine—new builds on Walmart pads—was no longer guaranteed.

It was a major shift. More than 1,000 of Murphy’s roughly 1,300 stations were attached to or near Walmart stores, and Murphy had sought to extend that relationship. But Walmart’s decision was Walmart’s decision.

Clyde didn’t pretend it was anything else. He said the company had been considering the possibility of “no new locations with Walmart” for years and had prepared. “This was a Walmart decision,” he said. “In a sense they decided to not work with Murphy USA anymore. We were not caught by surprise by this. We anticipated this move by Walmart.”

The response was what separates a dependent business from an independent one: Murphy didn’t panic. It accelerated.

Murphy USA confirmed a strategic shift that gave it more flexibility to develop sites independently. The board authorized a new allocation of capital to pursue additional independent growth opportunities—and, crucially, to buy back stock. It approved up to $500 million across those two programs through December 31, 2017. Clyde put the message plainly: since the spin, Murphy USA had positioned itself to deliver organic growth and shareholder returns with or without more Walmart store locations.

And that’s where “raze and rebuild” entered the story as something more than a construction program. It became a declaration of intent.

The old 208-square-foot kiosk format had been brilliant for fuel throughput and low operating costs—but it capped what Murphy could become. So the company started taking those kiosks down and replacing them with real convenience stores. The new-to-industry stores were planned at about 2,800 square feet. Murphy also pursued raze-and-rebuild projects that converted existing kiosks into a 1,400 square-foot “small store” format, still often in Walmart parking lots, but no longer limited to a glass box and a cigarette rack.

When those rebuilt stores came back online, the early results reinforced the logic. Murphy opened three new stores and brought 10 raze-and-rebuilds back into service as 1,400 square-foot convenience stores. Clyde said they were performing at a higher level right out of the gate, helped by improved opening procedures and sharper pricing tactics. The 2018 and 2019 build classes were delivering fuel volumes about 25% higher than the network average, and raze-and-rebuilds were showing a 15% lift in fuel volumes along with about 30% higher merchandise sales.

What was emerging was the Murphy machine in its mature form: high-volume fuel, thin margins, relentless execution—and then the real profit, coming from inside the box. Fuel brought the traffic. Tobacco and merchandise captured the margin. That cash funded share buybacks. And the buybacks, over time, turned a “boring” retailer into a compounding engine—without needing the company to chase growth for growth’s sake.

IV. The Hidden Economics: RINs, Tobacco, and Capital Allocation (2016–2020)

If you only look at Murphy USA as “gas stations and cigarettes,” you miss the weirdest, most lucrative line item in the whole story: RINs.

Renewable Identification Numbers—RINs—are essentially environmental credits created under the Renewable Fuel Standard, a federal program that requires a certain amount of renewable fuel to be blended into the U.S. transportation fuel supply. Each year, the EPA sets the targets, and the companies on the hook—generally refiners and importers of petroleum-based gasoline and diesel—have to prove they met their obligation.

The way the system works is almost like a receipt. When renewable fuel gets blended into conventional fuel, the associated RIN can be separated from the physical gallon and traded. Those separated RINs end up in a market where obligated parties buy them to satisfy compliance, and once used, a RIN gets retired.

Here’s the punchline: Murphy wasn’t one of the obligated parties. It was a blender. That meant it could generate and sell RINs into the market. In 2016, Murphy USA made $181.1 million selling them.

For a “boring” retailer, that’s not pocket change—that’s a serious earnings lever. And it showed up at exactly the right time: management was clear-eyed that RIN economics could swing, and they treated the windfall accordingly. Rather than building an empire on a regulatory credit, they used the extra cash to repurchase shares when they believed the stock was attractive.

If RINs were the hidden line item, tobacco was the open secret—and Murphy turned it into a fortress.

They ran tobacco the same way they ran fuel: high-volume, sharp pricing, relentless execution. Murphy sold about four times more tobacco per store than competitors, and cartons made up roughly half to 60% of tobacco sales. Even as smoking rates fell nationally, Murphy’s core customer—value-conscious rural and suburban shoppers—kept showing up. From 2021 through 2024, cigarette volume in the Murphy network was about flat, while the broader market fell by roughly 20%.

Clyde described it as its own destination trip. “Our multi-pack and carton cigarette offers have become a destination trip for consumers,” he said, emphasizing that the tobacco business was “entirely uncorrelated with fuel traffic.”

And Murphy wasn’t just holding share; it was taking it. “We are continuing to grow our market share in combustible products eclipsing 20% share in Murphy markets,” Clyde said. In the fast-growing oral nicotine category, Murphy was seeing double-digit growth in sales and margin.

But the most distinctive part of the Murphy playbook wasn’t RINs or tobacco. It was what they did with the cash those businesses threw off.

They bought themselves back.

Between 2013 and Q3 2020, share count fell from about 47 million to about 29 million. Since the 2013 spin-off, the company repurchased more than 29 million shares—about 63% of the original shares outstanding—at an average price of $139 per share.

That’s not “returning some capital.” That’s corporate self-cannibalization at scale: retire nearly two-thirds of the company while continuing to grow the business.

And underneath it all was a metric that explains why Murphy could keep winning on price without bleeding out: fuel breakeven.

Murphy defined fuel breakeven as merchandise gross profit minus all site operating costs, minus overhead costs, divided by retail gallons. In plain English, it asked: after everything the store makes inside the box and after all costs, how many cents per gallon do we need from fuel just to break even?

There are only three ways to improve it: sell more merchandise profitably, cut costs, or push more gallons through the pumps. Murphy worked all three. In 2013, fuel breakeven was 3.5 cents. By “today,” it had reached zero.

That’s the holy grail in a penny-difference business. If merchandise covers the overhead, Murphy doesn’t need fuel profit to stay alive. Every incremental gallon becomes upside. And that changes the competitive game: Murphy can price fuel lower than almost anyone and still be fine, because the store economics—not the pump margin—carry the whole machine.

This is what made Murphy USA so hard to compete with. The kiosks brought the traffic. Tobacco and merchandise captured the margin. RINs added a hidden boost when the market allowed it. And the capital allocation—especially the buybacks—turned all of it into compounding.

V. Inflection Point 2: The QuickChek Acquisition (2021)

Inside Murphy USA’s headquarters, executives were staring down an uncomfortable question: what happens when gasoline demand peaks?

The kiosk model had been perfect for the 2010s. But the long-term forces were hard to ignore. Electric vehicles were gaining traction, especially in coastal markets. Cigarette consumption kept drifting down. And the convenience store winners were increasingly playing a different game—fresh food, coffee, and beverages, not just fuel and cartons behind glass.

Chains like Wawa and Sheetz showed what that future looked like: stores that people actually chose for lunch, not just because the pump price was a penny cheaper. Those operators built loyalty with made-to-order food and strong beverage programs, and then used fuel as an add-on—not the main event. Murphy’s tiny kiosk footprint simply couldn’t compete on that dimension.

Murphy’s answer arrived in December 2020. The company announced it would acquire QuickChek Corporation in an all-cash deal for $645 million, including expected tax benefits valued at $20 million, for a net after-tax purchase price of $625 million. QuickChek was a family-owned chain with 157 stores concentrated in central and northern New Jersey and the New York metro area.

QuickChek had deep roots. It traced back to Durling Farms, a dairy delivery business that began in 1888. In 1967, the family opened the first QuickChek store in Dunellen, New Jersey, and over time built a brand known for service and, crucially, food and drink.

In many ways, QuickChek was the mirror image of Murphy USA. Instead of a kiosk optimized for speed and cost, QuickChek leaned into larger-format stores—around 5,500 square feet in its newer prototype—designed around open layouts, wide aisles, and prominent food stations. The pitch wasn’t “get in and get out.” It was “come here because the coffee and food are worth it.”

The economics reflected that. QuickChek generated roughly $3.5 million per store per year in merchandise sales, with combined merchandise margins around 38%. Food and beverage made up more than half of the merchandise mix. The stores also moved real fuel volume—about 3.8 million gallons per store per year—and the chain had a track record of same-store-sales growth and a development pipeline to keep expanding within its footprint.

Andrew Clyde framed the deal as an acceleration of a strategy Murphy had already telegraphed. “In October we outlined an updated capital allocation strategy and committed to improving our food-and-beverage offer at existing and future sites,” he said when announcing the acquisition. “This transaction greatly accelerates those efforts and benefits and is expected to provide reverse synergies across our network, while enhancing future returns on new stores.” He also highlighted the human scale of what was being acquired: “We are extremely excited to welcome nearly 5,000 QuickChek employees to the Murphy USA family as we begin our joint value-creation journey together.”

QuickChek’s leadership emphasized continuity. CEO and Chairman Dean Durling pointed to shared cultural roots—family heritage and a people-first mindset—and said he was excited that Murphy committed to honoring QuickChek’s legacy, preserving the brand, and learning from its model.

When the acquisition closed, Murphy USA’s footprint changed overnight. It added 157 high-performing stores in the Northeast and pushed total store count to more than 1,650.

This wasn’t a cheap bet, but it was a deliberate one. The net investment of $625 million valued the business at 13.2x QuickChek’s estimated last-twelve-months October 2020 adjusted EBITDA of $47 million. Murphy expected annual run-rate synergies of $28 million by year three. Including those synergies and the tax benefits, management said the effective multiple dropped to about 8.3x.

And the integration started paying off quickly. On the fourth-quarter and full-year 2021 earnings call, Clyde called QuickChek “a strategic acquisition with a very focused purpose,” and said the company surpassed its year-one synergy target even while identifying additional opportunities beyond the $28 million plan.

You could see the shift show up in the mix. Food and beverage contribution margin rose to 15.2% of total merchandise contribution dollars in fourth-quarter 2021, up from 0.8% in fourth-quarter 2020.

That’s the real point: Murphy didn’t buy QuickChek just to buy growth. It bought a capability it didn’t have. If the long-term world is one where fuel matters less, Murphy needed to get great at selling the things that still bring customers through the door—coffee, sandwiches, and higher-margin beverages. QuickChek didn’t just offer that playbook. It gave Murphy a live operating system to learn from.

VI. Strategic Analysis: The 7 Powers & 5 Forces

To really understand Murphy USA, you need a couple of frameworks that explain why a company selling commodities can still earn returns that feel… non-commodity.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 Powers Analysis:

Cornered Resource: Murphy’s Walmart-pad real estate is the closest thing convenience retail has to a truly cornered resource. In the early days, Walmart sold Murphy parcels on or adjacent to Supercenter parking lots outright—no royalties, no leases, no cents-per-gallon toll. That combination of traffic and cost structure simply isn’t available anymore. Once Walmart decided to build more of its own fuel sites, the window closed for good. Those 1,100-plus Murphy locations tied to Walmart are a legacy asset that can’t be recreated, no matter how much capital a competitor throws at the problem.

Scale Economies: Murphy benefits from scale in a place most people don’t think to look: fuel procurement. They have a dedicated team whose job is to constantly hunt for the best way to buy the gallons the network needs—something mom-and-pop operators just can’t do. That flexibility lets Murphy take advantage of dislocations in the gasoline market. And because retail fuel pricing is effectively set by higher-cost operators, Murphy’s lower breakeven means it can live comfortably at price points that stress everyone else, and still generate better fuel margins than most of the field.

Counter-Positioning: Murphy’s entire model is a deliberate bet against the branded majors. Shell and Exxon don’t just sell fuel—they sell the logo, the marketing, the franchise ecosystem. That brand investment has to get paid for somewhere, and it shows up in the economics at the pump. Murphy doesn’t pay for that. It competes on price, pulling in the consumer who just wants cheap gas. Branded operators can try to match Murphy, but if they do it for long, they start breaking their own model.

Porter's Five Forces Analysis:

Threat of Substitutes (High but Managed): Electric vehicles are the big, obvious substitute. EV sales in the U.S. grew from just over half a million in 2020 to about 1.6 million in 2024, and were projected to keep climbing into 2025. But Murphy’s footprint matters here: it’s concentrated in the rural South and Midwest, where adoption has been slower and charging infrastructure is thinner. EVs are real—but they arrive unevenly, and Murphy’s map buys it time.

Supplier Power (Low): Fuel is a fungible commodity, and Murphy isn’t locked into a branded supply arrangement. It sources unbranded fuel and blends in-house, which also allows it to capture economics like the RIN opportunity that many branded operators effectively give up. With lots of available supply options, no single supplier can dictate terms.

Buyer Power (High): The customer has all the leverage at the pump. People will literally turn left for a penny. Murphy’s response isn’t to fight that reality with marketing—it’s to lean into it: win on fuel price, then make the real money inside the store.

Industry Rivalry (Intense but Thinning): This is a brutally competitive industry, but it’s also one where the weakest players are increasingly under pressure. The sector is still fragmented: in 2024 the U.S. had 152,396 convenience stores, and roughly 63% were single-store operators. Only a small number of chains have real national scale, while tens of thousands of operators run ten or fewer locations. With expenses rising and labor a constant challenge, many retailers are either trying to buy scale or choosing to sell and exit—and industry experts didn’t expect that consolidation trend to slow in 2026.

Murphy’s bet is the “melting ice cube” thesis: even if total demand doesn’t grow, volume will consolidate to the lowest-cost operator as marginal stations shut down. Murphy doesn’t need the category to expand. It needs competitors to quit.

Threat of New Entrants (Low): Starting a new gas station from scratch is expensive, slow, and increasingly constrained by zoning and permitting. You need prime real estate, you need approvals, and you need enough capital to survive a price war with incumbents. And in Murphy’s case, the best locations—those Walmart pads—aren’t just expensive. They’re effectively unavailable.

VII. The Bull vs. Bear Case: The Energy Transition

The Bear Case:

The terminal value problem hangs over any analysis of Murphy USA. If U.S. gasoline demand peaks around 2030 and then slides, what are these assets worth when the core product is in structural decline?

The EV curve is the obvious catalyst. EV sales rose from just over 500,000 in 2020 to about 1.6 million in 2024. And if the U.S. really does move toward roughly 33 million EVs on the road by 2030, the country would need a massive buildout—on the order of millions of public charging ports—to make that practical at scale.

Then there’s the competitive question. Even if Murphy can be the last efficient fuel retailer, can it become a real food-and-beverage destination in a world where the best convenience chains look more like quick-service restaurants with gas pumps? Buc-ee’s and Wawa aren’t winning because they’re a penny cheaper on regular unleaded. They’re winning because customers actually want to stop there. Murphy’s move to acquire QuickChek gives it a credible path to build those capabilities, but the execution risk is real. Food service is a different business: supply chain complexity, food safety, staffing, training, and kitchen operations—all of it has to work every day, in every store.

And finally, the Walmart question never fully goes away. As of February 21, 2024, Murphy USA operated about 1,700 retail fueling stations across 27 states, with over 1,100 sites located near Walmart stores. If Walmart shifts strategy—closing Supercenters, leaning into smaller formats, or simply seeing traffic soften—Murphy’s original structural advantage gets less powerful.

The Bull Case:

The bull case starts with a simple bet: consolidation. The convenience store industry is still packed with small chains and single-store operators, and the economics get harder as labor, compliance, and complexity rise. As Rob Gallo, chief strategy officer for c-store consultancy Impact 21, put it: “There still remains a large number of chains out there in the 10 to 100 store range that, depending on what their long-term strategy is—especially if they're family-owned businesses—may decide that they want to get out. It’s just more difficult to manage the chain if you're a small operator compared to the big guys, especially with the consolidation going on across the country.”

In a declining demand environment, that matters even more. When the category shrinks, the highest-cost operators don’t muddle through—they close. The “melting ice cube” dynamic Murphy is betting on is brutal, but clear: volume consolidates to the lowest-cost survivor. With the lowest breakeven in the industry, Murphy can keep pricing to win gallons at levels that would break competitors.

The other pillar of the bull case is the format shift. Murphy’s plan has been to keep expanding with larger, higher-merchandise stores while upgrading the legacy kiosk base—building up to 50 new-to-industry locations per year beginning in 2021 in the 2,800-square-foot format, and converting about 25 kiosks per year into its 1,400-square-foot format. Clyde framed the ambition plainly: “We have invested in our new store pipeline in preparation for accelerating our new store growth with a goal of putting up to 50 highly productive 2,800 square foot stores into service in 2025.”

And then there’s the part the market tends to underestimate: the capital allocation engine. Even if fuel demand slowly declines, Murphy can still generate significant cash—and that cash can keep shrinking the share count, concentrating the remaining economics into fewer shares. Murphy USA approved a $2 billion share repurchase program running through December 31, 2030, set to begin after finishing its existing $1.5 billion plan (which had $337 million remaining).

Key Metrics to Track:

For investors following Murphy USA, two metrics matter above all else:

-

Fuel Breakeven (cents per gallon): This is the “how low can they go” number—how much fuel margin per gallon Murphy needs after merchandise profits to cover operating costs and overhead. At zero or below, Murphy can win on price without needing fuel to carry the store.

-

Same-Store Merchandise Contribution Growth: This is the scoreboard for the pivot. If inside-the-store contribution is rising, the food-and-beverage transformation is working—and Murphy has a path to offset pressure from fuel over time.

VIII. Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

Murphy USA is a reminder that the most durable playbooks often show up in the least glamorous places. Strip away the pumps and the cigarette racks, and what you’re left with is a set of repeatable strategic principles—useful whether you’re building a business, running one, or investing in one.

Lesson 1: Agility in Boring Industries

The default assumption is that innovation belongs to software, not gas stations. Murphy proved otherwise. It didn’t invent a new product or a new technology. It innovated on the things that actually determine survival in a commodity business: cost structure, unit economics, and ruthless capital discipline.

The takeaway is almost contrarian: “boring” industries can produce extraordinary returns precisely because a lot of smart capital ignores them. When the spotlight is elsewhere, execution matters more—and the best operators can compound quietly for a long time.

Lesson 2: The "Attach Rate" Model

Murphy built the business by latching onto Walmart’s ecosystem: piggybacking on Walmart traffic, Walmart-adjacent real estate, and Walmart’s value-oriented customer. Then, when Walmart stopped being a guaranteed growth partner, Murphy didn’t collapse—it adapted, expanded beyond the parking lot, and built capabilities that weren’t dependent on the relationship.

This “attach, learn, and decouple” strategy is more reproducible than it looks. The key is that you have to make the host better. Murphy wasn’t just extracting value; it helped Walmart reinforce its low-price perception and drove incremental trips. That’s why the partnership lasted as long as it did—and why Murphy had the foundation to stand on its own when the terms changed.

Lesson 3: Capital Allocation as Strategy

Clyde’s consulting habit—asking the unglamorous questions, over and over—showed up most clearly in how Murphy treated cash. Over roughly a decade as a standalone company, Murphy USA grew earnings dramatically and delivered outsized shareholder returns.

But the bigger point isn’t the exact percentage. It’s the decision to treat capital allocation as the strategy, not a footnote to it.

Most retail CEOs are rewarded for building empires: expanding footprints, chasing adjacent categories, rolling out shiny new initiatives. Murphy took a different path. It bought back stock aggressively, especially when management believed the market was mispricing the business. In a steady cash-flow model, shrinking the denominator can be more powerful than chasing growth that dilutes returns. Sometimes the best expansion plan is knowing when not to expand.

Lesson 4: Operational Density

Murphy also wins through something that sounds mundane but compounds: clustering. Dense store networks mean fuel deliveries can be routed efficiently, field leaders can cover more locations in a day, and training and execution standards scale faster. Costs drop, reliability improves, and the whole system gets harder for a scattered competitor to match.

In a business where pennies matter, operational density turns “small advantages” into a permanent edge.

IX. Epilogue & The Future

In October 2025, Murphy USA announced a leadership transition that marked the end of an era. Mindy K. West was named the next Chief Executive Officer, set to become one of the few women leading a Fortune 500 energy company. She would succeed Andrew Clyde, who had been Murphy USA’s President and CEO from the 2013 spin-off onward—the architect of the company’s consulting-driven, capital-allocation-first playbook.

The handoff was immediate and orderly. Murphy said West, then the company’s chief operating officer, would step into the role of president right away and take over as CEO on January 1, 2026. On that same date, she would also join the board of directors. And in a move that felt like Murphy staying Murphy to the very end of Clyde’s tenure, the board approved a new share repurchase authorization of up to $2 billion, running through December 31, 2030. That program would begin once the company finished its existing $1.5 billion authorization, which still had $337 million remaining.

West’s story is, in many ways, the Murphy story: long tenure, deep institutional knowledge, and a steady climb through the engine room of the business. She joined Murphy Oil in 1996 and held roles across finance, HR, and planning. When the retail business spun out in 2013, she became Murphy USA’s executive vice president, CFO, and treasurer. In 2017, she added fuels leadership responsibilities. And in February 2024, as part of the board’s succession planning, she was elevated to COO—an explicit signal that the company was grooming an operator who already understood the details behind Murphy’s returns.

The scoreboard for the last decade was hard to miss. Murphy USA hit an all-time high on November 27, 2024, closing at $561.08. From a spin-off price around $37.30 to a peak above $560, it was the kind of return you expect from a legendary tech story—except this one was built in Walmart parking lots, selling gasoline and cigarettes.

Of course, the horizon still brings real challenges. EV adoption is expected to accelerate over time, even if Murphy’s rural-heavy footprint buys it breathing room. The push for EVs during the previous administration had slowed, and the broader market learned quickly that charging technology and infrastructure hadn’t caught up to the ambitions being advertised. With oil still relatively plentiful, gasoline-powered cars remained the default. Without tax incentives to buy EVs, they were simply not an attractive choice for most consumers.

Murphy’s stance on EV charging has been characteristically disciplined: don’t chase the hype. Let others subsidize the buildout. Participate when the economics make sense.

In the meantime, the company kept doing what it has done best—execute, reinvest selectively, and compound. The board continued to support growth through new-to-industry (NTI) locations and reinvestment opportunities aimed at driving earnings and cash flow. Management described the NTI pipeline as robust, backing its stated goal of opening 50 or more NTIs per year. That pipeline would also be supplemented with smaller real estate opportunities, like a recent acquisition of four sites in the Denver market.

The final lesson of Murphy USA is the one you don’t expect from a business built on “declining” categories: sometimes the best businesses are the ones everyone assumes are dying. While the market chased disruption and exponential growth, Murphy played a different game. It didn’t try to grow faster. It tried to survive longer. It didn’t win by inventing new products. It won by obsessing over unit economics—and by treating capital efficiency as the product.

Murphy USA is a masterclass in playing the hand you’re dealt—legacy fuels, declining tobacco consumption, and a Walmart partnership that stopped being a growth engine—and playing it to perfection. In the end, it proved that the most powerful force in investing isn’t always growth.

It’s discipline.

X. Sources & Further Reading

- Murphy USA Investor Relations: annual reports, quarterly earnings call transcripts, and Investor Day decks

- Murphy USA SEC Filings: Form 10-K and 10-Q reports

- Murphy USA press release and materials on the QuickChek acquisition (December 2020)

- Convenience Store News: industry coverage and retailer profiles

- CSP Daily News: convenience store industry reporting and analysis

- U.S. EPA: Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) overview and RIN market documentation

- National Association of Convenience Stores (NACS): industry reports and market data

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music