Micron Technology: The Last American Memory Maker

I. Introduction & The "Memory Wall" Thesis

Picture this: a cold February morning in 2024. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang walks onstage and pulls the curtain back on the H200 AI accelerator, a chip meant to power the next wave of large language models—ChatGPT and whatever comes after it.

But the most important part of that package isn’t the flashy GPU die everyone photographs. It’s what sits beside it and on top of it: a dense, vertical stack of memory chips, almost too small to notice, doing the unglamorous work of feeding the beast. That stack is High Bandwidth Memory—HBM—and some of it is coming from Micron Technology in Boise, Idaho.

Which is a wild sentence, if you think about it.

In a world where the cutting edge of semiconductors feels like it lives entirely in Seoul, Taiwan, and Tokyo, Micron is the only American company left standing in the brutal business of memory.

So how did a potato billionaire’s side project in Idaho turn into one of the most strategically important semiconductor companies in the United States? That’s the story we’re here to tell.

To understand why Micron matters, you have to understand what engineers call the Memory Wall.

Think of a modern computer—or, more relevant today, an AI data center—as a factory. The processors (Nvidia GPUs, AMD chips, custom accelerators) are the workers. They can do mind-bending amounts of math. But those workers still need raw materials: data. And that data lives in memory.

Here’s the catch: processor performance has been sprinting for decades, while memory has been jogging. Memory improves, but more gradually. The result is a bottleneck where the fastest chips on Earth spend too much of their time waiting—like a Formula 1 car trapped behind a school bus. For AI, where models like GPT-4 constantly move massive amounts of data in and out of active computation, that waiting becomes the real constraint. Not just on speed, but on power consumption, heat, and ultimately the economics of running a data center.

HBM is the industry’s answer to that wall. It’s memory built to deliver data fast enough to keep GPUs busy. But it comes with a tradeoff that ripples through the entire market: HBM takes roughly three times the wafer area of standard DDR5 to produce the same number of bits. So when fabs prioritize HBM to satisfy AI demand, they’re implicitly producing less “regular” memory. Supply tightens. Prices rise. And suddenly the AI boom doesn’t just lift HBM—it pulls up the whole DRAM complex, from servers to PCs.

That’s why HBM isn’t just another product cycle. It’s becoming the critical enabler of the AI era, and the companies that can make it—at scale, at yield, to spec—hold disproportionate power.

The HBM market was about $18 billion in calendar 2024. It was expected to grow to around $35 billion in 2025. And further out, projections point to something like a $100 billion market by 2030.

Now for the sobering reality of who actually makes this stuff.

Global memory—traditional DRAM and advanced HBM—is controlled by exactly three companies: Samsung and SK Hynix in South Korea, and Micron in the United States. In early 2025, SK Hynix took the revenue lead in DRAM for the first time, with 36% share in Q1. Samsung followed at 34%. Micron held 25%.

In HBM—the part of the market where the AI action is—SK Hynix led in Q2 with 62% share. Micron followed with 21%. Samsung trailed with 17%. And that last datapoint matters, because Samsung, the world’s largest semiconductor manufacturer, had stumbled badly here. The company struggled to meet Nvidia’s specs due to yield issues, leaving SK Hynix and Micron as the primary suppliers into the AI accelerator gold rush.

Micron is the only U.S.-based manufacturer of advanced memory chips. Its DRAM ends up everywhere: AI and high-performance computing, cars, networking, next-generation wireless devices. And yet, today, 100% of leading-edge DRAM production happens overseas, largely in East Asia.

That’s the pivot from business story to geopolitical story.

In an era when semiconductors are a frontline of great-power competition, “the last American memory maker” isn’t just a catchy tagline. It’s a national security problem—and, potentially, a national advantage.

For investors, the questions are simple to ask and hard to answer: Can Micron keep its technological momentum? Is the AI-driven “supercycle” actually different from the memory industry’s historic boom-and-bust? And what does it mean when a company becomes both a cutting-edge supplier and a strategic asset?

To get there, we have to go back to the beginning—to a basement in Boise, and a potato farmer who saw the future.

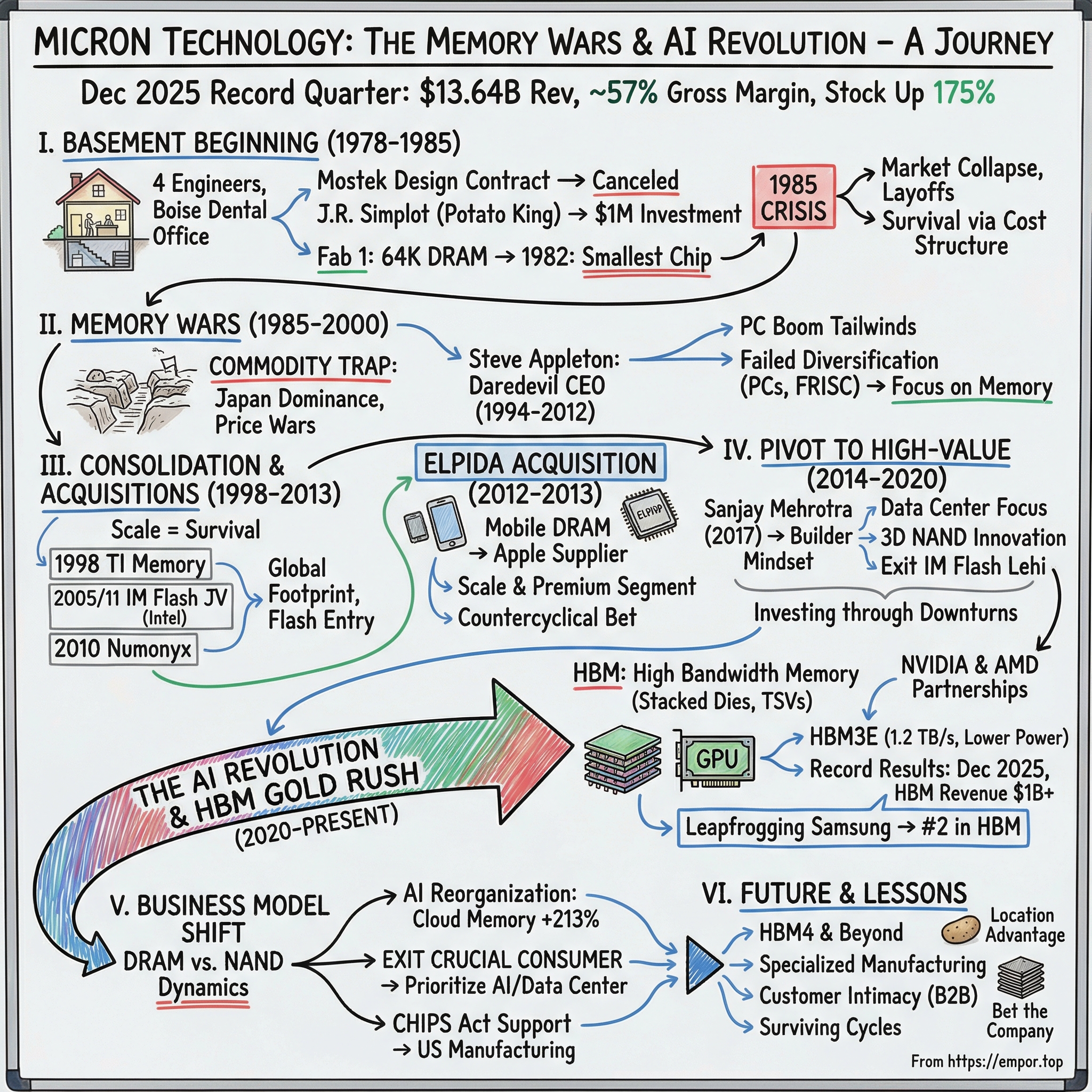

II. Origins: Potatoes, Planes, and Persistence (1978–2000s)

In the late 1970s, Boise, Idaho wasn’t a tech town. It was potato country—irrigation systems, farm equipment, cattle, and the big local fortunes that came with feeding America. The semiconductor world lived somewhere else: Silicon Valley, Texas, Boston. Nobody sane was trying to build memory chips in Idaho.

And yet, in 1978, four engineers—Ward Parkinson, Joe Parkinson, Dennis Wilson, and Doug Pitman—did exactly that. They formed Micron in Boise as a semiconductor design consulting shop, working out of a modest office in the basement of a dental building. Early on, they weren’t making chips. They were drawing them—designing circuit layouts for other companies.

But consulting doesn’t scale into an industrial powerhouse. The founders had bigger ambitions: a new, smaller version of the 64K DRAM, a memory chip that stored about 64,000 bits. By 1981, they made the decision that would define everything that followed: Micron wouldn’t just design semiconductors. It would manufacture them.

Which immediately raised the only question that matters in chipmaking: who’s paying?

A fabrication plant—“a fab”—is one of the most capital-intensive things humans build. You need ultra-clean rooms, impossibly expensive equipment, and teams of specialized engineers. And in 1980, venture capital in the modern sense barely existed. Venture capital in Idaho might as well have been science fiction.

Micron scraped together its first outside money through a very Idaho kind of connection. Ward Parkinson got to know a Boise businessman named Allen Noble after an almost comic scene: Parkinson, wearing a business suit, waded into Noble’s muddy potato field to hunt down a malfunctioning electric component in an irrigation system. That relationship turned into $100,000 of seed funding from Noble and a couple of wealthy local friends.

Useful—but nowhere close to fab money.

For that, they needed someone with real capital. Enter J.R. Simplot.

John Richard Simplot was the founder of the Boise-based J.R. Simplot Company, an agricultural supplier that became synonymous with potato products. He was a self-made American legend: an eighth-grade dropout who built an empire. One of the pivotal moments came in 1967, when Simplot and McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc struck a handshake deal for Simplot to supply frozen french fries.

That might sound mundane, but it solved a brutal operational problem. Restaurants used to cut potatoes on-site, and the favored russet wasn’t available for part of the summer, which meant inconsistent fries and inconsistent quality. Simplot could deliver frozen russets year-round. By 1972, all McDonald’s fries were frozen. By 2005, Simplot supplied more than half of the fries for the chain. If you want to understand Simplot’s wealth, start there: McDonald’s scale, multiplied by fries, multiplied by decades.

So why would the potato king bankroll semiconductors?

Simplot was persuaded—by his son, through local connections—to back Micron and build a fab in Idaho. And he didn’t treat it like a hobby. “We’re going to make some millionaires out here in the sage-brush,” he said.

In 1980, Simplot invested $1 million in Micron for a 40% stake. It was the definition of patient capital from someone who understood commodity cycles firsthand—agriculture can make you rich one year and humble you the next. As it turned out, memory chips ran on a similar boom-and-bust rhythm.

Micron’s “overnight success” took years of grind, faith, and more than a few moments where it looked like good money was chasing bad. Simplot wasn’t a late-arriving cheerleader. He was there early, and he stayed. He helped keep Micron standing when it wobbled.

By 1981, Micron had transitioned from design consultancy to manufacturer and set up its first wafer fabrication unit, Fab 1, focused on producing 64K DRAM. A year later, Micron shipped more than a million chips and earned praise for quality—and for something that mattered immensely in memory: size. These chips were notably smaller than competitors’ products, including those from Motorola and Hitachi.

In 1984, Micron went public, raising the capital it needed to keep expanding. And almost immediately it ran into the defining adversary of its early life: the Japanese DRAM industry.

The memory wars of the 1980s are one of those chapters of American industrial history that should be taught more than it is. As U.S. computer makers consumed more DRAM, they increasingly adopted Japanese chips that were widely respected for quality, delivery, and price. Japan surged to the leading edge in design and manufacturing. In 64K DRAM, Japanese firms overtook the U.S. in 1981. By 1987, Japan controlled roughly 80% of the DRAM market, driven largely by 256K DRAMs.

Then came the part that kills companies: prices collapsed. Japanese firms flooded markets, memory prices fell about 60% in a year, and one American memory maker after another exited. Even Intel—the company that had brought DRAMs to market in the first place—walked away.

Micron didn’t.

In 1985, it became the first company to file a complaint with the International Trade Commission accusing Toshiba, Fujitsu, Hitachi, and others of dumping—pricing below cost to break competitors. The industry pressure escalated. In June 1985, the Semiconductor Industry Association filed a dumping lawsuit with the U.S. Trade Representative under Section 301 of the U.S. Trade Act of 1974. More cases followed—Micron against Japanese 64K DRAMs, Intel against Japanese EPROMs—and in 1986 the ITC ruled that Japanese 64K DRAMs had harmed the United States.

This wasn’t just Micron trying to win a trade case. It was a fight over whether America would have any merchant DRAM manufacturing left. After the dust settled, only two U.S. firms—Texas Instruments and Micron—remained positioned to benefit from the antidumping actions.

A few years later, Micron was still alive, employing about 900 people. As one analyst put it at the time: “For this little Podunk company to go toe to toe with the Japanese in an area that the Japanese dominate is a pretty remarkable story.”

That period also forged Micron’s culture. Survival required obsession: operational efficiency, manufacturing discipline, squeezing yield out of every step, and making it through cycles that were brutal even by semiconductor standards. During the crisis years, Micron’s board began meeting every Monday morning at Elmer’s Pancake House. It became ritual, and it stuck. Even as Micron grew into a company with billions in revenue, the board still gathered at Elmer’s—two ceramic pigs perched atop a rotating cake display—at 5:45 a.m. once a week. This was the “Idaho Way”: frugal, unglamorous, and relentlessly focused on execution.

In 1994, founder Joe Parkinson retired as CEO and Steve Appleton took over as Chairman, President, and CEO. Appleton would lead Micron through a volatile era—consolidation, the dot-com boom and bust, and the rise and reshaping of the PC industry.

And then, later, his tenure would end suddenly and tragically—another test of whether Micron could keep doing what it had always done: survive.

III. Inflection Point 1: The Great Consolidation & The Elpida Masterstroke (2008–2013)

By the late 2000s, the memory business was back in its natural state: chaos.

The global financial crisis crushed demand. DRAM prices collapsed. Losses piled up fast enough that even the survivors of the 1980s trade wars started to look mortal. Micron took its share of the pain, cutting roughly 15% of its workforce in October 2008, then eliminating about 2,000 more roles in 2009. This wasn’t a “restructuring.” It was triage.

Around Micron, the industry began to break apart.

Germany’s Qimonda—spun out of Infineon—filed for bankruptcy in 2009, at the time the largest semiconductor bankruptcy ever. Taiwanese memory makers were on life support. In Japan, Elpida Memory limped along on government aid, but the math of the cycle was catching up with it too.

Then Micron got hit with something worse than a down cycle.

On February 3, 2012, CEO Steve Appleton was killed in a plane crash at Boise Airport, moments after takeoff, while attempting an emergency landing in a Lancair IV-PT experimental-category aircraft. He’d aborted a takeoff minutes earlier for reasons that weren’t known at the time. One day Micron was fighting through negotiations and market turmoil; the next, it was leaderless in the middle of the storm.

Appleton wasn’t a distant executive. He was Micron’s embodiment.

Born and raised in Southern California, he came to Boise State University, played tennis for the Broncos, and joined Micron in 1983 after graduation. His first job was the night shift in production, earning less than five dollars an hour. From there he climbed the ladder the hard way: fab manager, production manager, director of manufacturing, vice president of manufacturing. By 1991 he was president and COO, and in 1994—at just 34—he became CEO and chairman.

He was also a lifelong aviation enthusiast. He’d survived a previous crash in 2004 with serious injuries, and there had been governance concerns over whether a sitting CEO should be doing something that risky. But Micron’s board accepted it as part of Appleton’s work-hard, play-hard persona.

Idaho felt his death immediately. Leaders across the state praised him as a visionary and a champion of excellence. Idaho’s congressional delegation compared what he meant to the state to what Steve Jobs had meant to America. For Micron, the grief was real—but so was the operational problem: this was a company in a brutal industry, negotiating a once-in-a-generation deal, and it suddenly didn’t have its CEO.

Micron hadn’t named a successor. The sitting president and COO, Mark Durcan, had to step in.

And what landed on Durcan’s desk was the defining opportunity of Micron’s modern history.

That same month—February 2012—Elpida filed for bankruptcy. This wasn’t some second-tier player. Elpida had been Japan’s last major DRAM manufacturer, formed from the consolidated DRAM operations of Hitachi, NEC, and Mitsubishi. It had strong technology, especially in mobile DRAM—the kind that mattered for smartphones and tablets.

Elpida itself was a product of consolidation. It was founded in 1999 through a merger of NEC’s and Hitachi’s DRAM operations, began DRAM development work in 2000, and as Japan’s industry reorganized, other semiconductor operations were spun off into Renesas. When the 2008 crash hit, Elpida received 140 billion yen in financial aid and loans from the Japanese government and banks in 2009. It bought time, but it didn’t change the economics. By 2012, Elpida was out of runway.

Micron moved in.

Under a Sponsor Agreement entered into on July 2, 2012, Micron pursued the acquisition—and on July 31, 2013, the deal closed. Micron acquired 100% of Elpida’s equity for 200 billion yen (about US$2.5 billion) and also acquired an approximately 24% stake in Rexchip Electronics Corp. from Powerchip Technology Corporation for US$335 million.

It was a masterstroke for three reasons.

First: scale. The transactions added about 185,000 300-mm wafers per month of production capacity—roughly a 45% increase for Micron. In memory, scale isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s the difference between being a price taker and staying alive.

Second: technology and mix. Elpida brought serious mobile DRAM capability—expertise built for the tight power and performance constraints of phones and tablets—while Micron had strength in enterprise DRAM for servers and networking, plus a broad portfolio across NAND flash and NOR. Put them together and Micron wasn’t just bigger; it was better positioned across the most important end markets.

Third—and this is the part people miss—customers. Elpida was a major supplier of memory chips to Apple, and Apple had reportedly placed a huge order with Elpida ahead of iPhone 5 production. So Micron didn’t just buy fabs and process recipes. It inherited one of the best customers in the world, right as the smartphone became the dominant computing platform on Earth.

The deal was transformative. It vaulted Micron into the ranks of the very largest memory manufacturers and helped make it the second-largest memory company in the world at the time.

More importantly, it marked the beginning of a structural change in the industry itself.

With Qimonda gone, Elpida absorbed, and a long list of Taiwanese and Japanese players either bankrupt or exiting, memory stopped being a sprawling battlefield and started turning into something closer to an “oligopoly.” Micron had already been building itself through acquisition—like buying Texas Instruments’ memory business in 1998—and Elpida was the capstone move that cemented it as the only major U.S.-based DRAM manufacturer.

By 2013, the memory world had narrowed to three true giants: Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron.

That three-player structure would prove remarkably durable. And in time, it would change the most important assumption in the entire sector: that memory had to be a suicidal commodity business. The shift toward a more rational, consolidated industry started here—even if it took years for the implications to fully show up in the numbers.

IV. Inflection Point 2: The Sanjay Mehrotra Era & The "Process" Pivot (2017–2022)

By early 2017, Micron had pulled off the Elpida deal and helped reshape the industry into a three-player arena. But it still carried an old reputation: scrappy, efficient, and always a step behind the technology leaders.

Then Mark Durcan announced he planned to retire.

Micron’s board kicked off a wide search—more than 50 candidates considered, at least 15 seriously interviewed—before landing on a choice that would have been unthinkable for most of Micron’s history. Sanjay Mehrotra was named CEO after Durcan’s February 2017 retirement announcement, with the appointment effective May 8, 2017. Durcan stayed on as an adviser into early August.

The headline wasn’t just the name. It was what the name represented.

Mehrotra was the first outsider ever to run Micron. Until then, every CEO had been a Micron lifer—people who grew up inside the Idaho Way, promoted through manufacturing and operations. Mehrotra came from a different lineage: product, strategy, and the flash-memory revolution.

He had co-founded SanDisk in 1988 and ultimately led it as president and CEO from 2011 until Western Digital acquired the company in 2016. SanDisk wasn’t a sleepy incumbent. It was one of the companies that helped turn flash memory from a clever idea into a global, category-defining business. After that $19 billion acquisition, Mehrotra was free—and Micron saw a rare opportunity to hire someone who understood memory at the deepest technical level, but who would challenge the company’s default settings.

Those defaults had a name inside the industry: fast follower.

For years, Micron’s playbook had been pragmatic. Let Samsung or SK Hynix take the first arrows on a new manufacturing node, work out the ugly yield problems, and then follow a year or two later—often with strong cost discipline and execution, but rarely with the bragging rights of being first. It was a survival strategy in a business where mistakes can wipe out a year of profits. But it also meant Micron was almost always playing from behind.

Mehrotra’s mandate was to change that. Not with speeches, but with process leadership and disciplined capital spending—investing where it mattered, not chasing volume for its own sake.

To appreciate what changed, you need the simplest version of how DRAM progress works. Memory chips are built on silicon wafers using photolithography—patterns printed again and again at microscopic scale. Shrink the features, and you can pack more memory into the same space, often with better performance and lower power. The industry tracks those shrink steps as “nodes.” By the 2010s, DRAM makers used a 10-nanometer-class naming scheme: 1X, 1Y, 1Z, then 1α (1-alpha), 1β (1-beta), and 1γ (1-gamma). Each step typically delivers meaningful gains in density and efficiency—the sort of improvement that directly decides who makes money in the next cycle.

Here’s the reversal: in January 2021, Micron became the first supplier to begin shipping DRAM built on its 1α process. And in May 2022, Micron shared early details of its next-generation 1β DRAM technology, positioning it as an advance beyond its 1α-based products.

The company described 1β as smaller and more power-efficient than 1α, with testing indicating generational performance improvement and roughly a 15% efficiency gain. That matters everywhere, but especially in mobile—where the customer wants more performance and longer battery life at the same time.

For Micron, this was a psychological break with the past. The company that had made a career out of catching up was now, in key moments, setting the pace. Samsung and SK Hynix weren’t the reference point anymore. They were the ones who had to respond.

And it wasn’t just DRAM. Under Mehrotra, Micron also pushed hard in NAND flash, reaching 232-layer NAND—another milestone that signaled something bigger than a single product launch. The message was consistent: Micron wasn’t trying to be the cheapest follower. It was trying to be a technology leader that could earn a premium.

But leadership in memory isn’t only about inventing the next node. It’s about manufacturing it—reliably, repeatedly, across the world.

Mehrotra drove what he called “copy-exact” manufacturing: the idea that Micron’s fabs should run with standardized processes and data-driven controls so that a chip built in one facility would be effectively identical to a chip built in another. Less variability means better yields. Better yields mean faster ramps. Faster ramps mean you can lead a node without getting punished for it.

By 2022, the contours of the new Micron were coming into focus. The story investors had told for decades—buy Micron at the bottom of the bust, sell it at the top of the boom—started to feel incomplete. This wasn’t just a cyclical commodity company riding tides it couldn’t control. It was becoming a company trying to change the shape of its own economics through process leadership and execution.

The shift from “value player” to “technology leader” wasn’t about pride. In memory, being first—or even credibly near first—means you can sell more of the best bits, at better pricing, into the most demanding end markets. In an industry built on brutal cycles, that kind of advantage isn’t cosmetic.

It’s survival, upgraded.

V. Inflection Point 3: The Geopolitical Chessboard & The CHIPS Act (2020–Present)

By the 2020s, Micron wasn’t just selling chips into global supply chains. It was sitting squarely in the middle of the U.S.-China technology showdown. And because Micron is the only American company that can manufacture leading-edge memory at scale, it became two things at once: a tempting target for retaliation, and a strategic asset Washington couldn’t afford to lose.

The first warning shot came a few years earlier. In 2019, the Trump administration barred U.S. companies from selling certain advanced technologies to Huawei. That move rippled through the entire semiconductor ecosystem. For Micron, it meant a major customer effectively disappeared overnight.

But the real gut punch landed in 2023.

On May 21, China’s Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) announced that Micron had failed a cybersecurity review, and ordered “critical infrastructure operators” in China to stop buying Micron products. In the U.S., the decision was widely viewed as retaliation for American restrictions aimed at cutting off China’s access to advanced semiconductor technology.

Micron said the ban could cost it a “high single digit” percentage of annual revenue. And the timing mattered: China had been Micron’s third-largest market, representing 10.7% of annual revenue in 2022. This wasn’t a symbolic slap. It was a revenue hit with real teeth.

What made the move even more pointed was who China didn’t target. Samsung and SK Hynix—the other two members of the “Big 3” memory club—weren’t hit the same way. Beijing’s play looked deliberate: squeeze the American supplier, leave the South Koreans room to benefit, and quietly test the seams in the U.S.-South Korea alliance. Classic wedge strategy.

On the ground, the effects were exactly what you’d expect. With Micron restricted in critical infrastructure, rivals had an opening into China’s data center buildout. Samsung and SK Hynix benefited, and Chinese memory players like YMTC and CXMT—backed by state support and expanding aggressively—had even more incentive to push forward.

Micron, for its part, eventually acknowledged the new reality. It planned to stop supplying server chips to data centers in China after its business didn’t recover from the 2023 ban. The company effectively exited China’s data center market, even as it continued serving automotive and smartphone customers there.

So China treated Micron as dispensable. The United States did the opposite.

The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022—passed with bipartisan support—was Washington’s bet that the country had to rebuild domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity. And Micron, as the only U.S.-based memory maker, became one of the most important recipients.

The Biden-Harris Administration announced that the U.S. Department of Commerce would award Micron up to $6.165 billion in direct CHIPS Act funding. The stated goal was to support the first step in Micron’s long-range plan: roughly $100 billion of investment in New York and $25 billion in Idaho over two decades, tied to job creation and a push to grow America’s share of advanced memory manufacturing from under 2% to about 10% by 2035.

The plan centered on building two fabs in Clay, New York, and one in Boise, Idaho, alongside what the administration framed as tens of billions of dollars of private investment by 2030 as the early phase of an even larger, multi-decade buildout. In both states, the pitch was simple: this would be the largest private investment in their history, with job creation on a scale that local politicians could rally around.

Then, in June 2025, the commitment expanded again. Micron and the Trump Administration announced plans to grow Micron’s U.S. investments to about $150 billion in domestic memory manufacturing and $50 billion in R&D, with an estimated 90,000 direct and indirect jobs. The additional commitments included building a second leading-edge memory fab in Boise, expanding and modernizing Micron’s manufacturing facility in Manassas, Virginia, and bringing advanced packaging to the U.S. to support long-term growth in High Bandwidth Memory.

Micron also said it expected its U.S. investments to qualify for the Advanced Manufacturing Investment Credit, and that it had secured support across local, state, and federal levels— including up to $6.4 billion in CHIPS Act direct funding aimed at supporting two Idaho fabs and two New York fabs, plus the Virginia expansion.

“As the only U.S.-based manufacturer of memory, Micron is uniquely positioned to bring leading-edge memory manufacturing to the U.S., strengthening the country's technology leadership and fostering advanced innovation,” CEO Sanjay Mehrotra said.

This is the moment where Micron’s identity shifts again. It’s still a cyclical semiconductor company that lives and dies by execution, yields, and pricing. But it’s also now a national capability—something the U.S. government is explicitly willing to subsidize because the alternative is total dependence on foreign supply for one of the most critical inputs in modern computing.

That comes with a benefit: a kind of backstop, a “put option” in the sense that Washington has demonstrated it will step in with billions to keep domestic memory alive.

It also comes with a cost. Micron now operates in a world where a government agency decision in Beijing can erase a chunk of revenue, and a policy decision in Washington can reshape its capital plan for decades.

The company didn’t choose to become a geopolitical chess piece. But in the 2020s, being the last American memory maker meant there was no way to avoid it.

VI. The AI Supercycle: HBM and The Nvidia Partnership

While geopolitics was turning Micron into a strategic asset, a different force was remaking its day-to-day business: generative AI. ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and whatever comes next didn’t just increase demand for memory. They created explosive demand for a very specific kind of memory: High Bandwidth Memory, or HBM.

HBM exists because of the Memory Wall. Standard DDR5 moves data over a relatively narrow interface—64 bits wide. For an AI model that’s constantly shuffling gigantic parameter sets, that’s like trying to supply an industrial factory through a single-lane road.

HBM takes a different approach. Instead of laying memory chips out flat, it stacks them vertically, connects them with thousands of microscopic “through-silicon vias” (TSVs), and places the whole stack right next to the GPU so data doesn’t have to travel far. Micron’s HBM3E delivers pin speed greater than 9.2Gbps at an industry-leading bandwidth of more than 1.2 TB/s per placement. It offers 24GB capacity using an 8-high stack and 36GB capacity using a 12-high stack.

Put that next to standard DDR5—roughly 50 gigabytes per second—and you see why HBM isn’t a nice-to-have for AI accelerators. It’s the difference between a GPU sprinting and a GPU waiting.

The catch is that HBM is brutally hard to make. As Micron has said, “Industrywide, HBM3E consumes approximately three times the wafer supply as DDR5 to produce a given number of bits in the same technology node.” Stacking dies, drilling TSVs, bonding everything together, and then getting it to run reliably under extreme heat loads is manufacturing pain—lower yields, higher costs, and far more ways for things to go wrong.

For years, SK Hynix owned this market, in large part because it locked in the early partnership with Nvidia. Micron was a smaller player. Samsung, despite its scale, struggled with yield issues and couldn’t get qualified for Nvidia’s highest-end GPUs.

Micron’s move was a classic “don’t fight the last war” bet. It participated in the HBM2E generation, skipped HBM3, and went straight at HBM3E—trying to leap ahead instead of catching up. The wager was that Micron’s strength in power efficiency, built over years serving mobile customers, would translate perfectly to AI data centers where power and heat are the limiting factors.

Micron tied that bet to its broader process push: 1ß (1-beta) DRAM leadership and packaging advances that, in the company’s framing, improved the efficiency of data flow into and out of the GPU. It also claimed its 8-high and 12-high HBM3E “memory cubes” could deliver up to 30% lower power consumption than competing offerings.

In AI, that’s not a footnote. Power isn’t just an operating expense—it’s a deployment constraint. Every watt you save is a little less cooling infrastructure, a little more density in the rack, and a little less friction scaling up a cluster.

And crucially, the bet got pulled into the center of the gold rush. Micron’s HBM3E 24GB 8-high began shipping in NVIDIA H200 Tensor Core GPUs starting in the second calendar quarter of 2024.

“Our HBM is sold out for calendar 2024, and the overwhelming majority of our 2025 supply has already been allocated,” Sanjay Mehrotra said.

“We expect to generate several hundred million dollars of revenue from HBM in fiscal 2024 and multiple billions of dollars in revenue from HBM in fiscal 2025,” he told Wall Street. He also said Micron expected to reach HBM market share commensurate with its overall DRAM share sometime in calendar 2025.

By Mehrotra’s account, that ramp was playing out: he said that in the second half of calendar 2025, Micron would have HBM share broadly in line with its share in mainstream DRAM—around 20%.

The customer list also started to widen. AMD used eight-high HBM3E stacks from Micron in its Instinct MI325X GPU accelerators to deliver 256 GB of capacity. And with HBM becoming table stakes for every next-gen AI GPU, Micron was positioning itself for future platforms too—likely including Nvidia’s “Rubin” R200 and AMD’s “Altair” MI400.

Micron was already pointing beyond HBM3E as well. It said its future HBM4 would build on its 1-beta process and use a custom logic base die, targeting more than 2 TB/sec per HBM4 stack—about 60% more bandwidth than HBM3E—along with 20% lower power consumption than its twelve-high HBM3E.

Then the financials caught up to the story.

In fiscal 2025, Micron’s revenue rose nearly 50% to a record $37.4 billion, and gross margins expanded by 17 percentage points to 41%. EPS reached $8.29, up 538% from the prior year.

“Micron delivered a record quarter, and our data center revenue surpassed 50% of our total revenue for the first time,” Mehrotra said in December 2024.

That line is the real pivot. This was the company that used to be whipsawed by PCs and smartphones—markets famous for brutal demand swings. Now, for the first time, data centers were driving the bus. And unlike past memory booms, this demand wasn’t just consumers upgrading gadgets. It was the buildout of AI infrastructure—clusters, racks, and megawatts—that looked less like a fad and more like a new baseline for the modern economy.

VII. The Playbook: Strategic Analysis

Hamilton Helmer's "7 Powers" framework is a useful way to pressure-test Micron’s position—what’s real, what’s fragile, and what actually compounds over time in a business as unforgiving as memory.

Scale Economies: The entrance fee for memory manufacturing has become so large it may as well be a wall. A leading-edge DRAM fab can cost $15–$20 billion before it’s producing a single sellable chip. And that’s the easy part. The harder part is funding the R&D and the constant reinvestment cycle after cycle. The incumbents—Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron—spread those costs across enormous volumes. A new entrant can’t. Micron planned to spend around $14 billion on capital expenses in fiscal 2025 across its manufacturing footprint, which tells you everything you need to know: this isn’t an industry anyone is casually “entering.”

Process Power: This may be Micron’s most important moat. At the leading edge, “making memory” isn’t just a design problem—it’s a manufacturing learning curve measured in decades. It’s yield curves, defect density, equipment tuning, and thousands of tiny process decisions that compound into whether a ramp is profitable or catastrophic. Because DRAM and NAND are largely standardized (thanks to JEDEC), the differentiation isn’t usually the spec sheet. It’s who can deliver the most bits per wafer, at the lowest power, with the highest yields. That’s why being early—or even credibly near the front—on advanced nodes matters. Stating the obvious: manufacturing leading-edge semiconductors is incredibly hard, and the difficulty is the point.

Cornered Resource: Micron has a cornered resource its rivals don’t: the U.S. government. Being the only American memory manufacturer changes the rules around it. CHIPS Act support, national security framing, and the broader push to onshore critical supply chains together create something like a strategic floor under Micron. But that status cuts both ways. The same dynamic that brings support in Washington also makes Micron a clean target in Beijing—as the loss of China’s data center market proved.

Counter-Positioning: Under Mehrotra, Micron has increasingly counter-positioned against Samsung’s volume-first instincts. Samsung has historically leaned on scale to win—more capacity, more output, more leverage when pricing turns ugly. Micron has leaned the other way: prioritize high-value products where technology leadership earns premium pricing and customers care about more than cost per bit. HBM3E is the clearest example. Micron isn’t trying to out-volume SK Hynix. It’s trying to win on what matters in AI infrastructure—performance per watt, thermals, and the ability to meet brutal specs at scale.

VIII. Porter's 5 Forces: The "Oligopoly" Update

Rivalry: The memory industry today is not the cutthroat commodity knife fight of the 1980s and 1990s. Yes, Samsung and SK Hynix still compete ferociously on technology and customer wins. But with DRAM pricing rising and supply still tight, the bigger shift is how they’re choosing to compete: more discipline, less self-destruction.

In recent IR meetings with major global investment banks, reports said Samsung and SK Hynix—together roughly 70% of the DRAM market—signaled caution about aggressive capacity expansion. Translation: don’t expect them to flood the market just to grab another point of share. That restraint is one reason some observers think the current “memory super-cycle” could run well past 2028.

This is the structural change that matters: three players who’ve lived through decades of boom-and-bust have learned that the real enemy isn’t each other. It’s the urge to overbuild. Today’s game is returns on investment, not market share at any cost—and that’s what makes this feel like a rational oligopoly.

Threat of New Entrants: Effectively zero. The capital required is staggering, the technology is unforgiving, and the ecosystem is closed to anyone who isn’t already inside the club.

The only potential wild card is China—particularly YMTC and CXMT—backed by heavy state support. But Chinese suppliers still face meaningful technical gaps, including thermal management and operating speed, and U.S. export controls have restricted access to the most advanced manufacturing equipment. They can make progress. The question is how fast, and how far, under constraint.

Supplier Power: High—and it’s one of the most underappreciated risks in the whole stack. At the center sits ASML, the near-single point of failure for leading-edge lithography. Its EUV (Extreme Ultra Violet) scanners use shorter-wavelength light to print smaller features, and if you want to manufacture at the frontier, you need them.

The catch is that EUV machines are rare and expensive. ASML reportedly produces only about 30 a year. Each unit is massive—around 180 tons—and costs roughly $120 million. When one company controls that bottleneck, it has real leverage: on pricing, on delivery schedules, and on who gets to ramp first.

Buyer Power: This has flipped. Historically, PC OEMs like Dell and HP had the leverage. They could multi-source, squeeze margins, and treat memory like a commodity input.

Today, the buyers that matter most are AI infrastructure giants—Nvidia, AMD, Google, Microsoft, Meta—who are trying to secure supply for accelerator platforms where memory isn’t optional; it’s performance. When HBM is sold out years ahead, “negotiating power” looks very different. Buyers can push on relationships and long-term commitments, but they can’t conjure extra supply.

Threat of Substitution: Low. DRAM does a job the rest of the industry still can’t replicate economically at scale. Plenty of technologies have tried to dethrone it over the years—MRAM, ReRAM, phase-change memory—but none has come close to replacing DRAM in mainstream computing.

And for AI specifically, HBM has no real substitute. If you need that bandwidth to keep a modern GPU fed, there isn’t a different memory technology waiting in the wings to bail you out.

IX. Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bear Case

For all the talk about a “new era,” memory is still memory: a boom-and-bust business with a long history of humbling anyone who believes the cycle has been tamed. The industry’s reflex has always been to overbuild. Even if 2026 looks effectively “sold out,” the sheer amount of capacity spending underway across the Big 3 could set the table for the familiar ending: a supply glut, falling prices, and pain—potentially by late 2027.

Then there’s the AI story itself. If enterprise adoption turns out slower than the hype, if hyperscalers pull back on spending, or if the “AI bubble” simply deflates, demand for the highest-end memory would cool fast. And when memory cools, it doesn’t glide down. It drops. Micron remains a high-beta company in a high-beta industry; a global recession or a meaningful slowdown in AI infrastructure buildouts at Microsoft, Google, or Meta would hit Micron much harder than it would a more diversified tech giant.

China is the other shoe that never stops hovering. Micron adapted after the 2023 ban, but escalation is still possible—and history suggests retaliation won’t be subtle. At the same time, Chinese competitors like YMTC have every incentive to close the gap. If they eventually overcome their technology constraints, they don’t need to dominate the world to hurt Micron; they just need to be “good enough” at scale in a few key segments.

And underlying all of this is the industry’s harshest truth: capital intensity. Memory manufacturing is a treadmill. You don’t invest to grow—you invest to avoid falling behind. With capex plans running into the tens of billions over time, free cash flow can look great at the top of the cycle and evaporate quickly when conditions turn.

The Bull Case

The optimistic view is that this time really is different—not because humans suddenly became disciplined, but because the underlying demand is being rewritten by computing itself. AI is changing what a “server” is. In 2026, an AI server can require roughly eight to ten times the DRAM of a standard enterprise server. That’s not a tweak. That’s a new baseline. And as “Edge AI” starts pushing models onto devices like smartphones and PCs, it sets up a consumer replacement cycle that pulls more memory into everyday hardware, with 16GB to 32GB of RAM increasingly treated as the new floor.

The second bull pillar is structure. Three players control the market, and they’ve all lived through enough carnage to understand the enemy is not competition—it’s irrational expansion. In a consolidated industry where the incentives skew toward returns instead of sheer volume, the amplitude of the cycle can shrink. It may not disappear, but it can get less murderous.

Third: Micron’s positioning has changed. Under Mehrotra, it’s no longer framed as the perpetual fast follower. Micron has pointed to its technology leadership—like being first to begin shipping DRAM on its 1α (1-alpha) process technology in January 2021—as evidence it can lead at the frontier. In memory, leading-edge process translates into better cost, better power, and often better pricing power, especially in premium markets like data centers and AI.

And finally, there’s the unusual kind of protection Micron now has: strategic importance. The U.S. government has made it clear it wants domestic memory manufacturing to exist and to expand. That doesn’t make Micron immune to cycles, but it does create something close to an insurance policy—real downside support that almost no other cyclical semiconductor company gets to claim.

X. Key Performance Indicators to Track

If you want to track whether Micron is actually becoming the “new Micron,” there are three numbers that cut through the noise:

1. HBM revenue as a percentage of total revenue: This is the clearest signal that Micron is moving from commodity memory toward being an AI infrastructure supplier. The higher the HBM mix, the more Micron’s results reflect premium products and longer-lived demand, not just the usual memory cycle.

2. Gross margin: This is the scoreboard. It tells you whether Micron’s process leadership and product strategy are turning into real economic power. The swing from low-20s gross margins in weaker years to 40%+ in fiscal 2025 is the difference between “surviving the cycle” and actually shaping it.

3. Data center revenue mix: When data center revenue rises to more than half of the business, Micron’s center of gravity changes. It relies less on the whiplash of PCs and smartphones and more on buildouts that tend to be planned years in advance. In theory, that shift should smooth out some of the historic volatility—even if it can’t erase it.

XI. Conclusion: The Grand Narrative

From a basement in Boise to the geopolitical fulcrum of the 21st century, Micron’s journey reads like an American industrial epic hiding in plain sight.

This is the company that stared down Japanese dumping in the 1980s while almost every other U.S. memory maker disappeared. It made it through the 2008–2009 collapse, then through the sudden, devastating loss of Steve Appleton in 2012. It used the Elpida deal to remake itself, and under Sanjay Mehrotra it worked its way out of the “fast follower” box and into real process leadership. It absorbed China’s retaliation, then found itself on the receiving end of Washington’s reshoring push—not as a nice-to-have, but as something the U.S. government decided it couldn’t afford to lose. And now, in the AI era, Micron sits in the critical path: its HBM feeding the GPUs that train and run the models reshaping the economy.

There’s a poetic symmetry in where all of this started: J.R. Simplot.

Simplot loved Micron. Through the company’s constant ups and downs, he stayed a stalwart backer. His phone number was available to anyone, he answered the phone himself, and he’d talk about Micron until you couldn’t take any more.

Simplot died in 2008 at age 99. He didn’t live to see Micron become a strategic national asset, or a key supplier into the AI buildout. But he saw it when it was still just a handful of engineers in a dental office basement. And he understood something that applies to both potatoes and memory chips: in a commodity world, the winners aren’t the loudest. They’re the relentless, the efficient, and the ones who survive long enough for the world to change around them.

In an era obsessed with software, Micron is the uncomfortable reminder that hardware still sets the limits. The smartest model in the world can’t think if it can’t move data fast enough, store enough of it, and do it without melting the rack. As one industry observer put it: in a world of “software is eating the world,” hardware provides the plate. And Micron makes the plate.

XII. Sources & Further Reading

If you want the bigger backdrop—the way semiconductors went from “nerd industry” to the center of global power politics—Chris Miller’s Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology is a great place to start. It’s the clearest single narrative of how we got from early Silicon Valley to today’s U.S.-China technology competition.

For Micron specifically, the most useful primary sources are the unglamorous ones: company filings and transcripts. Micron’s 10-Ks and quarterly earnings calls lay out the operational reality—capex, node transitions, end-market exposure, and where demand is actually coming from. And if you read them over time, you can see the company’s self-image changing in real time: from bracing for the next down cycle to talking like a manufacturing leader with a front-row seat in AI infrastructure.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music