Minerals Technologies Inc.: From Paper Coatings to Global Performance Materials

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Modern life runs on materials most of us never notice. They’re in the cat litter boxes of millions of American homes. They’re inside the blazing heat of steel blast furnaces from Pittsburgh to Shanghai. And, for decades, they were on the glossy pages of the magazines people used to read in print.

Somewhere in that invisible infrastructure sits a company almost nobody can name: Minerals Technologies Inc. It trades on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker MTX and, as of November 2025, had a market capitalization of nearly $1.78 billion on trailing twelve-month revenue of $2.07 billion. It’s the kind of business Warren Buffett might call “moaty,” even though its products live in the industrial backrooms of the economy. A hidden champion, in other words—unsexy, essential, and surprisingly resilient.

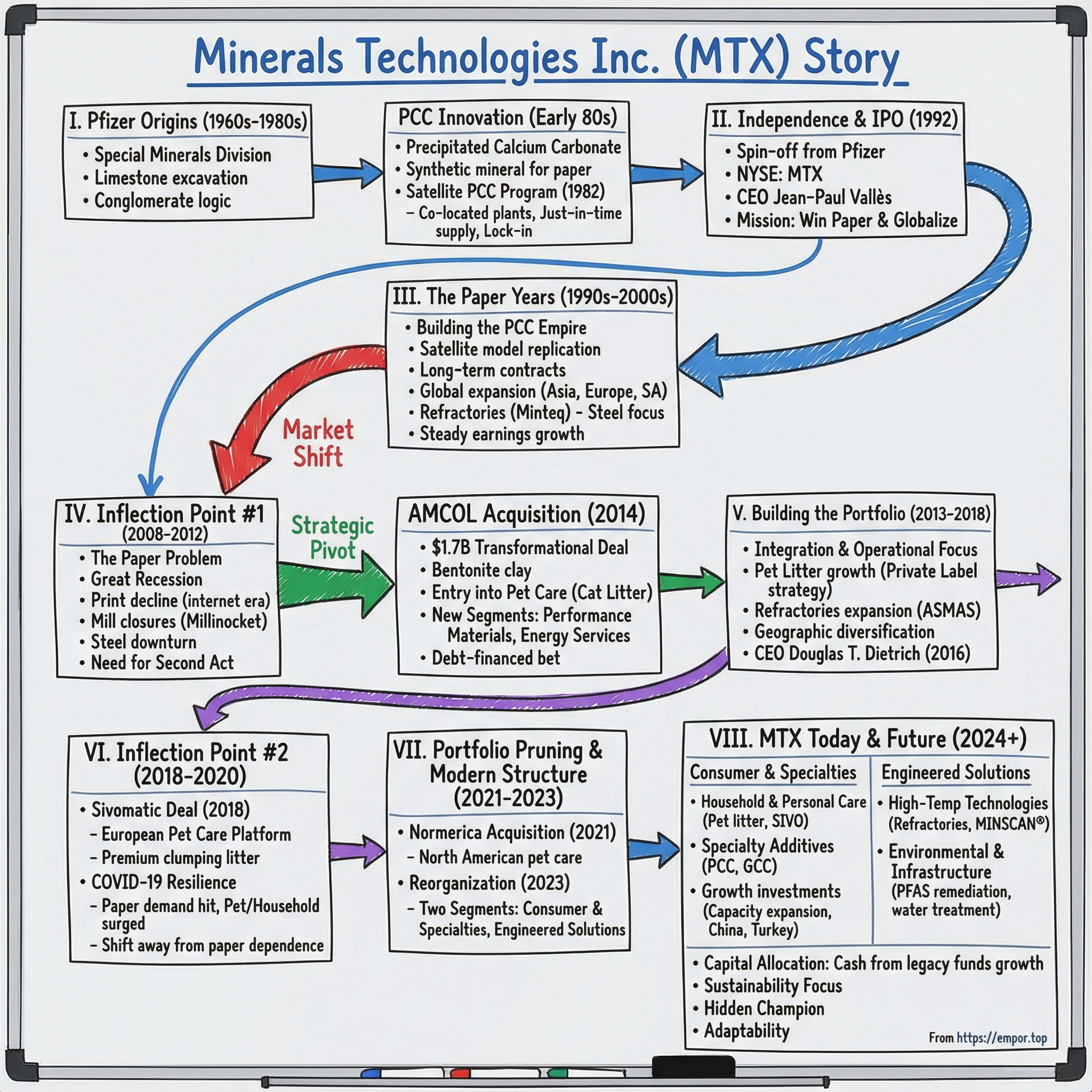

The question that drives this story is simple on its face: how did a paper-coatings minerals spin-off become a diversified performance materials company? The real answer is messier—and more interesting. It’s three decades of strategic reinvention: a company confronting a slow-motion collapse in its core end market, then using disciplined execution and bold M&A to build a new portfolio while the old one shrank underneath it.

For much of its history, Minerals Technologies was best known for two things. First, precipitated calcium carbonate, or PCC—a filler and pigment that changed how paper was made in North America through an innovative co-located production model. Second, mineral-based monolithic refractory products, the heat-resistant materials that keep steelmaking equipment running. That’s the origin story. But it’s no longer the full story.

Today, its Consumer & Specialties segment reaches into household and personal care products: pet litter, personal care, fabric care, edible oil purification, animal health, and agricultural applications. From paper coating to cat litter. From steel refractories to PFAS remediation. Same company, radically different mix of end markets.

Along the way, a few big themes keep showing up: what happens when a focused pharmaceutical giant spins out an oddball minerals division; how you respond when the market that built you starts evaporating; how M&A can be used not just to “grow,” but to rebalance a portfolio; and how hard it is to build durable competitive advantages in industrial materials, where differentiation is earned one customer and one process improvement at a time.

For investors and operators, MTX is a long-form case study in portfolio transformation—patient, deliberate, and still unfolding.

II. The Pfizer Origins & Minerals Beginnings

Minerals Technologies didn’t start in a garage, or with a lucky mineral strike. It started inside the corridors of Pfizer.

In 1968, Pfizer formed and incorporated a Special Minerals division by stitching together a set of earlier acquisitions in mineral excavation and processing—especially limestone. On paper, it’s a strange pairing: a pharmaceutical giant digging rocks. But in the 1960s and 1970s, conglomerate logic was in full bloom. Big companies collected businesses the way investors collect index funds. Diversification wasn’t a distraction; it was a strategy. And for a pharma-and-chemicals company like Pfizer, specialty minerals didn’t feel as far afield as it sounds. It was still industrial chemistry, just with dustier inputs.

The breakthrough that would eventually define MTX came out of Pfizer’s labs in the early 1980s: precipitated calcium carbonate, or PCC, made the Pfizer way.

PCC is a synthetic mineral produced by reacting lime with carbon dioxide. Paper makers use it as a filler and pigment. The basic idea wasn’t new—PCC had long been understood as a way to replace some wood pulp and reduce reliance on other fillers like kaolin clay and titanium dioxide. The twist wasn’t the chemistry. It was the logistics.

In 1982, Pfizer kicked off its “satellite” PCC program. In 1986, it opened the first satellite PCC plant. The concept was deceptively simple: instead of making PCC at a central facility and hauling it—expensive, bulky, and not especially valuable per ton—Pfizer would build a small PCC plant right next to the customer’s paper mill. The plant was owned and operated by Pfizer’s specialty minerals division, and it fed PCC directly into the mill’s process.

For paper mills, the pitch was hard to resist. They didn’t have to build the plant themselves. They got reliable, just-in-time supply without tying up cash in inventory. And they signed long-term contracts that made their input costs more predictable.

For Pfizer, it created something even better than demand: lock-in. Once your PCC plant is physically embedded beside a paper mill and operationally integrated into how that mill runs, “switching suppliers” isn’t a simple procurement decision. It’s a disruption.

And the rollout was fast. Between 1986 and 1988, Pfizer built three more satellite plants. Then it hit the accelerator: by the end of 1990, Pfizer had 17 satellite PCC plants in operation. By the end of 1991—the last full year before the business left Pfizer—that number had reached 21. In 1992, another eight came online, the biggest single-year expansion since the satellite program began.

While PCC was compounding into a quietly great business, Pfizer itself was shifting. In the early 1990s, U.S. healthcare companies were bracing for what looked like a new era of regulation and reform. With the 1992 presidential election approaching and national healthcare policy at the center of the debate, Pfizer began tightening its focus—divesting operations that didn’t fit a future built around research-driven healthcare.

It started with the sale of its citric-acid business in 1990, and continued through a broader wave of divestitures. In that context, the specialty minerals division—worth $359 million of Pfizer’s 1991 sales—was an obvious candidate to spin out.

In August 1992, Pfizer announced it would sell the bulk of its stake in specialty minerals through a public offering in a newly created company: Minerals Technologies Inc.

To lead the new entity, Pfizer tapped Jean-Paul Vallès. French-born and raised in Normandy during World War II, Vallès had a family story shaped by the war—his father was a prisoner of war who escaped, and both parents became prominent figures in the French Resistance. Vallès later came to the U.S. for graduate school and built his career at Pfizer, rising through finance and executive leadership roles, including CFO and vice chairman. In the final years before the spin, he oversaw several Pfizer businesses, including the specialty minerals division itself.

When the separation became official, Vallès left his vice-chairman role at Pfizer to run Minerals Technologies and its three core lines of business.

In October 1992, the company began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker MTX. Minerals Technologies entered the world as an independent company with a powerful inheritance: a growing network of satellite PCC plants, a refractories operation, and a processed minerals business—plus a clear mission. Dominate paper coatings, and take the model global.

III. The Paper Years: Building the PCC Empire (1990s-2000s)

As a newly independent company, Minerals Technologies had one overriding mission: win paper.

At the start, the business was essentially two engines: precipitated calcium carbonate for paper, and refractory products for steel. Under its first CEO, Jean-Paul Vallès, MTX took the satellite PCC idea it inherited from Pfizer and turned it into a repeatable growth machine—building PCC plants right next to paper mills and embedding itself into customers’ day-to-day operations.

In commodity chemicals, that was a radical move. MTX wasn’t just selling a mineral; it was installing critical infrastructure inside a customer’s process. It looked less like a supplier relationship and more like a long-term partnership—almost an early version of “infrastructure as a service,” long before the phrase existed.

The logic was simple. PCC is heavy and relatively low value, which makes shipping painfully expensive. So MTX eliminated the freight bill by manufacturing on-site, then paired that with just-in-time delivery. And once a mill is fed by a plant that’s physically bolted to its production line, switching suppliers stops being a purchasing decision and starts becoming an operational crisis.

That lock-in wasn’t created by contracts alone. It was created by concrete and steel. MTX made the capital investment to build the satellite plant, and the mill got a modern PCC facility without putting up the money—typically in exchange for long-term purchase commitments that often ran about a decade. After that, the customer had every reason to keep the relationship steady. The plant was integrated, the product was tuned to the mill’s specs, and the alternative meant disruption.

Through the 1990s and early 2000s, MTX chased paper capacity wherever it moved—expanding across Asia, Europe, and South America. And as it scaled, it also built a deep bench of operators who knew how to replicate the model: Walter Nazarewicz, President of Specialty Minerals and often called the “Father of Paper PCC”; Paul Saueracker, who ran Paper PCC and would later lead the company; and John Sorel, who helped carry PCC into Europe, South America, and Asia.

Saueracker later put Vallès’ role plainly: “Jean-Paul Valles is really the ‘father’ of Minerals Technologies Inc.” He credited Vallès with taking the company public in 1992 and leading it through 2001, during which time sales grew from $394 million to $671 million—growth he attributed to Vallès’ vision, strategic insight, and business acumen.

By the mid-1990s, the flywheel was spinning. MTX was growing earnings at roughly the mid-teens annually, largely because PCC had changed how paper was made in North America—and MTX owned the playbook for delivering it.

And while PCC got most of the attention, MTX wasn’t a one-trick paper story. In the background, it kept building a second pillar: refractories.

Minteq, the refractories division, became a premier supplier of engineered refractory lining systems—monolithic refractories for iron and steel, non-ferrous metals, minerals processing, and glass. Alongside the materials, it paired application systems and measurement innovations designed to help customers run hotter, longer, and more efficiently.

Steel isn’t a “secular growth” end market. But it is a high-stakes one. Refractories protect furnaces and vessels from extreme temperatures, and when they fail, the consequences are brutal: lost production, damaged equipment, and massive downtime. That dynamic changes buyer behavior. Reliability and technical service matter as much as, or more than, price—exactly the kind of environment where a specialized supplier can earn sticky share.

Put together, the economics during this era were unusually attractive for an industrial business. Satellite PCC brought long-term contracts and visibility; many agreements included inflation protection that helped pass through cost increases; the co-location model was efficient because customers provided the site and utilities; and both PCC and refractories benefited from technical complexity and embedded relationships that weren’t easy to copy.

One especially important feature of the satellite PCC business was how those long-term contracts could smooth the ride. With ten-year agreements common, MTX was less exposed to the typical whiplash of the industrial cycle than most materials companies.

Over time, that focus built real leadership. In the Specialty Minerals segment—especially paper PCC—Minerals Technologies became the global leader, competing with players like Omya AG, Imerys S.A., and Schaefer Kalk. MTX’s advantage came from a familiar trio: proprietary know-how, the satellite plant footprint, and long-standing relationships with major paper manufacturers.

But even as MTX was perfecting its paper-coatings empire, the world outside the mill gates was changing. The internet was beginning to reshape how information moved, how ads were bought, and what people read. Slowly at first, then all at once, the foundation under paper demand began to shift.

The model that worked brilliantly for a decade was about to run into its defining problem.

IV. The Paper Problem: Inflection Point #1 (2008-2012)

In late 2008, the floor dropped out. As global financial markets seized up and credit froze, paper mills across North America went dark—some temporarily, many for good. The Great Recession didn’t create paper’s decline, but it brutally accelerated one that had been building for years. The internet was hollowing out print advertising. Email was replacing mail. Readers were moving to screens. Coated paper—the heart of MTX’s PCC machine—was becoming a melting ice cube.

And MTX didn’t just have a paper problem. It had a steel problem too.

In 2009, CEO Joseph C. Muscari spelled out what was happening on the refractories side:

"The downturn in the worldwide steel industry, which has resulted in nearly a 50-percent reduction in demand in the United States, our largest market, has had a severe impact on our Refractories operations," said Joseph C. Muscari, chairman and chief executive officer, in 2009. "We will consolidate operations and reduce our workforce in the Refractories business to meet this reduction in demand. We have also taken restructuring charges in our other businesses and support functions, which will allow us to operate more effectively at these lower levels of demand and will position Minerals Technologies to achieve greater profitability as the economic environment improves."

The performance followed the script you’d expect from a supplier tied to blast furnaces. Refractories sales plunged in 2009, volumes tracked the collapse in steel production, and the segment swung from profit to operating loss. At the company level, MTX posted a sizable net loss in the first half of 2009 as worldwide sales fell sharply year over year.

But the key distinction—what made this moment an inflection point instead of “just another cycle”—was paper. Steel would recover. Paper wouldn’t, at least not in the way MTX needed it to.

That showed up not just in earnings, but in the physical footprint of the business. In Refractories, MTX began consolidating operations: folding North American manufacturing in Old Bridge, New Jersey into Bryan, Ohio and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, rationalizing specialty shapes, tightening up European operations, and consolidating in Asia as well. This was classic downturn management—cut cost, protect cash, survive the trough.

In Paper PCC, the signals were darker. MTX recorded an impairment charge at its satellite PCC facility in Millinocket, Maine. The facility had been idle since September 2008, and restarting it was no longer likely.

Millinocket was more than an accounting line. It was a symbol of what was changing. The satellite model created incredible stickiness—until the mill itself disappeared. When a paper mill closes, the “switching costs” moat doesn’t just weaken. It evaporates.

So management started doing something MTX hadn’t truly needed to do before: look for a second act. Between 2010 and 2012, the company began making early moves beyond paper and steel, including acquisitions in specialty minerals and pet care. Those were directional signals—small steps pointing to a different MTX.

The real pivot, though, arrived in 2014.

Amcol International’s board accepted a $1.7 billion acquisition offer from Minerals Technologies. Amcol had previously agreed to a $1.6 billion takeover by France’s Imerys, which would receive a termination fee from Amcol. Amcol was a bentonite specialist with about $1.0 billion in sales.

For MTX, Amcol wasn’t a “tuck-in.” It was a statement. Minerals Technologies and AMCOL International Corporation announced a definitive merger agreement under which MTI would acquire AMCOL for $45.75 per share in cash, valuing the deal at approximately $1.7 billion.

This was enormous relative to MTX at the time. After recording about $1 billion of sales in 2013, MTX was effectively trying to transform itself by nearly doubling in size in a single, debt-financed leap.

On May 9, 2014, Minerals Technologies announced it had completed the acquisition. After a successful tender offer for all outstanding AMCOL shares, the remaining shares were acquired through a merger and AMCOL became a wholly owned subsidiary. As MTX put it: "Our combined company is now a more diversified, global leader in industrial minerals with strong market positions in both bentonite and precipitated calcium carbonate."

The logic came down to one word: bentonite.

Bentonite is a clay mineral with an almost unfair set of properties. It swells when wet. It absorbs odors. It can be processed into products that solve a wide range of problems across industrial and consumer markets. And, crucially for MTX’s reinvention, bentonite is the backbone of cat litter.

That mattered because pet care was moving in the opposite direction from paper. The category was growing, fueled by rising pet ownership and consumers spending more on their animals. Compared to the slow grind of paper decline, it was a rare thing for MTX: an end market with a tailwind.

The Amcol deal reshaped the company overnight. In 2014, MTX added new reporting segments, including Performance Materials—built around bentonite and bentonite-related products—and Energy Services, which provided oil-and-gas services aimed at improving production, costs, compliance, and environmental impact. The company now reported five segments: Specialty Minerals, Refractories, Performance Materials, Construction Technologies, and Energy Services, up from two previously.

It was, unambiguously, a make-or-break bet. The debt load was meaningful. Integration risk was real. And the central premise—that bentonite-driven pet care and other applications could eventually offset the long decline in paper—had to be proven in the field, quarter after quarter.

But this is the moment modern MTX came into view. It was no longer just a paper PCC company with a refractory business on the side. It was becoming a portfolio company—using cash flows from legacy strongholds to buy its way into the next set of growth markets.

As Muscari said at the time, "The combination of MTI and Amcol will create a minerals platform that is well-positioned for growth through geographic expansion and new product innovation."

V. Building the Performance Materials Portfolio (2013-2018)

The years after Amcol closed were less about big announcements and more about hard, operational work. MTX had absorbed a company nearly its own size. Now it had to stitch the pieces together—combining teams, rationalizing overlapping operations, taking out cost, and turning “synergies” from a slide into cash flow. It was the unglamorous part of transformation, and it took time.

Out of that integration, one opportunity quickly rose to the top: pet litter.

Amcol brought sodium bentonite, the clay that made modern scoopable, clumping litter possible. MTX’s pet litter products spanned scoopable (clumping), traditional, and alternative litters, sold through grocery and drug stores, mass merchandisers, wholesale clubs, and pet specialty channels across North America, Europe, and Asia. And the product advantage was simple to explain and easy for consumers to feel: clumping litter traps urine into removable clumps, so you throw away less and control odor better by removing only what’s causing it.

MTX leaned into the category with a strategy that fit its DNA: private label. Instead of spending heavily to build a consumer brand, MTX manufactured litter that retailers sold under their own names. That came with a few quiet advantages. Marketing spend stayed low. Retailer relationships got stronger, because MTX wasn’t trying to outshine its own customers on the shelf. And scale mattered—volume helped drive manufacturing and logistics efficiency in a business where the product is bulky and transportation is expensive.

That positioning also shaped how MTX competed. The market’s big branded players included The Clorox Company, with Fresh Step and Scoop Away, and Church & Dwight, with Arm & Hammer. MTX didn’t try to beat them by waging an advertising war. It aimed to win by being the best producer behind the retailers’ brands—capturing growth in pet care without paying the “brand tax.”

While Performance Materials was becoming the new growth story, MTX kept building its other pillar: refractories. The company expanded its footprint through acquisition, including Turkey-based ASMAS. As the chairman said at the time, "ASMAS has achieved rapid growth over the last four years and in addition to fitting well with our own refractories business, will provide an excellent platform for future growth. We expect the acquisition will be accretive to earnings per share."

The strategic fit was straightforward. Both Minteq International and ASMAS produced monolithic refractories used by steelmakers to protect the interior of steel-making vessels and molten metal handling equipment from extreme temperatures. It was the same play MTX had been running for years: sell mission-critical materials plus know-how into a demanding industrial process, then deepen the relationship through service and performance.

By this point, a clear acquisition playbook was forming. MTX looked for niche leaders with technical differentiation. It favored businesses that fit its mine-to-market strengths—mineral processing, formulation, and application expertise. It liked targets where it could push products into new geographies using MTX’s footprint. And it tried to keep discipline on price, because diversification only works if you don’t overpay for it.

At the same time, geographic diversification continued—partly by choice, partly by necessity. The goal was to reduce reliance on North American paper, without pretending paper would disappear overnight. In Specialty Minerals, MTX expanded Paper PCC capacity at existing satellites in Indonesia, South Africa, and Japan, while evaluating additional expansions with customers in the U.S., Europe, Latin America, and India. It built two additional Paper PCC satellites in Indonesia and pointed to a pipeline of new opportunities with paper makers worldwide.

Then, in 2016, leadership caught up with the strategy.

Douglas T. Dietrich became CEO in December 2016 and was later elected Chairman of the Board in March 2021. He brought decades of experience across industrial goods, mining, metals, and manufacturing. He joined MTX in 2007 and rotated through roles that put him at the center of the transformation—Chief Financial Officer, Senior Vice President of Finance and Treasury, and Vice President of Corporate Development and Treasury—where he helped lead corporate strategy and M&A.

As the company put it, "Doug has been with the company in senior leadership positions since 2007, and was deeply involved—along with our strong management team—in transforming MTI into a high-performing company. He is a strong business leader with a solid background in engineering, manufacturing, finance, general management and mergers and acquisitions."

His résumé matched what MTX needed next. Before MTX, Dietrich held leadership roles at Alcoa, including Vice President of Alcoa Wheel Products for Automotive Wheels, president of Alcoa Latin America Extrusions, and General Manager of Global Rod and Bar Products, producing specialty alloys for automotive and aerospace. He had the operator’s background—plants, processes, throughput—paired with the deal experience MTX increasingly relied on.

With a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Michigan and an MBA in Finance from Wharton, Dietrich was positioned to push the transformation into its next phase: moving faster away from paper dependence and deeper into businesses with better growth and margin potential.

VI. Inflection Point #2: The Sivomatic Deal & European Expansion (2018-2020)

By 2018, Dietrich and his team had a clear mandate: keep pushing MTX away from its legacy dependence on paper, and build businesses that could grow without needing a rebound in print.

In April of that year, MTX announced a deal that did exactly that—and did it overseas. Minerals Technologies entered into a definitive agreement with the shareholders of Sivomatic Holding B.V. to purchase all outstanding shares of the company.

Sivomatic was a vertically integrated, premium cat litter manufacturer in Europe, with production facilities in the Netherlands, Austria, and Turkey. It sourced bentonite predominantly from wholly owned mines and had built a leading position in high-end clumping litter. The business also came with history: a family presence in pet care going back to 1924. In 2017, Sivomatic generated €73 million in revenue with about 115 employees.

The acquisition closed on April 30, 2018. MTX paid approximately $120 million (about €100 million), at an EBITDA multiple of 7.4, and said the deal was accretive to earnings in 2018.

Dietrich framed Sivomatic as a clean fit with the company’s emerging playbook:

"Our focus has been on minerals-based companies, where we can leverage our technological expertise, provide growth in attractive markets, deepen our positions in existing markets or extend our core product lines to new geographies. Sivomatic meets all of these criteria. Sivomatic's had a long history of well-run company with an impressive track record of innovation and profitable growth, generating an 8% compound annual growth rate in revenue over the past five years."

With Sivomatic inside the portfolio, MTX didn’t just “enter Europe.” It suddenly had a serious European pet care platform—selling into 30 countries—and a stronger position in the premium segment of the market.

That mattered because this wasn’t a one-off, opportunistic bolt-on. It signaled the direction of travel: MTX was building a global pet care business with scale, mines, manufacturing, and product innovation—not merely harvesting cash from legacy PCC contracts while waiting for paper to shrink.

Operationally, 2018 was also a year of execution. MTX pushed further into Asia with Metalcasting and Paper PCC, commercialized 35 new value-added products, and integrated Sivomatic. Operational excellence efforts, continuous improvement, and pricing actions helped blunt the impact of inflationary costs. The results showed up most clearly in the consumer-facing portfolio: Household, Personal Care & Specialty Products sales rose 50 percent, driven by Sivomatic and continued growth in pet care products in China.

Then came COVID-19—and it stress-tested the strategy in real time.

The pandemic hit paper demand hard. Offices closed, commercial printing slowed, and the already-weak secular trend got worse. But the other side of MTX’s portfolio moved in the opposite direction. As people spent more time at home, household products and pet care held up—and in many cases surged. The diversification that had been painstakingly built through the 2010s suddenly looked less like a “future plan” and more like a shock absorber.

In 2020, that reality became explicit. MTX’s strategic review leaned further into de-emphasizing paper and concentrating on growth platforms. Investor messaging shifted with it: the company increasingly positioned itself as a technology-driven materials business serving both consumer and industrial markets, rather than a paper supplier that happened to own other operations.

And zooming out, you can see the through-line from the Pfizer spin in 1992 to this moment. MTX started by supplying essential minerals to paper, packaging, and steel. Over the decades—and especially through acquisitions—it evolved into a broader performance materials company anchored by two core minerals: bentonite and calcium carbonate, paired with manufacturing know-how and application expertise that let it compete on more than just tonnage.

VII. Portfolio Pruning and the Modern Structure (2021-2023)

By the early 2020s, MTX’s transformation wasn’t just about adding new legs. It was about tightening the whole machine—doubling down on what was working, and reshaping the portfolio so the company’s future wasn’t held hostage by paper.

On July 26, 2021, MTX announced the acquisition of Normerica Inc., a leading supplier of premium pet care products in North America. Normerica was founded in 1992, headquartered in Toronto, and had grown into a major producer and supplier of both branded and private label pet care products. Its portfolio was centered on bentonite-based cat litter, supplied through a network of manufacturing facilities across Canada and the United States. Normerica employed about 320 people and generated roughly $140 million in revenue in 2020.

Strategically, the fit was straightforward: Normerica strengthened MTX’s core position in cat litter in North America and extended the global pet care platform the company had been assembling since Amcol and Sivomatic.

Building on the legacy of American Colloid and Normerica, MTX continued to offer bentonite-based cat litter and all-natural dog treats under the SIVO brand—products positioned around quality, performance, and customer preference.

Execution followed the deal. In Q3 2021, MTX pushed forward on several growth projects, including integrating Normerica and acquiring Specialty PCC assets in the Midwest U.S. Management’s message was confident: “With our more balanced portfolio and the momentum we are generating with our growth initiatives, we have meaningfully changed the growth trajectory of our company heading into 2022.” Normerica contributed $20.0 million of sales that quarter, helping drive year-over-year growth.

Then, in early 2023, MTX made the organizational change that matched what had already been happening in the business. Beginning January 1, 2023, the company reorganized into two segments: Consumer & Specialties and Engineered Solutions. Consumer & Specialties covered technologically enhanced products aimed at consumer-driven end markets—mineral-to-shelf household products plus specialty additives used as functional ingredients across consumer and industrial goods. It included two product lines: Household & Personal Care and Specialty Additives. Engineered Solutions focused on advanced process technologies designed to improve customers’ manufacturing processes and projects, with two product lines: High-Temperature Technologies and Environmental & Infrastructure. As the company put it, “Minerals Technologies has transformed into a stronger, more resilient, and faster growing company.”

The performance in 2023 reinforced the point. MTX delivered a record year of sales, operating income, and earnings per share. Douglas T. Dietrich, Chairman and CEO, tied the results to the new shape of the company: “The realignment of our business segments with our key markets and core technologies highlights our balanced portfolio of consumer and industrial businesses. It also drives organizational efficiencies that lead to higher levels of performance. The combination of our leading business positions, continued margin expansion, and strong cash flow generation demonstrates the power of our business model.”

This wasn’t a cosmetic re-labeling. By consolidating into two coherent segments—one anchored in consumer-driven products, the other in industrial technologies—MTX was telling investors, customers, and its own employees that the paper-first identity was no longer the center of gravity.

And the portfolio itself showed it. Paper PCC, once more than 60% of revenue, had become a much smaller piece. In its place: pet care, environmental and infrastructure solutions, and high-temperature technologies tied to steelmaking—businesses that gave MTX a clearer path to growth than waiting for paper to come back.

VIII. The Three Platforms Today: What MTX Actually Does

At this point in the story, MTX isn’t best understood by what it used to be. It’s best understood by what it sells now—and why those pieces fit together.

Consumer & Specialties Segment

MTX’s Consumer & Specialties segment is the “mineral-to-market” side of the house: products that end up in everyday consumer categories, plus specialty mineral additives that act like functional ingredients inside other companies’ products. It’s organized into two product lines: Household & Personal Care, and Specialty Additives.

In Q3 2025, Consumer & Specialties sales were $277 million, flat sequentially and down 1% year over year.

Household & Personal Care is where the transformation is most visible. The center of gravity is pet care—especially cat litter—sold largely through private label relationships with major retailers. Under the SIVO umbrella, MTX positions itself as a global leader in both private label and branded cat litter, with an emphasis on customizable products that meet specific retailer and consumer preferences.

That pet care platform is also where MTX is putting fresh capital to work. The company expects its pet care investments to generate about $30 million in growth starting in 2026, with significant contracts already secured. It’s also expanding capacity in places where demand is running ahead of its footprint, including a 30% capacity expansion at its Turkey facility to support growth markets like renewable fuels and sustainable aviation fuel.

China is another example of the “follow the demand” playbook. MTX has outgrown its existing facility there and is bringing a new one online to meet demand in a rapidly growing pet litter market. Across three plants, upgrades were expected to be completed by the end of 2025—investments intended to reinforce MTX’s position as the largest high-quality private label cat litter supplier for customers around the world.

The second product line, Specialty Additives, is where MTX’s old strengths still show up. This is where precipitated calcium carbonate and ground calcium carbonate live—and where the legacy Paper PCC business still operates. The Paper PCC Group manufactures PCC globally using the satellite model: plants co-located at paper mills, plus regional merchant plants. The product itself does the unglamorous but essential work inside paper—boosting brightness, bulk, porosity, and smoothness, improving runnability and printability, and lowering overall cost.

Engineered Solutions Segment

If Consumer & Specialties is “minerals to shelves and formulations,” Engineered Solutions is “minerals plus technology in the field.” This segment sells process technologies and systems designed to improve customers’ operations, and it is organized into two product lines: High-Temperature Technologies and Environmental & Infrastructure.

In Q3 2025, Engineered Solutions sales were $255 million, up 2% sequentially and up 4% year over year.

High-Temperature Technologies is, in practical terms, the refractories business. MTX manufactures monolithic refractories for iron and steel, non-ferrous metals, minerals processing, and glass—then pairs those materials with application systems and measurement technologies meant to extend service life, reduce downtime, and lower the total cost of operating extreme-temperature equipment.

A flagship example is MINSCAN® LSC, an integrated refractory tool designed for steelmakers’ electric arc furnace needs. MTX described it as the world leader in real-time, automated EAF refractory maintenance.

And MTX isn’t just selling the technology—it’s building an installed base. By Q3 2025, the company had 12 Minscan® units installed with steel customers and planned to add six more over the next 12 months. The appeal is straightforward: meaningful operational value for the customer, and a recurring revenue stream for MTX.

Environmental & Infrastructure is the newer “needs-driven” platform: products that solve problems in containment, remediation, and water. It includes geosynthetic clay lining systems, PFAS remediation products, and water treatment solutions. In Q3 2025, Environmental & Infrastructure sales increased 5% sequentially to $76 million, driven by growth in offshore water filtration and services as well as infrastructure drilling products.

This product line includes organoclay and granular media used for PFAS remediation, geosynthetic clay liners, and sealing solutions for renewables and EV facilities. MTX’s plan here is explicit: double remediation revenues by 2026–2027 from a 2022–2023 base.

The Portfolio Logic

The strategic logic is cash funding change.

Paper PCC is no longer the center of the company’s identity, but it still throws off meaningful cash—even in decline. MTX uses that cash to pay for what comes next: expanding pet care capacity, building out environmental solutions, and continuing to invest in high-temperature technologies like Minscan®.

You can see the shape of that flywheel in the numbers MTX reported for 2024. Consumer & Specialties segment sales were $1.14 billion, up 2% over the prior year on an underlying basis. Household & Personal Care sales were $530 million, up 2%, driven by higher pet care and other consumer-oriented product sales. Specialty Additives sales were $610 million, up 1% on an underlying basis. Segment operating income was $166 million, up 17% year over year excluding special items, supported by lower input costs, improved pricing, and higher productivity. Operating margin, excluding special items, expanded by 230 basis points to 14.5% of sales.

IX. The Business Model & Competitive Positioning

Even after all the diversification, MTX’s original superpower still matters: the satellite plant model. It’s no longer the center of the growth story the way it was in the 1990s, but in the right situations it’s still a brutally effective advantage. When on-site production lowers total delivered cost and becomes physically embedded in a customer’s process, it creates the kind of stickiness competitors hate.

That was the breakthrough behind paper PCC. Starting in 1986, MTX’s decision to build and operate precipitated calcium carbonate plants directly at paper mills changed the relationship from “supplier” to “infrastructure partner.” It didn’t just win share; it raised the barrier to entry. Once a PCC plant is running next to your mill and tuned to your exact specs, ripping it out isn’t a procurement choice. It’s a manufacturing disruption.

Over time, that same logic has been extended into other applications where on-site production can create both cost and switching-cost advantages.

But MTX doesn’t win today simply by being close. Customers choosing specialty minerals and PCC suppliers increasingly care about the total package: lower overall cost, a smaller carbon footprint, consistent quality, and even digital integration—things like dosing systems and telemetry that make the mineral behave more like a managed input than a delivered commodity.

A big part of that comes from technology and R&D, not just geology. MTX’s R&D centers in the U.S. and Europe focus on engineered minerals, surface chemistry, and application systems, with annual spending near 1.5% to 2.0% of sales. Tools like FulFill and NewYield are designed to help customers get more out of their processes—optimizing fiber-to-filler ratios and converting ash into PCC in ways that reduce both cost and carbon intensity.

The “lock-in” looks different depending on which MTX business you’re talking about.

In PCC, it’s physical integration. The plant is on-site, tied into the mill, and optimized over time—switching is painful.

In refractories, it’s qualification and consequences. Steelmakers don’t casually swap refractory suppliers because failures are catastrophic and qualification processes are demanding. Once you’re proven, you tend to stay proven.

In pet care, it’s more commercial than technical. Private label relationships aren’t locked down by a piece of equipment bolted to a customer’s line; they’re held by dependable quality, scale, logistics, and cost position.

This is also why it’s a mistake to think of MTX as “just a mining company.” The minerals matter, but the premium comes from what MTX does to them: processing, formulation, crystal engineering, and application expertise that turns a rock into a performance material. The differentiation is in the know-how and the outcomes customers get, not the tonnage.

Under Doug Dietrich, capital allocation has been about making that premium bigger while keeping the balance sheet under control: investing organically in capacity and technology, doing tuck-in M&A at disciplined valuations, and paying down the debt taken on in the AMCOL deal. The company has framed its acquisition bar around tuck-ins that can deliver greater than 15% IRR, while keeping post-deal leverage around 2x to 3x net debt to EBITDA.

By Q3 2025, the balance sheet picture had improved. Total liquidity was $706 million, up from $556 million a year earlier. Net debt was $649 million versus $658 million in Q3 2024, putting net leverage at 1.7x EBITDA. Free cash flow was strong at $44 million for the quarter, up from $35 million in the prior-year quarter.

Finally, there’s a sustainability thread running through MTX’s technology roadmap that’s more practical than promotional. The company has built capabilities to capture CO2 within manufacturing processes and, using crystal engineering expertise, convert that CO2 into functional minerals. In high-temperature applications like steelmaking, its solutions are also aimed at helping customers reduce emissions. By MTX’s disclosure, 64% of its technology pipeline is tied to sustainability-focused innovations.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces Assessment:

Threat of New Entrants: Moderate

MTX doesn’t face one clean competitive landscape—it faces several, stitched together. In commodity minerals, the bar to entry can be surprisingly low: if you’ve got access to a deposit and you can process and ship reliably, you can show up on day one and start competing on price.

But MTX’s better businesses aren’t built like that. In specialty applications, “getting in” is the hard part. The satellite PCC model isn’t just a product you quote and ship; it’s a capital project, an operating system, and a long-term relationship embedded in a paper mill’s workflow. In refractories, the barrier is credibility earned over years of steel mill performance. In pet care at scale, you need plants, logistics, quality systems, and the kind of retail relationships that don’t materialize overnight. Across the portfolio, entry is possible—but in the places MTX cares most about, it’s not easy.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Low to Moderate

MTX’s results depend on securing the right inputs, reliably and at acceptable cost—lime and carbon dioxide for PCC, magnesia for refractories, and talc ore for processed minerals, plus access to the ore reserves tied to its mining operations. When those inputs get tighter or more expensive unexpectedly, the impact can show up quickly.

The good news is MTX isn’t helpless. It owns meaningful mineral reserves, especially bentonite, which gives it more control than a pure “buy-and-process” competitor. But for other inputs—energy in particular—it’s often a price-taker. Contract structures can help pass through some of that pressure, but energy and other volatile costs still matter.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Moderate to High

Historically, a large share of MTX’s business was tied to two customer groups: paper manufacturers and steel producers—both cyclical industries with plenty of reasons to push back on price. Over time, MTX reduced some of that exposure through diversification, more operating sites, and geographic expansion.

Even so, buyer power remains real, and it varies by segment. Paper customers are shrinking in number, which can reduce their leverage—but they’re intensely cost-focused, and they’re not exactly investing for growth. Steel customers are often consolidated and sophisticated, with the negotiating muscle to demand concessions, even if refractory qualification and performance risks limit how casually they can switch. In pet care, the balance of power is often tilted toward the retailer: in private label, big accounts like Walmart and Amazon can pressure suppliers hard. Meanwhile, specialty applications spread across a wider set of end markets tend to have less concentrated buyer power and more room for value-based selling.

Threat of Substitutes: Varies by Segment

In paper PCC, the substitute isn’t another filler—it’s the disappearance of demand as reading and advertising moved to digital. That’s the existential substitution that forced MTX’s reinvention in the first place.

Elsewhere, substitutes are more traditional. In pet litter, silica and plant-based alternatives exist, but bentonite remains the standard because it clumps well and controls odor. In refractories for steelmaking, there’s no practical substitute: if you want to run high-temperature equipment safely, you need refractory systems. In specialty minerals, substitution risk depends on the application, but it’s usually low to moderate and tends to play out over long cycles of qualification and reformulation.

Competitive Rivalry: Moderate to High

Competition is a constant, but it doesn’t always look the same. In specialty minerals, MTX faces capable global players like Omya and Imerys, plus a long tail of regional competitors depending on the product and geography. In some categories, the market is fragmented and local. In others, it’s a global knife fight among a few scaled operators.

And importantly, rivalry isn’t just about price. Service reliability, consistent quality, technical support, and proximity to customers often decide who wins. Industry consolidation can help MTX by raising the scale required to compete—but it also means the remaining competitors are larger, better financed, and harder to out-execute.

Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis:

Scale Economies: Moderate

Scale helps in parts of the portfolio. Refractories benefits from a global footprint when steel customers operate across regions and want consistent performance. Pet care manufacturing also rewards scale through production efficiency and freight optimization in a bulky product category.

But PCC satellites are different. The whole point is local production sized for one customer. That creates powerful local economics, but it doesn’t compound into the same kind of global scale advantage.

Network Effects: None

There’s no network effect here. A steelmaker doesn’t get extra value because other steelmakers use MTX, and a retailer doesn’t benefit because other retailers buy from the same private label supplier.

Counter-Positioning: Low

MTX isn’t undermining an incumbent model with a radically different one. The satellite PCC concept was a genuine innovation decades ago, but the industry has had time to adapt around it. Today the playbook is less about disruption and more about steady, operationally excellent execution.

Switching Costs: Moderate to High

This is MTX’s most reliable “power,” and it shows up differently by business. PCC customers face high switching costs because the supply is physically integrated through satellite plants and tuned to tight specifications. Refractories customers face high switching costs because qualification is demanding and failure is expensive. Pet care is looser—retailers can change private label suppliers more readily, even if quality and logistics still create friction. Specialty minerals often land in the middle: stickiness comes from application-specific development and the risk of changing formulations.

Branding: Low

MTX isn’t built on consumer brand equity. In refractories, there’s professional reputation, but that’s not the same as a brand moat. And in pet care, the strategy is explicitly private label—by design, the retailer owns the brand.

Cornered Resource: Moderate

Owning strategic deposits helps, and long-term contracts with paper mills were once a meaningful advantage, even if that asset has been fading with paper’s decline. Technical know-how and patents in specialty applications add defensibility, but they’re not permanent—competitors can often replicate capabilities over time with enough investment.

Process Power: Moderate

MTX has decades of accumulated operating expertise: running PCC plants, installing and servicing refractories, improving yields, and tightening manufacturing consistency. The original decision to build PCC plants on-site at paper mills created an enduring capability set that’s hard to copy quickly. But it’s still advantage earned through learning curves and execution discipline—not an unassailable structural lock.

Overall Assessment:

MTX’s most durable advantages are concentrated in switching costs (especially PCC and refractories) and process power (the know-how built through decades of operating and improving these systems). Strategically, the company has been trading a declining, high-switching-cost business (paper PCC) for growth platforms that often have weaker structural lock-in (like pet care and broader specialty minerals), while keeping refractories as another sticky, mission-critical anchor.

That’s solid portfolio management—and it’s worked. But in Hamilton’s framework, it’s less about creating a new “power moat” and more about continuously reshaping the mix so the company can keep compounding even as the old foundation erodes.

XI. The Investment Thesis & Strategic Challenges

The Bull Case:

MTX has pulled off one of the more compelling transformations in industrial materials: a company that once lived and died with paper has steadily rebuilt itself around a broader set of end markets, where consumer products, environmental solutions, and high-temperature technologies are increasingly doing the heavy lifting.

That shift has started to show up in results, not just narrative. For the third quarter ended September 28, 2025, MTX reported earnings per share of $1.37, or $1.55 excluding special items—its best third quarter on record. The company also reported a 24% year-over-year increase in cash flow and announced a 9% increase in its regular quarterly dividend, the third straight year it raised the payout.

The bull argument is that MTX is doing exactly what you want a portfolio transformer to do: use cash-generative legacy businesses to fund growth investments. Pet care and specialty minerals have tailwinds—from premiumization, from remediation demand, and from applications tied to packaging and other durable categories. And because the company still gets valued like a more traditional industrial, there’s a case that it’s undervalued relative to the “specialty chemicals” attributes it’s built into the mix.

Add in a management team with a demonstrated M&A and integration playbook, and you get a plausible path for continued reinvention. If steel demand improves and infrastructure spending holds up, refractories can participate. And if paper becomes small enough to stop dominating investor perception, there’s potential for multiple expansion as the story gets cleaner.

The Bear Case:

The bear case starts with the same fact the bull case wants to move past: paper may be smaller than it used to be, but it’s still a meaningful profit contributor. Running a declining business for cash while simultaneously investing in growth is harder than it sounds. It creates operational tension and can punish mistakes.

Refractories add another layer of risk. It’s a strong franchise, but it remains exposed to steel cycles—and to China dynamics that are notoriously difficult to forecast and impossible for MTX to control.

Then there’s pet care. Private label is a great strategy when retailers want value and reliability. But it can be a tough place to live when branded competitors decide to get aggressive. If players like Clorox or Church & Dwight discount heavily, pressure tends to flow downhill through retailer negotiations, and private label manufacturers can feel it quickly.

Even management’s own outlook underscored that near-term performance won’t be a straight line. Looking ahead to the fourth quarter, MTX guided to sales between $510 million and $525 million and operating income between $65 million and $70 million—down sequentially from Q3—implying earnings per share of $1.20 to $1.30. The company pointed to seasonally slower construction activity, softer residential construction markets, and foundry customers planning longer year-end downtime. It also cited renewed uncertainty around tariff policies as a potential headwind.

Finally, the strategy itself has constraints. An acquisitive model needs continued deal flow at reasonable prices, and that’s tougher when private equity and strategic buyers are competing for the same high-quality assets. Leverage limits how big MTX can swing. And because most of its markets don’t have winner-take-all dynamics, the company is often winning through execution, not inevitability—playing for inches rather than miles. Layer in integration complexity from multiple acquisitions, plus ESG and permitting considerations in mining-heavy operations, and the bear case is essentially: this is a well-run company, but it’s not a simple one.

Key Metrics to Monitor:

For investors tracking MTX, two metrics warrant particular attention:

-

Consumer & Specialties Operating Margin: This segment represents the growth future of the company. Margin expansion here—targeting 15%+ operating margins—would indicate that the higher-growth businesses can deliver profitability to match their revenue growth. Watch for progress toward the 15% operating margin target management has discussed.

-

Segment Revenue Mix: The ratio of Consumer & Specialties revenue to total revenue tracks the progress of portfolio transformation. Currently approaching 55% of the total, continued movement toward 60%+ would signal successful execution of the strategic pivot away from paper and toward consumer-oriented businesses.

XII. Lessons & Playbook

The Conglomerate Spinoff Playbook

MTX’s origin is a reminder that spinoffs don’t start from zero—they start with baggage. Minerals Technologies came out of Pfizer with real advantages: assets, customer relationships, and a hard-earned operating playbook. But it also inherited the harder problem: identity. As a division, it could be “Pfizer’s minerals group.” As an independent public company, it had to decide what it was going to be.

That’s what the first decade under Jean-Paul Vallès was really about. MTX didn’t try to reinvent itself on day one. It took the strengths it already had—especially the PCC satellite model—and turned them into a focused strategy that could stand on its own.

Portfolio Transformation

Knowing when to hold and when to fold is one of the most unforgiving calls in business. MTX held on to paper PCC longer than some critics wanted. But it didn’t do it out of denial. It did it to harvest cash and fund the next portfolio before the old one fully faded.

The key here is pace. MTX didn’t rip the bandage off with a sudden pivot that risked breaking the machine. It executed a gradual transformation that kept the company stable enough to invest, acquire, and integrate—without the whiplash that comes from trying to change everything at once.

Niche Dominance

MTX’s story also reinforces a simple truth: being dominant in boring markets can be a great business model. The company isn’t competing in venture-backed, headline-grabbing sectors. It wins in technical niches where consistency, process know-how, and long customer relationships matter more than advertising budgets or “platform” narratives.

In those markets, a quiet #1 or #2 position can be far more valuable than a loud “innovator” label.

The Satellite Model

The satellite model is a masterclass in creating switching costs the old-fashioned way: with concrete, pipes, and integration into a customer’s workflow. By building PCC plants right next to paper mills and running them as part of the mill’s daily operation, MTX turned a basic mineral into embedded infrastructure.

It’s the industrial version of “sticky.” Not because customers loved a brand, but because switching meant operational pain. In a lot of ways, it was infrastructure-as-a-service decades before anyone used that phrase.

Responding to Structural Decline

The paper pivot is a case study in handling secular decline without panicking—or pretending it isn’t happening. MTX recognized that paper demand wasn’t just cyclical, it was structurally eroding. Then it did the hard thing: it started reallocating capital methodically toward businesses with better long-term end-market dynamics.

The AMCOL acquisition was the hinge. Bold, debt-financed, and strategically transformative, it gave MTX a path to outrun the decline instead of simply managing it.

Acquisition Integration

M&A can buy revenue. It can’t automatically buy a better company. MTX’s success with AMCOL, Sivomatic, and Normerica points to the less glamorous skill that actually matters: integration. Combining operations, aligning teams, protecting what made the asset valuable, and then improving it—without smothering it.

That’s not about deal-making flair. It’s about operational discipline.

Capital Allocation in Transition

Transformation is expensive. You’re investing in growth while a legacy business is shrinking, and you’re often doing it with a balance sheet that can’t afford mistakes. MTX’s balancing act—funding organic growth and tuck-in acquisitions while managing the debt taken on in its big pivot—highlights how central capital allocation becomes when the company is in motion.

In transitions like this, the winners aren’t the ones who make the biggest bets. They’re the ones who can keep investing without losing control of the fundamentals.

XIII. Epilogue: The Future of Materials

So where does MTX go from here? The company’s next moves are already on the board: keep expanding pet care capacity, scale Environmental & Infrastructure—especially PFAS remediation—and defend its leadership position in high-temperature technologies.

Doug Dietrich has said the investment program in North America and China is meant to carry the business for the next five to ten years. The new China facility was designed with modular expansion in mind, while North American sites have been upgraded to improve quality and lower costs. The point of all that concrete and steel is simple: win better contracts. Management expects about $30 million of growth to begin showing up starting in the second quarter of next year.

Turkey is another tell. Dietrich has pointed to a roughly $9 million to $10 million project to expand capacity there by about 30% to meet growing demand—particularly tied to renewable fuels. The site has bentonite reserves expected to last for decades, and the company has left the door open to further expansion if the market keeps pulling.

Zoom out and the opportunity set gets even broader. EVs, batteries, semiconductors, sustainability—these are markets where materials science, crystal engineering, and mineral processing can matter as much as software. The open question is whether MTX can translate the capabilities it built in paper and pet litter into the next generation of applications—green steel, circular-economy infrastructure, and advanced materials that didn’t exist when this company was born.

That’s also where the central tension remains: cash generation versus growth investment. MTX still throws off meaningful cash from mature businesses, but the best growth platforms require continued capital—plants, capacity, R&D, and commercialization. The job is to thread the needle: don’t starve the future, and don’t chase growth projects that can’t earn their keep.

If you’re watching from the outside, a few indicators matter most: paper exposure continuing to trend down; pet care margins moving toward the company’s 15% operating margin goal; refractories improving with steel production and infrastructure activity; and Environmental & Infrastructure building real momentum, particularly in PFAS remediation.

The lasting surprise in the MTX story is what the company became. A Pfizer spinoff built to supply paper mills ended up as a portfolio bet on cat litter, steel furnaces, and environmental remediation—proof that survival in industrial markets often comes down to adaptability. As Dietrich put it, "Minerals Technologies is a global specialty mineral company, so we mine and process minerals around the world. And we supply them to things that I don't think many people in the world know that they even exist."

Thirty-three years after its IPO, Minerals Technologies is still a hidden champion: essential to modern manufacturing, invisible to most consumers, and still evolving—long after Jean-Paul Vallès rang the opening bell in October 1992.

XIV. Further Reading & Resources

Key Resources:

- MTX Investor Relations & Annual Reports - The closest thing to a primary source: filings, earnings calls, and the company’s own telling of the transformation

- "The Alchemy of Air" by Thomas Hager - A great bridge into why industrial chemistry and “invisible” materials innovations can reshape entire industries

- Imerys and specialty minerals industry reports - Helpful context on how specialty minerals markets work and who MTX competes with

- "The Outsiders" by William Thorndike - A framework for thinking about capital allocation, the skill that ultimately determines whether portfolio transformations compound or stall

- Paper industry decline analysis - Background on the secular shift that forced MTX’s pivot and why paper never “cycled back” the way steel did

- Pet care industry reports (Packaged Facts, Euromonitor) - Useful for understanding category growth, premiumization, and private label dynamics

- Steel industry and refractories technical publications - The best way to appreciate why refractories are mission-critical, and why qualification and reliability matter so much

- Bentonite and specialty minerals geology resources - The “why” behind the raw materials: where these minerals come from and what makes them valuable

- "Hidden Champions" by Hermann Simon - The playbook for companies like MTX: quiet category leaders with deep capabilities in unglamorous markets

- Industrial M&A case studies - Comparisons to other portfolio shapers (Danaher, ITW, etc.) and a lens on how transformations are actually executed

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music