MACOM Technology Solutions: The Story of a Semiconductor Survivor

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Inside the warehouse-sized data centers that answer your AI prompts, inside the radar systems scanning contested skies, and inside the fiber links that shuttle the internet across oceans, there’s a shared dependency: small, stubbornly hard-to-make chips that turn physics into performance. Many of them come from a company most people have never heard of.

That company is MACOM Technology Solutions (NASDAQ: MTSI). And its story reads like a minor miracle in an industry that eats the undisciplined alive: a roughly seventy-five-year run from Cold War defense supplier to a behind-the-scenes enabler of the cloud and AI era.

As of November 2025, MACOM’s market cap is $13.06 billion—about the world’s 1,589th most valuable company. Not exactly a household name. But here’s what that number hides: MACOM designs and manufactures the analog RF, microwave, millimeter-wave, and photonic semiconductors that make modern connectivity work.

When your phone hits a 5G base station, there’s a good chance a MACOM chip is in the signal chain. When a military radar system detects and tracks a threat, MACOM components are often doing the high-frequency heavy lifting. And when hyperscale data centers at companies like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon move oceans of data between racks, MACOM’s optical interconnect technology helps push those bits through.

So the question driving this episode is simple to ask and hard to answer: How did a company that started as a defense contractor in the 1950s become a critical player in the cloud infrastructure revolution?

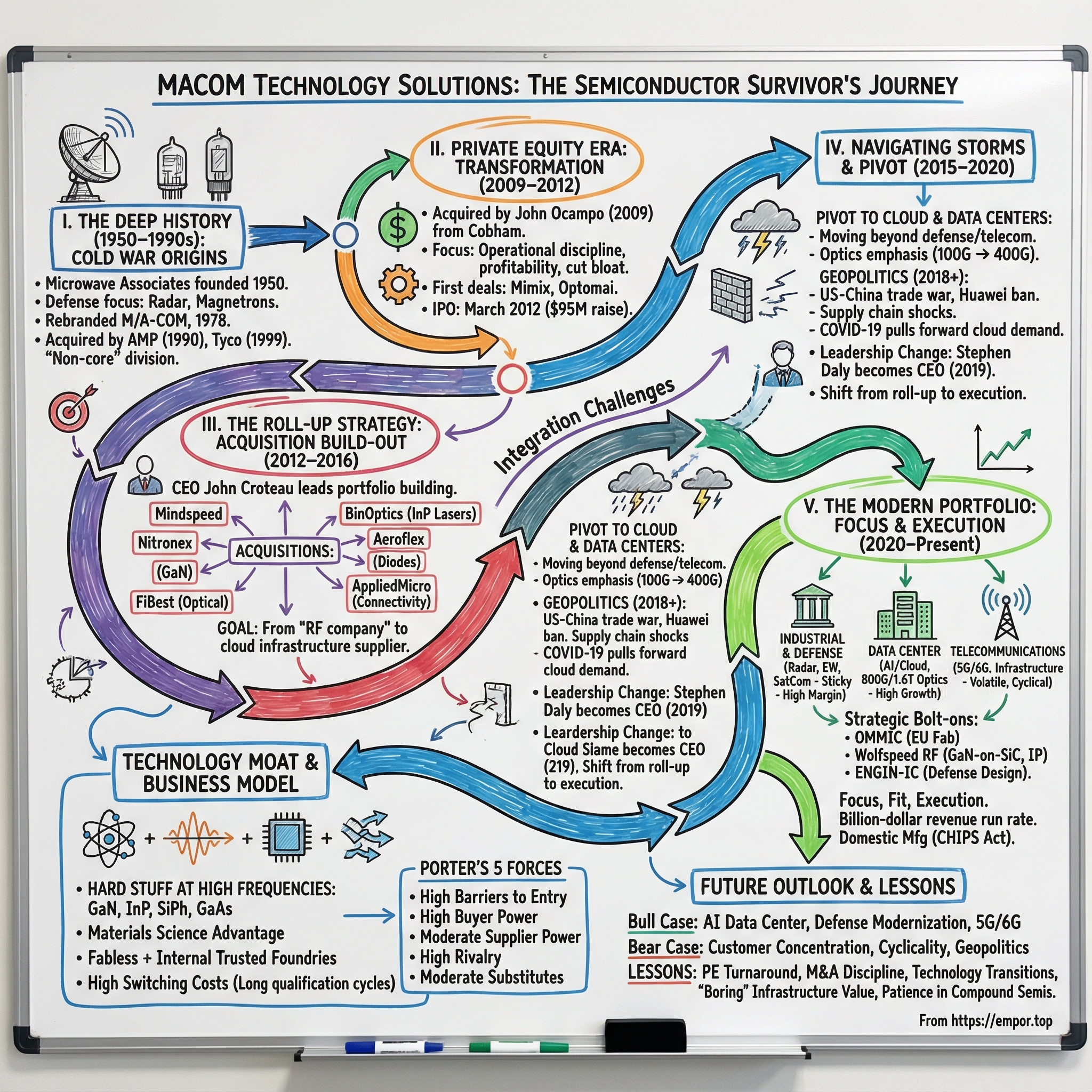

The path runs through five inflection points that repeatedly rewired MACOM’s identity: a private equity buyout during the financial crisis, an aggressive acquisition-led roll-up, a pivot toward cloud data centers, a bruising stretch of US–China geopolitical shockwaves, and a more recent narrowing of focus that helped push MACOM to a billion-dollar annual revenue run rate for the first time.

What makes MACOM such a compelling case study is that it’s “picks and shovels” investing in the most literal sense. No consumer brand. No viral product launches. No founder mythos. Just deep engineering—solving messy analog problems where the constraints are real, the tolerances are unforgiving, and the wins are earned one design-in at a time. The company spans radio frequency, microwave, millimeter-wave, and photonic technologies, operating primarily with a fabless model while still keeping some internal fabrication capabilities for the areas where control matters.

For investors and operators, MACOM is a window into the part of semiconductors that doesn’t get the spotlight: the analog and RF world where software can’t hand-wave away the laws of physics, where customer relationships take years to build, and where a single hard-won socket can turn into a durable, multi-year revenue stream.

This is a story about survival, transformation, and capital allocation—about how an “invisible” company found defensible niches, rode the right waves, and stayed standing in one of the most brutal businesses on earth.

II. The Deep History: Microwave Associates & Cold War Origins (1950–1990s)

Picture Boston in the summer of 1950. World War II had ended just five years earlier, and radar had proven it could change the outcome of a conflict. Four engineers—Vessarios Chigas, Louis Roberts, Hugh Wainwright, and Richard Walker—were working at Sylvania Electric Products and watching a new industry form in real time: defense electronics. In August, with just $10,000 to get started, they founded Microwave Associates in Boston. Their specialty was microwave components—especially magnetrons, the kind used in military radar systems for the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

They couldn’t have picked a better moment. The Cold War was hardening into policy, budgets were flowing into radar, communications, and surveillance, and the U.S. military needed suppliers that could deliver reliable, high-performance hardware. Microwave Associates aimed squarely at that demand. Early on, the company’s growth was driven by defense contracts and the simple reality that, in radar, the components either work or they don’t.

Success forced a move. By the late 1950s, the company outgrew its original space and relocated to Burlington, Massachusetts. It went public in 1961. And in 1978, it rebranded as M/A-COM, Inc.—a change that wasn’t just cosmetic. That same year, the company merged with Digital Communications Corporation, signaling a deliberate push beyond defense microwave components and into telecommunications.

Across the 1960s and 1970s, M/A-COM built the technical foundation that still defines MACOM today: deep, hard-earned expertise in analog semiconductors and RF technology. Not the digital logic that runs your apps, but the kind of engineering that wrestles with the real world—noise, interference, heat, and the stubborn laws of physics that govern signals moving through air and along wire.

Then came the corporate reshuffling. Over the following decades, M/A-COM changed hands multiple times as consolidation swept through defense and electronics. It was acquired by AMP Inc. in 1990, and when Tyco Electronics emerged in 1999, M/A-COM became part of that portfolio too—another business inside a much larger machine, subject to shifting priorities and rotating leadership.

By 2008, the breakup accelerated. On May 13, 2008, Tyco Electronics announced it would sell its RF Components and Subsystem Business to Cobham plc for $425 million. Tyco kept the wireless communications portion of MACOM, renaming it Tyco Electronics Wireless Systems. On September 29, 2008, Tyco and Cobham announced the sale had closed.

This ownership carousel can read like corporate trivia, but it mattered. By 2009, the company that would become modern MACOM had spent years as someone else’s “non-core” division—useful, but not beloved. That’s how you end up with a bloated cost structure and a culture that’s learned to coast. But it also meant something else had survived intact underneath: serious technical capability, long-standing customer relationships, and IP built up over more than half a century. All it needed was an owner who would treat it like a platform, not a leftover.

III. The Private Equity Era: Goldman Sachs Transformation (2009–2012)

March 2009 was a strange moment to go shopping.

The global financial system was still in triage. Lehman had collapsed just six months earlier. Credit markets were locked up. Most private equity firms were busy protecting what they already owned, not trying to buy new assets.

But for John Ocampo, this was exactly when deals appeared that wouldn’t exist in normal times. Ocampo wasn’t a spreadsheet-only investor. He had co-founded Sirenza Microdevices, taken it public, and sold it to RF Micro Devices. He knew RF semiconductors from the inside: how hard they are to build, how long design cycles take, and how sticky the best customer relationships can be. So when Cobham—fresh off acquiring M/A-COM as part of a larger transaction—moved to offload M/A-COM Technology Solutions, Ocampo saw a platform hiding in what looked like a castoff.

Ocampo acquired MACOM from Cobham in 2009 and ultimately led the company through the IPO process in March 2012. He also served as co-founder and President of GaAs Labs, LLC, a technology investment company. Under his leadership, MACOM began to reintroduce itself to the market as a serious supplier across Industrial and Defense, Telecommunications, and Data Center customers.

But the real change wasn’t branding. It was posture.

Ocampo brought more than capital—he brought operating instincts and a clear idea of what had to happen next. The playbook was private equity in its most effective form: bring in leadership that would run the business like it mattered, cut what didn’t create value, and rebuild the organization around profitability and execution rather than the slow comfort of being a “non-core” division inside someone else’s conglomerate.

Charles Bland became Chief Executive Officer in February 2011 and served until December 2012. Before that, he served as Chief Operating Officer from June 2010 to February 2011, and after retiring he stayed on in a transitional capacity.

Inside the company, the cultural shift was unmistakable. Complacency gave way to urgency. Cost bloat turned into accountability. And with a cleaner operating model, MACOM could finally do what a standalone semiconductor company needs to do to win: invest with intent.

You can see that intent in the first deals.

In May 2010, MACOM acquired Mimix Broadband, a fabless supplier of GaAs semiconductors. In May 2011, MACOM acquired Optomai Inc., which developed integrated circuits and modules for forty and one hundred gigabit per second fiber optic networks.

These weren’t random bolt-ons. They were signals. MACOM was starting to widen its aperture from its defense roots toward commercial telecom and the early build-out of optical networking—markets that rewarded exactly the kind of RF and high-performance analog expertise the company already had, but on a much bigger commercial stage.

Then came the moment that made all of this durable: the IPO.

On March 15, 2012, MACOM went public, raising about $95 million in capital. That funding gave the company the ability to keep expanding—and, crucially, to keep acquiring—on its own terms.

In just three years, MACOM went from a business that had been passed around between corporate parents to an independent, publicly traded semiconductor company with a sharper cost structure, a clearer strategy, and real ammunition for growth. Ocampo retained significant ownership and remained Chairman, keeping the vision intact. And the stage was set for what came next: one of the more aggressive acquisition runs in the sector.

IV. The Roll-Up Strategy: Building Through Acquisition (2012–2016)

The IPO didn’t just give MACOM capital. It also triggered a leadership handoff that would define the next chapter.

In December 2012, the board promoted John Croteau—then the company’s President—to CEO, effective December 13. He’d only been President since October, but he wasn’t a lightweight. He came from NXP Semiconductors, where he ran the High Performance RF business, and before that he’d spent years inside Analog Devices in product and general management roles. He understood the uncomfortable truth of semiconductors: great technology isn’t enough. You need distribution, scale, cost discipline, and a portfolio that makes customers want to buy more than one thing from you.

Croteau’s tenure would be defined by exactly that kind of portfolio-building. And the timing was perfect. The analog and RF world was still fragmented—lots of capable specialists, lots of duplicate overhead, and not enough scale at many of them to keep up with rising R&D demands. Consolidation was coming. MACOM’s bet was that it didn’t have to be a victim of that wave. It could be one of the companies creating it.

The first big proof point arrived with Mindspeed Technologies. In November 2013, MACOM announced a deal to buy Mindspeed, a network infrastructure semiconductor business. Then, in February 2014, MACOM turned around and sold Mindspeed’s wireless business to Intel.

That detail matters. This wasn’t “buy everything and hope it works out.” MACOM was already acting like a disciplined operator: acquire what fit the direction of travel, and carve out what didn’t. Selling the wireless piece to Intel helped shrink the effective cost of the transaction while keeping the parts that strengthened MACOM’s networking and optical ambitions.

Only days later, MACOM made another move—this time into a technology that would become foundational.

On February 13, 2014, MACOM acquired Nitronex, a privately held gallium nitride semiconductor company, for $26 million. The attraction was process technology: GaN-on-silicon epitaxial and pendeoepitaxial approaches that promised high performance with a cost structure that could reach mainstream, higher-volume markets. Nitronex had already pushed the industry with early GaN-on-silicon RF discrete devices and MMICs, combining GaN’s power and efficiency with easier integration.

In hindsight, this was one of those quiet acquisitions that ends up echoing for a decade. GaN’s high output power, efficiency, and linearity make it tailor-made for the hardest RF jobs—defense, radar, electronic warfare, and eventually 5G infrastructure. MACOM wasn’t waiting for the wave to crest. It was stocking up on surfboards early.

Then came optics.

In November 2014, MACOM agreed to buy BinOptics for $230 million. BinOptics, born out of Cornell University, made indium phosphide lasers—key building blocks for high-speed optical links. This was MACOM planting a flag beyond its traditional RF identity, into the photonics supply chain that would soon power data center interconnects.

The buying didn’t slow down. In November 2015, MACOM announced plans to acquire FiBest Limited, a Japanese optical subassembly supplier, before the end of the first quarter of 2016. In December 2015, MACOM acquired Aeroflex Metelics—Aeroflex’s diode business—from Cobham for $38 million in cash.

Step back and the pattern becomes clear. Each deal filled a gap: GaN to strengthen high-power RF, InP lasers to push into optical transmission, optical subassemblies to improve integration capability, and diodes to deepen the RF portfolio. The strategy wasn’t to be a clever component vendor. It was to become a more complete, more essential supplier into telecom and data center systems.

And then MACOM swung for the fences.

The company entered into a definitive agreement to acquire Applied Micro Circuits Corporation, or AppliedMicro, valuing the deal at roughly $770 million. The offer was structured as about $8.36 per AppliedMicro share—$3.25 in cash plus 0.1089 MACOM shares—representing a premium to AppliedMicro’s then-recent trading price. MACOM also said, upfront, that it intended to divest AppliedMicro’s Compute business within the first 100 days after the deal closed.

The market got the message: this was a connectivity-and-cloud infrastructure play, not a bet on owning a processor company.

MACOM announced the AppliedMicro deal in November 2016, completed the acquisition on January 26, 2017, and then—consistent with the original plan—sold the processor division to The Carlyle Group in October 2017.

On paper, the upside was massive. AppliedMicro brought technology and positioning in areas like MACsec, and in the march from 100G to 400G single-lambda PAM4—exactly the kind of plumbing hyperscale and enterprise data centers were adopting as bandwidth demands exploded. If MACOM could integrate it well, it could move from being “an RF company” to being a preferred connectivity supplier to the companies building the modern cloud.

But this is the part of the story where the easy narrative breaks down. Serial acquisition strategies don’t fail because the targets are bad. They fail because integration is hard.

MACOM was now trying to digest multiple businesses, reconcile cultures, rationalize overlapping product lines, and execute on ambitious roadmaps—all while carrying the financial weight of doing deals at this pace. The question that haunts every roll-up was now unavoidable: could MACOM turn a stack of acquisitions into a coherent machine, or was it just assembling a pile of parts?

V. The Pivot to Cloud & Data Centers (2015–2018)

By the mid-2010s, the center of gravity in networking was moving—and it wasn’t subtle. The biggest buyers of bandwidth were no longer traditional carriers planning upgrades in multi-year cycles. It was the hyperscalers: Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft. They built at a different tempo, pushed specs harder, and increasingly shaped the supply chain around their own architectures. If you wanted to ride the next wave, you had to win inside the data center.

That wave had a very specific bottleneck: moving data fast enough between servers, switches, and storage. Copper was running out of runway. Optics—100G, then the march toward 400G—was the escape hatch. And it required a different kind of semiconductor portfolio than MACOM’s historical RF roots.

This is where the earlier acquisitions start to look less like a shopping spree and more like a deliberate re-platforming. BinOptics brought indium phosphide lasers. FiBest added optical subassemblies. AppliedMicro added connectivity know-how aimed directly at cloud infrastructure. Along with earlier optical bets like Optomai and the networking assets from Mindspeed, MACOM was assembling the pieces needed to compete in high-speed optical links.

The product focus narrowed to the components that make optical interconnects work in the real world: lasers that generate the light, modulators that encode data onto it, and the electronics on the receive side that pull faint optical signals back into clean electrical ones. That last job is where transimpedance amplifiers—TIAs—come in. They’re not glamorous, but they’re critical. If your TIA is noisy, slow, or power-hungry, the entire link suffers.

Of course, having the right parts isn’t the same as getting them into the racks.

Winning hyperscalers is its own kind of battle. These customers don’t “try” components the way consumers try gadgets. They qualify suppliers through exhaustive testing, reliability screening, and long, technical design cycles. The process can take years, the requirements are unforgiving, and pricing pressure is constant. But the prize is enormous: once you’re designed in, you tend to stay there. The switching costs are real, and a single design win can translate into years of production demand.

And MACOM wasn’t alone in chasing those sockets. Finisar, Lumentum, II-VI, and other established optical players were fighting for the same positions, and every generation shift was a fresh knife fight for share.

Meanwhile, MACOM had another problem to manage: its own success on the legacy side. The industrial and defense business was profitable and dependable, but it didn’t grow like cloud. Data center was the opposite—huge potential, tougher competition, and typically lower margins early on. The pivot required discipline: pruning non-core product lines, concentrating R&D, and accepting that the portfolio would look different on the other side.

It also wasn’t painless. Some acquisitions were harder to integrate than expected. The pace created execution pressure. And as the market watched MACOM stack deal on top of deal, patience started to hinge on one thing: could this expanded toolkit turn into sustained cloud-driven growth fast enough to justify the strategy?

VI. Navigating the Storms: China, Huawei, and Geopolitics (2018–2020)

In 2018, MACOM ran into a force that doesn’t show up in product roadmaps: geopolitics. The U.S.–China relationship deteriorated fast, and semiconductors—because they sit at the choke points of modern technology—became a tool of policy.

The trade conflict began in January 2018, when U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration started imposing tariffs and other trade barriers on China. The stated goals were to address what the U.S. described as unfair trade practices, intellectual property theft, and forced technology transfer, as well as to narrow the U.S.–China trade deficit. China’s government, led by CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping, responded by accusing the U.S. of protectionism and taking retaliatory measures.

For chip companies, the stakes weren’t abstract. One name, in particular, turned into a fault line: Huawei. Trump and his administration argued Huawei posed a major security risk as 5G networks rolled out. And because Huawei was a meaningful customer across the RF and optical ecosystem, the message to U.S. suppliers was blunt: this business could disappear—not gradually, but instantly.

By mid-2019, after months of escalating U.S. pressure and restrictions, Huawei’s supply chain for computer parts and software was under siege. At the same time, governments around the world began threatening to ban Huawei’s 5G network equipment outright. For MACOM, the problem was the same one that hits every “picks and shovels” supplier when politics turns: you can be executing perfectly and still lose a market because someone changes the rules.

MACOM’s exposure to China had been both a growth opportunity and an existential risk. Chinese telecom customers could drive volume, but the trade war created the possibility of sudden revenue loss and forced a strategic reset. The response was to accelerate diversification—away from single-customer dependence and away from too much concentration in any one geography.

Right in the middle of this turbulence came an unexpected leadership change.

In May 2019, MACOM announced that Stephen Daly had replaced John Croteau as President and CEO. Croteau resigned on May 15 and moved into an advisory role for the next two months to support the transition. He’d been CEO since December 2012, and his tenure was defined by bold moves: the optical pivot, the acquisition-heavy buildout, and the push for GaN on silicon as an alternative to LDMOS and GaN on SiC.

Daly brought a different kind of reputation. From January 2004 through March 2013, he had served as President of Hittite Microwave Corporation, and he was Hittite’s CEO from December 2004 through March 2013. In the semiconductor industry, Hittite was known for something rare: exceptional profitability and operational discipline before it was acquired by Analog Devices. During Daly’s seventeen years there, he also led Hittite’s July 2005 IPO and helped build it into an innovative designer of high-performance RF, microwave, and millimeter-wave semiconductors with industry-leading profitability. In other words, MACOM was shifting from a roll-up-and-pivot era to a run-it-tight era.

Then, just as the company was absorbing the trade shock, 2020 arrived with COVID-19. Supply chains lurched from delay to disruption, adding a new layer of uncertainty on top of export controls and customer risk.

But the pandemic also pulled forward the very demand curve MACOM had been chasing. Remote work, streaming, and digital commerce drove a surge in cloud infrastructure buildout. More data centers meant more optical interconnects and more network equipment—exactly the plumbing MACOM had spent years assembling.

5G, meanwhile, stayed complicated. Deployments were uneven and often delayed, pushing out revenue timing in many markets. Still, MACOM kept positioning for the wave. And crucially, it didn’t have to bet the company on any single end market. That balance—defense holding steady, telecom challenged but recovering, and data center accelerating—helped MACOM survive a period that crushed less diversified semiconductor businesses.

VII. The Modern Portfolio: Strategic Focus & Product Lines (2020–Present)

Under Daly’s leadership, MACOM made a clean strategic turn. Where Croteau had expanded the company through big, sometimes messy bets, Daly’s job was to make the portfolio make sense. The watchwords became focus, fit, and execution. MACOM started shedding what didn’t belong and doubling down on the parts of the business where it could actually win—high-performance analog and photonic semiconductors that sit deep inside critical systems.

Today, MACOM designs and manufactures high-performance analog and photonic semiconductors across three end markets: Industrial & Defense (about 43%), Data Center (about 30%), and Telecommunications (about 27%). The unifying thread is “hard stuff at high frequencies”: premium, high-power, high-reliability applications. The company’s technology base spans platforms like gallium nitride on silicon carbide and indium phosphide photonics, supported by a manufacturing strategy that mixes vertical integration with trusted foundry relationships—because in defense and infrastructure, supply chain credibility matters almost as much as performance.

Those three pillars are built to balance each other.

Industrial & Defense is the heritage engine: radar, electronic warfare, satellite communications, and the specialized devices modern military and aerospace systems require. It tends to be high margin, relationship-driven, and sticky. The design cycles are long, qualification is painful, and once you’re in, you can stay in for a long time.

Telecommunications is the more volatile middle child. It includes 5G infrastructure, network equipment, and base stations—markets that swing with carrier capex cycles, geopolitics, and technology transitions. It can be frustrating quarter to quarter, but it’s also where the next big upgrade cycle, including the early path toward 6G, can create meaningful opportunity.

Data Center is where the growth story has increasingly concentrated. In FY25, data center revenue rose 48% to $293 million. MACOM positioned itself to benefit from the AI infrastructure buildout with optical components aimed at the newest generations of connectivity, including 800G and 1.6T, and it secured design wins across major module manufacturers. The appeal isn’t just faster growth—it’s also the potential for a healthier, more scalable mix over time.

Underneath all of this is a materials-science toolkit that looks like a periodic table of “make the signal behave.” MACOM’s technologies include gallium arsenide (GaAs), gallium nitride (GaN), silicon photonics (SiPh), aluminum gallium arsenide (AlGaAs), indium phosphide (InP), silicon (Si), heterolithic microwave integrated circuit (HMIC), and silicon germanium (SiGe). This breadth isn’t for show—it lets MACOM choose the right platform for the job, whether that job is squeezing power efficiency out of a radar front end or pushing more bits down a fiber inside a hyperscale data center.

And importantly, MACOM’s acquisitions in this era reinforced the focus rather than distracting from it.

In February 2023, MACOM announced it would acquire a new engineering and manufacturing facility in France: OMMIC. The deal, funded with cash on hand, had a purchase price of approximately €38.5 million and included real estate and associated facilities. The strategic logic was straightforward: deepen MACOM’s millimeter-wave capabilities, expand wafer production, and strengthen its presence in European markets.

MACOM completed the acquisition of OMMIC SAS in Limeil-Brévannes near Paris, bringing in expertise across wafer fabrication, epitaxial growth, and monolithic microwave integrated circuit processing and design. The site became the foundation for MACOM’s newly established European Semiconductor Center—positioning the company to offer customers higher-frequency gallium arsenide and gallium nitride MMICs.

Then came the bigger, more consequential bolt-on: Wolfspeed’s RF business.

MACOM announced it completed the acquisition of the radio frequency business of Wolfspeed, Inc. on December 2, 2023. This RF business brought a portfolio of gallium nitride on silicon carbide products used in high-performance RF and microwave applications, serving aerospace, defense, industrial, and telecommunications customers. At the time, it was generating annualized revenue of approximately $150 million, and MACOM expected the deal to be immediately accretive to non-GAAP earnings.

The assets were substantial: a 100mm GaN wafer fabrication facility in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina—set to convey to MACOM roughly two years after closing—plus design teams and product development resources in Arizona, California, and North Carolina, along with back-end production capabilities in California and Malaysia. MACOM also received a deep IP portfolio, including over 1,400 patents associated with the RF business. The purchase price was $125 million.

And MACOM didn’t stop there. In November 2024, the company acquired ENGIN-IC, Inc., a fabless semiconductor company in San Diego that designs advanced gallium nitride monolithic microwave integrated circuits and integrated microwave assemblies. The expected benefit was sharper GaN design capability aimed squarely at MACOM’s target markets, particularly defense. ENGIN-IC, founded in 2014 by industry veterans, had focused on the U.S. defense industry since inception, funding itself through mechanisms like small business innovative research contracts, Department of Defense research projects, and custom IC development work for defense prime contractors.

Put it all together and you can see the modern MACOM shape clearly: less empire-building, more deliberate concentration. A portfolio tuned for infrastructure and defense, a technology stack that’s hard to replicate, and a renewed emphasis on owning the capabilities that matter most when performance and trust are the price of admission.

VIII. The Technology Moat: What MACOM Actually Makes

To understand MACOM’s competitive position, you first have to understand what these chips actually do—and why “just build another one” is rarely an option.

Take an RF power amplifier. Its job is straightforward on paper: take a weak signal and make it strong enough to matter. In practice, it’s a physics problem disguised as a product. You’re trying to amplify power without mangling the signal, while juggling heat, efficiency, and linearity across punishing frequency ranges. And you’re doing it in environments where “mostly works” isn’t acceptable. In a military radar system, the power amplifier helps determine how far you can see and how cleanly you can track. In a 5G base station, it shapes coverage, capacity, and how many users can connect at once.

That’s why materials matter—and why gallium nitride, or GaN, has become such a big deal. MACOM’s GaN RF power amplifier solutions are built on GaN-on-SiC and GaN-on-Si platforms. Its PURE CARBIDE family of GaN-on-SiC power amplifiers targets the most demanding use cases where performance and reliability are the price of admission. The broader GaN portfolio is designed for Aerospace & Defense, Industrial, Scientific and Medical applications, and 5G wireless infrastructure. Across the line, MACOM’s GaN products span output power from a couple watts to multiple kilowatts, with strong gain and efficiency.

Zoom out, and the story here is a technology transition. For years, the incumbent in RF power was LDMOS. It dominated early generations of RF power amplifiers because it was understood, manufacturable, and good enough. But GaN can offer superior RF characteristics and substantially higher output power—exactly what next-generation infrastructure and defense systems keep demanding. GaN-on-silicon, in particular, holds long-term potential for 5G and 6G, promising a different cost curve than the more established GaN-on-SiC approach.

The catch is that these transitions don’t happen on a Silicon Valley schedule. MACOM’s partnership with STMicroelectronics on GaN-on-silicon is a good example of the real timeline: prototype wafers and devices manufactured by ST hit cost and performance targets that could compete with incumbent LDMOS and GaN-on-SiC offerings. But that’s only the beginning. After prototypes come the hard gates—qualification and industrialization—where promising lab results either turn into dependable volume production or quietly die.

Governments have also treated GaN as strategic, not just commercial. MACOM’s work expands on a series of GaN technology development activities with the U.S. Department of Defense. In 2021, it entered a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory and successfully transferred AFRL’s 0.14 micron GaN-on-SiC MMIC process to MACOM’s Massachusetts-based U.S. Trusted Foundry. That was followed in 2023 by a $4 million AFRL contract to develop GaN technologies for millimeter-wave applications, and a DARPA award valued at up to $10.1 million focused on improving heat dissipation for high-power applications. Earlier this year, MACOM was awarded a separate CHIPS-funded GaN technology development contract worth up to $11.4 million.

On the data center side, the “moat” looks different, but the difficulty is the same. Silicon photonics is about converting electrons to photons—and back again—faster and more efficiently as bandwidth keeps exploding. MACOM leans on its high-speed signal-processing know-how, analog and mixed-signal design, and optical semiconductor experience to help customers build the fastest possible links in and around the data center, whether NRZ, PAM-4, or coherent. It also plays in the coherent transmission world for campus, metro, and long-haul optical networks, with components designed to survive the brutal requirements of high-density, high-efficiency deployments. That includes products like dual- and quad-channel linear transimpedance amplifiers and quad-channel drivers—unsexy names for parts that can make or break a high-speed optical link. And whether the system is 400G, 800G, or 1.6T, the goal is the same: keep the network ahead of demand.

All of this adds up to the analog advantage. Digital chips benefit from scale and standardization, but they also face relentless commoditization pressure. Analog, RF, and photonics are different. The constraints are physical, not abstract. The design expertise is learned over decades. And manufacturing isn’t just “run it at a foundry”—it’s specialized process knowledge that doesn’t transfer cleanly and can’t be automated away.

MACOM is primarily fabless: it concentrates internal resources on design, development, and testing, while outsourcing wafer fabrication, assembly, and packaging to specialized foundries and subcontractors. The payoff is flexibility and scalability without having to constantly fund massive manufacturing expansions. It also puts the spending where the differentiation lives. In fiscal year 2024, MACOM invested about $115.8 million in research and development, roughly 17.3% of revenue.

But MACOM isn’t purely fabless, either—because some customers won’t accept that. The company maintains internal fabrication capabilities, especially for defense programs where trusted manufacturing is required. Both fabs are Category 1A Trusted Foundries with the U.S. Department of Defense, producing compound semiconductors used in high-frequency defense systems like airborne and ground-based radar, alongside select commercial applications such as telecom.

And then there’s the business-model tradeoff that defines so much of this industry: custom versus standard. Custom design wins can take years, but they create real stickiness. Once a component is designed into a system, customers don’t switch casually—the requalification effort is painful, and the full system is often tuned around your chip’s specific behavior. Even qualification alone can take 18 to 24 months. The result is durable revenue once you’re in, but a constant need for patience and long-term execution to get there.

IX. The Business Model & Market Dynamics

MACOM’s business model lives in a corner of semiconductors where the cheapest part rarely wins. In analog, RF, and photonics, customers buy confidence: performance that holds up at the edge of spec, parts that ship consistently, and engineering relationships that survive the inevitable late-night debug sessions. MACOM sells to more than 6,000 customers a year, which sounds nicely diversified—until you remember how this industry works. A handful of big OEMs and platform programs can still matter a lot. Lose one major customer, and the hit isn’t theoretical.

The other defining feature is time. Design wins don’t turn into revenue on a quarterly schedule. A part that gets selected today may not show up in meaningful volume for two to three years, as the customer moves from prototype to qualification to full production. That lag is frustrating—because it forces you to manage a pipeline you won’t be paid for anytime soon—but it’s also the source of the moat. Once you’re designed in, you’re hard to rip out. Switching isn’t just a purchasing decision; it’s a requalification project.

Then there’s the cycle. No matter how specialized the product, semiconductors still move in booms and busts. Data center spending surges, then pauses. Telecom capex ramps, then gets deferred. Defense can be steadier, but even it is shaped by budgets and program timing. The companies that survive aren’t the ones that predict every cycle—they’re the ones that stay financially disciplined enough to keep investing through downturns without blowing themselves up.

You can see both the strength and the variability in MACOM’s results. In fiscal year 2024, adjusted non-GAAP gross margin was 57.9%, down from 61.3% in fiscal 2023. Adjusted income from operations was $175.0 million, or 24.0% of revenue, versus $189.6 million, or 29.2% of revenue, the year before. Adjusted net income came in at $188.2 million, or $2.56 per diluted share, compared with $193.3 million, or $2.70 per diluted share, in fiscal 2023.

That “high-50s” gross margin profile is the point. MACOM isn’t trying to win by being the lowest-cost supplier in a commodity category. It wins by shipping parts that make expensive systems better. And in markets like telecom infrastructure, small improvements compound. A power amplifier that squeezes out even a little more efficiency doesn’t just look good in a datasheet—it can translate into materially lower power consumption across a network over years of operation.

The comps help frame where MACOM sits. Against Qorvo and Skyworks—both heavily exposed to the mobile RF cycle and typically running gross margins in the low-to-mid 40s—MACOM’s 54.7% gross margin reflects a mix tilted toward higher-value defense and data center applications. Analog Devices shows the other end of the spectrum: much larger scale, about $11 billion in revenue, and 61.5% gross margins, but growing at a more modest 17% pace.

Capital allocation is where Daly’s influence shows up most clearly. The Croteau era used big M&A to transform the company’s portfolio. Daly shifted the emphasis toward tighter execution and more targeted, bolt-on deals that reinforce what MACOM already does well. Free cash flow generation improved, debt from the acquisition spree began getting paid down, and the balancing act became clearer: keep investing for growth, but don’t sacrifice financial resilience.

Finally, the supply chain became part of strategy, not just operations. Post-pandemic and in a more geopolitically tense world, “single source” can be a hidden liability. Dual-source approaches—qualifying multiple foundry partners for the same process—reduce the risk of a single point of failure. And geographic diversification, including the European Semiconductor Center in France, gives MACOM more options if regional disruptions hit. In this business, reliability isn’t only about the chip. It’s about your ability to keep shipping it.

X. Porter's 5 Forces & Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Porter's 5 Forces

Threat of New Entrants: HIGH BARRIERS. In most industries, a startup can rent cloud servers and ship a product. In analog semiconductors, you don’t get that luxury. Competing with MACOM means decades of accumulated RF and photonics know-how, sustained R&D spend, and customer relationships that were earned over long, painful design cycles. The IP landscape is also a minefield—freedom-to-operate is hard, and getting around entrenched portfolios is expensive. Then layer on defense: trusted foundry requirements, security constraints, and certifications that can’t be fast-tracked. New entrants can show up in narrow corners, but displacing an incumbent like MACOM across a broad portfolio is extraordinarily difficult.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE. MACOM relies on specialized foundry partners, assembly houses, and equipment vendors—and recent years have reminded everyone how fragile semiconductor supply chains can be. Still, MACOM has more flexibility than many peers because it spans multiple technology platforms (GaN, GaAs, InP, SiGe) and can use a mix of internal capabilities and outside partners. Dual-source strategies help avoid single points of failure. Over time, CHIPS Act funding tied to internal fab expansion should also reduce supplier leverage.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: HIGH. MACOM sells into markets where the customers are powerful, technical, and price-aware. Hyperscalers and major defense contractors know exactly what they’re buying, and they have options. Defense procurement can sometimes be more insulated—sole-source dynamics and strict specifications can protect incumbents—but commercial sockets are brutally competitive and pricing pressure is constant. Customer concentration risk is real: losing a meaningful data center position would hurt.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE to HIGH. The biggest substitute risk isn’t a cheap knockoff. It’s the next technology wave. New materials, new architectures, and customer vertical integration can all redraw the map. MACOM has benefited from navigating transitions like LDMOS to GaN. It’s also operating through another shift as silicon photonics changes how optical links are built. That said, physics sets boundaries: you can’t replace an RF power amplifier with software, and you can’t wish away signal integrity challenges just because you’d like a simpler supply chain.

Competitive Rivalry: HIGH. MACOM fights on multiple fronts: Broadcom, Analog Devices, Qorvo, Skyworks, Marvell, and others, depending on the product line. In more commoditized segments, competition quickly becomes price-led. Consolidation cuts both ways—there can be attractive acquisition targets, but there are also larger competitors with deeper pockets and broader sales reach. And looming over everything is a structural threat: vertical integration by customers, especially hyperscalers, who increasingly design more of their own silicon and squeeze the merchant market.

Hamilton's 7 Powers

Scale Economics: MODERATE. There are real scale benefits in semiconductors—R&D is largely fixed, and bigger volume helps absorb it. But analog and RF aren’t pure winner-take-all markets. Multiple companies can coexist profitably because performance needs vary and differentiation is real. MACOM is smaller than giants like Analog Devices or Broadcom, but its focus allows it to spend where it matters instead of trying to cover every category.

Network Effects: LOW. This is not a platform business. One customer using MACOM parts doesn’t inherently make those parts more valuable to other customers. Each relationship is largely self-contained, built on specs, support, and execution rather than a “more users attracts more users” flywheel.

Counter-Positioning: HISTORICALLY STRONG, NOW FADING. The private-equity reset in 2009–2012 enabled moves incumbents were structurally reluctant to make—cut costs hard, refocus, and then roll up fragmented assets aggressively. That insurgent advantage has largely played out. Today, MACOM is no longer the upstart exploiting incumbent inertia; it’s one of the established players defending and extending its position.

Switching Costs: STRONG. This is MACOM’s most durable power. Once a part is designed in, it’s sticky. Swapping suppliers isn’t a procurement decision; it’s a requalification program with heavy testing, documentation, and validation—often taking 18 to 24 months. Customers avoid that pain unless they have a compelling reason. The catch is that switching costs protect what you already won; they don’t win the next socket for you.

Branding: WEAK to MODERATE. In B2B semiconductors, “brand” mostly means reputation: reliability, quality, and whether your team shows up when something breaks at 2 a.m. MACOM’s long heritage helps, especially in defense and infrastructure. But this isn’t a consumer market where brand alone creates pricing power.

Cornered Resource: MODERATE. MACOM has meaningful technology and IP advantages in pockets—GaN expertise, photonics capability, and the patent portfolio brought in through acquisitions. The Wolfspeed RF business alone came with over 1,400 patents associated with that RF portfolio. Scarce talent is another constraint: great analog engineers are hard to find, and MACOM’s engineering presence in places like Massachusetts and North Carolina creates clusters of knowledge that don’t replicate easily. Still, none of this is fully exclusive—serious competitors have their own deep benches and their own IP.

Process Power: MODERATE to STRONG. Years of serial M&A and operating in high-reliability markets have forced MACOM to build real organizational muscle: integration discipline, design methodologies, and manufacturing and qualification processes that work under pressure. That’s an advantage, especially in a business where mistakes are expensive. But process power isn’t permanent—competitors can improve, copy, and invest their way closer over time.

Overall Assessment: MACOM’s moats are real, but narrow—exactly what you’d expect in a brutally competitive semiconductor niche. The strongest protection comes from switching costs created by long design-in cycles. Technical depth in GaN and photonics raises the bar in targeted applications. But no single advantage is enough to coast. In semiconductors, survival is earned every cycle, and prosperity demands constant innovation and disciplined capital allocation.

XI. The Bull vs Bear Case

The Bull Case

The secular growth drivers are real, and MACOM sits in the middle of several of them at once. 5G deployment has continued globally, 6G research is already underway, and the radio hardware behind these networks keeps getting more demanding. On top of that, the data center buildout has accelerated as AI workloads push bandwidth requirements higher, and defense budgets have expanded as geopolitical tensions have risen—particularly across NATO in response to the Ukraine conflict and concerns about China.

Put those together and you get the core bull thesis: MACOM is on the critical path of three long-running trends. First, the AI data center buildout is driving the next wave of optical upgrades, including 800G and 1.6T. Second, defense modernization is pulling more GaN-based radar and electronic warfare systems into programs of record. Third, 5G and the early runway to 6G are demanding higher-frequency, higher-efficiency RF solutions—exactly the kind of “hard at high frequency” problem MACOM has spent decades solving.

Another tailwind is industry structure. A decade ago, analog and RF looked like a patchwork of specialists. Over time, consolidation has pushed the market toward a smaller number of better-capitalized players. In theory, that can mean more rational competition: fewer companies forced into destructive pricing just to keep the lights on, and more companies able to fund the R&D and manufacturing credibility customers require.

On technology, MACOM’s positioning in GaN and silicon photonics matters because the requirements keep moving forward. The company has also been supported by the policy environment around domestic manufacturing. The U.S. Department of Commerce signed a non-binding preliminary memorandum of terms with MACOM to provide up to $70 million in proposed direct funding under the CHIPS and Science Act. That proposed funding would support expanding and modernizing MACOM’s facilities in Lowell, Massachusetts, and Durham, North Carolina, and would create up to 350 manufacturing jobs and nearly 60 construction jobs across both states.

In parallel, MACOM announced a long-term capital investment plan of up to $345 million over five years to modernize those same wafer fabrication facilities. The plan is supported by the preliminary, non-binding agreement with the CHIPS Program Office and contemplates up to $180 million of support through a combination of proposed direct federal funding, federal investment tax credits, and state funding.

Operationally, the bull case is also a story about focus. Under Daly, MACOM has tried to become a leaner, more coherent company: shedding non-core assets, concentrating R&D, and putting capital behind the product lines where it can win. Years of embedded design wins create the kind of multi-year visibility that semiconductor investors love—slow to build, hard to dislodge once secured.

And there’s a scale milestone, too. MACOM reached a $1 billion annual revenue run rate in Q1 FY26, a level that matters not because it’s a round number, but because it can unlock operating leverage and validate the company’s long strategy of building a more vertically integrated, high-performance RF and optical portfolio.

From here, the optimistic view is that margins can expand as revenue scales and recent acquisitions get fully integrated. The Wolfspeed RF deal, in particular, brings the RTP fab capacity that MACOM can optimize over time. If execution holds, revenue growth should translate into faster earnings growth.

Finally, there’s optionality. MACOM has an established platform for further consolidation if valuations become attractive, and its track record with bolt-on integration reduces the execution risk relative to a first-time acquirer.

The Bear Case

The bear case starts with the brutal reality of this business: customer concentration can turn into a binary risk. Losing a major hyperscaler position, or a major defense customer on an important program, can do real damage to revenue and earnings. A large share of the business can still hinge on a relatively small number of big relationships.

Then there’s cyclicality. Semiconductors always cycle. When markets turn down, multiples compress and earnings follow. The current AI-driven optimism could prove fragile if data center spending decelerates or pauses longer than expected.

Competition hasn’t gotten easier, either. Customer vertical integration is accelerating, especially among hyperscalers. The major cloud providers are investing heavily in custom silicon, and while that doesn’t eliminate the need for merchant analog and optical components, it can shift pricing power and, in some cases, disintermediate suppliers. Meanwhile, well-funded competitors can still leapfrog with new process technology, packaging, or system-level integration.

Geopolitics remains an overhang. China exposure, export controls, and supply chain disruptions can all impact results, and the concentration of advanced semiconductor manufacturing in Taiwan creates systemic risk that extends far beyond MACOM.

Execution risk is constant in a portfolio like this. Integrations have to work. New technology transitions have to land. Products have to ship on time. And in analog, RF, and photonics, complexity is the default setting—meaning “a little late” or “slightly off spec” can be the difference between a design win and a lost socket.

Valuation is another pressure point. At $174.99 per share, MACOM traded at 13.6 times trailing twelve-month sales and 13.4 times enterprise value to revenue. That’s a meaningful premium to mobile-focused RF peers like Qorvo and Skyworks, at 2.2x and 2.4x sales, respectively. If growth disappoints, the premium can unwind quickly.

And while analog is more defensible than many digital categories, commoditization pressure never fully disappears. As technologies mature and interfaces standardize, differentiation can erode, pricing power can slip, and today’s premium margins can become harder to defend.

KPIs to Track

For investors monitoring MACOM’s ongoing performance, two metrics stand out as most critical:

1. Gross Margin Trajectory. MACOM’s ability to maintain and expand gross margins above 55% is a strong signal that mix is improving and manufacturing is executing. Margin compression would point to competitive pressure or operational issues. The company has guided for 25 to 50 basis points of sequential improvement, so the question is simple: does the actual print match the story?

2. Data Center Revenue Growth and Mix. Data center is both the fastest-growing segment and the one most directly tied to the AI infrastructure buildout. Tracking quarterly data center revenue—both in dollars and as a share of total—shows whether MACOM is actually capturing the hyperscale opportunity. FY25’s 48% growth and $293 million in data center revenue sets the baseline.

XII. Recent Developments & Current Situation (2024-2025)

By fiscal 2025, the numbers finally started to reflect what MACOM had been building toward for more than a decade. When the company reported results in November 2025 for the fiscal year ended October 3, 2025, it posted adjusted net income of $263.4 million, or $3.47 per diluted share—up from $188.2 million, or $2.56 per diluted share, in fiscal 2024. Stephen G. Daly framed it plainly: “We built upon our strong foundation in fiscal year 2025, and we look forward to starting fiscal 2026.”

The most immediate momentum showed up in the quarter. Fiscal fourth quarter revenue came in at $261.2 million—up about 30% from the same quarter the prior year and modestly higher than the prior fiscal quarter.

The bigger story underneath those results was that the AI data center buildout was no longer a “someday” market. It was here, and it was forcing the industry to care about a constraint that looks mundane until you’re operating at hyperscale: power. That’s why MACOM’s positioning around Linear Drive Pluggable Optics has mattered. LPO sits right at the intersection of bandwidth growth and power-efficient networking, and MACOM has been highlighted as an enabler of next-generation optical connectivity in that architecture.

At the same time, the market got a reminder that even the hottest demand themes still depend on financing and construction reality. Attention sharpened after reports that a very large $10 billion Oracle–Blue Owl Capital data center funding deal in Michigan stalled. The combination—MACOM’s clear relevance to AI-era optics alongside renewed scrutiny of how infrastructure gets funded—put a spotlight on both the opportunity and the risk in the optical ecosystem MACOM sells into.

One LPO use case illustrates the appeal: the switch-to-server link. In linear drive architectures, linear drive modules eliminate the digital signal processor from pluggable optical modules, which can reduce power consumption, improve latency, and lower cost. It’s a classic MACOM sweet spot: not the headline-grabbing system, but a critical piece of the performance-and-efficiency puzzle.

While data center grabbed the growth narrative, defense continued to do what defense often does for MACOM: provide a stable, high-value counterweight. The company’s Industrial & Defense segment—about 43% of revenue—grew 19%, with 50% GaN product growth. MACOM’s Trusted Foundry status and its gallium nitride on silicon carbide leadership function like a dual moat here, supporting pricing power and cash flow stability even as many RF peers ride the much rougher mobile cycle.

Telecom, meanwhile, looked more like a business than a promise. 5G had matured from hype into deployment reality, even if international rollouts continued to stretch out. After years of investment in RF power amplifiers and infrastructure components, MACOM’s positioning in this market was increasingly showing up as revenue rather than as development spend.

Looking ahead, MACOM’s guidance for the fiscal first quarter ending January 2, 2026, called for revenue of $265 million to $273 million, adjusted gross margin of 56.5% to 58.5%, and adjusted earnings per diluted share of $0.98 to $1.02.

The stock followed the fundamentals—volatile, but trending with improved expectations. Over the past 52 weeks, shares traded between $190.95 and $84.00. Analyst sentiment was constructive, too. Truist analyst William Stein raised the firm’s price target to $200 from $180 and maintained a Buy rating.

What comes next is less about declaring victory and more about proving the machine can keep running. A billion-dollar revenue run rate is a real milestone, but MACOM is still small relative to giants like Analog Devices or Broadcom—and in semiconductors, size can be both insulation and weapon.

There are also plenty of projections floating around. One narrative from MACOM Technology Solutions Holdings forecasts $1.2 billion in revenue and $586.5 million in earnings by 2028, implying roughly low-double-digit annual revenue growth. Whether that plays out depends on the same things that have always governed this company’s fate: winning the next sockets, executing on manufacturing and integration, and staying resilient when the cycle—or geopolitics—turns.

XIII. Lessons for Founders, Operators & Investors

MACOM’s journey is a reminder that “boring” infrastructure companies often teach the most useful lessons—because they win (or lose) on execution, not hype.

The PE Transformation Playbook. When private equity creates real value, it doesn’t start with leverage. It starts with focus. MACOM’s 2009–2012 reset shows what happens when a neglected division is forced to run like a standalone business: clear accountability, hard cost decisions, and capital aimed at strategy instead of inertia. The trick is choosing situations where operations can improve—not just borrowing against steady cash flow.

Serial M&A Execution. Deals don’t create advantage; integration does. Croteau’s acquisition run expanded MACOM’s capabilities, but it also stretched the organization and raised the difficulty level of day-to-day execution. Daly’s later pruning made the implicit lesson explicit: buying assets is the easy part. Making the combined company work—systems, roadmaps, culture, and customers—is what separates a builder from a collector. Culture really does eat strategy.

Reading Technology Transitions. MACOM didn’t get to data centers by accident. The pivot from defense to telecom to cloud required making bets years before the payoff was obvious. BinOptics, AppliedMicro, and Wolfspeed’s RF business weren’t quick wins—they were long-duration wagers on where bandwidth, power efficiency, and high-frequency performance were headed. In semiconductors, timing is strategy: you can be “right” and still be too early or too late.

Portfolio Management. Sometimes the smartest acquisition move is the divestiture you plan on day one. Selling Mindspeed’s wireless business to Intel and divesting AppliedMicro’s compute division to Carlyle weren’t footnotes—they were the portfolio discipline that kept the broader strategy coherent. Knowing what not to be is a competitive advantage, and it’s one of the most underappreciated forms of capital allocation.

Surviving Cyclicality. Semiconductors punish overconfidence. The companies that expand too aggressively in booms and then cut too deeply in busts often don’t get a second chance. MACOM lived through the financial crisis, the US–China trade shock, and COVID-era disruption, and it stayed intact. That kind of survival usually looks unglamorous: conservative enough to endure downturns, but committed enough to keep investing through them.

The Analog Fortress. Some categories don’t commoditize easily because physics refuses to cooperate. RF, microwave, millimeter-wave, and photonics aren’t just “chips”—they’re hard-won expertise applied to messy real-world constraints like heat, noise, interference, and reliability. For investors, the lesson is to look for these analog fortresses: places where deep technical know-how and qualification cycles create defensibility even without consumer branding.

Customer Concentration Paradox. Big customers are both the opportunity and the existential risk. Hyperscalers, in particular, have enormous leverage—MACOM needs them more than they need MACOM. But if you win and hold those sockets, you get something rare: multi-year visibility and a clear roadmap for where to focus R&D.

The "Boring" Company Advantage. MACOM’s story has no consumer brand, no viral growth loop, no founder mythology. It’s a company built the old-fashioned way: by showing up with reliable performance, shipping on time, and solving difficult problems for demanding customers. That can be a feature, not a bug—especially in markets where trust and execution are the real differentiators.

Patience in Compound Semiconductors. In materials science, “fast” is measured in years. MACOM’s GaN push—accelerated by the Nitronex acquisition in 2014—took a long time to mature into volume commercial opportunity. This is a business where quarterly pressure can push leaders into value-destroying shortcuts. The reward goes to patient capital and long-term engineering timelines that are allowed to actually run their course.

XIV. Epilogue & The Future

Looking out over the next decade, MACOM’s story isn’t “done.” It just enters the phase where the plot twists come from forces no management team fully controls. A few wildcards could meaningfully reshape the company’s trajectory—for better or worse.

6G and Beyond. If 5G was about densifying networks and pushing more bits through the air, 6G is expected to push the physics even harder, moving to higher frequencies and tighter performance requirements. MACOM’s investments in millimeter-wave—and the “above” part of that roadmap—put it in the right neighborhood. But the calendar matters here. The big 6G buildout looks more like a 2030s event than a near-term revenue engine.

Quantum Communications. As quantum computing advances, today’s encryption assumptions start to look less permanent. That opens the door to quantum-secure communications and related photonics-heavy approaches. MACOM’s optical and photonics expertise could translate, but this is still a speculative market—more a directional option than a line item you can model with confidence.

New Materials Science. Compound semiconductors have been one of MACOM’s long-running advantages, but the frontier keeps moving. If new materials or new device structures emerge beyond today’s GaN and GaAs playbook, MACOM could either benefit—by being early and credible—or get pressured if competitors jump a generation ahead. In this business, “staying current” isn’t maintenance. It’s survival.

The AI Wild Card. Generative AI has already pulled forward demand in data centers, and that’s the most immediate catalyst: AI workloads need massive connectivity, and MACOM’s optical products help enable that plumbing. The harder question is what AI does next. Could AI materially compress analog design cycles? Could it improve yield and test, or accelerate packaging and integration? And on the other side of the ledger: could hyperscalers’ vertical integration efforts accelerate as AI becomes central to their strategy, squeezing merchant suppliers even harder? The opportunity is real. The second-order effects are unpredictable.

Consolidation Endgame. The semiconductor industry rarely stays fragmented forever. MACOM, at roughly a $13 billion market cap, sits in an interesting spot: large enough to matter, small enough to buy. A larger platform—Broadcom, Analog Devices, or even a motivated Asian competitor—could plausibly see strategic value in combining MACOM’s RF and optical portfolio with broader scale, sales reach, and manufacturing leverage. Whether MACOM would want that future, and whether regulators would, is an open question.

The China Question. Can any semiconductor company cleanly navigate U.S.–China decoupling? Export controls have expanded, supply chains are being re-architected, and uncertainty has become a permanent tax on planning. MACOM’s Trusted Foundry status and domestic manufacturing capabilities help, but the industry’s deep dependency on global manufacturing—especially across Asia—means the risk never goes away. The question isn’t “is there exposure?” It’s “how resilient is the response when rules change fast?”

Climate and Sustainability. Data centers don’t just need bandwidth; they need power efficiency. That turns energy into product strategy. MACOM’s emphasis on GaN—often more efficient than legacy RF technologies—fits the trend toward lower watts per bit and better network efficiency. As carbon constraints and power availability increasingly shape infrastructure decisions, efficient components can earn real premiums.

What Would We Want to See. If you were sketching the path to a significantly larger MACOM from here, it’s a familiar checklist, but not an easy one: margins sustaining a move back toward the high end of the model, continued data center growth at a strong clip, a clean integration and ramp of the Wolfspeed RF business, and more unmistakable hyperscaler design wins that translate into durable volume. All of that is plausible. None of it is guaranteed.

The MACOM lesson is the same one the semiconductor industry teaches over and over: staying alive is an achievement. This is a business that has destroyed enormous amounts of capital and ended countless “sure things.” Sustained prosperity takes something rarer—technical excellence, strategic clarity, operational discipline, and unusually good capital allocation.

From Cold War magnetrons to AI-era optical interconnects, MACOM shows that reinvention is possible, but it’s never free.

And in a world fixated on software platforms and consumer brands, MACOM is a reminder of a different kind of compounding: the kind built on physics, qualification cycles, and trust. A few critical customer relationships matter more than marketing to millions. Decades of accumulated know-how matter more than hype. It’s not the kind of company that inspires breathless headlines. But it sits in the infrastructure layer that makes the digital economy possible—and it’s a case study in how determined operators can build enduring value in one of the most unforgiving industries on earth.

XV. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form References

-

MACOM Investor Relations (ir.macom.com): Annual reports (10-Ks) from 2012–2025 are the backbone sources for this story—how the portfolio evolved, what management said they were trying to do, and how the numbers and risk factors changed as the company shifted from legacy RF into cloud-era connectivity and GaN.

-

McKinsey Semiconductor Practice Reports: “Unlocking the Potential of Analog Semiconductors” and related work are useful for zooming out—why analog and RF behave differently than digital, why consolidation happens, and where value tends to accrue.

-

"The Innovator's Dilemma" by Clayton Christensen: A foundational lens for the kinds of pivots MACOM had to make: leaving comfortable legacy markets, taking lower-margin growth bets, and surviving technology transitions that can kill incumbents.

-

IEEE Publications on GaN Technology and RF Semiconductors: For the technical underpinnings—GaN device physics, RF power tradeoffs, and why process technology and reliability are the real battlegrounds.

-

Semiconductor Industry Association Reports: Helpful context on market cycles, industry structure, and policy shifts—including CHIPS Act-related developments that affect manufacturing strategy and incentives.

-

"Barbarians at the Gate" by Burrough & Helyar: Not about MACOM, but a vivid primer on incentives, leverage, and the logic of financial sponsors—useful backdrop for understanding the private equity era and the “operate first” playbook.

-

Goldman Sachs Alternatives Case Studies: A look at how operational improvement, cost discipline, and strategic repositioning can turn neglected assets into focused platforms—directly relevant to the reset that set MACOM up for its IPO.

-

Light Reading / Fierce Telecom Archives: Great for reconstructing the environment MACOM sold into—5G rollout realities, carrier capex cycles, optical networking shifts, and the broader infrastructure storyline around the company’s products.

-

Compound Semiconductor Magazine / Microwave Journal: The trade press that tracks the world MACOM lives in: GaN, GaAs, InP, RF front ends, microwave systems, and the incremental engineering progress that rarely makes mainstream headlines.

-

"7 Powers" by Hamilton Helmer: The framework used in the analysis section—especially useful for thinking clearly about what is and isn’t a moat in semiconductors.

Additional Resources

-

Earnings Call Transcripts (Seeking Alpha, company website): The fastest way to hear what management thinks matters each quarter, and how the narrative changes when markets turn.

-

Trade Publications: AnandTech and Semiconductor Engineering are strong for practical, technical coverage of data center interconnects, packaging, and manufacturing trends.

-

Competitor Investor Presentations: Broadcom, Qorvo, Analog Devices, Skyworks—MACOM makes more sense when you see how adjacent players describe the same markets and where they choose to compete.

-

Academic Papers on Silicon Photonics and GaN Technology: For readers who want to go past “what it does” into “how it works,” these papers are the most direct route to understanding the durability—and limits—of MACOM’s technology edge.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music