MGIC Investment Corporation: The Mortgage Insurance Giant That Survived the Unthinkable

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: it’s early 2009. MGIC’s CEO, Curt Culver, gets on a conference call with investors who are no longer asking about quarterly guidance. They’re asking whether the company will make it to the next quarter.

MGIC’s stock, once above $70, has cratered to under $2. Losses are piling up into the billions. And around the industry, the floor is giving way—Triad Guaranty has already stopped writing new business, and PMI Group is sliding toward bankruptcy. Culver, nearing the end of a 43-year career in mortgage insurance, is looking straight at the void and telling the market: MGIC will survive.

He’d later admit just how close it felt. “I didn't know if the company could make it,” Culver confessed, as credit losses mounted and the stock lost 99% of its value. But MGIC did make it. And in the years since, it didn’t just crawl back—it rebuilt into the dominant force in the industry it essentially invented. Today, MGIC carries roughly $310 billion of primary insurance-in-force and reported net income of about $750 million in fiscal 2024.

So how does a company get that close to the edge—watch competitors fail all around it—and come out the other side stronger?

That’s the question at the heart of MGIC’s story. It’s a story about the hidden infrastructure of American homeownership. About how regulation can suffocate an industry—or turn into a moat that protects the survivors. And about a peculiar kind of business that most homebuyers never think about, even while they’re paying for it every month.

MGIC Investment Corporation (NYSE: MTG) has insured more than 14 million homeowners since it began. If you’ve ever bought a house with less than 20% down, you’ve probably paid for private mortgage insurance—and there’s a good chance MGIC was the one standing behind that loan. The company is massive, essential, and almost completely invisible: the plumbing beneath the American dream.

And here’s the irony. In mortgage insurance, the best possible outcome is boredom. Policies get written, premiums come in, borrowers make their payments, and years later the insurance quietly disappears when enough equity builds up. The worst possible outcome is a chain reaction of defaults so severe it threatens the insurer’s right to do business at all—exactly what happened to MGIC from 2007 to 2012 in the harshest stress test the industry has ever endured.

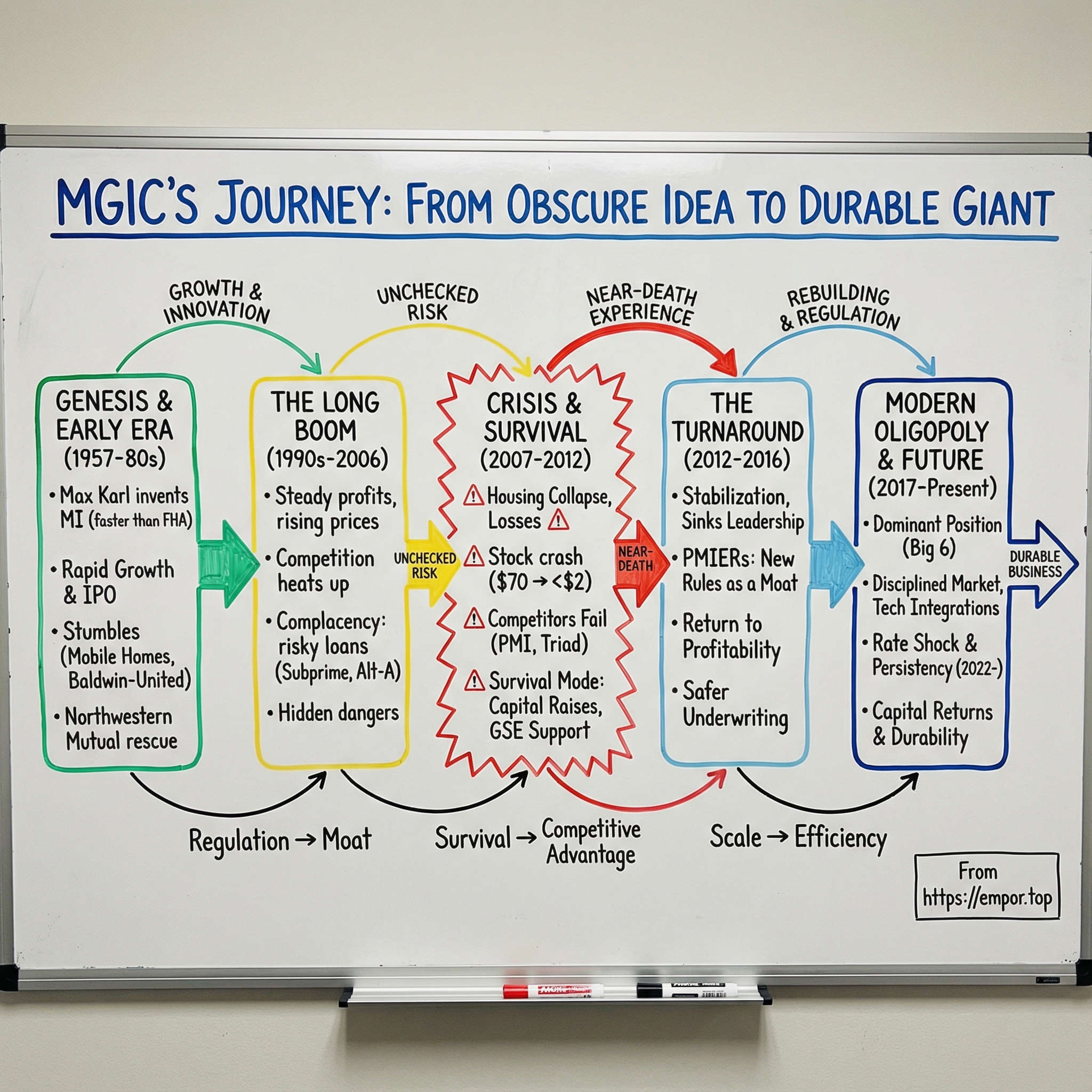

We’re going to tell that full story: the invention of modern private mortgage insurance, the long boom that bred complacency, the near-death experience of the financial crisis, and the comeback that followed—one built on tougher rules, fewer competitors, and hard-earned institutional memory.

Along the way, a few themes keep showing up: survival as the ultimate competitive advantage, regulation as destiny, and the strange durability of companies that sit deep inside critical financial systems. For investors, MGIC is ultimately a bet on American housing itself—and on whether the lessons of the last crisis actually stuck.

II. Mortgage Insurance 101 & Industry Context

To understand MGIC, you first have to understand the weird, half-public, half-private machine it lives inside. American housing finance isn’t a free market in the pure sense; it’s a system built after the Great Depression, then layered over with decades of policy that treats widespread homeownership as a national objective.

Private mortgage insurance exists because of one blunt rule embedded in the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac charters: if a borrower puts down less than 20%, that loan needs “credit enhancement” before the GSEs will buy it or securitize it. In practice, that credit enhancement is almost always PMI—something like 98–99% of the time. That single requirement creates structural, recurring demand for MGIC’s product. It’s not a nice-to-have, and it’s not something you can wish away with clever structuring. If you want a conforming mortgage with less than 20% down, someone has to insure it. Period.

More specifically: unless the lender provides another charter-compliant form of credit enhancement, a conventional first mortgage with an LTV above 80% has to carry primary mortgage insurance at the point it’s purchased by Fannie Mae or placed into a Fannie Mae-backed security. That’s the gateway MGIC sits at.

For homebuyers, this system is basically leverage—socially acceptable, mass-market leverage. Without mortgage insurance, millions of Americans would have to sit on the sidelines until they’d saved a full 20% down payment. In an era where home prices have outpaced wage growth for decades, that would push homeownership further out of reach. With MI, a borrower can often buy with 3% down on a conventional loan, or 3.5% down through FHA.

From there, the business model looks simple: MGIC collects a premium and, in exchange, promises to reimburse losses if the borrower defaults. Those premiums typically fall somewhere between about 0.22% and 1.10% of the loan amount per year, depending on things like the borrower’s credit score and the size of the down payment. The point isn’t to eliminate risk; it’s to reshape it—to bring the GSE’s loss exposure on a high-LTV loan closer to what it would be on a lower-LTV loan. The typical coverage levels are designed to do just that: for example, reducing exposure on an 85 LTV mortgage by about 12%, a 95 LTV mortgage by about 30%, and a 97 LTV mortgage by about 35%.

The catch is that this is long-tail insurance. Most policies never produce a claim. Borrowers either keep paying, or they build enough equity that the insurance goes away—often through refinancing, home price appreciation, or amortization. And the law requires automatic cancellation once the loan-to-value hits 78%. So the economics hinge on a handful of variables that only really show their teeth in a downturn: default rates (tied to unemployment and home prices) and severity (how much is actually lost when a foreclosure happens). In normal times, insurers might run loss ratios in the 15–25% range. In a true crisis, those numbers can blow past 200%.

The industry today is small and concentrated. There are six active private mortgage insurers: Arch, Enact, Essent, MGIC, NMI, and Radian. That oligopoly didn’t happen by accident—it was forged in the financial crisis, when major players like PMI Group, Triad Guaranty, and Republic Mortgage Insurance either went into run-off or failed. At the moment, private mortgage insurers (including legacy books still held by companies no longer writing new policies) account for about 55% of insurance-in-force, with the FHA holding roughly 45%.

That split between private MI and government insurance (mostly FHA and VA) moves around with pricing, underwriting standards, and politics. Before the crisis, private MI dominated high-LTV lending—nearly 60% of the total in 2000 and about 77% in 2007. The crisis crushed that share, and FHA stepped into the vacuum. But since private MI hit its post-crisis low around 2009, it has steadily regained ground.

If you’re looking at MGIC as a business, the key idea is this: it’s a toll collector embedded in the housing finance system. MGIC doesn’t originate loans. It makes a massive swath of loans eligible to exist inside the conforming market. And as long as Americans keep buying homes with less than 20% down—and as long as Fannie and Freddie remain the center of gravity—someone will keep collecting that toll.

III. MGIC's Origins & the Birth of an Industry (1957–1980s)

In 1957, a 47-year-old Milwaukee real estate attorney named Max H. Karl kept running into the same problem: clients who could afford the monthly payment still couldn’t clear the Federal Housing Administration’s maze of rules and waiting periods. Karl’s conclusion was simple. If the government’s guarantee was too slow and too bureaucratic, there was room for a private alternative.

So he started one.

MGIC—Mortgage Guaranty Insurance Corp.—became the first modern private mortgage insurer. The product was straightforward but powerful: MGIC would insure low down payment mortgages against foreclosure losses. That protection made lenders far more willing to approve borrowers who didn’t have a full 20% down payment.

Karl’s beginnings were as scrappy as the idea was ambitious. He raised $250,000 from investors—famously including his barber—and got MGIC licensed in Wisconsin in February 1957. The next month, the company insured its first four home mortgages. The number feels almost comically small now, but it was enough to prove the model.

Karl’s real insight wasn’t just that this insurance could exist—it was that it could be faster and cheaper than the FHA. MGIC went public in 1961 and built its process around speed: using the information lenders already collected, MGIC could approve an insurance application in a day or two. The FHA, by contrast, could take four to six weeks. MGIC also insured low down payment mortgages at roughly half the cost to the homebuyer compared with FHA insurance.

And the early years looked like a dream. Karl later summed up the prevailing confidence with a line that, in hindsight, reads like a warning label: “The only thing that would hurt us would be a depression, which seemed remote.” With foreclosures low in the post–World War II era, the risk felt manageable. Beginning in 1958, MGIC’s profits rose every year. By 1967, MGIC controlled around 70% of the private mortgage insurance market in the United States.

Competition arrived quickly—there were ten rivals by 1973—but MGIC stayed out front. In 1972, about $11 billion of private residential mortgage insurance was written, and MGIC wrote $7.5 billion of it. Claims were tiny, too: foreclosure losses of roughly $2 million or less per year. In other words, the machine was humming—premiums in, losses barely noticeable.

Then came MGIC’s first real reminder that “insurance” is a risk business, and that growth tempts companies into places they don’t fully understand. In the early 1970s, MGIC pushed beyond its core: mobile home mortgages, commercial property mortgages, and even a secondary mortgage market operation that left it borrowing short-term to finance inventory. In 1974, the cracks showed. Those ventures soured, the balance sheet got stretched, and MGIC posted a $1.9 million net loss.

The response was decisive. MGIC reorganized: Max Karl moved into the chairman role, and his nephew, Gerald Friedman, took over day-to-day operations as president. The company stopped writing insurance on mobile homes and shut down the secondary market operation.

That episode planted a theme that would echo through MGIC’s history: the core mortgage insurance business could be solid, even exceptional—but “adjacent” businesses often weren’t. Sometimes the hard way is the only way a company learns where its edge truly is.

The 1980s brought a different kind of shock—one that had nothing to do with underwriting. In 1982, Baldwin-United Corp. bought MGIC. A year later, Baldwin-United filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. MGIC, importantly, remained in compliance with all insurance capital requirements, but the optics were brutal: Karl had sold MGIC for $1.2 billion—an enormous sum at the time—only to watch the parent company implode almost immediately.

The rescue came from an unexpected ally. In 1985, Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company made a $250 million investment and, together with existing MGIC management, helped create the “new” MGIC. With Northwestern Mutual’s backing, Karl and a group of MGIC executives repurchased the business from Baldwin-United. The newly independent MGIC returned to large profits by 1989.

Max Karl retired in 1990. In 1991, MGIC Investment Corp. became a publicly traded company. The company that began with $250,000—friends, local investors, and one famously committed barber—had grown into a public enterprise worth billions, and it had effectively created an industry along the way.

IV. The Long Boom: Growth, Competition & Complacency (1990s–2006)

The 1990s and early 2000s were golden years for MGIC—maybe too golden. Home prices kept climbing, defaults stayed low, and the company produced steady profits. After enough quarters like that, it was easy—dangerously easy—to start believing the mortgage insurance business had been tamed.

Curt Culver rose with the boom. He joined MGIC in 1982, became President and Chief Operating Officer in 1996, and then on January 1, 2000 stepped into the CEO role. In 2005, he added Chairman. By the time the housing machine was really humming, MGIC had an industry veteran at the helm and a franchise that looked bulletproof.

The demand backdrop was perfect. The refinancing waves of the late 1990s and early 2000s—powered by falling rates and rising home values—kept the MI flywheel spinning. When homeowners refinanced, their old mortgage insurance policies fell away. But the new mortgages needed new policies, and if a borrower cashed out equity, the fresh loan could come with richer premiums. It was a high-volume, low-loss environment—the kind that makes an insurer look like a genius.

And with that volume came a crowd. Competitors like Radian, PMI Group, Genworth, and others pushed hard for share. To win, you either price sharper, approve faster, or stretch a little further out on the risk spectrum. Over time, “a little” becomes “normal.”

The industry had seen this movie before. In the 1980s, home prices stagnated and even fell in many places. During the prior boom, MGIC had cut prices and loosened standards to protect its dominance, and by the mid-1980s those choices boomeranged. As the economy weakened and property values deflated, defaults rose, losses mounted, and the number of private mortgage insurers shrank from 14 to seven by the late 1980s.

That history should have been a scar the whole industry could feel. Instead, by the mid-2000s, it was a faint memory—overshadowed by a newer, more seductive belief: housing prices wouldn’t decline on a national basis.

That wasn’t just cocktail-party optimism. It was embedded in risk models and underwriting assumptions. And it showed up in what MGIC was willing to insure heading into the crisis. Going into 2008, borrowers with FICO scores below 660 made up 27% of MGIC’s insurance book; today, it’s about 7%. No- or low-documentation loans were roughly 15% of new business in 2005–2007; today they’re effectively gone. High debt burdens were common too: debt payments above 45% of income were 38% of 2005–2007 new business, versus 14% over the past three years. Very low down payments—less than 5%—were 38% back then, versus 15% recently. Investor loans were a slice of that era’s volume as well—about 3%—and today MGIC reports essentially none. In fact, MGIC has said that 43% of its claims payments since 2008 came from loan types it hasn’t insured in a decade.

The takeaway isn’t any single statistic. It’s the pattern: loans increasingly stacked risk on risk—lower credit quality, thin documentation, minimal borrower equity, heavier monthly obligations. Those combinations can look fine when prices only go up. They turn lethal when the cycle flips.

MGIC also made “diversification” bets that, in reality, concentrated the same housing risk in a different wrapper. The company invested in Credit-Based Asset Servicing and Securitization (C-BASS), an operation tied to troubled mortgages. As the market deteriorated, that exposure didn’t hedge MGIC’s core mortgage insurance risk—it compounded it.

In hindsight, the warning signs were loud. Alt-A lending grew. Documentation got thinner. Piggyback structures proliferated. But when losses are near zero and competitors are fighting for every sliver of market share, restraint feels like surrender. Few wanted to be the first to tighten—and in mortgage insurance, being late to tighten is how you end up paying claims for a decade.

V. The Financial Crisis: MGIC's Near-Death Experience (2007–2012)

The reckoning began in 2007—slowly at first, then all at once. Early delinquencies showed up where you’d expect: the riskiest subprime and Alt-A loans. But what started at the edges didn’t stay there. By late 2007, it was obvious MGIC was staring at a kind of loss event the company—and the whole private MI industry—had never lived through.

By mid-2008, the financial statements were turning into a weekly gut punch. MGIC lost $97.9 million in Q2 2008 as foreclosures surged. That was a swing from earning $76.7 million in the same quarter the year before. On an investor call, CEO Curt Culver tried to put a boundary around the damage, suggesting the company might land on the low end of prior guidance—closer to $1.8 billion of paid claims for 2008 rather than $2 billion.

Even that proved wildly optimistic.

Since 2008, MGIC has paid nearly $16 billion in claims on loans written in 2008 and earlier. To put that in perspective, MGIC carries roughly the same amount of insurance in force today as it did at the end of 2007. The company essentially lived through an event that “destroyed” its balance sheet over and over—and had to keep operating anyway.

The losses didn’t stop after a bad year or two. MGIC didn’t post an annual profit between 2007 and 2014. Seven straight years in the red. For an insurer—where confidence and capital are the product—this wasn’t just painful. It was existential.

And the crisis didn’t hit from one direction. It came as a cascading, multi-front disaster.

First, MGIC’s loss reserves were nowhere near enough. The models that had worked for decades were built for regional downturns, not a synchronized national housing collapse. When home prices fell broadly across the country, “diversification” stopped diversifying. Correlations went to one, and the math that made the business feel stable snapped.

Second, regulators tightened the screws just as MGIC’s capital was being chewed up by claims. Insurance is permissioned. If you can’t meet capital requirements, you lose the right to write new business. And for a mortgage insurer, losing the ability to write new policies can trigger a death spiral: no new premiums, shrinking franchise, rising doubts, and less and less room to maneuver. That dynamic ultimately claimed competitors like PMI Group and Triad Guaranty.

Third—and most dangerously—the GSEs could have cut MGIC off. If Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac decide you’re no longer eligible, you’re effectively out of the conforming mortgage market. Starting in 2007, as record claims threatened MGIC’s regulatory capital, the company worked with the Wisconsin Office of the Commissioner of Insurance and Fannie Mae on a structure that let it keep underwriting: MGIC reactivated and recapitalized its original underwriting entity (“Old MGIC”) to write new business, while steps were taken to reduce claim exposure in the newer operating company (“New MGIC”).

Meanwhile, MGIC did what companies do when survival is the only KPI left. It raised capital through multiple offerings of stock and convertible notes, sold its interest in Sherman Financial Group, and stopped some late-bubble practices—like writing insurance on pools of mortgages.

The stock chart captured the brutality in one line. From a pre-crisis high above $70, MGIC fell below $2 in early 2009. Shareholders were diluted through emergency raises. Convertible debt came with punitive terms. None of it was elegant. It was triage.

Culver later put it plainly: “I didn't know if the company could make it. Still, everyone stayed. We kept a great team and worked through the issues.”

All around MGIC, competitors were breaking. In October 2011, Arizona regulators seized PMI’s main subsidiary and cut claim payouts to 50%, deferring the remainder. Soon after, PMI filed for bankruptcy. Triad Guaranty—another long-time private mortgage insurer—stopped writing new business in 2008, then ultimately filed for Chapter 11 and entered run-off.

So why did MGIC survive when others didn’t?

One big reason was simply its position in the system. MGIC’s scale and relationships made it valuable infrastructure. Regulators and the GSEs had incentives to keep the largest private MI operating; the alternative was pushing even more of the market into government programs and shrinking the private side when it was already under stress.

Another was continuity. MGIC kept writing new insurance through the worst of the Great Financial Crisis. That mattered. Staying open meant the company could rebuild with post-crisis underwriting standards—vintages that would be fundamentally safer than the loans that were blowing up.

And Culver’s approach was not to spin, but to grind. Raise capital even when it hurt. Sell what wasn’t core. Stay close to regulators and the GSEs. Keep the franchise intact.

That mindset carried into the transition years. As MGIC looked for a way to move from survival to recovery, Patrick Sinks—who would soon step into the CEO role—pushed the organization to think beyond the immediate fire. “We were going through some pretty interesting times in 2007, 2008, 2009,” Sinks said. “As the foreclosure crisis was unfolding and we kept paying claims, our capital was shrinking rapidly. It was imperative to look further ahead.” In early 2013, he formed a business strategy team and told them to focus on what MGIC needed to look like in the coming years, not just what it needed to do to get through the quarter.

Just as important, MGIC kept functioning like a real company. It continued to serve lenders, process applications, and pay legitimate claims—even while it was hemorrhaging money. That preserved something that doesn’t show up cleanly on a balance sheet: trust. And when the market finally stabilized, that trust—and the ability to keep writing new business—was the difference between a company in run-off and a company with a future.

VI. The Turnaround: Rebuilding from the Ashes (2012–2016)

The turnaround didn’t arrive with a single announcement. It arrived the way housing itself recovered—slowly, unevenly, and then suddenly enough that you could feel the cycle turning. By 2013, home prices had stabilized and started rising again. MGIC wasn’t “healthy” yet, but it had stabilized its capital position enough to stop operating like a burn ward and start thinking about growth.

This was also when the company’s leadership story came full circle. Curt Culver had been in mortgage insurance since 1976, joined MGIC in 1982, and rose through the ranks to become President in 1999 and CEO in 2000. Patrick Sinks, meanwhile, had been running critical parts of the franchise for years—serving as Executive Vice President of Field Operations starting in 2002, then becoming President and COO in January 2006.

In 2015, the handoff from Culver to Sinks marked a real shift in posture: from “keep the doors open” to “build the next MGIC.” Sinks framed it as a continuation, not a reinvention: “I am honored to continue to build on the strong foundation that Curt has established. His strategic vision, thoughtful leadership, business acumen and personal style have enabled MGIC to be a leader in our industry. Our company is well positioned for the future and our management team is as strong as it has ever been.”

But the most important development of this era wasn’t a CEO transition. It was a structural reset imposed from the top of the housing finance system.

On April 17, 2015, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac published revised Private Mortgage Insurer Eligibility Requirements—PMIERs. The FHFA, acting as conservator of the GSEs, directed them to align and strengthen the standards private mortgage insurers had to meet in order to remain eligible to insure loans the GSEs acquired or guaranteed. The core change was simple and severe: new, risk-based capital requirements designed for a world where another 2008 wasn’t “unthinkable.”

Then the ratchet tightened further. PMIERs and the subsequent PMIERs 2.0 changes nearly doubled the capital requirement for the industry. PMIERs was revised again in 2018 and again in 2020, incorporating lessons from the downturn. Since implementation, the framework has more than doubled the amount of capital each mortgage insurer is required to hold.

This is where MGIC’s story flips from defense to advantage.

For MGIC, PMIERs was absolutely a burden—until it became a moat. The new regime made the business dramatically harder to enter and far harder to play fast and loose. A would-be startup mortgage insurer would need to raise over $1 billion of capital before writing meaningful business, go through a multi-year GSE approval process, build technology integrations across a sprawling lender ecosystem, and somehow convince counterparties it could survive a full credit cycle—all before earning real revenue.

In other words: the easy version of private mortgage insurance died in 2008. PMIERs made sure it stayed dead.

The industry consolidated into a tighter group of survivors. Six active insurers remained—MGIC, Radian, Arch, Enact (formerly Genworth’s MI business), Essent, and National MI—and together they emerged as a post-crisis oligopoly. The failures of PMI, Triad, and Republic, combined with the higher capital bar, effectively shut the door on casual new entry.

And the remaining players didn’t just meet the rules—they built buffers above them. Keefe, Bruyette & Woods calculated that the five monoline mortgage insurers had an average PMIERs cushion of about 70% at year-end 2022.

Back in the turnaround window, the mechanics of MGIC’s recovery were less flashy, but decisive: retained earnings as crisis-era losses rolled off, additional equity and debt raises, and a hard pivot to conservative underwriting on new business. By 2016, MGIC was consistently profitable again—writing new insurance at attractive returns and steadily replacing a battered, pre-2008 book with post-crisis vintages that had materially stronger credit characteristics.

VII. The Modern Oligopoly: MGIC's Dominant Position (2017–2023)

By the late 2010s, the industry had finally settled into its post-crisis shape. PMIERs had raised the drawbridge, the weak players were gone, and the survivors weren’t eager to re-learn the lessons of 2008. With just six serious competitors controlling nearly the entire market, private mortgage insurance started behaving the way a capital-intensive, tightly regulated business tends to behave: rationally. Pricing still mattered, but the competition became more “gentlemanly,” and far more disciplined.

In that environment, market share didn’t swing wildly—but MGIC still managed to climb. In 2023, it ranked as the fourth-largest underwriter. In 2024, it moved back to the top, with new insurance written rising to $55.7 billion from $46.1 billion.

That momentum carried forward. MGIC was No. 1 among private mortgage insurers by market share in Q2 2025, strengthening its lead during the quarter. Its underwriting unit wrote $16.4 billion of NIW, and the company finished the quarter with a 20.1% share of the market.

A big part of that staying power is distribution—how MGIC actually wins business. As CEO Tim Mattke put it, “While pricing is an important component of market position, it’s just one component, and we believe that we have advantages that allow us to outperform our price position.” In other words: you can’t buy this market forever with price cuts. Not when everyone is capital constrained, and not when lenders care about reliability as much as rate.

MGIC’s advantage starts with relationships. Lender partnerships get built over decades, and they come with real switching costs. Moving meaningful volume from one mortgage insurer to another isn’t like changing a vendor on an expense line. It takes integration work, compliance review, process changes, and rebuilding the muscle memory between two organizations. Most large lenders keep multiple MI relationships for redundancy, but that’s not the same as easily flipping the bulk of production elsewhere.

Technology makes those relationships even stickier. Over time, MGIC and its peers have poured investment into automated underwriting tools and integrations that plug directly into lenders’ loan origination systems. Once those pipes are installed and running smoothly, lenders are naturally reluctant to rip them out—especially in an industry where speed and certainty at the point of sale can make or break a borrower experience.

At the same time, the regulatory backdrop keeps evolving—but in a way that tends to reinforce the moat. “We are proud of the critical role PMI plays in the housing finance system,” Mattke said. “PMIERs operational and risk-based capital requirements provide a strong foundation to serve low down payment borrowers while protecting the GSEs and taxpayers from undue mortgage credit risk.” Under updated FHFA standards, changes will be phased in over 24 months, with a fully effective date of September 30, 2026.

Then came the strange gift and curse of 2020 and 2021: the refinance boom. Record-low mortgage rates triggered a wave of refinancing that caused many existing policies to cancel early—bad for persistency—but it also created a surge of new policies on replacement loans. MGIC’s persistency rate ended 2020 at 60.5%, down sharply year over year, even as new insurance written jumped to $33.2 billion.

But the real payoff from that period wasn’t just volume—it was the quality of the book MGIC built. Borrowers who refinanced in 2020 and 2021 locked in historically low monthly payments. That improved cash flow, lowered default risk, and created what the industry loves most: durable, high-quality policies that can stay on the books for a long time.

And after more than a decade of simply fighting to rebuild capital, MGIC was finally in a position to do something that signals true health: give money back. The company restarted capital returns after a 15-year pause, and in 2024 returned roughly $700 million to shareholders through repurchases and dividends—about a 92% payout of the year’s net income.

VIII. The Rate Shock Era: Navigating 2022-2025

Starting in 2022, the Federal Reserve’s rapid rate hikes flipped the mortgage market—and MGIC’s operating environment—on its head. Rates kept climbing through 2023: by late January, the average 30-year mortgage was around 6.5%, and by October it touched nearly 7.8%, the highest level since 2000.

The effect was immediate and brutal. Higher monthly payments priced out would-be buyers and froze existing homeowners in place. If you already had a 3% mortgage, you weren’t moving unless you absolutely had to. Mortgage originations fell hard—and for MGIC, that meant a much smaller pool of new loans that needed insurance.

You can see the strain in the size of the book. MGIC’s insurance in force slipped about half a percent year over year to $291 billion. Management also acknowledged that the company gave up some market share in new insurance written in the first quarter of 2024. The broader headwinds—high rates and an affordability squeeze—kept pressing down on the whole origination ecosystem.

But the rate shock also produced the kind of “good problem” mortgage insurers love: persistency exploded. With refinancing suddenly uneconomic, policies that normally would have disappeared stayed put. Industry persistency jumped to 81% at the end of 2022, up from 63% a year earlier. As one industry observer put it, most loans in the current MI portfolios carried mortgage rates hundreds of basis points below where market rates sat at year-end 2022—shrinking the refinance pool to almost nothing.

That’s the “golden cohort” dynamic: the 2020–2021 vintages. These loans were generally high quality, written under post-crisis discipline, and then refinanced into historically low payments. Now they’re effectively glued to the books. For MGIC, that means longer-lasting premium streams and, as long as the economy holds up, relatively low claims.

MGIC’s own persistency numbers tell the story: 82.2% at December 31, 2022, 86.1% at December 31, 2023, and 85.3% as of September 30, 2024.

The vintage mix also shows how the company is spread across multiple origination years, rather than being dangerously concentrated in a single boom cohort. In the portfolio, 2021 is the largest slice at 21.8%, followed by 2022 at 18.8% and 2024 at 16.7%. That spread matters in mortgage insurance: diversification is one of the few free lunches—until it isn’t.

The other pillar of resilience is capital. Years of operating under PMIERs left MGIC with a real buffer, not just compliance. By the end of Q3 2024, PMIERs excess assets stood at $2.5 billion.

And MGIC has been leaning more on reinsurance as a way to manage both tail risk and regulatory capital. The company agreed to terms on a 40% quota share transaction with a group of unaffiliated reinsurers, covering most of its 2025 and 2026 new insurance written.

Even in a high-rate world, the business didn’t stop—it just changed shape. In Q4 2024, MGIC wrote about $16 billion of new insurance, and roughly $56 billion for the full year, up about 21% from the prior year. Volume recovered somewhat from the 2023 lows, but the driver was the purchase market, not refinancing.

From here, it’s a waiting game—with more variables than just mortgage rates. As CEO Tim Mattke put it, “It’s tough to know exactly what’s specifically going to happen on tariffs…but I think when we think about our business and our pricing, we think about a wide range of different sort of scenarios and environments that we can perform under. We have to take that into account when we do pricing and that’s consistent, no matter if it feels like it’s a benign environment, if it’s something that feels like it’s changing more now.”

IX. Strategic Inflection Points & What Made the Difference

Look back over MGIC’s history and you can see four moments where the company’s fate—and the structure of the entire industry—pivoted.

Inflection Point #1 (2008-2009): Survival Decisions During the Crisis

In the darkest stretch of the financial crisis, MGIC’s goal wasn’t growth. It was permission to keep existing.

That meant doing a bunch of things that were brutal in the moment but decisive in hindsight: raising emergency capital that crushed shareholder value, protecting GSE eligibility like it was oxygen, and continuing to pay legitimate claims even as the company’s capital base was being eaten alive. The alternative wasn’t a worse quarter. It was the end of the franchise—exactly what happened to PMI Group and Triad Guaranty.

MGIC took enormous losses as mortgage defaults surged, but unlike several competitors, it made it through without government assistance.

And the counterfactual matters. If MGIC had failed, the private MI industry would have been smaller still, government programs likely would have expanded further to fill the gap, and the post-crisis competitive map would have looked completely different. MGIC’s survival didn’t just save MGIC—it shaped the industry that emerged afterward.

Inflection Point #2 (2013-2015): PMIERs Implementation

PMIERs arrived as a new set of rules, but it functioned like a filter.

At first, it was just more pressure—higher capital requirements and tighter standards layered onto a still-healing industry. But over time, that burden turned into a moat. MGIC didn’t just comply; it rebuilt credibility by meeting and exceeding the tougher requirements, reinforcing that it could operate in a world where the GSEs and regulators were no longer willing to trust anyone’s models.

PMIERs is a big reason the oligopoly exists today. And MGIC, with its scale and relationships, was far better positioned to clear the new bar than smaller competitors—and miles ahead of any hypothetical new entrant.

Inflection Point #3 (2020-2021): The Low-Rate Bonanza

The refinancing boom handed the industry volume on a platter. The question was whether insurers would repeat the old playbook: chase growth, stretch standards, and hope nothing breaks.

MGIC didn’t. It kept underwriting discipline even while writing record new business. And the difference between 2007 and the post-crisis era wasn’t subtle—it was foundational.

The result was the “golden cohort”: policies with strong credit quality, bigger equity cushions as home prices rose, and borrowers locked into low mortgage rates that made those loans far more likely to stick around for years.

Inflection Point #4 (2022-Present): The Volume Drought

When rates spiked and originations collapsed, MGIC didn’t try to buy market share.

Instead, it leaned into discipline—protecting price, prioritizing returns, and letting high persistency do what it does best: keep premium streams in force while the market waits for a better volume environment.

Management has been explicit about that tradeoff. As CEO Tim Mattke put it, “I feel good about this quarter, just like we felt good about last quarter as well. I think as we move through the year here, we have a wide customer base that gives us an opportunity to really be able to get business when we want to be able to win the business and deploy the capital at good returns.”

X. The Business Deep Dive: How MGIC Really Works

To understand MGIC, you have to get comfortable with a business that looks like classic insurance—premiums in, claims out—but behaves very differently under stress. Most years, it’s steady and almost boring. In the wrong year, it can turn into a slow-moving avalanche.

The Economic Engine

At its core, MGIC collects premiums over time, invests the float, and then pays claims when borrowers default and the lender takes a loss. The whole model boils down to a few ratios that tell you whether the business is compounding quietly or taking on water:

- Loss ratio: claims paid divided by premiums earned. In normal times, it might sit in the 15–25% range. In a true housing crisis, it can blow past 200%.

- Expense ratio: operating expenses divided by premiums. This is where scale shows up fast.

- Combined ratio: loss ratio plus expense ratio. The simple goal is to keep it below 70% so the business produces attractive underwriting returns.

In 2024, MGIC reported revenue of $1.21 billion, up from $1.16 billion the year before, and net income of $762.99 million, also up year over year.

Why Scale Matters

Mortgage insurance is a scale game, not because bigger is always better, but because the fixed costs are real and the relationships are sticky. MGIC’s size buys it a handful of compounding advantages:

-

Fixed-cost absorption: the technology stack, compliance burden, and GSE interfaces don’t scale neatly with volume. Bigger books can carry those costs more efficiently.

-

Data advantages: decades of performance and claims history across millions of policies feed better underwriting and pricing decisions.

-

Relationship leverage: lenders want counterparties they trust will be there in a downturn—when claims are spiking and everyone else is looking for ways to delay or deny.

-

Capital efficiency: with scale, MGIC can access more sophisticated reinsurance and capital management tools than a smaller competitor could justify.

The Liability Structure

Mortgage insurance is long-tail. Policies can theoretically remain in force for the life of the mortgage—up to 30 years—though most end earlier through refinancing, a home sale, or cancellation once the borrower reaches 78% loan-to-value.

That timing matters because MGIC doesn’t “get paid” the same way on every policy. Single-premium policies are collected upfront and then earned over the estimated life of the policy. Monthly and annual premium policies come in over time. In any given year, a large share of premiums earned usually comes from policies written in prior years.

This is one of the most important ideas in the whole business: MGIC’s existing book can generate premium income for years even if new volumes slow. The question is whether credit conditions stay benign enough that claims don’t overwhelm that stream.

Customer Dynamics

The customer setup is a little unusual—and it explains why distribution is everything:

- Lenders choose the mortgage insurer

- Borrowers pay the premiums (monthly or upfront)

- The GSEs regulate what’s acceptable

Most borrowers don’t know which insurer is behind their loan, and they generally can’t switch once the policy is in place. That makes this a B2B2C business where lender relationships—and operational execution with those lenders—are the real battlefield.

Reinsurance and Risk Transfer

After the financial crisis, MGIC leaned hard into reinsurance as a core risk-management tool. The point isn’t just to reduce losses in a stress scenario—though that’s part of it. Reinsurance can also reduce the risk-based capital MGIC is required to hold, which can improve returns on that capital. The tradeoff is that reinsurance has a price, and availability and cost move with market conditions.

Today, 79% of MGIC’s book is covered by quota share reinsurance. Its insurance-linked notes provide another $532 million of potential loss coverage. And regulators grant MGIC $1¼ billion of capital credit for its reinsurance.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

1. Threat of New Entrants: VERY LOW

If you’re imagining a fintech showing up and “disrupting” mortgage insurance, here’s the problem: PMIERs. The capital you need just to get in the game is enormous, and it’s not optional. You can’t write meaningful business without meeting the GSEs’ risk-based capital rules.

And even if you had the money, you’d still have to clear a multi-year GSE approval process, build lender relationships from scratch, and pay the very real cost of integrating into lenders’ tech stacks. Most importantly, you’d have to convince the market you can survive a credit cycle. The last time new players successfully entered—Essent and National MI—was in the unique post-crisis window when incumbents were wounded and the system needed fresh capacity.

2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers: LOW

MGIC’s “suppliers” are mostly capital and risk transfer. Capital markets are broad and competitive, reinsurers have plenty of alternatives to compete with each other, and the talent pool—while specialized—exists thanks to the industry’s concentration in a few hubs. No single supplier has MGIC over a barrel.

3. Bargaining Power of Buyers: MODERATE-HIGH

On the other side of the table are the lenders. The biggest ones—Wells Fargo, Rocket Mortgage, United Wholesale Mortgage—move real volume, and that gives them leverage. They can steer flows between insurers and push for sharper pricing, better turn times, and better service.

But that leverage has limits. Lenders don’t want to be dependent on one MI provider; they need multiple relationships for capacity, continuity, and risk management. And the borrower—the one actually paying the premium—generally doesn’t choose the insurer and often doesn’t even know which company is providing it. So the “buyer” is powerful, but not all-powerful.

4. Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE

Private MI isn’t the only way to finance a high-LTV borrower. The substitutes are real:

- FHA/VA loans: government-backed alternatives that compete for the same borrower

- Piggyback loans: 80-10-10 structures that avoid MI by adding a second mortgage

- Portfolio lending: banks keeping loans on balance sheet instead of selling to the GSEs

Pricing is where the competition shows up. At current FHA and PMI insurance rates, FHA can be cheaper than a GSE loan with PMI for borrowers with lower FICO scores. For higher FICO borrowers, conventional plus PMI is often cheaper. Since 2009, FHA mortgage insurance premiums have risen faster than LLPAs and PMI, and that shift has helped private MIs win share among higher-credit high-LTV borrowers. Short of a major change—like a big increase in GSE guarantee fees or LLPAs, or a structural shift in FHA—PMIs have a strong runway to keep growing.

Still, there’s one giant constraint on substitution: the GSE charter requirement. If a conforming loan goes over 80% LTV, it needs credit enhancement. As long as Fannie and Freddie remain the center of gravity in mortgage finance, private MI keeps its seat at the table.

5. Competitive Rivalry: MODERATE-LOW

“The broader mortgage insurance market remains healthy with disciplined underwriting and stable pricing,” said Nicolas Papadopoulo, Arch CEO.

That’s what an oligopoly sounds like when everyone remembers 2008. With six serious players, competition is real—but it’s bounded. Capital costs and GSE oversight put a floor under how aggressive pricing can get, and market share tends to move slowly. The industry learned—painfully—that loose underwriting doesn’t just create a bad quarter; it can end a company.

So rivalry shows up less as a price war and more as execution: service levels, speed, tech integration, and deep lender relationships.

Overall Industry Assessment: A highly attractive structure for incumbents—especially scaled, proven survivors like MGIC.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Analysis

Power #1: Scale Economies ★★★★★

MGIC is a classic scale business: the big costs don’t rise linearly with volume. The technology stack, compliance infrastructure, and ongoing work to stay integrated with the GSE ecosystem get spread across a massive policy base, driving down cost per policy and improving operating leverage. It’s also a notably lean operation—about 555 employees overseeing a book of more than $300 billion of insurance in force.

Power #2: Network Economics ★★

Mortgage insurance doesn’t really compound value through direct network effects. One policy doesn’t make the next policy inherently more valuable. The closest thing to a network effect is indirect: once you’re deeply embedded with a wide range of lenders, it becomes easier to win additional lender relationships. But this is incremental, not the core engine.

Power #3: Counter-Positioning ★

Counter-positioning is hard to pull off here because the system is permissioned. Disrupting private MI would require regulators and the GSEs to accept a fundamentally different approach to credit enhancement—something that doesn’t happen quickly. FHA could theoretically counter-position against private MI, but it’s constrained by politics and policy priorities.

Power #4: Switching Costs ★★★★★

"Last quarter, I alluded to with our broad customer base, which we think is sort of the broadest in the industry, that we're price neutral with the market and the risk-based pricing world, we're going to end up with sort of higher market share overall," CEO Tim Mattke said.

For lenders, switching costs are real and sticky. MGIC is wired into lender workflows through deep tech integrations, master policy agreements, and operational processes that take time and effort to replace. Layer in the complexity of GSE eligibility and the relationship capital built over years, and “just move the business” becomes a multi-quarter project.

For borrowers, switching is essentially impossible once a policy is written—until the loan is refinanced or the insurance cancels.

Power #5: Branding ★★

Brand is muted in a B2B2C model where the borrower pays but doesn’t choose. Most homeowners couldn’t tell you who insures their mortgage, and they don’t care—until something goes wrong. Where the brand does matter is with lenders and the broader system: MGIC’s decades-long history, and the fact that it survived the crisis, creates credibility that’s hard to manufacture.

Power #6: Cornered Resource ★★★

GSE eligibility is a quasi-cornered resource. It takes years, demands significant capital, and still doesn’t guarantee success. On top of that, MGIC’s long-standing lender relationships function like another scarce asset: you can’t replicate decades of trust and operational familiarity on a startup timeline.

Power #7: Process Power ★★★★

"We all believe in helping families achieve and sustain homeownership. That's our No. 1 priority. And we all believe that the best way to accomplish that is by doing the right thing—that was Curt's mantra. That sounds simple, but there have been occasions where doing the right thing was certainly not doing the popular thing. We have a leadership responsibility to our co-workers and customers to operate in a way that provides long-term sustainability. That's what has allowed us to survive the ups and downs of this business since 1957."

This is where MGIC’s near-death experience becomes an advantage. Underwriting discipline forged through multiple cycles, operational excellence in claims and servicing, and a risk culture shaped by 2008–2012 create real process power. That institutional memory shows up in decisions—what risks to avoid, how to price, when to prioritize durability over growth—in ways that are difficult for firms without that scar tissue to copy.

Primary Powers: Scale Economies + Switching Costs

Secondary Powers: Process Power, Cornered Resource

Durability: Very High—structural advantages that are not easily disrupted

XIII. Bull vs. Bear Case

The Bull Case

The case for MGIC is built on a few big, compounding advantages.

An oligopoly with real barriers tends to create pricing power. This is a small, permissioned market. Six players control it, PMIERs makes entry brutally expensive, and everyone still remembers what happens when you underprice risk. That combination usually produces discipline, not chaos.

A fortress balance sheet that can take a hit. Years of operating under PMIERs forced the industry to stockpile capital, and MGIC has layered in reinsurance and tighter underwriting on top of that. In Q3 2024, MGIC reported about $200 million of net income, with an annualized return on equity of 15.6%—the kind of profitability that gives you options when the cycle turns.

The housing shortage is a long-term tailwind. The U.S. has underbuilt housing for years. If and when mortgage rates normalize, you don’t need heroic assumptions to imagine originations rebounding. MGIC doesn’t have to invent demand—it just has to be there when it comes back.

Capital returns can do a lot of the work. MGIC earned $763 million in 2024, up from $730 million in 2023. When a company can steadily retire shares while trading well below book value, buybacks become a quiet engine for per-share compounding.

Crisis-tested management and culture. This company has already stared down the worst housing downturn since the Depression and lived. In an industry like this, that scar tissue is an asset.

The Bear Case

The concerns aren’t hypothetical, either.

The addressable market could be structurally smaller. If higher rates and affordability constraints persist, and younger households delay or skip homeownership, mortgage volumes might not snap back the way they did in prior cycles.

FHA could keep taking share. When private credit tightens, government programs tend to expand. If FHA wins more of the high-LTV borrower, private MI growth gets capped—even if the overall housing market is healthy.

Regulation is the ultimate wild card. The private MI business exists at the pleasure of the GSE ecosystem. Major changes—GSE reform, different charter requirements, or some move to internalize credit enhancement—could reshape the playing field overnight.

Housing is still cyclical, and cycles still bite. Another recession, a spike in unemployment, or severe regional downturns could generate meaningful losses, even with better underwriting than the 2005–2007 vintages.

Capital intensity can throttle returns. PMIERs forces MGIC to hold substantial capital, and that naturally limits ROE and the pace of growth versus a less regulated financial business.

Most Likely Scenario

A slow grind through a low-volume environment, with profitability held up by high persistency. Market share stays relatively stable among the Big 3 (MGIC, Radian, Arch). Shareholder returns continue mostly through buybacks. Then, whenever rates finally fall enough to restart refinancing and unlock buyers, the model’s operating leverage shows up fast—and earnings can inflect sharply.

XIV. Key Metrics to Watch

If you want a simple dashboard for MGIC, there are three places to look. Together, they tell you whether the machine is quietly compounding, starting to leak, or building pressure for the next turn in the cycle.

1. Insurance in Force (IIF) and Persistency

IIF is the base that generates premium revenue. And in a high-rate market, the main force pushing IIF up or down isn’t new production—it’s persistency. Most of the premiums MGIC earns in any given period come from policies written in prior years, so how long those policies stay in force is a first-order driver of revenue.

Watch for: A meaningful drop in persistency. That would likely mean rates have fallen enough to restart refinancing. That’s a mixed signal: good for new insurance written, but it also means the prized 2020–2021 “golden cohort” starts rolling off faster.

2. Loss Ratio and Delinquency Trends

This is the credit heart monitor. Premiums are great, but claims determine whether those premiums turn into real profitability. In Q3 2024, MGIC’s delinquency rate rose by 15 basis points to 2.24%, which management characterized as consistent with normal seasonal patterns.

Watch for: Delinquencies accelerating beyond seasonality—especially in the 2020–2023 vintages. That’s where you’d expect early warning signs if borrower stress is spreading.

3. PMIERs Excess Assets

PMIERs excess assets are MGIC’s regulatory cushion—the buffer above minimum requirements that signals both resilience and flexibility. It’s also what ultimately enables capital returns. At quarter-end, PMIERs excess assets were $2.5 billion.

Watch for: A material decline. That would tighten the company’s ability to repurchase shares and could foreshadow a need to preserve, or even raise, capital.

XV. The Bigger Picture: What MGIC Teaches Us

MGIC’s story offers lessons that travel well beyond mortgage insurance:

Lesson #1: Survival is the ultimate competitive advantage.

Getting through 2008–2012 didn’t just hurt MGIC. It permanently shrank the field. While several competitors either failed or went into run-off, MGIC stayed standing—and it did it without government assistance. In a permissioned, relationship-driven industry, simply being alive after the worst storm becomes a competitive edge that can take decades for anyone else to match.

Lesson #2: Regulation can create moats.

PMIERs started as a post-crisis crackdown. Over time, it became the drawbridge. What looked like a penalty turned into a barrier to entry—and a protective wall around the companies that could meet the standards, hold the capital, and earn the GSEs’ trust. The broader takeaway: in heavily regulated industries, rule changes don’t just raise costs. They can reshape the competitive map.

Lesson #3: Hidden infrastructure businesses can be incredible investments.

MGIC’s product is rarely celebrated, but it’s deeply enabling. Mortgage insurance helps borrowers clear the down payment hurdle, getting them into homes sooner with affordable, low-down-payment loans.

And yet most homebuyers barely register that MI exists—despite paying for it and relying on it. Businesses like this can feel “boring,” or even invisible, and that invisibility can cause them to trade at a discount to how strategically essential they are.

Lesson #4: Scale and distribution matter in financial services.

You can’t “just build an app” for mortgage insurance. Technology helps, but it isn’t the gate. The gate is capital, approvals, and embedded distribution. Any fintech entrant would be staring at years of GSE eligibility work, enormous capital requirements, and the slow, unglamorous grind of building lender relationships from scratch.

Lesson #5: Crisis memory is valuable.

MGIC underwrites differently because it almost died. Post-crisis conservatism isn’t a branding statement—it’s lived experience. MGIC has said that 43% of its claims payments since 2008 came from loan types it hasn’t insured in a decade. That’s what scar tissue looks like in policy form. Management teams that have survived a near-death experience tend to price risk, chase growth, and manage capital in fundamentally different ways than teams that haven’t.

Lesson #6: Patient capital wins in cyclical businesses.

MGIC was a brutal hold through the crisis—and a remarkable one coming out of it. Investors who bought shares in the $2–$5 range during the recovery earned extraordinary returns. The current low-volume environment isn’t a promise of a repeat, but it’s a reminder of how this works: in cyclical, capital-intensive businesses, the best opportunities often show up when the headlines are the worst and the patience required is the highest.

XVI. Epilogue: The Future of Homeownership & MGIC's Role

MGIC’s future is tied to something much bigger than MGIC: the future of American homeownership. And right now, that future comes with real headwinds.

Affordability is the obvious one. Home prices have outrun wages for decades, and the rate shock of the last few years has turned that gap into a wall. For many first-time buyers, the monthly payment is the problem, not the down payment. And for younger households in particular, homeownership has gotten harder, not easier.

Then there’s politics, which in housing finance is never background noise—it’s the soundtrack. Any administration can shift the rules of the game: adjust GSE policy, expand FHA programs, or push GSE reform that reshapes the entire system. On an earnings call, CEO Tim Mattke was asked about the possibility that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could be released from conservatorship, and what that might mean for MGIC. His answer was essentially that there are a lot of possible outcomes—but that a strong case can be made for keeping volume flowing through the GSEs to protect taxpayers, rather than shifting more of it to FHA. In that world, private mortgage insurers stand to benefit.

Technology is the perennial “maybe.” People can imagine blockchain-based structures, AI-driven underwriting, and new ways to package or transfer risk. But mortgage insurance is a permissioned, relationship-heavy, capital-intensive business. So far, no practical challenger has shown up with a credible path through the regulators, the GSEs, and the lender ecosystem.

Climate risk, though, is harder to hand-wave away. As disasters grow more frequent and severe, some regions—especially coastal markets and fire-prone areas—are already facing insurance availability and pricing crises. That can spill into mortgage markets, and mortgage markets are MGIC’s oxygen.

And yet, through all of it, the core reason mortgage insurance exists hasn’t changed. Americans still want to own homes. Most households still can’t realistically save a 20% down payment. And the housing finance system still needs someone to stand between what buyers can put down and what lenders—and the GSEs—will accept. For the foreseeable future, that “someone” will be MGIC and its handful of competitors.

“As we close another year on a high note with strong financial results in the fourth quarter while returning meaningful capital to our shareholders, I am looking forward to the opportunities that lie before us in the new year. With the solid foundation we have built, our leadership in the market, and our talented team, I remain confident in our ability to execute on our business strategies and achieve success for all of our stakeholders.”

MGIC survived the worst housing crisis since the Great Depression. It rebuilt capital, reset underwriting, and came out the other side in an oligopoly guarded by regulatory drawbridges. Whatever comes next—rates falling, housing thawing, or another left-field shock—MGIC looks built to absorb it.

For investors, that’s the real bet: not on one quarter or one rate cycle, but on the durability of the American housing finance system—and on MGIC’s place inside its plumbing.

XVII. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Long-Form Links & References:

-

MGIC Investor Relations & Annual Reports (mtg.mgic.com/investors) — MGIC’s 10-Ks from 2007–2024 are the clearest primary source for the crisis, the turnaround, and the post-PMIERs era.

-

PMIERs Documentation — The official Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac requirements that define what it takes to be an eligible private mortgage insurer today.

-

"The Big Short" by Michael Lewis — The most readable on-ramp to the housing bubble, the incentives that fueled it, and the unraveling that followed.

-

Urban Institute Housing Finance Policy Center Research — Thoughtful, data-driven work on mortgage finance, private MI, and the policy debate around the GSEs.

-

MGIC’s 2008–2012 Earnings Calls (available via archives) — A real-time record of how management described the situation as it deteriorated—and what they did to keep the company alive.

-

Industry Analysis: Keefe, Bruyette & Woods (KBW) MI Sector Reports — Specialist coverage that helps frame the MI industry’s structure, economics, and relative positioning.

-

Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) Reports on the MI Industry — The regulator’s view of the system, the rules, and the risks around Fannie and Freddie.

-

"The Housing Boom and Bust" by Thomas Sowell — A broader economic lens on the forces behind the bubble and the crash.

-

Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) Research & Statistics — The go-to source for origination volumes, market trends, and forecasts.

-

Journal of Housing Economics: Academic Papers on Mortgage Insurance — Deeper research on how MI shapes credit availability, homeownership, and risk in the housing system.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music