Matador Resources: The Permian Pure-Play That Got It Right

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

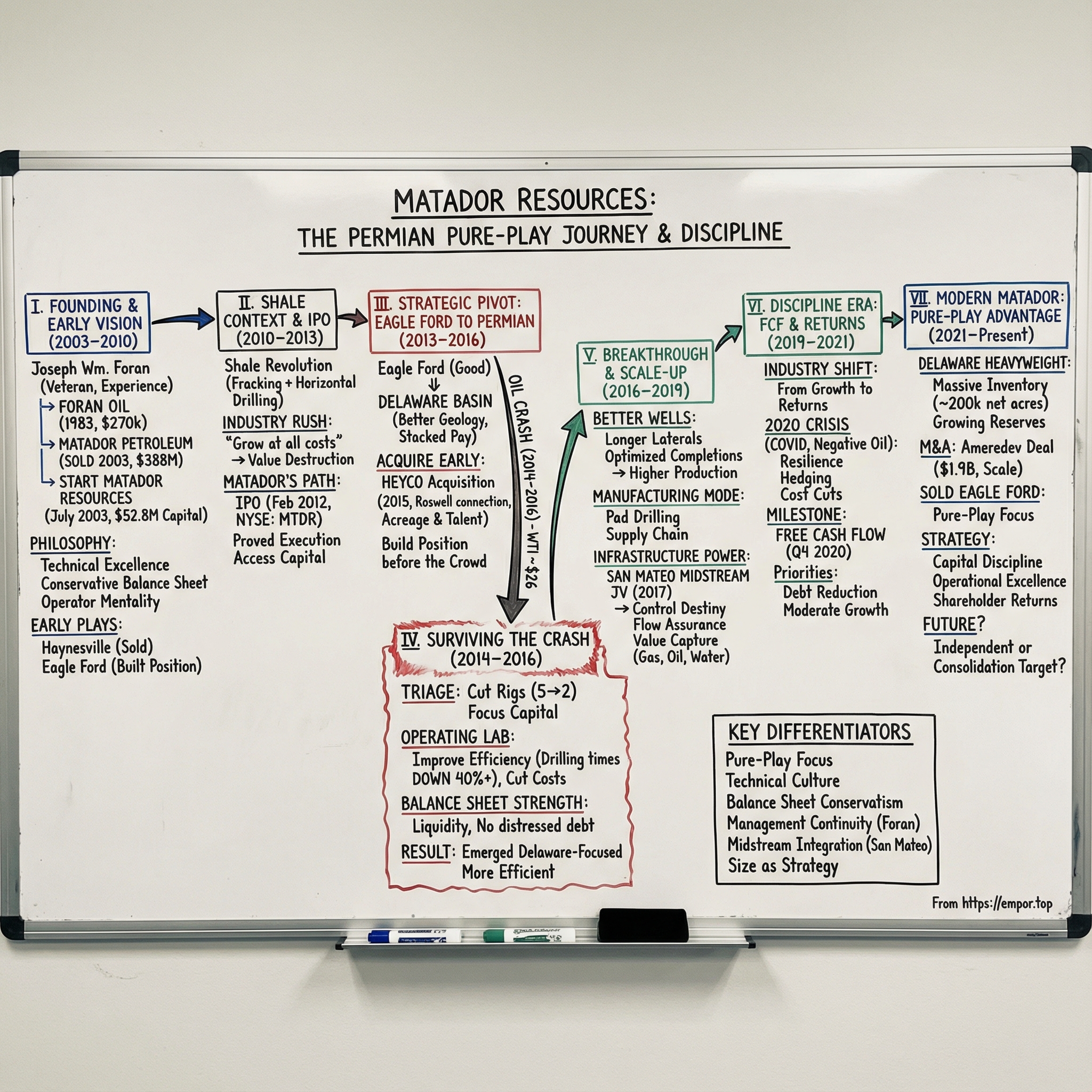

Picture a small Dallas boardroom in 2003. The Iraq War has just begun. Natural gas prices are surging. And a sixty-year-old oil-and-gas veteran named Joseph Wm. Foran is about to make a bet that looks, to most people, borderline irrational: start an exploration and production company from scratch.

This wasn’t a Silicon Valley story of outsiders “disrupting” an industry they barely understood. Foran was the opposite. He’d spent decades in the trenches—as a geologist, an operator, and a dealmaker—surviving enough boom-and-bust cycles to know exactly how the oil patch can destroy value as fast as it creates it. His conviction wasn’t that energy was easy. It was that it was possible to build a company that didn’t have to follow the industry’s usual script.

Matador Resources Company was incorporated that year and headquartered in Dallas, Texas. It set out to acquire, explore, develop, and produce oil and natural gas in the United States. And over time, it would operate through two segments: Exploration and Production, and Midstream.

Here’s the thesis we’ll explore: how did a startup that began with less than $300,000 in founding capital become one of the most efficient operators in America’s hottest oil basin? The answer sits at the intersection of timing, geology, discipline, and relentless focus.

Matador was founded by Joseph Wm. Foran and Scott E. King with an initial $6 million equity investment. Investors added another $46.8 million shortly afterward, bringing total initial capitalization to $52.8 million—real money, but not the kind that guarantees survival in a capital-hungry business.

And the truth is, this story starts even earlier. Foran’s entrepreneurial run began in 1983, when he formed Foran Oil Company with $270,000 raised from friends and family. That grew into Matador Petroleum Corporation, which he founded in 1988. Over the next 15 years, Matador Petroleum delivered a 21% average annual rate of return to shareholders before it was sold in June 2003 for an enterprise value of about $388.5 million.

What follows is the story of what Foran did next: how Matador navigated multiple price crashes, made a strategic pivot that defined its future, and built a disciplined operating model that separates the winners from the also-rans in shale. We’ll hit the inflection points that mattered, the competitive dynamics that shaped the choices, and the frameworks that help explain why some companies create real wealth in this business—and why so many others don’t.

II. The Founding & Early Vision (2003–2010)

The summer of 2003 was a strange time to launch an exploration and production company. The Iraq War had just begun. Crude was climbing back from its post-9/11 slump. Natural gas was flashing the promise—and the danger—of a volatile decade ahead. Most experienced operators were busy squeezing value out of what they already owned, not volunteering to start over.

Joseph Wm. Foran did it anyway.

Foran wasn’t a typical “wildcatter,” and that was the point. He was born in Amarillo, Texas, where his family ran a pipeline construction business. He’d also built a career that blended oilfield instincts with unusual polish: he served as Vice President and General Counsel of J. Cleo Thompson and James Cleo Thompson, Jr., Oil Producers from 1980 to 1983, and earlier worked as briefing attorney for Chief Justice Joe R. Greenhill of the Supreme Court of Texas. He earned a Bachelor of Science in Accounting from the University of Kentucky with highest honors, then a law degree from SMU’s Dedman School of Law, where he was a Hatton W. Sumners Scholar and the Leading Articles Editor of the Southwestern Law Review.

That background mattered. It meant Foran could read a balance sheet like an investor, structure a deal like a lawyer, and still think like an operator who understood how projects actually get built.

His first entrepreneurial leap came in 1983, when he raised $270,000 from friends and family to form Foran Oil Company. Then, in 1988, he reorganized it as Matador Petroleum, rolling up partnerships the way T. Boone Pickens did at Mesa Petroleum. It was an aggressive move—and it immediately got stress-tested. Oil fell from $35 a barrel to $10.

Foran later credited the directors who backed him early, including industry names like Marlan Downey of ARCO and Shell and Jack Sleeper from Pickens’ enterprise. Their presence gave him credibility when credibility was hard to come by. And Foran built a personal rapport with Pickens himself. “Boone and I worked well together and became friends,” Foran said. “Both of us were from Amarillo with paper routes being in common, too. He gave me valuable insights and advice and was more often right than wrong.”

Over the next 15 years, Matador Petroleum produced a 21% average annual rate of return for shareholders—an eye-popping result in a business defined by cycles and bad timing. It wasn’t just a good run. It was evidence of a repeatable philosophy: discipline in what to buy, discipline in what to drill, and discipline in when to sell.

By 2001, Foran was preparing the obvious next step. On September 10, 2001—the day before the terrorist attacks—he received approval to take Matador Petroleum public, and he chartered a plane to New York. Then 9/11 happened, the world froze, and the IPO plan evaporated. The industry shifted. Capital shifted. And Foran, who had been playing a more conventional acquire-and-exploit game, began steering toward what was becoming the next oil-and-gas frontier.

In June 2003, he sold Matador Petroleum to Tom Brown Inc. for $388 million in an all-cash deal. And then, almost immediately, he did something that tells you everything about his mindset: the following Monday, he founded Matador Resources.

Sell the company on Friday. Start the next one on Monday.

This wasn’t a retirement lap. Foran was sixty years old and clearly saw a once-in-a-generation opening in unconventional oil and gas. Matador Resources began with $6 million, plus a proven management and technical team and a board that understood the business. The plan wasn’t to become a financial story. It was to become a drill-bit story—built through operating, not promotional spreadsheets.

Early on, Matador leaned into unconventional plays, initially in the Haynesville. And then the company made a move that, in hindsight, looks like the prototype for how it would operate for years: get in early, monetize strategically, and recycle capital into the next great opportunity. In 2008, Matador sold Haynesville rights on roughly 9,000 net acres to Chesapeake for about $180 million, while retaining a 25% participation interest, a carried working interest, and an overriding royalty interest.

That sale changed the company’s trajectory. Matador redeployed capital into the Eagle Ford early—acquiring more than 30,000 net acres for about $100 million, primarily in 2010 and 2011. The pattern was starting to emerge: build a position before the crowd arrives, sell when the market pays up, and keep moving.

By late 2010, Matador also began shifting toward oil and liquids-rich shale to balance the portfolio. That pivot would prove prescient. Natural gas prices would later collapse, while oil held up far longer.

Matador had been privately held since July 2003, funded by several hundred investors—many of them shareholders from the predecessor company—who were essentially betting on Foran’s ability to do it again. On February 2, 2012, Matador’s common stock began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker MTDR as part of its Initial Public Offering.

The IPO wasn’t positioned as a victory lap. By then, Matador had proved its Eagle Ford acreage, shown real production growth, and demonstrated it could execute. Going public was about accessing the capital markets for the next chapter. From a roughly $643 million market cap at the IPO, Matador would grow to a company valued in the billions.

Underneath the acreage moves and financing events, Foran built something quieter—and more durable: a culture. From day one, Matador emphasized technical excellence over financial engineering, conservative balance sheets built to survive downturns, and an operator mentality that prioritized execution over promotion. Those principles would matter enormously once shale’s boom years arrived—and once the bust inevitably followed.

III. The Shale Revolution Context

To understand why Matador’s story matters, you have to understand the industry backdrop it grew up in—because shale was the kind of opportunity that could make you rich, or tempt you into doing something that got you wiped out.

The “Shale Revolution” was the collision of two technologies—hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling—that turned previously uneconomic rock into a manufacturing-style resource. The commercial spark is usually traced back to George Mitchell’s relentless experimentation in the Barnett Shale, starting in 1981. It took nearly two decades to refine shale fracs that worked consistently and cheaply enough, and then to pair them with horizontal wells in a repeatable way.

By the early 2000s, the pieces were coming together: horizontal drilling, microseismic mapping, and slickwater fracking were being combined into what most people now think of as modern fracking. Many analysts point to 2003 as the moment the shale revolution truly began.

That timing matters, because July 2003 is also when Joe Foran founded Matador Resources. Matador wasn’t late to shale. It was born into it. And in the same era, horizontal drilling was beginning to show up in places like the Delaware Basin in New Mexico.

The basic idea is simple: shale formations are long and thin, so a horizontal well exposes far more rock than a vertical one. Then hydraulic fracturing creates pathways through that rock so oil and gas can flow. Once the technique proved itself—starting with early success in the Barnett in the early 2000s—development accelerated quickly.

The economic impact was huge. The U.S. shale boom created millions of jobs and helped fuel a broader recovery after the financial crisis. It also rewired America’s energy position, turning the U.S. from a major natural gas importer into a leading exporter.

But shale also came with a darker lesson—and it’s the reason discipline becomes the theme of Matador’s story. Once shale started working, money rushed in. From roughly 2010 through 2015, the prevailing strategy across the industry could be summarized in one line: grow at all costs. Drill more wells, post higher production, and let the equity story take care of itself.

Except it didn’t. In aggregate, the shale sector destroyed staggering amounts of shareholder value. Production growth looked like success, but it often came with lousy returns on capital. Companies loaded up on debt to keep drilling, service costs surged as activity ramped, well results didn’t always match early hype, and then commodity prices did what they always do: they cycled. A huge amount of capital went into the ground and never earned an adequate return.

Geology is where the long-term winners separated from the rest, and the Permian Basin had an edge that was hard to match. The greater Permian Basin in Southeast New Mexico and West Texas is a mature oil province with decades of development across multiple petroleum systems. Historically, much of that development targeted conventional reservoirs. But with better formation evaluation, 3-D seismic, horizontal drilling, and hydraulic fracturing, the basin’s unconventional potential became dramatically more accessible.

In the Delaware Basin in particular, operators weren’t just chasing a single layer. They had multiple horizontal targets stacked vertically—especially across the Bone Spring and Wolfcamp—within thousands of feet of hydrocarbon-bearing rock. That “stacked-pay” reality would become central to the Delaware’s economics: hold one acreage position, and you could develop it with multiple benches over time instead of drilling one zone and moving on.

Matador’s Eagle Ford position gave it critical experience and cash flow in the early shale years. But leadership recognized early that the Permian—especially the Delaware Basin—offered better geology and better long-run economics. That insight set up the next defining chapter: a pivot from a great shale play to the one that would become the crown jewel.

IV. The Strategic Pivot: From Eagle Ford to Permian (2013–2016)

By the summer of 2013, the Eagle Ford was the place to be. Production was exploding, rigs were stacked deep, and land prices were catching up to the hype. Matador had done exactly what a smart young shale company was supposed to do: it had quietly assembled more than 30,000 net acres, proved it could execute, and built real momentum.

And then Foran and his team started looking for the next act—before the market forced them to.

While the Eagle Ford got louder and more expensive, Matador kept building a leasehold position in the Delaware Basin of Southeast New Mexico and West Texas. In March and April of 2013, the company acquired about 9,617 gross acres, or 7,446 net acres, in Lea and Eddy Counties, New Mexico for approximately $11.3 million.

This was more than a bolt-on. It was the first deliberate step into what would become Matador’s defining advantage: the Delaware’s stacked-pay geology. The Eagle Ford is a terrific shale play, but it’s largely a single target. The Delaware is different. It offered multiple benches in the Wolfcamp—A, B, C, and D—plus the First, Second, and Third Bone Spring sands. In plain English, one surface footprint could hold several distinct drilling horizons. If the geology cooperated, the same acreage could support many more wells over time.

Foran made the strategy explicit at the time. “We are very excited by these recent additions to our leasehold position in West Texas,” he said, “and look forward to testing this acreage for the Wolfcamp, Bone Spring and other prospective oil plays beginning later this month.”

The company moved quickly, but it didn’t move blindly. In July 2014, Matador announced results from two Delaware Basin wells that helped turn a promising idea into something tangible. In Loving County, Texas, the Norton Schaub #1H well, a Wolfcamp “A” test, flowed 1,026 BOE per day—about 69% oil. In Lea County, New Mexico, the Pickard State well flowed 592 BOE per day, about 90% oil.

Early data points like these mattered. They didn’t just show that the Delaware could work; they showed it could work well on Matador’s acreage.

Then came the deal that put real scale behind the pivot. In January 2015, Matador announced a definitive agreement to acquire Harvey E. Yates Company, a subsidiary of HEYCO Energy Group, including producing properties and undeveloped acreage in Lea and Eddy Counties, New Mexico. HEYCO was headquartered in Roswell and owned by members of the Yates family, who had been active in the Delaware Basin since the earliest days of production there in the 1920s.

Matador structured the acquisition in a way that matched its temperament. It paid approximately $37.4 million in cash, including assumed debt obligations, issued 3,140,960 shares of Matador common stock, and issued 150,000 shares of a new series of Matador convertible preferred stock.

What did it get? Approximately 58,600 gross acres, or 18,200 net acres, positioned right between Matador’s existing Ranger and Rustler Breaks areas—exactly the kind of contiguous, build-a-block geography that makes drilling and development more efficient.

With the HEYCO assets, Matador increased its Permian position to roughly 151,300 gross acres, or 84,300 net acres, expanding its operational footprint across the northern Delaware Basin. BMO Capital Markets expected Matador to hold the largest Delaware Basin acreage position among small and mid-cap publicly traded energy companies.

Foran’s commentary also revealed what kind of acquisition this was. “We are very excited to combine the quality assets and experienced people of HEYCO with those of Matador,” he said. “The Harvey E. Yates Company, run by my long-time friend George Yates, is among the best-known, most respected and experienced operators in the state of New Mexico. We will be pleased to welcome George to the Matador Resources Company Board of Directors and to work with him.”

This wasn’t a roll-up driven by financial optics. It was a classic oil patch transaction: buy from people who know the rock, bring the talent with the assets, and stitch together acreage in a way that makes the whole worth more than the parts.

And just as importantly, Matador stayed valuation-disciplined. The location of the assets, the multi-pay potential, favorable net revenue interests, and the held-by-production status of essentially all the acreage were key reasons the opportunity made sense.

The contrast with the broader shale world was stark. During the 2013–2014 frenzy, plenty of companies paid peak-cycle prices for “core” land. Matador’s approach was more surgical: keep building positions through relationships and timing, and focus on acreage before it became a bidding war.

By early 2015, the pivot was real. Matador was no longer an Eagle Ford company with a Permian side project. It was becoming a Delaware Basin operator, with the Eagle Ford as support.

And the timing was about to get tested—because oil prices were heading for a cliff.

V. Surviving the Oil Crash (2014–2016)

In June 2014, West Texas Intermediate traded above $107 a barrel. By February 2016, it had fallen to $26.

It was one of the sharpest oil collapses in modern history—triggered by Saudi Arabia choosing to protect market share instead of price, a surge of U.S. shale barrels hitting the market, and softer global demand. And for shale, it was a wipeout. More than 200 E&P companies filed for bankruptcy between 2015 and 2017. Billions of equity value disappeared. The companies that had borrowed heavily to fund “growth” suddenly couldn’t service their balance sheets when the commodity they sold got cut in half.

Matador didn’t get a free pass. But it did something many peers couldn’t: it stayed standing long enough to get better.

The first move was triage. On a May 7, 2015 earnings call, management discussed a $50.2 million loss in the first quarter of 2015, versus a $16.4 million profit a year earlier. Low prices hit earnings hard, and Matador temporarily suspended Eagle Ford operations.

Then came the part that separated survivors from casualties. Matador didn’t just cut activity. It treated the downturn like an operating lab—shrink the program, focus the capital, and squeeze every inefficiency out of the system.

The company reduced its drilling program from five rigs to two rigs in the first quarter of 2015, then returned to three rigs in the third quarter and kept that pace through the rest of the year. Even in that environment, Matador delivered record production while driving down costs. It said it was still achieving 30% to 50% rates of return on Eagle Ford drilling, and it reduced operating costs by 30% to 40% through vendor adjustments, fewer days on wells, and improvements to its gas lift system.

The best evidence shows up in the drilling and completion details—the unglamorous, repeatable work where shale fortunes are actually made.

In the Second Bone Spring, Matador cut drilling time from 21.8 days on its first 2015 well to an average of 12.6 days in 2016, a 42% reduction. In the Wolfcamp A-XY, average drilling time through the first half of 2016 dropped to 17.7 days from spud to total depth, versus 24.5 days in late 2014 and 20.1 days in 2015.

And the gains weren’t theoretical. The fastest-drilled Wolfcamp B well, the B. Banker #221H, reached total depth in 17.5 days on a 15,151-foot well—58% faster than the average in late 2014. In the Second Bone Spring, eliminating a casing string saved about $650,000 per well.

All of that only matters if you can fund it. Matador could.

Management said that, thanks to transactions and continued success in the Delaware Basin during 2015, the company entered 2016 with what it described as one of the strongest balance sheets and financial positions in its history. It began 2016 with about $375 million of undrawn borrowing capacity on its revolving credit facility—liquidity that gave it room to execute its capital program while others were simply trying to survive the next redetermination.

That financial flexibility supported the key strategic choice of the crash: keep drilling, but concentrate on the best rock.

By the fourth quarter of 2016, the Delaware Basin represented 69% of Matador’s total production. Pausing Eagle Ford activity while leaning into the Delaware proved timely: Delaware oil production nearly tripled year over year, from about 222,000 barrels in the first quarter of 2015 to about 653,000 barrels in the first quarter of 2016.

And even with oil prices near decade lows, Matador grew oil volumes. It produced a record 5.1 million barrels in 2016—up 13% from 2015, and up 54% from 2014.

Joe Foran captured the posture in his letter to shareholders: “2016 will likely be an even more challenging operating and commodity price environment than we have faced in many years. We must and we will focus in 2016 on execution and those things we can control in our operations, while remaining flexible and open to the special opportunities that may come our way in these times.”

That’s the downturn playbook in one paragraph. Busts don’t just punish the overleveraged—they reshuffle the leaderboard. Matador entered the crash as a mid-sized operator with Permian exposure. It came out the other side more Delaware-focused, more efficient, and positioned to scale when the cycle turned.

VI. The Permian Breakthrough & Scale-Up (2016–2019)

By mid-2016, oil had clawed its way back above $40. Survivors across the shale patch started to lean forward again. But Matador wasn’t simply turning the rigs back on. It was coming out of the crash with a better operating system than it had going in.

By the end of 2019, Matador was posting all-time highs in oil, natural gas, and total proved reserves. Over the prior two years, estimated total proved reserves jumped by about 100 million BOE, reaching 152.8 million BOE at December 31, 2017 and rising 65% through December 31, 2019. In a business where “growth” often meant burning capital, this was growth backed by drilling results and de-risked inventory.

That step-change came from three things working together: better well economics, tighter execution in the field, and a deliberate push to control its own infrastructure destiny.

The wells were the proof. Matador drilled longer laterals and pushed completion designs that did more with the same rock. Two standout wells kept outperforming expectations, each producing more than 200,000 barrels of oil in the first 150 days. Even more important than the early flash: their production declines were shallower than Matador’s nearby one-mile laterals, and early production more than doubled what those older designs had delivered over a similar timeframe. In shale, that combination—higher initial rates and slower falloff—is how you turn a “good” well into a great asset.

By late 2016, the Delaware Basin wasn’t just the future. It was the business. Delaware Basin production in the fourth quarter of 2016 averaged about 20,700 BOE per day, up 138% year over year. And that quarter, the Delaware accounted for 69% of Matador’s total production. The pivot that began as “the next act” had become the main stage.

As the Delaware position matured, Matador started running it less like a set of isolated experiments and more like a manufacturing line. Pad drilling let crews drill multiple wells from one location, cutting move times and shrinking surface disruption. The company optimized its supply chain and applied data to refine which completion recipes worked best in which benches. The cumulative effect was simple: more consistency, less waste, and a faster learning curve.

Then came the infrastructure piece—because in the Permian, great wells don’t matter if you can’t move the molecules.

Matador announced a second strategic midstream expansion, commonly referred to as San Mateo II, with a subsidiary of Five Point Energy LLC. The goal was to expand San Mateo’s natural gas gathering and processing, saltwater gathering and disposal, and oil gathering operations in the Delaware Basin. As part of that expansion, San Mateo planned to build an additional cryogenic natural gas processing plant near the existing Black River cryogenic plant outside Carlsbad, New Mexico.

The deal was designed to create value on multiple fronts: dedicating what Matador expected to be highly productive acreage in the Stateline asset area and the Greater Stebbins Area; capturing natural operational synergies between the expanded plant and connected pipeline systems; and deepening relationships with third-party customers in the area. As Matt Morrow, Chief Operating Officer of Five Point, put it, “We are delighted to continue our very successful partnership with the Matador team, who we believe to be one of the pre-eminent operators in North America.”

Operational discipline also showed up in places that didn’t get celebrated on investor decks a decade earlier: emissions. Since 2017, Matador reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 6%, and cut both its emissions intensity rate and methane intensity rate by 33%. That wasn’t just a sustainability headline. In practical terms, capturing methane instead of losing it meant fewer leaks, less flaring, and more product to sell—another signal of an operation getting tighter.

Put it all together and the market started to take notice. Matador wasn’t just surviving the post-crash world; it was executing its way into a different tier. From a small-cap operator fighting for oxygen, it was becoming a mid-cap Permian story that institutions could underwrite—and one that, increasingly, could set its own pace.

VII. The Midstream Master Stroke: San Mateo Midstream

In the Permian from 2016 to 2019, one complaint came up over and over: infrastructure couldn’t keep up. Production was growing faster than pipelines and processing, so operators got squeezed—forced to flare gas, truck oil farther than they wanted, and pay up for whatever takeaway they could secure.

Matador’s answer wasn’t to complain louder. It was to build.

That’s the origin story of San Mateo Midstream: a very Matador kind of move, rooted in a simple question. If third parties were going to charge premium fees for gas processing, oil gathering, and water disposal, why not build the system that fits your acreage, your pace, and your development plan?

San Mateo Midstream, LLC is a joint venture between Matador Resources Co. and Five Point Energy LLC. It provides an integrated set of services across the three big streams that come out of shale development: saltwater gathering and disposal; natural gas gathering, compression, treating, and processing; and oil gathering, transportation, and blending.

The foundation asset was the Black River Processing Plant, placed into service in August 2016 with a designed inlet capacity of 60 million cubic feet of natural gas per day. Then, in February 2017, San Mateo I was formally formed as a joint venture owned 51% by Matador and 49% by Five Point.

That 51/49 split told you what Matador was really after. This wasn’t just about getting a plant built. It was about control. Matador kept operational control through majority ownership, brought in Five Point’s capital and midstream expertise, and created a structure that could capture the value of infrastructure without selling off the strategic steering wheel.

Even the funding mechanics reflected that mindset. Matador would receive a capital carry, paying only $25 million of the first $150 million in capital expenditures tied to the expansion.

Then the system scaled—fast. San Mateo grew from a startup generating roughly $26 million of net income and about $31 million of Adjusted EBITDA in 2017 to expectations of more than $170 million of net income and over $250 million of Adjusted EBITDA in 2024. Over that same arc, gas processing capacity expanded from 60 million cubic feet per day in 2016 to 720 MMcf/d, putting it among the top three midstream gas processing systems by capacity in New Mexico.

Just as important as size was the offering. San Mateo’s ability to handle crude oil, natural gas, and water made it one of the few full-service midstream providers in the northern Delaware Basin. That matters in shale because bottlenecks rarely show up in only one place. If you solve gas but can’t move oil, you’re still stuck. If you can’t handle water, you can’t complete wells. Integration is the point.

The capital allocation lesson is straightforward: Matador saw a constraint that could have limited its best acreage, built assets designed specifically to remove that constraint, partnered with sophisticated capital to accelerate the buildout, held onto control and a majority of the economics, and ended up with a cash-flowing platform that could also serve third-party customers.

In 2024, Matador extended that playbook with the Pronto transaction. The company executed a definitive agreement to contribute Pronto Midstream, LLC—Matador’s wholly-owned midstream subsidiary—into San Mateo Midstream, LLC, at an implied valuation of approximately $600 million. At closing, Matador received an up-front cash payment of approximately $220 million for that contribution.

The result was more of what Matador has always been building toward: control over its own destiny in the northern Delaware. After the upcoming Marlan Processing Plant expansion, San Mateo is expected to be one of the leading natural gas processors in New Mexico with over 700 million cubic feet of designed inlet natural gas processing capacity. The transaction also provided Matador, San Mateo, and their customers with a long-term sour gas solution in northern Lea County, New Mexico.

VIII. The Discipline Era: Free Cash Flow & Returns (2019–2021)

By 2019, shale had hit its reckoning. After a decade of “growth at any cost,” investors stopped rewarding volume and started demanding something far less glamorous and far more real: cash. The new message to every management team was the same—stop chasing production charts and start proving returns.

Then 2020 arrived, and it wasn’t a normal downturn. COVID-19 slammed demand, storage filled up, and in April oil prices briefly went negative—a once-unthinkable moment that captured just how broken the market had become.

For Matador, it was the second major stress test in a few years. Joseph Wm. Foran, the company’s Chairman and CEO, put the priority plainly: “As we navigate this abrupt change in oil prices, our first priority is to protect our balance sheet and to position ourselves for the long run.” Management moved quickly, cutting the operated drilling program from six rigs to three by the end of the second quarter of 2020.

And the belt-tightening wasn’t limited to the field. Leadership made it personal. “Towards that end, I have voluntarily agreed to reduce my base salary by 25%, the Board members have agreed to reduce their compensation by 25% and the executive officers and Vice Presidents have agreed to reduce their base salaries by 20% and 10%.”

The other quiet stabilizer was hedging. Matador said it restructured its oil hedge positions at the beginning of the second quarter of 2020 to protect revenues and cash flows through extreme volatility, and expected to report a realized net gain on derivatives of approximately $44.1 million for the quarter.

What’s striking is what happened next: Matador didn’t just make it through 2020—it exited the year with momentum. Management called the fourth quarter “an excellent and significant quarter,” and laid out four clear priorities: generate free cash flow, use part of it to start paying down debt, grow production sequentially by at least 8% to 10%, and ramp up operations to take advantage of San Mateo’s expanded infrastructure. Matador said it met or exceeded those goals, setting record quarterly highs for oil, natural gas, and total production, while also posting record quarterly lows for drilling and completion costs per lateral foot and for per-unit lease operating and general and administrative expenses.

The free cash flow milestone mattered most, because it signaled the strategic shift was real. Matador said it achieved free cash flow for the first time in the fourth quarter of 2020, with $157.6 million of net cash provided by operating activities and adjusted free cash flow of $60.7 million. With that cash in hand, it repaid $35 million of borrowings under its reserves-based credit facility during the quarter.

Even reserves moved the right direction, despite the year’s brutal commodity backdrop. Matador’s proved reserves increased 7% year over year to 270.3 million BOE—an all-time high—despite the lower oil and natural gas prices the company was required to use when estimating proved reserves.

IX. Modern Matador: The Pure-Play Advantage (2021–Present)

By 2021, the energy industry was entering a new era. Oil prices had recovered, demand was rebounding, and the companies that survived the twin crises of 2015–2016 and 2020 were finally positioned for the harvest.

Matador was one of them. By 2024, it looked like a different company than the one that had fought for air during the crash years: larger, more efficient, and consistently generating meaningful free cash flow. That evolution showed up most clearly in the inventory it had built. Matador’s total proved oil and natural gas reserves increased 33% year over year, from 460.1 million BOE at December 31, 2023 to 611.5 million BOE at December 31, 2024—an all-time high. Those reserves were overwhelmingly Delaware Basin reserves, and the mix leaned heavily toward oil.

Then Matador accelerated the strategy with another swing at scale. The company entered into a definitive agreement to acquire a subsidiary of Ameredev II Parent, LLC, including producing properties and undeveloped acreage in Lea County, New Mexico and Loving and Winkler Counties, Texas. The deal also included an approximately 19% stake in Piñon Midstream, LLC, with midstream assets in southern Lea County. The consideration for the Ameredev Acquisition was set as an all-cash payment of $1.905 billion.

The logic was consistent with Matador’s playbook: concentrate in the Delaware, deepen the core, and make sure the system around the wells keeps up. On a pro forma basis after closing, Matador expected to hold more than 190,000 net acres in the Delaware Basin, roughly 2,000 net locations, production above 180,000 BOE per day, proved reserves of about 580 million BOE, and an enterprise value above $10 billion.

What’s notable is that Matador tried to keep its financial posture steady even while writing a very large check. To help finance the all-cash transaction, Matador received firm commitments from PNC Bank to increase the elected commitment under its credit facility by 50%, from $1.5 billion to $2.25 billion, and to provide a $250 million Term Loan A. Management also said the acquisition should not significantly change the company’s long-term leverage profile, expecting its pro forma leverage ratio to move back below 1.0x by mid-2025 based on current commodity prices.

Operationally, the company kept pushing on two fronts at once: grow, but keep getting cheaper. Matador’s leaders raised full-year production guidance by 6% to about 170,000 BOE per day, and they aimed to push past 200,000 BOE per day in 2025. In the three months ended September 30, Matador averaged nearly 171,500 BOE per day, including a little more than 100,000 barrels per day of oil—up 7% from the second quarter.

And they weren’t buying that growth with higher costs. Executives said drilling and completion costs fell to about $930 per lateral foot from an earlier forecast of about $1,010. Chief operating officer Chris Calvert said the addition of some trimulfrac work and remote operations could push that number lower again next year.

Finally, Matador closed the loop on a strategy that had been years in the making: it recently sold its Eagle Ford assets. The Eagle Ford had been a productive chapter and an important training ground—a steppingstone that helped Matador gain experience and build the position that ultimately mattered most. Now the company’s story was cleaner and more concentrated: a primary focus on developing what it sees as high-quality acreage in the northern Delaware Basin, where it owns approximately 200,000 net acres.

X. The Competitive Landscape & What Makes Matador Different

In the Delaware Basin today, Matador goes to work surrounded by both giants and specialists. EOG Resources—the early shale standard-bearer—brings elite technical horsepower. Diamondback Energy has rolled up the Permian into a consolidation machine. Pioneer Natural Resources, once a flagship pure-play peer, was acquired by ExxonMobil in 2024—one more data point in a consolidation wave that keeps pulling the center of gravity toward the biggest balance sheets.

Against that backdrop, Matador has been carving out a very specific lane. It “continues to build scale as one of the two principal public companies with the lion’s share of their operations in the Delaware basin,” said Andrew Dittmar, principal analyst at Enverus Intelligence Research.

So what, exactly, makes Matador different?

Pure-Play Focus: Unlike diversified majors, Matador keeps its attention on one basin. That focus simplifies decision-making and concentrates talent, capital, and learning in the place that matters most to the company’s returns.

Technical Culture: From the beginning, Matador leaned operator-first. It built an organization of technical and administrative professionals aimed at execution and financial discipline, not just telling a growth story. You can see it in the steady push toward lower drilling costs and better well results.

Balance Sheet Conservatism: Matador’s defining habit through multiple cycles has been staying financially flexible. That discipline helped it survive the crashes—and still have the capacity to act when opportunities showed up and competitors were forced to retreat.

Management Continuity: Foran founded Matador Resources Company in July 2003 and, since its founding, has served as Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer. In an industry where strategies can whipsaw with leadership changes, that continuity compounds into institutional knowledge and a clearer sense of what the company will—and won’t—do.

Midstream Integration: San Mateo’s ability to handle crude oil, natural gas, and water makes it a meaningful midstream operator in the northern Delaware Basin. That matters because it’s not just about fees—it’s about flow assurance. When bottlenecks hit, integrated infrastructure can be the difference between turning wells on and waiting.

Size as Strategy: Matador sits in an attractive middle. It’s large enough to benefit from operational scale and capital markets access, but still small enough to stay nimble and pursue bolt-on deals without turning every acquisition into a multi-year integration project. In a consolidating basin, that’s a real strategic position.

None of this eliminates the risks of being mid-cap while the industry keeps consolidating. Larger operators can outbid others for assets—or decide to buy them outright. But Matador’s history of disciplined capital allocation and operational execution has earned it a valuation premium, and that premium raises the price tag for anyone who wants to take it out.

XI. Porter's Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: HIGH BARRIERS

On paper, shale looks like a business you can “scale into.” In reality, it’s one of the hardest industries in America to break into from scratch. You need enormous upfront capital just to assemble a meaningful position, and that’s before you drill a single well. You also need hard-won technical know-how: interpreting complex geology, drilling long horizontals consistently, and iterating completion designs until the economics work. And in the core Delaware Basin, the best acreage is already spoken for. A new entrant either settles for lower-quality rock or pays a price that makes returns difficult. These are the kinds of barriers that favor incumbents like Matador.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: MODERATE

In oil and gas, your “suppliers” are the oilfield service firms: drilling contractors, pressure pumpers, equipment providers. Their power swings with the cycle. When activity is hot, crews and equipment get tight and prices rise fast. When the cycle turns, service companies compete hard and operators regain leverage. Matador’s scale and long-standing relationships help, but it still operates in a market where it can’t fully control what it pays when the basin heats up.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: LOW

Matador sells into deep, liquid commodity markets. It doesn’t get to brand its barrels or negotiate a premium. Oil and gas trade at prevailing prices, and buyers can source supply from countless alternatives. That keeps buyer power low—but it also means Matador lives with the core reality of the business: commodity price volatility is always in the room.

Threat of Substitutes: MODERATE-HIGH (LONG-TERM)

The long-term substitute story is real: electric vehicles, renewable power, and efficiency all work against oil and gas over time. The catch is the timeline. Most forecasts still show meaningful oil and gas demand well into the 2030s, and natural gas keeps a strong role in power generation and broader energy security. Matador’s liquids-rich Delaware production helps here too, since oil and NGLs don’t track the exact same demand dynamics as dry gas.

Industry Rivalry: HIGH

The Delaware Basin is a knife fight, filled with well-capitalized operators all chasing the same outcome: the best returns per well, on the best rock, with the lowest cost structure. There’s no product differentiation—oil is oil—so the battle is fought in execution: drilling speed, completion design, infrastructure access, and balance sheet stamina. That competitive pressure forces constant improvement, rewarding operators like Matador that can consistently get more out of each dollar and punishing the ones that can’t.

XII. Hamilton's 7 Powers Framework Analysis

Hamilton Helmer’s “7 Powers” framework is a useful way to separate companies with a real, durable edge from companies that are simply riding a good cycle. For Matador, a few of the powers show up clearly—and a few simply don’t.

Scale Economies: YES

Matador gets operating leverage from concentrating in the Delaware Basin. As volumes grow, the fixed pieces of the business—G&A, technical talent, and the overhead required to run a safe, repeatable drilling program—get spread across more barrels. San Mateo amplifies that leverage: when you own more of the gathering, processing, and water system around your wells, you don’t just reduce friction. You capture more of the value chain that would otherwise go to someone else.

Network Effects: NO

This isn’t a network business. Producing an extra barrel doesn’t make the next barrel easier to sell or inherently more valuable. Scale helps with costs and execution—but not through network effects.

Counter-Positioning: PARTIAL

Matador’s pure-play focus and operator-led culture do create a kind of counter-positioning versus diversified majors, who can’t concentrate talent and attention in quite the same way, and versus more financially engineered players, who often lack deep technical capabilities. But it’s partial, not total. Plenty of Delaware Basin operators talk the same language, which limits how unique this advantage can be.

Switching Costs: NO

Matador sells into commodity markets. Buyers can switch instantly because oil and gas are interchangeable at the point of sale.

Branding: NO

There’s no consumer brand premium here. Matador’s reputation can matter in partnerships and acquisitions, but the molecules aren’t branded.

Cornered Resource: YES

This is one of Matador’s core powers. The company owns roughly 200,000 net acres in the Delaware Basin—high-quality Permian rock with long runway potential. Acreage like that is scarce, and it’s not something competitors can replicate on demand. New entrants can’t assemble an equivalent position without paying prices that usually destroy the economics.

Process Power: YES

Matador’s edge also shows up in the unsexy part of the business: doing the same hard thing, repeatedly, with fewer mistakes. Its Delaware drilling and completions program kept improving, including at Rustler Breaks. Through the first half of 2016, Matador reduced average drilling time in the Wolfcamp A-XY to 17.7 days from spud to total depth, down from 24.5 days in late 2014. That’s what process power looks like in shale: accumulated know-how, tighter workflows, and an organization that keeps learning.

Primary Powers Summary: Matador’s durable advantages come from Cornered Resource (high-quality Delaware Basin acreage), Process Power (operational excellence and continuous improvement), and Scale Economies (operating leverage reinforced by midstream integration). Together, they help explain why Matador compounded value while so many shale peers burned capital.

XIII. The Bull vs. Bear Debate

Bull Case:

Best-in-Class Permian Operator: Matador has increasingly looked like a top-tier Delaware Basin operator where it counts: drilling costs, well productivity, and finding and development costs. In shale, those aren’t vanity metrics. They’re the difference between drilling wells that create value and drilling wells that just create volume.

Disciplined Management with Proven Track Record: Matador’s leadership has already proven it can steer through cycles without blowing up the balance sheet. That matters because the shale graveyard is full of companies that were “great operators” right up until prices fell. Foran’s earlier 21% average annual returns at Matador Petroleum weren’t a one-off; they reflected a capital allocation mindset that has continued to shape Matador Resources.

Massive Inventory Depth: Matador has built a long runway in the Delaware Basin, with near industry-low finding and drilling costs and roughly a decade-plus of inventory. With more than 2,000 drilling locations, the company can keep developing its core position for years without needing to overpay for the next acreage deal just to stay in the game.

Free Cash Flow Machine: The model has shifted from “drill to grow” to “drill to generate cash.” Matador has been generating meaningful free cash flow that can fund moderate production growth while also supporting debt reduction, dividends, and share repurchases.

Consolidation Target: The Permian has been consolidating quickly, and high-quality, scaled pure-plays have been drawing premium interest. Matador’s Delaware position puts it in that conversation, especially in a world where the majors want inventory depth they can trust.

Energy Security Tailwinds: U.S. oil and gas production has become strategically important again, not just economically but geopolitically. A supportive posture toward domestic production could benefit efficient Delaware Basin operators with large, developable inventory.

Bear Case:

Commodity Price Exposure: No matter how good the execution gets, Matador still sells commodities with no pricing power. If oil prices fall and stay low, margins compress. Operational excellence can soften the blow, but it can’t prevent it.

Peak Oil Demand Concerns: Electric vehicles, efficiency gains, and climate policy all point to long-term pressure on oil demand. The timeline is uncertain, but if the transition accelerates, the risk is that a portion of long-lived reserves becomes less valuable than the market once assumed.

Consolidation Risk: Being a potential acquisition target cuts both ways. A takeout could deliver a premium, but it could also end the pure-play identity and the management continuity that helped create Matador’s edge in the first place.

Execution Risk: Shale is still a technical business. Geology can surprise you. Service costs can spike. Operational missteps happen. Results can come in below expectations, and cost targets can prove too optimistic.

Size Disadvantage: Mid-caps don’t have the same capital markets access, diversification, or shock absorbers as the mega-majors. In a stressed market, that can limit flexibility at exactly the wrong time.

Regulatory/Political Risk: With meaningful operations in New Mexico, Matador faces permitting and environmental regulatory risk. Policy shifts can affect the pace of development and the economics around it.

What to Monitor:

Production Growth vs. Capital Discipline Balance: Watch whether Matador holds the line on its targeted 5% to 10% annual growth while still generating free cash flow, or whether it drifts toward either extreme—overgrowth or underinvestment.

Free Cash Flow Yield and Capital Allocation: The story now lives and dies by what management does with cash: pay down debt, raise the dividend, buy back stock, or pursue acquisitions. The mix—and the discipline behind it—will tell you a lot.

Well Productivity Trends: Keep an eye on initial rates and decline curves. If they start slipping, it can be an early signal of inventory degradation. If they keep improving, it suggests the technical machine is still getting better.

Balance Sheet Metrics: Leverage matters most when the cycle turns. A debt-to-EBITDA ratio below 1.0x signals room to maneuver; anything creeping toward 2.0x is a sign to pay closer attention.

XIV. Playbook: Lessons for Operators & Investors

Matador’s climb from a $270,000 friends-and-family start to a multi-billion-dollar public company reads like a case study in what actually works in shale—especially when the cycle turns against you.

Focus Wins: Matador’s pure-play mindset concentrated people, capital, and learning in one place. In a business where geology and execution decide everything, depth tends to beat breadth.

Timing Matters: The early move into the Eagle Ford, the early recognition that the Delaware Basin had better long-run economics, and the eventual exit from the Eagle Ford all point to the same skill: reallocating capital before the rest of the market is forced to.

Culture Eats Strategy: “Operator mentality” can sound like a slogan until you see it show up in the details—shorter drilling times, better cost structures, and fast, decisive action in downturns. Culture isn’t what you say; it’s what your teams do when prices collapse.

Survive to Thrive: Matador’s conservative balance sheet gave it something invaluable in 2015–2016 and again in 2020: time. When competitors were trapped by leverage, Matador could keep optimizing, keep drilling selectively, and stay ready for opportunities that only appear in distress.

Build Infrastructure Power: San Mateo Midstream is a reminder that in the Permian, controlling infrastructure isn’t a side quest. It’s a competitive advantage. Flow assurance, lower friction, and value capture can matter as much as the next incremental improvement in a completion design.

Discipline Over Growth: Matador didn’t win by chasing the biggest production growth chart. It won by staying financially flexible and letting returns—not just volumes—be the scoreboard. In shale, the “grow at all costs” era created plenty of barrels and destroyed plenty of capital.

Know Your Geology: The Delaware Basin’s stacked-pay reality is the kind of advantage you only fully monetize if you understand it deeply—where to buy, where to drill, which benches to prioritize, and how to evolve designs as the data comes in.

Management Continuity: Joe Foran’s long tenure—two decades at Matador Resources, plus the prior run at Matador Petroleum—made it easier to think in cycles instead of quarters. In a boom-bust industry, that kind of continuity is a strategic asset.

The Three KPIs That Matter Most:

For anyone tracking Matador from here, three metrics do a better job than headline production growth of telling you whether the machine is getting stronger:

-

Drilling and Completion Costs per Lateral Foot: This is the clearest window into execution. Matador has targeted sub-$900 per foot. Whether it can hold that line—or push it lower—tells you if process improvements are sticking.

-

Free Cash Flow Yield: This is the “are we actually getting paid?” metric. A free cash flow yield in the double digits typically signals an attractive valuation and real cash generation; a much lower yield can be a sign the business is becoming more capital-intensive or the market is pricing in higher expectations.

-

Proved Developed Finding and Development Costs (F&D): This shows how efficiently Matador turns capital into reserves. Low F&D costs, including the sub-$10 per BOE range Matador has pointed to as a marker of strong performance, reinforce that the acreage is high quality and the development program is working.

XV. Epilogue: Where Does Matador Go From Here?

As 2025 unfolds, Matador faces a familiar question—one that’s defining the entire Permian right now: stay independent, or become part of the next consolidation headline?

ExxonMobil swallowing Pioneer, Diamondback merging with Endeavor, and Occidental buying CrownRock have all reshaped the Delaware Basin map. Scale has been getting priced like a feature, not a luxury. And in that new landscape, Matador sits in a rare seat: one of the few operators left that’s both meaningfully scaled and still essentially a Delaware pure-play.

That doesn’t mean the company is done shopping. Coming off a roughly $1.8 billion Delaware Basin acquisition, Matador has signaled it still has an appetite for more M&A—especially bolt-on deals that add undeveloped inventory and help high-grade the portfolio. The playbook remains consistent: tighten the footprint, deepen the runway, and keep the asset base concentrated where the wells work best.

But the next decade won’t just be a basin story. It will be an energy transition story—full of contradictions. Hydrocarbon demand has held up better than many predicted, yet capital for new supply has gotten harder to justify amid policy, regulation, and investor pressure. That tension can create a strange outcome: tighter supply that supports commodity prices, even as it limits how aggressively operators can grow.

The upside is that technology still offers room to run. AI and machine learning are starting to show real promise in drilling optimization, completion design, and production forecasting—the kinds of tools that can compound Matador’s process-power advantage if implemented well. And longer-term, carbon capture and enhanced oil recovery sit on the list of possible future revenue streams, even if they’re not yet central to the story.

Operationally, Matador has been leaning forward. It began 2024 running seven drilling rigs in the Delaware Basin, added an eighth in late January 2024, and a ninth by mid-2024. With nine rigs running into 2025 and production targeting over 200,000 BOE/d, Matador has positioned itself less like a scrappy mid-cap and more like a Delaware Basin heavyweight.

Which brings us to the bigger question behind all of this: what does responsible energy development actually look like? Matador’s model—technical rigor, a push toward environmental improvements, balance sheet discipline, and a clear commitment to shareholder returns—is one version of an answer. Whether that version holds up, and creates durable value through the next phase of the energy transition, is the central uncertainty long-term investors can’t ignore.

Still, the arc so far is hard to argue with. From $270,000 raised from friends and family in 1983 to a multi-billion-dollar enterprise today, Joe Foran has shown that in a brutally competitive commodity business, patient capital allocation, technical excellence, and cycle-surviving discipline can be more powerful than hype. The next decade will reveal whether those principles are just timeless—or simply perfectly matched to the last four.

XVI. Further Reading & Resources

Top 10 Resources for Deeper Understanding:

-

Matador Resources investor presentations and annual reports (2012–2024) — The closest thing to a primary-source narrative: how management explained the strategy, what they tracked, and how the operating model evolved over time.

-

The New Map by Daniel Yergin — Big-picture context on modern energy geopolitics and why shale reshaped global power dynamics, not just U.S. supply.

-

The Boom by Russell Gold — A clear, ground-level history of how shale actually happened, told through the people, the experiments, and the hard lessons.

-

Matador’s SEC filings (10-Ks, proxy statements) — The unfiltered details: risks, capital structure, governance, executive incentives, and the footnotes that explain what the glossy decks summarize.

-

Energy research from Raymond James, Tudor Pickering Holt, and Goldman Sachs — Helpful for understanding how institutions benchmark Permian operators, think about cycle risk, and compare development economics across peers.

-

Permian Basin geology studies from the University of Texas Bureau of Economic Geology — If you want to understand why the Delaware is different, start here: stacked pay, bench-level nuance, and the geology that makes the inventory real.

-

The Prize by Daniel Yergin — The long arc of the oil business: the history, the power politics, and the recurring patterns that make today’s boom-bust dynamics feel eerily familiar.

-

Midstream infrastructure case studies and San Mateo transaction documents — A deeper look at the “build it to unlock the basin” strategy, and how control of pipes, processing, and water can change an operator’s outcomes.

-

Interviews with Joseph Wm. Foran (earnings calls, industry conferences) — The management philosophy in its own words, including what Matador emphasizes when the market is good and when it isn’t.

-

Shale industry post-mortems, including Harvard Business School cases on value destruction vs. value creation — Useful frameworks for the central question shale keeps asking: why did some teams compound returns while so many others turned growth into losses?

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music