Mettler-Toledo: The Precision Scale of Global Science and Industry

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

There’s an object sitting on virtually every pharmaceutical lab bench, every food production line, and every quality-control station on Earth. Most people never notice it. It’s a scale.

Not the bathroom kind. A precision instrument that can detect differences smaller than the weight of a human eyelash. And the company that dominates this world—the one whose instruments quietly sit underneath modern science, manufacturing, and trade—is Mettler-Toledo International.

The stakes are higher than they sound. When a pharmaceutical company formulates a cancer drug, the active ingredient has to be weighed in micrograms—millionths of a gram. When a packaged food company runs a line pushing out thousands of boxes an hour, every box needs to land on its target weight or risk regulatory penalties and expensive rework. When a gold refinery assays its product, the measurement has to be unimpeachable. In all of those moments—when accuracy isn’t a nice-to-have, but the whole job—the instrument doing the measuring is very often a Mettler-Toledo.

By 2025, the company’s revenue was approaching $4 billion, spread across more than 100 countries: roughly 42% from the Americas, 29% from Europe, and 29% from Asia and the rest of the world. Its adjusted operating margins have routinely cleared the high twenties and sometimes pushed into the low thirties—performance that would make most industrial companies stare, and even get a little respect from software-land. The stock trades on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker MTD, and since its 1997 IPO at fourteen dollars a share, it’s been an exceptional compounder. As of early 2026, it traded above $1,300.

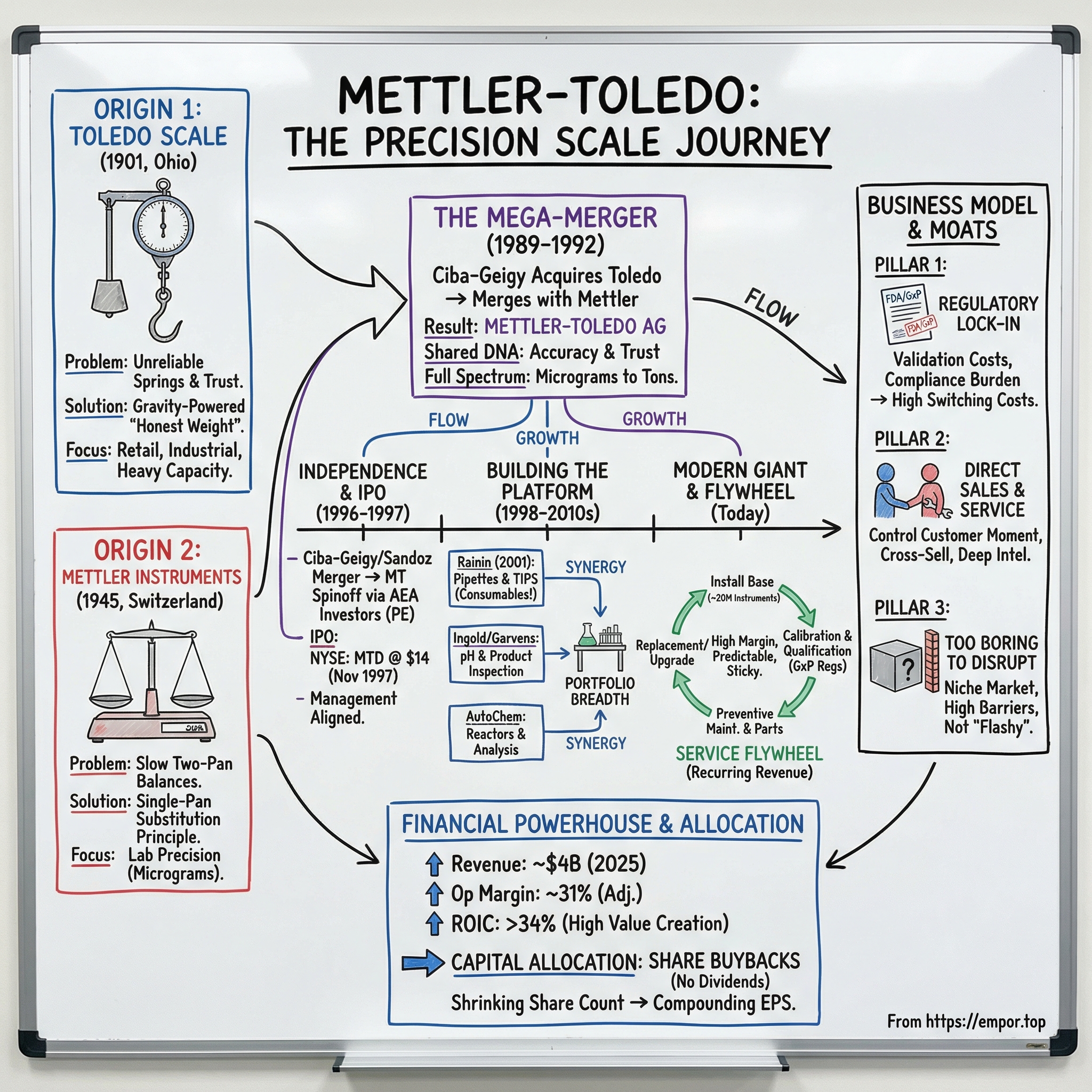

But Mettler-Toledo didn’t get here through a single genius founder or one miracle invention. This is a two-origin story: one Swiss, one American—born decades apart, on opposite sides of the Atlantic—eventually fused into one company through a merger that turned out to be an all-time great industrial combination. Along the way, we’ll see the unsexy power of measurement, the brilliance of regulatory lock-in, and what happens when you dominate mission-critical niches that most competitors ignore.

This is the story of how Toledo’s “Honest Weight” and Mettler’s “Single Pan” combined to build a precision empire.

II. Two Origin Stories: Toledo Scale & Mettler Instruments

Toledo Scale Company (1901–1989)

This story doesn’t start in a gleaming lab. It starts in a butcher shop in Toledo, Ohio, at the turn of the twentieth century.

Allen DeVilbiss Jr., born in 1873, was an inventor fixated on a very specific problem: scales that couldn’t be trusted. The typical scale of the era was a spring-loaded contraption—good enough until it wasn’t. Springs fatigue. Temperature changes them. Wear changes them. And if you were a customer, you always had to wonder whether the person behind the counter was helping the scale along with a discreet thumb.

DeVilbiss took a different approach. He built an automatic computing pendulum scale that used gravity—not springs—as the counterbalancing force. Gravity doesn’t drift. It doesn’t get “tired.” It’s the closest thing you can get to a guaranteed standard in the physical world.

According to the story, he showed the prototype to a local butcher, and the butcher immediately saw what mattered most. The real problem wasn’t necessarily fraud; it was suspicion. Customers worried they might be getting shorted, and honest shopkeepers hated being treated like they were crooked. A scale that displayed weight and price clearly—powered by an unchanging force—turned the whole interaction into something calmer: a transaction both sides could trust. “No springs — honest weight,” the pitch went. It was a technical claim that landed as a moral one.

Enter Henry Theobald, a former general manager at National Cash Register. NCR understood something fundamental: when you can make the transaction itself more trustworthy, you don’t just reduce losses—you sell confidence. Theobald saw DeVilbiss’s scale as the weighing equivalent of the cash register: a machine that made honesty legible. He bought DeVilbiss’s company, and on July 10, 1901, the Toledo Computing Scale and Cash Register Company was incorporated in northwestern Ohio.

Toledo didn’t just sell equipment. It sold an idea. The company launched a national “Honest Weight” campaign aimed at pushing back on deceptive weighing and pricing in food stores—those quiet little cheats where the price looked fair, but the quantity wasn’t. In an era before modern consumer protection had real teeth, Toledo positioned itself as the enforcer of fairness at the point of sale. If you were a store owner, putting a Toledo scale on the counter wasn’t just a purchase. It was a signal.

And the signal worked. A butcher shop with a Toledo scale was telling customers: we have nothing to hide. Demand spread from grocers and delicatessens to general stores across the country. Over time, Toledo expanded well beyond retail counters into the heavier end of American industry—truck scales, railroad scales, and factory systems—until it became the largest producer of industrial and food retail scale systems in the United States.

Then came the great twentieth-century pattern: consolidation.

In 1967, Toledo Scale merged with Reliance Electric Company and Dodge Manufacturing Corporation of Indiana, folding into a broader industrial group built around motors, drives, and automation. On paper, there was logic—shared customers, adjacent products, cross-selling dreams. In practice, it meant Toledo’s scale business became one more division inside someone else’s strategy.

In 1979, that distance from the core only got worse when Exxon Corporation bought Reliance Electric for $1.24 billion, making a precision weighing company a subsidiary of the world’s largest oil business. Exxon wanted diversification beyond petroleum, but an oil major wasn’t built to obsess over scales. Toledo kept operating and innovating through the 1980s—the engineering culture was strong enough to survive almost anything—but it was constrained by conglomerate priorities.

By the end of the decade, Reliance was looking to sell assets and reduce its roughly $1.2 billion debt burden. Toledo Scale was profitable, respected, and clearly non-core. So it went up for sale. And the buyer that mattered most in the weighing industry was about to show up.

Mettler Instruments (1945–1989)

Now shift three thousand miles east—and more than four decades forward—to the shores of Lake Zurich.

In 1945, as Europe rebuilt from World War II, Dr. Erhard Mettler started a precision mechanics company in Küsnacht, Switzerland. It’s the kind of place you picture when you hear “Swiss engineering”: quiet, orderly, meticulous. The setting fits, but the ambition was anything but small.

Mettler’s breakthrough sounds simple and is anything but: he invented the substitution principle in a single-pan balance. At the time, laboratories relied on equal-arm, two-pan balances—the classic seesaw setup. Put the sample on one side, add standardized weights to the other until it levels out. It worked, but it was slow, fussy, and operator-dependent. Worse, the sensitivity could vary depending on how much weight was sitting on the pans. In science, that’s not an inconvenience. It’s a problem.

Mettler’s design flipped the workflow. You placed the sample on a single pan, then removed built-in weights until the beam balanced. Because the total mass on the instrument stayed essentially constant across the measuring range, the sensitivity stayed essentially constant too. The last fraction of a gram was read from an illuminated optical scale.

The result was faster, more consistent, and—crucially—manufacturable at scale. Starting in 1946, Mettler began large-scale production, and laboratories around the world started swapping out their two-pan balances for Mettler’s single-pan instruments.

If the old two-pan balance was like tuning a guitar by ear—possible, but dependent on skill—Mettler’s approach was closer to using a reliable tuner: repeatable, standardized, and accessible.

For nearly thirty years, the company refined that mechanical foundation. Then, in 1973, Mettler made the leap that would pull weighing into the modern era: the PT1200, the first fully electronic precision balance. With a 1,200-gram capacity and 0.01-gram sensitivity, it replaced mechanical counterweights and optical readouts with electromagnetic force compensation. Instead of balancing mass with mass, it used electrical current to generate a precisely controlled magnetic force. The current required to hold the balance point mapped directly to the sample’s weight—and electronics could measure that with extraordinary precision.

This wasn’t just a better scale. It changed what a scale could be. Electronic weighing opened the door to digital output, automated calibration, and integration into lab systems—early steps toward the connected, data-rich instruments that now sit at the center of regulated science and manufacturing. In a very real sense, modern lab weighing traces back to this shift.

By 1980, Dr. Mettler was ready to retire. He’d spent thirty-five years building a company that changed how the world measured mass, and he wanted it to keep compounding after he stepped away. He sold to Ciba-Geigy AG, the Swiss pharmaceutical and chemical giant formed from the 1970 merger of Ciba AG and J.R. Geigy AG.

The fit was straightforward: Ciba-Geigy was one of Mettler’s biggest customers, relying on precision balances across pharmaceutical research and chemical operations. The acquisition gave Mettler deeper resources and long-term support, and it gave Ciba-Geigy tighter access to a critical tool in its own work. With the founder exiting and the company under a well-capitalized owner, Mettler was about to begin an unusually disciplined acquisition run—one that would expand it far beyond balances and set up the collision course with Toledo.

III. The Art of Scientific Acquisitions (1960s–1980s)

Even before Ciba-Geigy bought the company—and even more so afterward—Mettler started building itself the way the best industrial businesses do: patiently, deliberately, and with a very specific picture of the end state. These weren’t “growth for growth’s sake” deals. Each acquisition filled a missing capability, expanded Mettler’s reach inside the lab, or pushed it closer to the factory floor. The goal wasn’t a messy conglomerate. It was an integrated platform of precision measurement tools that customers would come to rely on every day.

The first move came in 1962, when Mettler acquired Dr. Ernst Rüst AG, a maker of high-precision mechanical scales founded just three years earlier. Mettler renamed it Mettler Optic AG and gained deeper capabilities in optical measurement—close cousin territory to high-end weighing. Small deal, big signal. The pattern was set: find tiny specialists with real technical edge—too small to go global on their own—then plug them into Mettler’s manufacturing, distribution, and customer base.

By 1970, Mettler was also stepping beyond pure weighing. It introduced automated titration systems—machines that measure the concentration of a dissolved substance by adding a reagent until a reaction hits its equivalence point. If that sounds academic, here’s why it mattered: in pharmaceutical and chemical quality control, you don’t just weigh a sample and call it a day. You have to prove what it is. You have to confirm that a batch contains the right amount of active ingredient, at the right concentration, every time. Titration is one of the core tools for that job, performed endlessly in labs around the world. With titration, Mettler extended its reach from “how much is here?” to “what is here?” That same year it also acquired Microwa AG, another balance manufacturer, reinforcing its grip on the core market.

Then came 1971 and a deal that changed the company’s trajectory: the acquisition of August Sauter KG. Based in Albstadt-Ebingen, Germany, Sauter brought roughly 500 employees and deep experience in industrial and retail scales—the rugged, heavy-duty systems that live on factory floors and at loading docks. Mettler’s heritage was gram-and-milligram precision; Sauter lived in kilograms and tons. This was Mettler declaring it didn’t want to be “just” a lab company. It wanted to be a measurement company, full stop.

In the mid-1980s, two more acquisitions sharpened Mettler’s position in ways that would matter for decades.

In 1986, Mettler acquired the Ingold Firmengruppe, a Swiss company founded in 1948 by Dr. Werner Ingold. Ingold was a leader in electrodes and sensors for measuring pH, and it had invented the single-rod measuring cell in the early 1950s—a design that simplified pH measurement from a more cumbersome two-electrode setup into a single integrated probe you could dip directly into a solution. pH might sound humble, but it’s foundational in pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and process industries. If you’re controlling a reaction, validating a formulation, or treating wastewater, pH is not optional. Ingold gave Mettler a powerful adjacent franchise—and reinforced a key insight: customers don’t buy instruments in isolation. If they trust you for weighing, they’re likely to trust you for the chemical measurements that sit right next to it in the workflow.

A year later, in 1987, Mettler acquired Garvens Automation GmbH near Hanover, Germany. Garvens specialized in dynamic checkweighers and dosage control systems—the machines that sit on production lines and verify, at speed, that every package contains exactly what it should. That’s a brutal engineering environment: products flying down a conveyor, measurements made in fractions of a second, accept-or-reject decisions executed instantly, day after day, in food and pharmaceutical plants where downtime is expensive and compliance is unforgiving. With Garvens, Mettler entered product inspection—an area that would grow into a major business. And the logic was beautifully simple: own the balance that helps develop the formulation in the lab, and own the checkweigher that verifies the finished product on the line.

By the late 1980s, Mettler had stitched together an enviable portfolio: laboratory balances, analytical chemistry instruments, pH sensors, and production-line inspection systems. What it didn’t yet have was the other half of global dominance—a commanding position in North America, and the industrial-scale brand power that came with it.

That missing piece had a name: Toledo Scale. And it was sitting inside Reliance Electric’s portfolio, available to anyone bold enough to see what it could become.

IV. The Mega-Merger: Creating Mettler-Toledo (1989–1992)

In 1989, Ciba-Geigy made the move that effectively created the company we know today. Through its subsidiary, Mettler United States Inc., it acquired the Toledo Scale Corporation from Reliance Electric.

For Reliance, the timing was clear. It was carrying heavy debt and wanted to refocus on its core electrical equipment business. Toledo was profitable and respected, but it was also non-core—exactly the kind of asset a debt-burdened industrial owner sells first. The transaction helped Reliance cut its debt to roughly $600 million, about half of what it had been in 1986.

For Mettler, the logic was almost too clean. Put the two businesses on a map and the fit jumps off the page. Mettler was strong in Europe and Asia; Toledo was strong in the Americas. Mettler owned laboratory precision; Toledo owned industrial and food retail scales. Mettler sold to scientists and analytical chemists; Toledo sold to plant managers, warehouse operators, and supermarket chains. There was remarkably little overlap—and a huge amount of “you have what I’m missing.”

The combined entity was renamed Mettler-Toledo AG, and overnight the company’s range expanded from one end of weighing to the other. Mettler had lived in the world of milligrams and micrograms; Toledo lived in kilograms and tons. Together, they could credibly cover almost any weighing job you could name—from instruments sensitive enough to register tiny differences in a lab sample to systems built to weigh fully loaded trucks. The company now operated in 18 countries, with a sales and service footprint that was hard for any competitor to match.

One person mattered a lot in making the combination work: Robert Spoerry. A Swiss executive who played a central role in orchestrating the Toledo acquisition, Spoerry became a defining figure in the newly merged company. Over a career that would span about 40 years, he helped shape nearly every major strategic choice during Mettler-Toledo’s formative decades. He later became the first CEO of the independent company after it separated from Ciba-Geigy, served as Board Chair from shortly after the 1997 IPO until retiring in May 2024, and helped set the operating and cultural standards that still define the business. Spoerry understood a subtle but crucial point: the real prize wasn’t simply a bigger catalog. It was a platform—one that could keep compounding through further acquisitions, geographic expansion, and relentless operational improvement.

That said, the cultural integration wasn’t automatic. Swiss precision engineering—methodical, consensus-driven, obsessed with technical excellence—met American industrial pragmatism—direct, relationship-heavy, focused on winning customers and growing share. The Swiss engineers thought in micrograms; the American sales teams thought in installed base and coverage. But both organizations had been built around the same non-negotiable: accuracy you could trust. In the end, that shared commitment to getting the measurement right gave them a common language, and a foundation to blend the best of both traditions.

In 1990, Mettler-Toledo kept moving. It acquired the rheology systems division of Contraves AG in Zurich, adding lab automation tools for measuring the flow properties of liquids and semi-solids. It also acquired the laboratory balance production of Ohaus Corporation, strengthening its position in laboratory and analytical measurement. And by 1992, the organizational work caught up with the strategy: the company was formally incorporated as Mettler Toledo, Inc., bringing the pieces under one legal roof.

What emerged was something genuinely unusual in precision instruments: a company diversified by geography, end market, and application, with an installed base running into the millions of instruments and a service network reaching virtually every place modern science and manufacturing happened. Under Ciba-Geigy’s ownership, Mettler-Toledo had resources to invest and room to think long-term.

But the calm wouldn’t last. A seismic shift inside Swiss pharma was coming—and it was about to change Mettler-Toledo’s trajectory again.

V. The Private Equity Interlude & IPO (1996–1997)

The mid-1990s brought one of the biggest corporate reshufflings in Europe, and Mettler-Toledo got swept up in it. In 1996, Ciba-Geigy announced its historic merger with Sandoz to form Novartis—an event that would redraw the Swiss pharmaceutical landscape. But to pull off a deal that big, Ciba-Geigy had to make a very clear case to regulators and investors: the combined company would be a focused pharma and life-sciences powerhouse.

That meant trimming anything that didn’t fit. And even though Mettler-Toledo was profitable, well-run, and strategically coherent, it was still a precision instruments business inside what was about to become one of the most single-minded pharmaceutical companies on earth. It didn’t belong in the story Novartis needed to tell. So it went on the block.

The exit came as a management buyout backed by AEA Investors, a New York-based private equity firm founded in 1968 by the Rockefeller, Mellon, and Harriman families, among others. AEA’s style mattered here. This wasn’t a business you “optimized” by stripping out the hard parts. Mettler-Toledo’s value lived in engineering culture, in long customer relationships, and in the deeply embedded know-how of making instruments people trust. AEA had a reputation for backing strong management and improving industrial companies without breaking what made them special.

The deal was valued at $402 million. By later standards, it looks almost understated for a company like this—partly a reflection of the conglomerate discount from its years under Ciba-Geigy, and partly the reality of buyouts where management sits on the inside of the business and holds real leverage in the negotiation. The financing followed the era’s private equity playbook: $307 million in bank borrowings, $135 million in senior subordinated notes, and a $190 million equity contribution primarily from AEA. Robert Spoerry and the management team kept meaningful equity as well, ensuring the people running the company were financially tied to what happened next.

For the first time, Mettler-Toledo was truly on its own. Not a division tucked inside someone else’s empire, but an independent company with its own board, its own capital structure, and its own incentives. The private equity chapter lasted barely a year, but it left a lasting imprint. AEA brought sharper financial discipline and a tighter focus on value creation. Management, now thinking like owners, started building the capital allocation muscle that would later become one of the company’s defining strengths.

Then came the public markets. On November 13, 1997, Mettler-Toledo went public on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker MTD. The IPO priced at $14 per share, with 6.67 million shares sold, raising about $93 million. It wasn’t a flashy offering, but it did the job: it brought in capital to help reduce debt and gave the company the visibility—and currency—it would need for the next phase. After the offering, management, employees, and company-sponsored benefit funds owned about 18% of the shares on a fully diluted basis, a meaningful stake that told outside investors this team intended to win alongside them. Spoerry became CEO and soon took on the chair role, positions from which he would shape Mettler-Toledo for years.

In hindsight, that day in November 1997 marked the start of one of the great compounding runs in industrial business. A $14 IPO share would go on to become worth orders of magnitude more within the next few decades. But at the time, none of that was obvious. What was obvious—at least to the people closest to the business—was that the machine was finally set up the right way: independent, aligned, disciplined, and ready to scale.

VI. Building the Modern Precision Giant (1998–2010s)

Now that Mettler-Toledo was independent and had access to public-market capital, it went on a long, quiet run to tighten its grip on the precision-instruments world. The playbook was consistent: smart acquisitions, steady geographic expansion, and—most importantly—turning its gigantic installed base into a durable services engine.

The signature post-IPO deal came in October 2001, when Mettler-Toledo bought Rainin Instrument for $292.2 million. The timing mattered. This was barely a month after September 11, when many companies were freezing budgets and pulling back. Mettler-Toledo leaned in anyway, a sign that management saw the long-term logic as stronger than the short-term fear.

Rainin was a top-tier maker of pipetting systems—the handheld tools scientists use to move precise volumes of liquid, from tiny microliters up to a few milliliters. If you’ve ever seen someone in a lab carefully dispense a droplet into a sample tube, there’s a good chance they were using a pipette. In biology, pipettes are like scalpels: they’re used constantly, they have to feel right in the hand, and they have to be right every single time. Rainin had a reputation as the premium choice, and the acquisition gave Mettler-Toledo a leading position in another daily, mission-critical step in the lab workflow.

But Rainin’s real magic wasn’t just the instruments. It was the tips.

A pipette tip is a disposable plastic cone that snaps onto the pipette and touches the liquid. Scientists burn through them by the dozens—sometimes by the hundreds—in a single day. Each tip has to meet strict requirements for accuracy, compatibility, and cleanliness. That makes tips a near-perfect consumable: recurring, essential, and high-margin. In other words, the “blades” to the pipette “razor.” With Rainin, Mettler-Toledo didn’t just sell more hardware; it picked up an ongoing stream of repeat purchases that fit beautifully alongside its growing service revenue.

The Rainin deal also showcased a pattern the company would repeat: find a niche where precision and reliability are non-negotiable, buy a leader, plug it into Mettler-Toledo’s global distribution and service footprint, then cross-sell it into the existing customer base. A lab that already trusted Mettler-Toledo for analytical balances was a natural buyer for Mettler-Toledo pipettes—and the reverse was true too. Each new product line didn’t just add revenue. It made the rest of the portfolio easier to sell because the company could take a bigger share of a customer’s total spend.

Across the 2000s and 2010s, Mettler-Toledo kept stacking smaller bolt-on acquisitions. It picked up distribution partners in key emerging markets, added complementary technology in areas like process analytics and laboratory automation, and filled in specialized niches such as thermal analysis and moisture measurement. None of these deals were splashy on their own, but together they widened the moat: broader offerings, tighter customer relationships, and fewer reasons to look elsewhere.

The biggest transformation of the era, though, wasn’t a single acquisition. It was the systematic build-out of the services business.

Under Robert Spoerry and then Olivier Filliol—CEO from January 2008 through March 2021—the company built a services organization that turned product shipments into long-lived customer annuities. The logic was simple: every balance, pipette, pH meter, and checkweigher that went out the door created years of follow-on work. Instruments have to be calibrated—often on a set cadence, especially in regulated environments. They need qualification against standards. They need preventive maintenance, firmware updates, repairs, and parts.

And in industries like pharmaceuticals, food, and chemicals, this isn’t optional housekeeping. Skipping calibration isn’t like skipping a software update. If measurements drift, you don’t just get slightly worse results—you risk shutdowns, citations, recalls, or worse. In regulated settings, compliance turns maintenance into a requirement, not a preference.

Over time, services grew from roughly 20% of net sales around the turn of the millennium to about 25% by 2025, and it grew faster than the product business—typically 6–8% organically per year. Even better, it came with higher margins and much more predictable demand. A customer might delay buying a new instrument during a downturn. They can’t delay the calibration schedule that keeps production qualified and auditors satisfied.

The other pillar was geographic expansion, and Mettler-Toledo took a more expensive—but more powerful—route than many competitors. Instead of leaning on third-party distributors, it built direct sales operations in major markets. That meant hiring and training salespeople and service engineers country by country, then managing them over decades. But it also meant control: tighter customer intimacy, better feedback loops, and the ability to capture the full lifetime value from first sale through years of service.

To make the direct model run at scale, the company leaned on its Spinnaker sales and marketing program, which systematized the go-to-market engine with disciplined sales processes, territory management, and customer segmentation. It wasn’t glamorous. It was repeatable. And it drove steady share gains over time—the kind that don’t show up as a headline, but do show up in the long-term chart.

By the end of the 2010s, the result was clear. Mettler-Toledo had grown from about $1.5 billion in revenue around the IPO era to nearly $3 billion, while adjusted operating margins climbed from the low-to-mid twenties into the high twenties. The compounding didn’t come from one breakthrough moment. It came from a thousand small wins: better pricing here, a little more share there, more service contracts renewed, more of the workflow captured.

It wasn’t a company built to make news. It was a company built to keep winning.

VII. The Business Model: Razors, Blades, and Lab Coats

To understand why Mettler-Toledo has compounded so well for so long, you have to zoom in on how it actually makes money. People often reach for the razor-and-blades analogy—sell the razor cheap, then profit on the blades. Mettler-Toledo is sneakier than that. It earns attractive margins on the instrument up front, and then it earns even better margins over the years on everything that keeps that instrument trusted, compliant, and in service. It’s razors and blades—without the loss-leading razor.

Laboratory instruments make up roughly 56% of net sales, and this is the company’s home turf. The lineup spans nearly the full range of daily lab measurement. At the top end are ultra-microbalances, sensitive enough to register changes as tiny as a fraction of a microgram—so small it’s easier to think of it as “basically nothing,” until you remember that modern pharma and analytical chemistry often live in that world. From there you move down the ladder: analytical balances, precision balances, standard lab balances—each one tuned to a different job, a different workflow, and a different tolerance for error.

Then come the products that labs touch constantly. Rainin pipettes and their disposable tips—the quiet consumable engine of biology and chemistry. Automated lab reactors that let scientists develop and optimize chemical reactions under tightly controlled conditions. Titrators for measuring concentrations, pH meters for monitoring acidity, thermal analysis instruments for understanding how materials behave as temperatures change, and a long tail of tools like moisture analyzers, UV/VIS spectrophotometers, and density meters. The throughline is simple: if a lab needs to measure it, there’s a decent chance Mettler-Toledo has built an instrument for it.

What makes the modern portfolio more powerful is that the instrument is no longer just hardware. Nearly everything now ships with software built in, and increasingly those instruments connect to Mettler-Toledo’s own data platforms. That matters because labs—especially regulated ones—are under mounting pressure to prove data integrity. Not just that a measurement was taken, but that it was taken the right way, on the right instrument, by the right operator, at the right time, with a record that can stand up to scrutiny. The software layer helps automate record-keeping, compliance documentation, and workflow controls. And once measurement and compliance live inside a platform, the relationship becomes stickier—and more recurring—through licenses, updates, and ongoing support.

The breadth of the lab portfolio creates a flywheel: the more of the workflow Mettler-Toledo owns, the easier it is to sell the next instrument, and the harder it is for a customer to standardize on someone else. You can see this in a single example: a pharmaceutical drug moving from idea to production. In discovery, scientists weigh ingredients and dispense liquids—balances and pipettes. In process development, they optimize synthesis—reactors and thermal analysis. In quality control, they confirm concentrations and properties—titration, pH, moisture. In manufacturing, they scale and validate—industrial dispensing and production-line verification. From bench to market, the company can show up at almost every step, and often does.

Industrial instruments are roughly 39% of net sales, and they bring Mettler-Toledo from the clean bench to the messy reality of the factory floor. This segment runs from everyday bench and floor scales all the way up to platform and vehicle scales used in logistics and distribution. It also includes product inspection—metal detection, X-ray inspection, checkweighing, and vision systems—an area that traces back to Garvens and has become one of the company’s most important growth engines. The drivers here are structural: tighter food safety standards, more automation, and the simple fact that when production speeds up, inspection has to keep up. If a food producer needs to ensure there’s no metal fragment in a batch, or a line needs to reject underweight packages at full speed, these are exactly the kinds of systems Mettler-Toledo is built to supply.

Food retail sits at about 5% of net sales, and it’s the smallest—and most debated—piece of the portfolio. These are the scales and labeling systems in grocery stores: deli counters, bakeries, and produce departments. The segment has been mostly flat for years, and it has seen sharp declines at times—down 14% in Q4 2025, for example—so it’s natural that investors ask whether it still belongs. But it also throws off cash, shares manufacturing and engineering capabilities with the rest of the business, and keeps the brand visible to end consumers who might never see it otherwise. For now, it remains a legacy business that the company has chosen to keep rather than divest.

The real engine, though, is what happens after the initial sale. Mettler-Toledo’s installed base is enormous—more than 20 million instruments globally—with a combined replacement value estimated around $16 billion. Each instrument is a long-lived asset that has to stay accurate, documented, and defensible. That creates a built-in stream of follow-on work: calibration, performance verification, compliance paperwork, repairs, parts, software updates, and, eventually, replacement. Service contracts typically run one to three years and renew at high rates. And in regulated environments, this isn’t optional. It’s the cost of staying in business.

Put it together and you get a rare industrial profile: mission-critical products embedded deep inside regulated workflows, paired with recurring, high-margin service and consumables revenue that’s hard to dislodge. Switching costs are high, pricing power is real, and demand is unusually visible. It’s not a business built for dramatic “disruption” headlines. It’s built for quiet entrenchment—getting so deeply trusted inside the customer’s process that replacing you becomes the risky move.

VIII. Market Position & Competitive Dynamics

Mettler-Toledo sits in a rare sweet spot: it’s the clear global leader in a market that’s both fragmented and harder to break into than it looks. In laboratory balances—its flagship category—the company holds an estimated 40–45% share worldwide, with the rest split among a few serious rivals and a long tail of regional players. And in several of the narrower niches it plays in—ultra-microbalances, automated titration, process analytics, dynamic checkweighers—its share is often even higher.

The competitive fight changes depending on where you look.

In laboratory instruments, the closest rival is Sartorius AG, the German company from Göttingen that has pushed hard on modern balance design: detachable displays, touch-free controls for sterile settings, automatic leveling, and ultra-microbalances aimed at the most demanding pharmaceutical work. Sartorius is especially strong in bioprocess solutions—systems used to manufacture biologic drugs like monoclonal antibodies—and it uses that position to cross-sell balances into biotech customers. Japan’s Shimadzu competes across a broad range of analytical instruments, though its balance business is smaller than either Mettler-Toledo’s or Sartorius’s. And then you have the U.S. analytical-instrument giants—Thermo Fisher Scientific, Agilent Technologies, and Waters Corporation—who compete heavily in adjacent categories like chromatography, mass spectrometry, and molecular spectroscopy, but don’t bring the same focused, end-to-end precision weighing portfolio.

In industrial weighing and product inspection, the field looks different: Minebea Intec in Germany; Ishida in Japan, which is especially dominant in multihead combination weighers for snack-food packaging; Wipotec in Germany, known for pharmaceutical track-and-trace; and regional specialists like Rice Lake Weighing Systems and Avery Weigh-Tronix. Product inspection is a growing market and it’s attracting more attention, but Mettler-Toledo’s blend of detection know-how, installed base, and global service coverage is not something a new entrant can replicate quickly.

What makes Mettler-Toledo’s position feel unusually durable is that it isn’t built on just one advantage. It’s built on three moats that reinforce each other.

The first—and most powerful—is regulatory lock-in. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, any instrument used in a GxP environment—Good Manufacturing Practice, Good Laboratory Practice, Good Clinical Practice—has to be qualified at installation, validated for its intended use, calibrated under documented procedures, and maintained with full traceability. Swapping a Mettler-Toledo balance for a competitor’s isn’t just a purchase order. It means running Installation Qualification, Operational Qualification, and Performance Qualification. It means revalidating methods, retraining operators, updating standard operating procedures, and documenting it all for inspection. For a large pharma company with many validated methods across multiple sites, the switching cost can climb into the hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars—and that’s before you factor in the risk of disrupting a process that’s producing revenue-generating drugs. In most cases, the rational choice is to stay put.

The second moat is the direct sales and service model. Many competitors lean heavily on distributors, which is cheaper in the short run but weaker strategically. Mettler-Toledo, by contrast, runs a direct organization with thousands of sales reps and service engineers in its major markets. That buys it tighter customer relationships, better cross-selling across a broad catalog, and—most importantly—control over the service moment. When a Mettler-Toledo technician walks into a lab to calibrate a balance, they don’t just see the one instrument on the work order. They see the whole room, including competitors’ instruments. That real-world visibility turns service into both a customer-retention engine and a steady source of competitive intelligence that can fuel targeted share gains over time.

The third moat is the “too boring to disrupt” defense. Big tech and venture-backed startups tend to chase giant, visible markets with consumer pull or platform dynamics. Precision balances and industrial checkweighers don’t offer either. The total market for precision weighing is valuable, but it’s still in the single-digit billions—generally too small to pull in the biggest would-be disruptors. And the technical and regulatory barriers are real. Building a microbalance accurate to a tenth of a microgram, then earning the certifications needed to sell into regulated pharma environments, takes decades of accumulated engineering skill, manufacturing expertise, and regulatory credibility. That’s not something you can brute-force with capital alone.

China deserves special mention because it’s where a lot of the opportunity—and a lot of the perceived risk—concentrates. China accounts for roughly 16% of Mettler-Toledo’s external sales, but about 29% of segment profit, reflecting both strong market position and substantial manufacturing operations in the country. That profit concentration has been a recurring investor concern as U.S.–China tensions have risen and tariffs have complicated supply chains. The company’s move to reduce China imports to around $30 million for 2026 by shifting sourcing to Mexico and Switzerland is one way it’s working to reduce exposure—but the profit concentration in China remains a key part of the story.

IX. Financial Performance & Capital Allocation

The numbers tell a story of relentless, disciplined compounding—the kind that doesn’t look dramatic quarter to quarter, but becomes impossible to ignore over decades.

In 2024, Mettler-Toledo reported revenue of $3.872 billion, up 2% from the year before. Adjusted operating profit was about $1.2 billion, translating to an adjusted operating margin around 31%. Net earnings were $863 million, nearly 10% higher year over year, and adjusted EPS landed around $41, up 8% from 2023.

In 2025, revenue reached roughly $4.03 billion, about 3% growth in local currency. In Q4 2025—reported on February 5, 2026—the company posted revenue of $1.13 billion, up 8% as reported and 5% in local currency, with growth across all three major regions: the Americas up 7%, Europe up 4%, and Asia up 4%.

What’s striking isn’t just the size. It’s the shape. Over the long arc, Mettler-Toledo expanded adjusted operating margins from the mid-twenties in the early 2000s to above 31% in 2024, powered by pricing discipline, the Spinnaker go-to-market program, lean manufacturing, and a growing mix of higher-margin services. In 2025, margins stepped down to 29.6% as the company absorbed about $50 million in incremental tariff costs—roughly a 130-basis-point hit to operating margin and a meaningful drag on EPS growth—yet it still delivered about 4% adjusted EPS growth to approximately $42.73. Gross margin has reached about 60%, a level that looks more like software than heavy industry, and it’s a direct reflection of what happens when you sell mission-critical, regulated instruments with real switching costs.

Then there’s cash. Mettler-Toledo has consistently produced roughly $850–900 million of free cash flow per year in recent years, converting a large share of earnings into actual dollars. That reliability comes from disciplined working capital management and the fact that this business doesn’t need massive capital expenditures to grow. And that free cash flow is the fuel for one of the company’s defining choices: capital allocation.

Mettler-Toledo has never paid a dividend. Not once as a public company. Instead, it has returned essentially all of its free cash flow through share repurchases—often $700 million to $1 billion a year. Over time, that has steadily pushed the share count down, from well over 25 million around the IPO to about 20.4 million shares outstanding in early 2026. The company authorized an additional $2.75 billion repurchase program in late 2025 and planned to spend $825–875 million on buybacks in 2026, supported by expected free cash flow of about $900 million.

This is where the balance sheet can look strange if you’re not used to this kind of playbook. Mettler-Toledo has negative shareholders’ equity, roughly in the range of -$127 million to -$182 million. That isn’t a sign the business is broken; it’s what happens when a company buys back more stock than it has retained in earnings over its public life. It also carries about $2.2 billion of total debt and only around $67 million of cash. To an untrained eye, that can read like danger. In reality, it reflects a management team that believes the free cash flow stream is durable enough to run a leveraged, buyback-heavy model. The debt is spread across investment-grade senior notes with staggered maturities, and annual interest expense of roughly $75 million is small relative to close to $900 million in free cash flow.

If you want a single metric that captures how well this machine works, it’s return on invested capital. Mettler-Toledo’s ROIC has consistently been above 34%, against an estimated weighted average cost of capital around 7%. That spread—economic value creation year after year—is what you get when pricing power, regulatory lock-in, and operational discipline reinforce each other.

Importantly, the company hasn’t starved the future to fund the buybacks. R&D has run around $189 million per year, about 4.9% of revenue. In precision instrumentation, innovation tends to be cumulative rather than flashy: making measurements more accurate, instruments more automated, workflows more connected. The company’s current focus areas—automation, digitalization, and AI-enabled instruments—are aimed at the next phase of lab and production modernization.

For anyone trying to track whether this is still a compounding machine, two operating signals matter most: local-currency organic revenue growth and adjusted operating margin. The first tells you what demand looks like after stripping out FX and acquisition noise. The second tells you whether pricing power and execution are holding. Together, they answer the only question that really matters with a long-duration compounder: is the machine still working the way it always has?

X. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

Mettler-Toledo is a reminder that the best businesses often look boring—right up until you realize how essential they are. Underneath the scales and sensors is a playbook that travels well, even if you’ve never set foot in a lab.

The power of boring, mission-critical products. Nobody takes a victory lap over buying an analytical balance. No one brags about a new checkweigher. And no venture capitalist is leading a seed round for a “disruptive weighing platform.” But these instruments sit at the choke points of modern industry. You can’t make pharmaceuticals without weighing ingredients. You can’t run high-throughput food lines without inspection and weight verification. You can’t do routine analytical chemistry without tools like titrators. When a product is mission-critical, accuracy is non-negotiable, and downtime is unacceptable, the vendor that earns trust tends to keep it. The broader lesson isn’t “buy boring.” It’s that boring and defensible often show up together—especially when the product is embedded in a workflow that has to be right every time.

Building through serial acquisition in fragmented markets. Mettler-Toledo didn’t get its portfolio from one heroic, transformative deal. It assembled it over decades with disciplined, targeted acquisitions—from Dr. Ernst Rüst AG in 1962, to Rainin in 2001, to countless smaller bolt-ons—each one filling a gap, adding a capability, or expanding reach. That strategy demands patience and restraint. You have to know the landscape well enough to spot the specialist worth buying, and you have to integrate without breaking the very expertise you paid for. The quiet skill here is consistency: doing many deals without turning into a messy conglomerate.

Transitioning from product to service revenue. The shift of services from roughly 20% to 25% of net sales doesn’t sound dramatic—until you remember what service revenue does to a business. It’s steadier, typically higher-margin, and less cyclical than selling new equipment. And in many of Mettler-Toledo’s end markets, it’s tied to compliance. Calibration, qualification, documentation, preventive maintenance—this is not “nice to have.” It’s the cost of operating in regulated environments. The lesson is simple: if you sell durable equipment into a regulated workflow, the first sale is just the start. The compounding happens in the lifetime relationship.

Geographic diversification as risk management. With revenue spread roughly 42% Americas, 29% Europe, and 29% Asia, Mettler-Toledo isn’t “international” in name only. That footprint has cushioned regional slowdowns and, more recently, helped the company respond to tariffs and supply-chain shocks. In 2025, it moved quickly to reposition sourcing—cutting China imports to about $30 million and shifting production to Mexico and Switzerland. The point isn’t that globalization eliminates risk. It’s that real global operations can give you options when geopolitics changes the rules mid-game.

The regulatory moat strategy. If you want the deepest competitive advantage in this story, it’s not a single patent or a clever feature. It’s switching costs enforced by regulation. In pharma, food safety, and chemical environments, changing instrument vendors isn’t just buying new hardware. It’s requalification, revalidation, retraining, and the documentation burden that comes with it. From the outside, the moat is invisible. From the inside, it can be nearly impassable. The broader lesson is almost paradoxical: the same rules that constrain customers can end up protecting the incumbent who helps them comply.

PE ownership as a catalyst, not a constraint. The 1996 management buyout backed by AEA Investors is a clean example of private equity working when it respects what actually creates value. AEA brought financial discipline and a tighter capital structure, but it didn’t try to “optimize” away the things that mattered: engineering culture, customer trust, and continuity in management. The lesson is that private equity can be a real catalyst—when it supplies a framework for operational excellence instead of forcing a generic financial engineering template onto a business that requires domain expertise and long-term thinking.

XI. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

Bull Case

The bull case for Mettler-Toledo is that this is one of those rare industrial businesses where the same forces that make customers cautious also make the incumbent incredibly hard to dislodge.

Start with the core: Mettler-Toledo is effectively irreplaceable in regulated industries. In pharma, food, and chemicals, measurement isn’t just part of the workflow. It’s part of the audit trail. Regulations around data integrity and validated processes mean the instrument is not “a box you bought,” it’s a documented system you rely on. The stricter the rules get—whether it’s FDA expectations, Europe’s Annex 11, or evolving GMP standards in China—the more expensive and risky it becomes to swap vendors. That’s the quiet genius of the model: compliance doesn’t just create demand, it hardens switching costs.

Then there’s the recurring revenue engine. Services keep growing faster than the overall company, and the installed base—more than 20 million instruments—creates a runway that’s measured in decades, not quarters. Service work tends to be higher-margin and less cyclical than new equipment sales, and it compounds almost automatically: every instrument sold expands the installed base; the installed base drives calibrations, qualifications, maintenance, and repairs; that drives cash; and cash enables buybacks, which amplify EPS growth. It’s a flywheel that doesn’t require a new breakthrough product every year to keep spinning.

Emerging markets add another long tail. As India, Southeast Asia, and parts of Latin America continue building out pharmaceutical manufacturing, food processing, and quality systems, they need the same precision infrastructure the U.S. and Europe already have. China, despite near-term bumps, is still a major modernization story in labs and industry—one that likely has years left.

If you zoom out and use Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, the advantages line up neatly. Switching costs are obvious and unusually strong because they’re enforced by regulation and validation burdens. Scale economies show up in manufacturing, R&D, and, most importantly, a global service network that’s hard to replicate. Brand matters in a world where “good enough” isn’t good enough—the Mettler-Toledo name functions as a trust shortcut. And process power is real: decades of accumulated expertise in precision engineering, compliance documentation, and service execution that a newcomer can’t buy off the shelf.

Porter’s Five Forces tells the same story in a different language. Barriers to entry are high because you don’t just need clever engineering—you need certifications, credibility, distribution, and service coverage, plus years of trust built with quality and compliance teams. Supplier power is moderate. Substitute risk is low because, in regulated environments, there’s no workaround for the physical act of measurement; software can assist, but it can’t replace weighing a sample or measuring pH. Buyer power exists—big pharma procurement teams are real—but it’s tempered by the fact that switching costs often dwarf any savings. Rivalry is real but usually rational; this is a market where the competition tends to fight on reliability and innovation, not on suicidal price wars.

Bear Case

The bear case starts where most bear cases start for great businesses: the price you pay.

Mettler-Toledo has traded around 35 times trailing earnings and about 30 times forward estimates, with EV/EBITDA around 20x—multiples that assume years of continued execution. When expectations are that high, the margin for error gets thin. A softer quarter, an unexpected margin hit, or a geopolitical shock can compress the multiple fast. The stock’s nearly 40% peak-to-trough drawdown during the 2022–2023 period is the reminder: even elite compounders can be brutal when growth slows and the market rerates the story.

There’s also more cyclicality here than the narrative sometimes admits. Lab equipment purchases can be delayed, and the industrial segment is tied to manufacturing capex cycles. The Q1 2025 results—revenue down 5% and adjusted EPS down 8%—showed that this company can absolutely feel macro headwinds. At a premium valuation, you don’t get much forgiveness for a down cycle.

China is a specific concentration risk. It’s roughly 16% of external sales but about 29% of segment profit, which means the earnings stream is more exposed to Chinese conditions than the headline revenue mix suggests. If China’s slowdown persists—property stress, weak confidence, and continued U.S.–China tensions—Mettler-Toledo could face a longer, tougher digestion period there than investors want to underwrite.

Technology disruption is unlikely near term, but it isn’t impossible to imagine. If new measurement approaches—advanced photonics, quantum sensing, or AI-enabled analytical methods—start displacing traditional weighing or titration in some applications, parts of the portfolio could face pressure. The company’s R&D spend, around 4.9% of revenue, is meaningful but not enormous, and that’s the kind of detail bears latch onto when they think about a world where the measurement stack changes. That said, regulation cuts both ways: even when new tech appears, adoption in pharma and food safety tends to be slow, giving incumbents time to respond.

Finally, customer consolidation is a slow-burn risk. As pharmaceutical and chemical giants merge and procurement becomes more centralized and disciplined, those customers can push harder on pricing and service terms. Mettler-Toledo’s switching costs help, but large buyers with professional sourcing teams will still try to extract concessions wherever they can.

XII. Epilogue & Reflections

Stand in a modern pharmaceutical clean room and just look around. The analytical balances on the benches. The pH probes mounted to reactors. The pipettes lined up at the hood. The checkweighers on the packaging line just outside the door. There’s a good chance a lot of them carry the same mark: the blue “MT” logo.

That’s the thing about Mettler-Toledo. It isn’t consumer-famous. It’s workflow-famous. It’s the hidden infrastructure of modern science and commerce—the precision layer underneath the medicines we take, the food we eat, and the chemicals that make modern life possible. Invisible to the end customer, indispensable to the people who can’t afford to be wrong.

Dr. Erhard Mettler, working on his single-pan balance in a lakeside Swiss workshop in 1945, couldn’t have known his substitution principle would become a cornerstone of a global precision-instruments leader. Allen DeVilbiss Jr., showing off a gravity-powered scale to a Toledo butcher in 1901, couldn’t have foreseen that “Honest Weight”—the idea that a transaction should be transparent and accurate—would echo through laboratories and factories across the world more than a century later. But the thread connecting those origins to today never really breaks: measurement matters, accuracy is worth paying for, and trust is built one verified result at a time.

One of the more revealing takeaways from studying Mettler-Toledo is how steady the core thesis has stayed. The company today is still recognizably the platform Robert Spoerry shaped: grow through targeted acquisitions, deepen the installed base with services, expand through direct sales, and return capital through repurchases. Under current CEO Patrick Kaltenbach—who joined from Becton Dickinson in early 2021, with prior experience at Agilent and Hewlett-Packard—the company continued to run the same playbook with the same patience.

What’s most remarkable isn’t any single product launch or deal. It’s the consistency. Over nearly three decades as a public company, Mettler-Toledo largely avoided the classic traps: chasing unrelated diversification, doing “transformational” mergers that dilute focus, or trading long-term strength for short-term applause. In an era where many CEOs feel pressure to reintroduce their company every quarter, Mettler-Toledo kept doing the same thing—better: build instruments that measure with extraordinary precision, then keep those instruments accurate, compliant, and running for years afterward.

For founders and investors drawn to “boring” industries, that’s the lesson. The strongest compounding machines are often the ones that never become dinner-party conversation. They don’t win on hype. They win on necessity. They build moats through regulation, service, and trust—not network effects. The world will always need to measure things. And as long as it does, Mettler-Toledo will be there, quietly turning uncertainty into a number you can stake your business on.

XIII. Recent News

The latest chapter in Mettler-Toledo’s story has been shaped by tariffs, fast supply-chain reshuffling, and a strong finish to 2025 that showed just how quickly the company can adapt when the rules change.

On February 5, 2026, Mettler-Toledo reported Q4 2025 results that came in ahead of expectations. Revenue was $1.13 billion, up 8% as reported and 5% in local currency. Adjusted EPS was $13.36, up 8% year over year and ahead of the $12.81 consensus estimate. Importantly, the growth wasn’t narrow. The Americas rose 7% (with about 3% coming from acquisitions), Europe grew 4%, and Asia grew 4% in local currency.

The mix also told a story. Laboratory instruments led with 18% growth, product inspection grew 12%, and core industrial instruments grew 5%. Food retail, the chronic laggard, fell 14%, which fit the long-running secular pressure on that segment.

For the full year 2025, revenue reached about $4.03 billion and adjusted EPS was about $42.73, up 4% from 2024—even after roughly $50 million of tariff costs hit results, compressing operating margin by about 130 basis points and cutting an estimated 5% off EPS growth. The year started sluggishly, with revenue down 5% in Q1 as trade disruptions weighed on demand, but performance improved quarter by quarter and finished with the Q4 snapback.

The most impressive operational story was what management did about the tariffs. With about $115 million of estimated annual incremental tariff costs staring them down, the company moved to sharply reduce China import exposure to about $30 million for 2026. Mexico became the largest import source at over $100 million, with Switzerland moving into the number-two slot thanks to favorable trade agreement terms that reduced tariff rates. This wasn’t a slow, multi-year unwind. It was a reconfiguration measured in months—something only possible when you have a global manufacturing footprint and enough scale to shift production across sites without losing your footing.

Looking ahead, Mettler-Toledo issued 2026 guidance for about 4% local-currency sales growth and adjusted EPS of $46.05 to $46.70, implying 8–9% growth and a step up from 2025’s pace. The midpoint, $46.38, came in modestly above consensus. At the same time, Q1 guidance of $8.60 to $8.75 in EPS was slightly below expectations, reflecting management’s view that customers could start the year cautiously given ongoing global trade uncertainty.

CEO Patrick Kaltenbach also pointed to a potential tailwind the company hadn’t baked into guidance: reshoring. Roughly half of Mettler-Toledo’s business supports production processes, and another 20% supports quality assurance and quality control—exactly the areas that tend to benefit as companies invest in onshoring and supply-chain resilience. If reshoring accelerates, it could become an upside lever that isn’t fully reflected in estimates.

On the Street, BofA Securities raised its price target to $1,640 from $1,600, kept a Buy rating, and described the 2026 outlook as conservative with meaningful upside potential. The broader analyst consensus sat around $1,507, with a mix of ratings skewing toward Hold and Buy.

And the buyback machine kept humming. In late 2025, the board approved another $2.75 billion share repurchase authorization, and the company planned $825–875 million of buybacks in 2026. With expected free cash flow around $900 million, Mettler-Toledo signaled it intended to keep doing what it has done for decades: let steady growth, margin discipline, and a shrinking share count compound into mid-teens EPS growth as tariff pressure eases.

XIV. Links & Resources

Company Filings & Investor Relations - Mettler-Toledo International Inc. Annual Report (Form 10-K), filed with the SEC - Mettler-Toledo International Inc. Quarterly Reports (Form 10-Q), filed with the SEC - Mettler-Toledo Investor Relations: investor.mt.com

Historical Sources - Honest Weight: The Story of Toledo Scale — VII Capital Management (December 2022) - A Century of Toledo Scale — Toledo’s Attic, toledosattic.org - History of Mettler-Toledo International Inc. — FundingUniverse, fundinguniverse.com - Mettler-Toledo International Inc. company profile — Encyclopedia.com

Industry Analysis & Long-Form Articles - Mettler Toledo: A Quiet Giant in Precision Instruments — Heavy Moat Investments (Substack) - Inside Mettler-Toledo: How Recurring Services Anchor Its Global Compliance Moat — BizModel Mastery (Substack) - Mettler-Toledo FY2024 Results — Andvari (Substack)

Earnings & Financial Data - Mettler-Toledo Q4 2025 Results — Business Wire (February 5, 2026) - Mettler-Toledo Q2 2025 Results — investor.mt.com - MacroTrends — MTD revenue, operating income, and free cash flow history - Stock Analysis — stockanalysis.com/stocks/mtd

Competitive & Market Research - Mettler-Toledo competitor analysis — PitchGrade - Sartorius AG Investor Relations — sartorius.com - Thermo Fisher Scientific Investor Relations — thermofisher.com

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music